Casemanagement bij dementie

Uitgangsvraag

Is casemanagement aan te bevelen voor patiënten met vastgestelde dementie?

Deze uitgangsvraag bevat de volgende onderliggende vragen:

- Wat is het effect van casemanagement op neuropsychiatrische symptomen, kwaliteit van leven en ADL-functioneren bij patiënten met vastgestelde dementie?

- Wat is het effect van casemanagement op mentaal welbevinden, gevoelens van stress en sociale uitkomsten bij mantelzorgers van patiënten met vastgestelde dementie?

Aanbeveling

Adviseer het inschakelen van casemanagement bij personen bij wie dementie is vastgesteld.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Uitkomsten gemeten bij de patiënt:

Er is niet aangetoond in de beschikbare literatuur dat case-management bijdraagt aan het verbeteren van kwaliteit van leven van patiënten. Wel draagt case-management mogelijk bij aan een lager risico op institutionalisering in het eerste jaar van de interventie. Ook draagt case-management mogelijk bij aan een vermindering van neuropsychiatrische symptomen. Bij de interpretatie van beide effecten moeten we voorzichtig zijn, omdat de verschillen klein zijn en de betrouwbaarheidsintervallen breed en overlappen met zowel de grenswaarde voor klinische relevantie als met de grenswaarde voor geen verschil.

Uitkomsten gemeten bij de mantelzorger:

Er is geen overtuigend bewijs dat case-management een substantiële bijdrage levert aan het verminderen van ervaren belasting van de mantelzorger. Hoewel het gevonden verschil statistisch significant is, is het niet klinisch relevant. Ook wat betreft sociaal welbevinden, sociale uitkomsten en kwaliteit van leven werden geen klinisch relevante effecten gevonden.

Het is van belang om te vermelden dat bij de zoekopdracht geen RCT’s zijn gevonden die de Nederlandse situatie betreffen. De buitenlandse studies zijn in algemene zin weliswaar deels van toepassing op de Nederlandse situatie, maar de uitkomsten ervan kunnen niet zomaar geëxtrapoleerd worden naar de Nederlandse situatie omdat er verschillen zijn in ondermeer de vorm waarin zorg wordt aangeboden, de setting waarin deze plaatsvindt, en de kosten en het totale gezondheidszorgsysteem. Hierdoor is geen eenduidige vertaling te maken van de bevindingen uit de gevonden buitenlandse studies naar de Nederlandse situatie.

Er is wel één Nederlandse prospectieve cohortstudie die in dit kader relevante informatie oplevert (MacNeil Vroomen (2015). De COMPAS studie is een prospectieve, observationele, gecontroleerde cohortstudie waarin case-management-modellen (intensieve casemanagement model (ICMM) verzorgd door 1 gespecialiseerde organisatie (n= 234) en het netwerkmodel (Linkage model, LM) met meerder betrokken organisaties (n =214) vergeleken zijn met gebruikelijke zorg (n=73). Thuiswonende personen met dementie en hun primaire mantelzorger werden gerekruteerd via geheugenpoliklinieken, Alzheimercentra en huisartsenpraktijken en gedurende twee jaar gevolgd. Er werd geen verandering gevonden in de primaire uitkomstmaat neuropsychiatrische symptomen (NPI) bij patiënten of in psychische gezondheid (GHQ-12) bij de mantelzorgers. Analyse van secundaire uitkomstmaten lieten betere scores op kwaliteit van leven zien bij de mantelzorgers voor ICMM vergeleken met LM, en op een schaal die het totaal aantal zorgbehoeftes per patiënt meet (CANE), was de score significant minder voor ICMM vergeleken met gebruikelijke zorg.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten /mantelzorgers

Het is niet precies bekend hoeveel mensen met dementie en hun mantelzorgers in Nederland gebruik maken van casemanagement. Een enquête uitgevoerd door Nivel bij 4459 mantelzorgers liet zien dat van de thuiswonende mensen met dementie 81% gebruik maakt van casemanagement; dit percentage is hoog maar waarschijnlijk onderhevig aan selectiebias (Dementie Monitor Mantelzorg, 2018). Casemanagement werd in deze groep hooggewaardeerd (8.1, SD 2.0). Casemanagement werd hierbij als de meest noodzakelijke vorm van ondersteuning beschouwd. Voor alleenstaande patiënten, zonder mantelzorger, scoorde hulp bij persoonlijke verzorging het hoogst.

Op basis van deze bevindingen zou voorzichtig geconcludeerd kunnen worden dat casemanagement voorziet in breed gedeelde behoefte.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

In de COMPAS-studie is ook een kosten en een kosten-effectiviteitsanalyse gedaan. Er is onderzocht of er verschillen zijn in de gemaakte kosten tussen de twee onderzochte casemanagement-groepen en de controlegroep op basis van een kostendagboek.

Een Quality-Adjusted Life-Year (QALY)-score werd berekend op basis van de EuroQol (EQ-5D-3L) voor zowel de patiënt als de mantelzorger. De kosten van de mantelzorg en de dagbesteding bleken significant lager te zijn bij het geïntegreerde zorgmodel, in vergelijking met het netwerkmodel en de controlegroep. Een voorlopige conclusie van de auteurs is dat het geïntegreerde zorgmodel mogelijk kosteneffectief is in vergelijking met het netwerkmodel en de controlegroep.

Andere (Nederlandse) studies op het gebied van kosteneffectiviteit ontbreken en de werkgroep is van mening dat er op dit moment geen uitspraak gedaan kan worden ten aanzien van kosteneffectiviteit van casemanagement bij dementie.

Aanvaardbaarheid voor de overige relevante stakeholders

Er lijken geen bezwaren te bestaan tegen casemanagement bij dementie vanuit andere stakeholders betrokken bij deze groep patiënten. De herziene NHG-standaard Dementie (2020) laat zich ook voorzichtig positief uit over het inschakelen van casemanagement bij dementie.

Haalbaarheid en implementatie

Casemanagement bij dementie wordt in Nederland al breed aangeboden (en vergoed) en kan bij thuiswonende patiënten en hun mantelzorger als reguliere zorg worden beschouwd. Door de betrokken professionals in de eerste en tweede lijn wordt deze zorg als waardevol ervaren (‘meerwaarde’). Het is van belang om patiënten met dementie en hun mantelzorgers goed te informeren over het bestaan van deze zorg.

Optimalisatie van de ketenzorg rondom dementie is essentieel; factoren die verbeterd kunnen worden zijn communicatie tussen eerste en tweede lijn en de praktijkvariatie in dementiezorg. Er zijn verschillen in de manier waarop casemanagement wordt aangeboden (tussen en soms ook binnen regio’s) wat op zichzelf niet verkeerd is, maar de kwaliteit en breedte waarin de zorg wordt aangeboden dient wel vergelijkbaar te zijn. De beroepsvereniging voor verpleegkundigen V&VN heeft hier reeds actie op ondernomen en in 2017 functie-eisen omschreven.

Rationale

Casemanagement dementie wordt al wijdverbreid ingezet in Nederland. Er is echter geen overtuigend wetenschappelijk bewijs gevonden dat het inzetten van casemanagement bij dementie ‘gunstige effecten heeft op neuropsychiatrische symptomen, kwaliteit van leven en ADL functioneren van de patiënt met dementie, of op het geestelijk of sociaal welbevinden van hun mantelzorgers’. Dit is vooral te wijten aan het feit dat kwalitatief goede gecontroleerde onderzoeken, vooral de Nederlandse situatie betreffend, ontbreken. Ook is de definitie van casemanagement in de diverse studies nogal uiteenlopend wat maakt dat deze niet goed met elkaar kunnen worden vergeleken. Daarom komt de huidige aanbeveling deels voort uit ‘expert opinion’, waarbij de werkgroep van mening is dat het aanbeveling verdient om casemanagement in te schakelen bij personen waarbij dementie is vastgesteld. Hiervoor was de positieve ervaring van experts met casemanagement op persoonsgerichte uitkomstmaten van de patiënt, belasting van mantelzorgers, en coordinatie van zorg doorslaggevend.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Casemanagement wordt in de Zorgstandaard Dementie (2020) gedefinieerd als:

“het systematisch aanbieden van gecoördineerde begeleiding, zorg en ondersteuning als deel van de behandeling door een vaste professional; deze professional maakt deel uit van een (multidisciplinair) samenwerkingsverband gericht op thuiswonende personen met dementie en hun mantelzorgers; de casemanagement professional is betrokken vanaf de start van het diagnostisch traject, zo snel mogelijk als de persoon met dementie wil, zonder onnodige wachttijden of wachtlijsten; het streven is om casemanagement in te schakelen op geleide van de individuele behoefte van de mens met dementie en mantelzorger(s). Deze behoefte kan in tijd variëren; casemanagement dementie eindigt na opname in een woonvorm voor mensen met dementie (zoals in verpleeghuis) door middel van warme overdracht; de casemanagement professional biedt desgewenst nazorg aan de mantelzorger(s) na overlijden van de persoon met dementie.”

Op basis van ruime ervaring in de klinische praktijk onderschrijft de werkgroep het belang van casemanagement. Er blijkt grote variatie te bestaan in mate van (regionale) beschikbaarheid, invulling en continuïteit van casemanagement. De werkgroep wil daarom, indien mogelijk, een evidence-based aanbeveling hierover in de richtlijn opnemen. Een uitdaging hierin vormt het operationaliseren van casemanagement; aan casemanagement wordt binnen en buiten Nederland op verschillende manieren invulling gegeven.

Uitgangspunt voor de zoekvraag is of gespecialiseerde zorg in de eerstelijn toegevoegde waarde heeft op belangrijke uitkomstmaten voor patiënten en/of hun mantelzorgers. Belangrijkste criterium voor casemanagement is een speciaal getrainde zorgverlener die regelmatig contact heeft met patiënt en/of mantelzorger en daadwerkelijk ondersteuning biedt bij omgaan met dementie in de zin van psychosociale begeleiding, ziekte-monitoring en zorgcoördinatie. Ook heeft de casemanager een rol bij het signaleren van overbelasting bij de mantelzorger en het vergroten van draagvlak voor informele zorg. Praktische ondersteuning zoals huishoudelijke hulp of verpleegkundige handelingen in de thuissituatie vallen hier niet onder.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

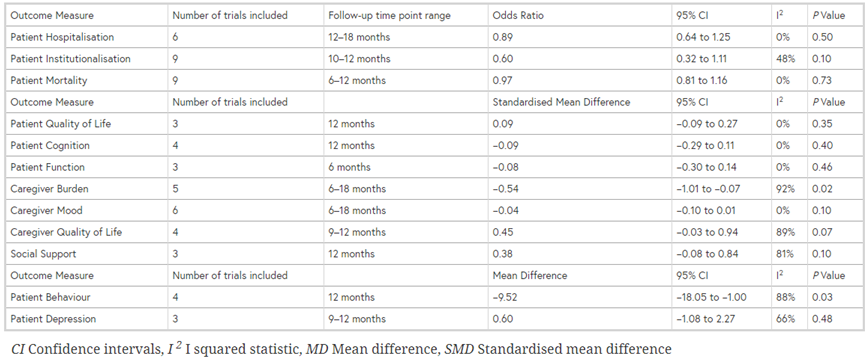

Patient quality of life

|

Moderate GRADE |

It is likely that coordinated dementia care does not improve quality of life of patients living with dementia compared with usual care.

Sources: (Backhouse, 2017; Thyrian, 2017) |

Institutionalization

|

Moderate GRADE |

It is likely that coordinated dementia care lowers the risk of institutionalization of patients living with dementia compared with usual care.

Sources: (Backhouse, 2017; Fortinsky, 2009; Mittelman, 2006; Mohide, 1990; Thyrian, 2017; Wright, 2001) |

Occurrence of crisis situations

|

- GRADE |

No studies were found that compared dementia care coordination with usual care in patients living with dementia on the outcome occurrence of crisis situations. |

Neuropsychiatric symptoms

|

Low GRADE |

Coordinated dementia care may reduce neuropsychiatric symptoms of patients living with dementia compared with usual care.

Sources: (Backhouse, 2017; Thyrian, 2017) |

Caregiver burden

|

Low GRADE |

Coordinated dementia care may reduce caregiver burden of carers of patients living with dementia compared with usual care.

Sources: (Backhouse, 2017; Fortinsky, 2009; Mohide, 1990; Thyrian, 2017) |

Caregiver mental wellbeing

|

Moderate GRADE |

Coordinated dementia care likely results in little to no difference in mental wellbeing of carers of patients living with dementia compared with usual care.

Sources: (Backhouse, 2017; Fortinsky, 2009; Mohide, 1990) |

Caregiver social outcomes

|

Low GRADE |

Coordinated dementia care may have little effect on social outcomes of carers of patients living with dementia compared with usual care.

Sources: (Backhouse, 2017) |

Caregiver quality of life

|

Low GRADE |

Coordinated care may have little effect on quality of life of carers of patients living with dementia compared to usual care.

Sources: (Backhouse, 2017) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

The systematic review by Backhouse (2017) evaluates community-based interventions aimed at coordinating care in patients living with dementia. The review included 14 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared interventions delivered by a single professional who took responsibility for the provision and management of care, including facilitating and/or coordinating care through assessments and proactive follow-up. Interventions were delivered by social workers, nurse care manager or occupational therapist in community or primary care teams. The interventions were compared with usual care, standard community treatment or alternative interventions or waiting-list controls. In total, 5386 patients were in the intervention group and 4986 patients were in the control group. The follow-up ranged from 6 to 36 months. The following outcomes were included: patient quality of life, institutionalization, neuropsychiatric symptoms (behavior, depression); and caregiver burden, mental wellbeing, social support and quality of life.

In the randomized controlled trial by Thyrian (2017), the ‘DemTect’ dementia care management procedure was compared with usual care in community-dwelling older patients (aged > 70 years) living with dementia. The 291 patients in the intervention group (mean age 80.6 ±5.7 years, 39% male) received an in-depth assessment conducted by nurses with specific dementia care qualifications. Based on the assessment, a computer program generated an individual intervention task list which the nurse discussed and finalized in weekly interdisciplinary case conferences with a nurse scientist, neurologist/psychiatrist, psychologist and pharmacist. In collaboration with the GP, a personalized treatment plan was established. Patients were visited at home by the nurse 6 times during the first 6 months and the nurse carried out the task list in cooperation with the caregiver, GP and health care and social services professionals. During the subsequent 6 months, the nurse monitored completion of all intervention tasks. The 116 patients in the control group (mean age 79.8 ±5.0 years, 40% male) received care as usual. At 12 months, the following outcomes were measured: patients behavioural and psychological symptoms, quality of life and institutionalization, and caregiver burden.

In the randomized controlled trial by Fortinsky (2009), individualized dementia care consultation was compared with educational and community resource information in patients diagnosed with dementia living in de community and their family caregivers. Both the intervention group (n=54, mean age 64.8 ±14.8 years, 63% female) and the control group (n=30, mean age 57.7 ±16.4 years, 80% female) received educational materials. The intervention group additionally received care plans, which included action steps, key information about the clinical course of the disease, legal and financial planning issues, family support groups, educational programs, adult day care and respite care services. Caregivers were visited monthly by the care consultants for 12 months. Care plans were tailored to concerns of the caregiver. After 12 months, between-group differences were examined for the outcomes nursing home admittance of the patient, caregiver burden and caregiver depressive symptoms.

In the randomized controlled trial by Mittelman (2006), caregiver counseling and support was compared with usual care in spouses of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Spouses were included only if they lived with the patient and they or the patient had at least one relative living in the metropolitan area. The intervention group (n=203, mean age 71.5 ±8.6 years, 45% male) received two individual and four family counseling sessions tailored to the caregiver’s situation, weekly support groups and ad hoc telephone counseling. The control group (n=203, mean age 71.2 ±9.3 years, 34% male) received usual care. After 12 months, the groups were compared on risk of nursing home admittance.

In the randomized controlled trial by Wright (2001), caregiver education and counseling were compared with no education or counseling in caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Caregivers were recruited during hospital admission of the patient; caregivers included only if they lived in the same household as the patient and lived within 80 mile of the hospital. The Intervention group (n=68, mean age 59 (range 19 to 85) years, 24% male) received 3 home visits and 2 phone calls from a gerontological or mental health nurse specialist. The visits took place 1 to 2 weeks, 5-6 weeks and 12 weeks after discharge; the phone calls were made 6 and 12 months after discharge. Based on identified troublesome behaviours of the patient, caregivers learnt about strategies for handling such behaviours. Patient’s medication was monitored and side effects were noted. Requirements of dosage adjustments were communicated with the patient’s physician. Caregivers emotional and physical health were addressed with supportive counseling. The control group (n=25, mean age 59 (19 to 85) years, 24% male) received phone calls on the same time schedule, but for the purpose of data collection only. No education, counseling or medication monitoring was provided. After 12 months, the groups were compared on neuropsychological symptoms (agitation), and caregiver stress and depression.

In the randomized controlled trial by Mohide (1990), caregiver support was compared with conventional community nursing care in caregiver-patient dyads. Dyads were eligible if the carer lived with the demented relative, were the principle family carer and spoke English, and the patient had a medical diagnosis of primary degenerative, multi-infarct or mixed dementia, were moderately to severely impaired, did not suffer from a serious concomitant illness, were not likely to be placed in long term care during the course of the study. The intervention group (n=30, mean age 66.1 ±13.5 years, 30% male) received a set of supportive interventions directed at helping the caregivers enhance caregiving competence and achieve a sense of control in their roles as caregivers. Nurses visited the caregivers, initially visits were weekly but adjusted upward or downward based on need. Caregiver problems were assessed. Caregivers were encouraged to seek medical attention for neglected health problems. The nurses consulted with the family physician if the carers health was judged to be unstable. The carers received dementia and caregiving education. The control group (n=30, mean age 69.4 ±8.6 years, 27% male) received conventional community nursing care focused on care of the demented patient rather than care of the caregiver. After 6 months, the groups were compared on time to institutionalization and caregiver depression, anxiety and quality of life.

Results

Patient quality of life

Three studies in the review by Backhouse (2017) and one additional RCT (Thyrian, 2017) compared coordinated care with a control group on patient quality of life. No information was available in the review on how quality of life was measured (Backhouse, 2017). Thyrian (2017) used the Quality of Life in Alzheimer Disease (QoL-AD) to measure patient quality of life.

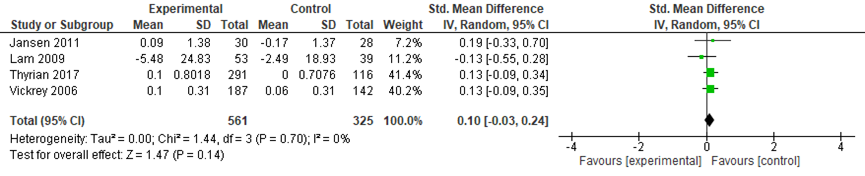

The meta-analysis included data from 583 participants in the intervention groups and 345 participants in the control groups. A small and not significant difference was found between the groups on patient quality of life in favor of the control group (standardized mean difference (SMD): 0.10, 95% confidence interval (CI): -0.03 to 0.24, random effects model) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Comparing coordinated care with a control group: patient quality of life

Institutionalization

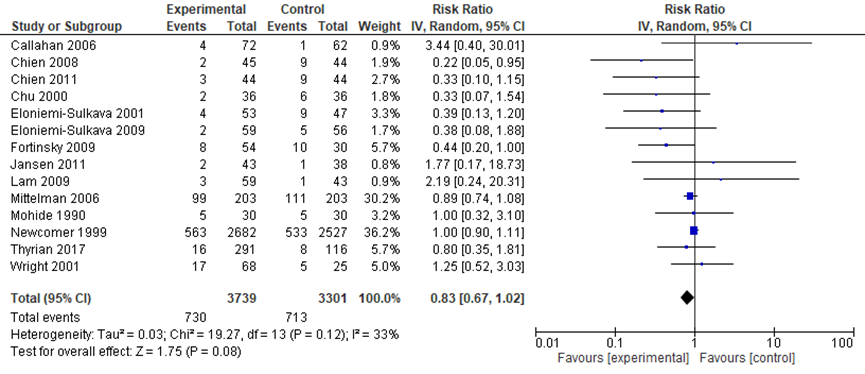

Nine studies in the review by Backhouse (2017) and five additional RCTs (Thyrian, 2017; Fortinsky, 2009; Mittelman, 2006; Wright, 2001; Mohide, 1990) compared coordinated care with a control group on institutionalization after 6 to 12 months (most studies reported 12 months follow-up). The meta-analysis included data from 3739 participants in the intervention groups and 3301 participants in the control groups. A substantial but not statistically significant reduction in odds of institutionalization was found in the intervention group relative to the control group (Relative risk: 0.83; 95%CI: 0.67 to 1.02; I2=33%; random effects model) (Figure 2). The authors suggest there might be some publication bias (suggesting that smaller studies with negative results might not be published).

Figure 2 Comparing coordinated care with a control group: risk of institutionalization

Occurrence of crisis situations

No studies were found that compared coordinated care with a control group on the outcome occurrence of crisis situations in patients with dementia.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms

Four studies in the review by Backhouse (2017) compared coordinated care with a control group on patient behavior. The review provided no information on which aspects of behavior were measured and how. Thyrian (2017) compared dementia care management with usual care on neuropsychiatric symptoms measured with the Neuropsychiatric Inventory, an interview by proxy on 12 dimensions of neuropsychiatric behaviors. Wright (2001) compared caregiver education and counseling (n=68) with no intervention (n=25) on agitation. Agitation was measured with the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (range 30 to 210, higher scores indicate more agitation). However, insufficient data were presented to be able to incorporate the data from Wright (2001) into the meta-analysis. These results are presented separately.

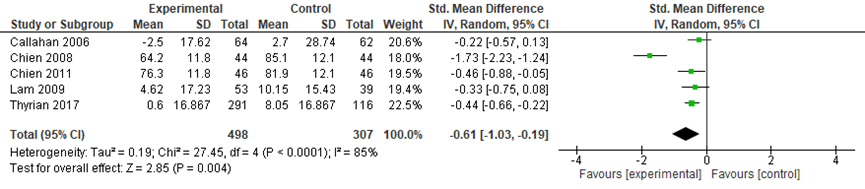

The meta-analysis included data from 408 participants in the intervention groups and 307 participants in the control groups. Across the five studies, a medium size and statistically significant effect was found in favor of the intervention groups (SMD: -0.61, 95%CI: -1.03 to -0.19, random effects model) (Figure 3).

Wright (2001) measured agitation at five timepoints during one year. Both groups showed a decline in agitation from hospital admission (baseline) to 1 to 2 weeks post discharge (intervention group reduced from 67.5 to 56; control group reduced from 76 to 59), followed by a stable pattern in the intervention group and a slight increase in the control group (from 60 to 65 points). However, the differences between the groups over time were not statistically significant (p-value for group×time interaction: 0.52) (Wright, 2001).

Figure 3 Comparing coordinated care with a control group: neuropsychiatric symptoms

Caregiver burden

Five studies in the review by Backhouse (2017) and four additional RCTs compared coordinated care with a control group on caregiver burden (Thyrian, 2017; Fortinsky, 2009; Wright, 2001; Mohide, 1990). The review provided no information on caregiver burden was measured. Thyrian (2017) measured caregiver burden using the Berlin Inventory of Caregivers’ Burden with Dementia Patients (BIZA-D), an inventory that assesses subjective and objective burden. Fortinsky (2009) measured caregiver burden using the Revised Caregiver Burden Scale. Mohide (1990) measured caregiver burden using a scale developed for the purpose of this study, which asked about extent to which up to 10 problems occurred and bothered them (range 0 to 40, higher scores indicate a higher burden). Wright (2001) measured caregiver burden using the Caregiving Hassle Scale, which asks about the presence or absence and of cognitive changes, disruptive behaviours, difficulties with daily activities in the patient and problems with the support network and how much of these problems bothered them (range 0 to 123, higher scores indicate higher burden). Wright (2001) presented insufficient data for these to be incorporated in the meta-analysis. These results are presented separately.

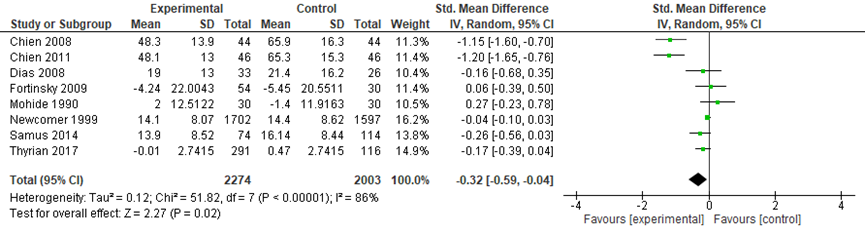

The meta-analysis included data from 2274 participants in the intervention groups and 2003 participants in the control groups. Across the eight studies, a small but statistically significant effect was found in favor of the intervention groups (SMD: -0.32, 95%CI: -0.59 to -0.04, random effects model) (Figure 4).

Wright (2001) measured caregiver burden at five timepoints during one year. Overall, both groups showed a decrease in caregiver burden over time (both groups reduced from approximately 28 points at baseline to 22 points at 12 months). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups over time (p-value for group × time interaction: 0.43) (Wright, 2001).

Figure 4 Comparing coordinated care with a control group: caregiver burden

Caregiver mental wellbeing

Six studies in the review by Backhouse (2017) and three additional RCTs compared coordinated care with a control group on caregiver mental wellbeing (Fortinsky, 2009; Wright, 2001; Mohide, 1990). No information was available in the review on how caregiver mood was measured (Backhouse, 2017). Fortinsky (2009), Wright (2001) and Mohide (1990) measured caregiver depression using the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Wright (2001) presented insufficient data for these to be incorporated in the meta-analysis. These results are presented separately.

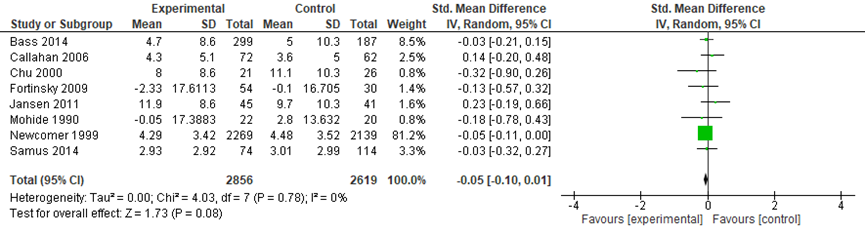

The meta-analysis included data from 2856 participants in the intervention groups and 2619 participants in the control groups. Across the eight studies, a small and not statistically significant effect was found in favor of the intervention groups (SMD: -0.05, 95%CI: -0.10 to 0.01, random effects model) (Figure 5).

Wright (2001) measured mental depression at five timepoints during one year. Depression scores were higher in the intervention group than in the control group throughout the study. Both groups showed a decrease in scores over time (intervention group: reduced from approximately 13 to 11 points, control group: reduced from approximately 10 to 8 points). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups over time (p-value for group × time interaction: 0.94) (Wright, 2001).

Figure 5 Comparing coordinated care with a control group: caregiver mental wellbeing

Caregiver social outcomes

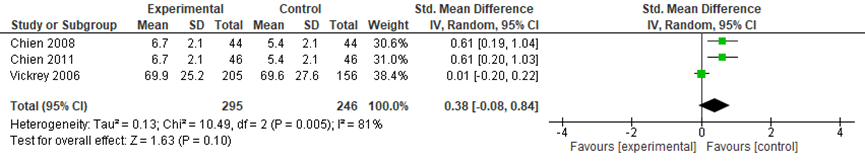

Three studies in the review by Backhouse (2017) compared coordinated care with a control group on social support. No information was available on how this outcome was measured. The meta-analysis included data from 295 participants in the intervention groups and 246 participants in the control groups. Across the three studies, a small and not statistically significant effect was found in favor of the control groups (SMD: 0.38, 95%CI: -0.08 to 0.84, random effects model) (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Comparing coordinated care with a control group: social support

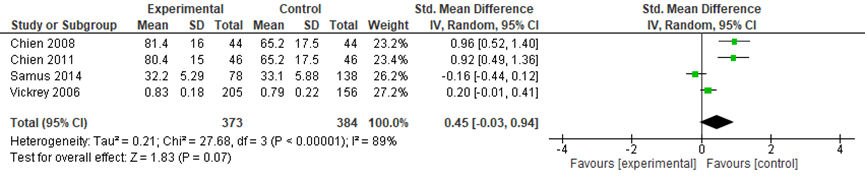

Caregiver quality of life

Four studies in the review by Backhouse (2017) compared coordinated care with a control group on caregiver quality of life. No information was available on how this outcome was measured. The meta-analysis included data from 373 participants in the intervention groups and 384 participants in the control groups. Across the four studies, a small and not statistically significant effect was found in favor of the control groups (SMD: 0.45, 95%CI: -0.03 to 0.94, random effects model) (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Comparing coordinated care with a control group: caregiver quality of life

Level of evidence of the literature

Patient quality of life

The evidence for the outcome patient quality of life was based on four randomized controlled trials. Therefore, the level of evidence started at ‘high’. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level, because of study limitations (one study lacked blinding of patients, care providers and assessors, this study was the largest of the four in terms of sample size). The level of evidence was therefore set at ‘moderate’.

Institutionalization

The evidence for the outcome institutionalization was based on 13 randomized controlled trials. Therefore, the level of evidence started at ‘high’. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level, because of imprecision: the confidence interval around the pooled relative risk included the cut-off point for minimal clinically important difference (> 5% reduction in institutionalizations) as well as 1. The level of evidence was therefore set at ‘moderate’.

Occurrence of crisis situations

The level of evidence for the outcome occurrence of crisis situations could not be graded as no studies were found that compared dementia care coordination with usual care on the outcome occurrence of crisis situations in people with dementia.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms

The evidence for the outcome neuropsychiatric symptoms was based on five randomized controlled trials. Therefore, the level of evidence started at ‘high’. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels, because of study limitations (risk of bias: one study lacked blinding of patients, care providers and assessors) and imprecision (the confidence interval around the pooled SMD included the cut-off point for minimal clinically important difference. The level of evidence was therefore set at ‘low’.

Caregiver burden

The evidence for the outcome caregiver burden was based on eight randomized controlled trials. Therefore, the level of evidence started at ‘high’. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels, because of study limitations (risk of bias: three studies lacked blinding of patients, care providers and assessors) and imprecision (the confidence interval around the pooled SMD included the cut-off point for minimal clinically important difference. The level of evidence was therefore set at ‘low’.

Caregiver mental wellbeing

The evidence for the outcome caregiver mental wellbeing was based on 8 randomized controlled trials. Therefore, the level of evidence started at ‘high’. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level, because of study limitations (risk of bias: 5 studies lacked blinding of patients, care providers and assessors). The level of evidence was therefore set at ‘moderate’.

Caregiver social outcomes

The evidence for the outcome ‘caregiver social outcomes’ was based on three randomized controlled trials. Therefore, the level of evidence started at ‘high’. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels, because of imprecision (the confidence interval around the pooled SMD included the cut-point for minimal clinically important difference (>5% reduction in institutionalizations) as well as 0) and because of heterogeneity of the trial results. The level of evidence was therefore set at ‘low’.

Caregiver quality of life

The evidence for the outcome ‘caregiver quality of life’ was based on three randomized controlled trials. Therefore, the level of evidence started at ‘high’. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels, because of imprecision (the confidence interval around the pooled SMD included the cut-point for minimal clinically important difference (>5% reduction in institutionalizations) as well as 0) and because of heterogeneity of the trial results. The level of evidence was therefore set at ‘low’.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following questions:

1. What is the efficacy of case management on neuropsychiatric symptoms, quality of life and independence in daily functioning of patients with established dementia?

P: patients diagnosed with dementia;

I: case management;

C: usual care, absence of case management;

O: quality of life, institutionalization, occurrence of crisis situations, neuropsychiatric symptoms.

2. What is the efficacy of case management on mental wellbeing, feelings of stress and social outcomes among caregivers of patients with established dementia?

P: caregivers of patients diagnosed with dementia;

I: case management;

C: usual care, absence of case management;

O: caregiver burden, mental wellbeing, social outcomes (loneliness, social activities, social network), quality of life, health costs;

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered quality of life for patients and caregiver burden as critical outcome measures for decision making; and institutionalization, occurrence of crisis situations and neuropsychiatric symptoms for patients and mental wellbeing, social outcomes and quality of life for caregivers as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group used the following definitions for minimal clinically important difference in the outcomes:

- Caregiver burden: standardized mean difference (SMD)>0.5*.

- Patient quality of life: SMD>0.5*.

- Neuropsychological symptoms: SMD>0.5.

- Institutionalization: > 5% (absolute risk) reduction in nursing home admissions during the first year of follow-up.

- Crisis situations: > 5% reduction in events during the first year of follow-up.

* Note: the cut-off point of SMD>0.5 was chosen for continuous outcomes that were measured with different scales across the studies. This cut-off point was based on a commonly used cut-off for a medium effect size.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 13 March 2019. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. One search was performed for the two sub-questions. The systematic literature search resulted in 344 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: randomized controlled trials in which case management was compared with the absence of case management for either patients or caregivers. 54 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 52 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 2 studies were included (Backhouse, 2017 (systematic review) and Thyrian 2017 (RCT)). Four additional studies Fortinsky, 2009; Mittelman, 2006; Wright, 2001; Mohide, 1990) were selected from (otherwise excluded) systematic reviews.

Results

Six studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Alzheimer Nederland, Vilans. Zorgstandaard dementie. 2020.

- Backhouse, A., Ukoumunne, O. C., Richards, D. A., McCabe, R., Watkins, R., & Dickens, C. (2017). The effectiveness of community-based coordinating interventions in dementia care: a meta-analysis and subgroup analysis of intervention components. BMC health services research, 17(1), 717.

- Fortinsky, R. H., Kulldorff, M., Kleppinger, A., & Kenyon-Pesce, L. (2009). Dementia care consultation for family caregivers: collaborative model linking an Alzheimer's association chapter with primary care physicians. Aging and Mental Health, 13(2), 162-170. doi: 10.1080/13607860902746160.

- MacNeil Vroomen, J. M., Bosmans, J. E., van de Ven, P. M., Joling, K. J., van Mierlo, L. D., Meiland, F. J., ... & de Rooij, S. E. (2015). Community-dwelling patients with dementia and their informal caregivers with and without case management: 2-year outcomes of a pragmatic trial. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 16(9), 800.e1-800.e8.

- Mittelman, M. S., Haley, W. E., Clay, O. J., & Roth, D. L. (2006). Improving caregiver well-being delays nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease. Neurology, 67(9), 1592-1599. PMID: 17101889 DOI: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000242727.81172.91.

- Mohide, E. A., Pringle, D. M., Streiner, D. L., Gilbert, J. R., Muir, G., & Tew, M. (1990). A randomized trial of family caregiver support in the home management of dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 38(4), 446-454. PMID: 2184186 DOI: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb03544.x.

- Dieleman-Bij de Vaate, A.J.M., Eizenga, W.H., Lunter-Driever, P.G.M., Moll van Charante, E.P., Perry, M., Schep-Akkerman, A., Smit, B.S.J., Starmans, R., Verlaan-Snieders, M.N.E., Van der Weele, G.M. NHG-standaard Dementie, versie 5.0, april 2020. https://richtlijnen.nhg.org/standaarden/dementie

- Thyrian, J. R., Hertel, J., Wucherer, D., Eichler, T., Michalowsky, B., Dreier-Wolfgramm, A., ... & Hoffmann, W. (2017). Effectiveness and safety of dementia care management in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA psychiatry, 74(10), 996-1004. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2124.

- Wright, L. K., Litaker, M., Laraia, M. T., & DeAndrade, S. (2001). Continuum of care for Alzheimer's disease: a nurse education and counseling program. Issues in mental health nursing, 22(3), 231-252. PMID: 11885210 DOI: 10.1080/01612840152053084.

Evidence tabellen

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea, 2007; BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Mohe, 2009; PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

Research questions:

- What is the efficacy of case management on neuropsychiatric symptoms, quality of life and independence in daily functioning of patients with established dementia?

- What is the efficacy of case management on mental wellbeing, feelings of stress and social outcomes among caregivers of patients with established dementia?

|

Study

|

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/not applicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Backhouse, 2017 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Research questions:

- What is the efficacy of case management on neuropsychiatric symptoms, quality of life and independent functioning of patients with established dementia?

- What is the efficacy of case management on mental wellbeing, feelings of stress and social outcomes among informal caregivers of patients with establishes dementia?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Backhouse, 2017

Study to explore the effectiveness of coordinating interventions in dementia care. Focus on both, patient and caregevier |

Study design: SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to April 2017

A: Bass, 2003 B: Bass, 2014 C: Callahan, 2006 D: Chien, 2008 E: Chien, 2011 F: Chu, 2000 G: Dias, 2008 H: Eloniemi-Sulkava, 2001 I: Eloniemi-Sulkava, 2009 J: Jansen, 2011 K: Lam, 2009 L: Newcomer, 1999 M: Samus, 2014 N: Vickrey, 2006

Setting and Country: UK

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: The SR was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South West Peninsula. No conflict of interest declared |

Inclusion criteria SR: - RCTs of community based interventions coordinating care in dementia - participants with dementia diagnosis of any type, living at home, no restrictions on age or gender. - interventions that were delivered by a single, identified professional who took responsibility for the provision and management of care. The main focus of their role was described in the study report as planning, facilitating and/or coordinating care through assessments and proactive follow-ups. - studies of interventions that were based in the community

Exclusion criteria SR: - Non-randomised and/or quasi-experimental studies - individuals who did not have a formal diagnosis of dementia - studies that focused solely on informal caregivers of individuals with dementia which did not include a focus on increased care coordination or improved outcomes for individuals with dementia. - studies based in hospitals or nursing/residential homes

14 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N Intervention/Control A: 94/63 B: 316/192 C: 84/69 D: 46/46 E: 44/44 F: 37/38 G: 41/40 H: 53/47 I: 63/62 J: 54/45 K: 59/43 L: 4151/3944 M: 106/183 N: 238/170

Country: A: USA B: USA C: USA D: China E: China F: Canada G: India H: Finland I: Finland J: The Netherlands K: China L: USA M: USA N: USA |

Describe intervention:

Casemanager based in: A: community teams B: community and primary care teams C: primary care D: community teams E: community teams F: not reported G: community teams H: primary care I: not reported J: community teams K: community teams L: community and primary care teams M: community teams N: community teams

Professional background CM: A: social worker B: combi nurse/social worker C: nurse care manager D: nurse care manager E: nurse care manager F: social worker G: not reported H: nurse care manager I: nurse care manager J: nurse care manager K: occupational therapist L: combi nurse/social worker M: social worker N: social worker

CM training A: not reported B: yes C: no D: yes E: yes F: not reported G: yes H: yes I: yes J: yes K: not reported L: not reported M: yes N:yes

Intervention duration: A: 12 months B: 12 months C: 12 months D: 6 months E: 6 months F: 18 months G: 6 months H: 2 years I: 2 years J: 12 months K: 4 months L: NR M: 18 months N: 4-16 months

Contact type All trials used both face to face and telephone contact, except for A and B, who used telephone contact only |

Describe control:

Comparators included ‘usual care’, standard community treatment, alternative dementia care interventions or waiting-list controls. |

End-point of follow-up:

A: 12 months B: 12 months C: 18 months D: 12 months E: 18 months F: 18 months G: 6 months H: 2 years I: 2 years J: 12 months K: 12 months L: 36 months M: 18 months N: 18 months

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? NR

|

Outcome measures:

See * |

Risk of bias All of the trials were rated as high or moderate quality, and all had used appropriate methods for randomisation and were therefore free of selection bias (according to CASP appraisal).

there was substantial variability in the outcome measures recorded, the interventions and the reporting of the necessary intervention components which meant that only a small number of trials could be included in many of the meta-analyses and subgroup analyses, causing imprecision.

Publication bias was explored using funnel plots. Institutionalisation and mortality were the only two outcome measures to show a positive-result publication bias, the results of neither were statistically significant in the meta-analysis of overall intervention effect. Subgroup analysis for intervention components: - Interventions using a case manager with a nursing background showed a greater positive effect on caregiver quality of life compared to those that used other professional backgrounds (SMD = 0.94 versus 0.03, respectively; p < 0.001).

- Interventions that did not provide case managers with supervision showed greater effectiveness for reducing the percentage of patients that are institutionalised compared to those that provided supervision (OR = 0.27 versus 0.96 respectively; p = 0.02).

- There was weak evidence that interventions using a lower caseload for case managers had greater effectiveness for reducing the number of patients institutionalised compared to interventions using a higher caseload for case managers (OR = 0.23 versus 1.20 respectively; p = 0.08). - There was little evidence that the other intervention components modify treatment effects |

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

Research questions:

- What is the efficacy of case management on neuropsychiatric symptoms, quality of life and independent functioning of patients with established dementia?

- What is the efficacy of case management on mental wellbeing, feelings of stress and social outcomes among informal caregivers of patients with establishes dementia?

|

Study reference

|

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Thyrian, 2017 |

Cluster randomisation by GP. 1:1 randomization without stratification or Matching. |

Unlikely |

Likely |

Likely |

Likely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Fortinsky, 2009 |

Randomization was based on primary care physician practice site. |

Likely |

Likely |

Unlikely |

Likely |

Unlikely |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

|

Mittelman, 2006 |

Randomization by lottery |

Unlikely |

Likely |

Likely |

Likely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Mohide, 1990 |

Block randomization using a computer-generated random numbers table |

Unlikely |

Likely |

Likely |

Likely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Wright, 2001 |

Block sampling technique was used to allocate subjects to study conditions, in that one out of four subjects was randomly assigned to the control group and the other three to the experimental group. |

Unclear |

Likely |

Likely |

Likely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Evidence table for intervention studies

Research questions:

- What is the efficacy of case management on neuropsychiatric symptoms, quality of life and independent functioning of patients with established dementia?

- What is the efficacy of case management on mental wellbeing, feelings of stress and social outcomes among informal caregivers of patients with establishes dementia?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3 |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Thyrian, 2017

|

Type of study: RCT

Setting: home setting

Country: Germany

Funding and conflicts of interest: The study was performed in cooperation with and funded by the German Center of Neurodegenerative Diseases and the University Medicine of Greifswald.

Both funders participated in and funded the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review and approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

No conflict of interest was reported |

Inclusion criteria: ≥70 years, living at home, meeting criteria for dementia using DemTect procedure.

Exclusion criteria: -

N total at baseline: Intervention: 291 Control: 116

Important prognostic factors2:

Age (SD): I: 80.6 (5.7) C: 79.8 (5.0)

Sex: I: 39% M C: 40% M

Groups comparable at baseline? yes |

Dementia care management is a model of collaborative care, defined as a complex intervention aiming to provide optimal treatment and care for patients with dementia and support caregivers using a computer-assisted assessment determining a personalized array of intervention modules and subsequent success monitoring.

Dementia care management was targeted at the individual patient level and was conducted by 6 study nurses with dementia care–specific qualifications. The nurses conducted an in-depth assessment. Based on these data, the IMS generated an individual preliminary intervention task list, and the nurses discussed and finalized the task list in a weekly interdisciplinary case conference with a nursing scientist, a neurologist/psychiatrist, a psychologist, and a pharmacist. Afterwards, the list of intervention tasks was summarized in a semistandardized GP information letter. This letter was then discussed between the GP and nurse to establish an individual treatment plan.

During the first 6 months of the intervention period, the nurse conducted 6 home visits with an average duration of 1 hour, carrying out his or her standard intervention tasks in close cooperation with the caregiver, the GP, and health care and social service professionals. During the subsequent 6 months, the study nurse monitored the completion of all intervention tasks.Dementia care management was provided for 6 months at the homes of patients with dementia. |

Care as usual |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 46/337 Reasons: withdrew informed consent (n= 17), died (n= 22), changed region (n= 1), other (n= 6)

Control: 48/164 Reasons: withdrew informed consent (n= 31), died (n= 12), changed region (n= 1), other (n= 4)

|

Patients’ behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia b = −7.45 (−11.08 - −3.81) P < .001

Caregiver burden b = −0.50 (−1.09 - 0.08) P = .05

Pharmacotherapy with antidementia drugs: I: 114/291 (39.2%) C: 31/116 (26.7%) OR: 1.97 (0.99-3.94) P = .03

Quality of life: b = 0.02 (−0.09 - 0.05) P = .26

Potentially inappropriate medication I: 77/291 (26.5%) C: 19/116 (16.4%) OR: 1.86 (0.62 - 3.62) P = .97

Institutionalization According to secondary outcomes, we found no significant effect on patient’s institutionalization. |

|

|

Fortinsky, 2009 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: home setting

Country: USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funding for this project was provided by the Alzheimer’s association (IIRG-00-2383)

Conflicts of interest: NR

|

Inclusion criteria: Patients were eligible if they had a physician’s diagnosis of any type of irreversible dementia; resided in a home setting outside of a nursing home or assisted living facility; ambulated without constant human assistance; used the referring physician as their regular source of medical care; and had at least one identifiable family caregiver.

Caregivers were eligible if they were related to eligible patients; had primary or shared responsibility for patients’ health-related needs, and were known by the referring physician’s office staff.

Exclusion criteria: -

N total at baseline: Intervention: 54 Control: 30

Important prognostic factors2:

Caregivers Age (SD): I: 64.8 (14.8) C: 57.7 (16.4)

Caregivers Sex: I: 37% M C: 20% M

Groups comparable at baseline? No: Family caregivers in the intervention group were statistically significantly older than control group caregivers (65 years and 58 years, respectively, p= 0.05), primarily because intervention group caregivers were more likely than control group caregivers to be spouses (52 and 33%, respectively, p = 0.06). |

The intervention protocol called for the care consultant to have monthly contact for 12 months to: 1. determine which aspects of dementia symptoms and care responsibilities caused caregiver concerns (related to their relative or to caregiver thermselve) 2. discuss action steps to address caregiver concerns, and compose a written care plan.

The minimum care plan for all family caregivers included - the action steps that family caregivers should take to learn more about or use; - key information about the clinical course of the disease process; - legal and financial planning issues; - family support groups; - dementia educational programs offered by the chapter and other organizations; - adult day care services; - respite care services.

The care consultant’s initial and final meetings with family caregivers occurred in the home of the family caregiver and/or patient.

The care plan was shared with the patient’s physician for review with family caregiver and patient during subsequent office visits |

Control group family caregivers received only identical educational materials. |

Length of follow-up:12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: T2 interviews were completed with 75 caregivers; the remainder were lost to follow up or refused to complete T2 interviews.

Ascertainment of nursing home admission status at T2 was accomplished for 81 caregivers,

69 caregivers supplied sufficient T2 data to enable computation of all remaining dependent variables.

|

The nursing home admission rate was twice as high in the control group (n=10/30, or 33%) as in the intervention group (n=8/54, or 16%).

Spouse relationship (versus. other relationships) was entered as a covariate because of observed T1 differences between intervention and control groups on this variable. Results revealed that the adjusted odds ratio associated with intervention group membership was 0.40, indicating that people with dementia whose family caregivers were in the intervention group were 40% as likely as their control group counterparts to be admitted to a nursing home during the 12-month study period. This treatment group difference approached statistical significance (95% C.I. ¼ 0.14–1.18; p ¼ 0.10).

Results revealed no statistically significant treatment group-time interaction effects on any of the secondary outcome variables: - level of self-efficacy for managing dementia symptoms; - level of self-efficacy for accessing community support services; - caregiver burden; - depressive symptoms; - physical health symptoms |

Included in SR Tam-Tham 2013 |

|

Mittelman, 2006 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: home setting

Country: USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funded by the NIMH (R01 MH 42216) and the NIA (R01 AG14634). Additional funding was provided through the NYU Alzheimer’s Disease Center (P30-AG08051). W.E.H. was supported by the Florida AD Research Center (P50-AG025711).

The authors report no conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Spouses of subjects of Alzeheimer Disease. Caregivers were required to be living with the patient at baseline and they or the patient had to have at least one relative living in the metropolitan area.

Exclusion criteria: -

N total at baseline: Intervention: 203 Control: 203

Important prognostic factors2:

Age (SD): C: 71.15 (9.31)

Sex: I:45 % M C: 34% M

Groups comparable at baseline? No: imbalances were found between the treatment groups on four of the baseline variables: - gender - Global Deterioration Scale - memories and behavioral problems checklist - depressive symptoms. |

Enhanced counseling and support for spouse caregeviers: two individual and four family counseling sessions tailored to each caregiver’s specific situation, encouragement of weekly support group participation, and availability of ad hoc telephone counseling. |

Usual care |

Length of follow-up: assessment took place 4, 8 and 12 months after baseline and every 6 months thereafter. This continued until the caregiver became too ill to participate, died, or refused to continue in the study, or until 2 years after the death of the patient with AD.

Loss-to-follow-up: At least one follow-up interview was obtained from 396 of the 406 caregivers, and information on the primary endpoint for this analysis was available for all 406 subjects.

|

Nursing home placement No adjustment for covariates: caregivers in the intervention group were able to keep their spouses at home longer than caregivers in the usual care control group (HR= 0.714, X2= 5.88, p= 0.015).

The difference in the model-predicted median time from baseline to nursing home placement for the two groups in this univariate analysis was 585 days;

Adjusting the influence of all covariates, including those with significant imbalances at baseline: Patients who were cared for by spouses in the enhanced counseling and support group were placed at nursing homes at slightly less than 72% of the rate observed for those whose spouses were in the usual care group ((HR= 0.717, X2= 5.05, p= 0.025)

The difference in the model-predicted median time from baseline to nursing home placement for the two groups from this model was 557 days (usual care= 1,209 days, intervention= 1,766 days).

Improvements in caregivers’ satisfaction with social support, response to patient behavior problems, and symptoms of depression collectively accounted for 61.2% of the intervention’s beneficial impact on placement. |

Included in SR Pimouguet 2010 |

|

Mohide, 1990 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: home setting

Country: Canada

Funding and conflicts of interest: Supported by a grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health, Research and Planning Division, 1986- 1989. During this study, E. A. Mohide was a Career Scholar with the R. Samuel McLaughlin Centre for Gerontological Health Research, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario. At the time of funding, D. M. Pringle was Research Director for VON Canada

|

Inclusion criteria: Caregivers were eligible if they: - lived with the demented relative - providing day-to-day care to the relative - spoke English - scored 8 or more on mental-status - did not suffer from a life-threatening illness

Relatives were eligible if they: - had a medical diagnosis of primary degenerative, multi-infarct or mixed dementia - were assessed as moderately to severely impaired - did not suffer from a serious concomitant illness(es) - were not likely to be placed in a longterm care setting by their relatives during the course of the study.

Exclusion criteria: -

N total at baseline: Intervention: 30 Control: 30

Important prognostic factors2:

Age (SD): I: 66.10 (13.47) C: 69.40 (8.61)

Sex: I: 30% M C: 27% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

An experimental set of supportive interventions directed at helping the caregivers enhance caregiving competence and achieve a sense of control in their roles as caregivers.

The Caregiver Support NUrses were assigned to caregivers and made regularly scheduled home visits at a time that was convenient to the caregivers. Initially, these visits were weekly and were adjusted upward or downward depending on the needs of the caregiver. Health assessments of all caregivers were completed using forms designed to encourage the assessment of common caregiver problems. Caregivers were encouraged to seek medical attention for neglected health problems, such as hypertension. The CSNs consulted with the caregivers' family physicians on a regular basis whenever the caregivers' health was judged to be unstable. The caregivers received dementia and caregiving education using content and teaching methods tailored to the subjects' knowledge level, caregiving situation, and learning style |

Conventional community nursing care focused on care of the demented patient, rather than care of the family caregiver |

Length of follow-up: 6 months

Loss-to-follow-up: I: 8/30 C: 10/30

Reasons described: - Long-term placement of relative - Hospiralization >1 month of relative - Caregiver death - Relocation outside of study catchment

|

At baseline, caregivers in both groups were suffering from above average levels of depression (measured with CES-D) and anxiety (measured with STAI). After the six-month intervention period, we found neither experimental nor control group improved in these areas.

CES-D I: 15.40 (9.21) C: 21.55 (11.57)

At 6 months I: 18.20 (10.05) C:21.50 (12.98) STAI I: 50.41 (16.40) C: 46.25 (12.62)

At 6 months I: 49.64 (14.48) C: 48.50 (14.38)

The intervention group showed a clinically important improvement in quality of life:

Baseline: I: 0.55 (0.33) C: 0.56 (0.41)

At 6 monts: I: 0.64 (0.33) C: 0.53 (0.41)

Secondary outcomes: The intervention group experienced a slightly longer mean time to long-term institutionalization, found the caregiver role less problematic, and had greater satisfaction with nursing care than the control group. |

Included in SR Schoenmakers 2010, Pimouguet 2010, Tam-Tham 2013 |

|

Wright, 2001 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: home setting

Country:

Funding and conflicts of interest:

|

Inclusion criteria: Primary caregiver for afflicted elders, live within an 80 mile radius of the hospital, and live in the same household as the Alzheimer DIsease patient.

Exclusion criteria: -

N total at baseline: Intervention: 68 Control: 25

Important prognostic factors2:

Mean age (range): I: 59 (19–85) C: 59 (19–85)

Sex: I: 24% M C: 24% M

Groups comparable at baseline? No. The majority in the experimental group were spouses (50 versus 32% in the control group). The majority in the control group were daughters (44 versus 35% in experimental group) Ethic background was different: 26% minority caregivers were assigned to the experimental group and 46% to the control group. |

Baseline assessments (Time 0) were conducted while the elder was an inpatient. Postdischarge interventions and assessments were conducted at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 6 and 12 months (Times 1–5 respectively).

A gerontological or mental health clinical nurse specialist provided the interventions. First, caregivers were asked to identify the most trou- blesome behaviors in their afflicted family member (care recipient). Strategies for handling such behaviors as hiding and hoarding of objects, repetitive questions, or restlessness were discussed, and a plan for the caregiver to implement a new approach was developed. In addition, the care recipients’ medications were monitored. Second, the caregivers’ emotional and physical health was addressed with supportive counseling. Caregivers were encouraged to openly ex- press their anger, frustrations, and sadness. Strategies for getting help were discussed. If indicated, referrals to home health agencies, support groups, and intensive psychotherapy were made. |

Control group caregivers received phone calls on the same time schedule but for the purpose of data collection only. No education, counseling, or medication monitoring was offered. |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: 0 (NR?)

|

There were no significant treatment effects for care recipient agitation, caregiver stress, depression, and physical health, and no significant differences between groups in rates of institutionalization for afflicted elders. |

Included in SR Pimouguet 2010, Parker 2008, Tam-Tham 2013

AD afflicted elders’ disruptive behaviors were first stabilized in an inpatient setting, that is, a Behavioral Intensive Care Unit (BICU) specializing in geriatric care |

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures.

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors ((potential) confounders).

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls.

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Amjad 2018 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Callahan 2006 |

Included in Backhouse 2017 |

|

Chien 2008 |

Included in Backhouse 2017 |

|

Corvol 2017 |

Systematic review. Non-matching population. |

|

Eloniemi-Sulkava 2009 |

Wrong intervention |

|

van Hout 2014 |

Same as Vroomen 2012 |

|

Iliffe 2014 |

Wrong outcomes |

|

Jansen 2011 |

Included in Backhouse 2017 |

|

Jennings 2016 |

No comparison, wrong outcome |

|

Kenrik Duru 2009 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Khanassov 2014 |

Does not describe effects of case management |

|

Khanassov 2014 |

Systematic review. Wrong outcomes |

|

Khanassov 2016 |

Wrong outcomes |

|

Kwak 2011 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Lam 2010 |

Included in Backhouse 2017 |

|

Livingston 2017 |

No RCT or SR |

|

MacNeil Vroomen 2012 |

Study protocol |

|

MacNeil Vroomen 2015 |

No RCT |

|

Mavandadi 2017 |

Wrong intervention |

|

van Mierlo 2014 |

Does not describe effect of case management |

|

van Mierlo 2016 |

Same as Vroomen 2015 |

|

Morgan 2015 |

Wrong intervention, focus on costs |

|

Noel 2017 |

Focus on costs, no comparison |

|

Oyebode 2019 |

Does not describe effect of case management |

|

Parker 2008 |

Systematic review. Wrong intervention |

|

Peeters 2016 |

No RCT or SR |

|

Pimouguet 2010 |

Systematic review older than Backhouse 2017 |

|

Reilly 2015 |

Systematic review older than Backhouse 2017 |

|

Reisberg 2017 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Rosvik 2019 |

Scoping review, does not describe effect of case management |

|

Schoenmakers 2010 |

Systematic review. Wwrong intervention |

|

Somme 2012 |

Systematic review older than Backhouse 2017 |

|

Specht 2009 |

No RCT or SR |

|

Tam-Tham 2013 |

Systematic review older than Backhouse 2017 |

|

Tanner 2015 |

Non-matching population (MCI included) |

|

Teri 2018 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Vickrey 2006 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Vroomen 2016 |

No RCT |

|

Zabalegui 2014 |

Does not describe effects of case management |

|

Zwingman 2018 |

Secondary analysis of included study Thyrian |

|

|

|

|

From SRs |

|

|

Brodaty 1997 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Brodaty 2009 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Challis 2002 |

No RCT or SR |

|

Gaugler 2008 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Hinch liffe 1997 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Nobili 2004 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Teri 2003 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Vernooij-Dassen 1993 |

Not found |

|

Weinberger 1993 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Wray 2010 |

Wrong intervention |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 15-10-2024

Tijdens het opstellen van de richtlijn heeft de werkgroep per module een inschatting gemaakt over de maximale termijn waarop herbeoordeling moet plaatsvinden. In een aantal gevallen zijn er aandachtspunten geformuleerd die van belang zijn bij een toekomstige herziening. De geldigheid van de modules komt eerder te vervallen indien nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding zijn om een herziening te initiëren. Indien noodzakelijk wordt een nieuwe werkgroep geformeerd voor het herzien van de modules.

De Nederlandse Vereniging voor Klinische Geriatrie is regiehouder van de richtlijn Dementie en eerstverantwoordelijke voor het beoordelen van de actualiteit van de modules. De andere deelnemende wetenschappelijke verenigingen delen de verantwoordelijkheid en informeren de regiehouder over relevante ontwikkelingen binnen hun vakgebied.

|

Module |

Regiehouder(s) |

Jaar van autorisatie |

Eerstvolgende beoordeling actualiteit richtlijn |

Frequentie van beoordeling op actualiteit |

Wie houdt er toezicht op actualiteit |

Relevante factoren voor wijzigingen in aanbeveling |

|

Casemanagement |

NVKG |

2020 |

2025 |

5 jaar |

NVKG |

Nieuwe onderzoeksresultaten |

Algemene gegevens

De volgende partijen hebben goedkeuring verleend/aangegeven geen bezwaar te hebben:

- Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap

- Alzheimer Nederland

- Patientenfederatie Nederland

- Pharos

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Doel en doelgroep

Doel

Deze richtlijn vormt een handzame leidraad voor de dagelijkse praktijk van professionals in de dementiezorg (respectievelijk huisarts/specialist ouderengeneeskunde, geheugenpolikliniek ziekenhuis/GGZ en Alzheimer centra in academische ziekenhuizen en professionals zoals casemanager en praktijkverpleegkundige). De richtlijn vormt een aanvulling op de NHG-standaard dementie. Goede toepassing vraagt naast voldoende specifieke (na- en bij)scholing op dit gebied ook voldoende ervaring in diagnostiek, behandeling en begeleiding van patiënten met geheugenklachten en dementie van voldoende diverse etiologie. De richtlijn beoogt voor deze zorgverleners een kwaliteitsstandaard vast te stellen voor goede diagnostiek, begeleiding en behandeling en zo de variatie in de kwaliteit van zorg te verminderen. Die variatie zou ook minder moeten worden wat betreft de duur van het traject vanaf de vraag van de patiënt of diens naaste om duidelijkheid (“Wat is er aan de hand?), tot het moment waarop een diagnose gesteld wordt, omdat dit traject in een aanzienlijk aantal gevallen nog te veel vertraging kent.

Specifiek voor deze richtlijn is dat de doelgroep cognitieve beperkingen heeft en dat laaggeletterdheid en migratie-achtergrond vaak voorkomt omdat dit risicofactoren zijn voor het optreden van dementie. Daarom dient men specifiek bij deze populatie extra rekening te houden met laaggeletterdheid, migratie in het verleden en cognitieve stoornissen bij de uitvoering ervan.

Doelgroep

Deze richtlijn is geschreven voor alle leden van de medische beroepsgroepen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met dementie.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2018 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met dementie.

Werkgroep

- Prof. dr. M.G.M. Olde Rikkert, klinisch geriater, Radboud Alzheimer Centrum, Universitair Medisch Centrum St Radboud, Nijmegen, NVKG (voorzitter)

- Dr. B.N.M. van Berckel, nucleair geneeskundige, VUmc, Amsterdam, NVNG

- Prof. dr. J. Booij, nucleair geneeskundige, Academisch Medisch Centrum, Amsterdam, NVNG

- Dr. J.H.J.M. de Bresser, radioloog, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum, NVvR

- Dr. H.E.A. Dado-van Beek, klinisch geriater Vincent van Gogh voor Geestelijke Gezondheidszorg, Venray (AIOS tot januari 2020)

- Dr. A.J.M. Dieleman-Bij de Vaate, huisarts, NHG

- Dr. H.L. Koek, klinisch geriater, Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht, NVKG

- Drs. S.L.E. Lambooij, internist ouderengeneeskunde, Maxima Medisch Centrum, Veldhoven, NIV

- Dr. A.W. Lemstra, neuroloog, VUmc Alzheimercentrum, Amsterdam, NVN

- E. de Lijster, klinisch geriater Maasstad Ziekenhuis, Rotterdam (AIOS tot januari 2020), NVKG

- Prof. Dr. R.C. van der Mast, psychiater, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum, NVvP

- Dr. E.P. Moll van Charante, huisarts, Academisch Medisch Centrum, Amsterdam, NHG

- Dr. M. Perry, huisarts, Universitair Medisch Centrum St Radboud, Nijmegen, NHG

- Dr. E. Richard, neuroloog, Universitair Medisch Centrum St Radboud, Nijmegen, NVN

- Prof. dr. F.R.J. Verhey, psychiater, Alzheimer Centrum Limburg, Maastricht Universitair Medisch Centrum, NVvP

Klankbordgroep

- J. Lambregts-Rusche, namens Alzheimer Nederland

- G.B.J. (Gerben) Jansen BAC, Casemanager Dementie, namens Verpleegkundigen & Verzorgenden Nederland

- B. Ouwendijk, namens Verpleegkundigen & Verzorgenden Nederland

- Dr. J.R. van den Broeke, namens Pharos

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. M.A. Pols, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. J. Prins, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten (tot juli 2019)

- Dr. G. Peeters, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten (tot november 2019)

N.B. De werkgroep heeft zich gericht op de daadwerkelijke ontwikkeling van de modules en was verantwoordelijk voor het schrijven van de teksten. De klankbordgroep heeft commentaar op de conceptmodules gegeven.

Belangenverklaringen

De KNMG-code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement, kennisvalorisatie) hebben gehad. Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Olde Rikkert |

|

|

Memorabel project richting Dashboard voor Dementiezorg, waarbij Medwork BV partner is.

|

Geen |

|

Booij |

|

|

|

Geen |

|

De Bresser |

|

Geen |

|

Geen |

|

Dado-van Beek |

|

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Koek |

|

|

|

Geen |

|

Richard |

|

|

|

Geen |

|

Lemstra |

|

Geen |

onderzoek wordt gesponsord door respectievelijk -ZonMW -Alzheimer Nederland -Stichting Dioraphte Deze financiers hebben geen belang bij bepaalde uitkomsten van de richtlijn |

Geen |

|

Lambooij |

|

|

Geen |

Geen |

|

De Lijster |

|

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Van Berckel |

|

|

Geen |

Geen |

|

Dieleman-Bij de Vaate |

|

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Verhey |

|

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Van der Mast |

|

|

Geen |

Geen |

|

Perry |

|

|

|

Geen |

|

Moll van Charante |

|

|

Geen |

Geen |

|

Klankbordgroep lid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Jansen |

|

|

|

Geen |

|

Ouwendijk |

|

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Van den Broeke |

|

|

|

Geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door participatie van Alzheimer Nederland en Pharos aan de invitational conference en in de klankbordgroep. Voorafgaand aan de commentaarronde zijn de conceptmodules aan deze partijen voorgelegd.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met dementie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door Alzheimer Nederland, Verpleegkundigen & Verzorgenden Nederland, Nederlands Instituut van Psychologen, Zorginstituut Nederland, Integraal Kankercentrum Nederland en Inspectie Gezondheidszorg en Jeugd via een Invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen in de bijlagen.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep, voor zover mogelijk, tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden. Waar mogelijk gezien de verschillende timing van zorgstandaard en richtlijn-update is met de zorgstandaard rekening gehouden. Beide hebben evenwel een eigenstandige methodologie, waarbij deze richtlijn de werkwijze van evidence based richtlijnontwikkeling volgt.

Strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.