Beeldvorming of histologie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de rol van beeldvorming (dat wil zeggen MRI of CT) bij patiënten verdacht van een levertumor zonder bekende levercirrose?

Aanbeveling

Verricht een tumorbiopt bij patiënten met een verdenking op een HCC in een niet-cirrotische lever, gezien alléén beeldvorming niet voldoende is.

Bespreek de beeldvorming en besluitvorming omtrent tumorbiopsie in een MDO (zie SONCOS 2023).

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er werden drie primaire studies geselecteerd in de literatuuranalyse over de diagnostische accuratesse van CT en/of MRI voor het detecteren van hepatocellulaire carcinomen bij patiënten met of zonder achterliggende leverziekten in een niet cirrotische lever (Kim, 2011; Fischer, 2015; Lin, 2016).

Er was een redelijk tot zeer laag vertrouwen in de accuratesse parameters van CT-scans vanwege een risico op bias in de primaire studies(zoals beoordeeld door Nadarevic (2021) en (2022)) en de imprecisie. De imprecisie varieert tussen analyses en er is oplopend meer vertrouwen in de gerapporteerde accuratesse schatters van CT-scans naarmate de groepen in de analyses groter worden en hiermee de precisie van de accuratesse schatter toeneemt. Kleinere groepen in de analyses zijn bijvoorbeeld patiënten met een 1-2cm HCC (ten opzichte van >2cm) en groepen patiënten met een F0 of F0-1 METAVIR score (ten opzichte van F0-3) (Lin, 2016), waar er minder vertrouwen bestaat in de gerapporteerde accuratesse schatters door meer imprecisie. Naarmate er minder deelnemers in de sub-analyses zaten nam het vertrouwen af tot (zeer) laag. Hetzelfde patroon is zichtbaar voor de positief en negatief voorspellende waarde (Lin, 2016). Doordat er minder patiënten met kleinere hepatocellulair carcinomen (dat wil zeggen 1 tot 2 centimeter) dan met grotere hepatocellulaire carcinomen (dat wil zeggen >2 centimeter) in de steekproef van Lin (2016) zitten, zijn de accuratesseschatters in de sub-analyses voor kleinere hepatocellulair carcinomen minder precies dan die voor de grotere carcinomen. Kim (2011) deelde de steekproef met laesies groter dan twee centimeter, maar zonder levercirrose, op in een hoog-risico groep (sensitiviteit: 0,82 (95%BHI: 0,67 tot 0,91), specificiteit: 0,92 (95%BHI: 0,62 tot 0,99)) en een laag-risico groep (sensitiviteit: 0,87 (95%BHI: 0,60 tot 0,98), specificiteit: 0,90 (95%BHI: 0,68 tot 0,98)).

Voor beeldvorming met MR was er een zeer laag vertrouwen in de accuratesse parameters door risico op vertekening en imprecisie. Fischer (2015) vond vier MR beeldkenmerken die geassocieerd waren met hepatocellulair carcinomen bij patiënten zonder levercirrose en rapporteerde de diagnostische accuratesse: hypointens op T1 (sensitiviteit: 0,78 (95%BHI: 0,65 tot 0,88), specificiteit: 0.63 (95%CI: 0.49 tot 0.64)), niet isointens op T2 (sensitiviteit: 0,85 (95%BHI: 0,73 tot 0,94)), geen centrale aankleuring (sensitiviteit: 0,69 (95%BHI: 0,55 tot 0,81), specificiteit: 0,73 (95%BHI: 0,59 tot 0,84)), en de aanwezigheid van satelliet laesies (sensitiviteit: 0,24 (95%BHI: 0,13 tot 0,37), specificiteit: 0,96 (95%BHI: 0,87 tot 1,00)). Wanneer twee van de vier kenmerken positief zijn was de sensitiviteit 0,98 en de specificiteit 0,75. De 95% betrouwbaarheidsintervallen werden hier niet bij gerapporteerd en konden niet worden berekend. Lin (2016) gaf ook de accuratesse weer van MRI. Net als bij de accuratesse van CT-scans was imprecisie aanwezig in meer of mindere mate en afhankelijk van de sub-analyses. Schattingen waren preciezer voor grotere hepatocellulair carcinomen (>2 centimeter) dan voor kleinere (1 tot 2 centimeter). Een soortgelijk patroon is te zien wanneer de groepen groter worden bij sub-analyses op basis van de METAVIR score, waarbij de geanalyseerde groep stapsgewijs werd uitgebreid met een hogere mate van fibrotisering (dat wil zeggen F0, F0-1, F0-2, F0-F3). Hoe meer imprecisie er aanwezig is, hoe onzekerder men is over de accuratesseschatter.

Samenvattend is de accuratesse de diagnose van HCC op beeldvorming (CT of MRI) redelijk, maar onvoldoende om bij niet-cirrotische levers af te zien van een tumorbiopsie.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

Het belangrijkste doel van het verrichten van een tumorbiopsie is meer zekerheid te krijgen over de diagnose.

De belangrijkste voordelen van een biopt voor de patiënt zijn 1) zekerheid over de diagnose; 2) meer duidelijkheid omtrent de prognose; 3) ten behoeve van de verdere behandeling, onder andere biopt wenselijk respectievelijk vereist bij systeemtherapie en transplantatie bij non-cirrose. De belangrijkste nadelen van een biopt voor de patiënt zijn 1) het betreft een belastende interventie (punctie met dagopname); 2) er is een risico op complicaties 3) er is een risico dat de biopsie geen diagnose oplevert. Het kan ook blijken dat de punctie niet mogelijk is.

De waarden en voorkeuren van de patiënt dienen te worden besproken. Het is een individuele afweging of de patiënt de nadelen van het biopt tegen de voordelen vindt opwegen. Indien een biopt geen verdere consequenties heeft voor de behandeling kan hiervan in overleg met de patiënt worden afgezien.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De indicatie voor een tumorbiopt bij patiënten met niet-cirrotische levers blijft staan en conform eerdere richtlijnen is alléén beeldvorming niet voldoende. Deze overweging kan per patiënt in het multidisciplinair overleg (MDO) worden besproken en gewogen.

Het verrichten van een biopt bij een verdenking op een HCC in een niet-cirrotische lever is aanvaardbaar en conform de huidige klinische praktijk.

Het verdient de voorkeur om de diagnostiek bij een verdenking op een HCC in een niet-cirrotische lever in samenspraak met gespecialiseerde centra te verrichten. Dit is van belang gezien de relatief lage incidentie van levertumoren, kennis en ervaring met eventuele onderliggende leverziekten, de benodigde ervaring in de beoordeling van beeldvorming, en ook in het licht van histopathologisch onderzoek met mogelijk gespecialiseerd aanvullend moleculair onderzoek en immuunhistochemische kleuringen.

Bij de diagnose van een HCC dient het maken van een behandelplan te gebeuren in het MDO van een tertiair verwijscentrum in HCC, om de kwaliteit en uniformiteit in de diagnose en behandeling te waarborgen.

Rationale van de aanbeveling

Er is onvoldoende zekerheid dat alléén beeldvorming voldoende is voor een accurate diagnostiek van een HCC bij patiënten zonder levercirrose. Voor het vaststellen van een hepatocellulair carcinoom in een niet-cirrotische lever wordt een biopsie aanbevolen. Door de lage incidentie van HCC bij patiënten zonder levercirrose, kennis en ervaring met eventueel onderliggende leverziekten, de benodigde ervaring met het beoordelen van beeldvorming en de mogelijkheid voor gespecialiseerde pathologische onderzoeken heeft het de voorkeur om de diagnostiek bij verdenking op HCC van patiënten zonder levercirrose in samenspraak met gespecialiseerde centra te verrichten.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Niet-invasieve diagnostiek middels beeldvorming (CT/MRI) van hepatocellulair carcinoom (HCC) bij een niet-cirrotische lever is veel minder specifiek dan bij een cirrotische lever. Om deze reden wordt tot dusver een tumor biopt van de laesie geadviseerd bij verdenking HCC in patiënt met een niet-cirrotische lever. In de beeldvorming zijn continu ontwikkelingen gaande qua techniek, software, resolutie en andere mogelijkheden om weefsel te karakteriseren. In deze zoekvraag wordt de accuratesse van beeldvorming vergeleken met histologie voor het stellen van de diagnose HCC bij patiënten zonder levercirrose.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Computed tomography scan

|

Moderate GRADE |

There is a moderate certainty in the reported sensitivity of computed tomography in patients with a hepatocellular carcinoma measuring over 2 centimeters and with or without other liver disease, excluding liver cirrhosis.

The certainty in the reported sensitivity may be very low for patients with a hepatocellular carcinoma measuring 1-2 centimeters and with or without other liver disease, excluding liver cirrhosis.

Sources: (Kim, 2011; Lin, 2016) |

|

Very low GRADE |

There is a very low certainty in the reported specificity of computed tomography in patients with a hepatocellular carcinoma with or without other liver disease, excluding liver cirrhosis.

Sources: (Kim, 2011; Lin, 2016) |

|

Low GRADE |

There is a low certainty in the reported positive predictive value of computed tomography in patients with a hepatocellular carcinoma measuring over 2 centimeters and with or without other liver disease, excluding liver cirrhosis. The certainty may be very low for patients with a hepatocellular carcinoma measuring 1-2 centimeters and with or without other liver disease, excluding liver cirrhosis.

Sources: (Kim, 2011; Lin, 2016) |

|

Very low GRADE |

There is a very low certainty in the reported negative predictive value of computed tomography in patients with a hepatocellular carcinoma with or without other liver disease, excluding liver cirrhosis.

Sources: (Kim, 2011; Lin, 2016) |

Magnetic Resonance imaging

|

Very low GRADE |

There is a very low certainty in the reported sensitivity of magnetic resonance imaging in patients with a hepatocellular carcinoma with or without other liver disease, excluding liver cirrhosis.

Sources: (Fischer, 2015; Lin, 2016) |

|

Very low GRADE |

There is a very low certainty in the reported specificity of magnetic resonance imaging in patients with a hepatocellular carcinoma with or without other liver disease, excluding liver cirrhosis.

Sources: (Fischer, 2015; Lin, 2016) |

|

Very low GRADE |

There is a very low certainty in the reported positive predictive value of magnetic resonance imaging in patients with a hepatocellular carcinoma with or without other liver disease, excluding liver cirrhosis.

Sources: (Fischer, 2015; Lin, 2016) |

|

Very low GRADE |

There is a very low certainty in the reported negative predictive value of magnetic resonance imaging in patients with a hepatocellular carcinoma with or without other liver disease, excluding liver cirrhosis.

Sources: (Fischer, 2015; Lin, 2016) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Fischer (2015) recruited 107 consecutive patients from five centers suspected of a hepatocellular carcinoma without liver cirrhosis. Patients were included when they had an MRI prior to surgery for a suspicious HCC lesion, had histopathological evidence of HCC, had histopathological evidence of a non-cirrhotic liver, and when time between MRI and surgery was less than 2 months. Exclusion criteria did not seem to be described. Prevalence of HCC was 51.4%. The cohortconsisted of 46 males and 61 females. HBV status for patients with benign lesions was negative (n=43), positive (n=1), or unknown (n=8), while for HCC lesions this was n=40, n=11, and n=4 in the respective categories. In patients with benign lesions the HCV status was negative (n=44), positive (n=0), or unknown (n=8), and in patients with HCC lesions this was n=47 (negative), n=4 (positive), and n=4 (unclear). Median AFP in the patients with benign lesions was 2.3 (IQR: 1.5 to 4.0) and 3.5 (IQR 2.7 to 7.4) for patients with HCC. The five centers used different MR sequences in the axial and/or coronal plane (i.e. T1 Dyn lava, T1 flash FS, T1 flash in/opp, T1 in/opp, T1 vibe 3D dynamic ,T2 blade (TSE), T2 FRFSE, T2 FS RT, T2 SSFSE, T2 SSFSH, T2 trufi, T2 TSE, T2Haste, T2Haste fat sat). Time of repetition (range: 3.3 to 9474), time of echo (range: 1.3 to 105), flip angle (range: 15 to 180), and slice thickness (range: 3 to 10) parameters were reported. LI-RADS were used for diagnosis. Three imaging protocols were used: single contrast with an extracellular agent (n=53), single contrast with a hepatobiliary-specific agent (n=42), and a double contrast protocol with ECF and reticuloendothelial-specific agents (n=12). The surgical specimen underwent standard histopathological examination.

Kim (2011) prospectively enrolled patients between December 2006 and June 2009 with hepatic masses larger than 2 centimeters who were admitted at the hepatology department of a single center (Asan Medical Center, Korea). Other inclusion criteria did not seem to be described. Patients with hepatic nodules between 1 and 2 centimeters were excluded (n=68), had received a CT as staging work-up for a known primary extrahepatic malignancy, were in the terminal stage of the disease, had severe coagulopathy and/or had intraperitoneal bleeding from spontaneously ruptured tumors. The reference standard was fine needle biopsy under ultrasound guidance and diagnosis was set according to the International Working Party criteria. At least two liver tissue cores were obtained from each patient and stained with hematoxylin-eosin. A second fine needle biopsy was performed when the first was inconclusive. Patients with inconclusive results from the fine needle biopsies were excluded from analyses. Eleven patients refused a second fine needle biopsy and were excluded from the analyses. Patients with AFP>200ng/ml or typical enhancement pattern and with risk factors for HCC were candidates for surgical resection and did not undergo fine needle biopsies (n=24). Patients underwent a helical CT-scan with 4 phases (non-contrast, arterial, portal, delayed) with both a slice thickness and table feed of 5 millimeters. Iopromide was used as a nonionic contrast agent (120ml, 3.5ml/sec via power injector). Scanning delay was determined using SmartPrep. Arterial phase, portal phase, and delayed phase respectively began at 24, 72-90, and 180 seconds after the aortic enhancement reached 100HU above the pre-contrast attenuation. CT findings were read by two radiologists having 10 and 20 years experience in liver imaging, respectively. Hypervascular enhancement (arterial phase) and washout (portal/delayed phase) were classified as typically vascular. Tumors with mixed areas of hypervascularity (area >70%) and hypovascularity were considered a typical enhancement pattern. Other patterns were considered atypical. The sample was divided into three groups: patients with cirrhosis (n=107), high risk patients without cirrhosis (positive for hepatitis B surface antigen and/or anti-HCV, n=62), and low risk patients without cirrhosis (negative for hepatitis B surface antigen and/or anti-HCV, n=37). The high risk patients (n=52 males, n= 10 females) had a median age of 52 years (range: 30 to 71). Hepatitis status in the high risk group was positive for hepatitis B (n=56), positive for hepatitis C (n=5, or positive for both hepatitis B and C (n=1). Low risk patients (n=21 males, n=16 females) had a median age of 52 years (range: 23 to 81) and all had no or cryptogenic underlying liver disease.

Lin (2016) conducted a retrospective study in Taiwan. Patients that had undergone a tumor resection or liver transplantation between January 2006 and October 2010 in the Chang Gang Memorial Hospital were selected. Other inclusion criteria did not seem to be described. Patients without a liver CT or MRI before surgery, without available pathological fibrosis score, or without a tumor in the explanted liver were excluded. Selected patients (n=841) underwent CT (n=756) and/or MRI (n=204). HCC imaging characteristics were defined as early enhancement in the arterial phase and early washout in the venous phase. The reference tests were histological and surgical reports. Patients who underwent CT (n =555 males, n =201 females) had a mean age of 55.81 years (SD: 12.27) and the mean tumor size was 5.44cm (SD: 4.12; 1-2cm: n=131, >2cm: n=625). Pathological METAVIR fibrosis score was F0 (n=104), F1 (n=88), F2 (n=40), F3 (n=77), or F4 (n=281, chirrosis). Hepatitis-status in the CT-group was: non hepatitis B or C (n=202), hepatitis B (n=374), hepatitis C (n=157), or hepatitis B and C (n=22). A helical CT with 4 phases was performed (non-contrast, arterial, portal, and delayed) and the scan was acquired in a clockwise direction in 5mm sections. Contrast medium (2ml/sec, 80ml total) was used, although it did not seem to be reported which contrast medium was used. The scan for the arterial phase started 30 seconds after injection with the contrast medium. The scan for the portal phase started 20 seconds after the arterial phase, and the scan for the venous phase started 20 seconds after the portal phase. Patients who received an MRI (n=142 males, n=62 females) had a mean age of 54 years (SD: 12.49) and a mean tumor size of 4.04cm (SD: 3.13; 1-2cm: n=58, >2cm: n=146). The pathological METAVIR fibrosis score for patients who received an MRI was F0 (n=21), F1 (n=18), F2 (n=2), F3 (n=14), or F4 (n=90, cirrhosis). MR imaging was acquired using 1.5-2T MRI including contrast medium (Gd-DTPA, 0.2mg/kg, 1.6-1.8ml/sec) using T1WI, T2WI, T2WI Fsat, heavy T2WI, long T2WI, and/or enhanced T1WI pulse sequences (8mm thickness, 2mm gap) in three phases. The first phase was obtained 15 seconds after the contrast infusion, while the second and third phase were obtained after 30 second intervals.

Results

Computed Tomography Scan

Sensitivity

Kim (2011) reported the sensitivity of CT for HCCs in hepatic nodules >2cm in patients without cirrhosis and divided this group in high risk and low risk groups for HCC. The sensitivity of CT in the high-risk group was 81.6% (95%CI: 0.67 to 0.91, n=49), while the sensitivity in the low-risk group was 87.5% (95%CI: 0.60 to 0.98, n=16).

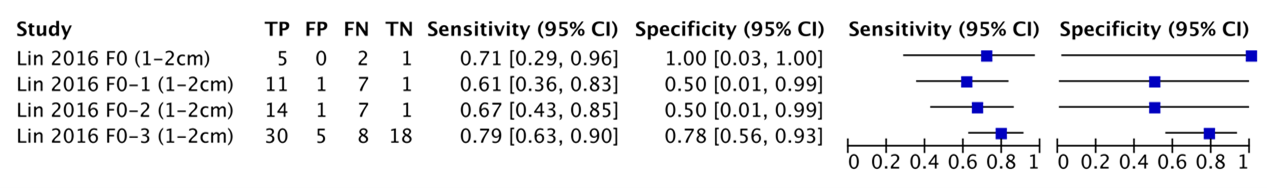

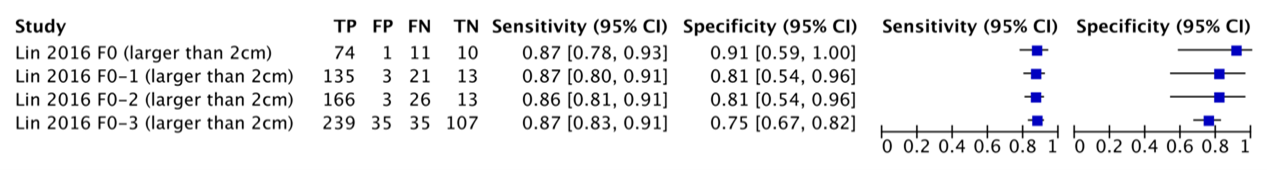

Lin (2016) reported the sensitivity of CT for HCCs in a non-cirrhotic sample. The sensitivity was calculated depending on the increasing METAVIR fibrosis scores and the size of the HCC. Figures 9.1 and 9.2 summarize the sensitivities for detecting HCCs (1-2cm and >2cm respectively) with CT.

Specificity

Kim (2011) reported the specificity of CT for HCCs in hepatic nodules >2cm in a group of high-risk patients without cirrhosis and in a group with low-risk patients without cirrhosis. The specificity of CT in the high-risk group was 92.3% (95%CI: 0.62 to 0.99, n=13), while the specificity in the low-risk group was 90.5% (95%CI: 0.68 to 0.98, n=21).

Lin (2016) reported the specificity of CT for HCCs in a non-cirrhotic sample. The specificity was calculated depending on the increasing METAVIR fibrosis scores and the size of the HCC. Figures 1 and 2 summarize the specificities for detecting HCCs (1-2cm and >2cm respectively) with CT.

Figure 9.1 – Sensitivity and specificity of CT detecting 1-2cm HCCs depending on the METAVIR fibrosis scores in the sample, from Lin (2016). A score from F0 to F3 means cirrhosis is absent but fibrosis is increasingly present. (TP: True Positive, FP: False Positive, FN: False negative, TN: True Negative, CI: Confidence interval)

Figure 9.2 – Sensitivity and specificity of CT detecting HCCs >2cm depending on the METAVIR fibrosis scores in the sample, from Lin (2016). A score from F0 to F3 means cirrhosis is absent but fibrosis is increasingly present. (TP: True Positive, FP: False Positive, FN: False negative, TN: True Negative, CI: Confidence interval)

Positive predictive value

Kim (2011) reported the positive predictive value of CT in both the high-risk group without chirrosis (PPV: 97.6%, 95%CI: 0.86 to 0.99) and the low-risk group without cirrhosis (PPV: 87.5%, 95%CI: 0.60 to 0.98).

Lin (2016) calculated the positive predictive values of CT detecting both 1-2cm and >2cm HCCs, respectively. Results are summarized in Table 9.3.

Negative predictive value

Kim (2011) reported the negative predictive value of CT in both in the high-risk group without cirrhosis and in the low-risk group without cirrhosis. CT in the high-risk group had a negative predictive value of 57.1% (95%CI: 0.34 to 0.77), while this was 90.4% (95%CI: 0.68 to 0.98) in the low-risk group.

Lin (2016) calculated the negative predictive values of CT detecting both 1-2cm and >2cm HCCs, respectively. Results are summarized in Table 9.3.

Table 9.3 – Positive and negative predictive values of CT on the size of the HCC and METAVIR-score in the sample, from Lin (2016). Confidence intervals were calculated in RevMan 5. A score from F0 to F3 means cirrhosis is absent but fibrosis is increasingly present.

|

|

CT |

|

|

PPV (95%CI) |

NPV (95%CI) |

|

|

1-2cm HCC |

|

|

|

METAVIR F0 |

100% (0.48-1.00)‡ |

33.3% (0.01-0.91)‡ |

|

METAVIR F0-1 |

91.7% (0.62-1.00)† |

12.5% (0.00-0.53)‡ |

|

METAVIR F0-2 |

87.5% (0.62-0.98)† |

12.5% (0.00-0.53)‡ |

|

METAVIR F0-3 |

85.7% (0.70-0.95)† |

69.2% (0.48-0.86)† |

|

|

|

|

|

>2cm HCC |

|

|

|

METAVIR F0 |

98.7% (0.93-1.00)* |

38.2% (0.26-0.70)† |

|

METAVIR F0-1 |

97.8% (0.95-1.00) |

38.2% (0.22-0.56)† |

|

METAVIR F0-2 |

98.2% (0.95-1.00) |

33.3% (0.19-0.50)† |

|

METAVIR F0-3 |

89.5% (0.85-0.93) |

75.4% (0.67-0.82) |

|

* Calculation in a (sub)sample with between 50-100 patients † Calculation in a (sub)sample with between 10-50 patients ‡ Calculation in a (sub)sample with less than 10 patients CI: Confidence Interval Cm: centimeters CT: Computed Tomography HCC: Hepatocellular Carcinoma NPV: Negative Predictive Value PPV: Positive Predictive Value |

||

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Sensitivity

Fischer (2015) identified four MR features associated with HCC in patients with non-cirrhotic livers and reported their sensitivity:

- T1-intensity (hypointense): 0.78 (95%CI: 0.65-0.88).

- T2-intensity (not isointense): 0.85 (95%CI: 0.73-0.94).

- Central enhancement (no): 0.69 (95%CI: 0.55-0.81).

- Satellite lesions (yes): 0.24 (95%CI: 0.13-0.37).

The 95%CI’s were recalculated in RevMan 5. When combined, any two positive features of the four resulted in a sensitivity of 0.91 (95%CI not reported and could not be calculated).

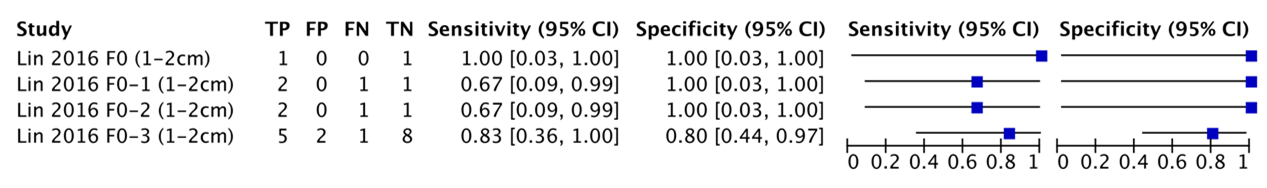

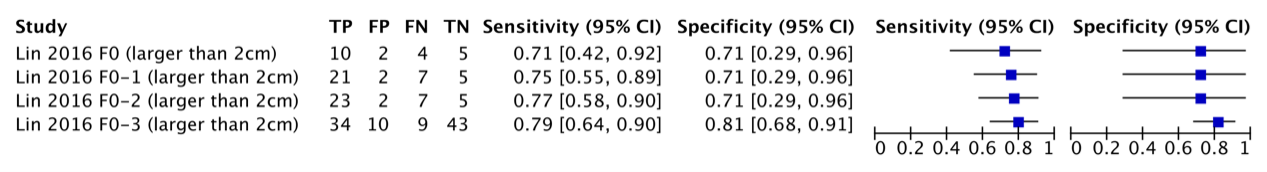

Lin (2016) reported the sensitivity of MRI for HCCs in patients with a non-cirrhotic liver. The specificity was calculated depending on the increasing METAVIR fibrosis scores and the size of the HCC. Figures 3 and 4 summarize the sensitivities for detecting HCCs (1-2cm and >2cm, respectively) with MRI.

Specificity

The specificity of the four MR features identified by Fischer (2015) having an association with HCC in patients with non-cirrhotic livers was reported:

- T1-intensity (hypointense): 0.63 (95%CI: 0.49-0.76).

- T2-intensity (not isointense): 0.50 (95%CI: 0.36-0.64).

- Central enhancement (no): 0.73 (95%CI: 0.59-0.84).

- Satellite lesions (yes): 0.96 (95%CI: 0.87-1.00).

The 95%CIs were recalculated in RevMan 5. When combined, any two positive features of the four resulted in a specificity of 0.75. When all four features were positive, specificity reached 0.98. The confidence intervals were not reported.

Lin (2016) reported the specificity of MRI for detecting HCCs in patients without liver cirrhosis. The specificity was calculated depending on the increasing METAVIR fibrosis scores and the size of the HCC. See Figures 9.4 and 9.5 for a summary of the specificities for MRI detecting HCCs (1-2cm and >2cm, respectively).

Figure 9.4 – Sensitivity and specificity of MRI detecting 1-2cm HCCs depending on the METAVIR fibrosis scores in the sample, from Lin (2016). A score from F0 to F3 means cirrhosis is absent but fibrosis is increasingly present. (TP: True Positive, FP: False Positive, FN: False negative, TN: True Negative, CI: Confidence interval)

Figure 9.5 – Sensitivity and specificity of MRI detecting HCCs >2cm depending on the METAVIR fibrosis scores in the sample, from Lin (2016). A score from F0 to F3 means cirrhosis is absent but fibrosis is increasingly present. (TP: True Positive, FP: False Positive, FN: False negative, TN: True Negative, CI: Confidence interval)

Positive predictive value

Fischer (2015) reported the positive predictive values of four MR imaging features:

- T1-intensity (hypointense): 0.69 (95%CI: 0.57-0.81).

- T2-intensity (not isointense): 0.64 (95%CI: 0.52-0.76).

- Central enhancement (no): 0.73 (95%CI: 0.60-0.86).

- Satellite lesions (yes): 0.87 (95%CI: 0.66-1.00).

Lin (2016) calculated the positive predictive values of MRI detecting both 1-2cm and >2cm HCCs, respectively. Results are summarized in Table 2.

Negative predictive value

Fischer (2015) reported the negative predictive values of four MR imaging features:

- T1-intensity (hypointense): 0.73 (95%CI: 0.59-0.87).

- T2-intensity (not isointense): 0.76 (95%CI: 0.60-0.92).

- Central enhancement (no): 0.69 (95%CI: 0.55-0.82).

- Satellite lesions (yes): 0.54 (95%CI: 0.43-0.65).

Lin (2016) calculated the negative predictive values of MRI detecting both 1-2cm and >2cm HCCs, respectively. Results are summarized in Table 9.6.

Table 9.6 – Positive and negative predictive values of MRI depending on the size of the HCC and METAVIR-score in the sample, from Lin (2016). Confidence intervals were calculated in RevMan 5. A score from F0 to F3 means cirrhosis is absent but fibrosis is increasingly present.

|

|

MRI |

|

|

PPV (95%CI) |

NPV (95%CI) |

|

|

1-2cm HCC |

|

|

|

METAVIR F0 |

100% (0.03-1.00)‡ |

100% (0.03-1.00)‡ |

|

METAVIR F0-1 |

100% (0.16-1.00)‡ |

50% (0.01-0.99)‡ |

|

METAVIR F0-2 |

100% (0.16-1.00)‡ |

50% (0.01-0.99)‡ |

|

METAVIR F0-3 |

71.4% (0.29-0.96)‡ |

88.9% (0.52-1.00)‡ |

|

|

|

|

|

>2cm HCC |

|

|

|

METAVIR F0 |

90.9% (0.62-0.89)† |

50% (0.16-0.84)‡ |

|

METAVIR F0-1 |

91.3% (0.72-0.99)† |

41.7% (0.15-0.72)† |

|

METAVIR F0-2 |

92% (0.74-0.99)† |

41.7% (0.15-0.72)† |

|

METAVIR F0-3 |

77.3% (0.62-0.89)† |

82.7% (0.70-0.92)* |

|

* Calculation in a (sub)sample with between 50-100 patients † Calculation in a (sub)sample with between 10-50 patients ‡ Calculation in a (sub)sample with less than 10 patients CI: Confidence Interval Cm: centimeters HCC: Hepatocellular Carcinoma MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging NPV: Negative Predictive Value PPV: Positive Predictive Value |

||

Level of evidence of the literature

Computed Tomography scan

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure sensitivity was downgraded by 1 level because of study limitations (1 level for risk of bias: Nadarevic (2021, 2022) judged both studies to have high risk of bias on patient selection, flow and timing, and one study also on the reference standard); number of included patients (0 to -2 levels for imprecision: wide to very wide confidence intervals depending on the subgrouping in analysis; 1-2cm HCC’s are more imprecise and may warrant a -2 for imprecision); publication bias was not assessed.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure specificity was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations (1 level for risk of bias: Nadarevic (2021, 2022) judged both studies to have high risk of bias on patient selection, flow and timing, and one study also on the reference standard); number of included patients (2 levels for imprecision: very wide confidence intervals); publication bias was not assessed.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure positive predictive value was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (1 level for risk of bias: Nadarevic (2021, 2022) judged both studies to have high risk of bias on patient selection, flow and timing, and one study also on the reference standard); number of included patients (1 level for imprecision: wide to very wide confidence intervals depending on the subgrouping in analysis; 1-2cm HCC’s are more imprecise and may warrant a -2 for imprecision); publication bias was not assessed.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure negative predictive value was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations (1 level for risk of bias: Nadarevic (2021, 2022) judged both studies to have high risk of bias on patient selection, flow and timing, and one study also on the reference standard); number of included patients (2 levels for imprecision: very wide confidence intervals); publication bias was not assessed.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure sensitivity was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations (1 level for risk of bias: one of the two studies (carrying about 50% of the sample size in the body of evidence) was judged to have a high risk of bias for patient selection and flow and timing by Nadarevic (2022)); number of included patients (2 levels for imprecision: very wide confidence intervals); publication bias was not assessed.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure specificity was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations (1 level for risk of bias: one of the two studies (carrying about 50% of the sample size in the body of evidence) was judged to have a high risk of bias for patient selection and flow and timing by Nadarevic (2022)); number of included patients (2 levels for imprecision: very wide confidence intervals); publication bias was not assessed.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure positive predictive value was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations (1 level for risk of bias: one of the two studies (carrying about 50% of the sample size in the body of evidence) was judged to have a high risk of bias for patient selection and flow and timing by Nadarevic (2022)); number of included patients (2 levels for imprecision: very wide confidence intervals); publication bias was not assessed.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure negative predictive value was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations (1 level for risk of bias: one of the two studies (carrying about 50% of the sample size in the body of evidence) was judged to have a high risk of bias for patient selection and flow and timing by Nadarevic (2022)); number of included patients (2 levels for imprecision: very wide confidence intervals); publication bias was not assessed.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the diagnostic accuracy of MRI or a multiphasic CT-scan in patients suspected of a hepatocellular carcinoma with or without liver disease, but excluding liver cirrhosis, compared to histology as a reference standard?

P: Patients suspected of a hepatocellular carcinoma without other liver disease and/or with liver disease excluding cirrhosis;

I: MRI or multiphasic CT-scan;

C: -;

R: Histology;

O: Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered unequivocal diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), sensitivity, and negative predictive value as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and suspicion for HCC as an important outcome measure for decision making.

The working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 21-07-2022 for systematic reviews. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 33 unique hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: patients were suspected of a hepatocellular carcinoma, patients either did not have other liver disease or had liver disease excluding cirrhosis, MRI or a multiphasic CT-scan was used as an index test, histology was used as a reference standard, at least one of the outcomes of interest was reported or could be calculated from the presented data, and the article was a systematic review. Ten systematic revies were selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, all systematic reviews were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods).

Since no relevant aggregated evidence seemed to be available, we used the title and abstract selection of two recent Cochrane reviews about detecting HCCs with CT and MRI (Nadarevic, 2021; Nadarevic, 2022), which both were identified in our search strategy. We downloaded the study data from the included studies in the Cochrane reviews through the Cochrane Library and identified and read those studies with a prevalence of cirrhosis either not reported or being <100% in full text for our study selection (n=12 studies). These studies could potentially report (sub-)analyses for patients with non-cirrhotic livers. Thus, twelve primary studies originally included in the Cochrane reviews were read full-text of which we excluded ten studies (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods). We furthermore screened 214 excluded articles (after removing duplicates) by Nadarevic (2021, 2022) on the title and abstract for potentially relevant studies for the current guideline module. Eighteen primary studies were selected based on title and abstract screening, from which seventeen studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods). This method resulted in the selection of three primary studies.

Results

Three primary studies were included in the analysis of the literature (Fischer, 2015; Kim, 2011; Lin, 2016). Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Fischer MA, Raptis DA, Donati OF, Hunziker R, Schade E, Sotiropoulos GC, McCall J, Bartlett A, Bachellier P, Frilling A, Breitenstein S, Clavien PA, Alkadhi H, Patak MA. MR imaging features for improved diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in the non-cirrhotic liver: Multi-center evaluation. Eur J Radiol. 2015 Oct;84(10):1879-87. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.06.029. Epub 2015 Jul 2. PMID: 26194029.

- Kim SE, Lee HC, Shim JH, Park HJ, Kim KM, Kim PN, Shin YM, Yu ES, Chung YH, Suh DJ. Noninvasive diagnostic criteria for hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatic masses >2 cm in a hepatitis B virus-endemic area. Liver Int. 2011 Nov;31(10):1468-76. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02529.x. Epub 2011 Apr 11. PMID: 21745284.

- Lin MT, Wang CC, Cheng YF, Eng HL, Yen YH, Tsai MC, Tseng PL, Chang KC, Wu CK, Hu TH. Comprehensive Comparison of Multiple-Detector Computed Tomography and Dynamic Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Diagnosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Varying Degrees of Fibrosis. PLoS One. 2016 Nov 9;11(11):e0166157. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166157. PMID: 27829060; PMCID: PMC5102357.

- Nadarevic T, Colli A, Giljaca V, Fraquelli M, Casazza G, Manzotti C, timac D, Miletic D. Magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in adults with chronic liver disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 May 6;5(5):CD014798. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD014798.pub2. PMID: 35521901; PMCID: PMC9074390.

- Nadarevic T, Giljaca V, Colli A, Fraquelli M, Casazza G, Miletic D, timac D. Computed tomography for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in adults with chronic liver disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Oct 6;10(10):CD013362. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013362.pub2. PMID: 34611889; PMCID: PMC8493329.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Index test (test of interest) |

Reference test

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Kim 2011 |

Type of study[1]: Prospective cohort

Setting and country: Hospital, Korea

Funding and conflicts of interest: authors declare no competing interests, funding by a grant from Korea healthcare Technology R&D project (Grant #A084826, Ministry of health welfare and family affairs) |

Inclusion criteria: Patients with hepatic masses >2cm, admitted to the hepatology department of Asan Medical Center (Korea) between December 2006 and June 2009.

Exclusion criteria: Received CT as staging work-up for a known primary extrahepatic malignancy, terminal stage of the disease, severe coagulopathy, intraperitoneal bleeding from spontaneously ruptured tumors.

N= 62 (group 2) N= 37 (group 3)

Prevalence: Group 2: 49/62=79% Group 3: 16/37=43.2%

Mean age ± SD: Group 2: 52 (30-71) Group 3: 55 (21-81)

Sex: % M / % F Group 2: 84%/16% Group 3: 57%/43%

Other important characteristics:

Hepatitis B: Group 2: 56 Group 3: -

Hepatitis C: Group 2: 5 Group 3: -

Hepatitis B and C: Group 2: 1 Group 3: -

|

Describe index test: Helical CT with 4 phases (precontrast, arterial, portal, delayed). Slice thickness was 5mm and table feed was 5mm. Iopromide was used as a nonionic contrast agent (120ml, 3.5ml/sec via power injector). Scanning delay was determined using SmartPrep. Arterial phase, portal phase and delayed phase scanning began at 24, 72-90 and 180sec after descending aortic enhancement reached a threshold of 100HU above precontrast attenuation.

CT findings were read by two radiologists (10 and 20 years experience in liver imaging)

Cut-off point(s): Hypervascular enhancement pattern in the arterial phase and washout in the portal/delayed phase were classified as typically vascular. Tumors showing mixed areas of hyper and hypovascularity (with >70% hypervascular area) were considered a typical enhancement pattern. Other patterns were considered atypical.

Comparator test[2]: - Cut-off point(s): - |

Describe reference test[3]: Fine Needle Biopsy under ultrasound guidance. At least two cores of liver tissue were obtained from each patient and stained with haematoxylin-eosin.

If a conclusive result was not obtained, a second FNB was recommended.

Cut-off point(s): International Working Party criteria. |

Time between the index test en reference test: Unclear

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? 11 patients refused a second FNB and were excluded from analysis

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? Refusal of second FNB |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available)4:

Group 2 CT detecting HCC >2cm: Sens: 81.6% (95%CI: 0.67-0.91) Spec: 92.3% (95%CI: 0.62-0.99) PPV: 97.6% (95%CI: 0.86-0.99) NPV: 57.1% (95%CI: 0.34-0.77)

Group 3 CT detecting HCC >2cm: Sens: 87.5% (95%CI: 0.60-0.98) Spec: 90.5% (95%CI: 0.68-0.98) PPV: 87.5% (95%CI: 0.60-0.98) NPV: 90.4% (95%CI: 0.68-0.98) |

Patients with AFP>200ng/ml or typical enhancement patten on dynamic CT and with risk factors for HCC and were candidates for surgical resection did not undergo fine needle biopsy.

Patients with inconclusive FNB results were excluded from analysis.

Group 2 = high risk patient without cirrhosis (non-cirrhotic patient positive for hepatitis B surface antigen or anti-HCV)

Group 3 = low risk patient without cirrhosis (non-cirrhotic patient negative for hepatitis B surface antigen and anti-HCV) |

|

Lin 2016 |

Type of study: Retrospective

Setting and country: Hospital, Taiwan

Funding and conflicts of interest: no specific funding received, authors declared that there were no conflicts of interest |

Inclusion criteria: Patients that underwent tumor resection or liver transplantation in Chang Gang Memorial Hospital between January 2006 and October 2010

Exclusion criteria: No liver CT or MRI before surgery, no pathological fibrosis score available, no tumor in the explanted liver.

N=841 total

Prevalence: CT: 100%

Mean age ± SD: CT: 55.81 (12.27) MRI: 54 (12.49)

Sex: M / F CT: 555/201 MRI: 142/62

Other important characteristics:

Mean tumor size (cm): CT: 5.44 (SD 4.12) MRI: 4.04 (SD 3.13)

Fibrosis level CT: F0: n=104 F1: n=88 F2: n=40 F3: n=77 F4= 281

Fibrosis level MRI: F0: n=21 F1: n=18 F2: n=2 F3: n=14 F4=90

Non hepatitis B or C: CT: 202 MRI: 65

Hepatitis B: CT: 374 MRI: 96

Hepatitis C: CT: 157 MRI: 36

Hepatitis B and C: CT: 22 MRI 6 |

Describe index test: CT: helical CT with 4-phases (non-contrast, arterial, portal, delayed) aquired in a clockwise direction in 5mm sections. Contrast medium was used (2ml/sec, 80ml total). Thirty second after injection the scan for the arterial phase started. Portal phase scan started 20 sec after the arterial phase and the venous phase started 20 sec after the portal phase.

MRI: 1.5-2T MRI including contrast medium (intravenous Gd-DTPA, 0.2mg/kg ar 1.6-1.8 ml/sec). pulse sequences were T1WI / T2WI / T2WI Fsat / heavy T2WI, long T2WI, enhancedT1WI in three phases. First phase was obtained 15 sec after contrast infusion, and the second and third phase after 30 sec intervals. Eight mm thickes and 2mm gap were used for the sequences.

Cut-off point(s): Early enhancement in arterial phase AND early washout in venous phase

Comparator test: -

Cut-off point(s): -

|

Describe reference test: Histological and surgical reports

Cut-off point(s): -

|

Time between the index test en reference test: Not specified

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available?

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? - |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

CT detecting 1-2cm tumours in F0 group: Sens: 5/7 (71.4%) Spec: 1/1 (100%) PPV: 5/5 (100%) NPV: 1/3 (33.3%)

CT detecting 1-2 tumours in F0-1 group: Sens: 11/18 (61.1%) Spec: 1/2 (50%) PPV: 11/12 (91.7%) NPV: 1/8 (12.5%)

CT detecting 1-2cm tumours in F0-2 group: Sens: 14/21 (66.7%) Spec: 1/3 (33.3%) PPV: 14/16 (87.5%) NPV: 1/8 (12.5%)

CT detecting 1-2cm tumours in F0-3 (non-cirrhotic) group: Sens: 30/38 (78.9%) Spec: 18/23 (78.3%) PPV: 30/35 (85.7%) NPV: 18/26 (69.2%)

CT detecting >2cm tumours in F0 group: Sens: 74/85 (87.1%) Spec: 10/11 (90.9%) PPV: 74/75 (98.7%) NPV: 13/34 (38.2%)

CT detecting >2 tumours in F0-1 group: Sens: 135/156 (86.5%) Spec: 13/16 (81.3%) PPV: 135/138 (97.8%) NPV: 13/34 (38.2%)

CT detecting >2cm tumours in F0-2 group: Sens: 166/192 (86.5%) Spec: 13/16 (81.3%) PPV: 166/169 (98.2%) NPV: 13/39 (33.3%)

CT detecting >2cm tumours in F0-3 (non-cirrhotic) group: Sens: 239/274 (87.2%) Spec: 107/135 (79.3%) PPV: 239/267 (89.5%) NPV: 107/142 (75.4%)

MRI detecting 1-2cm tumours in F0 group: Sens: 1/1 (100%) Spec: 1/1 (100%) PPV: 1/1 (100%) NPV: 1/1 (100%)

MRI detecting 1-2 tumours in F0-1 group: Sens: 2/3 (66.7%) Spec: 1/1 (100%) PPV: 2/2 (100%) NPV: 1/2 (50%)

MRI detecting 1-2cm tumours in F0-2 group: Sens: 2/3 (66.7%) Spec: 1/1 (100%) PPV: 2/2 (100%) NPV: 1/2 (50%)

MRI detecting 1-2cm tumours in F0-3 (non-cirrhotic) group: Sens: 5/6 (83.3%) Spec: 8/10 (80%) PPV: 5/7 (71.4%) NPV: 8/9 (88.9%)

MRI detecting >2cm tumours in F0 group: Sens: 10/14 (71.4%) Spec: 4/5 (80%) PPV: 10/11 (90.9%) NPV: 4/8 (50%)

MRI detecting >2 tumours in F0-1 group: Sens: 21/28 (75%) Spec: 5/7 (71.4%) PPV: 21/23 (91.3%) NPV: 5/12 (41.7%)

MRI detecting >2cm tumours in F0-2 group: Sens: 23/30 (76.7%) Spec: 5/7 (71.4%) PPV: 23/25 (92%) NPV: 5/12 (41.7%)

MRI detecting >2cm tumours in F0-3 (non-cirrhotic) group: Sens: 34/43 (79.1%) Spec: 43/53 (81.1%) PPV: 34/44 (77.3%) NPV: 43/53 (82.7%) |

Two subsamples: resection and liver transplantation. Patients without a tumor in the explanted liver were excluded.

N=841 patients recruited, n=756 CT and n=204 MRI. Thus some patients received both a CT and MRI, while others received a single CT or MRI.

n=756 CT of which n= 131 had a tumor 1-2cm and n=625 had >2cm. 131+625=756, thus seems like 100% prevalence of HCC from table 1. |

|

Fischer 2015 |

Type of study: Retrospective from trial (consecutive recruitment)

Setting and country: Multicenter, hospital

Funding and conflicts of interest: Authors declare that there are no CoIs |

Inclusion criteria: MRI prior to surgery for a suspicious HHC lesion, histopathologic evidence forr HCC, histopathologic evidence of a non-cirrhotic liver, and time between MRI and surgery <2 months

Exclusion criteria: not reported

N=107

Prevalence: 51.4%

Median age ± (IQR): Benign: 34 (28-45) HCC: 61 (45-71)

Sex, n, M/F: Benign: 10/42 HCC: 36/19

HBV status, -/+/unknown: Benign: 43/1/8 HCC: 40/11/4

HCV status, -/+/unknown: Benign: 44/0/8 HCC: 47/4/4

Median AFP (IQR): Benign: 2.3 (1.5-4.0) HCC: 3.5 (2.7-7.4)

Other important characteristics:

|

Describe index test: Three protocols were used:

Five centres used different sequences in the coronal and/or axial plane:

Time of repetition ranged from 3.3 to 9474. Time of echo ranged from 1.3 to 105. Flip angle ranged from 15 to 180. Slice thickness ranged from 3 to 10mm.

Cut-off point(s): LI-RADS criteria at arterial, porto-venous, late, and hepatobiliary phase:

|

Describe reference test: Histopathological examination of surgical specimen by macroscopic analysis and tissue sampling (both tumoral and non-tumoral liver). Immunihistochemistry was performed for final diagnosis

Cut-off point(s): NR

|

Time between the index test and reference test: <2 months between imaging and surgery

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? All 107 patients were used in the analysis

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? NA |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Multiple regression identified 4 factors associated with HHC: T1-intensity (hypointense) (OR=4.81, 95%CI: 0.52-9.13) T2-intensity (not isointense) (OR= 5.07, 95%CI: 0.55-8.85) Central enhancement (no) (OR=3.31, 95%CI: 0.50-5.69) Satellite lesions (yes) (OR=5.78, 95%CI: 0.97-9.34)

T1-intensity (hypointense) Sens: 0.78 (95%CI: 0.65-0.88)* Spec: 0.63 (95%CI: 0.49-0.64)* NPV: 0.73 (95%CI: 0.59-0.87) PPV: 0.69 (95%CI: 0.57-0.81) *95%Cis calculated with Revman 5

T2-intensity (not isointense) Sens: 0.85 (95%CI: 0.73-0.94)* Spec: 0.50 (95%CI: 0.36-0.64)* NPV: 0.76 (95%CI: 0.60-0.92) PPV: 0.64 (95%CI: 0.52-0.76) *95%Cis calculated with Revman 5

Central enhancement (no) Sens: 0.69 (95%CI: 0.55-0.81)* Spec: 0.73 (95%CI: 0.59-0.84)* NPV: 0.69 (95%CI: 0.55-0.82) PPV: 0.73 (95%CI: 0.60-0.86) *95%Cis calculated with Revman 5

Satellite lesions (yes) Sens: 0.24 (95%CI: 0.13-0.37)* Spec: 0.96 (95%CI: 0.87-1.00)* NPV: 0.54 (95%CI: 0.43-0.65) PPV: 0.87 (95%CI: 0.66-1.00) *95%Cis calculated with Revman 5

When any 2 of the 4 imaging features were positive, the sensitivity was 0.91 and the specificity was 0.75 for contrast enhanced MR (AUC=0.85, 95%CI: 0.77-0.93)

All 4 features positive: specificity was 98% (sens not reported) |

|

[1] In geval van een case-control design moeten de patiëntkarakteristieken per groep (cases en controls) worden uitgewerkt. NB; case control studies zullen de accuratesse overschatten (Lijmer et al., 1999)

[2] Comparator test is vergelijkbaar met de C uit de PICO van een interventievraag. Er kunnen ook meerdere tests worden vergeleken. Voeg die toe als comparator test 2 etc. Let op: de comparator test kan nooit de referentiestandaard zijn.

[3] De referentiestandaard is de test waarmee definitief wordt aangetoond of iemand al dan niet ziek is. Idealiter is de referentiestandaard de Gouden standaard (100% sensitief en 100% specifiek). Let op! dit is niet de “comparison test/index 2”.

4 Beschrijf de statistische parameters voor de vergelijking van de indextest(en) met de referentietest, en voor de vergelijking tussen de indextesten onderling (als er twee of meer indextesten worden vergeleken).

Risk of bias assessment diagnostic accuracy studies (QUADAS II, 2011)

|

Study reference |

Patient selection

|

Index test |

Reference standard |

Flow and timing |

Comments with respect to applicability |

|

Kim 2011 (*RoB judgements from Nadarevic 2021) |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes*

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? No*

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes*

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes*

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes*

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? No*

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear*

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Unclear (n=24 received surgery instead of FNB, unclear whether a pathological assessment was included)

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Unclear, n=24 did not receive FNB.

Were all patients included in the analysis? No (n=11 refused a second FNB and were excluded from the analyses)

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? Yes*

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No*

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No*

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH* |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW*

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH* |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

|

|

|

Lin 2016 (*RoB judgements from Nadarevic 2022) |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes*

Was a case-control design avoided? Unclear

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? No*

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes*

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes*

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes*

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes*

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear*

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Unclear

Did patients receive the same reference standard? No*

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes* |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No*

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No*

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No*

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH* |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW* |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW* |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH* |

|

|

Fischer 2015 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Yes

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No |

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

|

Table of excluded studies

From the included studies by Nadarevic (2021; 2022)

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Hsiao 2019 |

No subanalyses for patients without cirrhosis |

|

Serste 2012 |

No subanalyses for patients without cirrhosis |

|

Besa 2017 |

No subanalyses for patients without cirrhosis |

|

Brunsing 2019 |

No subanalyses for patients without cirrhosis |

|

Dumitrescu 2013 |

No subanalyses for patients without cirrhosis |

|

Marks 2015 |

No subanalyses for patients without cirrhosis |

|

Min 2018a |

No subanalyses for patients without cirrhosis |

|

Serste 2012 |

No subanalyses for patients without cirrhosis |

|

Teefey 2003 |

No subanalyses for patients without cirrhosis |

|

Vietti Violi 2020 |

No subanalyses for patients without cirrhosis |

From the excluded by Nadarevic (2021, 2022)

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Abdelfattah, M. R. and Al-Mana, H. and Neimatallah, M. and Elsiesy, H. and Al-Sebayel, M. and Broering, D. C., (2013), Usefulness of combination of imaging modalities in the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma using Sonazoid(R)-enhanced ultrasound, gadolinium diethylene-triamine-pentaacetic acid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, and contrast-enhanced computed tomography |

Poster presentation |

|

Akhtar, S. and Hussain, M. and Ali, S. and Maqsood, S. and Akram, S. and Abbas, N., (2020), Hepatocellular carcinoma lesion characterization: single-institution clinical performance review of multiphase gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging--comparison to prior same-center results after MR systems improvements |

Unclear whether there were patients with(out) cirrhosis and how largre the propotion then was |

|

Alaboudy, A. and Inoue, T. and Hatanaka, K. and Chung, H. and Hyodo, T. and Kumano, S. and Murakami, T. and Moustafa, E. F. and Kudo, M., (2011), Multiparametric Gd-EOB-DTPA magnetic resonance in diagnosis of HCC: dynamic study, hepatobiliary phase, and diffusion-weighted imaging compared to histology after orthotopic liver transplantation |

At least 2 representative cases had cirrhosis, no apparent subanalyses for non-cirrhosis sub sample (if there were any) |

|

Becker-Weidman, D. J. and Kalb, B. and Sharma, P. and Kitajima, H. D. and Lurie, C. R. and Chen, Z. and Spivey, J. R. and Knechtle, S. J. and Hanish, S. I. and Adsay, N. V. and Farris, A. B., 3rd and Martin, D. R., (2011), Focal liver lesions: detection and characterization at double-contrast liver MR Imaging with ferucarbotran and gadobutrol versus single-contrast liver MR imaging |

Unclear whether there were patients with(out) cirrhosis and how largre the propotion then was |

|

Faletti, R. and Cassinis, M. C. and Fonio, P. and Bergamasco, L. and Pavan, L. J. and Rapellino, A. and David, E. and Gandini, G., (2015), Detection of hypervascular hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of SPIO-enhanced MRI with dynamic helical CT |

Cirrhosis etiology was described for all n=28 participants |

|

Heilmaier, C. and Lutz, A. M. and Bolog, N. and Weishaupt, D. and Seifert, B. and Willmann, J. K., (2009), (Differential diagnosis of focal liver lesions using contrast-enhanced MRI with SHU 555 A in comparison with unenhanced MRI and multidetector spiral-CT) |

Cirrhosis was confirmed in all patients |

|

Hori, M. and Murakami, T. and Kim, T. and Tsuda, K. and Takahashi, S. and Okada, A. and Takamura, M. and Nakamura, H., (2002), Diagnostic validity for sequential approach of dynamic image modalities in high-risk patients for hepatocellular carcinoma |

23/41 patients had hepatic cirrhosis, no subanalysis for non-cirrhotic |

|

Jung, G. and Poll, L. and Cohnen, M. and Saleh, A. and Vogler, H. and Wettstein, M. and Willers, R. and Modder, U. and Koch, J. A., (2005), The capsule appearance of hepatocellular carcinoma in gadoxetic acid-enhanced MR imaging: Correlation with pathology and dynamic CT |

Article in german |

|

Kang, H. T. and Shin, H. D. and Kim, S. B. and Song, I. H., (2012), Using low tube voltage (80kVp) quadruple phase liver CT for the detection of hepatocellular carcinoma: two-year experience and comparison with Gd-EOB-DTPA enhanced liver MRI |

Poster presentation |

|

Kim, B. and Lee, J. H. and Kim, J. K. and Kim, H. J. and Kim, Y. B. and Lee, D., (2018), Gd-EOB-DTPA dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging is more effective than enhanced 64-slice CT for the detection of small lesions in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma |

All patients had an underlying cause of cirrhosis described |

|

Lee, C. H. and Kim, K. A. and Lee, J. and Park, Y. S. and Choi, J. W. and Park, C. M., (2012), Diagnostic sensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma imaging and its application to non-cirrhotic patients |

Unclear whether there were patients with(out) cirrhosis and how largre the propotion then was |

|

Li, J. and Li, X. and Weng, J. and Lei, L. and Gong, J. and Wang, J. and Li, Z. and Zhang, L. and He, S., (2018), Hepatocellular carcinoma in patients undergoing living-donor liver transplantation. Accuracy of multidetector computed tomography by viewing images on digital monitors |

Unclear whether there were patients with(out) cirrhosis and how largre the propotion then was |

|

Lin, M. T. and Chen, C. L. and Wang, C. C. and Cheng, Y. F. and Eng, H. L. and Wang, J. H. and Chiu, K. W. and Lee, C. M. and Hu, T. H., (2011), Focal liver disease: comparison of dynamic contrast-enhanced CT and T2-weighted fat-suppressed, FLASH, and dynamic gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging at 1.5 T |

Seems to contain duplicate data with Lin 2016 |

|

Maetani, Y. S. and Ueda, M. and Haga, H. and Isoda, H. and Takada, Y. and Arizono, S. and Hirokawa, Y. and Shimada, K. and Shibata, T. and Kaori, T., (2008), MRI texture analysis for differentiation of malignant and benign hepatocellular tumors in the non-cirrhotic liver |

All n=41 patients had liver cirrhosis (underlying etiology described for all 41 patients) |

|

Semelka, R. C. and Shoenut, J. P. and Kroeker, M. A. and Greenberg, H. M. and Simm, F. C. and Minuk, G. Y. and Kroeker, R. M. and Micflikier, A. B., (1992), Low specificity of washout to diagnose hepatocellular carcinoma in nodules showing arterial hyperenhancement in patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome |

n=4 patients with hepatocellular cancer (of n=71) and all 4 had cirrhosis |

|

Stocker, D. and Marquez, H. P. and Wagner, M. W. and Raptis, D. A. and Clavien, P. A. and Boss, A. and Fischer, M. A. and Wurnig, M. C., (2018), |

Unclear diagnostic criteria (not specific) |

|

Van Wettere, M. and Purcell, Y. and Bruno, O. and Payance, A. and Plessier, A. and Rautou, P. E. and Cazals-Hatem, D. and Valla, D. and Vilgrain, V. and Ronot, M., (2019), |

mixed reference standards: histopatholoy on resection or biopsy, or clinical and biological follow-up of 12 months |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 08-03-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-01-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2021 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met hepatocellulaircarcinoom.

Werkgroep

- Prof. dr. R.A de Man, MDL-arts, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, NVMDL (voorzitter)

- Dr. K.J. van Erpecum, MDL-arts, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, NVMDL

- Dr. E.T.T.L. Tjwa, MDL-arts, Radboud UMC, Nijmegen, NVMDL

- Dr. R.B. Takkenberg, MDL-arts, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, NVMDL

- Dr. F.G.I. van Vilsteren, MDL-arts, UMCG, Groningen, NVMDL

- Dr. D. Sprengers, MDL-arts, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, NVMDL

- Dr. M.J. Coenraad, MDL-arts, LUMC, Leiden, NVMDL

- Prof. dr. B. van Hoek, MDL-arts, LUMC, Leiden, NVMDL

- Dr. N. Haj Mohammad, Internist-oncoloog, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, NIV

- Dr. J. de Vos-Geelen, Internist-oncoloog, MUMC, Maastricht, NIV

- Drs. J.A. Willemse, Directeur Nederlandse Leverpatiënten Vereniging

- Prof. dr. M.G.E. Lam, Nucleair geneeskundige, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, NVNG

- Prof. dr. J. Verheij, Patholoog, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, NVvP

- Dr. M. (Michail) Doukas, Patholoog, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, NVvP

- Dr. A.M. Mendez Romero, Radiotherapeut, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, NVvR

- Dr. A.E. Braat, Chirurg, LUMC, Leiden, NVvH

- Dr. M.W. Nijkamp, Chirurg, UMCG, Groningen, NVvH

- Prof. Dr. J.N.M. Ijzermans, Chirurg, ErasmusMC, Rotterdam, NVvH

- Drs. J.I. Erdmann, Chirurg, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, NVvH

- Dr. M.C. Burgmans, Radioloog, LUMC, Leiden, NVvR

- Drs. F.E.J.A. Willemssen, Radioloog, ErasmusMC, Rotterdam, NVvR

- Prof. Dr. O.M. (Otto) van Delden, Radioloog, AmsterdamUMC, Amsterdam, NVvR

- J.I. Franken, Verpleegkundig specialist, ErasmusMC, Rotterdam, V&VN

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. C. Gaasterland, Adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. D. Nieboer, Adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. N. Zielonke, Adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. M. Oerbekke, Adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. M. te Lintel Hekkert, Junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. S van Duijn, Junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. A. van Hoeven, Junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- D.P. Gutierrez, projectsecretaresse, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Achternaam werkgroeplid |

Hoofdfunctie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen |

Persoonlijke relaties |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek |

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie |

Overige belangen |

|

De Man (vz.) |

Hoogleraar Hepatologie, Erasmus MC Rotterdam |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Haj Mohammad |

Internist-oncoloog, Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht |

Penningmeester Dutch Upper GI Cancer (DUCG), onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Lid wetenschappelijke raad Dutch Hepato and Cholangio Carcinoma Group(DHCG) |

Geen |

|

Burgmans |

Sectiehoofd interventie radiologie LUMC |

Voorzitter Nederlandse Vereniging Interventieradiologie |

Geen |

Geen |

PROMETHEUS studie, subsidie KWF, project leider |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Lam |

Nucleair geneeskundige, UMC Utrecht |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Terumo, Quirem Medical en Boston scientific leveren financiële steun aan wetenschappelijke projecten |

Geen |

Het UMC Utrecht ontvangt royalties en milestone payments van Terumo/Quirem Medical |

|

Franken |

Verpleegkundig Specialist Levertumoren |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Verheij |

Hoogleraar hepatopancreatobiliaire Pathologie aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam |

lid medische adviesraad NLV (onbezoldigd) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Sprengers |

MDL-arts Erasmus MC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Ik doe translationeel onderzoek met als doel behandeling van patiënten met een HCC te verbeteren. Daarbij wordt soms samengewerkt met famaceutische partijen die producten ontwikkelen die hieraan bij kunnen dragen. Te allen tijde betreft dit objectief wetenschappelijk onderzoek zonder winstoogmerk. |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Van Vilsteren |

MDL-arts UMCG 0,9 fte |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Takkenberg |

Maag- Darm Leverarts met specifiek aandachtsgebied leverziekten. Sinds 1-4-2015 in deinst van het Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC. |

Geen |

Betaald adviesschap: |

Geen |

Ik ben PI van de PEARL studie. Dit is een dubbelblind gerandomiseerde studie bij patiënten die een transjugulaire intrahepatische portosysthemische shunt (TIPS) krijgen. Patiënten worden gerandomiseerd tussen profylactisch lactulose en rifaximin versus lactulose en placebo. Doel is het voorkomen van post-TIPS hepatische encafalopathie (EudraCT-nummer 2018-004323-37). Deze studie wordt gefinancierd door ZonMW en ondersteund door Norgine. Zij leveren de rifaximin en placebo tabletten. |

Secretaris Dutch Hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma Group (DHCG) |

Geen |

|

Van Erpecum |

MDL-arts UMC Utrecht |

Associate Editor European Journal of Internal Medicine (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Willemssen |

Abdominaal Radioloog |

Bestuurslid abdominale sectie NVvR (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Méndez Romero |

Staflid afdeling radiotherapie in het Erasmus MC |

Als staflid in ee adademisch ziekenhuis ben ik in loondienst van het ErasmusMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Tjwa |

MDL arts / hepatoloog |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Braat |

chirurg |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Nijkamp |

Chirurg Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Willemse |

Directeur Nederlandse Leverpatiënten Vereniging |

* Bestuurslid Liver Patients International (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

IJzermans |

Hoofd HPB & Transplantatiechirurgie Erasmus MC |

- |

Niet van toepassing |

Nee |

Niet van toepassing |

Niet van toepassing |

Nee |

|

Vos, de - Geelen |

* Internist - Medisch Oncoloog Maastricht UMC+ |

Has served as a constultant for Amgen, AstraZeneca, MSD, Pierre Fabre and Servier and has received institutional research funding from Servier |

Has served as a constultant for Amgen, AstraZeneca, MSD, Pierre Fabre and Servier and has received institutional research funding from Servier. Geen directe financiële belangen in een farmaceutisch bedrijf |

Geen |

* Servier: Microbioomonderzoek - Projectleider |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Hoek, van |

* Hoogleraar Hepatologie, Universiteit Leiden |

* Norgine Pharma - patient voorlichtingsmateriaal maken, onder andere podcast - betaald |

Geen |

Nee |

* Roche - Piranga Studie (hepatitis B) - Projectleider |

Geen |

Nee |

|

Delden, van |

Radioloog, Amsterdam UMC |

Voorzitter DHCG |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Doukas |

Universitair Medisch Specialist, Patholoog, Afdeling Pathologie Erasmus MC, Rotterdam |

Geen |

Niet van toepassing |

Niet van toepassing |

Niet van toepassing |

Niet van toepassing |

Niet van toepassing |

|

Coenraad |

Associate professor, MDL arts Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum (1.0 fte) |

Nevenfuncties: |

Niet van toepassing |

Niet van toepassing |

* Horizon2020 - EU Project id 945096. Title ‘Novel treatment of acute-on-chronic liver failure using synergistic action of G-CSF and TAK-242 - Geen projectleider |

Niet van toepassing |

Niet van toepassing |

|

Erdmann |

Chirurg AUMC |

geen |

geen |

geen |

AGEM - perfusie onderzoek (50K), rol als projectleider |

geen |

geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door deelname van de afgevaardigde patiëntenvereniging Nederlandse Leverpatiëntenvereniging in de werkgroep. De afgevaardigde heeft meebeslist bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Nederlandse Leverpatiëntenvereniging en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn voor deze richtlijn, gezien het aantal patiënten kleiner is dan 5000.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met Hepatocellulaircarcinoom. De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbeveling(en) uit de eerdere richtlijn Hepatocellulaircarcinoom op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door de deelnemende WV-en, de V&VN en de Nederlandse Leverpatiëntenvereniging.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE-gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |