Behandeling bij mandibulaire botinvasie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de behandeling van voorkeur bij patiënten met mondholtecarcinomen met mandibulaire botinvasie?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg een marginale mandibularesectie bij patiënten met een beperkte aantasting van het corticale bot wanneer er voldoende chirurgische botmarge te behalen is.

Overweeg een segmentale resectie bij patiënten met een uitgebreidere aantasting van het bot waarbij er oncologisch onvoldoende chirurgische botmarge te behalen is of onvoldoende mandibulair bot achterblijft voor voldoende stevigheid van de mandibula.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

In totaal zijn er vijf studies die de (on)gunstige effecten van een marginale resectie vergelijken met een segmentale resectie bij patiënten met botinvasie door een mondholtecarcinoom. Dit betrof één systematisch literatuuronderzoek met 15 observationele studies gepubliceerd tot mei 2016 (Gou, 2018) en vier nieuwere observationele studies die na de zoekdatum van het systematische literatuuroverzicht van Gou (2018) werden gepubliceerd. De uitkomsten in van de verschillende studies worden wel weergegeven in één figuur, echter wordt er geen gepoolde effect schatter weergegeven, omdat (1) er niet gecorrigeerd is voor prognostische factoren in de individuele studies en (2) de procedures van het uitvoeren van de chirurgische interventies mogelijk verschillen tussen de studies (aangezien deze informatie niet duidelijk wordt beschreven in de studies).

De conclusies van de samenvatting van de literatuur met betrekking tot de cruciale uitkomstmaten (dat wil zeggen ‘tumor-free resection’, ‘recurrence rate’, ‘disease-specific survival’, ‘overall survival rate‘) geven aan dat het bewijs erg onzeker is over de (on)gunstige effecten van een marginale resectie vergelijken met een segmentale resectie bij patiënten met mandibulaire botinvasie door een mondholtecarcinoom. Dit wordt mede veroorzaakt doordat het betrouwbaarheidsinterval de grens voor klinische relevatie overlapt, de resultaten tussen de studies inconsistent zijn of door het risico op bias in de individuele studies. Geen enkele studie heeft een randomisatieprocedure gehad. Hierdoor bestaat er een risico dat de geïncludeerde patiënten een indicatie hebben gehad voor één van beide behandelingen. De resultaten op de uitkomsten in de groepen zouden, naast de behandeling, (ook) af kunnen hangen van deze indicatie en/of van andere mogelijke (on)gemeten confounders. Zo kan er bijvoorbeeld voor een marginale resectie zijn gekozen bij patiënten met een beperkte botinvasie van de primaire tumor, maar hangt de beperkte botinvasie wellicht ook op zichzelf samen met een betere locoregionale controle of ziekte-specifieke overleving.De vergelijkingen tussen de groepen op dergelijke uitkomstmaten zal daarom met grote voorzichtigheid moeten worden geïnterpreteerd. De bewijskracht voor de literatuur is om deze redenen zeer laag. Ditzelfde geldt ook voor de belangrijk uitkomstmaten (dat wil zeggen ‘function’, ‘duration surgery’, ‘complications’). De algehele bewijskracht voor de samenvatting van de literatuur is zeer laag.

Er werd geen enkele RCT gevonden. De kans bestaat dat de resultaten in de opgenomen studies in de literatuuranalyse vertekend zijn. Patiënten in de studies konden door de eventuele aanwezigheid van een indicatie wellicht een specifieke interventie ontvangen (d.w.z. een segmentale of marginale resectie), welke door een randomisatie zou worden weggenomen in en RCT. Daarnaast lijkt er geen correctie te zijn toegepast voor eventuele verschillen tussen groepen op prognostische factoren. Een marginale resectie lijkt minder belastend te zijn voor de patiënt. Daarnaast lijkt een marginale resectie met grote onzekerheid tot betere uitkomsten te leiden in de literatuur ten opzichte van een segmentale resectie, maar dit is niet erg plausibel. Wellicht leidt bij een (sterk) geselecteerde groep patiënten een marginale resectie niet tot een slechtere oncologische uitkomst, maar kan de functionele uitkomst wel beter zijn. Dit zal nog onderzocht moeten worden.

Bij een mondholtetumor met aanwezigheid van (beperkte) aantasting van het bot kan gekozen worden voor een marginale op segmentale mandibularesectie. Het is aannemelijk dat een beperktere chirurgische ingreep met een marginale mandibularesectie zorgt voor minder morbiditeit, een kleiner chirurgisch defect en een kortere operatieduur. Er is echter geen wetenschappelijk bewijs dat deze ingreep resulteert in een beter functioneel resultaat wanneer er vergeleken wordt met een segmentale mandibularesectie.

Er is tevens geen wetenschappelijk bewijs gevonden hoe veel botresectiemarge aangehouden moet worden bij verwijdering van een mondholte tumor met (beperkte) aantasting van het bot. Het effect van een marginale of segmentale mandibularesectie of de disease-specific of overall survival is eveneens onduidelijk.

Wanneer sprake is van een beperkte aantasting van het corticale bot en voldoende chirurgische marge behaald kan worden en voldoende bot achterblijft om voldoende stevigheid van de onderkaak te waarborgen, is een marginale mandibularesectie te overwegen. Een segmentale mandibularesectie lijkt geïndiceerd bij tumoren met uitgebreide corticale of medullaire aantasting van het bot of bij oppervlakkige botinvasie waarbij door anatomische redenen anders geen chirurgische marge behaald kan worden met behoud van voldoende stevigheid van de mandibula. Voorbeelden zijn een geresorbeerde edentate mandibula of wanneer er onvoldoende hoogte van de mandibula overblijft als er een marginale resectie zou worden uitgevoerd.

Het lijkt de werkgroep verstandig beide behandelopties indien technisch mogelijk (marginale en segmentale resectie) en de gevolgen hiervan op de reconstructieve uitgangssituatie met patiënten te bespreken en de waarden en voorkeuren van de patiënt hierbij in acht te nemen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Een goed oncologisch resultaat met een goede functionele uitkomst zijn voor de patiënt belangrijke uitkomstmaten. Een marginale mandibularesectie resulteert in het algemeen in een kortere operatieduur, waarbij er een beperkter chirurgisch defect ontstaat en de kans op complicaties mogelijk kleiner is. Bij een segmentale mandibularesectie is een grotere reconstructie ingreep noodzakelijk en daarmee nemen de operatieduur en de belasting voor de patiënt toe.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Het chirurgische defect dat ontstaat bij een segmentale mandibularesectie zal veelal gereconstrueerd moeten worden met (titanium) reconstructieplaat met of zonder een bot of weke delen transplantaat. Dit is een operatie met een langere duur, langere opname in het ziekenhuis, meer kans op complicaties en derhalve meer kosten.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Alle hoofdhals centra waar benige reconstructies worden uitgevoerd kunnen zowel een segmentale als een marginale mandibularesectie aanbieden aan de patiënt. Hierbij zou de ervaring van het behandelteam geen rol hoeven te spelen. Bij kwetsbare patiënten, waar de operatieduur en complexiteit van de behandeling van groot belang zijn, zou overwogen kunnen worden om voor de minder invasieve behandeling van de marginale mandibularesectie te kiezen.

Aanbeveling-1

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Er is geen bewijs dat een marginale mandibularesectie resulteert in slechter lokale controle, disease-specific of overall survival en het is aannemelijk dat een marginale mandibularesectie resulteert in minder morbiditeit voor de patiënt.

Aanbeveling-2

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventie

Bij uitgebreide invasie van het corticale of medullaire bot of betrokkenheid van de canalis mandibularis is het aannemelijk dat een segmentale mandibularesectie nodig is om een veilige oncologische marge te behalen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Mandibulaire botinvasie bij primaire plaveiselcelcarcinomen van de mondholte is geassocieerd met een slechtere prognose. Bij de chirurgische behandeling van mondholtecarcinomen met mandibulaire botinvasie kan gekozen worden voor een marginale of een segmentale mandibularesectie. Een marginale mandibularesectie zorgt meestal voor een kleiner chirurgisch en een makkelijker te reconstrueren defect, maar gaat mogelijk ten koste van de chirurgische marges ten opzichte van de tumor. Het is daarom belangrijk om te bepalen wat het verschil in tumorcontrole is tussen een marginale en segmentale mandibularesectie bij carcinomen met invasie van het bot.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of marginal resection on the disease-specific survival rate, when compared with segmental resection in patients with bone invasion in mandible due to oral cavity carcinoma.

Sources: (Gou, 2018; Stoop, 2020) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of marginal resection on the overall survival rate, when compared with segmental resection in patients with bone invasion in mandible due to oral cavity carcinoma.

Sources: (Gou, 2018; Qiu, 2018; Sproll, 2020) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of marginal resection on the local control, when compared with segmental resection in patients with bone invasion in mandible due to oral cavity carcinoma.

Sources: (Gou, 2018) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of marginal resection on the recurrence rate, when compared with segmental resection in patients with bone invasion in mandible due to oral cavity carcinoma.

Sources: (Qiu, 2018; Sproll, 2020; Stoop, 2020) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of marginal resection on the surgical margin free resection, when compared with segmental resection in patients with bone invasion in mandible due to oral cavity carcinoma.

Sources: (Alam; 2019) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of marginal resection on the oral function (speech difficulty, trismus, mastication problems, and respiratory problems), when compared with segmental resection in patients with bone invasion in mandible due to oral cavity carcinoma.

Sources: (Alam, 2019) |

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of marginal resection on duration of surgery and complications when compared with segmental resection in patients with bone invasion in mandible due to oral cavity carcinoma. These outcome measures were not studied in the included studies. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

First, the systematic literature review is described. The additional observational studies are described thereafter.

The systematic review by Gou (2018) investigated the differences in survival rate and disease control in patients undergoing marginal mandibulectomy versus segmental mandibulectomy. RCTs and/or cohort studies in line with the research question of the SR were eligible for inclusion. The Cochrane Oral Health Group Trials Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE (via OVID), Embase, Cumulative Index for Nursing and Allied Health literature (CINAHL), Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Information (LILACS), Chinese BioMedical Literature Database (CBM), China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), VIP Database, Wanfang Database, Sciencepaper Online, System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe (SIGLE), and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, were searched to identify relevant studies until May 2016. Primary outcomes were “disease-free survival”, defined the length of time after primary treatment for a cancer until the time at which the patient was confirmed to have local, regional, or distant recurrence of the cancer, and “overall survival”, defined as the length of time that the patient diagnosed with the disease was still alive, starting from either the date of diagnosis or the start of treatment for the disease. Secondary outcomes were the 2-year/5-year survival rate and local control. In total data of 15 studies, including 1672 participants, were identified. Patient characteristics were not reported in 3 of the 15 studies. If it was reported, in total 873 males compared with 380 females aged (range) between 21-93 years were studied. All included studies were retrospective cohorts performed in Australia (n=2), Canada (n=1), China (n=1), Japan (n=1) Spain (n=1), UK (n=1), USA (n=8). Subgroup analyses are performed for patients with bone invasion. Important limitations of the current SR are (1) analyses were based on different types of mandibular invasion and different types of data (whether or not adjusted to the other independent prognostic factors), and (2) the article reported that all included studies had a high risk of bias.

Alam (2019) performed a prospective cohort study to investigate surgical outcomes and post-operative complications in patients undergoing marginal - or segmental resection for oral squamous cell carcinoma in Bangladesh. Between September 2008 and august 2013, 32 patients (9 males; median age of 40.5 years) were included, 20 of them underwent marginal resection and 12 a segmental resection. Mandibular invasion was present in 3 of the 20 patients in the marginal group compared to 10 of the 12 patients in the segmental group. Tumor stage was higher in patients who underwent segmental resection. The number of patients with margin free resection were reported per group, even as the number of patients with post-operative complications (i.e., speech difficulty, trismus, mastication problem, respiratory problem) per group. The current study is limited by the fact that data was not reported separately for patients with bone invasion, and no adjusted were made for potential prognostic factors.

Sproll (2020) conducted a retrospective cohort study to investigate results after marginal and segmental mandibulectomies in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Between 1996 and 2010 259 patients (178 male; mean age of 62.3 years) were included. Of them 35 underwent marginal versus 224 segmental mandibulectomy. Mandibular infiltration was found in 5 of the 35 patients undergoing marginal resection versus 105 of the224 patients undergoing segmental resection. The tumor stage was higher in patients receiving segmental mandibulectomy compared to marginal. Although the authors mentioned that there was no significant difference between patients receiving marginal mandibulectomy and those receiving segmental mandibulectomy regarding prognostic factors. The number of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma recurrence were reported, and percentages of patients achieving a 5-year overall survival were described. Although, the precise follow-up time was not mentioned for recurrence, only that the minimal follow-up time was 3-years. No information about function and/or quality of life was reported. The current study is limited by the fact that data was not reported separately for patients with bone invasion, and no adjusted were made for potential prognostic factors.

Stoop (2020) conducted a retrospective cohort study in the Netherlands. In total 229 patients undergone mandibular resection for oral squamous cell carcinoma between January 2000 and December 2017. Of them 19 were lost to follow-up. Therefore, analyses were based on 210 patients (127 males; mean age of 66.0 years), 59 had a marginal resection and 151 a segmental resection. Mandibular bone invasion was present in all patients. The group receiving a segmental resection had more defects classified as Ic, II, and IV (Brown’s classification, p=0.000), had larger tumors (p=0.001), and had a larger infiltration depth (p=0.000) compared to patients receiving a marginal resection. Local recurrence rates and disease-specific survival rates after 3 (and 5) years were reported. No information about surgery (for example duration), function and/or quality of life was reported. The current study is limited by the fact that no adjusted were made for potential prognostic factors.

Qiu (2018) conducted a retrospective cohort study of 82 patients (61 males; median age of 52 years) with oral squamous cell carcinoma who underwent mandibulectomy between January 2001 and January 2015. In total 39 underwent marginal mandibulectomy, and 43 underwent segmental mandibulectomy. Mandibular involvement was present in 29 of the 39 patients in the marginal resection group versus 23 of the43 patients in the segmental group. Patient and tumor characteristics were not different between the two groups at baseline. Local recurrence rates and survival rates after 3 (and 5) years were reported. No information about surgery (for example duration), function and/or quality of life was reported. The current study is limited by the fact that data was not reported separately for patients with bone invasion, and no adjusted were made for potential prognostic factors.

Results

Results are described per outcome measure, if possible relative risks (RR) were presented for a specific follow-up (i.e., achieving a specific outcome at a specific time). Subgroup analyses are performed for patients with bone invasion in line with the systematic review (SR) of Gou (2018). As it was not possible to obtain data which was adjusted for prognostic factors, no pooled effect estimates were illustrated.

Disease-specific survival rate

Disease-specific survival (DFS) was defined as ‘the length of time after primary treatment for a cancer until the time at which the patient was confirmed to have local, regional, or distant recurrence of the cancer’ by Gou (2018). Stoop (2020) did not specifically describe this outcome.

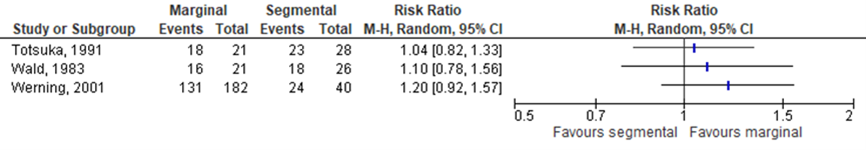

1.1 Disease-specific survival rate at 2-year

Three studies in the systematic review (Gou, 2018) reported the number of patients achieving DFS at 2-year, see Figure 11.2.1. Results showed that the relative risk point estimates of the individual studies were slightly in favor of in the intervention (i.e., marginal resection) group when compared to the control (i.e., segmental resection) group.

Figure 11.2.1 Forest plot for disease-specific survival rate at 2-year; marginal versus segmental resection

1.2 Disease-specific survival rate at 3-year with bone invasion.

One study (Stoop, 2020) reported the number of patients achieving DFS at 3-year. Results showed that the relative risk was slightly in favor of the intervention (i.e., marginal resection) group when compared to the control (i.e., segmental resection) group, with a relative risk of 1.10 (95%CI 0.91 to 1.33). The risk difference was 0.07 (95%CI -0.07 to 0.20). Importantly, only patients with bone invasion were included in this analysis.

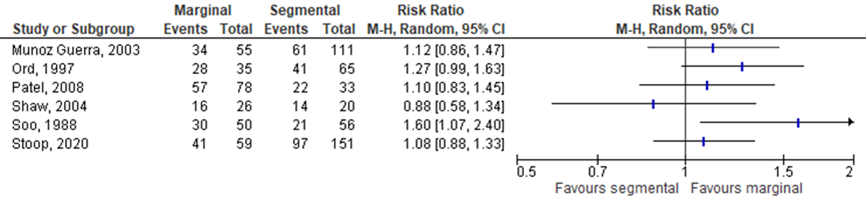

1.3 Disease-specific survival rate at 5-year

Five studies in the systematic review by Gou (2018) and the study of Stoop (2020) reported the number of patients achieving DFS at 5-year, see Figure 11.2.2 Results showed that the point estimates of the relative risks in individual studies were slightly in favor of the intervention (i.e., marginal resection) group compared to the control (i.e., segmental resection) group in 5 of the 6 studies.

Figure 11.2.2 Forest plot for disease-specific survival rate at 5-year; marginal versus segmental resection

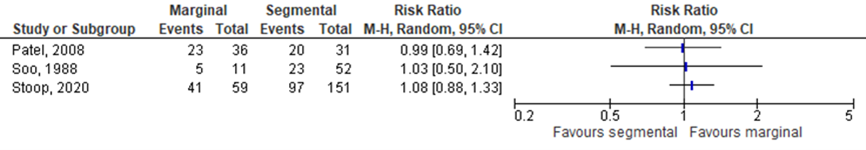

1.3.1 Disease-specific survival rate at 5-year with bone invasion.

Two studies in the systematic review by Gou (2018) and the study of Stoop (2020) reported the number of patients achieving DFS at 5-year in patients with bone invasion, see Figure 11.2.3. Results showed no differences between the intervention (i.e., marginal resection) group and control (i.e., segmental resection) group.

Figure 11.2.3 Forest plot for disease-specific survival rate at 5-year in patients with bone invasion; marginal versus segmental resection

2. Overall survival rate

Overall survival (OS) was defined as ‘the length of time that the patient diagnosed with the disease was still alive, starting from either the date of diagnosis or the start of treatment for the disease’ by Gou (2018). ‘Death associated with primary disease was the evaluated outcome used to determine the survival rate’ by Qiu (2018). Sproll (2020) did not specifically describe this outcome.

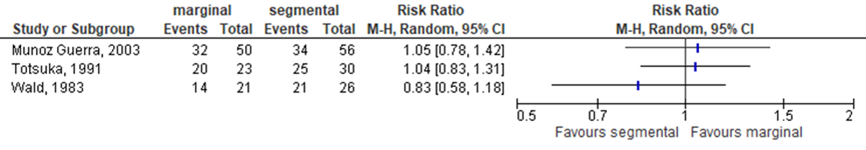

2.1 Overall survival rate at 2-year

Three studies in the systematic review by Gou (2018) reported the outcome OS at 2-year, see Figure 11.2.4. Results showed no differences between the intervention (i.e., marginal resection) group and control (i.e., segmental resection) group in 2 of the 3 studies. One of the 3 studies reported a relative risk indicating a more favorable effect in the segmental resectiongroup.

Figure 11.2.4 Forest plot for overall survival rate at 2-year; marginal versus segmental resection.

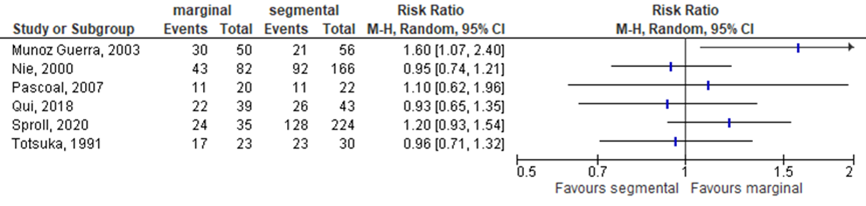

2.2. Overall survival rate at 5-year

Four studies in the systematic review by Gou (2018), the study by Qiu (2018), and by Sproll (2020) reported the outcome OS at 5-year, see Figure 11.2.5. Results of the individual trials were not consistent. Three of the 6 studies showed that the intervention group was more favorable (i.e., RR> 1), and the other 3 studies reported a more favorable outcome for the control group (i.e., RR< 1).

Figure 11.2.5 Forest plot for overall survival rate at 5-year; marginal versus segmental resection

3. Local control

No specific definition of local control was given by Gou (2018).

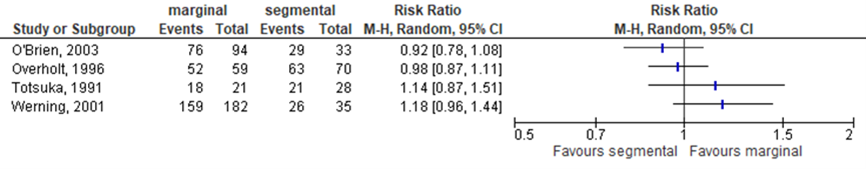

3.1 Local control at 2-year

Four studies in the systematic review by Gou (2018) reported the outcome local control at 2-year, see Figure 11.2.6. Results showed that the relative risk was slightly in favor of the intervention (i.e., marginal resection) group compared to the control (i.e., segmental resection) group in 2 of the 4 studies.

Figure 11.2.6 Forest plot for local control over 2-year; marginal versus segmental resection.

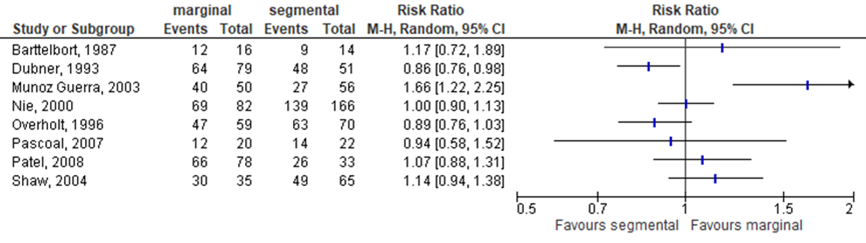

3.2 Local control at 5-year

Eight studies in the systematic review by Gou (2018) reported the local control at 5-year, see Figure 11.2.7. Results showed that the relative risk point estimates were slightly in favor of the intervention (i.e., marginal resection) group compared to the control (i.e., segmental resection) group in 4 of the 8 studies. No differences were observed in 1 study, and 3 studies showed a relative risk point estimate favoring the intervention group.

Figure 11.2.7 Forest plot for local control at 5-year; marginal versus segmental resection

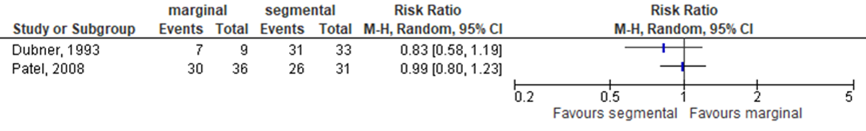

3.2.1 Local control at 5-year in patients with bone invasion.

Two studies in the SR reported the outcome local control at 5-year in patients with bone invasion, see Figure 8. Results showed that the relative risks were slightly lower in the intervention (i.e., marginal resection) group compared to the control (i.e., segmental resection) group.

Figure 11.2.8 Forest plot for local control at 5-year in patients with bone invasion; marginal versus segmental resection

4. Recurrence rate

No specific definition of the recurrence rate was given by Qiu (2018), Sproll (2020) and Stoop (2020).

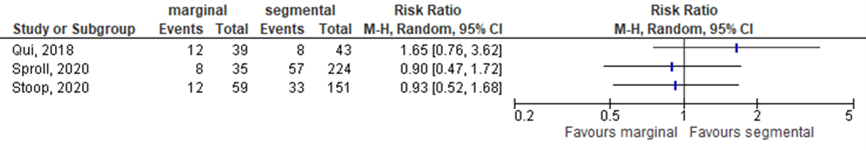

4.1 Recurrence rate at 3-year

Three studies (Qiu, 2018; Sproll, 2020; Stoop, 2020) reported the outcome recurrence rate at 3-year, see Figure 11.2.9. Results showed that the relative risk was in favor of the intervention (i.e., marginal resection) group compared to the control (i.e., segmental resection) group in 1 of 3 studies. The relative risk point estimape were slightly favouring the marginal resection in 2 of the 3 studies. Importantly, the study of Stoop (2020; RR 0.93 (95%CI 0.52 to 1.68) was performed in patients with bone invasion.

Figure 11.2.9 Forest plot for recurrence rate at 3-year; marginal versus segmental resection

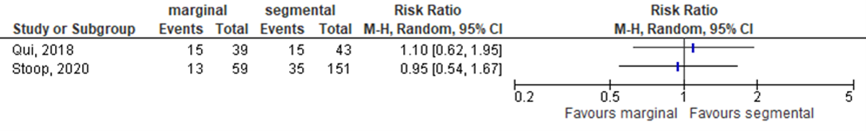

4.2 Recurrence rate at 5-year

Two studies (Qiu, 2018; Stoop, 2020) reported the outcome recurrence rate at 5-year, see Figure 7.2.10. Results showed no differences between the intervention (i.e., marginal resection) group and control (i.e., segmental resection) group.

Importantly, the study of Stoop (2020; RR 0.95 (95%CI 0.52 to 1.53) was performed in patients with bone invasion.

Figure 11.2.10 Forest plot for recurrence rate at 5-year; marginal versus segmental resection

5. Surgical margin free resection

One study (Alam, 2019) reported the outcome surgical margin free resection. Results showed that the RR was slightly in favor of the intervention (marginal resection) group compared to the control (segmental resection) group, with a relative risk of 1.07 (95%CI 0.72 to 1.58).

6. Oral function

Data about function was reported in one study (Alam, 2019). Although, Alam (2019) did not report specific information about how this data was assessed, for example via questionnaires.

6.1 Speech difficulty

The outcome ‘speech difficulty’ was reported in one (1/20) patients in the intervention (marginal resection) group and two (2/12) patients in the control (segmental resection) group, resulting in a relative risk of 0.33 (95%CI 0.03 to 2.97).

6.2 Trismus

Trismus was reported in eight (8/20) patients in the intervention group (marginal resection) group compared to seven (7/12) patients in the control (segmental resection) group, resulting in a relative risk of 0.69 (95%CI 0.33 to 1.41).

6.3 Mastication problems

The outcome ‘mastication problem’ was observed in nine (9/20) patients in the intervention (marginal resection) group and in eight (8/12) patients in the control (segmental resection) group, resulting in a relative risk of 0.68 (95%CI 0.36 to 1.27).

6.4 Respiratory problems

The outcome ‘respiratory problem’ was observed in two (2/20) patients in the intervention (marginal resection) group and in one (1/12) patient in the control (segmental resection) group, resulting in an RR of 1.20 (95%CI 0.12 to 11.87).

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence (GRADE method) is determined per comparison and outcome measure and is based on results from observational studies and therefore starts at level “low”. Subsequently, the level of evidence was downgraded if there were relevant shortcomings in one of the several GRADE domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. It was upgraded if there was a strong association, or a dose-response relation, and/or plausible (residual) confounding.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures duration of surgery, complications could not be assessed with GRADE. The outcome measures were not studied in the included studies.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure disease-specific survival rate, local control was downgraded by 3 levels because of imprecision (2 levels, 95%CI of the relative risk crosses both thresholds of clinical relevance), and risk of bias (1 level, high risk in the included studies due to inadequate adjustment for all important prognostic factors).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure overall survival, recurrence rate, surgical margin free resection, oral function was downgraded by 4 levels because of imprecision (2 levels, 2 levels, 95%CI of the relative risk crosses both thresholds of clinical relevance, and not meeting the optimal information size), indirectness (1 level, no subgroup analyses could be performed for patients with bone invasion) and risk of bias (1 level, high risk in the included studies due to inadequate adjustment for all important prognostic factors).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the benefits and harm of segmental resection versus marginal resection on tumor-free resection, recurrence rate, disease-specific survival, overall survival rate, function (for example oral rehabilitation, dental rehabilitation, swallowing function), duration surgery, or complications in patients with bone invasion in the mandible due to oral cavity carcinoma?

P: Patients with bone invasion in the mandible due to oral cavity carcinoma.

I: Marginal resection.

C: Segmental resection.

O: Tumor-free resection, recurrence rate, disease-specific survival, overall survival rate, oral function (i.e., oral rehabilitation, dental rehabilitation, swallowing function), duration surgery, complications.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline working group considered tumor-free resection, recurrence rate, disease-specific survival, overall survival rate as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and function (i.e., oral rehabilitation, dental rehabilitation, swallowing function), duration surgery, complications as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

A difference of 25% in the relative risk for dichotomous outcomes (i.e., RR 0.80 to 1.25) and 0.5 standard deviation (reported as SMD) for continuous outcomes was taken as a minimal clinically important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until April 19, 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 388 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: patients had bone invasion in mandible due to oral cavity carcinoma, a segmental resection was compared to a marginal resection of the mandibula, and at least one of the outcomes of interest was reported.

Twenty-five studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, twenty studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and five studies (i.e., 1 systematic review and 4 additional studies) were included.

Results

Five studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Alam, Mohammad Deedarul. "Influence of marginal and segmental bony resection on the local control of oral Squamous cell carcinoma involving the mandible." Bangladesh Journal of Medical Science 18.4 (2019): 801-807.

- Gou L, Yang W, Qiao X, Ye L, Yan K, Li L, Li C. Marginal or segmental mandibulectomy: treatment modality selection for oral cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018 Jan;47(1):1-10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2017.07.019. Epub 2017 Aug 18. PMID: 28823905.

- Qiu Y, Lin L, Shi B, Zhu X. Does Different Mandibulectomy (Marginal versus Segmental) Affect the Prognosis in Patients With Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018 May;76(5):1117-1122. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2017.11.014. Epub 2017 Nov 21. PMID: 29227794.

- Sproll CK, Holtmann H, Schorn LK, Jansen TM, Reifenberger J, Boeck I, Rana M, Kübler NR, Lommen J. Mandible handling in the surgical treatment of oral squamous cell carcinoma: lessons from clinical results after marginal and segmental mandibulectomy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2020 Jun;129(6):556-564. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2019.11.011. Epub 2019 Nov 27. PMID: 32102765.

- Stoop CC, de Bree R, Rosenberg AJWP, van Gemert JTM, Forouzanfar T, Van Cann EM. Locoregional recurrence rate and disease-specific survival following marginal versus segmental resection for oral squamous cell carcinoma with mandibular bone invasion. J Surg Oncol. 2020 Jun 9;122(4):64652. doi: 10.1002/jso.26054. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32516499; PMCID: PMC7496367.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Research question: What are the benefits and harm of segmental resection versus marginal resection on tumor-free resection, recurrence rate, disease-specific survival, overall survival rate, function (for example oral rehabilitation, dental rehabilitation, swallowing function), duration surgery, or complications in patients with bone invasion in the mandible due to oral cavity carcinoma?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Gou, 2018 |

SR and meta-analysis of cohort studies

Literature search up to May/2016

B: Barttelbort, 1987 C: Dubner, 1993 D: Munoz Guerra, 2003 E: Nie, 2000 F: O’Brien, 2003 G: Ord, 1997 H: Overholt, 1996 I: Pascoal, 2007 J: Patel, 2008 K: Shaw, 2004 L: Soo, 1988 M: Totsuka, 1991 N: Wald, 1983 O: Werning, 2001

Study design: cohort studies, retrospective

Setting and Country: A: Canada B: USA C: USA D: Spain E: China F: Australia G: USA H: USA I: USA J: Australia K: UK L: USA M: Japan N: USA O: USA

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: The systematic review was supported by the Outstanding Youth Foundation of Sichuan University (2082604194311). |

Inclusion criteria SR: (1) randomized, controlled clinical trials and cohort studies investigating the effectiveness of different mandibulectomy modalities (marginal mandibulectomy versus segmental mandibulectomy) were included. Studies focusing on the invasion of other bones (mandible not specified) were also considered if the percentage of invasion in the other bones besides the mandible did not exceed 10%. (2) all participants who underwent surgery for the treatment of OSCC or other malignant tumours of the oral cavity with different mandibulectomy modalities and with pathological results available for the resected mandible were included. (3) Intervention group: participants included those who underwent marginal mandibulectomies for the reservation of the mandible. Studies with neck dissection and/or reconstructive surgery performed if necessary were also considered. (4) Control group: participants included those who underwent a segmental, hemi, subtotal, or total mandibulectomy. Studies with neck dissection and/or reconstructive surgery performed if needed were also considered. (5) Outcome: disease-free survival and overall survival

Exclusion criteria SR: not according to inclusion criteria

15 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline: Number of patients total (i/c); A: 107 (37/70) B: 38 (21/17) C: 130 (79/51) D: 106 (50/56) E: 248 (82/166) F: 127 (94/33) G: 46 (26/20) H: 129 (59/70) I: 42 (20/22) J: 111 (78/33) K: 100 (35/36) L: 166 (55/111) M: 53 (23/30) N: 47 (21/26) O: 222 (182/40)

N, mean age A: 62 B: 59.3 C: - D: 57.7 E: 41.5 F: 61 G: 63.2 H: - I: 50.5 J: 63 K: 63 L: - M: 65 N: - O: 63

Sex, n male: A: 71 B: 34 C: - D: 89 E: 167 F: 97 G: 26 H: - I: 39 J: 81 K: 56 L: - M: 34 N: 33 O: 146

Groups comparable at baseline? No, please see Table 3 |

Describe intervention:

A to O: marginal mandibulectomy. Specific information about the procedure was not described in the article. |

Describe control:

A to O: segmental mandibulectomy. Specific information about the procedure was not described in the article. |

End-point of follow-up:

A: - B: 5-year C: 5-year D: 5-year E: 5-year F: 30 months G: 5-year H: 5-year I: 5-year J: 5-year K: 5-year L: 5-year M: 5-year N: 2-year O: 2-year

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: not known B: 16/14 C: 79/51 D: 50/56 E: 82/166 F: not known G: 26/20 H: 59/70 I: 20/22 J: 78/333 K: 35/65 L: 55/61 M: 23/30 N: 33/20 O: 146/76

|

Outcome measure-1 Defined as 5-year DFS rate;

Effect measure: RR, (95% CI): D: 1.60 (1.07; 2.40) G: 0.88 (0.58; 1.34) J: 1.10 (0.83; 1.45) K: 1.27 (0.99; 1.63) L: 1.12 (0.86; 1.47)

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 1.19 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.37) favoring marginal mandibulectomy Heterogeneity (I2): 17%

Outcome measure-2 Defined as DFS rate; A: 2.06 (0.84; 5.05) F: 0.69 (0.23; 2.03)

Outcome measure-3 Defined as 5-year overall survival rate;

D: 1.60 (1.07; 2.40) E: 0.95 (0.74; 1.21) I: 1.10 (0.62; 1.96) M: 0.96 (0.71; 1.32)

Outcome measure-4 Defined as local control at 5-year;

B: 1.17 (0.72; 1.89) C: 0.86 (0.76; 0.98) D: 1.66 (1.22; 2.25) E: 1.00 (0.90; 1.13) H: 0.89 (0.76; 1.03) I: 0.94 (0.58; 1.52) J: 1.07 (0.88; 1.31) K: 1.14 (0.94; 1.38)

|

Facultative:

Brief description of author’s conclusion “Based on the primary outcomes; the study indicates that a marginal mandibulectomy may be recommended for cases with no invasion or superficial invasion of the mandibular cortex, and a segmental mandibulectomy may be a more reasonable choice for patients with extensive mandibular cortex invasion or medullary invasion.”

Limitations; only retrospective cohort studies, high risk of bias, heterogeneity in main analyses. The analyses were based on different types of mandibular invasion and different types of data (whether or not adjusted to the other independent prognostic factors). Level of evidence: the GRADE method was not applied. A risk of bias (RoB) assessment showed that the RoB was high in all included studies.

Heterogeneity: Subgroup analyses were performed based on medullary or bone invasion |

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Gou, 2018 |

Yes, aim of study is clearly defined evenas inclusion criteria. |

Yes, search strategy is clearly defined. |

Unclear, description of the included studies is clearly described in the methods section and Figure 1. However, this was lacking for the excluded studies. |

Yes, this is clearly described in Table 2 of the paper. |

Unclear, not known if ‘raw’ data is used or adjusted data of the individual studies |

Yes, only a risk of bias table is included. |

Unclear, it is not reported if adjustments were performed for prognostic factors, patient characteristics at baseline are not provided for all studies as this data was lacking in the individual trials. In addition the procedure of the surgeries were not provided. |

Yes, with Egger and Begg test. |

Yes, none. |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined.

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched.

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons.

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported.

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs).

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table et cetera).

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (for example Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (for example funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (for example Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, case series))1

This table is also suitable for diagnostic studies (screening studies) that compare the effectiveness of two or more tests. This only applies if the test is included as part of a test-and-treat strategy - otherwise the evidence table for studies of diagnostic test accuracy should be used.

Research question: What are the benefits and harm of segmental resection versus marginal resection on tumor-free resection, recurrence rate, disease-specific survival, overall survival rate, function (for example oral rehabilitation, dental rehabilitation, swallowing function), duration surgery, or complications in patients with bone invasion in the mandible due to oral cavity carcinoma?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Qui, 2018 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort study

Setting and country: Hospital setting, China

Funding and conflicts of interest: None. |

Inclusion criteria: no distant metastasis at admission or during the course of therapy; no other preoperative therapy; postoperative follow-up of not less than 6 months; and complete clinical and pathologic information, including gender, age, staging, treatment, curative effect, and recurrence.

Exclusion criteria: other serious systemic diseases.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 39 Control: 43

Important prognostic factors2: For example Age > 60y I: 41% C: 47%

Sex: In total 75% males.

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, no statistically significant differences. |

Describe intervention: Marginal resection (MG);

partial resection of the height of the mandible that would not disrupt its continuity.

|

Describe control Segmental resection (SG);

en bloc resection of the entire height of the mandibular body.

The choice of the operating surgeon was based on an evaluation of the clinical and radiologic extent of the bone, invasion margins of at least 1.5 cm beyond all clinically evident tumor using intraoperative frozen section, and the vertical height of the remaining mandible. There should be sufficient height in the mandible to leave a functional lower border. For patients with lower alveolar nerve invasion, the authors preferred mandibular hemiresection as part of SG.

|

Length of follow-up: 3 to 5 years.

Loss-to-follow-up: N.a. retrospective design.

Incomplete outcome data: N.a. retrospective design.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Local recurrence rates; 3-year MG; 29.1% - 12 SG; 18.4% - 8

RR; 1.65 (95%CI 0.76 to 3.62)

5-year MG; 39.7% - 15 SG; 34.2% - 15

RR; 1.10 (95%CI 0.62 to 1.95)

Overall survival rates; 3-year MG; 75.2% - 30 SG; 69.2% - 30

RR; 1.10 (95%CI 0.85 to 1.43)

5-year MG; 55.5% - 22 SG; 60.7% - 26

RR; 0.93 (95%CI 0.65 to 1.35) |

*it is not known how many patients had a follow-up of 3 years and how many a follow-up of 5 years. Only % reported for the outcomes of interest, no RR.

Outcomes regarding function and/or quality of life are not assessed. |

|

Stoop, 2020 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort study

Setting and country: Hospital setting, the Netherlands

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported. |

Inclusion criteria: patients who had undergone marginal or segmental resection at a single center with a head and neck cancer service, the University Medical Center Utrecht, between January 2000 and December 2017 for first primary OSCC, with mandibular invasion confirmed by histopathological examination of the resection specimen.

Exclusion criteria: patients lost to follow up within 12 months, and patients with missing clinical or histopathological information other than invasive growth pattern or tumor grade.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 59 Control: 151

Important prognostic factors2: Age I: 66.53 years C: 65.17 years

Sex: In total 60% males.

Groups comparable at baseline? No, not for sex and tumor location. |

Describe intervention: Marginal resection (MG);

was performed when complete removal of the tumor in the bone and soft tissues was deemed feasible, on the condition that at least 1 cm bone height of the inferior border of the mandible could be preserved.

|

Describe control Segmental resection (SG);

was performed in case less than 1 cm bone height of the inferior border of the mandible was estimated to remain.

|

Length of follow-up: 3 to 5 years.

Loss-to-follow-up: N.a. retrospective design. Patients lost to follow up were excluded beforehand.

Incomplete outcome data: N.a. retrospective design.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Local recurrence rates; 3-year MG; 20.3% - 12 SG; 21.9% - 33

RR; 0.93 (95%CI 0.52 to 1.68)

5-year MG; 22.0% - 13 SG; 23.2% - 35

RR; 0.95 (95%CI 0.54 to 1.67)

Disease-free survival rates; 3-year MG; 72.9% - 43 SG; 66.2% - 100

RR; 1.10 (95%CI 0.91 to 1.33)

5-year MG; 69.5% - 41 SG; 64.2% - 97

RR; 1.08 (95%CI 0.88 to 1.33)

|

*It is not known how many patients had a follow-up of 3 years and how many a follow-up of 5 years. Only % reported for the outcomes of interest, no RR.

Outcomes regarding function and/or quality of life are not assessed.

** all patients with bone invasion. |

|

Sproll, 2020 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort study

Setting and country: Hospital setting, Germany

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported. |

Inclusion criteria: diagnosed with OSCC and treated surgically by either marginal or segmental mandibulectomy between 1996 and 2010 at the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at Düsseldorf University Hospital. Also, patients who had been treated for OSCC and now had secondary OSCC.

Exclusion criteria: Not mentioned.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 35 Control: 224

Important prognostic factors2: Mean age overall was 62.3 years. Over time the average age increase from 57.7 to 69.2.

Sex: In total 68% males.

Groups comparable at baseline? Not clearly described. |

Describe intervention: Marginal resection (MG);

No details about surgery.

|

Describe control Segmental resection (SG);

No details about surgery.

|

Length of follow-up: At least 3 years.

Loss-to-follow-up: N.a. retrospective design.

Incomplete outcome data: N.a. retrospective design. |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Local recurrence rates; At least 3-year MG; 8 SG; 57

RR; 0.90 (95%CI 0.47 to 1.72)

Overall survival rates; 5-year MG; 68% - 24 SG; 57% - 128

RR; 1.20 (95%CI 0.93 to 1.54)

|

*the follow-up time per individual is not reported. Only the number of patients or % of patients are reported for the outcomes of interest, no RR.

Outcomes regarding function and/or quality of life are not assessed. |

|

Alam, 2019 |

Type of study: Prospective cohort study

Setting and country: Hospital setting, Bangladesh

Funding and conflicts of interest: None. |

Inclusion criteria: oral squamous cell carcinoma confirm by histopathology and clinical assessment. Patients are with radiological findings of bone invasion in the lower jaw.

Exclusion criteria: not fit for major surgical intervention or associated systemic diseases. Non co-operative and psychotic patient or patients refused to surgical intervention.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 20 Control: 12

Important prognostic factors2: Mean (sd) age in years; I: 39.7 (14) C: 42.3 (13.8)

Sex: In total 28% males.

Groups comparable at baseline? Not for tumor stage. |

Describe intervention: Marginal resection (MG);

No details about surgery.

The term ‘marginal resection’ was reserved for cancers close to the mandible with no invasion, minimal cortical invasion, or with early erosive invasion, when bony continuity has preserved.

|

Describe control Segmental resection (SG);

No details about surgery.

Segmental resection or en block resection of a variable length of mandible was considered in patient with evidence of cancerous invasion. |

Length of follow-up: At least 12 months.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not clearly described, only patients with a minimal follow-up of 12 months were included.

Incomplete outcome data: Not clearly described, only patients with a minimal follow-up of 12 months were included.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Surgical margin free (tumor-free resection); MG; 16 SG; 9

RR; 1.07 (95%CI 0.72 to 1.58)

Post-operative morbidity; Speech difficulty; MG; 1 SG; 2

RR; 0.30 (95%CI 0.03 to 2.97)

Trismus; MG; 8 SG; 7

RR; 0.69 (95%CI 0.33 to 1.41)

Mastication problem; MG; 9 SG; 8

RR; 0.68 (95%CI 0.36 to 1.27)

Respiratory problem; MG; 2 SG; 1

RR; 1.20 (95% CI 0.12 to 11.87) |

Relative short minimal follow-up time. *the follow-up time per individual is not reported. Only the number of patients or % of patients reported for the outcomes of interest, no RR.

Outcomes regarding function and/or quality of life are not assessed. |

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (observational: non-randomized clinical trials, cohort and case-control studies)

Research question:

|

Study reference

(first author, year of publication) |

Bias due to a non-representative or ill-defined sample of patients?1

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to insufficiently long, or incomplete follow-up, or differences in follow-up between treatment groups?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to ill-defined or inadequately measured outcome ?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate adjustment for all important prognostic factors?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Qui, 2018 |

Unlikely, strict in- and exclusion criteria. |

Unclear, it is only mentioned that patients were censored if they were lost to follow up. However, it is not known if this was different between de groups.

|

Likely, the follow-up time per patient not mentioned. It is also not known how many patients are included in the analyses for survival rates. |

Likely, patients’ characteristics at baseline are comparable (as stated by the authors). Although, no adjustments were made for prognostic factors. |

|

Stoop, 2020 |

Unlikely, strict in- and exclusion criteria. |

Unclear, patients which were lost to follow up within 12 months were excluded from the analysis. It is not known if these patients were allocated to the intervention or control group. |

Likely, the follow-up time per patient not mentioned. It is also not known how many patients are included in the analyses for survival rates. |

Likely, patients’ characteristics at baseline are not comparable, and no adjustments were made for prognostic factors. |

|

Sproll, 2020 |

Unlikely, strict in- and exclusion criteria. |

Unlikely, all patients had a minimum follow-up time of 3 years. |

Likely, the follow-up time per patient not mentioned for the outcome recurrence rate. It is also not known how many patients are included in the analyses for survival rates. |

Likely, no overview of patients’ characteristics at baseline is provided, and no adjustments were made for prognostic factors. |

|

Alam, 2019 |

Unlikely, strict in- and exclusion criteria. |

Unlikely, all patients had a follow-up time of 2 years. |

Unlikely, the outcomes of interest are collected after surgery. |

Likely, patients’ characteristics at baseline are not comparable for ‘tumorstage’, and no adjustments were made for prognostic factors. |

- Failure to develop and apply appropriate eligibility criteria: a) case-control study: under- or over-matching in case-control studies; b) cohort study: selection of exposed and unexposed from different populations.

- Bias is likely if: the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large; or differs between treatment groups; or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups; or length of follow-up differs between treatment groups or is too short. The risk of bias is unclear if: the number of patients lost to follow-up; or the reasons why, are not reported.

- Flawed measurement, or differences in measurement of outcome in treatment and control group; bias may also result from a lack of blinding of those assessing outcomes (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Failure to adequately measure all known prognostic factors and/or failure to adequately adjust for these factors in multivariate statistical analysis.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Nishi, 2018 |

Comparison between tumor stage |

|

Naqvi, 2020 |

Only segmental resection |

|

Löfstrand, 2018 |

No comparison |

|

Yue, 2020 |

Prediction model |

|

Du, 2019 |

Only marginal resection |

|

Petrovic, 2019 |

Only marginal resection |

|

Petrovic, 2017 |

Only marginal resection |

|

Okuyama, 2016 |

Only marginal resection |

|

Feng, 2019 |

Modified mandibulectomy |

|

Petrovic, 2019 |

Outcomes not in line with PICO |

|

Suresh, 2019 |

Only marginal resection |

|

Suresh, 2019 |

Double |

|

Weijs, 2016 |

Not in line with PICO |

|

Petrovic, 2019 |

Only segmental mandibulectomy |

|

Weitz, 2016 |

Only segmental mandibulectomy |

|

Smits, 2018 |

Only segmental mandibulectomy |

|

Shen, 2018 |

Only segmental mandibulectomy |

|

Sukegawa, 2020 |

Only marginal resection |

|

Ma, 2020 |

No comparison |

|

Padiyar, 2018 |

Not comparison of interest (hemi-mandibulectomy versus marginal mandibulectomy) |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 08-01-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 20-09-2023

De geldigheid van de richtlijnmodule komt te vervallen indien nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding zijn een herzieningstraject te starten.

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met hoofd-halstumoren.

Werkgroep

- Prof. Dr. R. de Bree, KNO-arts/hoofd-halschirurg, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, NVKNO (voorzitter)

- Dr. M.B. Karakullukcu, KNO-arts/hoofd-halschirurg, NKI, Amsterdam, NVKNO

- Dr. H.P. Verschuur, KNO-arts/hoofd-halschirurg, Haaglanden MC, Den Haag, NVKNO

- Dr. M. Walenkamp, AIOS-KNO, LUMC, Leiden, NVKNO

- Dr. A. Sewnaik, KNO-arts/hoofd-halschirurg, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, NVKNO

- Drs. L.H.E. Karssemakers, MKA-chirurg-oncoloog/hoofd-hals chirurg, NKI, Amsterdam, NVMKA

- Prof. dr. M.J.H. Witjes, MKA-chirurg-oncoloog, UMC Groningen, Groningen, NVMKA

- Drs. L.A.A. Vaassen, MKA-chirurg-oncoloog, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht, NVMKA

- Drs. W.L.J. Weijs, MKA-chirurg-oncoloog, Radboud UMC, Nijmegen, NVKMA

- Drs. E.M. Zwijnenburg, Radiotherapeut-oncoloog, Radboud UMC, Nijmegen, NVRO

- Dr. A. Al-Mamgani, Radiotherapeut-oncoloog, NKI, Amsterdam, NVRO

- Prof. Dr. C.H.J. Terhaard, Radiotherapeut-oncoloog, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, NVRO

- Drs. J.G.M. Van den Hoek, Radiotherapeut-oncoloog, UMC Groningen, Groningen, NVRO

- Dr. E. Van Meerten, Internist-oncoloog, Erasmus MC Kanker Instituut, Rotterdam, NIV

- Dr. M. Slingerland, Internist-oncoloog, LUMC, Leiden, NIV

- Drs. M.A. Huijing, Plastisch Chirurg, UMC Groningen, Groningen, NVPC

- Prof. Dr. S.M. Willems, Klinisch patholoog, UMC Groningen, Groningen, NVVP

- Prof. Dr. E. Bloemena, Klinisch patholoog, Amsterdam UMC, locatie Vumc, Amsterdam, NVVP

- R.A. Burdorf, Voorzitter dagelijks bestuur patiëntenvereniging, Patiëntenvereniging HOOFD-HALS, PvHH

- P.S. Verdouw, Hoofd infocentrum patiëntenvereniging, Patiëntenvereniging HOOFD-HALS, PvHH

- A.A.M. Goossens, Verpleegkundig specialist oncologie, Haaglanden MC, Den Haag, V&VN

- Dr. P. de Graaf, Radioloog, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, NVvR

- Dr. W.V. Vogel, Nucleair geneeskundige/radiotherapeut-oncoloog, NKI, Amsterdam, NVNG

- Drs. G.J.C. Zwezerijnen, Nucleair geneeskundige, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, NVNG

Klankbordgroep

- Dr. C.M. Speksnijder, Fysiotherapeut/Bewegingswetenschapper/Epidemioloog, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, KNGF

- Ir. A. Kok, Diëtist, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, NVD

- Dr. M.M. Hakkesteegt, Logopedist, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, NVvLF

- Drs. D.J.M. Buurman, Tandarts-MFP, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht, KNMT

- W. Van der Groot-Roggen, Mondhygiënist, UMC Groningen, Groningen, NVvM

- Drs. D.J.S. Dona, Bedrijfsarts/Klinisch arbeidsgeneeskundige oncologie, Radboud UMC, Nijmegen, NVKA

- Dr. M. Sloots, Ergotherapeut, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht (tot november 2021), EN

- A.C.P. Kauerz-de Rooij, Ergotherapeut, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht (vanaf januari 2022), EN

- J. Poelstra, Medisch maatschappelijk werkster, op persoonlijke titel

- Dr. K.S. Versteeg, Internist, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, NIV ouderengeneeskunde

Met dank aan

- Drs. Maarten Donswijk, Nucleair geneeskundige, AVL

- Dr. José Hardillo, KNO-arts/hoofd-halschirurg, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam

- Drs. Dominique Monserez, KNO-arts/hoofd-halschirurg, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. J. Boschman, Senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. C. Gaasterland, Adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. A. Van der Hout, Adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. L. Oostendorp, Adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. M. Oerbekke, Adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. A. Hoeven, Junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. N. Elbert, Adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Bree, de |

KNO-arts/hoofd-halschirurg, UMC Utrecht |

* Lid Algemeen Bestuur Patiëntenvereniging Hoofd-Hals (onbetaald) * Voorzitter Research Stuurgroep NWHHT * Lid Richtlijnen commissie NWHHT * Lid dagelijks bestuur NWHHT * Lid Clinical Audit Board van de Dutch Head and Neck Audit (DHNA) * Lid wetenschappelijk adviescommissie DORP * Voorzitter Adviescommissie onderzoek hoofd-halskanker (IKNL/PALGA/DHNA/NWHHT) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Slingerland |

Internist-oncoloog, LUMC |

* 2018-present: Treasurer of the "Dutch Association of Medical Oncology"(NVMO - vacancy fees) * 2018-present: Member of the "Dutch Working Group for Head-Neck Tumors" (NWHHT-Systemic therapy) * 2016-present: Member of the 'Dutch Working Group for Head-Neck Tumors" (NWHHT - study group steering group (coordinating)) * 2016-present: Member of the "Dutch Working Group for Head-Neck Tumors" (NWHHT - Elderly Platform) * 2012-present: Member "Working Group for Head-Neck Tumors" (WHHT) "University Cancer Centre"(UCK) Leiden - Den Haag * 2019: Member CAB DHNA |

Deelname Nationaal expert forum hoofd-halskanker MSD dd 2-5-2018

* Deelname Checkmate studie, sponsor Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS): An open label, randomized phase 3 clinical trial of nivolumab versus therapy of investigator's choice in recurrent or metastatic platinum-refractory squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) * Deelname Commence studie, sponsor Radboud University, in collaboration with Merck Serono International SA (among several Dutch medical centers): A phase lB-II study of the combination of cetuximab and methotrexate in recurrent of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. A study of the Dutch Head and Neck Society, MOHN01/COMMENCE study. * Deelname HESPECTA studie: Phase I study: to determine the biological activity of two HPV16E6 specific peptides coupled to Amplivant®, a Toll-like receptor ligand in non-metastatic patients treated for HPV16-positive head and neck cancer. * Deelname PINCH studie (nog niet open): PD-L1 ImagiNg to predict durvalumab treatment response in HNSCC (PINCH) trial; patiënten met biopt bewezen locally recurrent of gemetastaseerd HNSCC * Deelname ISA 101b-HN-01-17 studie (nog niet open): A randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 2 Study of Cemiplimab versus the combination of Cemiplimab with ISA101b in the Treatment of Subjects. |

In de werkgroep participeren 2 internist-oncologen, zodat één van beide de voortrekker is van modules over systemische therapie. Actie: werkgroeplid is uitgesloten van besluitvorming bij modules die betrekking hebben op de onderwerpen van de gemelde onderzoeken: nivolumab, cetuximab + methotrexaat, Amplivant, durvalumab, cemiplimab. |

|

Meerten, van |

Internist-oncoloog, Erasmus MC Kanker Instituut |

Geen |

Op dit moment Principal Investigator voor NL van gerandomiseerde fase III trial naar toegevoegde waarde van pembrolizumab aan chemoradiotherapie bij patiënten met gevorderd hoofdhalskanker. Sponsor: GlaxoSmithKline Research & Development Ltd. Studie is nog lopend, resultaten zullen pas bekend zijn na verschijning van de richtlijn.

In toekomst mogelijk participatie aan door industrie gesponsorde studies op gebied van behandeling van hoofdhalskanker |

In de werkgroep participeren 2 internist-oncologen, zodat één van beide de voortrekker is van modules over systemische therapie. Actie: werkgroeplid is uitgesloten van besluitvorming bij modules die betrekking hebben op het onderwerp van het gemelde onderzoeken: de toegevoegde waarde van pembrolizumab bij patiënten met gevorderd hoofdhalskanker. |

|

Huijing |

Plastisch chirurg, UMC Groningen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Sewnaik |

KNO-arts/hoofd Hals chirurg, Erasmus MC |

Sectorhoofd Hoofd-Hals chirurgie |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Vaassen |

MKA-chirurg-oncoloog, Maastricht UMC+ / CBT Zuid-Limburg |

*Lid Bestuur NVMKA *Waarnemend hoofd MKA-chirurgie MUMC |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Witjes |

MKA-chirurg-oncoloog, UMC Groningen |

Geen |

PI van KWF grant: RUG 2015 -8084: Image guided surgery for margin assessment of head & neck Cancer using cetuximab-IRDye800 cONjugate (ICON)

geen financieel belang |

Geen. Financiering door KWF werd niet als een belang ingeschat. |

|

Bloemena |

Klinisch patholoog, Amsterdam UMC (locatie Vumc) / Radboud UMC / Academisch Centrum voor Tandheelkunde Amsterdam (ACTA) |

* Lid bestuur Nederlandse Vereniging voor Pathologie (NVVP) – vacatiegeld (tot 1-12-20) * Voorzitter Commissie Bij- en Nascholing (NVVP) * Voorzitter (tot 1-12-20) Wetenschappelijke Raad PALGA - onbezoldigd |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Willems |

Klinisch patholoog, UMC Groningen |

Vice-vz PALGA, AB NWHHT, CAB DHNA, mede-vz en oprichter expertisegroep HH pathologie NL, Hoofdhalspathologie UMC Groningen |

PDL1 trainer NL voor MSD Onderzoeksfinanciering van Pfizer, Roche, MSD, BMS, Lilly, Novartis, Bayer, Amge, AstraZeneca |

Geen |

|

Karakullukcu |

KNO-arts/hoofd-hals chirurg, NKI/AVL |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Verschuur |

KNO-arts/Hoofd-hals chirurg, Haaglanden MC |

* Opleider KNO-artsen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Walenkamp |

AIOS KNO, LUMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Al-Mamgani |

Radiotherapeut-oncoloog, NKI/AVL |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Terhaard |

Radiotherapeut-oncoloog, UMC Utrecht |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Hoek, van den |

Radiotherapeut-oncoloog UMCG |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Zwijnenburg |

Radiotherapeut, Hoofd-hals Radboud UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Burdorf |

Patiëntvertegenwoordiger |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Verdouw |

Hoofd Infocentrum patiëntenvereniging HOOFD HALS |

Geen |

Werkzaam bij de patiëntenvereniging. De achterban heeft baat bij een herziening van de richtlijn |

Geen |

|

Karssemakers |

Hoofd-hals chirurg NKI/AVL

MKA-chirurg-oncoloog Amsterdam UMC (locatie AMC) / vakgroep kaakchirurgie Amsterdam West |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Goossens |

Verpleegkundig specialist, Haaglanden Medisch Centrum (HMC) |

* Bestuurslid (penningmeester) PWHHT (onbetaald) * Lid Commissie voorlichting PVHH (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Zwezerijnen |

Nucleair geneeskundige, Amsterdam UMC (locatie Vumc)

PhD kandidaat, Amsterdam UMC (locatie Vumc) |

Lid als nucleair geneeskundige in HOVON imaging werkgroep (bespreken van richtlijnen en opzetten/uitvoeren van wetenschappelijke studies met betrekking tot beeldvorming in de hematologie); onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Vogel |

Nucleair geneeskundige/radiotherapeut-oncoloog, AVL |

Geen |

In de afgelopen jaren incidenteel advies of onderwijs, betaald door Bayer, maar niet gerelateerd aan hoofd-hals

KWF-grant speekselklier toxiteit na behandeling. Geen belang bij de richtlijn |

Geen |

|

Graaf, de |

Radioloog, Amsterdam UMC (locatie Vumc) |

Bestuurslid sectie Hoofd-Hals radiologie (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Weijs |

MKA-chirurg-oncoloog, Radboudumc |

MKA-chirurg, Weijsheidstand B.V. Werkzaam als algemeen praktiserend MKA-chirurg, betaald (0,1 fte) |

Geen |

Geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van de patiëntenvereniging HOOFD-HALS (PVHH) voor de Invitational conference en met afgevaardigden van de PVHH in de werkgroep. Het verslag hiervan (zie aanverwante producten) is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de patiëntenvereniging HOOFD-HALS en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met hoofd-halstumoren. De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbeveling(en) uit de eerdere richtlijnmodule (NVKNO, 2014) op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door de patiëntenvereniging en genodigde partijen tijdens de Invitational conference (zie aanverwante producten voor het verslag van de Invitational conference). Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

Waar relevant is er specifieke aandacht voor de (oudere) kwetsbare patiëntengroep in de overwegingen en wordt er ingegaan op de begeleiding en behandeling van deze patiënten.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE-gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodules is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen.

Herziening 2023

De werkgroep besloot na het bestuderen van alle aanbevelingen van de richtlijn Hoofd-halstumoren om in de periode 2019-2023 te werken aan de volgende updates:

- De indeling van de richtlijn is aangepast en per tumortype zijn alle relevante modules te vinden. Sommige modules (zoals Systemische therapie bij radiotherapie lokaal gevorderde tumoren) zijn daarom bij zowel Orofarynxcarcinoom, Hypofarynxcarcinoom, als Larynxcarcinoom in de richtlijn te vinden.

- In de meest recente UICC/AJCC classificatie is lipcarcinoom niet langer ondergebracht bij mondholte (TNM7) maar bij huid (TNM8). Dit brengt een verandering in stadiëring (volgens TNM8) met zich mee, maar niet in behandeling (volgens TNM7).