De rol van urine biomarkers bij de diagnostiek van hematurie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de rol van urine biomarkers bij de diagnostiek van hematurie?

Aanbeveling

Gebruik geen urinemarkers bij patiënten met hematurie teneinde urotheelcarcinoom op te sporen of uit te sluiten, behalve in onderzoek setting.

Overwegingen

De ideale situatie zou zijn dat een urinemarker gebruikt wordt om een cystoscopie overbodig te maken. Dit vereist dat een marker een zeer hoge sensitiviteit en hoge negatieve voorspellende waarde heeft. De werkgroep heeft besloten dat de sensitiviteit 100% zou moeten naderen, gezien de consequenties van het missen van een urotheelcarcinoom. Het missen van een maligniteit weegt niet op tegen de potentiële winst van mensuren, minder belasting voor patiënt en reductie van complicaties door het uitsparen van een cystoscopie.

De bovengenoemde onderzoeken, veelal van recente datum, laten zien dat urinemarkers in opkomst zijn. Sommigen hebben veelbelovende resultaten. Echter, met een sensitiviteit van 95% wordt nog altijd 5% van de blaastumoren gemist. De werkgroep is van mening dat dit te veel is.

De werkgroep is van mening dat naar aanleiding van de huidige literatuurstudie het gebruik van urinemarkers als vervanging van een cystoscopie bij de initiële analyse van hematurie ten zeerste af te raden is. In onderzoek setting zou dit eventueel mogelijk zijn.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Bij patiënten met hematurie is het van belang dat met name urotheelcarcinoom van de hoge en lage urinewegen tijdig gediagnosticeerd wordt. In 95% van de gevallen betreft dit urotheelcarcinoom van de blaas (Raman, 2011). Tal van urine markers zijn ontwikkeld die het risico op urotheelcarcinoom van de blaas kunnen aantonen. Als er een accurate urinemarker test zou zijn, betekent dat minder belasting voor patiënt en behandelaar met mogelijk ook een kosten reductie. Een aantal van deze testen is inmiddels op de markt. De vraag is wat de exacte waarde en toepasbaarheid zijn bij patiënten met hematurie.

Er is een scala van urinemarkers op de markt, die allen op verschillende manieren werken. Voorbeelden zijn:

- ADXBladder (ELISA-test om het eiwit MCM5 in de urine aan te tonen)

- AssureMDX (het aantonen van een combinatie van epigenetische [DNA-methylering] en genetische [mutaties] afwijkingen in de urine)

- UroVysion (fluorescentie in situ hybridisatie (FISH) probe set)

- NMP-22 (aanwezigheid van nucleair matrix proteïne in de urine)

- 'BTA' (blaas tumor antigeen)

- ImmunoCyt/uCyt+ (fluorescente monoclonale antilichamen tegen M344, LDQ10 en 19A211)

- CxBladder (reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction van 5 genen die een verhoogd risico op blaaskanker geven)

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Diagnostic performance of biomarkers in detecting bladder cancer

|

Very Low GRADE |

The sensitivity of the included biomarkers (AssureMDx, BTA, CxBladder, qualitative and quantitative NMP-22, and ImmunoCyt/uCyt+, UroVysion and ADXBladder ranged from 0.67 to 0.95, the specificity ranged from 0.68 to 0.87.

The summary statistics showed the highest positive likelihood ratio for the AssureMDx and ImmunoCyt/uCyt+ and the lowest negative likelihood ratio for the ADXbladder and AssureMDx.

Sources: Sathianathen (2018) and Dudderidge (2019) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Sathianathen (2018) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis about the diagnostic performance of FDA-approved biomarkers in the evaluation of primary hematuria. The SR only included studies that investigated the accuracy of an FDA approved biomarker in detecting primary bladder cancer. Participants were individuals presenting with hematuria for the first time for evaluation. The biomarker test was compared to cystoscopy. Only cohort studies were included, case control studies were excluded. The search period was up to June 2017. Searches were performed in the databases MEDLINE,EMBASE, ScienceDirect, Cochrane Libraries, HTA database, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. The quality of included studies was assessed using the QUADAS-2 tool. The biomarkers investigated in these studies were AssureMDx, Bladder tumor antigen (BTA), CxBladder, NMP22, UroVysion and ImmunoCyt/uCyt+. A total of 14 studies were found to meet the inclusion criteria. The review did not find studies that compared the diagnostic accuracy of several biomarkers within one study. The diagnostic accuracy of a biomarker was pooled when possible.

Dudderidge (2019) performed a prospective cohort study about the diagnostic performance of the ADXBladder test. The study was performed in seven centres in the UK, investigating patients presenting with visible or nonvisible hematuria at urology clinics. Patients with a diagnosis of bladder, prostate, or renal cancer were excluded. In total, 856 patients were enrolled of whom 74 were found to have a bladder cancer. The performance of the ADXBladder test was compared to cytology data of 178 patients, and the final diagnosis of bladder cancer based on the reference cystoscopy and imaging data. The objective of the study was to investigate if the ADXBladder test could be used to replace cytology.

Results

Diagnostic performance of biomarkers in detecting bladder cancer

1. Sensitivity and specificity

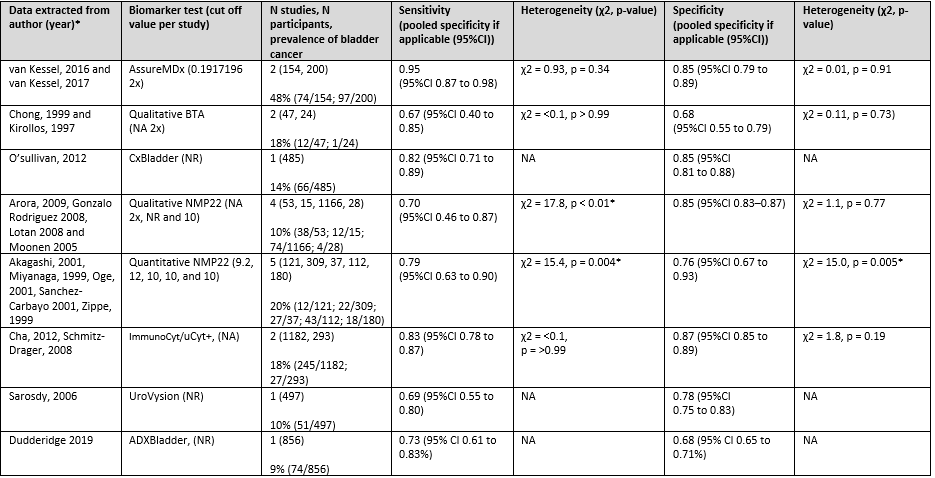

The systematic review by Sathianathen (2018) investigated the biomarker test AssureMDx, BTA, CxBladder, NMP22, UroVysion and ImmunoCyt/uCyt+. The cohort study by Dudderidge (2019) investigated the biomarker test ADXbladder. The diagnostic performance of each test will be discussed.

1.1 AssureMDx

The systematic review by Sathianathen (2018) included two studies (van Kessel 2016 and van Kessel 2017) with 154 and 200 participants respectively, to investigate the diagnostic performance of the AssureMDx test. Both studies used a cut off value of 0.1917196. The pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.95 (95%CI 0.87 to 0.98) and 0.85 (95%CI 0.79 to 0.89) respectively. No significant heterogeneity among the two studies was found.

1.2 BTA qualitative

The systematic review by Sathianathen (2018) included two studies (Chong 1999 and Kirollos 1997) with 154 and 200 participants respectively, to investigate the diagnostic performance of the BTA qualitative test. The cut off value for this test was not applicable. The pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.67 (95%CI 0.40 to 0.85) and 0.68 (95%CI 0.55 to 0.79) respectively. No significant heterogeneity among the two studies was found (Table 1).

1.3 CxBladder

The systematic review by Sathianathen (2018) included one study (O’sullivan, 2012) with 485 participants to investigate the diagnostic performance of the CxBladder test. The cut off value for this test was not reported. The sensitivity and specificity were 0.82 (95%CI 0.71 to 0.89) and 0.85 (95%CI 0.81 to 0.88) respectively.

1.4 Qualitative NMP-22

The systematic review by Sathianathen (2018) included four studies (Arora, 2009, Gonzalo Rodriguez 2008, Lotan 2008 and Moonen 2005) with 53, 15, 1166, 28 participants respectively, to investigate the diagnostic performance of the qualitative NM-22P. The cut off value for this test not applicable (two studies), not reported (one study) or 10 (one study). The pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.70 (95%CI 0.46 to 0.87) and 0.85 (95%CI 0.83 to 0.87) respectively. Heterogeneity among studies (sensitivity) was significant χ2 = 17.8, p < 0.01. The cause of heterogeneity is not described, however different cut off values were often not described.

1.5 Quantitative NMP-22

The systematic review by Sathianathen (2018) included five studies (Akagashi, 2001, Miyanaga, 1999, Oge, 2001, Sanchez-Carbayo 2001, Zippe, 1999) with 121, 309, 37, 112 and 180 participants respectively, to investigate the diagnostic performance of the quantitative NMP-22. The cut off value for this test was 9.2, 12, 10, 10 and 10 respectively. The pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.79 (95%CI 0.63 to 0.90) and 0.76 (95%CI 0.67 to 0.93) respectively. Heterogeneity among studies (sensitivity and specificity) was significant: χ2 = 15.4, p = 0.004 and χ2 = 15.0, p = 0.005. The cause of heterogeneity was not described, however different cut off values were reported.

1.6 ImmunoCyt/uCyt+

The systematic review by Sathianathen (2018) included two studies (Cha, 2012, Schmitz-Drager, 2008) with 1182 and 293 participants respectively, to investigate the diagnostic performance of ImmunoCyt/uCyt+. The cut off value for this test was not applicable. The pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.83 (95%CI 0.78–0.87) and 0.87 (95%CI 0.85 to 0.89) respectively. No significant heterogeneity among the two studies was found (Table 1).

1.7 UroVysion

The systematic review by Sathianathen (2018) included one study (Sarosdy, 2006) with 497 participants, to investigate the diagnostic performance of UroVysion. The cut off value was not reported. The sensitivity and specificity were 0.69 (95%CI 0.55 to 0.80) and 0.68 (95%CI 0.55 to 0.79) respectively.

1.8 ADXBladder

The cohort study by Dudderidge (2019) investigated the diagnostic performance of the ADXBladder test. The cut off value was not reported. The sensitivity and specificity were 0.73 (95% CI 0.61 to 0.83%) and 0.68 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.71%) for the prediction of bladder cancer respectively.

Table 1 Sensitivity and specificity (pooled if applicable) as per cut off value per biomarker as reported by Sathianathen (2018), supplemented by data published by Dudderidge (2019).

* Statistically significant, , NA: not applicable NR: not reported

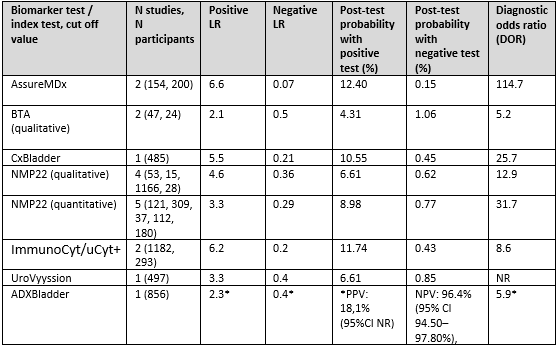

2. Summary statistics

The systematic review by Sathianathen (2018) reported the positive likelihood ratio, negative likelihood ratio, post test probability with a positive test, post test probability with a negative test and diagnostic odds ratio for the biomarkers AssureMDx, qualitative BTA, CxBladder, qualitative and quantitative NMP-22, ImmunoCyt/uCyt+ and UroVysion. The cohort study by Dudderidge (2019) did not report these outcome measures, so the result is based on a calculation with the reported study data. Post-test probabilities could not be calculated, because this requires an estimation of the pretest probability (based on patient characteristics), and this was unknown. So instead, the positive predictive value was calculated, and the negative predictive value was taken over from the study results.

Based on the summary statistics, the positive likelihood ratio is highest for the AssureMDx, followed by the ImmunoCyt/uCyt+. The negative likelihood ratio is lowest for the ADXBladder and AssureMDx. The post-test probability is highest for the AssureMDx, ImmunoCyt/uCyt+ and CxBladder. The post-test probability is lowest for the AssureMDx, ImmunoCyt/uCyt+ and CxBladder. The ADXBladder also showed a high negative predictive value. The diagnostic odds ratio was highest for the AssureMDx (Table 2).

Table 2 Positive likelihood ratio, negative likelihood ratio and post test probability with a positive and negative test as reported by Sathianathen (2018), supplemented by data published by Dudderidge (2019)

*Not reported in study but calculated with study data

NR: not reported

PPV: positive predictive value, NPV: negative predictive value

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure “diagnostic performance of biomarkers in detecting bladder cancer” was downgraded by 3 levels to a low GRADE because of study limitations (risk of bias: blinding for the outcome of the biomarker test when cystoscopy was performed was not described in most studies), inconsistency (heterogeneity among studies) and imprecision (the number of included patients).

For the comparison between biomarkers downgrading further for indirectness would have been appropriate since biomarkers were not compared to each other within studies.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the diagnostic performance of biomarkers tests versus cystoscopy in the evaluation of primary hematuria for bladder cancer?

P patients: Patients with primary hematuria.

I intervention: Biomarker tests.

C control: Cystoscopy.

O outcome: Diagnostic performance in detecting bladder cancer.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered diagnostic performance in detecting bladder cancer as a critical outcome measure for decision making.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until September 28th, 2020. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 483 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Patients diagnosed with primary hematuria and no history of bladder cancer.

- Investigation of an FDA approved biomarker test compared to cystoscopy.

- Diagnostic performance in detecting bladder cancer.

- Systematic review or cohort designs.

After reading the full text, 90 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 2 studies were included.

Results

Two studies were included in the analysis of the literature: one systematic review and one cohort study. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Dudderidge T, Stockley J, Nabi G, Mom J, Umez-Eronini N, Hrouda D, Cresswell J, McCracken SRC. A Novel, non-invasive Test Enabling Bladder Cancer Detection in Urine Sediment of Patients Presenting with Haematuria-A Prospective Multicentre Performance Evaluation of ADXBLADDER. Eur Urol Oncol. 2020 Feb;3(1):42-46.

- Raman JD, Messer J, Sielatycki JA, Hollenbeak CS. Incidence and survival of patients with carcinoma of the ureter and renal pelvis in the USA, 1973-2005. BJU Int. 2011 Apr;107(7):1059-64.

- Sathianathen NJ, Butaney M, Weight CJ, Kumar R, Konety BR. Urinary Biomarkers in the Evaluation of Primary Hematuria: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Bladder Cancer. 2018 Oct 29;4(4):353-363.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy studies

Research question: What is the diagnostic performance of biomarkers tests versus cystoscopy in the evaluation of primary hematuria for bladder cancer?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics

|

Index test (test of interest) |

Reference test

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Sathianathen, 2018

|

SR and meta-analysis

Literature search up to June 2017

A: Akagashi, 2001 B: Arora, 2009 C: Cha, 2012 D: Chong, 1999 E: Gonza lo Rodriguez, 2008 F: Kirollos, 1997 G: Lotan, 2008 H: Miyanaga, 1999 I: Moonen, 2005 J: Oge, 2001 K: O’sullivan, 2012 L: Sanchez-Carbayo 2001 M: Sarosdy, 2006 N: Schmitz-Drager, 2008 O: van Kessel, 2016 P: van Kessel, 2017 Q: Zippe, 1999

Study design: cohort: both prospective and retrospective

Setting and Country: A: Japan B: India C: Germany/Italy D: Singapore E: Spain F: UK G: International H: Japan I: Netherlands J: Turkey K: Australasia L: Spain M: USA N: Germany O: Netherlands P: Netherlands Q: USA

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: NJS has received support from the Cloverfields Foundation and The Institute for Prostate and Urologic Cancers (University of Minnesota). No conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria SR: Both retrospective and prospective trials were included if participants had no prior diagnosis of bladder cancer, had presented with hematuria for primary evaluation and had been tested with both an FDA approved urinary biomarker and cystoscopy.

Exclusion criteria SR: Studies which included patients with recurrent disease or those presenting with other symptoms (e.g., voiding symptoms) had to separately report the results for cases who presented with hematuria for primary evaluation to be eligible for inclusion.

17 studies included

Important patient characteristics:

Number of participants (N) A: 121 B: 53 C: 1182 D: 47, E: 15 F: 24 G: 1166 H: 309 I: 28 J: 37 K: 485 L: 112 M: 497 N: 293 O: 154 P: 200 Q: 180

Age [range] A: NR B: 59 [range 33–83] C: 65 [range 18–93] D: NR E: 59.8 [range 27–85] F: NR G: 1166, 59 [range 18–96] H: NR I: NR J: NR K: 69 [IQR 59–77] L: 65.5 [range 23 to 87] M: 63 [range 40–97] N: 59 [range 24–89] O: 68 [range 38–91] P: NR Q: NR |

Describe index and comparator tests* and cut-off point(s):

Biomarker, biomarker cut off

A: NMP22 (quantitative), 9.2 B: NMP22 (qualitative), NA C: uCyt, NA D: BTA (qualitative), NA E: NMP22 (qualitative), 10 F: BTA (qualitative), NA G: NMP22 (qualitative), NA H: NMP22 (quantitative), 12 I: NMP22 (qualitative), NR J: NMP22 (quantitative), 10 K: CxBladder, NR L: NMP22 (quantitative), 10 M: UroVysion, NR N: uCyt, NA O: AssureMDx, 0.1917196 P: AssureMDx, 0.1917196 Q: NMP22 (quantitative), 10

|

Describe reference test and cut-off point(s):

All studies compared the index test to cystoscopy (see inclusion criteria) and nine studies compared the index test also to cytology (see below). Cut off points for the reference tests as well as the time between the index test and reference tests are not described by Sathianathen (2018).

A: Cystoscopy B: Cystoscopy + cytology C: Cystoscopy + cytology D: Cystoscopy + cytology E: Cystoscopy F: Cystoscopy + cytology G: Cystoscopy H: Cystoscopy + cytology I: Cystoscopy + cytology J: Cystoscopy K: Cystoscopy + cytology L: Cystoscopy + cytology M: Cystoscopy N: Cystoscopy O: Cystoscopy P: Cystoscopy Q: Cystoscopy + cytology

Prevalence (%) [based on refence test at specified cut-off point] A: 9.9% B: 7.2% C: 20.7% D: 25.5% E: 80% F: 4.1% G: 6.3% H: 7.1% I: 14.3% J: 73% K: 13.6% L: 38.4% M: 10.2% N: 9.2% O: 48.1% P: 48.5% Q: 10%

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%) This was not reported by Sathianathen (2018)

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described. This was not reported by Sathianathen (2018)

|

Endpoint of follow-up: A: Cancers diagnosed on the reference test B: Cancers diagnosed on the reference test C: Cancers diagnosed on the reference test D: Cancers diagnosed on the reference test E: Cancers diagnosed on the reference test F: Cancers diagnosed on the reference test G: Cancers diagnosed on the reference test H: Cancers diagnosed on the reference test I: Cancers diagnosed on the reference test J: Cancers diagnosed on the reference test K: Cancers diagnosed on the reference test L: Cancers diagnosed on the reference test M: Cancers diagnosed on the reference test N: Cancers diagnosed on the reference test O: Cancers diagnosed on the reference test P: Cancers diagnosed on the reference test Q: Cancers diagnosed on the reference test

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

1. AssureMDx Individual study results were not reported by Sathianathen 2018 O (N=154): NR P (N=200): NR

Pooled sensitivity (AssureMDx, cut off = 0.1917196): 0.95 [95%CI 0.87 to 0.98] Heterogeneity: χ2 = 0.93, p = 0.34

Pooled specificity (AssureMDx, cut off = 0.1917196): 0.85 [95%CI 0.79 to 0.89] Heterogeneity: χ2 = 0.01, p = 0.91.

Summary diagnostic odds ratio (DOR), positive likelihood ratio (posLR) and negative likelihood ratio (negLR) was 114.7, 6.6 and 0.07.

2. Bladder tumor antigen (qualitative) Individual study results were not reported by Sathianathen 2018 D (N=47): NR F (N=24): NR

Pooled sensitivity (BTA (qualitative), cut off = NR): 0.67 [95%CI 0.40 to 0.85] Heterogeneity: χ2 = <0.1, p > 0.99)

Pooled specificity (BTA qualitative): 0.68 [95%CI 0.55 to 0.79] Heterogeneity: χ2 = 0.11, p = 0.73).

Summary diagnostic odds ratio (DOR), positive likelihood ratio (posLR) and negative likelihood ratio (negLR) was 5.2, 2.1 and 0.5.

3. CxBladder Individual study results were not reported by Sathianathen 2018 B (N=53): E (N=15) G (N=1166) I (N=28)

Pooled sensitivity Cxbladder, cut off = NR): 0.82 [95%CI 0.71 to 0.89] Heterogeneity: NA

Pooled specificity (BTA qualitative): 0.85 [95%CI 0.81–0.88] Heterogeneity: NA

Summary diagnostic odds ratio (DOR), positive likelihood ratio (posLR) and negative likelihood ratio (negLR) was 25.7, 5.5 and 0.21.

4. Qualitative NMP22 Individual study results were not reported by Sathianathen 2018 K (N=485): NR

Pooled sensitivity NMP22 (qualitative), cut off = NR): 0.70 [95%CI 0.46–0.87] Heterogeneity: χ2 = 17.8, p < 0.01.

Pooled specificity (NMP22 qualitative): 0.85 [95%CI 0.83–0.87]. Heterogeneity: χ2 = 1.1, p = 0.77).

The summary DOR, posLR and negLR was 15.2, 4.6 and 0.36, respectively.

5. Quantitative NMP22 Individual study results were not reported by Sathianathen 2018 A (n=121): NR H (n=309): NR J (n=37): NR L (n=112): NR Q (n=180): NR

Pooled sensitivity quantitative NMP22, and cut-off point 9.2 (A), 10 (J, L, Q), 12 (H)) 0.79 [95%CI 0.63 to 0.90] Heterogeneity: χ2 = 15.4, p = 0.004.

Pooled specificity quantitative NMP22, and (cut-off point= 9.2 (A), 10 (J, L, Q), 12 (H)): 0.76 [95%CI 0.67–0.93]. Heterogeneity: χ2 = 15.0, p = 0.005. The summary DOR, posLR and negLR was 12.9, 3.3 and 0.29, respectively.

6. uCyt+ Individual study results were not reported by Sathianathen 2018 C (n=1182): NR N (n=293): NR

Pooled sensitivity (cut off point = NR): 0.83 [95%CI 0.78–0.87] Heterogeneity:

Pooled specificity [cut off point = NR]: 0.87 [95%CI 0.85–0.89] Heterogeneity: χ2 = 1.8, p = 0.19. DOR, posLR and negLR was 31.7, 6.2 and 0.20. The summary DOR, posLR and negLR was 31.7, 6.2 and 0.20, respectively. uCyt+ had the second highest DOR of the included biomarkers.

7. UroVision Individual study results were not reported by Sathianathen 2018 M (n=497): NR

Pooled sensitivity (cut off point = NR): 0.69 [95%CI 0.55 to 0.80] Heterogeneity: NA

Pooled specificity (cut off point = NR): 0.78 [95%CI 0.75 to 0.83]. Heterogeneity: NA

The calculated DOR, posLR and negLR was 8.6, 3.3 and 0.4, respectively. |

Study quality (ROB): Overall, the quality of included studies was moderate.

Place of the index test in the clinical pathway: triage

Choice of cut-off point: cut off points for biomarker tests were not always described and could be a source of bias for the performance of these biomarkers.

Facultative: The results from this study and the literature do not currently provide strong evidence that biomarkers can be used to replace cystoscopy in the diagnostic evaluation of hematuria.

Personal remarks on study quality, conclusions, and other issues (potentially) relevant to the research question: the investigators were not always blinded for patient characteristics and other clinical data which may have introduced bias, so results should be taken with caution.

Sensitivity analyses (excluding small studies; NA

Heterogeneity: heterogeneity was small and non-significant among studies investigating the same biomarkers.

|

|

Dudderidge, 2019 |

Type of study: cohort study

Setting and country: Sunderland, UK

Funding and conflicts of interest: This study was supported by Arquer Diagnostics Ltd. |

Inclusion criteria: patients presenting with visible or nonvisible hematuria presenting at urology clinics across UK

Exclusion criteria: previous diagnosis of bladder, prostate, or renal cancer

N=856

Prevalence bladder tumor: 74

Median age and interquartile range: 64 yr. (54–73 yr.)

Sex: % M / % F 74.3% M

Other important characteristics: NR

|

Describe index test: ADXBLADDER

Cut-off point(s): NR

Comparator test: cytology

Cut-off point(s): NR

|

Describe reference test: Cystoscopy + imaging

Cut-off point(s): NR

|

Time between the index test and reference test: less than 4 hours

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%): 45

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described: yes |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available): 8.ADXBLADDER Sensitivity: 73.0% (95% CI 61.40 to 82.60%) Specificity: 68.4% (95% CI 65.00 to 71.70%) ROC: 0.75 (95% CI 0.69–0.81)

|

Study quality (ROB): see ROB table

Place of the index test in the clinical pathway: replacement of cytology

Choice of cut-off point: cut off points for biomarker test and cytology were not described and could be a source of bias for the performance of these biomarkers.

Facultative: The ADXBLADDER non-invasive urine test is an easy-to-perform ELISA test, compatible with general laboratory equipment available in most hospital laboratories, and can provide results within 3 h, without the need for a pathologist, making it a potential low-cost alternative to cytology.

Personal remarks on study quality, conclusions, and other issues (potentially) relevant to the research question: the study did not investigate the place of the ADXBLADDER in triage before cystoscopy, but replacement of cytology. The authors had a small number of cytology comparisons which makes it difficult to draw conclusions.

Sensitivity analyses (excluding small studies; NA

Heterogeneity: heterogeneity was small and non-significant among studies investigating the same biomarkers. |

*comparator test equals the C of the PICO; two or more index/ comparator tests may be compared; note that a comparator test is not the same as a reference test (golden standard)

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/not applicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Sathianathen, 2018 |

Yes |

Yes |

No: description of excluded studies is missing |

Yes |

NA |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Unclear: only reported about systematic review itself but not about the included studies |

Risk of bias assessment

Research question: What is the diagnostic performance of biomarkers tests versus cystoscopy in the evaluation of primary hematuria for bladder cancer?

|

Study reference |

Patient selection

|

Index test |

Reference standard |

Flow and timing |

Comments with respect to applicability |

|

Dudderidge, 2019 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes/

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes/

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes/

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes/No/Unclear

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes/No/Unclear (manufacturer instructions were followed, threshold was not mentioned)

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes/No/Unclear

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes/No/Unclear

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Yes/No/Unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes/No/Unclear

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes/No/Unclear

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes/No/Unclear

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? Yes/No/Unclear

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? Yes/No/Unclear

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? Yes/No/Unclear

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW/ |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK:

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

|

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Abern, 2014 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Abogunrin, 2012 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Afsharpad, 2018

|

Wrong design: case control, wrong participants: clinical indication for bladder cancer screening and patients with history of bladder cancer |

|

Anastasi, 2020 |

Wrong patients: patients with persistent lower urinary tract symptoms |

|

Bangma, 2013 |

Wrong patients: screening in asymptomatic population |

|

Barbieri, 2012 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Beukers, 2013 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Bott, 2008 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Chahal, 2001 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Chen, 2012 |

Excluded based on TiAb |

|

Cheng, 2019

|

Wrong design: case control, wrong comparison: patients with known bladder cancer compared with cancer free hematuria controls |

|

Choi, 2010 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Chou, 2010 |

Wrong participants: asymptomatic population |

|

Chou, 2015

|

More recent SR available by Sathianathen 2018 which matches better with PICO |

|

Critselis, 2019 |

Excluded based on TiAb |

|

Dahmcke, 2016 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Darling, 2017

|

Wrong design: clinician evaluation, wrong comparison: clinical use of the Cxbladder test was evaluated |

|

Davidson, 2019

|

Wrong comparison: CxBladder test was combined with imaging data and patient characteristics to form CxBladder triage |

|

de Martino, 2015 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017

|

|

Dogan, 2013 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Duquesne, 2017 |

Background article / narrative review |

|

Efthimiou, 2011 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Emmert-Streib, 2013 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017

|

|

Erdem, 2003 |

Excluded based on TiAb |

|

Fantony, 2015 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Fantony, 2017 |

Excluded based on TiAb |

|

Grossman, 2005 |

Excluded based on TiAb |

|

Guo, 2018 |

Wrong design: case control |

|

Hautmann, 2004 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Hayashi, 2020 |

Excluded based on TiAb |

|

Hofbauer, 2018 |

Excluded based on TiAb |

|

Holyoake, 2008 |

Excluded based on TiAb |

|

Horstmann, 2010 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017

|

|

Huber, 2012 |

Excluded based on TiAb |

|

Hwang, 2011 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Jeong, 2012 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Jin, 2014 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to june 2017 |

|

Karnes, 2012 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Kavalieris, 2015 |

Excluded based on TiAb |

|

Kim, 2016 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Kim, 2016 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Kim, 2018 |

Wrong design: case control |

|

Lang, 2017 |

Excluded based on TiAb |

|

Lin, 2019 |

Wrong design: case control |

|

Liu, 2016 |

Excluded based on TiAb |

|

Lotan, 2008 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Lotan, 2009 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Lotan, 2014 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Lough, 2018 |

Wrong design: clinician evaluation |

|

Lucca, 2019 |

Excluded based on TiAb |

|

Maas, 2019 |

Wrong design: non-systematic review |

|

Mahnert, 2003 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Margel, 2011 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Miah, 2012 |

Excluded based on TiAb |

|

Miyake, 2012 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Muhammad, 2019 |

Wrong design: cross sectional study

|

|

Muto, 2014 |

Wrong intervention: isomorph erythrocytes |

|

Nisman, 2002 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Oikawa, 2018 |

Wrong intervention: serum biomarker |

|

O'Sullivan, 2012 |

Included in Sathianathen 2018 |

|

Ou, 2020 |

Wrong design: case control study and pilot study |

|

Parekattil, 2003 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Piao, 2019 |

Excluded based on TiAb |

|

Ponsky, 2001 |

Wrong Participants: 13% known history of bladder cancer |

|

Quek, 2002 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Rodgers, 2006 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Rodgers, 2006 |

Excluded based on TiAb |

|

Roobol, 2010 |

Screening in asymptomatic population |

|

Roperch, 2016 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Sánchez-Carbayo, 2001 |

Excluded based on TiAb

|

|

Saeb-Parsy, 2001 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017

|

|

Saeb-Parsy, 2012 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017

|

|

Sagnak, 2011 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Sawczuk, 2005 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Schmitz-Dräger, 2008 |

Excluded based on TiAb

|

|

Schmitz-Drager, 2007 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017

|

|

Schroeder, 2004 |

Wrong population: detection recurrence of bladder cancer |

|

Srirangam, 2011 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Stoeber, 2002 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Su, 2003 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Tan, 2017 |

Wrong design: protocol, no data |

|

Tan, 2018 |

Only 'omic-based' biomarkers from 2013 to 2017 |

|

Tao, 2015 |

Excluded based on TiAb |

|

Todenhöfer, 2013 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017

|

|

Turkeri, 2014 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

van Kessel, 2017 |

Included in Sathianathen 2018 |

|

van Kessel, 2020 |

New diagnostic model, no individual biomarkers |

|

van Rhijn, 2009 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Wallace, 2018 |

Wrong design: case control |

|

Walsh, 2001 |

Excluded based on TiAb |

|

Watson, 2009 |

Excluded by Sathianathen 2018, search up to June 2017 |

|

Wu, 2020 |

Wrong design: case control |

|

Xu, 2017 |

Excluded based on TiAb |

|

Xu, 2019 |

Wrong comparison: urine bladder patients with hematuria patients. |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 29-08-2023

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-05-2023

Voor het beoordelen van de actualiteit van deze richtlijn is de werkgroep niet in stand gehouden. Uiterlijk in 2028 bepaalt het bestuur van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Urologie of de modules van deze richtlijn nog actueel zijn. Op modulair niveau is een onderhoudsplan beschreven. Bij het opstellen van de richtlijn heeft de werkgroep per module een inschatting gemaakt over de maximale termijn waarop herbeoordeling moet plaatsvinden en eventuele aandachtspunten geformuleerd die van belang zijn bij een toekomstige herziening (update). De geldigheid van de richtlijn komt eerder te vervallen indien nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding zijn een herzieningstraject te starten.

De Nederlandse Vereniging voor Urologie is regiehouder van deze richtlijn en eerstverantwoordelijke op het gebied van de actualiteitsbeoordeling van de richtlijn. De andere aan deze richtlijn deelnemende wetenschappelijke verenigingen of gebruikers van de richtlijn delen de verantwoordelijkheid en informeren de regiehouder over relevante ontwikkelingen binnen hun vakgebied.

Algemene gegevens

De richtlijnontwikkeling werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.kennisinstituut.nl) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijn.

Algemene gegevens

De Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en Leven met Blaas- of Nierkanker hebben de richtlijn goedgekeurd.

Aanleiding voor het maken van de richtlijn

In dit project zal de huidige richtlijn Hematurie worden herzien. De huidige richtlijn is verjaard

(2010) en voldoet niet aan de methodologische kwaliteitseisen van Richtlijnen 2.0.

Doel van de richtlijn

Het doel is het herzien van de richtlijn dat patiëntenzorg voor patiënten met hematurie beschrijft. Deze herziening richt zich op modules over de optimale diagnostiek en daaropvolgend ook beleid te bewerkstelligen bij patiënten die zich bij de uroloog presenteren met hematurie en het terugdringen van praktijkvariatie en onnodige kosten om de juiste onderliggende oorzaak van hematurie te vinden. De richtlijnmodules leveren een heldere beslisboom en patiënteninformatie op waardoor behandelaars de juiste diagnostiek kunnen inzetten voor de patiënt met hematurie.

Afbakening van de richtlijn

De aard en omvang

Deze richtlijn bespreekt onder meer de diagnostiek die nodig is om een maligniteit aan te tonen dan wel uit te sluiten. In deze richtlijn wordt aandacht besteed aan zowel de diagnostiek van macroscopische als microscopische hematurie.

Beoogde gebruikers van de richtlijn

De richtlijn is bedoeld voor met name urologen, maar ook aanpalende disciplines die met de diagnostiek van hematurie te maken hebben, zoals radiologen, nefrologen en klinisch chemici.

Doel en doelgroep

Het doel is het herzien van de richtlijn dat patiëntenzorg voor patiënten met hematurie beschrijft. Deze herziening richt zich op modules over de optimale diagnostiek en daaropvolgend ook beleid te bewerkstelligen bij patiënten die zich bij de uroloog presenteren met hematurie en het terugdringen van praktijkvariatie en onnodige kosten om de juiste onderliggende oorzaak van hematurie te vinden. De richtlijnmodules leveren een heldere beslisboom en patiënteninformatie op waardoor behandelaars de juiste diagnostiek kunnen inzetten voor de patiënt met hematurie.

Beoogde gebruikers van de richtlijn

De richtlijn is met name bedoeld voor urologen. Voor de volgende disciplines is het ook waardevol om kennis te nemen van de richtlijn: huisartsen, radiologen, internisten, nefrologen en klinisch chemici.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijn is in 2020 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met hematurie. De werkgroep leden zijn door hun beroepsverenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname. De werkgroep is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze richtlijn.

Werkgroep

- Drs. M.C. (Marina) Hovius, uroloog, OLVG, NVU (voorzitter)

- Dr. P.W. (Paul) Veenboer, uroloog, Ommelander Ziekenhuis Groningen en UMCG, NVU

- Dr. L.S. (Laura) Mertens, uroloog, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Ziekenhuis, NVU

- Dr. B.P. (Bart) Schrier, uroloog, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, NVU

- Dr. A.H. (Arnold) Boonstra, internist-nefroloog, Flevoziekenhuis Almere, NIV

- Dr. A.Y. (Ayşe) Demir, klinisch chemicus, Meander Medisch Centrum Amersfoort, NVKC

- Dr. E.M. (Eelco) Fennema, heelkunde, UMC Groningen, NVvH (tot mei 2022)

- Drs. S. (Saskia) Kolkman, radioloog, Amsterdam UMC, NVvR (tot mei 2021)

- Drs. B. (Bram) Westerink, radioloog, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Ziekenhuis, NVvR (vanaf mei 2021)

Namens patiëntenvereniging Leven met blaas- of nierkanker

- Dr. H. (Hans) Ubbels, patiëntenvereniging Leven met blaas- of nierkanker (tot mei 2021)

- Drs. E. (Else) Wolak, NFK

Klankbordgroep

- Dr. C.F. La Chapelle, urogynaecoloog, Elkerliek ziekenhuis (tot januari 2023) daarna Viecuri, NVOG

- Dr. M.E. (Mariëlle) Donker, gynaecoloog, Diaconessen Ziekenhuis Utrecht, NVOG

- Dr. J.G. (Iris) Ketel, NHG

- Drs. A.J. (Aart) van der Molen, radioloog, LUMC, NVvR

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. I.M. (Irina) Mostovaya, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. J.H. (Hanneke) van der Lee, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De KNMG-code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroep leden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement, kennisvalorisatie) hebben gehad. Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroep leden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

|

Achternaam werkgroeplid |

Hoofdfunctie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen |

Persoonlijke relaties |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek |

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie |

Overige belangen |

Getekend op |

Actie |

|

* Voorzitter werkgroep Hovius |

Uroloog, OLVG Amsterdam |

Lid kwaliteitsvisitatie NVU (onkostenvergoeding) |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

04/07/2020 |

Geen restrictie |

|

Demir |

Klinisch Chemicus, Meander MC, Amersfoort |

Voorzitter FMS-NVKC Richtlijn Eenduidige en accurate laboratoriumdiagnostiek bij bloed in urine (hematurie) (vacatiegelden) Medisch Coördinator voor de eerstelijn, Meander MC (betaald) Vakdeskundige Raad voor Accreditatie (betaald) |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

15/04/2020 |

Geen restrictie |

|

Mertens |

Uroloog, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Ziekenhuis |

Deelname werkgroep Europese richtlijn spierinvasief en gemetastaseerd blaascarcinoom |

Nee |

Nee |

Nee |

Nee |

nvt |

26/06/2020 |

Geen restrictie |

|

Schrier |

Uroloog, opleider Urologie JBZ |

Proctor robotchirurgie (begeleidt onervaren urologen bij opstarten robotchirurgie) |

geen |

Nee |

geen |

geen |

geen |

28/06/2020 |

Geen restrictie |

|

Ubbels |

Patientenvereniging Leven met blaas- of nierkanker |

Vrijwilliger, niet betaald |

geen |

Nee |

geen |

geen |

geen |

24/07/2020 |

Geen restrictie |

|

Veenboer |

Uroloog, Ommelander Ziekenhuis Groningen (0,6 FTE) en UMCG (0,2 FTE) |

Redactielid Urograaf |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

In 2019 eenmalig vergoeding ontvangen van Sanofi voor EAU review van nieuwe chirurgische behandelingen voor BPH, in 2019 eenmalig vergoeding van Astra Zeneca voor congresbezoek. |

02/07/2020 |

Geen restrictie |

|

Boonstra |

Internist-nefroloog in het Flevoziekenhuis te Almere |

Principal Investigator voor Fidelio en Figaro studie, internationale multicenter trial bij diabetes mellitus patiënten met nefropathie, met betaald |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

23/06/2020 |

Geen restrictie (Genoemde onderzoeken hebben geen relatie met de diagnostiek van hematurie) |

|

Wolak |

Projectleider Patientenorganisatie Leven met blaas- of nierkanker, neem in deze hoedanigheid deel aan de werkgroep (16 uur). Projectleider kwaliteit van zorg NFK (16 uur) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Werkzaam bij patiëntenorganisatie, geen boegbeeldfunctie. |

Nee |

11/09/2020 |

Geen restrictie |

|

Kolkman |

Radioloog, 80% aanstelling |

Screeningsradioloog voor het BOB-MW (bevolkingsonderzoek borstkanker), betaald omvang 1 dagdeel per week |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

nee |

18/09/2020 |

Geen restrictie |

|

Westerink |

Radioloog, Antoni Van Leeuwenhoek Ziekenhuis - Nederlands Kanker Instituut |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

07/11/2022 |

Geen restrictie |

|

Fennema |

Traumachirurg, UMCG |

Geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

nee |

28/10/2020 |

Geen restrictie |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Klankbordgroep |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ketel |

Wetenschappelijk medewerker NHG Utrecht, Kaderhuisarts Urogynaecologie Zorroo Oosterhout, waarnemend huisarts regio Eindhoven |

deelname werkgroep richtlijn herziening PCOS, FMS kennisinstituut, betaald |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

31/08/2020 |

Geen restrictie |

|

van der Molen |

Radioloog, LUMC Leiden |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

In afgelopen 3 jaar consultancy fees ontvangen van Guerbet; ging over publicatie over contrastmiddelen veiligheid (contrast nefropathie preventie) |

24/07/2020 |

Geen restrictie |

|

Donker |

Urogynaecoloog, Diakonessenhuis Utrecht |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

14/11/2022 |

Geen restrictie |

|

La Chapelle |

Urogynaecoloog, Viecuri, Venlo |

geen |

nee |

nee |

nee |

nee |

nee |

18/09/2020 |

Geen restrictie |

|

Adviseurs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mostovaya |

Senior adviseur Kennisinstituut FMS |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

|

|

Van der Lee |

Senior adviseur Kennisinstituut FMS |

Onderzoeker Amsterdam UMC (0,05 FTE) |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

|

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiënten perspectief door een afgevaardigde van Leven met blaas- of nierkanker. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan Leven met blaas- of nierkanker en de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst kwalitatieve raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Instructies voor urineverzameling |

geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft, het geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners betreft en het geen wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module Urinesediment na urinestrip analyse |

geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft, het geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners betreft en het geen wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module De rol van urine biomarkers bij de diagnostiek van hematurie |

geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft, het geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners betreft en het geen wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module Cystoscopie bij vrouwen met microscopische hematurie |

geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module Radiologische diagnostiek van hematurie |

geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module Nefrologische / urologische oorzaken van hematurie |

geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module Herevaluatie na negatieve analyse bij hematurie |

geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module Hematurie en antistolling |

geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module Organisatie van zorg |

geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft, het geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners betreft en het geen wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Implementatie

In de verschillende fasen van de richtlijnontwikkeling is rekening gehouden met de implementatie van de richtlijn (module) en de praktische uitvoerbaarheid van de aanbevelingen. Daarbij is uitdrukkelijk gelet op factoren die de invoering van de richtlijn in de praktijk kunnen bevorderen of belemmeren. Het implementatieplan is te vinden in Module 7 Organisatie van zorg. De werkgroep heeft besloten geen indicatoren te ontwikkelen bij de huidige richtlijn, om de registratielast niet toe te laten nemen.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijn is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010), dat een internationaal breed geaccepteerd instrument is. Voor een stap-voor-stap beschrijving hoe een evidence-based richtlijn tot stand komt wordt verwezen naar het stappenplan Ontwikkeling van Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Knelpuntenanalyse

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerden de voorzitter van de werkgroep en de adviseur de knelpunten. Tevens werden stakeholders uitgenodigd voor een knelpuntenbijeenkomst (Invitational conference). Het verslag van de Invitational Conference bevindt zich in de bijlage.

De werkgroep stelde vervolgens een long list met knelpunten op en prioriteerde de knelpunten op basis van: (1) klinische relevantie, (2) de beschikbaarheid van (nieuwe) evidence van hoge kwaliteit, (3) en de te verwachten impact op de kwaliteit van zorg, patiëntveiligheid en (macro)kosten.

Uitgangsvragen en uitkomstmaten

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de voorzitter en de adviseur concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld. Deze zijn met de werkgroep besproken waarna de werkgroep de definitieve uitgangsvragen heeft vastgesteld. Er was financiële ruimte om 8 uitgangsvragen uit te werken met een systematische literatuursearch. Daarom moest de werkgroep een prioritering maken van de relevante klinische knelpunten. Vervolgens inventariseerde de werkgroep per uitgangsvraag welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur

Er werd voor de afzonderlijke uitgangsvragen zoekvragen geformuleerd. Zoekvragen werden vertaald naar PICO’s (Patient, Intervention, Control, Outcome). Aan de hand van specifieke zoektermen gezocht naar gepubliceerde wetenschappelijke studies in (verschillende) elektronische databases. Tevens werd aanvullend gezocht naar studies aan de hand van de literatuurlijsten van de geselecteerde artikelen. In eerste instantie werd gezocht naar studies met de hoogste mate van bewijs. De werkgroep leden selecteerden de via de zoekactie gevonden artikelen op basis van vooraf opgestelde selectiecriteria. De geselecteerde artikelen werden gebruikt om de uitgangsvraag te beantwoorden. De databases waarin is gezocht, de zoekstrategie en de gehanteerde selectiecriteria zijn te vinden in de module met desbetreffende uitgangsvraag. De zoekstrategie voor de oriënterende zoekactie en patiënten perspectief zijn opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Kwaliteitsbeoordeling individuele studies

Individuele studies werden systematisch beoordeeld, op basis van op voorhand opgestelde methodologische kwaliteitscriteria, om zo het risico op vertekende studieresultaten (risk of bias) te kunnen inschatten. Deze beoordelingen kunt u vinden in de Risk of Bias (RoB) tabellen. De gebruikte RoB instrumenten zijn gevalideerde instrumenten die worden aanbevolen door de Cochrane Collaboration: AMSTAR - voor systematische reviews; Cochrane - voor gerandomiseerd gecontroleerd onderzoek; Newcastle-Ottawa - voor observationeel onderzoek; QUADAS II - voor diagnostisch onderzoek.

Samenvatten van de literatuur

De relevante onderzoeksgegevens van alle geselecteerde artikelen werden overzichtelijk weergegeven in evidence-tabellen. De belangrijkste bevindingen uit de literatuur werden beschreven in de samenvatting van de literatuur. Bij een voldoende aantal studies en overeenkomstigheid (homogeniteit) tussen de studies werden de gegevens ook kwantitatief samengevat (meta-analyse) met behulp van Review Manager 5.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

A) Voor interventievragen (vragen over therapie of screening)

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie (Schünemann, 2013).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk* |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

*in 2017 heeft het Dutch GRADE Network bepaald dat de voorkeursformulering voor de op een na hoogste gradering ‘redelijk’ is in plaats van ‘matig’

B) Voor vragen over diagnostische tests, schade of bijwerkingen, etiologie en prognose

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd eveneens bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode: GRADE-diagnostiek voor diagnostische vragen (Schünemann, 2008), en een generieke GRADE-methode voor vragen over schade of bijwerkingen, etiologie en prognose. In de gehanteerde generieke GRADE-methode werden de basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek toegepast: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van bewijskracht op basis van de vijf GRADE-criteria (startpunt hoog; downgraden voor risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias).

Formuleren van de conclusies

Voor elke relevante uitkomstmaat werd het wetenschappelijk bewijs samengevat in een of meerdere literatuurconclusies waarbij het niveau van bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methodiek. De werkgroep leden maakten de balans op van elke interventie (algehele conclusie). Bij het opmaken van de balans werden de gunstige en ongunstige effecten voor de patiënt afgewogen. De overall bewijskracht wordt bepaald door de laagste bewijskracht gevonden bij een van de cruciale uitkomstmaten. Bij complexe besluitvorming waarin naast de conclusies uit de systematische literatuuranalyse vele aanvullende argumenten (overwegingen) een rol spelen, werd afgezien van een algehele conclusie. In dat geval werden de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de interventies samen met alle aanvullende argumenten gewogen onder het kopje Overwegingen.

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals de expertise van de werkgroep leden, de waarden en voorkeuren van de patiënt (patient values and preferences), kosten, beschikbaarheid van voorzieningen en organisatorische zaken. Deze aspecten worden, voor zover geen onderdeel van de literatuursamenvatting, vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje Overwegingen.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk. De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten samen.

Randvoorwaarden (Organisatie van zorg)

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijn is expliciet rekening gehouden met de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, menskracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van een specifieke uitgangsvraag maken onderdeel uit van de overwegingen bij de bewuste uitgangsvraag. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van Zorg.

Indicatorontwikkeling

Gelijktijdig met het ontwikkelen van de conceptrichtlijn heeft de werkgroep overwogen om interne kwaliteitsindicatoren te ontwikkelen om het toepassen van de richtlijn in de praktijk te volgen en te versterken. Meer informatie over de methode van indicatorontwikkeling is op te vragen bij het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten. De werkgroep heeft besloten geen indicatoren te ontwikkelen bij de huidige richtlijn om de registratielast niet toe te laten nemen.

Kennislacunes

Tijdens de ontwikkeling van deze richtlijn is systematisch gezocht naar onderzoek waarvan de resultaten bijdragen aan een antwoord op de uitgangsvragen. Bij elke uitgangsvraag is door de werkgroep nagegaan of er (aanvullend) wetenschappelijk onderzoek gewenst is om de uitgangsvraag te kunnen beantwoorden. Een overzicht van de onderwerpen waarvoor (aanvullend) wetenschappelijk van belang wordt geacht, is als aanbeveling in de bijlage Kennislacunes beschreven (onder aanverwante producten).

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijn werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijn aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijn werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Brouwers, M. C., Kho, M. E., Browman, G. P., Burgers, J. S., Cluzeau, F., Feder, G., ... & Littlejohns, P. (2010). AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 182(18), E839-E842.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/werkwijze/richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Ontwikkeling van Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen: stappenplan. Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html.

Schünemann, H. J., Oxman, A. D., Brozek, J., Glasziou, P., Jaeschke, R., Vist, G. E., ... & Bossuyt, P. (2008). Rating Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations: GRADE: Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 336(7653), 1106.

Wessels, M., Hielkema, L., & van der Weijden, T. (2016). How to identify existing literature on patients' knowledge, views, and values: the development of a validated search filter. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 104(4), 320.

Zoekverantwoording

Literature search strategy

|

Richtlijn: Hematurie |

|

|

Uitgangsvraag: Wat is de rol van de urinemarkertest ADX bladder (MCM5 ELISA test) bij de diagnostiek van hematurie? |

|

|

Database(s): Embase, Medline |

Datum: 28-9-2020 |

|

Periode: 2000 – September 2020 |

Talen: Engels |

|

Literatuurspecialist: Miriam van der Maten |

|

|

Toelichting en opmerkingen:

|

|

Zoekopbrengst

|

|

Embase |

OVID/MEDLINE |

Ontdubbeld |

|

SRs |

16 |

44 |

50 |

|

RCT |

67 |

105 |

132 |

|

Observationeel |

138 |

258 |

301 |

|

Totaal |

221 |

407 |

483 |

Zoekverantwoording

|

Database |

Zoektermen |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Embase

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medline (OVID) |

1 exp *Hematuria/ or hematuria.ti,ab,kf. or haematuria.ti,ab,kf. or erythrocyturia.ti,ab,kf. or macrohaematuria.ti,ab,kf. or macrohematuria.ti,ab,kf. (23068) 2 exp Biomarkers/ or biomarker*.ti,ab,kf. or ((biological or urinary or urine) adj2 marker*).ti,ab,kf. or exp "Nuclear Matrix-Associated Proteins"/ or 'nuclear matrix protein 22'.ti,ab,kf. or nmp22.ti,ab,kf. or 'nmp 22'.ti,ab,kf. or adxbladder.ti,ab,kf. or 'minichromosome maintenance protein 5'.ti,ab,kf. or mcm5.ti,ab,kf. or exp "Receptor, Fibroblast Growth Factor, Type 3"/ or 'fibroblast growth factor receptor 3'.ti,ab,kf. or fgfr3.ti,ab,kf. or 'fgfr 3'.ti,ab,kf. or tert.ti,ab,kf. or (telomerase adj2 transcriptase).ti,ab,kf. or exp Microsatellite Repeats/ or microsatellite*.ti,ab,kf. or exp MicroRNAs/ or 'microRNA'.ti,ab,kf. or miRNA.ti,ab,kf. or 'micro rna'.ti,ab,kf. or (urinary adj2 (transcriptome or proteomics or 'methylation')).ti,ab,kf. or 'bladder tumor antigen'.ti,ab,kf. or (urine adj2 'dna test').ti,ab,kf. (1090122) 3 1 and 2 (1176) 4 limit 3 to (english language and yr="2000 -Current") (860) 5 (meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (meta adj analy$).tw. or ((systematic* or literature) adj2 review$1).tw. or (systematic adj overview$1).tw. or exp "Review Literature as Topic"/ or cochrane.ab. or cochrane.jw. or embase.ab. or medline.ab. or (psychlit or psyclit).ab. or (cinahl or cinhal).ab. or cancerlit.ab. or ((selection criteria or data extraction).ab. and "review"/)) not (Comment/ or Editorial/ or Letter/ or (animals/ not humans/)) (467426) 6 (exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or random*.ti,ab. or (clinic* adj trial*).tw. or ((singl* or doubl* or treb* or tripl*) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo*.tw.) not (animals/ not humans/) (2030655) 7 Epidemiologic studies/ or case control studies/ or exp cohort studies/ or Controlled Before-After Studies/ or Case control.tw. or (cohort adj (study or studies)).tw. or Cohort analy$.tw. or (Follow up adj (study or studies)).tw. or (observational adj (study or studies)).tw. or Longitudinal.tw. or Retrospective*.tw. or prospective*.tw. or consecutive*.tw. or Cross sectional.tw. or Cross-sectional studies/ or historically controlled study/ or interrupted time series analysis/ [Onder exp cohort studies vallen ook longitudinale, prospectieve en retrospectieve studies] (3530082) 8 4 and 5 (44) 9 (4 and 6) not 8 (105) 10 (4 and 7) not (8 or 9) (258) 11 8 or 9 or 10 (407) |