Tweede kuur corticosteroiden bij geplande vroege sectio

Uitgangsvraag

Wat zijn de gewenste en ongewenste effecten op maternale, perinatale en lange-termijnuitkomsten van het toedienen van een tweede kuur antenatale corticosteroiden bij zwangere vrouwen die tussen 34+0 en 39+0 weken zwangerschapsduur een electieve sectio ondergaan, vergeleken met placebo of geen interventie?

Aanbeveling

Bied geen tweede kuur antenatale corticosteroiden aan aan vrouwen die tussen 34+0 en 39+0 weken zwangerschapsduur een electieve sectio ondergaan.

Overwegingen

Pros and cons of the intervention and quality of the evidence

The results of the literature analysis are inconclusive for the crucial outcomes.

Adverse effects/complications

Although the administration of maternal corticosteroids may decrease RDS and admission to neonatal special care in neonates born after planned caesarean birth from 37+0 to 39+6 weeks of gestation, it may result in harm to the neonate.

- Neonatal hypoglycaemia. Extrapolating from a study investigating the administration of corticosteroid to woman at risk of later preterm birth, it seems likely that steroids increase neonatal hypoglycaemia (RR 1.60 (1.37 to 1.87)) (Gyamfi-Bannerman, 2016). A retrospective cohort study including 99 neonates whose mother had received antenatal corticosteroids, found that the occurrence of neonatal hypoglycaemia was independent from the time interval between steroid administration and birth (di Pasquo, 2020). Neonatal hypoglycaemia has also been demonstrated in women with diabetes who have received steroids prior to caesarean birth at term (Gupta, 2020). The long-term metabolic and neurological consequences of neonatal hypoglycaemia are uncertain; a follow-up cohort (at 4.5 years) from the Children With Hypoglycemia and Their Later Development (CHYLD) Study found that neonatal hypoglycaemia was associated with a dose-dependent increased risk of poor executive function and visual motor function and may therefore impact on later learning (McKinlay, 2017).

- Educational attainment. The administration of corticosteroids may reduce educational attainment at school age (increase in the proportion of children ranked by teachers as being in lower quartile of academic ability from 9% to 18%; and reduction in proportion of children obtaining English proficiency from 13% to 7%) (Stutchfield, 2013).

- Behavioural disorders. A retrospective population-based study from Finland that included 670097 children found that exposure to maternal antenatal corticosteroid treatment, compared with nonexposure, was significantly associated with mental and behavioural disorders in children (HR [95% CI] 1.33 [1.26 to 1.41]) (Raikkonen, 2020). In a cohort of one hundred and seventy nine surviving adults 29–36 years old, who were born at extremely low birthweight (<1kg), exposure to antenatal corticosteroid was associated with clinically significant anxiety (OR 3.34 [95% CI 1.03 to 10.81) (Savoy, 2016) .

- Birthweight. A retrospective population-based study from Finland that included 278508 children found that exposure to maternal antenatal corticosteroid treatment, compared with nonexposure, was significantly associated with reduction in birth size in both preterm and term born infants (Rodriguez, 2019). An individual participant data meta-analysis of 11 trials of multiple doses of antenatal corticosteroids (4857 women and 5915 infants) found that birthweight was lower in the repeat corticosteroid group than the control group (mean difference in z score of -0.12, 95%CI -0.18 to -0.06, 5902 infants, 11 trials, p=0.80 for heterogeneity) (Crowther, 2019).

- Biological plausibility of effects. Animal studies have shown dose dependent effects on neurodevelopment, behaviour, Hypothalamic Pituitary Axis function, and birthweight, adding to the biological plausibility of effects described above (reviewed in Kemp, 2018).

Table

Summary of evidence on harms and benefits of antenatal corticosteroids from 34+0 weeks onwards to inform discussions with parents

|

|

Benefits |

Harms |

Uncertainties |

|

34+0 to 34+6 weeks

|

Highly likely to reduce - perinatal mortality (156 per 1000 to 133 per 1000 average RR 0.85 [0.77 to 0.93]), - neonatal death (119 per 1000 to 93 per 1000 births average RR 0.78 [0.70 to 0.87]) - neonatal respiratory distress (148 per 1000 to 105 per 1000 births; average RR 0.71 [0.65 to 0.78])

Likely to reduce - intraventricular haemorrhage (33 per 1000 to 19 per 1000 average RR 0.58 [0.45 to 0.75]). 1 NB Figures include women <34+0 weeks’ gestation. ------------------------------- Reductions in the above conditions are most likely to be seen if birth is 24- 48 hours after starting treatment. 2 NB Figures include women <34+0 weeks’ gestation.

A reduction in respiratory morbidity (but not mortality or interventricular haemorrhage) likely to be seen if birth is within 7 days of starting treatment. 2 NB Figures include women <34+0 weeks’ gestation. |

Likely to affect maternal glucose tolerance (with higher risk in diabetic women). 6

Likely to reduce birthweight if birth >7 days after steroids (MD -147.01 g, 95% CI -291.97 to -2.05). 2 NB Figures include women <34+0 weeks’ gestation.

No benefits are likely to be seen if birth is > 7 days after starting treatment. 2 NB Figures include women <34+0 weeks’ gestation.

Likely to increase mental and behavioural disorders in children (HR [95% CI 1.33 [1.26; 1.41]) 7

|

There is less evidence for women with multiple pregnancy. 1 NB Figures include women <34+0 weeks’ gestation.

Effects of unnecessary antenatal corticosteroids (ie if birth >7 days after steroids) are not well described.

While no long term harms have been proven, there have been no large studies. |

|

35+0 to 36+6 weeks |

Likely to reduce need for short term respiratory support (reduction from 146/1000 to 116/1000 RR 0.80 [0.66 to 0.97]). 3 NB Figures include women 34-36+5 weeks’ gestation. |

Likely to increase neonatal hypoglycaemia (150/1000 to 240/10000 RR 1.60 [1.37 to 1.87]) 3 NB Figures include women 34-36+5 weeks’ gestation. Lkely to increase mental and behavioural disorders in children (HR 1.33 [1.26 to 1.41]) 7 |

While no long term harms have been proven, there have been no large studies. |

|

Pre Planned CB at term <39 weeks |

May decrease short term respiratory distress syndrome (reduction from 54 per 1,000 to 26 per 1,000 RR 0.48 (reduction from 54 per 1,000 to 23 per 1,000 RR 0.43 [0.29 to 0.65]). 6 |

May reduce educational attainment at school age (increase in the proportion of children ranked by teachers as being in lower quartile of academic ability from 9% to 18%; and reduction in proportion of children obtaining English proficiency from 13% to 7%) 5

Likely to increase mental and behavioural disorders in children (HR 1.33) 7 |

Risk of bias in studies means quality of evidence low.

Other short term complications such as hypoglycaemia have not been studied.

|

References for Table:

1. Roberts D, Brown J, Medley N, Dalziel SR. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017

2. World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on interventions to improve preterm birth outcomes. Geneva, WHO; 2015

3. Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Thom EA, Blackwell SC, Tita ATN, et al. for the NICHD Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Antenatal Betamethasone for Women at Risk for Late Preterm Delivery. N Engl J Med 2016; 374: 1311-1320

4. Sotiriadis A, McGoldrick E, Makrydimas G, Papatheodorou S, Ioannidis JPA, Stewart F, Parker R. Antenatal corticosteroids prior to planned caesarean at term for improving neonatal outcomes (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021

5. Stutchfield P, Whitaker R, Gliddon AE, Hobson L, Kotecha S, Doull IJ. Behavioural, educational and respiratory outcomes of antenatal betamethasone for term caesarean sections (ASTECS trial). Arch Dis Child fetal Neonatal Ed. 2013; 93, 195-200

6. Jolley JA, Rajan PV, Petersen R, Fong A, Wing DA. Effect of antenatal betamethasone on blood glucose levels in women with and without diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2016;118:98–104

7. Raikkonen K, Gissler M, Kajantie E. Associations between maternal antenatal corticosteroid treatment and mental and behavioral disorders in children. JAMA 200; 323: 1924-1933.

Are there any additional pathophysiological arguments or arguments from other patient groups or other comparable interventions that might influence decision making?

- National clinical guidelines recommend that planned caesarean birth should not routinely be carried out before 39+0 weeks’ gestation (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Caesarean Section. NICE clinical guideline 132. London: NICE; 2011, updated 2019; RANZCOG. Timing of planned caesarean section at term. March 2018; Nederlandse vereniging voor Obstetrie en Gynaecologie. Indicatiestelling sectio caesarea 2011; DGGG 2020)

- Studies from other patient groups (women not specifically undergoing planned caesarean birth – a and c)

- No comparable interventions

- Possibility of harm as described above

Values and preferences of women (and their caregivers)

What would women and their families regard as important?

- Avoidance of long term harm and neurodevelopmental impairment

- Avoidance of neonatal unit admission

- Avoidance of unnecessary separation of woman and baby which interrupts the bonding process and reduces breast feeding

- The women’s preference and values should be taken in to account with shared decision-making.

- Parent-centred approach

Are there any subgroups of patients that may have different values?

- Women who have experienced a previous preterm birth

- Women who have previous given birth to a baby who required neonatal admission

- Women with a multiple pregnancy

Costs

- Little evidence of cost-effectiveness

- Costs of the corticosteroid drugs is cheap

- Costs of the outcomes (particularly neonatal special care) are expensive

- Costs of long-term harms unknown but potentially have a high societal cost

Acceptability, feasibility and implementation

- No issues regarding implementation

- Side effects of the medications

- The attitudes of pregnant women and their beliefs on the use of corticosteroids. One study using semi-structured interviews or questionnaires found that barriers to receipt of antenatal corticosteroids include: difficulty retaining information conveyed, requiring further information in a variety of formats, and time constraints faced by consumers and health professionals in the provision and understanding of information to facilitate decision making. Enablers to receipt of antenatal corticosteroids included: optimism towards steroid use, a strong knowledge of why steroids were administered, improved resilience in their pregnancy and confidence in their decision making following receipt of information about steroids (McGoldrick, 2016).

- Clinical equipoise about the value of late administration of corticosteroids

- Variability on clinicians’ practice

Differences between countries

In the UK, antenatal corticosteroids are generally prescribed to pregnant women before a planned caesarean section until 36+6 weeks of gestation. After 37+0 weeks’, clinicians discuss the potential benefits and harms with women and the administration of corticosteroids is variable.

In the Netherlands and in Belgium, antenatal corticosteroids are not recommended prior to caesearan section before 39 weeks’ gestation. Clinical policy varies between hospitals.

In Germany, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Perinatale Medizin (obstetricians-perinatologists), the German society for obstetrics and gynecology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe) and Gesellschaft für Neonatologie und Pädiatrische Intensivmedizin (neonatologists and paediatric intensive care doctors) do not recommend the administration of corticosteroids for the prevention of respiratory problems in the baby to pregnant women after 35+0 weeks of gestation. Only in selected cases this can be considered between 34+0 and 34+6 weeks.

Recommendations

There is insufficient evidence about the effect of a second course of antenatal corticosteroid therapy in women undergoing a caesarean section from 34+0 to 39+0 completed weeks of gestation on the rate of RDS, and no evidence on other maternal and neonatal outcomes.

The WHO guidance recommends a single rescue course of antenatal corticosteroids if a woman is again considered at high risk of preterm birth during the subsequent seven days (WHO; 2015).

As discussed previously, antenatal corticosteroid administration has the potential for harm. Antenatal corticosteroid administration affects fetal growth. Babies who receive antenatal corticosteroids have a lower birth weight than those that do not (Rodriguez et al., 2019). A dose response is seen, and babies that receive multiple courses of antenatal corticosteroids are most affected with reductions in weight, head circumference and length (Crowther et al., 2019).

In the absence of evidence of benefit, we therefore recommend against a second course of antenatal corticosteroid therapy in women undergoing a caesarean section from 34+0 to 39+0 completed weeks of gestation.

|

Do not offer a second course of antenatal corticosteroid therapy to women undergoing a caesarean section from 34+0 to 39+0 completed weeks of gestation. |

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Compared with vaginal birth, babies who have a planned caesarean birth are at greater risk of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) (adjusted OR 2.3, 95% CI 2.1 to 2.6), transient tachypnoea of the newborn and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (Gerten et al 2005). The administration of maternal corticosteroids prior to planned caesarean birth may reduce the risk of neonatal respiratory morbidity. There is no certainty about the added value of administering a second course of antibiotics in case the caesarean birth is delayed.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Very low GRADE |

There is insufficient evidence about the effect of a second course of antenatal corticosteroid therapy in pregnant women undergoing a caesarean section from 34+0 to 39+0 completed weeks of gestation on the rate of RDS.

Source: Al-Rawaf, 2019 |

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was identified regarding the effect of a second course of antenatal corticosteroid therapy in pregnant women undergoing a caesarean section from 34+0 to 39+0 completed weeks of gestation on perinatal mortality, neurodevelopmental disability, maternal sepsis and maternal mortality. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

One case-control study was included, which compared outcomes after two courses of corticosteroids with a single course (Al-Rawaf, 2019).

In a case-control study (although the actual study design was unclear from the published report) reported by Al-Rawaf (2019) outcomes in 96 women with an indication for planned caesarean birth who received an additional dose of corticosteroids five days before birth after two doses of corticosteroids at 32 weeks gestation were compared with 92 women who only received the usual dose of steroid (not specified whether this was one or two doses) at 32 weeks of gestation. The methodology of this study was poorly reported, and the Risk of Bias is high.

Results

The only crucial outcome reported in the included study was RDS. The OR was less than 1, indicating a protective effect, but the level of evidence was very low.

RDS

Based on the numbers reported by Al-Rawaf (2019) of neonates with RDS we calculated an OR (95% CI) of 0.25 (0.14; 0.47), p<0.0001.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure RDS started low and was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias) and number of included women and babies (imprecision).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following questions:

P: pregnant women > 34+0 completed weeks undergoing planned caesarean section;

I: antenatal corticosteroid therapy given pre-caesarean birth;

C: placebo or no intervention;

O: maternal, perinatal, and long-term child outcomes: Respiratory distress syndrome, perinatal mortality and neurodevelopmental disability, maternal sepsis and mortality, NICU and neonatal unit admission, infant chronic lung disease, need for mechanical ventilation, hypoglycemia, maternal post partum infection/pyrexia.

In the United Kingdom, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and the Royal College of Anaesthetists have proposed that the classification of urgency of caesarean birth should be categories 1 to 4, rather than elective and emergency (RCOG, 2010). For the purpose of this guideline and literature search, categories 3 and 4 are regarded as ‘planned’ procedures; category 3 is where early birth is indicated but there is no maternal or fetal compromise and category 4 is at a time to suit the woman and maternity services.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered Infant Respiratory Distress Syndrome (IRDS), perinatal mortality and neurodevelopmental disability, maternal sepsis and mortality as critical outcome measures for decision making; and NICU and neonatal unit admission, infant chronic lung disease, need for mechanical ventilation, birth weight (question 3c), hypoglycemia, maternal post-partum infection /pyrexia as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the guideline development group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined RR <0.99 or >1.01 as a minimal clinically important effect for mortality and <0.8 or >1.25 for all other outcomes.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched using relevant search terms until August 2019. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods (attached documents). The systematic literature search resulted in 467 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: original research or systematic reviews about pregnant women having a planned caesarean birth undergoing corticosteroid therapy compared to women having a planned caesarean birth not undergoing corticosteroid therapy. Forty-eight studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 47 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods (attached documents)), and one study was included.

Results

One study included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables (attached documents). The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables (attached documents).

Referenties

- Al-Rawaf, S. A., Le, A. K. J., & Alomrani, A. A. A. (2019). Effect of two separated doses of antenatal steroids at 32 weeks and five days before delivery in prevention of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. Indian Journal of Public Health Research and Development, 10(5), 625-628.

- Crowther CA, Middleton PF, Voysey M, et al. Effects of repeat prenatal corticosteroids given to women at risk of preterm birth: An individual participant data meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2019;16(4):e1002771.

- di Pasquo E, Saccone G, Angeli L, Dall’Asta A, Borghi E, et al. Determinants of neonatal hypoglycaemia after antenatal administration of corticosteroids (ACS) for lung maturation: data from two referral centers and review of the literature. Early Human Development 2020; 143: 104984.

- Gerten KA, Coonrod DV, Bay RC, Chambliss LR. Cesarean delivery and respiratory distress syndrome: does labor make a difference? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005; 193: 1061–1064.

- Gupta K, Rajagopal R, King F, Simmons D. Complications of antenatal corticosteroids in infants born by early term scheduled cesarean section. Diabetes Care 2020; 43: 906-908.

- Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Thom EA, Blackwell SC, Tita ATN, et al. for the NICHD Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Antenatal Betamethasone for Women at Risk for Late Preterm Delivery. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1311–1320.

- Kemp MW, Jobe AH, Usuda H, Nathanielsz PW, Li C, Kuo A, Huber HF, Clarke GD, Saito M, Newnham JP, Stock SJ. Efficacy and safety of antenatal steroids. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2018 Oct 1;315(4):R825-R839.

- Kirshenbaum, M., Mazaki-Tovi, S., Amikam, U., Mazkereth, R., Sivan, E., Schiff, E., & Yinon, Y. (2018). Does antenatal steroids treatment prior to elective cesarean section at 34–37 weeks of gestation reduce neonatal morbidity? Evidence from a case control study. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 297(1), 101-107.

- Le Ray, C., Boithias, C., Castaigne-Meary, V., l'Hélias, L. F., Vial, M., & Frydman, R. (2006). Caesarean before labour between 34 and 37 weeks: What are the risk factors of severe neonatal respiratory distress? European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 127(1), 56-60.

- McGoldrick EL, Crawford T, Brown JA, Groom KM, Crowther CA. Consumers attitudes and beliefs towards the receipt of antenatal corticosteroids and use of clinical practice guidelines. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2016; 16: 259

- McGoldrick E, Stewart F, Parker R, Dalziel SR. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021;12: CD004454.

- McKinlay CJD, Alsweiler JM, Anstice NS, Burakevych N et al. Association of neonatal glycemia with neurodevelopmental outcomes at 4.5 years. JAMA Pediatr 2017; 17: 972-983.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Caesarean section. NICE clinical guideline 132. London: NICE; 2011, updated 2019.

- Paul, R., Murugesh, C., Chepulis, L., Tamatea, J., & Wolmarans, L. (2019). Should antenatal corticosteroids be considered in women with gestational diabetes before planned late gestation caesarean section. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 59(3), 463-466.

- Raikkonen K, Gissler M, Kajantie E. Associations between maternal antenatal corticosteroid treatment and mental and behavioral disorders in children. JAMA 200; 323: 1924-1933

- Rodriguez A, Wang Y, Ali Khan A, Cartwright R, Gissler M, Järvelin MR. Antenatal corticosteroid therapy (ACT) and size at birth: A population-based analysis using the Finnish Medical Birth Register. PLoS Med. 2019;16(2):e1002746.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Classification of urgency of caesarean section – A continuum of risk. Good Practice No. 11. April 2010.

- Savoy C, Ferro MA, Schmidt LA, Saigal S, Van Lieshout RJ.Prenatal betamethasone exposure and psychopathology risk in extremely low birth weight survivors in the third and fourth decades of life. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016;74:278–285

- Sotiriadis A, McGoldrick E, Makrydimas G, Papatheodorou S, Ioannidis JPA, Stewart F, Parker R. Antenatal corticosteroids prior to planned caesarean at term for improving neonatal outcomes (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021.

- Stutchfield, P. R., Whitaker, R., Gliddon, A. E., Hobson, L., Kotecha, S., & Doull, I. J. (2013). Behavioural, educational and respiratory outcomes of antenatal betamethasone for term caesarean section (ASTECS trial). Archives of Disease in Childhood-Fetal and Neonatal Edition, 98(3), F195-F200.

- Vidic Z, Blickstein I, Gantar IS, verdenik I, Tul N. Timing of elective cesarean section and neonatal morbidity: a population-based study. J Mat-Fetal Neonatal Med 2016; 29: 2460-2462.

- World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on interventions to improve preterm birth outcomes. Geneva, WHO; 2015.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Al-Rawaf 2019 |

Type of study: “case-control”

Setting and country: Imamain Al-Kathimain medical city, Baghdad, Iraq

Funding: none Conflicts of interest: none declared |

Inclusion criteria: elective caesarean section Exclusion criteria: possibility of congenital infection, congenital anomalies or dysmorphic features

N total at baseline: Intervention: 96 Control: 92

Important prognostic factors2: not reported

Groups comparable at baseline? unclear

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): “two corticosteroid when she was 32 weeks of gestation and additional dose of steroid five days before delivery in addition to usual dose”

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): “only usual dose of steroid at 32 weeks of gestation”

|

Length of follow-up: not reported

Loss-to-follow-up: not reported

Incomplete outcome data: not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

RDS I 29/96 (30%) C 58/92 (63%); p<0.001 OR [95% CI] 0.25 [0.14; 0.47], p<0.0001 |

poorly reported study OR [95% CI] calculated from reported numbers |

|

Study reference

(first author, year of publication) |

Bias due to a non-representative or ill-defined sample of patients?1

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to insufficiently long, or incomplete follow-up, or differences in follow-up between treatment groups?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear)

|

Bias due to ill-defined or inadequately measured outcome ?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate adjustment for all important prognostic factors?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Al-Rawaf 2019 |

unclear |

unlikely |

unlikely |

likely |

Table of excluded studies

|

First author, year |

reason for exclusion |

|

Abbasi, 2000 |

no separate data for caesarean section |

|

Afzal, 2019 |

excluded from SR Sotiriadis 2021 |

|

Ahmed, 2015 |

included in SR Sotiriadis 2018, excluded from Sotiriadis 2021 |

|

Aiken, 2014 |

long-term results of RCT Stutchfield 2005 (included in SR Sotiriadis 2018) |

|

Altman, 2013 |

no separate data for caesarean section |

|

Amiya, 2016 |

SR, no studies included for this PICO |

|

Cartwright 2018 |

P (< 32 wks GA) different from PICO |

|

Collins 2019 |

guideline, no original data |

|

Crowther, 2015 |

SR, no separate data for caesarean section |

|

De Vivo, A. 2010 |

prednison for prevention anaphylactic reactions |

|

Dileep, 2015 |

no RCT |

|

Groom, 2019 |

narrative review |

|

Gyamfi-Bannerman, 2012 |

no separate data for caesarean section |

|

Haas, 2011 |

P (preterm birth) different from PICO |

|

Haas, 2008 |

P (preterm birth) different from PICO |

|

Kaempf, 2017 |

commentary |

|

Kamath-Rayne, 2012 |

no separate data for caesarean section |

|

Kamath-Rayne, 2016 |

narrative review |

|

Kirshenbaum, 2018 |

I different from PICO |

|

Krispin, 2018 |

no separate data for caesarean section |

|

Khushdil, 2018 |

no RCT |

|

Lassi, 2015 |

no separate data for caesarean section |

|

le Ray, 2006 |

I different from PICO |

|

Mahmoud, 2018 |

no RCT |

|

McLaughlin, 2004 |

no separate data for caesarean section |

|

McKenna 2000 |

outcome: maternal adrenal suppression |

|

Mirzamoradi 2019 |

excluded from SR Sotiriadis 2021 |

|

Nada, 2016 |

included in SR Sotiriadis 2018, excluded from Sotiriadis 2021 |

|

Nooh, 2018 |

included in SR Sotiriadis 2018, excluded from Sotiriadis 2021 |

|

Ontela, 2018 |

no separate data for caesarean section |

|

Paganelli, 2013 |

narrative review of biochemical and physiological principles |

|

Paul, 2019 |

I different from PICO |

|

Pole, 2010 |

no separate data for caesarean section |

|

Saccone, 2016 |

SR, for this PICO 3 studies included that were also included by Sotiriadis 2018 |

|

Sananès, 2017 |

excluded from SR Sotiriadis 2021 |

|

Shaughnessy, 2017 |

summary of Saccone 2016 |

|

Skoll, 2018 |

guideline, no original data |

|

Sotiriadis, 2007 |

earlier version of SR Sotiriadis 2021 |

|

Sotiriadis, 2009 |

earlier version of SR Sotiriadis 2021 |

|

Sotiriadis, 2018 |

earlier version of SR Sotiriadis 2021 |

|

Sotiriadis, 2021 |

I different from PICO |

|

Soysal, 2016 |

narrative review |

|

Srinivasjois, 2017 |

SR, 3 studies included that were also included by Sotiriadis 2018 |

|

Steer, 2005 |

editorial |

|

Stutchfield, 2005 |

included in SR Sotiriadis 2021 |

|

Stutchfield, 2013 |

included in SR Sotiriadis 2021 |

|

Ting, 2018 |

narrative review |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 30-12-2022

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 30-12-2022

The Board of the Dutch Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (NVOG) will assess whether these guidelines are still up-to-date in 2027 at the latest. If necessary, a new working group will be appointed to revise the guideline. The guideline’s validity may lapse earlier if new developments demand revision at an earlier date.

As the holder of this guideline, the NVOG is chiefly responsible for keeping the guideline up to date. Other scientific organizations participating in the guideline or users of the guideline share the responsibility to inform the chiefly responsible party about relevant developments within their fields.

Algemene gegevens

Er is meegelezen vanuit de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Kindergeneeskunde (NVK). De NVK heeft de richtlijn niet geautoriseerd, maar heeft geen bezwaar tegen publicatie.

De Koninklijke Nederlandse Organisatie van Verloskundigen (KNOV) is betrokken geweest bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijn.

De Patiëntenfederatie Nederland heeft de richtlijn goedgekeurd.

De Vlaamse Vereniging voor Obstetrie en Gynaecologie (VVOG), Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (RCOG) en Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe (DGGG) zijn betrokken geweest bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijn.

Samenstelling werkgroep

An international panel for the development of the guidelines was formed in 2019. The panel consisted of representatives from all relevant medical disciplines that are involved in medical care for pregnant women.

All panel members have been officially delegated for participation in the guideline development panel by their (scientific) societies. The panel developed the guidelines in the period from May 2019 until March 2021.

The guideline development panel is responsible for the entire text of this guideline.

Composition guideline development panel

All panel members have been officially delegated for participation in the guideline development panel by their scientific societies. The guideline development panel is responsible for the entire text of this guideline.

Guideline development panel

- J.J. Duvekot, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam, the Netherlands (chair)

- I. Dehaene, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Ghent University Hospital Belgium

- S. Galjaard, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

- A. Hamza, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Medical Center of Saarland, Homburg an der Saar, Germany

- S.V. Koenen, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, ETZ, locatie Elisabeth Ziekenhuis Tilburg, the Netherlands

- M. Kunze, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Department of Gynecology& Obstetrics University of Freiburg, Germany

- M.A. Ledingham, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, the Queen Elizabeth Hospital Glasgow, UK

- B. Magowan, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, and Co-Chair UK RCOG Guidelines Committee, NHS Borders, Scotland, UK

- G. Page, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Jan Yperman Hospital, Ypres, Belgium

- S.J. Stock, Reader and Consultant in Maternal and Fetal Medicine, University of Edinburgh Usher Institute and NHS Lothian, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK

- A.J. Thomson, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Royal Alexandra Hospital (NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde), UK

- G. Verhulst, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, ASZ Aalst/Geraardsbergen/Wetteren, Belgium

- D.C. Zondag, midwife/practice owner verloskundige praktijk De Toekomst-Geldermalsen, the Netherlands

Methodological support

- E. den Breejen, senior advisor, Knowledge Institute of the Dutch Association of Medical Specialists (until June 2019)

- J.H. van der Lee, senior advisor, Knowledge Institute of the Dutch Association of Medical Specialists (since May 2019)

- Y. Labeur, junior advisor, Knowledge Institute of the Dutch Association of Medical Specialists

Belangenverklaringen

The Code for the prevention of improper influence due to conflicts of interest was followed (https://storage.knaw.nl/2022-08/Code-for-the-prevention-of-improper-influence-due-to-conflicts-of-interest.pdf).

The working group members have provided written statements about (financially supported) relations with commercial companies, organisations or institutions related to the subject matter of the guideline during the past three years. Furthermore, inquiries have been made regarding personal financial interests, interests due to personal relationships, interests related to reputation management, interest related to externally financed research and interests related to knowledge valorisation. The chair of the guideline development panel is informed about changes in interests during the development process. The declarations of interests are reconfirmed during the commentary phase. The declarations of interests can be requested at the administrative office of the Knowledge Institute of the Dutch Association of Medical Specialists and are summarised below.

|

Last name |

Principal position |

Ancillary position(s) |

Declared interests |

Action |

|

Duvekot (chair) |

Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam |

Director Medisch Advies en Expertise Bureau Duvekot, Ridderkerk |

none |

none |

|

Dehaene |

Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Ghent University Hospital |

none |

none |

none |

|

Galjaard |

Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam |

Associated member of Diabetes in Pregnancy Group (DPSG) |

none |

none |

|

Hamza |

Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Medical Center of Saarland, Homburg |

part of the advisory board of clinical innovations, which produces Kiwi-Vacuum Extractors® and Ebb Balloon Catheter®;

|

gave ultrasound courses sponsored by ultrasound producing companies: Samsung Germany and Matramed |

Recommendations do not involve either vacuum extractor or Ebb catheter (which is used for postpartum hemorrhage); therefore no actions |

|

Koenen |

Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, ETZ, locatie Elisabeth Ziekenhuis Tilburg |

Chairman 'Koepel Kwaliteit' NVOG |

none |

none |

|

Kunze |

Divison Chief, Maternal-Fetal Medicine and Obstetrics, Departement of Gynecology & Obstetrics, University of Freiburg |

none |

none |

none |

|

Ledingham |

Consultant in Maternal and Fetal Medicine, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Glasgow |

Co-chair RCOG Guidelines committee, Guideline developer for sign (scottisch intercollegiate guidelines group) |

none |

none |

|

Magowan |

Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, and Co-Chair UK RCOG Guidelines Committee, NHS Borders, Scotland |

Co-chair RCOG Guidelines committee |

none |

none |

|

Page |

Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Jan Yperman Hospital, Ypres |

none |

none |

none |

|

Stock |

Reader and Consultant in Maternal and Fetal Medicine, University of Edinburgh and NHS Lothian, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK |

Consultant Obstetrician and Subspecialist Maternal and Fetal Medicine, member of the NIHR HTA General committee (grant funding board) and Chair of the RCOG Stillbirth Clinical Studies Group |

Research grants paid to the institution for research into pregnancy problems from National Institute of Healthcare Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA), NIHR Global Research Fund, Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council, Tommy's Baby Charity, Cheif Scientist Office Scotland. Some of this work focuses on improving risk prediction of preterm labour and researching the benefits and harms of antenatal corticosteroids. Non-financial support from HOLOGIC, non-financial support from PARSAGEN, non-financial support from MEDIX BIOCHEMICA during the conduct of an NIHR HTA study in the form of provision of reduced cost assay kits to participating sites and blinded test assay analysers |

none |

|

Thomson |

Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Royal Alexandra Hospital (NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde) |

Guideline developer for the RCOG |

none |

none |

|

Verhulst |

Head of Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, ASZ Aalst/Geraardsbergen/Wetteren |

none |

none |

none |

|

Zondag |

Midwife/practice owner verloskundige praktijk De Toekomst-Geldermalsen |

Policy adviser at the Dutch association of midwives (KNOV). Teacher at PA clinical midwives - Hogeschool Rotterdam |

none |

none |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Involvement of patient representatives from all four participating countries was challenging. Representatives of patient organisations from three countries (UK, Belgium, the Netherlands) commented on the draft guideline texts and discussed these during an online meeting. They represented the RCOG Women’s Network, the Flemish organisation for people with fertility problems ‘De verdwaalde ooievaar’, the Netherlands Patient Federation, and the Dutch association for people with fertility problems ‘Freya’. The comments were discussed and where relevant incorporated by the guideline development panel.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

Guideline implementation and practical applicability of the recommendations was taken into consideration during various stages of guideline development. Factors that may promote or hinder implementation of the guideline in daily practice were given specific attention.

The guideline is distributed digitally among all relevant professional groups. The guideline can also be downloaded from the following websites: www.nvog.nl, www.vvog.be, www.rcog.org.uk, www.dggg.de, and the Dutch guideline website: www.richtlijnendatabase.nl.

Werkwijze

AGREE

This guideline has been developed conforming to the requirements of the report of Guidelines for Medical Specialists 2.0 by the advisory committee of the Quality Counsel. This report is based on the AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II) (www.agreetrust.org)(Brouwers, 2010), a broadly accepted instrument in the international community and on the national quality standards for guidelines: “Guidelines for guidelines” (www.zorginstituutnederland.nl).

Identification of subject matter

During the initial phase of the guideline development the chairman, guideline development panel and the advisor inventoried the relevant subject matter for the guideline. Since this was a pilot project, the content of the questions and the support base in clinical practice was considered of less importance than the process of international collaboration and learning from each other. Key questions were selected in such a way that:

- they were relevant for obstetric practice in all collaborating countries;

- it was expected that the amount of literature identified for each question would be reasonable, i.e. some literature was expected, but not much;

- the recommendations were expected not to lead to extensive discussion among working group members because no major controversy was expected;

- there were no recent guidelines available for these particular topics in any of the four countries.

Clinical questions and outcomes

The guideline development panel then formulated definitive clinical questions and defined relevant outcome measures (both beneficial and harmful effects). The working group rated the outcome measures as critical, important and not important. Furthermore, where applicable, the working group defined relevant clinical differences.

Strategy for search and selection of literature

For the separate clinical questions, specific search terms were formulated and published scientific articles were searched for in (several) electronic databases. Furthermore, studies were scrutinized by cross-referencing for other included studies. The studies with potentially the highest quality of research were searched for first. The panel members selected literature in pairs (independently of each other) based on title and abstract. A second selection was performed based on full text. The databases, search terms and selection criteria are described in the modules containing the clinical questions.

Quality assessment of individual studies

Individual studies were systematically assessed, based on methodological quality criteria that were determined prior to the search, so that risk of bias could be estimated. This is described in the “risk of bias” tables.

Summary of literature

The relevant research findings of all selected articles are shown in evidence tables. The most important findings in literature are described in literature summaries. In case there were enough similarities between studies, the study data were pooled.

Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations

The strength of the conclusions of the scientific publications was determined using the GRADE-method. GRADE stands for Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (see http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/).

GRADE defines four gradations for the quality of scientific evidence: high, moderate, low or very low. These gradations provide information about the amount of certainty about the literature conclusions (http://www.guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook/).

The basic principles of the GRADE method are: formulating and prioritising clinical (patient) relevant outcome measures, a systematic review for each outcome measure, and appraisal of the evidence for each outcome measure based on the eight GRADE domains (domains for downgrading: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias; domains for upgrading: dose-effect association, large effect, and residual plausible confounding).

GRADE distinguishes four levels for the quality of the scientific evidence: high, moderate, low and very low. These levels refer to the amount of certainty about the conclusion based on the literature, in particular the amount of certainty that the conclusion based on the literature adequately supports the recommendation (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

Definition |

|

|

High |

|

|

Moderate |

|

|

Low |

|

|

Very low |

|

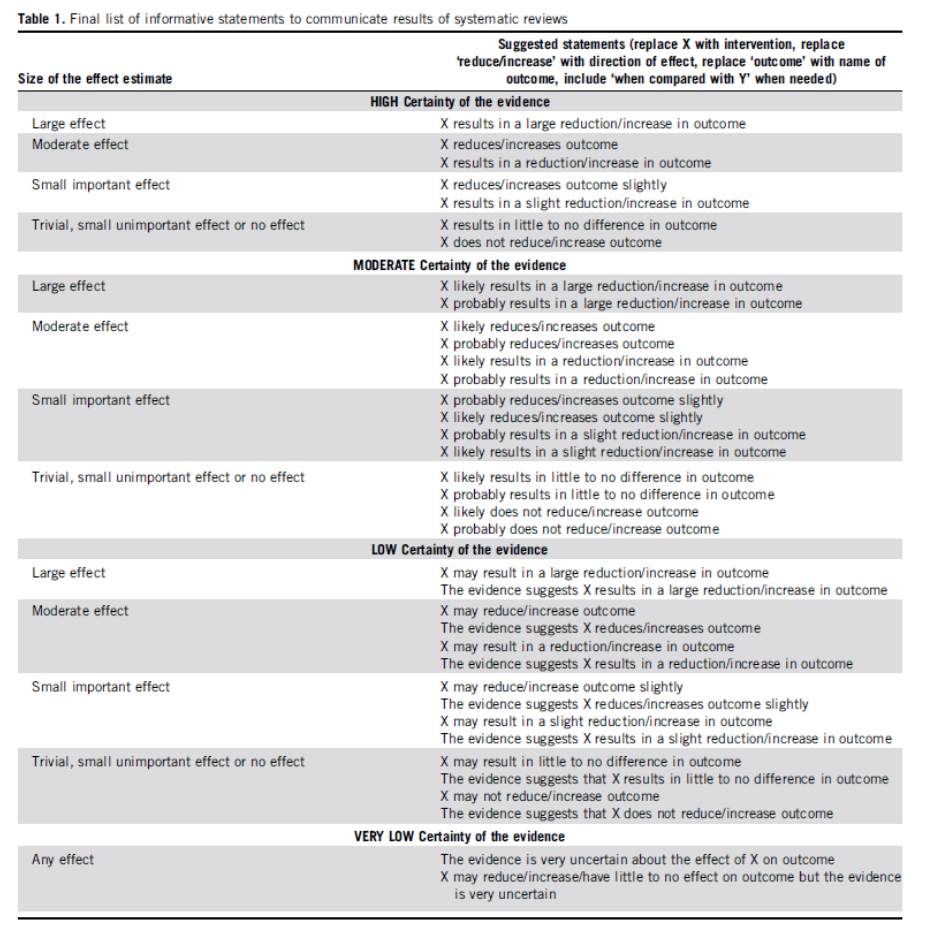

For the wording of the conclusions we used the statements suggested by the GRADE working group (Santesso, 2020), as shown below.

Source: Santesso (2020)

The limits of clinical decision making are very important in grading the evidence in guideline development according to the GRADE methodology (Hultcrantz, 2017). Exceedance of these limits would give rise to adaptation of the recommendation. All relevant outcome measures and considerations need to be taken into account to define the limits of clinical decision making. Therefore, the limits of clinical decision making are not one to one comparable to the minimal clinically relevant difference. In particular for interventions of low costs and without important drawbacks the limit of clinical decision making regarding the effectiveness of the intervention may be lower (i.e. closer to no effect) than the Minimal Clinically Important Difference (MCID) (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Considerations (evidence to decision)

Aspects such as expertise of working group members, patient preferences, costs, availability of facilities, and organisation of healthcare aspects are important to consider when formulating a recommendation. For each clinical question, these aspects are discussed in the paragraph Considerations, using a structured format based on the evidence-to-decision framework of the international GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). The evidence-to-decision framework is an integral part of the GRADE methodology.

Recommendations provide an answer to the primary question, and are based on the best scientific evidence available and the most important considerations. The level of scientific evidence and the importance given to considerations by the working group jointly determine the strength of the recommendation. In accordance with the GRADE method, a low level of evidence for conclusions in the systematic literature review does not rule out a strong recommendation, while a high level of evidence may be accompanied by weak recommendations. The strength of the recommendation is always determined by weighing all relevant arguments.

Knowledge gaps

During the development of this guideline, systematic searches were conducted for research contributing to answering the primary questions. For each primary question, the working group determined whether (additional) scientific research is desirable.

Commentary and authorisation phase

The concept guideline was subjected to commentaries by the scientific societies and patient organisations involved. The draft guideline was also submitted to the following organisations for comment: RCOG Guideline Committee and RCOG Patient Information Committee, German Neonatology and Peaediatric Intensive Care Association (Gesellschaft für Neonatologie und pädiatrische Intensivmedzin e.V.), German Midwives Society (Deutscher Hebammenverband), Flemish Midwives Society (VBOV), Belgian Federal Knowledge Centre for Health Care (KCE), Flemish College of Maternity and Neonatal Medicine (College Moeder Kind), Flemish patient organization for fertility problems (De Verdwaalde Ooievaar), Dutch Pediatric Society (NVK), Dutch College of General Practitioners (NHG), Healthcare Insurers Netherlands (ZN), The Dutch Healthcare Authority (NZA), the Health Care Inspectorate (IGJ), Netherlands Care Institute (ZIN), Dutch Organisation of Midwives (KNOV), Hospital organization (NVZ), Patient organisations Dutch Patient Federation and Freya. The comments were collected and discussed with the working group. The feedback was used to improve the guideline; afterwards the working group made the guideline definitive. The final version of the guideline was offered for authorization to the involved scientific societies and patient organisations and was authorized or approved, respectively.

Legal standing of guidelines

Guidelines are not legal prescriptions but contain evidence-based insights and recommendations that care providers should meet in order to provide high quality care. As these recommendations are primarily based on ‘general evidence for optimal care for the average patient’, care providers may deviate from the guideline based on their professional autonomy when they deem it necessary for individual cases. Deviating from the guideline may even be necessary in some situations. If care providers choose to deviate from the guideline, this should be done in consultation with the patient, where relevant. Deviation from the guideline should always be justified and documented.

Zoekverantwoording

|

Database |

Zoektermen |

Totaal |

|

Medline (OVID)

2000 – aug 2019

|

1 exp Cesarean Section/ or (caesarean or caesarian or cesarean or cesarian or caesarea).ti,ab,kw. (70817) 2 exp adrenal cortex hormones/ or exp glucocorticoids/ or exp Betamethasone/ or exp Dexamethasone/ or (cortico* or glucocortico* or betamethason* or dexamethason*).ti,ab,kw. (522943) 3 1 and 2 (1569) 4 limit 3 to (english language and yr="2000 -Current") (753) 5 (meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (meta adj analy$).tw. or ((systematic* or literature) adj2 review$1).tw. or (systematic adj overview$1).tw. or exp "Review Literature as Topic"/ or cochrane.ab. or cochrane.jw. or embase.ab. or medline.ab. or (psychlit or psyclit).ab. or (cinahl or cinhal).ab. or cancerlit.ab. or ((selection criteria or data extraction).ab. and "review"/)) not (Comment/ or Editorial/ or Letter/ or (animals/ not humans/)) (406863) 6 (exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or random*.ti,ab. or (clinic* adj trial*).tw. or ((singl* or doubl* or treb* or tripl*) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo*.tw.) not (animals/ not humans/) (1884566) 7 Epidemiologic studies/ or case control studies/ or exp cohort studies/ or Controlled Before-After Studies/ or Case control.tw. or (cohort adj (study or studies)).tw. or Cohort analy$.tw. or (Follow up adj (study or studies)).tw. or (observational adj (study or studies)).tw. or Longitudinal.tw. or Retrospective*.tw. or prospective*.tw. or consecutive*.tw. or Cross sectional.tw. or Cross-sectional studies/ or historically controlled study/ or interrupted time series analysis/ [Onder exp cohort studies vallen ook longitudinale, prospectieve en retrospectieve studies] (3237517) 8 4 and 5 (47) 9 (4 and 6) not 8 (105) 10 (4 and 7) not (8 or 9) (153) 11 8 or 9 or 10 (305)

= 305 (295 uniek)

|

467 |

|

Embase (Elsevier) |

('cesarean section'/exp OR caesarean:ti,ab OR caesarian:ti,ab OR cesarean:ti,ab OR cesarian:ti,ab OR caesarea:ti,ab)

AND ('corticosteroid'/exp/mj OR 'glucocorticoid'/exp/mj OR 'betamethasone'/exp/mj OR 'dexamethasone'/exp/mj OR cortico*:ti,ab OR glucocortico*:ti,ab OR betamethason*:ti,ab OR dexamethason*:ti,ab)

AND [english]/lim AND [2000-2019]/py NOT 'conference abstract':it

Gebruikte filters:

Systematische reviews: ('meta analysis'/de OR cochrane:ab OR embase:ab OR psycinfo:ab OR cinahl:ab OR medline:ab OR ((systematic NEAR/1 (review OR overview)):ab,ti) OR ((meta NEAR/1 analy*):ab,ti) OR metaanalys*:ab,ti OR 'data extraction':ab OR cochrane:jt OR 'systematic review'/de) NOT (('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp)

RCT’s: ('clinical trial'/exp OR 'randomization'/exp OR 'single blind procedure'/exp OR 'double blind procedure'/exp OR 'crossover procedure'/exp OR 'placebo'/exp OR 'prospective study'/exp OR rct:ab,ti OR random*:ab,ti OR 'single blind':ab,ti OR 'randomised controlled trial':ab,ti OR 'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR placebo*:ab,ti) NOT 'conference abstract':it

Observationeel onderzoek: ‘major clinical study’/exp OR 'clinical study'/de OR 'case control study'/de OR 'family study'/de OR 'longitudinal study'/de OR 'retrospective study'/de OR ('prospective study'/de NOT 'randomized controlled trial'/de) OR 'cohort analysis'/de OR ((cohort NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (case:ab,ti AND ((control NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti)) OR (follow:ab,ti AND ((up NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti)) OR ((observational NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR ((epidemiologic NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('cross sectional' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti)

= 340 (332 uniek)

|