Anti-emetica bij braken

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de waarde van anti-emetica bij braken, bij kinderen met dehydratie in de tweede lijn?

Clinical question

What is the value of antiemetics for vomiting, in children with dehydration?

Aanbeveling

Geef éénmalig ondansetron oraal bij kinderen die zich op de eerste hulp presenteren met (dreigende) dehydratie op basis van braken op basis van een acute gastro-enteritis.

Geef géén ondansetron aan kinderen met een aangeboren lang QT-syndroom.

Overweeg bij kinderen met een risico op een verlengde QTc-tijd, zoals bij hartfalen, bradycardie of gebruik van andere QT-verlengende medicatie, een ecg te maken en dien ondansetron alleen toe bij normale QTc tijd.

Overwegingen

Er is literatuuronderzoek uitgevoerd naar de effectiviteit van ondansetron bij de behandeling van kinderen met gastro-enteritis die braken. De conclusies berusten uiteindelijk op een recente systematische review van RCT’s (Fugetto, 2020), waarbij een enkele gift ondansetron in de SEH setting werd vergeleken met een placebo bij patiënten in de leeftijd tussen 3 maanden en 18 jaar die niet of matig gedehydreerd waren.

Op basis van de conclusies uit de literatuursamenvatting kan het volgende worden gezegd; met betrekking tot de cruciale uitkomstmaten kans van slagen van orale rehydratie, noodzaak tot intraveneuze rehydratie en noodzaak tot ziekenhuisopname resulteert een éénmalige gift ondansetron hoogstwaarschijnlijk in een toegenomen kans van slagen van orale rehydratie, in een afname van de noodzaak tot intraveneuze rehydratie en in een afname van de noodzaak tot ziekenhuisopname. De bewijskracht hiervoor is redelijk.

Met betrekking tot de cruciale uitkomstmaten tijd tot rehydratie, rehydratie per sonde en duur van ziekenhuisopname kan op basis van de conclusies uit de literatuursamenvatting geen conclusie worden getrokken. Met betrekking tot de belangrijke uitkomstmaat braken leidt behandeling met ondansetron hoogstwaarschijnlijk tot een lichte afname van braken ten opzichte van behandeling met placebo. Voor de andere belangrijke uitkomstmaten, zoals terugkerend bezoek aan de spoedeisende hulp en adverse events lijkt ondansetron in betere uitkomsten te resulteren in vergelijking met behandeling met placebo al is de bewijskracht hiervoor laag.

Over het optreden van bijwerkingen van éénmalige toediening van ondansetron kan op basis van de voorliggende systematische review worden gezegd dat de incidentie van bijwerkingen erg laag lijkt te zijn, maar de bewijskracht daarvoor is laag.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voor de overgrote meerderheid van patiënten (en hun ouders) die met gastro-enteritis en braken presenteren op de spoedeisende hulp is het innemen/toegediend krijgen van ondansetron een weinig belastende en veilige behandeling. Toedienen van ondansetron kan andere interventies (plaatsen van een infuus, opname) voorkomen en leidt waarschijnlijk tot afname van braken. Dit zijn duidelijke voordelen voor patiënt en ouder(s). Mogelijk is er na toediening van ondansetron ook minder noodzaak tot het plaatsen van een maagsonde bij genoemde groep van patienten, maar in de genoemde studies is dat niet onderzocht.

Mogelijk zijn er subgroepen van patiënten, waarbij toedienen van ondansetron nadere afweging behoeft. Het geneesmiddelenbulletin beschrijft bij ondansetron een (zeldzaam) verhoogd risico op hartritmestoornissen met verlenging van de QT-tijd op het ECG. Deze bijwerking is in potentie fataal, omdat het een verhoogd risico geeft op het ontwikkelen van ’torsade de pointes’ (ventrikeltachycardie). Het optreden van deze bijwerking is beperkt tot kinderen met een verhoogd risico en is dosisafhankelijk. Een verhoogd risico bestaat bij hartfalen, bradycardie, aangeboren lang-QT-intervalsyndroom of gebruik van andere QT-verlengende medicatie. In geen van de studies die bijwerkingen beschreef werden hartritmesoornissen beschreven, maar in geen van de studies zijn ECG’s gemaakt. NB het gebruik van ondansetron is goed onderzocht bij kinderen, maar is formeel voor de bestudeerde indicatie (braken bij gastro-enteritis) off label.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

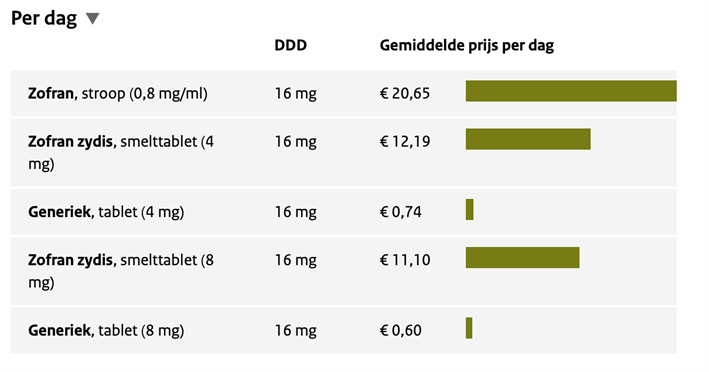

De kosten van ondansetron zijn laag. Bij kleine kinderen moet soms worden gekozen voor zuigtabletten of drank, die duidelijk duurder zijn dan de gewone tabletten (tabel 1). Zonder uitgebreide berekening over kosteneffectiviteit is duidelijk dat deze kosten in het niet vallen bij de kosten van het SEH-bezoek en bij de interventies (sonde en/of infuus, opname) die met toediening van ondansetron kan worden voorkomen.

Tabel 1. Kosten ondansetron (Bron: Farmacotherapeutisch contact, september 2021)

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Ondansetron wordt in de meeste ziekenhuizen in Nederland op alle klinische en spoedeisensde hulp afdelingen gebruikt voor volwassenen en kinderen met klachten van misselijkheid of braken. Beschikbaarheid van verschillende orale doseringen en toedieningsvormen (tablet, drank, smelttablet) is haalbaar en strekt tot de aanbeveling. Voor kinderen met een lang QT-syndroom bestaat een contra-indicatie voor het gebruik van ondansetron. Voor kinderen met een verhoogd risico op het hebben van een verlengd QT-syndroom (op basis van familie-anamnese of gebruik van andere QTc-verlengende medicatie) is het waarschijnlijk verstandig een ECG te maken voor het bepalen van de QTc tijd voor het besluit tot toediening van ondansetron. Het maken en beoordelen van het ECG is belastend voor patiënt, personeel en middelen. Er is behoefte aan een preciezer advies voor deze situatie.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Ondansetron wordt in Nederland en elders op de wereld veel gebruikt bij kinderen die op de spoedeisende hulp worden gezien met (dreigende) dehydratie door braken ten gevolge van een gastro-enteritis. Uit de gevonden literatuur blijkt dat het gebruik van ondansetron in deze situatie hoogstwaarschijnlijk resulteert in minder interventies (plaatsen van infuus) en in minder opnames voor rehydratie. Ook blijkt dat patiënten na gebruik van ondansetron waarschijnlijk minder braken.

De behandeling met ondansetron heeft dus duidelijke voordelen voor patiënt en ouders en is redelijk eenvoudig uit te voeren. Het geneesmiddel is beschikbaar als tablet, zuigtablet en drank en relatief goedkoop.

Aanbeveling-subgroep kinderen met een lang QT-syndroom of met een risico daarop

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van de argumenten voor en tegen de interventie

Voor kinderen met een lang QTc syndroom bestaat een contra-indicatie voor het toedienen van ondansetron, omdat het middel de QTc tijd kan verlengen, hetgeen het risico op het optreden van hartritmestoornissen kan verhogen. Het optreden van deze bijwerking is beperkt tot kinderen met een verhoogd risico en is dosisafhankelijk. Een verhoogd risico bestaat bij hartfalen, bradycardie, aangeboren lang-QT-intervalsyndroom of gebruik van andere QT-verlengende medicatie.

Voor kinderen met een verhoogd risico op het hebben van een verlengd QT-syndroom is het advies een ECG te maken, voor het bepalen van de QTc tijd, alvorens te besluiten tot toediening van ondansetron.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Kinderen met gastro-enteritis kunnen veel braken, hetgeen bijdraagt aan de ernst van de dehydratie. Ook kan braken een oorzaak zijn van het falen van orale rehydratie met of zonder sonde. Er is literatuur die het positieve effect van anti-emetica in deze situatie onderschrijft. Minder (of minder frequent) braken kan leiden tot snellere rehydratie en herstel.

In de Nederlandse situatie worden de meeste kinderen oraal of met een sonde gerehydreerd. Dat kan tijdens een klinische opname zijn, maar ook in een SEH-setting, waar in korte tijd veel ORS via de sonde wordt toegediend. Anti-emetica kunnen daarbij mogelijk een positieve rol spelen. Anti-emetica kunnen bijwerkingen hebben (de meest genoemden: QTc verlenging, extrapiramidale verschijnselen, toename diarree); er zijn verschillende soorten anti-emetica, maar in de regel wordt op basis van effectiviteit en het bijwerkingenprofiel overwegend alleen nog ondansetron oraal (of iv) gebruikt.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

High GRADE |

Treatment with a single dose ondansetron reduces failure of oral rehydration therapy when compared with placebo treatment in children with gastro-enteritis who vomit.

Sources: Fugetto, 2020 (Cubeddu, 1997; Danewa, 2016; Freedman, 2006; Golshekan, 2013; Yilmaz, 2010). |

|

No GRADE |

Because none of the studies reported the outcome measure time to rehydration related to the comparison of ondansetron treatment with placebo treatment, it was not possible to draw any conclusions regarding this outcome measure.

Sources: - |

|

No GRADE |

Because none of the studies reported the outcome measure need for nasogastric tube rehydration related to the comparison of ondansetron treatment with placebo treatment, it was not possible to draw any conclusions regarding this outcome measure.

Sources: - |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Treatment with a single dose ondansetron reduces need for hospitalization when compared with placebo treatment in children with gastro-enteritis who vomit.

Sources: Fugetto, 2020 (Freedman, 2006; Golshekan, 2013; Marchetti, 2016; Roslund, 2008; Stork, 2006). |

|

No GRADE |

Because none of the studies reported the outcome measure length of hospital stay related to the comparison of ondansetron treatment with placebo treatment, it was not possible to draw any conclusions regarding this outcome measure.

Sources: - |

|

High GRADE |

Treatment with a single dose ondansetron reduces the need for intravenous rehydration when compared with placebo treatment in children with gastro-enteritis who vomit.

Sources: Fugetto, 2020 (Danewa, 2016; Freedman, 2006; Freedman, 2018; Marchetti, 2016; Ramsook, 2002; Rang, 2019). |

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with a single dose ondansetron may result in little to no difference in return visits to the emergency department when compared with placebo treatment in children with gastro-enteritis who vomit. The reported incidence of return visits was around 10%

Sources: Fugetto, 2020 (Freedman, 2006; Freedman, 2018; Marchetti, 2016; Ransmook, 2002; Roslund, 2008). |

|

No GRADE |

Because none of the studies reported the outcome measure weight loss related to the comparison of ondansetron treatment with placebo treatment, it was not possible to draw any conclusions regarding this outcome measure.

Sources: - |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Treatment with a single dose ondansetron reduces vomiting slightly when compared with placebo treatment in children with gastro-enteritis who vomit.

Sources: Fugetto, 2020 (Cubeddu, 1997; Freedman, 2006; Freedman, 2018; Golshekan, 2013; Marchetti, 2016; Ramsook, 2002; Rang, 2019; Rerksuppaphol, 2010; Roslund, 2008; Yilmaz, 2010). |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with ondansetron on diarrhea when compared with placebo treatment in children with gastro-enteritis who vomit.

Sources: Fugetto, 2020 (Hagbom, 2016; Rang, 2019). |

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with a single dose ondansetron may result in little to no difference in complications when compared with placebo treatment in children with gastro-enteritis who vomit.

Sources: Fugetto, 2020 (Cubeddu, 1997; Ramsook, 2002; Yilmaz, 2010; Danewa, 2016). |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Fugetto (2020) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of a single dose of ondansetron versus placebo prescribed for vomiting due to acute gastroenteritis in children and adolescents. The electronic databases Medline (Pubmed), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Scopus (Elsevier) were searched to identify relevant studies up to November 2019. Reference lists of selected reviews, original articles, textbooks, organizations’ websites, and guideline clearinghouses were scanned in order to find additional articles. Investigators and corresponding authors were contacted to seek information about unpublished/incomplete studies. A snowball technique was applied to the search strategy. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared ondansetron administered orally or intravenous at any dosage with placebo, prescribed to terminate or reduce vomiting in children and adolescents under the age of eighteen with clinically suspected acute gastroenteritis, were included. Studies that evaluated the following outcomes were included in the systematic review: cessation of vomiting (i.e., 0 vomiting episodes during the observation period) within eight and 24 hours after the administration of the treatment; failure of oral rehydration therapy (i.e., inability to tolerate a maximum of two trials of ORT, separated by > 30 min) need for IV rehydration during the ED stay, hospitalization (i.e., admission at pediatric ward) within 8 and at 48 h of follow-up, return to the ED after discharge (i.e., number of participants that revisited the ED up to 72 h after discharge), number of diarrhea episodes at 24 h after the administration of the treatment, and any clinically documented or patient-reported adverse events (AE) (secondary outcomes). A total of thirteen RCTs among 2146 pediatric patients were included. Two RCTs included hospitalized patients (Rang, 2019; Rerksuppaphol, 2010), while the remaining studies were carried out in emergency departments (Cubeddu, 1997; Danewa, 2016; Freedman, 2006; Freedman, 2018; Golshekan, 2013; Hagbom, 2017; Marchetti, 2016; Ramsook, 2002; Roslund, 2008; Stork, 2006; Yilmaz, 2010). The inclusion criteria for enrolment were similar for all studies, and the age of participants ranged from three months to sixteen years. All studies included subjects with none to moderate dehydration, except four studies in which hydration status was not specified (Golshekan, 2013; Hagbom, 2017; Rerksuppaphol, 2010; Yilmaz, 2010). The reported outcome measures in the study were cessation of vomiting, failure of oral rehydration therapy, intravenous rehydration rates, hospitalization rates, return visits to the emergency department, number of diarrhea episodes, and adverse events.

Results

1. Success/failure of oral rehydration (critical)

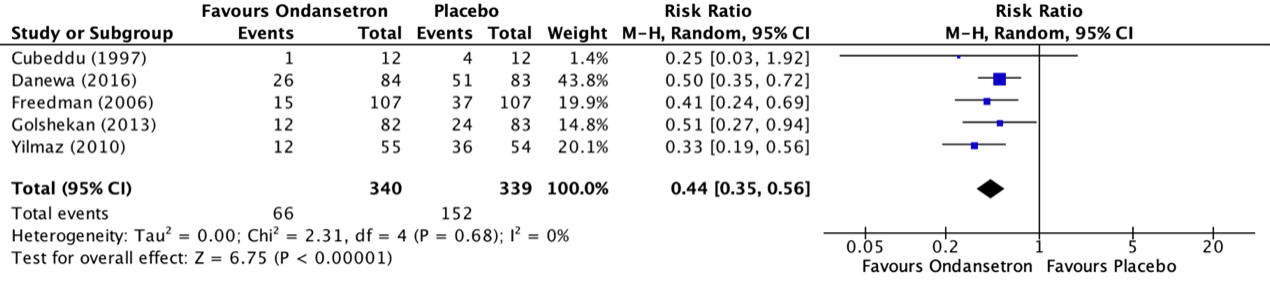

The outcome measure success/failure of oral rehydration was reported in five RCTs (Cubeddu, 1997; Danewa, 2016; Freedman, 2006; Golshekan, 2013; Yilmaz, 2010) included in the systematic review of Fugetto (2020). The outcome was described as the incidence of failure of oral rehydration therapy during the emergency department stay. The results of the individual studies were retrieved and pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled incidence of failure of oral rehydration therapy during the emergency department stay in the ondansetron treatment group was 66/340 (19.4%), compared to 152/339 (44.8%) in the placebo treatment group. This resulted in a pooled risk ratio (RR) of 0.44 (95% CI 0.35 to 0.56) in favor of the ondansetron treatment group (figure 1). This means that treatment with ondansetron reduces failure of oral rehydration therapy during the emergency department stay with 56%. This is considered as a clinically relevant difference. The number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent 1 failure of oral rehydration was calculated as 4.

Figure 1. Outcome failure of oral rehydration therapy during the ED stay comparison ondansetron versus placebo

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

2. Time to rehydration (critical)

The time to rehydration was not reported in the systematic review of Fugetto (2020).

3. Need for nasogastric tube/rehydration (critical)

The need for nasogastric tube/rehydration was not reported in the systematic review of Fugetto (2020).

4. Need for hospitalization (critical)

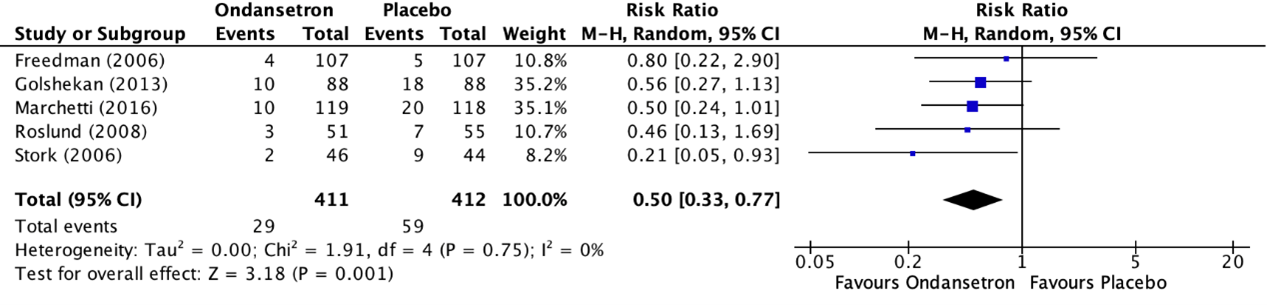

Fugetto (2020) reported the outcome measure need for hospitalization in five RCTs (Freedman, 2006; Golshekan, 2013; Marchetti, 2016; Roslund, 2008; Stork, 2006). The outcome measure need for hospitalization was described as the incidence of hospitalization within eight hours after the administration of the treatment. The results of the individual studies were retrieved and pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled incidence of hospitalization within eight hours after the administration of the treatment in the ondansetron treatment group was 29/411 (7.1%), compared to 59/412 (14.3%) in the placebo treatment group. This resulted in a pooled risk ratio (RR) of 0.50 (95% CI 0.33 to 0.77) in favor of the ondansetron treatment group (figure 2). This means that treatment with ondansetron reduces the chance on hospitalization within eight hours after the administration of the treatment with 50%. This is considered as a clinically relevant difference. The number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent 1 hospitalization was calculated as 14.

Additionally, the study of Golshekan (2013) reported the incidence of hospitalization 48 hours after administration of the treatment and reported an incidence in the group of treatment with ondansetron of 2/72 (2.8%), compared to 2/65 (3.1%) in the placebo treatment group. This resulted in a risk ratio (RR) of 0.90 (95% CI 0.13 to 6.23) in favor of the ondansetron treatment group. This is not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 2. Outcome Need for hospitalization comparison ondansetron versus placebo

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

5. Length of hospital stay (critical)

The length of hospital stay was not reported in the systematic review of Fugetto (2020).

6. Need for intravenous rehydration (critical)

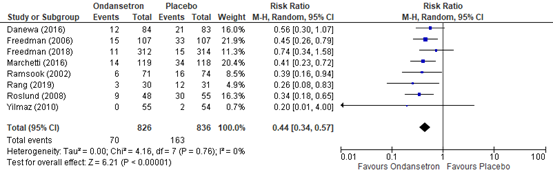

The outcome measure need for intravenous rehydration during the emergency department stay was reported in eight RCTs (Danewa, 2016; Freedman, 2006; Freedman, 2018; Marchetti, 2016; Ramsook, 2002; Rang, 2019; Roslund, 2008; Yilmaz, 2010) included in the systematic review of Fugetto (2020). Need for intravenous rehydration was described as the incidence of intravenous rehydration during the emergency department stay. The results of the individual studies were retrieved and pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled incidence of intravenous rehydration during the emergency department stay in the ondansetron treatment group was 70/826 (8.5%), compared to 163/836 (19.4%) in the placebo treatment group. This resulted in a pooled risk ratio (RR) of 0.44 (95% CI 0.34 to 0.57) in favor of the ondansetron treatment group (figure 3). This means that treatment with ondansetron reduces the chance on intravenous rehydration during the emergency department stay with 56%. This is considered as a clinically relevant difference. The number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent 1 instance of intravenous rehydration was calculated as 10.

Figure 3. Outcome need for intravenous rehydration comparison ondansetron versus placebo

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

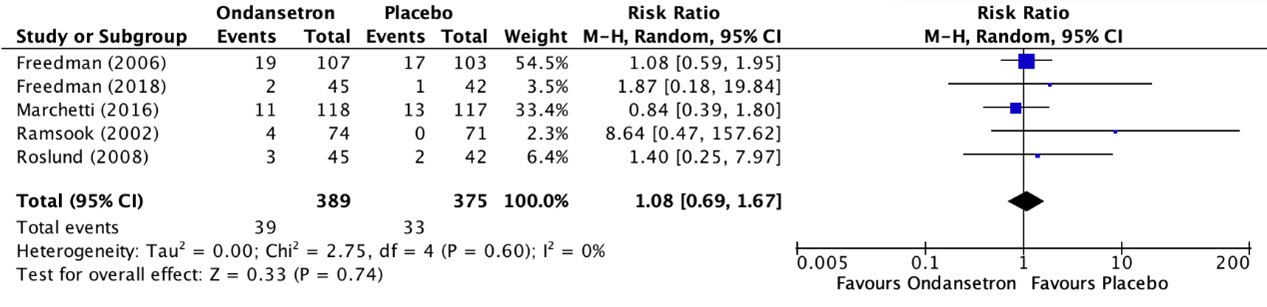

7. Return visits to the emergency department

The outcome measure return visits to the emergency department was reported in five RCTs included in the systematic review of Fugetto (2020) (Freedman, 2006; Freedman, 2016; Marchetti, 2016; Ramsook, 2002; Roslund, 2008). The results of the individual studies were retrieved and pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled incidence of return visits to the emergency department in the ondansetron treatment group was 39/389 (10.0%), compared to 33/375 (8.8%) in the placebo treatment group. This resulted in a pooled risk ratio (RR) of 1.08 (95% CI 0.69 to 1.67) in favor of the placebo treatment group (figure 4). This is not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 4. Outcome return visits to the emergency department comparison ondansetron versus placebo

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

8. Weight loss

Weight loss was not reported in the systematic review of Fugetto (2020).

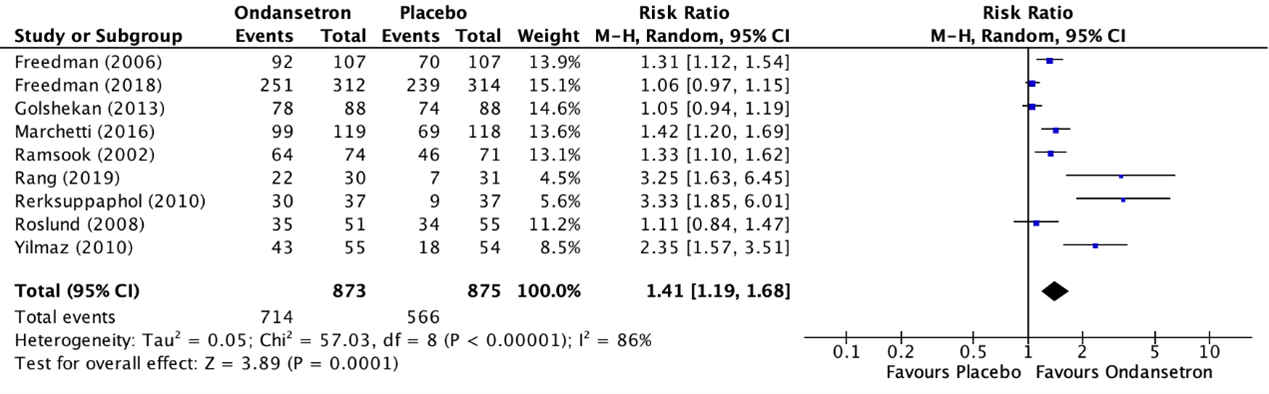

9. Vomiting (important)

The outcome measure vomiting was reported in ten RCTs included in the systematic review of Fugetto (2020) (Cubeddu, 1997; Freedman, 2006; Freedman, 2018; Golshekan, 2013; Marchetti, 2016; Ramsook, 2002; Rang, 2019; Rerksuppaphol, 2010; Roslund, 2008; Yilmaz, 2010). Vomiting was described as the incidence of cessation of vomiting within eight hours after the administration of the treatment. The study of Cubeddu (1997) reported cessation of vomiting 24 hours after the administration of the treatment. The results of the individual studies were retrieved and pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled incidence of cessation of vomiting withing eight hours after the administration of the treatment in the ondansetron treatment group was 714/873 (81.8%), compared to 566/875 (64.7%) in the placebo treatment group. This resulted in a pooled risk ratio (RR) of 1.41 (95% CI 1.19 to 1.68) in favor of the ondansetron treatment group (figure 5). This means that treatment with ondansetron increases the chance on cessation of vomiting within eight hours after the administration of the treatment with 41%. This is considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Additionally, the study of Cubeddu (1997) reported the incidence of cessation of vomiting 48 hours after administration of the treatment and reported an incidence in the group of treatment with ondansetron of 7/12 (58.3%), compared to 2/12 (16.7%) in the placebo treatment group. This resulted in a risk ratio (RR) of 3.50 (95% CI 0.91 to 13.53) in favor of the ondansetron treatment group. This is considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 5. Outcome vomiting comparison ondansetron versus placebo

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

10. Diarrhea (important)

The outcome measure diarrhea was reported in four included RCTs in the systematic review of Fugetto (2020). Diarrhea was described as the number of diarrhea episodes 24 hours after the administration of the treatment. The RCT of Rang (2019) reported a median (range) number of diarrhea episodes 24 hours after administration of the treatment in the group of treatment with ondansetron of 5 (2 to 18), compared to 6 (1 to 18) in the placebo treatment group. This is not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

The RCT of Ramsook (2002) reported the number of diarrhea episodes in the first 24 hours and the second 24 hours after administration of the treatment. Patients in the ondansetron group had a mean of 4.70 episodes of diarrhea in the first 24 hours and 2.98 in the second 24 hours after treatment, while the control group had 1.37 and 0.96 episodes in the first and second 24 hours. No standard deviations or effect measures were reported.

Marchetti (2016) reported the number of patients who experienced an episode of diarrhea in the first 48 hours after initiation of treatment. In the ondansetron group, 49 patients (41.5%) experienced episodes of diarrhea, while in the control group, 44 patients (37.6%) had one or more episodes of diarrhea. Marchetti (2016) only reported a p-value and no mean difference.

The RCT of Hagbom (2017) reported a median number of diarrhea episodes 24 hours after administration of the treatment. but did not report an interquartile range. The median number of diarrhea episodes 24 hours after administration of the treatment in the group of treatment with ondansetron of 1.00 compared to 3.5 in the placebo treatment group.

Due to the incomparability of the reported units of the outcome measures, the results could not be pooled.

11. Complications and side effects (important)

The outcome measure complications and side effects was reported as adverse events in four RCTs included in the systematic review of Fugetto (2020) (Cubeddu, 1997; Ramsook, 2002; Yilmaz, 2010; Danewa, 2016). The results of the individual studies could not be pooled in a meta-analysis, because the outcome measures were reported in different units and often without standard deviations. Cubeddu (1997) reported the incidence of coughing in the group of treatment with ondansetron and the placebo treatment group. The incidence of coughing in the group of treatment with ondansetron was 3/12 (25.0%), compared to 0/12 (0%) in the placebo treatment group. A risk ratio could not be calculated as the number of events in one of the groups was zero.

Ramsook (2002) reported the incidence of macular rash in the group of treatment with ondansetron and the placebo treatment group. The incidence of macular rash in the group of treatment with ondansetron was 1/74 (1.4%), compared to 0/71 (0%) in the placebo treatment group. A risk ratio could not be calculated as the number of events in one of the groups was zero.

Yilmaz (2010) reported the incidence of abdominal distension in the group of treatment with ondansetron and the placebo treatment group. The incidence of abdominal distension in the group of treatment with ondansetron was 1/55 (1.8%), compared to 0/54 (0%) in the placebo treatment group. A risk ratio could not be calculated as the number of events in one of the groups was zero.

Danewa (2016) reported that they did not observe any adverse event (which they defined as headache, rash or any other reported event).

The other studies reported that they did not observe adverse effects in the intervention and control arms.

In none of the 13 studies ECG’s were performed after the administration of ondansetron.

Level of evidence of the literature

1. Success/failure of oral rehydration (critical)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure success/failure of oral rehydration was not downgraded. The level of evidence is high.

2. Time to rehydration

The level of evidence could not be graded for the outcome measure time to rehydration, as this was not reported in the included studies.

3. Need for nasogastric tube/rehydration (critical)

The level of evidence could not be graded for the outcome measure need for nasogastric tube/rehydration, as this was not reported in the included studies.

4. Need for hospitalization (critical)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure need for hospitalization was downgraded by one level because the confidence interval crossing the boundaries of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is moderate.

5. Length of hospital stay (critical)

The level of evidence could not be graded for the outcome measure length of hospital stay, as this was not reported in the included studies.

6. Need for intravenous rehydration (critical)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure need for intravenous rehydration was not downgraded. The level of evidence is high.

7. Return visits to the emergency department (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure return visits to the emergency department was downgraded by two levels because of conflicting results (inconsistency -1) and the confidence interval crossing the boundaries of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

8. Weight loss

The level of evidence could not be graded for the outcome measure weight loss, as this was not reported in the included studies.

9. Vomiting (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure vomiting was downgraded by one level because the confidence interval crosses the boundaries of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is moderate.

10. Diarrhea (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure diarrhea was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (reporting bias, -1), the small number of included patients and the small number of events (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence is very low.

11. Complications (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure complications was downgraded by two levels because of the small number of included patients and small number of events (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence is low.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

P: Children (0-12 years) with gastro-enteritis who vomit.

I: Antiemetics

C: Placebo

O: Success/failure of oral rehydration, time to rehydration, need for nasogastric tube/rehydration, need for hospitalization, length of hospital stay, need for intravenous rehydration, length of stay emergency department, weight loss, vomiting, diarrhea, complications/side effects (QTc extension, ECG abnormalities).

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered success/failure of oral rehydration, time to rehydration, need for nasogastric tube rehydration, need for hospitalization, length of hospital stay, need for intravenous rehydration as critical outcome measures for decision making; and length of stay emergency department, weight loss, vomiting, diarrhea, complications/side effects as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

For all outcome measures, the working group used the default thresholds proposed by the international GRADE working group to define minimally clinically (patient) important differences: a 25% difference in risk ratio (RR) for dichotomous outcomes, and 0.5 standard deviations (SD) for continuous outcomes.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 31 March 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 558 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, and observational studies on the value of antiemetics for vomiting in children with dehydration. Seven studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, six studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and one study was included.

Results

One study was included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Cubeddu LX, Trujillo LM, Talmaciu I, Gonzalez V, Guariguata J, Seijas J, Miller IA, Paska W. Antiemetic activity of ondansetron in acute gastroenteritis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997 Feb;11(1):185-91. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.97269000.x. PMID: 9042992.

- Danewa AS, Shah D, Batra P, Bhattacharya SK, Gupta P. Oral Ondansetron in Management of Dehydrating Diarrhea with Vomiting in Children Aged 3 Months to 5 Years: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Pediatr. 2016 Feb;169:105-9.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.10.006. Epub 2015 Dec 1. PMID: 26654135.

- Freedman SB, Soofi SB, Willan AR, Williamson-Urquhart S, Ali N, Xie J, Dawoud F, Bhutta ZA. Oral Ondansetron Administration to Nondehydrated Children With Diarrhea and Associated Vomiting in Emergency Departments in Pakistan: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2019 Mar;73(3):255-265. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.09.011. Epub 2018 Nov 2. PMID: 30392735; PMCID: PMC6390170.

- Freedman SB, Adler M, Seshadri R, Powell EC. Oral ondansetron for gastroenteritis in a pediatric emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006 Apr 20;354(16):1698-705. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055119. PMID: 16625009.

- Fugetto F, Filice E, Biagi C, Pierantoni L, Gori D, Lanari M. Single-dose of ondansetron for vomiting in children and adolescents with acute gastroenteritis-an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Pediatr. 2020 Jul;179(7):1007-1016. doi: 10.1007/s00431-020-03653-0. Epub 2020 May 7. PMID: 32382791.

- Golshekan K, Badeli H, Rezaieian S, Mohammadpour H, Hassanzadehrad A. Effect of oral ondansetron on decreasing the vomiting associated with acute gastroenteritis in Iranian children. Iran J Pediatr. 2013 Oct;23(5):557-63. PMID: 24800017; PMCID: PMC4006506.

- Hagbom M, Novak D, Ekström M, Khalid Y, Andersson M, Lindh M, Nordgren J, Svensson L. Ondansetron treatment reduces rotavirus symptoms-A randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled trial. PLoS One. 2017 Oct 27;12(10):e0186824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186824. PMID: 29077725; PMCID: PMC5659648.

- Marchetti F, Bonati M, Maestro A, Zanon D, Rovere F, Arrighini A, Barbi E, Bertolani P, Biban P, Da Dalt L, Guala A, Mazzoni E, Pazzaglia A, Perri PF, Reale A, Renna S, Urbino AF, Valletta E, Vitale A, Zangardi T, Clavenna A, Ronfani L; SONDO (Study ONdansetron vs DOmperidone) Investigators. Oral Ondansetron versus Domperidone for Acute Gastroenteritis in Pediatric Emergency Departments: Multicenter Double Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS One. 2016 Nov 23;11(11):e0165441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165441. PMID: 27880811; PMCID: PMC5120790.

- Ramsook C, Sahagun-Carreon I, Kozinetz CA, Moro-Sutherland D. A randomized clinical trial comparing oral ondansetron with placebo in children with vomiting from acute gastroenteritis. Ann Emerg Med. 2002 Apr;39(4):397-403. doi: 10.1067/mem.2002.122706. PMID: 11919526.

- Rang NN, Chanh TQ, My PT, Tien TTM. Single-dose Intravenous Ondansetron in Children with Gastroenteritis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Indian Pediatr. 2019 Jun 15;56(6):468-471. PMID: 31278225.

- Rerksuppaphol S, Rerksuppaphol L. Efficacy of intravenous ondansetron to prevent vomiting episodes in acute gastroenteritis: a randomized, double blind, and controlled trial. Pediatr Rep. 2010 Sep 6;2(2):e17. doi: 10.4081/pr.2010.e17. PMID: 21589830; PMCID: PMC3093998.

- Roslund G, Hepps TS, McQuillen KK. The role of oral ondansetron in children with vomiting as a result of acute gastritis/gastroenteritis who have failed oral rehydration therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2008 Jul;52(1):22-29.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.09.010. Epub 2007 Nov 19. Erratum in: Ann Emerg Med. 2008 Oct;52(4):406. PMID: 18006189.

- Stork CM, Brown KM, Reilly TH, Secreti L, Brown LH. Emergency department treatment of viral gastritis using intravenous ondansetron or dexamethasone in children. Acad Emerg Med. 2006 Oct;13(10):1027-33. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.05.018. Epub 2006 Aug 10. PMID: 16902049.

- Verhoog A, de Vries TW. Ondansetron bij kinderen met gastro-enteritis. Geneesmiddelenbulletin. 2022 Feb 3;56:13-15. doi: 10.35351

- Yilmaz HL, Yildizdas RD, Sertdemir Y. Clinical trial: oral ondansetron for reducing vomiting secondary to acute gastroenteritis in children--a double-blind randomized study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010 Jan;31(1):82-91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04145.x. PMID: 19758398.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence tables

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Fugetto, 2020

|

SR and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

Literature search up to November 2019.

Study design: RCTs evaluating ondansetron administered orally or IV at any dosage versus placebo, prescribed to terminate or reduce vomiting in children and adolescents under the age of 18 with clinically suspected acute gastroenteritis.

Setting and Country: Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences (DIMEC), Pediatric Emergency Unit, St. Orsola Hospital, University of Bologna, via Massarenti 9, 40138 Bologna, Italy.

Source of funding There is no funding source.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

Seven studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N

mean age

Sex, n/N M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Route: IV Dose: 0.3 mg/kg single dose

Route: oral (syrup) Dose: 0.2 mg/kg single dose

Route: oral (ODT) Dose: 8-15 kg: 2 mg; 15-30 kg: 4 mg; > 30 kg: 8 mg (all single dose).

Route: oral (ODT) Dose: 8-15 kg: 2 mg; 15-30 kg: 4 mg (single dose)

Route: oral (tablet) Dose: < 15 kg: 2 mg; 15-30 kg: 4 mg; >30 kg: 6 mg (single dose)

Route: oral (syrup) Dose: 0.15 mg/kg (single dose)

Route: Oral (syrup) Dose: 1.6 mg every 8 h for patients aged 6 months to 1 year, 3.2 mg every 8 h for patients aged 1 to 3 years, and 4 mg every 8h for patients aged 4 to 12 years (six doses in total)

Route: Oral (syrup) Dose: 0.15 mg/kg (single dose).

Route: IV Dose: IV ondansetron at a dose of 0.2 mg/Kg up to maximal dose of 8 mg (single dose)

Route: IV Dose: 0.15 mg/kg up to maximal dose of 8 mg (single dose)

Route: oral (ODT) Dose: < 15 kg: 2 mg; 15-30 kg: 4 mg; >30 kg: 6 mg (single dose).

Route: IV Dose: 0.15 mg/kg (single dose).

Route: Oral (ODT) Dose: 0.2 mg/kg at 8h intervals (three doses in total).

|

All studies compared the intervention to placebo. |

End-point of follow-up:

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported.

|

1. Success/failure of treatment (Failure of oral rehydration therapy during the emergency department stay) Effect measure: RR (95% CI: A: 0.25 (0.03 to 1.92) B: 0.50 (0.35 to 0.72 C: 0.41 (0.24 to 0.69) E: 0.51 (0.27 to 0.94) M: 0.33 (0.19 to 0.56)

Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 0.43 (95% CI 0.34 to 0.55) favoring Ondansetron Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

2. Time to rehydration Not reported

3. Need for nasogastric tube/rehydration Not reported

4. Need for hospitalization (incidence of hospitalization within eight hours after the administration of the treatment)

Effect measure: RR (95% CI: C: 0.80 (0.22 to 2.90) E: 0.56 (0.27 to 1.13) G: 0.50 (0.24 to 1.01) L: 0.21 (0.05 to 0.93) K: 0.46 (0.13 to 1.69)

Pooled effect (random effects model / fixed effects model): RR 0.49 (95% CI 0.32 to 0.75) favoring Ondansetron Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

5. Length of hospital stay Not reported

6. Intravenous rehydration during the ED stay Effect measure: RR (95% CI: B: 0.56 (0.30 to 1.07) C: 0.45 (0.26 to 0.79) D: 0.74 (0.34 to 1.58) G: 0.41 (0.23 to 0.72) H: 0.39 (0.16 to 0.94) I: 0.26 (0.08 to 0.83) K: 0.34 (0.18 to 0.65) M: 0.20 (0.01 to 4.00)

Pooled effect (random effects model ): RR 0.44 (95% CI 0.34 to 0.57) favoring Ondansetron Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

7. Return visit to the ED Effect measure: RR (95% CI: C: 1.08 (0.59 to 1.95) D: 1.87 (0.18 to 19.84) G: 0.84 (0.39 to 1.80) H: 8.64 (0.47 to 157.62) K: 1.40 (0.25 to 7.97)

Pooled effect (random effects model / fixed effects model): RR 1.14 (95% CI 0.74 to 1.76) favoring Ondansetron Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

8. Weight loss Not reported

9. Vomiting (Cessation of vomiting within 8 hours after the administration of the treatment) Effect measure: RR (95% CI): C: 1.31 (1.12-1.54) D: 1.06 (0.97-1.15) E: 1.05 (0.94-1.19) G: 1.42 (1.20-1.69) H: 1.33 (1.10-1.62) I: 3.25 (1.63-6.45) J: 3.33 (1.85-6.01) K: 1.11 (0.84-1.47) M: 2.35 (1.19-1.68)

Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 1.41 (95% CI 1.19 to 1.68) favoring placebo Heterogeneity (I2): 86%

9. Vomiting (Cessation of vomiting 24 hours after the administration of the treatment) – not meta-analyzed Effect measure: RR (95% CI) A: 0.50 (95% CI 0.24 to 1.02) P=0.039

10. Diarrhea (number of diarrhea episodes 24 hours after the administration of the treatment) – not meta-analyzed F (Hagbom, 2017) I: 3.75 (SD 7.15) C: 5.68 (SD 8.50) Mann-Whitney U-test p=0.063

I (Rang, 2019) I: median (IQR) 5 (2 to 18) C: median 6 (1 to 18) P=0.913

11. Complications

B Golshekan (2013): mentioned but not reported

Any B (Danewa, 2016) I 0/84 C 0/83

Cough A (Cubeddu, 1997) I: 3/12 C: 0/12 (0%)

Development of macular rash H (Ramsook, 2002) I: 1/74 C: 0/71 (0%)

Diarrhea, 24 hours F (Rang, 2019) I: median 5 (IQR: 2-18) C: 6 (1-18) H (Ramsook, 2002) I: 64/74 C: 54/71 P=0.02

Diarrhea, 48 hours H (Ramsook, 2002) I: 62/74 C: 51/71 P=0.015 G (Marchetti 2016) I: 49/118 C: 51/119 RR 1.10 (95% CI: 0.74 to 1.64)

Episodes of diarrhea during ORT C (Freedman, 2006) I: 1.4 C: 0.5 P<0.001

Abdominal distension M (Yilmaz, 2010) P=0.04 à not further specified.

|

Facultative:

Author’s conclusion: Mixed evidence suggests that ondansetron affects cessation of vomiting, oral rehydration therapy failures, need for intravenous rehydration, and hospitalization prevention in children with acute gastroenteritis. No differences could be examined in adverse events as the number of studies presenting these outcomes in a homogenous way was limited, and further studies are necessary.

Remark on Danewa: they reported no adverse events, and that they did “not observe any increase in diarrhea with odansetron use” |

Quality assessment

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/not applicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Fugetto, 2020 |

Yes

The objective of this meta-analysis was to provide up-to-date evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of a single dose of ondansetron versus placebo prescribed for vomiting due to acute gastroenteritis in children and adolescents. |

Yes

Electronic databases were searched to identify relevant studies published up to November 2019, including MEDLINE (PubMed), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Scopus (Elsevier). Reference lists of select- ed reviews, original articles, textbooks, organizations’ websites, and guideline clearinghouses were scanned in order to find additional articles. Investigators and corresponding authors were contacted to seek information about unpublished/incomplete studies. A snowball technique was applied to the search strategy

|

Yes

Thirteen placebo-controlled, double-blinded, peer-reviewed publications (2146 pediatric patients) were included. We re- stricted the focus to RCTs evaluating ondansetron adminis- tered orally or IV at any dosage versus placebo and prescribed to terminate or reduce vomiting in children and adolescents. |

Yes

The trials were conducted in different countries and over different periods. Two RCTs included hospitalized patients,, while the remaining were carried out in emergency departments. The inclusion criteria for enrolment were similar for all studies, and the age of participants ranged from 3 months to 16 years. All studies included subjects with none to moderate dehydration, except four in which hydration status was not specified. |

Not applicable |

Yes

Substantial heterogeneity was found among the studies in- cluded in the primary outcome analysis. Using random- effects analysis, it was found that at least a part of the heterogeneity was due to differences in age and proportion of males included in the population in each RCT. There was some asymmetry observed in the funnel plot for the primary study outcome analysis, suggesting possible publication bias or small study effects |

Yes

|

Yes

There was some asymmetry observed in the funnel plot for the primary study outcome analysis, suggesting possible publication bias or small study effects |

Yes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

|

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? a

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?b

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?c

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?d

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?e

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?f

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measureg

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Cubeddu, 1997 |

No information

Reason: “Patients were randomly assigned to receive either....”. |

Defenitely yes;

Reason: “The study medication was prepared by a pharmacist not involved in patient care...".

|

No information

Reason: Measures used to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received and information relating to whether the intended blinding was effective not provided. |

Probably yes;

Reason: All data appear to have been reported in the study outcomes. |

Defenitely yes;

Reason: No evidence of selective reporting. Outcomes listed in the methods section were comparable to those reported. |

Definitely no;

Reason: The authors reported a baseline imbalance in age; weight; and height between the ondansetron and placebo treatment arm. This imbalance was not adjusted for in the analysis.

Fecal analysis performed: 4 samples resulted positive for bacteria and 1 for both bacteria and virus among the intervention group, while 2 samples result positive for bacteria among placebo group. All patients were included in final analysis.

The trialists reported that the study was supported by Glaxo Wellcome and although the level of support was unclear two of the investigators were in the employment of Glaxo Wellcome.

|

SOME CONCERNS |

|

Danewa, 2016 |

Probably yes;

Reason: "Computer-generated block randomization with variable block sizes was used to assign patients...". |

Probably yes;

Reason: "Bottles were coded with this randomization scheme by a person not directly involved with the study". |

Probably yes;

Reason: "Study subjects, their caregivers, the person assigning intervention, doctors managing the patient, and outcome assessors were blinded ...". |

Probably yes

Reason: The authors indicated that they followed the intention to treat principle. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Outcomes listed in the methods section comparable to the reported results. No evidence of selective choice of data for outcomes. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Apparently free of other bias. |

LOW |

|

Freedman, 2006 |

Probably yes;

Reason: “The patients were randomly assigned in blocks of six to receive Ondansetron or placebo and were stratified according to the dose of medication”. “An independent statistician provided the code to the pharmacy”. |

Probably yes;

Reason: “An independent statistician provided the code to the pharmacy, which dispensed in an opaque bag a weight-appropriate dose of active drug or placebo”. |

Probably yes;

Reason: “active drug or placebo of similar taste and appearance". |

Probably yes;

Reason: The authors indicated that they followed the intention to treat principle. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Outcomes listed in the methods section comparable to the reported results. No evidence of selective choice of data for outcomes. |

No information;

Reason: Although no potential conflicts of interest were reported, this trial was supported partly by a grant from GlaxoSmithKline but the level of support was not declared. The risk of ’other bias’ was therefore judged unclear. |

LOW |

|

Freedman, 2018 |

Probably yes;

Reason: "... Randomization was stratified by study center and age (<18 and >18 months), using variable block sizes of 4 to 6...". |

Probably yes;

Reason: " Allocation was concealed through the use of an Internet-based randomization service...". |

Probably yes;

Reason: "A prespecified computer-generated randomization list with associated kit numbers was sent directly to the University of Calgary research pharmacist from http://www.randomize.net through password-protected files. At patient enrollment, http://www.randomize.net randomly assigned treatment and then randomly selected a kit number containing..." "Patients, treating physicians, investigators, and data assessors were masked...".

"Patients, treating physicians, investigators, and data assessors were masked...". |

Probably yes;

Reason: The Authors indicated no lost on follow-up or excluded from the final analysis. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Outcomes listed in the methods section comparable to the reported results. No evidence of selective choice of data for outcomes. |

Probably no;

Reason: Only children without evidence of dehydration assessed with the WHO dehydration tool were included in this study, The Authors state that this population was important to study because they believed they were at lower risk of potential complications associated with ondansetron administration compared with children who are dehydrated because the latter group is more likely to have electrolyte abnormalities and perhaps more likely to receive intravenous rehydration without a proper trial of oral rehydration therapy. Many study participants were coadministered with other medications, including antibiotic and antiemetic agents including domperidone. |

SOME CONCERNS |

|

Golshekan, 2013 |

Probably yes;

Reason: "The patients were randomized in two groups by computer randomization using a block of two...". |

Probably yes;

Reason: "The patients were randomized in two groups by computer randomization using a block of two...". |

Probably yes;

Reason: "The patients were randomized in two groups by computer randomization using a block of two..." "Also investigators were blinded to group assignment until after complete statistical analysis".

"Also investigators were blinded to group assignment until after complete statistical analysis".

|

Probably yes;

Reason: The authors indicated that they followed the intention to treat principle. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Outcomes listed in the methods section comparable to the reported results. No evidence of selective choice of data for outcomes. |

Probably no;

Reason: Hydration status of included children not known. |

SOME CONCERNS |

|

Hagbom, 2017 |

Probably yes;

Reason: " Randomization was done in blocks (n = 8) and the code key was sealed...".

|

Probably yes;

Reason: "Drug and placebo were labeled blinded with A or B and a randomization list was...". |

Probably yes;

Reason: "Children who met the inclusion criteria and whose parents or guardians gave written consent to participate in the study were examined by a physician and randomized by a nurse into ondansetron or placebo treatment, blinded as A or B solution".

"A blinded member of the study team, located at Linko¨ping University in Sweden, phoned the guardian 24–72 hour". |

Probably no;

Reason: In the absence of an intention-to-treat analysis, losses to follow-up resulted in incomplete data for several of the outcomes which were pre-specified. |

Probably no;

Reason: The addition of a secondary endpoint after treatment was introduced from the 21st participant and forward could have had serious and invaluable effects on final analyses. |

Probably no;

Reason: The study randomized patients before their full eligibility had been ascertained which resulted in 4 patients dropping out. |

HIGH |

|

Marchetti, 2016 |

Probably yes;

Reason: "Patients were randomly assigned in fixed blocks of nine".

|

Probably yes;

Reason: "The randomization procedure was centralized. The randomization sequence was transmitted to the pharmaceutical development service (Monteresearch S.r.l.), that prepared an...".

|

Probably yes;

Reason: "The randomization procedure was centralized. The randomization sequence was transmitted to the pharmaceutical development service (Monteresearch S.r.l.), which prepared and sent directly to participating hospitals, active drugs and placebo in closed, opaque and consecutively numbered bags. Drug preparations were indistinguishable...".

"The randomization procedure was centralized. The randomization sequence was transmitted to the pharmaceutical development service (Monteresearch S.r.l.), which prepared and sent directly to participating hospitals, active drugs and placebo in closed, opaque and consecutively numbered bags. Drug preparations were indistinguishable...".

|

Probably yes;

Reason: The authors indicated that they followed the intention to treat principle. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Outcomes listed in the methods section comparable to the reported results. No evidence of selective choice of data for outcomes. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Apparently free of other bias. |

LOW |

|

Ramsook, 2002 |

Probably yes;

Reason: "random allocation procedure was designed using standard random number allocation tables".

|

Probably yes;

Reason: "The pharmacy research section assigned treatment or placebo according to this individual randomization”. “The pharmacy team was not privy to the enrolled patients or the outcome measures. This code remained locked within the pharmacy research section and was broken and revealed to the investigators only at the close of the study". |

Probably yes;

Reason: "the pharmacy provided the drug or a color, taste, and odor-matched placebo in identical packaging.".

"This code remained locked within the pharmacy research section and was broken and revealed to the investigators only at the close of the study". |

Probably yes;

Reason: The authors indicated that they followed the intention to treat principle. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Outcomes listed in the methods section comparable to the reported results. No evidence of selective choice of data for outcomes. |

No information

Reason: This trial was supported partly by a grant from GlaxoSmithKline but the level of support was not declared. The risk of ’other bias’ was therefore judged unclear. |

LOW |

|

Rang, 2019 |

Probably yes;

Reason: "The random number sequence was generated in Excel". |

No information

Reason: Not specified. |

Probably yes;

Reason: "The treatment assignments were concealed in opaque, sealed envelopes".

" ... both drug and placebo were provided in the same volume (10 mL) in syringes, with code numbers, by a clinical pharmacist". |

Probably yes;

Reason: No attrition bias detected. |

No information

Reason: Outcomes listed in the methods section comparable to the reported results. No evidence of selective choice of data for outcomes. |

No information

Reason: The treating physicians prescribed anti-diarrheal medications such as smectite or racecadotril for some patients, which could have affected the duration of emesis and diarrhea. The sample size may have been inadequate to detect small differences in some outcomes, especially adverse effects. |

SOME CONCERNS |

|

Rerksuppaphol, 2010 |

Probably yes;

Reason: "Participants were randomized in two groups by a computerized program using a block of two".

|

No information

Reason: Not explained in the text. |

No information

Reason: Not explained in the text. |

Probably yes;

Reason: The authors indicated that they followed the intention to treat principle. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Outcomes listed in the methods section comparable to the reported results. No evidence of selective choice of data for outcomes. |

No information

Reason: It is not clear if the two randomized groups are similar in initial dehydration grade. |

SOME CONCERNS |

|

Roslund, 2008 |

Probably yes;

Reason: " patients were randomized to receive oral Ondansetron or placebo”, “block randomization of 10".

|

No information

Reason: "Each subject was assigned a packet with a corresponding number. Each packet contained a tracking form used for documenting the subject’s course in the ED".

|

Probably yes;

Reason: "[placebo] looked smelled and tasted like ondansetron..." "The packets were prefilled (oral ondansetron or placebo)..." "The markings on the blister pack were obscured...".

"healthcare providers were the assessors during the study and the research nurse, who was blinded to the treatment allocation, completed the follow-up for the study.".

|

Probably no;

Reason: Trialists considered different denominators (n= 51 and n=48) in the ondansetron group when presenting the outcomes. Post-discharge informations not available. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Outcomes listed in the methods section comparable to the reported results. No evidence of selective choice of data for outcomes. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Apparently free of other bias. |

SOME CONCERNS |

|

Stork, 2006 |

Probably yes;

Reason: "Randomization was performed in the pharmacy using specific instructions to access a provided table of random numbers to identify the patient’s study group".

|

Probably yes;

Reason: "Randomization was performed in the pharmacy". |

Probably yes;

Reason: "all study drug dispensed was uniform in design and color".

The healthcare providers were the assessors but blinding was ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

Probably no;

Reason: Losses to follow-up and missing data for several outcomes. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Outcomes listed in the methods section comparable to the reported results. No evidence of selective choice of data for outcomes. |

Probably no;

Reason: The study randomized patients before their full eligibility had been ascertained which resulted in 19 patients dropping out and a further 10 being discharged shortly after randomization.

|

SOME CONCERNS |

|

Yilmaz, 2010 |

Probably yes;

Reason: "computerized randomization codes .. in blocks of six".

|

Probably yes;

Reason: "...by a statistician who was not one of the investigators of this study..." "Code numbers were written on the injectors and...drawn up...by a pharmacist who was not one of the investigators in this study.".

|

Probably yes;

Reason: "orally disintegrating Ondansetron tablets dissolved.. and identical-looking placebo liquid”. “The subjects, parents, study personnel and other medical staff were blinded to which study drug was given".

" identical-looking"...."study personnel and other medical staff were blinded to which study drug was given". |

Probably no;

Reason: Two participants in the placebo group were removed from the study after receiving IV rehydration and were admitted to the hospital but were not included in the analysis. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Outcomes listed in the methods section comparable to the reported results. No evidence of selective choice of data for outcomes. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Apparently free of other bias. |

SOME CONCERNS |

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Niño-Serna (2020) |

Fugetto (2020) is a higher quality SR. |

|

Tomasik (2016) |

Fugetto (2020) is a more recent SR. |

|

Das (2013) |

Fugetto (2020) is a more recent SR. |

|

Carter (2012) |

Fugetto (2020) is a more recent SR. |

|

Fedorowicz (2011) |

Fugetto (2020) is a more recent SR. |

|

Dalby-Payne (2011) |

Fugetto (2020) is a more recent SR. |

|

DeCamp (2008) |

Fugetto (2020) is a more recent SR. |

|

Szajewska (2007) |

Fugetto (2020) is a more recent SR. |

|

Vreeman (2008) |

Wrong publication type: commentary. |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 02-08-2023

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 28-06-2023

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2020 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor kinderen met dehydratie.

Samenstelling van de werkgroep

- Drs. C.C. (Chris) de Kruiff, kinderarts, Amsterdam UMC te Amsterdam, NVK (voorzitter)

- Dr. T. (Tessa) Sieswerda, kinderarts, Amsterdam UMC te Amsterdam, NVK (vice-voorzitter)

- E.M. (Eiske) Dorresteijn, kindernefroloog, Erasmus MC te Rotterdam, NVK

- S.G.J. (Sabien) Heisterkamp, kinderintensivist, LUMC te Leiden, NVK

- Drs. P. (Paul) Vos, kinderarts, Hagaziekenhuis te ’s Gravenhage, NVK

- Dr. M.M. (Eva) Hoytema-van Konijnenburg, metabool kinderarts, Wilhelmina Kinderziekenhuis te Utrecht, NVK

- S. (Symona) Bout, kinderverpleegkundige, Groene Hart Ziekenhuis te Gouda, V&VN

- A. (Anne) Swinkels, beleidsmedewerker, Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis te Utrecht, Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

de Kruiff |

Kinderarts algemene pediatrie, Hoofd vakgroep algemene kindergeneeskunde, Amsterdam UMC |

Redactielid Praktische Pediatrie, waarvoor honorarium ontvangen wordt |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Sieswerda |

Kinderarts algemene pediatrie. Per 1-8-2020 fellow sociale pediatrie AUMC |

Lid werkgroep Richtlijnen NVK, onbetaald Vice voorzitter revisie richtlijn bronchiolitis, onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Dorresteijn |

Kindernefroloog ErasmusMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Hoytema-van Konijnenburg |

AIOS kindergeneeskunde AmsterdamUMC. Per 2022 fellow metabole ziekten UMC Utrecht |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Bout |

HCN vpk en kindervpk in het Groene hart ziekenhuis Te Gouda kwaliteitsmedewerker aandachtsvelder kindermishandeling PAP coach (patient als partner) |

Vrijwilliger zonnebloem en organisator voor collecte brandwondenstichting |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Heisterkamp |

Kinder-intensivist LUMC |

Lid NVK werkgroep richtlijn astma Instructeur SSHK – APLS |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Vos |

Kinderarts en Kindernefroloog, Hagziekenhuis, locatie Juliana Kinderziekenhuis |

Lid NVK, Lid sectie kindernefrologie NVK, APLS instructeur Stichting spoedeisende hulp bij kinderen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Doganer Vanaf 01-06-2022 |

Junior projectmanager en beleidsmedewerker |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Pingen tot 01-12-2020 |

Junior projectmanager en beleidsmedewerker |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Uitzinger vanaf 01-12-2020 tot 01-06-2022 |

Junior projectmanager en beleidsmedewerker |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Klankbordgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Haandrikman |

Kinderverpleegkundige in Tergooi ziekenhuizen Blaricum |

Werkgroep protocollen Werkgroep pijn Werkgroep pijn en angstreductie bij kinderen Werkgroep zorgzwaarte |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Thole |

AIOS SEH regio ZuidWest Nederland, locatie Albert Schweitzer Ziekenhuis |

ALS trainer voor in-house trainingen Albert Schweitzer Ziekenhuis (betaald). Huisarts, niet-praktiserend (niet actief) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Elshout |

Huisarts, Huisartsenpraktijk Elshout en De Vos. Adjunct coördinator Bachelor geneeskunde Erasmus MC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Wessels |

Is opgevraagd |

|

|

|

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis voor de invitational conference en een afgevaardigde van Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis in de werkgroep. Het verslag van de invitational conference is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de patiëntenvereniging en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Methode inschatten ernst dehydratie |

geen financiële gevolgen |

<5,000 patiënten |

|

Module Intraveneuze volumesuppletie bij dehydratie |

geen financiële gevolgen |

<5,000 patiënten |

|

Module Vaatvulling bij dehydratie |

geen financiële gevolgen |

<5,000 patiënten |

|

Module Wat is de beste vloeistof om oraal te geven bij (dreigende) dehydratie door gastro-enteritis? |

geen financiële gevolgen |

<5,000 patiënten |

|

Module Anti-emetica bij braken |

geen financiële gevolgen |

<5,000 patiënten |

De kwalitatieve raming volgt na de commentaarfase.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor kinderen met dehydratie. De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbeveling(en) uit de eerdere richtlijnmodule (Nederlandse Vereniging voor Kindergeneeskunde, 2012) op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door medisch specialisten en verpleegkundigen door middel van een invitational conference.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.