Diagnostiek

Uitgangsvraag

Hoe dient de diagnose van een acute scaphoïdfractuur gesteld te worden?

- Welke aanvullende diagnostiek (een CT, MRI of herhaalde röntgenopnames na 10 dagen) heeft de voorkeur in het diagnosticeren van een scaphoïdfractuur bij patiënten waarbij geen fractuur kon worden vastgesteld op de initiële röntgenopnames (bij de eerste presentatie van klachten)?

- Welke aanvullende diagnostiek dient te worden uitgevoerd, indien geïndiceerd, bij een scaphoïdfractuur die wordt vastgesteld op de initiële röntgenfoto’s?

Aanbeveling

Aanbeveling-1

Maak bij negatieve initiële röntgenopnames en een sterke klinische (dan wel persisterende) verdenking op een scaphoïdfractuur aanvullend een CT van de pols.

Aanbeveling-2

Overweeg laagdrempelig bij een bewezen scaphoïdfractuur op initiële röntgenopnamen aanvullend een CT van de pols binnen 72 uur na diagnosestelling ter beoordeling van fractuurlocatie, comminutie en dislocatie.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Deelvraag 1: Welke aanvullende diagnostiek (een CT, MRI of herhaalde röntgenopnames na 10 dagen) heeft de voorkeur in het diagnosticeren van een scaphoïdfractuur bij patiënten waarbij geen fractuur kon worden vastgesteld op de initiële röntgenopnames (bij de eerste presentatie van klachten)?

De werkgroep heeft systematisch literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de diagnostische accuratesse van een CT/MRI binnen 10 dagen in vergelijking met het gebruik van herhaalde röntgenopnames na 10 dagen (scaphoïd series) om fracturen te detecteren in patiënten met acute scaphoïdfracturen na trauma aan de hand zonder zichtbare fractuur op de initiële opnames (scaphoïd series).

Er werden geen studies gevonden die de diagnostische accuratesse van scaphoïdfractuur door middel van röntgenopnames na 10 dagen rapporteerden. Daardoor kon de diagnostische accuratesse van röntgenopnames na 10 dagen niet vergeleken worden met een CT of MRI. De gerapporteerde resultaten voor diagnostische accuratesse van een CT versus MRI waren voor de meeste uitkomstparameters inconsistent, waardoor geen conclusies getrokken konden worden (zeer lage bewijskracht) over verschillen in de diagnostische accuratesse. Alleen ten aanzien van het aantal gerapporteerde vals positieven lijkt er geen verschil tussen het gebruik van een CT en MRI (lage bewijskracht). De bewijskracht voor deze vergelijking was laag vanwege brede betrouwbaarheidsintervallen. Er bestaat een kennislacune met betrekking tot het verschil in diagnostische accuratesse tussen verschillende modaliteiten.

Ondanks dat de literatuur geen uitsluitsel geeft, is de werkgroep van mening dat vroegtijdig aanvullende diagnostiek verrichten bij een klinische verdenking op een scaphoïdfractuur zinvol is. Uit de literatuur blijkt dat slechts bij 10-20% van patiënten met een klinische verdenking op een scaphoïdfractuur en negatieve initiële röntgenopnamen, sprake is van een werkelijke fractuur (Mallee, 2011; Mallee, 2015; Ring, 2008; Rhemrev, 2010). Dat komt dus neer op 7 uit 8 patiënten die worden overbehandeld met (gips)immobilisatie. Deze overbehandeling kan verminderd worden met het vervroegd uitvoeren van een CT of MRI en patiënten te ontslaan van behandeling bij afwezigheid van een fractuur op een CT of MRI. Gezien de duur tot herbeoordeling met aanvullende röntgenopnames tenminste 10 dagen is, levert eerdere aanvullende diagnostiek met een CT of MRI voor het overgrote deel van de patiënten zonder fractuur aanzienlijk minder lange immobilisatie en dus winst in minder ontwikkeling van stijfheid en vroegere werkhervatting. Daarnaast lijkt de sensitiviteit van herhaalde röntgenopnames (bepaald voor scaphoïd- en andere fracturen) slechts 52% (Breitenseher, 1997) en is er dus bij een persisterende klinische verdenking met negatieve röntgenopnames alsnog een indicatie voor aanvullende CT opnames. Het nut van initiële röntgenopnames bij presentatie van klachten blijft bestaan, met name om andere fracturen uit te sluiten.

Deelvraag 2: Welke aanvullende diagnostiek dient te worden uitgevoerd bij een scaphoïdfractuur die wordt vastgesteld op de initiële röntgenfoto’s?

De werkgroep van mening dat bij fracturen die wel worden gezien op initiële röntgenopnames het verrichten van een aanvullende CT ter beoordeling van de mate van dislocatie en comminutie in overweging genomen dient te worden. Consequenties van het missen van dislocatie >2mm, comminutie en proximale pool fracturen zijn met name malunion, nonunion en/of vroegtijdige artrose (Buijze, 2012; Temple, 2005; Gilley, 2018)

Occulte fracturen

De literatuur is niet eenduidig met betrekking tot verschillen tussen een CT en MRI voor wat betreft sensitiviteit bij het in kaart brengen van occulte fracturen (Mallee, 2015; de Zwart, 2016; Memarsadighi, 2006). Als er gekeken wordt naar mate van dislocatie, dan is dat op een CT beter te beoordelen onder andere omdat MRI scaphoïdcoupes op 2-3mm dikte worden ingesteld en daardoor dislocatie van <2mm niet goed beoordeeld kan worden. Daarmee is een CT niet alleen bruikbaarder als diagnosticum maar ook ter voorbereiding van eventueel chirurgische behandeling. Ook lijkt de klinische relevantie van op MRI zichtbare afwijkingen, die niet op een CT zichtbaar zijn (zoals beenmergoedeem) laag. Het geniet daarom de voorkeur om aanvullend voor een CT te kiezen boven MRI.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Patiënten hebben behoefte aan een goed afgestemde behandeling, waarbij onnodige immobilisatie wordt beperkt en zo snel mogelijk dagelijkse activiteiten kunnen worden hervat. Als vroegtijdige aanvullende beeldvorming meer duidelijkheid kan bieden zal de patiënt hier de voorkeur aan geven. Er is sprake van hogere expositie aan röntgenstraling bij het verrichten van een aanvullende CT scan. Deze mate van in Nederland gegeven straling voor een CT pols is echter zeer laag (overeenkomstig met 14 dagen natuurlijke achtergrondstraling) (Keller, 2022; Koivisto, 2017; Zwart, 2015). Bespreek dit ook zo met de patiënt. Dit zou volgens de werkgroep geen rol moeten spelen in de overweging om wel of geen CT te verrichten.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Het is mogelijk dat er aanvankelijk een hogere belasting en daarmee ook hogere kosten zullen ontstaan wanneer er meer CTs gemaakt worden. Het is echter onduidelijk in hoeverre de kosten toenemen als er vaker aanvullend een CT van de pols wordt verricht en daarmee ook minder herhaling van diagnostiek plaatsvindt. Daarnaast wordt in de huidige praktijk voor een gedeelte al een indicatie gezien voor een aanvullende CT van de pols bij een bewezen scaphoïdfractuur.

In de literatuur wordt beschreven dat het verrichten van vroegtijdige aanvullende diagnostiek qua directe totale ziekenhuiskosten lager uitvalt dan behandeling volgens conventionele poli controle met eventueel aanvullende röntgenopnames. Daarnaast kan de besparing van kosten van onnodige immobilisatie en duur tot volledige arbeidshervatting hoog oplopen. (Yin, 2015; Patel, 2013; Brooks, 2005).

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Het verrichten van meer aanvullende diagnostiek middels een CT of MRI levert hogere werkbelasting op voor de afdeling radiologie en daarbij is niet overal een CT laborant in huis buiten kantooruren. In dit kader is het aan te bevelen om aanvullende diagnostiek zo nodig in poliklinische setting te verrichten binnen enkele dagen.

De werkgroep is van mening dat er alleen een indicatie bestaat voor aanvullende CT van de pols (bij negatieve röntgenopnames) bij een sterke klinische verdenking. Mocht er in het acute moment twijfel over bestaan, of over de ervaring van de beoordelaar, kan er eveneens voor gekozen worden dit op korte termijn, doch binnen 5 dagen, poliklinisch te herbeoordelen.

De beschikbaarheid van de CT is in alle Nederlandse ziekenhuizen met een Spoedeisende Hulp gedekt binnen kantooruren. Voor wat betreft de MRI is de beschikbaarheid lager, ook qua planning en beschikbare laboranten. Daarnaast is de MRI niet voor alle patiënten geschikt (onder andere patiënten met ICD, metaalimplantaten) en duurt het onderzoek langer dan het verrichten van een CT scan. De beschikbaarheid van aanvullende diagnostiek is in Nederland gelijk verzekerd en zal geen effect hebben op de gezondheidsgelijkheid.

Rationale van aanbeveling-1: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de diagnostische procedure

De werkgroep is van mening dat bij een sterke klinische verdenking op een scaphoïdfractuur, zonder zichtbare fractuur op initiële röntgenopnames (waarbij ook andere fracturen zoals een distale radiusfractuur zijn uitgesloten), aanvullende diagnostiek middels een CT zinvol is. Onder een sterke klinische verdenking wordt verstaan een combinatie van een passend trauma en asdrukpijn over 1e straal, drukpijn tabatière anatomique (met name bij knijpkracht tussen dig 1 en 2) en drukpijn tuberculum volair. Bij twijfel over een al dan niet sterke klinische verdenking in het acute moment kan de patiënt op korte termijn, doch binnen 5 dagen, poliklinisch herbeoordeeld worden. Bij een persisterende klinische verdenking is aanvullende diagnostiek middels een CT zinvol.

Ondanks dat de literatuur niet eenduidig is over de meerwaarde van een CT boven herhaalde röntgenopnames (na 10-14 dagen) is wel bekend dat een vroege CT beduidend meer informatie verschaft dan de initiële röntgenopnames. Het versnelt daarmee het proces en vermindert onnodige immobilisatie. Tevens zal vroegtijdige aanvullende diagnostiek 1) leiden tot een beter afgestemde behandeling omdat de fractuur beter te beoordelen is op een CT, 2) de totale zorgkosten reduceren door besparing op het gebied van herhaalde polibezoeken en gipsverband behandeling en 3) vertraagde werkhervatting door immobilisatie voorkomen (Yin, 2015; Patel, 2013; Brooks, 2005). Naar mening van de werkgroep rechtvaardigt dit een sterke aanbeveling.

Het geniet de voorkeur aanvullend een CT te verrichten boven MRI. Dit omdat de mate van dislocatie en comminutie op een CT beter te beoordelen is. Ook is de landelijke beschikbaarheid van MRI minder hoog.

Daarnaast verwachten wij dat het juiste behandeltraject ten aanzien van chirurgisch ingrijpen bij een op aanvullende diagnostiek bewezen fractuur versneld ingezet kan worden.

Rationale van aanbeveling-2: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de diagnostische procedure

De werkgroep is van mening dat het de voorkeur geniet om aanvullend een CT te verrichten bij een bewezen scaphoïdfractuur om de mate van dislocatie en comminutie te beoordelen om zo een gericht behandelplan te kunnen maken.

Het missen van een gecompliceerde fractuur heeft risico’s op de lange termijn (te weten malunion, nonunion en/of vroegtijdige artrose) welke in een vroeg stadium mogelijk ondervangen kunnen worden.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Er is veel praktijkvariatie ten aanzien van de te gebruiken modaliteit voor het diagnosticeren van scaphoïdfracturen. Een klinische verdenking op een scaphoidfractuur bestaat uit een combinatie van een adequaat trauma (val op uitgestrekte hand, vaak sport gerelateerd, vaker bij mannen van jongere leeftijd) en een hoge klinische verdenking (asdrukpijn over 1e straal, drukpijn tabatière anatomique (met name bij knijpkracht tussen dig 1 en 2), drukpijn tuberculum volair). In dat geval bestaat er een indicatie voor röntgendiagnostiek. Bij twijfel (en negatieve röntgenopnamen) kan gekozen worden voor aanvullende diagnostiek of röntgenopnamen, eventueel een poliklinische herbeoordeling binnen enkele dagen door een specialist (orthopedie/ plastische chirurgie / chirurgie). In dat laatste geval is sprake van een persisterende klinische verdenking (met negatieve röntgenopnamen) op een scaphoïd fractuur.

In de huidige praktijk worden altijd initieel conventionele röntgenfoto’s van de pols gemaakt (ook om andere fracturen uit te sluiten). Deze 2-richtingen opnamen (postero-anterieur en lateraal) worden vaak nog aangevuld met een scaphoïdserie (semigeproneerde oblique opname en postero-anterieur met ulnaire deviatie). In sommige ziekenhuizen wordt bij een zichtbare scaphoïdfractuur altijd aanvullend een CT van de pols verricht.

Er bestaat een knelpunt over de te gebruiken modaliteit wanneer de initiële röntgenopnames geen fractuur laten zien, maar er wel een klinische verdenking op een scaphoïdfractuur bestaat. Circa 16-25% van de fracturen zijn niet zichtbaar op de initiële röntgenfoto’s (Beeres, 2008; Jenkins, 2008; Mallee, 2011). Men kiest dan vaak voor immobilisatie en klinische herbeoordeling na 5-14 dagen. Indien er dan nog een klinische verdenking op een fractuur bestaat, wordt vaak een röntgenopname herhaald of een aanvullende CT of MRI verricht. Indien patiënten klachtenvrij zijn wordt dit geduid als “geen fractuur” en wordt de behandeling beëindigd. In sommige centra wordt direct bij presentatie aanvullend een CT (of MRI) verricht en vervolgbeleid ingezet.

Het nut van herhalen van de foto na 10 dagen is discutabel. De literatuur is zeer tegenstrijdig in de meerwaarde van herhaalde röntgenopnames en rapporteert slechts 2% extra fracturen bij seriële opname (Leslie 1981, Munk 1995) tot zelfs 82% van occulte fracturen zichtbaar na 10 dagen en 100% zichtbaar na 38 dagen op seriële röntgenopnamen (Gabler 2001). Een CT of MRI is soms minder beschikbaar en geeft meestal meer informatie over aanwezigheid van een fractuur en eventuele dislocatie. De vraag rijst dan ook wat de beste timing zou zijn van aanvullende diagnostiek middels een CT of MRI. Bij het vroeg inzetten van een CT of MRI worden minder patiënten onnodig geïmmobiliseerd. Daarnaast wordt een eventuele operatie-indicatie eerder gesteld. Echter kan dit wel leiden tot overdiagnostiek en toename van kosten.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

False negatives, sensitivity and negative prediction value (crucial outcome measures)

CT versus radiography

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding whether the use of a CT within 10 days results in differences in false negatives, sensitivity and negative prediction values when compared to radiography in patients with suspected scaphoid fractures.

Sources: - |

MRI versus radiography

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding whether the use of a CT within 10 days results in differences in false negatives, sensitivity and negative prediction values when compared to radiography in patients with suspected scaphoid fractures.

Sources: - |

CT versus MRI

|

- GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the difference in the number of true negatives, sensitivity and negative prediction value using CT and MRI in patients with suspected scaphoid fractures.

Sources: Mallee, 2011; Memarsadeghi, 2006; De Zwart, 2016 |

False positive, true negatives, true positives, specificity and positives prediction value (important outcome measures)

CT versus radiography

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding whether the use of a CT within 10 days results in differences in false positive, true negatives, true positives, specificity and positive prediction value when compared to radiography after 10 days in patients with suspected scaphoid fractures.

Sources: - |

MRI versus radiography

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding whether the use of an MRI within 10 days results in differences in false positive, true negatives, true positives, specificity and positive prediction value when compared to radiography after 10 days in patients with suspected scaphoid fractures.

Sources: - |

CT versus MRI

|

Low GRADE |

The use of CT may result in little to no differences in the number of false positives compared to the use of MRI in patients with suspected scaphoid fractures.

Sources: Mallee, 2011; Memarsadeghi, 2006; De Zwart, 2016 |

CT versus MRI

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the difference in the number of false positives, true negatives, true positives, specificity and positive prediction value using CT and MRI in patients with suspected scaphoid fractures.

Sources: Mallee, 2011; Memarsadeghi, 2006; De Zwart, 2016 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

One systematic review (Krastman, 2020) and two additional studies (Breitenseher, 1997; Rua, 2019) were included in the analysis of the literature.

Krastman (2020) conducted a systematic review on the diagnostic accuracy of history taking and physical examination (pain, tenderness, compression, swelling) and imaging (radiographs, MRI, CT, bone scintigraphy, tomosynthesis) for phalangeal, metacarpal and carpal fractures (of which scaphoid fractures are the most frequent). Thirty-five studies that were published between 2000 up to 6 February 2019 were included. Out of these 35 studies, 8 were selected to answer the current question as only these studies fit the PICO.

The selected studies were prospective cohorts that investigated the diagnostic accuracy of CT and/or MRI with regard to the diagnosis of scaphoid fractures in patients with a suspected scaphoid fracture that was not visible on the initial radiographs. The prevalence of true scaphoid fractures ranged between 9 to 45%. Different reference standards were used, including radiography after 6 weeks or a combination of MRI, CT and BS and clinical follow-up information. Relevant characteristics per study are shown in table 2. There may be risk of bias because of blinding during measurements of the reference standard was unclear in some of the studies.

Breitensheher (1997) conducted a prospective cohort study of to evaluate the diagnostic value of MRI in forty-two patients with clinical suspicion of scaphoid fractures and normal initial plain radiographs. Most participants were male (23 versus 19 females) with a mean age of 30.5 years. The prevalence of true scaphoid fractures was 33.3%. MRI’s were evaluated independently by two radiologists. Six-week follow-up radiographs were used as a reference standard to diagnose fractures, see characteristics in table 2. There was no risk of bias.

Rua (2019) conducted the Scaphoid Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Trauma (SMaRT) trial was, and RCT, to evaluate the clinical and cost implications of using immediate MRI in the acute management of patients with a suspected fracture of the scaphoid with negative radiographs. Patients who presented to the emergency department (ED) with a suspected fracture of the scaphoid and negative radiographs were randomized to a control group, who did not undergo further imaging in the ED, or an intervention group, who had an MRI of the wrist as an additional test during the initial ED attendance. Most participants were male (52% control, 61% intervention), with a mean age of 36.2 years in the control group and 38.2 years in the intervention group, see characteristics in table 2. The prevalence of true scaphoid fractures was 8.3%. There may be risk of bias as blinding of the care team staff was a study limitation.

Table 2 – study characteristics

|

First author, year |

Study design |

Population |

Patient characteristics: N, mean age, sex(M/F) |

Index test: CT/MRI/ radiographs (timing) |

Reference standard (timing) |

Prevalence scaphoid fractures in total study population |

|

Studies included in Krastman, 2020 |

||||||

|

Beeres, 2008 |

Prospective cohort |

Patients with clinically-suspected scaphoid fracture, but initial radiographs showed no evidence of a fracture |

100, 42 years, 50/50 |

|

|

20/100 (20%) |

|

Breederveld, 2004 |

Prospective cohort |

Patients with suspected scaphoid fracture but no fracture was visible on the radiographic plate (anteroposterior, and indirect and scaphoid series); who were re-examined at the outpatient department after 5-10 days |

29, NR, NR |

|

|

9/29 (31.0%) |

|

Mallee, 2011 |

Prospective cohort |

Patients with a suspected scaphoid fracture (tenderness of the scaphoid and normal radiographic findings after a fall on the outstretched hand) |

34, NR, 25/15 |

|

Radiographs (6 weeks after initial injury) |

6/34 (17.6%) |

|

Memarsadeghi, 2006 |

Prospective cohort |

Patients clinically suspected of having a scaphoid fracture and who had normal initial radiographs |

29, 34 years, 17/12 |

|

Radiographs (6 weeks after trauma) |

11/29 (37.9%) |

|

Rhemrev, 2010 |

Prospective cohort |

Patients with a clinically suspected scaphoid fracture and no fracture on scaphoid radiographs |

100, 40.8 years, 51/49 |

|

|

14/100 (14%) |

|

De Zwart, 2016 |

Prospective (consecutive) cohort |

Patients with a clinically suspected scaphoid fracture without a fracture on the initial scaphoid radiographs (< 48 hours after trauma) |

33, 39 years, 16/17 |

|

|

3/33 (9%) |

|

Additional studies |

||||||

|

Breitenseher, 1997 |

Prospective cohort |

Patients who presented to the clinic for trauma surgery with clinical suspicion of scaphoid fracture after acute wrist injury; in whom two initial and four subsequent plain radiographs of the wrist failed to demonstrate a fracture |

42, 30.5 years, 23/19 |

|

Radiographs (6 weeks after trauma) |

14/42 (33.3%) |

|

Rua, 2019 |

RCT |

Patients with a suspected fracture of the scaphoid with negative radiographs; randomized to a control group [radiographs only in the emergency department and repeated radiographs after 1 to 2 weeks; a proportion will undergo CT] or intervention group [additional immediate short-sequence MRI while in the emergency department]

Only intervention group is included as the control group does not fit our PICO. |

Intervention group: 67, 38.2 years, 41/26

|

|

Radiographs (three months study follow-up)

|

7/67 (10.4%) |

BS = bone scintigraphy; NR = not reported; RCT = randomized controlled trail

Results

False negatives, sensitivity and negative prediction value (crucial outcome measures)

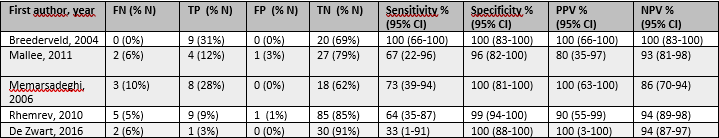

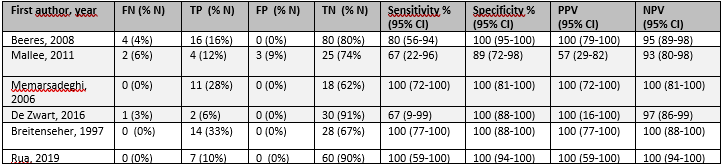

Six studies (Breederveld, 2004; Mallee, 2011; Memarsadeghi, 2006; Rhemrev, 2001; De Zwart, 2016) reported the number of false negatives (FN), sensitivity and/or negative prediction values (NPV) for CT, six studies (Beeres, 2008; Breitenseher, 1997; Mallee, 2011; Memarsadeghi, 2006; Rua, 2019; De Zwart, 2016) reported these values for MRI and no studies reported outcome measures for radiography. As diagnostic accuracy of radiographs after 10 days was not reported, diagnostic accuracy of CT and MRI could not be compared with radiography. The results for CT and MRI are summarized in tables 3 and 4.

CT

The percentage of FN varied from 0 to 10%, the sensitivity for CT varied from 33 to 100% and the NPV for CT varied from 86 to 100%.

MRI

The percentage of FN varied from 0 to 6%; sensitivity varied from 67 to 100%; and NPV varied from 93 to 100%.

CT versus MRI

Mallee (2011), Memarsadeghi (2006) and De Zwart (2016) compared FN, sensitivity and NPV of CT and MRI within a population. The results of these comparisons will be graded. Reported results of these studies were inconsistent: FN and NPV did not differ clinically relevant between CT and MRI in Mallee (2011) and De Zwart (2016), but FN was clinically relevant larger and NPV clinically relevant lower for CT in Memarsadeghi (2006). Sensitivity did not differ clinically relevant between CT and MRI in Mallee (2011), but was clinically relevant lower for CT in Memarsadeghi (2006) en De Zwart (2016).

False positive, true negatives, true positives, specificity and positives prediction value (important outcome measures)

Six studies (Breederveld, 2004; Mallee, 2011; Memarsadeghi, 2006; Rhemrev, 2001; De Zwart, 2016) reported the number of false positives (FP), true negatives (TN), true positives (TP), specificity and/or positive prediction values (PPV) for CT, six studies (Beeres, 2008; Breitenseher, 1997; Mallee, 2011; Memarsadeghi, 2006; Rua, 2019; De Zwart, 2016) reported these values for MRI and no studies reported outcome measures for radiography. As diagnostic accuracy of radiographs after 10 days was not reported, diagnostic accuracy of CT and MRI could not be compared with radiography. The results are summarized in tables 3 and 4.

CT

The percentage FP rate varied from 0 to 3%, percentage of TN varied from 62 to 91%, percentage of TP varied from 3 to 31%, specificity varied from 96 to 100% and PPV varied from 80 to 100%.

MRI

The percentage FP rate varied from 0 to 6%; percentage of TN varied from 62 to 91%, percentage of TP varied from 6 to 33%, specificity varied from 89 to 100%; and PPV varied from 57 to 100%.

CT versus MRI

Mallee (2011), Memarsadeghi (2006) and De Zwart (2016) compared FP, TN, TP, specificity and PPV of CT and MRI within a population. The results of these comparisons will be graded.

No clinically relevant differences were reported for TP. For other outcomes, reported results were inconsistent: FP was clinically relevant lower in CT compared to MRI and TN, specificity and PPV were clinically relevant higher in CT compared to MRI in Mallee (2011), but no clinically relevant differences were reported in Memarsadeghi (2006) and De Zwart (2016).

Table 3 – diagnostic accuracy CT

CI = confidence interval; FN = false negatives; FP = false positives; NPV = negative prediction value; NR = not reported; TN = true negatives; TP = true positives; PPV = positive prediction value

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV are calculated by MedCalc Software Ltd with thr exception of De Zwart (2016)

Table 4 – diagnostic accuracy MRI

CI = confidence interval; FN = false negatives; FP = false positives; NPV = negative prediction value; NR = not reported; TN = true negatives; TP = true positives; PPV = positive prediction value

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV are calculated by MedCalc Software Ltd with the exception of De Zwart (2016)

Level of evidence of the literature

False negatives, sensitivity and negative prediction value (crucial outcome measures)

CT versus radiography

The level of evidence regarding false negatives, sensitivity and negative predictive value could not be determined as no data between CT and radiography could be compared.

MRI versus radiography

The level of evidence regarding false negatives, sensitivity and negative predictive value could not be determined as no data between MRI and radiography could be compared.

CT versus MRI

The level of evidence regarding false negatives, sensitivity and negative predictive value started at high and was downgraded to very low because of inconsistent results (-1, inconsistency) and very wide confidence intervals (-2, imprecision).

False positives, true negatives, true positives, specificity and positive prediction value (important outcome measures)

CT versus radiography

The level of evidence regarding false positives, true negatives, true positives, specificity and positive prediction value could not be determined as no data between CT and radiography could be compared.

MRI versus radiography

The level of evidence regarding false positives, true negatives, true positives, specificity and positive prediction value could not be determined as no data between MRI and radiography could be compared.

CT versus MRI

The level of evidence regarding false positives started at high and was downgraded to low because of wide confidence intervals (-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding false positive, true negatives, true positives, specificity and positive prediction value started at high and was downgraded to very low because of inconsistent results (-1, inconsistency) and very wide confidence intervals (-2, imprecision).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the diagnostic accuracy of CT or MRI immediately or after 10 days vs. radiographs after 10 days to diagnose scaphoid fractures in patients with suspected scaphoid fracture (not proven on initial radiographs)?

| P: | Adult patients (>18 years) with clinical suspicion of acute scaphoid fracture after trauma to the hand, but no visible fracture on initial radiographs (2-way and/or scaphoid series, day 1) |

| I: | Index test: CT/MRI within 10 days after trauma |

| C: | Comparator test: Radiographs (scaphoid series) |

| R: | Reference standard: Radiographs after 6 weeks or a combination of imaging modalities (MRI, CT, bone scintigraphy (BS)) and/or clinical follow-up |

| O: | Outcome measures: diagnostic accuracy: false negatives (FN), sensitivity, negative prediction value (NPV), false positives (FP), true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), specificity, positive prediction value (PPV) |

| T/S: | initial presentation of complaints, emergency department |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered FN, sensitivity and NPV as critical outcome measures for decision making and FP, TN, TP, specificity and PPV as important outcome measures for decision making (table 1).

Table 1 Consequences of diagnostic test characteristics

|

Outcome |

Consequences |

Relevance |

|

True positives (TP), high sensitivity, high postitive prediction value |

Patients are justifiably diagnosed with scaphoid fracture; giving treatment is justified |

Important |

|

True negatives (TN), high specificity, high negative prediction value |

Patients are justifiably not diagnosed with scaphoid fracture; not giving treatment is justified |

Important |

|

False positives (FP), low specificity, low positive prediction value |

Patients are unjustifiably diagnosed with scaphoid fracture; giving treatment is unjustified |

Important |

|

False negatives (FN), low sensitivity, low negative prediction value |

Patients are unjustifiably not diagnosed with scaphoid fracture; not giving treatment is unjustified |

Crucial |

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined a difference of 5% in sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) and a difference of 50 per 1000 patients in TP, TN, FP and FN as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 28 February 2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 482 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic reviews, RCTs or observational studies;

- Studies included patients who were 18 years or older with clinical suspicion of acute scaphoid fracture after trauma to the hand but no visible fracture on initial radiographs at the time of initial presentation of complaints/ at the emergency department;

- The index/control test was CT and/or MRI within 10 days after trauma or radiography after 10 days after trauma;

- The reference standard consisted of radiographs after 6 weeks or a combination of imaging modalities (MRI, CT and BS) and/or clinical follow-up;

- At least one of the diagnostic accuracy outcome measures FN, sensitivity, NPV, FP, TN, TP, specificity, PPV was reported.

Thirty-four studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. Based on screening references of systematic reviews, 19 studies were added to the initial selection. After reading the full text, 50 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 3 studies were included.

Results

In total, three studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Beeres FJ, Rhemrev SJ, den Hollander P, Kingma LM, Meylaerts SA, le Cessie S, Bartlema KA, Hamming JF, Hogervorst M. Early magnetic resonance imaging compared with bone scintigraphy in suspected scaphoid fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008 Sep;90(9):1205-9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B9.20341. PMID: 18757961.

- Breitenseher MJ, Metz VM, Gilula LA, Gaebler C, Kukla C, Fleischmann D, Imhof H, Trattnig S. Radiographically occult scaphoid fractures: value of MR imaging in detection. Radiology. 1997 Apr;203(1):245-50. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.1.9122402. PMID: 9122402.

- Brooks S, Wluka AE, Stuckey S, Cicuttini F. The management of scaphoid fractures. J Sci Med Sport. 2005 Jun;8(2):181-9. doi: 10.1016/s1440-2440(05)80009-x. PMID: 16075778.

- Buijze GA, Ochtman L, Ring D. Management of scaphoid nonunion. J Hand Surg Am. 2012 May;37(5):1095-100; quiz 1101. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.03.002. PMID: 22541157.

- Gäbler C, Kukla C, Breitenseher MJ, Trattnig S, Vécsei V. Diagnosis of occult scaphoid fractures and other wrist injuries. Are repeated clinical examinations and plain radiographs still state of the art? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2001 Mar;386(2):150-4. doi: 10.1007/s004230000195. PMID: 11374049.

- Gilley E, Puri SK, Hearns KA, Weiland AJ, Carlson MG. Importance of Computed Tomography in Determining Displacement in Scaphoid Fractures. J Wrist Surg. 2018 Feb;7(1):38-42. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1604136. Epub 2017 Jul 6. PMID: 29383274; PMCID: PMC5788756.

- Jenkins PJ, Slade K, Huntley JS, Robinson CM. A comparative analysis of the accuracy, diagnostic uncertainty and cost of imaging modalities in suspected scaphoid fractures. Injury. 2008 Jul;39(7):768-74. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.01.003. Epub 2008 Jun 9. PMID: 18541243.

- Keller G, Hagen F, Neubauer L, Rachunek K, Springer F, Kraus MS. Ultra-low dose CT for scaphoid fracture detection-a simulational approach to quantify the capability of radiation exposure reduction without diagnostic limitation. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2022 Sep;12(9):4622-4632. doi: 10.21037/qims-21-1196. PMID: 36060581; PMCID: PMC9403576.

- Koivisto J, van Eijnatten M, Kiljunen T, Shi XQ, Wolff J. Effective Radiation Dose in the Wrist Resulting from a Radiographic Device, Two CBCT Devices and One MSCT Device: A Comparative Study. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2018 Apr 1;179(1):58-68. doi: 10.1093/rpd/ncx210. PMID: 29040707.

- Krastman P, Mathijssen NM, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Kraan G, Runhaar J. Diagnostic accuracy of history taking, physical examination and imaging for phalangeal, metacarpal and carpal fractures: a systematic review update. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020 Jan 7;21(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2988-z. PMID: 31910838; PMCID: PMC6947988.

- Leslie IJ, Dickson RA. The fractured carpal scaphoid. Natural history and factors influencing outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981 Aug;63-B(2):225-30. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.63B2.7217146. PMID: 7217146.

- Mallee W, Doornberg JN, Ring D, van Dijk CN, Maas M, Goslings JC. Comparison of CT and MRI for diagnosis of suspected scaphoid fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011 Jan 5;93(1):20-8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01523. PMID: 21209265.

- Mallee WH, Wang J, Poolman RW, Kloen P, Maas M, de Vet HC, Doornberg JN. Computed tomography versus magnetic resonance imaging versus bone scintigraphy for clinically suspected scaphoid fractures in patients with negative plain radiographs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jun 5;2015(6):CD010023. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010023.pub2. PMID: 26045406; PMCID: PMC6464799.

- Memarsadeghi M, Breitenseher MJ, Schaefer-Prokop C, Weber M, Aldrian S, Gäbler C, Prokop M. Occult scaphoid fractures: comparison of multidetector CT and MR imaging--initial experience. Radiology. 2006 Jul;240(1):169-76. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2401050412. Erratum in: Radiology. 2007 Mar;242(3):950. PMID: 16793977.

- Munk B, Frøkjaer J, Larsen CF, Johannsen HG, Rasmussen LL, Edal A, Rasmussen LD. Diagnosis of scaphoid fractures. A prospective multicenter study of 1,052 patients with 160 fractures. Acta Orthop Scand. 1995 Aug;66(4):359-60. doi: 10.3109/17453679508995561. PMID: 7676826.

- Patel NK, Davies N, Mirza Z, Watson M. Cost and clinical effectiveness of MRI in occult scaphoid fractures: a randomised controlled trial. Emerg Med J. 2013 Mar;30(3):202-7. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2011-200676. Epub 2012 Apr 13. PMID: 22505295.

- Rhemrev SJ, de Zwart AD, Kingma LM, Meylaerts SA, Arndt JW, Schipper IB, Beeres FJ. Early computed tomography compared with bone scintigraphy in suspected scaphoid fractures. Clin Nucl Med. 2010 Dec;35(12):931-4. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181f9de26. PMID: 21206223.

- Ring D, Lozano-Calderón S. Imaging for suspected scaphoid fracture. J Hand Surg Am. 2008 Jul-Aug;33(6):954-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.04.016. PMID: 18656772.

- Rua T, Malhotra B, Vijayanathan S, Hunter L, Peacock J, Shearer J, Goh V, McCrone P, Gidwani S. Clinical and cost implications of using immediate MRI in the management of patients with a suspected scaphoid fracture and negative radiographs results from the SMaRT trial. Bone Joint J. 2019 Aug;101-B(8):984-994. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.101B8.BJJ-2018-1590.R1. PMID: 31362557; PMCID: PMC6681676.

- Temple CL, Ross DC, Bennett JD, Garvin GJ, King GJ, Faber KJ. Comparison of sagittal computed tomography and plain film radiography in a scaphoid fracture model. J Hand Surg Am. 2005 May;30(3):534-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.01.001. PMID: 15925164.

- Yin ZG, Zhang JB, Gong KT. Cost-Effectiveness of Diagnostic Strategies for Suspected Scaphoid Fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2015 Aug;29(8):e245-52. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000316. PMID: 25756914.

- de Zwart AD, Beeres FJ, Rhemrev SJ, Bartlema K, Schipper IB. Comparison of MRI, CT and bone scintigraphy for suspected scaphoid fractures. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2016 Dec;42(6):725-731. doi: 10.1007/s00068-015-0594-9. Epub 2015 Nov 10. PMID: 26555729.

- Zwart, Andele & Beeres, Frank & Pillay, Mike & Kingma, Lucas & Schipper, Inger & Rhemrev, Steven. (2015). Radiation Exposure due to CT of the Scaphoid in Daily Practice. JNMRT. 6. 10.4172/2155-9619.1000233.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy studies

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics

|

Index test (test of interest) |

Reference test

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Krastman, 2020

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise)

** = additional data extracted from individual studies

NR= Not reported |

SR Literature search up to 6 February 2019.

A: Beeres, 2008 B: Breederveld, 2004 C: Mallee, 2011 D: Memarsadeghi, 2006 E: Rhemrev, 2010 F: De Zwart, 2016

Study design: A: Prospective cohort B: Prospective cohort C: Prospective cohort D: Prospective cohort E: Prospective cohort F: Prospective cohort

Setting and Country: A: Emergency department (Netherlands) B: Emergency department (Netherlands) C: Initially emergency physicians and in follow-up by the Orthopedic department and/or Trauma surgery department, depending on who was on call. (Netherlands) D: Not described (Austria) E: Emergency department (Netherlands) F: Emergency department (Netherlands)

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: SR: Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding No funding.

RCTs**: A: No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article. B: NR C: Disclosure: In support of their research for or preparation of this work, one or more of the authors received, in any one year, outside funding or grants of less than $10,000 from the Marti-Keuning-Eckhardt Foundation. One or more of the authors, or a member of his or her immediate family, received, in any one year, payments or other benefits in excess of $10,000 or a commitment or agreement to provide such benefits from commercial entities (Stryker, Wright Medical, Tornier, Acumed, Biomet, Joint Active Systems, Gerson Lehrman Group, MEDACorp, Skeletal Dynamics, IlluminOss Medical, MiMedx Group, AO North America, and AO International). D: NR E: NR F: Conflict of interest Andele D. de Zwart, Frank J.P. Beeres, MD, PhD, Steven J. Rhemrev, Kees Bartlema and Inger B. Schipper declare that they have no conflict of interest. |

Inclusion criteria SR: Studies describing diagnostic accuracy of history taking, physical examination or imaging in adult patients (age ≥16 years) with phalangeal, metacarpal and/or carpal fractures were included. No language restriction was applied.

Exclusion criteria SR: Case reports, reviews and conference proceedings were excluded. Distal radius and ulna injuries were also excluded, as they can be diagnosed accurately with plane X-ray or computer tomography imaging.

35 studies included*

Important patient characteristics:

N, mean age (years) ±SD **: A: 100, 42 (range 18 to 84) B: 29, NR C: 34, NR D: 29, 34±13 E: 100, 40.8 (range, 17–88) F: 33, 39 (range 18–73)

Sex (M/F)**: A: 50/50 B: NR C: 25/15 D: 17/12 E: 51/49 F: 16/17

|

Index test CT/MRI, comparator radiographs after 10 days**: A: MRI 1.5 T within 24 hours after initial presentation to the Accident and Emergency Department. B: CT within 0 to 4 days, 1-mm slices C: CT within 10 days, 0.5-mm slice section thickness and MRI 1.0 T within 10 days D: MDCT¹ 0.5 mm section thickness, MRI 1,0 T, both on the same day, 1–6 days after the initial trauma (mean, 4.1 days) E: MDCT, slice thickness 0.625 mm (< 24 h) F: MRI 1.5T (< 72 h), CT, slice thickness 0.5 mm (<72 h)

¹ MDCT = Multidetector-CT |

A: If MRI and bone scintigraphy both showed a fracture, the final diagnosis was: fracture. If MRI and bone scintigraphy both showed no fracture, the final diagnosis was: no fracture. Where there was a discrepancy between MRI and bone scintigraphy, plain radiographs (six weeks after injury) and physical examination during follow-up were used to make the final diagnosis. If any clinical sign remained abnormal after two weeks (tenderness in the anatomical snuffbox or pain when applying axial pressure to the thumb or index finger) and/or there was radiological evidence of a fracture six weeks after injury, the final diagnosis was: fracture. If there were no clinical signs after two weeks (no tenderness or pain in the snuffbox when applying axial pressure to the thumb or index finger) or no radiological evidence of a fracture six weeks after injury, the final diagnosis was: no fracture. B: If both the CT scan and the bone scintigram were negative for a fracture of the scaphoid bone, and provided that no other injury could be found, the patients were discharged from treatment. After 8 to 16 months, they were approached and asked about the presence of any wrist complaint. When the patient showed no clinical signs, the patient was considered to be negative for a scaphoid fracture. If the bone scintigram was negative and the CT scan was positive, a reassessment of the bone scintigram was requested, the patient received conservative treatment, and the CT scan was repeated after 6 weeks. When this CT scan showed signs of consolidation of a fracture, the patient was considered to be positive for a scaphoid fracture. If the bone scintigram was positive and the CT scan was negative, the patient received no further treatment, the bone scintigram was reassessed, and the CT scan was repeated after 6 weeks. When this CT scan was negative again, the patient was considered to be negative for a scaphoid fracture. If both bone scintigram and CT scan were positive, the patient was treated and a control CT scan was obtained after treatment. When the control CT scan showed consolidation of a fracture, the patient was considered to be positive for a scaphoid fracture. C: Radiographs, after 6 weeks follow-up. D: Radiographs obtained 6 weeks after trauma. View: posteroanterior with the wrist in neutral position, lateral, semipronated oblique scaphoid, and radial oblique scaphoid. E: Final diagnosis after final discharge, according to the following standard: If CT and bone scintigraphy showed a fracture, the final diagnosis was fracture. If CT and bone scintigraphy showed no fracture, the final diagnosis was no fracture. In case of discrepancy between CT and bone scintigraphy, both radiographic (6 weeks after injury) and physical reevaluation during follow-up were used to make a final diagnosis. In case of radiographic evidence of a scaphoid fracture 6 weeks after injury, the final diagnosis was fracture. In case of no radiographic evidence of a scaphoid fracture 6 weeks after injury but there were persistent clinical signs of a scaphoid fracture after 2 weeks, the final diagnosis was fracture. If there was no radiographic evidence of a scaphoid fracture 6 weeks after injury and there were no longer clinical signs of a scaphoid fractures throughout follow-up, the final diagnosis was no fracture. F: If MRI, CT and BS all showed a fracture, the final diagnosis was: fracture. If MRI, CT and BS all showed no fracture, the final diagnosis was: no fracture. In case of discrepancy between MRI, CT and BS, the final diagnosis was established based on specific clinical signs of a fracture after 6 weeks (tender anatomic snuffbox and pain in the snuffbox when applying axial pressure on the first or second digit) combined with the radiographic evidence of a fracture after 6 weeks. If these signs were absent and no radiographic evidence, the final diagnosis was: no fracture.

Prevalence (%)** A: 20 (20%) B: 9 (31%) C: 6/34 (17.6%) D: 11 (38%) E: 14 (14%) F: 3 (9.1%)

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available?** A: 0 B: 0 C: Thirty-four patients returned for follow-up radiographs at approximately seven weeks after the injury (average, forty-eight days; range, thirty-five to seventy-four days) and five did not. D: 0 E: 30 F: 1

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described?** A: N/A B:N/A C: One patient was a tourist at the time of injury and was no longer in the area, three patients were lost to follow-up, and one withdrew from the study. One patient was excluded because of inadequate image quality due to a motion artifact. D: N/A E: Of total, 30 patients did not have both CT and bone scintigraphy, due to withdrawal of participation. F: One patient was excluded as no CT was made. |

Endpoint of follow-up:** A: Six months: “This is supported by the finding that no symptomatic pseudarthrosis occurred within the six-month follow-up period.” B: 1 year C: follow-up radiographs at approximately seven weeks after the injury (average, forty-eight days; range, thirty-five to seventy-four days) D: final diagnosis after 6 weeks E: 6 months after injury F: Not explicitly reported, but probably until reference standard: radiographs after 6 weeks. |

Diagnostic accuracy** FN: false negatives TP: true positives FP: false positives TN: true negatives Sensitivity % (95% CI) Specificity % (95% CI) PPV: positive predictive value % (95% CI) NPV: negative predictive value % (95% CI)

A: MRI FN: 4 TP: 16 FP: 0 TN: 80 Sensitivity: 80 (56-94) Specificity: 100 (96-100) PPV: 100 (74-100) NPV: 95 (88-99)

B: CT FN: 0 TP: 9 FP: 0 TN: 20 Sensitivity: 100 Specificity: 100 PPV: 100 NPV: 100

C: CT: FN: 2 TP: 4 FP: 1 TN: 27 Sensitivity: 67 (35-88) Specificity: 96 (85-99) PPV: 80 (NR) NPV: 93 (NR) Accounting for prevalence and incidence PPV: 76 (43-95) NPV: 94 (81-98)

MRI: FN: 2 TP: 4 FP: 3 TN: 25 Sensitivity: 67 (35-88) Specificity: 89 (76-96) PPV: 57 (NR) NPV: 93 (NR) Accounting for prevalence and incidence PPV: 54 (29-81) NPV: 93 (80-98)

D: CT: FN: 3 TP: 8 FP: 0 TN: 18 Sensitivity: 73 (48-89) Specificity: 100 (87-100) PPV: 100 NPV:86

MRI: FN: 0 TP: 11 FP: 0 TN: 18 Sensitivity: 100 (82-100) Specificity: 100 (87-100) PPV: 100 NPV: 100

E: CT FN: 5 TP: 9 FP: 1 TN: 85 Sensitivity: 64 (39-89) Specificity: 99 (93-100) PPV: 90 (71-100) NPV: 94 (88-98)

F: CT: FN: 2 TP: 1 FP: 0 TN: 30 Sensitivity: 33 Specificity: 100 (88-100) PPV: 100 NPV: 94

MRI: FN: 1 TP: 2 FP: 0 TN: 30 Sensitivity: 67 Specificity: 100 (88-100) PPV: 67 (probably typing error in Krastman 2020) NPV: 97 |

Studies not included in current analysis of the literature as sstudies did not met PICRO:

Adey (2007) Annamalai (2003) Behzadi (2015) Beeres (2007) Cruickshank (2007) Fusetti (2005) Gabler (2001) Herneth (2001) Ilica (2011) Kumar (2005) Mallee (2016) Mallee (2014) (same participants as 2011) Ottenin (2012) Platon (2011) Rhemrev (2010) Steenvoorde (2006) Yildrim (2013) Sharifi (2015) Brink (2014) Neubauer (2018) Borel (2017) Balci (2015) Jorgsholm (2013) Nikken (2005) Javadzadeh (2014) Faccioli (2010) Kocaolglu (2016) Tayal (2007)

Study quality (ROB): Methodological quality was assessed by two independent reviewers, using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) checklist.

Risk of Bias Patient Selection, Index Test, Reference standard, Flow and Timing; Applicability Concerns Patient Selection, Index Test Reference standard (LR Low Risk, HR High Risk, UR Unclear Risk)

A: LR, LR, LR, LR; LR, LR, LR B: LR, UR, UR, LR; LR, LR, LR C: LR, LR, LR, LR; LR, LR, LR D: UR, LR, LR, LR; LR, LR, LR E: LR, LR, HR, LR; LR, LR, LR F: LR, LR, HR, LR; LR, LR, LR

The reasons for concerns (UR, HR) were not described in detail: “In 13 of the 35 studies [43, 44, 48, 50, 54, 55, 59, 64, 67, 72, 74, 76, 77], patient selection was not well documented. Furthermore, the risk of bias was predominantly due to the absence of a proper description of the index test (9/ 35) [43, 45, 49, 53, 55, 64, 65, 72, 77] or the reference standard (13/35) [45, 49, 55, 62, 64–68, 71–73, 75].”

Place of the index test in the clinical pathway: replacement

Author’s conclusion: As no studies in non-institutionalized general practitioner care were identified, general practitioners who examine patients with a suspected hand or wrist fracture have limited instruments for providing adequate diagnostics. A general practitioner could decide to refer such patients to a hospital for specialized care, but one could question what assessments a specialist can use to come to an accurate diagnosis. In hospital care, two studies of the diagnostic accuracy of history taking for phalangeal, metacarpal and carpal fractures were found and physical examination was of moderate use for diagnosing a scaphoid fracture and of limited use for diagnosing phalangeal, metacarpal and remaining carpal fractures. Based on the best evidence synthesis, imaging tests (conventional radiograph, MRI, CT and BS) were only found to be moderately accurate for definitive diagnosis in hospital care.

|

Evidence table for diagnostic test accuracy studies

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics

|

Index test (test of interest) |

Reference test

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Breitenseher, 1997 |

Type of study: prospective cohort

Setting and country: Clinic for trauma surgery, Vienna, Austria

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported. |

Inclusion criteria: presentation to the ED after acute trauma. Clinically suspected for scaphoid fracture: pain, swelling and tenderness of ASB during evaluation in the ED. No fracture on initial radiographs in 6 views (AP, 2 x Lat, PA with ulnar deviation, 2 x oblique)

Exclusion criteria: fracture on initial radiographs

N= 42

Prevalence: 33% (14/42)

Mean age ± SD: 30.5 ± 13.8

Sex: 23 men and 19 women

|

Index test: MRI 1.0T within 7 days after trauma (mean 3.8 days)

Radiographs 2 weeks after trauma |

6-week follow-up radiographs compared with initial radiographs

|

Time between the index test and reference test: 5-6 weeks, MRI within 7 days and radiographs 6 weeks after trauma

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? 0

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

MRI: TP: 14 FP: 0 FN: 0 TN: 28

Sensitivity: NR for scaphoid fractures Specificity: NR for scaphoid fractures Positive prediction value: NR Negative prediction value: NR

Radiographs after 2 weeks: TP: NR FP: NR FN: NR TN: NR

Sensitivity: NR (not reported for scapoidfractures alone) Specificity: NR Positive prediction value: NR Negative prediction value: NR

|

Author’s conclusion: In cases of clinically suspected, radiographically occult scaphoid fracture, MR imaging offers a high sensitivity as the second diagnostic procedure in detection of radiographically occult fractures of the scaphoid and other wrist bones. MR imaging enables early diagnosis and initiation of early treatment of occult fractures, as well as prevention of overtreatment (several weeks of unnecessary immobilization) in patients without a fracture. The best diagnostic strategy in the management of clinically suspected scaphoid fractures consists of initial radiography followed by MR imaging rather than repeat radiography in patients with negative initial radiographs. |

|

Rua, 2019 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: ED at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in London, UK

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funding statement: No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

ICMJE COI statement: V. Goh declares an institutional grant from Siemens Healthineer not related to this study. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N (intervention group / control group)= 67/65

Prevalence: I: 7 (10.4%) C: 4 (6.2%)

Mean age (range): I: 38.2 (20-71) years C: 36.2 (18-73) years

Sex: male:female I: 41:26 C: 34:31 |

Intervention group: immediate short-sequence MRI while in the Emergency Department (ED)

Control group: radiographs only in the ED, repeat conventional radiography after 1 to 2 weeks (a proportion wil undergo CT) |

Reference test: the three-month series of scaphoid radiographs

|

Time between the index test and reference test: 3 months (three-month series of radiographs) after immediate MRI

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Intervention group: N=68 allocated N=5 did not receive the allocated intervention. Reasons: event of unforeseen claustrophobia (n=2), MRI not available within 1hr (n=1), MRI not working (n=1), cochlear implant not mentioned during initial screening (n=1).

N=1 lost to follow-up: patient withdrew consent.

Analyzed: N=67

Control group: N=68 allocated. N=3 lost to follow-up: patient withdrew consent

Analyzed N=65

|

MRI group (N=65): TN: 60 TP: 7 FN: 0 FP: 0 Sensitivity: NR Specificity: NR Positive prediction value: NR Negative prediction value: NR

Control group (N=65): TN: 61 TP: 0 FN: NR FP: NR Sensitivity: NR Specificity: NR Positive prediction value: NR Negative prediction value: NR

|

Authors’ conclusion: In conclusion, the SMaRT trial has addressed a gap in the clinical and economic evidence, with implications for clinical practice and research. The results showed that the immediate use of MRI in the management of a scaphoid fracture was associated with a trend towards reduced costs at three months (although not statistically significant), and a significant decrease in total costs at six months post-recruitment. Furthermore, the intervention led to a quicker diagnosis, improved diagnostic accuracy, and higher patient satisfaction. In summary, the use of immediate MRI in the ED should be considered as an additional test in the management of suspected scaphoid fractures in the NHS. |

Risk of bias assessment diagnostic accuracy studies (QUADAS II, 2011)

|

Study reference |

Patient selection

|

Index test |

Reference standard |

Flow and timing |

Comments with respect to applicability |

|

Beeres, 2008 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes “100 consecutive patients who attended the Accident and Emergency Department with a suspected scaphoid fracture were included in the study”

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes “Polytrauma patients, patients under the age of 18 years, and those in whom MRI was contraindicated were excluded.” |

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes “observers filled in a standard form, blind to each other and blind to any other data”

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Not applicable

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Probably yes (reference standard matches PICO)

A final diagnosis was made after final discharge according to the following reference standard.

Where there was a discrepancy between MRI and bone scintigraphy, plain radiographs (six weeks after injury) and physical examination during follow-up were used to make the final diagnosis:

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear. It is described how the final diagnosis is made, but it is unclear whether all the steps in the process are interpreted by a blind observer

“Where there was a discrepancy between MRI and bone scintigraphy, plain radiographs (six weeks after injury) and physical examination during follow-up were used to make the final diagnosis.”

Only MRI and bone scintigraphy are described as evaluated by blind observers. |

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear, not for all participant groups, see the description about the reference standard in the left column.

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Probably yes: “A final diagnosis was made after final discharge according to the following reference standard.”

Did patients receive the same reference standard? No, see the description about the reference standard in the left column.

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR (blinding) |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR (interval index - reference standard) |

|

|

Breederveld, 2004 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes “Criteria for exclusion were as follows: 1. Age less than 16 years. 2. Multiple injuries. 3. Old scaphoid fracture. 4. Pseudoarthrosis of the scaphoid bone. 5. No possibility of follow-up”

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Probably no

CT assessed by different radiologists, BS assessed by the same nuclear diagnostician. It is unclear if they had insight into each other’s reports/findings.

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Not applicable

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Probably yes (reference standard matches PICO)

If both bone scintigram and CT scan were positive, the patient was treated and a control CT scan was obtained after treatment. When the control CT scan showed consolidation of a fracture, the patient was considered to be positive for a scaphoid fracture.

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear, not described. Probably not given the information above.

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? No, not for patients who had a negative CT and BS

Did patients receive the same reference standard? No

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR (blinding) |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

|

|

Mallee, 2011 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

CT, MRI, and six week follow-up radiographs were separated into three groups and presented to a panel of three observers: an attending musculoskeletal radiologist, an attending trauma surgeon who treats fractures, and an attending orthopaedic surgeon. The panel evaluated the images for the presence of a scaphoid fracture until a consensus opinion was reached. In the absence of consensus, the panel openly discussed the case. The images were blinded, randomly ordered according to a computer random-number generator, and reviewed in two rounds. In the first round, the panel evaluated the initial radiographs and the CT scan; in the second evaluation, they evaluated the initial radiographs and the MRI. The panel was thereby blinded to the CT results during the MRI evaluation and to the MRI results during the CT evaluation. An interval of two weeks between each round of interpretations was used to limit recognition of the radiographs and recall of the CT scan or MRI.

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Not applicable

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Probably yes (reference standard matches PICO)

Six week follow-up radiographs is the most commonly used reference standard in studies of tests for diagnosis of suspected scaphoid fractures.

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes (see information left column)

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Yes

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

|

|

|

Memarsadeghi, 2006 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Probably yes

"Between June 2000 and July 2002, 29 patients with negative initial posttrauma conventional radiographs were examined with multidetector CT and MR imaging.“; “Only if the initial radiographs were negative for a fracture were the patients prospectively included in this study.”

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes (reference test after 6 weeks)

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Not applicable

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Probably yes (reference standard matches PICO)

Six week follow-up radiographs is the most commonly used reference standard in studies of tests for diagnosis of suspected scaphoid fractures. Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes. Trauma surgeons were blinded to the interpretation of multidetector CT and MR images.

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Yes

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

|

|

|

Rhemrev, 2010 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes, consecutive

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes (Polytrauma patients, patients younger than 18 years and those with contraindications for bone scintigraphy or CT were excluded)

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

A resident and consultant radiologist evaluated the radiographs and CT images. A consultant clinical nuclear physician evaluated all bone scans. For both the CT and the bone scintigraphy, observers filled in a standard form blind to each other and blind to all other data.

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Not applicable

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Probably yes (reference standard matches PICO)

A final diagnosis was performed after final discharge according to the following reference standard:

If CT and bone scintigraphy showed no fracture, the final diagnosis was no fracture Patients with a scaphoid fracture either on CT or bone scintigraphy were treated with a scaphoid forearm cast. Standard scaphoid radiographs were made 6 weeks after injury.

In case of discrepancy between CT and bone scintigraphy, both radiographic (6 weeks after injury) and physical reevaluation during follow-up were used to make a final diagnosis.

fracture after 2 weeks, the final diagnosis was fracture

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Yes

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

|

|

|

De Zwart, 2016 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes, consecutive eligible patients that visited the Emergency Department (ED)

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

All radiographs were reviewed by the attending resident surgeon in the ED and decided if the patient was suitable for inclusion. A consultant radiologist evaluated the MRI and CT images. A consultant nuclear medicine physician evaluated the BS. The observers were blinded to the results of the other investigations.

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Not applicable

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Probably yes (reference standard matches PICO)

The final diagnosis of presence or absence of a scaphoid fracture was confirmed after follow-up according to the following reference standard.

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear for follow-up measurements (not described)

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Yes

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? No, 1 patient was excluded, but no concerns about risk of bias as a result |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR (blinding during follow-up) |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

|

|

|

Breitenseher, 1997 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes, consecutive patient selection

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes (reference test after 6 weeks)

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Not applicable

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Probably yes (reference standard matches PICO)

Six week follow-up radiographs is the most commonly used reference standard in studies of tests for diagnosis of suspected scaphoid fractures.

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Yes

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes, follow-up radiographs were obtained in all patients.

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

|

|

|

Rua, 2019 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes, random sample (RCT)

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes, the SMaRT trial was a prospective, parallel, nonblinded, randomized trial

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes (note: exclusion criteria included participants presenting outside normal MRI working hours; however this could not have influenced diagnostic accuracy results)

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes, reference standard was taken 3 months after index test results.

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Not applicable

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Probablye yes (3-month radiographs probably not differ from 6 week readiographs)

The accuracy of the intervention group (immediate wrist MRI) and the control group (radiograph only) was compared against the three-month series of scaphoid radiographs, as the reference standard.

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear, the authors report that the lack of blinding was an important trail limitation. This might have led to conscious or unconscious bias from the participant and/or the routine care team staff.

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Yes, 3 months.

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes >all participants were invited to a face-to-face three-month research review appointment at which scaphoid radiographs were taken. >all patients included in the analysis were taken into account for accuracy as shown in the calculations on page 991 (n=65 control group; n=67 in MRI group)

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes, see above.

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes, see above. |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK:LOW

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR (blinding) |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

|

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Amrami, K. K. (2005). Radiology corner: diagnosing radiographically occult scaphoid fractures—what’s the best second test?. Journal of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand, 5(3), 134-138. |

narrative review |

|

Bäcker HC, Wu CH, Strauch RJ. Systematic Review of Diagnosis of Clinically Suspected Scaphoid Fractures. J Wrist Surg. 2020 Feb;9(1):81-89. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1693147. Epub 2019 Jul 21. PMID: 32025360; PMCID: PMC7000269. |

no additional relevant studies included compared to Krastman (2020) |

|

Beks RB, Drijkoningen T, Claessen F, Guitton TG, Ring D; Science of Variation Group. Interobserver Variability of the Diagnosis of Scaphoid Proximal Pole Fractures. J Wrist Surg. 2018 Sep;7(4):350-354. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1641716. Epub 2018 Apr 10. PMID: 30174995; PMCID: PMC6117179. |

wrong outcome |

|

Bernard SA, Murray PM, Heckman MG. Validity of conventional radiography in determining scaphoid waist fracture displacement. J Orthop Trauma. 2010 Jul;24(7):448-51. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181c3e865. PMID: 20577078. |

cadaver study |

|

Carpenter CR, Pines JM, Schuur JD, Muir M, Calfee RP, Raja AS. Adult scaphoid fracture. Acad Emerg Med. 2014 Feb;21(2):101-21. doi: 10.1111/acem.12317. PMID: 24673666. |

more recent SR included (Krastman (2020) |

|

Cruickshank J, Meakin A, Breadmore R, Mitchell D, Pincus S, Hughes T, Bently B, Harris M, Vo A. Early computerized tomography accurately determines the presence or absence of scaphoid and other fractures. Emerg Med Australas. 2007 Jun;19(3):223-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2007.00959.x. Erratum in: Emerg Med Australas. 2007 Aug;19(4):387. PMID: 17564689. |

wrong reference standard |

|

de Zwart A, Rhemrev SJ, Kingma LM, Meylaerts SA, Arndt JW, Schipper IB, Beeres FJ. Early CT compared with bone scintigraphy in suspected schapoid fractures. Clin Nucl Med. 2012 Oct;37(10):981. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e31826382cd. PMID: 22955071. |

wrong population |

|