Minimaal invasieve technieken bij hallux valgus

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van minimaal invasieve technieken bij de behandeling van hallux valgus?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg minimaal invasieve chirurgie voor behandeling van een milde tot matige hallux valgus, mits de operateur over voldoende kennis, opleiding en ervaring beschikt.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de effectiviteit en veiligheid van minimale invasieve interventies (minimally invasive surgery, MIS) ten opzichte van open technieken voor de chirurgische behandeling van hallux valgus bij volwassenen. De bewijskracht van de literatuur werd gegradeerd als laag tot zeer laag volgens de GRADE-methode. Dit heeft te maken met het niet kunnen blinderen van de interventies, maar ook werden inconsistente onderzoeksresultaten gevonden en daarom moeten de conclusies kritisch worden beschouwd. Hier ligt een kennislacune. De aanbevelingen zullen daarom gebaseerd worden op aanvullende argumenten waaronder expert opinion, waar mogelijk onderbouwd met (indirecte) literatuur.

Bij de cruciale uitkomstmaten postoperatieve pijn en voetfunctie, gemeten met de AOFAS, werden geen klinisch relevante verschillen gevonden tussen de minimaal invasieve osteotomie en de open osteotomie tot een follow-up periode van 7 jaar. Een derde cruciale uitkomstmaat liet wel een klinisch relevant verschil zien, er leken meer re-interventies plaats te vinden na een minimaal invasieve osteotomie vergeleken met een open osteotomie, maar dit ging vooral om het verwijderen van osteosynthese materiaal.

De bewijskracht van de belangrijke uitkomstmaten complicaties en patiënttevredenheid waren zeer laag. Correctie van standsafwijking kon niet worden gegradeerd. Deze uitkomstmaten kunnen derhalve geen richting geven aan de besluitvorming.

Een recent uitgevoerde meta-analyse van Singh (2020), verschenen na het uitvoeren van de literatuuranalyse, laat net zoals de huidige analyse zien dat de MIS technieken veilig lijken te zijn, met een vergelijkbaar complicatierisico als de open techniek. Ook de radiologische uitkomst en pijnscores zijn vergelijkbaar.

De in de literatuur genoemde theoretisch voordelen van de MIS techniek zoals bijvoorbeeld een betere range of motion van het MTP-I gewricht en een lager infectie risico door minder weke delen letsel peroperatief worden niet in de gevonden studies bevestigd. Vergelijkend onderzoek van minimaal invasieve chirurgie met de doorgaans toegepaste conventionele open operaties zijn nog beperkt en er bestaat nog veel diversiteit in de toegepaste MIS technieken.

De MIS procedures is “work in progress” waarbij er nog steeds een fine-tuning plaatsvindt van de procedures.

Het is belangrijk om te realiseren dat:

- Er verschillende MIS technieken bestaan waarbij er onvoldoende literatuur beschikbaar is om deze MIS technieken individueel te beoordelen.

- De MIS procedure bij de hallux valgus chirurgie gestoeld is op de bekende open chirurgische procedures, gebruikmakend van extra-articulaire osteotomieën maar zonder aanvullende weke delen procedures.

MIS kan worden gebruikt voor verschillende distale hallux valgus procedures, zoals osteotomie van de metatarsalia en/of de phalanx (al dan niet met fixatie door bijvoorbeeld schroef of k-draad). Proximale osteotomieën van de eerste straal zijn minder toegankelijk voor MIS.

Voer een MIS techniek uit waarbij:

- Er een fixatie van de osteotomie plaatsvindt middels een schroef (geen K-draad) om de recidief kans te verkleinen.

- Gebruik geen uitstekende en gewricht overbruggende k-draden om de kans op stijfheid en infecties te verkleinen.

In de literatuur worden verschillende operatie technieken beschreven; hieronder geven wij een opsomming van de meest gebruikte minimaal invasieve technieken.

Wij maken hierbij onderscheid tussen:

- Percutane chirurgie, met de kleinst mogelijke incisie (1 tot 3 mm) en gebruikmaking van een beaver mesje voor de weke delen en een frees met een high torque, low speed burr voor de osteotomieën. Hierbij is er geen directe visualisatie maar fluoroscopische controle. Ook wordt hierbij gebruik gemaakt van specifiek instrumentarium om door de smalle opening te kunnen opereren. Het verwijderen van losgemaakte botfragmenten (bijvoorbeeld na osteotomie) gebeurt door spoelen en/of door manuele druk.

- Minimale incisie chirurgie, met een incisie van 1 tot 3 cm en gebruikmaking van een traditioneel scalpelblad voor weke delen en een zaagblad voor bot, al dan niet onder röntgendoorlichting.

Percutane Chirurgie

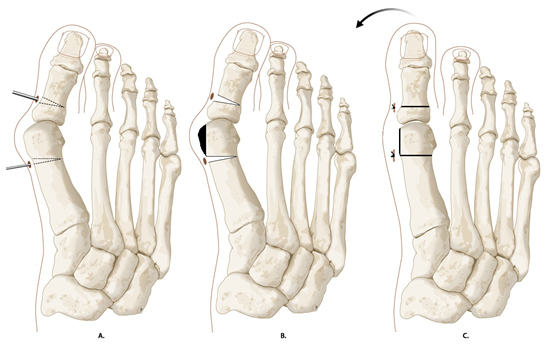

Minimally invasive Chevron and Akin (MICA/PECA)

De operatie wordt fluoroscopisch geassisteerd. Benadering met meerdere steek-incisies.

Met een ‘high torque, low speed burr’ wordt een extra-articulaire subcapitale chevron osteotomie verricht. Na lateralisatie wordt gefixeerd met 2 schroeven. Hierna wordt een percutane Akin osteotomie verricht gefixeerd met 1 schroef. Hierna wordt een percutane bunionectomie en een percutane laterale kapsel release vanuit de eerste webspace verricht.

Techniek del Prado (percutane Reverdin-Isham osteotomie)

De operatie wordt fluoroscopisch geassisteerd. De Techniek van del Prado bestaat uit een percutane bunionectomie, distale variserende subcapitale osteotomie van MT 1 (zonder lateralisatie) en Akin procedure met een “high torque, low speed burr”, zo nodig aanvullende laterale kapsel release. Behoud van correctie door een corrigerend verband.

Minimale incisie chirurgie

Bösch techniek en modificaties (SERI (Simple, Effective, Rapid, Inexpensive))

Er wordt een incisie van één centimeter gemaakt, waarna subcapitale osteotomie van MT 1 met een zaagje. Fixatie geschied na lateralisatie van het kopje met een gewrichtsoverbruggende (te verwijderen) kirschner-draad welke distaal in de weke delen en proximaal intra-medullair zit. Aanvullend kan een bunionectomie worden verricht. Deze K-draad gefixeerde techniek wordt door de werkgroep niet gepropageerd.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

Het doel van de operatieve behandeling van een hallux valgus voor de patiënt is het verminderen van de pijnklachten en de beschoeiingsproblemen, het herstel van een normale functie van de eerste straal, en het creëren van een langdurig cosmetisch acceptabel resultaat.

Om de waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten te onderzoeken is de uitkomstmaat ‘patiënttevredenheid’ meegenomen in het systematisch literatuuronderzoek. Drie studies rapporteerden over ‘patiënttevredenheid’. (Kaufmann, 2018; Lee, 2017) De bewijskracht werd gegradeerd als ‘very low GRADE’, en daarom zijn wij onzeker over de conclusies.

In de praktijk blijkt dat de specifieke groep van patiënten waarbij de cosmetiek een rol speelt, een voorkeur heeft voor de MIS techniek gezien de kleinere littekens. De MIS technieken zijn vaak intrinsiek stabiel en meestal snel belastbaar.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De werkgroep heeft geen literatuur kunnen vinden over het verschil in kosten van beide procedures maar verwachten hier in geen grote discrepanties die tot een voorkeur voor de een of andere procedure zal leiden.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De mate van adequate chirurgische correctie via de MIS techniek is sterk afhankelijk van de ervaring van de chirurg. Er is waarschijnlijk een lange leercurve voor deze techniek. De werkgroep is van mening dat de MIS-techniek alleen mag worden uitgevoerd door een chirurg met voldoende training. Er wordt dan ook geadviseerd om zich te laten scholen in deze techniek (Fellowship, Visiting Course, MIFAS cursus) voordat de operateur de techniek in de praktijk gaat toepassen. De werkgroep adviseert deze interventie alleen bij een hallux valgus met een milde tot matige deformiteit toe te passen.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De werkgroep beschouwt de MIS techniek als een nieuwe procedure die nog steeds in ontwikkeling is. In de beschikbare literatuur lijkt de MIS-techniek het bij milde tot matige deformiteit op het gebied van postoperatieve pijn en mate van correctie dezelfde resultaten heeft als de open technieken. Wel worden er meer re-interventies beschreven, door het verwijderen van k-draden. De werkgroep adviseert alleen een schroef gefixeerde MIS-techniek toe te passen. Zoals ook bij de literatuur over de open hallux valgus correcties, blijft het moeilijk om een duidelijke sturing te geven over welke MIS-technieken het beste kunnen worden toegepast, waarschijnlijk speelt ervaring hierin een zeer belangrijke rol.

Er wordt geadviseerd om zich te laten scholen in deze techniek voordat de operateur de techniek in de praktijk gaat toepassen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

De laatste jaren is er in toenemende mate een interesse voor minimaal invasieve chirurgische (minimally invasive surgery, MIS) technieken binnen de orthopedie. Ook bij hallux valgus chirurgie wordt in toenemende mate gebruik gemaakt van minimaal invasieve technieken. Bij MIS is, in tegenstelling tot de conventionele open chirurgie, de toegangsweg tot het te opereren gebied een portal-achtige incisie. De potentiële voordelen van de MIS techniek zou verminderde weke delen schade moeten zijn, leidend tot minder vasculaire schade, litteken vorming en gewrichtsstijfheid. De principes van de operatieve technieken gebruikt bij de MIS zijn gestoeld op de bekende technieken van de open hallux valgus technieken. Er worden vergelijkbare osteotomieën gebruikt maar bij de MIS zoveel mogelijk extra-articulair. Groot verschil is uiteraard dat er geen aanvullende weke delen procedures worden verricht. De effectiviteit en veiligheid van deze technieken zijn echter nog onvoldoende duidelijk.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Low GRADE |

Postoperative pain does not seem to be different after minimally invasive techniques compared to open procedures in the treatment of mild to moderate hallux valgus (follow-up: 6 weeks to 5 years).

Sources: (Kaufman, 2018; Kaufman, 2020; Lee, 2017) |

|

Low GRADE |

Function of the foot does not seem to be different after minimally invasive techniques compared to open procedures in the treatment of mild to severe hallux valgus in adults (follow-up: 6 weeks to 7 years).

Sources: (Giannini, 2013; Kaufman, 2018; Kaufman, 2020; Lee, 2017; Radwan, 2012) |

|

Low GRADE |

Minimally invasive procedures may lead to more reoperations compared to open procedures in the treatment of mild to severe hallux valgus in adults.

Sources: (Giannini, 2013; Lee, 2017.) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is uncertain whether complication rate is different after minimally invasive procedures compared to open procedures for the treatment of mild to severe hallux valgus in adults.

Sources: (Giannini, 2013; Lee, 2017; Radwan, 2012) |

|

- GRADE |

It was not possible to draw conclusions or grade the level of evidence for the outcome valgus deformity correction due to lack of data. |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is uncertain whether the treatment with minimally invasive procedures results in more satisfaction compared to open procedures for the treatment of mild to severe hallux valgus in adults.

Sources: (Lee, 2017; Kaufmann, 2018.) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Percutaneous technique

Kaufmann (2018) and Kaufmann (2020) compared patients with mild to moderate hallux valgus who underwent a minimally invasive chevron osteotomy (MICA) with Kirschner-wire fixation (no screw fixation) procedure to patients who underwent the well-established open chevron procedure (fixation of one cannulated screw). Patients were randomly assigned to one of the two procedures. Maximum length of follow-up was five years. Kaufmann (2018) reported that there were no patients lost to follow-up. In the follow-up study (Kaufmann, 2020), eight patients were reported as lost to follow-up. The following relevant outcome measures were included: VAS-score, AOFAS-score, valgus deformity correction and patients’ satisfaction.

Lee (2017) compared outcomes of third-generation percutaneous modified chevron and akin osteotomies (PECA) and open scarf/akin osteotomies (SA)for the correction of moderate to severe hallux valgus. In the PECA procedure 3-point screw and guide wire fixation was used, while the SA procedure also used screw fixation combined with Kirschner-wire fixation. Fifty patients with hallux valgus deformities were randomized equally over the two procedures. The length of follow-up was 6 months. No patients were lost to follow-up. The following relevant outcome measures were included: VAS-score and AOFAS-score.

Minimum incision surgery

Giannini (2013) compared the functional outcomes, radiographic correction and complications between a traditional distal metatarsal osteotomy with two rigid three millimeter screw fixation (Scarf procedure) compared to a minimally invasive approach (SERI) with Kirschner wire fixation to a distal metatarsal osteotomy in patients with mild to moderate hallux valgus deformity. Twenty patients underwent bilateral surgery with Scarf on one side and SERI on the other, at random. The length of follow-up was 7 years. No patients were lost to follow-up. The following relevant outcome measures were included: AOFAS-score, re-operation (hardware removal), complications and correction of deformity.

Radwan (2012) compared the results of 64 consecutive feet of 53 patients with mild to moderate symptomatic hallux valgus with percutaneous distal metatarsal osteotomy (Bosch technique) and distal chevron osteotomy, both with Kirschner-wire fixation. Patients were randomly assigned to one of the interventions. Clinical assessment was based on the results of the AOFAS and radiographical assessment with the hallux valgus angle and intermetatarsal angle. The minimum follow-up length was 12 months. Two patients from each group were lost to follow-up. The following relevant outcome measures were included: AOFAS-core, complications, correction of deformity and patient satisfaction.

Results

Pain

VAS-scores were reported at different follow-up moments. Lee (2017) reported VAS-scores at 6 weeks and 6 months, and Kaufmann (2018 & 2020) reported VAS-scores at 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 9 months, and 5 years. No studies reported pain outcomes at 1 year follow-up.

Short-term

Lee (2017) reported a VAS-score at 6 weeks (mean, SD) follow-up of 0.6 (1.8) in the minimally invasive osteotomy and 2.1 (2.0) in the open osteotomy group. Difference between groups is considered clinically relevant. Kaufmann (2018) did not find differences in median VAS-scores at 6 weeks between the minimally invasive osteotomy versus open osteotomy, median (IQR): 1 (3) versus 1 (2), no clinically relevant difference between groups.

Kaufmann (2018) reported a VAS-score at 12 weeks follow-up. The median (IQR) VAS-score was 0 (2) in the minimally invasive group and 1 (2) in open procedure group, which is not considered a clinically relevant difference between groups.

Mid-term

Lee (2017) reported a VAS-score at 6 months (mean, SD) follow-up of 0.3 (0.9) in the minimally invasive osteotomy and 0.5 (1.1) in the open osteotomy group. The difference between groups is not considered clinically relevant. Kaufmann (2018) reported a VAS-score at 9 months follow-up. The median (IQR) VAS-score was 1 (2) in the minimally invasive group and 0 (3) in open procedure group, which is not considered a clinically relevant difference between groups.

Long term

Kaufmann (2020) reported a VAS-score at 5 years follow-up. The median (IQR) VAS-score was 0 (1) in the minimally invasive group and 0 (2) in open procedure group, which is not considered as a clinically relevant difference between groups.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain comes from a randomized controlled trial and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of lack of blinding of the outcome assessment (risk of bias) and small number of patients included in the studies (imprecision). The level of evidence was low.

Foot function

AOFAS-scores were reported at different follow-up moments. Kaufmann (2018) reported AOFAS-scores at 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 9 months, and 5 years. Lee (2017) reported AOFAS-scores at 6 months. Radwan (2012) reported AOFAS at 8 months. Giannini (2013) reported at two and seven year follow-up, and Kaufmann (2020) reported at 5 years follow-up.

Short-term

Kaufmann (2018) reported a median (IQR) AOFAS-score at 6 weeks follow-up. The median (IQR) AOFAS-score was 77 (17) in the minimally invasive osteotomy group and 72 (9) in the open osteotomy group. Kaufmann (2018) reported a median (IQR) AOFAS-score at 12 weeks. The median (IQR) AOFAS-score was 85 (14) for the minimally invasive osteotomy group and 83.5 (14) for the open osteotomy group. These differences were not considered clinically relevant.

Mid-term

Lee (2017) reported a mean (SD) AOFAS-score at 6 months. The mean (SD) AOFAS-score was 88.7 (2.1) for the minimally invasive osteotomy group versus 83.0 (3.5) for the open osteotomy group. Radwan (2012) did not find differences in mean (SD) AOFAS-scores at 8 months between the minimally invasive osteotomy group and the open osteotomy group, mean (SD): 90.24 (6.80) versus 87.71 (6.0), no clinically relevant difference between groups. Kaufmann (2018) reported a median (IQR) AOFAS-score at 9 months. The median (IQR) AOFAS-score was 85 (15) for the minimally invasive osteotomy group versus 90 (14) for the open osteotomy group. This is not considered a clinically relevant difference.

Long-term

Giannini (2013) reported a mean (SD) AOFAS-score at 2 years. The mean (SD) AOFAS-score was 89 (10) for the minimally invasive osteotomy and 87 (12) for the open osteotomy. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference. Kaufmann (2020) reported a median (IQR) score at 5 years. The median (IQR) AOFAS-score was 95 (10) for the minimally invasive osteotomy group. The median (IQR) AOFAS-score for the open osteotomy group was 95 (14). This is not considered to be a clinically relevant difference. Giannini (2013) reported a mean (SD) AOFAS-score at 7 years. The mean (SD) AOFAS-score was 81.2 (15.1) for the minimally invasive osteotomy and 77.6 (16.6) for the open osteotomy. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘foot function’ comes from randomized controlled trials and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of lack of blinding of the outcome assessment (risk of bias) and small number of samples in the studies (imprecision). The level of evidence was low.

Re-operation (hardware removal)

Two studies (Giannini, 2013; Lee, 2017) reported re-operation. Both studies reported re-operation in the minimally invasive osteotomy group. No re-operations were reported in the open osteotomy group. Lee (2017) reported re-operation due to screw removals in 6 patients. Giannini (2013) reported re-operations due to hardware removal in 2 patients. This is considered to be a clinically relevant difference between the groups.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain comes from randomized controlled trials and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of limited number of events and because the confidence intervals crossed the clinical decision threshold (both imprecision). The level of evidence was low.

Complications

Three studies (Radwan, 2012; Giannini, 2013; Lee, 2017) reported postoperative complications after hallux valgus surgery. Reported complications were incidence of metatarsalgia (Lee, 2017), incidence in reduction of range of motion (Giannini, 2013), and incidence of infections (Radwan, 2012). Radwan (2012) reported two infections in the minimally invasive osteotomy group and one in the open osteotomy group. Giannini (2013) reported reduction in range of motion in 3 patients in the minimally invasive osteotomy group compared to 3 patients in the open osteotomy group. Lee (2017) only reported complications in terms of metatarsalgia in the open procedure group. Six patients in the open osteotomy group reported metatarsalgia. None of the patients in the minimally invasive osteotomy group reported metatarsalgia.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure complications comes from randomized controlled trials and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded with three levels to very low due to conflicting results (inconsistency), due to the limited number of events, the confidence interval crossed the clinical decision threshold (both imprecision), and inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation (risk of bias). The level of evidence was very low.

Correction of deformity

In the included literature, the ratio of patients that achieved valgus deformity correction was not described. Most studies reported the pre- and postoperative angles.

Intermetatarsal angle

Kaufmann (2018) reported a median (IQR) IMA at baseline of 14.0˚ (3.8) for the minimally invasive osteotomy group and 15.2˚ (3.2) for the open osteotomy group. The median (IQR) IMA at 6 weeks was 7.3˚ (1.9) for the minimally invasive osteotomy group versus 7.7˚ (3.2) for the open osteotomy group. At 12 weeks, the median (IQR) IMA was 7.7˚ (2.8) for the minimally invasive osteotomy group versus 7.5˚ (3.1) for the open osteotomy group. Finally, at 9 months, the median (IQR) IMA was 6.8˚ (3.0) for the minimally invasive osteotomy group versus 5.9˚ (3.7) for the open osteotomy group.

Giannini (2013) reported that in the minimal invasive group, the IMA changed from (mean ± SD) 16.1° ± 3.9° to 6.8° ± 4.3° at the 7 year follow-up, versus 16.1° ±3.8° to 8.3° ± 3.4° in the open surgery group.

Hallux valgus angle

Kaufmann (2018) reported a median (IQR) HVA at baseline of 26.4˚ (12) for the minimally invasive osteotomy group and 28.3˚ (8.3) for the open osteotomy group. At 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 9 months, the postoperative HVA was 10.5˚ (8.7), 8.8˚ (8.0) and 6.9˚ (7.6), respectively in the minimal invasive group, versus 9.9˚ (7.9), 9.2˚ (9.7) and 8.5˚ (8.8) for the open osteotomy group. At 5-year follow-up, HVA was 9.8˚ (10.7) in the minimally invasive group versus 10.3˚ (12.1) in the open osteotomy group.

Radwan (2012) reported a preoperative HVA (mean ± SD) for the minimally invasive technique of 27.6˚ ± 4.4 versus 26.1˚ ± 3.3 for the open technique. At 8 months postoperatively, the HVA was 13.1˚ (2.8) for the minimally invasive osteotomy group and 12.8˚ ± 2.9 for the open osteotomy group.

In the study by Giannini (2013), the HVA (mean ± SD) changed from 35.8˚ ± 3.5˚ to 21.8˚ ± 4.1˚ at the 7 year follow-up in the minimally invasive group, versus 35.5˚ ± 4.7˚ to 20.1˚ ± 3.6˚ after open surgery.

Distal metatarsal articular angle

Kaufmann (2020) reported a median (IQR) DMAA at baseline of 22.2˚ (15.6) for the minimally invasive osteotomy group and 24.5˚ (9.8) for the open osteotomy group. At 5 years, DMAA was 9.8˚ (10.7) and 10.3˚ (12.1) for minimally invasive and open technique, respectively.

In the study by Giannini (2013) the DMAA changed from 21.7˚ ± 5.5˚ to 15.9˚ ± 5.4˚ in the minimally invasive group, and from 21.7˚ ± 8.4˚ to 15.0˚ ± 7.5˚ in the open technique group.

Level of evidence of the literature

For the outcome correction of deformity, the level of evidence could not be determined due to lack of data.

Patient satisfaction

Three studies (Kaufmann, 2018; Lee, 2017) reported patient satisfaction, however satisfaction was assessed differently among these studies. Radwan (2012) reported the number of subjects that were satisfied regarding the cosmetic result (yes or no). Kaufmann (2018 & 2020) reported satisfaction in four categories (very satisfied; satisfied; do not know; not satisfied) and reported the percentage of subjects for every category. Lee (2017) also reported four different categories but used different terms for satisfaction: excellent; good; fair; poor.

In the study of Kaufmann (2018), 63% of the patients reported satisfaction as ‘very satisfied’, 25% reported satisfaction as ‘satisfied’, 4% reported satisfaction as ‘do not know’, and 8% reported ‘not satisfied’ in the minimally invasive osteotomy group in the study of Kaufmann (2018). In the open osteotomy group, 70% of the patients reported ‘very satisfied’, 15% reported ‘satisfied’, and 15% reported ‘not satisfied’. At 5 years, 89% of the patients in the minimally invasive osteotomy group reported satisfaction as ‘very satisfied’. In the open osteotomy group, 70% of the patients reported satisfaction as ‘very satisfied’.

In the study of Lee (2017), 84% of the patients in the minimally invasive osteotomy group scored ‘excellent’ and 16% reported ‘good’ satisfaction. In the open osteotomy group, 72% of the patients reported satisfaction as ‘excellent’, and 28% patients reported satisfaction as ‘good’.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure satisfaction comes from randomized controlled trials and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of lack of blinding of the outcome assessment (risk of bias), small number of samples (imprecision) and heterogeneity in the interpretation of the results (inconsistency). The level of evidence was very low.

Zoeken en selecteren

The clinical question is:

what is the value of minimally invasive surgery in the treatment of hallux valgus? A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the effectiveness and safety of minimally invasive surgery versus open surgery in the treatment of hallux valgus deformities?

P: patients with hallux valgus deformities;

I: minimally invasive surgery;

C: open surgery procedures (Chevron, Scarf, distal and proximal osteotomies and Lapidus procedure);

O: pain (VAS-score), foot function (AOFAS-score), recurrence or reoperation, complications (infection, delayed union), valgus deformity correction, patient satisfaction.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered pain, foot function and recurrence or reoperation as critical outcomes measures for clinical decision making; and complications (infection, delayed union), valgus deformity correction and patient satisfaction as important outcome measures for clinical decision making.

A priori, the working group defined valgus deformity correction as a dichotomous outcome, whether or not postoperative HVA < 15° and IMA < 9° were obtained. The working group did not define the other outcomes listed above but followed the definitions used in the studies. The working group defined 25% as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for dichotomous outcomes, 0.5 SD for standardized mean differences (SMD) and 15% of the maximum score for pain (VAS) and 10% of the maximum score for function (AOFAS).

Search and select (Methods)

For literature until 2009, the systematic literature search for the NICE guideline (2010) was followed. The databases Medline (via OVID), Embase (via Embase.com) and Cochrane were searched for clinical studies reporting minimally invasive treatment of hallux valgus. Ten case series were identified. The search was updated in March 2 (2020). The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The updated search resulted in 26 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews and randomized trials comparing minimally invasive surgery with open surgery in the treatment of hallux valgus. Thirteen studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, eight studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and five studies were included.

Results

Five studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Giannini S, Cavallo M, Faldini C, Luciani D, Vannini F. The SERI distal metatarsal osteotomy and Scarf osteotomy provide similar correction of hallux valgus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013 Jul;471(7):2305-11. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-2912-z. Epub 2013 Mar 14. PMID: 23494184; PMCID: PMC3676577.

- Kaufmann G, Dammerer D, Heyenbrock F, Braito M, Moertlbauer L, Liebensteiner M. Minimally invasive versus open chevron osteotomy for hallux valgus correction: a randomized controlled trial. Int Orthop. 2019 Feb;43(2):343-350. doi: 10.1007/s00264-018-4006-8. Epub 2018 Jun 4. PMID: 29869014; PMCID: PMC6399198.

- Kaufmann G, Mörtlbauer L, Hofer-Picout P, Dammerer D, Ban M, Liebensteiner M. Five-Year Follow-up of Minimally Invasive Distal Metatarsal Chevron Osteotomy in Comparison with the Open Technique: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020 May 20;102(10):873-879. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.19.00981. PMID: 32149929.

- Lee M, Walsh J, Smith MM, Ling J, Wines A, Lam P. Hallux Valgus Correction Comparing Percutaneous Chevron/Akin (PECA) and Open Scarf/Akin Osteotomies. Foot Ankle Int. 2017 Aug;38(8):838-846. doi: 10.1177/1071100717704941. Epub 2017 May 5. PMID: 28476096.

- Radwan YA, Mansour AM. Percutaneous distal metatarsal osteotomy versus distal chevron osteotomy for correction of mild-to-moderate hallux valgus deformity. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012 Nov;132(11):1539-46. doi: 10.1007/s00402-012-1585-5. Epub 2012 Jul 22. PMID: 22821414.

- Singh MS, Khurana A, Kapoor D, Katekar S, Kumar A, Vishwakarma G. Minimally invasive versus open distal metatarsal osteotomy for hallux valgus - A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2020 May-Jun;11(3):348-356. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2020.04.016. Epub 2020 Apr 21. PMID: 32405192; PMCID: PMC7211908.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for intervention studies

Research question: What is the effectiveness and safety of minimally invasive surgery versus open surgery in the treatment of hallux valgus deformities?

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Kaufmann, 2019 |

Sealed envelopes. |

Unlikely

|

Unlikely

|

Likely

Blinding of the surgeon is not possible. |

Unclear

Not specified. |

Unlikely

|

Unlikely

No loss to follow-up. |

Unlikely |

|

Lee, 2017 |

Stratified block randomisation. |

Unlikely

Block randomisation was performed by a biostatistician blinded for the study purpose. |

Unlikely

|

Likely

Blinding of the surgeon is not possible. |

Unlikely

HVA en IMA were assessed by a professional blinded for the intervention. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely

No loss to follow-up. |

Unlikely |

|

Giannini, 2013 |

List with random numbers. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely

|

Likely

Blinding of the surgeon is not possible. |

Unclear

Not specified. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely

All patients underwent clinical and radiographic evaluations. |

Unlikely |

|

Radwan, 2012 |

Randomized computer list. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely

|

Likely

Blinding of the surgeon is not possible. |

Unclear

Not specified. |

Unlikely |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Malagelada, 2019 |

Overlap with Bia, 2018 |

|

Caravelli, 2018 |

Overlap with Bia, 2018 |

|

Lai, 2018 |

Observational study |

|

Giannini, 2013 |

No comparative study |

|

Giannini, 2013 |

Duplicate |

|

Crespo, 2017 |

No comparative study |

|

Boksh, 2018 |

Observational study |

|

Di Giorgio, 2016 |

Comparison with endolog, not relevant for Dutch situation |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 08-10-2021

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 29-07-2021

Algemene gegevens

De herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

De richtlijn is ontwikkeld in samenwerking met:

- Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap voor Fysiotherapie

- Stichting Landelijk Overkoepelend Orgaan voor de Podologie

- Nederlandse Vereniging van Podotherapeuten

- NVOS-Orthobanda

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Anesthesiologie

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Radiologie

- ReumaNederland

- Patiëntenfederatie Nederland

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met een hallux valgus.

Werkgroep

- Drs. W.P. Metsaars, orthopedisch chirurg bij Annatommie MC (voorzitter), NOV

- Dr. I.V. van Dalen, orthopedisch chirurg in de Bergman Kliniek, NOV

- Dr. M.A. Witlox, orthopedisch chirurg in MUMC, NOV

- Drs. S.B. Keizer, orthopedisch chirurg in Haaglanden MC, NOV

- C.J.C.M. Hoogeveen, podoposturaal therapeut bij Praktijk voor Podoposturale Therapie, KNGF en Stichting LOOP

- A.P. van Dam, orthopedisch schoentechnoloog bij Graas Company, NVOS-Orthobanda

- S.C.C. Scheepens, podotherapeut bij Scheepens en Klijsen Podotherapie, NVvP

- N. Lopuhaä, beleidsmedewerker Patiëntbelangen, ReumaNederland

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. S. Persoon, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. M.S. Ruiter, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Metsaars (voorzitter) |

Orthopedisch chirurg, voet en enkel, Annatommie MC |

Penningmeester Dutch Foot & Ankle Society: onbetaald, verrichten expertises, DC expertise centrum: betaald. |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Scheepens |

Podotherapeut/eigenaar 30-40u/wk Scheepens en Vijsen Podotherapie |

Externe beoordelaar Fontys Hogeschool opleiding podotherapie betaald 2 x halve dag per jaar; |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van Dalen |

Orthopedisch chirurg, voet en enkel, Bergmanclinics te Naarden fulltime |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Lopuhaä |

Beleidsmedewerker Patientenbelangen ReumaNederland |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Hoogeveen |

Werkzaam als podoposturaal therapeut in eigen praktijk - de Praktijk voor Podoposturale Therapie- in Nieuwegein (1,5 dag per week) met als achtergrond fysiotherapeut, manueel therapeut (Niet praktiserend)

Mede eigenaar van Kennis- en Opleidingsinstituut voor Voet, Houding en Beweging (3 dagen per week) - functie ontwikkelaar van oefenprotocollen voor de voet en opleiding voetentrainer voor fysio- en oefentherapeuten. |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Keizer |

Orthopedisch Chirurg, Haaglanden MC. |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van Dam |

Orthopedisch Schoentechnoloog en directeur/eigenaar bij Graas Orthopedische Schoentechniek voor 38 uur per week |

Vicevoorzitter van NVOS-Orthobanda, branchevereniging voor zorgondernemers in orthopedische hulpmiddelen, onbetaalde functie. Voorzitter van Stichting Thuishuis Woerden, zet zich in tegen eenzaamheid onder ouderen in Woerden, onbetaalde functie. |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Witlox |

Orthopedisch Chirurg, MUMC+ |

Bestuur WKO, niet betaald Penningmeester oudervereniging OBS Maastricht, niet betaald |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Persoon |

Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Ruiter |

Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntperspectief door Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en andere relevante patiëntenorganisaties uit te nodigen voor de Invitational conference. Het verslag hiervan (zie bijlage) is besproken in de werkgroep. Bovendien is in 2013 een focusgroepbijeenkomst gehouden met patiënten. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen.

Bij het herzien van de (sub)modules ‘conservatieve behandeling’, ‘(contra-)indicaties voor chirurgische behandeling’, ‘open chirurgische technieken’ en ‘minimaal invasieve technieken’ werd het patiëntperspectief vertegenwoordigd door afvaardiging van patiëntenorganisatie ReumaNederland in de werkgroep. Tot slot werden de herziene modules voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de relevante patiëntenorganisaties en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met een hallux valgus. De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbeveling(en) uit de eerdere richtlijnmodule (NOV, 2015) op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door een Invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen in de bijlagen. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt)organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, Glasziou P, Jaeschke R, Vist GE, Williams JW Jr, Kunz R, Craig J, Montori VM, Bossuyt P, Guyatt GH; GRADE Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ. 2008 May 17;336(7653):1106-10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39500.677199.AE. Erratum in: BMJ. 2008 May 24;336(7654). doi: 10.1136/bmj.a139.

Schünemann, A Holger J (corrected to Schünemann, Holger J). PubMed PMID: 18483053; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2386626.

Wessels M, Hielkema L, van der Weijden T. How to identify existing literature on patients' knowledge, views, and values: the development of a validated search filter. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016 Oct;104(4):320-324. PubMed PMID: 27822157; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5079497.

Zoekverantwoording

|

Richtlijn: Hallux valgus |

|

|

Uitgangsvraag: Wat is de effectiviteit en veiligheid van minimaal invasieve technieken? |

|

|

Database(s): Medline, Embase |

Datum: 25-5-2020 |

|

Periode: 2013- mei 2020 |

Talen: Engels |

|

Literatuurspecialist: Miriam van der Maten |

|

|

Database |

Zoektermen |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Embase

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medline (OVID)

|

1 Hallux Valgus/ 2 ((("Great Toe*" or hallux) adj3 (Deform* or Valgus or Deviat* or abduct*)) or Bunion* or abductovalgus or "metatarsus primus varus").ti,ab. 3 1 or 2 4 "Orthopedic Procedures"/ 5 (surgery or surgeon or surgical or operati*).ti. 6 Osteotomy/ or Osteotom*.ti,ab. 7 Bone Screws/ or lapidus.ti,ab. 8 Arthrodesis/ or Arthrodes*.ti,ab. 9 (scarf or chevron or mitchell).ti,ab. 10 or/4-9 11 3 and 10 and ((minimal* adj3 invasive).ti,ab. or (mica or 'Reverdin-Isham' or silver or mis).ti,ab.) 12 Hallux Valgus/su and (minimal* adj3 invasive).ti,ab. 13 11 or 12 14 limit 13 to (yr="2013 -Current" and (dutch or english)) ) 15 (meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (meta adj analy$).tw. or ((systematic* or literature) adj2 review$1).tw. or (systematic adj overview$1).tw. or exp "Review Literature as Topic"/ or cochrane.ab. or cochrane.jw. or embase.ab. or medline.ab. or (psychlit or psyclit).ab. or (cinahl or cinhal).ab. or cancerlit.ab. or ((selection criteria or data extraction).ab. and "review"/)) not (Comment/ or Editorial/ or Letter/ or (animals/ not humans/)) 16 14 and 15 17 (exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or random*.ti,ab. or (clinic* adj trial*).tw. or ((singl* or doubl* or treb* or tripl*) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo*.tw.) not (animals/ not humans/) 18 (14 and 17) not 16 19 16 or 18 |