Vitamine C

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van vitamine C bij de behandeling van patiënten met COVID-19?

Aanbeveling

Gebruik vitamine C niet als behandeling van COVID-19

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de verschillen in klinische uitkomsten tussen behandeling met en zonder vitamine C. Tot en met 6 januari 2022 werden er 4 gerandomiseerde gecontroleerde studies (RCT’s) gevonden in patiënten die waren opgenomen in het ziekenhuis (n=163 in de interventiegroep en n=203 in de controlegroep) en 1 RCT bij patiënten buiten het ziekenhuis.

De geïncludeerde studies onderzochten verschillende doseringen vitamine C, variërend van cumulatief 7 gram tot 168 gram in de eerste twee weken van de randomisatie. Ook werden verschillende toedieningsvormen gebruikt: intraveneus (JamaliMoghadamSiahkali, 2021; Kumari, 2020; Zhang, 2021) en oraal (Majidi, 2021; Thomas, 2021).

Er werden alleen randomiseerde trials geïncludeerd in de analyse, waardoor de kwaliteit van bewijs initieel hoog was. Omdat de studies steeds een relatief kleine populatie includeerden en omdat er mede hierdoor een grote spreiding van het betrouwbaarheidsinterval rondom de puntschatter van de uitkomstmaat was (imprecision), werd de kwaliteit van dit bewijs naar beneden bijgesteld. Daarnaast waren er drie open-label trials (JamaliMoghadamSiahkali, 2021; Kumari, 2020; Thomas, 2021), met een mogelijk risico op vertekening van de studieresultaten (risk of bias) bij subjectieve uitkomstmaten. Ook om deze reden werd de kwaliteit van dit bewijs waar nodig naar beneden bijgesteld.

Vitamine C bij patiënten die waren opgenomen in het ziekenhuis

Op basis van de vier geïncludeerde studies (JamaliMoghadamSiahkali, 2021; Kumari, 2020; Majidi, 2021 en Zhang, 2021) zijn we onzeker over het effect van behandeling met vitamine C op de cruciale uitkomstmaten mortaliteit en respiratoire ondersteuning. De studies zijn klein, met minder dan 100 patiënten per studie arm. De bewijskracht van de gevonden resultaten wordt daarnaast beperkt door tekortkomingen in de studieopzet. De bewijskracht is, bij beoordeling volgens de GRADE methodiek, ‘zeer laag’. Er is dus sprake van een kennislacune.

Vitamine C bij ambulante patiënten

Op basis van één geïncludeerde studie (Thomas, 2021) zijn we onzeker over het effect van behandeling met vitamine C op de cruciale uitkomstmaat mortaliteit bij ambulante patiënten met COVID-19. Ook in deze groep patiënten is de bewijskracht volgens de GRADE ‘zeer laag’.

Ook de twee studies die initieel werden geëxcludeerd omdat ze een combinatie van vitamines gebruikten (Darban, 2021; Hakamifard, 2021) lieten in hun kleine populaties geen potentieel effect van vitamine C zien.

Overige overwegingen

Vier van de geïncludeerde studies rapporteerden ook ‘adverse events’. Vanwege de kleine aantallen patiënten en de wisselende rapportage van eventuele bijwerkingen zijn er grote verschillen per studie te zien. In de studie van JamaliMoghadamSiahkali (2021) werden geen ‘adverse events’ gezien, terwijl in de studie van Thomas (2021) 17/43 (39.5%) van de patiënten in de interventiegroep een bijwerking ervaarde in de 7 dagen na de toediening van vitamine C ten opzichte van nul in de controlegroep. De volgende ‘adverse events’ werden gerapporteerd: hoofdpijn (n=1), misselijkheid (n=6), overgeven (n=1), tintelingen (n=1), pijn in epigastrio (n=5), diarree (n=7), duizeligheid/moeheid (n=1) en overig (n=1).

In bovenstaande studies leek het gebruik van vitamine C relatief veilig. Een RCT uit 2022 die vitamine C onderzocht bij meer dan 800 patiënten die met een sepsis op de intensive care lagen, toonde echter dat er mogelijk toch een nadeel was van vitamine C (Lamontagne, 2022). In deze studie werd een significant hogere mortaliteit of orgaan dysfunctie gezien bij patiënten die behandeld werden met vitamine C. In de subgroep van patiënten met sepsis door COVID-19 werd dit verschil niet gezien.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Op grond van de bekende onderzoeksgegevens wordt vitamine C niet aanbevolen als behandeling van COVID-19. Daarnaast laat een RCT bij patiënten met een sepsis zien dat behandeling met vitamine C mogelijk ernstige bijwerkingen kan hebben. Dit is niet op grote schaal onderzocht voor COVID-19. Ondanks het advies om vitamine C niet te gebruiken als behandeling van COVID-19, verwachten wij dat patiënten bij hun waardering van vitamine C ook hun persoonlijke voorkeur en maatschappelijke beeldvorming zullen laten meewegen.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Gezien het gebrek aan effectiviteit wordt vitamine C niet aanbevolen als behandeling van COVID-19.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Vitamine C wordt niet aanbevolen als behandeling van COVID-19, dus de werkgroep voorziet geen problemen qua implementatie.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Op dit moment is er onvoldoende data om het gebruik van vitamine C aan of af te raden in de behandeling van COVID-19. Echter, gebruik van vitamine C zou gepaard kunnen gaan met (ernstige) bijwerkingen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Vitamine C is een antioxidant met anti-inflammatoire eigenschappen. Tijdens oxidatieve stress heeft het lichaam mogelijk meer vitamine C nodig, waardoor suppletie van vitamine C is geëvalueerd bij onder andere ernstige infecties en sepsis. In een onderzoeksmodel met muizen met een sepsis werd een langere overleving en minder inflammatie gezien in de groep dit vitamine C kreeg toegediend (Fisher, 2011). Studies bij mensen met een sepsis toonden tegenstrijdige resultaten. Een meta-analyse uit 2020 bij mensen met een sepsis toonde geen verbeterde mortaliteit binnen 28 dagen (Wei, 2020). Ook een gerandomiseerde klinische studie uit 2020 in kritisch zieke patiënten met een septische shock (n=211) toonde geen verschil aan tussen de combinatie van vitamine C (6000 mg/dag), thiamine (400 mg/dag) en hydrocortison (200 mg/dag) versus hydrocortison op de duur van de shock of op mortaliteit. Wel werd een verlaging van SOFA score gezien in de groep met de combinatie (mediane verandering van -2 punten vs -1 punt; P=0.02) (Fujii, 2020). Een studie in kritisch zieke patiënten met sepsis-geïnduceerde ARDS (n=167) toonde wel een lagere mortaliteit op dag 28 in de groep met 200 mg vitamine C/kg per dag (29.8% vs 46.3%; P=0.03). Echter, deze studie toonde geen verschil in SOFA score of inflammatoire markers (Fowler, 2019).

Inmiddels hebben diverse gerandomiseerde gecontroleerde studies (RCT’s) de effectiviteit van vitamine C onderzocht om de plaats van dit middel bij de behandeling van COVID-19 patiënten te bepalen. Klinische dose-finding studies zijn in deze setting nooit verricht.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

PICO 1: Treatment with vitamin C in hospitalized COVID-19 patients

Mortality (crucial)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with vitamin C on mortality when compared to treatment without vitamin C in hospitalized patients with moderate to severe COVID-19.

Sources: JamaliMoghadamSiahkali, 2021; Kumari, 2020 and Zhang, 2021 |

Extensive respiratory support (crucial)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with vitamin C on extensive respiratory support when compared to treatment without vitamin C in hospitalized patients with moderate to severe COVID-19.

Sources: JamaliMoghadamSiahkali, 2021; Kumari, 2020 and Zhang, 2021 |

Duration of hospitalization (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with vitamin C on length of stay when compared to treatment without vitamin C in hospitalized patients with moderate to severe COVID-19.

Sources: JamaliMoghadamSiahkali, 2021; Kumari, 2020 and Zhang, 2021 |

Time to clinical improvement (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with vitamin C on time to clinical improvement when compared to treatment without vitamin C in hospitalized patients with moderate to severe COVID-19.

Source: Kumari, 2020 |

PICO 2: Treatment with vitamin C in non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients

Mortality (crucial)

|

- GRADE |

Due to low number of events, it is not possible to draw a conclusion on the effect of treatment with vitamin C on mortality when compared to treatment without vitamin C in non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Sources: Thomas, 2021 |

Hospitalization (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with vitamin C on hospitalization when compared to treatment without vitamin C in non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Sources: Thomas, 2021 |

Respiratory support (important)

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of treatment with vitamin C on respiratory support when compared to treatment without vitamin C in non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Source: - |

Time to clinical improvement (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with vitamin Con time to clinical improvement when compared to treatment without vitamin C in non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Sources: Thomas, 2021 |

Samenvatting literatuur

PICO 1: Treatment with vitamin C in hospitalized COVID-19 patients

JamaliMoghadamSiahkali (2021) described an open label randomized clinical trial, which was performed in Iran. JamaliMoghadamSiahkali (2021) studied the efficacy and tolerability of vitamin C in adult hospitalized patients with moderate or severe COVID-19 disease. They included patients ≥ 18 years with a positive COVID-19 PCR test or COVID-19 suspicion based on clinical findings or imaging findings of COVID-19 on spiral/high-resolution CT imaging, clinical manifestations of ARDS or myocarditis and oxygen saturation <93% from admission or after 48 hours from the first COVID-19 treatment. Patients in the intervention group (n=30) received 1.5 g vitamin C (IV) every six hours for five days plus standard care. The control group (n=30) received standard care only. Standard care consisted of oral lopinavir (400mg)/ritonavir (100 mg) twice daily and a single dose of oral hydroxychloroquine (400 mg) on the first day of hospitalization. In case of deterioration during admission, patients received methylprednisolone (125 mg daily for three days). In the intervention group 26.6% of the patients received corticosteroids, compared to 23.3% of the patients in the control group. Vitamin C intake and/or levels at baseline were not reported. Patients were followed until discharge. Primary outcome measures included decrease in mortality and duration of hospitalization. In both groups, 3/30 (10%) patients died. In the intervention group, median (IQR) duration of hospitalization was 8.5 (7.0 tot 12.0) days, compared to 6.5 (4.0 to 12.0) days in the control group. Median length of stay at the ICU (IQR) was 5.5 (5.0 to 10.0) days in the intervention group, compared to 5.0 (5.0 to 7.0) days in the control group. Besides, the following relevant outcome measures were reported: respiratory support (intubation).

Kumari (2020) described an open label randomized clinical trial, which was performed in Pakistan. Kumari (2020) studied the efficacy of vitamin C in hospitalized patients with moderate to severe COVID-19. They included patients with severe COVID-19 based on the national health guidelines of Pakistan. Patients in the intervention group (n=75) received 50 mg/kg of vitamin C IV daily, plus standard care. The control group (n=75) received standard care only. Standard care was comparable between both groups and included antipyretics, dexamethasone (not mentioned in how many patients dexamethasone was used), and prophylactic antibiotics. Vitamin C intake and/or levels at baseline were not reported. Length of follow-up was not clear. Primary outcome was not specified. The following relevant outcome measures were reported: mortality, respiratory support (mechanical ventilation), duration of hospitalization and time to clinical improvement.

Majidi (2021) described a double-blinded controlled randomized clinical trial, which was performed in Iran. Majidi (2021) studied the efficacy and tolerability of vitamin C in adult patients with severe COVID-19 disease. They included patients between 35 and 75 years, who were positive for COVID-19, likely to be in the intensive care unit (ICU) for at least 48 hours and have an indication for enteral nutrition. Patients in the intervention group (n=31) received a 500 mg vitamin C capsule per day for 14 days, which was added to their enteral formula. The control group (n=69) received the same enteral nutrition, but without added vitamin C. There is no information available on usual care. Vitamin C intake and/or levels at baseline were not reported. Patients were followed for 14 days after start of the treatment. Survival at the ICU was determined 14 days after completion of the study. According to the study protocol, the primary outcome measures were several inflammatory and biochemical parameters. Results are described in Table 1. Beside the outcome measure survival, there was no other outcome measure of interest to our literature analysis.

Table 1. Primary outcome measures in Majidi (2021).

|

Outcome |

Intervention group (post-intervention)* |

Control group (post-intervention)* |

Mean difference (95%CI) |

|

White blood cells |

11,828 ± 291 |

13,785 ± 378 |

-1957.00 (-2092.82 to -1821.18) |

|

Neutrophils |

8,660 ± 459 |

8,950 ± 238 |

-290.00 (-461.06 to -118.94) |

|

Lymphocytes |

1,175 ± 358 |

925 ± 427 |

250.00 (88.65 to 411.35) |

|

Lactate dehydrogenase |

Not reported |

Not reported |

N.A. |

|

Creatine phosphokinase |

Not reported |

Not reported |

N.A. |

|

Cell blood count |

For details, see Table 2 in Majidi (2021) |

For details, see Table 2 in Majidi (2021) |

|

|

C reactive protein |

Not reported |

Not reported |

N.A. |

|

Partial pressure of oxygen |

67.84 ( ± 23.02) |

72.20 ( ± 8.21) |

-4.36 (-12.69 to 3.97) |

|

Partial pressure of carbon dioxide |

44.35 ( ± 12.48) |

40.70 ( ± 8.90) |

3.65 (-1.22 to 8.52) |

*Mean±SD

Zhang (2021) described a blinded placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial, which was performed in China. Zhang (2021) studied the efficacy and tolerability of vitamin C in adult patients with severe COVID-19 disease, admitted to the ICU. They included patients between 18 and 80 years, who were positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by RT-PCR, had pneumonia confirmed by chest imaging, were admitted to the ICU and had P/F ratio < 300 mmHg. Patients in the intervention group (n=27) received 24 g vitamin C (IV) per day for seven days plus standard care. The control group (n=29) received placebo plus standard care. Standard care could include hydrocortisone 1 mg/kg/day, this was considered in case of rapid deterioration of hypoxemia, severe ARDS or septic shock. The study does not provide details on the number of patients with hydrocortisone. Vitamin C intake and/or levels at baseline were not reported. Patients were followed for 28 days after start of the treatment. The primary outcome measure was median invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV)-free days in 28 days. The intervention group had 26.0 (9.0 to 28.0) IMV-free days, compared to 22.0 (8.5 to 28.0) days in the control group. The Hazard Ratio (HR) (95%CI) was 4.8 (-4.7 to 7.2). The following relevant outcome measures were reported: 28-day mortality, duration of hospitalization, respiratory support (IMV, NIV and HFNC), improvement of the patient’s condition.

Table 2. Overview of RCTs comparing vitamin C with standard care in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

|

Author |

Disease severity* |

Sample size |

Dosage |

|

JamaliMoghadamSiahkali, 2021 |

Moderate to severe |

I: 30 C: 30 Total: 60 |

1.5 g vitamin C intravenous every 6 h for 5 days |

|

Kumari, 2020 |

Moderate to severe |

I: 75 C: 75 Total: 150 |

50 mg/kg vitamin C intravenous every day (number of days unclear) |

|

Majidi, 2021 |

Severe |

I: 31 C: 69 Total: 100 |

500 mg vitamin C per os every day for 14 days |

|

Zhang, 2021 |

Severe |

I: 27 C: 29 Total: 56 |

24 g vitamin C intravenous every day for 7 days

|

*Disease severity categories:

- mild disease (no supplemental oxygen);

- moderate disease (supplemental oxygen: low flow oxygen, non-rebreathing mask);

- severe disease (supplemental oxygen: high flow oxygen [high flow nasal cannula (HFNC)/Optiflow], continuous positive airway pressure [CPAP], non-invasive ventilation [NIV], mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [ECMO or ECLS]).

N: Total sample size

I: Intervention

C: Control

Results

Mortality (crucial)

JamaliMoghadamSiahkali (2021), Kumari (2020) and Zhang (2021) reported on the outcome measure mortality. Zhang (2021) reported on 28-day mortality and JamaliMoghadamSiahkali (2021) on in-hospital mortality. The follow-up period in the study of Kumari (2020) is not clear.

In total, 16/112 (14.3%) patients in the intervention groups died, compared to 24/114 (21.1%) patients in the control group (Figure 1). The risk ratio (RR) (95%CI) was 0.69 (0.39 to 1.22), in favour of the intervention group. The risk difference (RD) (95%CI) was -0.061 (-0.153 to 0.031), in favour of the intervention group. This difference is considered clinically relevant. Since Majidi (2021) only reported on 28-day survival at the ICU and data might be incomplete, it is not possible to incorporate the data of this study in the meta-analysis.

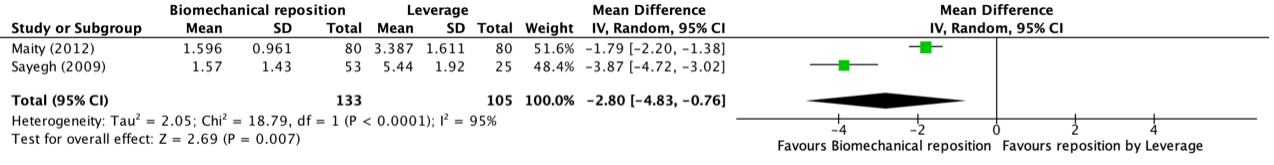

Figure 1: Mortality in hospitalized patients

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Subgroup patients with moderate and severe disease

JamaliMoghadamSiahkali (2021) and Kumari (2020) reported on the outcome measure mortality. JamaliMoghadamSiahkali (2021) reported on in-hospital mortality. In the study of JamaliMoghadamSiahkali 3/30 (10.0%) patients died in both treatment groups. Patients were followed until discharge (no details provided). The follow-up period in the study of Kumari (2020) is not clear. In the intervention group in the study of Kumari (2020) 7/75 (9.3%) patients died, compared to 11/75 (14.7%) patients in the control group. The length of follow-up was not clear. The RR (95%CI) was 0.64 (0.26 to 1.55), in favour of the intervention group. The RD was -0.05 (-0.16 to 0.05), in favour of the intervention group. This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Subgroup patients with severe disease

Majidi (2021) reported on the outcome measure 28-day survival at the ICU. In the intervention group 16.1% patients survived, compared to 2.9% patients in the control group. It is not clear whether data on survival is complete. Therefore, it is not possible to conclude on the effect of treatment with vitamin C on the outcome measure mortality, based on the data of Majidi (2021).

Zhang (2021) reported on the outcome measure mortality after 28 days of follow-up. In the intervention group 6/27 (22.2%) patients died, compared to 10/29 (34.5%) patients in the control group. The HR (95%CI) was 0.5 (0.2 to 1.8), in favour of the intervention group. The RD (95%CI) was -0.12 (-0.36 to 0.11) in favour of the intervention group. This difference is considered clinically relevant (RD>3%).

Level of evidence of the literature

The evidence for the outcome measure mortality comes from RCTs and therefore started at high certainty. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was risk of bias (unclear randomization and/or allocation concealment, baseline differences and unclear follow-up, downgraded one level for risk of bias). Furthermore, the effect estimate (95%CI) crossed the thresholds for clinical relevance (downgraded two levels for imprecision).

Extensive respiratory support (crucial)

JamaliMoghadamSiahkali (2021), Kumari (2020) and Zhang (2021) reported on the outcome measure respiratory support and mechanical ventilation ‘during admission’ (JamaliMoghadamSiahkali, 2021 and Kumari, 2020), while Zhang reported this outcome ‘after 7 days of treatment’ (Zhang, 2021). In total, 27/128 (21.1%) patients in the intervention groups were intubated, compared to 30/128 (23.4%) patients in the control group (Figure 2). The RR (95%CI) was 0.90 (0.58 to 1.39), in favour of the intervention group. The RD (95%CI) was -0.02 (-0.12 to 0.08) in favour of the intervention group. This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 2: Extensive respiratory support in hospitalized patients

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Zhang (2021) also reported on the usage of High Flow Nasal Canula (HFNC), seven days after start of the treatment. They also reported on the number of days with mechanical ventilation (IMV) or HFNC during the 28 days of follow-up. In the intervention group 11/23 (47.8%) patients received HFNC at day seven, compared to 9/23 (39.1%) patients in the control group. The odds ratio (OR) (95%CI) was 1.4 (0.4 to 4.6), in favour of the control group. The RD (95%CI) was 0.09 (-0.20 to 0.37), in favour of the control group. This is considered clinically relevant (RD>5%). The median (IQR) number of days with HFNC was 0.5 (0.0 to 8.3) in the intervention group, compared to 2.0 (0.0 to 7.0) in the control group. The median (IQR) number of days with IMV was 1.5 (0.0 to 19.0) in the intervention group, compared to 6.0 (0.0 to 16.0) in the control group.

Level of evidence of the literature

The evidence for the outcome measure respiratory support comes from RCTs and therefore started at high certainty. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was risk of bias (unclear randomization and/or allocation concealment, baseline differences, no or unclear blinding and risk of selective reporting, downgraded two levels for risk of bias). Furthermore, the effect estimate (95%CI) crossed the thresholds for clinical relevance (downgraded two levels for imprecision).

Duration of hospitalization (important)

JamaliMoghadamSiahkali (2021), Kumari (2020) and Zhang (2021) reported on the outcome measure duration of hospitalization. In the study of JamaliMoghadamSiahkali (2021) the median (IQR) duration of hospitalization was 8.5 (7.0 tot 12.0) days in the intervention group, compared to 6.5 (4.0 to 12.0) days in the control group. This difference in medians is not considered clinically relevant (less than three days).

In the study of Kumari (2020) mean (±SD) duration of hospitalization in the intervention group was 8.1±1.8 days, compared to 10.7±2.2 days in the control group. The mean difference (95%CI) was -2.60 (-3.24 to -1.96) in favour of the intervention group. This is not considered clinically relevant (less than three days).

In the study of Zhang, mean (±SD) duration of hospitalization in the intervention group was 35.0±17.0 days, compared to 32.8±17.0 days in the control group. The mean difference (95%CI) was 2.2 (-7.5 to 11.8) in favour of the control group. This is not considered clinically relevant (less than three days).

JamaliMoghadamSiahkali (2021) and Zhang (2021) also reported on the duration of ICU admission. In the study of JamaliMoghadamSiahkali (2021) median length of stay at the ICU (IQR) was 5.5 (5.0 to 10.0) days in the intervention group, compared to 5.0 (5.0 to 7.0) days in the control group. This difference in medians is not clinically relevant (<three days). In the study of Zhang (2021) mean (±SD) length of stay at the ICU was 22.9±14.8 days in the intervention group, compared to 17.8±13.3 days in the control group. The mean difference (95%CI) was 5.0 (-2.5 to 12.7), in favour of the control group. This difference is considered clinically relevant (more than three days).

Level of evidence of the literature

The evidence for the outcome measure duration of hospitalization comes from RCTs and therefore started at high certainty. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was risk of bias (no or unclear blinding, unclear randomization and allocation concealment, and baseline differences, downgraded two levels for risk of bias). Furthermore, the effect estimate (95% CI) crossed one of the thresholds for clinical relevance (downgraded one level for imprecision).

Time to clinical improvement (important)

Kumari (2020) reported on the outcome measure time to clinical improvement, which was not further defined. In the intervention group mean (± SD) time to symptom resolution was 7.1±1.8 days, compared to 9.6±2.1 days in the control group. The mean difference (95%CI) was -2.5 (-3.13 to -1.87) in favour of the intervention group. This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature

The evidence for the outcome measure time to clinical improvement comes from a RCT and therefore started at high certainty. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was risk of bias (unclear allocation concealment and no blinding, downgraded two levels for risk of bias). Furthermore, the effect estimate (95% CI) crossed one of the thresholds for clinical relevance (downgraded one level for imprecision).

PICO 2: Treatment with vitamin C in non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients

Thomas (2021) described an open label randomized clinical trial, the COVID A to Z study. Thomas (2021) studied the efficacy and tolerability of ascorbic acid (vitamin C) in adult ambulatory patients with mild COVID-19 disease. They included adult patients who had a new diagnosis in an outpatient setting (timing between diagnosis and inclusion unclear). Patients in the intervention group (n=48) received 8000 mg of ascorbic acid, to be divided over two to three times per day with meals. The control group (n=50) received standard care, which was not further specified. Vitamin C intake and/or levels at baseline were not reported. Patients were followed for 28 days. The primary outcome measure was the number of days to 50% reduction in symptoms, including severity of fever, cough, shortness of breath, and fatigue. In the intervention group mean (±SD) number of days until a 50% reduction in symptoms was 5.5±3.7 days, compared to 6.7±4.4 days in the control group. The following relevant outcome measures were reported: 28-day mortality, hospitalization, clinical improvement. Thomas (2021) did not report on the outcome measure respiratory support.

Table 3. Overview of RCTs comparing vitamin C with standard care in non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

|

Author |

Sample size |

Dosage |

|

Thomas, 2021 |

I: 48 C: 50 Total: 98 |

8000 mg of ascorbic acid (divided over two to three times per day with meals), for 10 days. |

Results

Mortality (crucial)

Thomas (2021) reported on the outcome measure 28-day mortality. In the intervention group, 1/48 (2.1%) died, compared to none of the 50 patients in het control group.

Level of evidence of the literature

Due to low number of events, it is not possible to draw a conclusion on the effect of treatment with vitamin C on mortality in non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Respiratory support (important)

Thomas (2021) did not report on the outcome measures respiratory support. Therefore, it is not possible to conclude on the effect of treatment with vitamin C on respiratory support and viral clearance in non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Level of evidence of the literature

-

Hospitalization (important)

Thomas (2021) reported on the outcome measure hospitalization. In the intervention group 2/48 (4.2%) patients were hospitalized, compared to 3/50 (6.0%) patients in the control group. The risk ratio (RR) (95%CI) was 0.69 (0.12 to 3.98), in favour of the intervention group. The risk difference (RD) (95%CI) was -0.02 (-0.11 to 0.07), in favour of the intervention group. This is not considered clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature

The evidence for the outcome measure mortality comes from a RCT and therefore started at high certainty. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was risk of bias (open label study, differences in number of patients lost to follow-up and study was terminated earlier due to fulfillment of criteria for futility, downgraded two levels for risk of bias). Furthermore, the effect estimate (95%CI) crossed the thresholds for clinical relevance (downgraded two levels for imprecision).

Time to clinical improvement (important)

Thomas (2021) reported on the outcome measure number of days required to reach respectively a 50% reduction in symptom severity score from peak symptom score or a symptom severity score of zero. Symptom severity score was calculated based on a four symptom questionnaire (i.e. fever/chills, shortness of breath, cough and fatigue). From patients enrolled after July 16, 2020, symptom severity score was also calculated based on an expanded list of 12 symptoms (fevers/chills, shortness of breath, cough, fatigue, muscle or body aches, headache, new loss of taste, new loss of smell, congestion or runny nose, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea). Data on the 12 symptoms severity score is only available for 33 patients and is therefore not included in our literature analysis.

Mean time (±SD) to reach a four symptom severity score of zero was 12.1±6.9 days in the intervention group, compared to 9.9±4.4 days in the control group. The difference (95%CI) was 2.22 (-0.58 to 5.02) days, in favour of the control group. This is not considered clinically relevant (<three days). In the intervention group 46/48 (95.8%) patients reached a 50% reduction in the four symptom severity score, compared to 44/50 (88.0%) patients in the control group. Mean time (±SD) to reach 50% reduction in the four symptom severity score was 5.5±3.7 days in the intervention group, compared to 6.7±4.4 day in the control group. The difference in days (95%CI) was 1.18 (-2.88 to 0.51), in favour of the intervention group. This is not considered clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature

The evidence for the outcome measure time to clinical improvement comes from a RCT and therefore started at high certainty. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was risk of bias (open label study, differences in number of patients lost to follow-up and study was terminated earlier due to fulfillment of criteria for futility, downgraded two levels for risk of bias). Furthermore, the effect estimate (95% CI) crossed one of the thresholds for clinical relevance (downgraded one level for imprecision).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effectivity of treatment with vitamin C compared to standard treatment without vitamin C in patients with COVID-19?

PICO 1

P: hospitalized with COVID-19 (subgroups mild, moderate, severe)

I: vitamin C + standard care

C: standard care only / placebo treatment + standard care

O: 28-30 day mortality (if not available, any other reports of mortality), extensive respiratory support, duration of hospitalization, time to clinical improvement

PICO 2

P: non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19

I: vitamin C + standard care

C: standard care only / placebo treatment + standard care

O: 28-30 day mortality (if not available, any other reports of mortality), respiratory support, hospitalization, time to clinical improvement

Relevant outcome measures

PICO 1: For hospitalized COVID-19 patients, mortality and need for extensive respiratory support were considered as crucial outcome measures for decision making. Duration of hospitalization and time to clinical improvement were considered as important outcome measures for decision making.

PICO 2: For non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients, mortality was considered as a critical outcome measure for decision making. Hospitalization, respiratory support and time to clinical improvement were considered as important outcome measures for decision making.

Extensive respiratory support was defined as high flow nasal cannula (HFNC)/Optiflow, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), non-invasive ventilation (NIV), mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO or ECLS). Non-invasive respiratory support was defined as supplemental oxygen low flow oxygen or non-rebreathing mask.

The working group defined 3% points absolute difference as a minimal clinically important difference for mortality (resulting in a NNT of 33), 3 days for duration of hospitalization and time to clinical improvement, 5% points absolute difference need for respiratory support and hospital admission (resulting in a NNT of 20).

The results of studies in non-hospitalized and hospitalized patients are summarized separately. Studies of hospitalized patients were categorized based on the respiratory support that was needed at baseline (preferably based on patient inclusion/exclusion criteria; otherwise on baseline characteristics). The following categories were used:

- mild disease (no supplemental oxygen);

- moderate disease (supplemental oxygen: low flow oxygen, non-rebreathing mask);

- severe disease (supplemental oxygen: high flow oxygen [high flow nasal cannula (HFNC)/Optiflow], continuous positive airway pressure [CPAP], non-invasive ventilation [NIV], mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [ECMO or ECLS]).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until January 6th, 2022. The detailed search strategy is outlined under the tab Methods. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: randomized controlled trial, peer reviewed and published in indexed journal, comparing treatment with vitamin C and standard care to standard care alone or treatment with vitamin C and standard care to placebo and standard care in patients with COVID-19.

The systematic literature search resulted in 79974 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic review or randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Five RCTs were included (JamaliMoghadamSiahkali, 2021; Kumari, 2020; Majidi, 2021; Thomas, 2021 and Zhang, 2021). The studies of Darban (2021) and Hakamifard (2021) were not included, since they studied a combination of treatments, respectively a combination of vitamin C, melatonin and zinc (Darban, 2021) and of vitamin C and vitamin E (Hakamifard, 2021).

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were conducted using Review Manager (RevMan) software 5.4. For dichotomous outcomes, Mantel Haenszel random‐effects risk ratios (RRs) and risk differences (RDs) were calculated. For continuous outcomes, a random‐effects mean difference (MD) weighted by the inverse variance was calculated. The random-effects model estimates the mean of a distribution of effects.

Results

In total, five RCTs were included in the analysis of the literature. Four studies investigated the role of vitamin C in hospitalized patients (JamaliMoghadamSiahkali, 2021; Kumari, 2020; Majidi, 2021 and Zhang, 2021; submodule 1). One study investigated vitamin C in non-hospitalized patients (Thomas, 2021; submodule 2). Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk-of-bias tables.

Referenties

- Darban, M., Malek, F., Memarian, M. et al (2021). Efficacy of high dose vitamin C, melatonin and zinc in Iranian patients with acute respiratory syndrome due to coronavirus infection: a pilot randomized trial. Journal of Cellular & Molecular Anesthesia, 6(2), 164-167.

- Fisher BJ, Seropian IM, Kraskauskas D, Thakkar JN, Voelkel NF, Fowler AA 3rd, Natarajan R. Ascorbic acid attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2011 Jun;39(6):1454-60. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182120cb8. Erratum in: Crit Care Med. 2011 Aug;39(8):2022. PMID: 21358394.

- Fowler AA 3rd, Truwit JD, Hite RD, Morris PE, DeWilde C, Priday A, Fisher B, Thacker LR 2nd, Natarajan R, Brophy DF, Sculthorpe R, Nanchal R, Syed A, Sturgill J, Martin GS, Sevransky J, Kashiouris M, Hamman S, Egan KF, Hastings A, Spencer W, Tench S, Mehkri O, Bindas J, Duggal A, Graf J, Zellner S, Yanny L, McPolin C, Hollrith T, Kramer D, Ojielo C, Damm T, Cassity E, Wieliczko A, Halquist M. Effect of Vitamin C Infusion on Organ Failure and Biomarkers of Inflammation and Vascular Injury in Patients With Sepsis and Severe Acute Respiratory Failure: The CITRIS-ALI Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019 Oct 1;322(13):1261-1270. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.11825. Erratum in: JAMA. 2020 Jan 28;323(4):379. PMID: 31573637; PMCID: PMC6777268.

- Fujii T, Luethi N, Young PJ, Frei DR, Eastwood GM, French CJ, Deane AM, Shehabi Y, Hajjar LA, Oliveira G, Udy AA, Orford N, Edney SJ, Hunt AL, Judd HL, Bitker L, Cioccari L, Naorungroj T, Yanase F, Bates S, McGain F, Hudson EP, Al-Bassam W, Dwivedi DB, Peppin C, McCracken P, Orosz J, Bailey M, Bellomo R; VITAMINS Trial Investigators. Effect of Vitamin C, Hydrocortisone, and Thiamine vs Hydrocortisone Alone on Time Alive and Free of Vasopressor Support Among Patients With Septic Shock: The VITAMINS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020 Feb 4;323(5):423-431. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.22176. PMID: 31950979; PMCID: PMC7029761.

- Hakamifard, A., Soltani, R., Maghsoudi, A. et al (2021). The effect of vitamin E and vitamin C in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia; a randomized controlled clinical trial. Immunopathol. Persa, 7.

- JamaliMoghadamSiahkali, S., Zarezade, B., Koolaji, S. et al (2021). Safety and effectiveness of high-dose vitamin C in patients with COVID-19: a randomized open-label clinical trial. European journal of medical research, 26(1), 1-9.

- Kumari, P., Dembra, S., Dembra, P. et al (2020). The role of vitamin C as adjuvant therapy in COVID-19. Cureus, 12(11).

- Lamontagne F, Masse MH, Menard J, Sprague S, Pinto R, Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Battista MC, Day AG, Guyatt GH, Kanji S, Parke R, McGuinness SP, Tirupakuzhi Vijayaraghavan BK, Annane D, Cohen D, Arabi YM, Bolduc B, Marinoff N, Rochwerg B, Millen T, Meade MO, Hand L, Watpool I, Porteous R, Young PJ, D'Aragon F, Belley-Cote EP, Carbonneau E, Clarke F, Maslove DM, Hunt M, Chassé M, Lebrasseur M, Lauzier F, Mehta S, Quiroz-Martinez H, Rewa OG, Charbonney E, Seely AJE, Kutsogiannis DJ, LeBlanc R, Mekontso-Dessap A, Mele TS, Turgeon AF, Wood G, Kohli SS, Shahin J, Twardowski P, Adhikari NKJ; LOVIT Investigators and the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Intravenous Vitamin C in Adults with Sepsis in the Intensive Care Unit. N Engl J Med. 2022 Jun 23;386(25):2387-2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2200644. Epub 2022 Jun 15. PMID: 35704292.

- Thomas, S., Patel, D., Bittel, B. et al (2021). Effect of high-dose zinc and ascorbic acid supplementation vs usual care on symptom length and reduction among ambulatory patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: the COVID A to Z randomized clinical trial. JAMA network open, 4(2), e210369-e210369.

- Wei XB, Wang ZH, Liao XL, Guo WX, Wen JY, Qin TH, Wang SH. Efficacy of vitamin C in patients with sepsis: An updated meta-analysis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020 Feb 5;868:172889. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.172889. Epub 2019 Dec 21. PMID: 31870831.

- Zhang, J., Rao, X., Li, Y. et al (2021). Pilot trial of high-dose vitamin C in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Annals of intensive care, 11(1), 1-12.

Evidence tabellen

Research question: What is the role of vitamin C in the treatment of patients with COVID-19?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Hospitalized |

|||||||

|

JamaliMoghadamSiahkali, 2021 |

Type of study: RCT, open-label

Setting and country: Ziaeian Hospital, Tehran, Iran

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funding by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, authors declared to have no competing interests.

|

COVID-19 patients, (hospitalized, moderate to severe disease)

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: N = 60 Intervention: 30 Control: 30

Important characteristics: Age, mean (SD): I: 57.5 y (18.27) C: 61 y (15.90) P=0.436

Sex, n/N (%) male: I: 15/30 (50%) C: 15/30 (50%) P>0.90

Severity score, mean (/10) (SD):* I: 3.57 (1.36) C: 3.40 (1.48) P=0.651 *It is not clear whether this score was calculated at baseline or during follow-up.

Groups comparable at baseline? No, % patients with ischemic heart disease, fever, myalgia, chest pain, headache, sputum, haemoptysis, positive PCR test was higher in control group, and vice versa for hypertension. Intake of vitamin C/vitamin C level was not reported. |

Vitamin C

1.5 g vitamin C IV every 6 h for 5 days + standard of care

|

Standard of care

Standard of care: all of the participants were also treated with oral lopinavir/ritonavir 400/100 mg twice daily and single stat dose of oral hydroxychloroquine (400 mg) on the first day of hospitalization according to the Iranian COVID-19 treatment protocol at time of this study.

|

Length of follow-up: Until discharge

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 0/30 (0%) Reasons: NA

Control: 0/30 (0%) Reasons: NA

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: NR Reasons: NA

Control: N (%) Reasons: NA

|

Mortality (28-30 day) - crucial Not reported

Mortality, n/N (%):* I: 3/30 (10%) C: 3/30 (10%) P>0.05 *Follow-up not clear

Respiratory support - mechanical respiratory support, optiflow - crucial Intubated, n/N (%) I: 5/30 (16.7) C: 4/30 (13.3) P >0.9

Duration of hospitalization - important ICU length of stay (days), median (IQR): I: 5.50 (5.0 to 10.0) C: 5.0 (5.0 to 7.0) P=0.381

Hospital length of stay (days), median (IQR): I: 8.50 (7.0 to 12.0) C: 6.50 (4.0 to 12.) P=0.028

Time to symptom resolution - important Not reported

Respiratory support - non-invasive respiratory support - important Not reported

Adverse events - important None of the patients experienced adverse events such as head ache, nausea, bloating, or abdominal discomfort.

Viral clearance - important Not reported

|

Definitions: Severity score: Calculated based on the scoring system suggested by Altschul for prediction of inpatient mortality in COVID-19 patients.

Remarks: Randomization and allocation concealment are not clearly described. Furthermore, groups differed at baseline.

Authors conclusion: In this study, we found that there were improvements in peripheral oxygen saturation and body temperature in both groups during the time of admission, but we did not find significantly better outcomes in the group who were treated with high-dose vitamin C in addition to the main treatment regimen at discharge.

|

|

Zhang, 2021 |

Type of study: RCT, blinded, pilot, multicentre

Setting and country: ICU’s of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, Leishenshan Hospital and Taihe Hospital, China, enrolment between Feb 14, 2020 to March 29, 2020.

Funding and conflicts of interest: Science and Technology Department of Hubei Province and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities. Authors declared to have no competing interests.

|

COVID-19 patients, (hospitalized, severe disease)

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: N = 56 Intervention: 27 Control: 29

Important characteristics: Age, mean ± SD: I: 66.3 ± 11.2 y C: 67.0 ± 14.3 y

Sex, n/N (%) male: I: 15/27 (55.6) C: 22/29 (75.9)

Median duration of symptoms before therapy, days, median (IQR) I: 22.0 (11.0–33.0) C: 15.0 (11.0–22.0)

APACHE II score I: 14.0 (11.0–16.0) C: 13.0 (9.5–15.0) P= 0.24

GCS score I: 15.0 (13.0–15.0) C: 15.0 (15.0–15.0) P= 0.75

Groups comparable at baseline? No, gender was not equally distributed over the groups (male > in placebo group). Intake of vitamin C/vitamin C level was not reported. |

Vitamin C

24 g vitamin C per day for 7 days+ standard of care

Patients were infused with 12 g vitamin C diluted in 50 ml of bacteriostatic water every 12 hours at a rate of 12 ml/hour by infusion pump for 7 days; infused via central vein catheterization controlled by a pump.

|

Placebo + standard of care

50 ml of bacteriostatic water infused every 12 hours at a rate of 12 ml/hour by infusion pump for 7 days; Infused via central vein catheterization controlled by a pump.

Standard of care consist of other general treatments followed the latest COVID-19 guidelines. Oseltamivir and azithromycin (usually in general ward), LMWH (after ICU admission), Piperacillin/tazobactam (when receiving tracheal intubation), hydrocortisone (1 mg/kg/day, considered in case of rapid deterioration, severe ARDS or septic shock), respiratory support (IMV, NIV and HFNC, in case of hypoxic respiratory failure and ARDS), intubation (in case of further deterioration). ECMO was considered as the rescue therapy. |

Length of follow-up: 28 days

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 0/27 (0%) Reasons: NA

Control: 0/27 (0%) Reasons: NA

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: NR Reasons: NA

Control: N (%) Reasons: NA

|

Mortality (28-30 day) - crucial Mortality, 28-day, n,(%) I: 6 (22.2) C: 10 (34.5) HR 0.5 (0.2 to 1.8) P=0.31 Mortality patients SOFA ≥ 3, n (%) I: 5 (21.7) C: 10 (47.6) HR 0.3 (0.1 to 1.1) P=0.07

Mortality, n/N (%):* ICU mortality, n (%) I: 6 (22.2) C: 11 (37.9) HR 0.5 (0.2 to 1.5) P=0.20 ICU mortality patients SOFA ≥3, n (%) I: 5 (21.7) C: 11 (52.4) HR 0.2(0.1 to 0.9) P=0.04

Respiratory support - mechanical respiratory support, optiflow - crucial Invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV)-free days in 28 days, median (IQR): I: 26.0 (9.0–28.0) C: 22.0 (8.5–28.0) Diff coeff. 1.3(− 4.7 to 7.2) P=0.57 IMV days to day 28, days I: 1.5 (0.0-19.0) C: 6.0 (0.0–16.0) Diff coeff. − 0.8 (− 6.4 to 4.9) P=0.60 High flow nasal cannula (HFNC) days to day 28, days I: 0.5 (0.0-8.3) C: 2.0 (0.0 -7.0) Diff coeff. 0.2 (− 2.9 to 3.3) P=0.85

Oxygen-support category HFNC Day 1 I: 7 (25.9) C: 11 (37.9) OR 0.6 (0.2 to 1.8) P=0.40 Day 7 I: 11 (47.8) C: 9 (39.1) OR 14.3 (0.4 to 4.6) P= 0.77 IMV Day 1 I: 11 (40.7) C: 12 (41.3) OR 1.0 (0.3 to 2.9) P=1.00 Day 7 I: 10 (43.5) C: 11 (47.8) OR 0.8 (0.3 to 2.7) P=1.00

Duration of hospitalization - important Length of ICU stay, days ± SD I: 22.9 ± 14.8 C: 17.8 ± 13.3 Diff coeff 5.0 (− 2.5 to 12.7) P=0.20 Length of hospital stay, days ± SD I: 35.0 ± 17.0 C: 32.8 ± 17.0 Diff coeff 2.2(− 7.5 to 11.8) P=0.65

Time to symptom resolution - important Patient condition improvement rate, n (%) I: 5 (19.2) C: 6 (21.4) Diff coeff. 0.9 (0.2 to 3.3) P=0.84

Respiratory support - non-invasive respiratory support - important Non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIV) days to day 28, days I: 0.0 (0.0 -3.3) C: 0.0 (0.0-1.8) Diff coeff. 1.2 (− 1.2 to 3.7) Non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIV), n %) Day 1 I: 7 (25.9) C: 7 (24.1) OR 1.1 (0.3 to 3.7) P=1.00 Day 7 I: 7 (30.4) C: 2 (8.7) OR 4.6 (0.8 to 25.2) P=0.14

Adverse events - important Serum creatinine during 7-day infusion period: I: Day 1: 64.20[46.58–85.45] Day 7: 57.50[39.95–71] umol/L C: Day 1: 64.20[52.00 -81.70] Day 7: 63.50[51.70–104.50] umol/L “There were no changes in total bilirubin from day 1 to day 7 in HDIVC, while there was a slight increase from day 1 to day 7 in placebo.” Study related AE’s I: 0; C: 0 SAE’s requiring stop study participation I: 0; C: 0

Complications Septic shock (n (%) I:9 (34.6) C: 8 (28.6) OR (95%CI): 1.3 (0.4 to 2.4) P= 0.77

Acute cardiac injury (n (%) I: 7 (26.9) C: 13 (48.1) OR (95%CI): 0.4 (0.1 to 1.3) P= 0.16

Acute liver injury (n (%) I: 12 (48.0) C: 13 (48.1) OR (95%CI): 1.0 (0.3 to 3.0) P= 1.00

Acute kidney injury (n (%) I: 3 (12.0) C: 6 (22.2) OR (95%CI): 0.5 (0.1 to 2.2) P= 0.50

Coagulation disorders (n (%) I: 9 (34.6) C: 7 (25.9) OR (95%CI): 1.5 (0.5 to 5.0) P= 0.56

Viral clearance - important Not reported

|

Definitions: Invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV)-free days in 28 days The number of days a patient was extubated after recruitment to day 28; if the patient died with MV, a value of zero was assigned Patient condition improvement rate; The patient requiring ECMO or IMV on day 1 and switching to HFNC, NIV, or discharged from the ICU after 7 days of treatment.

Remarks:

Authors conclusion: “[….] this pilot trial showed that HDIVC (= High-dose intraven. vitamin C) did not improve the primary endpoint, IMVFD28 (= Invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV)-free days in 28 days), but demonstrated a potential signal of benefit for critically ill COVID-19, with an improvement in P/F ratio.”

|

|

Kumari, 2020 |

Type of study: RCT, open-label

Setting and country: tertiary hospital in Pakistan, enrolment between March to July 2020.

Funding and conflicts: Authors declared to have no competing interests.

|

COVID-19 patients, (hospitalized, severe disease)

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria, e.g.:

N total at baseline: N = 150 Intervention: 75 Control: 75

Important characteristics: Age, mean (SD): I: 52 y (11) C: 53 y (12)

Sex, n/N (%) male: I: NR C: NR Total: 99/150 (56.9)

Disease severity: not reported

Oxygen saturation, mean (SD) I: 87.2 (4.6) C: 86.1 (4.9)

Groups comparable at baseline? Unclear, since important parameters are not reported. |

Vitamin C

50 mg/kg/day of IV VC in addition to standard therapy (for details, see control group)

|

Control

Standard therapy, which included antipyretics, dexamethasone, and prophylactic antibiotics

|

Length of follow up: Unclear

Loss to follow-up: Intervention: N=0 Reason: NA Control: N=0 Reason: NA

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: NR Reasons: NA

Control: N (%) Reasons: NA

|

Mortality (28-30 day), n/N (%) - crucial I: 7/75 (9.3) C: 11/75 (14.60 P=0.31

Respiratory support - mechanical respiratory support, optiflow, n/N (%) - crucial I: 12/75 (16) C:15/75 (20) P=0.406

Duration of hospitalization, mean ±SD I: 8.1±1.8 C: 10.7±2.2 P<0.0001

Time to symptom resolution – important, mean ± SD I: 7.1±1.8 C: 9.6±2.1 P<0.0001

Respiratory support - non-invasive respiratory support - important Not reported

Adverse events – important Not reported

Viral clearance - important Not reported

|

Definitions: -

Remarks: -

Authors conclusion: Based on our findings, VC can significantly improve clinical symptoms of patients affected with SARS-CoV-2 and reduce days spent in the hospital; however, VC supplementation had no impact on mortality and the need for mechanical ventilation. Nevertheless, VC has been proven to improve immunity in various forms of virus infections, and more studies on a larger scale are needed to further assess the role of VC in the

|

|

Majidi, 2021 |

Type of study: RCT, double-blind

Setting and country: Razi hospital in Iran, enrolment between May 2020 to July 2020.

Funding and conflicts:

|

COVID-19 patients, (hospitalized, severe disease)

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria, e.g.:

N total at baseline: N = 120 (100 included in analysis) Intervention: 40 (31 included in analysis( Control: 80 (69 included in analysis)

Important characteristics: Age, mean (SD): I: 59.42 y (15.07) C: 63.82 y (14.58)

Sex, n/N (%) male: I: 19/31 (61%) C: 41/69 (58%)

Disease severity: not reported

APACHE II, score (SD) I: 15.50 (1.69) C: 15.43 (1.93)

Groups comparable at baseline? Unknown, since important parameters are not reported.

|

Vitamin C

One capsule of 500 mg of vitamin C daily by adding the supplement to their enteral feeding. Patients received a high protein enteral formula.

|

Control

The same nutritional support using the same route, although no vitamin C was added to their enteral feeding. Patients received a high protein enteral formula.

|

Length of follow up: Unclear

Loss to follow-up: Intervention: N=9 Reason: death (N=3), no indication for enteral feeding/ vitamin C (N=6)

Control: N=11 Reason: death (N=4), no indication for enteral feeding/ vitamin C (N=7)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: NR Reasons: NA

Control: N (%) Reasons: NA

|

Mortality (28-30 day) - crucial Not reported

Survival (day 14), n/N* I: 16.1% C: 2.9% (p = 0.028)

Respiratory support - mechanical respiratory support, optiflow - crucial Not reported

Hospitalization, n/N (%) Not reported

Time to symptom resolution - important Not reported

Respiratory support - non-invasive respiratory support - important Not reported

Adverse events – important Not reported**

Viral clearance - important Not reported

|

Definitions: N.A.

Remarks: *Survival duration of the patients had a linear positive association with the duration of vitamin C supplementation. Crude model 1: B = 1.66, p = 0.001 Model adjusted by age and BMI : B= 1.59, p = 0.001 Model further adjusted by APACHE II, underlying diseases, use of ventilator and nutrition therapy: B=1.27, p = 0.001

**The results of this study indicated that the vitamin C supplementation had no adverse effect: data on kidney function, ABG parameters, GCS, CBC, and other serum electrolytes are available.

Authors conclusion: The results of this study indicated a significant negative correlation between vitamin C supplementation with the level of serum K in patientswithCOVID-19. Daily supplementation of 500 mg vitamin C resulted in an increase in the survival duration of the patients. Our results further indicated that vitamin C supplementation had no effect on kidney function, ABG parameters, GCS, CBC, and other serum electrolytes such as Na, Ca, and P. Further clinical studies are needed to confirm the effect of vitamin C and on COVID-19.

|

|

Non-hospitalized |

|||||||

|

Thomas, 2021 |

Type of study: RCT, open-label

Setting and country: Ambulatory setting, multiple hospitals within a single health system in USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funding is unclear. Dr McWilliams reported receiving consulting fees from Gilead Sciences outside the submitted work. Dr Desai reported receiving grants from Myokardia outside the submitted work and being supported by the Haslam Family Endowed Chair in Cardiovascular Medicine. No other disclosures were reported.

|

COVID-19 patients, (non-hospitalized, mild disease)

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: N = 214 Intervention 1: N=48 Control: N=50

Important characteristics: Age, mean (SD): I1: 45.6 (15.0) years C: 42.0 (14.6) years

Sex, n/N (%) female: I1: 33/48 (68.8%) C: 31/50 (62.0%)

Disease severity: 4-component score I1: 4.0 (3.0 to 6.0) C: 4.0 (3.0 to 5.0) Total: 4.0 (3.0 to 5.0)

12-component score I1: 12.5 (7.0 to 18.0) C: 11.0 (7.0 to 15.0) Total: 11.0 (7.0 to 15.0)

Groups comparable at baseline? Intake of vitamin C/vitamin C level was not reported.

|

Intervention 1: 8000 mg of ascorbic acid (to be divided over 2-3 times per day with meals)

|

Control: Usual care without any study medications. |

Length of follow up: 28 days

Loss to follow-up: Control: -N=7 was lost to follow-up; Intervention 1: - N=14 did not complete follow up; - N=7 was lost to follow-up; - N=7 discontinued intervention - N=1 hospitalized - N=4 other

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: NR Reasons: NA

Control: N (%) Reasons: NA

|

Mortality (28-30 day) - crucial I1: 1/48 (2.1) C: 0/50 (0)

Respiratory support - mechanical respiratory support, optiflow - crucial Not reported

Hospitalization, n/N (%) I1: 2/48 (4.2) C: 3/50 (6.0)

Time to symptom resolution - important 4-symptom scale Patients meeting 50% reduction, n/N (%): I1: 46/48 (95.8) C: 44/50 (88.0)

Time to 50% reduction (days), mean (SD): I1: 5.5 (3.7) C: 6.7 (4.4) Difference (95% CI): -1.18 (-2.88 to 0.51)

12-symptom scale Patients meeting 50% reduction, n/N (%): I1: 14/14 (100%) C: 18/19 (94.7%)

Time to 50% reduction (days), mean (SD): I1: 6.6 (3.7) C: 6.2 (2.9) Difference (95% CI): 0.40 (-1.99 to 2.80)

Time until 4-symptom composite score is 0 Time in days, mean (SD): I1: 12.1 (6.9) C: 9.9 (4.4) Difference (95%CI): 2.22 (-0.58 to 5.02)

Composite 4-symptom score at day 5 Score, mean (SD): I1: 3.3 (2.1) C: 3.1 (2.3) Difference (95% CI): 0.27 (-0.64 to 1.18)

Respiratory support - non-invasive respiratory support - important Not reported

Adverse events – important Adverse events, n/N (%) I: 17/43 (39.5)* C: 0/46 (0) *headache (n=1), nausea (n=6), vomiting (n=1), tingling (n=1), stomach pains/cramps (n=5), diarrhoea (n=7), dizziness (n=1), other (n=1)

Serious adverse events In the four study arms, 4 serious adverse events were noted: - N=3: died due to COVID-19 - N=1: hospital admission for COPD exacerbation Not caused by individual treatments provided in this study.

Viral clearance - important Not reported

|

Definitions: Disease severity Baseline composite COVID-19 symptom score (four versus 12 symptoms).

Remarks:

Authors conclusion: In this randomized clinical trial, ambulatory patients diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2, treatment were treated with high doses of zinc gluconate, ascorbic acid, or a combination of zinc gluconate and ascorbic acid. These interventions did not significantly shorten the duration of symptoms associated with the virus compared with usual care.

|

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

Research question: What is the role of vitamin C in the treatment of patients with COVID-19?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Hospitalized patients |

|||||||

|

JamaliMoghadamSiahkali, 2021 |

No information

|

No information |

Definitely no

Reason: open-label study (further details on blinding were not provided) |

Definitely yes

Reason: none of the patients was lost to follow-up |

Definitely yes

All predefined outcome measures were reported |

Probably no

Reason: Groups were different at baseline, not placebo controlled, vitamin C intake/levels not reported à baseline differences? |

HIGH All outcome measures

Reason: randomization and allocation concealment are not clear, baseline differences, no information about vitamin C levels/intake, not placebo controlled (not for mortality) and open-label study (not for mortality). |

|

Zhang, 2021 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: an independent random numeric table was generated by Microsoft Excel 2019 by the primary investigator

|

Probably yes;

Reason: the generated random list was stored by the principal investigator who was not involved in the treatment of patients and hidden to the other investigators.

|

Probably yes;

Reason: grouping and intervention were unknown to participants and investigators, intervention and placebo were identical, it is however not sure whether care givers were blinded. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: none of the patients was lost to follow-up |

Probably no;

Reason: Outcome measure patient improvement was not described in the protocol, ventilator parameters should have been reported for day 10 and 28 in stead of day 1 and 7 and in the protocol the primary outcome measure did not focus on invasive ventilation free days. |

Probably no;

Reason: gender was not equally distributed over the groups (male > in placebo group), vitamin C intake/levels not reported à baseline differences? |

HIGH All outcome measures

Reason: gender was not equally distributed, no information about vitamin C levels/intake, blinding of care givers was not clear and for outcome measures time to symptom resolution and respiratory support: risk of selective reporting.

|

|

Majidi, 2021 |

Definitely yes;

The allocation to the groups was done through webbased randomization. |

Definitely yes;

Sealed non-transparent envelopes with randomized sequences were used to hide the allocation. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: This study was double blinded. Vitamin C supplementation was done by a nurse who was not a member of the research team. The required information about the desired outcomes was collected by another nurse. The results were analyzed by a person outside of the treatment team. |

Definitely yes;

Numbers and reasons for loss to follow-up were not different between the groups. |

Probably yes;

The outcome measure survival at the ICU was not specified in the protocol. |

Definitely no;

Reason: vitamin C intake/levels not reported à baseline differences? No intention to treat analysis. |

SOME CONCERNS

Reason: no information about vitamin C levels/intake, risk of selective reporting and no intention to treat analysis. |

|

Kumari, 2020 |

Definitely yes;

Patients were randomized using a randomizer software. |

No information |

Definitely no

Reason: open-label study (further details on blinding were not provided) |

No information |

Definitely yes

All predefined outcome measures were reported |

Probably no

Reason: not placebo controlled, vitamin C intake/levels not reported à baseline differences? |

HIGH All outcome measures

Reason: allocation concealment was not clear, no information about vitamin C levels/intake, no information on follow-up, not placebo controlled (not for mortality) and open-label study (not for mortality). |

|

Non-hospitalized patients |

|||||||

|

Thomas, 2021 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: the randomization grid was designed via the REDCap database and based on 25% of anticipated enrolled patients in each of the 4 groups. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: an automatically created link in REDCap randomized the patient to the supplement group based on the randomization grid. |

Definitely no;

Reason: open-label study |

Probably no;

Reason: number of lost to follow-up differed between the groups. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: all predefined outcome measures were reported |

Probably yes;

Reason: Study was terminated earlier, since criteria for futility were met and not placebo controlled, funding is not clear, no information about vitamin C levels/intake à baseline differences? |

HIGH All outcome measures

Reason: open-label study (not for mortality), no information about vitamin C levels/intake, number of follow-up and corresponding reasons differed between the groups and study was terminated earlier due to fulfilment of criteria for futility. |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 07-11-2022

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 03-10-2022

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut). Deze ondersteuning werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De werkgroep werd gefinancierd uit een VWS subsidie.

De financiers hebben geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodules is in 2020 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de behandeling van patiënten met COVID-19.

In 2020 is een multidisciplinair expertiseteam behandeling ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van het expertiseteam behandeling) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met COVID-19. Dit expertiseteam fungeerde als stuurgroep, welke opdracht heeft gegeven tot het ontwikkelen van de module, alsmede fungeerde als klankbordgroep.

Werkgroep

- Dr. Marjolein Hensgens, internist-infectioloog, Afdeling Infectieziekten, UMC Utrecht en LUMC Leiden (Stichting Werkgroep Antibiotica Beleid)

- Drs. Emilie Gieling, apotheker, Afdeling Klinische Farmacie, UMC Utrecht.

- Prof. Dr. Dylan de Lange, intensivist, Afdeling Intensive Care, UMC Utrecht.

- Dr. Wim Boersma, longarts, Afdeling Longziekten, Noordwest Ziekenhuisgroep, Alkmaar.

- Dr. Paul van der Linden, apotheker, Afdeling Klinische Farmacie, Tergooi MC, Hilversum (Stichting Werkgroep Antibiotica Beleid).

- Prof. Dr. Bhanu Sinha, arts-microbioloog, Afdeling Medische Microbiologie & Infectiepreventie, UMCG, Groningen (Stichting Werkgroep Antibiotica Beleid).

- Dr. Mark de Boer, internist-infectioloog, Afdelingen Infectieziekten en Klinische Epidemiologie, LUMC, Leiden (Stichting Werkgroep Antibiotica Beleid).

- Tot 1-11-2021 tevens deel van de werkgroep: Dr. Albert Vollaard, internist-infectioloog, LCI, RIVM

Stuurgroep (expertiseteam Behandeling COVID-19)

- Dr. L.M. van den Toorn (voorzitter), longarts, Erasmus Medisch Centrum (Erasmus MC), NVALT

- Dr. M.G.J. de Boer, internist-infectioloog, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum (LUMC), SWAB/NIV)

- Drs. A.J. Meinders, internist-intensivist, St. Antonius Ziekenhuis, NVIC

- Prof. dr. D.W. de Lange, intensivist-toxicoloog, Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht (UMC Utrecht), NVIC

- Dr. C.H.S.B. van den Berg, infectioloog-intensivist Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen (UMCG), NVIC

- Dr. S.U.C. Sankatsing, internist-infectioloog, Diakonessenhuis, NIV

- Dr. E.J.G. Peters, internist-infectioloog, Amsterdam University Medical Centers (Amsterdam UMC), NIV

- Drs. M.S. Boddaert, arts palliatieve geneeskunde, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum (LUMC), IKNL

- Dr. P.L.A. Fraaij, kinderarts-infectioloog, Erasmus Medisch Centrum (Erasmus MC), Sophia Kinderziekenhuis, NVK

- Dr. E. van Leeuwen, gynaecoloog, Amsterdam University Medical Centers (Amsterdam UMC), NVOG

- Dr. J.J. van Kampen, arts-microbioloog, Erasmus Medisch Centrum (Erasmus MC), NVMM

- Dr. M. Bulatović-Ćalasan, internist allergoloog-immunoloog en klinisch farmacoloog, Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht (UMC Utrecht), Amsterdam University Medical Centers (Amsterdam UMC), NIV

- Drs. A.F.J. de Bruin, anesthesioloog-intensivist, St. Antonius Ziekenhuis, NVA

- Drs. A. Jacobs, klinisch geriater, Catharina Ziekenhuis, NVKG

- Drs. B. Hendriks, ziekenhuisapotheker, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum (LUMC), NVZA

- Drs. M. Nijs, huisarts, NHG

- Dr. S.N. Hofstede, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten

Meelezer

- Drs. K. (Klaartje) Spijkers, senior adviseur patiëntenbelang, Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, Utrecht

Met ondersteuning van:

- dr. S.N. Hofstede, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten

- dr. L.M.P. Wesselman, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten

- dr. D. Nieboer, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten

- drs. A.L.J. (Andrea) Kortlever - van der Spek, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten

-

M. Griekspoor MSc., junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten

- drs. I. van Dusseldorp, senior literatuurspecialist, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

De Lange |

1. Afdelingshoofd Nationaal Vergiftigingen Informatie Centrum (NVIC) van het UMC Utrecht (0,6 fte) |

Secretaris Stichting Nationale Intensive Care Evaluatie (Stichting NICE), onbezoldigd. |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

|

De Boer |

Internist-Infectioloog, klinisch epidemioloog, senior medisch specialist, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum, afdeling Infectieziekten |

- Voorzitter Stichting Werkgroep Antibioticabeleid (onkostenvergoeding) |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

|

Sinha |

Arts-microbioloog/hoogleraar, Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen (voltijd) (zie ook https;//www.rug.nl/staff/b.sinha/) |

- SWAB-bestuur: secretaris [onbetaald; vacatiegeld voor instelling] |

- Projectsubsidie EU (Cofund): deelprojecten, cofinanciering

Mogelijk boedbeeldfunctie SWAB |

Geen actie nodig |

|

Van der Linden |

Ziekenhuisapotheker |

Penningmeester SWAB, vacatiegeld |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

|

Vollaard |

Internist-infectioloog, Landelijke Coordinatie Infectieziektebestrijding, RIVM |

Arts voor ongedocumenteerde migranten, Dokters van de Wereld, Amsterdam (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

|

Gieling |

Ziekenhuisapotheker - Klinisch Farmacoloog, UMC Utrecht |

Lid OMT Nederlandse Vereniging voor Ziekenhuisapothekers (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

|

Boersma |

Longarts Noordwest Ziekhuisgroep |

Lid sectie infectieziekten NVALT, onbetaald |

Eenmalige digitale deelname aan adviesraad MSD Pneumovax over Pneumococcal disease, betaald

|

Geen actie nodig |

|

Hensgens |

Internist-infectioloog, UMC Utrecht (0.8 aanstelling, waarvan nu 0.4 gedetacheerd naar LUMC) Internist-infectioloog, LUMC (via detachering, zie boven) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

Stuurgroep

|

Achternaam stuurgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Van den Toorn (voorzitter) |

Voorzitter NVALT |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

|

De Boer |

Internist-Infectioloog, senior medisch specialist, LUMC, afdeling infectieziekten |

- Voorzitter Stichting Werkgroep Antibioticabeleid (onkostenvergoeding) |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

|

Meinders |

Internist-intensivist, St.-Antonius ziekenhuis, Nieuwegein |

commissie werk |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

|

De Lange |

Afdelingshoofd Nationaal Vergiftigingen Informatie Centrum (NVIC) van het UMC Utrecht |

secretaris Stichting Nationale Intensive Care Evaluatie (Stichting NICE) (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

|

Van den Berg |

Infectioloog-intensivist, UMCG |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

|

Sankatsing |

Internist-infectioloog/internist-acute geneeskunde, Diakonessenhuis, Utrecht |

- Bestuurslid Nederlandse Vereniging van Internist-Infectiologen (NVII) (onbetaald). |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

|

Peters |

Internist - aandachtsgebieden infectieziekten en Acute Geneeskunde Amsterdam UMC, locatie Vumc |

Wetenschappelijk Secretaris International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

|

Boddaert |

Medisch adviseur bij Integraal Kankercentrum Nederland (IKNL) en Palliatieve Zorg Nederland (PZNL) Arts palliatieve geneeskunde in LUMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

|

Fraaij |

Kinderarts infectioloog- immunoloog, Erasmus MC-Sophia, Rotterdam |

Bestuur Stichting Infecties bij Kinderen (onbetaald) |

deelname aan RECOVER, European Union's Horizon 2020 research |

Geen actie nodig |

|

Van Leeuwen |

Gyaecoloog Amsterdam Universitair Medisch Centra |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

|

Van Kampen |

Arts-microbioloog, afdeling Viroscience, Erasmus MC |

- associate editor antimicrobial resistance & infection control (onbetaald) - lid antibioticacommissie Erasmus MC (onbetaald) |

1. Mede uitvinder patent: 1519780601-1408/3023503 2. R01AI147330 (NIAID/NH) (HN onderzoek (1+2 niet gerelateerd aan COVID-19)

|

Geen actie nodig |

|

Bulatovic |

Internist allergoloog-immunoloog en klinische farmacoloog, UMC Utrecht en Diakonessenhuis Utrecht |

Functie 1: arts |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

|

De Bruin |

Anesthesioloog - Intensivist St. Antonius ziekenhuis Nieuwegein en Utrecht |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

|

Jacobs |

Klinisch geriater en klinisch farmacoloog |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

|

Hendriks |

Ziekenhuisapotheker farmaceutische patiëntenzorg, afd. Kiinische Farmacie en Toxicoiogie, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum |

Lid SWAB werkgroep surveillance antibioticagebruik, onbetaald Lid SWAB richtlijncommissie antibiotica allergie, onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

|

Nijs |

Huisarts |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

|

Hofstede |

Senior adviseur Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

Meelezer

|

Achternaam |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Spijkers |

Senior adviseur patiëntenbelang |

Voorzitter Stichting Samen voor Duchenne |

Geen |

Geen actie nodig |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door een afgevaardigde patiëntenvereniging in de klankbordgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de module. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Werkwijze

Van leidraad naar richtlijnmodules

Bij aanvang van de pandemie in 2020 was het onduidelijk of bestaande of nieuwe medicijnen een relevante bijdrage konden leveren aan het herstel van patiënten geïnfecteerd met het SARS-CoV-2. Vandaar dat eind februari 2020 werd aangevangen met de eerste versie van de leidraad ‘Medicamenteuze behandeling voor patiënten met COVID-19 (infectie met SARS–CoV-2)’, welke begin maart 2020 online beschikbaar werd gesteld op de website van de SWAB (https://swab.nl/nl/covid-19). Sindsdien werd het adviesdocument op wekelijkse basis gereviseerd en indien nodig op basis van nieuwe publicaties van onderzoek aangepast. Het initiatief en de coördinatie hiertoe werden genomen door de SWAB Leidraadcommissie, ondersteund door het kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en een brede klankbordgroep waarbinnen de betrokken specialisten(verenigingen) zijn vertegenwoordigd. In september 2021 is gestart met het doorontwikkelen van de leidraad naar richtlijnmodules.

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de COVID-19 pandemie zijn knelpunten op verschillende manieren geïnventariseerd:

1. De expertiseteams benoemde de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met COVID-19.

2. Er is een mailadres geopend (covid19@demedischspecialist.nl) waar verschillende partijen knelpunten konden aandragen, die vervolgens door de expertiseteams geprioriteerd werden.

3. Door de Federatie van Medisch Specialisten zijn webinars georganiseerd waarbij vragen konden worden ingestuurd. Deze vragen zijn na afloop van de webinars voorgelegd aan de expertiseteams en geprioriteerd.

Uitkomstmaten