Laat afnavelen bij premature neonaat

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de waarde van laat afnavelen bij een premature neonaat?

Aanbeveling

Wacht minimaal 60 seconden met het afklemmen van de navelstreng na de geboorte van een pasgeborene met een goede start, bij zwangerschapsduur tussen de 24 - 37 weken.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

In de literatuuranalyse werd onderzocht wat de waarde is van laat afnavelen (ten minste 60 seconden wachten met afnavelen of wachten tot volledig gestopt met pulseren) bij een premature neonaat (<37 weken zwangerschapsduur) met een goede start. Er werd één systematische review (Rabe, 2019) gevonden met acht RCT’s die voldeden aan de PICO (Dipak, 2017; Duley, 2017; Rana, 2017; Ranjit, 2015; Salae, 2016; Strauss, 2008; Tarnow-Mordi, 2017; Ultee, 2008). Daarnaast werden drie RCT’s gevonden die na de zoekdatum van Rabe 2019 zijn gepubliceerd (Armstrong-Buisseret, 2020; Robledo, 2021; Yunis, 2020). Armstrong-Buisseret (2020) en Robledo (2021) onderzochten de lange termijn effecten.

In deze module zijn de maternale uitkomsten niet meegenomen. Uit de literatuur blijkt wel dat er geen verschil lijkt te zijn tussen de hoeveelheid maternaal bloedverlies en het vroeg en laat afnavelen (McDonald, 2013). Uterotonica kunnen direct worden gegeven na de geboorte van het kind of na het afnavelen. Zie de NVOG richtlijn Haemorrhagia postpartum 2013-2015 (dit lijkt een kennis lacune).

Zwangerschapstermijn tussen de 24 - 37 weken

Elf studies rapporteerden het effect van laat afnavelen bij een premature neonaat geboren tussen 24 en 37 weken (Armstrong-Buisseret, 2020; Dipak, 2017; Duley, 2017; Rana, 2017; Ranjit, 2015; Robledo, 2021; Salea, 2016; Strauss, 2008; Tarnow-Mordi, 2017; Ultee, 2008; Yunis, 2020).

Met betrekking tot de cruciale uitkomstmaten blijkt dat laat afnavelen de perinatale sterfte vermindert en zijn er aanwijzingen dat het de neurologische uitkomsten bij 2 jaar verbetert. Door het beperkte aantal studies naar het effect van laat afnavelen op neurologische uitkomsten bij 2 jaar en door heterogeniteit tussen de studies kon de data niet gepoold worden. De bewijskracht voor deze uitkomstmaat is daarom laag.

Wat betreft belangrijke uitkomstmaten wordt in deze literatuuranalyse een klinisch relevant (doch statistisch niet significant) gunstig effect gevonden van laat afnavelen op het voorkomen van anemie bij de pasgeboren prematuur. Dit leidt volgens onze verdere analyse niet tot een vermindering van het aantal bloedtransfusies of een klinisch relevant verschil in ferritine gehalte op de termijn van 2-4 maanden postpartum.

Ten aanzien van potentieel nadelige effecten van laat afnavelen, te weten intra-ventriculaire bloedingen (door volume shifts direct na de geboorte) danwel hyperbilirubinemie (door verhoging van het hematocriet) vonden wij in deze literatuur analyse geen verschillen van laat afnavelen ten opzichte van vroeg afnavelen.

Zwangerschapstermijn tussen de 24 - 30 weken

Twee studies rapporteerden het effect van laat afnavelen bij de specifieke patiëntengroep prematuren geboren vóór 30 weken zwangerschapsduur (Tarnow-Mordi, 2017; Robledo, 2021).

Met betrekking tot de cruciale uitkomstmaten lijkt laat afnavelen te resulteren in een vermindering van perinatale sterfte vergeleken met vroeg afnavelen en zijn er aanwijzingen dat het de neurologische uitkomsten bij 2 jaar verbetert.

Wat betreft belangrijke uitkomstmaten werd in deze subgroep geen literatuur gevonden ten aanzien van het voorkomen van anemie bij prematuren < 30 weken die laat vs. vroeg werden afgenaveld. De literatuuranalyse toont geen verschil in het aantal gegeven bloedtransfusies. Het ferritine gehalte op de termijn van 2-4 maanden postpartum werd in deze subgroep niet beschreven.

Ten aanzien van potentieel nadelige effecten van laat afnavelen, te weten intra-ventriculaire bloedingen danwel hyperbilirubinemie, werd in deze subgroep <30 weken geen verschil gevonden van laat afnavelen ten opzichte van vroeg afnavelen.

Zwangerschapstermijn tussen de 30 - 37 weken

Drie studies rapporteerden het effect van laat afnavelen bij specifiek prematuren geboren na 30 weken zwangerschapsduur (Ranjit, 2015; Salae, 2016; Ultee, 2008).

Met betrekking tot cruciale uitkomstmaten lijkt laat afnavelen te resulteren in een vermindering van perinatale sterfte vergeleken met vroeg afnavelen. De bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten ‘perinatale sterfte’ was echter zeer laag vanwege methodologische beperkingen en spreiding in de richting van het effect. Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat ‘neurologische uitkomsten op 2 jaar’ werd geen bewijs gevonden. Andere studies kunnen leiden tot nieuwe inzichten.

Wat betreft belangrijke uitkomstmaten wordt in deze literatuuranalyse geen statistisch significant gunstig effect gevonden van laat afnavelen op het voorkomen van anemie bij de pasgeboren prematuur. Echter neigen de gerapporteerde getallen van 12% vs. 0% anemie (Ranjit, 2015) en 6.8% vs. 0% (Salae, 2016) in het voordeel van laat afnavelen naar een klinisch relevant verschil. De data konden niet worden gepoold door het beperkte aantal artikelen en daarmee heterogeniteit tussen de studies.

De mogelijke vermindering van voorkomen van anemie in de groep prematuren >30 weken die behandeld werden met laat afnavelen, leidt volgens onze verdere analyse niet tot een vermindering van het aantal bloedtransfusies of een klinisch relevant verschil in ferritine gehalte op de termijn van 2-4 maanden postpartum.

Ten aanzien van potentieel nadelige effecten van laat afnavelen, te weten intra-ventriculaire bloedingen danwel hyperbilirubinemie, werd in deze subgroep >30 weken geen verschil gevonden van laat afnavelen ten opzichte van vroeg afnavelen.

De pasgeborene met een slechte start:

Alle beschreven literatuur gaat over laat afnavelen bij pasgeborenen met een goede start. Wanneer een kind met een slechte start geboren wordt, ontstaat het dilemma of het kind direct afgenaveld moet worden om adequate respiratoire ondersteuning te krijgen. Tot op heden is onvoldoende wetenschappelijk bewijs dat het positieve effect van laat afnavelen opweegt tegen later starten met respiratoire ondersteuning als het kind met een slechte start geboren wordt. Daarom wordt dit nog niet als zodanig geadviseerd in internationale richtlijnen met betrekking tot neonatale reanimatie.

In sommige centra wordt om deze reden een aangepaste opvangtafel gebruikt die naast moeder of over moeder heen geplaatst kan worden (o.a. Life Start Trolley of Concord Table). Deze manier van opvangen maakt het mogelijk om de neonatale reanimatie op te starten terwijl de navelstreng van de pasgeborene nog intact is. Het gebruik van een dergelijke opvangtafel wordt over het algemeen in onderzoeksverband gedaan in academische centra; het is nog geen standaard zorg. De recent gepubliceerde Nederlandse ABC3-trial naar rescusitatie met intacte navelstreng bij prematuren toont geen verschil in overleving zonder grote intra-cerebrale bloedingen of necrotiserende enterocolitis (Knol, 2024). Een mogelijk gunstig effect in mannelijke pasgeborenen moet verder onderzocht worden. De techniek was veilig om uit te voeren en ouders rapporteerde meer tevredenheid en minder angstklachten.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Wanneer wordt gewacht met afnavelen van een premature pasgeborene, betekent dat over het algemeen dat de pasgeborene op de borst/ in de buurt van de moeder kan blijven liggen. Naar verwachting zullen ouders het op prijs stellen om op deze manier het eerste contact met hun kindje te hebben. Wetenschappelijk onderzoek toont aan dat direct huidcontact na de geboorte positieve effecten heeft op het slagen van borstvoeding, mortaliteit, thermoregulatie van de pasgeborene en daarnaast op de binding tussen ouder en kind en het geestelijk welzijn van ouders (Altit 2024).

Gezien bovendien het gunstige effect van laat afnavelen op perinatale mortaliteit en mogelijk ook op neurologische uitkomst bij 2 jaar, is onze verwachting dat ouders het belang hiervan volledig ondersteunen.

Het is belangrijk om ouders vooraf aan de partus voor te lichten over de mogelijkheid en de procedure van laat afnavelen. Door dit vooraf met ouders te bespreken, is het duidelijk naar ouders toe en kan geen verkeerde verwachting, teleurstelling of zelfs trauma ontstaan wanneer de opvang anders verloopt dan gedacht.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Van het wachten met afnavelen tot tenminste 60 seconden na de geboorte, zijn geen of nihil extra kosten te verwachten. Gezien het potentieel gunstige effect op perinatale sterfte, zouden eventuele minimale kosten de verandering in werkwijze zeker waard zijn.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Sinds 2021 wordt vanuit de Nederlandse Reanimatie Raad de aanbeveling gedaan om na de geboorte van onbedreigde premature of a-terme pasgeborene, minimaal 60 seconden te wachten met het afklemmen van de navelstreng. Het is een simpele handeling die weinig tijdverlies of kosten met zich meebrengt, maar wel potentieel gunstige gevolgen heeft voor de pasgeborene. Derhalve is het laat afnavelen in de meeste klinieken in Nederland al dagelijkse gang van zaken. Er zijn dan ook geen grote bezwaren of belemmerende factoren te verwachten om dit beleid landelijk te implementeren.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Gezien het gunstige effect op neonatale mortaliteit, de mogelijke verbetering van neurologische uitkomsten bij 2 jaar en het ontbreken van nadelige effecten (IVH en hyperbilirubinemie) is er voldoende argumentatie om minimaal 60 seconden te wachten met afnavelen na de geboorte van een pasgeborene met een goede start met een zwangerschapsduur ³ 24 en -<37 weken.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Clamping the umbilical cord can take place at different times after birth: immediately, within 60 seconds, after 60-180 seconds or after the umbilical cord completely stopped pulsating. Ideally the lungs will be inflated before the umbilical cord is clamped. At that stage, oxygen supply to the newborn is not depending on the umbilical flow anymore.

A number of guidelines (WHO, European resuscitation guideline, Dutch resuscitation guideline) already recommend delayed cord clamping (after 60 seconds) in case of a premature birth and a vital child. It has not yet been described in an NVOG guideline. It is therefore still dependent on local agreements/customs whether everyone adheres to this recommendation.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

PICO 1: premature birth between 24 and 37 weeks

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that delayed cord clamping reduces perinatal death when compared with early cord clamping in premature births between 24 and 37 weeks.

Source: Duley, 2017; Ranjit, 2015; Strauss, 2008; Tarnow-Mordi, 2017; Yunis, 2020 |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that delayed cord clamping reduces adverse neurological outcome at 2 years when compared with early cord clamping in premature births between 24 and 37 weeks.

Source: Armstrong-Buisseret, 2020; Robledo, 2021 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of delayed cord clamping on intraventricular hemorrhage when compared with early cord clamping in premature births between 24 and 37 weeks.

Source: Duley, 2017; Rana, 2017; Ranjit, 2015; Tarnow-Mordi, 2017; Yunis, 2020 |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that delayed cord clamping results in little to no difference on need for erythrocyte transfusion when compared with early cord clamping in premature births between 24 and 37 weeks.

Source: Dipak, 2017; Duley, 2017; Rana, 2017; Ranjit, 2015; Salae, 2016; Strauss, 2008; Tarnow-Mordi, 2017; Yunis, 2020 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of delayed cord clamping on anemia when compared with early cord clamping in premature births between 24 and 37 weeks.

Source: Duley, 2017; Ranjit, 2015; Salae, 2016 |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that delayed cord clamping results in little to no difference on bilirubin level when compared with early cord clamping in premature births between 24 and 37 weeks.

Source: Ranjit, 2015; Tarnow-Mordi, 2017; Yunis, 2020 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of delayed cord clamping on ferritin level when compared with early cord clamping in premature births between 24 and 37 weeks.

Source: Ranjit, 2015; Ultee, 2008 |

PICO 2: premature birth between 24 and 30 weeks

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that delayed cord clamping results in a reduction in perinatal death when compared with early cord clamping in premature births between 24 and 30 weeks.

Source: Tarnow-Mordi, 2017 |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that delayed cord clamping results in a reduction in adverse neurological outcome at 2 years when compared with early cord clamping in premature births between 24 and 30 weeks.

Source: Robledo, 2021 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of delayed cord clamping on intraventricular hemorrhage when compared with early cord clamping in premature births between 24 and 30 weeks.

Source: Tarnow-Mordi, 2017 |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that delayed cord clamping results in little to no difference in the need for erythrocyte transfusion when compared with early cord clamping in premature births between 24 and 30 weeks.

Source: Tarnow-Mordi, 2017 |

|

NO GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of delayed cord clamping on anemia when compared with early cord clamping in premature births between 24 and 30 weeks. |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that delayed cord clamping results in little to no difference in bilirubin level when compared with early cord clamping in premature births between 24 and 30 weeks.

Source: Tarnow-Mordi, 2017 |

|

NO GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of delayed cord clamping on ferritin level when compared with early cord clamping in premature births between 24 and 30 weeks. |

PICO 3: premature birth between 30 and 37 weeks

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of delayed cord clamping on perinatal death when compared with early cord clamping in premature births between 30 and 37 weeks.

Source: Ranjit, 2015 |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of delayed cord clamping on neurological outcome at 2 years when compared with early cord clamping in premature births between 30 and 37 weeks. |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of delayed cord clamping on intraventricular hemorrhage when compared with early cord clamping in premature births between 30 and 37 weeks. |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of delayed cord clamping on need for erythrocyte transfusion when compared with early cord clamping in premature births between 30 and 37 weeks.

Source: Ranjit, 2015; Salae, 2016 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of delayed cord clamping on anemia when compared with early cord clamping in premature births between 30 and 37 weeks.

Source: Ranjit, 2015; Salae, 2016 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of delayed cord clamping on bilirubin level when compared with early cord clamping in premature births between 30 and 37 weeks.

Source: Ranjit, 2015 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of delayed cord clamping on ferritin level when compared with early cord clamping in premature births between 30 and 37 weeks.

Source: Ranjit, 2015; Ultee, 2008 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

The Cochrane review of Rabe (2019) assessed the effects of delayed cord clamping, early cord clamping and umbilical cord milking on infants born at less than 37 weeks' gestation and their mothers. In November 2018, the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group Trials Register, ClinicalTrials.gov, the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) were searched for (cluster) randomized controlled trials and reference lists of retrieved studies were checked. Quasi-randomized trials were excluded. For the purpose of this guideline, only studies comparing delayed cord clamping (defined as after 60 seconds or completely stopped pulsating) with early cord clamping were included. This resulted in eight studies matching with the PICO (Dipak, 2017; Duley, 2017; Rana, 2017; Ranjit, 2015; Salae, 2016; Strauss, 2008; Tarnow-Mordi, 2017; Ultee, 2008). These studies are described in more detail below and in table 1.

Armstrong-Buisseret (2020) performed a parallel group randomized trial to assess outcomes at 2 years corrected age for children of women recruited to a trial comparing alternative policies for timing of cord clamping and immediate neonatal care at very preterm birth (follow-up Duley). Women expected to have a live birth before 32+0 weeks’ gestation were included. In total, 261 women were randomized to either delayed cord clamping (cord clamping after ³ 2 minutes; neonatal care with cord intact) or immediate cord clamping (cord clamping £ 20 seconds; neonatal care after clamping). One hundred and thirty-seven children had their cord clamped for ³ 2 minutes and 139 children had their cord clamped for less than 20 seconds. Groups were comparable at baseline. The outcome of interest was adverse neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years corrected age.

Dipak (2017) performed a randomized controlled trial to determine short term clinical effects of delayed cord clamping. Women with a gestational age between 27 and 32 weeks with preterm onset of labor were included. Exclusion criteria were women with multiple gestation, Rh-ve status, placenta previa or abruption-placenta, and those having a fetus with major congenital anomalies, hydrops, fetal growth restriction with abnormal Doppler waveforms, or evidence of fetal distress. In total, 26 infants received delayed cord clamping (at 60 seconds) and 27 infants had immediate cord clamping (at 10 seconds). Groups were comparable at baseline. Outcomes of interest were bilirubin level, transfusion, and intraventricular hemorrhage.

Duley (2017) performed a parallel group randomized trial to compare alternative policies for umbilical cord clamping and immediate neonatal care for very preterm births. Women who expected a live birth before 32 weeks of gestation regardless of mode of delivery or fetal presentation were included. Exclusion criteria were monochorionic twins, triplets, or higher-order multiple pregnancy and known major congenital malformation. In total, 130 women had their cord clamped after at least 2 minutes and their infants, if needed, received immediate neonatal stabilization and resuscitation with cord intact. These women were compared with 124 women who had their cord clamped within 20 seconds and their infants, if needed, received immediate neonatal stabilization and resuscitation after clamping. Groups were comparable at baseline. Outcomes of interest were perinatal death, intraventricular hemorrhage grade 3 or 4 and blood transfusion.

Rana (2017) performed a randomized controlled trial to determine the safety of delayed cord clamping in infants born at less than 34 weeks of gestation. Women with a gestational age of less than 34 weeks and who were in the late first stage of labor were included. Exclusion criteria were congenital malformations, serious maternal illnesses (such as severe preeclampsia or eclampsia, uncompensated heart disease, or any abnormal bleeding before cord clamping), pregnant with twins or triplets, and infants who required immediate resuscitation at birth. Fifty infants underwent delayed cord clamping (DCC: after 120 seconds) and fifty infants had early cord clamping (ECC: within 30 seconds of birth). Groups were comparable at baseline except for birth weight and small for gestational age (SGA). Infants who underwent DCC had a higher birth weight and had no SGA. Outcomes of interest were bilirubin levels and need for blood transfusion.

Ranjit (2015) performed a randomized controlled trial to assess the benefits and safety of delayed cord clamping. Neonates born between 30+0 and 36+6 weeks were included. Exclusion criteria were mothers with Rhesus negative blood group and monoamniotic/

monochorionic twins. Besides, infants who were randomized to delayed cord clamping, but needed resuscitation at birth, were excluded from the analysis. In total, 44 infants received delayed cord clamping (>2 minutes) and 50 infants had their cord clamped immediately after delivery. Groups were comparable at baseline except for maternal hemoglobin. Women who had delayed cord clamping had lower hemoglobin levels. Outcomes of interest were death anemia, blood transfusion, bilirubin level and ferritin level at 6 weeks.

Robledo (2021) performed a multicenter randomized clinical trial to determine whether delayed umbilical cord clamping decrease mortality or major disability at 2 years (follow-up Tarnow-Mordi). Infants from women who expected to deliver before 30 weeks of gestation were included. Exclusion criteria were fetal hemolytic disease, hydrops fetalis, twin-twin transfusion, genetic syndromes, and potentially lethal malformations. In total, 767 infants had delayed cord clamping (³60 seconds) and 764 infants received immediate cord clamping (within 10 seconds). Groups were comparable at baseline. The outcome of interest was major disability at 2 years of age.

Salae (2016) performed a randomized controlled trial to assess the hematocrit and microbilirubin levels after delayed and immediate cord clamping in late preterm neonates born by vaginal delivery. Women between 18 and 45 years with a gestational age between 34 and 36+6 weeks who were admitted for preterm delivery were included. Exclusion criteria were thalassemia syndrome, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes mellitus, renal impairment, placental abnormalities, fetus with major congenital anomalies, multiple

gestations, instrumental delivery and-or abnormal fetal tracing (severe fetal bradycardia, fetal distress and non-reassuring fetal heart rate). In total, 42 infants received delayed cord clamping (within 2 minutes after delivery) and 44 infants had immediate cord clamping (not defined). Groups were comparable at baseline. The outcome of interest was bilirubin level.

Strauss (2008) performed a randomized controlled trial to compare delayed with immediate cord clamping with respect to hematologic and clinical effects. Infants born before 37 weeks of gestation were included. In total, 45 infants had delayed cord clamping (at 60 seconds) and 60 infants received immediate cord clamping (within 2 to 5 seconds, but not to exceed 15 seconds after delivery). It was unclear if groups were comparable at baseline. Outcomes of interest were death, intraventricular hemorrhage, and blood transfusion of the infant.

Tarnow-Mordi (2017) performed a randomized controlled trial to determine the effects of delayed versus immediate cord clamping on neonatal outcomes. Women who were expected to deliver before 30 weeks of gestation were included. Exclusion criteria were fetal hemolytic disease, hydrops fetalis, twin–twin transfusion, genetic syndromes, and potentially lethal malformations. In total, 784 infants received delayed clamping (≥60 seconds after delivery) and 782 infants received immediate clamping of the umbilical cord (≤10 seconds after delivery). Groups were comparable at baseline. Outcomes of interest were death, intraventricular hemorrhage, bilirubin level, and transfusion.

Ultee (2008) performed a randomized controlled trial to assess the effects of delayed or early cord clamping. Infants born between 34+0 and 36+6 weeks of gestation who were delivered vaginally were included. Exclusion criteria were overt diabetes or gestational diabetes and pregnancy-induced hypertension (>20 mm Hg rise of diastole during pregnancy in combination with albuminuria). In total, 21 infants had delayed cord clamping (after 180 seconds) and 20 infants received immediate cord clamping (within 30 seconds). Groups were comparable at baseline. The outcome of interest was ferritin level at 10 weeks.

Yunis (2020) performed a pilot randomized controlled trial to assess the effect of delayed cord clamping in infants born to mothers with placental insufficiency. Infants born at less than 34 weeks of gestation whose mother had placental insufficiency were included. Exclusion criteria were infants with congenital anomalies or suspected chromosomal anomalies, and infants who needed major resuscitation steps at birth in whom delay of resuscitation measures was not possible. In total, 38 infants had delayed cord clamping (at 60 seconds) and 30 infants received immediate cord clamping (10 seconds after delivery). Groups were comparable at baseline. Outcomes of interest were death, bilirubin level, intraventricular hemorrhage, and blood transfusion.

Table 1. Description of included studies.

|

Study |

Gestation (inclusion criteria) |

Intervention |

Comparator |

Outcomes |

||

|

|

Characteristics |

Intervention |

Characteristics |

Control |

|

|

|

Armstrong-Buisseret, 2020 (follow-up Duley, 2017) |

<32 weeks |

Arm 1 (n= 132) Gestational age (median) at birth: 29 weeks (27.1 to 30.7 weeks) |

Delayed cord clamping: ³ 2 minutes |

Arm 2 (n= 129) Gestational age (median) at birth: 29.1 weeks (27.6 to 30.4 weeks) |

Immediate cord clamping: within 10 seconds |

Major disability at 2 years |

|

Dipak, 2017 |

27 to 316/7 |

Arm 1 (n= 26) Gestational age (mean±SD): 29.9 ± 1.4 weeks |

Delayed cord clamping: at 60 seconds |

Arm 2 (n= 27) Gestational age (mean±SD): 30.1 ± 1.2 weeks |

Immediate cord clamping: at 10 seconds |

Bilirubin level, blood transfusion |

|

Duley, 2017 |

<32 weeks |

Arm 1 (n= 130) Gestational age at randomisation: <26 weeks: 22 (17%) 26 to 27+6 weeks: 25 (19%) 28 to 29+6 weeks: 38 (29%) 30 to 31+6 weeks: 44 (34%) ³32 weeks: 1 (1%) |

Delayed cord clamping: ³ 2 minutes |

Arm 2 (n= 124) Gestational age at randomisation: <26 weeks: 14 (11%) 26 to 27+6 weeks: 21 (17%) 28 to 29+6 weeks: 42 (34%) 30 to 31+6 weeks: 46 (37%) ³32 weeks: 1 (1%) |

Immediate cord clamping: within 20 seconds |

Death, IVH grade 3 or 4, blood transfusion |

|

Rana, 2017 |

<34 weeks |

Arm 1 (n= 50) Gestational age (mean±SD) at baseline: 32.3 ± 1.1 weeks |

Delayed cord clamping: after 120 seconds |

Arm 2 (n= 50) Gestational age (mean±SD) at baseline: 32.4 ± 1.0 weeks |

Immediate cord clamping: within 30 seconds |

Blood transfusion, bilirubin level |

|

Ranjit, 2015 |

300/7 to 366/7 weeks |

Arm 1 (n= 50) Gestational age (mean±SD): 34.0 ± 1.6 weeks |

Delayed cord clamping: >2 minutes |

Arm 2 (n= 50) Gestational age (mean±SD): 34.1 ± 2.0 weeks |

Immediately after birth |

Death, anemia, bilirubin- and ferritin level, blood transfusion |

|

Robledo, 2021 (follow-up Tarnow-Mordi, 2017) |

<30 weeks |

Arm 1 (n= 767) Gestational age (mean±SD) at randomisation: 28 ± 2 weeks |

Delayed cord clamping: ³60 seconds |

Arm 2 (n= 764) Gestational age (mean±SD) at randomisation: 28 ± 2 weeks |

Immediate cord clamping: within 10 seconds |

Major disability at 2 years |

|

Salae, 2016 |

34 to 36+6 weeks |

Arm 1 (n= 42) Gestational age (mean±SD): 35.7 ± 1.0 weeks |

Delayed cord clamping: at 120 seconds |

Arm 2 (n= 44) Gestational age (mean±SD): 36.0 ± 0.8 weeks |

Immediate cord clamping (not defined) |

Bilirubin level |

|

Strauss, 2008 |

≤36 weeks |

Arm 1 (n= 45) Gestational age (mean±SD): NR Between 30 and 36 weeks |

Delayed cord clamping: 60 seconds |

Arm 2 (n= 60) Gestational age (mean±SD): NR Between 30 and 36 weeks |

Immediate cord clamping: within 2-5 sec, but not to exceed 15 seconds after delivery |

Death, blood transfusion, bilirubin level |

|

Tarnow-Mordi, 2017 |

<30 weeks |

Arm 1 (n= 784) Gestational age (mean±SD) at randomisation: 28 ± 2 weeks |

Delayed cord clamping: ³60 seconds |

Arm 2 (n= 782) Gestational age (mean±SD) at randomisation: 28 ± 2 weeks |

Immediate cord clamping: ≤10 seconds

|

Death, IVH, blood transfusion, bilirubin level |

|

Ultee, 2008 |

34+0 weeks to 36+6 weeks |

Arm 1 (n= 21) Gestational age (mean±SD): 36.05 ± 0.65 weeks |

Delayed cord clamping: after 180 seconds |

Arm 2 (n= 20) Gestational age (mean±SD): 36.08 ± 0.74 weeks |

Immediate cord clamping: within 30 secs (mean of 13.4 seconds (SD 5.6)) |

Ferritin level |

|

Yunis, 2020 |

<34 weeks |

Arm 1 (n= 30) Gestational age (mean±SD): 29.7 ± 1.7 weeks |

Delayed cord clamping: at 60 seconds |

Arm 2 (n= 30) Gestational age (mean±SD): 30.4 ± 1.2 weeks |

Immediate cord clamping: within 10 seconds after delivery |

Death, bilirubin level, IVH, transfusion |

Abbreviations: IVH=intraventricular haemorrhage; NR=not reported

PICO 1: premature birth between 24 and 37 weeks

Results

1. Perinatal death

Five studies reported perinatal death (Duley, 2017; Ranjit, 2015; Strauss, 2008; Tarnow-Mordi, 2017; Yunis, 2020) (Figure 1.1). In total, 61 of the 1038 infants (5.9%) who received delayed cord clamping died as compared to 93 of the 1057 infants (8.8%) who had early cord clamping (RR=0.66, 95%CI 0.44 to 1.00). This difference is clinically relevant favoring delayed cord clamping.

Figure 1.1. Perinatal death for gestational age between 24 and 37 weeks.

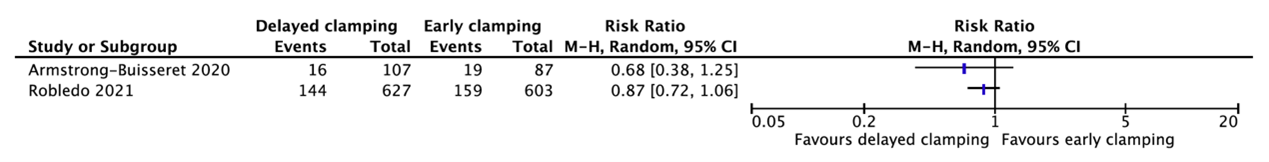

2. Neurological outcome at 2 years

Two studies reported neurological outcomes at 2 years (Armstrong-Buisseret, 2020; Robledo, 2021) (Figure 1.2). These data were not pooled as the agreement is to start pooling when including at least three studies and because of heterogeneity between the studies.

Armstrong-Buisseret (2020) reported adverse neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years corrected age. This was defined as having met the criteria for a moderate/severe impairment in any one of five functions: motor, cognitive, speech/language, hearing or vision. Adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes occurred in 16 of the 107 infants (15%) who had delayed cord clamping as compared to 19 of the 87 infants (21.8%) who had immediate cord clamping (RR=0.68, 95%CI 0.38 to 1.25). This difference is clinically relevant favoring delayed cord clamping.

Robledo (2021) reported major disability at 2 years defined as one or more of the following: cerebral palsy, severe visual loss, deafness, major problems with language or speech, or cognitive delay. Major disability occurred in 144 of the 627 infants (23%) who had delayed cord clamping as compared to 159 of the 603 infants (26%) who had immediate cord clamping (RR=0.87, 95%CI 0.72 to 1.06). This difference is clinically relevant favoring delayed cord clamping.

Figure 1.2. Neurological outcomes at 2 years for gestational age between 24 and 37 weeks.

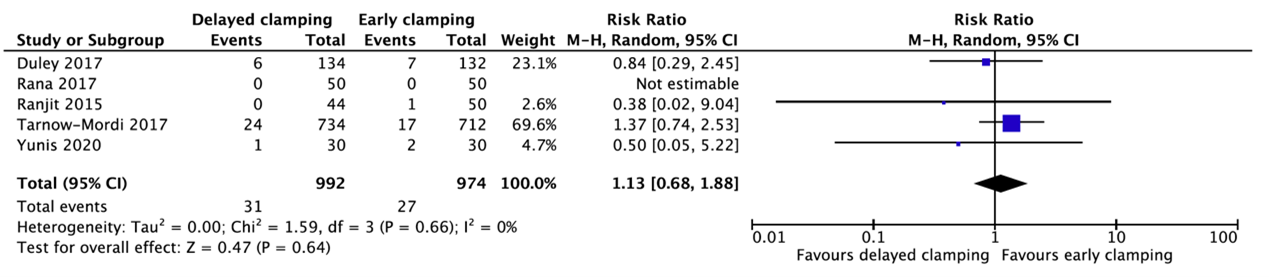

3. Intraventricular hemorrhage

Five studies reported intraventricular hemorrhage (Duley, 2017; Rana, 2017; Ranjit, 2015; Tarnow-Mordi, 2017; Yunis, 2020) (Figure 1.3). In total, 31 of the 992 infants (3.1%) who received delayed cord clamping had an intraventricular hemorrhage as compared to 27 of the 974 infants (2.8%) who had early cord clamping (RR=1.13, 95%CI 0.68 to 1.88).

Figure 1.3. Intraventricular hemorrhage for gestational age between 24 and 37 weeks.

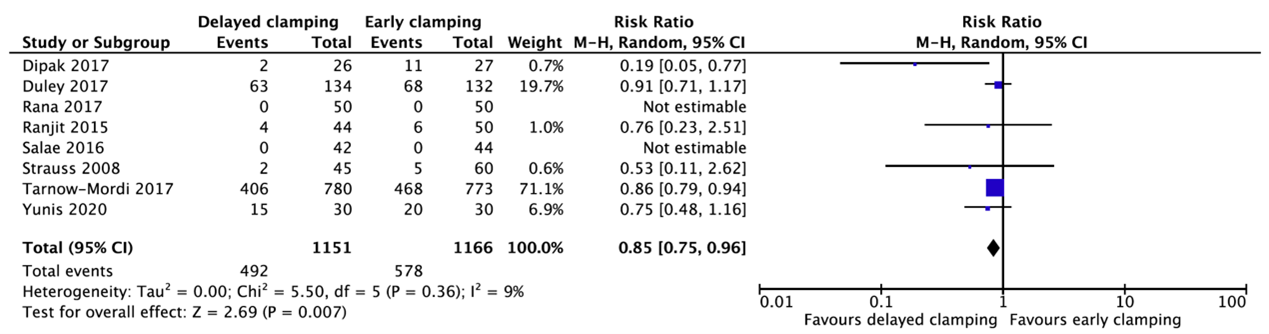

4. Need for erythrocyte transfusion

Eight studies reported about the need for erythrocyte transfusion (Dipak, 2017; Duley, 2017; Rana, 2017; Ranjit, 2015; Salae, 2016; Strauss, 2008; Tarnow-Mordi, 2017; Yunis, 2020) (Figure 1.4). In total, 492 of the 1151 infants (42.7%) who received delayed cord clamping needed a transfusion as compared to 578 of the 1166 infants (49.6%) who had early cord clamping (RR=0.85, 95%CI 0.75 to 0.96). This difference is not clinically relevant favoring delayed cord clamping.

Figure 1.4. Need for erythrocyte transfusion for gestational age between 24 and 37 weeks.

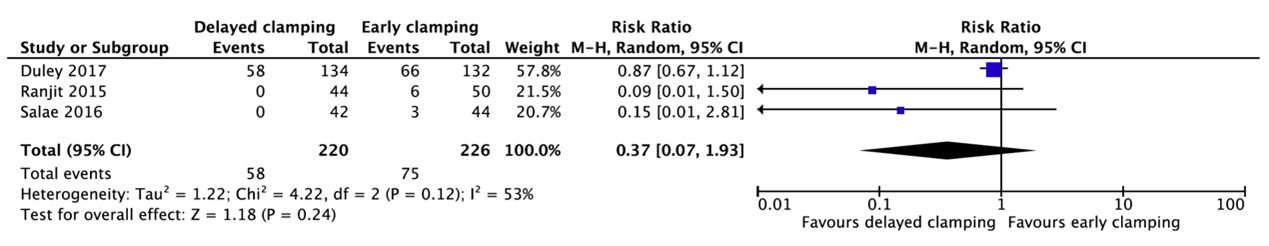

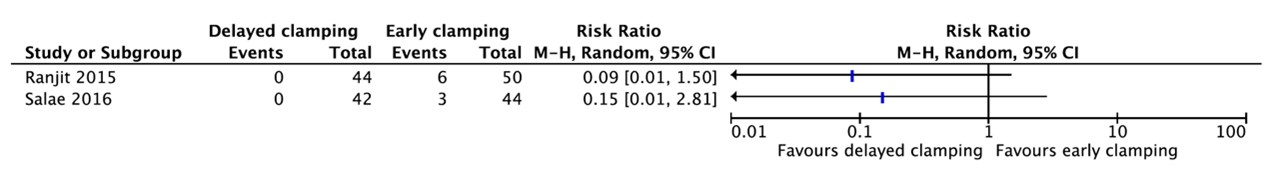

5. Anemia

Three studies reported anemia (Duley, 2017; Ranjit, 2015; Salae, 2016) (Figure 1.5). In total, 58 of the 220 infants (26.4%) who had delayed cord clamping had anemia as compared to 75 of the 226 infants (33.2%) (RR=0.37, 95%CI 0.07 to 1.93).

Figure 1.5. Anemia for gestational age between 24 and 37 weeks.

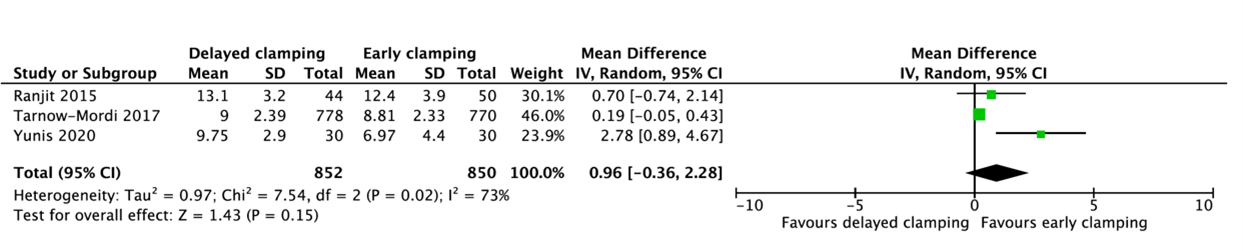

6. Bilirubin level

Three studies reported the peak serum bilirubin (Ranjit, 2015; Tarnow-Mordi, 2017; Yunis, 2020) (figure 1.6). A pooled mean difference of 0.96 mg/dL (95%CI -0.36 to 2.28) in peak bilirubin was found between delayed cord clamping and early cord clamping. This difference is not clinically relevant.

Figure 1.6. Peak serum bilirubin for gestational age between 24 and 37 weeks.

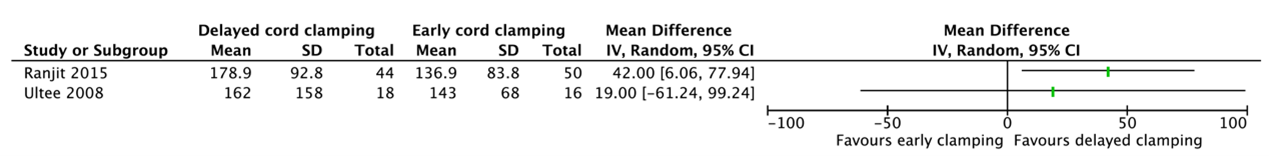

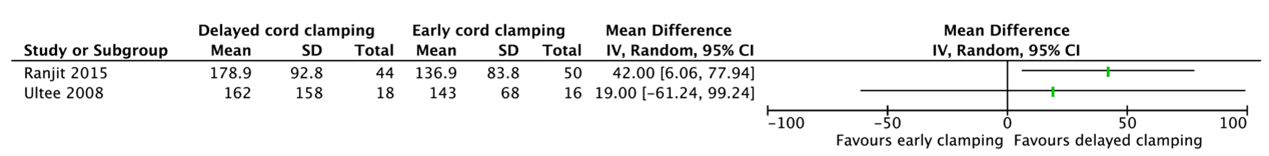

7. Ferritin level

Two studies reported a ferritin level (Ranjit, 2015; Ultee, 2008) (Figure 1.7). These data were not pooled as the agreement is to start pooling when including at least three studies and because of heterogeneity between the studies

Ranjit (2015) reported the ferritin level in infants at 6 weeks of age. Infants who had delayed cord clamping (n=44) had a mean ferritin level of 178.9 ng/mL (SD=92.8) as compared to 136.9 ng/mL (SD=83.8) for infants who had early cord clamping (n=50) (MD=42.00, 95%CI 6.06 to 77.94).

Ultee (2008) reported the ferritin level in infants at 10 weeks. Infants who had delayed cord clamping (n=18) had a mean ferritin level of 162 mg/L (SD=158) as compared to 143 mg/L (SD=68) for infants who had early cord clamping (n=16) (MD=19.00, 95%CI -61.24 to 99.24).

Figure 1.7. Ferritin level for gestational age between 24 and 37 weeks.

Level of evidence of the literature

According to GRADE, the level of evidence of randomized controlled trials start high.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure perinatal death was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (-1, risk of bias) and the 95% confidence interval crossed the line of no (clinically relevant) effect (-1, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure neurological outcome at 2 years was downgraded by two levels to low because the optimal information size was not achieved (-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure intraventricular hemorrhage was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (-1, risk of bias) and the 95% confidence interval crossed the lines of no (clinically relevant) effect (-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure need for erythrocyte transfusion was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations regarding the study population and incomplete outcome data (-1, risk of bias), and the 95% confidence interval crossed the line of no (clinically relevant) effect (-1, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure anemia was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (-1, risk of bias), and the 95% confidence interval crossed both lines of no (clinically relevant) effect (-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure bilirubin level was downgraded by three levels to low because of study limitations (-1, risk of bias) and heterogeneity between the studies (-1, inconsistency).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ferritin level was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (-1, risk of bias), differences in the definition of the outcome (-1, indirectness) and the optimal information size was not achieved (-1, imprecision).

PICO 2: premature birth between 24 and 30 weeks

Results

1. Perinatal death

Tarnow-Mordi (2017) reported that 50 of 784 infants (6.4%) who had delayed cord clamping died as compared to 70 of the 782 infants (9.0%) who had early cord clamping (RR=0.71, 95%CI 0.50 to 1.01). This difference is clinically relevant favoring delayed cord clamping.

2. Neurological outcome at 2 years

Robledo (2021) reported major disability at 2 years defined as one or more of the following: cerebral palsy, severe visual loss, deafness, major problems with language or speech, or cognitive delay. Major disability occurred in 144 of the 627 infants (23%) who had delayed cord clamping as compared to 159 of the 603 infants (26%) who had immediate cord clamping (RR=0.87, 95%CI 0.72 to 1.06). This difference is clinically relevant favoring delayed cord clamping.

3. Intraventricular hemorrhage

Tarnow-Mordi (2017) reported that 24 of 734 infants (3.3%) who had delayed cord clamping had an intraventricular hemorrhage of grade 3 or 4 as compared to 17 of the 712 infants (2.4%) who had early cord clamping (RR=1.37, 95%CI 0.74 to 2.53).

4. Need for erythrocyte transfusion

Tarnow-Mordi (2017) reported that 406 of 780 infants (52.1%) who had delayed cord clamping received a red cell transfusion (of whole blood or packed cells) as compared to 468 of the 773 infants (60.5%) who had early cord clamping (RR=0.86, 95%CI 0.79 to 0.94). This difference is not clinically relevant.

5. Anemia

Not reported.

6. Bilirubin level

Tarnow-Mordi (2017) reported the peak bilirubin in the first 7 days. Infants who had delayed cord clamping had a mean bilirubin level of 153.9 µmol/L (SD=40.9) as compared to 150.6 µmol/L (SD=39.9) (MD=3.30, 95%CI -0.73 to 7.33). This difference is not clinically relevant.

7. Ferritin level

Not reported.

Level of evidence of the literature

According to GRADE, the level of evidence of randomized controlled trials start high.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure perinatal death was downgraded by two levels to low because the 95% confidence interval crossed the line of no (clinically relevant) effect and the optimal information size was not achieved (-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure neurological outcome at 2 years was downgraded by two levels to low because the 95% confidence interval crossed the line of no (clinically relevant) effect and the optimal information size was not achieved (-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure intraventricular hemorrhage was downgraded by two levels to very low because the 95% confidence interval crossed both lines of no (clinically relevant) effect and the optimal information size was not achieved (-3, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure need for erythrocyte transfusion was downgraded by two levels to low because the 95% confidence interval crossed the line of no (clinically relevant) effect and the optimal information size was not achieved (-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure anemia could not be assessed with GRADE as this outcome measure was not studied in the included studies.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure bilirubin level was downgraded by two levels to low because the optimal information size was not achieved (-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ferritin level could not be assessed with GRADE as this outcome measure was not studied in the included studies.

PICO 3: premature birth between 30 and 37 weeks

Results

1. Perinatal death

Ranjit (2015) reported that 5 of the 50 infants (10%) who had early cord clamping died, while no deaths occurred in infants who had delayed cord clamping (RR=0.10, 95%CI 0.01 to 1.81).

2. Neurological outcome at 2 years

Not reported.

3. Intraventricular hemorrhage

Ranjit (2015) reported that 1 of the 50 infants (2%) who had early cord clamping had an intraventricular hemorrhage, while no intraventricular hemorrhage occurred in infants who had delayed cord clamping (RR=0.38, 95%CI 0.02 to 9.04).

4. Need for erythrocyte transfusion

Ranjit (2015) reported that 4 of the 44 infants (9.1%) who had delayed cord clamping received packed cell transfusion as compared to 6 of the 50 infants (12%) who had early cord clamping (RR=0.76, 95%CI 0.23 to 2.51).

Salae (2016) reported that no blood transfusions were needed in infants who had either delayed or early cord clamping.

5. Anemia

Two studies reported anemia (Ranjit, 2015; Salae, 2016) (Figure 3.1). These data were not pooled as the agreement is to start pooling when including at least three studies.

Ranjit (2015) reported that 6 of the 50 infants (12%) who had early cord clamping had anemia on day 1, while this did not occur in infants who had delayed cord clamping (RR=0.09, 95%CI 0.01 to 1.50).

Salae (2016) reported that 3 of the 44 infants (6.8%) who had early cord clamping were anemic (Hct <40%), while this did not occur in infants who had delayed cord clamping (RR=0.15, 95%CI 0.01 to 2.18).

Figure 3.1. Anemia for gestational age between 30 and 37 weeks.

6. Bilirubin level

Ranjit (2015) reported the mean peak bilirubin. Infants who had delayed cord clamping had a mean peak bilirubin of 13.1 mg/dL (SD=3.2) as compared to 12.4 mg/dL (SD=3.9) (MD=0.70, 95%CI -0.74 to 2.14).

7. Ferritin level

Two studies reported a ferritin level (Ranjit, 2015; Ultee, 2008) (Figure 3.2). These data were not pooled as the agreement is to start pooling when including at least three studies and because of heterogeneity between the studies.

Ranjit (2015) reported the ferritin level in infants at 6 weeks of age. Infants who had delayed cord clamping (n=44) had a mean ferritin level of 178.9 ng/mL (SD=92.8) as compared to 136.9 ng/mL (SD=83.8) for infants who had early cord clamping (n=50) (MD=42.00, 95%CI 6.06 to 77.94).

Ultee (2008) reported the ferritin level in infants at 10 weeks. Infants who had delayed cord clamping (n=18) had a mean ferritin level of 162 mg/L (SD=158) as compared to 143 mg/L (SD=68) for infants who had early cord clamping (n=16) (MD=19.00, 95%CI -61.24 to 99.24).

Figure 3.2. Ferritin level for gestational age between 30 and 37 weeks.

Level of evidence of the literature

According to GRADE, the level of evidence of randomized controlled trials start high.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure perinatal death was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (-1, risk of bias) and the 95% confidence interval crossed both lines of no (clinically relevant) effect (-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure neurological outcome at 2 years could not be assessed with GRADE as this outcome measure was not studied in the included studies.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure intraventricular hemorrhage was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (-1, risk of bias) and the 95% confidence interval crossed both lines of no (clinically relevant) effect (-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure need for erythrocyte transfusion was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (-1, risk of bias), differences in the direction of the effect (-1, inconsistency) and the optimal information size was not achieved (-1, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure anemia was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (-1, risk of bias) and the optimal information size was not achieved (-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure bilirubin level was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (-1, risk of bias) and the optimal information size was not achieved (-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ferritin level was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (-1, risk of bias) and the optimal information size was not achieved (-2, imprecision).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the (un)favorable effects of delayed cord clamping in premature neonates compared to early cord clamping on the morbidity and mortality of the child?

| P: |

P1 = premature birth between 24 and 37 weeks P2 = 24 to 30 weeks P3 = 30 to 37 weeks (subgroup: 30 to 34 weeks and 34 to 37 weeks) |

| I: |

delayed cord clamping (after at least 60 seconds or after the umbilical cord completely stopped pulsating; no cord milking) |

| C: | early cord clamping |

| O: | perinatal death, intraventricular hemorrhage, need for erythrocyte transfusion, anemia, bilirubin level, ferritin level and neurological outcome at 2 years |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered perinatal death and neurological outcome at 2 years as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), need for erythrocyte transfusion, anemia, bilirubin level and ferritin level as an important outcome measure for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

- Intraventricular hemorrhage: from grade 3

- Ferritin level: in the newborn between 2 and 4 months

For the other outcomes, the working group did not define the outcome measures a priori but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined a 1% difference for perinatal death (RR < 0.99 or > 1.01) and 10% for neurological outcomes at 2 years (RR < 0.90 to >1.10) as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference. For the other outcomes, a 25% difference for dichotomous outcomes (RR < 0.8 or > 1.25) and 0.5 SD for continuous outcomes was taken as minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 2010 until the 20th of July, 2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 819 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic review (searched in at least two databases, and detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment and results of individual studies available), randomized controlled trial, or observational studies comparing delayed cord clamping with early cord clamping;

- The study population had to meet the criteria as defined in the PICO; and

- Full-text English language publication.

Eighty-one studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 77 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and four studies were included (one systematic review of Rabe 2019 and three other randomized controlled trials performed by Armstrong-Buisseret 2020, Robledo 2021 and Yunis 2020). Rabe 2019 defined a broader PICO than the PICO defined for this module (it also included studies about umbilical cord milking and less than 60 seconds for delayed cord clamping). Therefore, eight randomized controlled trials included in the review were selected for the literature analysis (Dipak, 2017; Duley, 2017; Rana, 2017; Ranjit, 2015; Salae, 2016; Strauss, 2008; Tarnow-Mordi, 2017; Ultee, 2008).

After our search date, two systematic reviews performed by Seidler 2023 were published. However, since the same studies were included in these systematic reviews of Seidler as in Rabe 2019, this had no consequences for the literature analysis.

Studies on intact cord rescusitation (as the ABC3-trial by Knol 2024) where not included for analysis, yet described in the discussion, as this new technique is mostly used in an academic setting and is not yet general practice.

Results

The eight randomized controlled trials included in the systematic review of Rabe 2019 and three randomized controlled trials performed by Armstrong-Buisseret 2020, Robledo 2021 and Yunis 2020 were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in table 1 and the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables. A subgroup analysis was performed based on gestational age: <30 weeks (24 to 30 weeks) and >30 weeks (to 37 weeks) of gestation. It was not possible to perform a subgroup analysis for 30 to 34 weeks and 34 to 37 weeks because of lack of data.

Referenties

- Altit G, Hamilton D, O’Brien K. Skin-to-skin care (SSC) for term and preterm infants. Paediatr Child 2024 Jul 22; 29(4): 238-254.

- Paediatr Child 2024 Jul 22; 29(4): 238-254.

- Armstrong-Buisseret L, Powers K, Dorling J, Bradshaw L, Johnson S, Mitchell E, Duley L. Randomised trial of cord clamping at very preterm birth: outcomes at 2 years. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2020 May;105(3):292-298. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2019-316912. Epub 2019 Aug 1. PMID: 31371434; PMCID: PMC7363783.

- Duley L, Dorling J, Pushpa-Rajah A, Oddie SJ, Yoxall CW, Schoonakker B, Bradshaw L, Mitchell EJ, Fawke JA; Cord Pilot Trial Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of cord clamping and initial stabilisation at very preterm birth. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2018 Jan;103(1):F6-F14. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-312567. Epub 2017 Sep 18. PMID: 28923985; PMCID: PMC5750367.

- Knol R, Brouwer E, van den Akker T, DeKoninck PLJ, Onland W, Vermeulen MJ, de Boode WP, van Kaam AH, Lopriore E, Reiss IKM, Hutten GJ, Prins SA, Mulder EEM, d'Haens EJ, Hulzebos CV, Bouma HA, van Sambeeck SJ, Niemarkt HJ, van der Putten ME, Lebon T, Zonnenberg IA, Nuytemans DH, Willemsen SP, Polglase GR, Steggerda SJ, Hooper SB, Te Pas AB. Physiological versus time based cord clamping in very preterm infants (ABC3): a parallel-group, multicentre, randomised, controlled superiority trial. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2024 Dec 4;48:101146. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2024.101146. PMID: 39717227; PMCID: PMC11664066.

- Madar J, Roehr CC, Ainsworth S, Ersdal H, Morley C, Rüdiger M, Skåre C, Szczapa T, Te Pas A, Trevisanuto D, Urlesberger B, Wilkinson D, Wyllie JP. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: Newborn resuscitation and support of transition of infants at birth. Resuscitation. 2021 Apr;161:291-326. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.014. Epub 2021 Mar 24. PMID: 33773829.

- McDonald SJ, Middleton P, Dowswell T, Morris PS. Effect of timing of umbilical cord clamping of term infants on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jul 11;2013(7):CD004074. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004074.pub3. PMID: 23843134; PMCID: PMC6544813.

- Nederlandse Reanimatie Raad. Richtlijnen Reanimatie in Nederland. Reanimatie en ondersteuning van de transitie van het kind direct na de geboorte. Available from: www.reanimatieraad.nl

- Rana A, Agarwal K, Ramji S, Gandhi G, Sahu L. Safety of delayed umbilical cord clamping in preterm neonates of less than 34 weeks of gestation: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2018 Nov;61(6):655-661. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2018.61.6.655. Epub 2018 Oct 29. PMID: 30474011; PMCID: PMC6236088.

- Ranjit T, Nesargi S, Rao PN, Sahoo JP, Ashok C, Chandrakala BS, Bhat S. Effect of early versus delayed cord clamping on hematological status of preterm infants at 6 wk of age. Indian J Pediatr. 2015 Jan;82(1):29-34. doi: 10.1007/s12098-013-1329-8. Epub 2014 Feb 6. PMID: 24496587.

- Rabe H, Gyte GM, Díaz-Rossello JL, Duley L. Effect of timing of umbilical cord clamping and other strategies to influence placental transfusion at preterm birth on maternal and infant outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Sep 17;9(9):CD003248. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003248.pub4. PMID: 31529790; PMCID: PMC6748404.

- Rana A, Agarwal K, Ramji S, Gandhi G, Sahu L. Safety of delayed umbilical cord clamping in preterm neonates of less than 34 weeks of gestation: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2018 Nov;61(6):655-661. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2018.61.6.655. Epub 2018 Oct 29. PMID: 30474011; PMCID: PMC6236088.

- Robledo KP, Tarnow-Mordi WO, Rieger I, Suresh P, Martin A, Yeung C, Ghadge A, Liley HG, Osborn D, Morris J, Hague W, Kluckow M, Lui K, Soll R, Cruz M, Keech A, Kirby A, Simes J; APTS Childhood Follow-up Study collaborators. Effects of delayed versus immediate umbilical cord clamping in reducing death or major disability at 2 years corrected age among very preterm infants (APTS): a multicentre, randomised clinical trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022 Mar;6(3):150-157. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00373-4. Epub 2021 Dec 8. Erratum in: Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022 Jan 21;: PMID: 34895510.

- Strauss RG, Mock DM, Johnson KJ, Cress GA, Burmeister LF, Zimmerman MB, Bell EF, Rijhsinghani A. A randomized clinical trial comparing immediate versus delayed clamping of the umbilical cord in preterm infants: short-term clinical and laboratory endpoints. Transfusion. 2008 Apr;48(4):658-65. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01589.x. Epub 2008 Jan 10. PMID: 18194383; PMCID: PMC2883857.

- Tarnow-Mordi W, Morris J, Kirby A, Robledo K, Askie L, Brown R, Evans N, Finlayson S, Fogarty M, Gebski V, Ghadge A, Hague W, Isaacs D, Jeffery M, Keech A, Kluckow M, Popat H, Sebastian L, Aagaard K, Belfort M, Pammi M, Abdel-Latif M, Reynolds G, Ariff S, Sheikh L, Chen Y, Colditz P, Liley H, Pritchard M, de Luca D, de Waal K, Forder P, Duley L, El-Naggar W, Gill A, Newnham J, Simmer K, Groom K, Weston P, Gullam J, Patel H, Koh G, Lui K, Marlow N, Morris S, Sehgal A, Wallace E, Soll R, Young L, Sweet D, Walker S, Watkins A, Wright I, Osborn D, Simes J; Australian Placental Transfusion Study Collaborative Group. Delayed versus Immediate Cord Clamping in Preterm Infants. N Engl J Med. 2017 Dec 21;377(25):2445-2455. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1711281. Epub 2017 Oct 29. PMID: 29081267.

- Ultee CA, van der Deure J, Swart J, Lasham C, van Baar AL. Delayed cord clamping in preterm infants delivered at 34 36 weeks' gestation: a randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2008 Jan;93(1):F20-3. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.100354. Epub 2007 Feb 16. PMID: 17307809.

- WHO. Guideline: Delayed umbilical cord clamping for improved maternal and infant health and nutrition outcomes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for intervention studies

Research question: What are the (un)favorable effects of delayed cord clamping in premature neonates compared to early cord clamping on the morbidity and mortality of the child?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Armstrong-Buisseret, 2020 |

Type of study: Parallel group randomised trial

Setting and country: Eight tertiary maternity units, UK.

Funding and conflicts of interest: This trial is independent research funded by the NIHR under its Programme Grants for Applied Research funding scheme (RPPG0609-10107). One author reports grants from NIHR during the conduct of the trial; another author reports memberships to CTUs funded by NIHR. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

|

Inclusion criteria: Women expected to have a live birth before 32+0 weeks’ gestation (very preterm)

Exclusion criteria: Not reported

N total at baseline: Intervention: 132 women / 137 babies Control: 129 women / 139 babies

Important prognostic factors2: Women’s age mean ± SD: I: 30.5 ± 6.3 years C: 29.4 ± 6.7 years

Gestation at birth (median) I: 29 weeks (27.1 to 30.7 weeks) C: 29.1 weeks (27.6 to 30.4 weeks)

Groups comparable at baseline

|

Delayed cord clamping: cord clamping after ³ 2 minutes; neonatal care with cord intact

|

Immediate cord clamping: cord clamping £ 20 seconds; neonatal care after clamping

|

Length of follow-up: 2 years

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 16 (11.9%) Reasons: oral consent only, withdrew or lost to follow-up

Control: 27 (20%) Reasons: lost to follow-up or withdrew

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: 4 (3.0%) Reasons: insufficient data

Control: 5 (3.7%) Reasons: insufficient data

|

Adverse neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years: I: 16/107 (15.0%) C: 19/87 (21.8%%)

|

Author’s conclusion “Deferred clamping and immediate neonatal care with cord intact may reduce the risk of death or adverse neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years of age for children born very premature”.

Limitation - Low long-term follow-up rates - Screening test with poor diagnostic accuracy and routine clinical assessments have poor sensitivity for evaluating cognitive outcomes |

|

Dipak, 2017 |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial

Setting and country: A tertiary care hospital in Mumbai, India

Funding and conflicts of interest: No funding. No conflicts of interest were stated.

|

Inclusion criteria: Women with a gestational age between 27 and 32 weeks with preterm onset of labor

Exclusion criteria - Multiple gestation - Placenta previa - Abruption-placenta - Major congenital anomalies - Hydrops - Fetal growth restriction with abnormal Doppler waveforms - Evidence of fetal distress

N total at baseline: Intervention: 26 Control: 27

Important prognostic factors2: Age I: 26.6 (SD=3.9) C: 26.6 (SD=4.2)

Gestational age I: 30.1 (SD=1.2) C: 29.9 (SD=1.4)

Groups were comparable at baseline.

|

Delayed cord clamping: at 60 seconds

Infant was held in a pre-warmed towel approximately 10-15 inches below the introitus at vaginal delivery/below the level of placental incision in caesarean delivery |

Immediate cord clamping: at 10 seconds

Infant was held supine at level of introitus/placental incision |

Length of follow-up Up to 72 hours after birth

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported |

Red cells transfusion I: 2/26 (7.7%) C: 11/27 (40.7%)

Mean total serum bilirubin at 72 hours I: 9.4 ± 3.1 mg/dL C: 5.6 ± 1.7 mg/dL

Peak serum bilirubin (weighted mean difference ± SD) 2.1 ± 0.9 mg/dL

|

Author’s conclusion “In preterm neonates delayed cord clamping along with lowering the infant below perineum or incision site and administration of ergometrine to mother has significant benefits in terms of increase in hematocrit, higher temperature on admission, and higher blood pressure and urinary output during perinatal transition”.

Limitations: Small sample size |

|

Duley, 2017 |

Type of study: Parallel group randomised trial

Setting and country: Eight tertiary maternity units, UK

Funding and conflicts of interest: This trial is independent research funded by the National Institute for HealthResearch (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research funding scheme (RPPG-0609-10107). No conflicts of interest.

|

Inclusion criteria: Women who expected a live birth before 32 weeks of gestation regardless of mode of delivery or fetal presentation

Exclusion criteria - Monochorionic twins, triplets, or higher-order multiple pregnancy -Known major congenital malformation

N total at baseline: Intervention: 130 Control: 124

Important prognostic factors2: Age I: 30.3 (SD=6.1) C:29.2 (SD=6.6)

Gestation <26 weeks I: 22 (17%) C: 14 (11%)

Gestation 26 to 27+6 weeks I: 25 (19%) C: 21 (17%)

Gestation 28 to 29+6 weeks I: 38 (29%) C: 42 (34%)

Gestation 30 to 31+6 weeks I: 44 (34%) C: 46 (37%)

Groups comparable at baseline

|

Delayed cord clamping (³2 minutes)

Received immediate neonatal stabilization and resuscitation with cord intact |

Immediate cord clamping (within 20 seconds)

Received immediate neonatal stabilization and resuscitation after clamping. |

Length of follow-up: Until discharge

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Death I: 7/135 (5.2%) C: 15/135 (11.1%)

IVH grade 3-4 I: 6/134 (4.5%) C: 7/132 (5.3%)

Blood transfusion in infants I: 63/134 (47.0%) C: 68/132 (51.5%)

Blood transfusion for anemia: I: 58/134 (43.3%) C: 66/132 (50%)

|

Author’s conclusion “This is promising evidence that clamping after at least 2 min and immediate neonatal care with cord intact at very preterm birth may improve outcome”.

Remarks:

|

|

Rana, 2017 |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial

Setting and country: Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of a tertiary-level teaching hospital in India

Funding and conflicts of interest: Source of funding was not reported. No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

|

Inclusion criteria: Pregnant women whose pregnancies had reached less than 34 weeks’ gestation and were in the late first stage of labor

Exclusion criteria: - Any known congenital malformations - Serious maternal illnesses: severe preeclampsia or eclampsia, uncompensated heart disease, any abnormal bleeding before cord clamping - Twins or triplets - Babies requiring immediate resuscitation at birth

N total at baseline: Intervention: 50 Control: 50

Important prognostic factors2: Age I: 32.3± 1.1 weeks C: 32.4± 1.0 weeks

Birth weight I: 1,818±282 C: 1,679±373

Small for gestational age (SGA) I: 0 C: 4 (8%)

Groups comparable at baseline, except for birth weight and SGA

|

Delayed cord clamping: after 120 seconds

|

Early cord clamping: within 30 seconds of birth |

Length of follow-up:

Loss-to-follow-up: No

Incomplete outcome data: No

|

Bilirubin levels (mg/dL) at 72 hours of birth) I: 6.6 ± 1.2 mg/dL C: 8.7±1.6 mg/dL

Intraventricular hemorrhage (not defined) I: 0/50 C: 0 /50

Need for blood transfusion I: 0/50 C: 0/50

|

Author’s conclusion: “DCC benefits preterm neonates with no significant adverse effects”.

Remarks: - Small number of study subjects - Some pregnant women were excluded after randomization which might result in bias

|

|

Ranjit, 2015 |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial

Setting and country: Tertiary care hospital in South India

Funding and conflicts of interest: Source of funding not reported. No conflicts of interest.

|

Inclusion criteria: Neonates born between 30+0 and 36+6 weeks

Exclusion criteria: - Mothers with Rhesus negative blood group - Monoamniotic/ monochorionic twins - Infants who were randomized to delayed cord clamping, but needed resuscitation at birth

N total at baseline: Intervention: 44 Control: 50

Important prognostic factors2: Age I: 34.0 ± 1.6 weeks C: 34.1 ± 2.0 weeks

Groups comparable at baseline, except for maternal hemoglobin (lower in delayed cord clamping group)

|

Delayed cord clamping; >2 minutes |

Immediate cord clamping: immediate after birth |

Length of follow-up:

Loss-to-follow-up: At follow-up: Intervention: 3 (6.8%) Reasons: lost to follow-up

Control: 9 (18%) Reasons: lost to follow-up or death

Incomplete outcome data: No

|

Death I: 0/44 C: 5/50 (10%)

Intraventricular hemorrhage (not defined) I: 0/44 C: 1/50 (1%)

Anemia on day 1 I: 0/44 C: 6/50 (12%)

Mean peak bilirubin levels (mg/dL) I: 13.1 ± 3.2 mg/dL C: 12.4±3.9 mg/dL

Ferritin (ng/mL) I: 178.9±92.8 ng/mL C: 136.9±83.8 ng/mL

Blood transfusion I: 4/44 (9.1%) C: 6/50 (12%) |

Author’s conclusion “Delaying the cord clamping by 2 min, significantly improves the hematocrit value at birth and this beneficial effect continues till at least 2nd month of life”

Limitations - Small sample size - No long term developmental outcomes |

|

Robledo, 2021 (follow-up Tarnow-mordi) |

Type of study: International, open-label, parallel, pragmatic, randomised, controlled, superiority trial.

Setting and country: 25 centres in seven countries.

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funded by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. The authors declare no competing interests.

|

Inclusion criteria: Fetuses were eligible if obstetricians or maternal–fetal medicine specialists considered that they might be delivered before 30 weeks of gestation

Exclusion criteria: - Fetal haemolytic disease - Hydrops fetalis - Genetic syndromes - Potentially lethal malformations

N total at baseline: Intervention: 767 Control: 764

Important prognostic factors2: Gestational age I: 28 ± 2 weeks C: 28 ± 2 weeks

Groups comparable at baseline |

Delayed cord clamping (³60 seconds) |

Immediate cord clamping (within 10 seconds) |

Length of follow-up: 2 years

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: 58 (7.6%) Reasons: missing at least one component of primary outcome

Control: 54 (7.1%) Reasons: missing at least one component of primary outcome |

Major disability at 2 years I: 144/627 (23%) C: 159/603 (26%)

|

Author’s conclusion “Clamping the umbilical cord at least 60 s after birth reduced the risk of death or major disability at 2 years by 17%, reflecting a 30% reduction in relative mortality with no difference in major disability”.

Remarks - Staff and parents were not blinded to the intervention and assessments of outcome, but researchers who assessed disability were unaware of randomised group and death is an outcome at low risk of observer bias - Did not record heart rate or time to first breath or to regular breathing - Clamping occurred before 60 s in 26% of infants assigned to delayed clamping, largely reflecting clinical concerns for the infant. |

|

Salae, 2016 |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial

Setting and country: Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Thammasat University Hospital in Pathumthani, Thailand

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funding for this study was supported by the Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University, Pathumthani, Thailand. No conflicts of interest.

|

Inclusion criteria: Women between 18 and 45 years with a gestational age between 34 and 36+6 weeks who were admitted for preterm delivery

Exclusion criteria - Thalassemia syndrome - Preeclampsia - Gestational diabetes mellitus - Placental abnormalities - Fetus with major congenital anomalies - Multiple gestations - Instrumental delivery and-or abnormal fetal tracing (severe fetal bradycardia, fetal distress and non-reassuring fetal heart rate).

N total at baseline: Intervention: 42 Control: 44

Important prognostic factors2: Age I: 26.2 ± 6.2 years C: 28.7 ± 5.0 years

Gestational age I: 35.7 ± 1.0 years C: 36.0 ± 0.8 years

Groups were comparable at baseline

|

Delayed cord clamping: within 2 minutes

“Following birth, the babies were placed at the same level of maternal body trunk. The babies in the DCC group were wrapped with a sterile towel. During the process, care was taken not to allow the umbilical cord to be overstretched”.

“Neonates from either group were transferred to the newborn unit and underwent routine standard management by a pediatrician who attended the newborn unit”. |

Immediate cord clamping (not defined) |

Length of follow-up: Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 8 (16%) Reasons: Apgar score at 1 min <7 or non-reassuring fetal heart rate

Control: 6 (12%) Reasons: Apgar score at 1 min <7 or non-reassuring fetal heart rate

Incomplete outcome data: No

|

Microbilirubin at 48 hours I: 9.4±1.3 mg/dL C: 8.6 ±2.1 mg/dL

Blood transfusion I: 0/42 C: 0/44

Anemia (Hct <40%) I: 0 C: 3 |

Author’s conclusion “The DCC procedure could raise the Hct level in the late preterm newborns without serious adverse effects”.

Limitations - No long-term follow-up - High drop-out rate

|

|

Strauss, 2008 |

Type of study: Prospective randomized clinical trial

Setting and country: US

Funding and conflicts of interest: Source of funding not reported. No conflicts of interest.

|

Inclusion criteria: Infants born before 37 weeks

Exclusion criteria: Not reported

N total at baseline: Intervention: 45 Control: 60

Important prognostic factors2: Not reported

Unclear if groups were comparable at baseline

|

Delayed cord clamping (60 seconds) |

Immediate cord clamping (within 2 to 5 seconds, but not to exceed 15 seconds after delivery) |

Length of follow-up: Not reported

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Some missing data: for blood transfusion and bilirubin levels is data missing for one patient in the immediate cord clamping group. For outcome haematocrit, missing data is almost similar for both groups. |

Perinatal death I: 0/45 C: 0 /60

Red blood cell transfusion in infant I: 2/45 (4.4%) C: 5/60 (8.3%)

Serum bilirubin levels (at start of phototherapy) I: 11 mg/dL C: 11 mg/dL

|

Author’s conclusion Although a 1-minute delay in cord clamping significantly increased RBC volume/ mass and Hct, clinical benefits were modest. Clinically significant adverse effects were not detected. Consider a 1-minute delay in cord clamping to increase RBC volume/mass and RBC iron, for neonates 30 to 36 weeks' gestation, who do not need immediate resuscitation.

Remarks: No patient characteristics were presented |

|

Tarnow-Mordi, 2017 |

Type of study: Randomized pilot trial

Setting and country: 25 centres in 7 countries

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funded by supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and by the NHMRC Clinical Trials Centre, University of Sydney. No conflicts of interest.

|

Inclusion criteria: Women who were expected to deliver before 30 weeks of gestation

Exclusion criteria: - Fetal hemolytic disease - Hydrops fetalis - Twin–twin transfusion - Genetic syndromes - Potentially lethal malformations

N total at baseline: Intervention: 784 Control: 782

Important prognostic factors2: Gestational age I: 28 ± 2 weeks C: 28 ± 2 weeks

Groups comparable at baseline

|

Delayed clamping (≥60 seconds after delivery) |

Immediate clamping of the umbilical cord (≤10 seconds after delivery) |

Length of follow-up: Not reported

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: I: 36 had missing data C: 33 had missing data |

Perinatal death I: 50/784 (6.4%) C: 70/782 (9.0%)

IVH grade 3 or 4 I: 24/734 (3.3%) C: 17/712 (2.4%)

Blood transfusion in infant (whole blood or packed cells) I: 406/780 (52.1%) C: 468/773 (60.5%)

Peak bilirubin in first 7 days I: 153.9 µmol/L (SD=40.9) à 9 mg/dL (SD=2.39) C: 150.6 µmol/L (SD=39.9) à 8.81 mg/dL (SD=2.33) |

Author’s conclusion “Among preterm infants, delayed cord clamping did not result in a lower incidence of the combined outcome of death or major morbidity at 36 weeks of gestation than immediate cord clamping”.

Remarks Unblinded trial |

|

Ultee, 2008 |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial

Setting and country: Netherlands

Funding and conflicts of interest: Source of funding not reported; report no competing interests. |

Inclusion criteria: - Infants born at 34 weeks and 0 days to 36 weeks and 6 days gestational age - Delivered vaginally - Only Caucasian parents

Exclusion criteria: - Overt diabetes or gestational diabetes (>20 mm Hg rise of diastole during pregnancy in combination with albuminuria)

N total at baseline: Intervention: 21 Control: 20

Important prognostic factors2: Gestational age (weeks) I: 36.05 ± 0.65 weeks C: 36.08 ± 0.74 weeks

Groups were comparable at baseline

|

Delayed cord clamping after 180 seconds

|

Immediate cord clamping within 30 secs (mean of 13.4 seconds (SD 5.6))

|

Length of follow-up: 10 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: I: 2 C: 1

Incomplete outcome data: I: 2 C: 1 |

Ferritin levels I: 162 ± 158 mg/L C: 143 ± 68 mg/L

|

Author’s conclusion Immediate clamping of the umbilical cord should be discouraged.

Remarks: Small number of study subjects |

|

Yunis, 2020 |

Type of study: Pilot, prospective, non-blinded, randomized controlled trial

Setting and country: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) of Mansoura University Children’s Hospital, Mansoura, Egypt

Funding and conflicts of interest: Source of funding not reported. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

|

Inclusion criteria: Preterm infants, less than 34 weeks’ gestation, delivered to mothers with antenatal diagnosis of placental insufficiency

Exclusion criteria: - Infants with a congenital anomaly or suspected chromosomal anomaly - Infants who required major resuscitation steps at birth in whom delay of resuscitation measures was not possible

N total at baseline: Intervention: 30 Control: 30

Important prognostic factors2: Gestational age (weeks) I: 29.7 ± 1.7 weeks C: 30.4 ± 1.2 weeks

Groups were comparable at baseline

|

Delayed cord clamping: 60 seconds

Keeping the infant 2–3 in. below the level of the maternal introitus or placenta, with caution not to put traction on the cord, for 60 s with an intact umbilical cord followed by ligation of the cord at 2–3 cm from the umbilical stump without cord milking |

Immediate cord clamping: 10 seconds after delivery

Infant’s umbilical cord was immediately clamped within 10 s after delivery of the whole body of the infant at 2–3 cm from the umbilical stump without cord milking |

Length of follow-up: 2 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 8 (21%) Required immediate resuscitation

Control: 0

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Neonatal mortality (before hospital discharge) I: 4/30 (13.3%) C: 3/30 (10%)

Packed red blood cell transfusion I: 15/30 (50%) C: 20/30 (66.7%)

Peak serum bilirubin I: 9.75 ± 2.90 mg/dL C: 6.97 ± 4.40 mg/dL

IVH grades 3 or 4 I: 1/30 (3%) C: 2/30 (7%)

|

Author’s conclusion In conclusion, DCC compared with ICC increased stem cell transfusion and decreased early- and late-onset anemia in preterm infants with placental insufficiency.

Limitations - Small sample size - No intention-to-treat |

Risk of bias table for intervention studies

Research question: What are the (un)favorable effects of delayed cord clamping in premature neonates compared to early cord clamping on the morbidity and mortality of the child?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Armstrong-Buisseret, 2020 (follow-up of Cord Pilot Trial) |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Computer was used for sequence generation and stratified by centre with balanced blocks of randomly varying size, created by NCTU

|

Definitely yes;

Reason: Sealed envelopes were used. Once the label was completed, the patient was considered randomized, even if the envelope was not opened. |

Probably no;

Reason: Attending clinicians could not be blinded. It was unclear whether the mother knew or not. Outcome assessors were blinded. |

Probably yes;

Reason: No loss to follow-up or missing data. |

No information

Reason: The trial protocol was for a feasibility study and clinical outcomes are unclear. |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted. |

Some concerns |

|

Dipak, 2017 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: A random number sequence with variable block size of 3 or 6 using a ‘Random Allocation Software’ program was used.

|

Definitely yes;

Reason: Serially numbered, opaque, sealed and identical envelopes were used. The random allocation sequence was generated by a statistician who was not a part of the study.

|

No information |

Probably yes;

Reason: No loss to follow-up or missing data. |

Probably yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported. |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted. |

Some concerns |

|

Duley, 2017 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Sequence generation was by computer, stratified by centre with balanced blocks of randomly varying size, created by NCTU.

|

Definitely yes;

Reason: Sealed envelopes. On the envelope was a label to record the date, time, woman’s initials, her date of birth and gestation. Once this label was completed, she was considered randomized, even if the envelope was not opened.

|

Probably no;

Reason: Assessor and clinicians were blinded, but patients could probably not be blinded. |

Probably yes;

Reason: No loss to follow-up or missing data. |

No information

Reason: The trial protocol was for a feasibility study and clinical outcomes are unclear. |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted. |

Some concerns |

|

Rana, 2017 |

Definitely yes;