JAK remmers

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van Janus-geassocieerde kinasen (JAK) remmers bij de behandeling van COVID-19 patiënten?

Aanbeveling

Behandel opgenomen patiënten met respiratoire klachten door COVID-19 en een toegenomen zuurstofbehoefte met tocilizumab 600 mg eenmalig i.v. indien zij reeds zijn gestart met dexamethason en een CRP ≥75 mg/L hebben en een persisterend respiratoire verslechtering leidend tot noodzaak tot hoge zuurstofsuppletie - via een venturimasker (≥6 L O2), non-rebreathing masker, NIV of high flow nasal oxygen (Optiflow) - met als meest aannemelijke verklaring de COVID-19 geïnduceerde longinflammatie (niet bijv. longembolieën of bacteriële pneumonie).

Behandel patiënten met respiratoire insufficiëntie die vanaf de SEH direct op de IC worden opgenomen (en daarom buiten het ziekenhuis al eerder aan de bovengenoemde criteria zouden hebben voldaan) naast dexamethason met tocilizumab. Hierbij wordt geadviseerd de therapie <24 uur na opname op de IC toe te dienen.

Indien tocilizumab niet beschikbaar is of dit om een andere reden niet gegeven kan worden, dan kan andere anti-inflammatoire therapie overwogen worden:

- baricitinib oraal 4 mg dagelijks gedurende 14 dagen of tot ontslag of sarilumab 400 mg i.v. eenmalig (geen voorkeur uitgesproken voor een van beide middelen).

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de verschillen in uitkomsten tussen behandeling met en zonder een Januskinase (JAK) remmer bij opgenomen en niet-opgenomen volwassenen met COVID-19. Tot 31 maart 2022 werden er 6 gerandomiseerde gecontroleerde studies (RCT’s) gevonden in patiënten die waren opgenomen in het ziekenhuis (n=1494 in de interventiegroep en n=1495 in de controlegroep). Er waren tot die tijd geen studies die systemische therapie met JAK remmers onderzochten in patiënten die niet waren opgenomen in het ziekenhuis. Een studie die inhalatie therapie met nezulcitinib (TD-0903) onderzocht, werd - vanwege de niet systemische toediening – wel gevonden in de search maar niet meegenomen in het daaropvolgende literatuur onderzoek. Dit onderzoek zal in de overige overwegingen kort besproken worden.

De geïncludeerde studies onderzochten verschillende JAK remmers: ruxolitinib (Cao, 2020), tofacitinib (Guimaraes, 2021; Murugesan, 2021), baricitinib (Kalil, 2020; Marconi 2021; Ely, 2022). Dit is van belang omdat deze JAK-remmers niet allen precies dezelfde kinasen remmen, maar hoofdzakelijk bepaalde subtypes (JAK-1, JAK-2 en/of JAK-3), Er werden alleen RCT’s geïncludeerd in de analyse, waardoor de kwaliteit van bewijs initieel hoog was. De kwaliteit van dit bewijs werd waar nodig naar beneden bijgesteld vanwege een grote spreiding van de puntschatter van de uitkomstmaat, beperkte patiëntaantallen (imprecisie) en/of inconsistentie van de resultaten. De bewijskracht van de cruciale uitkomstmaten binnen patiënten die opgenomen waren in het ziekenhuis komt uit op ‘redelijk’ voor mortaliteit en ‘laag’ voor noodzaak tot uitgebreide respiratoire ondersteuning.

Studies in patiënten die waren opgenomen in het ziekenhuis

Op basis van de gevonden resultaten wordt er geconcludeerd dat er voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat ‘mortaliteit’ waarschijnlijk een klinisch relevante afname is bij het gebruik van JAK remmers. Voor de andere cruciale uitkomstmaat ‘uitgebreide respiratoire ondersteuning’ was het bewijs minder overtuigend. Zowel bij mortaliteit als bij de noodzaak tot respiratoire ondersteuning was er een statistisch significant voordeel te zien van behandeling met JAK remmers (pooled risk ratio voor mortaliteit 0.63, 95% CI 0.51 - 0.78, pooled risk ratio voor respiratoire ondersteuning 0.66, 95% CI 0.48-0.91). Dit effect bleek klinisch significant voor de uitkomstmaat mortaliteit, gebaseerd op de vooraf gedefinieerde grenzen van klinische significantie (>3 absolute procentpunten na gepoolde analyse). Het absolute risicoverschil van JAK remmers op respiratoire ondersteuning was 4% punten, want net onder de vooraf gedefinieerde grenzen van klinische significantie was (>5 absolute procentpunten na gepoolde analyse).

In de grootste geïncludeerde studie (Marconi, 2021) was het voordeel van de JAK remmer baracitinib op de mortaliteit 5% punten (statistisch significant), dit was een secundaire uitkomstmaat van de studie. In deze multicenter placebo gecontroleerde RCT werden 1525 patiënten gerandomiseerd naar standaardzorg plus baricitinib 4 mg 1dd of standaardzorg. De 28 dagen en 60 dagen mortaliteit (secundaire uitkomstmaten) lagen statistisch significant lager in de groep die was behandeld met baricitinib (28 dagen mortaliteit 8% versus 13% (HR 0.57; CI 95% 0.41-0.78)). Circa 90 procent van de patiënten werd ook behandeld met dexamethason, maar ook andere behandelingen, zoals remdesivir, waren toegestaan. Een belangrijk deel van de patiënten (>80%) startte met baricitinib >7 dagen na start symptomen.

Het is op dit moment niet duidelijk hoe JAK remmers zoals baricitinib zich verhouden tot andere anti-inflammatoire therapieën. In de RCT’s van Marconi, Guimaraes, Cao en Ely gebruikten >70% van de patiënten ook corticosteroïden, waardoor een klein additioneel voordeel van JAK remmers aannemelijk lijkt. In geen van de studies werd echter een combinatie met IL-6 remmers of IL-1 remmers gebruikt of werd er gerandomiseerd naar JAK of IL-6 of IL-1 remming, waardoor de plaats van JAK remmers ten opzichte van deze middelen onduidelijk blijft. Een combinatie van een JAK remmer en bijvoorbeeld tocilizumab (IL-6 remmer) wordt ontraden vanwege het veronderstelde hogere risico op secundaire infecties.

Daarnaast is het nog niet duidelijk in welk ziektestadium of bij welke inflammatiemarkers (CRP, ferritine) er het meest effect van JAK remming te verwachten valt. Het grootste effect van antivirale therapie wordt met name vroeg verwacht, terwijl het anti-inflammatoire effect later in het ziektebeloop wordt verwacht. Aangezien JAK remmers zoals baricitinib en tofacitinib beide eigenschappen bezitten, kan de timing van deze toediening belangrijk zijn. In de studies in deze richtlijn werden patiënten relatief laat behandeld: gemiddeld 20 dagen na het ontstaan van symptomen bij de studie van Cao (2020), gemiddeld 10 dagen bij Guimaraes (2021) en 8 dagen bij Kalil (2020). Bij Marconi (2021) en Ely (2022) startte een belangrijk deel van de patiënten (>80%) met baricitinib meer dan 7 dagen na start symptomen en alle geïncludeerde patiënten bij Marconi hadden minimaal 1 verhoogde inflammatiewaarde. In subgroep analyses van Guimaraes (2021) en Kalil (2020) werd er geen overtuigend bewijs gezien dat behandeling met een JAK remmer vroeger of later in het beloop een verschil maakte. Wel toonde de studie van Kalil (2020) dat er een snellere klinische verbetering was in een subgroep van patiënten die bij randomisatie non-invasieve beademing kregen. Dit voordeel werd niet gezien bij patiënten die lagen opgenomen met mechanische ventilatie. In de huidige richtlijn werd een subgroep analyse gedaan waarin patiënten werden gestratificeerd naar ernst van ziekte. Een gepoolde analyse van de studies van Kalil (2020), Marconi (2021), Guimaraes (2021) en Ely (2022) liet consequent een voordeel gezien van JAK remming bij patiënten met zuurstof op de afdeling (matig ernstige ziekte) en bij patiënten met invasieve respiratoire ondersteuning (ernstige ziekte).

Soort JAK remmer

Drie van de zes geïncludeerde trials bestudeerden baricitinib, waaronder de twee grootste RCT’s, waardoor binnen de categorie JAK remmers er een voorkeur wordt uitgesproken voor baricitinib.

Combinatietherapie of monotherapie

De Engelse en Amerikaanse richtlijnen spraken eerder een voordeel uit voor combinatietherapie van een JAK remmer met bijvoorbeeld remdesivir. Deze aanbeveling werd gedaan toen de studie van Kalil (2020) het grootste bewijs vormde in het voordeel van baricitinib. Echter, ook baricitinib zonder een andere virusremmer lijkt effectief in het verlagen van de mortaliteit (Marconi, 2021). Wel is combinatietherapie met dexamethason aan te bevelen. Data over de combinatie van JAK remmers met andere anti-inflammatoire therapie (anders dan corticosteroïden) zoals IL-6 remmers is op dit moment niet aanwezig. Een dergelijke combinatietherapie wordt dan ook niet aanbevolen buiten studieverband.

Studies in ambulante patiënten

Er werden geen studies gevonden die JAK-remmers vergeleken met placebo in niet-opgenomen volwassenen met COVID-19.

Overige overwegingen

Bijwerkingen

Een meta-analyse die de bijwerkingen JAK remmers bekeek tijdens behandeling van reumatoïde artritis, toonde dat behandeling met JAK remmers geassocieerd was met een hoger infectierisico (met name reactivatie van herpes virussen) en toonde een mogelijke associatie met: cardiovasculaire problematiek waaronder veneuze trombo-embolische complicaties, gastro-intestinale perforatie en maligniteit (Honda, 2020; Peng, 2020). Het risico op bijvoorbeeld (ernstige) infecties verschilde per JAK remmer (Bechman, 2019).

Bijwerkingen die gezien worden bij een langdurige behandeling met JAK remmers, zoals bij bovengenoemde chronische ziekte, zijn mogelijk anders dan de bijwerkingen die gezien kunnen worden bij COVID-19 behandeling, waarbij patiënten maximaal 14 dagen werden behandeld. In de RCT’s in deze richtlijn werd er ook gekeken naar bijwerkingen van JAK remmers ten opzichte van placebo. De meest voorkomende ‘serious adverse events’ waren een verhoging van de leverenzymen (ALT) of het ontstaan van een lymfopenie (Guimaraes, 2021). In geen van de studies werden er meer bijwerkingen gezien in de interventie groep vergeleken met placebo. Ook als er specifiek gekeken werd naar infectieuze complicaties (Marconi, 2021; Cao, 2021; Guimaraes, 2021; Ely, 2022), werden deze niet meer gezien vergeleken met de placebogroep.

Virusvarianten

Sinds de opkomst van de omikron variant van SARS-CoV-2 in Nederland eind 2021, is de kans op een ernstig beloop van COVID-19 op populatieniveau zeer sterk gedaald. Het is van belang om op te merken dat de besproken gerandomiseerde studies werden verricht voor de opkomst van de omikron variant. Het is onduidelijk wat de invloed is van deze variant op het effect van anti-inflammatoire therapie, al wordt aangenomen dat patiënten die door de omikron variant een ernstige COVID-19 infectie ontwikkelen nog steeds baat hebben bij anti-inflammatoire therapie. De ‘number needed to treat’ zou wel anders (vermoedelijk hoger) kunnen zijn.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Op grond van de bekende onderzoeksgegevens kunnen JAK remmers worden ingezet in de behandeling van COVID-19. In de behandeling van COVID-19, waar deze middelen relatief kortdurend worden voorgeschreven, werden er wel voordelen van JAK remmers gevonden (zoals een lagere mortaliteit), maar werden er niet meer bijwerkingen gezien. Mogelijk zijn de patiënten aantallen nog niet groot genoeg om alle bijwerkingen in de behandeling van COVID-19 aan te tonen. Een potentieel verhoogd risico op infecties of andere bijwerkingen die bij de behandeling van bijvoorbeeld reumatoïde artritis gezien werden, moet dus meegewogen worden in de keuze om een patiënt met een JAK remmer te behandelen. Deze potentiële bijwerkingen spelen overigens ook een rol bij andere anti-inflammatoire middelen die ingezet kunnen worden bij COVID-19.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

In de huidige studies varieert de gebruikte JAK remmer en de duur van de behandeling. In de grootste studie van Marconi (2021) werd 4mg baricitinib gedurende 14 dagen voorgeschreven. De kosten die met deze behandeling gepaard gaan zijn ongeveer 400-500 euro. Hierin zijn niet de opname in het ziekenhuis of andere bijkomende kosten meegenomen.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Op grond van de bekende onderzoeksgegevens kunnen JAK remmers worden ingezet in de behandeling van COVID-19. Baricitinib is beschikbaar in Nederland en patiënten die in aanmerking komen voor deze behandeling liggen opgenomen in het ziekenhuis. De werkgroep voorziet geen problemen qua implementatie.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Gebaseerd op de RCT’s in deze richtlijn wordt er geconcludeerd dat behandeling met JAK-remmers (in het bijzonder baricitinib) waarschijnlijk zorgt voor een klinisch relevante afname van de mortaliteit binnen 28 dagen vergeleken met placebobehandeling bij opgenomen patiënten met COVID-19.

Het mortaliteits-voordeel van JAK remming is met name bestudeerd in een (matig) ernstig zieke populatie, waar ook bewijs is voor een meerwaarde van IL-6 remming (in het bijzonder tocilizumab). Van beide soorten middelen beschrijven RCT’s geen significante bijwerkingen bij behandeling van COVID-19, al betreft dit een relatief korte follow-up.

Het verwachte effect en de bewijskracht van de literatuur betreffende het effect van baricitinib en tocilizumab op mortaliteit is vergelijkbaar, vooral als er niet alleen gekeken wordt naar de 28 dagen mortaliteit maar ook andere follow-up duur. Er is meer ervaring met tocilizumab in de behandeling van COVID-19 in Nederland en dit middel werd in grotere aantallen patiënten onderzocht: 12 RCT’s onderzochten bij ruim 7000 patiënten het effect van tocilizumab, 3 RCT’s onderzochten bij ruim 2500 patiënten baricitinib. In patiënten met een (matig) ernstige COVID-19 infectie wordt er daarom een voorkeur uitgesproken voor tocilizumab.

Behandeling met JAK-remmers, in het bijzonder baricitinib, zorgt waarschijnlijk voor een klinisch relevante afname van de mortaliteit binnen 28 dagen bij een geselecteerde groep ((matig) ernstig zieke populatie) opgenomen patiënten met COVID-19. In deze groep is er ook een voordeel te zien IL-6 remmers, in het bijzonder bij tocilizumab. Op basis van bovenstaande bewijs is het advies:

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Een infectie met SARS-CoV-2 kan leiden tot een ernstige pneumonie en ARDS. Een dysregulatie van de immuunrespons lijkt in de pathofysiologie van COVID-19 een belangrijke rol te spelen (Veerdonk, 2022). Janus-geassocieerde kinasen (JAK) remmers kunnen worden gebruikt om cel proliferatie te remmen maar ook als anti-inflammatoire therapie, zoals bij reumatoïde artritis en eczeem. Een Italiaanse observationele studie toonde een significante reductie van de hoeveelheid inflammatoire cytokines, een toename van de circulerende B- en T-cellen en een toegenomen antistof productie tegen het SARS-COV-2 spike eiwit bij 20 patiënten met een ernstige COVID-19 die met de JAK remmer baricitinib werden behandeld (Bronte, 2020). Daarnaast lijken baricitinib en ruxolitinib ook een antiviraal effect te hebben, door remming van de endocytose van SARS-CoV-2 (Gatti, 2021; Richardson, 2020).

Inmiddels hebben diverse gerandomiseerde gecontroleerde studies (RCT’s) de effectiviteit van JAK remmers onderzocht om de plaats van deze middelen bij de behandeling COVID-19 te bepalen. Klinische dose-finding studies zijn in deze setting nooit verricht. De groep JAK remmers uit dit literatuuronderzoek bevat meerdere middelen: baricitinib en ruxolitinib (JAK 1 en JAK 2 remmers) en tofacitinib (JAK 1/3 remmer met mogelijk ook werking tegen JAK 2). Alleen systemische middelen werden bij het literatuuronderzoek meegenomen. Inhalatie therapie met JAK remmers (zoals nezulcitinib) zal kort in de overwegingen worden besproken.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Hospitalized patients

Mortality (crucial)

|

Moderate GRADE |

Treatment with a JAK inhibitor probably reduces mortality when compared with treatment without a JAK inhibitor in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Source: Cao, 2020; Ely, 2022; Guimarães, 2021; Kalil, 2020; Marconi, 2021. |

Extensive respiratory support (crucial)

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with a JAK inhibitor may result in limited difference in need for extensive respiratory support when compared with treatment without a JAK inhibitor in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Source: Cao, 2020; Guimarães, 2021; Kalil, 2020. |

Duration of hospitalization (important)

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with a JAK inhibitor may result in little to no difference in length of stay when compared with treatment without a JAK inhibitor in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Source: Cao, 2020; Ely, 2022; Guimarães, 2021; Marconi, 2021. |

Time to clinical improvement (important)

|

Moderate GRADE |

Treatment with a JAK inhibitor probably results in little to no difference in time to clinical improvement when compared with treatment without a JAK inhibitor in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Source: Kalil, 2020; Marconi, 2021. |

Non-hospitalized patients

|

- GRADE |

No conclusions can be drawn about the comparison of treatment with a JAK inhibitor with treatment without a JAK inhibitor in non-hospitalized patients, because no studies were found that reported relevant outcomes for the comparison. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Cao (2020) performed a prospective, multicenter, single-blind, randomized controlled phase II trial, which was conducted in China. They evaluated clinical improvement by comparing ruxolitinib plus standard of care treatment or placebo based on standard of care treatment in hospitalized adults with severe COVID-19. In total 43 were included as they met the criteria (i.e., met the diagnostic criteria for COVID-19; were 18 years or older and younger than 75 years; were severely cases according to the Chinese management guideline for COVID-19 version 5.0. These patients were randomized to receive ruxolitinib (n=22) or placebo (n=21), both with standard of care. After randomization, 2 patients were excluded from the ruxolitinib group because 1 was found to be ineligible because of persistent humoral immune deficiency after B-cell mature antigen–targeting chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, while another withdrew the consent before treatment started. Placebo treatment included 100mg vitamin C twice a day. Standard of care included antiviral therapy, supplemental oxygen, non-invasive and invasive ventilation, corticosteroids (in 70% of the patients), antibiotic agents, vasopressor support, renal-replacement therapy, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. The mean age was 63 years, and 59% were male. The length of the follow-up was 28 days. The following outcome measures were reported; mortality, need for respiratory support, and duration of hospitalization. The primary efficacy end point was the time to clinical improvement. No statistical differences were detected in terms of clinical improvement between the 2 groups. The study had a high risk of bias for outcomes directly related to treatment decisions, as treating physicians were aware of group allocations.

Ely (2022) reported efficacy and safety of baricitinib in a critically ill cohort not previously included in the COV-BARRIER trial. In this multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial, participants were enrolled across 18 centres in four countries. Eligible patients were those aged 18 years or older, who had been hospitalised with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, with use of IMV or ECMO at study entry and randomisation, evidence of pneumonia or clinical symptoms of COVID-19, and indicators of progression risk with at least one elevated inflammatory marker greater than the upper limit of normal range based on the local laboratory result (C-reactive protein, D-dimer, lactate dehydrogenase, or ferritin). Baricitinib 4 mg (N=51) or matched placebo (N=50) was crushed for nasogastric tube delivery (or given orally when feasible) and given once daily for up to 14 days or until discharge from hospital, whichever occurred first. Participants assigned to baricitinib with baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 30 to less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m² received baricitinib 2 mg or matched placebo. If eGFR decreased to 30 to less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m² after randomisation, patients received baricitinib 2 mg until eGFR returned to 60 mL/min per 1.73 m² or greater. All participants received standard of care in keeping with local clinical practice for COVID-19 management, which could include concomitant medications such as corticosteroids (84% in the baricitinib group, 88% in the control group), antivirals (remdesivir 0% in the baricitinib group, 4% in the control group). The prespecified key endpoints for this exploratory trial were all-cause mortality at day 28 and day 60; number of ventilator-free days; overall improvement (assessed by odds of improvement in clinical status) on NIAID-OS, evaluated at days 4, 7, 10, 14, and 28; proportion of participants with at least 1-point improvement on the NIAID-OS or live discharge from hospital at days 4, 7, 10, 14, and 28; duration of hospitalisation; and time to recovery through day 28. As the cohort reported here was an addition to the parent trial study design (COV-BARRIER), all endpoints are considered exploratory. Primary endpoints were not defined.

Guimarães (2021) (STOP-COVID trial) performed a randomized controlled phase II trial, which was conducted in Brazil. They evaluated effectiveness of tofacitinib, compared with placebo plus standard care in hospitalized adults with COVID-19 pneumonia. In total 289 were included as they met the criteria (i.e., 18 years of age or older who had laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, who had evidence of COVID-19 pneumonia on radiographic imaging (computed tomography or radiography of the chest), and who had been hospitalized for less than 72 hours). These patients were randomized to receive tofacitinib (n=144) or placebo (n=145), both in addition to standard of care. Placebo treatment included oral placebo twice a day. Standard of care included glucocorticoids (89%), antibiotic agents, anticoagulants, and antiviral agents. The mean age was 56 years, and 56% were male. The length of the follow-up was 28 days. The following outcome measures were reported; mortality, need for respiratory support, and duration of hospitalization. The primary outcome was the occurrence of death or respiratory failure through day 28 as assessed with the use of an eight-level ordinal scale (with scores ranging from 1 to 8 and higher scores indicating a worse condition). The cumulative incidence of death or respiratory failure through day 28 was 18.1% in the tofacitinib group and 29.0% in the placebo group (risk ratio, 0.63; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.41 to 0.97; P= 0.04).

Kalil (2020) (ACTT-2 trial) performed a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, which was conducted in USA, Singapore, South Korea, Mexico, Japan, Spain, UK and Denmark. They evaluated effectiveness of remdesivir and baricitinib or placebo, both in addition to standard care in hospitalized adults with COVID-19. In total 1033 were included as they met the criteria (i.e., hospitalized male or non-pregnant female adults with moderate to severe COVID-19). These patients were randomized to receive baricitinib plus remdesivir (n=518) or placebo and remdesivir (n=518), both in addition to standard of care. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis was recommended for all the patients without a major contraindication as standard of care. If a hospital had a written policy for Covid-19 treatments, patients could receive those treatments. The mean age was 55 years, and 53% were male. The length of the follow-up was 29 days. The following outcome measures were reported; mortality, and need for respiratory support. The primary outcome was the time to recovery. Patients receiving baricitinib had a median time to recovery of 7 days (95% confidence interval (CI), 6 to 8), as compared with 8 days (95% CI, 7 to 9) with control (rate ratio for recovery, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.32; P = 0.03).

Marconi (2020) (COV-BARRIER trial) performed a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, phase 3 trial, which was conducted in 12 countries in Asia, Europe, North America and South America. They evaluated effectiveness of baricitinib 4mg during 14 days, compared with placebo in hospitalized adults with symptomatic COVID-19 with ≥ 1 inflammatory marker. In total 1525 were included as they met the criteria (i.e., at least 18 years of age, hospitalised with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, evidence of pneumonia or active and symptomatic COVID-19, and with at least one elevated inflammatory marker (C-reactive protein, D-dimer, lactate dehydrogenase, or ferritin). These patients were randomized to receive baricitinib (n=764) or placebo (n=761), both in addition to standard of care (i.e., local clinical practice for COVID-19 management, which could include corticosteroids (91% of the patients used dexamethasone), antivirals, or both; dexamethasone use was permitted as described in the RECOVERY trial). The mean age was 58 years, and 63% were male. The length of the follow-up was 28 days. The following outcome measures were reported; mortality, and duration of hospitalization. The composite primary endpoint was the proportion who progressed to high-flow oxygen, non-invasive ventilation, invasive mechanical ventilation, or death by day 28, assessed in the intention-to-treat population. Overall, 27·8% of participants receiving baricitinib and 30.5% receiving placebo progressed to meet the primary endpoint (odds ratio 0.85 (95% CI 0.67 to 1.08), p=0.18), with an absolute risk difference of –2.7 percentage points (95% CI –7.3 to 1.9).

Murugesan (2021) performed an open-label randomized study to test efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in hospitalized patients with mild to moderate COVID-19. The study was conducted in India. Hospitalized patients in the age group of 18 - 65 years, diagnosed positive for SARS-CoV2 infection by RT-PCR and radiological imaging (Chest X-ray or CT scan) confirmed pneumonia with lower respiratory tract infection features indicating moderate pneumonia, were randomized to receive oral tofacitinib (10 mg PO BID for 14 days) and standard of care (N=50) or standard of care alone (N=50), which included e.g. remdesivir (98%), and corticosteroids (dexamethasone 85%, methylprednisolone 15%). The mean age was 58 years, and 63% were male. The length of the follow-up was 28 days. Primary outcomes were the proportion of patients not requiring any form of mechanical ventilation or high flow oxygen or ECMO at day 7 or mortality. The proportion of population requiring oxygen supplementation was similar in both the groups (28% in the tofacitinib group, 26% in the control group, P=0.82). There was no mortality in either group.

Table 1. Overview of RCTs comparing JAK inhibitors with standard care in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

|

Author |

Disease severity, based on need for respiratory support* |

Sample size |

Intervention |

Control |

|

Cao, 2020 |

Mixed moderate/severe, not further specified. |

I: N=20 C: N=21 Total: N=41 |

Patients allocated to the active drug received an oral dose of 5mg ruxolitinib twice a day plus standard of care |

Placebo (100mg vitamin C) twice a day plus standard-of-care. |

|

Ely, 2022 Critically ill cohort not included in the COV-BARRIER trial |

Severe disease: I: 100% C: 100% |

I: N=51 C: N=50 Total: N=101 |

Patients allocated to the active drug received baricitinib 4 mg crushed for nasogastric tube delivery (or given orally when feasible) and given once daily for up to 14 days or until discharge from hospital, whichever occurred first. |

Placebo. |

|

Guimarães, 2021 STOP-COVID trial |

Mixed mild to severe: I: mild: 23.6% moderate: 63.2% severe: 13.2% C: mild: 25.5% moderate: 63.2% severe: 12.4% (Defined by NIAID ordinal scale) |

I: N=144 C: N=145 Total: N=289 |

Patients allocated to the active drug received an oral dose of 10 mg tofacitinib twice daily for up to 14 days or until hospital discharge, whichever was earlier. |

Oral placebo twice daily. |

|

Kalil, 2020 ACTT-2 trial |

Mixed mild to severe: I: mild: 13.6% moderate: 55.9% severe: 30.5% C: mild: 13.9% moderate: 53.5% severe: 32.8%

Need for supplemental oxygen, mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation were criteria for inclusion. |

I: N=515 C: N=518 Total: N=1033 |

Patients allocated to the active drug received remdesivir and baricitinib: 4-mg daily dose (either orally or through a nasogastric tube) for 14 days or until hospital discharge or death. |

Remdesivir and placebo. |

|

Marconi, 2021 COV-BARRIER trial |

Mixed mild to severe: I: mild: 12% moderate: 64% severe: 24% C: mild: 13% moderate: 62% severe: 25% |

I: N=764 C: N=761 Total: N=1525 |

Patient allocated to the active drug received a dose of baricitinib 4 mg/day (oral) for up to 14 days or until hospital discharge; 2 mg/day if eGFR at baseline was 30-60 mL/min per 1.73 m².

|

Placebo. |

|

Murugesan, 2021 |

Mild to moderate, not further specified |

I: N=50 C: N=50 Total: N=100 |

Patients allocated to the active drug received oral tofacitinib, 10 mg PO BID for 14 days plus standard of care. |

Standard of care treatment alone. |

*Disease severity categories:

- mild disease (no supplemental oxygen);

- moderate disease (supplemental oxygen: low flow oxygen, non-rebreathing mask);

- severe disease (supplemental oxygen: high flow oxygen [high flow nasal cannula (HFNC)/Optiflow], continuous positive airway pressure [CPAP], non-invasive ventilation [NIV], mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [ECMO or ECLS]).

N: Total sample size; I: Intervention; C: Control

Results – Hospitalized patients

Since the number of studies and the number of patients included was relatively limited, we report all outcomes for the different JAK inhibitors combined. Also conclusions were reported for all JAK inhibitors combined.

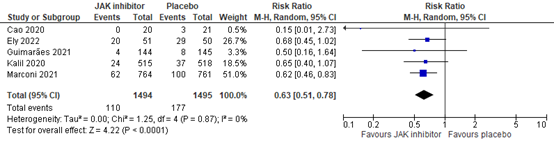

Mortality (crucial)

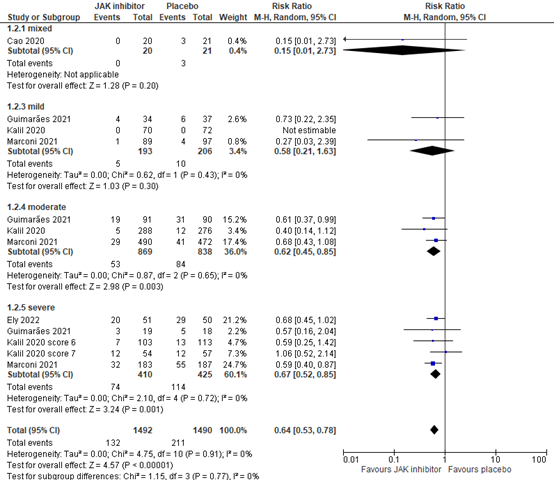

Five studies reported mortality at 28 days. In all hospitalized patients with COVID-19, the pooled 28-day mortality in the JAK inhibitor group was 110/1494 (7.4%), compared to 177/1495 (11.8%) in the control group. The pooled risk ratio (RR) was 0.63 with a 95% confidence interval (CI) from 0.51 to 0.78, in favour of the intervention group (figure 1). The pooled risk difference (RD) was -0.041 (95% CI -0.068 to 0.014), in favour of the intervention group. This is considered clinically relevant. Murugesan (2021) did not report mortality at 28 days, but found no mortality in either group (both N=50) at day 14. Figure 2 presents mortality grouped by disease severity at baseline. Of note, there is a slight discrepancy in the reported patient numbers for the subgroups (figure 2) and the total study populations (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Mortality (28-30days) in hospitalized patients

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Figure 2: Mortality (28-30days) in hospitalized patients by disease severity

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for all outcomes was based on randomized studies and therefore starts at high. For the outcome mortality, the level of evidence was downgraded by 1 level to moderate because the pooled confidence interval crossed the limit of clinical decision making (imprecision, -1).

Extensive respiratory support (crucial)

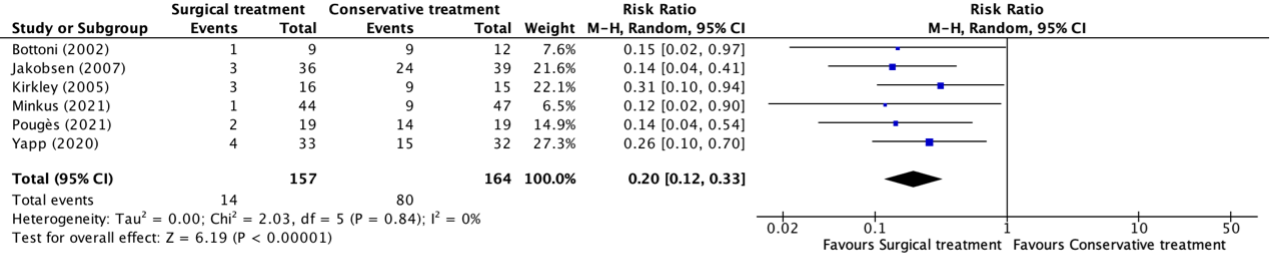

Three studies reported the need for invasive respiratory support (invasive mechanical ventilation or EMCO, NIAID score 7). In hospitalized patients with COVID-19, the pooled need for mechanical respiratory support in the JAK inhibitor group was 53/625 (8.5%), compared to 82/627 (13.1%) in the control group. The pooled RR was 0.66 (95% CI 0.48 to 0.91) in favour of the intervention group (figure 3).

The pooled risk difference (RD) was -0.042 (95% CI -0.085 to 0.001), in favour of the intervention group. This is not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 3: Need for extensive respiratory support in hospitalized patients

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval. From the study by Guimarães (2021, STOP-COVID trial), values at day 14 were used.

Marconi (2021) did not report need for respiratory support in the COV-BARRIER trial, but reported the number of ventilator-free days, and found least square means (standard error) of 24.5 (0.39) days for the baricitinib group (n=764) versus 23.7 (0.39) in the placebo group (n=761). Similarly, Ely (2022) reported a mean (standard error) ventilator-free days of 8.1 (10.2) in the baricitinib group versus 5.5 (8.4) in the placebo group (P=0.21).

Three studies reported the need for non-invasive ventilation or high-flow oxygen devices (NIAID score 6). In the STOP-COVID trial, 1/144 patients (0.7%) in the JAK inhibitor treated group needed non-invasive ventilation versus 6/145 (4.1%) in the placebo group. In the ACTT-2 trial, 70/358 (19.6%) patients treated with JAK inhibitors needed non-invasive ventilation or high-flow oxygen versus 82/348 (23.6%) in the placebo group. Cao (2020) reported 2/20 (10%) patients in the JAK group who needed non-invasive respiratory support versus 4/21 (19.0%) in the placebo group. Taken together, 73/522 (14.0%) patients receiving JAK inhibitors needed non-invasive ventilation versus 92/514 (17.9%) in the placebo group. The pooled RR was 0.77 (95% CI 0.59 to 1.02) in favour of the intervention group (figure 3). The pooled RD was -0.037 (95% CI -0.067 to 0.007) in favour of the intervention group. This is not considered clinically relevant.

Three studies reported need for supplemental oxygen (NIAID score 5). The STOP-COVID trial by Guimarães (2021) reported 7/144 (4.9%) patients receiving supplemental oxygen through low-flow devices of at day 14 in the tofacitinib group, versus 6/145 (4.1%) in the placebo group in patients with mild to severe COVID-19. The ACTT-2 trial (Kalil, 2020) reported 16/70 (22.9%) patients receiving new use of oxygen during the trial in the baricitinib group versus 29/72 (40.3%) in the placebo group (both groups also received remdesivir) in patients with mild to severe COVID-19. Murugesan reported that the proportion of population requiring oxygen supplementation (not further specified) was similar in both groups (28% in the tofacitinib group versus 26% in the control group, P=0.82).

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for all outcomes was based on randomized studies and therefore starts at high. For the outcome need for extensive respiratory support, the level of evidence was downgraded with 2 levels to LOW because the confidence interval crossed the limit of clinical decision making and because number of included patients was limited (both imprecision, -2).

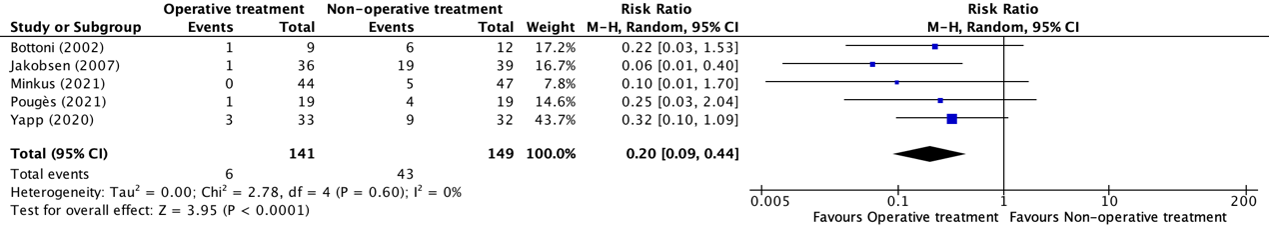

Duration of hospitalization (important)

Five studies reported hospital length of stay. The mean difference was -1.06 days, with a 95% CI from -1.81 to -0.31 in favour of JAK inhibitor treatment (figure 4). The difference is not considered clinically relevant. Murugesan did not report the data, but stated that there were no differences in duration of hospitalization between the groups.

Figure 4: Duration of hospitalization in hospitalized patients

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for all outcomes was based on randomized studies and therefore starts at high. For the outcome hospital length of stay, the level of evidence was downgraded with 2 levels to LOW due to conflicting results (inconsistency, -1), and due to the limited number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

Time to clinical improvement (important)

Three studies reported time to recovery. Marconi (2021) reported a median (95% CI) time to recovery (NIAID-OS score of 1-3) of 10.0 (9.0-11.0) days for baricitinib versus 11.0 (10.0-12.0) for placebo in 1525 hospitalized patients with mild to severe COVID-19. The difference was not considered clinically relevant.

Kalil (2020) reported median (95% CI) time to recovery (the first day, on which a patient attained category 1, 2, or 3 on the eight-category ordinal scale) for baricitinib versus placebo (both groups included additional remdesivir treatment), and found 7 (6-8) versus 8 (7-9) for all 1033 hospitalized patients with COVID-19, 5 (4-6) versus 4 (4-6) in 142 hospitalized patients with mild COVID-19, 5 (5-6) versus 6 (5-6) in 564 hospitalized patients with moderate COVID-19, and 10 (9-13) versus 18 (13-21) in 216 hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19. Only for the last category, the difference was considered clinically relevant. For patients with severe COVID-19 receiving invasive mechanical ventilation or EMCO at baseline, time to recovery could not be estimated.

Ely (2022) investigated time to recovery, but this was not reported at 28 days follow-up. There was no significant difference in the proportion of participants who had recovered at day 60 in the baricitinib group compared with the placebo group: 47% versus 32%.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for all outcomes was based on randomized studies and therefore starts at high. For the outcome clinical improvement, the level of evidence was downgraded with 1 level to MODERATE due to the limited number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

Non-hospitalized patients

No randomized studies were found that compared JAK inhibitor treatment with placebo treatment in non-hospitalized patients.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effectivity of Januskinase (JAK) inhibitor treatment compared to treatment without a Januskinase (JAK) inhibitor in patients with COVID-19?

PICO

PICO 1

P: hospitalized with COVID-19 (subgroups mild, moderate, severe)

I: JAK inhibitor (systemic) + standard care

C: standard care only / placebo treatment + standard care

O: 28-30 day mortality (if not available, any other reports of mortality), extensive respiratory support, duration of hospitalization, time to clinical improvement

PICO 2

P: non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19

I: JAK inhibitor (systemic) + standard care

C: standard care only / placebo treatment + standard care

O: 28-30 day mortality (if not available, other follow-up), respiratory support, hospitalization, time to clinical improvement

Relevant outcome measures

PICO 1: For hospitalized COVID-19 patients, mortality and need for extensive respiratory support were considered as crucial outcome measures for decision making. Duration of hospitalization, and time to clinical improvement were considered as important outcome measures for decision making.

PICO 2: For non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients, mortality was considered as a critical outcome measure for decision making. Hospitalization, respiratory support and time to clinical improvement were considered as important outcome measures for decision making.

Extensive respiratory support was defined as high flow nasal cannula (HFNC)/Optiflow, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), non-invasive ventilation (NIV), mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO or ECLS).

The working group defined 3% points absolute difference as a minimal clinically important difference for mortality (resulting in a NNT of 33), 3 days difference for duration of hospitalization and time to clinical improvement, 5% points absolute difference need for respiratory support and ICU admission (resulting in a NNT of 20).

The results of studies in non-hospitalized and hospitalized patients are summarized separately. Studies of hospitalized patients were categorized based on the respiratory support that was needed at baseline (preferably based on patient inclusion/exclusion criteria; otherwise on baseline characteristics). The following categories were used:

- mild disease (no supplemental oxygen);

- moderate disease (supplemental oxygen: low flow oxygen, non-rebreathing mask);

- severe disease (supplemental oxygen: high flow oxygen [high flow nasal cannula (HFNC)/Optiflow], continuous positive airway pressure [CPAP], non-invasive ventilation [NIV], mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [ECMO or ECLS]).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until March 31, 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 686 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: randomized controlled trial with at least 10 patients per arm, peer reviewed and published in indexed journal or pre-published, comparing treatment with a JAK inhibitor with placebo or usual care in adult patients with COVID-19.

The systematic literature search resulted in 82001 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic review or randomized controlled trials. Eventually, six studies were included.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were conducted using Review Manager (RevMan) software 5.4. For dichotomous outcomes, Mantel Haenszel random‐effects risk ratios (RRs) and risk differences (RDs) were calculated. For continuous outcomes, a random‐effects mean difference (MD) weighted by the inverse variance was calculated. The random-effects model estimates the mean of a distribution of effects.

Results

Six studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Five studies compared a JAK inhibitor with placebo in hospitalized adult COVID-19 patients, the study of Murugesan (2021) was an open-label trial. Important study characteristics and results are summarized below. Studies are presented in alphabetical order, only results of the primary outcome is reported in the summary of literature. Additionally, studies are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized separately in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Bechman K, Subesinghe S, Norton S, Atzeni F, Galli M, Cope AP, Winthrop KL, Galloway JB. A systematic review and meta-analysis of infection risk with small molecule JAK inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019 Oct 1;58(10):1755-1766. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez087. PMID: 30982883.

- Bronte V, Ugel S, Tinazzi E, Vella A, De Sanctis F, Canè S, Batani V, Trovato R, Fiore A, Petrova V, Hofer F, Barouni RM, Musiu C, Caligola S, Pinton L, Torroni L, Polati E, Donadello K, Friso S, Pizzolo F, Iezzi M, Facciotti F, Pelicci PG, Righetti D, Bazzoni P, Rampudda M, Comel A, Mosaner W, Lunardi C, Olivieri O. Baricitinib restrains the immune dysregulation in patients with severe COVID-19. J Clin Invest. 2020 Dec 1;130(12):6409-6416. doi: 10.1172/JCI141772. PMID: 32809969; PMCID: PMC8016181.

- Cao Y, Wei J, Zou L, Jiang T, Wang G, Chen L, Huang L, Meng F, Huang L, Wang N, Zhou X, Luo H, Mao Z, Chen X, Xie J, Liu J, Cheng H, Zhao J, Huang G, Wang W, Zhou J. Ruxolitinib in treatment of severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A multicenter, single-blind, randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020 Jul;146(1):137-146.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.019. Epub 2020 May 26. PMID: 32470486; PMCID: PMC7250105.

- Ely EW, Ramanan AV, Kartman CE, de Bono S, Liao R, Piruzeli MLB, Goldman JD, Saraiva JFK, Chakladar S, Marconi VC; COV-BARRIER Study Group. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib plus standard of care for the treatment of critically ill hospitalised adults with COVID-19 on invasive mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: an exploratory, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2022 Feb 3:S2213-2600(22)00006-6. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00006-6. Epub ahead of print. Erratum in: Lancet Respir Med. 2022 Feb 11;: PMID: 35123660; PMCID: PMC8813065

- Gatti M, Turrini E, Raschi E, Sestili P, Fimognari C. Janus Kinase Inhibitors and Coronavirus Disease (COVID)-19: Rationale, Clinical Evidence and Safety Issues. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2021 Jul 28;14(8):738. doi: 10.3390/ph14080738. PMID: 34451835; PMCID: PMC8401109.

- Guimarães PO, Quirk D, Furtado RH, Maia LN, Saraiva JF, Antunes MO, Kalil Filho R, Junior VM, Soeiro AM, Tognon AP, Veiga VC, Martins PA, Moia DDF, Sampaio BS, Assis SRL, Soares RVP, Piano LPA, Castilho K, Momesso RGRAP, Monfardini F, Guimarães HP, Ponce de Leon D, Dulcine M, Pinheiro MRT, Gunay LM, Deuring JJ, Rizzo LV, Koncz T, Berwanger O; STOP-COVID Trial Investigators. Tofacitinib in Patients Hospitalized with Covid-19 Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2021 Jul 29;385(5):406-415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2101643. Epub 2021 Jun 16. PMID: 34133856; PMCID: PMC8220898.

- Honda S, Harigai M. The safety of baricitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2020 May;19(5):545-551. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2020.1743263. Epub 2020 Mar 21. PMID: 32174196.

- Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, Tomashek KM, Wolfe CR, Ghazaryan V, Marconi VC, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Hsieh L, Kline S, Tapson V, Iovine NM, Jain MK, Sweeney DA, El Sahly HM, Branche AR, Regalado Pineda J, Lye DC, Sandkovsky U, Luetkemeyer AF, Cohen SH, Finberg RW, Jackson PEH, Taiwo B, Paules CI, Arguinchona H, Erdmann N, Ahuja N, Frank M, Oh MD, Kim ES, Tan SY, Mularski RA, Nielsen H, Ponce PO, Taylor BS, Larson L, Rouphael NG, Saklawi Y, Cantos VD, Ko ER, Engemann JJ, Amin AN, Watanabe M, Billings J, Elie MC, Davey RT, Burgess TH, Ferreira J, Green M, Makowski M, Cardoso A, de Bono S, Bonnett T, Proschan M, Deye GA, Dempsey W, Nayak SU, Dodd LE, Beigel JH; ACTT-2 Study Group Members. Baricitinib plus Remdesivir for Hospitalized Adults with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021 Mar 4;384(9):795-807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2031994. Epub 2020 Dec 11. PMID: 33306283; PMCID: PMC7745180.

- Marconi VC, Ramanan AV, de Bono S, Kartman CE, Krishnan V, Liao R, Piruzeli MLB, Goldman JD, Alatorre-Alexander J, de Cassia Pellegrini R, Estrada V, Som M, Cardoso A, Chakladar S, Crowe B, Reis P, Zhang X, Adams DH, Ely EW; COV-BARRIER Study Group. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib for the treatment of hospitalised adults with COVID-19 (COV-BARRIER): a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021 Aug 31:S2213-2600(21)00331-3. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00331-3. Epub ahead of print. Erratum in: Lancet Respir Med. 2021 Oct;9(10):e102. PMID: 34480861; PMCID: PMC8409066.

- Murugesan H, Cs G, Nasreen HS, Santhanam S, M G, Ravi S, Es SS. An Evaluation of Efficacy and Safety of Tofacitinib, A JAK Inhibitor in the Management of Hospitalized Patients with Mild to Moderate COVID-19 - An Open-Label Randomized Controlled Study. J Assoc Physicians India. 2022 Dec;69(12):11-12. PMID: 35057599.

- Peng L, Xiao K, Ottaviani S, Stebbing J, Wang YJ. A real-world disproportionality analysis of FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) events for baricitinib. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2020 Nov;19(11):1505-1511. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2020.1799975. Epub 2020 Jul 31. PMID: 32693646.

- Richardson P, Griffin I, Tucker C, Smith D, Oechsle O, Phelan A, Rawling M, Savory E, Stebbing J. Baricitinib as potential treatment for 2019-nCoV acute respiratory disease. Lancet. 2020 Feb 15;395(10223):e30-e31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30304-4. Epub 2020 Feb 4. Erratum in: Lancet. 2020 Jun 20;395(10241):1906. PMID: 32032529; PMCID: PMC7137985.

- van de Veerdonk FL, Giamarellos-Bourboulis E, Pickkers P, Derde L, Leavis H, van Crevel R, Engel JJ, Wiersinga WJ, Vlaar APJ, Shankar-Hari M, van der Poll T, Bonten M, Angus DC, van der Meer JWM, Netea MG. A guide to immunotherapy for COVID-19. Nat Med. 2022 Jan;28(1):39-50. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01643-9. Epub 2022 Jan 21. PMID: 35064248.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Baricitinib (selective and reversible Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) and 2 (JAK2) inhibitor) |

|||||||

|

Ely, 2022 |

Type of study: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre phase 3 trial

Setting: hospital-based, between December 23, 2020, and April 10, 2021

Country: 18 hospitals in Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and the USA.

Source of funding: Eli Lilly and Company. The funder of the study had a role in study design, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the report, but had no role in data collection.

Conflicts of interest: Several authors received research grants, honoraria or research support from the sponsor. Several authors are employees and shareholders of the sponsor. Several authors served as an advisory board member, speaker or consultant, or scientific advisor of the sponsor. |

hospitalised adults with severe COVID-19

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Randomized: N = 101 Intervention: N = 51 Control: N = 50

Important characteristics: Age, mean (SD): I: 58.4 y (12.4) C: 58.8 y (15.2)

Sex, n/N (%) male: I: 25/51 (49%) C: 30/50 (60%)

Disease severity score 7: (NIAID-OS score) I: 100% C: 100%

Groups were comparable at baseline. |

Baricitinib 4 mg

crushed for nasogastric tube delivery (or given orally when feasible) and given once daily for up to 14 days or until discharge from hospital, whichever occurred first.

Participants assigned to baricitinib with baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 30 to less than 60 mL/min per 1·73 m² received baricitinib 2 mg or matched placebo. If eGFR decreased to 30 to less than 60 mL/min per 1·73 m² after randomisation, patients received baricitinib 2 mg until eGFR returned to 60 mL/min per 1·73 m² or greater. |

Placebo

All participants received standard of care in keeping with local clinical practice for COVID-19 management, which could include concomitant medications such as corticosteroids, antivirals, and other treatments, including vasopressors. Prophylaxis for venous thromboembolic events per local practice was required for all participants unless contraindicated. |

Length of follow-up: 28 days

Loss-to-follow-up or incomplete data: Intervention: Four participants (7.8%) discontinued from the trial after transfer to another hospital; they were included in the intention-to-treat population, with all available information used to inform the mortality and safety analyses. Control: 2 participants (4.0%), 1 lost to follow-up and 1 withdrawal.

|

All-cause mortality at day 28 I: 20/51 (39%) C: 29/50 (58%)

All-cause mortality at day 60 I: 23/51 (45%) C: 31/50 (62%)

Ventilator-free days mean (SD) at 28 days C: 5.5 (8.4)

Duration of hospitalisation (in days), mean (SD) I: 23.7 (7.1) C: 26.1 (3.9)

Time to recovery at day 28 I: N/A C: N/A

|

Authors’ conclusion: treatment with baricitinib plus standard of care (including use of corticosteroids) in critically ill patients with COVID-19 who were receiving IMV or ECMO at enrolment resulted in reduction in all-cause mortality at 28 days and 60 days compared with placebo plus standard of care in this exploratory trial. |

|

Marconi, 2021 |

Type of study: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre phase 3 trial

Setting: hospital-based, between June 11 2020 and January 15 2021

Country: 101 centres from 12 countries in Asia, Europe, North America and South America

Source of funding: Eli Lilly and Company. The trial was designed jointly by consultant experts and representatives of the sponsor. Data were collected by investigators and analysed by the sponsor. All authors participated in the interpretation of the data analysis, draft, and final manuscript review, and provided critical comment, including the decision to submit the manuscript for publication with medical writing support provided by the sponsor. The authors had full access to the data and authors from the sponsor verified the veracity, accuracy, and completeness of the data and analyses as well as the fidelity of this report to the protocol.

Conflicts of interest: Several authors received research grants, honoraria or research support from the sponsor. Several authors are employees and shareholders of the sponsor. Several authors served as an advisory board member, speaker or consultant, or scientific advisor of the sponsor. |

hospitalised adults with COVID-19

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Randomized: N = 1525 Intervention: N = 764 Control: N = 761

Important characteristics: Age, mean (SD): I: 57.8 y (14.3) C: 57.5 y (13.8)

Sex, n/N (%) male: I: 490/764 (64%) C: 473/761 (62%)

Disease severity, mean (SD): Defined by NIAID-OS score I: score 4: 89/762 (12%) score 5: 490/762 (64%) score 6: 183/762 (24%) C: score 4: 97/756 (13%) score 5: 472/756 (62%) score 6: 187/756 (25%)

Groups were comparable at baseline. |

baricitinib 4 mg/day (oral) for up to 14 days or until hospital discharge; 2 mg/day if eGFR at baseline was 30-60 mL/min per 1.73 m² |

placebo |

Length of follow-up: 28 days

Loss-to-follow-up or incomplete data: Intervention: N = 120 (15.7%) Reasons

Control: N = 157 (20.6%) Reasons

other (n = 15) |

Prespecified subgroup analyses for the primary and selected key secondary endpoints evaluated treatment effect across the following subgroups: baseline severity, baseline systemic corticosteroid use, baseline remdesivir use, geographical region, sex, disease duration at baseline, and age at baseline.

Clinical outcomes Mortality All-cause mortality at day 28 I: 62/764 (8%) C: 100/761 (13%) HR: 0.57 (0.41-0.78)

Duration of hospitalisation in days LSM (SE) I: 12.9 (0.40) C: 13.7 (0.40) LSMD: -0.76 (-1.6-0.0)

Time to symptom resolution Time to recovery in days Median (95% CI) I: 10.0 (9.0-11.0) C: 11.0 (10.0-12.0) RR: 1.11 (0.99-1.24)

Likelihood of overall improvement on the NIAID-OS score Day 4: OR: 1.21 (1.00-1.47) Day 7: OR: 1.25 (1.04-1.49) Day 10: OR: 1.17 (0.97-1.41) Day 14: OR: 1.28 (1.05-1.56)

≥ 1-point improvement on the NIAID-OS score or live discharge from hospital Day 4: OR: 1.26 (0.98-1.61) Day 7: OR: 1.18 (0.95-1.46) Day 10: OR: 1.07 (0.86-1.34) Day 14: OR: 1.21 (0.95-1.55)

Change from baseline in O2 saturation from < 94% to ≥ 94% Day 4: OR: 1.20 (0.86-1.69) Day 7: OR: 0.97.18 (0.95-1.46) Day 10: OR: 1.07 (0.86-1.34) Day 14: OR: 1.21 (0.95-1.55)

Respiratory support Number of ventilator-free days LSM (SE) I: 24.5 (0.39) C: 23.7 (0.39) LSMD: 0.75 (-0.0-1.5)

Progression to high-flow O2, non-invasive ventilation, invasive mechanical ventilation, or death at day 28 – primary outcome Population 1* I: 27.8% C: 30.5% OR: 0.85 (95% CI: 0.67-1.08)

Population 2* I: 28.9% C: 27.1% OR: 1.12 (95% CI: 0.58-2.16)

Safety Treatment-emergent adverse event I: 334 (45%) C: 334 (44%)

Serious adverse events I: 110/750 (15%) C: 135/752 (18%)

Virological outcomes Viral clearance Not reported. |

Definitions: * Population 1 includes all randomised participants. Population 2 includes participants who, at baseline, required O2 supplementation and were not receiving dexamethasone or other systemic corticosteroids for the primary study condition.

Remarks: -

Authors’ conclusion: Although there was no significant reduction in the frequency of disease progression overall, treatment with baricitinib in addition to standard of care (including dexamethasone) had a similar safety profile to that of standard of care alone, and was associated with reduced mortality in hospitalised adults with COVID-19. |

|

Kalil, 2020 |

Type of study: Double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT

Setting: 67 trials sites in 8 countries

Country: USA (55 sites), Singapore (4 sites), South Korea (2 sites), Mexico (2 sites), Japan (1 site), Spain (1 site), UK (1 site) and Denmark (1 site).

Source of funding: The trial site in South Korea received funding from the Seoul National University Hospital. Support for the London International Coordinating Centre was also provided by the United Kingdom Medical Research Council.

|

Hospitalized adults with COVID-19

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: N = 1033 Intervention: N = 515 Control: N = 518

N intension-to-treat population 706 patients with moderate disease (ordinal scale 4 or 5) and 327 patients with severe disease (ordinal scale 6 or 7).

Important characteristics: Age, mean (SD): I: 55 y (15.4) C: 55.8 y (16.0)

Sex, n/N (%) male: I: 319/515 (61.9%) C: 333/518 (64.3%)

Disease severity, N (%): Classified as moderate or severe Moderate I: 358/515 (69.5%) C: 348/518 (67.2%) Severe I: 157/515 (30.5%) C: 170/518 (32.8%)

Baseline score on ordinal scale 4 = Hospitalized, not requiring supplemental oxygen, requiring ongoing medical care I: 70/515 (13.6%) C: 72/518 (13.9%)

5 = Hospitalized, requiring supplemental oxygen I: 288/515 (55.9%) C: 276/518 (53.5%)

6 = Hospitalized, receiving noninvasive ventilation or high-flow oxygen devices I: 103/515 (20.0%) C: 113/518 (21.8%)

7 = Hospitalized, receiving invasive mechanical ventilation or EMCO I: 54/515 (10.5%) C: 57/518 (11.0%)

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Remdesivir + Baricitinib

Remdesivir: intraveneously as a 200-mg loading dose on day 1, followed by a 100-mg maintenance dose administered daily on days 2 through 10 or until hospital discharge or death Baricitinib: 4-mg daily dose (either orally) or through a nasogastric tube) for 14 days or until hospital discharge or death.

|

Remdesivir + placebo

Remdesivir: intraveneously as a 200-mg loading dose on day 1, followed by a 100-mg maintenance dose administered daily on days 2 through 10 or until hospital discharge or death Placebo: matching oral placebo, administered according to same schedule as active drug. |

Length of follow up: 29 days

Loss to follow-up: I: 40/515 (7.8%) Reasons: not reported

C: 41/518 (7.9%) Reasons: not reported |

(Overall) Mortality over first 14 days HR= 0.54 (0.23 to 1.28) I: N = 8/515 (7.0%) C: N = 15/518 (2.9%)

Subgroups: baseline ordinal score of 4 HR= Not estimable I: N = 0/70 (0%) C: N = 0/72 (0%)

baseline ordinal score of 5 HR= 0.73 (95% CI= 0.16 to 3.26) I: N = 3/288 (1.0%) C: N = 4/276 (1.4%)

baseline ordinal score of 6 HR= 0.21 (95% CI= 0.02 to 1.80) I: N = 1 /103 (1.0%) C: N = 5/113 (4.4%) baseline ordinal score of 7 HR= 0.69 (95% CI= 0.19 to 2.44) I: N = 4/54 (7.4%) C: N = 6/57 (10.5%)

(Overall) mortality over entire trial period (28 days) HR= 0.65 (95% CI= 0.39 to 1.09) I: N = 24/515 (4.7%) C: N = 37/518 (7.1%)

Subgroups: baseline ordinal score 4 HR= Not estimable I: N = 0/70 0(%) C: N = 0/72 (0%) baseline ordinal score 5 HR= 0.40 (95% CI= 0.14 to 1.14) I: N = 5/288 (1.7%) C: N = 12/276 (4.3%) baseline ordinal score 6 HR= 0.55 (95% CI= 0.22 to 1.38) I: N = 7/103 (6.8%) C: N = 13/113 (11.5%) baseline ordinal score 7 HR= 1.00 (95% CI= 0.45 to 2.22) I: N = 12/54 (22.2%) C: N= 12/57 (21.1%)

(Overall) Median time to recovery, in days; (rate ratio for recovery [95% CI] I: 7 days C: 8 days Rate ratio for recovery= 1.16 (95% CI= 1.01 to 1.32) p=0.03

Subgroups: baseline ordinal score 4 I: 5 (4to 6) days C: 4 (4 to 6) days Rate ratio for recovery= 0.88 (95% CI= 0.63 to 1.23)

baseline ordinal score 5 I: 5 (5 to 6) days C: 6 (5 to 6) days Rate ratio for recovery= 1.17 (95% CI= 0.98 to 1.39)

baseline ordinal score 6 I: 10 (9 to 13) days C: 18 (13 to 21)days Rate ratio for recovery= 1.51 (95% CI= 1.10 to 2.08)

baseline ordinal score 7 I: Not estimable (25 to NE) C: Not estimable (26 to NE) Rate ratio for recovery= 1.08 (95% CI= 0.59 to 1.97)

(Overall) Improvement in clinical status at day 15 OR= 1.3 (95% CI= 1.0 to 1.6)

Subgroups: baseline ordinal score 4 OR= 0.6 (95% CI= 0.3 to 1.1) baseline ordinal score 5 OR= 1.2 (95% CI= 0.9 to 1.6) baseline ordinal score 6 OR= 2.2 (95% CI= 1.4 to 3.6) baseline ordinal score 7 OR= 1.7 (95% CI= 0.8 to 3.4)

Median duration of initial hospitalization IQR) in days (with imputation of data for those who died) I: 8 (5 to 15) days C: 8 (5 to 20) days Rate ratio= 0.0 (95% CI -1.1 to 1.1)

Median duration of initial hospitalization IQR) in days (among those who did not die) I: 8 (5 to 13) days C: 8 (5 to 15) days Rate ratio= 0.0 (-1.0 to 1.0)

% patients re-hospitalized (95% CI) I: 3% (2 to 5) C: 2% (1 to 4) Rate ratio= 1.0 (95% CI= -1.1 to 3.1)

New use of oxygen during trial I: 16/70 (22.9%) C: 29/72 (40.3%)

New use of noninvasive ventilation or high-flow oxygen during trial I: 70/358 (19.6%) C: 82/348 (23.6%)

New use of mechanical ventilation or ECMO during trial I: 46/461 (10.0%) C: 70/461 (15.2%)

Time to recovery Median time in days (95% CI) All patients I: 7 (6-8) n=515 C: 8 (7-9) n=518

Subgroups: baseline ordinal score 4 I: 5 (4-6) n=70 C: 4 (4-6) n=72

baseline ordinal score 5 I: 5 (5-6) n=288 C: 6 (5-6) n=276

baseline ordinal score 6 I: 10 (9-13) n=103 C: 18 (13-21) n=113

baseline ordinal score 7 not estimable

Median days receiving oxygen if receiving oxygen at baseline (IQR) (with imputation of data for those who died) I: 10 (4 to 27) days C: 12 (4 to 28) days Rate ratio= -2.0 (95% CI= -5.2 to 1.2)

Median days receiving oxygen if receiving oxygen at baseline (IQR) (among those who did not die) I: 9 (4 to 23) days C: 10 (4 to 28) days Rate ratio= -1.0 (95% CI= -3.5 to 1.5)

Median days of mechanical ventilation or ECMO during trial if receiving these interventions at baseline IQR) (with imputation of data for those who died) I: 20 (9 to 28) days C: 24 (19 to 28) days Rate ratio= -4.0 (95% CI= -10.1 to 2.1)

Median days of mechanical ventilation or ECMO during trial if receiving these interventions at baseline IQR) (among those who did not die) I: 13 (7 to 24) days C: 16 (6 to 28) days Rate ratio= -2.0 (95% CI= -11.4 to 7.4)

Adverse events (grade 3 or 4) I: N = 207 (40.7%) C: N = 238 (46.8%)

Serious adverse events I: N = 81/515 (15.7%) C: N = 107/518 (20.7%)

Viral clearance Not reported. |

Definitions: Baseline score on ordinal scale 4 = Hospitalized, not requiring supplemental oxygen, requiring ongoing medical care 5 = Hospitalized, requiring supplemental oxygen 6 = Hospitalized, receiving noninvasive ventilation or high-flow oxygen devices 7 = Hospitalized, receiving invasive mechanical ventilation or EMCO

Remarks: A total of 498 patients in the intervention group and 495 in the control group completed the trial through day 29, recovered or died.

Authors conclusion: Baricitinib plus remdesivir was superior to remdesivir alone in reducing recovery time and accelerating improvement in clinical status, notably among patients receiving high-flow oxygen or non-invasive mechanical ventilation. The combination was associated with fewer serious adverse events.

|

|

Nezulcitinib |

|||||||

|

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

|

Ruxolitinib (Janus kinase 1 and 2 inhibitor) |

|||||||

|

Cao, 2020b

|

Type of study: Multicenter, single-blind RCT

Setting: 42 patients were randomly assigned to treatment with either ruxolitinib or placebo, in the Tongji 139 hospital, No.1 hospital and the Third Xiangya hospital in China.

Country: Wuhan, China

Source of funding: Principal investigators who has no role in the study

|

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: N = 42

Important characteristics: Mean age: 63 years (58-68 year) Male gender: 58,5%

|

Oral intake of ruxolitinib 5mg twice a day plus standard-of-care (SoC)

SoC: antiviral therapy, supplemental oxygen, non-invasive and invasive ventilation, corticosteroid, antibiotic agents, vasopressor support, renal replacement therapy, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). |

Placebo (100mg vitamin C) twice a day with SoC |

Length of follow-up: 28 days

Loss-to-follow-up: N/a

|

Time to clinical improvement (improvement of 2 points on 7 point ordinal scale or hospital discharge) Patients treated with ruxolitinib had a numerically shorter median time to clinical improvement (12 days vs 15 days, P=0.147)

Clinical improvement rate No statistical differences were detected between groups

Time from randomization to lymphocyte recovery and to invasive mechanical ventilation Lymphocyte recovery: Ruxolitinib: 5 days Control group: 8 days (P=0,033)

Invasive mechanical ventilation: Time to invasive mechanical ventilation is not reported

Incidence: Ruxolitinib: 0 patients Control group: 3 patients

ICU admission (narrative/explorative) Ruxolitinib: 0 patients Control group: 3 patients

Time from randomization to discharge (d) Ruxolitinib: 17 (IQR 11-21) Control: 16 (IQR 11-20) P=0.941

Time from treatment initiation to death and virus clearance time 28-day overall mortality: Ruxolitinib: 0% Control group: 14,3%

Median time from randomization to death in control group: 15 days

Viral clearance defined as the time from randomization to the first day of at least 2 consecutive negative RT-PCR assays In days, median (IQR) I: 13 (5-16) n=20 C: 12 (3-16) n=21 P=0.6549

Adverse events up to day 28 (patients) Ruxolitinib: 7/20 (35%) Control: 6/21 (28.6%)

Serious adverse events up to day 28 (patients) Ruxolitinib: 0/20 (0%) Control: 4/21 (19%) |

General remarks:

Author conclusion: Ruxolitinib added to SoC treatment does not lead to significantly accelerated clinical improvement in severe patients with COVID-19.

As at Chest CT at D14 a significant faster improvement is reported in Ruxolitinib (90%) versus control group (61,9%), (P=0,0495), and no deaths occurred in the Ruxolitinib group, authors suggest further investigation in the effect of Ruxolitinib treatment on deterioration and death of COVID-19 patients |

|

Tofacitinib |

|||||||

|

Murugesan, 2021

|

Type of study: open-label RCT (pilot)

Setting: hospital-based, between October, 2020 and December 2020

Country: 1 hospital, Chennai, India

Source of funding: This trial was supported by Pfizer.

Conflicts of interest: Not reported. |

hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Randomized: N = 100

Intervention : N = 50 Control: N = 50

Important characteristics: Age, median (IQR): I: 47.0 (39.0-54.0) C: 46.0 (37.0-57.0)

Sex, n/N (%) male: I: 38/50 (76%) C: 36/50 (72%)

SpO2 at baseline, median (IQR): I: 96 (94-97) C: 97 (95-98)

CT-score at baseline, n(%) Grade 1 I: 15 (30%) C: 23 (46%)

Grade 2 I: 27 (54%)

Grade 3 I: 8 (16%) C: 5 (10%)

Groups comparable at baseline? Most of the patients in the control group had a lower CT score of grade-1, whereas most of the patients in the treatment group had higher CT-score of grade-2 and 3. |

Tofacitinib was administered in a dose of 10 mg PO BID for 14 days

+ standard of care

|

Standard of care included: Ceftriaxone, Enoxaparin, Heparin, Remdesivir, Dexamethasone, Methylprednisolone at the recommended dosing and supplementary oxygen wherever required |

Length of follow-up: 28 days

Loss-to-follow-up or incomplete data: Not reported |

Clinical outcomes Mortality There was no mortality in both groups at 14 days.

Duration of hospitalisation Not reported

Time to symptom resolution Not reported.

Respiratory support FiO2 N(%) I: 14 (28)% P=0.822

Safety Adverse events No adverse events were reported.

Virological outcomes Not reported

Also available: CRP levels, ferritin levels, D-Dimer levels, CBC, RFT, LFT and electrolytes levels of the participants |

Definitions: - Remarks:

Authors conclusion: Administering Tofacitinib at a 10 mg dose for a period of 14 days along with the standard of care treatment seems to have an added benefit of an anti-inflammatory response in patients with mild-to moderate COVID-19 infections.

|

|

Guimarães, 2021 |

Type of study: Randomized, placebo-controlled, blinded parallel-group clinical trial

Setting: Academic Research Organization of the Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein in São Paulo

Country: Brazil

Source of funding: The trial was sponsored by Pfizer and was designed and led by a steering committee that included academic investigators and representatives from Pfizer.

Conflicts of interest: Not reported.

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04469114

|

Hospitalized COVID-19 patients

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: N = 289 Intervention: 144 Control: 145

Important characteristics: Age, mean (SD): I: 55 y (14) C: 57 y (14)

Sex, n/N (%) female: I: 50/144 (34.7%) C: 51/145 (35.2%)

Disease severity, mean (SD): Defined by NIAID ordinal scale

4: hospitalized, not receiving supplemental oxygen but receiving ongoing medical care, Covid-19 related or otherwise I: 34/144 (23.6%) C: 37/145 (25.5%)

5: hospitalized, receiving supplemental oxygen through low-flow devices I: 91/144 (63.2%) C: 90/145 (62.1%)

6: hospitalized, receiving supplemental oxygen through high-flow devices C: 18/145 (12.4%)

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes.

|

Tofacitinib

Oral tofacitinib at a dose of 10 mg twice daily for up to 14 days or until hospital discharge, whichever was earlier. |

Placebo

Oral placebo at a dose of 10 mg twice daily for up to 14 days or until hospital discharge, whichever was earlier. |

Length of follow-up: 28 days.

Loss-to-follow-up: All the patients in both groups completed the 28-day follow-up or died. No patient was lost to follow-up or withdrew consent.

|

Clinical outcomes Mortality or respiratory failure through day 28 I: 26/144 (18.1%) C: 42/145 (29.0%) HR 0.63 (95% CI 0.41 to 0.97) P=0.04

Mortality through day 28 I: 4/144 (2.8%) C: 8/145 (5.5%) HR 0.49 (95% CI 0.15 to 1.63)

Duration of hospitalization Median length of initial hospitalization (IQR) in days I: 5.5 (3.0 to 8.25) C: 6.0 (3.0 to 11.0) HR 1.18 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.48)

Median length of initial hospitalization at the ICU (IQR) in days I: 5.0 (3.0 to 11.0) C: 5.0 (2.0 to 11.5) HR 1.11 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.70)

Median duration of mechanical ventilation (IQR) in days I: 12.5 (9.25 to 17.0) C: 12.0 (6.0 to 21.0) Difference in median: 1.00 (-7.0 to 7.0)

Time to symptom resolution Not reported.

Respiratory support Respiratory failure (1,2 or 3 on the 8-point NIAID ordinal scale of disease severity at day 28 1: not hospitalized, with no limitations on activities; I: 129/144 (89.6%) C: 119/145 (82.1%)

2: was not hospitalized but had limitation on activities or was receiving supplemental oxygen at home; I: 5/144 (3.5%) C: 10/145 (6.9%)

3: was hospitalized, without use of supplemental oxygen and no longer required ongoing medical care; I: 0/144 (0%) C: 1/145 (0.7%)

4: hospitalized, not receiving supplemental oxygen but receiving ongoing medical care, Covid-19 related or otherwise I: 0/144 (0%) C: 2/145 (1.4%)

5: hospitalized, receiving supplemental oxygen through low-flow devices I: 4/144 (2.8%) C: 1/145 (0.7%)

6: hospitalized, receiving supplemental oxygen through high-flow devices 7: hospitalized and receiving invasive mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) 8: died Respiratory support Respiratory failure (1,2 or 3 on the 8-point NIAID ordinal scale of disease severity at day 14 1: not hospitalized, with no limitations on activities; I: 110/144 (76.4%) C: 96/145 (66.2%)

2: was not hospitalized but had limitation on activities or was receiving supplemental oxygen at home; I: 11/144 (7.6%) C: 15/145 (10.3%)

3: was hospitalized, without use of supplemental oxygen and no longer required ongoing medical care; I: 1/144 (0.7%) C: 2/145 (1.4%)

4: hospitalized, not receiving supplemental oxygen but receiving ongoing medical care, Covid-19 related or otherwise I: 5/144 (3.5%) C: 6/145 (4.1%)

5: hospitalized, receiving supplemental oxygen through low-flow devices I: 7/144 (4.9%) C: 6/145 (4.1%)

6: hospitalized, receiving supplemental oxygen through high-flow devices 7: hospitalized and receiving invasive mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (EMMO) 8: died Status at day 14: Alive and not using mechanical ventilation or ECMO I: 135/144 (93.8%) C: 131/145 (90.3%) RR 1.04 (95% CI 0.97 to 1.12)

Alive and not hospitalized I: 121/144 (84.0%) C: 111/145 (76.6%) RR 1.11 (95% CI 0.99 to 1.24)

Status at day 28 Alive and not using mechanical ventilation or ECMO I: 139/144(96.5%) C: 133/145 (91.7%) 1.06 (95% CI 1.00 to 1.12)

Alive and not hospitalized I: 134/144 (93.1%) C: 129/145 (89.0%) RR 1.05 (95% CI 0.97 to 1.13)

Cured I: 134/144 (93.1%) C: 132/145 (91.0%) RR 1.03 (95% CI 0.95 to 1.10)

Safety Adverse events Any event I: 37/142 (26.1%) C: 32/142 (22.5%)

Serious adverse events I: 20/142 (14.1%) C: 17/142 (12.0%)

Acute respiratory failure I: 8/142 (5.6%) C: 5/142 (3.5%)

*All adverse events are specified in the original publication.

Virological outcomes Viral clearance Not reported. |

Definitions: ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

Remarks: - Cure refers to resolution of fever, cough, and need for ventilatory or oxygen support

Authors’ conclusion: In this trial, among hospitalized adult patients with Covid-19 pneumonia, tofacitinib led to a lower risk of death or respiratory failure through day 28 than placebo.

|

Risk of bias table for intervention studies

|

|

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2 (unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3 (unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3 (unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3 (unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4 (unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5 (unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6 (unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Baricitinib (selective and reversible Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) and 2 (JAK2) inhibitor) |

||||||||

|

Ely, 2022 |

Computerized

Randomisation was facilitated by a computer-generated random sequence using an interactive web-response system and was performed by a study investigator or designee. Participants were stratified at randomisation according to geographical region (Europe, USA, or the rest of the world). |

Unlikely

Randomisation was facilitated by a computer-generated random sequence using an interactive web-response system. |

Unlikely

Participants, study staff, and investigators were masked to the study assignment. |

Unlikely

Participants, study staff, and investigators were masked to the study assignment. |

Unlikely

Participants, study staff, and investigators were masked to the study assignment. |

Unlikely

All outcome measures described in the methods are reported in the results. |

Unlikely

The percentage of patients lost to follow-up is limited and similar between the groups. |

Unlikely

All randomized participants were included in the ITT analyses. |

|

Marconi, 2021 |

Computerized

Randomisation was facilitated by a computer-generated random sequence using an interactive web-response system, and was permitted by a study investigator or designee to allocate participants 1:1 to the baricitinib or the placebo group. Participants were stratified according to the following baseline factors: disease severity, age, region, and use of corticosteroids for primary study condition. |

Unlikely

Randomisation was facilitated by a computer-generated random sequence using an interactive web-response system. |

Unlikely

Participants, study staff, and investigators were masked to the study assignment. |

Unlikely

Participants, study staff, and investigators were masked to the study assignment. |

Unlikely

Participants, study staff, and investigators were masked to the study assignment. |

Unlikely

All outcome measures described in the methods are reported in the results. |

Unlikely

The percentage of patients lost to follow-up is limited and similar between the groups. |

Unlikely

For efficacy outcomes, all randomized participants were included in the ITT analyses. Safety analyses included all randomly allocated participants who received at least one dose of study drug and who were not lost to follow-up before the first post-baseline visit.

|

|

Kalil, 2020

|

Randomization was stratified by study site and disease severity at enrollment and was performed using a web-based Internet Data Entry System, Advantage eClinical. |

Unlikely

Eligible patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive either remdesivir and baricitinib or remdesivir and placebo. |

Unlikely

Patients were blind to treatment assignments.

|

Unlikely

The trial team was unaware of the trial-group assignments until after all data queries were resolved and the database was locked. |

Unlikely

The trial team was unaware of the trial-group assignments until after all data queries were resolved and the database was locked. |

Unlikely

All predefined outcomes were reported

|

Unclear

Reasons for loss to follow-up not mentioned.

|

Unlikely

Intention-to-treat analysis was performed. |

|

Nezulcitinib |

||||||||

|

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

|

Ruxolitinib (Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) and 2 (JAK2) inhibitor) |

||||||||

|

Cao, 2020b

|