Unicompartimentele versus een totale knieprothese bij geïsoleerde mediale en laterale artrose van de knie

Uitgangsvraag

Wanneer is een unicompartimentele knieprothese versus een totale knieprothese geïndiceerd bij unicompartimentele knieartrose?

Aanbeveling

Plaats bij voorkeur een unicompartimentele knieprothese bij patiënten met eindstadium symptomatische unicompartimentele knieartrose met een operatie indicatie en één of meer van de volgende kenmerken:

- eindstadium (KL4) unicompartimentele artrose (op röntgenopname);

- functioneel intacte VKB (op X-knie lateraal geen posteromediale artrose, of op MRI intacte VKB). Dit is minder strikt bij een UKP met fixed bearing;

- normale functionaliteit collaterale ligament bij intacte overige ligamenten (mediaal en lateraal collateraal ligament en achterste kruisband);

- reductie intra-articulaire varus/valgus deformiteit (bij valgus/varus stress opname geen functionele verkorting van de MCL/LCL).

Plaats géén unicompartimentele knieprothese bij patiënten met inflammatoire artritis.

Wees terughoudend met het plaatsen van een unicompartimentele knieprothese bij patiënten met met een operatie indicatie en één of meer van de volgende kenmerken:

- geen volledige kraakbeendikte contralaterale compartiment (op belaste X-knie, eventueel aangevuld met een valgus/varus stress opname);

- fixed varus deformiteit (> 10 graden);

- fixed valgus deformiteit (> 10 graden);

- functiebeperking (flexie < 90 graden, extensiebeperking > 10 graden);

- tibiakoposteotomie;

- uitgesproken patellofemorale artrose (patellaopname).

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is een literatuuranalyse uitgevoerd naar de positieve en negatieve effecten van de unicompartimentele knieprothese (UKP) ten opzichte van de totale knieprothese (TKP) voor patiënten met unicompartimentele artrose van de knie. Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten “pijn” en “kwaliteit van leven” kon geen voorkeur worden uitgesproken door de zeer lage bewijskracht. Hier ligt een kennislacune.

De belangrijke uitkomstmaten “functie”, “complicaties”, “patiënttevredenheid” vertoonden geen verschillen tussen de groepen. De uitkomstmaat “implant survival” werd gerapporteerd in de vorm van heroperatie en revisie. Laatstgenoemde was in de geïncludeerde literatuur niet consistent: na 5 jaar was het risico op revisie bij UKP hoger dan bij TKP, terwijl dit risico na 10 en 15 jaar juist lager was. Dit kan ermee te maken hebben dat er bij persisterende klachten na een UKP laagdrempeliger gereviseerd wordt dan na een TKP, aangezien de revisie minder ingrijpend lijkt. Ook zien we een verschil in de oudere studies (1998 tot 2011) en een nieuwere studie (uit 2019). De oudere studies (1998-2011) geven een voordeel voor survival van de prothese voor de TKP, maar de studie uit 2019 een voordeel voor UKP. Een mogelijke verklaring is dat er meer kennis en ervaring is opgedaan wanneer er een indicatie is voor een UKP en/of wanneer er na een UKP een indicatie bestaat voor revisie.

De door de patiënt gerapporteerde combinatie van pijn en functie leek beter na een unicompartimentele knieprothese, maar het verschil was niet klinisch relevant. Voor de uitkomstmaten “terugkeer naar werk” en “terugkeer naar sport” werden geen resultaten beschreven in de geselecteerde gerandomiseerde studies.

De totale bewijskracht, de laagste gevonden bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten, is zeer laag. De bewijskracht van de andere uitkomstmaten was laag.

Er zijn diverse studies uitgevoerd naar de verschillen in uitkomsten na plaatsing van UKP versus TKP, maar de aantallen patiënten beschreven in gerandomiseerd onderzoek waren beperkt. De vraag is of meer gerandomiseerd onderzoek naar de verschillen tussen de twee typen protheses geïndiceerd is om een uitspraak te kunnen doen over een eventueel verschil of dat de antwoorden eerder uit register- en cohortstudies moeten komen.

Op basis van de geïncludeerde literatuur lijkt er geen duidelijke voorkeur voor de ene of de andere prothese. Er zijn echter beperkingen om uitspraken te kunnen doen op basis van de geïncludeerde RCT’s. RCT’s hebben doorgaans onvoldoende power om eventuele verschillen in revisie aan te kunnen tonen. Retrospectieve cohort studies of registerstudies zijn hier meer voor geschikt. Landelijke registers laten dan ook een ander beeld zien. Zo laat de Engelse register (NJR) een 10-jaars risico op revisie zien voor een UKP van 12,23% in vergelijking met 3,43% voor een TKP (National Joint Registry, 2018). Aangezien deze data niet gematched is, is dit niet direct vergelijkbaar met elkaar. Andere literatuur laat >6% verschil zien in het aantal revisies ten nadele van UKP (Chawla 2017). Het nadeel hiervan is dat patiënten in een register die een TKP krijgen grotendeels andere patiënten zijn dan patiënten die een UKP krijgen (andersom is dat niet het geval). Dit kan leiden tot bias. Andere nadelen van registerstudies zijn de heterogeniteit van patiënten, chirurgen en type protheses. Dat de kans op revisie na een UKP hoger is, heeft er waarschijnlijk mee te maken dat chirurgen laagdrempeliger kiezen voor een revisie naar een TKP bij persisterende klachten. Een revisie van een TKP is ingrijpender, en hier zal dan ook minder snel voor worden gekozen. Ook heeft de kennis en ervaring van de chirurg invloed op de risico op een revisie na een UKP. Een laag-volume centrum heeft een duidelijke invloed op de kans op revisie na een UKP (Liddle, 2016; Liddle, 2014). Uit registerstudies komt een verhoogd risico op een revisie na een UKP (6 tot 21%) als deze geplaatst wordt in een laag-volume centrum (Kleeblad, 2017; Van Oost, 2020).

Er zijn nog meer overwegingen die meegenomen kunnen worden voordat de chirurg samen met patiënt de keuze maakt voor een UKP danwel een TKP (shared decision making). Het plaatsen van een UKP is minder invasief (kleinere incisie) en er worden meer anatomische structuren behouden. De opnameduur is korter van een UKP dan een TKP (Newman, 2009; Beard, 2019; Wilson, 2019); veel patiënten kunnen dezelfde dag of de eerste dag na operatie met ontslag. Het lijkt erop dat de revalidatie na een UKP sneller is dan na een TKP. Na een UKP zijn patiënten eerder weer aan het werk en sport, wat hun kwaliteit van leven ten goede komt (Kievit, 2019; Witjes, 2016). Patiënten ervaren na een UKP vaker dat hun knie als hun eigen knie voelt (Forgotten Joint Score) vergeleken met een TKP (Tueking, 2019). Echter de hogere kans op revisie en de kortere tijd tot een revisie na een UKP moet worden meegenomen in de overweging en besproken met de patiënt. Jonge patiënten (< 65 jaar) hebben al een hogere kans op revisiechirurgie ergens gedurende hun leven, dus het plaatsen van een knieprothese moet sowieso zo lang mogelijk uitgesteld worden. Ook voor oudere patiënten kan er een voorkeur zijn voor een UKP, gezien het snellere herstel en minder risico’s op complicaties. Tevens is er bij oudere patiënten minder risico op progressie van de artrose, waardoor het risico op revisie naar een TKP lager is (Howieson, 2015). Ook de kennis en ervaring van de behandelend orthopedisch chirurg moet worden meegenomen in de keuze van de behandeling.

In overleg met de patiënt wordt een behandeling gekozen die het beste past bij de specifieke omstandigheden en voorkeuren van de patiënt. De indicatie voor het plaatsen van een UKP moet bekend zijn bij de behandelend orthopedisch chirurg. Een UKP wordt alleen geplaatst bij eindstadium unicompartimentele artrose (KL4) en ernstige klachten. Meestal is dit het mediale compartiment. Literatuur over een laterale unicompartimentele knieprothese is beperkt. Bij een andere indicatie dan primaire unicompartimentele artrose, zoals bij inflammatoire artritis wordt een TKP geadviseerd.

Criteria voor UKP bij artrose (Teuking, 2020; Beard, 2007; Goodfellow, 1988; Berend, 2015):

- Eindstadium (KL4) unicompartimentele artrose (op röntgenopname).

- Functioneel intacte VKB (op X-knie lateraal geen posteromediale artrose, of op MRI intacte VKB). Dit is minder strikt bij een UKP met fixed bearing.

- Normale functionaliteit collaterale ligament bij intacte overige ligamenten (mediaal en lateraal collateraal ligament en achterste kruisband).

- Reductie intra-articulaire varus/valgus deformiteit (bij valgus/varus stress opname geen functionele verkorting van de MCL/LCL).

Contra-indicaties voor UKP

- Inflammatoire artritis.

Relatieve contra-indicaties voor UKP

- Geen volledige kraakbeendikte contralaterale compartiment (op belaste X-knie, eventueel aangevuld met een valgus/varus stress opname).

- Fixed varus deformiteit (> 10 graden).

- Fixed valgus deformiteit (> 10 graden).

- Functiebeperking (flexie < 90 graden, extensiebeperking > 10 graden).

- Tibiakoposteotomie.

- Uitgesproken patellofemorale artrose (patellaopname).

Het niet hebben van volledig kraakbeenverlies aan de aangedane zijde levert slechtere klinische resultaten op qua PROMS. Ook het revisiepercentages is verhoogd als er geen sprake is van bot-op-bot verlies (Knifsund, 2017; Pandit, 2011; Hamilton, 2017).

Een osteofyt van het contralaterale compartiment vormt geen contra-indicatie voor het plaatsen van een UKP, zolang de kraakbeendikte maar volledig is (Hamilton, 2017).

Een functioneel intacte VKB is met name van belang voor een mobile bearing UKP, voor een UKP met fixed bearing is dit minder strikt. Bovendien kan men door verandering van de slope/hellingshoek van de tibiacomponent de voor-achterwaardse stabiliteit verbeteren, of kan verandering van de slope/hellingshoek van de tibiacomponent de instabiliteit t.g.v. een insufficiënte VKB gecompenseerd worden (Adulkasem, 2019; Engh, 2014; Plancher, 2021).

Voor de Oxford UKP is een flexie van minimaal 110° (behaald onder narcose/spinaal) nodig om het femur te prepareren. Verder wordt een flexiecontractuur (extensiebeperking) van maximaal 15° aangehouden, ook vastgesteld onder narcose of spinaal (Berend, 2015).

Pre-operatieve anterieure pijn ten gevolge van patellofemorale artrose is geen contra-indicatie voor een unicompartimentele knie prothese, maar kan wel blijven bestaan na het plaatsen van een unicompartimentele prothese en moet preoperatief met de patient besproken worden. Specifiek voor een mediale mobile bearing UKP worden patellofemorale artrose van het laterale deel en subluxatie stand van de patella ten opzichte van trochlea als contra-indicaties beschreven. (Hamilton, 2017; Berend, 2015; Goodfellow, 1988; Beard, 2007; Pandit, 2011; Hamilton, 2017).

Verder zijn er in het verleden een aantal factoren geweest die gezien werden als contra-indicaties voor het plaatsen van een UKP, welke in recentere literatuur worden ontkracht. Zo zijn radiologische chondrocalcinose, leeftijd en BMI geen contra-indicaties meer voor het plaatsen van een UKP (Hamilton, 2017; Berend, 2015; Pandit, 2011; Hamilton, 2017; Musbahi, 2020). Bij de behandelbeslissing moeten de wensen van de patiënt in de overweging worden meegenomen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

Er zijn meerdere factoren die van invloed zijn of er gekozen wordt voor een UKP of een TKP. De wens van een patiënt is een belangrijk onderdeel in het shared decision making proces (samen beslissen). De behandelend orthopedisch chirurg zou hier dan ook actief naar moeten vragen. In overleg met de patiënt wordt dan een behandeling gekozen die het beste past bij de specifieke omstandigheden en de voorkeuren van de patiënt. Meestal is pijnreductie de belangrijkste reden om een operatie te ondergaan, maar ook andere wensen kunnen van belang zijn om voor een bepaald type prothese te kiezen. Zo kan een jonge, actieve patiënt eerder een voorkeur voor een UKP hebben, gezien de snellere revalidatie en de grotere mogelijkheid tot terugkeer naar werk en sport (Kievit, 2019; Witjes, 2016). Ook voor oudere patiënten kan er een voorkeur zijn voor een UKP, gezien het snellere herstel en minder risico’s op complicaties (Liddle, 2017). Echter het verhoogde risico op revisie op kortere termijn kan voor sommige patiënten de doorslag geven om voor een TKP te kiezen. Bij een andere indicatie dan primaire unicompartimentele artrose, zoals bij inflammatoire artritis wordt een TKP geadviseerd.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Literatuur over kosteneffectiviteit laat een voorkeur zien voor UKP in vergelijking met TKP. Zo laat de studie van Peersman (2014) zien dat er een kostenreductie is van €2807,- voor een UKP ten opzichte van TKP en een winst in QALY’s van 0,04. De kosteneffectiviteit was het hoogst in de oudere populatie. De kostenreductie zit met name in verminderd aantal ligdagen, goedkopere materialen, minder hulp in revalidatie (fysiotherapie) en minder complicaties. Dat dit effect hoger is bij de oudere groep patiënten komt door de verlaagde kans op een revisie bij oudere patiënten. Ook Beard (2019) concludeert in de TOPKAT trial dat een UKP meer kosteneffectief is dan een TKP na 5 jaar, waarbij de protheses vergelijkbare klinische uitkomsten en complicaties kenden. De winst van een UKP ten opzicht van een TKP was 0.240 QALY’s, en plaatsing van een UKP was gemiddeld £910 goedkoper, als gevolg van enigszins betere uitkomsten, lagere operatiekosten en lagere kosten voor nazorg. Hoewel de studie van Peersman (2014) voor een UKP een hogere kans op revisie vond in vergelijking met een TKP, vond Beard (2019) geen verschillen in revisie. Bovendien komt dit in absolute aantallen niet veel voor. Tevens is over het algemeen een revisie van een UKP simpeler en goedkoper, aangezien er meestal geconverteerd kan worden naar een standaard TKP. Een revisie van een TKP is een stuk duurder.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Bij unicompartimentele artrose heeft een conservatieve of gewrichtsparende behandeling de voorkeur. Echter als dit onvoldoende effect heeft en/of niet haalbaar is, kan een prothese overwogen worden. Daarbij heeft een UKP de voorkeur boven een TKP, echter de behandelend orthopedisch chirurg moet wel genoeg ervaring hebben. Hij/zij kan eventueel overwegen om de patiënt door te verwijzen naar een ander centrum waar die ervaring aanwezig is. Belangrijk blijft om de indicatie strikt te houden, ook als er gekozen wordt voor een UKP. Naar aanleiding van deze richtlijn bestaat de kans dat er meer UKP’s geplaatst gaan worden, dit moet goed gemonitord worden. Veel literatuur kijkt naar korte termijn resultaten (< 5 jaar), terwijl langetermijnresultaten van protheses heel belangrijk zijn.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Uit de literatuuranalyse komt geen duidelijk verschil naar voren in klinische uitkomsten tussen een UKP en TKP. Echter de revalidatie bij een UKP is sneller, de opnameduur korter en de kosten lager dan bij een TKP. Na een UKP zijn patiënten eerder weer aan het werk en sport, wat hun kwaliteit van leven ten goede komt. De indicatiestelling voor het plaatsen van een prothese moet echter, ook voor een UKP, strikt zijn. Een UKP wordt geplaatst bij een eindstadium symptomatische unicompartimentele artrose. Het verhoogde risico op een revisie na een UKP moet met de patiënt besproken worden, welke met name samenhangt met de ervaring van de orthopedisch chirurg en het volume van het behandelend ziekenhuis.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Voor unicompartimentele knieartrose zijn verschillende chirurgische behandelopties indien conservatieve behandeling onvoldoende effectief is. Het gebruik van een unicompartimentele knieprothese is er één van. In Nederland werden in 2018 25.569 totale knieprotheses (TKP) geplaatst, 4.011 unicompartimentele knieprotheses (UKP) en 181 patellofemorale protheses. Er bestaat een grote praktijkvariatie in het gebruik van type protheses, variërend van bijvoorbeeld geen UKP’s tot bijna 40% van het aantal knieprotheses (LROI). Verschillende factoren spelen hierbij mogelijk een rol zoals patiëntgebonden factoren (onder andere leeftijd, BMI, ASA classificatie en onderliggende inflammatoire pathologie), factoren gerelateerd aan arts en logistiek (onder andere kennis, voorlichting, training en beschikbaarheid van de prothese) en operatie gebonden factoren (prothese survival, complicaties, herstel van de ingreep). Een UKP vervangt alleen het aangedane symptomatische compartiment van de knie, met behoud van het niet aangedane compartiment en de kruisbanden. De procedure is minder invasief, met mogelijk minder complicaties in verhouding tot een TKP. Voorstanders van de UKP suggereren postoperatief een betere functie, een snellere revalidatie, kostenreductie en minder complicaties in verhouding tot een TKP. Het nadeel is het risico op ontstaan van symptomatische artrose in het behouden compartiment en daarmee een mogelijke revisie. Een TKP vervangt het hele kniegewricht, wat het risico op revisie operatie mogelijk reduceert. Beide opties hebben mogelijke voor,- en nadelen. Bij patiënten met symptomatische artrose van het gehele tibiofemorale gewricht is er over het algemeen consensus dat een TKP de voorkeur heeft.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether unicompartmental knee arthroplasty results in lower pain scores compared to total knee arthroplasty in patients with (unicompartmental) osteoarthritis of the knee.

Source: (Wilson, 2019) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether unicompartmental knee arthroplasty improves quality of life compared to total knee arthroplasty in patients with (unicompartmental) osteoarthritis of the knee.

Source: (Beard, 2019) |

|

Low GRADE |

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty does not seem to result in more favourable patient-reported function scores compared to total knee arthroplasty in patients with (unicompartmental) osteoarthritis of the knee.

Sources: (Wilson, 2019; Beard, 2019) |

|

Low GRADE |

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty seems to result in more favourable patient-reported combined pain and function scores compared to total knee arthroplasty in patients with (unicompartmental) osteoarthritis of the knee, but the difference is not clinically relevant.

Sources: (Wilson, 2019; Beard, 2019) |

|

Low GRADE |

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty does not seem to result in fewer complications (complications related to primary operation, postoperative complications, complications requiring readmission and venous thromboembolism) compared to total knee arthroplasty in patients with (unicompartmental) osteoarthritis of the knee.

Sources: (Wilson, 2019; Beard, 2019) |

|

Low GRADE |

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty does not seem to result in higher patient satisfaction compared to total knee arthroplasty in patients with (unicompartmental) osteoarthritis of the knee.

Sources: (Wilson, 2019; Beard, 2019) |

|

Low GRADE |

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty might result in lower reoperation rate compared to total knee arthroplasty in patients with (unicompartmental) osteoarthritis of the knee.

Sources: (Wilson, 2019; Beard, 2019) |

|

Low GRADE |

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty might lead to increased revision rates at 5 years, but reduced revision rates at 10 and 15 years compared to total knee arthroplasty in patients with (unicompartmental) osteoarthritis of the knee.

Sources: (Wilson, 2019; Beard, 2019) |

|

- GRADE |

The outcome return to work was not described in the selected literature. |

|

- GRADE |

The outcome return to sport was not described in the selected literature. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Wilson (2019) wrote a systematic review using data from randomized controlled trials, nationwide databases or joint registries, and large cohort studies. The seven RCTs included in this review were used for the analysis. In addition, the UK multicenter RCT from Beard (2019) was included, in which the 5-year outcomes in patients with medial compartment osteoarthritis from the TOPCAT study were described. This was an update of the study by Beard (2017) reported in the SR. Duplicate (older) results of these studies were removed during data pooling where appropriate.

Results

Pain (crucial)

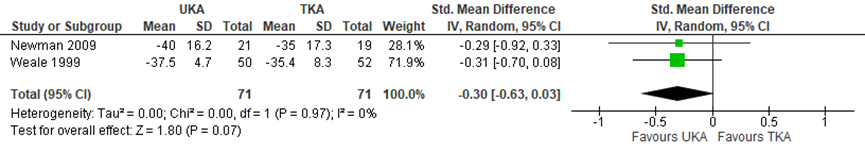

Pain was reported by Wilson (2019) based on 2 studies, using pain specific scores or the pain element of a larger combined patient reported outcome measure (PROM) score, collected at various time points after the operation. Follow-up was not specified. The difference was presented as a standardized mean difference (SMD), because the different studies used different scales to report the outcome. As depicted in figure 1, the SMD of the 2 studies describing pain after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) or total knee arthroplasty (TKA) was -0.30 with a 95% confidence interval (CI) from -0.63 to 0.03, with 71 patients in both groups. This difference was not clinically relevant.

Figure 1 Pain after UKA versus TKA

Pain specific scores or the pain element of a larger combined patient reported outcome measure score; random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value van pooled effect; UKA: unicompartmental knee arthroplasty; TKA: total knee arthroplasty; source: Wilson, 2019

Level of evidence

The level of evidence for the outcome “pain” started at high, as it was based on randomized controlled trials, but was downgraded by 3 levels to very low due to study limitations (high risk of bias), the limited study population size and the fact that the confidence interval crossed the limit of clinical decision-making (both imprecision).

Quality of life (crucial)

Quality of life was not described in the systematic review, but the RCT by Beard (2019) reported both the EQ-5D-3L and the EQ-5D VAS after 5 years. In 224 patients with UKA and 212 patients with TKA, EQ-5D-3L (mean±SD) was 0.744±0.29 and 0.717±0.32, respectively, with a difference of 0.03 and a 95% CI from -0.03 to 0.08, favouring UKA. The EQ-5D VAS was improved in UKA (75.4±16.5) compared to TKA (71.7±19.7), with a difference of 3.70 (95% CI 0.32 to 7.08). These differences were not clinically relevant.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence for the outcome “quality of life” started at high, as it was based on a RCT, but was downgraded by 3 levels to very low due to study limitations (high risk of bias), the limited study population size and the fact that the confidence interval crossed the limit of clinical decision-making (both imprecision).

Function (important)

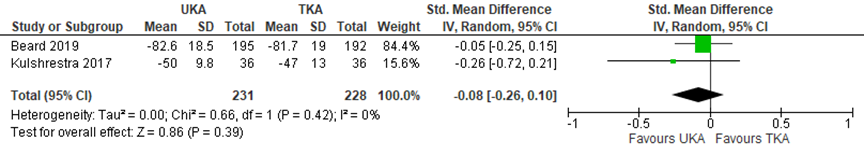

The outcome “function”, measured using function-specific and function components of knee-specific PROMs, was reported in 2 studies for 231 patients receiving UKA and 228 patients receiving TKA. Beard (2019) reported the American Knee Society score (functional), whereas 1 study preresented by Wilson (2019) reported the Knee Outcome Scale - Activity of Daily Living Scale. The difference was not clinically relevant with a SMD of -0.08 (95% CI -0.26 to 0.10) in favour of UKA, as presented in figure 2. Beard (2019) used a follow-up of 5 years, Wilson (2019) did not specify the time frame.

Figure 2 Function after UKA versus TKA

Function-specific and function components of knee specific patient reported outcome measure score with a maximum score of 100; random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect; UKA: unicompartmental knee arthroplasty; TKA: total knee arthroplasty; sources: Wilson, 2019; Beard, 2019

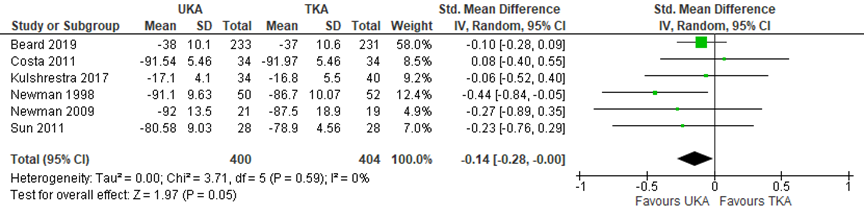

Several studies reported a combined pain and function score based on PROMS, including the Oxford knee score (OKS), Bristol knee score, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities index (WOMAC), Knee Society score, and the Japanese Orthopaedic Association score. The SMD (figure 3) described in 6 RCTs with 400 UKA patients versus 404 TKA patients was -0.14 (95% CI -0.28 to 0.00) in favour of UKA. Follow-up of the different studies was not specified. The difference was not clinically relevant. Beard (2019) performed an additional analysis of function (OKS 5 years postoperative) after TKA versus UKA making subgroups for age (< 55; 55 to 70; > 70), but found no differences between the age groups.

Figure 3 Combined pain and function after UKA versus TKA

Combined patient reported outcome measure scores including the Oxford knee score, Bristol knee score, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities index, Knee Society score, and the Japanese Orthopaedic Association score; random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value van pooled effect; UKA: unicompartmental knee arthroplasty; TKA: total knee arthroplasty; sources: Wilson, 2019; Beard, 2019

Level of evidence

The level of evidence for the outcomes “function” and “pain and function combined” started at high, as it was based on randomized clinical trials, but was downgraded by 2 levels to low because of study limitations (high risk of bias) and limited study population size (imprecision).

Complications (important)

Several complications were described in the SR by Wilson (2019) and the RCT by Beard (2019). Categories made by the studies were followed and results were described as risk difference. The event rate of complications was low and no clinically relevant differences were found between the treatment groups. After five years, Beard (2019) reported 1/264 (0.4%) complications related to primary operation for UKA, versus 2/264 (0.7%) for TKA (risk difference 0.00, 95% CI -0.02 to 0.01). In addition, 10/264 (3.8%) postoperative complications were reported in both groups (risk difference 0.00, 95% CI -0.03 to 0.03). The same study found readmission was required in 3/264 (1.1%) cases for UKA, versus 9/264 (3.4%) for TKA (risk difference -0.02, 95% CI -0.05 to 0.00). Wilson (2019) reported incidence of venous thromboembolism in one study, with 1/50 for UKA and 5/52 for TKA (risk difference -0.08, 95% CI -0.17 to 0.01).

Level of evidence

The level of evidence for the outcome “complications” started at high, as it was based on randomized clinical trials, but was downgraded by 2 levels to low due to the very low number of events (imprecision).

Patient satisfaction (important)

Beard (2019) reported patient satisfaction with self-reported anchor questions 5 years after intervention in 458 patients and found no clinically relevant differences between the groups. 190/233 (82%) of patients receiving UKA were satisfied with their knees compared with 173/225 (77%) patients receiving TKA, resulting in a risk ratio of 1.06 with a 95% CI from 0.99 to 1.13. In addition, 219/230 (95%) of patients with UKA reported their knee was better after surgery, versus 200/222 (90%) of patients with TKA (RR 1.06, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.11). Lastly, 208/228 (91%) UKA patients would choose to have the knee operation again; in the TKA group, this was true for 183/217 (84%) patients (RR 1.08, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.15).

Level of evidence

The level of evidence for the outcome “patient satisfaction” started at high, as it was based on randomized clinical trials, but was downgraded by 2 levels to low because of study limitations (high risk of bias) and the limited study population size (imprecision).

Implant survival (important)

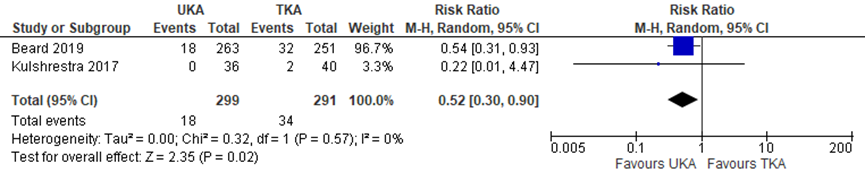

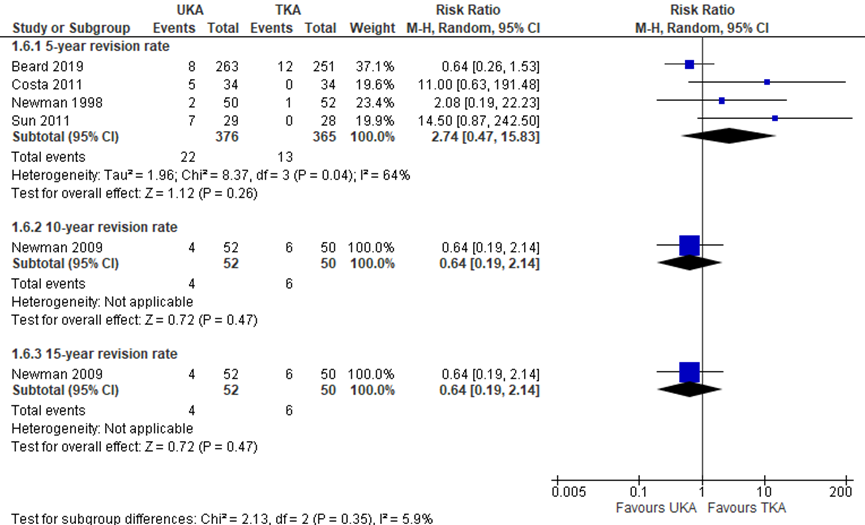

Reoperation and implant revision were used as measures for implant survival. Both were described separately in several RCTs. Based on 2 studies, the risk of reoperation was lower for 299 UKA patients compared to 291 TKA patients, with a RR of 0.52 (95% CI 0.30 to 0.90), as presented in figure 4. The revision rate was not consitstent between the different time points, as depicted in figure 5. At 5 years, there was a RR of 2.74 (95% CI 0.47 to 15.83) in 4 studies describing 741 patients in total (UKA 376, TKA 365), favouring TKA. At 10 and 15 years, 1 study describing 102 patients (UKA 52, TKA 50) found a RR of 0.64 (95% CI 0.19 to 2.14) at both time points, favouring UKA. These differences were clinically relevant.

Figure 4 Risk of reoperation after UKA versus TKA

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value van pooled effect; UKA: unicompartmental knee arthroplasty; TKA: total knee arthroplasty; sources: Wilson, 2019 (follow-up unknown); Beard, 2019 (follow-up 5 years)

Figure 5 Risk of revision after UKA versus TKA

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value van pooled effect; UKA: unicompartmental knee arthroplasty; TKA: total knee arthroplasty; sources: Wilson, 2019; Beard, 2019

Level of evidence

The level of evidence for the outcome “risk of reoperation” started high, as it was based on randomized clinical trials, but was downgraded by 2 levels to low because of limited study population size and the fact that the confidence interval overlapped with the limit for clinical decision-making (both imprecision). The level of evidence for the outcome “risk of revision” was downgraded by 2 levels to low, because of the limited study population size and the fact that the confidence interval overlapped with the limit for clinical decision-making (both imprecision).

Return to work and sport (important)

The outcomes “return to work” and “return to sport” were not described in randomized studies.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the (non)-effectiveness of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty compared to total knee arthroplasty in the treatment of unicompartmental knee osteoarthritis?

P: patients with (unicompartmental) osteoarthritis of the knee;

I: unicompartmental knee arthroplasty;

C: total knee arthroplasty;

O: pain, quality of life, function, complications, patient satisfaction, implant survival, return to work/sport.

Relevant outcomes

The guideline development group considered pain and quality of life to be critical outcomes for decision-making; and function, complications, patient satisfaction, implant survival, cost reduction and return to work/sport to be important outcomes for decision-making.

The working group did not define the outcome measures listed above a priori but used the definitions used in the studies. The working group defined 25% as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for dichotomous outcomes, 5 points for the Oxford knee score (OKS), 10% for VAS scales and PROM scores (Pijls, 2011), and 0.5 for standardized mean differences (SMD).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until October 21, 2019. The detailed search strategy is outlined in the Methods section. The systematic literature search resulted in 681 hits, including systematic reviews (SRs), randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies. SRs and RCTs were subjected to title and abstract screening. Observational studies were only considered in case no data from randomized studies could be found. The full texts of 16 papers were evaluated for inclusion. After reading the full text, 14 articles were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 2 articles were included.

Results

One systematic review and one RCT were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Adulkasem N, Rojanasthien S, Siripocaratana N, Limmahakhun S. Posterior tibial slope modification in osteoarthritis knees with different ACL conditions: Cadaveric study of fixed-bearing UKA. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2019 May-Aug;27(2):2309499019836286. doi: 10.1177/2309499019836286. PMID: 30894072.

- Beard DJ, Pandit H, Ostlere S, Jenkins C, Dodd CA, Murray DW. Pre-operative clinical and radiological assessment of the patellofemoral joint in unicompartmental knee replacement and its influence on outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007 Dec;89(12):1602-7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B12.19260. PMID: 18057360.

- Beard DJ, Davies LJ, Cook JA, MacLennan G, Price A, Kent S, Hudson J, Carr A, Leal J, Campbell H, Fitzpatrick R, Arden N, Murray D, Campbell MK; TOPKAT Study Group. The clinical and cost-effectiveness of total versus partial knee replacement in patients with medial compartment osteoarthritis (TOPKAT): 5-year outcomes of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019 Aug 31;394(10200):746-756. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31281-4. Epub 2019 Jul 17. PMID: 31326135; PMCID: PMC6727069.

- Berend KR, Berend ME, Dalury DF, Argenson JN, Dodd CA, Scott RD; Consensus Statement on Indications and Contraindications for Medial Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2015; 24(4):252-256.

- Chawla H, van der List JP, Christ AB, Sobrero MR, Zuiderbaan HA, Pearle AD. Annual revision rates of partial versus total knee arthroplasty: A comparative meta-analysis. Knee. 2017 Mar;24(2):179-190. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2016.11.006. PMID: 27916580.

- Engh GA, Ammeen DJ. Unicondylar arthroplasty in knees with deficient anterior cruciate ligaments. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014 Jan;472(1):73-7. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-2982-y. PMID: 23572351; PMCID: PMC3889418.

- Goodfellow JW, Kershaw CJ, Benson MK, O'Connor JJ. The Oxford Knee for unicompartmental osteoarthritis. The first 103 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988 Nov;70(5):692-701. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.70B5.3192563. PMID: 3192563.

- Hamilton T, Choudhary R, Jenkins C, Mellon S, Dodd C, Murray D, Pandit H. Lateral osteophytes do not represent a contraindication to medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a 15-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017 Mar;25(3):652-659. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4313-9.

- Hamilton T, Pandit HG, Inabathula A, Ostlere SJ, Jenkins C, Mellon SJ, Dodd C, Murray D. Unsatisfactory outcomes following unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in patients with partial thickness cartilage loss: a medium-term follow-up. Bone Joint J. 2017 Apr;99-B(4):475-482. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.99B4.BJJ-2016-1061.R1

- Hamilton T, Pandit H, Jenkins C, Mellon S, Dodd C, Murray D. Evidence-Based Indications for Mobile-Bearing Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty in a Consecutive Cohort of Thousand Knees. J Arthroplasty. 2017 Jun;32(6):1779-1785. Doi:10.1016/j.arth.2016.12.036. Epub 2016 Dec 27.

- Howieson A, Farrington W. Unicompartmental knee replacement in the elderly: a systematic review. Acta Orthop Belg. 2015 Dec;81(4):565-71. PMID: 26790776.

- Kievit AJ, Kuijer PPFM, de Haan LJ, Koenraadt KLM, Kerkhoffs GMMJ, Schafroth MU, van Geenen RCI. (2019) Patients return to work sooner after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty than after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 30. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05667-0.

- Kleeblad LJ, van der List JP, Zuiderbaan HA, Pearle AD. Larger range of motion and increased return to activity, but higher revision rates following unicompartmental versus total knee arthroplasty in patients under 65: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018 Jun;26(6):1811-1822. doi: 10.1007/s00167-017-4817-y. Epub 2017 Nov 28. PMID: 29185005.

- Knipfsund J, Hatakka J, Keemu H, Mäkelä K, Koivisto M, Niinimäki T. Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasties are Performed on the Patients with Radiologically Too Mild Osteoarthritis. Scand J Surg. 2017 Dec;106(4):338-341. doi: 10.1177/1457496917701668.

- Liddle AD, Judge A, Pandit H, Murray DW. (2014) Determinants of revision and functional outcome following unicompartmental knee replacement. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 22(9), 1241-50.

- Liddle AD, Pandit H, Judge A, Murray DW. (2016) Effect of Surgical Caseload on Revision Rate Following Total and Unicompartmental Knee Replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 98(1), 1-8.

- Mushabi O, Hamilton T, Crellin A, Mellon S, Kendrick B, Murray D. The effect of obesity on revision rate in unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020 Oct 16. doi: 10.1007/s00167-020-06297-7

- National Joint Registry. 15th annual report. Hertfordshire. 2018. Available from: http://www.njrreports.org.uk/Portals/0/PDFdownloads/NJR%2015th%20Annual%20Report%202018.pdf.

- Newman J, Pydisetty RV, Ackroyd C. Unicompartmental or total knee replacement: the 15-year results of a prospective randomised controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009 Jan;91(1):52-7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B1.20899. Erratum in: J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009 May;91(5):701. PMID: 19092004.

- Pandit H, Gulati A, Jenkins C, Barker K, Price AJ, Dodd C, Murray D. Unicompartmental knee replacement for patients with partial thickness cartilage loss in the affected compartment. Knee 2011 Jun;18(3):168-71. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2010.05.003

- Pandit H, Jenkins C, Gill H, Smith G, Price A, Dodd C, Murray D. Unnecessary contraindications for mobile-bearing unicompartmental knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011 May;93(5):622-8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B5.26214.

- Peersman G, Jak W, Vandenlangenbergh T, Jans C, Cartier P, Fennema P. Cost-effectiveness of unicondylar versus total knee arthroplasty: a Markov model analysis. Knee. 2014;21 Suppl 1:S37-42. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0160(14)50008-7. PMID: 25382367.

- Pijls BG, Dekkers OM, Middeldorp S, Valstar ER, van der Heide HJ, Van der Linden-Van der Zwaag HM, Nelissen RG. AQUILA: assessment of quality in lower limb arthroplasty. An expert Delphi consensus for total knee and total hip arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011 Jul 22;12:173. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-173. PMID: 21781327; PMCID: PMC3155910.

- Plancher KD, Shanmugam JP, Brite JE, Briggs KK, Petterson SC. Relevance of the Tibial Slope on Functional Outcomes in ACL-Deficient and ACL Intact Fixed-Bearing Medial Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2021 May 5:S0883-5403(21)00413-7. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2021.04.041. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34053751.

- Tuecking LR, Savov P, Richter T, Windhagen H, Ettinger M. (2020) Clinical validation and accuracy testing of a radiographic decision aid for unicondylar knee arthroplasty patient selection in midterm follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. doi: 10.1007/s00167-020-05912-x.

- van Oost I, Koenraadt KLM, van Steenbergen LN, Bolder SBT, van Geenen RCI. Higher risk of revision for partial knee replacements in low absolute volume hospitals: data from 18,134 partial knee replacements in the Dutch Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2020 Aug;91(4):426-432. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2020.1752017. Epub 2020 Apr 14. PMID: 32285723.

- Wilson HA, Middleton R, Abram SGF, Smith S, Alvand A, Jackson WF, Bottomley N, Hopewell S, Price AJ. Patient relevant outcomes of unicompartmental versus total knee replacement: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019 Feb 21;364:l352. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l352. Erratum in: BMJ. 2019 Apr 2;365:l1032. PMID: 30792179; PMCID: PMC6383371.

- Witjes S, Gouttebarge V, Kuijer PP, van Geenen RC, Poolman RW, Kerkhoffs GM. (2016) Return to Sports and Physical Activity After Total and Unicondylar Knee Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 46(2), 269-92.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Research question: What are the indications for unicompartimental arthroplasty compared to total arthroplasty?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Wilson, 2019 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs / cohort / case-control studies

Literature search up to December 2018

RCTs A: Beard, 2017 B: Costa, 2011 C: Kulshrestha, 2017 D: Newman, 1998 E: Newman, 2009 F: Sun, 2012 G: Weal, 1999

Cohort studies H: Foote, 2008 I: Ho, 2016 J: Lombardi, 2009

Study design: RCT and cohort studies (only in case an outcome was not described in RCTs)

Setting and Country: Oxford University hospitals.

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: No separate funding was supplied for this study. Institutional funding from Arthritis Research UK and National Institute for Health Research Oxford Biomedical Research Centre; the researchers and funders were independent; AJP has received research grants from Zimmer-Biomet, and personal consultancy fees from Zimmer Biomet and Depuy; WFJ has received personal consultancy fees from Zimmer-Biomet; NB has received support from Zimmer- Biomet for educational consultancy and lectures. |

Inclusion criteria SR: Studies published in the past 20 years, comparing outcomes of primary UKA with TKA in adult patients.

Exclusion criteria SR: conference abstracts and case reports unless they had subsequently been published as full articles; Studies with fewer than 50 participants, or if translation into English was not available.

60 studies included, of which 7 RCTs

N, mean age, male A: 528, 65y, 42% B: 68, 73y, 31% C: 72, 61y, 22% D: 102, 70y, 36% E: 102, 70y, 36% F: 28, 61y, 39% G: 102, 70y, 36% Groups comparable at baseline

H: 72, 53y, 44% not matched I: 76, 60y, 32%, not matched J: 206, 62y, 37%, matched for age, sex, BMI and OA |

A: UKA B: UKA C: UKA (bilateral simultaneous procedures) D: UKA E: UKA F: UKA G: UKA

H: UKA I: UKA J: UKA

|

A: TKA B: TKA C: TKA

D: TKA E: TKA F: TKA G: TKA

H: TKA I: TKA J: TKA

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: 1 year B: 5 years C: 2 years D: 5 years E: 15 years F: 4 years G: 5 years

H: 6 months I: 1 year J: 30 months

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) Not reported

|

Pain Pain specific and pain components of knee specific PROM scores. Std. mean difference (95% CI): E: -0.29 (-0.92, 0.33) G: -0.31 (-0.70, 0.08)

Pooled effect (random effects model): -0.30 (-0.63, 0.03) favoring UKA. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Function Function specific and function components of knee specific PROMs. Std. mean difference (95% CI): A: -0.10 (-0.28, 0.07) C: -0.17 (-1.60, 1.25) C (2):-0.26 (-0.72, 0.21) Pooled effect (random effects model): -0.12 (-0.29, 0.04) favoring UKA. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Complications Myocardial ischemic events A: UKA 0/260, TKA 1/260 0.33 (0.01, 8.14)

Cerebrovascular events Not reported in RCTs.

Venous thromboembolism A: UKA 0/264, TKA 1/248 D: UKA 1/50, TKA 5/52 RR 0.24 (0.04, 1.37)

Deep infection A: UKA 0/260, TKA 0/248 RR not estimable

All complications pooled: UKA 1/834 TKA 7/808 RR 0.26 (0.05, 1.19) favouring UKA. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Reoperation A: UKA 0/36, TKA 2/40 C: UKA 6/260, TKA 7/260 RR 0.73 (0.27, 2.02) favouring UKA. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Revision 5 year B: UKA 5/34, TKA 0/34 D: UKA 2/50, TKA 1/52 F: UKA 7/29, TKA 0/28 RR 5.95 (1.29, 27.52) favouring TKA. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

10 year D: UKA 4/52, TKA 6/50 RR 0.64 (0.19, 2.14)

15 year D: UKA 4/52, TKA 6/50 RR 0.64 (0.19, 2.14)

Return to work (cohort studies) in weeks H: -1.00 (-1.36, -0.64) J: -0.20 (-1.73, 1.33) Pooled effect (random effects model): -0.96 (-1.31, -0.61). Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Return to sport (cohort studies) in weeks I:-8.00 (-9.96, -6.04) J: 0.40 (-2.39, 3.19) Pooled effect (random effects model): -3.86 (-12.09, 4.37). Heterogeneity (I2): 96% |

|

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, case series))1

Research question: What are the indications for unicompartimental knee arthroplasty compared to total knee arthroplasty?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Beard, 2019 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Multicentre RCT at 27 UK sites.

Funding and conflicts of interest: The TOPKAT study is funded by the NIHR HTA Programme (number HTA 08/14/08), sponsored by the University of Oxford, and supported by Oxford Surgical Intervention Trials Unit (SITU; supported by Oxford NIHR Biomedical Research Centre) in the Royal College of Surgeons Surgical Trials Initiative. DJB reports institutional research grant funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and Zimmer Biomet, outside the submitted work. JAC reports grants from the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme and was a member of the NIHR HTA efficient trial designs board for 2 years, during the conduct of the study. GM reports grants from NIHR HTA, during the conduct of the study. AP reports consultancy fees from Zimmer Biomet, DePuy Synthes, and Smith & Nephew, and grants from NIHR and AR United Kingdom, outside the submitted work. HC reports grants from NIHR, during the conduct of the study. RF reports membership of the HTA Prioritisation Group and HTA National Stakeholder Advisory Group. NA reports grants from Merck and consultancy fees from Merck, Flexion Therapeutics, Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Eli Lilly, outside the submitted work. DM reports grants and personal fees from Zimmer Biomet, outside the submitted work. DM also reports receiving royalties related to The Oxford Partial Knee system (by Zimmer Biomet), and from other patents relating to knee replacement. All other authors declare no competing interests. |

Inclusion criteria: Medial compartment osteoarthritis with exposed bone on both femur and tibia; Functionally intact anterior cruciate ligament (superficial damage or splitting is acceptable); Full thickness and good quality lateral cartilage present; Correctable intra-articular varus deformity (suggestive of adequate medial collateral ligament function); Medically fit showing an ASA of 1 or 2.

Exclusion criteria: Require revision knee replacement surgery; Have rheumatoid arthritis or other inflammatory disorders; Are unlikely to be able to perform required clinical assessment tasks; Have symptomatic foot, hip or spinal pathology; Previous knee surgery other than diagnostic arthroscopy and medial menisectomy; Previously had septic arthritis; Have significant damage to the patella-femoral joint especially on the lateral facet.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 232 Control: 238

Important prognostic factors2: Age I: 65.2±8.8 C: 64.7±8.5

Male sex I: 58% C: 58%

Left knee I: 53% C: 53%

Osteoarthritis duration: I: 28% <3 years; 14% >10 years C: 28% <3 years; 11% >10 years

BMI I: 31.0±4.6 C: 31.1±4.8

OKS at baseline I: 18.8±7.0 C: 19.0±7.2

EQ-5D VAS at baseline I: 62.8±27.0 C: 60.7±28.7

|

Partial knee replacement / unicompartimental knee arthroplasty (UKA)

Only the diseased area of the joint was replaced by artificial implants, whereas healthy compartments of the knee and ligaments were retained.

Surgeons were free to use the implant of their own choice, or that of their institution.

|

Total knee replacement / total knee arthroplasty (TKA)

All surfaces of the knee were replaced. The procedure involved excising both diseased and normal femoral condyles, the tibial plateau—and often the patella—and removing or releasing some of the ligaments. The artificial implant can be cemented in position.

Surgeons were free to use the implant of their own choice, or that of their institution.

|

Length of follow-up: 5 years

Loss-to-follow-up (5 years): Intervention: 18 did not respond; 6 died; 5 withdrawn

Control: 11 did not respond; 11 died; 10 withdrawn.

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: Missing EQ-5D at 5 years 33/264 (13%) Control: Missing EQ-5D at 5 years 41/264 (16%) |

Quality of life (primary outcome) EQ-5D-3L UKA 0.744±0.29 (n=224) TKA 0.717±0.32 (n=212) Mean difference 0.03 (-0.03, 0.08) favouring UKA

EQ-5D VAS UKA 75.4±16.5 (n=228) TKA 71.7±19.7 (n=217) Mean difference 3.70 (0.32, 7.08) favouring UKA.

Function American Knee Society score (functional) UKA 82.6±18.5 (n=195) TKA 81.7±19 (n=192) Mean difference -0.90 (-4.64, 2.84) favouring UKA.

Patient satisfaction Oxford knee score UKA 38±10.1 (n=233) TKA 37±10.6 (n=231) Mean difference -1.00 (-2.88, 0.88) favouring UKA.

Reoperations UKA 18/263 (7%) TKA 32/251 (13%)

Revisions UKA 10/245 (4%) TKA 10/269 (4%)

Complications Related to primary operation UKA 1/264 (0.4%) TKA 2/264 (0.7%) risk difference 0.00, 95% CI -0.02 to 0.01

Post-operative UKA 10/246 (3.8%) TKA 19/269 (7.1%) risk difference 0.00, 95% CI -0.03 to 0.03

Required readmission UKA 3/264 (1.2%) TKA 9/264 (3.3%) risk difference -0.02, 95% CI -0.05 to 0.00 |

|

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures.

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors ((potential) confounders).

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls.

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders.

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Research question: What are the indications for unicompartimental knee arthroplasty compared to total knee arthroplasty?

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Wilson, 2019 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

N/A |

Yes |

Yes |

Unclear |

Unclear |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined.

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched.

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons.

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported.

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs).

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table et cetera).

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (for example Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (for example funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (for example Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

Research question: What are the indications for unicompartimental knee arthroplasty compared to total knee arthroplasty?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome accessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Beard, 2019 |

Participants were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive unicompartimental knee arthroplasty or total knee arthroplasty. For the randomisation procedure (in which we also used minimisation), we used a web-based randomisation service at the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials. We also used a minimisation algorithm that incorporated sex, age band (<50, 50–70, or >70 years), baseline Oxford Knee Score (OKS) band (14 or less, 15–21, or 22 or more), and delivery unit. A delivery unit was either an equipoise surgeon or a pair of expertise surgeons with complementary expertise. |

Unclear.

Surgeons, patients, and follow-up assessors were not masked to allocation, but the implant type was not highlighted at any stage. |

Likely.

Surgeons, patients, and follow-up assessors were not masked to allocation, but the implant type was not highlighted at any stage.

Preference to one of the interventions cannot be excluded. |

Unclear.

Surgeons, patients, and follow-up assessors were not masked to allocation, but the implant type was not highlighted at any stage. |

Unlikely.

Surgeons, patients, and follow-up assessors were not masked to allocation, but the implant type was not highlighted at any stage.

The crucial outcomes are patient reported and therefore affected by (lack of) blinding. |

Unlikely.

The detailed study design and protocol have been published previously. |

Unlikely.

Loss to follow-up similar between treatment groups. |

Unlikely. |

- Randomisation: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomisation process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomisation (performed at a site remote from trial location) or sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomisation procedures or open allocation schedules.

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments. The outcome assessor records the study results. Blinding of those assessing outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignement influences the proces of outcome assessment (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available, then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, then outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups, bias is likely. If the number of patients lost to follow-up, or the reasons why, are not reported, the risk of bias is unclear.

- Participants included in the analysis are exactly those who were randomized into the trial. If the numbers randomized into each intervention group are not clearly reported, the risk of bias is unclear; an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Ariracharan, 2015 |

Described studies overlap with other SR |

|

Brown, 2012 |

Not randomized |

|

Chawla, 2017 |

Only observational studies |

|

Griffin, 2007 |

Described studies overlap with other SR |

|

Howieson, 2015 |

Review, insufficient detail of included studies |

|

Isaac, 2007 |

Not randomized |

|

Kleeblad, 2017 |

SR of UKA and TKA but not comparative |

|

Migliorini, 2018 |

Described studies overlap with other SR |

|

Newman, 2009 |

Included in SR |

|

Kulshrestha, 2017 |

Included in SR |

|

Longo, 2015 |

Only observational studies |

|

Rodriguez-Merchan, 2014 |

Quality of included studies unclear |

|

Witjes, 2016 |

Only observational studies |

|

Zhang, 2010 |

Only observational studies |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 30-09-2021

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

De richtlijn is ontwikkeld in samenwerking met:

- Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap voor Fysiotherapie

- Patiëntenfederatie Nederland

- ReumaNederland

- Nationale Vereniging ReumaZorg Nederland

Doel en doelgroep

Doel

Het doel van de richtlijn is het beschrijven de gewenste diagnostiek en behandeling voor patiënten die lijden aan unicompartimentele artrose van de knie, gebaseerd op de meest actuele literatuur, ervaringen van patiënten en experts uit het veld.

Doelgroep

Deze richtlijn is bestemd voor alle zorgverleners die betrokken zijn bij de behandeling van patiënten met geïsoleerde mediale of laterale knieartrose. De richtlijn informeert ook de patiënt zodat deze samen met de arts een besluit kan nemen over de behandeling.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met geïsoleerde mediale of laterale artrose van de knie.

Werkgroep

- Dr. R.W. Brouwer, orthopedisch chirurg in Martini ziekenhuis Groningen, NOV (voorzitter)

- Dr. R.C.I. van Geenen, orthopedisch chirurg in Amphia Ziekenhuis, NOV

- Drs. A. Goud, orthopedisch chirurg in Diakonessenhuis, NOV

- Dr. N. van Egmond, orthopedisch chirurg in UMC Utrecht, NOV

- Prof. dr. S.M.A. Bierma-Zeinstra, hoogleraar artrose en gerelateerde aandoeningen in Erasmus MC, NOV

- Drs. T.W.G.M. Meys, radioloog in Martiniziekenhuis, NVvR

- Dr. J.T. Wegener, anesthesioloog-pijnspecialist in Sint Maartenskliniek, NVA

- Dr. M. van der Esch, senior onderzoeker/fysiotherapeut/epidemioloog in Reade en hoofddocent/lector Hogeschool van Amsterdam, KNGF

- N. Lopuhaä, beleidsmedewerker Patiëntbelangen, ReumaNederland

- M. Frediani-Bolwerk, patiëntpartner Nationale Vereniging ReumaZorg Nederland

- Drs. P. Pennings, beleidsmedewerker Communicatie & Participatie, Nationale Vereniging ReumaZorg Nederland

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. M.S. (Matthijs) Ruiter, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. S.N. (Stefanie) Hofstede, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Brouwer (voorzitter) |

Orthopedisch chirurg Martiniziekenhuis

|

Medische staf FC Groningen (betaald), ODEP member (onbetaald), bestuurslid DKS (onbetaald) COIC (onbetaald) Bestuurslid WAR (betaald). |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van Geenen |

Orthopedisch chirurg Amphia Ziekenhuis |

Consultant Zimmer Biomet (betaald), Secretaris werkgroep knie/Dutch Knee Society (onbetaald) |

De orthopedische onderzoekstichting FORCE ontvangt gelden van verschillende industriële partners (Mathys, Stryker, Zimmer Biomet) |

Geen auteur van uitgangsvragen met betrekking tot keuze van prothese |

|

Frediani-Bolwerk |

Patiëntvertegenwoordiger |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Patricia Pennings |

Beleidsmedewerker Communicatie & Participatie bij Nationale Vereniging ReumaZorg Nederland. |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van der Esch |

Senior onderzoeker/fysiotherapeut/epidemioloog in Reade, centrum voor revalidatie en reumatologie te Amsterdam; Hoofddocent/lector Hogeschool van Amsterdam, faculteit gezondheid. |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Meys |

Radioloog Martini Ziekenhuis Groningen met aandachtsgebied musculoskeletaal |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Lopuhaä |

Beleidsmedewerker Patiëntenbelangen ReumaNederland |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van Egmond |

Orthopedisch chirurg, UMC Utrecht |

Geen |

In het UMC Utrecht is kniedistractie ontwikkeld, daar is een spin-off bedrijf uit voortgekomen (arthrosave), welke nu zelfstandig is en geen relatie meer heeft met UMC Utrecht. Persoonlijk ben ik niet betrokken bij de ontwikkeling hiervan, maar UMC Utrecht is wel expertise centrum. |

Geen actie |

|

Bierma-Zeinstra |

Hoogleraar artrose en gerelateerde aandoeningen, Erasmus MC |

Associate editor Osteoarthritis & Cartilage (betaald), Commisielid Swedisch Research Council - clinical studies (onbetaald), Ethical board OARSI (onbetaald), Scientific advisory board Arthritis UK Pain Centre Nottingham University (onbetaald), Commissielid Annafonds (onbetaald), Editorial board member Maturitas (onbetaald), |

Ik heb meerdere subsidies voor epidemiologisch en klinisch artrose onderzoek van ZonMW, CZ, Europesche Unie, Foreum, en ReumaNederland. |

Geen actie |

|

Goud |

Orthopedisch chirurg Diakonessenhuis |

Bestuurslid Dutch knee society, (onbetaald), Bestuurslid Nederlandse vereniging voor Arthroscopy, (onbetaald). |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Wegener |

Anesthesioloog-Pijnspecialist |

Instructuur DARA (betaald), Examinator EDRA (onkostenvergoeding), Course Director ESRA Instructor Course (onkostenvergoeding), Lid ledenraad NVA sectie Pijn (geen onkostenvergoeding). |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Hofstede |

Senior adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Ruiter |

Adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van diverse patiëntorganisaties voor de Invitational conference. Het verslag hiervan (zie bijlagen) is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. Gedurende de richtlijnontwikkeling zaten vertegenwoordigers van ReumaNederland en Nationale Vereniging ReumaZorg Nederland in de werkgroep. Er is verder specifiek een module gewijd aan patiëntvoorlichting en communicatie. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de patiëntorganisaties die ook waren uitgenodigd voor de Invitational conference en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met geïsoleerde mediale of laterale artrose van de knie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door ReumaNederland en Nationale Vereniging ReumaZorg Nederland via de Invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen in de bijlagen.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE-gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende wetenschappelijke verenigingen en patiëntorganisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

September 4, 2019

|

Database |

Zoektermen |

Totaal |

|

Medline (OVID)

1997 – sep 2019

|