Tromboseprofylaxe op de verpleegafdeling bij COVID-19

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van tromboseprofylaxe bij COVID-19 patiënten op de verpleegafdeling?

Aanbeveling

Geef antistolling aan patiënten met COVID-19 op de verpleegafdeling en overweeg hierbij een standaard profylactische of intermediaire dosis LMWH, omdat de huidige bewijslast geen overtuigende meerwaarde aantoont van therapeutische antistolling.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de verschillen in klinische uitkomsten tussen 1) behandeling met therapeutische dosis antistolling versus standaard of intermediaire dosis tromboseprofylaxe, en 2) behandeling met intermediaire dosis tromboseprofylaxe versus standaard dosis tromboseprofylaxe, bij patiënten met COVID-19 op de verpleegafdeling. Tot op heden zijn 5 RCTs gevonden die de vergelijking in de eerste PICO – therapeutische dosis versus standaard of intermediaire dosis - hebben onderzocht. Er zijn geen studies gevonden die de vergelijking in de tweede PICO – intermediaire dosis versus standaard dosis - hebben onderzocht. Voor de uitwerking van de studies is naast een analyse van alle studies samen een onderverdeling gemaakt tussen de interventie met low-molecular-weight heparines (LMWHs) en/of ongefractioneerde heparines (UFHs) en de interventie met directe orale anticoagulantia (DOACs).

Cruciale uitkomstmaten

Op basis van de gevonden resultaten zou het gebruik van een therapeutische dosis antistolling met een LMWH/UFH kunnen resulteren in geen tot een klein verschil in mortaliteit vergeleken met een standaard of intermediaire dosis tromboseprofylaxe met heparine. Daarentegen lijkt het effect van het gebruik van een therapeutische dosis antistolling met een DOAC vergeleken met een standaard of intermediaire dosis tromboseprofylaxe met heparine de andere kant op te gaan: dit zou kunnen resulteren in een verhoogde mortaliteit. De bewijskracht voor beide subgroepen is laag.

Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat veneuze trombo-embolie is het onduidelijk of een behandeling met therapeutische dosis antistolling met een LMWH/UFH of DOAC zou kunnen leiden tot een reductie in het optreden van veneuze trombo-embolie. De bewijskracht hiervoor is zeer laag. Als naar alle trombo-embolische complicaties tezamen wordt gekeken, kan er worden geconcludeerd dat gebruik van een therapeutische dosis antistolling met een LMWH/UFH zou kunnen resulteren in geen tot een klein verschil in het optreden van trombo-embolische complicaties vergeleken met een standaard profylactische of intermediaire dosis heparine. De bewijskracht is laag. Het is onduidelijk of een behandeling met therapeutische dosis met een DOAC zou kunnen leiden tot een reductie in het optreden van trombo-embolische complicaties vergeleken met een standaard of intermediaire dosis profylaxe met LMWH/UFH. De bewijskracht hiervoor is zeer laag.

Hetzelfde patroon gaat op voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat ernstige bloeding. Voor deze uitkomstmaat kan worden geconcludeerd dat het gebruik van een therapeutische dosis antistolling met een LMWH/UFH zou kunnen resulteren in geen tot een klein verschil in het optreden van een ernstige bloeding vergeleken met een standaard of intermediaire dosis tromboseprofylaxe met heparine. De bewijskracht is laag. Het is onduidelijk of een behandeling met therapeutische dosis met een DOAC zou kunnen leiden tot een toename in het optreden van een ernstige bloeding, vergeleken met een standaard of intermediaire dosis profylaxe met heparine. De bewijskracht hiervoor is zeer laag.

Belangrijke uitkomstmaten

Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaat duur van ziekenhuis opname is geen bewijs gevonden voor de vergelijking tussen een therapeutische dosis met een LMWH/UFH en het gebruik van een standaard of intermediaire dosis tromboseprofylaxe met heparine. Voor de vergelijking tussen therapeutische dosis met een DOAC vergeleken met een standaard profylactische of intermediaire dosis heparine stelt de literatuur dat het gebruik van therapeutische dosis met een DOAC mogelijk zou kunnen resulteren in geen tot een klein verschil in de duur van ziekenhuis opname vergeleken met het gebruik van een standaard profylactische of intermediaire dosis heparine. De bewijskracht hiervoor was redelijk.

Voor opname op de intensive care unit (ICU) stelt de literatuur dat het gebruik van therapeutische dosis met een LMWH/UFH zou kunnen resulteren in geen tot een klein verschil in opname op de ICU vergeleken met het gebruik van een standaard of intermediaire dosis profylaxe met heparine. De bewijskracht hiervoor is laag. Er is geen bewijs gevonden voor de vergelijking tussen therapeutische dosis met een DOAC vergeleken met een standaard profylactische of intermediaire dosis met heparine.

Voor het aantal dagen overleving zonder orgaan ondersteuning stelt de literatuur dat het gebruik van therapeutische dosis met een LMWH/UFH zou kunnen resulteren in geen tot een klein verschil in het aantal dagen overleving zonder orgaan ondersteuning, vergeleken met het gebruik van een standaard of intermediaire dosis tromboseprofylaxe met heparine. De bewijskracht hiervoor is redelijk. Er is geen bewijs gevonden voor de vergelijking tussen therapeutische dosis met een DOAC vergeleken met een standaard of intermediaire dosis tromboseprofylaxe met heparine. Als wordt gekeken naar intubatie en mechanische ventilatie kan geconcludeerd worden dat het gebruik van zowel een therapeutische dosis met een LMWH/UFH als met een DOAC zou kunnen resulteren in geen tot een klein verschil in intubatie/mechanische ventilatie, vergeleken met het gebruik van een standaard of intermediaire dosis tromboseprofylaxe met heparine. De bewijskracht voor beide is redelijk.

Interpretatie

De interpretatie van de studies is om meerdere redenen complex. Er zijn geen studies gevonden die apart een therapeutische dosis met een intermediaire dosis tromboseprofylaxe met heparine vergeleken. Daarnaast zijn er ook geen studies die apart een intermediaire dosis met een standaard dosis tromboseprofylaxe met heparine hebben vergeleken. Daarom kan in de aanbeveling geen onderscheid worden gemaakt tussen de standaard dosis en intermediaire dosis tromboseprofylaxe met heparine. Voor bepaalde subgroepen, zoals leeftijd of D-dimeer niveau bij presentatie, kon geen onderscheid worden gevonden in de analyse van de studies. Daarom konden er geen specifieke aanbevelingen worden gedaan voor deze subgroepen. Alle drie de cruciale uitkomsten waren secundaire uitkomsten in de studies. De studies hadden samengestelde primaire eindpunten die onderling onvergelijkbaar bleken. Zo werden bijvoorbeeld non-invasieve en invasieve beademing samen genomen, of sterfte en trombotische complicaties. Door deze verschillende samengestelde uitkomstmaten kon deze data niet gepoold worden. Verder zijn de studies in andere landen dan Nederland onder verschillende omstandigheden uitgevoerd. Het is bijvoorbeeld de vraag of de patiënten betrokken in studies die in andere landen zijn uitgevoerd (zoals Brazilië), vergeleken kunnen worden met Nederlandse patiënten. Een ander belangrijk punt van overweging is het feit dat de behandeling van patiënten met COVID-19 in 2021 in Nederland veranderd is ten opzichte van 2020, het jaar waarin de studies zijn verricht. Zo is er nu standaardbehandeling met hoge doses steroïden en IL-6 remmers. In verschillende van de gevonden studies kreeg een substantieel deel van de patiënten bijvoorbeeld geen behandeling met steroïden en werd slechts een kleine minderheid behandeld met IL-6 remmers. Alle studies hadden een zogenaamd ‘open label design’, waardoor bias kan zijn opgetreden bij zachtere uitkomstmaten als veneuze tromboembolie en bloeding. De artsen wisten welke behandeling een patiënt kreeg, hetgeen de klinische verdenking en diagnostische strategie heeft kunnen beïnvloeden. Eindpunten werden slechts deels centraal of lokaal geadjudiceerd, waardoor de validiteit van de diagnose longembolie (overgrote meerderheid van de trombotische events) niet in alle studies is na te gaan. De inclusiecriteria tussen de studies waren ook erg wisselend, met soms -maar niet altijd - selectie van patiënten met hoge tot zeer hoge D-dimeerwaarden. Patiënten met een van tevoren ingeschat hoog bloedingsrisico werden uitgesloten. De incidentie van bloedingscomplicaties zou daarom bij toepassing van therapeutische antistolling in de dagelijkse praktijk hoger kunnen uitvallen. Dit alles maakt dat er nog kennislacunes zijn. Het zal moeten blijken of resultaten van nieuwe studies de conclusies van de samenvatting van de literatuur zullen veranderen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Het doel van toedienen van antistolling is het voorkómen van veneuze en, in mindere mate, arteriële trombose. Er is geen verschil in toediening of impact van de standaard profylactische of intermediaire versus de therapeutische dosis LMWH; beide worden op dezelfde manier subcutaan geïnjecteerd. Er zijn geen subgroepen met andere uitkomsten gevonden.

Patiënten die een behandeling met medicijnen voor antistolling krijgen vinden complete en eenduidige informatievoorziening belangrijk, o.a. over de indicatie en de veiligheid en risico’s van de behandeling (onderwerpen die van belang zijn in de communicatie met patiënten zijn terug te vinden in de Landelijke Transmurale Afspraak antistollingszorg (https://lta-antistollingszorg.nl/communicatie-met-patienten).

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er is geen doorslaggevend verschil in de kosten voor de standaard profylactisch of therapeutisch gedoseerde LMWH of DOAC.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Door de opzet en uitkomsten van de onderzochte studies is geen definitief bewijs gevonden voor de cruciale uitkomsten. In de door de werkgroep gevoerde discussies kwamen verschillende visies naar voren. Uiteindelijk was er volgens de werkgroep geen overtuigend bewijs om de aanbevelingen aan te passen, zoals geformuleerd in de leidraad COVID-19 coagulopathie van april 2020, en om het gebruik van therapeutische antistolling als standaardbehandeling aan te bevelen.

Rationale van de aanbeveling

De individuele studies hadden vaak gecombineerde uitkomstmaten, waarbij niet-invasieve beademing, IC opname, intubatie, trombotische complicaties, ECMO, CVVH en sterfte in verschillende combinaties waren samengenomen. Bij de analyses van de individuele eindpunten bleek het potentiële voordeel van therapeutische antistolling onder de van tevoren vastgestelde grens van klinische relevantie te liggen. Het effect van een therapeutische dosis antistolling werd derhalve niet klinisch relevant bevonden ten opzichte van een standaard profylactische- of intermediaire dosis antistolling. Eerder waren voor de Nederlandse situatie geen grenzen van klinische relevantie vastgesteld voor het instellen van tromboseprofylaxe. De werkgroep heeft zich bij het vaststellen van die grenzen geconformeerd aan de grenzen voor sterfte en IC opname, zoals vastgesteld door de SWAB werkgroep voor medicamenteuze behandeling van COVID-19. De grens voor een klinisch relevant verschil in trombotische complicaties werd indirect afgeleid uit de ACCP richtlijn tromboseprofylaxe uit 2012. Uit de onderzochte studies bleek ook dat therapeutische antistolling niet klinisch relevant meer schade berokkende dan een standaard profylactische- of intermediaire dosis: het optreden van bloedingen bleek niet klinisch relevant verschillend tussen de groepen. De werkgroep kwam na uitvoerige discussie in meerderheid, maar niet unaniem, tot de conclusie dat er geen grond is om af te wijken van de huidige standaard behandeling, zoals omschreven in de leidraad COVID-19 coagulopathie van april 2020 en de richtlijnmodules cardiovasculaire complicaties bij COVID-19 van maart 2021.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Ondanks tromboseprofylaxe en een verbeterde behandeling van COVID-19 komen trombotische complicaties nog frequent voor, met een geschatte incidentie van 23-28% in ICU patiënten en 7-9 % in afdelingspatiënten (Jiménez, 2021; Tan, 2021; Nopp, 2021). Het is niet bekend wat de beste dosis van tromboseprofylaxe is (laag, intermediair of therapeutisch). Mede hierdoor verschillen ziekenhuisprotocollen.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Mortality

Therapeutic dose LMWHs/UFHs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose anticoagulation LMWHs/UFHs

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with therapeutic anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs may result in little to no difference in mortality when compared to standard prophylactic/intermediate anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital ward (not ICU).

Sources: Lawler, 2021; Sholzberg, 2021; Marcos, 2021. |

Therapeutic dose DOACs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose LMWHs/UFHs

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with therapeutic anticoagulation with DOACs may result in an increase in mortality when compared to standard prophylactic/intermediate anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital ward (not ICU).

Source: Lopes, 2021 |

Total group

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with therapeutic anticoagulation on mortality when compared to standard prophylactic/intermediate anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital ward (not ICU).

Sources: Lawler, 2021; Sholzberg, 2021; Marcos, 2021; Lopes, 2021. |

2. Length of hospital stay

Therapeutic dose LMWHs/UFHs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose anticoagulation LMWHs/UFHs

|

- GRADE |

No studies were found that could answer the question what the effect is of therapeutic anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs when compared to standard prophylactic/intermediate anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs on hospital length of stay in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital ward (not ICU).

|

Therapeutic dose DOACs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose LMWHs/UFHs

|

Moderate GRADE |

Treatment with therapeutic anticoagulation with DOACs likely results in little to no difference in length of hospital stay when compared to standard prophylactic/intermediate anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital ward (not ICU).

Source: Lopes, 2021. |

3. ICU-admission (yes/no)

Therapeutic dose LMWHs/UFHs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose anticoagulation LMWHs/UFHs

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with therapeutic anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs may result in little to no difference in ICU-admission when compared to standard prophylactic/intermediate anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital ward (not ICU).

Sources: Sholzberg, 2021; Marcos, 2021. |

Therapeutic dose DOACs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose LMWHs/UFHs

|

- GRADE |

No studies were found that could answer the question what the effect is of therapeutic anticoagulation with DOACs when compared to standard prophylactic/intermediate anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs on ICU-admission in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital ward (not ICU).

|

4. Organ support

Organ support free days

Therapeutic dose LMWHs/UFHs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose anticoagulation LMWHs/UFHs

|

Moderate GRADE |

Treatment with therapeutic anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs likely results in little to no difference in organ support free days when compared to standard prophylactic/intermediate anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital ward (not ICU).

Source: Sholzberg, 2021. |

Therapeutic dose DOACs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose LMWHs/UFHs

|

- GRADE |

No studies were found that could answer the question what the effect is of therapeutic anticoagulation with DOACs when compared to standard prophylactic/intermediate anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs on organ support free days in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital ward (not ICU). |

Organ support (intubation or mechanical ventilation)

Therapeutic dose LMWHs/UFHs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose anticoagulation LMWHs/UFHs

|

Moderate GRADE |

Treatment with therapeutic anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs likely results in little to no difference in organ support (intubation or mechanical ventilation) when compared to standard prophylactic/intermediate anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital ward (not ICU).

Sources: Lawler, 2021; Sholzberg, 2021. |

Therapeutic dose DOACs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose LMWHs/UFHs

|

Moderate |

Treatment with therapeutic anticoagulation with DOACs likely results in little to no difference in organ support (intubation or mechanical ventilation) when compared to standard prophylactic/intermediate anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital ward (not ICU).

Source: Lopes, 2021. |

Total group

|

Moderate GRADE |

Treatment with therapeutic anticoagulation likely results in little to no difference in organ support (intubation or mechanical ventilation) when compared to standard prophylactic/intermediate anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital ward (not ICU).

Sources: Lawler, 2021; Sholzberg, 2021; Lopes, 2021. |

5. Venous thromboembolism

Therapeutic dose LMWHs/UFHs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose anticoagulation LMWHs/UFHs

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with a therapeutic anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs on venous thromboembolism when compared to standard prophylactic/intermediate anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital ward (not ICU).

Source: Sholzberg, 2021. |

Therapeutic dose DOACs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose LMWHs/UFHs

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with a therapeutic anticoagulation with DOACs on venous thromboembolism when compared to standard prophylactic/intermediate anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital ward (not ICU).

Source: Lopes, 2021. |

Thromboembolic complications (VTE/ATE)

Therapeutic dose LMWHs/UFHs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose anticoagulation LMWHs/UFHs

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with therapeutic anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs may result in little to no difference on thromboembolic complications (VTE/ATE) when compared to standard prophylactic/intermediate anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital ward (not ICU).

Sources: Lawler, 2021; Sholzberg, 2021; Marcos, 2021. |

Therapeutic dose DOACs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose LMWHs/UFHs

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with a therapeutic anticoagulation with DOACs on thromboembolic complications (VTE/ATE) when compared to standard prophylactic/intermediate anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital ward (not ICU).

Source: Lopes, 2021. |

Total group

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with therapeutic anticoagulation may result in little to no difference on thromboembolic complications (VTE/ATE) when compared to standard prophylactic/intermediate anticoagulation LMWHs or UFHs in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital ward (not ICU).

Sources: Lawler, 2021; Sholzberg, 2021; Marcos, 2021; Lopes, 2021. |

6. Major bleeding

Therapeutic dose LMWHs/UFHs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose anticoagulation LMWHs/UFHs

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with therapeutic anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs may result in little to no difference in major bleeding when compared to standard prophylactic/intermediate anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital ward (not ICU).

Sources: Lawler, 2021; Spyropoulos, 2021; Sholzberg, 2021; Marcos, 2021. |

Therapeutic dose DOACs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose LMWHs/UFHs

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with a therapeutic anticoagulation with DOACs on major bleeding when compared to standard prophylactic/intermediate anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital ward (not ICU).

Source: Lopes, 2021. |

Total group

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with therapeutic anticoagulation may result in little to no difference in major bleeding when compared to standard prophylactic/intermediate anticoagulation with LMWHs or UFHs in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital ward (not ICU).

Sources: Lawler, 2021; Spyropoulos, 2021; Sholzberg, 2021; Marcos, 2021; Lopes, 2021. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies: treatment with unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin in hospitalized COVID-19 patients

Lawler (2021) describes an open-label, international, adaptive, multiplatform RCT (mpRCT). In this mpRCT, three platforms (REMAPCAP, ATTACC and ACTIV-4a) evaluating therapeutic-dose anticoagulation with heparin were integrated. Patients were enrolled at 121 sites in 9 countries (the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Brazil, Mexico, Nepal, Australia, the Netherlands, and Spain) over a period of 8 months (April 2020-Jan 2021). A total of 1181 patients in the intervention group received a continuous intravenous therapeutic-dose anticoagulation with unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin up to 14 days or to hospital discharge and 1050 patients in the control group received usual-care thromboprophylaxis up to 14 days or hospital discharge (see evidence table for details about anticoagulation and thromboprophylaxis regimens). The study included hospitalized, non-critically ill COVID-19 patients, defined by the absence of critical care–level organ support at enrollment. The study population in the intervention group had a mean age of 59 years (SD 14.1) versus 58.8 years (SD 13.9) in the control group and the majority was male (60% in the intervention versus 57% in the control group). The study groups were balanced with respect to baseline characteristics. The length of follow-up was 28 to 90 days.

Spyropoulos (2021) describes a multicenter open label RCT evaluating the effects of therapeutic-dose low-molecular-weight heparin versus institutional standard prophylactic dose or intermediate-dose heparins for thromboprophylaxis in high-risk hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Patients were enrolled from March 8, 2020, through May 14, 2021, at 12 centers in the US. A total of 11649 patients were assessed for eligibility. Eligible patients consisted of hospitalized nonpregnant adults 18 years or older with COVID-19 diagnosed by nasal swab or serologic testing. Moreover, there was a requirement for supplemental oxygen per investigator judgment and a plasma D-dimer level greater than 4 times the upper limit of normal based on local laboratory criteria or a sepsis-induced coagulopathy score of 4 or greater. Two hundred and fifty-seven patients were randomized into the therapeutic dose group (n= 130) or standard prophylactic/intermediate dose group (n = 127). However, a part of these patients were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU): 45 out of 129 patients in the therapeutic dose group and 38 out of 124 in the standard prophylactic dose group. The results of the analyses of major bleeding were reported separately based on ICU status. Treatment began after randomization and was stopped at hospital discharge or upon occurrence of a primary efficacy outcome, key secondary outcome, or principal safety outcome requiring study drug discontinuation. All patients without a primary or key secondary outcome event underwent lower extremity Doppler compression ultrasonography at hospital day 10 + 4 or at discharge if sooner. The length of follow-up was 30 +2 days after randomization. Patients in the therapeutic dose group had a mean age of 65.8 years (SD 13.9) versus 67.7 years (SD 14.1) in the standard prophylactic dose group and the small majority was male (52.7% in the intervention versus 54.8% in the control group). The study groups were comparable with respect to baseline characteristics. Because of the relatively great number of patients that were admitted to the ICU, only the outcome measure major bleeding was included in the current analysis.

Sholzberg (2021) described a randomized controlled, adaptive, open label clinical trial evaluating the effects of therapeutic unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin compared with standard prophylactic unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin among moderately ill patients with covid-19 and increased D-dimer levels admitted to hospital wards. Elevated D-dimer levels were defined as one D-dimer value above the upper limit of normal (within 5 days (i.e. 120 hours) of hospital admission), and either D-Dimer ≥2 times the upper limit of normal, or D-Dimer above the upper limit of normal and oxygen saturation ≤ 93% on room air. 465 adults were recruited between May 29, 2020, and April 12, 2021, at 28 hospitals in Brazil, Canada, Ireland, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and the US. Eligible patients were randomized into the therapeutic dose heparin group (n = 228) or the standard prophylactic dose heparin group (n=237). Treatments were continued until hospital discharge, day 28 of treatment, or death. Patients in the therapeutic dose group had a mean age of 60.4 years (SD 14.1) versus 59.6 years (SD 15.5) in the standard prophylactic dose group and the small majority was male (53.9% in the intervention versus 59.5% in the control group). The study groups were comparable with respect to baseline characteristics.

Marcos (2021) described an open-label, multicenter RCT in adult patients with non-severe COVID-19 pneumonia and elevated D-dimer >500 ng/mL, who were hospitalized in a conventional ward. Patients were recruited and randomized at five Spanish hospitals. Patients were allocated to either the experimental arm (n = 33), which consisted of bemiparin treatment 115 IU/kg one a day, or the control arm (n = 33), which was standard prophylaxis with subcutaneous bemiparin 3,500 IU one a day. Treatments were continued for a period of 10 days, independently of hospital discharge. Patients in the intervention group had a mean age of 62.3 years (SD 12.2), versus 63.0 years (SD 13.7) in the control group. In the intervention group, the fast majority was male (n = 24, 72.7%), versus a small majority in the control group (n = 17, 53.1%). Overall, there was a good balance between both study arms.

Description of study: treatment with DOAC in hospitalized COVID-19 patients

Lopes (2021) described a pragmatic, open-label, multicenter RCT in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and elevated D-dimer concentration (defined as D-dimer above the upper limit of normal) to assess whether in-hospital anticoagulation with rivaroxaban (20 mg once daily) for patients with a stable condition or enoxaparin (1 mg/kg twice daily) for patients with an unstable condition, followed by rivaroxaban for 30 days decreased the time to death, duration of hospitalization, or duration of supplemental oxygen support when compared with mainly in-hospital standard prophylactic dose anticoagulation with enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin. In total, 615 patients were allocated to receive the therapeutic anticoagulation or in-hospital standard prophylactic dose anticoagulation. Patients in the therapeutic group had a mean age of 56.7 years (SD 14.1), versus 56.5 years (SD 14.5) in the standard prophylactic group. The majority in both groups was male: 192 (62%) in the therapeutic group, versus 176 (58%) in the standard prophylactic dose group. At baseline, 23 out of 311 (7%) patients in the therapeutic dose group were defined as having a clinically unstable condition, versus 16 out of 304 (5%) patients in the standard prophylactic dose group. The study population contains a small number of clinically unstable patients (7%). This was taken into account when determining the level of evidence (indirectness).

Table 1. Overview of included RCTs that compared therapeutic dose anticoagulation with intermediate and/or standard dose anticoagulation in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, separated into subgroups

|

Author, year and trial name |

Intervention (I) and control (C) |

Sample size for analysis |

Doses of anticoagulants |

Follow-up |

||||

|

Therapeutic dose vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose – LMWH/UFH |

||||||||

|

Lawler, 2021 |

I: Therapeutic dose with LMWH or UFH |

I: N=1181 |

REMAP-CAP |

ACTIV-4a |

ATTACC |

REMAP-CAP |

ACTIV-4a |

ATTACC |

|

C: Usual-care thromboprophylaxis |

REMAP-CAP |

ACTIV-4a |

ATTACC |

REMAP-CAP |

ACTIV-4a |

ATTACC |

||

|

Spyropoulos, 2021 |

I: therapeutic-dose LMWH (enoxaparin) |

I: N= 129 |

I: 1 mg/kg subcutaneously twice daily if CrCl was 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 or greater or 0.5 mg/kg twice daily if CrCl was 15-29 mL/min/ 1.73 m2 |

Study drug was administered for the duration of hospitalization, including patient transfers to ICU settings |

||||

|

C: institutional standard prophylactic dose or intermediate-dose heparins for thromboprophylaxis |

C: could include UFH, up to 22 500 IU subcutaneously (divided twice or thrice daily); enoxaparin, 30 mg or 40 mg subcutaneously once or twice daily (weight based enoxaparin 0.5 mg/kg subcutaneously twice daily was permitted but strongly discouraged); or dalteparin, 2500 IU or 5000 IU subcutaneously daily |

|||||||

|

Sholzberg, 2021 |

I: therapeutic heparin (LMWH or UFH) – Enoxaparin, dalteparin, fondaparinux, tinzaparin, UFH |

I: N= 228 |

Specific dosages specified in trial protocol for each type of heparin, depending on creatinine clearance and BMI. (see Table 1 and 2 supplementary file) |

Therapeutic heparin: |

||||

|

C: standard prophylactic dose heparins (LMWH or UFH) – Enoxaparin, dalteparin, fondaparinux, tinzaparin, UFH |

||||||||

|

Marcos, 2021 |

I: bemiparin |

I: N= 33 |

I: 115 IU/Kg once daily, adjusted to body weight (7,500 IU for patients between 50-70 Kg; 10,000 IU for patients weighing >70-100 Kg; 12,500 IU for patients who weighed >100 Kg). |

The assigned treatments were planned for a 10-day period, independently of early hospital discharge. After that period, thromboprophylaxis use was left at investigators’ choice. In case of ICU requirement during the study treatment period, it was at the discretion of the treating physician to continue the study drug or not, according to local practices. |

||||

|

C: standard prophylaxis with subcutaneous bemiparin |

C: 3,500 IU once daily |

|||||||

|

Therapeutic dose vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose – DOAC |

||||||||

|

Lopes, 2021 |

I: therapeutic anticoagulation |

I: N= 311 |

I: Clinically stable patients = 20 mg once daily. A reduced dose of 15 mg once daily was used in patients with a creatinine clearance of 30–49 mL/min or those taking azithromycin. |

All patients in the therapeutic anticoagulation group continued treatment to day 30 with the same dose of rivaroxaban. |

||||

|

C: standard prophylactic dose anticoagulation – standard venous thromboembolism prophylaxis with enoxaparin or UFH during hospitalisation. Patients in this group could receive therapeutic anticoagulation if they developed a definitive clinical indication or at the discretion of the investigator if a high clinical suspicion of a thromboembolic event was raised and a confirmatory test was not available. |

C:? |

|||||||

Table 2. Overview of composite outcomes and results per study

|

Study |

Primary composite outcome |

Results |

|

Lawler (2021) Multiplatform trial |

Organ support free days as evaluated on an ordinal scale that combined in-hospital death and the number of days free of cardiovascular or respiratory organ support up to day 21 among patients who survived to hospital discharge. |

|

|

Sholzberg (2021) RAPID trial |

|

|

|

Spyropoulos (2021) HEP-COVID trial |

A composite of VTE, ATE, or death for the non-ICU stratum separately |

In the therapeutic dose heparin group, 14 out of 84 (16.7%) patients reported the composite outcome, versus 31 out of 86 (36.1%) patients in the standard prophylactic dose heparin group. The RD was 19.4% in favor of the therapeutic dose heparin group (95%CI -32.3% to 6.5%). |

|

Marcos (2021) BEMICOP trial |

A composite of death, admission at ICU, need of mechanical ventilation support, development of moderate/severe acute respiratory distress syndrome and venous or arterial thrombosis within 10 days |

In the therapeutic dose bemiparin group, 7 out of 32 (21.9%) patients reported the composite outcome, versus 6 out of 33 (18.2%) patients in the standard prophylactic dose bemiparin group. The RD was 3.7% in favor of the standard prophylactic dose bemiparin group (95%CI -15.8% to 23.1%). |

|

Lopes (2021) ACTION trial |

A composite outcome of time to death, duration of hospitalisation, or duration of supplemental oxygen use |

The win ratio for the stable patients stratum was 0.84 (95%CI 0.57 to 1.21), indicating a worse outcome in the therapeutic dose group. |

Results

1. Mortality

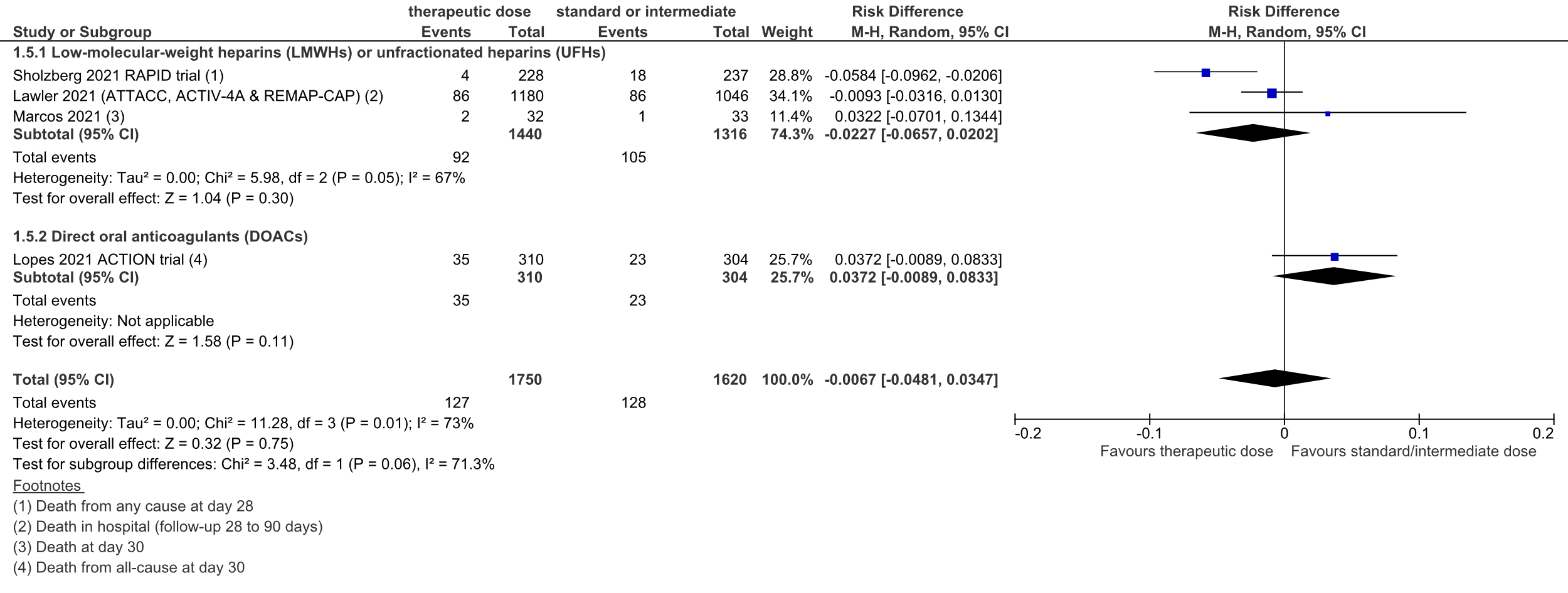

Figure 1: Mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19, divided in subgroups

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Therapeutic dose LMWHs/UFHs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose anticoagulation LMWHs/UFHs

A total of 92 out of 1440 (6.4%) patients died in the therapeutic dose group, versus 105 out of 1316 (8.0%) in the standard prophylactic/intermediate dose group. The pooled risk difference (RD) was 2.3% in favor of the therapeutic dose group (95%CI -6.6% to 2.0%; figure 1). The corresponding NNT was 44. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality was downgraded from high to low because of heterogeneity in the effect size (inconsistency, -1), and the confidence interval of the pooled RD crossing the lower threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1).

Therapeutic dose DOACs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose LMWHs/UFHs

A total of 35 out of 310 (11%) patients died in the therapeutic dose group, versus 23 out of 304 (8%) in the standard prophylactic/intermediate dose group. The pooled RD was 3.7% in favor of the standard prophylactic/intermediate dose group (95%CI -0.9% to 8.3%; figure 1). The corresponding NNT was 27. This was considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality was downgraded from high to low because of the inclusion of a small number of patients admitted to the ICU (indirectness, -1), the inclusion of a single study and the confidence interval of the pooled RD crossing the upper threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1).

Total group

Overall, 127 out of 1750 (7.3%) patients died in the therapeutic dose group, versus 128 out of 1620 (7.9%) in the standard prophylactic/intermediate dose group. The pooled RD was 0.7% in favor of the therapeutic dose group (95%CI -4.8% to 3.5%; figure 1). The corresponding NNT was 149. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality was downgraded from high to very low because of heterogeneity in effect size (inconsistency, -1), and the confidence interval of the pooled RD crossing both thresholds (upper and lower) for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2).

2. Length of hospital stay

Therapeutic dose LMWHs/UFHs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose anticoagulation LMWHs/UFHs

None of the studies reported length of hospital stay in both study groups.

However, Lawler (2021) did report the length of hospital stay for the total group of patients. The median hospital length of stay for all patients was 5 days (interquartile range 3-10). Lawler (2021) also reported an adjusted (age, sex, site, D-dimer group, and time epoch) hazard ratio of the time-to-event endpoint length of hospital stay truncated at 28 days of 1.03 (95%CI 0.95 to 1.13) in favor of the group treated with a therapeutic dose anticoagulation.

Sholzberg (2021) reported the number of hospital-free days alive. The mean number of hospital-free days alive was 19.8 days (SD 7.3) in the therapeutic dose group versus 18.4 (SD 9.2) in the standard prophylactic dose group. The mean difference was 1.40 days (95%CI -0.11 to 2.91).

Marcos (2021) reported hospital discharge in the first 10 days. In the therapeutic dose group, 21 out of 32 patients (65.6%) were discharged, versus 26 out of 33 patients (78.8%) in the standard prophylactic dose group.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence could not be determined, as none of the studies reported on length of hospital stay.

Therapeutic dose DOACs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose LMWHs/UFHs

Lopes (2021) reported length of hospital stay at the end of 30 days. The mean length of stay was 8.1 days (SD 7.2) for the therapeutic dose group, versus 7.8 days (SD 7.5) for the standard prophylactic dose group. The mean difference was 0.3 days (95%CI -0.86 to 1.46). This difference was not considered to be clinically relevant.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure length of hospital stay was downgraded from high to moderate because of the low number of patients (imprecision, -1).

3. ICU-admission (yes/no)

Therapeutic dose LMWHs/UFHs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose anticoagulation LMWHs/UFHs

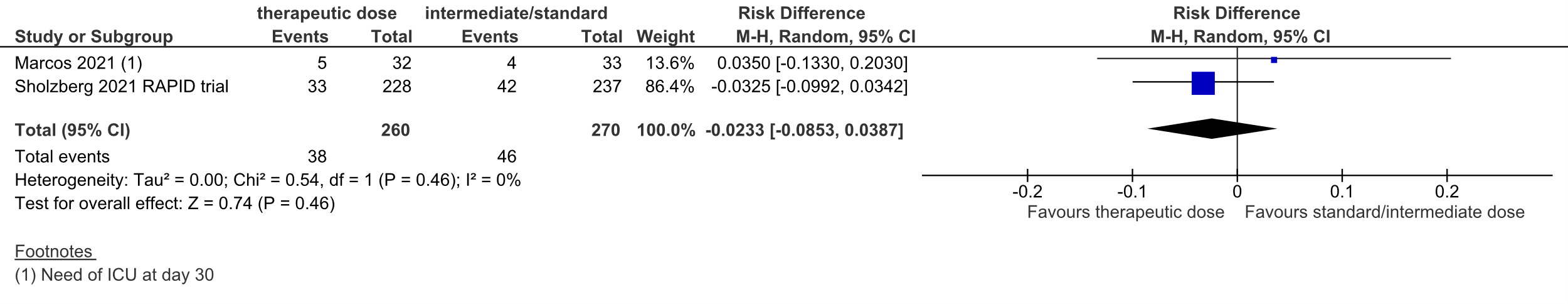

Figure 2: ICU-admission in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, divided in subgroups.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Sholzberg (2021) reported ICU-admission. 33 out of 228 (14.5%) patients in the therapeutic dose group were admitted to the ICU, versus 42 out of 237 (17.7%) in the standard prophylactic dose group.

Marcos (2021) reported the need of ICU at day 10 and day 30. At day 10, 4 out of 32 patients (12.5%) needed ICU in the therapeutic dose group, versus 4 out of 33 patients (12.1%) in the standard prophylactic dose group. At day 30, 5 out of 32 patients (15.6%) needed ICU in the therapeutic dose group, versus 4 out of 33 patients (12.1%) in the standard prophylactic dose group.

Taken together, the pooled RD was 2.3% in favor of the therapeutic dose group (95%CI

-8.5% to 3.9%, figure 2). The corresponding NNT was 43. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Lawler (2021) did not report ICU-admission.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ICU-admission was downgraded from high to low because of the low number of events and the confidence interval around the pooled RD crossing the lower threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2).

Therapeutic dose DOACs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose LMWHs/UFHs

Lopes (2021) did not report information on ICU-admission.

4. Organ support

Organ support free days

Therapeutic dose LMWHs/UFHs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose anticoagulation LMWHs/UFHs

Sholzberg (2021) reported organ support free days alive. In the therapeutic dose group, patients had a mean of 25.8 (SD 6.2) organ support free days alive versus 24.1 (SD 8.8) days in the standard prophylactic dose group. The mean difference was 1.70 (95%CI 0.32 to 3.08) in favor of the therapeutic heparin group. This difference was not considered to be clinically relevant.

Lawler (2021) reported the organ support free days as evaluated on an ordinal scale that combined in-hospital death and the number of days free of cardiovascular or respiratory organ support up to day 21 among patients who survived to hospital discharge. Because the majority of patients in the two treatment groups survived until hospital discharge without receipt of critical care–level organ support, the median value for organ support–free days was 22 in both groups. Out of 1048 patients in the standard prophylactic dose group, 801 (76.4%) survived until hospital discharge without organ support during the first 21 days, as compared to 939 of 1171 patients (80.2%) in the therapeutic dose group. The RD was 3.8% in favor of the therapeutic dose group (95%CI 0.3% to 7.2%). However, no conclusions can be drawn based on this data.

Marcos (2021) did not report organ support free days as a separate outcome that matched how the working group defined it a priori, but solely as part of the primary composite outcome.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure organ support free days (based on data from Sholzberg (2021)) was downgraded from high to moderate because of the confidence interval around the mean difference crossing the upper threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1).

Therapeutic dose DOACs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose LMWHs/UFHs

Lopes (2021) did not report organ support free days.

Organ support (intubation or mechanical ventilation)

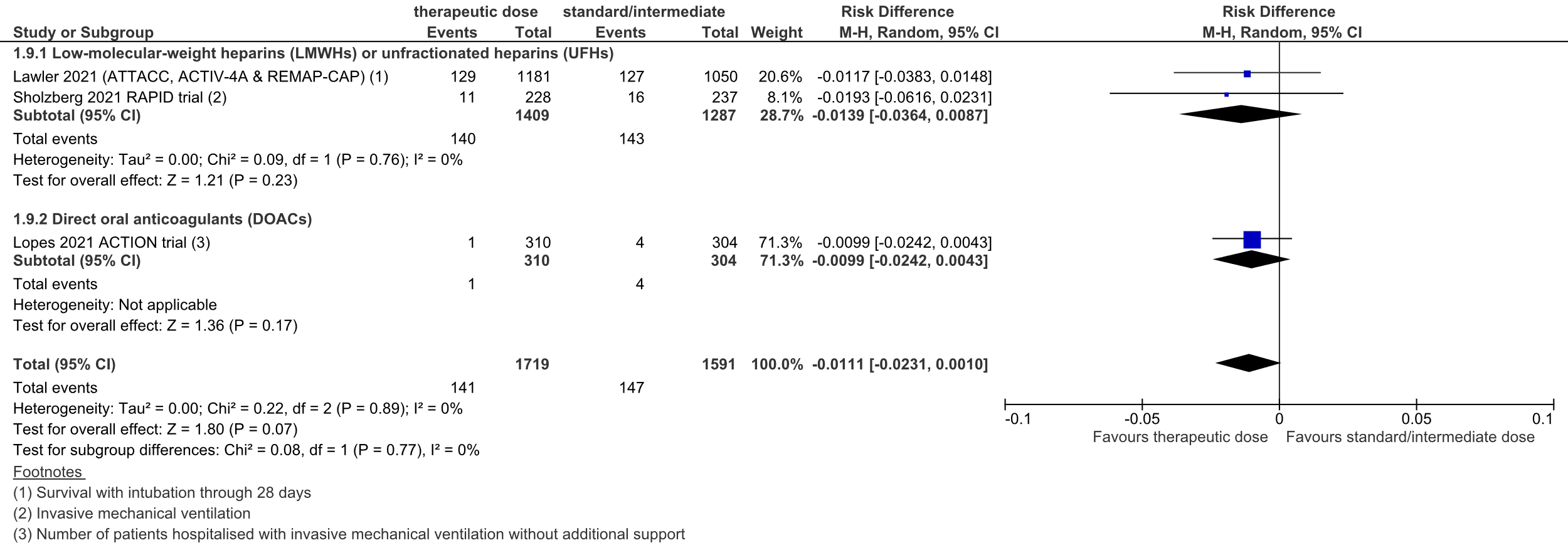

Figure 3: intubation or mechanical ventilation in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, divided in subgroups.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Therapeutic dose LMWHs/UFHs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose anticoagulation LMWHs/UFHs

Lawler (2021) originally reported survival without intubation through 28 days. This was recalculated to survival with intubation through 28 days.

A total of 140 out of 1409 (9.9%) patients received intubation or invasive mechanical ventilation in the therapeutic dose group, versus 143 out of 1287 (11.1%) in the standard prophylactic/intermediate dose group. The pooled risk difference (RD) was 1.4% in favor of the therapeutic dose group (95%CI -3.6% to 0.9%; figure 3). The corresponding NNT was 72. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure organ support (intubation or mechanical ventilation) was downgraded from high to moderate, because of the small number of events (imprecision, -1).

Therapeutic dose DOACs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose LMWHs/UFHs

A total of 1 out of 310 (0.3%) patients received invasive mechanical ventilation without additional support in the therapeutic dose group, versus 4 out of 304 (1.3%) in the standard prophylactic/intermediate dose group. The pooled risk difference (RD) was 1.0% in favor of the therapeutic dose group (95%CI -2.4% to 0.4%; figure 3). The corresponding NNT was 101. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure organ support (intubation or mechanical ventilation) was downgraded from high to moderate, because of the small number of events (imprecision, -1).

Total group

A total of 141 out of 1719 (8.2%) patients received intubation or invasive mechanical ventilation in the therapeutic dose group, versus 147 out of 1591 (9.2%) in the standard prophylactic/intermediate dose group. The pooled risk difference (RD) was 1.1% in favor of the therapeutic dose group (95%CI -2.3% to 0.1%; figure 3). The corresponding NNT was 90. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure organ support (intubation or mechanical ventilation) was downgraded from high to moderate, because of the small number of events (imprecision, -1).

5. Venous thromboembolism

Therapeutic dose LMWHs/UFHs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose anticoagulation LMWHs/UFHs

Sholzberg (2021) reported the number of patients with venous thromboembolism (consisting of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism). In the therapeutic dose group, 2 out of 228 patients (0.9%) developed venous thromboembolism, versus 6 out of 237 (2.5%) in the standard prophylactic dose group. The RD was 1.7% in favor of the therapeutic dose group (95%CI -4.0% to 0.7%). The corresponding NNT was 61. This difference was not considered to be clinically relevant.

Lawler (2021) and Marcos (2021) did not report the number of patients with venous thromboembolism.

However, Lawler (2021) did report the number of events for deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism separately. In the therapeutic dose group 6 events for deep venous thrombosis were reported, versus 7 events in the standard prophylactic dose group. For pulmonary embolism, 10 events were reported in the therapeutic dose group, versus 19 events in the standard prophylactic dose group.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence (based on data from Sholzberg (2021)) regarding the outcome measure venous thromboembolism was downgraded from high to very low because of the open-label study design (risk of bias, -1), the inclusion of one study with a small number of events (imprecision, -2).

Therapeutic dose DOACs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose LMWHs/UFHs

Lopes (2021) reported the number of patients with venous thromboembolism (consisting of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism). 11 out of 310 (3.6%) patients in the therapeutic dose group versus 18 out of 304 (5.9%) patients in the standard prophylactic dose group developed venous thromboembolism. The RD was 2.4% in favor of the therapeutic dose group (95%CI -5.7% to 1.0%). The corresponding NNT was 42. This difference was not considered to be clinically relevant.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure venous thromboembolism was downgraded from high to very low because of the open-label study design (risk of bias, -1), the inclusion of patients admitted to the ICU (indirectness, -1), the inclusion of only one study with a limited number of events and the confidence interval around the RD crossing the lower threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1).

Thromboembolic complications (VTE/ATE)

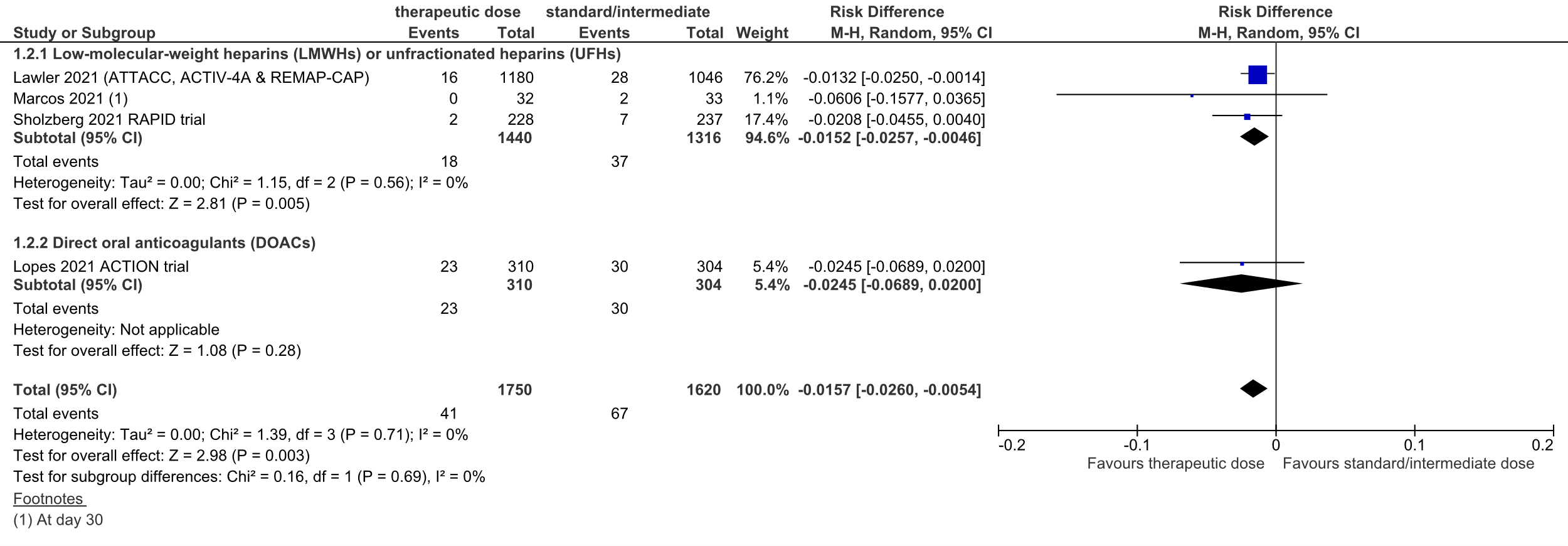

Figure 4: thromboembolic complications in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, divided in subgroups.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Therapeutic dose LMWHs/UFHs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose anticoagulation LMWHs/UFHs

Lawler (2021) reported the number of patients with an in-hospital thrombotic event (defined as pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, ischemic cerebrovascular event, systemic arterial thromboembolism, and deep venous thrombosis): 16 out of 1180 (1.5%) patients experienced an in-hospital thrombotic event in the therapeutic dose group, versus 28 out of 1046 (2.7%) in the standard prophylactic dose group.

Sholzberg (2021) reported venous and arterial thromboembolism separately. When combined, 2 out of 228 (0.9%) patients developed VTE/ATE in the therapeutic dose heparin group, versus 7 out of 237 (3.0%) patients in the standard prophylactic dose heparin group.

Marcos (2021) reported arterial and venous thromboembolism (ATE/VTE) combined in one outcome measure at day 10 and day 30. At day 10, none of the patients in the intervention group developed ATE/VTE, versus 1 out of 33 patients (3.0%) in the control group. At day 30, none of the patients in the intervention group had developed ATE/VTE, versus 2 out of 33 patients (6.1%) in the control group.

Overall, the pooled RD was 1.5% in favor of the therapeutic dose heparin group (95%CI -2.6% to 0.5%, figure 4). The NNT was 66. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure thromboembolic complications was downgraded from high to low because of the open-label study designs (risk of bias, -1), and the small number of events (imprecision, -1).

Therapeutic dose DOACs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose LMWHs/UFHs

Lopes (2021) also reported the number of patients with the composite thrombotic outcome (consisting of venous thromboembolism – deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and major adverse limb event). 23 out of 310 (7.4%) patients in the therapeutic dose group versus 30 out of 304 (9.9%) patients in the standard prophylactic dose group reported the composite thrombotic outcome. The RD was 2.5% in favor of the therapeutic dose DOAC group (95%CI -6.9% to 2.0%, figure 4). The NNT was 41. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure thromboembolic complications was downgraded from high to very low because of the open-label study design (risk of bias, -1), the inclusion of patients admitted to the ICU (indirectness, -1), and the confidence interval around the RD crossing the lower threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1).

Total group

In total, 41 out of 1750 (2.3%%) patients in the therapeutic dose group developed thromboembolic complications, versus 67 out of 1620 (4.1%) patients in the standard prophylactic/intermediate dose group. The pooled RD was 1.6% in favor of the therapeutic dose group (95%CI -2.6% to -0.5%; figure 4). The corresponding NNT was 64. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure thromboembolic complications was downgraded from high to low because of the open-label study designs (risk of bias, -1), and the low number of events (imprecision, -1).

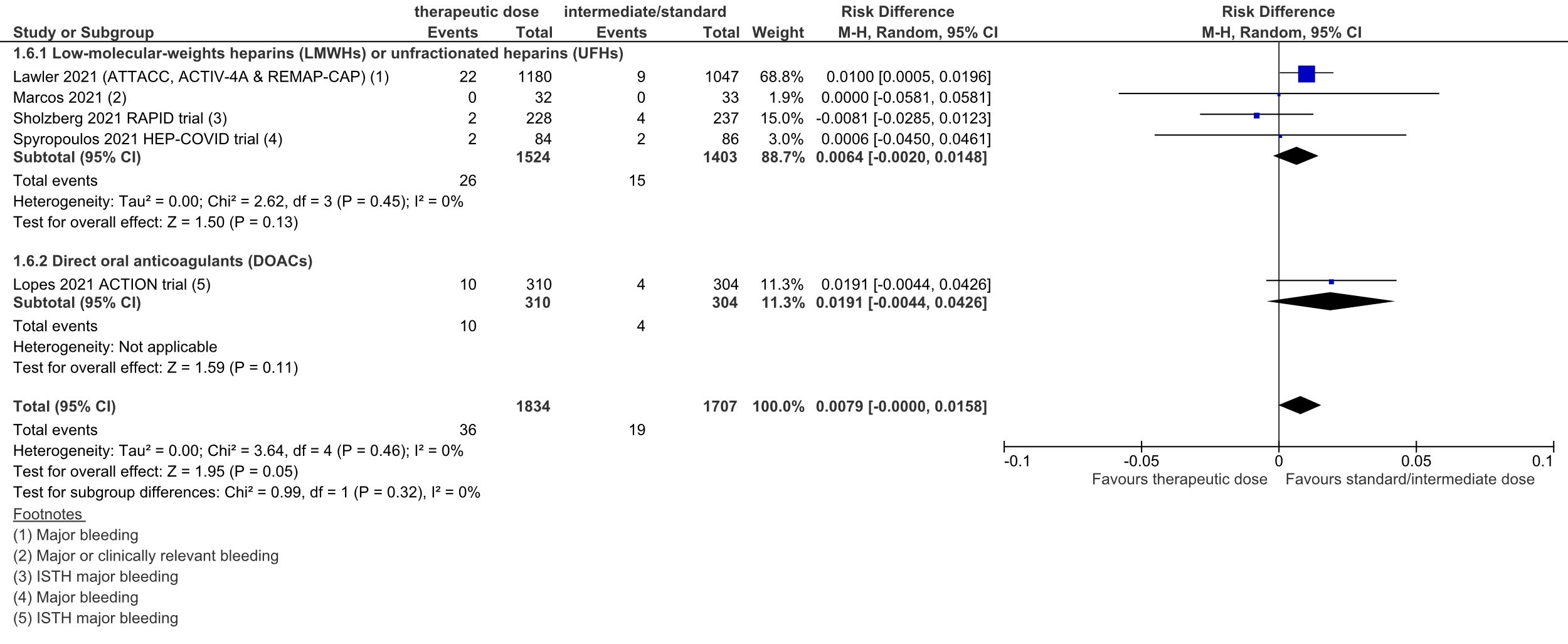

6. Major bleeding

Figure 5: Major bleeding in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, divided in subgroups.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Therapeutic dose LMWHs/UFHs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose anticoagulation LMWHs/UFHs

In total, 26 out of 1524 (1.7%) patients in the therapeutic dose group developed major bleeding, versus 15 out of 1403 (1.1%) patients in the standard prophylactic/intermediate dose group. The pooled RD was 0.6% in favor of the standard prophylactic/intermediate dose group (95%CI -0.2% to 1.5%; figure 5). The corresponding NNH was 156. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure major bleeding was downgraded from high to low because of the open-label study designs (risk of bias, -1), and the low number of cases (imprecision, -1).

Therapeutic dose DOACs vs intermediate/standard prophylactic dose LMWHs/UFHs

In total, 10 out of 310 (3%) patients in the therapeutic dose group developed major bleeding, versus 4 out of 304 (1%) patients in the standard prophylactic/intermediate dose group. The RD was 1.9% in favor of the standard prophylactic/intermediate dose group (95%CI -0.4% to 4.3%, figure 5). The corresponding NNH was 52. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure major bleeding was downgraded from high to very low because of the open-label study design (risk of bias, -1), heterogeneity in the study population (indirectness, -1), inclusion of one study with a low number of cases (imprecision, -1).

Total group

In total, 36 out of 1834 (2.0%) patients in the therapeutic dose group developed major bleeding, versus 19 out of 1707 (1.1%) patients in the standard prophylactic/intermediate dose group. The pooled RD was 0.8% in favor of the standard prophylactic/intermediate dose group (95%CI 0.0% to 1.6%; figure 5). The corresponding NNH was 127. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure major bleeding was downgraded from high to low because of the open-label study designs (risk of bias, -1), and the low number of events (imprecision, -1).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the efficacy and safety of anticoagulation therapy in COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital (not ICU)?

PICO 1

P: all adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital (not ICU) who are not already on chronic therapeutic anticoagulants

I: therapeutic dose (low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, vitamin K-antagonists, aspirin)

C: standard prophylactic dose or intermediate dose (low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, vitamin K-antagonists, aspirin) or no use of standard prophylactic dose or intermediate dose (low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, vitamin K-antagonists, aspirin)

O: mortality, major bleeding, venous thromboembolism, thromboembolic complications (venous and arterial thrombotic complications combined), length of hospital stay, ICU-admission (yes/no) and organ support free days

PICO 2

P: all adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital (not ICU) who are not already on chronic therapeutic anticoagulants

I: intermediate dose (low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, vitamin K-antagonists, aspirin)

C: standard prophylactic dose (low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, vitamin K-antagonists, aspirin) or no use of standard prophylactic dose (low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, vitamin K-antagonists, aspirin)

O: mortality, major bleeding, venous thromboembolism, thromboembolic complications (venous and arterial thrombotic complications combined), length of hospital stay, ICU-admission (yes/no) and organ support free days

When possible subgroup analyses were performed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the different types of anticoagulant.

We searched for standard dose of prophylaxis and intermediate dose of prophylaxis; the latter is typically a doubling of the standard dose of prophylaxis.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered mortality, venous thromboembolism, thromboembolic complications (venous and arterial thrombotic complications combined) and major bleeding as critical outcome measures for decision making; and length of hospital stay, ICU-admission (yes/no), and organ support as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define organ support but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined a risk difference of 3% as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for mortality, venous thromboembolism, thromboembolic complications (venous and arterial thrombotic complications combined) and major bleeding; 3 days for length of hospital stay and organ support free days; and a risk difference of 5% for ICU-admission (yes/no) and a risk difference of 5% for organ support (yes/no).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until October 18th 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 686 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- randomized controlled trial (RCT)

- peer reviewed and published in indexed journal or pre-published

- comparing treatment with

- a therapeutic dose of anticoagulant (low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, vitamin K-antagonists, aspirin) with a standard prophylactic dose, intermediate dose, or no dose of anticoagulant (low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, vitamin K-antagonists, aspirin)

- an intermediate dose of anticoagulant (low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, vitamin K-antagonists, aspirin) with a standard prophylactic dose or no dose of anticoagulant (low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, vitamin K-antagonists, aspirin)

- in non-critically ill patients with COVID-19

- <10% of patients admitted to the ICU.

Fourteen studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, nine studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and five studies were included.

Results

Five studies were included in the analysis of the literature. All studies investigated a therapeutic dose anticoagulant versus standard prophylactic or intermediate dose anticoagulant in COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital (PICO 1). No studies were found that investigated intermediate dose anticoagulant versus standard prophylactic dose anticoagulant in COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital (PICO 2). One of the studies included a small number of patients admitted to the ICU. Subgroups were made based on the type of anticoagulant used: low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWHs) and unfractionated heparins (UFHs), or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Jiménez D, García-Sanchez A, Rali P, Muriel A, Bikdeli B, Ruiz-Artacho P, Le Mao R, Rodríguez C, Hunt BJ, Monreal M. Incidence of VTE and Bleeding Among Hospitalized Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Chest. 2021 Mar;159(3):1182-1196. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.11.005. Epub 2020 Nov 17. PMID: 33217420; PMCID: PMC7670889.

- Lawler, P.R., et al., The REMAP-CAP, ACTIV-4a, and ATTACC Investigators (2021) Therapeutic Anticoagulation with Heparin in Noncritically Ill Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105911.

- Lopes RD, de Barros E Silva PGM, Furtado RHM, Macedo AVS, Bronhara B, Damiani LP, Barbosa LM, de Aveiro Morata J, Ramacciotti E, de Aquino Martins P, de Oliveira AL, Nunes VS, Ritt LEF, Rocha AT, Tramujas L, Santos SV, Diaz DRA, Viana LS, Melro LMG, de Alcântara Chaud MS, Figueiredo EL, Neuenschwander FC, Dracoulakis MDA, Lima RGSD, de Souza Dantas VC, Fernandes ACS, Gebara OCE, Hernandes ME, Queiroz DAR, Veiga VC, Canesin MF, de Faria LM, Feitosa-Filho GS, Gazzana MB, Liporace IL, de Oliveira Twardowsky A, Maia LN, Machado FR, de Matos Soeiro A, Conceição-Souza GE, Armaganijan L, Guimarães PO, Rosa RG, Azevedo LCP, Alexander JH, Avezum A, Cavalcanti AB, Berwanger O; ACTION Coalition COVID-19 Brazil IV Investigators. Therapeutic versus prophylactic anticoagulation for patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 and elevated D-dimer concentration (ACTION): an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2021 Jun 12;397(10291):2253-2263. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01203-4. Epub 2021 Jun 4. PMID: 34097856; PMCID: PMC8177770.

- Marcos M, Carmona-Torre F, Vidal Laso R, Ruiz-Artacho P, Filella D, Carbonell C, Jimenez-Yuste V, Schwartz J, Llamas P, Alegre F, Sádaba B, Núñez-Córdoba J, Yuste JR, Fernández-García J, Lecumberri R. Therapeutic vs. prophylactic bemiparin in hospitalized patients with non-severe COVID-19 (BEMICOP): an open-label, multicenter, randomized trial. Thromb Haemost. 2021 Oct 12. doi: 10.1055/a-1667-7534. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34638151.

- Nopp S, Moik F, Jilma B, Pabinger I, Ay C. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020 Sep 25;4(7):1178–91. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12439. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33043231; PMCID: PMC7537137.

- Sholzberg M, Tang GH, Rahhal H, AlHamzah M, Kreuziger LB, Ní Áinle F, Alomran F, Alayed K, Alsheef M, AlSumait F, Pompilio CE, Sperlich C, Tangri S, Tang T, Jaksa P, Suryanarayan D, Almarshoodi M, Castellucci L, James PD, Lillicrap D, Carrier M, Beckett A, Colovos C, Jayakar J, Arsenault MP, Wu C, Doyon K, Andreou ER, Dounaevskaia V, Tseng EK, Lim G, Fralick M, Middeldorp S, Lee AYY, Zuo F, da Costa BR, Thorpe KE, Negri EM, Cushman M, Jüni P; RAPID Trial investigators. Heparin for Moderately Ill Patients with Covid-19. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2021 Jul 12:2021.07.08.21259351. doi: 10.1101/2021.07.08.21259351. Update in: BMJ. 2021 Oct 14;375:n2400. PMID: 34268513; PMCID: PMC8282099.

- Spyropoulos AC, Goldin M, Giannis D, Diab W, Wang J, Khanijo S, Mignatti A, Gianos E, Cohen M, Sharifova G, Lund JM, Tafur A, Lewis PA, Cohoon KP, Rahman H, Sison CP, Lesser ML, Ochani K, Agrawal N, Hsia J, Anderson VE, Bonaca M, Halperin JL, Weitz JI; HEP-COVID Investigators. Efficacy and Safety of Therapeutic-Dose Heparin vs Standard Prophylactic or Intermediate-Dose Heparins for Thromboprophylaxis in High-risk Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19: The HEP-COVID Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2021 Oct 7:e216203. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.6203. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34617959; PMCID: PMC8498934.

- Tan BK, Mainbourg S, Friggeri A, Bertoletti L, Douplat M, Dargaud Y, Grange C, Lobbes H, Provencher S, Lega JC. Arterial and venous thromboembolism in COVID-19: a study-level meta-analysis. Thorax. 2021 Oct;76(10):970-979. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215383. Epub 2021 Feb 23. PMID: 33622981; PMCID: PMC7907632.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size

|

Comments |

|

Lawler, 2021

Integrated REMAPCAP, ATTACC and ACTIV-4a trial.

|

Type of study: open-label, international, adaptive, multiplatform RCT (mpRCR)

Setting and country: 121 sites in 9 countries (the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Brazil, Mexico, Nepal, Australia, the Netherlands, and Spain).

Funding and conflicts of interest: The trial was supported by multiple international funding organizations who had no role in the design, analysis or reporting of the trial result, apart from the ACTIV-4a protocol, which received input on design from professional staff members at the National Institutes of Health and from peer reviewers.

See publication for funding details. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and who were not critically ill* (absence of critical care–level organ support at enrollment).

Exclusion criteria: Patients were ineligible for enrollment if 72 hours had elapsed since hospital admission for Covid-19 or since in-hospital confirmation of the presence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (ATTACC and ACTIV-4a) or if 14 days had elapsed since admission (REMAP-CAP). Patients were also excluded if hospital discharge was expected within 72 hours or if they had a clinical indication for therapeutic anticoagulation, a high risk of bleeding, receipt of dual antiplatelet therapy, or a known heparin allergy, including heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT)

For inclusion criteria per sub trial, see bottom of column with outcomes

N total at baseline: N = 2244 randomized; primary analysis involved 2219 patients. After exclusion: Intervention: 1181 Control: 1050

Important characteristics: Age, mean (SD) I: 59.0 y (14.1) C: 58.8 y (13.9)

Sex, n/N (%) male I: 713/1181 (60.4%) C: 597/1050 (56.9%)

Country, n (%) (i/C) Canada 102 (8.6) / 83 (7.9) Brazil 234 (19.8) / 209 (19.9) Other§§ 177 (15.0) / 148 (14.1)

BMI, median (IQR) I: 29.8 (26.3–34.7) C: 30.3 (26.7–34.9)

Respiratory support, n/N (%) None I: 156 (13.2) C: 123 (11.7) Low-flow nasal cannula or face mask I: 789 (66.8) C: 696 (66.3) High-flow nasal cannula I: 25 (2.1) C: 28 (2.7) Noninvasive mechanical ventilation I: 21 (1.8) C: 24 (2.3) Unspecified**; In REMAP-CAP, levels of oxygen support (including no support) below the level of high-flow nasal cannula were not reported. I: 190 (16.1) C: 179 (17.0)

Preexisting condition — no./total no. (%) Hypertension I: 546/1023 (53.4) C: 447/892 (50.1) Diabetes mellitus I: 352/1181 (29.8) C: 311/1049 (29.6) Severe cardiovascular disease I: 123/1165 (10.6) C: 121/1038 (11.7) Chronic kidney disease I: 83/1173 (7.1) C: 69/1037 (6.7) Chronic respiratory disease I: 249/1132 (22.0) C: 212/988 (21.5) Immunosuppressive disease I: 105/1143 (9.2) C: 103/1005 (10.2)

Treatment — no./total no. (%) Antiplatelet agent I: 148/1140 (13.0) C: 111/1013 (11.0) Remdesivir I: 428/1178 (36.3) C: 383/1048 (36.5) Glucocorticoid I: 479/791 (60.6) C: 415/656 (63.3) Tocilizumab I: 6/1178 (0.5) C: 7/1048 (0.7)

Median laboratory value (IQR) Median d-dimer level relative to ULN at trial site I: 1.6 (0.9–2.6) C: 1.5 (1.0–2.7) Platelets — per mm3 I: 221,000 (171,000–290,000) C: 218,000 (172,500–289,000) Lymphocytes — per mm3 I: 900 (700–1300) C: 1000 (700–1400) Creatinine — mg/dl I: 0.9 (0.7–1.1) C: 0.9 (0.7–1.1)

Groups comparable at baseline. |

Therapeutic-dose anticoagulation with unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin up to 14 days or to hospital discharge. Unfractionated heparine: |

Usual-care pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis up to 14 days or hospital discharge. After this period, decisions regarding thromboprophylaxis are at discretion of treating clinician.

For ACTIV 4a any one of enoxaparin, dalteparin, tinzaparin, fondaparinux, or heparin according to local preference. Dose of agent specified to be consistent with guidelines for low dose thromboprophylaxis. |

Length of follow-up: 28 to 90 days

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 19 (1.6%) Reasons 9 did not have confirmed COVID-19 9 withdrew consent 1 did not have outcome data available

Control: 6 (0.6%) Reasons 1 withdrew consent 2 did not have outcome data available 3 did not have confirmed COVID-19 |

Mortality: Death in hospital I: 86/1180 (7.3%) C: 86/1046 (8.2%)

Length of hospital stay: Hospital length of stay (time-to-event endpoint truncated at 28 days) in the total group of patients Hazard ratio (95% CI) 1.03 (0.94-1.13); the overall median (interquartile range) hospital length of stay following randomization was 5 (3, 10) days.

ICU-admission Nothing reported

Organ support free days Evaluated on an ordinal scale that combined in-hospital death and the number of days free of cardiovascular or respiratory organ support up to day 21 among patients who survived to hospital discharge I: 939/1171 patients (80.2%) C: 801/1048 patients (76.4%) Of the in the usual-care Adjusted odds ratio 1.27 (95% Credible Interval 1.03 to 1.58). Adjusted for age, sex, trial site, d-dimer cohort, and enrollment period

Survival without intubation through 28 days I: 1052/1181 (89.1%) C: 923/1050 (87.9%)

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) Number of patients with VTE not specifically reported.

Pulmonary embolism events I: 10 C: 19

Deep venous thrombosis events I: 6 C: 7

Number of patients with an in-hospital thrombotic event (defined as pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, ischemic cerebrovascular event, systemic arterial thromboembolism, and deep venous thrombosis). I: 16/1180 (1.5%) patients C: 28/1046 (2.7%) patients

Major bleeding I: 22 out of 1180 (1.9%) patients C: 9 out of 1047 (0.86%) patients

------------------------------------

Inclusion criteria per sub trial: REMAP-CAP:

ACTIV-4a:

ATTACC:

|

Definitions: * Moderate disease severity was defined as hospitalization for Covid-19 without the need for ICU-level care. ICU-level care was defined as the use of respiratory or cardiovascular organ support (oxygen delivered by high-flow nasal cannula, non-invasive or invasive mechanical ventilation, or the use of vasopressors or inotropes) in an ICU. [In ACTIV-4a, in which investigators found that ICU-level care was challenging to define during the pandemic, receipt of organ support, regardless of hospital setting, was used to define ICU-level care. Patients who were admitted to an ICU but without receiving qualifying organ support were considered to be moderately ill.]

Definitions of major thrombotic and any thrombotic events are described in the study protocol.

Remarks: The trial was stopped when prespecified criteria for the superiority of therapeutic dose anticoagulation were met.

Authors conclusion: In noncritically ill patients with Covid-19, an initial strategy of therapeutic-dose anticoagulation with heparin increased the probability of survival to hospital discharge with reduced use of cardiovascular or respiratory organ support as compared with usual-care thromboprophylaxis.

|

|

Spyropoulos, 2021

HEP-COVID Randomized Clinical Trial

AND

corresponding Trial protocol design paper (Goldin, 2021) |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial

Setting and country: Multicenter study in the US (12 centers)

Funding and conflicts of interest: Support from Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, the Broxmeyer Fellowship in Clinical Thrombosis, and grant R24AG064191 from the National Institute on Aging. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

normalized ratio greater than 1.5

(CrCl) less than 15mL/min/1.73m2

25 000/μL

(HIT) within 100 days

Patients were stratified into two subgroups: non-intensive care unit patients and intensive care unit patients. ICU status was defined by mechanical ventilation, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation or high-flow nasal cannula, vasopressors, or vital sign monitoring more often than every 4 hours. ICU: 83 patients (32.8%) Non-ICU: 170 patients (67.2%)

N total at baseline: N = 257 participants randomized (130 to the intervention group and 127 to the control group) at baseline.

Important prognostic factors2:

Age, mean (SD): I: 65.8 (13.9) C: 67.7 (14.1)

Sex, No./total No. (%) male I: 68/129 (52.7%) C: 68/124 (54.8%)

BMI, mean (SD) I: 31.2 (9.3) C: 29.8 (13.6)

Race and ethnicity, No. (%) (I/C) Asian 11 (8.5) / 14 (11.3) Black 33 (25.6) / 37 (29.8) White 56 (43.4) / 46 (37.1) Multiracial/unknown 29 (22.5) / 27 (21.8)

ICU, No./total No. (%) I: 45/129 (34.9) C: 38/124 (30.6)

Comorbidities, No./total No. (%) (I/C) Hypertension 81/129 (62.8) / 70/123 (56.9) Heart failure 0 / 2/124 (1.6) Diabetes mellitus 51/128 (39.8) / 43/124 (34.7) Dyslipidemia 48/129 (37.2) / 39/124 (31.5) Coronary artery disease 7/129 (5.4) / 11/124 (8.9) Valvular heart disease 1/129 (0.8) / 3/124 (2.4) History of ischemic stroke 5/129 (3.9) / 3/124 (2.4) History of carotid occlusive disease 0 / 0 Peripheral artery disease 4/129 (3.1) / 1/124 (0.8) Chronic kidney disease 5/129 (3.9) / 4/124 (3.2) Chronic lung disease 9/129 (7.0) / 8/124 (6.5) Chronic liver disease/cirrhosis 2/129 (1.6) / 1/124 (0.8) Pulmonary hypertension 1/127 (0.8) / 2/124 (1.6)

VTE risk factors,, No./total No. (%) (I/C) Personal history of VTE 6/129 (4.7) / 2/124 (1.6) History of cancer 16/129 (12.4) / 10/124 (8.1) Active cancer 1/129 (0.8) / 4/124 (3.2) Autoimmune disease 1/128 (0.8) / 2/124 (1.6) Hormonal therapy/oral contraceptives 1/129 (0.8) / 1/124 (0.8) Known thrombophilia 0 / 0 Recent stroke with paresis 1/129 (0.8) / 1/124 (0.8)

Clinical scores, mean (SD) (I/C) IMPROVEDD VTE risk score 4.33 (1.48) / 4.22 (1.36) Sepsis-induced coagulopathy score 2.35 (0.73) / 2.31 (0.85)

Laboratory parameters, mean (SD) (I/C) White blood cell count, /μL 9600 (5800) / 9800 (8200) Platelets, ×103/μL 287.7 (119.8) / 269.7 (108.2) Serum creatinine, mg/dL 0.94 (0.45) / 1.00 (0.50) Prothrombin time, s 13.5 (1.6) /13.6 (2.6) D-dimer, ng/mL 3837 (6166) / 3183 (5409)

Medications prior to randomization, No./total No. (%)(I/C) Low-molecular-weight heparin 106/128 (82.8) / 97/124 (78.2) Unfractionated heparin 18/127 (14.2) / 23/121 (19.0) Remdesivir 93/129 (72.1) / 85/124 (68.6) Glucocorticoids 111/127 (87.4) / 93/123 (75.6) Antiplatelets 40/129 (31.0) / 24/124 (19.4)

Oxygen therapy, No./total No. (%) (I/C) Nasal cannula 80/129 (62.0) / 83/124 (66.9) Nonrebreather mask 12/129 (9.3) / 11/124 (8.9) Ventilation mask 4/129 (3.1) / 2/124 (1.6) High-flow or noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation 20/129 (15.5) / 19/124 (15.3) Invasive mechanical ventilation 8/129 (6.2) / 5/124 (4.0)

Length of hospital stay, mean (SD), d I: 12.2 (9.3)

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Patients in the therapeutic dose group received enoxaparin at a dose of 1 mg/kg subcutaneously twice daily if CrCl was 30 L/min/1.73m2 or greater or 0.5 mg/kg twice daily if CrCl was 15-29 mL/min/1.73m2. Study drug was administered for the duration of hospitalization, including patient transfers to ICU settings.

Study protocol (Goldin, 2021): Individual dose modification is not permitted unless the CrCl falls below 15 mL/min in the treatment arm (arm 0). In that case, conversion to dose-adjusted intravenous (IV) UFH is acceptable. The investigator is encouraged to convert back to treatment-dose enoxaparin as per protocol once the CrCl returns to values higher than or equal to 15 mL/min.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Patients in the standard-dose group received prophylactic or intermediate-dose heparin regimens per local institutional standard and could include UFH, up to 22500 IU subcutaneously (divided twice or thrice daily); enoxaparin, 30 mg or 40 mg subcutaneously once or twice daily (weight based enoxaparin 0.5mg/kg subcutaneously twice daily was permitted but strongly discouraged); or dalteparin, 2500 IU or 5000 IU subcutaneously daily. If CrCl fell below15 mL/min/ 1.73 m2, enoxaparin was converted to treatment-dose intravenous UFH until kidney function improved to CrCl greater than 15 mL/min/1.73 m2, when blinded-dose subcutaneous enoxaparin was resumed. Study drug was administered for the duration of hospitalization, including patient transfers to ICU settings. In the standard dose group, 76 patients (61.3%) received prophylactic doses of heparin (enoxaparin, ≤40mg daily), while 48 patients (38.7%) received intermediate doses of heparin (enoxaparin, 30 mg twice daily, 3 patients [2.4%]; enoxaparin, 40mg twice daily, 43 patients [34.7%]; enoxaparin, 0.5mg/kg twice daily, 2 patients [1.6%]).

Goldin, 2021: Dose modification is allowed in the prophylactic/intermediate group (arm 1) if the CrCl falls below15 mL/min so that UFH up to 22,500 U daily (i.e., UFH 5,000 U SQ BID or TID or 7,500 IU SQ BID or TID) can be used. The investigator is encouraged to convert back to prophylactic-/intermediate dose LMWH/UFH as per protocol once the CrCl returns to values higher than or equal to 15 mL/min. |

Length of follow-up: Until 30 + 2 days after randomization.

Loss-to-follow-up: 4 patients did not receive study drug (2 withdrew consent and 2 reached end points prior to the first dose). That resulted in 253 patients in the modified intention-to-treat population for analysis: Intervention: 129 Control: 124

The primary analysis was based on the modified intention to-treat population, followed by the per-protocol population.

|

Clinical Outcomes During the 30-Day, stratified for ICU and non-ICU:

Mortality Not reported

Length of hospital stay Not reported

ICU-admission Not reported

Organ support free days Not reported

Venous thromboembolism Not reported

Major bleeding I: 2/84 (2.4) C: 2/86 (2.3) RR (95% CI): 1.02 (0.15-7.10)

ICU patients: I: 4/45 (8.9) C: 0 RR (95% CI): 7.62 (0.42-137.03)

|

Author’s conclusions: Therapeutic dose LMWH reduced the composite of thromboembolism and death compared with standard heparin thromboprophylaxis without increased major bleeding among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 with very elevated D-dimer levels. The treatment effect was not seen in ICU patients. |

|

Sholzberg, 2021

RAPID trial |

Type of study: Randomized controlled, adaptive, open label clinical trial.

Setting and country: 28 hospitals in Brazil, Canada, Ireland, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and US.

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funding limitations and covid-19 restrictions interfered with our ability to involve patient partners in setting the research question and in developing plans for recruitment, design, and implementation of the results of this study. |

Inclusion criteria: Moderately ill* patients admitted to hospital wards for covid-19. 1) Laboratory confirmed COVID-19 (diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 via reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction as per the World Health Organization protocol or by nucleic acid based isothermal amplification) prior to hospital admission OR within first 5 days (i.e. 120 hours) after hospital admission; 2) Admitted to hospital for COVID-19; 3) One D-dimer value above the upper limit of normal (ULN) (within 5 days (i.e. 120 hours) of hospital admission) AND EITHER: a. D-Dimer ≥2 times ULN OR b. D-Dimer above ULN and Oxygen saturation ≤ 93% on room air; 4) > 18 years of age; 5) Informed consent from the patient (or legally authorized substitute decision maker).