Adjuvante systemische behandeling

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van adjuvante systemische behandeling bij patiënten met galweg- of galblaascarcinoom na chirurgische resectie?

Aanbeveling

Geef geen adjuvante behandeling na een in opzet curatieve resectie van een galweg- of galblaascarcinoom.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

De Cochrane review van Luvira (2021) includeerde vier RCT’s waarin een vergelijking werd onderzocht tussen patiënten die wel of geen adjuvante systemische chemotherapie kregen na een resectie met curatieve intentie van galweg- en galblaaskanker. Vooral op 5-FU of gemcitabine gebaseerde behandelschema’s zijn onderzocht, gezien de ervaring met deze behandelingen in de palliatieve setting. Voor beide cruciale uitkomstmaten, overleving en kwaliteit van leven, werd informatie gerapporteerd.

De 1e RCT vergeleek mitomycine C + 5-FU met observatie in 139 patiënten met galwegcarcinoom en 140 patiënten met galblaascarcinoom (Takada, 2002). Voor galblaascarcinoom was de 5-jaars overleving beter met adjuvante chemotherapie; 26,0% versus 14,4% (p=0,04). Voor galwegcarcinoom was er geen verschil in 5-jaars overleving; 26,7% versus 24,1%. De 2e RCT vergeleek gemcitabine met observatie in 225 patiënten met perihilair cholangiocarcinoom (pCCA) of distaal cholangiocarcinoom (dCCA) (Ebata, 2018). De mediane overleving was gelijk in beide armen; HR 1,01; 95% CI: 0,70-1,45. De 3e RCT vergeleek gemcitabine + oxaliplatin met observatie in 196 patiënten met galweg- of galblaascarcinoom (Edeline, 2019). De mediane overleving was gelijk in beide armen; HR 1,08; 95% CI: 0,70-1,66. De 4e RCT vergeleek capecitabine met observatie in 447 patiënten met galweg- of galblaascarcinoom (Bridgewater, 2022). De mediane overleving was vergelijkbaar in beide armen in de lange termijn resultaten; HR 0,85; 95% CI: 0,67-1,06). In een per-protocol analyse met correctie voor lymfklier status, tumor graad en geslacht was de HR voor OS 0,74 met 95% CI 0,59-0,94. Zelfs in deze per-protocol analyse is de HR > 0,70.

Kwaliteit van leven werd in twee studies gerapporteerd, in één studie konden de resultaten langs de lat van klinische relevantie worden gelegd; geen van de subschalen op de EORTC QLQ-C30 liet een klinisch relevant verschil tussen de groepen zien. De bewijskracht was laag.

Daarnaast werden er ook resultaten gerapporteerd voor ziektevrije overleving en toxiciteit. Ziektevrije overleving werd gerapporteerd in alle vier de RCT’s en de lange-termijn follow-up publicatie van de BILCAP-studie (Bridgewater, 2021). In geen van deze studies werd een klinisch relevant verschil in ziektevrije overleving gerapporteerd. De bewijskracht was redelijk.

Toxiciteit (graad 3-4) werd in twee RCT’s gerapporteerd. In de ene studie (Ebata, 2018) kwamen vier hematologische ernstige bijwerkingen statistisch significant vaker voor in de groep die adjuvante chemotherapie kreeg (leukopenie, neutropenie, anemie, en trombocytopenie). Voor leukopenie en neutropenie was dit verschil tussen de groepen groter dan 25% (29,2% versus 1,9% en 58,4% versus 3,8%). In de andere studie (Edeline, 2019) waren er op basis van laboratoriumbepalingen vier ernstige bijwerkingen die statistisch significant vaker voorkwamen in de groep die adjuvante chemotherapie kreeg (neutropenie, trombocytopenie, stijging van alkaline fosfatase, stijging van GGT). Daarnaast kwamen perifere sensorische neuropathie en asthenie statistisch significant vaker voor in de groep die adjuvante chemotherapie kreeg. De bewijskracht was redelijk.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Gezien het hoge risico op een recidief is er wel een duidelijk wens naar adjuvante behandeling, zowel bij de artsen als ook bij patiënten. Dat er weinig bewijs is voor adjuvante behandeling, levert soms dilemma’s op bij patiënten met een hoog risico op recidief en bij jonge patiënten. Het is belangrijk om de gevolgen van systemische therapie te bespreken met de patiënt, denk hierbij bijvoorbeeld aan (ernstige) hand-voet syndroom, vermoeidheid, diarree, buikpijn en/ of misselijkheid bij capecitabine (Primrose, 2019).

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

In Nederland worden geen adjuvante behandelingen gegeven voor galwegcarcinoom na resectie. Hierbij is geen kostenafweging gemaakt, maar alleen een inhoudelijke keuze gemaakt op basis van onvoldoende effectiviteit. De kosten van bij voorbeeld capecitabine zelf zijn niet hoog, daarbij komen echter nog de kosten van begeleiding op de polikliniek door een medisch oncoloog.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De beperkte en onzekere overlevingswinst voor adjuvante behandeling rechtvaardigt het standaard gebruik van adjuvante behandeling niet. Dit is in overeenstemming met de huidige zorg.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De beperkte winst van adjuvante behandeling zoals gevonden in de reeds verrichte studies is de hoofdreden om geen adjuvante behandeling te adviseren.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

De meerderheid van de patiënten die een curatieve resectie heeft ondergaan voor een cholangiocarcinoom of een galblaascarcinoom, ontwikkelt binnen twee jaar na de operatie een lokaal recidief of metastasen op afstand (Belkouz, 2019). Er zijn individuele inschattingen mogelijk voor de overleving na resectie door middel van een nomogram of predictiemodel voor patiënten met een perihilair cholangiocarcinoom, distaal cholangiocarcinoom, intrahepatisch cholangiocarcinoom of galblaascarcinoom.

Gezien de hoge kans op een recidief is er behoefte aan een aanvullende behandeling om de kans op een recidief te verkleinen of het optreden van het recidief uit te stellen. Hiervoor zijn verschillende gerandomiseerde studies verricht. De vraag van dit hoofdstuk van de richtlijn is om deze studies te onderzoeken op effectiviteit en toepasbaarheid op de Nederlands situatie.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

LOW GRADE |

Adjuvant systemic chemotherapy may increase overall survival when compared with no adjuvant systemic chemotherapy in patients who underwent resection for cholangiocarcinoma or gallbladder carcinoma with curative intent.

Source: Takada, 2002; Ebata, 2018; Edeline, 2019; Primrose, 2019; Bridgewater, 2021; Luvira, 2021; |

Adjuvant systemic chemotherapy involved mitomycin C and 5-fluorouracil, gemcitabine, gemcitabine and oxaliplatin, and capecitabine.

|

Low GRADE |

Adjuvant systemic chemotherapy may not reduce or increase quality of life when compared with no adjuvant systemic chemotherapy in patients who underwent resection for cholangiocarcinoma or gallbladder carcinoma with curative intent.

Source: Primrose, 2019; Luvira, 2021; |

Adjuvant systemic chemotherapy involved capecitabine.

|

Moderate GRADE |

Adjuvant systemic chemotherapy may not reduce or increase disease-free survival when compared with no adjuvant systemic chemotherapy in patients who underwent resection for cholangiocarcinoma or gallbladder carcinoma with curative intent.

Source: Takada, 2002; Ebata, 2018; Edeline, 2019; Bridgewater, 2021; |

Adjuvant systemic chemotherapy involved mitomycin C and 5-fluorouracil, gemcitabine, gemcitabine and oxaliplatin, and capecitabine.

|

Moderate GRADE |

Adjuvant systemic chemotherapy likely increases (haematological) toxicity, when compared with no adjuvant systemic chemotherapy in patients who underwent resection for cholangiocarcinoma or gallbladder carcinoma with curative intent.

Source: Ebata, 2018; Edeline, 2019; |

Adjuvant systemic chemotherapy involved gemcitabine, and gemcitabine and oxaliplatin.

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Luvira (2021) published a Cochrane review providing an overview on the benefits and harms of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy for resectable cholangiocarcinoma. Electronic searches were performed in the Cochrane Hepato-Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, Embase, LILACS, Science Citation Index Expanded, and Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science for trials to identify relevant studies up to 28 April 2021. Eligible trials included adults who underwent curative-intent resection of cholangiocarcinoma. The diagnosis had to be confirmed by pathological examination of surgical specimens. All regimens of adjuvant chemotherapy were eligible and could be compared against no adjuvant treatment (surgery alone), placebo, or a different regimen or form of chemotherapy. For the current clinical question, only the comparison between adjuvant chemotherapy versus no adjuvant chemotherapy is relevant.

Relevant outcomes reported in the review by Luvira (2021) were “all-cause mortality”, defined as the number of people who died at five years, “cancer-related mortality”, “serious adverse events”, as defined by the ICH guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, “health-related quality of life”, as reported by the participants and as assessed by standard grading systems measured on a valid scale, and “time to recurrence of the tumor”. Where available, we extracted additional data on overall survival, quality of life, disease-free survival or toxicity from the original studies.

Four of the RCTs included in the review by Luvira (2021) provided a comparison between adjuvant chemotherapy versus no adjuvant chemotherapy (Takada, 2002; Ebata, 2018; Edeline, 2019; Primrose, 2019). Chemotherapy regimens used included mitomycin-C and 5-FU (Takada, 2002), gemcitabine (Ebata, 2018), gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin (Edeline, 2019), and capecitabine (Primrose, 2019). None of the interventions involved concurrent radiotherapy.

These studies were performed in Japan (n=2), France (n=1), and the United Kingdom (n=1). Patients in the study by Takada (2002) were included between 1986-1992, the other studies included patients more recently, between 2006 and 2014. The review by Luvira (2021) only extracted data for patients with cholangiocarcinoma, 867 in total. The trials by Takada (2002), Edeline (2019) and Primrose (2019) also included patients with gallbladder carcinoma. We extracted these data from the original studies and added the data to this literature summary. Takada (2002) included 436 patients with pancreatobiliary carcinoma, 118 of these patients had bile duct carcinoma and were included in the analysis by Luvira (2021), while 112 patients had gallbladder carcinoma. Ebata (2018) included 225 patients with extrahepatic bile duct cancer (45% perihilar, 55% distal). Edeline (2019) included 194 patients with biliary tract cancer (intrahepatic 44%, perihilar 8%, distal 28%, gallbladder 20%). Primrose (2019) included 447 patients with biliary tract cancer (intrahepatic 19%, hilar 29%, muscle-invasive gallbladder 18%, lower common bile duct cholangiocarcinoma 35%).

The authors of the review (Luvira, 2021) judged all four trials to be at overall high risk of bias, using a tool with three answer categories: ‘low risk of bias’, ‘unclear risk of bias’ and ‘high risk of bias’. Risk of bias was related to incomplete information about allocation sequence generation and concealment (Edeline, 2019; Takada, 2002), lack of blinding in all four trials, and reporting bias could not be assessed for the study of Takada (2002) because no protocol was available.

We performed our own risk of bias assessment using a tool with four answer categories (‘Definitely yes’, ‘Probably yes’, ‘Probably no’, and ‘Definitely no’). We had some concerns about the studies of Takada (2002) and Primrose (2019), while the risk of bias in the studies by Ebata (2018) and Edeline (2019) was judged to be low.

The discrepancy between the two assessments was related to the use of different answer categories. For the items about random sequence generation and allocation concealment, Luvira (2021) selected ‘unclear risk of bias’ for two studies where we selected ‘probably yes’.

For one of the RCTs included in the review by Luvira (2021), the BILCAP study (Primrose, 2019), long term results on overall survival and disease-free survival were published (Bridgewater, 2021).

Results

Overall survival

The review by Luvira (2021) presented a meta-analysis for patients with cholangiocarcinoma. Data from this meta-analysis are presented below under the heading ‘Cholangiocarcinoma’ Where available, data regarding patients with gallbladder carcinoma (Takada, 2002) or a mixed population of patients with cholangiocarcinoma or gallbladder carcinoma (Edeline, 2019; Primrose, 2019; Bridgewater, 20221) were extracted from the original trials and are presented under the headings ‘Gallbladder carcinoma’ and ‘Cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder carcinoma’.

Cholangiocarcinoma

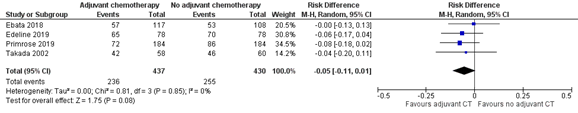

All four trials reported five-year survival of patients with cholangiocarcinoma, median follow-up time was more than three years. The review by Luvira (2021) converted these data to all-cause mortality at five years. In the group receiving adjuvant chemotherapy, 236 out of 437 patients had died after five years (54.0%). In the group receiving no adjuvant chemotherapy, 255 out of 430 patients had died after five years (59.3%). The risk difference was -0.05 [95%CI -0.11 to 0.01]. This difference fulfills the minimal clinically (patient) relevant difference of >5% difference between the groups.

Figure 1: Forest plot of all-cause mortality at five years

Gallbladder carcinoma

The study by Takada (2002) also reported five-year survival for gallbladder carcinoma. In the group receiving adjuvant mitomycin C and 5-fluorouracil, the five-year survival rate was 26.0%. In the group receiving no adjuvant chemotherapy, the five-year survival rate was 14.4% (p=0.04). This difference fulfills the minimal clinically (patient) relevant difference of > 5% difference between the groups.

Cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder carcinoma

The study by Edeline (2019) included both patients with cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder carcinoma. Data were reported only for all patients together. Overall survival rates at 48 months were 51% in the group that received adjuvant gemcitabine and oxaliplatin versus 52% in the group that did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy. The hazard ratio for all patients was 1.08 (95%CI 0.70 to 1.66). This HR did not fulfill the minimal clinically relevant difference of a HR < 0.7 between the groups.

The study by Primrose (2019) also included patients with gallbladder carcinoma. Data were reported for all patients (cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder carcinoma), not separately for gallbladder carcinoma. The hazard ratio for all patients (cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder carcinoma) was 0.81 (95%CI 0.63 to 1.04; p=0.097). No absolute difference between the groups was reported, the hazard ratio did not fulfill the minimal clinically (patient) relevant difference of a HR < 0.7 between the groups.

The publication by Bridgewater (2021) reported all-cause mortality in the BILCAP study after a median follow-up of 106 months (95%CI 98 to 108 months). These data involve patients with cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder carcinoma. The hazard ratio (adjusted for the stratification factors resection status, performance status and site of disease) was 0.84 (95%CI 0.67 to 1.06). This difference does not fulfill the minimal clinically (patient) relevant difference of a HR < 0.7 between the groups.

Quality of life

Two RCTs reported on health-related quality of life (Edeline, 2019; Primrose, 2019), both used the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaires. Edeline (2019) reported the time to definitive deterioration and found no statistically significant differences between the groups. Reported data did not include a comparison of scores in both groups and therefore no judgement of the clinical relevance of any differences (>10 points) could be made. Primrose (2019) reported median (IQR) standardised area under the curve, interpreted as the average monthly quality of life. No differences >10 points were reported for any of the functional or symptoms scales.

Disease-free survival

The original studies included in the review by Luvira (2021) reported data on disease-free survival (Takada, 2002), relapse-free survival (Ebata, 2018; Edeline, 2019), and recurrence-free survival (Primrose, 2019; Bridgewater, 2021).

Takada (2002) reported that for patients with cholangiocarcinoma, five-year disease-free survival rate was 20.7% in the group that received adjuvant mitomycin C and 5-fluorouracil and 15.0% in the group that did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy. For patients with gallbladder carcinoma, five-year disease-free survival rate was 20.3% in the group that received adjuvant mitomycin C and 5-fluorouracil and 11.6% in the group that did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy. No hazard ratio was reported, so it was not possible to assess whether these differences fulfilled the minimal clinically (patient) relevant difference of HR < 0.6.

In the study by Ebata (2018), five-year relapse-free survival rates were 45.7% in the group that received adjuvant gemcitabine and 44.0% in the group that did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy. The HR for relapse in patients receiving adjuvant gemcitabine, compared with no adjuvant chemotherapy, was 0.93 (95%CI 0.66 to 1.32; p=0.693). This difference does not fulfill the minimal clinically (patient) relevant difference of HR < 0.6.

In the study by Edeline (2019), relapse-free survival rates were 66% versus 64% at 12 months, 53% versus 46% at 24 months, 47% versus 43% at 36 months, and 36% versus 33% at 48 months in the groups that received gemcitabine and oxaliplatin versus no adjuvant chemotherapy. The hazard ratio for relapse-free survival was 0.88 (95%CI 0.62 to 1.25).

This difference does not fulfill the minimal clinically (patient) relevant difference of HR < 0.6.

The long-term results of the BILCAP study (Bridgewater, 2021) showed a median recurrence-free survival of 24.3 months (95%CI 18.6 to 34.6 months) in the group that received adjuvant capecitabine and 17.4 months (95%CI 11.8 to 23.0 months) in the group that did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy. The hazard ratio (adjusted for the minimization factors resection status, performance status and site of disease) was 0.81 (95%CI 0.65 to 1.01). This difference does not fulfill the minimal clinically (patient) relevant difference of HR < 0.6.

Toxicity

Ebata (2018) assessed serious adverse events according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0. For four categories of grade 3 or 4 serious events, all haematological events, a statistically significant difference was found between the groups (leucocytes 29.2% vs 1.9%; p<0.001, neutrophils 58.4% vs. 3.8%; p<0.001, haemoglobin 7.1% vs 0.9%; p=0.036 and platelets 7.1% vs 0%, p=0.007). The differences for leucocytes and neutrophils fulfill the minimal clinically (patient) relevant difference of 25%.

Edeline (2019) also assessed serious adverse events according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 3.0), except for neurotoxicity, which was assessed using Levi’s scale. For four grade 3 or 4 laboratory serious adverse events, statistically significant differences were found between the groups: neutrophil decrease 17% vs 0%; p<0.001, platelets decrease 7% vs 0%, p=0.01; alkaline phosphatase increase 9% vs 2%, p=0.05; and GGT increase 37% vs 14%; p<0.001. For two grade 3 or 4 clinical serious adverse events, statistically significant differences were found between the groups: peripheral sensory neuropathy (18% vs 0%, p<0.001), and asthenia (8% vs 0%, p=0.01). None of these differences fulfilled the minimal clinically (patient) relevant diference of 25%.

Level of evidence of the literature

The evidence was derived from (a systematic review of) RCTs, therefore the level of evidence for all outcomes started at ‘high’. The authors of the Cochrane review performed a GRADE assessment and downgraded three levels to ‘very low’ for both overall survival and toxicity. However, this risk of bias was mainly caused by ‘performance and detection bias’ because these trials did not use placebo in the arm that did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy. For an objective outcome as overall survival, this assessment was deemed to be too strict and a new GRADE assessment was performed.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure overall survival was downgraded by two levels because of conflicting results (-1 inconsistency, unexplained heterogeneity) and the number of included patients (-1 imprecision, because the pooled confidence interval includes the possibility of no difference).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (-1 risk of bias, because of lack of blinding); number of included patients (-1 imprecision, because this was a single trial including a total of 447 patients).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure disease-free survival was downgraded by one level because of number of included patients (-1 imprecision, because the confidence interval included the possibility of a clinically relevant difference).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure toxicity was downgraded by one level because of the number of included patients (-1 imprecision, because there were two trials including a total of 415 patients).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the benefits and risks of adjuvant systemic treatment compared with no adjuvant systemic treatment for patients who underwent resection for cholangiocarcinoma or gallbladder cancer with curative intent?

| P: | patients who underwent resection for cholangiocarcinoma or gallbladder cancer with curative intent |

| I: | adjuvant systemic treatment, with or without concurrent radiotherapy |

| C: | no systemic treatment |

| O: |

critical: overall survival, quality of life important: disease-free survival, toxicity |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered overall survival and quality of life as critical outcome measures for decision making; and disease-free survival and toxicity as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined the following minimal clinically (patient) relevant differences (using the PASKWIL criteria for adjuvant treatment where possible):

- Overall survival: > 5% difference between the groups or > 3% difference and HR < 0.7, at least three years of median follow-up time

- Quality of life: A minimal clinically important difference of 10 points on the quality-of-life instrument EORTC QLQ-C30 or a difference of a similar magnitude on other quality of life instruments.

- Disease-free survival: HR < 0.6

- Toxicity: ≥ 5% difference in lethal adverse events and ≥ 25% difference in serious (grade ≥3) adverse events

Search and select (Methods)

For the update of this guideline, two broad systematic literature searches were performed to identify relevant publications involving patients with biliary tract cancer. First, the databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched using relevant search terms for systematic reviews published between January 1st 2012 and December 31st 2019 for Medline, and between January 1st 2012 and August 31rd 2020 for Embase. Second, the databases Medline (via OVID), Embase (via Embase.com) and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (via Wiley) were searched for RCTs published between January 1st 2015 and October 12th 2020. The detailed search strategies are depicted under the tab Methods.

The systematic literature searches resulted in 547 unique hits for systematic reviews and 1304 unique hits for RCTs. A preselection of systematic reviews and RCTs based on study population and study design was made. In case of doubt about the eligibility of a particular publication, this publication was included in the preselection. Potentially relevant studies were divided into four categories: diagnosis, surgery, systemic treatment, and other treatment options. The preselection in the category ‘systemic treatment’ included 773 hits.

Subsequently, publications were screened based on title and abstract using the following selection criteria: (a) full-text publication in English or Dutch; (b) systematic review or RCT; (c) involving patients who underwent resection for cholangiocarcinoma or gallbladder carcinoma with curative intent; and (d) comparing at least one of the aforementioned outcome measures between patients who received adjuvant systemic therapy and patients who received no adjuvant systemic therapy. This resulted in 20 systematic reviews and 8 RCTs. After reading the full text, one systematic review was included in the analysis of the literature. A table with reasons for exclusion is presented under the tab Methods.

Results

One systematic review was included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence table. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias table.

Referenties

- Belkouz, A, Wilmink JW, Haj Mohammad N, Hagendoorn J, de Vos-Geelen J, de Jong CHC, Homs MYV, Groot Koerkamp B, van Gulik TM, Punt CJA, Klümpen HJ. Nieuwe ontwikkelingen in de adjuvante behandeling van het cholangiocarcinoom en galblaascarcinoom. [New developments in the adjuvant treatment of cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder carcinoma]. Ned Tijdschr Oncol. 2019;16:24-31.

- Bridgewater J, Fletcher P, Palmer DH, Malik HZ, Prasad R, Mirza D, Anthony A, Corrie P, Falk S, Finch-Jones M, Wasan H, Ross P, Wall L, Wadsley J, Evans TR, Stocken D, Stubbs C, Praseedom R, Ma YT, Davidson B, Neoptolemos J, Iveson T, Cunningham D, Garden OJ, Valle JW, Primrose J; BILCAP study group. Long-Term Outcomes and Exploratory Analyses of the Randomized Phase III BILCAP Study. J Clin Oncol. 2022 Jun 20;40(18):2048-2057. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02568. Epub 2022 Mar 22. PMID: 35316080.

- Ebata T, Hirano S, Konishi M, Uesaka K, Tsuchiya Y, Ohtsuka M, Kaneoka Y, Yamamoto M, Ambo Y, Shimizu Y, Ozawa F, Fukutomi A, Ando M, Nimura Y, Nagino M; Bile Duct Cancer Adjuvant Trial (BCAT) Study Group. Randomized clinical trial of adjuvant gemcitabine chemotherapy versus observation in resected bile duct cancer. Br J Surg. 2018 Feb;105(3):192-202. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10776. PMID: 29405274.

- Edeline J, Benabdelghani M, Bertaut A, Watelet J, Hammel P, Joly JP, Boudjema K, Fartoux L, Bouhier-Leporrier K, Jouve JL, Faroux R, Guerin-Meyer V, Kurtz JE, Assénat E, Seitz JF, Baumgaertner I, Tougeron D, de la Fouchardière C, Lombard-Bohas C, Boucher E, Stanbury T, Louvet C, Malka D, Phelip JM. Gemcitabine and Oxaliplatin Chemotherapy or Surveillance in Resected Biliary Tract Cancer (PRODIGE 12-ACCORD 18-UNICANCER GI): A Randomized Phase III Study. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Mar 10;37(8):658-667. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00050. Epub 2019 Feb 1. PMID: 30707660.

- Luvira V, Satitkarnmanee E, Pugkhem A, Kietpeerakool C, Lumbiganon P, Pattanittum P. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy for resectable cholangiocarcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Sep 13;9(9):CD012814. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012814.pub2. PMID: 34515993; PMCID: PMC8437098.

- Primrose JN, Fox RP, Palmer DH, Malik HZ, Prasad R, Mirza D, Anthony A, Corrie P, Falk S, Finch-Jones M, Wasan H, Ross P, Wall L, Wadsley J, Evans JTR, Stocken D, Praseedom R, Ma YT, Davidson B, Neoptolemos JP, Iveson T, Raftery J, Zhu S, Cunningham D, Garden OJ, Stubbs C, Valle JW, Bridgewater J; BILCAP study group. Capecitabine compared with observation in resected biliary tract cancer (BILCAP): a randomised, controlled, multicentre, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2019 May;20(5):663-673. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30915-X. Epub 2019 Mar 25. Erratum in: Lancet Oncol. 2019 Apr 2;: PMID: 30922733.

- Takada T, Amano H, Yasuda H, Nimura Y, Matsushiro T, Kato H, Nagakawa T, Nakayama T; Study Group of Surgical Adjuvant Therapy for Carcinomas of the Pancreas and Biliary Tract. Is postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy useful for gallbladder carcinoma? A phase III multicenter prospective randomized controlled trial in patients with resected pancreaticobiliary carcinoma. Cancer. 2002 Oct 15;95(8):1685-95. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10831. PMID: 12365016.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

Luvira, 2021

[individual study characteristics deduced from Luvira, 2021 unless otherwise indicated]

|

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to 28 April 2021

A: Takada, 2002 B: Ebata, 2018 C: Edeline, 2019 D: Primrose, 2019 (with additional information available in E: Bridgewater, 2021)

Parallel-group design

Setting and country: A: 31 centres, Japan B: 48 hospitals, Japan C: 33 centres, France D: 44 specialist hepato-pancreato-biliary centres, United Kingdom

Source of fundinga: A: Not stated B: Nagoya Surgery Support Organization and Eli Lilly Japan K.K. C: Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique (PHRC 2009) and Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer D: Cancer Research UK and Roche (advisory role in study design)

Conflicts of interestsa: A: not stated B: none reported C: several conflicts of interest reported D: several conflicts of interest reported |

Inclusion criteria: - RCTs - adults (aged 18 years or older) of any sex who underwent curative intent resection for cholangiocarcinoma and received any type of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy compared with people with the same condition, but receiving placebo, no postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy, or other adjuvant chemotherapies - diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma was established by pathological examination of surgical specimens

5 studies included, four of which provided a comparison between adjuvant systemic chemotherapy versus no adjuvant systemic chemotherapy

N A: 508, 139 of which had bile duct carcinoma B: 225 C: 196 D: 447

Tumour locationa, n (%) A: bile duct carcinoma 118 (100%) B: perihilar 102 (45%), distal 123 (55%) C: intrahepatic 86 (44%), perihilar 15 (8%), distal 55 (28%), gallbladder 38 (20%) D: intrahepatic 84 (19%), hilar 128 (29%), muscle-invasive gallbladder 79 (18%), lower common bile duct cholangiocarcinoma 156 (35%)

|

Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy

A: mitomycin-C 6 mg/m2 on day of surgery, 5-FU 310 mg/m2 2 courses for 5 consecutive days (during postoperative weeks 1 and 3), 5-FU (orally) daily B: gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 over 30 minutes on day 1, 8 and 15 followed by a rest period of 1 week C: gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 over 100 minutes on day 1, oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2 over 2 hours on day 2 every 2 weeks for 12 cycles D: capecitabine 1250 mg/m2 twice a day on days 1 to 14 of a 3-weekly cycle for 24 weeks

|

No postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy

|

End-point of follow-up: A: 5 years B: median of 79.4 months C: median of 46.5 months D: median of 60 months

For how many patients were no complete outcome data available: A: none B: two C: none D: none

|

All-cause mortality: Number of people who died at five years

Cholangiocarcinoma

A: I: 42/58 (72%) / C: 46/60 (77%); RD -0.04 [95%CI -0.20 to 0.11] B: I: 57/117 (49%) / C: 53/108 (49%); RD 0.00 [95%CI -0.13 to 0.13] C: I: 65/78 (83%) / C: 70/78 (90%); RD -0.06 [95%CI -0.17 to 0.04] D: 72/184 (39%) / C: 86/184 (47%); RD -0.08 [95%CI 0.18 to 0.02]

Pooled effect (random effects model): RD -0.05 [95% CI -0.11 to 0.01] favoring adjuvant systemic chemotherapy Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Five-year survival ratesa

Gallbladder carcinoma

A: I: 26.0% / C: 14.4%

Five-year mortality and hazard ratioa

Cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder carcinoma

C: I: 43% / C: 41%; HR 1.078 (95% CI 0.699 to 1.663) D: I: 51% / C: 58% HR 0.81 (95% CI 0.63 to 1.04; p=0.097) E: I: 65% / C: 71%

Quality of lifea

D:

QLQ-C30 functioning scales, median (IQR) standardised area under the curve

Physical I: 82.5 (64.0 to 92.7) / C: 85.0 (70.0 to 93.3); p=0.16 Role I: 72.9 (50.5 to 91.7) / C: 81.3 (52.8 to 91.7); p=0.18 Emotional 79.9 (58.9 to 92.2) / C: 83.3 (64.8 to 93.2); p=0.36 Cognitive I: 87.5 (66.1 to 96.4) / C: 87.5 (76.0 to 100); p=0.1 Social I: 76.2 (56.9 to 91.7) / C: 83.3 (64.6 to 95.8); p=0.0060 Global health status or quality of life I: 67.9 (52.1 to 80.6) / C: 70.8 (56.3 to 83.3); p=0.18

QLQ-C30 symptoms scales

Fatigue I: 27.8 (15.0-43.3) / C: 27.1 (11.1 to 38.9); p=0.27 Nausea and vomiting I: 2.8 (0.0 to 11.3) / C: 1.4 (0.0 to 8.3); p=0.27 Pain I: 17.7 (5.2 to 38.2) / C: 16.7 (6.3 to 33.3); p=0.8 Dyspnoea I: 6.3 (0.0 to 25.0) / C: 8.3 (0.0-25.0); p=0.43 Insomnia I: 21.9 (4.9 to 44.1) / C: 20.8 (5.6 to 41.7); p=0.8 Appetite loss I: 6.3 (0.0 to 18.8) / C: 8.3 (0.0 to 20.8); p=0.88 Constipation I: 4.2 (0.0 to 22.9) / C: 2.1 (0.0 to 16.7); p=0.62 Diarrhoea I: 8.3 (0.0 to 16.7) / C: 4.2 (0.0 to 16.7); p=0.36 Financial difficulties I: 2.1 (0.0 to 22.2) / C: 0.0 (0.0 to 18.8); p=0.35

Disease-free survivalab

A: five-year disease-free survival rate cholangiocarcinoma I: 20.7% / C: 15.0% five-year disease-free survival rate gallbladder carcinoma I: 20.3% / C: 11.6% B: five-year relapse-free survival rate cholangiocarcinoma I: 45.7% / C: 44.0% HR 0.93 (95%CI 0.66 to 1.32; p=0.693) C: relapse-free survival rate 12 months I: 66% / C: 64% 24 months I: 53% / C: 46% 36 months I: 47% / C: 43% 48 months I: 36% / C: 33% HR 0.880 (95%CI 0.620 to 1.249) D: disease recurrence rate I: 60% / C: 65% 0-24 months HR 0.75 (95%CI 0.58 to 0.98; p=0.033) 24-60 months HR 1.48 (95%CI 0.80 to 2.77; p=0.21) E: HR 0.81 (95%CI 0.65 to 1.01), adjusted for resection status, performance status and site of disease

Toxicity (serious adverse events) a: Number of people experiencing serious adverse events

B: Haematological toxicity grade 3 or 4a , n (%)

Leucocytes I: 33 (29.2%) / C: 2 (1.9%); p<0.001 Neutrophils I: 66 (58.4%) / C: 4 (3.8%); p<0.001 Haemoglobin I: 8 (7.1%) / C: 1 (0.9%); p=0.036 Platelets I: 8 (7.1%) / C: 0; p=0.007 AST I: 2 (1.8%) / C: 2 (1.9%); p=1.000 ALT I: 1 (0.9%) / C: 1 (0.9%); p=1.000 Bilirubin I: 0 / C: 4 (3.8%); p=0.053 Creatinine I: 0 / C: 0; p=1.000

Non-haematological toxicity grade 3 or 4a, n (%)

Fatigue I: 6 (5.3%) / C: 1 (0.9%); p=0.120 Anorexia I: 6 (5.3%) / C: 2 (1.9%); p=0.282 Nausea I: 1 (0.9%) / C: 0; p=1.000 Vomiting I: 1 (0.9%) / C: 1 (0.9%); p=1.000 Diarrhoea I: 0 / C: 0; p=1.000 Fever I: 4 (3.5%) / C: 0; p=0.122 Febrile neutropenia I: 0 / C: 0; p=1.000 |

Review authors’ conclusion: Based on the very low-certainty evidence found in four trials in people with curative-intent resection for cholangiocarcinoma, we are very uncertain of the effects of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy (mitomycin-C and 5-FU; gemcitabine; gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin; or capecitabine) versus no postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy on mortality. The effects of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy compared with no postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy on serious adverse events are also very uncertain, but the result of the single trial showed 20% higher occurrences of haematologic adverse events. We assessed the certainty of the evidence as very low due to overall high risk of bias, and imprecision.

There is a need for further randomised clinical trials designed to be at low risk of bias and with adequate sample size exploring the best adjuvant chemotherapy treatment after surgery in people with cholangiocarcinoma.

|

a Data extracted from the original study

b Data extracted from the additional publication on the BILCAP trial by Bridgewater (2021)

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Luvira, 2021 |

Yes |

Yes

Search period and strategy are described and multiple databases were searched |

Yes |

Yes

Characteristics relevant to the PICO were reported |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes

Conflicts of interest were reported for the review

No

Source of funding and conflicts of interest were not reported for the studies included in the review

|

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs)

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table etc.)

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (e.g. Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (e.g., funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (e.g., Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

Research question: What are the benefits and risks of adjuvant systemic treatment compared with no adjuvant systemic treatment for patients who underwent resection for cholangiocarcinoma with curative intent?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Takada, 2002 |

Probably yes;

Reason: A randomized design, stratified according to institution and disease, was used |

No information;

|

Definitely no;

Reason: The control group was not treated with any drugs including placebo |

Probably yes;

Reason: An intention to treat analysis was performed, 98% of eligible patients were included in the analysis |

Probably yes;

Reason: All outcomes described in the Methods section are reported in the Results section |

Probably no;

Reason: The sample size calculation was based on an assumed difference of 20% in 5-year survival rate between the groups (15% in the control group). The number of eligible patients was unbalanced between the treatment arms for gallbladder carcinoma (I:69/C:43)

|

Some concerns

(overall survival, disease-free survival) |

|

Ebata, 2018 |

Probably yes;

Reason: Patients were assigned randomly by a modified minimization method

|

Definitely yes;

Reason: Treatment allocation was performed centrally through a web-based randomization system managed by the data centre

|

Definitely no;

Reason: open-label study |

Definitely yes;

Reason: An intention to treat analysis was performed, 225/226 patients were included in the analysis |

Probably yes;

Reason: All outcomes described in the Methods section are reported in the Results section |

Probably no;

Reason: the target sample size of 300 was not reached |

LOW

(overall survival, disease-free survival, toxicity |

|

Edeline, 2019 |

Probably yes;

Reason: Randomization with minimization was stratified by primary site |

Probably yes;

Reason: No explicit information, but a randomization procedure with minimization is performed at the time of allocation and therefore it will be difficult to impossible to predict which group the patient will be allocated to

|

Definitely no;

Reason: open-label study |

Definitely yes;

Reason: An intention to treat analysis was performed, 194/196 patients were included in the analysis |

Probably yes;

Reason: All outcomes described in the Methods section are reported in the Results section |

Probably yes;

Reason: no other issues noted |

LOW

(overall survival, disease-free survival, toxicity) |

|

Primrose, 2019 Bridgewater, 2021 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: A computerized algorithm was used |

Probably yes;

Reason: Allocation was centrally generated and broken by telephone. Although it was not reported who was aware of the allocation scheme generated from the computer, it seems unlikely that care providers can estimate the allocation through the system and cause selection bias |

Definitely no;

Reason: treatments were not blinded |

Probably no;

Reason: An intention to treat analysis was performed, all eligible patients were included in the analysis

|

Definitely yes;

Reason: All outcomes defined in the study protocol were reported in the manuscript |

No information;

Reason: intention-to-treat and per protocol analyses are reported, however these analyses provide too little descriptions for intercurrent events (and how these were handled) to assess if any other risk of bias was present

The funder of the study has an advisory role in study design but no role in the running of the study, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report

|

Some concerns

(overall survival, quality of life, disease-free survival) |

Randomization: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomization process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomization (performed at a site remote from trial location). Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomization procedures or open allocation schedules..

Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments, but this should not affect the risk of bias judgement. Blinding of those assessing and collecting outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignment influences the process of outcome assessment or data collection (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is usually not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary. Finally, data analysts should be blinded to patient assignment to prevents that knowledge of patient assignment influences data analysis.

Lost to follow-up: If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up or the percentage of missing outcome data is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up or missing outcome data differ between treatment groups, bias is likely unless the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk is not enough to have an important impact on the intervention effect estimate or appropriate imputation methods have been used.

Selective outcome reporting: Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available (in publication or trial registry), then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

Other biases: Problems may include: a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used (e.g. lead-time bias or survivor bias); trial stopped early due to some data-dependent process (including formal stopping rules); relevant baseline imbalance between intervention groups; claims of fraudulent behavior; deviations from intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis; (the role of the) funding body (see also downgrading due to industry funding https://kennisinstituut.viadesk.com/do/document?id=1607796-646f63756d656e74). Note: The principles of an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

Overall judgement of risk of bias per study and per outcome measure, including predicted direction of bias (e.g. favors experimental, or favors comparator). Note: the decision to downgrade the certainty of the evidence for a particular outcome measure is taken based on the body of evidence, i.e. considering potential bias and its impact on the certainty of the evidence in all included studies reporting on the outcome.

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Reviews |

|

|

Messina, 2019 |

Review including more RCTs available |

|

Kish, 2020 |

Review including more RCTs available |

|

Ke 2020 |

Review of retrospective studies |

|

Shroff, 2019 |

Wrong publication type: clinical guideline |

|

Manterola, 2019 |

Review of retrospective studies |

|

Suzuki, 2019 |

Narrative review |

|

Wang, 2019 |

Review of retrospective studies |

|

Ma, 2019 |

Review of retrospective studies |

|

Horgan, 2018 |

Narrative review |

|

Kim, 2018 |

Review of retrospective studies |

|

Acharya, 2017 |

Wrong population: periampullary adenocarcinoma |

|

Ghidini, 2017 |

Review including retrospective studies |

|

Doherty, 2016 |

Review of retrospective studies |

|

Kwon, 2015 |

Review of retrospective studies |

|

Ma, 2015 |

Review of retrospective studies |

|

Zhu, 2014 |

Wrong population: periampullary adenocarcinoma |

|

Williams, 2014 |

Narrative review |

|

Wei, 2013 |

Wrong comparison |

|

Horgan, 2012 |

Review including retrospective studies |

|

RCTs |

|

|

Ebata, 2018 |

Included in the review by Luvira (2021) |

|

Edeline, 2019 |

Included in the review by Luvira (2021) |

|

Kobayashi, 2019 |

Included in the review by Luvira (2021) |

|

Primrose, 2019 |

Included in the review by Luvira (2021) |

|

Seita, 2020 |

Wrong study design |

|

Sharma, 2019 |

Wrong comparison |

|

Siebenhüner, 2018 |

Wrong study design |

|

Terajima, 2018 |

Wrong publication type: abstract |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 25-06-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Overzicht modules

Tranche 1 (deze modules zijn in 2023 geautoriseerd)

|

Hoofdstuk |

Nr |

Moduletitel |

Vorm |

|

Diagnostiek |

1 |

Meerwaarde PET bij biliare tumoren |

Nieuw ontwikkeld |

|

Behandeling |

2 |

Preoperatieve galwegdrainage |

Nieuw ontwikkeld |

|

Pathologie |

3 |

Verslag en aanvraag pathologie |

Update van bestaande module |

|

Communicatie en besluitvorming |

4 |

Communicatie en besluitvorming |

Nieuw ontwikkeld |

|

Nazorg |

5 |

Nazorg en nacontrole |

Update van bestaande module |

Tranche 2 (huidige autorisatieronde)

|

Hoofdstuk |

|

Moduletitel |

Vorm |

|

Diagnostiek |

6 |

Cross-sectionele beeldvorming |

Update van bestaande module |

|

Behandeling |

7 |

Locoregionale behandeling met TACE of SIRT voor iCCA |

Nieuw ontwikkeld |

|

Behandeling |

8 |

Preoperatieve vena porta embolisatie |

Update van bestaande module |

|

Behandeling |

9 |

Indicatie resectie |

Update van bestaande module |

|

Behandeling |

10 |

Adjuvante systemische behandeling |

Update van bestaande module |

|

Behandeling |

11 |

Palliatieve systemische behandeling in de 1e lijn |

Update van bestaande module |

|

Behandeling |

12 |

Palliatieve systemische behandeling na de 1e lijn |

Update van bestaande module |

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2020 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met galweg- of galblaascarcinoom.

Werkgroep

- Dr. B. (Bas) Groot Koerkamp, Chirurg/ Epidemioloog, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, NVvH (voorzitter)

- Dr. J.I. (Joris) Erdmann, Chirurg, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, NVvH

- Dr. P.R. (Philip) de Reuver, Chirurg, Radboudumc, Nijmegen, NVvH

- Dr. M.T. (Marieke) de Boer, Chirurg, UMCG, Groningen, NVvH ((tot mei 2022)

- Dr. F.J.H. (Frederik) Hoogwater, Chirurg, UMCG, Groningen, NVvH (vanaf mei 2022)

- Dr. H.J. (Heinz-Josef) Klümpen, Internist-oncoloog, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, NIV

- Dr. N. (Nadia) Haj Mohammad, Internist-oncoloog, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, NIV

- Drs. F.E.J.A. (Franꞔois) Willemsen, Abdominaal radioloog, Erasmus MC, NVvR

- Prof. dr. O.M. (Otto) van Delden, interventieradioloog, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, NVvR

- Dr. L.M.J.W. van Driel, maag-darm-leverarts, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, NVMDL

- Prof. dr. J. (Joanne) Verheij, klinisch patholoog, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, NVVP

- Dr. R.S. (Chella) van der Post, patholoog, Radboudumc, Nijmegen, NVVP (vanaf februari 2022)

- C. (Chulja) Pek, Verpleegkundig specialist, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, V&VN

- Drs. M.A. (Marga) Schrieks, Projectleider Patiëntenplatform Zeldzame Kankers, NFK

- A. (Anke) Bode MSc, Patiëntvertegenwoordiger, NFK (tot april 2023)

- Drs. A.C. (Christine) Weenink, Patiëntvertegenwoordiger/huisarts, NFK (vanaf april 2023)

Met dank aan

- M. (Mike) van Dooren, arts-onderzoeker, Radboudumc, Nijmegen

-

Dr. S. (Stefan) Büttner, AIOS chirurgie, Erasmus MC

Met ondersteuning van

- Drs. M. Oerbekke, Adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. N. Elbert, Adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. L.J.M. Oostendorp, Senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Groot Koerkamp |

Chirurg en epidemioloog, Erasmus MC |

Onbetaald: * secretaris wetenschappelijke commisssie van de Ducth Pancreatic Cancer Group (DPCG) * bestuurslid van de Dutch Hepatocellular and Cholangiocarcinoma Group (DHCG) * Lid van de audit commissie van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunden (NVvH) * Voorzitter van de werkgroep cholangiocarcinoom van de DHCG * Lid van de wetenschappelijke commissie van de DHCG |

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Expertise op gebied van intra-arteriele chemotherapie. Ik ben PI vna een door KWF gefinancierde klinische studie van intra-arteriele chemotherapie voor niet-resectabel intrathepatisch cholangiocarcinoom |

Geen restricties (in deze herziening komt het onderwerp Hepatic Arterial Infusion niet aan de orde) |

|

Erdmann |

Chirurg, Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

De Reuver |

Chirurg gastro-enterologische chirurgie, Radboudumc, Nijmegen |

Geen |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek PI van onderzoek naar Galblaascarcinoom, in 2017 gefinancieerd door Stichting ADP. Stichting heeft geen belang in het advies of de richtlijn. |

Geen restricties |

|

De Boer |

Chirurg UMCG afdeling chirurgie, HPB chirurgie en levertransplantatie |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Hoogwater |

Chirurg, Hepato-Pancreato-Biliaire Chirurgie en Levertransplantatie, Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen |

* Bestuurslid - Dutch Hepatocellular & Cholangiocarcinoma Group (DHCG), onbetaald * Commissielid - Continue Professionele Educatie van de NVvH, onbetaald * Lid - Wetendchappelijke Commissie Dutch Hepato Biliary Audit (DHBA), vacatiegeld * Bestuurslid Nederlandse Vereniging Chirurgische Oncologie (NVCO), onbetaald

|

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Klümpen |

Internist-oncoloog in Amsterdam UMC |

* Subdomain leader for biliary tract cancer EURACAN (onbetaald) * Lid wetenschappelijke commissie van de DHCG (onbetaald) * Dutch representative for European Cooperation in Science and Technology COST (biliary tract cancer) grant by HORIZON 2020 (onbetaald, wel worden reizen vergoed die door COST georganiseerd worden) * Member of European Network for the Study of Cholangiocarcinoma ENSCCA (onbetaald) * Member international billary tract cancer consortium IBTCC (onbetaald) |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek KWF financieert de ACTICCA studie en PUMP 2 studie, deze studies zijn gesloten voor inclusie

Het Amsterdam UMC met mij als lokale PI doet mee en heeft meegedaan aan studies voor galweg en galblaascarcinoom: * TAS-120 studie van TAIHO (fase I/II) * SIRCCA studie van SIRTEX (fase III, is vroegtijdig gestopt) * KEYNOTE 966 studie van MSD (fase III studie)

|

Geen restricties tenzij een van de middelen uit het extern gefinancierd onderzoek toch aan de orde komt in deze herziening. In dat geval volgt uitsluiting van de formulering van de aanbevelingen over de middelen in de betreffende trials.

TAS-120: futibatinib (TAIHO)

SIRCCA: selective internal radiotherapy SIRT met 90-Y microspheres i.c.m. chemotherapie (SIRTEX)

KEYNOTE-966: pembrolizumab (MSD)

|

|

Haj Mohammad |

Internist-oncoloog, Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht |

* Penningmeester Dutch Upper GI Cancer (DUCG), onbetaald * Lid Wetenschappelijke raad DHCG, onbetaald * Member of European Network for the Study of Cholangiocarcinoma ENSCCA, onbetaald

Advisory boards: Astra Zenca, Servier, BMS, Merck, Lilly, betaald aan mijn afdeling

|

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek * Merck – MK 966 gemetastaseerd BTC fase 3, gem cis + placebo vs gem cis + pembrolizumab (lokale PI) * Incyte – FIGHT-302: FGFR fusie, fase 3 gerandomiseerd gem cis vs pemigatinib (lokale PI) * KWF - PUMP-2: irresectabel intrahepatisch cholangiocarcinoom, fase 2 haalbaarheid intrahepatische chemotherapie gecombineerd met systemische chemotherapie (lokale PI) * KWF - ACTICCA: adjuvant, fase 3 gerandomiseerd gem cis vs capecitabine (lokale PI)

|

Bij aanvang van het project waren geen restricties geformuleerd. Bij het herbevestigen van belangen werden een aantal nieuwe belangen gemeld. Om de onafhankelijkheid van de richtlijn te waarborgen zijn de betreffende modules meegelezen door twee onafhankelijke deskundigen vanuit de NIV. |

|

Willemsen |

Abdominaal radioloog Erasmus MC te Rotterdam |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Van Delden |

Interventieradioloog, Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Van Driel |

MDL-arts, staflid, Erasmus MC Rotterdam - fulltime aanstelling |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Verheij |

Klinisch patholoog (1 fte) met specialisme Hepato-pancreatobiliaire pathologie Amsterdam UMC |

* Lid medisch Advies Raad Nederlandse Leverpatiënten Vereniging (NLV) (onbetaald) * Voorziter sectie HPB, Expertise Groep Gastrointestinale Pathologie, NVVP (onbetaald)

|

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Van der Post |

Klinisch patholoog, Radboud Universitair medisch centrum |

* Commissie lid Wetenschap NVVP (onbetaald) * Programmacommissie lid Kwaliteitsprojecten SKMS (vacatiegelden) * Voorzitter expertisegroep gastrointestinale pathologen EGIP, onderdeel NVVP (onbetaald) |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek * Stichting ADP - From bench to bedside, the molecular characteristics of galbladder cancer - Projectleider * KWF kankerbestrijding - Dissecting the role of aberrant E-cadherin signaling in the initiation and progression of diffuse-type gastric cancer - Projectleider * Stichting Hanarth Fonds - Unmasking the invisible cancer: digital detection of diffuse-type gastric carcinomas - Projectleider |

Geen restricties |

|

Pek |

Verpleegkundig specialist Erasmus MC Rotterdam. Pancreas- en galwegchircurgie specialist obstructie icterus |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Schrieks |

Projectleider Patiëntenplatform Zeldzame Kanker |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Bode |

* Patiënt vertegenwoordiger * Kinderfysiotherapeut MSc in ruste Zorggroep Almere (niet meer werkzaam) * Vrijwilliger bij patiëntenplatform Zeldzame kankers |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Weenink |

Patiënt vertegenwoordiger Huisarts bij HAP Binnenstad Utrecht |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van het Patiëntenplatform Zeldzame Kankers om deel te nemen in de werkgroep en aan de schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn zal tevens voor commentaar worden voorgelegd aan Patiëntenplatform Zeldzame Kankers.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module ‘Adjuvante systemische behandeling’ |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbevelingen niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5.000 patiënten) en daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zullen hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven. |

Implementatie

Inleiding

Dit plan is opgesteld ter bevordering van de implementatie van de richtlijn Galweg- en galblaascarcinoom. Voor het opstellen van dit plan is een inventarisatie gedaan van de mogelijk bevorderende en belemmerende factoren voor het toepassen en naleven van de aanbevelingen. Daarbij heeft de richtlijnwerkgroep een advies uitgebracht over het tijdspad voor implementatie, de daarvoor benodigde randvoorwaarden en de acties die voor verschillende partijen ondernomen dienen te worden.

Werkwijze

De werkgroep heeft per aanbeveling geïnventariseerd:

• per wanneer de aanbeveling overal geïmplementeerd moet kunnen zijn;

• de verwachtte impact van implementatie van de aanbeveling op de zorgkosten;

• randvoorwaarden om de aanbeveling te kunnen implementeren;

• mogelijk barrières om de aanbeveling te kunnen implementeren;

• mogelijke acties om de implementatie van de aanbeveling te bevorderen;

• verantwoordelijke partij voor de te ondernemen acties.

Voor iedere aanbevelingen is nagedacht over de hierboven genoemde punten. Echter niet voor iedere aanbeveling kon ieder punt worden beantwoord. Er kan een onderscheid worden gemaakt tussen “sterk geformuleerde aanbevelingen” en “zwak geformuleerde aanbevelingen”. In het eerste geval doet de richtlijncommissie een duidelijke uitspraak over iets dat zeker wel of zeker niet gedaan moet worden. In het tweede geval wordt de aanbeveling minder zeker gesteld (bijvoorbeeld “Overweeg om …”) en wordt dus meer ruimte gelaten voor alternatieve opties. Voor “sterk geformuleerde aanbevelingen” zijn bovengenoemde punten in principe meer uitgewerkt dan voor de “zwak geformuleerde aanbevelingen”. Bij elke module is onderstaande tabel opgenomen.

|

Aanbeveling |

Tijdspad voor implementatie: 1 tot 3 jaar of > 3 jaar |

Verwacht effect op kosten |

Randvoorwaarden voor implementatie (binnen aangegeven tijdspad) |

Mogelijke barrières voor implementatie1 |

Te ondernemen acties voor implementatie2 |

Verantwoordelijken voor acties3 |

Overige opmerkingen |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 Barrières kunnen zich bevinden op het niveau van de professional, op het niveau van de organisatie (het ziekenhuis) of op het niveau van het systeem (buiten het ziekenhuis). Denk bijvoorbeeld aan onenigheid in het land met betrekking tot de aanbeveling, onvoldoende motivatie of kennis bij de specialist, onvoldoende faciliteiten of personeel, nodige concentratie van zorg, kosten, slechte samenwerking tussen disciplines, nodige taakherschikking, et cetera.

2 Denk aan acties die noodzakelijk zijn voor implementatie, maar ook acties die mogelijk zijn om de implementatie te bevorderen. Denk bijvoorbeeld aan controleren aanbeveling tijdens kwaliteitsvisitatie, publicatie van de richtlijn, ontwikkelen van implementatietools, informeren van ziekenhuisbestuurders, regelen van goede vergoeding voor een bepaald type behandeling, maken van samenwerkingsafspraken.

3 Wie de verantwoordelijkheden draagt voor implementatie van de aanbevelingen, zal tevens afhankelijk zijn van het niveau waarop zich barrières bevinden. Barrières op het niveau van de professional zullen vaak opgelost moeten worden door de beroepsvereniging. Barrières op het niveau van de organisatie zullen vaak onder verantwoordelijkheid van de ziekenhuisbestuurders vallen. Bij het oplossen van barrières op het niveau van het systeem zijn ook andere partijen, zoals de NZA en zorgverzekeraars, van belang. Echter, aangezien de richtlijn vaak enkel wordt geautoriseerd door de (participerende) wetenschappelijke verenigingen is het aan de wetenschappelijke verenigingen om deze problemen bij de andere partijen aan te kaarten.

Implementatietermijnen

Voor “sterk geformuleerde aanbevelingen” geldt dat zij zo spoedig mogelijk geïmplementeerd dienen te worden. Voor de meeste “sterk geformuleerde aanbevelingen” betekent dat dat zij komend jaar direct geïmplementeerd moeten worden en dat per 2025 dus iedereen aan deze aanbevelingen dient te voldoen.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerden de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met een galweg- of galblaascarcinoom. De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbeveling(en) uit de eerdere richtlijnmodules (NVvH, 2013) op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door de patiëntenvereniging en genodigde partijen tijdens de schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse. De notulen van de tweede werkgroepvergadering waarin de resultaten van de schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse zijn besproken zijn opgenomen als bijlage. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodules werden aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werden de conceptrichtlijnmodules aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodules werden aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.