Glucose zelfmanagement bij patiënten met diabetes mellitus (DM) type 1

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de optimale methode van glucose zelfmanagement voor volwassenen met diabetes mellitus type 1 (DM1) behandeld met basaal-bolus insuline of insulinepomp?

Aanbeveling

Bepaal de keuze voor glucosecontrole en insulinebehandeling bij volwassenen met DM1 in nauwe samenspraak met het diabetesbehandelteam en de patiënt:

- Kies bij start van de behandeling bij voorkeur voor FGM als vorm van glucosecontrole.

- Bepaal samen met de patiënt en het diabetesbehandelteam de individuele behandeldoelen van de patiënt. Let hierbij (ook) op: HbA1c, percentage glucosewaarden binnen streefwaarde (Time in range), frequentie en ernst van hypoglykemieën, verminderde hypoglykemie awareness en kwaliteit van leven.

- Kies welke vorm van glucosecontrole en insulinetoediening het meest geschikt is om de behandeldoelen te bereiken. Bespreek hierbij de voor- en nadelen van verschillende methoden, en hou rekening met persoonlijke voorkeuren en mogelijkheden van de patiënt. Gebruik hierbij de Checklist Glucosecontrole en Insulinetherapie (zie hieronder).

- Maak afspraken met de patiënt over de eigen verantwoordelijkheden en verplichtingen die verbonden zijn aan de keuzes die gemaakt zijn voor insulinetoediening en glucosecontrole.

- Overweeg bij niet halen van behandeldoelen en/of bij zwangerschapswens bij voldoende motivatie en inzet van de patiënt een (semi) gesloten systeem.

- Bespreek regelmatig binnen het diabetesbehandelteam de mate waarin de individuele behandeldoelen worden bereikt. Bespreek regelmatig met de patiënt of alle behandeldoelen naar tevredenheid van patiënt én behandelteam worden bereikt, en waar verbetering nodig is. Stel samen met patiënt vast welk behandeldoel eventueel voorrang krijgt bij de aanpak van de behandeling.

- Evalueer jaarlijks of de geformuleerde behandeldoelen gehaald worden, en indien dit niet het geval is, wat hieraan ten grondslag ligt en of er reden is om de behandeldoelen aan te passen. Overleg met de patiënt of de gekozen therapie de juiste is en, indien nodig, wat de vervolgstappen in het behandeltraject kunnen zijn. Dit kan betekenen dat het gebruik van het hulpmiddel beter gefaciliteerd kan worden, of dat dit niet wordt gecontinueerd.

Checklist Glucosecontrole en Insulinetherapie

Glucosecontrole (CGM, FGM)

FGM is de standaard glucosecontrolevorm. Indien CGM overwogen wordt, stel dan vooraf vast welke behandeldoelen beter gehaald kunnen worden door een switch van FGM naar CGM. Overweeg CGM als aan onderstaande voorwaarden is voldaan:

- De patiënt draagt de FGM tenminste 80% van de tijd of er is een goede reden waarom FGM onvoldoende geschikt is (onder andere intolerantie, allergie). Indien de FGM minder dan 80% van de tijd wordt gedragen wordt onvoldoende van FGM geprofiteerd, en zal dit waarschijnlijk ook gelden voor CGM.

- De patiënt kan omgaan met het tellen van koolhydraten en het berekenen van KH/I ratio’s.

- De patiënt kan omgaan met boluscalculatie of gebruikt een boluscalculator.

- De patiënt kan de benodigde software thuis installeren en gebruiken.

- De patiënt is bereid en in staat om koolhydraat-inname, insulinedoseringen en activiteiten te registreren.

- De patiënt kan omgaan met de alarmen en hier adequaat op reageren.

- De patiënt kan adequaat reageren op storingen en glykemische ontregelingen.

- De patiënt is bereid en in staat om regelmatig de data te delen en te evalueren met de zorgverlener, en houdt zich hierbij aan de gemaakte afspraken.

- De patiënt is akkoord dat na een afgesproken termijn (bijvoorbeeld 6 maanden) wordt geëvalueerd of CGM winst heeft opgeleverd, of de vooraf gestelde behandeldoelen zijn gehaald, en of CGM moet worden gecontinueerd. De patiënt is akkoord dat ook bij tussenevaluaties kan worden besloten om de CGM te staken.

Insulinetherapie (MDI, CSII en (semi)gesloten systeem)

MDI en CSII zijn de standaard toedieningsvormen, de keuze tussen deze opties volgt uit gezamenlijke besluitvorming.

Indien een (semi) closed-loop systeem (koppeling van CSII en CGM) overwogen wordt, stel dan vooraf vast welke behandeldoelen beter gehaald kunnen worden door een switch naar een (semi) closed-loop systeem. Overweeg een (semi) closed-loop systeem als aan onderstaande voorwaarden is voldaan:

- De patiënt voldoet aan de eisen voor inzet van CGM (: zie checklist Glucosecontrole).

- De patiënt beschikt over voldoende kennis van het (semi) closed-loop systeem en is in staat en bereid de glucoseregulatie (deels) over te laten aan het systeem.

Overwegingen

De overwegingen en aanbevelingen in dit document zijn bestemd voor niet-zwangere volwassenen met diabetes mellitus type 1 (DM1). De literatuur die hierbij is gebruikt betreft in het algemeen volwassenen (vanaf 18 jaar) met DM1 zonder comorbiditeit of ernstige complicaties zoals nierinsufficiëntie, micro- en/of macrovasculaire complicaties. Indien er sprake is van nierinsufficiëntie of andere ernstige comorbiditeit dient hiermee rekening te worden gehouden.

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Tabel 9 geeft een overzicht van de resultaten uit de literatuuranalyse. De belangrijkste uitkomsten waren:

- CGM had een klinisch (patiënt) relevant voordeel ten opzichte van SMBG (vingerprikken) op de uitkomstmaat tijd binnen streefwaarden, en een klein (triviaal) voordeel op de uitkomstmaat HbA1c. De overall bewijskracht (GRADE) voor de vergelijking tussen CGM en SMBG was laag tot zeer laag.

- FGM had een klein (triviaal) voordeel ten opzichte van SMBG op de uitkomstmaat hypoglykemie-frequentie en tijd binnen streefwaarden. Op de uitkomstmaat HbA1c was er daarentegen een klein (triviaal) voordeel voor SMBG. De overall bewijskracht (GRADE) voor de vergelijking tussen FGM en SMBG was laag tot zeer laag.

- CGM had een klein (triviaal) voordeel ten opzichte van FGM op de uitkomstmaat HbA1c. De overall bewijskracht (GRADE) voor de vergelijking tussen CGM en FGM was laag tot zeer laag.

- (semi)gesloten systemen hadden een klinisch (patiënt) relevant voordeel ten opzichte van FGM en CGM (niet-geïntegreerd) op de uitkomstmaten HbA1c en tijd binnen de streefwaarden. De overall bewijskracht (GRADE) voor de vergelijking tussen (semi-)gesloten systemen en FGM of CGM was laag tot zeer laag.

Tabel 9 Overzicht van de resultaten uit de literatuuranalyse (voor details, zie Samenvatting literatuur)

|

Uitkomstmaat |

Vergelijking tussen sensoren (FGM, CGM), vingerprikken (SMBG), en (semi-) gesloten systemen

|

|||

|

CGM versus SMBG (GRADE) |

FGM versus SMBG (GRADE) |

CGM versus FGM (GRADE) |

FGM en CGM versus (semi)gesloten (GRADE) |

|

|

Cruciale uitkomstmaten |

|

|

|

|

|

HbA1c |

Triviaal verschil (Laag) (voordeel CGM) |

Triviaal verschil (Laag) (voordeel SMBG) |

Triviaal verschil (Laag) (voordeel CGM) |

(semi)gesloten beter (Laag) |

|

Hypoglykemie-frequentie |

Onduidelijk (Zeer laag) |

Triviaal verschil (Laag) (voordeel FGM) |

Onduidelijk (Zeer laag) |

Onduidelijk (Zeer laag) |

|

Ernstige hypoglykemie |

Onduidelijk (Zeer laag) |

Onduidelijk (Zeer laag) |

Onduidelijk (Zeer laag) |

Onduidelijk (Zeer laag) |

|

Kwaliteit van leven |

Onduidelijk (Zeer laag) |

Onduidelijk (Zeer laag) |

Onduidelijk (Zeer laag) |

Geen data |

|

Ketoacidose |

Onvoldoende data |

Onvoldoende data |

Geen data |

Onvoldoende data |

|

Hypoglykemie-angst |

Onduidelijk (Zeer laag) |

Onduidelijk (Zeer laag) |

Onduidelijk (Zeer laag) |

Onduidelijk (Zeer laag) |

|

Overige* |

Geen data |

Geen data |

Geen data |

Geen data |

|

Belangrijke uitkomstmaten |

||||

|

Tijd binnen streefwaarden |

CGM beter (Laag) |

Triviaal verschil (Laag) (voordeel FGM) |

Onduidelijk (Zeer laag) |

(semi)gesloten beter (Laag) |

|

Patiënt-tevredenheid |

Onduidelijk (Zeer laag) |

Onduidelijk (Zeer laag) |

Geen data |

Onduidelijk (Zeer laag) |

|

Microvasculaire complicaties |

Onvoldoende data |

Geen data |

Geen data |

Geen data |

|

Complicaties/bijwerkingen |

Onvoldoende data |

Onvoldoende data |

Geen data |

Onvoldoende data |

|

Overige** |

Geen data |

Geen data |

Geen data |

Geen data |

|

Conclusie en overall bewijskracht |

CGM beter dan SMBG op de uitkomstmaat Tijd binnen streefwaarden, en een klein (triviaal) voordeel voor CGM op de uitkomstmaat HbA1c.

Bewijskracht (GRADE): Laag tot Zeer laag |

FGM beter dan SMBG met kleine (triviale) voordelen op hypoglykemie-frequentie en Tijd binnen streefwaarden. SMBG een klein (triviaal) voordeel op de uitkomstmaat HbA1c.

Bewijskracht (GRADE): Laag tot Zeer laag |

CGM beter dan FGM met een klein (triviaal) voordeel op de uitkomstmaat HbA1c.

Bewijskracht (GRADE): Laag tot Zeer laag |

(semi)gesloten systemen beter dan FGM / CGM op de uitkomstmaten HbA1c en Tijd binnen de streefwaarden.

Bewijskracht (GRADE): Laag tot Zeer laag |

*Overige cruciale uitkomstmaten: frequentie bloedglucosemeting (bij vingerprikken of sensor), nachtelijke hypoglykemie, ziekenhuisopname en depressie

**Overige belangrijke (niet cruciale) uitkomstmaten: verzuim (werk, school) en kosten

In het algemeen is er sprake van een lage tot zeer lage bewijskracht op alle relevante uitkomstmaten. De overall bewijskracht op de cruciale uitkomstmaten is in alle gevallen zeer laag.

Extra overwegingen

Het is onwaarschijnlijk dat toekomstig onderzoek de bewijskracht aanzienlijk zal verhogen. Het is, gezien de aard van de onderzochte interventies, niet mogelijk om RCT’s geblindeerd uit te voeren. Ook is de complexiteit van de studies hoog, en daardoor het aantal geïncludeerde proefpersonen relatief laag. Langlopende observationele studies zouden van waarde kunnen zijn maar gaan gepaard met een hoger risico op bias.

De werkgroep stelt vast dat er een discrepantie lijkt te bestaan tussen de uitkomst van de netwerk-analyse van Pease (2020a, 2020b) en de dagelijkse ervaringen bij patiënten en behandelaars op het punt van patiënttevredenheid en kwaliteit van leven. De werkgroep is van mening dat met name de overstap van SMBG naar FGM en CGM in de praktijk leidt tot grotere tevredenheid bij patiënten, omdat ze niet of nauwelijks meer in hun vingers hoeven te prikken. Dit is belangrijke winst voor de patiënt. Daarnaast bieden CGM en semi-gesloten systemen voor de patiënt voordelen op het gebied van controle over de eigen glucosewaarden. Het is onduidelijk waarom de beschreven studies op het punt van patiënttevredenheid en kwaliteit van leven nauwelijks effect laten zien. Mogelijk zijn de gebruikte meetinstrumenten hiervoor onvoldoende geschikt. Hetzelfde zou kunnen gelden voor de uitkomstmaat hypoglykemie-angst. Recent observationeel onderzoek uitgevoerd in samenwerking met Diabetesvereniging Nederland bevestigt de gunstige effecten van FGM op patiënttevredenheid, ervaren ziektelast en kwaliteit van leven, na een jaar gebruik door 1365 patiënten met diabetes mellitus met HbA1c-waardes van 64 mmol/l en hoger (77% type 1, 16% type 2 en 7% andere vormen; Fokkert, 2019). In de recent gepubliceerde ALERTT1 trial hadden de patiënten met DM1 in de CGM groep na zes maanden, bij een iets lager HbA1c, minder frequent ernstige hypoglycemieën en een hoger percentage glucosewaarden binnen streefwaarde, een statistisch significant lagere score op HFS worry subschaal en een statistisch significant hogere score op de Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire, ten opzichte van de FGM groep (Visser, 2021). Deze studie was, zoals alle studies naar de toegevoegde waarde van CGM en FGM, niet geblindeerd.

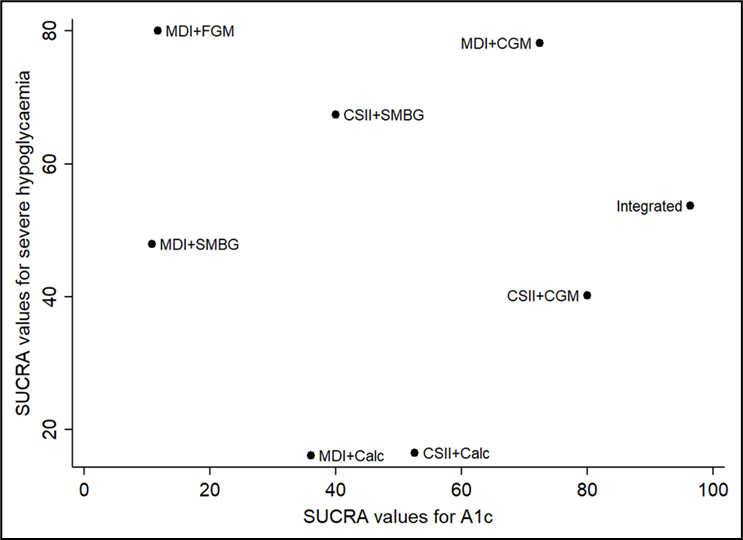

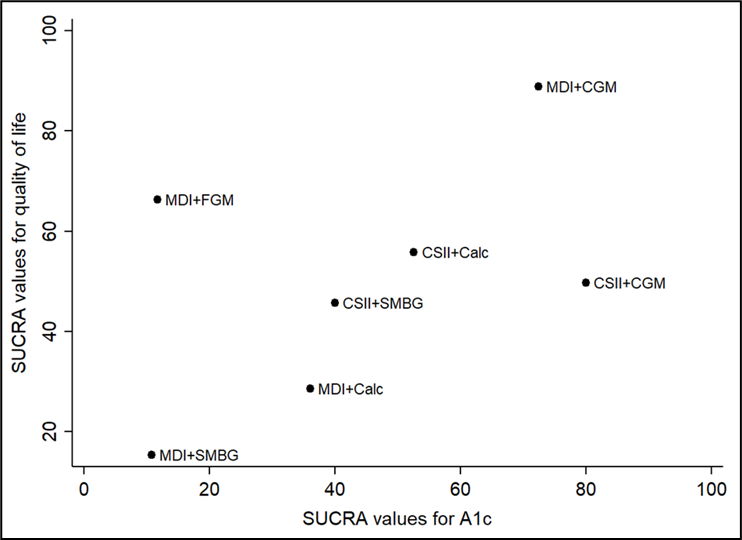

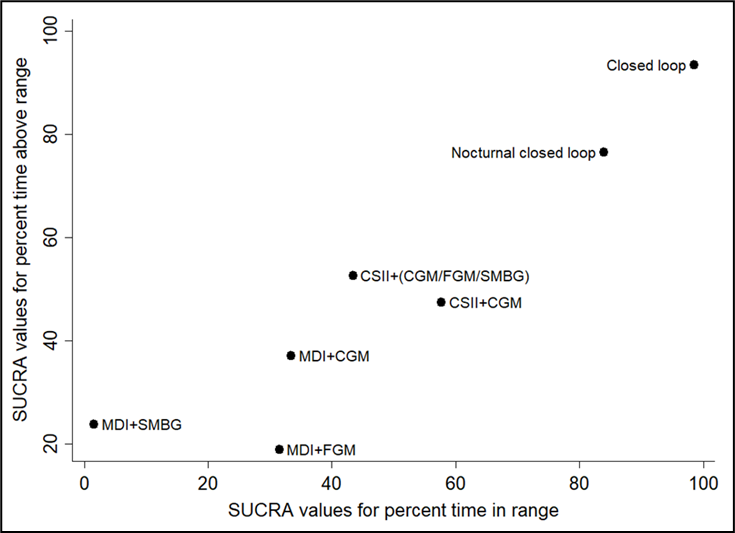

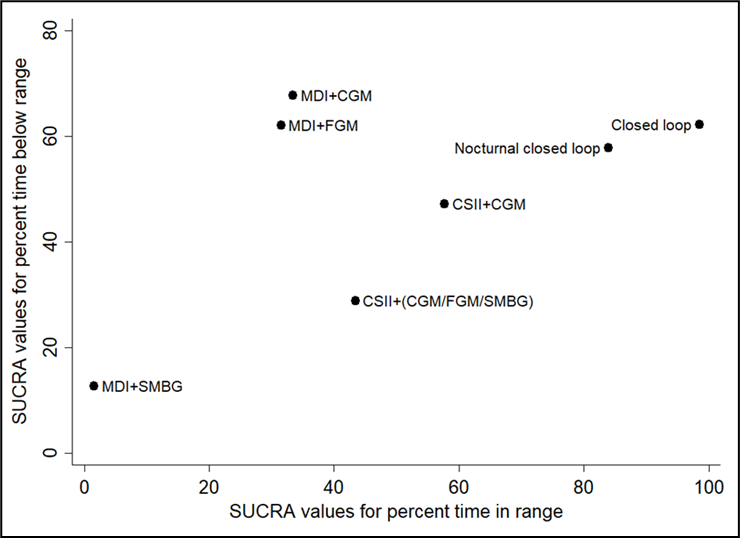

Na de zoekdatum van huidige literatuuranalyse publiceerde Pease (2020b) een aanvullende systematische review en netwerk meta-analyse specifiek gericht op de uitkomstmaat time in range (TIR). Zoekdatum en methodiek komen overeen met de eerdere systematische review van Pease (Pease, 2020a) die de basis vormt van de huidige literatuuranalyse (zie Samenvatting literatuur) met dien verstande dat studies al vanaf een studieduur van twee weken werden geïncludeerd in plaats van zes weken, en er bij de geïntegreerde systemen onderscheid werd gemaakt tussen 'closed loop', 'nocturnal closed loop' (alleen 's nachts ingezet) en 'low-glucose suspend' systemen. Hierbij werd elk systeem dat bestaat uit een combinatie van CGM met CSII die een automatische aanpassing van insulinetoediening mogelijk maakt, beschouwd als een closed-loop systeem. Studies met geïmplanteerde devices werden geëxcludeerd. Uit de netwerk meta-analyse (10 RCT's met in totaal 710 deelnemers) kwam naar voren dat closed-loop systemen de TIR statistisch significant en klinisch relevant vergroten: gemiddelde toename in percentage TIR met 17.9% in vergelijking met MDI+SMBG (95%BI=(9,3 tot 26,4)), met 13.3% in vergelijking met MDI+FGM (95%BI=(3,9 tot 22,7)), met 12.8% in vergelijking met MDI+CGM (95%BI=(4,9 tot 20,6)), en met 8.8% in vergelijking met CSII+CGM (95%BI=(4,2 tot 13,4)). Ook closed-loop systemen die alleen 's nachts functioneel zijn vergrootten de TIR: met gemiddeld 14,0% in vergelijking met MDI+SMBG (95%BI=(6,0 tot 21,9)), met 8.9% in vergelijking met MDI+CGM (95%BI=(1,7 tot 16,1)), en met 4.9% in vergelijking met CSII+CGM (95%BI=(1,7 tot 8,1)). De interventies kunnen worden gerangschikt op basis van hun SUCRA waarde (surface under the cumulative ranking curve). De SUCRA waarde is gebaseerd op zowel locatie (relatieve effectgrootte) als onzekerheid (variantie) van alle interventies in de netwerk meta-analyse. De top-3 interventies met hoogste SUCRA waardes, en daarmee grootste kans om de meest effectieve interventie te zijn, waren op basis van de uitkomsten voor TIR: closed-loop systemen (SUCRA 98.5%), nocturnal closed-loop systemen (SUCRA 83.9%), en CSII in combinatie met CGM (niet-geïntegreerd; SUCRA 57.7%). Zogenaamde cluster ranking plots geven inzicht in de ranking van de interventies op de belangrijkste uitkomstmaten: HbA1c en ernstige hypoglykemie (figuur 5), HbA1c en kwaliteit van leven (figuur 6), time in range en time above range (figuur 7), en time in range en time below range (figuur 8). Bij alle plots geldt dat de interventies die de grootste kans hebben om de meest effectieve interventie te zijn, zich bevinden in de rechter bovenhoek, en de interventies met de kleinste kans om de meest effectieve interventie te zijn, zich bevinden in de linker onderhoek van de plots. Vanwege de lage zekerheid van het bewijs (GRADE laag of zeer laag) moeten de rankings en ranking plots wel met enige voorzichtigheid worden geïnterpreteerd. Uit de ranking plots (figuur 5 tot 8) kwamen geïntegreerde systemen (‘closed loop’, ‘nocturnal closed loop’) en niet-geïntegreerde combinaties van CGM met CSII of MDI als beste naar voren.

Figuur 5

SUCRA rankschikking op basis van reductie in HbA1c en voorkomen van ernstige hypoglykemie (Pease, 2020b). De interventies met de hoogste SUCRA waarde hebben de grootste kans om de meest effectieve interventie te zijn (grootste HbA1c reductie en laagste frequentie ernstige hypoglykemische episodes)

Figuur 6

SUCRA rankschikking op basis van reductie in HbA1c en verbetering in kwaliteit van leven (Pease, 2020b). De interventies met de hoogste SUCRA waarde hebben de grootste kans om de meest effectieve interventie te zijn (grootste HbA1c reductie en grootste verbetering in kwaliteit van leven)

Figuur 7

SUCRA rankschikking op basis van time in range (TIR), en time above range (Pease, 2020b). De interventies met de hoogste SUCRA waarde hebben de grootste kans om de meest effectieve interventie te zijn (hoogste time in range en time above range)

Figuur 8

SUCRA rankschikking op basis van time in range (TIR), en time below range (Pease, 2020b). De interventies met de hoogste SUCRA waarde hebben de grootste kans om de meest effectieve interventie te zijn (hoogste time in range en laagste time below range)

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

In de aanbeveling wordt benadrukt dat de behandelaar samen met de patiënt kiest (en eventueel met zijn/haar direct betrokkenen) voor een bepaalde manier van glucosecontrole in combinatie met basaal-bolus insuline of voor een (semi) gesloten systeem. Er dient met de patiënt te worden besproken welke behandeldoelen in het individuele geval het belangrijkst zijn (bijvoorbeeld voorkomen van hypoglykemieën, verlaging HbA1c, vermijden late complicaties, zwangerschapswens, sociale participatie, algemene kwaliteit van leven). Er kan sprake zijn van een sterk persoonlijk gekleurde voorkeur van de patiënt, mede op basis van eerdere ervaringen, opleidingsniveau, werk- of privésituatie etc. Sommige patiënten geven aan dat ze relatief veel last hebben van de vingerprik, terwijl anderen juist het permanent dragen van een sensor en/of een insulinepomp op het lichaam als bijzonder onaangenaam ervaren. In sommige beroepen (bijvoorbeeld buschauffeur of verkeersvlieger) kan het extra belangrijk zijn om hypoglykemieën te voorkomen. Bij een zwangerschapswens is een zo laag mogelijk HbA1c en het vermijden van glucosewaarden boven de streefwaarde extra belangrijk. Sensortechnologie biedt de mogelijkheid om de glucosewaarden op afstand te monitoren, hetgeen bij de behandeling van jonge kinderen met DM1 (geen onderdeel van de huidige richtlijnmodule) of volwassenen met DM1 en een verstandelijke beperking een voordeel kan zijn. Dit zijn een aantal voorbeelden om aan te geven dat de uiteindelijke keuze wordt bepaald aan de hand van alle beschikbare informatie over de individuele patiënt, en in nauwe samenspraak met de patiënt. Extra patiënteninformatie en keuzehulpen kunnen hierbij belangrijke hulpmiddelen zijn: zie hiervoor de website van Diabetesvereniging Nederland (https://www.dvn.nl/). De werkgroep adviseert om een keuzekaart te ontwikkelen ter ondersteuning van de keuze tussen FGM, CGM en (semi-) gesloten systemen. Bij algemeen gebruik van FGM en CGM zien behandelaren wat er gebeurt met de dagelijkse glucosewaarden en kunnen zij veel beter de educatie en de behandeling afstemmen op de individu.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Een recente systematisch review van kosteneffectiviteitsstudies (Pease 2020c), die literatuur includeert tot april 2019, suggereert dat CGM, FGM en insulinepompen kosteneffectief zijn in vergelijking met SMBG, met name bij groepen met een hoog HbA1c of frequente hypoglykemieën. De kosteneffectiviteit van (semi) gesloten systemen was minder duidelijk. Een belangrijke kanttekening bij deze kosteneffectiviteitsstudies is het gebrek aan betrouwbare gegevens over de lange termijn effecten op cruciale uitkomsten zoals ernstige hypoglykemieën en microvasculaire en macrovasculaire complicaties. Vanwege deze kennislacune is de bewijskracht van de kosteneffectiviteitsstudies (zeer) laag.

In het algemeen zijn de directe kosten (aanschaf en dagelijks gebruik) van nieuwe technologieën zoals FGM, CGM, CSII en (semi) gesloten systemen hoger dan de klassieke behandeling met MDI en SMBG. Omdat sensoren op dit moment duurder zijn dan de SMBG (niet rekening houdend met potentiële lange termijn kostenbesparingen) wordt van patiënten verwacht dat zij bereid en gemotiveerd zijn om optimaal gebruik te maken van de mogelijkheden die sensortherapie biedt. Van de behandelaars wordt gevraagd de inzet van deze sensoren doelmatig voor te schrijven, dat wil zeggen de beschikbare middelen optimaal te benutten. Met dit oogpunt is door de Nederlandse Diabetesfederatie een consensusdocument opgesteld met kwaliteitscriteria voor optimale en doelmatige inzet van FGM en CGM (NDF, 2020). Eerder stelde de NDF kwaliteitscriteria op voor de doelmatig inzet van insulinepomptherapie (NDF, 2015). Uiteindelijk moeten de hogere directe kosten worden afgezet tegen winst op middellange en lange termijn zoals: frequentie van ziekenhuisopname wegens hyper- of hypoglycemische ontregeling, late complicaties zoals nierinsufficiëntie, blindheid, amputaties, cardiovasculaire en andere complicaties, verminderde arbeidsproductiviteit door ziekteverzuim of arbeidsongeschiktheid, en psychische stoornissen zoals depressie of burn-out. Iedere patiënt met DM1 moet worden aangesproken op de eigen verantwoordelijkheid en het verantwoord en doelmatig gebruik van middelen. Essentieel hierbij is om met de patiënt duidelijke afspraken te maken, bijvoorbeeld over het delen en gezamenlijk evalueren van data, het nakomen van controle-afspraken, en het waar nodig aanpassen van gedrag. Door behandelaar en patiënt moet regelmatig worden geëvalueerd wat de meerwaarde van het gebruik van de duurdere technologieën is en of de hogere kosten gerechtvaardigd zijn. Bij onvoldoende winst kan worden besloten om een duurdere behandeling te vervangen door een goedkopere, meer eenvoudige behandeling.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Behandeling van patiënten met DM1 is teamwork. In de dagelijkse praktijk is de patiënt de eigen behandelaar doordat er steeds weer op basis van diverse factoren moet worden beslist wat er aan insulinedosering en/of koolhydraat-inname moet worden gedaan. Het behandelteam (diabetesverpleegkundige, internist/kinderarts-endocrinoloog, diëtist) dient uiteraard deskundig, betrokken, toegewijd en goed bereikbaar te zijn voor vragen en ondersteuning van de patiënt (zie verder de zorgstandaard diabetes mellitus van de NDF (NDF, 2021;)). Ook goede bereikbaarheid van de leverancier van CGM, FGM en (semi) gesloten systemen is belangrijk bij storingen. Haalbaarheid en implementatie van de richtlijn is dus sterk afhankelijk van de beschikbaarheid van een deskundig diabetesteam. Anno 2021 is het ook essentieel dat patiënt met het team kan overleggen via diverse communicatiemedia, waarbij steeds alle partijen inzage hebben in de gegevens omtrent insulinedoseringen, glucosewaarden etc. In de zorgstandaard diabetes mellitus van de NDF wordt verder ingegaan op de kwaliteitseisen die worden gesteld aan het diabetes-behandelteam (NDF, 2021;). Voor de vergoeding van FGM, CGM en (semi) gesloten systemen zijn in de afgelopen tijd belangrijke stappen gezet. FGM en - in specifieke gevallen - CGM worden sinds kort volledig vergoed, en drukken niet meer op het ziekenhuisbudget. Raadpleeg de website van het Zorgininstituut voor de huidige vergoedingscriteria van FGM en CGM (ZIN, 2021;). Diabeteshulpmiddelen (Zvw) | Verzekerde zorg | Zorginstituut Nederland De beperkte vergoeding van CGM is éen van de aandachtspunten voor de implementatie van de aanbevelingen in de richtlijn. Ook voor de vergoeding van (semi) gesloten systemen zijn inmiddels goede afspraken gemaakt: de vergoeding van CSII is over het algemeen goed geregeld, en de bijbehorende sensortechnologie wordt inmiddels ook buiten het ziekenhuisbudget om gefinancierd. Patiënt en behandelaar lopen nog wel aan tegen het probleem van de voortschrijdende technologie: zo vergoedt de verzekeraar meestal een nieuwe insulinepomp na 4 jaar, terwijl er bijvoorbeeld na 2 jaar al een geavanceerder (semi) gesloten systeem op de markt komt waar de patiënt gebruik van zou willen maken. Zoals al eerder aangegeven is de keuze van een bepaalde vorm van insulinebehandeling in combinatie met een bepaalde vorm van glucosecontrole individueel bepaald. Niet iedere patiënt is even geschikt voor iedere behandelvorm. De complexiteit van de techniek, maar ook het vermogen om te kunnen rekenen met koolhydraten, kunnen beperkende factoren zijn, bijvoorbeeld bij ouderen of mensen met een laag opleidingsniveau. Ook andere factoren zoals taal of cultuur kunnen de communicatie tussen zorgverlener, patiënt en familie bemoeilijken, hetgeen van invloed kan zijn op het maken van een keuze. Mogelijk kan een deel van deze beperkingen worden verminderd door hulpverleners met speciale expertise en/of een migratie-achtergrond.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Op basis van de literatuuranalyse komt de werkgroep tot de conclusie dat er aanwijzingen zijn dat FGM en CGM voordelen bieden ten opzichte van SMBG, en dat (semi) gesloten systemen voordelen bieden ten opzichte van FGM en CGM. De voordelen zijn het duidelijkst voor HbA1c, TIR (tijd binnen glucose-streefwaarden) en afname van hypoglykemie frequentie. Eerder onderzoek (DCCT, 1993) heeft laten zien dat verlaging van het HbA1c geassocieerd is met minder microvasculaire complicaties. De werkgroep is dan ook van mening dat het op basis van een betere glucosecontrole (HbA1c dichter bij streefwaarde en glucose langer binnen de glucose-streefwaarden), aannemelijk is dat FGM en CGM, en met name (semi) gesloten systemen, belangrijke winst opleveren voor de patiënt. Ook op theoretische gronden bieden FGM, CGM en (semi) gesloten systemen de patiënt een betere controle over de bloedglucose waarden dan SMBG. Daarnaast vormt SMBG (vingerprikken en stripjes) in het algemeen een grotere belasting voor de patiënt. De directe kosten zijn hoger voor CGM dan voor FGM, en het hoogst voor (semi-)gesloten systemen. Tenslotte is het gebruik van FGM eenvoudiger dan het gebruik van CGM of een (semi-)gesloten systeem, een factor die vooral belangrijk is bij behandeling net na de diagnose DM1.

Omdat de waarde die patiënten hechten aan de voordelen en nadelen van genoemde behandelopties zal variëren, en de persoonlijke voorkeuren van patiënten een belangrijke rol spelen in de gezamenlijke behandelbeslissing, komt de werkgroep tot een conditionele aanbeveling. De werkgroep adviseert om de keuze voor glucosecontrole en insulinebehandeling te bepalen in nauwe samenspraak met het diabetesbehandelteam en de patiënt, bij voorkeur te starten met FGM als vorm van glucosecontrole, en vervolgbeleid af te stemmen op de individuele behandeldoelen van de patiënt. Er kunnen redenen zijn om met CGM te starten in plaats van FGM, zo zijn er aanwijzingen dat CGM voordelen biedt ten opzichte van FGM (zonder alarm) bij personen met verminderde hypoglykemie awareness (Reddy, 2018). Onder voorwaarde van voldoende motivatie en inzet van de patiënt, kan een (semi) gesloten systeem worden overwogen als de behandeldoelen niet worden gehaald. Naast individuele behandeldoelen zijn duidelijke afspraken met de patiënt over eigen verantwoordelijkheden en verplichtingen van groot belang, net als het regelmatig evalueren van de behandeling.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Zelfmanagement is de hoeksteen van de behandeling van diabetes mellitus type 1 met meermaal daags insuline of een insulinepomp. Een voorwaarde hiervoor is dat men op de hoogte is van de glucosewaarde in het lichaam. Met vingerprikken met meting van glucose in capillair bloed (‘self monitoring of blood glucose’, SMBG) wordt weliswaar een redelijk betrouwbare meting verkregen, maar dit is slechts een momentopname. Bovendien kost vingerprikken tijd en wordt ze als onaangenaam ervaren. Met continue glucose monitoring (CGM) of flash glucose monitoring (FGM) wordt de glucose concentratie in het onderhuids weefsel elke 5 tot 15 minuten bijgehouden. Deze waarden komen goed overeen met de glucose waarden van ongeveer 8 tot maximaal 15 minuten eerder gemeten in het bloed. Hierdoor kan de glucose met minder moeite elk moment worden gecontroleerd en wordt de trend van de glucosewaarden zichtbaar. Dat geeft meer inzicht in de regulatie en zou anticiperen op mogelijke veranderingen eenvoudiger kunnen maken. Op dit moment worden veel patiënten met DM 1 behandeld met een insulinepomp (CSII; continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion) en beschikken zij tevens over een glucosesensor (CGM, FGM). Technologische vooruitgang heeft het mogelijk gemaakt om de glucosesensor te koppelen aan de insulinepomp waardoor de insulinepomp de insulinetoediening kan aanpassen aan de gemeten glucosewaarde. De eerste ontwikkelingen betreffen het staken of verlagen van de insulinetoediening bij een relevante daling van de glucosewaarde om hypo’s te voorkomen. Een tweede ontwikkeling is het ophogen van de insulinetoediening bij een (verwachte) stijging van de glucosewaarde (semi-closed loop systemen). Door deze technologie verwacht men dat bij DM1 patiënten de glucosewaarden minder vaak te laag of te hoog zijn dan voorheen toen patiënten zelf hun insulinedoseringen moesten aanpassen aan gevonden glucosewaarden. Uiteindelijk is de verwachting dat personen met DM1 gebruik zullen kunnen maken van een volledig gesloten systeem, ook wel aangeduid als kunstmatige alvleesklier, waarbij de glucosewaarden zonder interventie van de patiënt door afwisselende toediening van insuline en glucagon binnen het streefgebied blijven.

Een nadeel van de glucosesensoren is dat de glucose niet in bloed wordt gemeten en hierop ongeveer 15 minuten achterloopt. Bovendien zijn CGM en FGM, en semi-closed loop (hybrid closed loop) systemen, duurder dan SMBG. Daarom is het belangrijk dat er een meerwaarde is voor deze apparaten, zowel op het gebied van de glucoseregulatie (HbA1c, hypoglykemie, glucoseschommelingen) als op kwaliteit van leven en overige uitkomsten (bijvoorbeeld arbeidsparticipatie, ziekenhuisopnamen). Gezien de nog beperkte beschikbaarheid van onderzoeksresultaten met betrekking tot volledig gesloten systemen heeft de werkgroep deze systemen niet geïncludeerd in de uitgangsvraag. Ook systemen waarbij patiënten zelf een koppeling maken tussen CGM/FGM en CSII (“do it yourself looping”) zijn niet onderzocht.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Pease (2020a) did not report on the critical outcome measures depression, hospital admission, nocturnal hypoglycemia, hypo-unawareness and frequency of blood glucose measurements nor on the important outcome measures absenteeism and costs. Therefore, no conclusions can be drawn for these outcome measures.

HbA1c (crucial outcome measure)

SMBG versus CGM

|

Low1 GRADE |

Using CGM for glucose monitoring may result in little to no reduction of HbA1c levels, compared to using SMBG, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

FGM versus SMBG

|

Low2 GRADE |

Using FGM for glucose monitoring may result in little to no reduction in HbA1c levels, compared to using SMBG, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

FGM versus CGM

|

Low3 GRADE |

Using CGM for glucose monitoring may result in little to no reduction of HbA1c levels, compared to using FGM, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

CGM/FGM versus integrated

|

Low4 GRADE |

Using an integrated system for glucose monitoring and insulin delivery may result in a greater reduction in HbA1c levels, compared to using CGM or FGM, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

Hypoglycemia (crucial outcome measure)

SMBG versus CGM

|

Very low5 GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect is of using CGM for glucose monitoring on the outcome measure non-severe hypoglycemia compared to using SMBG, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

FGM versus SMBG

|

Low6 GRADE |

Using FGM for glucose monitoring may result in little to no reduction in episodes of non-severe hypoglycemia compared to using SMBG, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

FGM versus CGM

|

Very low7 GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of using FGM for glucose monitoring on the outcome measure non-severe hypoglycemia compared to using CGM, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

CGM/FGM versus integrated

|

Very low8 GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of using an integrated system for glucose monitoring and insulin delivery on the outcome measure non-severe hypoglycemia compared to using CGM or FGM, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

Severe hypoglycemia (crucial outcome measure)

SMBG versus CGM

|

Very low9 GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of using CGM for glucose monitoring on the incidence of severe hypoglycemic events compared to using SMBG, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

FGM versus SMBG

|

Very low10 GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of using FGM for glucose monitoring on the incidence of severe hypoglycemic events compared to using SMBG, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

FGM versus CGM

|

Very low11 GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of using FGM for glucose monitoring on the incidence of severe hypoglycemic events compared to using CGM, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

CGM/FGM versus integrated

|

Very low12 GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of using an integrated system for glucose monitoring and insulin delivery on the incidence of severe hypoglycemic events compared to using CGM or FGM, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

Quality of life (crucial outcome measure)

SMBG versus CGM

|

Very low13 GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of using CGM for glucose monitoring on the outcome measure quality of life compared to using SMBG, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

FGM versus SMBG

|

Very low14 GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of using FGM for glucose monitoring on the outcome measure quality of life compared to using SMBG, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

FGM versus CGM

|

Very low15 GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of using FGM for glucose monitoring on the outcome measure quality of life compared to using CGM, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

CGM/FGM versus integrated

|

-16 GRADE |

Due to lack of data, it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the effect of using an integrated system for glucose monitoring and insulin delivery on the outcome measure quality of life compared to using CGM or FGM, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

Ketoacidosis (crucial outcome measure)

All comparisons

|

-17 GRADE |

Due to insufficient evidence (lack of statistical power; few events), it was not possible to draw conclusions for the outcome measure episodes of ketoacidosis, comparing SMBG, CGM, FGM and integrated systems, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

Fear of hypoglycemia (crucial outcome measure)

SMBG versus CGM

|

Very low18 GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of using CGM for monitoring glucose levels on the outcome measure fear of hypoglycemia compared to using SMBG, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

FGM versus SMBG

|

Very low19 GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of using FGM for monitoring glucose levels on the outcome measure fear of hypoglycemia compared to using SMBG, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

FGM versus CGM

|

Very low20 GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of using FGM for monitoring glucose levels on the outcome measure fear of hypoglycemia compared to using CGM, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

CGM/FGM versus integrated

|

Very low21 GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of using an integrated system for glucose monitoring and insulin delivery on the outcome measure fear of hypoglycemia compared to using CGM or FGM, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

Time in target range of blood glucose (crucial outcome measure)

SMBG versus CGM

|

Low22 GRADE |

Using CGM for glucose monitoring may result in more time in target range of blood glucose, compared to using SMBG, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

FGM versus SMBG

|

Low23 GRADE |

Using FGM for glucose monitoring may result in little to no increase in time within the target range of blood glucose, compared to using SMBG, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

FGM versus CGM

|

Very low24 GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of using FGM for monitoring glucose levels on the outcome measure time within the target range of blood glucose compared to using CGM, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

CGM/FGM versus integrated

|

Low25 GRADE |

Using an integrated system for glucose monitoring and insulin delivery may increase the time within the target range of blood glucose compared to using FGM or CGM, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

Other crucial outcome measures (depression, hospital admission, nocturnal hypoglycemia, hypo-unawareness and frequency of blood glucose measurements)

All comparisons

|

- GRADE |

The outcome measures depression, hospital admission, nocturnal hypoglycemia, hypo-unawareness and frequency of blood glucose measurements were not reported.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

Patient satisfaction (important outcome measure)

SMBG versus CGM

|

Very low26 GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of using CGM for glucose monitoring on the outcome measure patient satisfaction compared to using SMBG, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

FGM versus SMBG

|

Very low27 GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of using FGM for glucose monitoring on the outcome measure patient satisfaction compared to using SMBG, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

FGM versus CGM

|

-28 GRADE |

Due to lack of data, it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the effect of using FGM for glucose monitoring on the outcome measure patient satisfaction compared to using CGM in adults with DM1 (no GRADE).

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

CGM/FGM versus integrated

|

Very low29 GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of using an integrated system for glucose monitoring and insulin delivery on the outcome measure patient satisfaction compared to using an CGM or FGM, in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

Microvascular complications (important outcome measure)

SMBG versus CGM

|

-30 GRADE |

Due to few events, it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the effect of using CGM for glucose monitoring on the outcome measure microvascular complications, compared to using SMBG in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

FGM versus SMBG

|

-31 GRADE |

Due to lack of data, it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the effect of using FGM for glucose monitoring on the outcome measure microvascular complications, compared to using SMBG in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

FGM versus CGM

|

-32 GRADE |

Due to lack of data, it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the effect of using FGM for glucose monitoring on the outcome measure microvascular complications, compared to CGM in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

CGM/FGM versus integrated

|

-33 GRADE |

Due to lack of data, it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the effect of using an integrated system for glucose monitoring and insulin delivery on the outcome measure microvascular complications, compared to using CGM or FGM in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

Adverse events (important outcome measure)

SMBG versus CGM

|

-34 GRADE |

Due to insufficient data (low statistical power; few events), it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the effect of using CGM for glucose monitoring on the outcome measure adverse events compared to using SMBG in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

FGM versus SMBG

|

-35 GRADE |

Due to insufficient data (low statistical power; few events), it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the effect of using FGM for glucose monitoring on the outcome measure adverse events, compared to using SMBG in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

FGM versus CGM

|

-36 GRADE |

Due to insufficient data (low statistical power; few events), it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the effect of using FGM for glucose monitoring on the outcome measure adverse events, compared to CGM in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

CGM/FGM versus integrated

|

-37 GRADE |

Due to insufficient data (low statistical power; few events), it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the effect of using an integrated system for glucose monitoring and insulin delivery on the outcome measure adverse events, compared to using CGM or FGM in adults with DM1.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

Other important outcome measures (absenteeism and costs)

All comparisons

|

- GRADE |

The outcome measures absenteeism and costs were not reported.

Sources: (Pease, 2020a) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Pease (2020a) performed a systematic review and network meta-analysis on available self-management technologies for management of DM1, including literature up to April 24, 2019. The investigators searched several databases, including Medline, Medline in-process and other non-indexed citations, EMBASE, PubMed, All Evidence-Based Medicine Reviews, Web of Science, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and PROSPERO. Pease (2020a) included trials which had a duration of at least 6 weeks and which included nonpregnant community dwelling adults with DM1. If data from the trials were not complete and additional correspondence with the authors did not result in additional data, the trials were excluded. In total, 52 RCT’s of parallel or crossover design were included in the network meta-analysis or narrative synthesis, with a total of 3,975 patients. Characteristics of the included studies are described in table 1. Most of the studies were performed in Europe (59%), followed by USA (24%), Canada (10%), UK (12%) and Australia (2%). 78% of the trials received funding or material support from industrial parties. Several methods of insulin delivery, blood glucose monitoring and advising on insulin dosing were compared. These methods include: multiple daily injections (MDI), continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion systems (CSII (low glucose suspend feature, semi closed-loop systems, closed-loop systems)), self-monitoring of blood glucose via capillary testing (SMBG), continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), flash glucose monitors (FGM), insulin bolus calculators (calc) and smart device applications. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. Most studies were open-label studies, carrying a high risk of performance bias, due to the lack of blinding. In many instances the method of randomisation (sequence generation and allocation concealment) was unclear. In part of the studies risk of detection bias was high with regard to the outcome measures quality of life and (severe) hypoglycemia. More details on the risk of bias assessment of each individual study can be found in the publication of Pease (2020a). The quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE methodology. The outcomes HbA1c, severe hypoglycemia, non-severe hypoglycemia and quality of life were analyzed by performing network meta-analysis. Network meta-analysis uses information from both direct and indirect comparisons between interventions. It is however important to consider that results which are (partly) based on indirect comparisons might be less reliable. In their network meta-analysis Pease (2020a) used group-level data and followed a frequentist approach. Random effect models were used to synthesize the data. Potential effect modifiers like age, diabetes duration and HbA1c were considered to assure transitivity. Other outcome measures were presented as a narrative synthesis, in which only direct comparisons were considered.

Table 1 Characteristics of the included studies (n=52 RCTs) in the review of Pease (2020a)

|

Characteristic |

Result |

|

Sample size (mean±SD) |

78±79 participants |

|

Duration of intervention (mean±SD) |

8±7 months |

|

Age (mean±SD) |

40.2±6.2 years |

|

Baseline HbA1c (mean±SD) |

8.4%±0.8% |

|

Duration of DM1 (years±SD) |

19.5±9.7 years |

Results

One study was included in the literature analysis (Pease, 2020a). Pease (2020a) did not report on the critical outcome measures depression, hospital admission, nocturnal hypoglycemia, hypo-unawareness and frequency of blood glucose measurements nor on the important outcome measures absenteeism and costs.

Pease (2020a) performed a network meta-analysis for the outcome measures HbA1c, severe hypoglycemia, non-severe hypoglycemia and quality of life. Narrative synthesis was performed for the outcome measures ketoacidosis, fear of hypoglycemia, time in target range of blood glucose, patient satisfaction, microvascular complications and adverse events. Since we are interested in the comparisons between SMBG versus CGM, FGM versus SMBG, FGM versus CGM and CGM/FGM versus integrated systems, we restricted our analyses to these comparisons (independent of insulin delivery modalities). Bolus calculator was interpreted as SMBG glucose management system. Note that a separate network meta-analysis (Pease, 2020b) was published after the search date of the current guideline module, analyzing time in target range of blood glucose, the results are briefly discussed in the section ‘Overwegingen’.

HbA1c (crucial outcome measure)

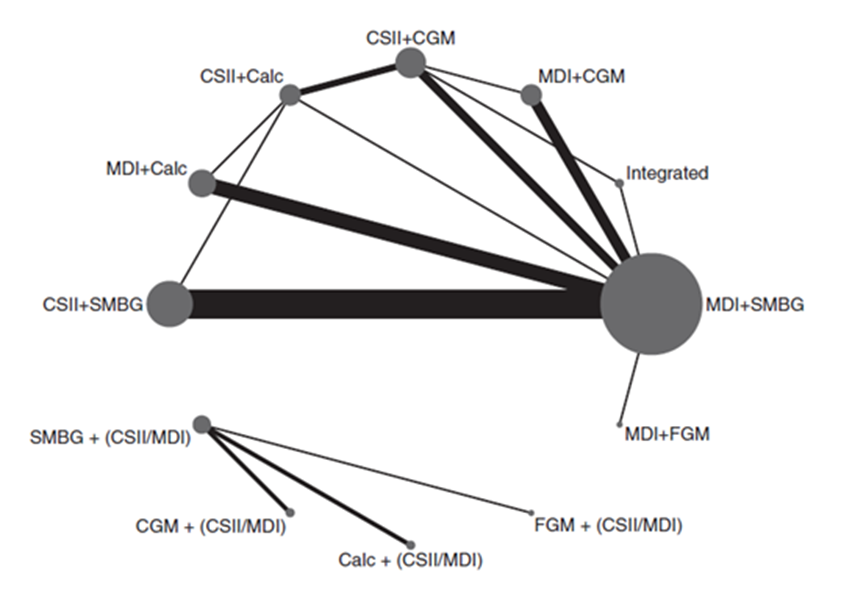

Pease (2020a) included 43 studies that reported on the outcome measure HbA1c. The network plots are shown in Figure 1a and 1b.

Figure 1a (top panel) and figure 1b (lower panel)

Network plot of diabetes management comparisons comprising the same within-study insulin delivery modalities for the outcome of HbA1c. The network consists of eight interventions (nodes) and 38 RCTS (3,330 participants)

Network plot of diabetes management comparisons comprising the different within-study insulin delivery modalities for the outcome of HbA1c. The network consists of four interventions (nodes) and 5 RCTS (542 participants).

The size of each circle and the width of each line is proportional to respectively the number of participants randomized to each intervention and the number of trials. Calc: bolus calculator; CGM: continuous glucose monitoring; CSII: continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion; FGM: flash glucose monitoring; MDI: multiple daily injections; SMBG: self-monitoring of blood glucose

Results of the network meta-analysis for the outcome measure HbA1c for the different comparison categories (SMBG versus CGM, FGM versus SMBG, FGM versus CGM and CGM/FGM versus integrated systems) are reported in Table 2. Pease (2020a) reported mean differences (95%CI) in HbA1c (%) for several comparisons within the four comparison categories and stratified for studies with same versus different within study group insulin delivery modalities. Since the data on those comparisons are not independent from each other, it was not valid to pool the data.

Most of the included trials had high risk of performance bias because participants and clinicians were not blinded to the intervention. It is however unlikely that this had a relevant influence on the results on the outcome measure HbA1c. However, in part of the trials the method of randomisation (sequence generation and/or allocation concealment) was unclear, which might have led to bias.

SMBG versus CGM

SMBG resulted in higher HbA1c (%) values (smaller HbA1c reductions from baseline) compared to CGM. Mean differences in HbA1c (%) between SMBG and CGM varied between 0.15 and 0.52, in favor of CGM (Table 2a). The difference between MDI+SMBG versus CSII+CGM is statistically significant and clinically relevant (> 0.5%, method of insulin delivery differed also between the treatment groups). None of the other differences reach the threshold for a clinically relevant effect. Assuming that the efficacy of insulin treatment is mainly determined by the quality (timing, frequency) of glucose measurement and not by the method of insulin delivery (MDI or CSII), the results indicate overall that CGM has a consistent advantage over SMBG, although the added value in terms of additional improvement in HbA1c is small and does not reach our threshold for clinical relevance (0.5%).

FGM versus SMBG

SMBG resulted in lower HbA1c (%) values (larger HbA1c reductions from baseline) compared to FGM. Mean differences in HbA1c (%) between SMBG and FGM varied between 0.01 and 0.39, in favor of SMBG (Table 2b). None of these differences reach the threshold for a statistically significant effect or a clinically relevant effect (< 0,5%). Assuming that the efficacy of insulin treatment is mainly determined by the quality (timing, frequency) of glucose measurement and not by the method of insulin delivery (MDI or CSII), the results indicate overall that SMBG has a consistent advantage over FGM, although the added value in terms of additional improvement in HbA1c is small and does not reach our threshold for clinical relevance (0.5%).

FGM versus CGM

FGM resulted in higher HbA1c (%) values (smaller HbA1c reductions from baseline) compared to CGM. Mean differences in HbA1c (%) between FGM and CGM varied between 0.18 and 0.61, in favor of CGM (Table 2c). For the comparisons between MDI+FGM versus MDI+CGM and MDI+FGM versus CSII+CGM those differences are clinically relevant (> 0,5%) and for MDI+FGM versus CSII+CGM also statistically significant. None of the other differences reach the threshold for a clinically relevant effect. Assuming that the efficacy of insulin treatment is mainly determined by the quality (timing, frequency) of glucose measurement and not by the method of insulin delivery (MDI or CSII), the results indicate overall that CGM has a consistent advantage over FGM, although the added value in terms of additional improvement in HbA1c may be relatively small and not reach our threshold for clinical relevance (0.5%).

CGM/FGM versus integrated

CGM or FGM combined with, but not integrated with CSII, or combined with MDI resulted in higher HbA1c (%) values (smaller HbA1c reductions from baseline) compared with integrated systems. Mean differences in HbA1c (%) between FGM or CGM (non-integrated) and integrated systems varied between 0.36 and 0.96, in favor of the integrated system (Table 2d). For the comparison between MDI+FGM versus integrated system this difference was statistically significant and clinically relevant (> 0,5%). None of the other differences reach the threshold for a clinically relevant effect assuming that the efficacy of insulin treatment is mainly determined by the quality (timing, frequency) of glucose measurement and not by the method of insulin delivery (MDI or CSII), the results indicate overall that integrated systems have a consistent advantage over CGM or FGM. The added value of integrated systems in terms of additional improvement in HbA1c might also reach our threshold for clinical relevance (0.5%).

Table 2 Mean difference (network estimate; 95%CI) in the outcome measure HbA1c (%) for different diabetes management comparisons (adapted from Pease (2020a)

|

A) SMBG and CGM |

|||

|

Comparison* |

Mean difference (95%CI) |

Direct comparisons (number of studies) |

Indirect comparisons only |

|

Studies with same within study group insulin delivery modality |

|||

|

CSII+Calc versus CSII+CGM |

0.22 (−0.11 to 0.54) |

2 |

|

|

CSII+SMBG versus CSII+CGM |

0.31 (0.00 to 0.62) |

|

x |

|

MDI+SMBG versus CSII+CGM |

0.52 (0.26 to 0.78) |

4 |

|

|

MDI+Calc versus CSII+CGM |

0.34 (0.01 to 0.66) |

|

x |

|

CSII+Calc versus MDI+CGM |

0.15 (−0.24 to 0.54) |

|

x |

|

CSII+SMBG versus MDI+CGM |

0.25 (−0.04 to 0.53) |

|

x |

|

MDI+Calc versus MDI+CGM |

0.27 (−0.04 to 0.59) |

|

x |

|

MDI+SMBG versus MDI+CGM |

0.45 (0.22 to 0.68) |

3 |

|

|

Studies with different within study group insulin delivery modality |

|||

|

SMBG versus CGM |

0.19 (-0.41 to 0.79) |

2 |

|

|

B) FGM and SMBG |

|||

|

Comparison |

Mean difference (95%CI) |

Direct comparisons (number of studies) |

Indirect comparisons only |

|

Studies with same within study group insulin delivery modality |

|||

|

MDI+FGM versus CSII+Calc |

0.39 (−0.22 to 1.01) |

|

x |

|

MDI+FGM versus CSII+SMBG |

0.29 (−0.25 to 0.84) |

|

x |

|

MDI+FGM versus MDI+SMBG |

0.09 (−0.43 to 0.61) |

1 |

|

|

MDI+FGM versus MDI+Calc |

0.27 (−0.29 to 0.83) |

|

x |

|

Studies with different within study group insulin delivery modality |

|||

|

SMBG versus FGM |

0.01 (-0.65 to 0.67) |

1 |

|

|

C) FGM and CGM |

|||

|

Comparison |

Mean difference (95%CI) |

Direct comparisons (number of studies) |

Indirect comparisons only |

|

Studies with same within study group insulin delivery modality |

|||

|

MDI+FGM versus CSII+CGM |

0.61 (0.03 to 1.19) |

|

x |

|

MDI+FGM versus MDI+CGM |

0.54 (−0.03 to 1.11) |

1 |

|

|

Studies with different within study group insulin delivery modality |

|||

|

FGM versus CGM |

0.18 (-0.71 to 1.07) |

|

x |

|

D) CGM/FGM and integrated |

|||

|

Comparison |

Mean difference (95%CI) |

Direct comparisons (number of studies) |

Indirect comparisons only |

|

Studies with same within study group insulin delivery modality |

|||

|

CSII+CGM versus integrated |

0.36 (−0.19 to 0.90) |

3 |

|

|

MDI+CGM versus integrated |

0.42 (−0.17 to 1.02) |

|

x |

|

MDI+FGM versus integrated |

0.96 (0.20 to 1.72) |

|

x |

CGM: continuous glucose monitoring; CSII: continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion; FGM: flash glucose monitoring; MDI: multiple daily injections; SMBG: self-monitoring of blood glucose.*The intervention which is mentioned secondly is the reference category, for example for the comparison CSII+Calc versus CSII+CGM, CSII+CGM is the reference category. Values in bold are statistically significant (p<0.05)

Ranking of technologies

Network meta-analysis offers the unique possibility to rank the competing interventions. The surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) value may be seen as the percentage of effectiveness (or safety) a treatment achieves in relation to an imaginary treatment that is always the best without any uncertainty. The higher the SUCRA value, and the closer to 100%, the higher the likelihood that an intervention is in the top rank or one of the top ranks among the competing interventions. Note that the evidence on which the SUCRA rankings are based is of low certainty and therefore rankings should be interpreted with caution.

Ranking interventions by HbA1c reduction favored integrated systems (SUCRA=96), CSII with standalone CGM (SUCRA=80), MDI with CGM (SUCRA=73), and CSII with bolus calculators (SUCRA=53).

Hypoglycemia (crucial outcome measure)

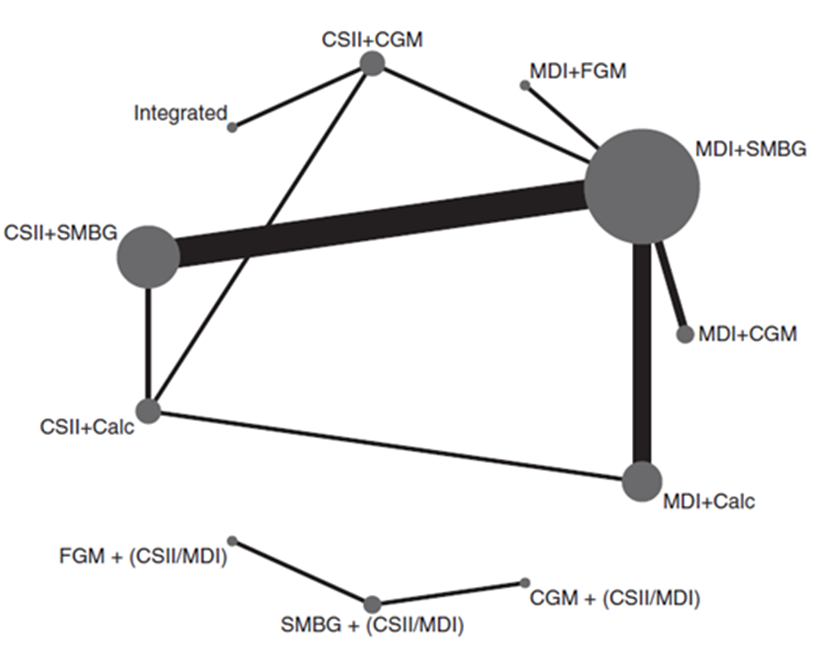

Pease (2020a) included 19 studies that reported on the outcome measure non-severe hypoglycemia, which was defined as hypoglycemic threshold < 3.9mmol/L (70mg/dL). If multiple thresholds were reported, the highest threshold < 3.9mmol/L (70mg/dL) was used. The presence of hypoglycemic symptoms was not required since this information was often not available in the studies. Note that the hypoglycemic threshold used by Pease (2020a) is considerably higher than the threshold of < 3.0 mmol/L defined by the current guideline committee (also see Ratner, 2018). The network plots are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Network plots of diabetes management comparisons for the outcome non-severe hypoglycemia, stratified for studies with same versus different within study group insulin delivery modality (top and lower panel respectively). The networks consist of eight and three interventions (nodes) and 19 RCTS (2,080 participants). Details on number of RCT’s and participants are not reported specifically for the same versus different within-study insulin delivery modalities. The size of each circle and the width of each line is proportional to the number of participants randomized in the intervention and the number of trials. Calc: bolus calculator; CGM: continuous glucose monitoring; CSII: continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion; FGM: flash glucose monitoring; MDI: multiple daily injections; SMBG: self-monitoring of blood glucose

Results of the network meta-analysis for the outcome measure non-severe hypoglycemia for the different comparison categories (SMBG versus CGM, FGM versus SMBG, FGM versus CGM and CGM/FGM versus integrated systems) are reported in Table 3. Pease (2020a) reported mean differences (95%CI) in non-severe hypoglycemic events per patients/week for several comparisons within the four comparison categories and stratified for studies with same versus different within study group insulin delivery modalities. Since those comparisons are not independent from each other, it was not valid to pool the data.

Most studies were open-label studies and therefore carrying a high risk of performance bias, due to the lack of blinding. It is likely that this had a large impact on the results on the outcome measure non-severe hypoglycemia. Besides, in part of the trials the method of randomisation (sequence generation and/or allocation concealment) was unclear, which also might have led to bias. Finally, considerable bias may result from the fact that the network meta-analysis combined results from studies using different hypoglycemic thresholds, including studies with high hypoglycemic thresholds (< 3.9 mmol/l) close to the target range of blood glucose (4 to 10 mmol/l).

SMBG versus CGM

The different comparisons between SMBG and CGM revealed inconsistent results. The mean difference in non-severe hypoglycemic events per patient/week between SMBG and CGM varied between -0.27 and 1.65 (Table 3a). Negative values indicate lower number of hypoglycemic events per patient/week for SMBG. It is important to note that CGM may increase the chance of detecting hypoglycemia and result in an overestimation of hypoglycemic events as compared to SMBG. Assuming that the efficacy of insulin treatment is mainly determined by the quality (timing, frequency) of glucose measurement and not by the method of insulin delivery (MDI or CSII), the results indicate overall that CGM has an advantage over SMBG, although the added value in terms of fewer non-severe hypoglycemic events may be relatively small and not reach the threshold for clinical relevance (1 event per patient/week).

FGM versus SMBG

FGM resulted in lower number of hypoglycemic events per patient/week compared to SMBG. The mean difference in non-severe hypoglycemic events per patients/week between FGM and SMBG varied between -0.27 and -0.96, in favor of FGM (Table 3b). It is however likely that patients using FGM checked their glucose levels more frequently compared to patients in the SMBG group. This could have resulted in higher detection rates of hypoglycemic events in the FGM group, compared to the SMBG group. Therefore, it is likely that the difference in number of hypoglycemic events between FGM and SMBG might be even larger, in favor of FGM. Assuming that the efficacy of insulin treatment is mainly determined by the quality (timing, frequency) of glucose measurement and not by the method of insulin delivery (MDI or CSII), the results indicate overall that FGM has a consistent advantage over SMBG, although the added value in terms of fewer non-severe hypoglycemic events may be relatively small and not reach our threshold for clinical relevance (1 event per patient/week).

FGM versus CGM

The different comparisons between FGM and CGM revealed inconsistent results. The mean differences in non-severe hypoglycemic events per patient/week between FGM and CGM were respectively -0.55 (: in favour of FGM) and 0.69 (: in favour of CGM; see Table 3c). It is important to note that CGM may increase the chance of detecting hypoglycemia and result in a slight overestimation of hypoglycemic events as compared to FGM. Although the effect estimates are broad leading to serious imprecision and it remains unclear whether CGM (slightly) reduces the rate of non-severe hypoglycemic events as compared to FGM, or vice versa, the results suggest that the difference in rate of non-severe hypoglycemic events between FGM and CGM may be relatively small and not reach the threshold for clinical relevance (1 event per patient/week).

CGM/FGM versus integrated

The different comparisons between CGM and FGM revealed inconsistent results. The mean differences in non-severe hypoglycemic events per patient/week between CGM/FGM (non-integrated) and integrated systems and varied between -0.64 to 0.60 (Table 3d). Negative values indicate lower number of hypoglycemic events per patient/week for CGM or FGM. Although the effect estimates are broad leading to serious imprecision and it remains unclear whether integrated systems (slightly) reduce the rate of non-severe hypoglycemic events as compared to non-integrated systems (CGM/FGM), the results suggest that the difference in rate of non-severe hypoglycemic events between integrated systems and non-integrated systems (CGM/FGM) may be relatively small and not reach the threshold for clinical relevance (1 event per patient/week).

Table 3 Mean difference (network estimate; 95%CI) in non-severe hypoglycemic events per patient/week for different diabetes management comparisons (adapted from Pease (2020a))

|

A) SMBG and CGM |

|||

|

Comparison* |

Mean difference (95%CI) |

Direct comparisons (number of studies) |

Indirect comparisons only |

|

Studies with same within study group insulin delivery modality |

|||

|

CSII+Calc versus CSII+CGM |

0.42 (−0.86 to 1.69) |

1 |

|

|

CSII+SMBG versus CSII+CGM |

−0.05 (−1.17 to 1.07) |

|

x |

|

MDI+SMBG versus CSII+CGM |

−0.27 (−1.34 to 0.79) |

1 |

|

|

MDI+Calc versus CSII+CGM |

−0.09 (−1.23 to 1.04) |

|

x |

|

CSII+Calc versus MDI+CGM |

1.65 (0.57 to 2.73) |

|

x |

|

CSII+SMBG versus MDI+CGM |

1.18 (0.43 to 1.94) |

|

x |

|

MDI+Calc versus MDI+CGM |

1.14 (0.32 to 1.97) |

|

x |

|

MDI+SMBG versus MDI+CGM |

0.96 (0.30 to 1.63) |

2 |

|

|

Studies with different within study group insulin delivery modality |

|||

|

SMBG versus CGM |

Not reported |

Not reported |

Not reported |

|

B) FGM and SMBG |

|||

|

Comparison |

Mean difference (95%CI) |

Direct comparisons (number of studies) |

Indirect comparisons only |

|

Studies with same within study group insulin delivery modality |

|||

|

MDI+FGM versus CSII+Calc |

−0.96 (−2.13 to 0.20) |

|

x |

|

MDI+FGM versus CSII+SMBG |

−0.50 (−1.36 to 0.37) |

|

x |

|

MDI+FGM versus MDI+SMBG |

-0.27 (−1.07 to 0.52) |

1 |

|

|

MDI+FGM versus MDI+Calc |

−0.45 (−1.38 to 0.48) |

|

x |

|

Studies with different within study group insulin delivery modality |

|||

|

FGM versus SMBG |

Not reported |

Not reported |

Not reported |

|

C) FGM and CGM |

|||

|

Comparison |

Mean difference (95%CI) |

Direct comparisons (number of studies) |

Indirect comparisons only |

|

Studies with same within study group insulin delivery modality |

|||

|

MDI+FGM versus CSII+CGM |

−0.55 (−1.87 to 0.78) |

|

x |

|

MDI+FGM versus MDI+CGM |

0.69 (−0.34 to 1.72) |

|

x |

|

Studies with different within study group insulin delivery modality |

|

|

|

|

FGM versus CGM |

Not reported |

Not reported |

Not reported |

|

D) CGM/FGM and integrated |

|||

|

Comparison |

Mean difference (95%CI) |

Direct comparisons (number of studies) |

Indirect comparisons only |

|

Studies with same within study group insulin delivery modality |

|||

|

CSII+CGM versus integrated |

0.60 (-0.81 to 2.01) |

1 |

|

|

MDI+CGM versus integrated |

−0.64 (−2.53 to 1.25) |

|

x |

|

MDI+FGM versus integrated |

0.05 (−1.88 to 1.99) |

|

x |

CGM: continuous glucose monitoring; CSII: continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion; FGM: flash glucose monitoring; MDI: multiple daily injections; SMBG: self-monitoring of blood glucose.*The intervention which is mentioned secondly is the reference category, for example of the comparison CSII+Calc versus CSII+CGM, CSII+CGM is the reference category. Values in bold are statistically significant (p<0.05)

Ranking of technologies

Ranking technologies by non-severe hypoglycemia rates favored MDI with CGM (SUCRA=95), MDI with FGM (SUCRA=68), and integrated systems comprising low-glucose suspend or hybrid closed-loop therapy (SUCRA=64).

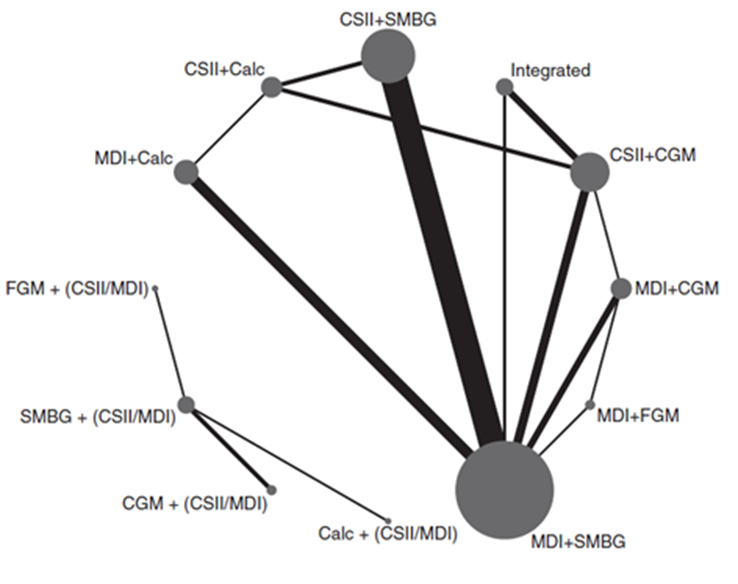

Severe hypoglycemia (crucial outcome measure)

Pease (2020a) included 40 studies that reported on the outcome measure severe hypoglycemia, which was defined as hypoglycemic events requiring third-party assistance. The network plots are shown in Figure 3a and 3b.

Figure 3a and 3b

Network plot of diabetes management comparisons comprising the same within-study insulin delivery modalities for the outcome severe hypoglycemia. The network consists of eight interventions (nodes) and 36 RCTs (2,844 person years)

Network plot of diabetes management comparisons comprising different within-study insulin delivery modalities for the outcome severe hypoglycemia. The network consists of four interventions (nodes) and four RCTs (263 person years). The size of the circle is proportional to the number of participants randomised to the intervention and the width of the line is proportional to the number of trials. Calc: bolus calculator; CGM: continuous glucose monitoring; CSII: continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion; FGM: flash glucose monitoring; MDI: multiple daily injections; SMBG: self-monitoring of blood glucose

Results of network meta-analysis for the outcome measure severe hypoglycemia for the different comparison categories (SMBG versus CGM, FGM versus SMBG, FGM versus CGM and CGM/FGM versus integrated systems) are reported in Table 4. Because of the small number of events, a skewed distribution and variation in study length, Pease (2020a) estimated the rate ratio of participants with at least one severe hypoglycemic event per person-year. Pease (2020a) reported the rate ratios (95%CI) for severe hypoglycemia for several comparisons within the four comparison categories and stratified for studies with same versus different within study group insulin delivery modalities. Since those comparisons are not independent from each other, it was not valid to pool the data. Number needed to treat is calculated based on a background risk of 30% on one severe hypoglycemic event per person-year.

In part of the trials the method of randomisation (sequence generation and/or allocation concealment) was unclear, which might have led to bias. In addition, most of the included trials had high risk of performance bias, since blinding of the participants and the clinicians was impossible. It is however unlikely that this had a large influence on the outcome measure severe hypoglycemia.

SMBG versus CGM

The different comparisons between SMBG and CGM revealed inconsistent results. However, the direction of the effect estimates is mainly in favor of CGM. The rate ratio of patients with at least one severe hypoglycemic event per person-year varied between 0.69 and 3.45 (Table 4a). Values < 1 indicate lower rates of patients with at least one severe hypoglycemic event per person-year for SMBG, compared to CGM. Note that the effect estimates are very broad as a result of the low number of severe hypoglycemic events. Assuming that the efficacy of insulin treatment is mainly determined by the quality (timing, frequency) of glucose measurement and not by the method of insulin delivery (MDI or CSII), the overall results might suggest that CGM has an advantage over SMBG. However, all effect estimates are very imprecise and conclusions are very uncertain.

FGM versus SMBG

FGM resulted in lower rates of patients with at least one severe hypoglycemic event per person-year, compared to SMBG. Rate ratios varied between 0.21 and 0.48 (Table 4b), in favor of FGM, but the effect estimates are very broad. Assuming that the efficacy of insulin treatment is mainly determined by the quality (timing, frequency) of glucose measurement and not by the method of insulin delivery (MDI or CSII), the overall results might suggest that FGM has a consistent advantage over SMBG. However, all effect estimates are very imprecise and conclusions are very uncertain.

FGM versus CGM

FGM resulted in lower rates of patients with at least one severe hypoglycemic event per person-year, compared to CGM. Rate ratios were between 0.33 and 0.72 (Table 4c), in favor of FGM, but the effect estimates are very broad. Assuming that the efficacy of insulin treatment is mainly determined by the quality (timing, frequency) of glucose measurement and not by the method of insulin delivery (MDI or CSII), the overall results might suggest that FGM has an advantage over CGM. However, all effect estimates are very imprecise and conclusions are very uncertain.

CGM/FGM versus integrated

The different comparisons between CGM or FGM and integrated systems revealed inconsistent results. The rate ratio of patients with at least one severe hypoglycemic event per person-year varied between 0.43 and 1.32, but the effect estimates are very broad (Table 4d). Values < 1 indicate lower rates of patients with at least one severe hypoglycemic event per person-year for FGM or CGM, compared to integrated systems. Assuming that the efficacy of insulin treatment is mainly determined by the quality (timing, frequency) of glucose measurement and not by the method of insulin delivery (MDI or CSII), the overall results might suggest that FGM or CGM has an advantage over integrated systems. However, all effect estimates are very imprecise and conclusions are very uncertain.

Table 4 Rate Ratios (network estimates; 95%CI) for the outcome measure severe hypoglycemia (per person-year) for different diabetes management comparisons (adapted from Pease (2020a)

|

A) SMBG and CGM |

|||

|

Comparison* |

Rate Ratio (95%CI) |

Direct comparisons (number of studies) |

Indirect comparisons only |

|

Studies with same within study group insulin delivery modality |

|||

|

CSII+Calc versus CSII+CGM |

1.57 (0.57 to 4.33) |

2 |

|

|

CSII+SMBG versus CSII+CGM |

0.69 (0.32 to 1.46) |

|

x |

|

MDI+SMBG versus CSII+CGM |

0.90 (0.48 to 1.67) |

4 |

|

|

MDI+Calc versus CSII+CGM |

1.51 (0.63 to 3.62) |

|

x |

|

CSII+Calc versus MDI+CGM |

3.45 (0.79 to 14.29) |

|

x |

|

CSII+SMBG versus MDI+CGM |

1.52 (0.42 to 5.56) |

|

x |

|

MDI+Calc versus MDI+CGM |

3.33 (0.85 to 12.99) |

|

x |

|

MDI+SMBG versus MDI+CGM |

1.97 (0.59 to 6.58) |

3 |

|

|

Studies with different within study group insulin delivery modality |

|||

|

SMBG versus CGM |

Not reported |

2 |

x |

|

B) FGM and SMBG |

|||

|

Comparison |

Rate Ratio (95%CI) |

Direct comparisons (number of studies) |

Indirect comparisons only |

|

Studies with same within study group insulin delivery modality |

|||

|

MDI+FGM versus CSII+Calc |

0.21 (0.02 to 1.80) |

|

x |

|

MDI+FGM versus CSII+SMBG |

0.48 (0.06 to 3.65) |

|

x |

|

MDI+FGM versus MDI+SMBG |

0.37 (0.05 to 2.63) |

1 |

|

|

MDI+FGM versus MDI+Calc |

0.22 (0.03 to 1.74) |

|

x |

|

Studies with different within study group insulin delivery modality |

|||

|

FGM versus SMBG |

Not reported |

1 |

x |

|

C) FGM and CGM |

|||

|

Comparison |

Rate Ratio (95%CI) |

Direct comparisons (number of studies) |

Indirect comparisons only |

|

Studies with same within study group insulin delivery modality |

|||

|

MDI+FGM versus CSII+CGM |

0.33 (0.04 to 2.61) |

|

x |

|

MDI+FGM versus MDI+CGM |

0.72 (0.08 to 6.25) |

1 |

|

|

Studies with different within study group insulin delivery modality |

|||

|

FGM versus CGM |

Not reported |

|

x |

|

D) CGM/FGM and integrated |

|||

|

Comparison |

Rate Ratio (95%CI) |

Direct comparisons (number of studies) |

Indirect comparisons only |

|

Studies with same within study group insulin delivery modality |

|||

|

CSII+CGM versus integrated |

1.32 (0.23 to 7.69) |

3 |

|

|

MDI+CGM versus integrated |

0.60 (0.07 to 5.03) |

|

x |

|

MDI+FGM versus integrated |

0.43 (0.03 to 6.15) |

Not reported |

Not reported |

CGM: continuous glucose monitoring; CSII: continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion; FGM: flash glucose monitoring; MDI: multiple daily injections; SMBG: self-monitoring of blood glucose. *The intervention which is mentioned secondly is the reference category, for example of the comparison CSII+Calc versus CSII+CGM, CSII+CGM is the reference category. None of the values are statistically significant (p<0.05)

Ranking of technologies

Similar ranking values were found for MDI with FGM or CGM (SUCRA=80 and 78, respectively), CSII with SMBG (SUCRA=67), as well as integrated CSII and CGM systems (SUCRA=53.7).

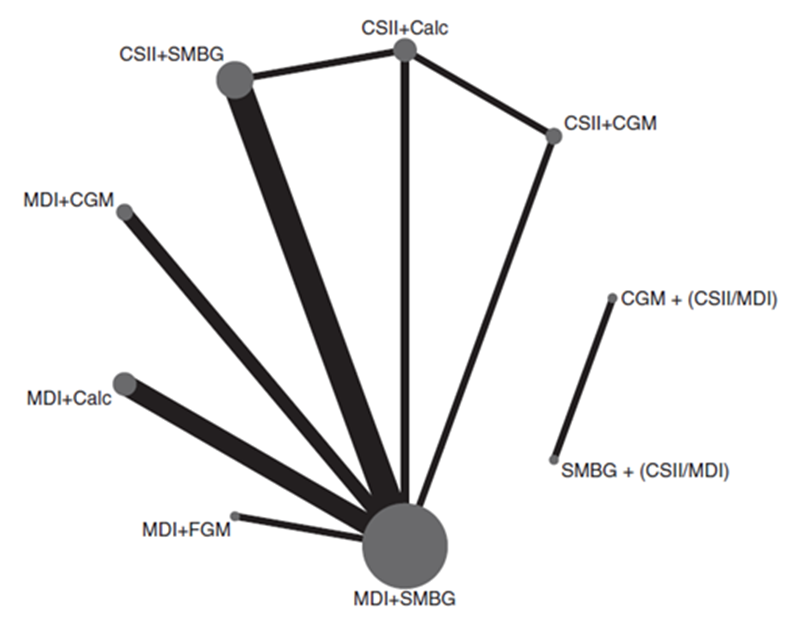

Quality of life (crucial outcome measure)

Pease (2020a) included 14 studies which reported on health-related quality of life, as measured with a validated tool (for example Diabetes Quality of Life measure (DQOL), SF-36, SF-12). The network plots are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Network plots of diabetes management comparisons for the outcome quality of life, stratified for studies with same versus different within study group insulin delivery modality. The networks consist of seven and two interventions (nodes) respectively, a total of 14 RCTS (1,499 participants). Details on number of RCTs and participants are not reported specifically for the same versus different within-study insulin delivery modalities. The size of each circle and the width of each line is proportional to the number of participants randomized to each intervention and the number of trials. Calc: bolus calculator; CGM: continuous glucose monitoring; CSII: continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion; FGM: flash glucose monitoring; MDI: multiple daily injections; SMBG: self-monitoring of blood glucose

Results of network meta-analysis for the outcome measure quality of life for the different comparison categories (SMBG versus CGM, FGM versus SMBG, FGM versus CGM and CGM/FGM versus integrated systems) are reported in Table 5. Pease (2020a) estimated standardized mean difference, after correction for the direction of the different QoL scoring instruments. Higher scores indicate higher levels of reported quality of life. Pease (2020a) reported standardized mean difference (95%CI) for quality of life for several comparisons within the four comparison categories and stratified for studies with same versus different within study group insulin delivery modalities. Since those comparisons are not independent from each other, it was not valid to pool the data.

Most of the included trials had high risk of performance bias, since blinding of the participants and the clinicians was lacking. This might have had a large impact on the results on the outcome measure quality of life. Besides, in part of the trials the method of randomisation (sequence generation and/or allocation concealment) was unclear. Finally, bias may result from the fact that the network meta-analysis combined results from different QoL instruments. There is no consensus on the most accurate or representative tool to assess QoL, and the quality of life of the participants at the start of the trials is likely to be high i.e. there may be little room for improvement in QoL scores.

SMBG versus CGM