Conservatieve behandeling bij hallux valgus

Uitgangsvraag

Welke conservatieve behandeling(en) van hallux valgus heeft/hebben de voorkeur?

Aanbeveling

Beschouw oefentherapie, inzet van steunzolen/inlays, ortheses, schoenaanpassingen en (semi-) orthopedisch schoenen als complementaire conservatieve therapieën en stel in overleg met de patiënt een behandelplan op dat aansluit bij de specifieke hulpvraag.

Geef bij voorkeur iedere patiënt met een hallux valgus een schoenadvies.

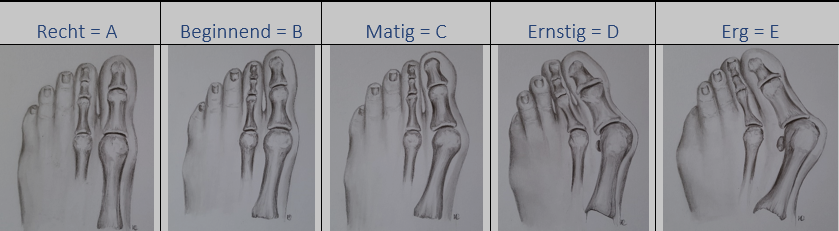

Overweeg om de Manchester Scale bij conservatieve therapie te gebruiken als meetinstrument om de mate van scheefstand van de hallux valgus te bepalen.

Overweeg oefentherapie bij patiënten met een hallux valgus met Manchester Scale categorie B en C.

Overweeg steunzolen/inlays met als doel pijnvermindering in te zetten bij patiënten waarbij intrinsieke factoren in de voet meespelen zoals pronatie en/of hypermobiliteit.

Overweeg bij patiënten met bijkomende bewegingsgerelateerde pijnklachten in MTP-I (niet door artrose), schoenaanpassingen van confectieschoenen of (semi-)orthopedische schoenen ter ontlasting van het MTP-I gewricht.

Overweeg bij patiënten met een hallux valgus en kissing lesions de inzet van interdigitale siliconen orthese om irritatie van de huid en pijn te verminderen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de effectiviteit van conservatieve behandeling van hallux valgus. Verschillende soorten interventies werden beschreven in gerandomiseerd en observationeel onderzoek. Door het veelal ontbreken van klinisch relevante verschillen en de lage tot zeer lage bewijskracht van de gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten ten gevolge van beperkingen in de studieopzet en kleine patiëntaantallen, kon op basis van de literatuur geen duidelijke voorkeur uitgesproken worden voor een van de interventies. Er is hier sprake van een kennislacune. Er is meer gerandomiseerd onderzoek nodig. De aanbevelingen zullen daarom gebaseerd worden op aanvullende argumenten waaronder expert opinion, waar mogelijk onderbouwd met (indirecte) literatuur.

Er lijkt geen voordeel te zijn voor behandeling van milde tot matige hallux valgus met een orthese vergeleken met standaardzorg (eeltverwijdering en verstrekking van geschikte schoenen). Wel lijkt er op basis van voetfunctie een lichte voorkeur te zijn voor een mobilisatie programma als behandeling van milde tot matige hallux valgus vergeleken met placebo of een nachtspalk. Het is door de zeer lage bewijskracht onduidelijk of gecombineerde behandeling bestaande uit mobilisatie, oefeningen en een orthese beter is dan standaardzorg bij symptomatische matige hallux valgus.

De werkgroep is van mening dat conservatieve behandeling in iedere fase van hallux valgus klachten kan worden ingezet. In een vroege fase van hallux valgus klachten kan een behandeling met mobiliserende oefentherapie gestart worden, ondersteund met steunzolen/inlays. In een later stadium is conservatieve therapie meer gericht op standsoptimalisering, afwikkelcompensatie, vermindering van mobiliteit tot volledige immobilisatie en voorkomen van secundaire klachten. Ook postoperatief kan conservatieve therapie worden ingezet ter ondersteuning van het revalidatietraject of indien restklachten zijn ontstaan zoals overmatige druk onder MTP-II, -III, of -IV, afhankelijk van de hulpvraag.

Inzet van conservatieve behandeling

De aanwezigheid van hallux valgus kan leiden tot een hulpvraag. De hulpvraag kan bestaan uit een esthetisch probleem, ongerustheid over het beloop, pijnklachten die deelname aan dagelijks leven belemmeren of schoenpasproblemen. Het is een uitdaging om (de combinatie van) behandelmethoden te kiezen die het best aansluit bij de hulpvraag van de patiënt en de mogelijkheden passend bij de hallux valgus afwijking.

De onderstaande vormen van conservatieve behandeling zijn in Nederland de meest gebruikte. In de beschrijving van de verschillende therapievormen zijn waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten opgenomen.

- Oefentherapie.

- Steunzolen/inlays.

- Ortheses.

- Schoenadvies.

- Schoenaanpassingen.

- (semi-)orthopedische schoenen.

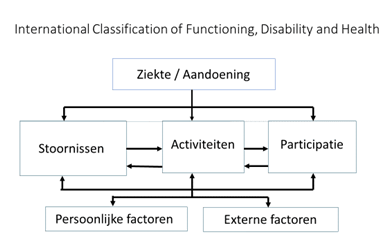

Om tot de juiste conservatieve behandeling te komen wordt geïnventariseerd wat de invloed is van de hallux valgus op de gezondheidstoestand van de patiënt in brede zin. Hiervoor is de wisselwerking tussen verschillende factoren van belang. Om de invloed van deze verschillende factoren te kwalificeren op de gezondheidstoestand van de patiënt wordt het International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model gehanteerd, zoals weergegeven in figuur 1.

Figuur 1. ICF model

Functies en anatomische eigenschappen

Hieronder vallen mate van de scheefstand en functionaliteit van het MTP-I gewricht

De volgende schalen worden hiervoor gebruikt:

1. De mate van scheefstand wordt bepaald aan de hand van de Manchester Scale. Veelal wordt de mate van de hallux valgus op basis van een röntgenfoto’s vastgesteld. Indien de patiënt komt op verwijzing van de specialist of de huisarts is het röntgenologisch verslag op te vragen bij de verwijzer. Indien de patiënt gebruik maakt van directe toegankelijkheid van de aanbieder van conservatieve therapie is er in de regel geen röntgenologisch verslag. De Manchester scale wordt dan gebruikt voor het beschrijven van de mate van scheefstand.

Figuur 2. Manchester Scale

Bron: Kennis- en Opleidingscentrum van Voet, Houding en Beweging

Garrow (2001) ontwikkelde de Manchester Scale met categorieën. Roddy (2007) heeft de Manchester Scale iets aangepast, waarbij ten opzichte van een rechte hallux in elke categorie de valgus hoek met 15° toeneemt. Dit leidt tot 5 categorieën, zoals weergegeven in figuur 2.

2. Pijnbeleving middels de VAS- of NRS score. Deze scores worden gebruikt als een meetinstrument om voor-, tijdens en na afloop van een behandeltraject het resultaat van de behandeling inzichtelijk te maken. Dit geldt zowel voor pijn in de hallux als voor pijn elders in het lichaam.

3. Voetfunctie middels de FPI. De Foot Posture Index (FPI) bepaalt de stand van de achtervoet en de stand van de voorvoet. Met FPI wordt de voet gekwalificeerd als een normale, een geproneerde of een gesupineerde voet.

Om inzicht te krijgen in de ontwikkeling van de voetfunctie tijdens het behandeltraject kan de Foot Function Index worden toegepast.

De FFI-5pt is de Nederlandse versie van de Foot Function Index (FFI) en meet de gevolgen van voetklachten op het dagelijks functioneren in de afgelopen week.

De vragenlijst bestaat uit vijftien multiple choice vragen, verdeeld over de subcategorieën pijn en moeite met activiteiten.

Activiteiten

Activiteiten zijn onderdelen van iemands handelen zoals wandelen, traplopen. Bij de conservatieve behandeling zal geïnventariseerd worden in hoeverre de patiënt problemen ondervindt bij deze activiteiten.

Participatie

In de beschrijving van de beperkingen op participatie niveau wordt aangegeven in hoeverre de patiënt door de hallux valgus beperkt wordt in deelname aan het maatschappelijk leven. Denk hierbij aan werken, zelfverzorging, dagelijkse zaken als boodschappen doen, sport en vrije tijdsbesteding.

Externe factoren

Bij het maken van een keuze tussen de (conservatieve) behandelingen is het belangrijk om te weten welke factoren die buiten de patiënt zelf gelegen zijn een rol spelen. Deze factoren kunnen gelegen zijn in de thuissituatie of de werksituatie. Financiële omstandigheden, angst voor orthopedische schoenen en/of weerstand vanuit de omgeving kunnen factoren zijn die mede bepalend voor de keuze van een behandeling.

Persoonlijke factoren

Persoonlijke factoren kunnen van invloed zijn op de therapiekeuze in de (conservatieve) behandeling. Zo draagt bijvoorbeeld weerstand bij de patiënt op de tijdsinvestering en fysieke inspanning van oefentherapie bij aan lage therapietrouw en vermoedelijk lage effectiviteit. Ook kan mogelijk weerstand op schoenaanpassingen of aanschaf van andere schoenen, die voor inzet van steunzolen noodzakelijk kunnen zijn, de effectiviteit van de behandeling beïnvloeden. Het is daarom belangrijk om bij de therapiekeuze rekening te houden met persoonlijke factoren.

Hulpvraag

De hulpvraag wordt in overleg met de patiënt vastgesteld. De hulpvraag is niet alleen bepalend voor het vaststellen van het beoogde behandeldoel maar wordt ook gebruikt bij de evaluatie van het behandeltraject.

Evaluatie van behandeling

Ondanks het gebrek aan wetenschappelijk bewijs is het aannemelijk dat conservatief behandelen positief resultaat geeft.

Behandelaars schrijven individuele resultaten toe aan de toegepaste therapie. Maar wetenschappelijk onderzoek heeft tot nu toe niet geleid tot overtuigend objectief bewijs hiervoor.

Het is in dit kader aan te raden deze bij een individueel behandeltraject de geboekte resultaten nauwkeurig te monitoren.

Het resultaat van de behandeling wordt geëvalueerd aan de hand van de gekozen meetinstrumenten en vastgesteld wordt of het behandeldoel is behaald.

De hulpvraag is bepalend voor het vaststellen van het beoogde behandeldoel.

Patiënttevredenheid

De patiënttevredenheid wordt gemeten Patient Reported Outcome Measures, de PROMs, die kunnen verschillen tussen de betreffende vakgebieden en de gekozen therapie.

Met de PROMs vragenlijst wordt informatie ingewonnen over het dagelijks functioneren, pijn, mobiliteit en kwaliteit van leven. Dit wordt gekoppeld aan de klinimetrie van het ICF-model.

Conservatieve behandelmethoden

Behandeltraject

Er zijn in Nederland diverse behandelvormen beschikbaar. De systematische literatuuranalyse kon geen richting geven aan de besluitvorming.

Om een passend behandelplan op te stellen is de hulpvraag het uitgangspunt. De behandelaar dient inzicht te hebben in de verschillende behandelmethodes en de eigen grenzen en mogelijkheden kennen.

De hulpvraag geeft een verhelderende omschrijving van de contactreden van de patiënt die een oplossing zoekt voor zijn/haar functioneringsprobleem.

Voor de behandeling wordt gewerkt met het Rehabilitation Problem Solving formulier (het RPS-formulier), dit formulier is gebaseerd op het ICF-model. In het RPS formulier wordt de gezondheidstoestand vastgelegd vanuit het standpunt van de patiënt en van de behandelaar.

Het RPS formulier is belangrijk om het resultaat van de interventie te objectiveren.

Oefentherapie

Bij patiënten met een milde hallux valgus (Manchester Scale B en C) die gemotiveerd zijn voor oefentherapie dient dit overwogen te worden. De oefentherapie is gericht op het opheffen van de beperkingen in het MTP-I gewricht en de gehele eerste straal. De therapie bestaat uit manuele therapie, tractie en mobilisatie en gerichte spierversterkende oefeningen. Proprioceptieve training is een onderdeel van de behandeling om de sensomotorische functie te herstellen of te verbeteren.

Bij oefentherapie voor de hallux valgus kan ook de rest van het lichaam onderdeel zijn van de screening en de behandeling.

Het doel van de oefentherapie is verbeteren van het activiteiten- en participatieniveau van de patiënt door oefentherapie voor de voet en de houding.

Oefentherapie vraagt van de patiënt een actieve rol. Therapietrouw is noodzakelijk voor het bereiken van het uiteindelijke resultaat.

Steunzolen/inlays

Steunzolen en inlays kunnen in iedere fase van de hallux valgus worden ingezet indien de voetstand of voetfunctie afwijkend is. Steunzool, inlay of voetbed zijn dezelfde benamingen voor een op maat gemaakte zool die in een confectieschoen past. Het doel van de steunzool is het verbeteren van de stand in het MTP-I gewricht, waardoor de functie en de afwikkeling van de voet verbeteren. Elementen die middels het toepassen van een steunzool te beïnvloeden zijn, zijn onder andere de mate van valgisering in de midvoet, het doorzakken van de voorvoet en de extensie in het MTP-I gewricht. Daarnaast kan de steunzool de druk herverdelen bij transfer metatarsalgie. De persoonlijke voorkeur van de patiënt in het dragen van een bepaald schoentype heeft invloed op de mogelijkheid om steunzolen/inlays te kunnen toepassen. Het inzetten van steunzolen/inlays dient altijd gepaard te gaan met een schoenadvies. Het toepassen van steunzolen/inlays wordt door de patiënten ervaren als makkelijk toepasbaar.

Schoenadvies

Schoenadvies is in alle fasen van hallux valgus geïndiceerd. Het is gericht op het geven van adviezen voor wat betreft de pasvorm en de functionaliteit van de schoen. Voor pasvorm is het belangrijk dat de lengte en breedte van de schoen overeenkomen met de voet. Daarnaast is het belangrijk dat er geen stiksels in de schacht over de bunion lopen en dat de schacht gemaakt is van zacht materiaal dat indien nodig opgerekt kan worden. Voor de functionaliteit van de schoenen is het belangrijk dat de hakhoogte niet te hoog is. Een dikke zool en eventueel een stijve zool maken het afwikkelen van de voet minder belastend voor het MTP-I gewricht. Een gericht schoenadvies is een individueel afhankelijke interventie, waarop diverse factoren van invloed zijn. De behandelaar dient deze factoren voldoende in kaart te hebben gebracht of hiervoor door te verwijzen. Kennis van het aanbod van confectieschoenen vergemakkelijkt het geven van advies. Indien men twijfelt of er nog passend confectieschoeisel te vinden is, kan de orthopedisch schoentechnoloog advies geven.

Orthese

Veel voorkomende secundaire problematiek bij de hallux valgus is het ontstaan van kissing lesions als gevolg van hyperpressie door een standsverandering van de hallux. Het toepassen van een siliconen teenorthese die individueel vervaardigd wordt, kan verlichting van klachten bieden door protectie van de huid, kan de stand van tenen beïnvloeden en stabilisatie geven. Het verdient aandacht dat de siliconen orthese niet te veel ruimte vraagt in de schoen. Het is een zeer toegankelijk en goedkope therapie die snel te vervaardigen is.

Schoenaanpassingen

Schoenaanpassingen gericht op pasvormproblemen

Het heeft de voorkeur de patiënt zelf op basis van een goed advies schoenen te laten kopen.

Indien een patiënt op basis van het schoenadvies toch pasvormproblemen blijft houden kan het aanpassen van de schoenen de pasvorm verder optimaliseren. Het aanpassen van de pasvorm van de schoen heeft als doel het verminderen van de druk op de bunion en voorkomen van drukplekken, eeltvorming, likdoorns, wonden en slijmbeursontsteking. Afhankelijk van de mate van vervorming van de voet kan bij een milde vervorming worden volstaan met het oprekken van de bestaande confectieschoenen. Bij forse hallux valgus deformatie (Manchester Scale C, D en E) en indien de patiënt geen passend schoeisel kan vinden is het laten aanmeten van (semi-)orthopedische schoenen geïndiceerd. Het aanbod van (semi-) orthopedische schoenen sluit goed aan op het modebeeld en wordt door patiënten positief ervaren, echter blijft het keuzeaanbod beperkt en is het aantal schoenen dat vergoed wordt vanuit de verzekering gelimiteerd. Het voordeel is dat het inzetten van (semi-)orthopedische schoenen zonder risico is, het is niet onomkeerbaar en de patiënt heeft snel resultaat.

Schoenaanpassingen gericht op verminderde beweging van het MTP-I gewricht

Er zijn twee situaties waarin een schoenaanpassing toegepast kan worden. Ten eerste wanneer er sprake is van pijn bij bewegen dient overwogen te worden of er sprake is van artrose van het MTP-I gewricht bij de hallux valgus. Wanneer de oorzaak van de pijn uitsluitend gelegen is in de afwijkende stand kan er middels een schoenaanpassing gezocht worden naar pijnreductie. Ten tweede als er sprake is van een verminderde bewegelijkheid in MTP-I waardoor het maken van een afwikkeling van de voet beperkt is.

Voorbeelden hiervan zijn een afwikkelvoorziening (Rocker bottom) en een zoolverstijving. De aanpassingen worden gemaakt in de zool (het onderwerk) van de schoen en zijn onlosmakelijk verbonden aan de schoen. Deze aanpassing kan zowel in confectieschoenen (Orthopedische Voorziening aan Confectie, OVAC) als in (semi-)orthopedische schoenen worden toegepast.

Indien bovenstaande behandeltrajecten gevolgd worden is het mogelijk dat door de diverse beroepsgroepen die zich bezighouden met de conservatieve behandeling uniformiteit komt in onderzoek en behandeling. Uiteindelijk zullen de data op deze manier verkregen leiden tot een Practice Based Evidence (PBE). Op deze manier kan bepaald worden welke resultaten tot de beste behandelresultaten leiden bij de diverse categorieën hallux valgus. Een goede interdisciplinaire samenwerking tussen de beroepsgroepen die zich bezighouden met de conservatieve behandeling is een voorwaarde voor het uiteindelijke resultaat.

Aandachtspunten bij diabetes mellitus en reumatoïde artritis

Wanneer er sprake is van complicaties bij diabetes mellitus of reumatoïde artritis bestaat de mogelijkheid dat de patiënt hierdoor afhankelijk zal blijven van conservatieve therapieën. De behandeling kan bestaan uit steunzolen/inlays en eventueel (semi-)orthopedische schoenen.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Alle beschreven behandelmethoden zijn in Nederland algemeen aanvaard. Er zijn geen belemmerende factoren voor het toepassen van de beschreven behandelingen.

Belangrijk is dat de patiënt doorverwezen wordt naar een professional met een brede ervaring in voetproblematieken. Zowel voor het toepassen van oefentherapie als het toepassen van steunzolen/inlays en schoenaanpassingen dient dit te gebeuren door een behandelaar die gespecialiseerd is in voetklachten, een brede kennis heeft en bekend is met de relatie voet- en houdingsklachten. Daarnaast is het belangrijk dat de conservatieve behandelaar laagdrempelig contact kan zoeken met de medisch specialist om direct overleg over complexe pathologie te kunnen voeren en adequaat te kunnen verwijzen.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Bij de keuze voor een conservatieve therapie is het van belang de invloed van de hallux valgus in een breed kader te beoordelen.

Het wordt aanbevolen hierbij het ICF-model te hanteren. Het is van belang dat eerst duidelijk in kaart gebracht wordt welke doelen de patiënt stelt met de behandeling zodat het behandelplan aansluit bij de specifieke hulpvraag van de patiënt.

Het is een complex samenspel van velerlei factoren die de keuze voor een bepaalde therapievorm bepalen. Ook een combinatie van verschillende therapie vormen is mogelijk.

Wetenschappelijk onderzoek verschaft ons geen houvast om aanbevelingen te doen welke therapievorm het meest geschikt is. Op basis van expert opinion zijn de volgende aanbevelingen geformuleerd.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Bij een hallux valgus heeft het in de meeste gevallen de voorkeur om een behandeling te starten met een conservatieve therapie. Er zijn diverse conservatieve behandelingen van hallux valgus mogelijk. De behandelingen variëren van actieve manipulaties tot passieve mobilisaties en spierversterkende trainingen, het inzetten van siliconen teenortheses en steunzolen/inlays tot het geven van schoenadviezen, het aanpassen van bestaande schoenen, en het aanmeten van semi-orthopedische schoenen en orthopedische schoenen. Professionals die zich hiermee bezig houden zijn onder andere (gespecialiseerde) fysiotherapeuten, podotherapeuten, registerpodologen en orthopedisch schoentechnologen. Het is wetenschappelijk niet aangetoond welke therapie het meest effectief is voor de behandeling van de hallux valgus wanneer het gaat om pijnreductie, standsverbetering, functie van het MTP-I gewricht en patiënttevredenheid.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Orthoses versus standard care

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with foot orthoses does not seem to reduce pain compared to usual care (callus removal and provision of low-heel shoes with a wide-and-deep toe box) or no treatment in patients with mild to moderate hallux valgus.

Sources: (Torkki, 2001; Torkki, 2003) |

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with foot orthoses does not seem to improve foot function compared to no treatment in patients with mild to moderate hallux valgus.

Sources: (Torkki, 2001) |

|

- GRADE |

It was not possible to draw conclusions or grade the level of evidence for the outcome valgus deformity correction due to lack of data. |

|

- GRADE |

It was not possible to draw conclusions or grade the level of evidence for the outcome patient satisfaction due to lack of data. |

Functional orthoses versus night splint

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether treatment with functional orthoses reduces pain compared to a night splint in patients with mild to moderate hallux valgus.

Sources: (Tehraninasr, 2008) |

- GRADE |

It was not possible to draw conclusions or grade the level of evidence for the outcome foot function due to the absence of comparative studies reporting the outcome. |

|

- GRADE |

It was not possible to draw conclusions or grade the level of evidence for the outcome valgus deformity correction due to the absence of comparative studies reporting the outcome. |

|

- GRADE |

It was not possible to draw conclusions or grade the level of evidence for the outcome patient satisfaction due to the absence of comparative studies reporting the outcome. |

Mobilisation versus night splint/placebo

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether mobilisation interventions reduce pain compared to treatment with a night splint in patients with mild to moderate hallux valgus.

Sources: (Du Plessis, 2011) |

|

Low GRADE |

Mobilisation interventions may improve foot function compared to treatment with a night splint or placebo in patients with mild to moderate hallux valgus.

Bronnen: (Brantingham, 2005; Du Plessis, 2011) |

|

- GRADE |

It was not possible to draw conclusions or grade the level of evidence for the outcome valgus deformity correction due to the absence of comparative studies reporting the outcome. |

|

- GRADE |

It was not possible to draw conclusions or grade the level of evidence for the outcome patient satisfaction due to the absence of comparative studies reporting the outcome. |

Multicomponent interventions

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether multi-component interventions reduce pain compared to no treatment in patients with symptomatic moderate hallux valgus.

Sources: (Abdalbary, 2018.) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether multicomponent interventions improve foot function compared to no treatment in patients with symptomatic moderate hallux valgus.

Bronnen: (Abdalbary, 2018.) |

|

- GRADE |

It was not possible to draw conclusions or grade the level of evidence for the outcome valgus deformity correction due to lack of data. |

|

- GRADE |

It was not possible to draw conclusions or grade the level of evidence for the outcome patient satisfaction due to the absence of comparative studies reporting the outcome. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

The RCT by Abdalbary (2018) compared outcomes of treatment with a silicone toe separator in combination with foot joint mobilization, strengthening exercises for hallux plantar flexion and abduction, toe grip strength, and stretching of ankle dorsiflexion versus no treatment in patients with symptomatic moderate hallux valgus. Fifty-six woman were randomized into two equal groups. Reported outcomes were pain, foot function, and correction of deformity. Five patients in the treatment group and six in the control group were lost at one year follow-up.

Torkki (2001 and 2003) were randomized controlled trials that compared 209 patients with a painful bunion and mild to moderate hallux valgus with the hallux valgus angle 35° or less and the intermetatarsal angle of 15° or less. Patients were randomized into one year waiting for operation either with or without orthoses. Outcomes of interest in the studies were pain, foot problems, satisfaction, and health-related quality of life. The length of follow-up of orthosis versus watchful waiting was one year.

In a non-randomized comparative study, Tehraninasr (2008), compared treatment with a semi-rigid insole and toe separator with a night splint in 30 female patients with mild to moderate bilateral hallux valgus with a painful bunion and a hallux valgus angle of 35° or less and an intermetatarsal angle of 15° or less. Intensity of foot pain, correction of deformity were evaluated at final follow-up at three months. None of the patients were lost to follow-up.

In the RCT of Du Plessis (2011) 30 patients, who were randomized in two equally distributed groups, were treated with either the structured Brantingham protocol of manual and manipulative therapy or a night splint. All eligible participants were diagnosed with symptomatic mild to moderate hallux valgus. Pain, foot function, and range of motion at one month follow-up were the outcomes of interest in the study. None of the patients were lost to follow-up.

The pilot RCT by Brantingham (2005) compared a conservative chiropractic approach involving progressive mobilization, adjustment and cryotherapy (the Brantingham protocol) with a placebo in the treatment of symptomatic mild to moderate hallux abductovalgus bunion with a hallux valgus/abductus angle greater than 15° and an intermetatarsal angle greater than 9°. The study included 60 patients and reported outcomes regarding pain and foot function at three weeks follow-up. No patients were lost to follow-up.

Results

Orthoses versus standard care

Pain (critical outcome measure)

Pain was assessed in two studies (Torkki, 2001 and Torkki, 2003). Length of follow-up in these studies varied from one month to two years.

The studies of Torkki (2001; 2003) reported pain on the Visual Analog Scale (0 to 100) for treatment with an orthoses versus no orthoses after respectively 6, 12 and 24 months. At 6 months, the mean (SD) pain score for the orthoses group was 36 (24) versus 45 (23) for the control group. The pain score at one year follow-up slightly increased to a mean score of 40 (23) for the orthoses group and decreased for the control group to a pain score of 40 (26). Differences at six months and one year follow-up between the groups were not considered to be clinically relevant differences. Follow-up pain scores at two years were not relevant, since the majority of the patients underwent surgery and the results are no longer related to orthosis treatment.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain comes from randomized controlled trials and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of the limited number of patients in the studies (imprecision) and limitations in study design (lack of blinding of patients and physicians, risk of bias). This resulted in a level of evidence of low.

Foot function (critical outcome measure)

Functional status of the foot was measured in one study (Torkki, 2001). Length of follow-up was one year. The study measured foot function with the AOFAS hallux scale. Torkki (2001) reported a mean (SD) score of 64 (10) after one year follow-up versus a score of 66 (10) for the control group. This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure foot function comes from randomized controlled trials and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of the limited population size (imprecision) and limitations in study design (lack of blinding of patients and physicians, risk of bias). This resulted in a low level of evidence.

Valgus deformity correction

Not reported.

Patient satisfaction

Not reported.

Functional orthoses versus night splint

Pain (critical outcome measure)

One study (Tehraninasr, 2008) measured pain on the VAS in mild to moderate hallux valgus comparing a rigid insole and toe separator versus a night splint after three months.

The mean (SD) baseline score of the insole group was 42.6 (14.8) and decreased to 26.6 (13.4) at the three months follow-up. In the night splint group, the mean (SD) baseline was 41.3 (17.8) and did slightly decrease after three months follow-up to 40.0 (11.3). The mean difference between the two groups was 14.7 mm, which is considered a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain comes from an observational study and therefore starts low. The level of evidence was downgraded because of the limited population size (imprecision), resulting in a level of evidence of very low.

Foot function (critical outcome measure)

Not reported.

Valgus deformity correction

Not reported.

Patient satisfaction

Not reported.

Mobilization versus night splint/placebo

Pain (critical outcome measure)

One study (Du Plessis, 2011) measured pain in symptomatic mild to moderate hallux valgus after the treatment of either mobilization versus a night splint. The study measured pain after one and after four weeks after the treatment of either mobilization or a night splint. At baseline, the night splint group reported a VAS-score of 37.55 (95% CI: 30 to 45), which decreased after one week to 5.1 (95% CI: 0 to 12) and increased after four weeks to 17.7 (95% CI:10 to 24). The mobilization group had a baseline VAS-score of 40.7 (95% CI: 30 to 53), the score decreased to 1.2 (95% CI: 0 to 3) and remained the same at four weeks. The mobilization group found a clinically relevant difference in VAS-score between baseline and four weeks follow-up of 39.5. In the night splint group, this clinically relevant difference is 19.85. However, due to unavailability of data it was not possible to determine if these differences were statistically significant. After one week there was no significant decrease in pain between the two groups, while after four weeks this difference was clinically and statistically significant favoring the mobilization group (16.5 (95% CI: 9 to24) p<0.01).

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain comes from randomized controlled trials and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of very limited population size (imprecision) and one level due to limitations in study design (risk of bias). Therefore, the level of evidence was very low.

Foot function (critical outcome measure)

The studies of Du Plessis (2011) and Brantingham (2005) reported outcomes on the Foot Function Index (FFI) one week after the last appointment (Brantingham, 2005) and after one and four weeks (Du Plessis, 2011). In addition, Brantingham (2005) also reported outcomes on the AOFAS hallux scale.

The FFI between the mobilization group and night splint group in the study of Du Plessis (2011) was measured after one and four weeks. Baseline FFI-score in the night splint group was 63.8 (95% CI: 53 to 74), after one week it was 9.2 (CI: 0 to 20), and after four weeks the final score was 32.4 (CI: 19 to 45). In the mobilization group, the FFI-score was 51.8 (CI: 36 to 67) at baseline, 1.7 (CI: 0 to 5) at one week follow-up, and 2.3 (CI: 0 to 6) at four weeks follow-up. After one week, no statistically significant difference in FFI-scores was observed between the groups. At four weeks follow-up there was a clinically relevant difference favoring the mobilization group (30 (CI: 16 to 44).

Brantingham (2005) reported different FFI-subscales in the results; the FFI-pain score, FFI-function score, and the FFI-total score. A significant difference was found for every subscale (in exception for baseline and FFI-function score for treatment one and two) in favor of the mobilization group (p<0.05).

In all subscales, a clinically relevant difference was found between the mobilization and placebo group. Differences in FFI-scores between baseline and one week follow-up for the mobilization group was: FFI-pain 39.93; FFI-function 41.33; FFI-total 40.52. For the placebo group the scores were: FFI-pain 1.75; FFI-function 1.26; FFI-total 1.38. Score differences between these two groups were 38.18; 40.07; 39.14 favoring the mobilization group.

Besides the FFI, Brantingham (2005) also reported outcomes on the AOFAS hallux scale. A statistically significant improvement was found at after every treatment with a mean total AOFAS-score improvement from 38.57 to 82.30. The placebo group showed significant improvements between baseline and the third treatment; between baseline and the sixth treatment and between baseline and one week follow-up. No statistically significant improvements between treatment three and six; treatment three and one week follow-up and treatment six and one week follow-up was reported. Despite the significant improvement, the mean total AOFAS-score improvement was only 6.94 out of the maximum of 100 points (from 42.43 to 49.37). It was noted that 26 out of 30 patients in the placebo group changed the pain score regularly per measurement. A reasonable explanation for this observation was that the patients might felt the need for giving the desired answers. Also, having a mandatory lifestyle could have affected changes that applied throughout the study, such as not wearing high heels with a tapered nose. The increase in mean total score was 43.73 in the mobilization group versus 6.94 in the placebo group, a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure foot function comes from randomized controlled trials and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two limitations in study design (risk of bias) and limited population size (imprecision). This resulted in a low level of evidence.

Valgus deformity correction

Not reported.

Patient satisfaction

Not reported.

Multicomponent interventions

Pain (critical outcome measure)

The study of Abdalbary (2018) measured pain in symptomatic moderate hallux valgus on the VAS-scale (range 0 to 10) before and after treatment (24 treatment sessions) and after one year follow-up. The multicomponent group (n = 28) reported a mean (SD) baseline score of 5.6 (1.0), which decreased after one year to a mean score of 2.4 (1.0). The mean (SD) of the control group was 5.2 (1.3) at baseline and 5.9 (1.3) after one year follow-up. The mean difference in pain score after one year between the groups was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure foot function comes from a randomized controlled trial and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of the very limited population size (imprecision), and by one level because of limitations in study design (risk of bias), resulting in a very low level of evidence.

Foot function (critical outcome measure)

Foot function after multicomponent treatment with a silicon toe separator in combination with mobilisation versus no treatment (Abdalbary, 2018) resulted in a mean (SD) AOFAS score of 74.5 (2.0) for the study group and 43 (1.7) in the control group, which is considered a clinically relevant difference. At baseline, participants in the study group had a mean of 46.1 (1.4) in the study group and 45 (1.7) in the control group.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure foot function comes from a randomized controlled trial and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of the very limited population size, and by one level because of limitations in study design (risk of bias), resulting in a very low level of evidence.

Valgus deformity correction

In the included literature, the ratio of patients that achieved valgus deformity correction was not described. Correction of deformity of the hallux valgus angle was measured in one study (Abdalbary, 2018) between the multicomponent treatment group and the no treatment group. The multicomponent group had a mean (SD) baseline score of 32.7 (4.2) and improved to 25.8 (2.1) at one year follow-up. The no treatment group did not improve, with a hallux valgus angle of 31.9 (3.2) at baseline and 32.9 (3.2) at one year follow-up.

Level of evidence of the literature

For the outcome correction of deformity, the level of evidence could not be determined due to lack of data.

Patient satisfaction

Not reported.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the (dis)advantages of the different conservative interventions for patients with hallux valgus?

P: patients with hallux valgus;

I: conservative treatment;

C: compared to other conservative treatment or standard care;

O: pain, foot function, valgus deformity correction, patient satisfaction.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered pain and foot function as critical outcomes for decision making; and valgus deformity correction and patient satisfaction as important outcomes for decision making.

A priori, the working group defined valgus deformity correction as a dichotomous outcome, whether or not postoperative HVA < 15° and IMA < 9° were obtained. The working group did not define the other outcomes listed above but followed the definitions used in the studies. The working group defined 25% as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for dichotomous outcomes, 0.5 SD for standardized mean differences (SMD), 15% of the maximum score for pain (VAS) and 10% of the maximum score for function (AOFAS).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID), CINAHL (via Ebsco) and Cochrane were searched until 2015 for systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and other comparative study designs comparing any two (or more) conservative treatments of hallux valgus or comparing conservative treatment with standard care. Five studies were included. The search was updated in February 26, 2020, limiting the results to new systematic reviews and RCTs. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search update resulted in 65 new hits. Seven studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, five studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and two studies were included.

Results

Six RCTs and one observational study were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Abdalbary SA. Foot Mobilization and Exercise Program Combined with Toe Separator Improves Outcomes in Women with Moderate Hallux Valgus at 1-Year Follow-up A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2018 Nov;108(6):478-486. doi: 10.7547/17-026. Epub 2018 Apr 23. PMID: 29683337.

- Brantingham JW, Guiry S, Kretzmann HH, Kite VJ, Globe G. A pilot study of the efficacy of a conservative chiropractic protocol using graded mobilization, manipulation and ice in the treatment of symptomatic hallux abductovalgus bunion. Clinical Chiropractic 2005;8(3):117-33.

- du Plessis M, Zipfel B, Brantingham JW, Parkin-Smith GF, Birdsey P, Globe G, Cassa TK. Manual and manipulative therapy compared to night splint for symptomatic hallux abducto valgus: an exploratory randomised clinical trial. Foot (Edinb). 2011 Jun;21(2):71-8. doi: 10.1016/j.foot.2010.11.006. Epub 2011 Jan 14. PMID: 21237635.

- Garrow AP, Papageorgiou A, Silman AJ, Thomas E, Jayson MI, Macfarlane GJ. The grading of hallux valgus. The Manchester Scale. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2001 Feb;91(2):74-8. doi: 10.7547/87507315-91-2-74. PMID: 11266481.

- Menz HB, Roddy E, Thomas E, Croft PR. Impact of hallux valgus severity on general and foot-specific health-related quality of life. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011 Mar;63(3):396-404. doi: 10.1002/acr.20396. Epub 2010 Nov 15. PMID: 21080349.

- Roddy E, Zhang W, Doherty M. Validation of a self-report instrument for assessment of hallux valgus. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007 Sep;15(9):1008-12. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.02.016. Epub 2007 Mar 26. PMID: 17387024.

- Shih KS, Chien HL, Lu TW, Chang CF, Kuo CC. Gait changes in individuals with bilateral hallux valgus reduce first metatarsophalangeal loading but increase knee abductor moments. Gait Posture. 2014;40(1):38-42. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2014.02.011. Epub 2014 Feb 26. PMID: 24637011.

- Steinberg N, Finestone A, Noff M, Zeev A, Dar G. Relationship between lower extremity alignment and hallux valgus in women. Foot Ankle Int. 2013 Jun;34(6):824-31. doi: 10.1177/1071100713478407. Epub 2013 Mar 4. PMID: 23460668.

- Torkki M, Malmivaara A, Seitsalo S, Hoikka V, Laippala P, Paavolainen P. Hallux valgus: immediate operation versus 1 year of waiting with or without orthoses: a randomized controlled trial of 209 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003 Apr;74(2):209-15. doi: 10.1080/00016470310013987. PMID: 12807332.

- Torkki M, Malmivaara A, Seitsalo S, Hoikka V, Laippala P, Paavolainen P. Surgery versus orthosis versus watchful waiting for hallux valgus: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001 May 16;285(19):2474-80. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2474. PMID: 11368700.

- Tehraninasr A, Saeedi H, Forogh B, Bahramizadeh M, Keyhani MR. Effects of insole with toe-separator and night splint on patients with painful hallux valgus: a comparative study. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2008 Mar;32(1):79-83. doi: 10.1080/03093640701669074. PMID: 18330806.

- Chadchavalpanichaya N, Prakotmongkol V, Polhan N, Rayothee P, Seng-Iad S. Effectiveness of the custom-mold room temperature vulcanizing silicone toe separator on hallux valgus: A prospective, randomized single-blinded controlled trial. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2018 Apr;42(2):163-170. doi: 10.1177/0309364617698518. Epub 2017 Mar 20. PMID: 28318407.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for intervention studies

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Abdalbary, 2018 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Single centre, Egypt

Funding and conflicts of interest: None reported |

Inclusion criteria: Women with a diagnosis of symptomatic moderate hallux valgus

Exclusion criteria: Previous foot surgery, underlying ankle deformity or pathologic hindfoot or midfoot deformities, or any deformity of the hallux other than valgus deformity. Patients with systemic pathologic disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis and gout were also excluded. Patients who were using anti-inflammatory drugs or analgesics or in whommanual therapy was contraindicated were excluded.13 Pregnant women were excluded because plain film radiography is contraindicated during pregnancy

N total at baseline: Intervention: 28 Control: 28

Important prognostic factors: For example age ± SD: I: 45.7 ± 6.8 C: 45.5 ± 6.2

Sex: I: 100% F C: 100% F

Groups comparable at baseline? yes |

The treatment group wore a toe separator made of silicon material (Voberry, Spain). The patients were required to wear the toe separator for more than 8 hours per day. The physical therapy program consisted of three sessions per week for 12 weeks and mobilisations

|

The control group were asked to avoid surgical and foot orthotic therapy during follow-up, and they did not receive the intervention, so that the natural course of the condition could be determined |

Length of follow-up:

1 year

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: none N = 0 (0%) Reasons (describe)

Control: none N = 0 (0%) Reasons (describe)

|

Pain (VAS 0-10) Mean ± SD

Baseline Treatment: 5.6 ± 1.0 Control: 5.2 ± 1.3

After 1 year follow-up Treatment: 2.4 1.0 Control: 5.9 ± 1.3 P < 0.001

Foot function (AOFAS) Mean ± SD

Baseline Treatment: 46.1 ± 1.4 Control: 45. ± 1.7

After 1 year follow-up Treatment: 74.5 ± 2.0 Control: 43 ± 1.7 P < 0.001

Corrected deformity angle: HVA angle Mean ± SD

Baseline Treatment: 32.7 ± 4.2 Control: 31.9 ± 3.2

After 1 year follow-up Treatment: 25.8 ± 2.1 Control: 32.9 ± 3.2 P < 0.001

Corrected deformity angle: First-second intermetatarsal angle (FIA)

Outcome reported in mean ± SD

Baseline Treatment: 14.0 (1.0) Control: 14.0 (0.9)

After 1 year follow-up Treatment: 12.0 ± 0.9 Control: 15.0 ± 0.9 P < 0.001 |

|

|

Torkki, 2001 |

Type of study: RCT Setting and country: conducted in 4 general community hospitals in Finland in 1997-1998 Source of funding: no |

Inclusion criteria: A painful bunion with the hallux valgus angle 35° or less and the intermetatarsal angle of 15° or less.

Exclusion criteria: Any foot that had previously undergone bunion surgery, Hallux rigidus, Hallux limitus, Rheumatoid disease, use of functional foot ortheses, pregnancy, Age older than 60 years.

N total at baseline: Ntotal= 209 I1: n= 71 I2: n= 69 C: n= 69 Aged (SD) years I1: 48 (10) I2: 49 (10) C: 47 (9) Sex: I1: 93% female I2: 89% female C: 96% female

Intensity of foot pain at baseline: Mean (SD) I2: 50 (23) C: 45 (24)

AOFAS HMIS at baseline: Mean (SD) I2: 59 (11) C: 62 (11)

Groups comparable at baseline? yes |

1: immediate operation 2: 1 year waiting with foot orthoses |

3: 1 year waiting without foot orthoses

|

1 year follow-up

Loss-to-follow-up: 4 patients (2%)

I1: N=0 I2: N= 1 (0.5%) C: N= 3 (1.4%) Reasons (describe): not reported

Incomplete outcome data after 1 year: I1: N=0 I2: N= 1 (0.5%) C: N= 3 (1.4%) Reasons (describe): not reported

The dropouts did not differ markedly from those remaining in the study.

|

total number of operated patients After 1 year follow-up I1: 66\71 (n=2, cancelled operation due to a work conflict, n=1 pregnant, n= 1 severe depression, n=1 refused of personal reasons) I2: 0\69 C: 4\69 (n=4 because of severe foot pain )

Intensity of foot pain (VAS) after 6 month: Mean (SD) I2: 36 (24) C: 45 (23) MD I2, C: -14 (-22 to -6);

Foot function index (FFI) after 6 month: not reported

AOFAS HMIS after 6 month: not reported

Intensity of foot pain (VAS) after 12 month: Mean SD) I2: 40 (23) C: 40 (26) MD I2, C: -6 (-15 to 3);

Foot function index (FFI) after 12 month: not reported

AOFAS HMIS after 12 month: Mean (SD) I2: 64 (10) C: 66 (10) MD I2, C: 0 (-4 to 5); |

|

|

Torkki, 2003 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: conducted in 4 general community hospitals in Finland in 1997-1999

Source of funding: no |

Inclusion criteria: See Torkki, 2001

Exclusion criteria: See Torkki, 2001 .

N total at baseline: See Torkki., 2001

Intensity of foot pain at baseline: Mean (SD) I2: 50 (23) C: 45 (24)

AOFAS HMIS at baseline: Mean (SD) I2: 59 (11) C: 62 (11)

Groups comparable at baseline? yes

|

1: immediate operation 2: 1 year waiting with foot orthoses |

3: 1 year waiting without foot orthoses

After 1 year, the patients in the orthosis and control groups were offered surgery. |

At 1 year follow-up Loss-to-follow-up: 4 patients (2%)

I1: N=0 I2: N= 3 (1.4%) C: N= 1 (0.5%)

At 2 year follow-up Loss-to-follow-up: 12 patients (6%)

I1: N=3 (1.4%) I2: N= 3 (1.4%) C: N= 6 (2.8%)

The dropouts did not differ markedly from the remaining subjects as a whole, or between the 3 intervention groups.

|

total number of operated patients after 1 year follow-up See Torkki et al., 2001

after 2 year follow-up I1: 68\71 I2: 43\69 C: 48\69

Intensity of foot pain (VAS) after 6 month and 12 month: See Torkki et al., 2001

Foot function index (FFI) after 6 month and 12 month: See Torkki et al., 2001

AOFAS HMIS after 6 month and 12 month: See Torkki et al., 2001

Intensity of foot pain (VAS) after 24 month: Mean (SD) I2: 16 (17) C: 19 (22) MD I2, C: -9 (-18 to 1);

Foot function index (FFI) after 24 month: not reported

AOFAS HMIS after 24 month: not reported |

|

|

Tehraninasr, 2008 |

Type of study: Randomized study with convenience samples

Setting: University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences

Country: Iran

Source of funding: not mentioned |

Inclusion criteria: having a painful bunion and the hallux valgus angle 35° or less and the intermetatarsal angle of 15° or less , mild to moderate bilateral flexible hallux valgus.

Exclusion criteria: Any foot that had previously undergone bunion surgery, had hallux rigidus, hallux limitus was excluded in the study, age younger than 19 or older than 45 years, previous use of foot orthoses, rheumatoid disease, and pregnancy.

N total at baseline: N= 30 Age (mean ±SD) 27 ± 8.91 Sex: 30 females and 0 males

Groups comparable at baseline? Not described |

semi-rigid insole and toe separator |

Night splint |

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: not mentioned

|

Pain (VAS, 0-10, converted to 0-100)): Before I: 42.6±14.8 C: 41.3±17.8 After I: 26.6±13.4 C: 40.0±11.3 (p<0.05)

Foot function index (FFI) : not reported

AOFAS HMIS: not reported

|

|

|

Du Plessis, 2011 |

Type of study: Pragmatic exploratory randomised clinical trial

Setting: chiropractic outpatient teaching clinic of the University of Johannesburg.

Country: South Africa.

Source of funding: This research was designed, funded and completed in 2005 as partial fulfillment of a Masters in Technology: Chiropractic in the Department of Chiropractic, University of Johannesburg (UJ), South Africa, Cleveland Chiropractic College appreciates the opportunity to collaborate with the UJ and publish this data.

|

Inclusion criteria: pain and reduced function of the first metatarsophalangeal joint (≥30%); enlarged medial portion of the first metatarsal head; inability to wear shoes comfortably; mild, moderate or severe lateral deviation of the hallux from the mid-saggital plane as per Lorimer et al. ; radiological evidence of an HAVangle greater than 15 degrees and inter-metatarsal angle greater than 9 degrees as per Reid; age range between 26 and 64 years.

Exclusion criteria: systemic or local pathology, for example inflammatory arthritis or severe osteoarthritis; where manual or manipulative therapy was contraindicated, for example joint instability or intolerance to manual therapy; regular, continued use of narrow pointed high-heeled shoes as this would likely result in different outcomes. Participants were advised to discontinue wearing such shoes during the course of this study and beyond; pregnant woman, since plain-film X-rays are contraindicated; patients younger than 25 years and older than 65 years.

N total at baseline: N= 30 I: n= 15 C: n= 15

Average age: 42 years (range 25–65) Sex: equal distribution

Pain (VAS) at baseline:% (CI) C: 37.55 (30–45) I: 40.7 (30–53) MD: 3 (0–15) P: 0.48

FFI at baseline:% (CI) C: 63.8 (53–74) I: 51.8 (36–67) MD: 12 (0–24) P: 0.09

Groups comparable at baseline? There was a significant difference between baseline data sets between the two groups for the outcome disability (FFI), accounted for by ANCOVA analysis. |

mobilization involving the Brantingham protocol

1)Graded joint mobilisation of the 1st MTPJ, ranging from grades 1 to 4 2) Joint manipulation, usually grade 5 high velocity, low amplitude, controlled thrust (HVLA). 3) All treatments are initially followed by post-treatment cold therapy using ice to decrease the possibility of side effects. 4) Mobilisation/manipulation of other foot and ankle joints

maximum of 4 treatments over 2 weeks |

night splint

which holds the great toe in an adducted or corrected position |

The treatment period for both groups was 2 weeks, with follow-up at 1-week and at 1-month.

Loss-to-follow-up; there were no exclusions or dropouts over the duration of the study and no data was missing. |

Pain (VAS): % (CI) At 1 week FU C: 5.1 (0–12) I: 1.2 (0–3) MD: 4(0–11) P: 0.35 At 1 month FU C: 17.7 (10–24) I: 1.2 (0–3) MD: 16.5 (9–24) P: <0.01

Foot function index (FFI) : % (CI) At 1 week FU C: 9.2 (0–20) I: 1.7 (0–5) MD: 7.5 (0–21) P: 0.19 At 1 month FU C: 32.4 (19–45) I: 2.3 (0–6) MD: 30 (16–44) P: <0.01

AOFAS HMIS: not reported

|

|

|

Brantingham, 2005 |

Type of study: a prospective, randomized clinical trial

Setting: chiropractic outpatient teaching clinic of the University of Johannesburg.

Country: South Africa.

Source of funding: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria: Radiological examination; Hallux valgus/abductus angle greater than 15°; Intermetatarsal angle greater than 9°; Enlarged medial portion of the first metatarsal Head; Mild, moderate or severe lateral deviation of the hallux from the mid-sagittal plane; Pain around the first MPJ; Inability to wear shoes comfortably; Females >18 years of age.

Exclusion criteria: Any patients with systemic or local pathology, for example rheumatoid arthritis or gout; The use of anti-inflammatory drugs or analgesics; The use of tight, narrow pointed high-heeled shoes, as Reid is of the opinion that this type of shoe nullifies any therapeutic benefit derived from conservative care; Any contra-indication to manipulation; Patients who have had Action Potential Therapy or manipulation of the first MPJ.

N total at baseline: N= 60 I: n= 30 C: n= 30

Average age: I: 49.43 years C: 50.86 years

Sex: only female

FFI at baseline: Mean (SD) FFpain I: 55.23 (16.91) P: 0.343 C: 59.93 (14.51) CI: -3.44 to 12.84 FFdis I: 53.31 (22.04) P: 0.264 C: 48.33 (17.69) CI: -15.31 to 5.35 FFtot I: 56.13 (17.06) P :0.464 C: 54.16 (13.42) CI: -9.90 to 5.96

HMIS at baseline: Mean (SD) I: 38.57 (11.17) P: 0.115 C: 42.43 (7.07) CI:- 0.97 to 8.69

|

conservative chiropractic approach involving progressive mobilization, adjustment and cryotherapy (the Brantingham protocol)

|

Placebo

Action Potential Therapy (a physical therapy modality which passed no current) was ‘‘administered’’ to the foot by means of self-adhesive pads that could, on application, cause some degree of cutaneous stimulation. |

Total of six treatments over a two-week period and were re-examined one week after their last appointment

|

Pain (VAS): Not reported

Foot function index (FFI) at third treatment : Mean (SD) FFIpain I: 33.03 (19.50) P: 0.000 C: 56.11 (18.71) CI: 13.20—32.96 FFIdis I: 30.26 (21.88) P: 0.004 C: 46.19 (16.61) CI: 5.89—25.97 FFItot I: 31.94 (19.51) P: 0.000 C:51.05 (16.76) CI: 9.71—28.51

Foot function index (FFI) at the sixth consultation: Mean (SD) FFIpain I: 19.27 (18.37) P: 0.000 C: 58.42 (19.06) CI: 29.48—48.82 FFIdis I: 16.19 (17.19) P: 0.000 C: 44.67 (18.07) CI: 19.37—37.59 FFI tot I: 17.82 16.74 P: 0.000 C: 51.56 (16.77) CI: 25.08—42.40

Foot function index (FFI) at the one-week follow-up: Mean (SD) FFI pain I: 15.30 (19.33) P: 0.000 C: 58.18 (18.05) CI: 33.21—52.55 FFI dis I: 11.98 (14.09) P: 0.000 C: 47.07 (21.32) CI: 25.75—44.43 FFI tot I: 15.61 (19.32) P: 0.000 C: 52.78 (18.02) CI: 27.51—46.83

AOFAS HMIS at third treatment Mean (SD) I: 61.47 (7.32) P: 0.000 C: 46.30 (6.81) CI: -8.82 to -11.52

AOFAS HMIS at the sixth consultation Mean (SD) I: 76.53 (7.12) P: 0.000 C: 48.83 (6.62) CI:-31.25 to -24.15

AOFAS HMIS at the one-week follow-up Mean (SD) I: 82.30 (5.28) P: 0.000 C: 49.37 (5.89) CI: -35.82 to -30.04 |

|

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

Research question: What are the (dis)advantages of the different conservative interventions for patients with hallux valgus?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Abdalbary, 2018 |

Based on a list of numbers in a random number table using numbered sealed envelopes |

Likely |

Likely |

Unlikely

|

Unlikely

|

Unlikely |

Unlikely

No loss to follow-up |

Unlikely |

|

Tehraninasr, 2008 |

Not specified. |

Likely |

Likely |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

Torkki, 2001 |

Based on a list of numbers in a random number table using numbered sealed envelopes |

Likely |

Likely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Torkki, 2003 |

Based on a list of numbers in a random number table using numbered sealed envelopes |

Likely |

Likely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Du Plessis, 2011 |

using a manual non-algorithmic process where pieces of paper with group allocation written on them were folded over and concealed and drawn randomly by the participating patients themselves. |

Likely |

Likely |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Brantingh, 2005 |

60 slips of paper (30 slips with group A (intervention) and 30 slips with group B (controle) written on them) were placed in a bag and randomly drawn out by patients at the initial consultation. |

Likely |

Likely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Moulodi, 2019 |

No comparison of interventions relevant for the Dutch clinical setting |

|

Waizy, 2019 |

Review, no meta-analysis |

|

Fraser, 2019 |

Healthy population |

|

Glasoe, 2016 |

No comparative study |

|

Mortka, 2015 |

Review, no meta-analysis |

|

Chadchavalpanichaya, 2017 |

Intervention not in line with PICO |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 08-10-2021

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 29-07-2021

Algemene gegevens

De herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

De richtlijn is ontwikkeld in samenwerking met:

- Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap voor Fysiotherapie

- Stichting Landelijk Overkoepelend Orgaan voor de Podologie

- Nederlandse Vereniging van Podotherapeuten

- NVOS-Orthobanda

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Anesthesiologie

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Radiologie

- ReumaNederland

- Patiëntenfederatie Nederland

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met een hallux valgus.

Werkgroep

- Drs. W.P. Metsaars, orthopedisch chirurg bij Annatommie MC (voorzitter), NOV

- Dr. I.V. van Dalen, orthopedisch chirurg in de Bergman Kliniek, NOV

- Dr. M.A. Witlox, orthopedisch chirurg in MUMC, NOV

- Drs. S.B. Keizer, orthopedisch chirurg in Haaglanden MC, NOV

- C.J.C.M. Hoogeveen, podoposturaal therapeut bij Praktijk voor Podoposturale Therapie, KNGF en Stichting LOOP

- A.P. van Dam, orthopedisch schoentechnoloog bij Graas Company, NVOS-Orthobanda

- S.C.C. Scheepens, podotherapeut bij Scheepens en Klijsen Podotherapie, NVvP

- N. Lopuhaä, beleidsmedewerker Patiëntbelangen, ReumaNederland

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. S. Persoon, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. M.S. Ruiter, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Metsaars (voorzitter) |

Orthopedisch chirurg, voet en enkel, Annatommie MC |

Penningmeester Dutch Foot & Ankle Society: onbetaald, verrichten expertises, DC expertise centrum: betaald. |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Scheepens |

Podotherapeut/eigenaar 30-40u/wk Scheepens en Vijsen Podotherapie |

Externe beoordelaar Fontys Hogeschool opleiding podotherapie betaald 2 x halve dag per jaar; |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van Dalen |

Orthopedisch chirurg, voet en enkel, Bergmanclinics te Naarden fulltime |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Lopuhaä |

Beleidsmedewerker Patientenbelangen ReumaNederland |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Hoogeveen |

Werkzaam als podoposturaal therapeut in eigen praktijk - de Praktijk voor Podoposturale Therapie- in Nieuwegein (1,5 dag per week) met als achtergrond fysiotherapeut, manueel therapeut (Niet praktiserend)

Mede eigenaar van Kennis- en Opleidingsinstituut voor Voet, Houding en Beweging (3 dagen per week) - functie ontwikkelaar van oefenprotocollen voor de voet en opleiding voetentrainer voor fysio- en oefentherapeuten. |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Keizer |

Orthopedisch Chirurg, Haaglanden MC. |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van Dam |

Orthopedisch Schoentechnoloog en directeur/eigenaar bij Graas Orthopedische Schoentechniek voor 38 uur per week |

Vicevoorzitter van NVOS-Orthobanda, branchevereniging voor zorgondernemers in orthopedische hulpmiddelen, onbetaalde functie. Voorzitter van Stichting Thuishuis Woerden, zet zich in tegen eenzaamheid onder ouderen in Woerden, onbetaalde functie. |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Witlox |

Orthopedisch Chirurg, MUMC+ |

Bestuur WKO, niet betaald Penningmeester oudervereniging OBS Maastricht, niet betaald |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Persoon |

Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Ruiter |

Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntperspectief door Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en andere relevante patiëntenorganisaties uit te nodigen voor de Invitational conference. Het verslag hiervan (zie bijlage) is besproken in de werkgroep. Bovendien is in 2013 een focusgroepbijeenkomst gehouden met patiënten. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen.

Bij het herzien van de (sub)modules ‘conservatieve behandeling’, ‘(contra-)indicaties voor chirurgische behandeling’, ‘open chirurgische technieken’ en ‘minimaal invasieve technieken’ werd het patiëntperspectief vertegenwoordigd door afvaardiging van patiëntenorganisatie ReumaNederland in de werkgroep. Tot slot werden de herziene modules voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de relevante patiëntenorganisaties en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met een hallux valgus. De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbeveling(en) uit de eerdere richtlijnmodule (NOV, 2015) op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door een Invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen in de bijlagen. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt)organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, Glasziou P, Jaeschke R, Vist GE, Williams JW Jr, Kunz R, Craig J, Montori VM, Bossuyt P, Guyatt GH; GRADE Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ. 2008 May 17;336(7653):1106-10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39500.677199.AE. Erratum in: BMJ. 2008 May 24;336(7654). doi: 10.1136/bmj.a139.

Schünemann, A Holger J (corrected to Schünemann, Holger J). PubMed PMID: 18483053; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2386626.

Wessels M, Hielkema L, van der Weijden T. How to identify existing literature on patients' knowledge, views, and values: the development of a validated search filter. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016 Oct;104(4):320-324. PubMed PMID: 27822157; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5079497.

Zoekverantwoording

|

Richtlijn: Hallux Valgus |

|

|

Uitgangsvraag: Welke conservatieve behandeling van hallux valgus heeft de voorkeur? |

|

|

Database(s): Medline, Embase |

Datum: 26-2-2020 |

|

Periode: 2013- feb 2020 |

Talen: Engels |

|

Literatuurspecialist: Miriam van der Maten |

|

|

Toelichting en opmerkingen: Dit is een update van de eerdere search uit okt 2013. |

|

|

Database |

Zoektermen |

|

Medline (Ovid)

|