Voorkeur middel weeënremming

Uitgangsvraag

Welk middel heeft de voorkeur ter weeënremming bij een zwangere met een dreigende vroeggeboorte?

Aanbeveling

Gebruik atosiban of nifedipine bij een dreigende vroeggeboorte. Nifedipine heeft echter als voordeel dat het minder belastend is door de orale toedieningsvorm en bovendien kosteneffectiever is dan het intraveneus toegediende atosiban.

Gebruik atosiban bij patiënten bekend met een hartaandoening.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

In de literatuuranalyse werd onderzocht welk middel, nifedipine of atosiban, de voorkeur heeft als weeënremmer bij een zwangere met een dreigende vroeggeboorte. Er werden vijf RCT’s gevonden (Al-Omari, 2006; Kashanian, 2005; Madkour, 2013; Salim, 2012; Van Vliet, 2016). Op basis van de de beschikbare literatuur lijkt er met betrekking tot de maternale en neonatale uitkomstmaten geen duidelijke voorkeur te zijn voor een van beide weeënremmers.

Er kunnen op basis van alleen de literatuur geen sterke aanbevelingen geformuleerd worden over welk middel de voorkeur heeft als weeënremmer bij een zwangere met een dreigende vroeggeboorte.

De werkgroepleden zien ernstige hypotensie bij nifedipine gebruik weinig optreden in de praktijk en ook niet zo ernstig dat weeënremming gestopt moet worden. Waarschijnlijk is de hypotensie die optreedt in de gevonden studies niet klinisch relevant. In de gevonden literatuur kon dit niet goed beoordeeld worden omdat niet alle studies een definitie gaven van de gevonden hypotensie. Het gebruik van nifedipine in de behandeling van vroeggeboorte lijkt daarom veilig voor de zwangere.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

De beslissing om weeënremming te starten en welke weeënremmer kunnen we niet aan de patiënt overlaten omdat het geen voorkeursgevoelige beslissing is. Het belangrijkste doel van het toedienen van weeënremmers is uitstel van de baring om maternaal toegediende corticosteroïden te laten inwerken ter bevordering van de foetale longrijpheid. Het is belangrijk dat er bij de keuze voor een middel rekening wordt gehouden met specifieke omstandigheden, zoals de gezondheidstoestand van de zwangere. Ook de toedieningsvorm van de weeënremmer is van belang voor de keuze van het middel. Het oraal toegediende nifedipine is beduidend minder belastend voor de patiënt dan de intraveneus toegediende atosiban.

Bespreek met de patiënte dat het geven van weeënremming bij een dreigende vroeggeboorte van belang is om uitstel van de baring te geven, zodat maternale toegediende corticosteroïden de foetale longrijping kunnen bevorderen. Het gebruik van corticosteroïden geeft een significant lagere neonatale mortaliteit en morbiditeit (McGoldrick 2020).

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

In het onderzoek van Nijman 2019 is de kosteneffectiviteit van nifedipine vergeleken met die van atosiban. Uit de resultaten blijkt dat zowel voor eenlingen als voor meerlingen de gemiddelde kosten significant lager waren in de nifedipine groep in vergelijking met de atosiban groep. Dat heeft er ook mee te maken dat atosiban intraveneus wordt toegediend met bijbehorende hogere kosten door o.a. inzet van personeel. In de antepartumfase kan dit verschil bij eenlingen grotendeels worden toegeschreven aan de gemiddelde kosten van de medicatie, die voor nifedipine €0,50 bedroeg, terwijl die voor atosiban €557 waren (Nijman, 2019). Te zien is dat de kosten voor atosiban in de loop der jaren zijn gedaald (aanvankelijk kostte atosiban €750), maar er is nog steeds een aanzienlijk kostenverschil in het voordeel van nifedipine.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Nifedipine en atosiban worden veelvuldig gebruikt in Nederland, maar de keuze tussen beide middelen verschilt per ziekenhuis. Uit een zorgevaluatie van 2021, uitgevoerd in opdracht van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Obstetrie & Gynaecologie (NVOG), blijkt dat hoewel de respondenten overtuigd waren van de vergelijkbare effectiviteit en lagere kosten van nifedipine, zoals aangetoond in de APOSTEL III-studie (Van Vliet, 2016), slechts 41% van hen daadwerkelijk nifedipine gebruikt. De meest genoemde redenen om atosiban te kiezen zijn de geringe maternale bijwerkingen van atosiban en het feit dat atosiban geregistreerd is als tocolyticum. Redenen om nifedipine te kiezen is de makkelijke toedienings vorm (oraal) en de geringe kosten vergeleken met atosiban. Nifedipine is niet geregistreerd als tocolyticum en wordt daarom off-label gebruikt. Zorgen over slechtere neonatale uitkomsten worden in onze literatuuranalyse echter alleen genoemd in de studie van Van Vliet (2016), en niet in andere studies in de literatuur. De perinatale sterfte en samengestelde neonatale uitkomsten zijn in de studie van van Vliet (2016) statistisch niet significant verschillend vergeleken met nifedipine. De maternale bijwerkingen waren gelijk voor nifedipine en atosiban.

De studie van de Haas (2009) onderzoekt de bijwerkingen van verschillende weeënremmers, waaronder atosiban, nifedipine, 2 andere tocolytica en combinaties daarvan. Uit dit onderzoek blijkt dat nifedipine vaker bijwerkingen veroorzaakt dan atosiban, met name hypotensie. Alle vrouwen met bijwerkingen herstelden echter volledig zonder blijvende invaliditeit of arbeidsongeschiktheid. Het gebruik van andere tocolytica of een combinatie van meerdere tocolytica leidde in het onderzoek van de Haas tot meer ernstigere bijwerkingen en wordt afgeraden. Dit sluit ook aan bij de review van Wilson (2022) dat andere tocolytica dan atosiban, in vergelijking met nifedipine, meer slechtere neonatale uitkomsten geven.

In sommige ziekenhuizen wordt bij hypertensieve aandoeningen en cardiovasculaire belasting de voorkeur gegeven aan atosiban vanwege mogelijke cardiovasculaire voordelen. In de literatuur is weinig bekend over cardiovasculaire complicaties bij nifedipine gebruik.

Nifedipine wordt ook gebruikt als behandeling van hoge bloeddruk in de zwangerschap.

Deze werkgroep vind het gebruik van nifedipine veilig en verantwoord om te gebruiken bij vrouwen met een dreigende vroeggeboorte.. Bij meerlingen is er mogelijk sprake van meer cardiovasculaire belasting voor de zwangere. De beste behandeling bij meerlingen is niet bekend. Er is vooralsnog geen reden om nifedipine bij meerlingen niet te geven. Meer onderzoek is nodig om hier een duidelijk antwoord op te geven.

Dosering

De nifedipine dosering bij dreigende vroeggeboorte kan lokaal in een protocol worden vastgelegd. De maximale dosering van nifedipine is 60 tot 120 mg per dag voor geregistreerde indicaties. De maximale dosering bij dreigende vroeggeboorte moet daarom niet boven de 120 mg per dag zijn. Opstart dosis nifedipine is 2 tot 3 x 10 mg nifedipine capsules, gevolgd door nifedipine 30 of 60 mg afhankelijk van het lokale protocol.

(https://www.farmacotherapeutischkompas.nl/bladeren/preparaatteksten/n/nifedipine#doseringen)

Voor atosiban staat een bolusinjectie van 6.75mg i.v. in 1 min omschreven, gevolgd door een oplaadinfuus van 18 mg (= 24 ml)/per uur voor gedurende 3 uur, gevolgd door een vervolginfuus van 6 mg (=8ml)/per uur over maximaal 45 uur. De totale behandelduur is dan maximaal 48u met een totale dosering van atosiban van 330.75mg.

(https://www.farmacotherapeutischkompas.nl/bladeren/preparaatteksten/a/atosiban#doseringen)

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Zowel nifedipine als atosiban lijkt veilig en effectief voor moeder en kind. Bij beide middelen zijn er maternale bijwerkingen beschreven, bijna altijd mild. Hoewel er iets meer bijwerkingen gezien worden bij het gebruik van nifedipine zijn deze tijdelijk van aard, zonder ernstige gezondheidsgevolgen. Er is daarom geen duidelijke voorkeur o.b.v. de maternale bijwerkingen voor een van de twee middelen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

In the Netherlands, two tocolytic agents are recommended as a first line tocolytic agent in the management of preterm labor: Nifedipine, a calcium-channel blocker and atosiban, an oxytocin antagonist. At this moment, there is no preference which tocolytic agent should be the first drug of choice. Both tocolytic agents differ in administration form, function and possible side-effects. We performed a literature search to see if there is a preference for one of the two tocolytic agents in the management of preterm labor.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Tocolytic effectiveness

|

Moderate GRADE |

Calcium channel blockers likely results in little to no difference in delay of delivery for 48 hours when compared with oxytocin receptor antagonists in pregnant women with threatened preterm birth between 20 and 36 weeks.

Source: Al-Omari, 2006; Kashanian, 2005; Salim, 2012; Van Vliet, 2016 |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that calcium channel blockers reduces preterm birth before 34 weeks when compared with oxytocin receptor antagonists in pregnant women with threatened preterm birth between 20 and 36 weeks.

Source: Salim, 2012 |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that calcium channel blockers reduces preterm birth before 37 weeks when compared with oxytocin receptor antagonists in pregnant women with threatened preterm birth between 20 and 36 weeks.

Source: Salim, 2012 |

Maternal outcomes

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of calcium channel blockers on maternal mortality when compared with oxytocin receptor antagonists in pregnant women with threatened preterm birth between 20 and 36 weeks.

Source: Van Vliet, 2016 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of calcium channel blockers on hypotension when compared with oxytocin receptor antagonists in pregnant women with threatened preterm birth between 20 and 36 weeks.

Source: Al-Omari, 2006; Kashanian, 2005; Madkour, 2013; Salim, 2012; Van Vliet, 2016 |

|

NO GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of calcium channel blockers on cardiac arrest when compared with oxytocin receptor antagonists in pregnant women with threatened preterm birth between 20 and 36 weeks. |

Neonatal outcomes

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of calcium channel blockers on neonatal mortality when compared with oxytocin receptor antagonists in pregnant women with threatened preterm birth between 20 and 36 weeks.

Source: Al-Omari, 2006; Salim, 2012; Van Vliet, 2016 |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that calcium channel blockers results in little to no difference in composite outcome of neonatal morbidity and mortality when compared with oxytocin receptor antagonists in pregnant women with threatened preterm birth between 20 and 36 weeks.

Source: Van Vliet, 2016 |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that calcium channel blockers results in little to no difference in gestational age at delivery when compared with oxytocin receptor antagonists in pregnant women with threatened preterm birth between 20 and 36 weeks.

Source: Salim, 2012 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Al-Omari (2006) performed a randomized controlled trial to compare the efficacy and safety of atosiban and nifedipine in preventing or delaying premature labor. Women aged between 18 and 35 years at 24 to 35 completed weeks’ gestation with preterm labor and singleton pregnancies with intact membranes were included. Exclusion criteria were multiple pregnancy, ruptured membranes, medical and other obstetrical complications, prior tocolytic therapy, and a blood sugar of more than 6.4 mmol/L. Thirty-two women received nifedipine and 31 women received atosiban. Groups were comparable at baseline. Outcomes of interest were delay of delivery for 48 hours, neonatal death, hypotension (defined as systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg), and gestational age at delivery.

Kashanian (2005) performed a randomized controlled trial to compare atosiban and nifedipine for treatment of preterm labor and their maternal safety. Pregnant women with a preterm labor between 26 and 34 weeks (which had been documented by a definite last menstrual period and sonography in the first trimester) with contractions occurring at a frequency of four in 20 min or eight in 60 minutes, and a cervical dilatation of 1 cm or greater and cervical effacement of 50% or more were included. Twin pregnancies were also included. Exclusion criteria were women with PROM, vaginal bleeding, fetal death or fetal distress, IUGR, a history of trauma, a cervical dilatation greater than 3 cm, systemic disorders of the mother, a known uterine anomaly (by history or sonography), and a blood pressure of less than 90/50 mmHg. Forty women received nifedipine and 40 women received atosiban. Groups were comparable at baseline. Outcomes of interest were delay of delivery for 48 hours and hypotension (not defined).

Madkour (2013) performed a prospective case-control study to determine the efficacy of using a combined therapy of atosiban, and nifedipine in preterm labor versus using each drug separately. Pregnant women between 20 and 35 years old diagnosed with preterm labor with a singleton pregnancy and a gestational age between 26 and 34 weeks were included. Other inclusion criteria were: prophylactic antibiotics against GBS, administered when the diagnosis of preterm labor was made, and continued until delivery or for a minimum of 72 hours; idiopathic preterm labor diagnosed after exclusion of the organic reasons such as uterine over distension, incompetent cervix, or accidental hemorrhage. Women with rupture of membranes, fetal distress necessitating immediate delivery, known allergy to any of the treatment modalities, and intra-amniotic infection were excluded. Fifty women received nifedipine and 50 women received atosiban. It was unclear if groups were comparable at baseline. The outcome of interest was hypotension (not defined).

Salim (2012) performed a randomized controlled trial to compare efficacy and tolerability of nifedipine with that of atosiban among pregnant women with preterm labor. Pregnant women with preterm labor and intact membranes diagnosed between 24 weeks 0 days

and 33 weeks 6 days of gestation were included. Exclusion criteria were rupture of membranes, vaginal bleeding resulting from placenta previa or placental abruption, fever above 38°C, severe preeclampsia, maternal cardiovascular or liver diseases, systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg, known uterine malformation, intrauterine growth restriction below the fifth percentile, nonreassuring fetal status, antepartum diagnosis of major fetal malformations, multiple gestations other than twins (triplets or greater), and fetal death. Seventy-five women received nifedipine and 70 women received atosiban. Groups were comparable at baseline. Outcomes of interest were delay of delivery for 48 hours, preterm birth before 34 and 37 weeks, hypotension (defined as systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg), gestational age at delivery and neonatal mortality.

Van Vliet (2016) performed a randomized controlled trial to compare nifedipine with atosiban in women with threatened preterm birth. Pregnant women aged 18 years or older with a threatened preterm birth between 25⁰/⁷ weeks and 34⁰/⁷ weeks of gestation with singleton or multiple pregnancies were included. Exclusion criteria were a contraindication for tocolysis (severe vaginal bleeding or signs of intrauterine infection), hypertension or current use of antihypertensive drugs, history of myocardial infarction or angina pectoris, cerclage, cervical dilatation greater than 5 cm, tocolytic treatment for more than 6 h before arrival in a participating center, a previous episode of tocolytic treatment, or a fetus showing signs of fetal distress or a fetus suspected of chromosomal or structural anomalies. In total, 249 women received nifedipine and 256 women received atosiban. Groups were comparable at baseline. Outcomes of interest were delay of delivery for 48 hours, a composite of adverse perinatal outcome (consisting of perinatal in-hospital mortality, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, culture proven sepsis, intraventricular hemorrhage higher than grade 2, periventricular leukomalacia higher than grade 1, and necrotizing enterocolitis higher than Bell’s stage 1), maternal death, perinatal death, gestational age at delivery and hypotension (not defined).

Results

Tocolytic effectiveness

1. Delay of delivery for 48 hours

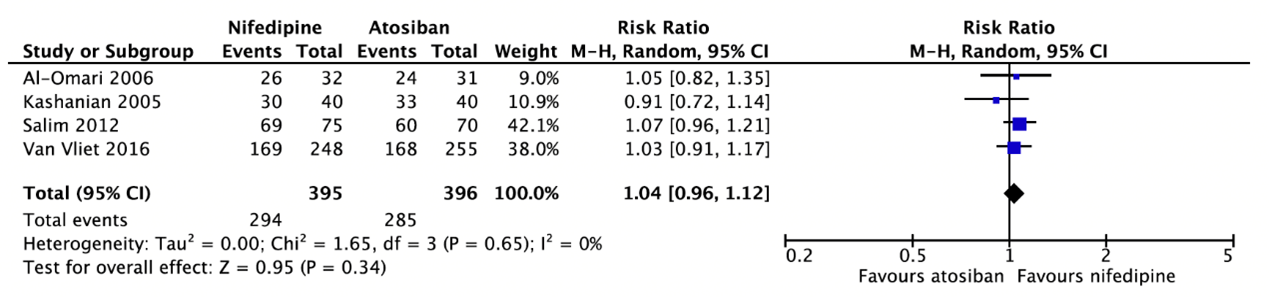

Four studies reported a delay of delivery for 48 hours (Al-Omari, 2006; Kashanian, 2005; Salim, 2012; Van Vliet, 2016) (Figure 1). In total, 294 of the 395 women (74.4%) who received nifedipine had not yet delivered at 48 hours as compared to 285 of the 396 women (72.0%) who received atosiban (RR=1.04, 95%CI 0.96 to 1.12).

Figure 1. Delay of delivery for 48 hours.

2. Preterm birth before 34 weeks

Only one study (Salim 2012) reported that 12 of the 75 women (16%) who received nifedipine had spontaneous deliveries before 34 weeks of gestation as compared to 19 of the 70 women (27%) who received atosiban (RR=0.59, 95%CI 0.31 to 1.12).

3. Preterm birth before 37 weeks

Only one study (Salim 2012) reported that 31 of the 75 women (41%) who received nifedipine had spontaneous deliveries before 37 weeks of gestation as compared to 45 of the 70 women (64%) who received atosiban (RR=0.64, 95%CI 0.47 to 0.89).

Maternal outcomes

1. Maternal mortality

Van Vliet (2016) reported that no maternal deaths occurred in women treated with either nifedipine or atosiban. In the other studies, maternal mortality was not stated.

2. Hypotension

Five studies reported hypotension (Al-Omari, 2006; Kashanian, 2005; Madkour, 2013; Salim, 2012; Van Vliet, 2016) (Figure 2). Al-Omari (2006) and Salim (2012) defined hypotension as a systolic blood pressure below 90mmHg, while the other studies did not provide a definition. In total, 37 of the 445 women (8.3%) who received nifedipine had hypotension as compared to 8 of the 446 women (1.8%) who received atosiban (RR=3.32, 95%CI 0.84 to 13.09). There were no more women in the nifedipine group who needed cessation of therapy compared with the atosiban group.

Figure 2. Hypotension.

3. Cardiovascular arrest

Not reported.

Neonatal outcomes

1. Neonatal mortality

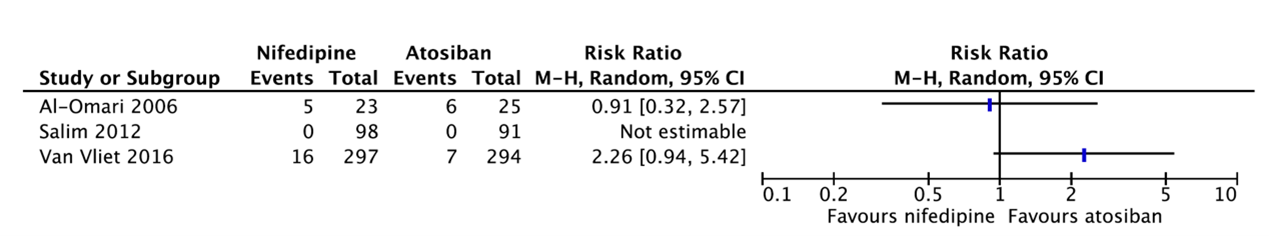

Three studies reported neonatal mortality (Figure 3).

Al-Omari (2006) reported neonatal death. Five of the 23 babies (21.7%) whose mother received nifedipine died as compared to 6 of the 25 babies (24%) whose mother received atosiban (RR=0.91, 95%CI 0.32 to 2.57).

Salim (2012) reported that no neonatal mortality occurred in women treated with either nifedipine or atosiban.

Van Vliet (2016) reported perinatal deaths. Sixteen of the 297 babies (5%) whose mother received nifedipine died as compared to 7 of the 294 babies (2%) whose mother received atosiban (RR=2.26, 95%CI 0.94 to 5.42).

Results were not pooled because of heterogeneity between studies. Figure 4 shows that there is probably no clinically relevant difference in neonatal mortality between nifedipine and atosiban.

Figure 3. Neonatal mortality.

2. Composite outcome of neonatal morbidity and mortality

Van Vliet (2016) reported the composite of adverse perinatal outcome consisting of perinatal in-hospital mortality, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, culture-proven sepsis, intraventricular hemorrhage higher than grade 2, periventricular leukomalacia higher than grade 1, and necrotizing enterocolitis higher than Bell’s stage 1. All babies with one or more of these outcomes before hospital discharge were positive for this composite outcome. The composite perinatal outcome was similar for both groups. Forty-two of the 297 babies (14%) whose mother received nifedipine were positive for this composite outcome as compared to 45 of the 294 babies (15%) whose mother received atosiban (RR=0.92, 95%CI 0.63 to 1.36).

3. Gestational age at delivery

Al-Omari (2006) reported that there was no statistically significant difference in gestational age between babies whose mother received either nifedipine or atosiban. No detailed information was presented. Therefore, no GRADE assessment could be performed.

Salim (2012) reported that the gestational age at delivery was on average 36.4 weeks (SD=2.8) for women who received nifedipine as compared to 35.2 weeks (SD=3.0) for women who received atosiban (MD=1.20, 95%CI 0.25 to 2.15). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Van Vliet (2016) reported that the median gestational age at delivery was 33.1 weeks (IQR: 30.5 to 37.0) for women who received nifedipine as compared to 32.4 weeks (IQR: 30.1 to 35.8) for women who received atosiban. This difference is not clinically relevant. No GRADE assessment could be performed.

Level of evidence of the literature

According to GRADE, the level of evidence of randomized controlled trials starts high.

Tocolytic effectiveness

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure delay of delivery for 48 hours was downgraded by one level to moderate because of concerns about randomization and blinding (-1, risk of bias).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure preterm birth before 34 weeks was downgraded by two levels to low because the 95% confidence interval crossed the line of no (clinically relevant) effect and the optimal information size was not achieved (-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure preterm birth before 37 weeks was downgraded by two levels to low because the 95% confidence interval crossed the line of no (clinically relevant) effect and the optimal information size was not achieved (-2, imprecision).

Maternal outcomes

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure maternal mortality was downgraded by three levels to very low because no events occurred and the optimal information size was not achieved (-3, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure hypotension was downgraded by three levels to very low because of concerns about randomization and blinding (-1, risk of bias), and the upper limit of the 95% confidence interval was >3 times higher than the point estimate (-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure cardiac arrest could not be assessed with GRADE as this outcome measure was not studied in the included studies.

Neonatal outcomes

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure neonatal mortality was downgraded by three levels to very low because of concerns about randomization (-1, risk of bias), conflicting results (-1, inconsistency), and the 95% confidence interval crossed the lines of no (clinically relevant) effect (-1, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure composite outcome of neonatal morbidity and mortality was downgraded by two levels to low because the 95% confidence interval crossed both lines of no (clinically relevant) effect (-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure gestational age at delivery was downgraded by two levels to low because the optimal information size was not achieved (-2, imprecision).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the (un)favorable effects of giving calcium channel blockers to pregnant women with threatened preterm birth between 20 and 36 weeks compared to oxytocin receptor antagonists on the morbidity and mortality of mother and child?

| P: | pregnant women with threatened preterm birth between 20 and 36 weeks |

| I: | calcium channel blockers (nifedipine) |

| C: | oxytocin receptor antagonists (atosiban) |

| O: |

= tocolytic effectiveness = neonatal outcome measures: composite outcome of neonatal morbidity and mortality (respiratory distress syndrome, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, retinopathy of prematurity, periventricular leukomalacia, intraventricular hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis, proven neonatal sepsis, neonatal death), gestational age at delivery, neonatal mortality |

Relevant outcome measures

The working group considered tocolytic effectiveness, maternal mortality and neonatal mortality as critical outcome measures for decision making; and hypotension, cardiovascular arrest, composite outcome of neonatal morbidity and mortality, and gestational age at delivery as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measure tocolytic effectiveness as a delay of delivery for at least 48 hours or a reduction in preterm birth before 34 or 37 weeks. For the other outcome measures, the working group did not define the outcome measures a priori, but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined a 1% difference in maternal and neonatal mortality (RR < 0.99 or > 1.01) as minimal clinically (patient) important difference. For the other outcomes, a 25% difference for dichotomous outcomes (RR < 0.8 or > 1.25) and 0.5 SD for continuous outcomes was taken as minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 2000 until the 21st of April, 2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 215 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic review (searched in at least two databases, and detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment and results of individual studies available), randomized controlled trial, or observational studies comparing calcium channel blockers with oxytocin receptor antagonists;

- The study population had to meet the criteria as defined in the PICO; and

- Full-text English language publication;

Ninety-one studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 86 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and five studies were included.

Results

Five studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Al-Omari WR, Al-Shammaa HB, Al-Tikriti EM, Ahmed KW. Atosiban and nifedipine in acute tocolysis: a comparative study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006 Sep-Oct;128(1-2):129-34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.12.010. Epub 2006 Jan 30. PMID: 16446025.

- de Heus R, Mol BW, Erwich JJ, van Geijn HP, Gyselaers WJ, Hanssens M, Härmark L, van Holsbeke CD, Duvekot JJ, Schobben FF, Wolf H, Visser GH. Adverse drug reactions to tocolytic treatment for preterm labour: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009 Mar 5;338:b744. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b744. PMID: 19264820; PMCID: PMC2654772.

- Kashanian M, Akbarian AR, Soltanzadeh M. Atosiban and nifedipin for the treatment of preterm labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005 Oct;91(1):10-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.06.005. PMID: 16043178.

- McGoldrick E, Stewart F, Parker R, Dalziel SR. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Dec 25;12(12):CD004454. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004454.pub4. PMID: 33368142; PMCID: PMC8094626.

- Madkour, WAESI and Abdelhamid, AMS. Is combination therapy of atosiban and nifedipine more effective in preterm labor than each drug alone? A prospective study. Current Women's Health Reviews. 2013; 9 (4): 209-214

- Nijman T, van Baaren GJ, van Vliet E, Kok M, Gyselaers W, Porath MM, Woiski M, de Boer MA, Bloemenkamp K, Sueters M, Franx A, Mol B, Oudijk MA. Cost effectiveness of nifedipine compared with atosiban in the treatment of threatened preterm birth (APOSTEL III trial). BJOG. 2019 Jun;126(7):875-883. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15625. Epub 2019 Mar 27. PMID: 30666783.

- Salim R, Garmi G, Nachum Z, Zafran N, Baram S, Shalev E. Nifedipine compared with atosiban for treating preterm labor: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Dec;120(6):1323-31. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e3182755dff. PMID: 23168756.

- van Vliet EOG, Nijman TAJ, Schuit E, Heida KY, Opmeer BC, Kok M, Gyselaers W, Porath MM, Woiski M, Bax CJ, Bloemenkamp KWM, Scheepers HCJ, Jacquemyn Y, Beek EV, Duvekot JJ, Franssen MTM, Papatsonis DN, Kok JH, van der Post JAM, Franx A, Mol BW, Oudijk MA. Nifedipine versus atosiban for threatened preterm birth (APOSTEL III): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016 May 21;387(10033):2117-2124. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00548-1. Epub 2016 Mar 2. PMID: 26944026.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence tables for intervention studies

Research question: What are the (un)favorable effects of giving calcium channel blockers to pregnant women with an impending preterm birth between 20 and 36 weeks compared to oxytocin receptor antagonists on the morbidity and mortality of mother and child?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Al Omari, 2006 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Baghdad Teaching Hospital, Iraq

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria: Women aged between 18 and 35 years at 24 to 35 completed weeks’ gestation with preterm labor and singleton pregnancies with intact membranes

Exclusion criteria: - Multiple pregnancy - Ruptured membranes - Medical and other obstetrical complications - Prior tocolytic therapy - Blood sugar of more than 6.4 mmol/L

N total at baseline: Intervention: 32 Control: 31

Important prognostic factors2: Age (Mean±SD) I: 27.94 ± 6.32 C: 27.45 ± 5.93

Gestational age at admission I: 30.84 ± 2.86 C: 31.19 ± 2.82

Groups comparable at baseline

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Nifedipine

Nifedipine regimen in a dosage of 10 mg orally by chewing every 15 min till uterine quiescence was achieved (0–4 contractions/ h). Maximum dose was 40 mg in the first hour then a maintenance dose of 10 mg every 4–6 h

For both groups All women at less than 34 weeks’ gestation received steroids according to the departmental policy. Antibiotics were allowed for standard clinical indications. Rest and hydration for half an hour was applied as first line management in all cases. Normal saline infusion at a rate of 100–150 ml/h after an initial bolus of 200 ml was given for hydration.

For both groups monitoring of the fetal heart, maternal pulse, blood pressure, and contractions was done every 15 min for the first 2h, hourly for the next 22 h, then twice daily thereafter when uterine quiescence had been achieved.

All women remained in hospital for 7–10 days for observation after successful tocolysis. If the assigned drug in either group failed to produce tocolysis in the first hour, or if side effects of the assigned drug were noted, an alternative tocolytic drug (rescue treatment) was initiated. The rescue drug was salbutamol for both groups. Drugs included in the study were not used as rescue treatment to avoid therapeutic crossover.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): Atosiban

Atosiban bolus (6.7 mg i.v.) over 1 min then an i.v. infusion of 18 mg/h for 3 h followed by 6 mg/h for 24–48 h |

Length of follow-up: 7-10 days

Loss-to-follow-up: 1 women who received nifedipine

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Delay of delivery for 48 hours I: 26/32 (81.3%) C: 24/31 (77.4%)

Delay of delivery for one week I: 22/32 (68.8%) C: 23/31 (74.2%)

Hypotension I: 14/32 (43.8%) C: 1/31 (3.2%)

Neonatal death I: 5/23 (21.7%) C: 6/25 (24%)

Gestational age No raw data |

Author’s conclusion: Both drugs are equally effective and efficacious in acute tocolysis. Subgrouping of patients according to gestational age and history of preterm labor may be applied in selecting the line of treatment. The maternal side effects were higher with nifedipine.

Remarks: - Small sample size - Probably no blinding |

|

Kashanian, 2005 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Akbar Abadi Teaching Hospital in Tehran, Iran

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria: - Pregnant women with a preterm labor between 26 and 34 weeks (which had been documented by a definite last menstrual period and sonography in the first trimester) - Contractions occurring at a frequency of four in 20 min or eight in 60 minutes - Cervical dilatation of 1 cm or greater

Exclusion criteria: - PROM - Known uterine anomaly (by history or sonography)

N total at baseline: Intervention: 40 Control: 40

Important prognostic factors2: Not reported, but authors stated that groups were comparable at baseline

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Nifedipine

Initial dose: 10 mg (one capsule) sublingually every 20 min for four doses.

If the contractions were inhibited: nifedipine continued orally (20 mg) every 6 h for the first 24 h, and then every 8 h for the following 24 h, and finally, 10 mg every 8 h for the last 24 h.

If the contractions continued and dilatation of the cervix progressed, or the blood pressure decreased below 90/50 mmHg: use of nifedipine was discontinued

For both groups: Corticosteroids in the form of dexamethasone was administered intramuscularly, 5 mg every 12 h for 48 h in both groups, and then all patients were monitored for the evaluation of the tocolytic’s effects. Maintenance tocolytics were not employed in either group.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): Atosiban

First, a urine analysis was done in order to measure the specific gravity because of the possible anti-diuretic effect of atosiban.

Atosiban was administered at a rate of 300 mg/min by venous infusion via microset, 48 drops.

Atosiban was continued for a maximum of 12 h, or 6 h after the patient’s contractions ceased.

If contractions continued without any changes and the dilatation of cervix improved: atosiban discontinued and it was noted as a failure of the treatment. During this period the urine output was measured, and also the fluid intake recorded. In addition, after finishing the protocol, another urine analysis for specific gravity was performed.

|

Length of follow-up: Not reported (until delivery)

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Delay of delivery for 48 hours I: 30/40 (75%) C: 33/40 (82.5%)

Delay of delivery for one week I: 26/40 (65%) C: 30/40 (75%)

Hypotension: I: 11/40 (27.5%) C: 0 (0%)

|

Author’s conclusion: Atosiban is an effective and safe drug for the acute treatment of preterm labour with minimal side effects, and it can be an option in the treatment of preterm labour, especially in patients with heart disease and multi-fetal pregnancies.

Remarks: - No blinding - No neonatal outcomes - Small sample size |

|

Madkour, 2013

|

Type of study: Prospective, case-control study

Setting and country: Obstetric department of two hospitals in United Arab Emirates

Funding and conflicts of interest: Source of funding not reported. The author(s) confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

|

Inclusion criteria: - Pregnant women between 20 and 35 years old - Diagnosed with preterm labor - Singleton pregnancy - Gestational age between 26 and 34 weeks - Prophylactic antibiotics against GBS were administered when the diagnosis of preterm labor is made and should be continued until delivery or for a minimum of 72 hours - Idiopathic preterm labor was diagnosed after exclusion of the organic reasons such as uterine over distension, incompetent cervix, or accidental hemorrhage

Exclusion criteria: - Rupture of membranes - Fetal distress necessitating immediate delivery - Known allergy to any of the treatment modalities - Intra-amniotic infection

N total at baseline: Intervention: 50 Control: 50

Important prognostic factors2: Mean age I: 28.1 C: 31.3

Mean gestational age I: 31+2 weeks C: 29+3 weeks

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Nifedipine

Nifedipine (Adalat, soft cap, 10 mg, Bayer, Berkshire, UK) in a dose of 20 mg orally, followed by 20 mg orally after 30 minutes. If contractions persist, therapy was continued with 20 mg orally every 3-8 hours for 48-72 hours with a maximum dose of 160 mg/d. After 72 hours, if maintenance was still required, long-acting Nifedipine 30-60 mg daily can be used. Maximum dose was 40 mg in the first hour then maintenance dose of 10 mg every 4-6 h for 48 hrs.

Both groups: All patients were given steroids; Betamethasone consists of two doses of 12 mg over 24 hours to enhance lung maturity.

Patients were admitted to the hospital for a minimum of 48 hours and a maximum of 5 days, to fulfill the treatment modalities, and the maintenance treatment if required.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): Atosiban

Atosiban, IV (6.75 mg initial dose, 300 microg/min loading dose for 3 hours, 100 microg/min maintenance dose for 48-96 hours) |

Length of follow-up: 7 days

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Delay of delivery for one week I: 30/50 (60%) C: 28/50 (56%)

Hypotension: I: 4/50 (8%) C: 4/50 (8%) |

Author’s conclusion: Combination of atosiban and nifedipine was shown to be more effective than using each drug separately in the treatment of preterm labor, in terms of postponing the labor for one week or more, with acceptable side effects.

Remarks: - Only maternal outcomes |

|

Salim, 2012 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Single university teaching medical center (Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Emek Medical Center, Afula, and Rappaport Faculty of Medicine, Technion, Haifa, Israel)

Funding and conflicts of interest: Supported by the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Emek Medical Center, Afula. The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Pregnant women with preterm labor and intact membranes diagnosed between 24 weeks 0 days and 33 weeks 6 days of gestation

Exclusion criteria: - Rupture of membranes - Vaginal bleeding resulting from placenta previa or placental abruption - Fever above 38°C - Severe preeclampsia - Known uterine malformation - Fetal death

N total at baseline: Intervention: 75 Control: 70

Important prognostic factors2: Age (median (range)) I: 27 (19–48) C: 28 (20–44)

Gestational age at randomization I: 31.8 (25.0-33.8) C: 31.1 (24.1-33.8)

Groups comparable at baseline

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Nifedipine

Nifedipine was given as a loading dose of 20 mg orally followed by another two doses of 20 mg, 20–30 minutes apart as needed. Maintenance was started after 6 hours with 20–40 mg four times a day for a total of 48 hours.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): Atosiban

Atosiban was given as a single loading intravenous dose, 6.75 mg in 0.9% sodium chloride solution, followed by an intravenous infusion of 300 micrograms/min in 0.9% sodium chloride solution for the first 3 hours and then 100 micrograms/min for another 45 hours.

|

Length of follow-up: Not reported (until delivery)

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Delay of delivery for 48 hours I: 69/75 (92%) C: 60/70 (85.7%)

Delay of delivery for one week I: 67/75 (89.3%) C: 55/70 (78.6%)

Preterm birth before 34 weeks I: 12/75 (16%) C: 19/70 (27%)

Preterm birth before 37 weeks I: 31/75 (41%) C: 45/70 (64%)

Hypotension: I: 8/75 (10.7%) C: 2/70 (2.9%)

Gestational age at delivery (mean±SD) I: 36.4±2.8 C: 35.2±3.0

Neonatal mortality: I: 0 C: 0

|

Author’s conclusion: Atosiban has fewer failures within 48 hours. Nifedipine may be associated with a longer postponement of delivery.

Remarks: - Underpowered to detect small differences in terms of secondary outcomes - No blinding of participants or care providers

|

|

Van Vliet, 2016 |

Type of study: Multicenter RCT

Setting and country: 19 centres (ten tertiary care centres with a neonatal intensive care unit facility and nine secondary centres) in 18 cities in the Netherlands and Belgium that collaborate in the Dutch Consortium for Healthcare Evaluation and Research in Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development. One author is a consultant for ObsEva, Switzerland; payments go to The Robinson Research Institute, Adelaide. All other authors declare no competing interests. |

Inclusion criteria: Pregnant women aged 18 years or older with a threatened preterm birth between 25⁰/⁷ weeks and 34⁰/⁷ weeks of gestation with singleton or multiple pregnancies.

Exclusion criteria: - Contraindication for tocolysis (severe vaginal bleeding or signs of intrauterine infection) - Fetus showing signs of fetal distress - Fetus suspected of chromosomal or structural anomalies

N total at baseline: Intervention: 249 Control: 256

Important prognostic factors2: Age (median (IQR)) I: 30.7 (26.2–34.0) C: 30.2 (27.2–33.0)

Gestational age at study entry (median (IQR)) I: 30.3 (28.4–32.1) C: 30.3 (28.1–31.7)

Groups comparable at baseline

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Nifedipine

Initial dose was 20 mg nifedipine (two 10 mg capsules) orally in the first hour, followed by 20 mg slow-release nifedipine per 6 h for the next 47 h.

In the first hour after the start of nifedipine administration, blood pressure and heart rate were measured every 15 min. If blood pressure remained within the normal limits, treatment continued with blood pressure and heart rate measured four times every 24 h.

Both groups: Antenatal corticosteroids were administered according to guidelines from the Dutch Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (NVOG) for management of preterm birth, which advise antenatal corticosteroids to women with threatened preterm birth at less than 34 weeks’ gestation. We gave magnesium sulphate for neuroprotection to women with threatened preterm birth at less than 32 weeks’ gestation, according to guidelines from NVOG. The provision of prophylactic antibiotics was at the discretion of the attending physician.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): Atosiban

Women received a bolus injection of 6.75 mg intravenous in 1 min, followed by 18 mg/h for 3 h, followed by a maintenance dosage of 6 mg/h for 45 h.

|

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 1 (0.4%) Reasons: not reported

Control: 1 (0.4%) Reasons: not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Two women in atosiban group had missing data.

|

Delay of delivery for 48 hours I: 169/248 (66.3%) C: 168/255 (65.9%)

Delay of delivery for one week I: 127/248 (51.2%) C: 116/255 (45.5%)

Composite of adverse perinatal outcome* I: 42/297 (14%) C: 45/294 (15%)

Gestational age at delivery I: 33.1 (30.5-37.0) C: 32.4 (30.1-35.8)

Maternal deaths I: 0 C: 0

Perinatal death I: 16/297 (5%) C: 7/294 (2%)

Hypotension I: 0/248 C: 1/255 (<1%)

*perinatal in-hospital mortality, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, culture-proven sepsis, intraventricular hemorrhage higher than grade 2, periventricular leukomalacia higher than grade 1, and necrotizing enterocolitis higher than Bell’s stage 1 |

Author’s conclusion: In women with threatened preterm birth, 48 h of tocolysis with nifedipine or atosiban results in similar perinatal outcomes.

Remarks: - No blinding of participants or care providers - Not powered to reliably assess the treatment effect on the level of individual components of the composite outcome

|

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors [(potential) confounders]

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders

Risk of bias table for intervention studies

Research question: What are the (un)favorable effects of giving calcium channel blockers to pregnant women with an impending preterm birth between 20 and 36 weeks compared to oxytocin receptor antagonists on the morbidity and mortality of mother and child?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Al-Omari, 2006 |

Probably no;

Reason: Patients were numbered consecutively so that odd and even numbers alternated.

|

No information |

No information |

Probably yes;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent.

|

Probably yes;

Reason: Protocol not available, but all important outcomes were reported. |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted. |

High (all outcomes) |

|

Kashanian, 2005 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: 4-part, ABCD, block-random allocation. |

No information |

Definitely no;

Reason: No blinding. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Protocol not available, but main outcomes were reported. |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted. |

Some concerns (hypotension) |

|

Madkour, 2013

|

No information |

Probably yes;

Reason: Author’s mentioned that patients were randomly divided by allocation concealment, but not how allocation concealment was achieved.

|

Probably no;

Reason: Participants were blinded but blinding of other personnel was not described. |

Probably yes;

Reason: No loss to follow-up was reported. |

Probably no;

Reason: Protocol not available and not all outcomes were reported in the methods section. |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted. |

High (hypotension)

|

|

Salim, 2012 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Randomization in blocks of 10 using a computer randomization sequence generation program. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Randomization results were kept in a closed study box and sequence was concealed until intervention was assigned. |

Definitely no;

Reason: Blinding of participants or care providers was not performed. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent and no missing data. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Outcomes in protocol and published report are the same. |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted. |

Some concerns (hypotension)

LOW (mortality, gestational age at delivery) |

|

Van Vliet, 2016 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Independent data manager used a web-based computerised program to randomly assign women in a 1:1 ratio, with assignment done in permuted blocks of 4 and stratified by centre.

|

No information |

Definitely no;

Reason: Clinical staff or women were not masked. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Loss to follow-up and missing data was infrequent. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Outcomes in protocol and published report are the same. |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted. |

Some concerns (hypotension)

LOW (composite outcome, gestational age at delivery, maternal death)

|

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Aboulghar M, Islam Y. Twin and preterm labor: prediction and treatment. Current Obstetrics and Gynecology Reports. 2013 Dec;2:232-9. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Abramovici A, Cantu J, Jenkins SM. Tocolytic therapy for acute preterm labor. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2012 Mar;39(1):77-87. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2011.12.003. Epub 2012 Jan 4. PMID: 22370109. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Ali AA, Sayed AK, El Sherif L, Loutfi GO, Ahmed AMM, Mohamed HB, Anwar AT, Taha AS, Yahia RM, Elgebaly A, Abdel-Daim MM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of atosiban versus nifedipine for inhibition of preterm labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019 May;145(2):139-148. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12793. Epub 2019 Mar 13. PMID: 30784056. |

Suitable individual RCTs from this systematic review were used in the literature analysis |

|

Altay M, Bayram M, Biri A, Esim Büyükbayrak E, Deren Ö, Ercan F, Eroğlu D, Çorbacıoğlu Esmer A, İnan C, Kanıt H, Karaşahin KE. Guideline on preterm labor and delivery by the society of specialists in perinatology (perinatoloji uzmanları derneği-puder), Turkey. |

Wrong study design: guideline |

|

Beattie RB, Helmer H, Khan KS, Lamont RF, McNamara H, Svare J, Tsatsaris V, van Geijn HP; Steering Group, International Preterm Labour Council. Emerging issues over the choice of nifedipine, beta-agonists and atosiban for tocolysis in spontaneous preterm labour--a proposed systematic review by the International Preterm Labour Council. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004 Apr;24(3):213-5. doi: 10.1080/01443610410001660643. PMID: 15203610. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Beinder E. Threatening premature birth. Gynakologe. 2006;39(4):299-310 |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Brown RG, MacIntyre DA. Calcium channel blockers are effective as first line for tocolysis in the management of preterm labour. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine. 2014 Dec 1;19(6):214- |

Commentary |

|

Carbonne B, Tsatsaris V, Lejeune V, Goffinet F. Which tocolytics should be used in 2001?. Journal de Gynecologie Obstetrique et Biologie de la Reproduction. 2001; 30 (1) :89-93 |

Article in French |

|

Carbonne B, Tsatsaris V. Menace d'accouchement prématuré: quels tocolytiques utiliser? [Which tocolytic drugs in case of preterm labor?]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2002 Nov;31(7 Suppl):5S96-104. French. PMID: 12454631. |

Article in French |

|

Caritis S. Adverse effects of tocolytic therapy. BJOG. 2005 Mar;112 Suppl 1:74-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00590.x. PMID: 15715600. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Cole S, Smith R, Giles W. Tocolysis: current controversies, future directions. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2004 Apr;5(4):424-9. PMID: 15134284. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Conde-Agudelo A, Romero R, Kusanovic JP. Nifedipine in the management of preterm labor: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Feb;204(2):134.e1-20. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.11.038. PMID: 21284967; PMCID: PMC3437772. |

Only one suitable study for the comparison between nifedipine and atosiban |

|

Coomarasamy A, Knox EM, Gee H, Song F, Khan KS. Effectiveness of nifedipine versus atosiban for tocolysis in preterm labour: a meta-analysis with an indirect comparison of randomised trials. BJOG. 2003 Dec;110(12):1045-9. PMID: 14664874. |

No trials comparing nifedipine directly with atosiban; more recent systematic reviews available |

|

D'ercole C, Bretelle F, Shojai R, Desbriere R, Boubli L. Tocolyse: indications et contre-indications [Tocolysis: indications and contraindications. When to start and when to stop]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2002 Nov;31(7 Suppl):5S84-95. French. PMID: 12454630. |

Article in French |

|

de Heus R, Mol BW, Erwich JJ, van Geijn HP, Gyselaers WJ, Hanssens M, Härmark L, van Holsbeke CD, Duvekot JJ, Schobben FF, Wolf H, Visser GH. Adverse drug reactions to tocolytic treatment for preterm labour: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009 Mar 5;338:b744. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b744. PMID: 19264820; PMCID: PMC2654772. |

No comparison between calcium channel blockers and oxytocin receptor antagonists |

|

de Heus R, Mulder EJ, Derks JB, Visser GH. The effects of the tocolytics atosiban and nifedipine on fetal movements, heart rate and blood flow. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009 Jun;22(6):485-90. doi: 10.1080/14767050802702349. PMID: 19479644. |

No suitable outcomes |

|

de Heus R, Mulder EJ, Visser GH. Management of preterm labor: atosiban or nifedipine? Int J Womens Health. 2010 Aug 9;2:137-42. doi: 10.2147/ijwh.s7219. PMID: 21072306; PMCID: PMC2971730. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Di Renzo GC, Al Saleh E, Mattei A, Koutras I, Clerici G. Use of tocolytics: what is the benefit of gaining 48 hours for the fetus? BJOG. 2006 Dec;113 Suppl 3:72-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01127.x. Erratum in: BJOG. 2008 Apr;115(5):674-5. PMID: 17206969. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Doret M, Kayem G. La tocolyse en cas de menace d’accouchement prématuré à membranes intactes [Tocolysis for preterm labor without premature preterm rupture of membranes]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2016 Dec;45(10):1374-1398. French. doi: 10.1016/j.jgyn.2016.09.018. Epub 2016 Oct 28. PMID: 28029463. |

Article in French |

|

Duchateau FX, Max A, Harscoat S, Curac S, Ricard-Hibon A, Mantz J. Comparison between atosiban and nicardipine in inducing hypotension during in-utero transfers for threatening premature delivery. Eur J Emerg Med. 2010 Jun;17(3):142-5. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e3283307b10. PMID: 19696681. |

Wrong study design: case-control study (better evidence available) |

|

Flenady V, Reinebrant HE, Liley HG, Tambimuttu EG, Papatsonis DN. Oxytocin receptor antagonists for inhibiting preterm labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Jun 6;(6):CD004452. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004452.pub3. PMID: 24903678. |

More recent systematic review available |

|

García N, Aguilera C. Tocolytic treatment of premature labor. Medicina Clinica. 2001; 117(13):514-516 |

Article in Spanish |

|

Giles W, Bisits A. Preterm labour. The present and future of tocolysis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2007 Oct;21(5):857-68. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2007.03.011. Epub 2007 Apr 25. PMID: 17459777. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Giles W, Bisits A. The present and future of tocolysis. Best Practice and Research in Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2007;21(5):857-868 |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Groom, KM. Pharmacological prevention of prematurity. Best Practice and Research in Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2007; 21 (5) :843-856 |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Haas DM, Benjamin T, Sawyer R, Quinney SK. Short-term tocolytics for preterm delivery - current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2014 Mar 27;6:343-9. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S44048. PMID: 24707187; PMCID: PMC3971910. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Haas DM, Caldwell DM, Kirkpatrick P, McIntosh JJ, Welton NJ. Tocolytic therapy for preterm delivery: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012 Oct 9;345:e6226. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6226. PMID: 23048010; PMCID: PMC4688428. |

More recent systematic review available; only odds ratios available for comparison between oxytocin receptor blockers versus calcium channel blockers (no raw data) |

|

Haas DM, Kirkpatrick P, McIntosh JJ, Caldwell DM. Assessing the quality of evidence for preterm labor tocolytic trials. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012 Sep;25(9):1646-52. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.650249. Epub 2012 Jan 23. PMID: 22220680. |

No research |

|

Haram K, Mortensen JH, Morrison JC. Tocolysis for acute preterm labor: does anything work. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015 Mar;28(4):371-8. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.918095. Epub 2014 Jul 3. PMID: 24990666. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Hollier LM. Preventing preterm birth: what works, what doesn't. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005 Feb;60(2):124-31. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000153640.44509.65. PMID: 15671901. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Hösli I, Sperschneider C, Drack G, Zimmermann R, Surbek D, Irion O; Swiss Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Tocolysis for preterm labor: expert opinion. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014 Apr;289(4):903-9. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-3137-9. Epub 2014 Jan 3. PMID: 24385286. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Husslein P, Cabero Roura L, Dudenhausen JW, Helmer H, Frydman R, Rizzo N, Schneider D. Atosiban versus usual care for the management of preterm labor. J Perinat Med. 2007;35(4):305-13. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2007.078. PMID: 17614750. |

Wrong comparison: not only nifedipine but combination of interventions |

|

Iniesta Doñate MD, Vilar Checa E. Tocolysis treatment of preterm labor: A review of the evidence. Ciencia Ginecologika. 2004; 8 (4) :201-217 |

Article in Spanish |

|

Ingemarsson I, Lamont RF. An update on the controversies of tocolytic therapy for the prevention of preterm birth. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003 Jan;82(1):1-9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2003.820101.x. PMID: 12580832. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Jacquemyn Y. Use of tocolytics: what is the benefit of gaining even more time? BJOG. 2006 Dec;113 Suppl 3:78-80. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01128.x. Erratum in: BJOG. 2008 Apr;115(5):674-5. PMID: 17206970. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Jørgensen JS, Weile LK, Lamont RF. Preterm labor: current tocolytic options for the treatment of preterm labor. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014 Apr;15(5):585-8. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2014.880110. Epub 2014 Jan 24. PMID: 24456411. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Kam KY, Lamont RF. Developments in the pharmacotherapeutic management of spontaneous preterm labor. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008 May;9(7):1153-68. doi: 10.1517/14656566.9.7.1153. PMID: 18422473. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

King JF. Tocolysis and preterm labour. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Dec;16(6):459-63. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200412000-00004. PMID: 15534440. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

King JF, Flenady V, Papatsonis D, Dekker G, Carbonne B, Coomarasamy A. Calcium channel blockers are more effective than other tocolytics in delaying birth and preventing respiratory distress syndrome-meta-analysis. Evidence-based Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004; 6(2), 66-67. |

No comparison with oxytocin receptor antagonist |

|

Kos M. Medicamentous inhibition of uterine contractions. Gynaecologia et Perinatologia. 2001; 10:24-30 |

Article in Serbian |

|

Kuć P, Laudański P, Pierzyński P, Laudański T. The effect of combined tocolysis on in vitro uterine contractility in preterm labour. Adv Med Sci. 2011;56(1):88-94. doi: 10.2478/v10039-011-0019-x. PMID: 21555303. |

Wrong intervention: dual combinations of atosiban, nifedipine and celecoxib |

|

Lamont RF, Jørgensen JS. Safety and Efficacy of Tocolytics for the Treatment of Spontaneous Preterm Labour. Curr Pharm Des. 2019;25(5):577-592. doi: 10.2174/1381612825666190329124214. PMID: 30931850. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Lamont CD, Jørgensen JS, Lamont RF. The safety of tocolytics used for the inhibition of preterm labour. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016 Sep;15(9):1163-73. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2016.1187128. Epub 2016 Jun 3. PMID: 27159501. |

No raw data presented for comparison nifedipine versus atosiban |

|

Lyndrup J, Lamont RF. The choice of a tocolytic for the treatment of preterm labor: a critical evaluation of nifedipine versus atosiban. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2007 Jun;16(6):843-53. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.6.843. PMID: 17501696. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Madima NR. Obstetrics drugs. South African Family Practice. 2013 May 1;55(3):S8-12. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Miyazaki C, Moreno Garcia R, Ota E, Swa T, Oladapo OT, Mori R. Tocolysis for inhibiting preterm birth in extremely preterm birth, multiple gestations and in growth-restricted fetuses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Health. 2016 Jan 14;13:4. doi: 10.1186/s12978-015-0115-7. Erratum in: Reprod Health. 2016 Mar 09;13:22. doi: 10.1186/s12978-016-0127-y. Moreno, Ralfh Garcia [corrected to Moreno Garcia, Ralf]. PMID: 26762152; PMCID: PMC4712490. |

Wrong comparison: tocolysis treatment to placebo or no treatment |

|

Morgan AS, Marlow N, Draper ES, Alfirević Z, Hennessy EM, Costeloe K. Impact of obstetric interventions on condition at birth in extremely preterm babies: evidence from a national cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016 Dec 13;16(1):390. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1154-y. PMID: 27964717; PMCID: PMC5154160. |

No comparison between calcium channel blockers and oxytocin receptor antagonists |

|

Murray SR, Stock SJ, Norman JE. Long-term childhood outcomes after interventions for prevention and management of preterm birth. Semin Perinatol. 2017 Dec;41(8):519-527. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2017.08.011. PMID: 29191292. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Nardin JM, Carroli G, Alfirevic Z. Combination of tocolytic agents for inhibiting preterm labour (Protocol). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006(4):88. |

Protocol |

|

Nassar AH, Aoun J, Usta IM. Calcium channel blockers for the management of preterm birth: a review. Am J Perinatol. 2011 Jan;28(1):57-66. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1262512. Epub 2010 Jul 16. PMID: 20640972. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Nijman TAJ, Goedhart MM, Naaktgeboren CN, de Haan TR, Vijlbrief DC, Mol BW, Benders MJN, Franx A, Oudijk MA. Effect of nifedipine and atosiban on perinatal brain injury: secondary analysis of the APOSTEL-III trial. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jun;51(6):806-812. doi: 10.1002/uog.17512. PMID: 28452086. |

Subgroup of Van Vliet 2016 |

|

Oei SG. Calcium channel blockers for tocolysis: a review of their role and safety following reports of serious adverse events. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006 Jun 1;126(2):137-45. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.03.001. Epub 2006 Mar 29. PMID: 16567033. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Papatsonis D, Flenady V, Cole S, Liley H. Oxytocin receptor antagonists for inhibiting preterm labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005(3). |

Updated version available (Flenady, 2014) |

|

Pinto Cardoso G, Houivet E, Marchand-Martin L, Kayem G, Sentilhes L, Ancel PY, Lorthe E, Marret S; EPIPAGE-2 Working Group. Association of Intraventricular Hemorrhage and Death With Tocolytic Exposure in Preterm Infants. JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Sep 7;1(5):e182355. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2355. PMID: 30646165; PMCID: PMC6324618. |

Wrong study design: cohort study (better evidence available) |

|

Pryde PG, Janeczek S, Mittendorf R. Risk-benefit effects of tocolytic therapy. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2004 Nov;3(6):639-54. doi: 10.1517/14740338.3.6.639. PMID: 15500422. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Rath W. Treatment of preterm birth. Tocolysis, progesterone, RDS-prophylaxis. Padiatrische Praxis. 2017;87(2):253-264 |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Rath W. Treatment of preterm birth. Tocolysis, progesterone, RDS-prophylaxis. Gynakologische Praxis. 2016; 40 (2):223-234 |

Duplicate |

|

Rath W, Bartz C. Tocolysis in preterm labour - Current status. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde. 2005;65(6):570-579 |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Rath W, Beinder E. Tocolysis in view of the Cochrane database, international and national guidelines. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde. 2004; 64(6):639-644 |

Article in German |

|

Roos C, Borowiack E, Kowalska M, Zapalska A, Mol B, Mignini L, Meads C, Walczak J, Khan K; EBM CONNECT collaboration. What do we know about tocolytic effectiveness and how do we use this information in guidelines? A comparison of evidence grading. BJOG. 2013 Dec;120(13):1588-96; discussion 1597-8. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12388. Epub 2013 Sep 10. PMID: 24020895. |

No comparison between calcium channel blockers and oxytocin receptor antagonists |

|

Saade GR, Shennan A, Beach KJ, Hadar E, Parilla BV, Snidow J, Powell M, Montague TH, Liu F, Komatsu Y, McKain L, Thornton S. Randomized Trials of Retosiban Versus Placebo or Atosiban in Spontaneous Preterm Labor. Am J Perinatol. 2021 Aug;38(S 01):e309-e317. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710034. Epub 2020 May 7. Erratum in: Am J Perinatol. 2021 Aug;38(S 01):e370. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1731633. PMID: 32380566. |

Wrong comparison: retosiban versus atosiban or placebo |

|

Saleh SS, Al-Ramahi MQ, Al Kazaleh FA. Atosiban and nifedipine in the suppression of pre-term labour: a comparative study. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013 Jan;33(1):43-5. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2012.721822. PMID: 23259877. |

Wrong study design: retrospective study (better evidence available) |

|

Sanu O, Lamont RF. Critical appraisal and clinical utility of atosiban in the management of preterm labor. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2010 Apr 26;6:191-9. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s9378. PMID: 20463780; PMCID: PMC2861440. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Sentilhes L, Sénat MV, Ancel PY, Azria E, Benoist G, Blanc J, Brabant G, Bretelle F, Brun S, Doret M, Ducroux-Schouwey C, Evrard A, Kayem G, Maisonneuve E, Marcellin L, Marret S, Mottet N, Paysant S, Riethmuller D, Rozenberg P, Schmitz T, Torchin H, Langer B. Prevention of spontaneous preterm birth: Guidelines for clinical practice from the French College of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians (CNGOF). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017 Mar;210:217-224. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.12.035. Epub 2016 Dec 30. PMID: 28068594. |

Wrong study design: guideline |

|

Smith V, Devane D, Begley CM, Clarke M, Higgins S. A systematic review and quality assessment of systematic reviews of randomised trials of interventions for preventing and treating preterm birth. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009 Jan;142(1):3-11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.09.008. Epub 2008 Nov 8. PMID: 18996637. |

No comparison between calcium channel blockers and oxytocin receptor antagonists; no raw data available |

|

Stelzl P, Kehl S, Oppelt P, Maul H, Enengl S, Kyvernitakis I, Rath W. Do obstetric units adhere to the evidence-based national guideline? A Germany-wide survey on the current practice of initial tocolysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2022 Mar;270:133-138. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2022.01.006. Epub 2022 Jan 10. PMID: 35051825. |

No comparison between calcium channel blockers and oxytocin receptor antagonists |

|

Stelzl P, Kehl S, Rath W. Maintenance tocolysis: a reappraisal of clinical evidence. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019 Nov;300(5):1189-1199. doi: 10.1007/s00404-019-05313-7. Epub 2019 Oct 1. PMID: 31576452. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Su LL, Samuel M, Chong YS. Progestational agents for treating threatened or established preterm labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Jan 31;2014(1):CD006770. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006770.pub3. PMID: 24482121; PMCID: PMC11031808. |

Wrong comparison: placebo |

|

Tan TC, Devendra K, Tan LK, Tan HK. Tocolytic treatment for the management of preterm labour: a systematic review. Singapore Med J. 2006 May;47(5):361-6. PMID: 16645683. |

No comparison between calcium channel blockers and oxytocin receptor antagonists |

|

Tara PN, Thornton S. Current medical therapy in the prevention and treatment of preterm labour. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2004 Dec;9(6):481-9. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2004.08.005. PMID: 15691786. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Thornton JG. Maintenance tocolysis. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2005;112:118-121 |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Thornton JG. The quality of randomised trials of tocolysis. BJOG. 2006 Dec;113 Suppl 3:93-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01131.x. Erratum in: BJOG. 2008 Apr;115(5):674-5. PMID: 17206973. |

No research |

|

Tranquilli AL, Giannubilo SR. Use and safety of calcium channel blockers in obstetrics. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16(26):3330-40. doi: 10.2174/092986709789057699. PMID: 19548865. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Tsatsaris V, Goffinet F, Carbonne B, Abitayeh G, Cabrol D. Tocolyse de première intention par nifédipine [Tocolysis by first intention with nifedipine]. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2005 Apr;33(4):263-5. French. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2005.03.015. Epub 2005 Apr 7. PMID: 15894215. |

Article in French |

|

Usta IM, Khalil A, Nassar AH. Oxytocin antagonists for the management of preterm birth: a review. Am J Perinatol. 2011 Jun;28(6):449-60. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1270111. Epub 2010 Dec 17. PMID: 21170825. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

van Vliet EO, Schuit E, Heida KY, Opmeer BC, Kok M, Gyselaers W, Porath MM, Woiski M, Bax CJ, Bloemenkamp KW, Scheepers HC, Jaquemyn Y, van Beek E, Duvekot HJ, Franssen MT, Bijvank BN, Kok JH, Franx A, Mol BW, Oudijk MA. Nifedipine versus atosiban in the treatment of threatened preterm labour (Assessment of Perinatal Outcome after Specific Tocolysis in Early Labour: APOSTEL III-Trial). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014 Mar 3;14:93. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-93. PMID: 24589124; PMCID: PMC3944539. |

Wrong study design: protocol |

|

van Winden T, Klumper J, Kleinrouweler CE, Tichelaar MA, Naaktgeboren CA, Nijman TA, van Baar AL, van Wassenaer-Leemhuis AG, Roseboom TJ, Van't Hooft J, Roos C, Mol BW, Pajkrt E, Oudijk MA. Effects of tocolysis with nifedipine or atosiban on child outcome: follow-up of the APOSTEL III trial. BJOG. 2020 Aug;127(9):1129-1137. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16186. Epub 2020 Mar 29. Erratum in: BJOG. 2021 Jan;128(1):143. PMID: 32124520; PMCID: PMC7384124. |

Follow-up study of Van Vliet 2016. No suitable outcomes. |

|

van Winden TMS, Nijman TAJ, Kleinrouweler CE, Salim R, Kashanian M, Al-Omari WR, Pajkrt E, Mol BW, Oudijk MA, Roos C. Tocolysis with nifedipine versus atosiban and perinatal outcome: an individual participant data meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022 Jul 15;22(1):567. doi: 10.1186/s12884-022-04854-1. PMID: 35840927; PMCID: PMC9284745. |

Only two studies included, better systematic review available |

|

van Winden TMS, Roos C, Nijman TAJ, Kleinrouweler CE, Olaru A, Mol BW, McAuliffe FM, Pajkrt E, Oudijk MA. Tocolysis compared with no tocolysis in women with threatened preterm birth and ruptured membranes: A propensity score analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020 Dec;255:67-73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.10.015. Epub 2020 Oct 12. PMID: 33096392. |

Wrong comparison: tocolysis versus no tocolysis |

|

Vis JY, van Baaren GJ, Wilms FF, Oudijk MA, Kwee A, Porath MM, Scheepers HC, Spaanderman ME, Bloemenkamp KW, van Lith JM, Bolte AC, Bax CJ, Cornette J, Duvekot JJ, Nij Bijvank SW, van Eyck J, Franssen MT, Sollie KM, Woiski M, Vandenbussche FP, van der Post JA, Bossuyt PM, Opmeer BC, Mol BW. Randomized comparison of nifedipine and placebo in fibronectin-negative women with symptoms of preterm labor and a short cervix (APOSTEL-I Trial). Am J Perinatol. 2015 Apr;32(5):451-60. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390346. Epub 2014 Dec 8. PMID: 25486290. |

Wrong comparison: nifedipine versus placebo |

|

Vogel JP, Nardin JM, Dowswell T, West HM, Oladapo OT. Combination of tocolytic agents for inhibiting preterm labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Jul 11;2014(7):CD006169. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006169.pub2. PMID: 25010869; PMCID: PMC10657484. |

No comparison between calcium channel blockers and oxytocin receptor antagonists |

|

Wagner P, Sonek J, Abele H, Sarah L, Hoopmann M, Brucker S, Wu Q, Kagan KO. Effectiveness of the contemporary treatment of preterm labor: a comparison with a historical cohort. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017 Jul;296(1):27-34. doi: 10.1007/s00404-017-4389-6. Epub 2017 May 8. PMID: 28484835. |

Wrong comparison: intravenous beta-mimetics versus calcium channel blocker |

|

Wilson A, Hodgetts-Morton VA, Marson EJ, Markland AD, Larkai E, Papadopoulou A, Coomarasamy A, Tobias A, Chou D, Oladapo OT, Price MJ, Morris K, Gallos ID. Tocolytics for delaying preterm birth: a network meta-analysis (0924). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Aug 10;8(8):CD014978. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD014978.pub2. PMID: 35947046; PMCID: PMC9364967. |

Suitable individual RCTs from this network meta-analysis were used in the literature analysis |

|

Wilson A, Hodgetts-Morton VA, Marson EJ, Markland AD, Larkai E, Papadopoulou A, Coomarasamy A, Tobias A, Chou D, Oladapo OT, Price MJ. Tocolytics for delaying preterm birth: a network meta‐analysis (0924). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022(8). |

Wrong study design: protocol |

|

Xiong Z, Pei S, Zhu Z. Four kinds of tocolytic therapy for preterm delivery: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2022 Jul;47(7):1036-1048. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.13641. Epub 2022 Mar 18. PMID: 35304748. |

Only odds ratio/risk ratio/SMD available for comparison between atosiban versus nifedipine; no raw data for comparison between nifedipine and atosiban |

|

Yu Y, Yang Z, Wu L, Zhu Y, Guo F. Effectiveness and safety of atosiban versus conventional treatment in the management of preterm labor. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Sep;59(5):682-685. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2020.07.010. PMID: 32917318. |

Wrong comparison: not only nifedipine but combination of interventions |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 28-08-2025

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 03-06-2025

De Koninklijke Nederlandse Organisatie van Verloskundigen (KNOV) heeft een formele verklaring van geen bezwaar gegeven.

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor zwangeren waarbij sprake is van een dreigende vroeggeboorte.

Werkgroep

- Dr. C.J. (Caroline) Bax, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, NVOG (voorzitter)

- Dr. J.B. (Jan) Derks, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, NVOG

- Dr. A. (Ayten) Elvan-Taşpınar, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, NVOG

- Dr. H.M. (Marieke) Knol, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, NVOG

- Dr. M.A. (Marjon) de Boer, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, NVOG

- Dr. D.N.M. (Dimitri) Papatsonis, gynaecoloog, NVOG

- Dr. D.E. (Lia) Wijnberger, gynaecoloog, NVOG

- Dr. P.H. (Dijk), kinderarts-neonatoloog, NVK

- Drs. L. (Leanne) Erkelens-de Vetten, kinderarts-neonataloog, NVK

- Drs. C. (Christel) Rolf, klinisch verloskundige, KNOV (tot maart 2023)

- Drs. C. (Cedric) van Uytrecht, klinisch verloskundige, KNOV (tot 15 augustus 2023)

- Drs. D. (Daphne) de Jong, eerstelijns verloskundige, KNOV (vanaf september 2023)

- Drs. M.A.M. (Machteld) van der Noll, verloskundige, KNOV

- Dr. I.F. (Igna) Kwint-Reijnders, patiëntenvertegenwoordiging Care4Neo

Klankbordgroep

- Drs. H.I. (Herma) Davelaar – van Zanten, V&VN Voortplanting, Obstetrie & Gynaecologie (tot mei 2024)

- Dhr. M. (Maikel) Hustinx, bestuurslid afdeling Vrouw & Kind V&VN (vanaf mei 2024)

Met ondersteuning van

- Drs. D.A.M. (Danique) Middelhuis, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. T. (Tessa) Geltink, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medsich Specialisten (tot april 2023)

- Dr. M.L. (Marja) Molag, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medsich Specialisten (vanaf april 2023)

Belangenverklaringen