Meerwaarde meenemen fysieke fitheid in het oncologisch behandeltraject

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de meerwaarde van het meenemen van fysieke fitheid en fysieke activiteit in het oncologisch behandeltraject?

Aanbeveling

Besteed tijdens het gehele oncologisch traject aandacht aan fysieke fitheid en fysieke activiteit en neem het mee als risicoparameter.

Stimuleer fysieke activiteit:

- Hanteer daarbij de Nederlandse norm gezond bewegen als uitgangspunt, maar in het licht van de situatie en context van de patiënt

- Nederlandse norm gezond bewegen: Volwassenen en ouderen bewegen voldoende wanneer zij 150 minuten (2,5 uur) per week matig intensief bewegen en twee keer per week spier- en botversterkende activiteiten doen. Dit geldt ook voor ouderen, gecombineerd met balansoefeningen

Gebruik als referentiewaarden voor het interpreteren van fysieke fitheid de ‘Prevention first’ referentiewaarden.

Gebruik niet alleen ‘Prevention First’ referentiewaarden voor fysieke fitheid, maar relateer de optimale fysieke fitheid van de patiënt ook aan zijn/haar eigen norm (de fitheid van voor de ziekte) en plaats dit in de context van de ziekte en behandeling.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is een systematisch literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de associatie tussen zowel fysieke fitheid als fysieke activiteit en zowel klinische als maatschappelijke uitkomsten. Fysieke fitheid is nauw geassocieerd met fysieke activiteit. Enerzijds verbetert fysieke fitheid normalerwijs bij meer fysieke activiteit, anderzijds maakt een betere fysieke fitheid meer fysieke activiteit mogelijk. Om fysieke fitheid te kwantificeren zijn over het algemeen inspanningstesten nodig. Dit maakt het meten ervan in grote en langdurige observationele studies of in de klinische praktijk ingewikkelder. Fysieke activiteit is meetbaar met vragenlijsten. Mede daarom zijn er juist ook veel studies die verbanden tussen fysieke activiteit en uitkomstmaten in kaart gebracht hebben. Door de grote hoeveelheid aan beschikbare studies heeft de werkgroep besloten alleen resultaten van recente systematische reviews op te nemen. Er werden 15 systematische reviews en één umbrella review (review van reviews) geselecteerd en uitgewerkt. Volgens de AMSTAR II-tool zijn alle systematische reviews van lage kwaliteit - met uitzondering van de Cochrane review van Knips (2019). Voor alle uitkomstmaten konden de gevonden studies niet gepoold worden, omdat de studies verschillende patiëntengroepen of oncologische ziektebeelden bekijken en de resultaten verschillend gerapporteerd zijn.

Concluderend laten de geïncludeerde studies aanwijzingen zien dat er een associatie is tussen fysieke fitheid en fysieke activiteit en de oncologische uitkomsten. De impact van fysieke fitheid en fysieke activiteit is met name duidelijk door:

Samenhang fysieke fitheid/fysieke activiteit met levensverwachting

Fysieke fitheid en fysieke activiteit hebben bij veel oncologische ziektebeelden een samenhang met de levensverwachting. Vanuit 13 studies met 6.486 volwassenen blijkt dat in een cohort met hoge versus lage fysieke fitheid er een hazard ratio van 0,52 (95% BI 0,35-0,77) is op sterfte door alle oorzaken. Verschillen van 1 metabool equivalent of task (1MET =3,5 ml/kg/min zuurstofopname) resulteren in een hazard ratio van 0,82 (95% BI 0,66-0,99). (Ezzatvar, 2021) Voor patiënten met borst-, dikkedarm- en prostaatkanker wordt een consistent verband met overleving gevonden. (Patel, 2019)

Samenhang fysieke fitheid met fysiek functioneren

Fysieke fitheid heeft een directe relatie tot fysiek functioneren. Het energieverbruik (uitgedrukt in zuurstofopname) dat nodig is voor dagelijkse activiteiten is goed beschreven in het compendium of physical activity waarbij voor allerlei activiteiten de bijbehorende MET waarde is toegekend. (Ainsworth, 2011) Hiermee wordt goed inzichtelijk welke activiteiten de patiënt nog kan uitvoeren met een bepaalde fysieke fitheid.

Samenhang fysieke fitheid en kwaliteit van leven

Fysieke fitheid heeft een belangrijke invloed op de kwaliteit van leven. Als een daling van fysieke fitheid resulteert in onvermogen te kunnen werken en/of om goed zelfstandig te kunnen functioneren heeft dat veel negatieve impact op kwaliteit van leven (Campbell, 2019). Daarnaast heeft fysieke inspanning een positief effect op stemming en versterkt het ook zelfregie in omgaan met de ziekte. Dergelijke verbeteringen in fysieke fitheid zijn goed te behalen met een adequaat trainingsprogramma en persisteren ook op lange termijn. (De Backer, 2008)

Samenhang fysieke fitheid en hart- en vaatziekten

Fysieke fitheid heeft een belangrijke preventieve invloed op hart- en vaatziekten. Mensen die tenminste 5 jaar geleden met kanker zijn gediagnosticeerd hebben afhankelijk van de diagnose en behandeling een 1,3-3,6 toegenomen risico om te overlijden aan cardiovasculaire ziekte mede door cardiovasculaire toxiciteit van behandelingen (Gilchrist, 2019). Fysieke fitheid en fysieke activiteit blijken belangrijke aangrijpingspunten om dit risico te kunnen verlagen (Gilchrist, 2019).

Samenhang fysieke fitheid en complicatie risico bij grote operaties

Lage fysieke fitheid is een belangrijk modificeerbare factor die samenhangt met vergroot risico op complicaties bij grote operaties (Rose, 2022; Mylius, 2021). Een hogere fitheid voor de operatie is geassocieerd met een beter herstel na de operatie en een lagere kans op complicaties, orgaanfalen en vroegtijdig overlijden. Veel gebruikte afkappunten voor een verhoogd risico op ongewenste chirurgische uitkomsten bij majeure chirurgie (complicaties, opnameduur, mortaliteit) liggen voor VO2piek rond de 16-18 ml/kg/min en voor VO2 op VT1 rond de 10-11 ml/kg/min (VSG, 2023/2024; Moran, 2016; Older, 2017; Levett, 2018).

Samenhang fysieke fitheid, lichaamssamenstelling en voeding

Veranderingen in lichaamssamenstelling

Kanker en behandelingen zoals chirurgisch ingrepen, chemotherapie, immuuntherapie en bestraling en de bijkomende inactiviteit, leiden vaak tot veranderingen in lichaamssamenstelling (Wang, 2023; Bozzetti. 2024), wat zich kan uiten in zowel gewichtsverlies als gewichtstoename. Met name ongunstige veranderingen in spiermassa, vetmassa en botdichtheid zijn geassocieerd met slechtere behandelresultaten, een lagere overleving en een verminderde kwaliteit van leven (Wang, 2023; Clemente-Suárez VJ, 2022).

Verlies van spiermassa is een kenmerk van ondervoeding en kan leiden tot sarcopenie en zelfs cachexie (Wang, 2023). Volgens de definitie van de European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), is sarcopenie een leeftijd-afhankelijke afname van spiermassa, spierkwaliteit en spierfunctie (Bauer, 2019). Indien dit samen gaat met een toename van vetmassa wordt dit ook wel sarcopene obesitas genoemd (Bauer, 2019). Cachexie wordt gedefinieerd als een multifactorieel syndroom, waarbij naast sarcopenie ook ongewenst gewichtsverlies van >5% lichaamsgewicht over de laatste 6 maanden is opgetreden (Clemente-Suárez VJ, 2022).

Hoewel beide condities leiden tot spiermassaverlies blijkt uit de literatuur dat er verschillen bestaan in pathogenese. Sarcopenie wordt met name veroorzaakt door inactiviteit, ondervoeding, en neurodegeneratie, terwijl bij cachexie een door de tumor of behandeling ontstane systemische inflammatie op de voorgrond staat (Bozzetti. 2024). Sarcopenie en cachexie kunnen naast elkaar bestaan, vooral bij de oudere patiënt met kanker.

In de spreekkamer kan de lichaamssamenstelling gemeten en opgevolgd worden door middel van het bepalen van de BMI, middelomtrek, huidplooidikte of bio-electrische impedantie (BIA). Nauwkeuriger is het om de lichaamssamenstelling te meten met DEXA, MRI of CT scan (Wang, 2023). Indien er in het kader van de kanker diagnostiek een MRI of CT scan is afgenomen, kan de spiermassa bepaald worden door analyse op het niveau van de derde lumbale wervel of midden van het dijbeen (Wang, 2023).

Voeding en fysieke training zijn effectieve interventies om veranderingen in lichaamssamenstelling tegen te gaan (Wang, 2023). Voedingsinterventies vallen buiten de scope van deze richtlijn, maar staan duidelijk beschreven in de richtlijn ‘Ondervoeding bij patiënten met kanker’ (LWDO, 2012). Men dient een patiënt met kanker met (risico op) ondervoeding te verwijzen naar de diëtist voor individueel voedingsadvies.

Fysieke training is de interventie van eerste keus voor het verbeteren van de spiermassa en botdichtheid en de afname van vetmassa en ontstekingsparameters Wang, 2023). Zowel krachttraining als aerobe training zijn hierin effectief gebleken. Krachttraining leidt tot opbouw van spiermassa, toename van de botdichtheid, afname van ontstekingsparameters, en indirect tot een afname van vetmassa (verhoogd basaal metabolisme bij hogere spiermassa). Aerobe inspanning leidt tot een afname van vetmassa, een toename van de aerobe capaciteit van spierweefsel, en een verlaging van de ontstekingsparameters. Vanwege een toename in energieverbruik is intensieve duurtraining vaak niet de eerste keus bij patiënten met cachexie. Bij deze patiënten ligt de focus met name op een hoog energetisch dieet (met voldoende eiwitten en aangevuld met antioxidanten), gecombineerd met krachttraining (Clemente-Suárez VJ, 2022). Om spieropbouw te faciliteren wordt zowel bij sarcopenie als cachexie een minimale inname van eiwit in de voeding van 1-1,2 g/kg BW/dag aanbevolen (Clemente-Suárez VJ, 2022).

Fysieke fitheid is een potentieel sterkere voorspeller voor mortaliteit dan alom erkende risicofactoren zoals hypertensie, roken, obesitas, hyperlipidemie en diabetes mellitus type 2 en zou volgens de American Heart Association standaard meegenomen moeten worden in de beoordeling en behandeling van patiënten in het algemeen. (Ross, 2016). Ook in de American College of Sports Medicine-aanbevelingen van 2019 wordt geconcludeerd dat er voldoende bewijs is dat fysieke inspanning tijdens de behandeling van kanker verbeteringen kan brengen voor bepaalde oncologische uitkomstmaten zoals vermoeidheid en kwaliteit van leven. (Campbell, 2019; Patel, 2019).

Ook voor de groep van oudere mensen met en na kanker zijn er eenvoudige en toegankelijke maatregelen om het begin van fysieke beperkingen te voorkomen of uit te stellen (Ezzetvar, 2021).

Met betrekking tot fysieke activiteit is het meeste onderzoek uitgevoerd bij vrouwen met borstkanker die met curatieve intentie zijn behandeld. Er is een vrij lineaire dosis-respons relatie gevonden tussen fysieke activiteit uitgedrukt in MET uur en ‘mortaliteit in het algemeen’ (48% lagere overlijdenskans) en borstkanker gerelateerde mortaliteit (38% lagere overlijdenskans) bij fysieke activiteit van 0 tot 20 MET uur waarna een plateau ontstaat (Cariolou, 2021).

|

De MET-waarde geeft een indicatie van hoe zwaar een inspanning is. Dit wordt uitgedrukt in het verbruik van zuurstof per kg lichaamsgewicht per minuut. Eén MET is gelijk aan 3,5 ml zuurstof per kg lichaamsgewicht per minuut. De MET-waarde van lichamelijke activiteiten varieert van 0,9 MET (bij slaap) tot 18 MET (zeer zware inspanning). Naast intensiteit is ook de tijdsduur van inspanning van belang om fysieke activiteit te kwantificeren. Zo kom je tot MET uur. Het optimum ligt op 20 MET uur (dit komt overeen met bijvoorbeeld 6 uur wandelen per week op een normaal tempo). |

Hoewel veelbelovend, zijn de geïncludeerde onderzoeken vaak beperkt door de observationele opzet met een hoog risico op vertekening, onder andere door het gebruik van zelfrapportage metingen van fysieke activiteit. Het meeste onderzoek is gedaan bij de veel voorkomende kankersoorten zoals borst – en darmkanker. De heterogeniteit van kanker als ziekte, maakt het onduidelijk of de bevindingen ook in dezelfde mate gelden voor alle andere vormen van kanker. Daarnaast kunnen variaties bestaan in het gebruik van bijvoorbeeld cardiorespiratoire testen, en daarmee ook variaties in afkappunten of drempels om patiënten in de laagste of hoogste fitnesscategorieën te identificeren. Verdere prospectieve onderzoeken met gestandaardiseerde cardiorespiratoire fitheidstesten zijn daarom zinvol om nog beter getalsmatig inzicht te krijgen in de verbanden.

Een belangrijke kanttekening bij de gevonden associatie tussen vermoeidheid en lichamelijke activiteit zou kunnen zijn dat er de kans is op omgekeerde oorzakelijkheid. Dat wil zeggen dat personen die kanker hebben, zich meer vermoeid kunnen voelen of meer ziektelast ervaren, en daardoor minder lichamelijk actief zijn (Piercy, 2018). Binnen epidemiologisch onderzoek is dit onderscheid niet of nauwelijks te maken. Dat was voor de U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee (PAGAC) de reden om slechts een beoordeling van matig of lager toe te kennen aan de associaties tussen fysieke fitheid/fysieke activiteit en overleving voor de drie kankersoorten colorectaal, borst, prostaat. (McTiernan, 2019) De vraag omtrent oorzakelijkheid is gezien methodologische beperkingen met observationeel onderzoek niet goed te achterhalen. Gerandomiseerde studies naar de effecten van fysieke inspanningsinterventies zijn hiervoor nodig. Dergelijke trainingsstudies zijn ook gedaan en in een meta-analyse bij 31 studies (van Vulpen, 2020) kon bij 3.846 patiënten het effect van fysieke inspanning op vermoeidheid worden onderzocht. Gemiddeld genomen werd een matig effect van training op vermoeidheid gevonden. Ook bleek dat er een relatie was tussen aard van training en effect, waarbij gesuperviseerde training substantieel meer effect gaf. Dit geeft dus sterke aanwijzing dat vermoeidheid beïnvloedbaar is door training.

Klinische overwegingen

Verandering in fysieke fitheid en activiteit bij mensen met en na kanker

Bij mensen die behandeld worden voor kanker is er veel kans op daling van fysieke fitheid door ziekte of behandeling. Er kunnen veranderingen optreden in spiermassa door katabool effect van ziekte en/of behandeling in combinatie met (mede door ziekte versterkte) fysieke inactiviteit en inadequate op- of inname van voedingstoffen. Frequent is er anemie ten gevolge van chemotherapie of ziekte met verlaging van belastbaarheid. Skeletspieren adapteren snel aan training, maar ook aan inactiviteit. Ze zijn gevoelig voor bijwerkingen van celdeling remmende therapie (zoals b.v. chemotherapie) en voor de katabole bijwerking van hormonale therapie (b.v. corticosteroïden die vaak gegeven worden als ondersteuning bij chemokuren en de hormoontherapie bij mammacarcinoom en prostaatcarcinoom, na ovariëctomie en/of hormonale depletie door radiatie van het kleine bekken). Dit kan resulteren in forse dalingen in fysieke fitheid wat ook blijkt uit diverse studies. Bij patiënten behandeld voor borstkanker met gemiddelde leeftijd 40-50 jaar werd een cardiorespiratoire fitheid gevonden die 30-32% lager was dan bij op leeftijd vergelijkbare controles. (Jones, 2012) Dit is ook vastgesteld bij jonge volwassenen na kanker en gynaecologische tumoren (Miller, 2013; Peel, 2014; Peel 2015).

In de meeste gevallen is er door ziekte of behandeling geen blijvende beperking in de functie van hart en longen, of bloedsamenstelling wat tot structurele (niet of beperkt beïnvloedbare) daling in fysieke fitheid zou kunnen leiden. De beperking blijkt met name op spierniveau en is daarom in potentie ook trainbaar. Echter spelen bij deconditionering ook mentale processen zoals aanpassingsstoornis en coping problematiek, angsten en PTSS die aansluitend aan oncologische behandelingen normaal beweeggedrag kunnen belemmeren.

Tussen gezonde personen is er normaal gesproken een forse variatie in fysieke fitheid. Fysieke fitheid kan daarom niet alleen geïndexeerd worden naar de norm, maar moet ook in het perspectief gezet worden van het individu. In de oncologie is de fysieke fitheid voor de ziekte, indien bekend, dan een goed uitgangspunt.

In de oncologie is aandacht voor fysieke fitheid en activiteit hard nodig omdat kanker en de behandeling ervan een forse impact heeft op deze aspecten. Bij patiënten die bedlegerig zijn bijvoorbeeld, neemt de spierkracht met ongeveer 0.5% per dag af. Gezien de diversiteit in stadium van ziekte en behandeling, aanwezige beperkingen en aangrijpingspunten voor training is er advies op maat nodig vanuit een deskundige op het gebied van training en beweging binnen de oncologische zorg.

Welke hoeveelheid bewegen is optimaal?

Voor zorgverleners kan het zinvol zijn om de beweegadviezen voor mensen met en na kanker in verhouding te zien tot de meer algemene Nederlandse norm gezond bewegen.

|

Volwassenen en ouderen bewegen voldoende wanneer zij 150 minuten (2,5 uur) per week matig intensief bewegen en twee keer per week spier- en botversterkende activiteiten doen. Dit geldt ook voor ouderen, gecombineerd met balansoefeningen |

Nederlandse norm gezond bewegen (Beweegrichtlijnen)

Deze Nederlandse norm gezond bewegen lijkt ook voor mensen met en na kanker een goed vertrekpunt mits haalbaar in context van ziekte en behandeling.

Het optimum zal waarschijnlijk hoger liggen omdat uit epidemiologische studies (Cariolou, 2021) een maximaal effect van bewegen gevonden wordt bij 20 MET uur wat overeen komt met circa 30 km wandelen wat bij een normale wandelsnelheid overeenkomt met 6 uur per week fysiek actief zijn.

Fysieke fitheid en referentiewaarden

Fysieke fitheid kan gerelateerd worden aan een referentiepopulatie, waarbij gecorrigeerd moet worden voor leeftijd, gewicht, geslacht en afkomst. Er zijn hiervoor in de literatuur vrij sterk verschillende referentiewaarden. In het verleden gehanteerde normwaarden van Jones en Wasserman worden soms nog gebruikt, maar zijn achterhaald omdat ze gebaseerd zijn op een te kleine populatie van met name minder fitte mensen wat leidt tot lage waarden (Jones, 1985; Wasserman, 2005). In de richtlijn hartrevalidatie wordt het ‘Prevention first’ register geadviseerd. Dit betreft een populatie van 10.090 Duitse individuen die in kader van bedrijfskeuringen bij gezonde werknemers getest zijn (6.462 man en 3.628 vrouw) variërend in leeftijd van 21 tot 83 jaar (Rapp, 2018).

Figuur 3 Nomogram van percentiel referentiewaarde relatieve VO2peak, per geslacht (overgenomen uit Rapp 2018)

Daarnaast is er in Nederland ook de Lowlands Fitness Registry. (van der Steeg, 2021) Dit omvat een populatie van 3.671 mannen en 941 vrouwen met name vanuit sportmedische onderzoeken bij waarschijnlijk sportief actieve personen, resulterend in normwaarden in de range van 10-65 jaar in leeftijd. De normwaarden van Lowland liggen bij mannen circa 4-6 mlO2/kg/min hoger dan bij het Prevention First cohort en bij vrouwen liggen ze 1-4 mlO2/kg/min hoger. Als werkgroep adviseren we het Prevention first cohort omdat dit waarschijnlijk een betere afspiegeling is van de gemiddelde gezonde persoon.

Omdat er tussen gezonde individuen grote verschillen in fysieke fitheid kunnen zijn is het ook nodig om de actuele fysieke fitheid bij een patiënt te relateren aan zijn fitheid voor de ziekte en dit te plaatsen in de context van ziekte en stadium van de behandeling.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

De substantiële associaties van fysieke fitheid met levensverwachting, functioneren, kwaliteit van leven, bijwerkingen van de oncologische behandeling en voorkomen van hart- en vaatziekten zijn alle belangrijk vanuit patiëntperspectief. Het is belangrijk dat patiënten hierover geïnformeerd worden. Als er beperkingen of problemen zijn voor fysieke inspanning is het belangrijk dat dit onderkend wordt en advies of hulp op maat gegeven wordt.

In een meta-synthese van 40 kwalitatieve studies beschrijft Burke (2017) de perspectieven van mensen na kanker op de relatie tussen fysieke activiteit en kwaliteit van leven. Ongeacht de diagnose (d.w.z. stadium, kankertype) en behandelingsstatus bleek dat fysieke activiteit een positieve invloed had op vier dimensies van de kwaliteit van leven van mensen na kanker: lichamelijk (bijv. omgaan met de lichamelijke gevolgen van kanker en de behandeling ervan), psychologisch (bijv. het oproepen van een positief zelfbeeld), sociaal (bijv. je begrepen voelen door anderen) en spiritueel (bijv. herdefiniëren van het levensdoel).

De werkgroep is van mening dat behoud of verbetering van fysiek fitheid en fysieke activiteit tijdens en na een oncologische behandeling zowel het fysieke als het mentale welzijn bevordert. Waardoor men (weer) maatschappelijk actief kan worden en/of (weer) aan het werk kan gaan. Om zo volop in het leven te kunnen (blijven) staan.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

De werkgroep ziet als knelpunt dat niet alle zorgverleners en patiënten zich bewust zijn van de waarde van fysieke fitheid en fysieke activiteit en de invloed hiervan op symptomen, complicaties en bijwerkingen van behandeling, en hiermee ook de kwaliteit van leven van patiënten, iets dat ook uit de knelpunteninventarisatie naar voren kwam. Daarom wordt in deze richtlijnmodule de meerwaarde van fysieke fitheid en fysieke activiteit tijdens het medisch behandeltraject van kanker beschreven, zodat zowel de behandelaar als de patiënt op de hoogte zijn van het belang ervan.

Samenvatting literatuur

For the international exchange of this literature review, the next part is written in English.

Description of systematic reviews not focusing on a specific tumor type

1. Cardiorespiratory fitness

Ezzatvar (2021) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to characterize the association between cardiorespiratory fitness and all-cause mortality in adults diagnosed with cancer. They included 13 prospective cohort studies, a total of 6,486 adults diagnosed with cancer (31.4% female) with a mean age of 58.5 years. Cardiorespiratory fitness was measured using cardiopulmonary exercise testing, exercise tolerance tests, the 6-min walk distance (6MWD), or the stair-climbing test, and was analysed through the measurement of peak oxygen uptake (VO2 peak), maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max), estimation of metabolic equivalent tasks (METs) or climbing and walking distance. The strength of evidence for the association between cardiorespiratory fitness and risk of all-cause mortality was low and very low (GRADE).

Patients undergoing surgery

Steffens (2021) analysed the association between preoperative cardiorespiratory exercise test (CPET) variables – such as peak VO2, anaerobic threshold and ventilatory equivalent for carbon dioxide – and postoperative complication rates, length of hospital stay, and quality of life in patients undergoing cancer surgery. This systematic review included a total of 58 published articles (including 52 unique cohorts). The heterogeneity of the included cohorts, including the lack of consistency in reporting or standardisation of outcomes has prevented the pooling of a larger number of studies and a stronger conclusion across the identified reviews. Risk of bias of the included studies was assessed using the Quality in Prognostic Studies (QUIPS) tool. Overall, most studies were rated as having low risk of bias. Limitation of this systematic review included the heterogeneity between the included studies, which made a meta-analysis impossible. Furthermore, peak VO2 and VO2-max were used in this review interchangeably.

2. Physical functioning

Older adults

Ezzatvar (2021) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the prospective association between objectively measured physical function and all-cause mortality in older adults (60+) diagnosed with cancer. They included 25 prospective cohort studies with a total of 8,109 adults diagnosed with cancer (51.7% female) with a mean age of 66.8 years. All included studies had to measure physical function using a functional test (e.g., timed up and go test, TUG), a battery of tests (e.g., the short physical performance battery, SPPB) or a validated muscle strength test (e.g., handgrip test) or similar. The included studies were heterogeneous regarding patients (i.e., cancer type) and treatments and were heterogeneous regarding the assessment of functional status, as well as different cutoff points within studies to classify physical function status.

3. Physical activity

McTiernan (2019) conducted a review of reviews based on systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and pooled analyses that examined the relationship between physical activity and risks of mortality among persons diagnosed with cancer. These updated systematic literature searches were conducted for the inclusive dates January 2016 through February 2018. The evidence of the 18 included studies was graded based on criteria such applicability, generalizability, risk of bias and study limitations, quantity and consistency of the results across studies as well as the magnitude and precision of the effects. In the studies included in the meta-analyses, physical activity was measured by self-report, with different types of physical activity questionnaires. Given the varying methods of physical activity assessment and classification in source papers and meta-analyses, the Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee in the U.S. (PAGAC) could not determine the specific levels of physical activity that correspond to the reported levels of risk reduction. Furthermore, most of the studies in persons diagnosed with cancer did not control adequately for treatment type or completion, nor for undiagnosed progression of disease, all of which can interfere with physical activity ability and therefore could have been major confounders of the relationships between physical activity and cancer survival.

Friedenreich (2019) evaluated the association between prediagnosis and postdiagnosis physical activity and survival (primary outcomes: cancer-specific mortality, all-cause mortality, and cardiovascular disease related mortality) for all cancer and by specific cancer sites by using data from all available observational epidemiologic studies and randomized controlled trials. Secondary objectives included assessing these associations by sex, BMI, menopausal status, and colorectal cancer subtype; evaluating the associations between different domains of physical activity (i.e., total, recreational [leisure time], occupational, household activities) and survival outcomes; and determining the dose-response relationship between physical activity (PA) and cancer survival. The quality of the studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale, with a score of >7 defined as high quality. Of the 136 included studies, the majority was of high quality, with 38 studies receiving perfect scores. Limitations of this meta-analysis include the heterogeneous physical activity assessment methods.

Wang (2019) conducted a meta-analysis to identify whether physical activity, even a low level of physical activity, could reduce the mortality of various cancer patients. Postdiagnosis physical activity (e.g., leisure-time physical activity, recreational physical activity, exercise, sports, etc.) was compared to no physical activity. Nine studies (cohort study or case-control studies), involving a total of 21,811 participants, were included in this meta-analysis. The Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale was used to assess the quality of these studies. Assessment of heterogeneity was performed using Cochran’s Q test and Higgins’s I2. Potential publication bias was evaluated using Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test.

Patients undergoing surgery

Steffens (2019) conducted a systematic review to investigate if preoperative physical activity levels in patients undergoing cancer surgery is associated with postoperative complication rates, length of hospital stay, and quality of life. Thirteen studies with a longitudinal design (cohort studies, clinical trials, case series, and case-control studies) reporting objective (e.g., accelerometer) or subjective (e.g., self-reported questionnaire) measures of physical activity levels preoperatively were included. Their risk of bias was assessed using the Quality in Prognostic Studies (QUIPS) tool. Most studies were rated as having low or moderate risk of bias.

Advanced cancers

Takemura (2021) systematically evaluated and synthesized the effects of post-diagnosis physical activity on overall mortality in patients with advanced cancer from all available non-randomised studies and RCTs. The outcome of interest in this systematic review was survival, measured at the end of the follow-up period through outcome measurements including survival probability, disease-free survival, cancer-specific mortality, and overall mortality. The included studies assessed the engagement in physical activity, or physical activity was the intervention or a component of an intervention. A total of 14 studies were included in the qualitative synthesis, with 11 of the 14 studies included in the meta-analysis. The methodological quality of the included RCTs was low, while it was high for the included non-RCTs.

|

Publication |

# included studies |

Type of cancer |

Physical fitness |

Physical activity |

Outcome measure |

Association |

Strength of association |

AMSTAR* |

|

Ezzetvar, 2021 |

13 (6,486 patients) |

All |

Cardiorespiratory fitness measured directly using a cardiorespiratory exercise test, an exercise tolerance test (e.g., standard Bruce Protocol procedure) or estimated via functional fitness tests (e.g., six-minute walk distance) |

|

All-cause mortality or overall survival |

Independent negative association between cardiorespiratory fitness and all-cause mortality in adults diagnosed with cancer. |

All cancers: HR = 0.52 (95% CI: 0.35-0.77) for all-cause mortality Lung cancer: HR = 0.62 (95% CI: 0.46–0.83) for all-cause mortality

|

Low quality |

|

Steffens, 2021 |

52 (10,030 patients) |

All |

Preoperative CPET variables, including peak oxygen uptake (peak VO2), anaerobic threshold (AT), or ventilatory equivalent for carbon dioxide (VE/VCO2), |

|

Postoperative outcomes (complications, length of stay) |

Superior preoperative CPET values, especially peak VO2, were significantly associated with improved postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing cancer surgery |

MD: 2.28 (95% CI: 1.26–3.29) for absence of complications between high and low peak VO2 |

Low quality |

|

Ezzetvar, 2021 |

25 (8,109 patients) |

All; older adults |

Physical function measured using a functional test (e.g., TUG), a battery of tests (e.g., SPPB) or a validated muscle strength test (e.g., handgrip test) or similar |

|

All-cause mortality |

Higher physical function favors reduced risk in all-cause mortality among older adults diagnosed with cancer, regardless of age, follow-up duration, and cancer type |

HR = 0.45 (95% CI: 0.35–0.57; I 2 = 88.6%) for overall physical function and all-cause mortality |

Low quality

|

|

McTiernan, 2019 |

6 meta-analyses for breast cancer 6 meta-analyses for colorectal cancer 3 meta-analyses for prostate cancer |

Breast, colorectal, prostate |

|

-all types and intensities of physical activity, -physical activity was measured by self-report, with different types of physical activity questionnaires |

Cancer-specific mortality

All-cause mortality |

Moderate or limited associations between greater amounts of physical activity and decreased all-cause and cancer-specific mortality Considerable chance of reverse causation (individuals who have cancer may feel more fatigue and be less physically active) |

Breast cancer: relative risk reduction of 48% for all-cause mortality Colorectal cancer: relative risk reduction of 42% for all-cause mortality Prostate cancer: relative risk reduction of 37-49% for all-cause mortality |

Low quality

|

|

Friedenreich, 2019 |

64 (for all-cause mortality) |

All |

|

Different domains of PA (i.e., total, recreational [leisure time], occupational, household) |

Survival, mortality

Recurrence, progression |

Strong evidence that PA before or after cancer diagnosis was associated with statistically significant decreased hazards of cancer-specific and all-cause mortality in at least 11 different cancer sites. |

Pre-diagnosis physical activity: HR = 0.47 – 0.91 for different tumor types for all-cause mortality

Post-diagnosis physical activity: 0.58-0.96 for different tumor types for all-cause mortality |

Low quality

|

|

Wang, 2019 |

9 (21,811 patients) |

All |

|

Postdiagnosis physical activity (e.g., leisure-time physical activity, recreational physical activity, exercise, sports, etc |

Mortality |

Physical activity significantly reduced the mortality by 34%, compared with no physical activity |

HR = 0.66 (0.58 to 0.73) for all-cause mortality |

Low quality

|

|

Steffens, 2019 |

13 (5,523 patients) |

All |

|

Objective (e.g. accelerometer) or subjective (e.g. self-reported questionnaire) measures of PA level preoperatively

|

Postoperative outcome measure including complication rate, LOS or QoL |

Higher preoperative PA level was associated with shorter LOS (OR: 3.66; 95%CI: 1.38 to 9.69) and better postoperative QoL (OR: 1.29; 95%CI: 1.11 to 1.49), but not with reduced postoperative complications |

Absence of postoperative complications: OR = 2.60 (95% CI: 0.59 to 11.37)

Shorter LOS: OR = 3.66 (95% CI: 1.38 to 9.6)

Postoperative QOL: OR = 1.29 (95% CI: 1.11 to 1.49) |

Low quality

|

|

Takemura, 2021 |

11 (2,876 patients) |

All |

|

Assessment of engagement in physical activity or physical activity as the intervention or a component of intervention (aerobic and resistance training /RCTs, self-administered questionnaires or questions, accelerometers) |

Survival |

Post-diagnosis physical activity had no effect on the overall survival among advanced cancer patients |

log HR = −0.18 (95% CI: − 0.36 to 0.01) Separately for non-randomised trials: log HR = − 0.25 (95% CI: −0.44, − 0.06)

Separately for randomised trials: log HR = 0.08 (95% CI: −0.17, 0.32) |

Critically low quality |

*AMSTAR II instrument: see the table with results of the quality assessment under the tab Methods

Description of systematic reviews focusing on a specific tumor type

1. Cardiorespiratory fitness

No tumor specific systematic reviews evaluating the association between cardiorespiratory fitness and oncological outcome were included in this review.

2. Physical function

No tumor specific systematic reviews evaluating the association between physical function and oncological outcome were included in this review.

3. Physical activity

Colorectal cancer

Choy (2022) provided a systematic review of the evidence of the association between physical activity and colorectal cancer (CRC) survival. Inclusion criterion was the adult population after curative resection (R0) of non-metastatic CRC. Thirteen non-randomised studies were included in this review, of which two looked at pre-diagnosis levels, five looked at postdiagnosis activity levels, and six looked at both pre- and postdiagnosis activity levels. The quality of these studies was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality assessment scale. The quantification of physical activity differed slightly between all included studies, but most studies utilized the MET score. As the main aim of the study was to quantify the survival benefits of physical activity in colorectal cancer, the various categories of physical activity were standardized. This also allows to demonstrate any possible dose-related changes in survival outcomes. Substantial study heterogeneity was found in several outcomes. This can limit the interpretability of the pooled estimates.

Qiu (2018) conducted a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies to estimate the association physical activity with overall and colorectal cancer-specific mortality. Dose–response analysis was performed based on the data for categories of physical activity levels on median dose, number of cases, and participants. Eighteen prospective cohort studies were included. Assessment of physical activity was based on self-reported information in 14 of 18 studies. The risk of bias in these individual studies was assessed using the Quality In Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) tool. The overall risk of bias was low to moderate. Heterogeneity among studies was estimated using Higgins’s I2; publication bias was assessed by using funnel plots and the further Begg’s adjusted rank correlation and Egger’ regression asymmetry tests.

Breast cancer

Cariolou (2022) presents evidence on postdiagnosis physical activity and breast cancer outcomes (all-cause mortality, breast cancer-specific mortality and recurrence). This review is an update of the assessment of the available evidence on physical activity and breast cancer prognosis from the Global Cancer Update Programme (CUP Global) from 2012 and 2018. They searched for peer-reviewed observational studies or randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in women diagnosed with primary breast cancer during adulthood up to 31st October 2021. 28 studies were included which reported results of physical activity either in h/week or MET-h/w, assessed via self-reported or interview-based validated questionnaires. The quality of individual studies was not graded using a specific tool. Instead, relevant study characteristics that could be used to explore potential sources of bias were included into the CUP Global database. The Expert Panel concluded that the observed dose-response relationship for all-cause and breast cancer-specific mortality was limited by the methodological quality of the studies. The diversity of breast cancer subtypes and patient characteristics could not be appropriately assessed in the available studies, and control of treatment completion was considered inadequate.

Lee (2019) conducted a meta-analysis to examine the association between physical activity and the risk of death in breast cancer survivors and its dependency on physical activity intensity and amount of physical activity changes after breast cancer diagnosis. They included 24 studies in the meta-analysis: 17 studies for prediagnosis analysis, 12 studies for postdiagnosis analysis, and 3 studies for both pre- and postdiagnosis analyses. The amount of physical activity was divided into 3 groups based on an average amount of physical activity found in the studies: low amount of physical activity (˂300min/week), moderate amount of physical activity (300-500min/week), and high amount physical activity (>500min/week). Physical activity intensity was reported in the selected studies by self-reported responses to physical activity questionnaires. The Q statistic was used to assess the statistical heterogeneity across the sampled studies (P ˂.10 was significant), and the I2 statistic was used to quantify inconsistency.

Hematological malignancies

Knips (2019) updated the original Cochrane review published in 2014 and re-evaluated the efficacy, safety and feasibility of aerobic physical exercise for adults suffering from hematological malignancies considering the current state of knowledge. They included RCTs comparing an aerobic physical exercise intervention, intending to improve the oxygen system, in addition to standard care, as well as studies that evaluated aerobic exercise in addition to strength training. Outcomes were adverse events, mortality and 100-day survival, standardized mean differences (SMD) for quality of life (QoL), fatigue, and physical performance. They excluded studies that investigated the effect of training programmes that were composed of yoga, tai chi chuan, qigong or similar types of exercise, studies exploring the influence of strength training without additional aerobic exercise as well as studies assessing outcomes without any clinical impact. The review authors searched for studies that had been published up to July 2018.

Lung cancer

Teba (2022) performed a systematic review that aimed at exploring the relationship between engaging in regular physical activity and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients with lung cancer. They also examined the relationship between physical activity and other PROMs. The study included one cohort study, one randomised controlled trial, 15 cross-sectional studies and six case series. Most studies quantified physical activity using subjective measurements, such as questionnaires. Overall, HRQoL was assessed in most of the studies through validated questionnaires, such as the EORTC-QLQ-C30. A total of 5,665 lung cancer patients with a mean age of 65.6 years participated in the studies and half were women (50.5%).

Melanoma

Crosby (2021) systematically reviewed and examined the associations or effects of physical activity and exercise on quality of life (QoL) as the primary outcome, and other objectively measured (body composition, cardiorespiratory fitness, and physical function), and patient-reported (fatigue, treatment-related side-effects, cognitive function, and psychological distress) outcomes among patients with melanoma. This narrative/qualitative synthesis included six studies (two cross-sectional surveys, two were retrospective analyses, two were non-randomized intervention trials) with a total of 882 patients with melanoma, aged 20 to 85 years). The quality of all included studies was assessed using the McMaster University Critical Appraisal Tool for Quantitative Studies. Among the included studies, the effects of both physical activity behaviour and physical activity/exercise interventions were explored.

Pancreatic cancer

Luo (2021) conducted a systematic review to examine the effects of exercise training in patients with pancreatic cancer. The primary end point was the reported change in QoL outcomes measured at different follow-up periods. Nine papers based on seven trials were included in the analysis. Risk of bias assessment of all included studies was evaluated using the McMaster University Critical Appraisal Tool for Quantitative Studies due to the diversified quantitative research designs of the included studies. Most trials offered supervised or home-based resistance and aerobic exercise.

|

Publication |

# included studies |

Type of cancer |

Cardiorespiratory fitness |

Physical activity |

Outcome measure |

Association |

Strength of association |

AMSTAR* |

|

Choy, 2022 |

13 (19,135 patients) |

CRC |

|

Metabolic equivalent task (MET) score |

Survival |

Moderate physical activity per week is associated with a significantly decreased risk of overall mortality in CRC patients |

Moderate activity group: HR = 0.82 (95% CI: 0.74–0.90) for overall survival

High activity group: HR = 0.64 (95% CI: 0.56–0.72 for overall survival |

Low quality |

|

Qiu, 2018 |

18 (31,873 patients) |

CRC |

|

Self-reported |

Survival

CRC specific mortality |

CRC survivors who engaged in PA before or after diagnosis of a cancer might have a better total and CRC-specific survival than those who were physical inactive. |

Prediagnosis physical activity: HR=0.81 (95% CI: 0.76–0.87) for total mortality

HR=0.85 (95% CI: 0.77–0.98) for colorectal cancer specific mortality

Postdiagnosis physical activity: HR=0.63, 95% CI: 0.54–0.74 for total mortality

HR=0.64 (95% CI: 0.47–0.88) for colorectal cancer specific mortality |

Low quality

|

|

Cariolou, 2022 |

23 |

Breast |

|

(MET)-h/w, assessed via self-reported or interview-based validated questionnaires |

All-cause mortality

Breast cancer-specific mortality

Recurrence |

Higher levels (up to 20 MET-h/week) of postdiagnosis recreational physical activity were associated with a 48% lower all-cause and a 38% lower breast cancer-specific mortality |

HR per 10 MET-h/week = 0.85 (95% CI: 0.78-0.92) for all-cause mortality

Highest versus lowest physical activity level: HR = 0.56 (95% CI: 0.49-0.64) for all-cause mortality

HR per 10 MET-h/week = 0.86 (95% CI: 0.77-0.96) for breast cancer specific mortality

Recurrence: no data available |

Low quality

|

|

Lee, 2019 |

24 (144,224 patients) |

Breast |

|

- Physical activity categorized as low (<300 min/wk), moderate (300-500 min/wk) or high (>500 min/wk) |

All-cause mortality

Breast cancer-specific mortality |

- Prediagnosis and postdiagnosis PAs were associated with reduced BCM and M - decreasing PA may lead to a worse prognosis of BC |

Prediagnosis physical activity: RR = 0.87 (95% CI: 0.78-0.96) for moderate versus low amount for breast cancer related mortality and RR of 0.78 (95% CI, 0.71-0.85) for all-cause mortality

RR = 0.80 (95% CI: 0.72-0.89) for high versus low amount for breast cancer related mortality and 0.74 (95% CI, 0.68-0.80) for all-cause mortality

Postdiagnosis physical activity: RR = 0.72 (95% CI, 0.62-0.83) for moderate versus low amount for breast cancer related mortality and 0.74 (95% CI, 0.66-0.83) for all-cause mortality

RR = 0.71 (95% CI, 0.64-0.78) for high versus low amount for breast cancer related mortality and 0.61 (95% CI, 0.56-0.66) for all-cause mortality |

Low quality

|

|

Knips, 2019 |

18 (1,892) |

Haematological cancer |

|

-aerobic physical exercise in addition to standard care (exercise interventions such as moderate cycling, walking, Nordic walking, running, swimming and other related forms of sport) further physical - moderate strength training in addition to the aerobic exercise programme |

Overall survival (OS)

Quality of Life

Physical functioning/

QoL

Depression

Anxiety/ Fatigue |

Aerobic physical exercise in addition to standard care probably improves fatigue and depression. There is currently no evidence for differences in terms of mortality, quality of life, physical functioning and anxiety between people exercising and the control group. |

RR = 1.10 (95% CI 0.79 to 1.52) for all-cause mortality

SMD = 0.31 (95% CI: 0.13 to 0.48) for fatigue |

High quality

|

|

Teba, 2022 |

23 (5,665 patients) |

Lung cancer |

|

physical activity behaviour (either self-reported or objectively) -regular spontaneous PA (no exercise-based interventions) |

health-related quality of life (HRQoL),

Mood, symptoms (fatigue, dyspnoea) |

Small to moderate associations between engaging in physical activity and overall better HRQoL, less symptom burden and better mood. |

Pearson’s r=0.41 (95% CI: 0.21 – 0.57) for global HRQoL

Pearson’s r=-0.23 (95% CI: -0.3, -0.17) for fatigue |

Low quality

|

|

Crosby, 2021 |

6 (882 patients) |

Melanoma |

|

Surveys on physical activity behaviour, self-guided aerobic exercise program |

Quality of Life

Fatigue

Physical function |

Physical activity/exercise did not adversely impact the objectively measured or patient-reported outcomes of patients with melanoma |

No meta-analyses performed |

Low quality

|

|

Luo, 2021 |

7 (201 patients) |

Pancreatic |

|

Supervised or home-based resistance and aerobic exercise. |

Quality of Life

Cancer-related fatigue

Psychological distress

Physical function |

Given the current evidence, exercise training seems to be safe and feasible and may have a favourable effect on various physical and psychological outcomes in this patient group. |

No meta-analyses performed |

Low quality

|

*AMSTAR II instrument: see the table with results of the quality assessment under the tab Method

Results

Outcome 1- Overall survival

Cardiorespiratory fitness

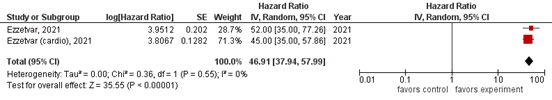

Two studies studied the association between cardiorespiratory fitness and overall survival (Figure 1).

Ezzatvar (2021) showed that for individuals in the category of high cardiorespiratory fitness, mortality was lower compared to those in the low cardiorespiratory fitness group, independent of cancer type (HR=0.52; 95% CI:0.35–0.77; p=0.005; I2=77.6%).

Physical function

For the group of older people with cancer (>60 years), Ezzatvar (2021) found that higher levels of physical function (short physical performance battery, HR=0.44, 95% CI: 0.29–0.67; I2 = 16.0%; timed up and go, HR=0.40, 95% CI: 0.31–0.53; I2 =61.9%; gait speed, HR=0.41, 95% CI 0.17–0.96; I2=73.3%; handgrip strength: HR=0.61 95% CI: 0.43–0.85, I2=85.6%; and overall, HR = 0.45 95% CI: 0.35–0.57; I2=88.6%) were associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality compared to lower levels of functionality.

Figure 1: Association between cardiorespiratory fitness and overall survival

Physical activity

Eleven studies studied the association between physical activity and overall survival, however, not all of these studies present results as hazard ratios (Figure 2).

The results of Friedensreich (2019) show reduced hazards of cancer-specific mortality for those in the highest vs lowest levels of prediagnosis and/or postdiagnosis physical activity for all cancers combined (prediagnosis: HR=0.82, 95% CI: 0.79-0.86, and postdiagnosis: HR=0.63, 95% CI=0.53-0.75, respectively. Hazard ratios were reduced for both men and women, those with lower BMI (<25 kg/m2), and prediagnosis and postmenopausal women (except for the association for premenopausal women and breast cancer-specific mortality).

The meta-analysis of Wang (2019) demonstrated that higher postdiagnosis physical activity, no matter the level of the physical activity, was significantly associated with a 34% lower mortality, compared with no physical activity. The results also suggested that cancer survivors with a low level of physical activity had a 40% lower in mortality risk.

For breast cancer McTiernan (2019) shows a consistent inverse association between level of physical activity after diagnosis and cancer-specific and all-cause mortality in breast cancer survivors. Estimates vary between 27% and 48% reduction in risk for all-cause mortality and 25% and 38% reduction in risk for breast cancer specific mortality. Cariolou (2022) found that recreational physical activity was associated with lower risk of all-cause mortality (HR = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.49-0.64). In their linear dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies they found that each 10-unit increase in MET-h/week of recreational physical activity was associated with 15% and 14% lower risk of all-cause (95% CI: 8%-22%) and breast cancer-specific mortality (95% CI: 4%-23%), respectively. The meta-analysis of Lee (2019) showed that prediagnosis and postdiagnosis physical activity were associated with reduced breast-cancer specific (RR=0.58 95% CI: 0.39-0.90) and all-cause mortality (RR=0.53 (95% CI: 0.38-0.75). Additional findings show that moderate-intensity physical activity and high levelsof physical activity, both prediagnosis and postdiagnosis, had stronger associations with the risk of death than other intensities and amounts of physical activity.

For colorectal cancer McTiernan (2019) found a consistent inverse association between levels of physical activity after diagnosis and all-cause mortality (risk reduction between 15% and 42%) and colorectal cancer-specific mortality in colorectal cancer survivors (25%-50%). Choy (2022) found that physical activity was associated with an 18% to 36% reduction in overall mortality when compared to negligible activity. This was also reflected in cancer specific survival analysis. Qiu (2020) observed that the highest versus the lowest levels of prediagnosis physical activity showed decreased risks of all-cause mortality (summary HR=0.81, 95% CI: 0.76–0.87, I2=1.8%). Each 10 MET-h/week increase in prediagnosis physical activity was related to an 11% (95% CI: 3–17%; P<0.001, I2 =86.9%) and 9% (95% CI: 2–16%; P=0.002, I2=74.1%) reduction in risk of overall mortality and CRC specific mortality among CRC survivors, respectively.

For prostate cancer McTiernan (2019) showed an inverse association between physical activity levels postdiagnosis and cancer-specific mortality in prostate cancer survivors (37%-49% risk reduction in all-cause mortality, 38% risk reduction in prostate cancer-specific ortality).

For patients with advanced cancer, the meta-analysis of Takemura (2021) showed that compared with the reference group (lower-level physical activity or control group), higher-level physical activity was not significantly associated with a lower risk of earlier mortality in advanced cancer patients (Log transformed hazard ratio InHR= −0.18, 95% CI: − 0.36-0.01). A separate meta-analysis showed that study type influenced the heterogeneity between studies: a higher level of physical activity significantly associated with a lower overall mortality in non-randomized trials, whereas the result remained insignificant for randomized controlled trials, probably attributed to the relatively shorter follow-up time in RCTs and the explorative nature of the analyses as survival was not included as primary endpoint of those trials.

For haematological cancers, Knips (2019) conducted a meta-analysis of six RCTs. They found no statistically significant difference between exercise and control arms (RR 1.10; 95% CI: 0.79-1.52; P=0.59). The heterogeneity was small (I2=29%). The certainty of the evidence was low, because of the small number of patients with an event and a confidence interval that includes both clinically relevant benefits and harms.

Figure 2: Association between physical activity and overall survival (control: low physical activity, experiment: high physical activity)

Outcome 2- Hospital-related mortality

Cardiorespiratory fitness

For patients undergoing cancer surgery, Steffens (2021) demonstrated that a higher peak VO2 was significantly higher for patients without in-hospital mortality compared with in-hospital mortality (mean difference MD: 2.78; 95% CI: 1.12–4.43). Preoperative anaerobic threshold values were significantly higher for patients without in-hospital mortality compared with patients with in-hospital mortality (MD: 2.27; 95% CI: 1.03–3.51).

Physical activity

No studies investigating the association between physical activity and hospital-related mortality were selected.

Outcome 3- Adverse events (CTCAE, fatigue)

Physical fitness

No studies investigating the association between physical fitness and adverse events were selected.

Physical activity

Knips (2019) analysed the association of physical exercise activity and fatigue for patients with haematological cancers and found a statistically significant advantage for participants who exercised (SMD 0.31, 95% CI 0.13 -0.48), with a moderate heterogeneity (I2 =31%). The certainty of the evidence was moderate.

For lung cancer, Teba (2022) analysed eleven studies that assessed the association between physical activity and prevalence of severe fatigue. A small association was found (Pearson’s r=-0.23; 95% CI: -0.3, -0.17) but high heterogeneity was noted (I2=65%, Tau2=0.006).

For melanoma patients, Crosby (2021) found that, although physically active patients experienced less fatigue because of self-guided exercise, neither of the two included intervention trials produced meaningful changes in this outcome. This is possibly related to the generally low levels of fatigue presented by the included patients with melanoma at baseline.

For pancreatic cancer patients, Luo (2021) showed consistent positive associations between exercise with improvements in cancer-related fatigue: included trials used the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue (FACIT-F) scale (+9 pts) and the Fatigue Visual Analog Scale (FVAS, +1.3 pts). Luo (2021) also analysed variables associated with psychological distress (including anxiety, depression, and somatization). All trials reported an improvement in the related symptom scales across various time points.

Outcome 4- Admissions (duration, number, emergency room visits)

Cardiorespiratory fitness

No studies investigating the association between cardiorespiratory fitness and admission were selected.

Physical activity

For patients undergoing cancer surgery, Steffens (2019) showed a non-significant association between higher levels of preoperative physical activity and shorter length of stay when comparing high/moderate/low physical activity vs inactive (OR=1.15; 95% CI= 0.34-3.89) and high/moderate physical activity vs low physical activity/inactive (OR=2.01; 95% CI=0.67-6.07).

Outcome 5-Complications

Cardiorespiratory fitness

For patients undergoing cancer surgery, Steffens (2021) demonstrated that patients without postoperative complication had higher PeakVO2 before surgery (mean difference MD: 2.28; 95% CI: 1.26–3.29; I2 = 9%) compared with patients who had postoperative complications. In addition, patients without postoperative pulmonary complications (MD: 1.47; 95% CI: 0.49–2.45; I2 = 0%), minor complications (MD: 2.01; 95% CI: 0.90–3.13; I2 = 27%), or no cardiovascular complication (MD: 2.23; 95% CI: 0.30–4.15) had higher peakVO2 than patients with postoperative complications.

Physical activity

For patients undergoing cancer surgery, Steffens (2019) included four studies (n=257 participants) in a random-effects meta-analysis. Patients with higher preoperative levels of physical activity tended to be more likely to have no no postoperative complications (OR=2.60; 95% CI=0.59-11.37), although this association was not statistically significant.

Outcome 6- Quality of life

Cardiorespiratory fitness

No studies investigating the association between cardiorespiratory fitness and quality of life were selected.

Physical activity

For patients undergoing cancer surgery, Steffens (2019) found positive association between preoperative physical activity level and quality of life on the short-term (6-12 weeks postoperative, OR=1.29; 95% CI=1.11-1.49).

When comparing physical exercise versus no physical exercise for patients with haematological cancers, Knips (2019) found no evidence for a difference in quality of life (SMD=0.11, 95% CI -0.03 to 0.24; 1,259 participants) with small heterogeneity (I2=26%) and a low certainty of the evidence.

For lung cancer, Teba (2022) found moderate association (Pearson’s r =0.41; 95% CI: 0.21–0.57) between physical activity and HRQoL from 14 studies. Similar results were found when they compared studies including patients only after treatment versus those which included both patients currently under and past treatment.

For patients with melanoma, Crosby (2021) found a statistically significant association between higher levels of physical activity and higher QoL. It must be noted that participants in these studies had to meet the recommendations for a healthy lifestyle (i.e., physical activity, fruit and vegetable consumption, and non-smoking).

The findings of Luo (2021) for patients with pancreatic cancer are somewhat mixed. Most of the included studies demonstrated statistically or clinically significant improvements using various QoL scales. Some of the included trials show inconsistent findings, which can be explained by the complex determinants of QoL in patients with pancreatic cancer (i.e. factors such as disease progression, treatments and comorbidities may contribute to a worsening in QoL).

Level of evidence of the literature

We did not assess the certainty of the evidence for each outcome separately based on the individual studies by using GRADE, but instead adopted the GRADE from the systematic review authors when available or described the main limitations of the systematic reviews or the studies included in the systematic reviews to provide an indication of the overall certainty of the evidence.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the association between physical fitness and physical activity and oncological outcome measures?

| P: | Oncology patients aged 18 before, during or after curative or long-term palliative treatment |

| I: | Physical activity/fitness |

| C: | N.a. |

| O: | Overall survival (1,2,5 years), hospital-related mortality (30, 90 days), adverse events (CTCAE, fatigue), admissions (duration, number, emergency room visits), complications (Clavien-Dindo), quality of life (EORTC QLQ-C30), daily activities and participation (ADL, return to work). |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered survival, mortality and quality of life as critical outcome measures for decision making; and admission and complications as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

Search and select (Methods)

In an exploratory search of the literature the working group found the systematic review of McTiernan (2019). This umbrella review updated the evidence on the associations between physical activity and risk for cancer, and for mortality in persons with cancer. The working group agreed that this study can serve as a starting point for this literature search. Therefore, the databases Embase and Ovid/Medline were searched on 7th November 2022 based on the search strategy of McTiernan (2019) and included all references published from 2017 (after the search date of McTiernan, 2019). Relevant search terms included systematic review, physical activity and cancer. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods.

The systematic literature search yielded 824 unique hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: The study population had to meet the criteria as defined in the PICO;:

- The intervention and comparison had to be as defined in the PICO;

- One or more reported outcomes had to be as defined in the PICO;

- Research type: Systematic review

- Articles written in English or Dutch

Results

38 systematic reviews (SRs) were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full texts and thorough assessment of the studies with the AMSTAR II instrument (see the table with results of the quality assessment under the tab Methods), 22 SRs were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 16 SRs were included.

The included studies and the presented results were sub-divided based on their contribution to either the association between physical fitness and oncological outcome measures (3 SRs) or the association between physical activity and oncological outcome measures (14 SRs). While both, physical fitness and physical activity, are interrelated, most studies focus on either one or the other. Physical activity can be defined as any bodily movement via skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure, while exercise is a sub-form of physical activity that is planned, structured and repetitive and intended to improve physical fitness or health. Physical fitness is a set of attributes that people have or achieve. Important components of physical fitness include cardiorespiratory fitness and muscular fitness (e.g., muscle strength and endurance). Physical function is defined as the ability to perform basic movement or more complex daily life activities (Caspersen,1985; Painter, 1999).

Referenties

- Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, Meckes N, Bassett Jr DR, Tudor-Locke C, Greer JL, Vezina J, Whitt- Glover MC, Leon AS. 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 2011;43(8):1575-1581.

- Buffart LM, Kalter J, Sweegers MG, Courneya KS, Newton RU, Aaronson NK, Jacobsen PB, May AM, Galvão DA, Chinapaw MJ, Steindorf K, Irwin ML, Stuiver MM, Hayes S, Griffith KA, Lucia A, Mesters I, van Weert E, Knoop H, Goedendorp MM, Mutrie N, Daley AJ, McConnachie A, Bohus M, Thorsen L, Schulz KH, Short CE, James EL, Plotnikoff RC, Arbane G, Schmidt ME, Potthoff K, van Beurden M, Oldenburg HS, Sonke GS, van Harten WH, Garrod R, Schmitz KH, Winters-Stone KM, Velthuis MJ, Taaffe DR, van Mechelen W, Kersten MJ, Nollet F, Wenzel J, Wiskemann J, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Brug J. Effects and moderators of exercise on quality of life and physical function in patients with cancer: An individual patient data meta-analysis of 34 RCTs. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017 Jan;52:91-104. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.11.010. Epub 2016 Dec 5. PMID: 28006694.

- Burke S, Wurz A, Bradshaw A, Saunders S, West MA, Brunet J. Physical Activity and Quality of Life in Cancer Survivors: A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Research. Cancers (Basel). 2017 May 20;9(5):53. doi: 10.3390/cancers9050053. PMID: 28531109; PMCID: PMC5447963.

- Campbell KL, Winters-Stone KM, Wiskemann J, May AM, Schwartz AL, Courneya KS, Zucker DS, Matthews CE, Ligibel JA, Gerber LH, Morris GS, Patel AV, Hue TF, Perna FM, Schmitz KH. Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors: Consensus Statement from International Multidisciplinary Roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019 Nov;51(11):2375-2390. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002116. PMID: 31626055; PMCID: PMC8576825.

- Cariolou M, Abar L, Aune D, Balducci K, Becerra-Tomás N, Greenwood DC, Markozannes G, Nanu N, Vieira R, Giovannucci EL, Gunter MJ, Jackson AA, Kampman E, Lund V, Allen K, Brockton NT, Croker H, Katsikioti D, McGinley-Gieser D, Mitrou P, Wiseman M, Cross AJ, Riboli E, Clinton SK, McTiernan A, Norat T, Tsilidis KK, Chan DSM. Postdiagnosis recreational physical activity and breast cancer prognosis: Global Cancer Update Programme (CUP Global) systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2023 Feb 15;152(4):600-615. doi: 10.1002/ijc.34324. Epub 2022 Oct 24. PMID: 36279903; PMCID: PMC10091720.

- Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. Mar-Apr 1985;100(2):126-31.

- Choy KT, Lam K, Kong JC. Exercise and colorectal cancer survival: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2022 Aug;37(8):1751-1758. doi: 10.1007/s00384-022-04224-5. Epub 2022 Jul 27. PMID: 35882678; PMCID: PMC9388423.

- Crosby BJ, Lopez P, Galvão DA, Newton RU, Taaffe DR, Meniawy TM, Warburton L, Khattak MA, Gray ES, Singh F. Associations of Physical Activity and Exercise with Health-related Outcomes in Patients with Melanoma During and After Treatment: A Systematic Review. Integr Cancer Ther. 2021 Jan-Dec;20:15347354211040757. doi: 10.1177/15347354211040757. PMID: 34412527; PMCID: PMC8381455.

- De Backer IC, Vreugdenhil G, Nijziel MR, Kester AD, van Breda E, Schep G. Long-term follow-up after cancer rehabilitation using high-intensity resistance training: persistent improvement of physical performance and quality of life. Br J Cancer. 2008 Jul 8;99(1):30-6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604433. Epub 2008 Jun 24. PMID: 18577993; PMCID: PMC2453017.

- Dempsey PC, Friedenreich CM, Leitzmann MF, Buman MP, Lambert E, Willumsen J, Bull F. Global Public Health Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior for People Living With Chronic Conditions: A Call to Action. J Phys Act Health. 2021 Jan 1;18(1):76-85. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2020-0525. Epub 2020 Dec 4. PMID: 33276323.

- Ezzatvar Y, Ramírez-Vélez R, Sáez de Asteasu ML, Martínez-Velilla N, Zambom-Ferraresi F, Lobelo F, Izquierdo M, García-Hermoso A. Cardiorespiratory fitness and all-cause mortality in adults diagnosed with cancer systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2021 Sep;31(9):1745-1752. doi: 10.1111/sms.13980. Epub 2021 May 14. PMID: 33909308.

- Ezzatvar Y, Ramírez-Vélez R, Sáez de Asteasu ML, Martínez-Velilla N, Zambom-Ferraresi F, Izquierdo M, García-Hermoso A. Physical Function and All-Cause Mortality in Older Adults Diagnosed With Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2021 Jul 13;76(8):1447-1453. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glaa305. PMID: 33421059.

- Friedenreich CM, Stone CR, Cheung WY, Hayes SC. Physical Activity and Mortality in Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019 Oct 17;4(1):pkz080. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pkz080. PMID: 32337494; PMCID: PMC7050161.

- Gilchrist SC, Barac A, Ades PA, Alfano CM, Franklin BA, Jones LW, La Gerche A, Ligibel JA, Lopez G, Madan K, Oeffinger KC, Salamone J, Scott JM, Squires RW, Thomas RJ, Treat-Jacobson DJ, Wright JS; American Heart Association Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Secondary Prevention Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Cardio-Oncology Rehabilitation to Manage Cardiovascular Outcomes in Cancer Patients and Survivors: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019 May 21;139(21):e997-e1012. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000679. PMID: 30955352; PMCID: PMC7603804.

- Hayes S, Obermair A, Mileshkin L, Davis A, Gordon LG, Eakin E, Janda M, Beesley VL, Barnes EH, Spence RR, Sandler C, Jones T, Vagenas D, Webb P, Andrews J, Brand A, Lee YC, Friedlander M, Pumpa K, O'Neille H, Williams M; ECHO Collaborative; Stockler M; ECHO trial. Exercise during CHemotherapy for Ovarian cancer (ECHO) trial: design and implementation of a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2023 Apr 13;13(4):e067925. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-067925. PMID: 37055210; PMCID: PMC10106078.

- Jones LW, Courneya KS, Mackey JR, Muss HB, Pituskin EN, Scott JM, Hornsby WE, Coan AD, Herndon JE 2nd, Douglas PS, Haykowsky M. Cardiopulmonary function and age-related decline across the breast cancer survivorship continuum. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:25302537. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.9014.

- Jones NL, Makrides L, Hitchcock C, Chypchar T, McCartney N. Normal standards for an incremental progressive cycle ergometer test. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985 May;131(5):700-8. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.131.5.700. PMID: 3923878.

- Kenniscentrum Sport en Bewegen. Beweegrichtlijn Volwassenen en ouderen. 2017. https://www.kenniscentrumsportenbewegen.nl/producten/beweegrichtlijnen/#br-overzicht.

- Knips L, Bergenthal N, Streckmann F, Monsef I, Elter T, Skoetz N. Aerobic physical exercise for adult patients with haematological malignancies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Jan 31;1(1):CD009075. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009075.pub3. PMID: 30702150; PMCID: PMC6354325.

- Lee J. A Meta-analysis of the Association Between Physical Activity and Breast Cancer Mortality. Cancer Nurs. 2019 Jul/Aug;42(4):271-285. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000580. PMID: 29601358.

- Levett DZH, Jack S, Swart M, Carlisle J, Wilson J, Snowden C, Riley M, Danjoux G, Ward SA, Older P, Grocott MPW; Perioperative Exercise Testing and Training Society (POETTS). Perioperative cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET): consensus clinical guidelines on indications, organization, conduct, and physiological interpretation. Br J Anaesth. 2018 Mar;120(3):484-500. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2017.10.020. Epub 2017 Nov 24. PMID: 29452805.

- Luo H, Galvão DA, Newton RU, Lopez P, Tang C, Fairman CM, Spry N, Taaffe DR. Exercise Medicine in the Management of Pancreatic Cancer: A Systematic Review. Pancreas. 2021 Mar 1;50(3):280-292. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001753. PMID: 33835957; PMCID: PMC8041568.

- McTiernan A, Friedenreich CM, Katzmarzyk PT, Powell KE, Macko R, Buchner D, Pescatello LS, Bloodgood B, Tennant B, Vaux-Bjerke A, George SM, Troiano RP, Piercy KL; 2018 PHYSICAL ACTIVITY GUIDELINES ADVISORY COMMITTEE*. Physical Activity in Cancer Prevention and Survival: A Systematic Review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019 Jun;51(6):1252-1261. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001937. PMID: 31095082; PMCID: PMC6527123.

- Miller AM, Lopez-Mitnik G, Somarriba G, Lipsitz SR, Hinkle AS, Constine LS, Lipshultz SE, Miller TL. Exercise capacity in long-term survivors of pediatric cancer: an analysis from the Cardiac Risk Factors in Childhood Cancer Survivors Study . Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:663668. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24410.

- Moran J, Wilson F, Guinan E, McCormick P, Hussey J, Moriarty J. Role of cardiopulmonary exercise testing as a risk-assessment method in patients undergoing intra-abdominal surgery: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2016 Feb;116(2):177-91. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev454. PMID: 26787788.

- Mylius CF, Krijnen WP, Takken T, Lips DJ, Eker H, van der Schans CP, Klaase JM. Objectively measured preoperative physical activity is associated with time to functional recovery after hepato- pancreato-biliary cancer surgery: a pilot study. Perioper Med (Lond). 2021 Oct 4;10(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s13741-021-00202-7. PMID: 34602089; PMCID: PMC8489102.

- Newton RU, Kenfield SA, Hart NH, Chan JM, Courneya KS, Catto J, Finn SP, Greenwood R, Hughes DC, Mucci L, Plymate SR, Praet SFE, Guinan EM, Van Blarigan EL, Casey O, Buzza M, Gledhill S, Zhang L, Galvão DA, Ryan CJ, Saad F. Intense Exercise for Survival among Men with Metastatic Castrate-Resistant Prostate Cancer (INTERVAL-GAP4): a multicentre, randomised, controlled phase III study protocol. BMJ Open. 2018 May 14;8(5):e022899. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022899. PMID: 29764892; PMCID: PMC5961562.

- Older PO, Levett DZH. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing and Surgery. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017 Jul;14(Supplement_1):S74-S83. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201610-780FR. PMID: 28511024.

- Painter P, Stewart AL, Carey S. Physical functioning: definitions, measurement, and expectations. Adv Ren Replace Ther. Apr 1999;6(2):110-23. doi:10.1016/s1073-4449(99)70028-2.

- Patel AV, Friedenreich CM, Moore SC, Hayes SC, Silver JK, Campbell KL, Winters-Stone K, Gerber LH, George SM, Fulton JE, Denlinger C, Morris GS, Hue T, Schmitz KH, Matthews CE. American College of Sports Medicine Roundtable Report on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Cancer Prevention and Control. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019 Nov;51(11):2391-2402. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002117. PMID: 31626056; PMCID: PMC6814265.

- Peel AB, Thomas SM, Dittus K, Jones LW, Lakoski SG. Cardiorespiratory fitness in breast cancer patients: a call for normative values. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000432. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000432.

- Peel AB, Barlow CE, Leonard D, DeFina LF, Jones LW, Lakoski SG. Cardiorespiratory fitness in survivors of cervical, endometrial, and ovarian cancers: the Cooper Center Longitudinal Study. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;138:394397. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.05.027.

- Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, George SM, Olson RD. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018 Nov 20;320(19):2020-2028. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14854. PMID: 30418471; PMCID: PMC9582631.

- Qiu S, Jiang C, Zhou L. Physical activity and mortality in patients with colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2020 Jan;29(1):15-26. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000511. PMID: 30964753.

- Rapp D, Scharhag J, Wagenpfeil S, Scholl J. Reference values for peak oxygen uptake: cross-sectional analysis of cycle ergometry-based cardiopulmonary exercise tests of 10?090 adult German volunteers from the Prevention First Registry. BMJ Open. 2018 Mar 5;8(3):e018697. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018697. PMID: 29506981; PMCID: PMC5855221.

- Rock CL, Thomson CA, Sullivan KR, Howe CL, Kushi LH, Caan BJ, Neuhouser ML, Bandera EV, Wang Y, Robien K, Basen-Engquist KM, Brown JC, Courneya KS, Crane TE, Garcia DO, Grant BL, Hamilton KK, Hartman SJ, Kenfield SA, Martinez ME, Meyerhardt JA, Nekhlyudov L, Overholser L, Patel AV, Pinto BM, Platek ME, Rees-Punia E, Spees CK, Gapstur SM, McCullough ML. American Cancer Society nutrition and physical activity guideline for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022 May;72(3):230-262. doi: 10.3322/caac.21719. Epub 2022 Mar 16. PMID: 35294043.

- Rose GA, Davies RG, Appadurai IR, Williams IM, Bashir M, Berg RMG, Poole DC, Bailey DM. 'Fit for surgery': the relationship between cardiorespiratory fitness and postoperative outcomes. Exp Physiol. 2022 Aug;107(8):787-799. doi: 10.1113/EP090156. Epub 2022 Jun 5. PMID: 35579479; PMCID: PMC9545112.

- Ross R, Blair SN, Arena R, Church TS, Després JP, Franklin BA, Haskell WL, Kaminsky LA, Levine BD, Lavie CJ, Myers J, Niebauer J, Sallis R, Sawada SS, Sui X, Wisløff U; American Heart Association Physical Activity Committee of the Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology; Stroke Council. Importance of Assessing Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Clinical Practice: A Case for Fitness as a Clinical Vital Sign: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016 Dec 13;134(24):e653-e699. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000461. Epub 2016 Nov 21. PMID: 27881567.

- Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, Moher D, Tugwell P, Welch V, Kristjansson E, Henry DA. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017 Sep 21;358:j4008.

- Steffens D, Beckenkamp PR, Young J, Solomon M, da Silva TM, Hancock MJ. Is preoperative physical activity level of patients undergoing cancer surgery associated with postoperative outcomes? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2019 Apr;45(4):510-518. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.10.063. Epub 2018 Oct 21. PMID: 30910052.

- Steffens D, Ismail H, Denehy L, Beckenkamp PR, Solomon M, Koh C, Bartyn J, Pillinger N. Preoperative Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test Associated with Postoperative Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Cancer Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021 Nov;28(12):7120-7146. doi: 10.1245/s10434-021-10251-3. Epub 2021 Jun 8. PMID: 34101066; PMCID: PMC8186024.

- Takemura N, Chan SL, Smith R, Cheung DST, Lin CC. The effects of physical activity on overall survival among advanced cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2021 Mar 7;21(1):242. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-07988-1. PMID: 33678180; PMCID: PMC7938536.