Remdesivir

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van remdesivir bij de behandeling van COVID-19 patiënten?

Aanbeveling

Remdesivir wordt niet aanbevolen als standaardbehandeling van opgenomen patiënten met COVID-19

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de verschillen in klinische uitkomsten tussen behandeling met en zonder remdesivir bij patiënten met COVID-19. Tot 17 oktober 2021 werden er 6 gerandomiseerde gecontroleerde studies (RCTs) gevonden met in totaal 4289 patiënten in de remdesivir-groep en 3925 in de controle-groep. Een zevende studie (Barratt-Due, 2021) rapporteerde data van een subgroep van Noorse patiënten uit de Solidarity trial (Pan, 2020). In deze studie werd nieuwe data gepubliceerd over de mogelijke antivirale effecten van remdesivir en er werd gedetailleerde klinisch informatie beschreven. De studie van Barratt-Due werd daarom alleen meegenomen bij de evaluatie van specifieke subgroepen.

Omdat de geïncludeerde studies heterogene patiëntgroepen bevatten, zijn de resultaten, waar mogelijk, opgesplitst voor patiënten met milde, matige en ernstige COVID-19 symptomen op basis van respiratoire ondersteuning bij inclusie. Er werden alleen RCTs geïncludeerd in de analyse, waardoor de kwaliteit van bewijs initieel hoog was. Omdat er vijf ongeblindeerde of open-label trials waren, met een mogelijk risico op vertekening van de studieresultaten (risk of bias) bij subjectieve uitkomstmaten, werd de kwaliteit van dit bewijs waar nodig naar beneden bijgesteld. Daarnaast waren er meerdere studies met een relatief kleine populatie en mede hierdoor een grote spreiding van de puntschatter van de uitkomstmaat (imprecision), waardoor de kwaliteit van dit bewijs ook naar beneden werd bijgesteld. Eventueel werd de kwaliteit van het bewijs naar beneden bijgesteld als er veel heterogeniteit tussen de studies was, bijvoorbeeld in rapportage van de uitkomstmaat. De geïncludeerde patiënten verschilden ook per studie (bijvoorbeeld in de ernst van ziekte bij inclusie). Deze verschillen in inclusie werden niet meegenomen in de gradering van de studies, maar zullen wel worden meegenomen in de overwegingen.

Mortaliteit

Op basis van de gevonden resultaten kan worden geconcludeerd dat er voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat ‘mortaliteit’, geen voordeel is voor behandeling van opgenomen patiënten met remdesivir (risicoverschil: 0.01, 95%CI -0.01 tot 0.02; relatief risico 0.93, 95% CI 0.74-1.16). Dit is gebaseerd op 6 studies en heeft bewijskracht moderate.

In de studie van Beigel (2020) werd er wel een voordeel gezien van remdesivir op de mortaliteit na 28-29 dagen in de mensen met matig ernstige ziekte (patiënten met alleen extra zuurstof bij opname, maar geen vorm van invasieve beademing; ziekte ernst ‘moderate’ in Figuur 2). De studie van Ader (2021) en Pan (2020) bevestigden deze bevinding niet. Na het poolen en wegen van de data van de drie studies waren deze resultaten niet statistisch significant (risicoverschil: 3%, 95%CI -1% tot 7% en relatief risico 0.69, 95%CI 0.38 tot 1.23). De studie van Wang (2020) beschrijft geen specifieke subgroepen, maar ruim 80% van de populatie bestond uit patiënten die nog niet ernstig zuurstofbehoeftig waren (wel zuurstoftoediening, maar geen invasieve beademing). In deze studie werd er ook geen voordeel van remdesivir gezien op de mortaliteit. Patiënten in deze studie werden wel relatief laat behandeld: na gemiddeld 10 dagen klachten. In subgroep analyses bij patiënten met een (matig) ernstige COVID-19 infectie werd er ook geen statistisch significant mortaliteitsverschil aangetoond in de verschillende studies.

De publicatie van Pan (2020) was een interim analyse van de Solidarity trial. In mei 2022 verscheen de publicatie waarin de eindresultaten gepubliceerd werden (WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium, 2022). Ook in deze analyse werd er voor opgenomen patiënten met COVID-19 (milde, matige en ernstige COVID-19 samengenomen) geen voordeel gezien van behandeling met remdesivir. Echter, bij een subgroep analyse van patiënten met alleen extra zuurstofbehoefte maar geen noodzaak tot invasieve beademing was er wel een klein voordeel bij analyse van de mortaliteit in het ziekenhuis (14,6% overleed in de groep met remdesivir ten opzichte van 16.3% in de controlegroep; RR 0,87 95% CI 0,76-0,99). Er werd ook een klein en niet statistisch significant voordeel op de mortaliteit in de groep patiënten die zonder extra zuurstofbehoefte werd opgenomen in het ziekenhuis (2,9% overleed in de groep met remdesivir ten opzichte van 3,8% in de controlegroep; RR 0,76 95% CI 0,46-1,28. De mogelijke voordelen van remdesivir die in deze eindresultaten beschreven worden zijn klein. Omdat dit verschil minder was dan de vooraf gedefinieerde grens van klinische relevantie (3% punten verschil), wijzigt dit resultaat niet onze conclusie. Een publicatie van Ali (2022) beschrijft ook een mogelijk lagere mortaliteit bij opgenomen patienten met COVID-19 na behandeling met remdesivir. Dit verschil was niet statistisch significant. Omdat een groot deel van deze patiënten reeds beschreven werd in de Solidarity trial, verandert ook deze studie onze conclusie niet.

Overige uitkomstmaten

De gevonden studies tonen geen consistent positief klinisch effect van remdesivir op duur van ziekenhuisopname of andere uitkomstmaten, bewijskracht laag.

Wel liet de studie van Beigel (2020) zien dat de kans op het starten van beademing of andere vormen van invasieve respiratoire ondersteuning lager was in de remdesivir groep vergeleken met placebo. Ook toonde deze studie een significant sneller klinisch herstel en een kortere opnameduur van 5 dagen in het voordeel van remdesivir. Een voordeel dat ook bij een kleine RCT uit Egypte werd gezien: mediaan 10 dagen bij remdesivir en 16 dagen bij de standaard behandeling (Abd-Elsalam, 2021). Deze RCT is gepubliceerd na het voltooien van het literatuuronderzoek en inmiddels alweer teruggetrokken door het tijdschrift (Abd-Elsalam S. Retraction Notice, 2022). Alle andere studies lieten een dergelijk voordeel niet consistent zien. Een subgroep analyse van de studie van Spinner (2020) bij mensen nog vroeg in het beloop van de ziekte, werd dit positieve effect ook niet gezien: geen statistisch significante kans op een verbetering van de kliniek gezien bij behandeling binnen 9 dagen na ontstaan van symptomen.

Antivirale werking

In vitro en op basis van dieronderzoek waren er aanwijzingen voor een antiviraal effect van remdesivir bij COVID-19. Echter, dit effect werd in een drietal klinisch studies niet aangetoond. De meeste data over effecten op de virale load is afkomstig uit de DisCoVeRy studie (Ader, 2021), waarin bij 677 patiënten op enig moment in hun ziektebeloop een of meerdere nasofarynx monsters werden afgenomen. Behandeling met remdesivir liet ten opzichte van standaard zorg geen verschil zien in daling van de mediane viral load van dag 0 tot dag 3, en ook verder in het beloop (na 15 en 29 dagen) werden er geen verschillen in viral load waargenomen. Subgroep analyses van patiënten vroeg in hun ziektebeloop of met milde of matige ziekte lieten ook geen klinisch relevant antiviraal effect zien. De kleinere studie van Barratt-Due (2021) (n=36 met remdesivir en n=53 met standaardbehandeling) toonde ook geen significante daling in viral load in nasopharynx swabs in eerste 15 dagen na randomisatie (daily viral decrease rate 0.113; 95% CI -0.001-0.227). En Wang (2020) liet ook geen significant verschil zien in de afname van de viral load in de nasopharynx of oropharynx.

Conclusie

Uit de geïncludeerde RCTs blijkt dat er geen klinisch relevant verschil te zien is in de mortaliteit van opgenomen patiënten. De eindresultaten van de Solidarity trial (WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium, 2022) veranderen deze conclusie niet. Bij andere eindpunten (met name opnameduur) zijn er wel verschillen te zien met mogelijke klinische relevantie die door de toediening van remdesivir verklaard zouden kunnen worden. Klinische verbetering lijkt vooral sneller op te treden indien behandeling gestart wordt binnen 10 dagen na aanvang van symptomen bij patiënten met extra zuurstofbehoefte maar zonder indicatie voor (non)invasieve beademing. Deze voordelen worden met name in 1 studie waargenomen (Beigel, 2020). Deze studie werd verricht in een periode waarin corticosteroïd gebruik niet standaard gegeven werd. Of er een aanvullend effect aanwezig is, boven op de huidige standaard behandeling die nu corticosteroïden bevat, is hierdoor onduidelijk. Informatie uit de studie van Wang (2020), Ader (2021) en Barrett-Due (2021) tonen daarnaast geen klinisch relevante antivirale werking aan bij patiënten met zuurstofbehoefte. Het ontbreken van een effect op de virale klaring ontkracht het werkingsmechanisme van remdesivir. Alle bovenstaande redenen bijeengenomen maken dat er geen plaats meer is voor remdesivir in de standaard zorg van patiënten met COVID-19 in Nederland.

Overige overwegingen

In de context

Ook een Cochrane review trekt deze zelfde conclusie en stelt dat er matig-sterk bewijs is dat remdesivir een klein of geen effect heeft op de mortaliteit na 28 dagen (Ansems, 2021). Een mogelijk positief effect van remdesivir bij mensen met een beperkte zuurstofbehoefte wordt wel benoemd. In deze Cochrane review is de DisCoVeRy studie (Ader, 2021) nog niet meegenomen.

De WHO raadt in december 2021 - in tegenstelling tot de IDSA - het gebruik van remdesivir af bij opgenomen patiënten met COVID-19 in alle ziektestadia buiten studieverband (‘weak or conditional recommendation against the use of remdesivir in hospitalised patients with COVID-19’). Dit is een zwakke/voorwaardelijke aanbeveling. Er is daarbij gebruik gemaakt van precies dezelfde gepubliceerde data die in deze richtlijn ook zijn gebruikt, met uitzondering van de DisCoVeRy studie die later is verschenen.

De IDSA richtlijn adviseert in december 2021 behandeling met remdesivir nog wel bij patiënten met zuurstofbehoefte zonder mechanische ventilatie. Ook in dit advies is de meest recente DisCoVeRy studie nog niet meegenomen.

Bijwerkingen

Veiligheidsdata uit fase 1-onderzoek zijn nog niet gepubliceerd, ondanks dat er meerdere fase-1 onderzoeken zijn verricht. Vooral ALAT en ASAT-stijging wordt genoemd als bijwerking in de SmPC (https://lci.rivm.nl/remdesivir). De EMA onderzoekt sinds 2020 of er een verhoogd risico is op nefrotoxiciteit bij gebruik van remdesivir naar aanleiding van berichten hierover bij patiënten met COVID-19 die remdesivir toegediend kregen.

In meerdere studies werd veiligheidsdata verzamelend (Spinner, Wang, Ader, Barratt-Due). De DisCoVeRy studie van Ader (2020) onderzocht de veiligheid van remdesivir in 824 patiënten, waarbij er een vergelijkbaar aantal bijwerkingen werd gezien in de remdesivir groep ten opzichte van de controlegroep (32% versus 31% graad 3 of 4 bijwerkingen). Ook voor ernstige bijwerkingen was dit aantal nagenoeg gelijk. De studies van Spinner en Wang bevestigden deze data en lieten niet significant meer bijwerkingen zien bij het gebruik van remdesivir. In de studie van Barratt-Due werden bijwerkingen bij 42 patiënten met remdesivir bijgehouden. In deze kleine groep werden wat meer bijwerkingen gezien bij remdesivir (38.5% versus 25.3%), deze waren met name respiratoir van aard.

Samenvattend lijkt het gebruik van remdesivir niet gepaard te gaan met veel bijwerkingen.

Andere patiëntengroepen

Ook bij patiënten die niet zijn opgenomen in het ziekenhuis is remdesivir onderzocht (Gottlieb, 2022). In een groep van 562 ambulante patiënten met een hoog risico op een ernstig beloop toonde intraveneus toegediend remdesivir een voordeel: de kans op opname of overlijden binnen 28 dagen was 0,7% in de remdesivir groep versus 5,3% in de controle groep (hazard ratio 0,13 (95% CI 0,03-0,59)). Remdesivir werd in deze studie gedurende 3 opeenvolgende dagen intraveneus toegediend. Dit beperkt de praktische toepasbaarheid. Dit middel wordt daarom op dit moment ook niet aanbevolen in de ambulante setting. Onderzoek naar andere toedieningsvormen van remdesivir wordt op dit moment verricht.

Of het klinisch relevante effect van remdesivir ook ontbreekt in specifieke patiëntengroepen, zoals patiënten met een verminderd afweersysteem of heel vroeg in het ziektebeloop, is niet onderzocht. Hierover kan dan ook geen advies gegeven worden.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Remdesivir wordt niet (meer) aanbevolen bij de behandeling van COVID-19, de kosten zullen hier daarom niet beschreven worden.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Remdesivir wordt niet (meer) aanbevolen bij de behandeling van COVID-19, dus implementatie is niet van toepassing.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Er werd geen klinisch relevant effect gevonden bij opgenomen patiënten die remdesivir kregen ten opzichte van de controle groepen. De bijwerkingen zijn nog beperkt onderzocht. Omdat het middel niet (meer) wordt voorgeschreven in het kader van de standaardbehandeling van COVID-19, zijn er geen specifieke voorkeuren of waarden beschreven van patiënten.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Van behandeling van opgenomen patiënten met remdesivir is geen winst op harde eindpunten zoals mortaliteit aangetoond. Slechts in enkele studies wordt er op andere eindpunten of in subgroepen een beperkt verschil gezien met mogelijk beperkte klinische relevantie in het voordeel van remdesivir. Hiertegenover staat de observatie van (mogelijke) bijwerkingen en kosten. Op basis hiervan kan geconcludeerd worden dat remdesivir geen plaats heeft bij de standaardbehandeling van COVID-19.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Remdesivir (GS-5734) is een nucleoside-analoog (prodrug) met in vitro activiteit tegen verschillende RNA-virussen. Het werd eerder getest als antiviraal middel voor behandeling van Ebola infecties (Warren, 2016), maar bleek niet voldoende klinisch effectief. Remdesivir heeft bij in-vitro onderzoek met onder meer humane longcellijnen activiteit tegen verschillende coronavirussen, onder meer SARS-CoV-1 laten zien (Sheahan, 2017). Voor SARS-CoV-2 is in vitro (Vero E6; niercellijn afkomstig van groene meerapen) antivirale activiteit gezien (Wang M, 2020). In beide studies ligt de EC50 bij lage micromolaire concentraties. Echter het is onduidelijk de of de gebruikte modellen en concentraties representatief zijn voor een infectie bij mensen in de longen. Tevens ontbreken validatie studies. Een studie met MERS-CoV infectie bij muizen lieten een antiviraal effect en minder orgaanschade van remdesivir zien (Sheahan, 2020). Toediening van remdesivir bij resusapen, 12 uur na blootstelling aan SARS-CoV-2, bleek te leiden tot minder longontsteking en een lagere hoeveelheid virus in de longen (Williamson, 2020).

Deze data leidden er toe dat remdesivir al vanaf het begin van de pandemie onderzocht werd voor behandeling van COVID-19. Echter zijn er nooit klinische dose-finding studies gedaan. Inmiddels is in diverse gerandomiseerde gecontroleerde studies (RCT’s) de effectiviteit onderzocht om de plaats van remdesivir bij de behandeling van COVID-19 patiënten te bepalen.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Mortality (crucial)

|

Moderate GRADE |

Treatment with remdesivir probably results in little to no difference in mortality when compared with treatment without remdesivir in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Sources: Ader, 2021; Beigel, 2020; Mahajan, 2021; Pan, 2020; Spinner, 2020; Wang, 2020 |

Extensive respiratory support (crucial)

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with remdesivir may result in little to no difference in the need for extensive respiratory support when compared with treatment without remdesivir in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Sources: Barratt-Due, 2021; Beigel, 2020; Pan, 2020 |

Duration of hospitalization (important)

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with remdesivir may result in little to no difference in the length of stay when compared with treatment without remdesivir in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Sources: Ader, 2021; Beigel, 2020; Pan, 2020; Wang, 2020 |

Time to clinical improvement (important)

|

Treatment with remdesivir may result in little to no difference in the time to clinical improvement when compared with treatment without remdesivir in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Sources: Ader, 2021; Beigel, 2020; Spinner, 2021; Wang, 2020 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Ader (2021) (The DisCoVeRy trial) describes a phase 3, open-label, adaptive multicenter randomized controlled trial. This study evaluated the clinical efficacy of remdesivir in addition to standard of care versus standard of care alone in patients admitted to the hospital with COVID-19 with indication of oxygen or ventilation support. Standard of care included anticoagulants and corticosteroids as of a certain time point. Critically ill patients that required intensive care unit admission received 20 mg dexamethasone once daily for 5 days, followed by 10 mg once daily for 5 days at the clinician’s discretion. In total, 40% of the patients received systemic corticosteroids and 7.5% corticosteroids via the inhaled route. Other supportive treatments, such as immunomodulatory agents were given at the investigator’s discretion. None of the participants received a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine during the trial. The intervention group (n=429) received a remdesivir (200 mg loading dose on day 1, followed by 100 mg daily for up to 9 additional days) in addition to standard care. The control group (n=428) received standard of care alone. The length of follow-up was 29 days. The following relevant outcome measures were included: mortality, duration of hospitalization, clinical improvement. The primary outcome was the clinical status at day 15 measured by the WHO seven-point ordinal scale. The difference in clinical status at day 15 between the treatment groups was not statistically significant.

Barratt-Due (2021) (The NOR-Solidarity trial) described an open-label adaptive randomized controlled trial. This was an independent add-on randomized controlled trial to the WHO Solitarity trial (Pan, 2020). Barratt-Due (2021) evaluated the effects of remdesivir in hospitalized adult patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection. The ‘disease severity’ of the patients was not reported based on the requirement of respiratory support but on viral load. The intervention group (n=42) received remdesivir (200 mg loading dose on day 1, followed by 100 mg daily for up to 9 additional days) in addition to standard care. The control group (n=57) received standard of care alone. Standard of care changed during the study as a result of the recovery trial and updated WHO guidelines recommending systemic steroids for severe and critical COVID-19. In total, 2.4% of the patients in the intervention group received steroids, versus 1.8% in the control group. The length of follow-up was three months. The following relevant outcome measures were included: respiratory support. The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. This outcome measure was also included in the WHO Solidarity trial (Pan, 2020). In total, 7.1% (95%CI 1.8 to 17.5) of the patients in the intervention group died during hospitalization, versus 7.0% (95%CI 2.2 versus 15.6) in the control group. No significant differences were seen between the treatment groups in mortality during hospitalization.

Beigel (2020) (The Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial (ACTT-1)) described a double-blind, multicenter randomized, placebo-controlled trial of intravenous remdesivir in adults who were hospitalized with COVID-19 and had evidence of lower respiratory tract infection. Most patients had either one (25.9%) or two or more (54.5%) of the prespecified coexisting conditions at enrolment, most commonly hypertension (50.2%), obesity (44.8%), and type 2 diabetes mellitus (30.3%). Of all patients, 903 (85.0%) were in the moderate-to-severe disease stratum (requiring invasive or non-invasive mechanical ventilation, or requiring supplemental oxygen, or an SpO2 ≤ 94.0% on room air, or tachypnea (respiratory rate ≥ 24 breaths per minute)) and 159 (15.0%) were categorized as having mild disease (SpO2 > 94.0% and respiratory rate < 24 breaths per minute without supplemental oxygen requirement). The intervention group (n=541) received remdesivir (200 mg loading dose on day 1, followed by 100 mg daily for up to 9 additional days). The control group (n=521) received placebo for up to 10 days. All patients received supportive care according to the standard of care for the trial site hospital. In total, the patients received a variety of concomitant treatments during the study course: 82.3% received antibiotics, 32.2% received vasopressors, 23.0% received corticosteroids, 7.5% received other anti-inflammatory medications (not specified), 4.8% received monoclonal antibodies targeting cytokines. The length of follow-up was 28 days. The following relevant outcome measures were included: mortality, respiratory support, duration of hospitalization, clinical improvement. The primary outcome was time to recovery, defined by either discharge from the hospital or hospitalization for infection-control purposes only. Those who received remdesivir had a significantly shorter median recovery time of 10 days, as compared with 15 days among those who received placebo.

Mahajan (2021) described a randomized controlled trial which evaluated the improvement in clinical outcomes with remdesivir treatment for five days in hospitalized patients who were between 18 and 60 years and had COVID-19 confirmed by PCR assay within the last 4 days. Patients on mechanical ventilation were excluded. The intervention group (n=34) received remdesivir (200 mg loading dose on day 1, followed by 100 mg daily for up to 4 additional days) plus the standard of care. The control group (n=36) received standard care alone. Drugs like corticosteroids and heparin were given as per standard care protocol (exact percentage not mentioned). Standard of care was not further specified in this study. The length of follow-up was 12 days or until discharge/death. The following relevant outcome measure was included: mortality. The primary outcome is the clinical status. Both groups had similar outcomes after adjustment for baseline clinical status.

Pan (2020) (The WHO Solidarity trial) descripted an open-label randomized controlled trial. Pan (2020) compared the efficacy of the addition of remdesivir to standard of care in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. The study included patients who were aged 18 years or older, diagnosed with COVID-19, not known with receiving any trial drug, not expected to be transferred elsewhere within 72 hours, and hand no contraindication to any trial drug. The intervention group (n=2743) received remdesivir (200 mg loading dose on day 1, followed by 100 mg daily for up to 9 additional days) in addition to standard care. The control group (n=2708) received local standard of care alone. In total, the patients received several concomitant drugs during the study course: corticosteroids (intervention group 47.8%, control group 47.6%), convalescent plasma (intervention group 1.9%, control group 2.1%), anti-IL-6 drug (intervention group 4.9%, control group 5.3%). The length of follow-up was 28 days or up to discharge. The following relevant outcome measures were included: mortality, respiratory support, and duration of hospitalization. The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. Remdesivir did not reduce mortality, overall or in subgroup analyses.

Spinner (2020) describes a randomized open-label multicentre clinical trial of intravenous remdesivir in adults who were hospitalized with COVID-19. The intervention group (n=384) received remdesivir (200 mg loading dose on day 1, followed by 100 mg daily). Remdesivir was provided for either 5 days (intervention group 1, n=193) or 10 days (intervention group 2, n=191). The control group (n=200) received standard of care. Standard of care included steroids in 15-19% of the patients. The original protocol allowed use of other agents with presumptive activity against SARS-CoV-2 if such use was local standard care. This exception was disallowed in a subsequent amendment of the protocol. The length of follow-up was 28 days. The following relevant outcome measures were included: mortality, clinical improvement. The primary outcome was clinical status on day 11 on a 7-point ordinal scale. On day 11, patients in the 5-day remdesivir group had statistically significantly higher odds of a better clinical status distribution than those receiving standard care. The clinical status distribution on day 11 between the 10-day remdesivir and standard care groups was not significantly different.

Wang (2020) describes a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial of intravenous remdesivir in adults who were hospitalized with COVID-19. Almost all patients required a form of supplemental oxygen (supplemental oxygen, high-flow nasal cannula, non-invasive mechanical ventilation, ECMO or invasive mechanical ventilation) at day 1, except 3/78 (3.8%) of patients in the control group. The intervention group (n=158) received remdesivir (200 mg loading dose on day 1, followed by 100 mg daily for up to 9 additional days). The control group (n=78) received a placebo for up to 10 days. Patients received several concomitant drugs during the study course: corticosteroids (intervention group 65%, control group 68%), antibiotics (intervention group 90%, control group 94%), interferon alfa-2b (intervention group 29%, control group 38%), lopinavir-ritonavir (intervention group 28%, control group 29%), and vasopressors (intervention group 16%, control group 17%). The length of follow-up was 28 days. The following relevant outcome measures were included: mortality, duration of hospitalization, clinical improvement. The primary outcome was time to clinical improvement up to day 28, defined as the time (in days) from randomization to the point of a decline of two levels on a six-point ordinal scale of clinical status or discharged alive from hospital, whichever came first. Remdesivir was not associated with a difference in time to clinical improvement.

Table 1. Overview of RCTs comparing remdesivir with standard care in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

|

Author |

Disease severity, based on need for respiratory support* |

Sample size |

Dosage |

|

Ader (2021) |

Mixed: Mild: n=12 (1%) Moderate: n=492 (59%) Severe: n=326 (40%) |

I: N=429 C: N=428 Total: N=857 |

- 200 mg remdesivir intravenously on day 1. - 100 mg once-daily (on days 2-10) |

|

Barratt-Due (2021) |

Mixed: Disease severity is defined based on viral load.

|

I: 42 C: 57 Total: 99 |

- 200 mg remdesivir intravenously (on day 0). - 100 mg once-daily (on days 1-9). |

|

Beigel (2020) |

Mixed: Mild: n=138 (13%) Moderate: n=435 (41%) Severe: n=478 (45%)

Baseline score was missing in 1% of the patients). |

I: 541 C: 521 Total: 1062 |

- 200 mg remdesivir intravenously (on day 1). - 100 mg once-daily (on days 2-10). |

|

Mahajan (2021) |

Mixed: Mild: 0 Moderate: n=53 (75.7%) Severe: n=17 (24.3%) mostly moderate receiving low flow supplemental oxygen (76%), severe cases received non-invasive ventilation or high-flow oxygen. |

I: 34 C: 36 Total: 70 |

- 200 mg remdesivir intravenously (on day 1). - 100 mg once-daily (on days 2-5). |

|

Pan (2020) |

Mixed: Mild: n= 1325 (24.3%), moderate & severe: n= 4126 (75.7%) |

I: N=2743 C: N=2708 Total: N=5451 |

- 200 mg remdesivir intravenously (on day 0). - 100 mg once-daily (on days 1-9). |

|

Spinner (2020) |

Mixed: Mild: n=491 (84%), Moderate: n=88 (15%) Severe: n=5 (1%) |

I1 (5-day remdesivir): 193 I2 (10-day remdesivir): 191 C: 200 Total: N=584 |

- 200 mg remdesivir intravenously (on day 1). - 100 mg once-daily (on days 2-5 or 2-10). |

|

Wang (2020) |

Mixed: mild: n=3 (1%) moderate: n =194 (82%) severe: n=38 (16%)

1 patient in the remdesivir group died at day 1 |

I: N=158 C: N=78 Total: N=236 |

- 200 mg remdesivir intravenously (on day 1). - 100 mg once-daily (on days 2-10). |

*Disease severity categories:

- mild disease (no supplemental oxygen);

- moderate disease (supplemental oxygen: low flow oxygen, non-rebreathing mask);

- severe disease (supplemental oxygen: high flow oxygen [high flow nasal cannula (HFNC)/Optiflow], continuous positive airway pressure [CPAP], non-invasive ventilation [NIV], mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [ECMO or ECLS]).

N: Total sample size

I: Intervention

C: Control

Results

Mortality (crucial)

Mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 was reported in six studies (Ader, 2021; Beigel, 2020; Mahajan, 2021; Pan, 2020; Spinner, 2020; Wang, 2020). The results are presented separately for a follow-up of 28-30 days and other length of follow-up. Barratt-Due (2020) reported mortality, however as these patients were already included in the WHO Solidarity trial (Pan, 2020). To prevent double representation, these results were not included in the meta-analysis.

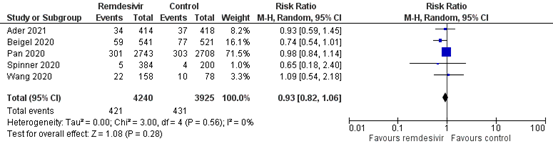

Mortality, 28-30 days

The pooled incidence of mortality in hospitalized patients in the intervention group was 421/4240 (9.9%), compared to 431/3925 (11.0%) in the control group. The pooled RR was 0.93 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.06; Figure 1), in favour of the intervention group. The pooled RD was 0.01 (95%CI -0.01 to 0.02), in favour of the intervention group. This is not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 1: Mortality (28-30days) in hospitalized patients

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

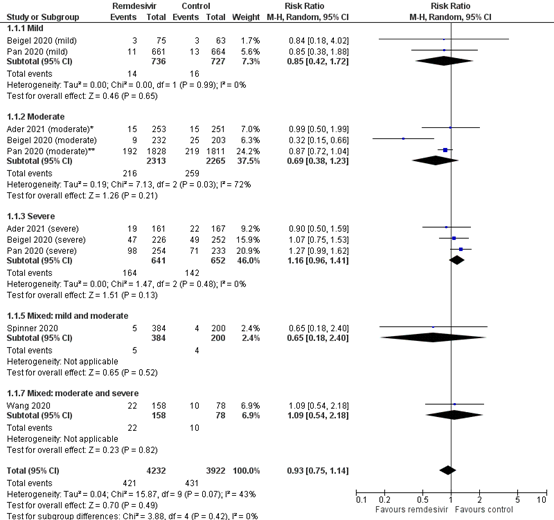

Subgroup analysis according to disease severity

Mild disease

Two studies reported the mortality specifically for patients with a mild disease severity (Beigel, 2020; Pan, 2020). The mortality was 14/736 (1.9%) in the intervention group, compared to 16/727 (2.3%) in the control group (Figure 2). The pooled RR was 0.85 (95% CI 0.42 to 1.72), in favour of the intervention group. The pooled RD was 0.00 (95% CI -0.02 to 0.01). This is not considered clinically relevant.

Moderate disease

Three studies reported the mortality for patients with a moderate disease severity (Ader, 2021; Beigel, 2020; Pan, 2020). The mortality in the intervention group was 216/2313 (9.3%), compared to 259/2265 (11.4%) in the control group (Figure 2). The RR was 0.69 (95%CI 0.38 to 1.23) in favour of the intervention group. The RD was just below 0.03 (95%CI -0.01 to 0.07), in favour of the intervention group. This is considered clinically relevant.

Severe disease

Two studies reported the mortality for patients with a severe disease severity (Ader, 2021; Beigel, 2020). The mortality was 164/641 (25.6%) in the intervention group, compared to 142/652 (21.8%) in the control group (Figure 2). The pooled RR was 1.16 (95% CI 0.96 to 1.41), in favour of the control group. The RD was 0.02 (95% CI -0.03 to 0.08). This is not considered clinically relevant.

Mixed: mild & moderate disease

Spinner (2020) reported the mortality for patients with a mild and moderate disease severity. The mortality in the intervention group was 5/384 (1.3%), compared to 4/200 (2.0%) in the control group (Figure 2). The RR was 0.65 (95% CI 0.18 to 2.40) in favour of the intervention group. The RD was 0.01 (95% CI -0.02 to 0.03). This is not considered clinically relevant.

Mixed: moderate & severe disease

Wang (2020) reported the mortality for patients with a moderate and severe disease severity. The mortality in the intervention group was 22/158 (13.9%), compared to 10/78 (12.8%) in the control group (Figure 2). The RR was 1.09 (95% CI 0.54 to 2.18) in favour of the intervention group. The RD was 0.01 (95% CI -0.01 to 0.02). This is not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 2: Mortality (28-30days) in hospitalized patients by disease severity

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval. *1% of the patients in the study of Ader (2021) had a mild disease severity. **Pan (2020) included patients who received high-flow oxygen in the moderate subgroup.

Mortality, other follow-up

Mahajan (2021) reported mortality during the 12-day follow up. The mortality was the 14.7% (5/34) in the intervention group, and 8.3% (3/36) in the control group (RR 1.76; 95%CI 0.46 to 6.82). The RD was 0.06 (95%CI -0.09 to 0.21), in favour of the control group. This means that patients in the intervention group have a higher risk of mortality. This is considered clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence started as high, because the studies were RCTs. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because there is a difference in effect estimates among the studies due to heterogeneity in study population (inconsistency, -1). The level of evidence for the outcome mortality in hospitalized patients is considered moderate.

Extensive respiratory support (crucial)

Initiation of mechanical respiratory support in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 was reported in two studies (Beigel, 2020; Pan, 2020). The results were not pooled as only two studies could be included in the meta-analysis. Ader (2021) reported a combined outcome measure new mechanical ventilation, ECMO or death within 29 days and was therefore not included in the meta-analysis. Barratt-Due (2020) reported the initiation of mechanical respiratory support, however as these patients were already included in the WHO Solidarity trial (Pan, 2020), the results were not included in the meta-analysis.

Pan (2020) reported 295/2743 (10.8%) patients in the intervention group in whom respiratory support was initiated after randomization, compared to 284/2709 (10.5%) in the control group. This results in a RR of 1.03 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.20). The RD was 0.00 (95%CI -0.01 to 0.02). This means that there is no difference between the intervention and control group. Ventilation included invasive or non-invasive mechanical ventilation or extra-corporal membrane oxygenation.

Beigel (2020) reported that the number of patients that started non-invasive ventilation or high-flow oxygen during the study was 52/307 (16.9%) in the intervention group, compared to 64/266 (24.16%) in the placebo group. This results in a RR of 0.70 (95% CI 0.51 to 0.98), in favour of the intervention group. The RD was 0.07 (95%CI 0.00 to 0.14), in favour of the intervention group. This is considered clinically relevant. It is unclear whether these patients also started mechanical ventilation or ECMO during the study period.

Beigel (2020) also reported that the number of patients that started using mechanical ventilation or ECMO during the study was 52/402 (12.9%) in the intervention group, compared to 82/364 (22.5%) in the placebo group. This results in a RR of 0.57 (95% CI 0.42 to 0.79). The RD was 0.10 (95%CI 0.04 to 0.15), in favour of the intervention group. This is considered clinically relevant. It is unclear whether these patients also received non-invasive ventilation or high-flow oxygen before the start of mechanical ventilation or ECMO.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence started as high, because the studies were RCTs. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of heterogeneity in study results (inconsistency, -1) and because of a low number of events (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence for the outcome ‘respiratory support’ in hospitalized patients is considered low.

Duration of hospitalization (important)

Duration of hospitalization in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 was reported in three studies (Ader, 2021; Beigel, 2020; Wang, 2020). Due to differences in reporting, data were not pooled. Pan (2020) did not report the duration of hospitalization, but they rather reported the percentage at 7, 14 and 21 days. Therefore, the study was not included.

Ader (2021) reported that the median (IQR) number of days until hospital discharge within 29 days was 15 days (10 to 29) in the intervention group (n=253), compared to 13 days (8 to 29) in the control group (n=251). The difference was 2 days, this is not considered clinically relevant.

Beigel (2020) reported that the median (IQR) duration of initial hospitalization was 12 days (6 to 28) in the intervention group (n=541), compared to 17 days (8 to 28) in the control group. The median duration of initial hospitalization among those who did not die was 10 days (5 to 21) in the intervention group, and 14 days (7 to 27) in the control group. The difference is 5 or 4 days, which was both considered clinically relevant.

Wang (2020) reported that the median (IQR) duration of hospital stay was 25 days (16 to 38) in the intervention group (n=158), compared to 24 days (18 to 36) in the control group. The difference is 1 day, this is not considered clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence started as high, because the studies were RCTs. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because the studies were either not blinded or because of high numbers lost to follow-up (risk of bias, -1) and variance of point estimates across studies (inconsistency, -1). The level of evidence for the outcome ‘duration of hospitalization’ is considered low.

Time to clinical improvement (important)

Time to clinical improvement was reported in four studies for hospitalized patients with COVID-19 (Ader, 2021; Beigel, 2020; Spinner, 2021; Wang, 2020). Due to differences in reporting, data were not pooled.

Ader (2021) reported that the median (IQR) days to NEWS-2 of 2 or lower or hospital discharge within 29 days was 9 days (5 to 14) in the intervention group (n=253), compared to 8 days (5 to 13) in the control group (n=251). The difference is 1 day, in favour of the control group. In addition, they reported that the median (IQR) time to improvement of two categories of the 7-point ordinal scale or hospital discharge within day 29 was 11 days (8 to 20) in the intervention group, compared to 9 days (6 to 15) in the control group. The difference is 2 days, in favour of the control group. This is not considered clinically relevant.

Beigel (2020) reported that the median time (95% CI) to discharge or NEWS ≤2 for 24 hours was 8 days (7 to 9) in the intervention group (n=541), compared to 12 days (10 to 15) in the control group (n=521). The difference was 4 days, in favour of the intervention group. This is considered clinically relevant.

Spinner (2021) reported the number of patients who showed clinical improvement at day 28. Clinical improvement was defined as an improvement of at least 2 points from baseline on the 7-point ordinal scale. Spinner (2021) reported that 345 (89.8%) of the patients in the intervention group (n=384) showed clinical improvement, compared to 166 (83.0%) of the control group (n=200). This results in a RR of 1.08 (95%CI 1.01 to 1.16). The RD is 0.07 (95%CI 0.01 to 0.13) in favour of the intervention group. This is considered clinically relevant.

Wang (2020) reported the median time to clinical improvement defined as a two-point reduction in patient’s admission status on a six-point ordinal scale, or live discharge from the hospital, whichever came first. The intervention group (n=158) had a median (IQR) time to improvement of 21 days (13 to 28 days), compared to 23 days (15 to 28) in the control group (n=78). The difference is 2 days, in favour of the intervention group. This is not considered clinically relevant.

Ader (2021) reported that the median (IQR) days to NEWS-2 of 2 or lower or hospital discharge within 29 days was 20 days (12 to 29) in the intervention group (n=161), compared to 26 days (12 to 29) in the control group (n=167). The difference is 6 days, in favour of the intervention group. The difference is considered clinically relevant. In addition, they reported that the median (IQR) time to improvement of two categories of the 7-point ordinal scale or hospital discharge within day 29 was 16 days (10 to 29) in the intervention group, compared to 17 days (10 to 29) in the control group. The difference is 1 day, in favour of the intervention group. This is not considered clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence started as high, because the studies were RCTs. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of the studies were not blinded (risk of bias, -1), heterogeneity in reporting ‘clinical improvement’ and variance of point estimates across studies (inconsistency, -1). The level of evidence for the outcome ‘time to clinical improvement’ is considered low.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effectivity of treatment with remdesivir compared to treatment without remdesivir in patients with COVID-19?

P: hospitalized with COVID-19 (subgroups mild, moderate, severe)

I: remdesivir + standard care

C: standard care only / placebo treatment + standard care

O: 28-30 day mortality (if not available, any other reports of mortality), extensive respiratory support, duration of hospitalization, time to clinical improvement

Relevant outcome measures

For hospitalized COVID-19 patients, mortality and need for extensive respiratory support were considered as crucial outcome measures for decision making. Duration of hospitalization and time to clinical improvement were considered as important outcome measures for decision making.

Extensive respiratory support was defined as high flow nasal cannula (HFNC)/Optiflow, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), non-invasive ventilation (NIV), mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO or ECLS).

The working group defined 3% points absolute difference as a minimal clinically important difference for mortality (resulting in a NNT of 33), 3 days difference for duration of hospitalization and time to clinical improvement, 5% points absolute difference need for respiratory support and ICU admission (resulting in a NNT of 20).

Studies of hospitalized patients were categorized on based on the respiratory support that was needed at baseline (preferably based on patient inclusion/exclusion criteria; otherwise on baseline characteristics). The following categories were used:

- mild disease (no supplemental oxygen);

- moderate disease (supplemental oxygen: low flow oxygen, non-rebreathing mask);

- severe disease (supplemental oxygen: high flow oxygen [high flow nasal cannula (HFNC)/Optiflow], continuous positive airway pressure [CPAP], non-invasive ventilation [NIV], mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [ECMO or ECLS]).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 14 October 2021. The detailed search strategy is outlined under the tab Methods. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: randomized controlled trial, peer reviewed and published in indexed journal, comparing treatment with remdesivir and standard care to standard care alone or treatment remdesivir and standard care to placebo and standard care in patients with COVID-19.

The systematic literature search resulted in 77.987 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic review or randomized controlled trials. Eventually, seven studies were included.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were conducted using Review Manager (RevMan) software 5.4. For dichotomous outcomes, Mantel Haenszel random‐effects risk ratios (RRs) and risk differences (RDs) were calculated. For continuous outcomes, a random‐effects mean difference (MD) weighted by the inverse variance was calculated. The random-effects model estimates the mean of a distribution of effects.

Results

In total, seven RCTs were included in the analysis. Important study characteristics and results are summarized below. Studies are presented in alphabetical order, only results of the primary outcome is reported in the summary of literature. Additionally, studies are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized separately in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Abd-Elsalam S, Ahmed OA, Mansour NO, Abdelaziz DH, Salama M, Fouad MHA, Soliman S, Naguib AM, Hantera MS, Ibrahim IS, Torky M, Dabbous HM, El Ghafar MSA, Abdul-Baki EAM, Elhendawy M. Remdesivir Efficacy in COVID-19 Treatment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021 Sep 10:tpmd210606. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.21-0606. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34649223.

- Abd-Elsalam S. Retraction Notice. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2022 Sep 2;107(3):1. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1073ret. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36099166; PMCID: PMC9490653.

- Ader F, Bouscambert-Duchamp M, Hites M, Peiffer-Smadja N, Poissy J, Belhadi D, Diallo A, Lê MP, Peytavin G, Staub T, Greil R, Guedj J, Paiva JA, Costagliola D, Yazdanpanah Y, Burdet C, Mentré F; DisCoVeRy Study Group. Remdesivir plus standard of care versus standard of care alone for the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (DisCoVeRy): a phase 3, randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 Sep 14:S1473-3099(21)00485-0. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00485-0. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34534511; PMCID: PMC8439621.

- Ali, K., Azher, T., Baqi, M., Binnie, A., Borgia, S., Carrier, F. M., Cavayas, Y. A., Chagnon, N., Cheng, M. P., Conly, J., Costiniuk, C., Daley, P., Daneman, N., Douglas, J., Downey, C., Duan, E., Duceppe, E., Durand, M., English, S., Farjou, G., … Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada (AMMI) Clinical Research Network and the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group (2022). Remdesivir for the treatment of patients in hospital with COVID-19 in Canada: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne, 194(7), E242–E251. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.211698

- Ansems K, Grundeis F, Dahms K, Mikolajewska A, Thieme V, Piechotta V, Metzendorf MI, Stegemann M, Benstoem C, Fichtner F. Remdesivir for the treatment of COVID-19. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Aug 5;8(8):CD014962. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD014962. PMID: 34350582; PMCID: PMC8406992.

- Barratt-Due A, Olsen IC, Nezvalova-Henriksen K, Kåsine T, Lund-Johansen F, Hoel H, Holten AR, Tveita A, Mathiessen A, Haugli M, Eiken R, Kildal AB, Berg Å, Johannessen A, Heggelund L, Dahl TB, Skåra KH, Mielnik P, Le LAK, Thoresen L, Ernst G, Hoff DAL, Skudal H, Kittang BR, Olsen RB, Tholin B, Ystrøm CM, Skei NV, Tran T, Dudman S, Andersen JT, Hannula R, Dalgard O, Finbråten AK, Tonby K, Blomberg B, Aballi S, Fladeby C, Steffensen A, Müller F, Dyrhol-Riise AM, Trøseid M, Aukrust P; NOR-Solidarity trial. Evaluation of the Effects of Remdesivir and Hydroxychloroquine on Viral Clearance in COVID-19 : A Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2021 Sep;174(9):1261-1269. doi: 10.7326/M21-0653. Epub 2021 Jul 13. PMID: 34251903; PMCID: PMC8279143.

- Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, Mehta AK, Zingman BS, Kalil AC, Hohmann E, Chu HY, Luetkemeyer A, Kline S, Lopez de Castilla D, Finberg RW, Dierberg K, Tapson V, Hsieh L, Patterson TF, Paredes R, Sweeney DA, Short WR, Touloumi G, Lye DC, Ohmagari N, Oh MD, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Benfield T, Fätkenheuer G, Kortepeter MG, Atmar RL, Creech CB, Lundgren J, Babiker AG, Pett S, Neaton JD, Burgess TH, Bonnett T, Green M, Makowski M, Osinusi A, Nayak S, Lane HC; ACTT-1 Study Group Members. Remdesivir for the Treatment of Covid-19 - Final Report. N Engl J Med. 2020 Nov 5;383(19):1813-1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764. Epub 2020 Oct 8. PMID: 32445440; PMCID: PMC7262788.

- Gordon CJ, Tchesnokov EP, Woolner E, Perry JK, Feng JY, Porter DP, Götte M. Remdesivir is a direct-acting antiviral that inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 with high potency. J Biol Chem. 2020 May 15;295(20):6785-6797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.013679. Epub 2020 Apr 13. PMID: 32284326; PMCID: PMC7242698.

- Gottlieb RL, Vaca CE, Paredes R, Mera J, Webb BJ, Perez G, Oguchi G, Ryan P, Nielsen BU, Brown M, Hidalgo A, Sachdeva Y, Mittal S, Osiyemi O, Skarbinski J, Juneja K, Hyland RH, Osinusi A, Chen S, Camus G, Abdelghany M, Davies S, Behenna-Renton N, Duff F, Marty FM, Katz MJ, Ginde AA, Brown SM, Schiffer JT, Hill JA; GS-US-540-9012 (PINETREE) Investigators. Early Remdesivir to Prevent Progression to Severe Covid-19 in Outpatients. N Engl J Med. 2022 Jan 27;386(4):305-315. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116846. Epub 2021 Dec 22. PMID: 34937145; PMCID: PMC8757570.

- Mahajan L, Singh AP, Gifty. Clinical outcomes of using remdesivir in patients with moderate to severe COVID-19: A prospective randomised study. Indian J Anaesth. 2021 Mar;65(Suppl 1):S41-S46. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_149_21. Epub 2021 Mar 20. PMID: 33814589; PMCID: PMC7993042.

- Sheahan TP, Sims AC, Graham RL, Menachery VD, Gralinski LE, Case JB, Leist SR, Pyrc K, Feng JY, Trantcheva I, Bannister R, Park Y, Babusis D, Clarke MO, Mackman RL, Spahn JE, Palmiotti CA, Siegel D, Ray AS, Cihlar T, Jordan R, Denison MR, Baric RS. Broad-spectrum antiviral GS-5734 inhibits both epidemic and zoonotic coronaviruses. Sci Transl Med. 2017 Jun 28;9(396):eaal3653. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aal3653. PMID: 28659436; PMCID: PMC5567817.

- Spinner CD, Gottlieb RL, Criner GJ, Arribas López JR, Cattelan AM, Soriano Viladomiu A, Ogbuagu O, Malhotra P, Mullane KM, Castagna A, Chai LYA, Roestenberg M, Tsang OTY, Bernasconi E, Le Turnier P, Chang SC, SenGupta D, Hyland RH, Osinusi AO, Cao H, Blair C, Wang H, Gaggar A, Brainard DM, McPhail MJ, Bhagani S, Ahn MY, Sanyal AJ, Huhn G, Marty FM; GS-US-540-5774 Investigators. Effect of Remdesivir vs Standard Care on Clinical Status at 11 Days in Patients With Moderate COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020 Sep 15;324(11):1048-1057. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.16349. PMID: 32821939; PMCID: PMC7442954.

- Wang Y, Zhang D, Du G, Du R, Zhao J, Jin Y, Fu S, Gao L, Cheng Z, Lu Q, Hu Y, Luo G, Wang K, Lu Y, Li H, Wang S, Ruan S, Yang C, Mei C, Wang Y, Ding D, Wu F, Tang X, Ye X, Ye Y, Liu B, Yang J, Yin W, Wang A, Fan G, Zhou F, Liu Z, Gu X, Xu J, Shang L, Zhang Y, Cao L, Guo T, Wan Y, Qin H, Jiang Y, Jaki T, Hayden FG, Horby PW, Cao B, Wang C. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020 May 16;395(10236):1569-1578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9. Epub 2020 Apr 29. Erratum in: Lancet. 2020 May 30;395(10238):1694. PMID: 32423584; PMCID: PMC7190303.

- Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, Yang X, Liu J, Xu M, Shi Z, Hu Z, Zhong W, Xiao G. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020 Mar;30(3):269-271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. Epub 2020 Feb 4. PMID: 32020029; PMCID: PMC7054408.

- WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium, Pan H, Peto R, Henao-Restrepo AM, Preziosi MP, Sathiyamoorthy V, Abdool Karim Q, Alejandria MM, Hernández García C, Kieny MP, Malekzadeh R, Murthy S, Reddy KS, Roses Periago M, Abi Hanna P, Ader F, Al-Bader AM, Alhasawi A, Allum E, Alotaibi A, Alvarez-Moreno CA, Appadoo S, Asiri A, Aukrust P, Barratt-Due A, Bellani S, Branca M, Cappel-Porter HBC, Cerrato N, Chow TS, Como N, Eustace J, García PJ, Godbole S, Gotuzzo E, Griskevicius L, Hamra R, Hassan M, Hassany M, Hutton D, Irmansyah I, Jancoriene L, Kirwan J, Kumar S, Lennon P, Lopardo G, Lydon P, Magrini N, Maguire T, Manevska S, Manuel O, McGinty S, Medina MT, Mesa Rubio ML, Miranda-Montoya MC, Nel J, Nunes EP, Perola M, Portolés A, Rasmin MR, Raza A, Rees H, Reges PPS, Rogers CA, Salami K, Salvadori MI, Sinani N, Sterne JAC, Stevanovikj M, Tacconelli E, Tikkinen KAO, Trelle S, Zaid H, Røttingen JA, Swaminathan S. Repurposed Antiviral Drugs for Covid-19 - Interim WHO Solidarity Trial Results. N Engl J Med. 2021 Feb 11;384(6):497-511. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2023184. Epub 2020 Dec 2. PMID: 33264556; PMCID: PMC7727327.

- WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium. Remdesivir and three other drugs for hospitalised patients with COVID-19: final results of the WHO Solidarity randomised trial and updated meta-analyses. Lancet. 2022 May 21;399(10339):1941-1953. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00519-0. Epub 2022 May 2. PMID: 35512728; PMCID: PMC9060606.

- Williamson BN, Feldmann F, Schwarz B, Meade-White K, Porter DP, Schulz J, van Doremalen N, Leighton I, Yinda CK, Pérez-Pérez L, Okumura A, Lovaglio J, Hanley PW, Saturday G, Bosio CM, Anzick S, Barbian K, Cihlar T, Martens C, Scott DP, Munster VJ, de Wit E. Clinical benefit of remdesivir in rhesus macaques infected with SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020 Sep;585(7824):273-276. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2423-5. Epub 2020 Jun 9. PMID: 32516797; PMCID: PMC7486271.

Evidence tabellen

PICO: What is the (in)effectivity and safety of treatment with remdesivir compared to treatment without remdesivir in patients with COVID-19?

|

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

|

1. Remdesivir |

|||||||

|

Ader, 2021 |

Type of study: phase 3, open-label, adaptive, multicentre, randomised, controlled trial

Setting: 48 sites in Europe, Between March 22, 2020, and Jan 21, 2021

Country: France, Belgium, Austria, Portugal, Luxembourg

Source of funding: European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Europe); Austrian Group Medical Tumor (Austria); Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (Belgium); Fonds Erasme-COVID-Université Libre de Bruxelles (Belgium); REACTing, a French multi-disciplinary collaborative network working on emerging infectious diseases (France); Ministry of Health (France); Domaine d’intérêt majeur One Health Île-de-France (France); European Regional Development Fund (Luxembourg); Ministry of Health (Portugal); Agency for Clinical Research and Biomedical Innovation (Portugal). We thank all participants who consented to enrol in the trial, as well as all study and site staff whose indispensable assistance made the conduct of the DisCoVeRy trial possible (all listed in the appendix 2 pp 35–47).

Conflicts of interest: DC reports grants and lecture fees from Janssen and lecture fees from Gilead, outside the submitted work….

Please refer to full text for the full conflicts of interest. |

Hospitalized patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Total:= 857 Intervention: = 429 Control: N = 428

ITT population: I: 414 C: 418

Important characteristics: Age, median (IQR): I: 63 (55–73) C: 64 (54–72)

Sex, n/N (%) male: I: 291/414 (70%) C: 288/418 (69%)

7-point ordinal scale at baseline: 3: hospitalised, not requiring supplemental oxygen: I:8 (2%) C: 8 (2%) 4: hospitalised, requiring supplemental oxygen I: 241 (58%) C: 244 (58%) 5: hospitalised, on non-invasive ventilation or high flow oxygen devices I: 90 (22%) C: 93 (22%) 6: hospitalised, on invasive mechanical ventilation or ECMO I: 75 (18%) C: 73 (18%)

Groups were comparable at baseline.

|

Remdesivir was administered intravenously at a loading dose of 200 mg on day 1 followed by a 100 mg, 1-h infusion once-daily for a total duration of 10 days |

standards of care |

Length of follow-up: 29 days

Loss-to-follow-up or incomplete data: Intervention: N = 0

Control: N = 0

|

Clinical outcomes

Death within 28 days I: 34 (8%) C: 37 (9%) OR 0·93 (95% CI: 0·57 to 1·52); p=0·77

7-point ordinal scale at day 15 (Primary Outcome) OR 0·98 (95% CI: 0·77 to 1·25); p=0·85

7-point ordinal scale at day 29 OR 1·11 (95% CI: 0·87 to 1·42); p=0·39

Duration of hospitalisation Days to hospital discharge within 29 days I: 15 (10 to 29) C: 13 (8 to 29) HR 0·94 (95% CI: 0·80 to 1·11); p=0·49

New mechanical ventilation, ECMO, or death within 29 days* I: 60/339 (18%) C: 87/344 (25%) HR 0·66 (95% CI: 0·47 to 0·91); p=0·010

Time to symptom resolution

Respiratory support Oxygenation-free days until day 29 I: 17 (2 to 22) C: 17 (0 to 23) Least-square mean difference (LSMD) 0·35 (–0·90 to 1·60); p=0·59

Ventilator-free days until day 29 I: 29 (20 to 29) C: 29 (16 to 29) LSMD 1·08 (–0·15 to 2·30); p=0·080

Safety Any Serious adverse events I: 135 (33%) C: 130 (31%) OR 1·11 (0·83–1·50); p=0·48

Any adverse events I: 241 (59%) C: 236 (57%) OR 1·14 (0·86–1·50); p=0·37

Virological outcomes The median decrease in viral loads between baseline and day 3 was similar in the remdesivir and control groups (appendix 2 pp 12–13). There was no significant effect of remdesivir on the viral kinetics (figure 3; appendix 2 pp 14, 29). |

Definitions: WHO Master Protocol:(1) not hospitalised, no limitation on activities; (2) not hospitalised, limitation on activities; (3) hospitalised, not requiring supplemental oxygen; (4) hospitalised, requiring supplemental oxygen; (5) hospitalised, on non-invasive ventilation or high flow oxygen devices; (6) hospitalised, on invasive mechanical ventilation or ECMO; and (7) dead.

Remarks: It was open-label and not placebo-controlled. Indeed, several treatments were concomitantly evaluated at the beginning of the trial, and masking was thus impossible due to the different modes of administration (intravenous, subcutaneous, or oral) of the different treatment groups.

Authors conclusion: In this randomised controlled trial, the use of remdesivir for the treatment of hospitalised patients with COVID-19 was not associated with clinical improvement at day 15 or day 29, nor with a reduction in mortality, nor with a reduction in SARS-CoV-2 RNA. |

|

Barratt-Due, 2021 |

Type of study: Independent, add-on RCT to WHO Solidarity trial, an open-label, adaptive RCT

Setting: 23 hospitals, between 28 March and 5 October 2020

Country: Norway

Source of funding: National Clinical Therapy Research, no role in RCT

Conflicts of interest: JTA reports grant from South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority. ABD reports paid lecture by Allergan Norden AB and participation in advisory board meeting SANOFI-AVENTIS Norwy. SGD reports grant from Research Council of Norway. FLJ reports funding from Oslo University Hospital and Helse SørØst. MT reports participation in European advisory board for Eli Lilly and coordinator of National reference group on COVID-19 treatment in Norway.

|

Hospitalized patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: N = 181 Remdesivir: n=42 Hydroxychloroquine: n=52 Control remdesivir: n=57 Control HSQ: n=54 (some controls were in both groups)

Important characteristics: Age, mean (SD): 59.8 (15.3) R: 59.7 y (16.5) CR: 58.1 y (15.7) H: 60.3 y (13.3) CH: 59.2 y (16.4)

Sex, n/N (%) male: R: 29/42 (69%) CR: 43/57 (75%) H: 31/52 (60%) CH: 34/54 (63%)

Disease severity, mean (SD): Defined by Viral load (log10 count/1000 cells) R: 1.6 (1.6) CR: 2.3 (1.8) H: 2.3 (1.5) CH: 2.0 (1.5)

Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, seroconverted (RDB ≥5) n/N (%) R: 14/42 (42.4%) CR: 18/57 (46.2%) H: 15/52 (42.9%) CH: 20/54 (54.1%)

Groups are not comparable on baseline regarding sex, comorbid conditions, ICU admission, P-F ratio less than 40 kPa, ACE and ARB medication, LDH level, D-dimer level, AST level, ALT, level. |

R: standard of care plus 200 mg intravenous remdesivir on day 1, 100 mg daily up to day 9

H: standard of care plus 800 mg oral hydroxychloroquine 2x day on day 1, 400 mg 2x day up to day 9

All study treatment were discontinued at discharge. |

Standard of care according to WHO guidelines recommending systemic steroids |

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: R: 9 (21%)

CR: 9 (16%)

H: 13 (24%)

CH: 8 (15%)

Incomplete outcome data: Missing data due to discharge or participant withdrawal were imputed with best outcome. Not reported how many.

|

Clinical outcomes Mortality (28 day) R: 2.4 (0.1; 10.1) CR: 5.2 (1.3-13.1) RD: -2.9 (-10.3; 4.5) H: 7.5 (2.4; 16.7) CH: 1.8 (0.1; 7.6) RD: 5.8 (-2.2; 13.7) Mortality (60 day) R: 7.1 (1.8; 17.5) CR: 5.3 (1.3; 13.1) RD: 1.9 (-7.8; 11.6) H: 7.5 (2.4; 16.7) CH: 1.8 (0.1; 7.6) RD: 5.8 (-2.2; 13.7) In-hospital mortality R: 7.1 (1.8; 17.5) CR: 7.0 (2.2; 15.6) RR: 1.0 (0.2; 4.6) H: 7.5 (2.4; 16.7) CH: 3.6 (0.6; 10.6) RR: 2.2 (0.4; 10.8)

Duration of hospitalization Not reported Admission to ICU during hospitalization R: 19.0 (9.2; 32.6) CR: 19.3 (10.5; 30.8) RD: -0.3 (-15.9; 15.4) H: 22.6 (12.8; 35.0) CH: 16.1 (8.1; 27.1) RD: 6.6 (-8.2; 21.4)

Time to symptom resolution Not reported

Respiratory support Mechanical ventilation R: 9.5 (3.1; 20.8) CR: 7.0 (2.2; 15.6) RD: 2.5 (-8.6; 13.6) H: 15.1 (7.2; 26.3) CH: 10.7 (4.4; 20.5) RD: 4.4 (-8.2; 17.0) Time to receipt mechanical ventilation RR R vs CR: 1.4 (0.4; 5.8) RR H vs CH: 2.1 (0.7; 6.2) Duration of mechanical ventilation Reported in appendix figure 1

Safety Adverse events n/N (%) R: 34/42 (81%) H: 26/52 (50%) C: 33/87 (n=38%) Serious adverse events n/N (%) R: 13/42 (31%) H: 12/52 (23%) C: 20/87 (n=23%)

Virological outcomes Viral clearance Not reported Viral load Reported in a figure 2 and appendix figure 2 Subgroup analysis based on symptom duration before hospitalization, the presence of ARS-CoV-2 antibodies, high or low viral load at hospital admission, degree of inflammation, and age were performed. |

Definitions: not applicable

Remarks:

Authors conclusion: The overall lack of effect of remdesivir and HCQ on the clinical course of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 was accompanied by a paucity of effect on SARS-CoV-2 viral clearance in the oropharynx. Our findings question the antiviral potential of these drugs in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

|

|

Mahajan, 2021 |

Type of study: RCT; not blinded

Setting: June to December 2020;

Country: India

Source of funding: “Financial support and sponsorship Nil. Conflicts of interest There are no conflicts of interest.”

|

Hospitalized COVID-19 patients with moderate-to-severe disease

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: N = 82 Randomized: Intervention: 41 Control: 41 Included in analysis: Intervention: 34 (incl. 1 cross over) Control: 36

Important characteristics: Age, mean (SD): I: 58.08±12.1 C: 57.41±14.1 Sex, n/N (%) male: I: 13 (38.3) C: 9 (25.0) Duration of symptoms before involvement in trial (days); mean±SD I: 6.26±2.49 C: 7.38±0.99 Receiving low flow supplemental oxygen I: 27 (79.4) C: 26 (72.2) Receiving non‑invasive ventilation or high‑flow oxygen I: 7 (20.6) C: 10 (27.8) Receiving invasive mechanical ventilation I: 0 (0) C: 0 (0)

Groups comparable at baseline? No, time from symptoms to enrolment longer in the control group, less patient in intervention group received non-invasive ventilation or high-flow oxygen in stead of low flow oxygen compared to the control group. |

Remdesivir + standard of care

IV 200 mg remdesivir on day 1, followed by 100 mg of remdesivir once daily for the subsequent four days

|

Standard of care

supportive therapy throughout the duration of the study. Other drugs used for COVID treatment (off-label use and in the absence of written policy) were not allowed to be administered to the patients in the study period. Drugs like corticosteroids and heparin were given as per standard of care protocol. |

Length of follow up: 12 days, or until discharge of death

Loss to follow-up: I: 8/41 (19.5%) Reasons: 2 patients discharged, 1 patient died, 2 witheld treatment, 3 remdesivir C: 5/41 (12.2%) Reasons: 2 patients discharged, 2 patients died, 1 requested remdesivir treatment |

Clinical outcomes Mortality Reported as ‘death’, score 6, on ordinal scale. Unclear at which moment in time (1 result for 12 to 24 days): Death I: 5 (14.7) C: 3 (8.3)

Duration of hospitalization No data reported

Symptom resolution Nausea, vomiting I: Baseline: 7 After treatment: 3 C: Baseline: 9 After treatment: 2

Need for respiratory support Clinical status from day 12 to 24 Did not require hospitalisation* I: 2 (5.9) C: 3 (8.3) Hospitalised, but did not require supplemental oxygen I: 0 (0) C: 0 (0) Hospitalised, required supplemental oxygen I: 4 (11.8) C: 6 (16.7) Required high‑flow oxygen or non‑invasive ventilation I: 19 (55.9) C: 22 (61.1) Required or received mechanical ventilation I: 4 (11.8) C: 2 (5.6) Death I: 5 (14.7) C: 3 (8.3)

Also reported: AST levels, ALT levels and creatinine levels at baseline and after treatment

Safety Adverse events

Virological outcomes Viral clearance not reported |

Definitions: Clinical status day 1 – 12; assessed on 4-point ordinal scale: 1), receiving low-flow oxygen supplementation; 2), receiving non-invasive ventilation or high-flow oxygen; 3), not receiving supplemental oxygen but requiring medical care; 4), receiving invasive mechanical ventilation

Clinical status day 12 – 24; assessed on 6-point ordinal scale: 1), Do not require hospitalisation, 2), hospitalised, but not requiring supplemental oxygen, 3), hospitalised, requiring supplemental oxygen; 4), Patients requiring high-flow oxygen or non-invasive ventilation; 5), Requiring or receiving mechanical ventilation; 6), Death

Remarks:

Authors conclusion: Remdesivir therapy for five days did not produce improvement in clinical outcomes in moderate to severe COVID‑19 cases.

|

|

Pan, 2020 |

Type of study: RCT (open-label, non-blinded)

Setting & country: 405 hospitals in 30 countries; WHO Solidarity Trial

Source of funding: Funded by the World Health Organization;

ISRCTN Registry nr, ISRCTN83971151; ClinicalTrials.gov nr, NCT04315948.)

|

N total at baseline: N = 11,330

Remdesivir arm I: 2743 C: 2708

Important characteristics: Age, n/N (%): I: <50y: 961/2743 (35%) 50-69y: 1282/2743 (47%) ≥70y: 500/2743 (18%) C: <50y: 952/2708 (35%) 50-69y: 1287/2708 (48%) ≥70y: 469/2708 (17%) Sex, n/N (%) male: I: 1706/2743 (62%) C: 1725/2708 (64%) Respiratory support I: No suppl. Oxygen at entry: 661/2743 (24%) Suppl. Oxygen at entry 1828/2743 (67%) Already receiving ventilation 254/2743 (9%) C: No suppl. Oxygen at entry: 664/2708 (25%) Suppl. Oxygen at entry 1811/2708 (67%) Already receiving ventilation 233/2708 (9%) Previous days in hospital I: 0 days: 724/2743 (26%) 1 day: 917/2743 (33%) ≥2 days: 1102/2743 (40%) C: 0 days: 712/2708 (26%) 1 day: 938/2708 (35%) ≥2 days: 1058/2708 (39%) |

Remdesivir

Intravenous; 200 mg on day 0 and 100 mg on days 1 through 9.

Taking trial drug midway through scheduled duration*: I: 96% C: 2%

Use of non-study drug, n/N (%): Corticosteroids I: 1310 (47.8%) C: 1288 (47.6%) Convalescent plasma I: 52 (1.9%) C: 58 (2.1%) Anti-IL-6 drug I: 133 (4.9%) C: 143 (5.3%) Non-trial interferon I: 3 (0.1%) C: 25 (0.9%) Non-trial antiviral I: 65 (2.4%) C: 152 (5.6%) |

Standard of care

|

Length of follow up: 28 days, or up to discharge

Loss to follow-up: I: 7/2750 (0.3%) Reasons: no or unknown consent C: 17/2725 (0.6%) Reasons: no or unknown consent

|

Clinical outcomes

All-cause in-hospital mortality, regardless of whether death occurred before or after day 28: I: 301/2743 (12.5%) C: 303/2708 (12.7%) RR 0.98 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.14) HR=0.95 (95% CI 0.81-1.11) Adjusted** HR=0.95 (95% CI 0.81-1.11)

All-cause in-hospital mortality, stratified by ventilation at randomization: Ventilated: HR 1.20 (95% CI 0.89-1.64) Not ventilated: HR 0.86 (95% CI 0.72-1.04)

Initiation of mechanical ventilation, in those not receiving ventilation at baseline: I: 295/2489 (11.6%) C: 284/2475 (11.5%) RR 1.03 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.20)

Composite death or initiation ventilation: I: 479/2743 (18.5%) C: 479/2708 (18.9%) RR 0.99 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.11) Publication: RR 0.97 [0.85-1.10]

Hospitalized, not discharged: Percentage of patients (rather than number of patients) ever reported as discharged who were still in the hospital: Day 7, % I: 69% C: 59% Day 14 I: 22% C: 19% Day 21 I: 9% C: 8% |

Definitions/information:

*Taking trial drug midway through scheduled duration, %, calculated only among patients who died or were discharged alive, % patients who were taking the trial drug midway through its scheduled duration (or midway through the time from entry to death or discharge, if this was shorter).

**Adjusted model all-cause mortality: some overlap between the 4 control groups; an exploratory sensitivity analysis used multivariate Cox regression to fit all 4 treatment effects simultaneously; adjusted for several prognostic factors (age, sex, diabetes, bilateral lung lesions at entry (no, yes, not imaged at entry), and respiratory support at entry (no oxygen, oxygen but no ventilation, ventilation).

Authors conclusion: These remdesivir, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir, and interferon regimens had little or no effect on hospitalized patients with Covid-19, as indicated by overall mortality, initiation of ventilation, and duration of hospital stay. |

|

Beigel, 2020

|

Type of study: Double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial

Setting + Country: There were 60 trial sites and 13 subsites in the United States (45 sites), Denmark (8), the United Kingdom (5), Greece (4), Germany (3), Korea (2), Mexico (2), Spain (2), Japan (1), and Singapore (1).

Source of funding: Funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and others; ACCT-1 ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT04280705 |

Inclusion criteria:

[more detailed information can be found in the supplementary file]

Exclusion criteria:

[more detailed information can be found in the supplementary file]

N total at baseline: N = 1062 Intervention: 541 Control: 521

Important characteristics: Intervention group: Age (mean (SD)): 58.6 (14.6) Male: 352 (65.1%)

Control group: Age (mean (SD)): 59.2 (15.4) Male: 332 (63.3%) Groups comparable at baseline. |

Remdesivir: days 2 through 10 or until hospital discharge or death |

Placebo: Matching placebo was administered according to the same schedule and in the same volume as the active drug. |

28 days |

Remdesivir versus control

Median recovery time: Remdesivir: 10 days (95% CI 9 – 11) Placebo: 15 days (95% CI 13 – 18)

Recovery HR for recovery: 1.29; 95% CI, 1.12 to 1.49; P<0.001).

Mortality by 14 days Remdesivir: 6.7% Placebo 11.9% HR for death: 0.55; 95% CI, 0.36 to 0.83) Serious adverse events Remdesivir: 24.6% |

Comments:

Authors conclusion: Remdesivir was superior to placebo in shortening the time to recovery in adults who were hospitalized with Covid-19 and had evidence of lower respiratory tract infection.

|

|

Spinner, 2020 |

Type of study: Randomized open-label multicentre clinical trial

Setting: 105 hospitals

Country: US, Europe and Asia

Source of funding: Gilead Sciences, which designed and conducted the study in consultation with the FDA and the investigators.

|

Inclusion criteria: Willing and able to provide written informed consent; aged ≥ 18 years (at all sites), or aged ≥ 12 and < 18 years of age weighing ≥ 40 kg; SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by PCR ≤ 4 days before randomization; currently hospitalized; SpO2 > 94% on room air at screening; radiographic pulmonary infiltrates; men and women of childbearing potential who engage in heterosexual intercourse must agree to use protocol specified method(s) of contraception.

Exclusion criteria: Participation in any other clinical trial of an experimental agent treatment for COVID-19; concurrent treatment with other agents with actual or possible direct acting antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 < 24 hours prior to study drug dosing; Requiring mechanical ventilation at screening; ALT or AST > 5 x ULN; creatinine clearance < 50 mL/min, pregnant or breastfeeding woman; known hypersensitivity to the study drug, the metabolites, or formulation excipient.

N total at baseline: N = 596 Intervention1: 197* Intervention2: 199* Control: 200*

Of which respectively 193 (I1), 191 (I2) and 200 (C) patients were included in primary analysis.

Important characteristics: Age, median (IQR): I1: 56 (45-66) I2: 58 (48-66) C: 57 (45-66) P=not reported Sex, n/N (%) male: I1: 118/193 (61) I2: 114/191 (60) C: 125/200 (63) P=not reported

Groups comparable at baseline? Patients in standard care group were more commonly prescribed with other COVID-19 agents. |

I1: Remdesivir for 10 days. 73 (38%) patients completed the assigned treatment duration; the median number of doses for the group was 6 (range, 1-10). Reasons were hospital discharge (n=98), withdrawal (n=8) or adverse events (n=6).

I2: Remdesivir for 5 days. 145 (76%) patients completed the assigned treatment duration (median, 5 doses; range, 1-5). Reasons were hospital discharge (n=35), withdrawal (n=5) or adverse events (n=4).

Remdesivir was dosed intravenously (30-60 minutes) at 200 mg on day 1 followed by 100 mg/d.

Remdesivir treatment was to be discontinued in any patient experiencing severe elevations in liver enzymes or decreases in estimated creatinine clearance to less than 30 mL/min.

|

Standard care (not specified) |

28 days (in person for hospitalized patients or by phone for discharged patients)

|

Difference in clinical status distribution versus standard care (OR (95%CI) I1: not reported * P=0.18 I2: 1.65 (1.09 to 2.48) P=0.02 *The proportional odds assumption was not met.

Clinical improvement day 11 (n/N, %)** I1: 126/193 (65) I2: 134/191 (70) C: 121/200 (61) Difference I1-C (95%CI): 4.8 (−5.0 to 14.4) Difference I2-C (95%CI): 9.7 (0.1 to 19.1) Clinical improvement day 28 (n/N, %)** I1: 174/193 (90) I2: 171/191 (90) C: 166/200 (83) Difference I1-C: not reported Difference I2-C: not reported **Defined as ≥2-point improvement from baseline on the 7-point ordinal scale.

Recovery at day 11 (n/N, %)*** I1: 132 (68) I2: 141 (74) C: 128 (64) Difference I1-C (95%CI): 4.4 (−5.0 to 13.8) Difference I2-C (95%CI): 9.8 (0.3 to 19.0) Recovery at day 28 (n/N, %)*** I1: 178 (92) I2: 175 (92) C: 170 (85) Difference I1-C: not reported Difference I2-C: not reported ***Defined as improvement from a baseline score of 2-5 to a score of 6 or 7 or from a baseline score of 6 to a score of 7, on the 7-point ordinal scale.

All-cause mortality at day 28 (n/N, %) I1: 3/193 (2) I2: 2/191 (1) C: 4/200 (2) HR (95%CI) I1 vs C: 0.76 (0.17 to 3.40) HR (95%CII I1 vs C: 0.51 (0.09 to 2.80)

Adverse events (n/N, %) Any adverse event I1: 113/193 (59) I2: 98/191 (51) C: 93/200 (47) Any serious adverse event I1: 10/193 (5) I2: 9/191 (5) C: 18/200 (9)

There were no significant differences between the remdesivir and standard care groups in duration of oxygen therapy or hospitalization (data not reported). |

Remarks: Patients who had sufficiently improved in the judgment of the investigator could be discharged from the hospital before finishing their assigned course of treatment.

Data on clinical improvement and recovery are also reported for other days. Furthermore, data on other exploratory outcome measures and details on adverse events were reported, but data is not shown here.

Peaks in discharge rates were observed in the remdesivir groups following the end of their assigned duration of treatment (i.e., there were increased rates of discharge on day 6 in the 5-day remdesivir group and on day 11 in the 10-day group), suggesting that discharges were delayed for some patients to allow them to complete full courses of assigned remdesivir treatment.

Original protocol was amended on the basis of emerging understanding of the clinical presentation and assessment of COVID-19.

Authors conclusion: Among patients with moderate COVID-19, those randomized to a 10-day course of remdesivir did not have a statistically significant difference in clinical status compared with standard care at 11 days after initiation of treatment. Patients randomized to a 5-day course of remdesivir had a statistically significant difference in clinical status compared with standard care, but the difference was of uncertain clinical importance. |

|

Wang, 2020a |

Type of study: Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial

Setting: 10 hospitals in Wuhan, Hubei, between Feb 6 and March 12, 2020

Country: China

Source of funding: Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Emergency Project of COVID-19, National Key Research and Development Program of China, the Beijing Science and Technology Project

Conflicts of interest: One author has served as non-compensated consultant to Gilead Sciences on its respiratory antiviral program, outside the submitted work. All other authors declare no competing interests.

|

Inclusion criteria:

Eligible patients of child-bearing age (men and women) agreed to take effective contraceptive measures (including hormonal contraception, barrier methods, or abstinence) during the study period and for at least 7 days after the last study drug administration

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: N = 237 Intervention: 158 Control: 79

Important characteristics: Age, median (IQR) I: 66 (57–73) C: 64 (53–70) Sex, n/N (%) male: I: 89/158 (56%) C: 51/78 (65%) Time from symptom onset to starting study treatment, n/N (%) of ≤10 days I: 71/155 (46%)

Groups comparable at baseline? More patients with hypertension, diabetes, or coronary artery disease in the remdesivir group than the placebo group. More patients in the control group than in the remdesivir group had been symptomatic for 10 days or less at the time of starting remdesivir or placebo treatment, and a higher proportion of remdesivir recipients had a respiratory rate of more than 24 breaths per min. No other major differences in symptoms, signs, laboratory results, disease severity, or treatments were observed between groups at baseline. |

Remdesivir

Treatment regimens Intravenous remdesivir (200 mg on day 1 followed by 100 mg on days 2–10 in single daily infusions) for a total of 10 days (both provided by Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA, USA). |

Placebo