Corticosteroïden

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van corticosteroïden bij de behandeling van COVID-19 patiënten?

Aanbeveling

Behandel patiënten met COVID-19 bij wie zuurstoftoediening geïndiceerd is en met name bij patiënten waarbij de zuurstoftherapie geëscaleerd moet worden naar invasieve respiratoire ondersteuning met dexamethason 6 mg per dag gedurende maximaal 10 dagen.

Bij patiënten zonder extra zuurstofbehoefte wordt behandeling met corticosteroïden niet aangeraden.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de verschillen in klinische uitkomsten tussen behandeling met en zonder corticosteroïden. Corticosteroïden die moesten worden geïnhaleerd werden in dit literatuuronderzoek niet opgenomen. Tot en met 2 september 2021 werden er 11 gerandomiseerde gecontroleerde studies (RCTs) gevonden in patiënten die waren opgenomen in het ziekenhuis (n=2989 in de interventiegroep en n=5018 in de controlegroep). De grootste studie die werd meegenomen was de RECOVERY trial (Horby, 2021), met meer dan 6000 geïncludeerde patiënten. Er werden geen studies gevonden die aan de selectiecriteria voldeden met ambulante patiënten.

De geïncludeerde studies onderzochten de volgende corticosteroïden: dexamethason (Tomazini, 2020; Jamaati, 2021; Horby, 2021), hydrocortison (Angus, 2020; Dequin, 2020; Munch, 2021), of methylprednisolon (Jeronimo, 2020; Edalatifard, 2020; Corral-Gudino, 2021; Solanich, 2021; Tang, 2021). De cruciale uitkomstmaten voor de besluitvorming waren mortaliteit en de noodzaak voor invasieve respiratoire ondersteuning. Daar waar mogelijk werd data van verschillende typen corticosteroïden gecombineerd om tot overkoepelende literatuurconclusies te komen over de effecten van corticosteroïden. Wanneer er enkel data aanwezig was over één type corticosteroïd werd het middel in de literatuurconclusies specifiek benoemd. Ook werden de effecten van corticosteroïden op de mortaliteit, in een subgroep analyse, opgesplitst naar ernst van ziekte: patiënten met milde, matige en ernstige COVID-19 symptomen op basis van respiratoire ondersteuning op moment van inclusie.

Er werden alleen randomiseerde trials geïncludeerd in de analyse, waardoor de kwaliteit van bewijs initieel hoog was. Omdat dat er een aantal open-label trials waren (waaronder de RECOVERY trial), met een mogelijk risico op vertekening van de studieresultaten (risk of bias) bij subjectieve uitkomstmaten, werd de kwaliteit van dit bewijs waar nodig naar beneden bijgesteld. Daarnaast waren er meerdere studies met een relatief kleine populatie en mede hierdoor een grote spreiding van het betrouwbaarheidsinterval rondom de puntschatter van de uitkomstmaat (imprecision), waardoor de kwaliteit van dit bewijs ook naar beneden werd bijgesteld.

Systemische corticosteroïden bij patiënten die waren opgenomen in het ziekenhuis

Met een redelijke zekerheid kan worden geconcludeerd dat er een reductie in de mortaliteit optreedt bij het gebruik van corticosteroïden (risicoverschil: -4,33%, 95% CI: -8,58% tot -0,07%; relatief risico: 0,89, 95% CI: 0,79 tot 1,02). Dit verschil werd door de werkgroep gedefinieerd als klinisch relevant. De data betroffen grotendeels patiënten met redelijke tot ernstige COVID-19; alleen de RECOVERY trial (Horby, 2021) includeerde ook patiënten met milde COVID-19.

De RECOVERY trial van Horby (2021) splitste de data van de mortaliteit ook op naar ernst van ziekte. De subgroep met ernstige ziekte kon worden gepoold in een meta-analyse samen met data van andere studies die enkel patiënten met ernstige ziekte includeerden (Tomazini, 2020; Angus, 2020). Bij het gebruik van corticosteroïden in de groep patiënten die als ernstig ziek kon worden aangemerkt, werd met een hoge zekerheid geconcludeerd dat er een klinisch relevante reductie in de mortaliteit optreedt (risicoverschil: -9,18%, 95% CI: -14,13% tot -4,23%; relatief risico: 0,82, 95%CI: 0,68 tot 0,98). Dit effect was minder groot, maar nog steeds statistisch significant, bij de patiënten met een matig-ernstige COVID (risicoverschil: -2,9%). Omdat dit verschil minder was dan de vooraf gedefinieerde grens van klinische relevantie (3% punten verschil), wordt in de conclusie beschreven dat dexamethason nauwelijks verschil maakt in de mortaliteit na 28 dagen. Echter, vanwege de grootte en de kwaliteit van de studie van Horby (2021), en de relatief beperkte bijwerkingen van dexamethason, wordt de risicoreductie van 2,9% nog steeds als relevant en betrouwbaar beschouwd. In de groep patiënten met milde COVID-19 (waarbij geen zuurstof suppletie nodig was) was er mogelijk een kleine, maar klinisch relevante, toename in de mortaliteit bij het gebruik van corticosteroïden (in dit geval dexamethason).

Het is nog niet duidelijk waarom er geen mortaliteitswinst is in de ‘milde groep’ zonder zuurstofbehoefte of bij personen die minder dan 7 dagen ziek waren. Het is daarbij niet helder wat daarbij het meest bepalend was: de ernst van infectie (dus de daling van de zuurstofsaturatie bij een aantal patiënten in die totale groep met een duur van symptomen van 7 dagen of minder) of alleen de duur van de symptomen. Deze bevindingen geven richting aan gebruik van dexamethason: vooral in de latere fase bij matig of ernstig zieke patiënten met extra zuurstofbehoefte waar (hyper)inflammatie op de voorgrond staat. Die zuurstofbehoefte is leidend vanwege de subgroep analyse in de studie van Horby (2021), maar mogelijk is gebruik van dexamethason ook bij slechts een korte duur (< 7 dagen) van symptomen niet effectief. Preventief gebruik in een vroege fase van infectie moet worden afgeraden, behalve als dat vanwege een andere indicatie (bijv. exacerbatie COPD) moet worden voorgeschreven. Een retrospectieve studie pleit voor gebruik van corticosteroïden alleen bij ernstige infecties, hier gedefinieerd door CRP >200 mg/L (vs. CRP <100 mg/L) (Keller, 2020). De RCTs in deze richtlijn gebruiken deze criteria niet en in het advies wordt een dergelijk afkappunt dan ook niet geadviseerd.

Uitkomsten betreffende invasieve respiratoire ondersteuning werden heterogeen gerapporteerd in de studies. Zo werd bijvoorbeeld de noodzaak voor invasieve ventilatie gerapporteerd, maar ook het aantal dagen aan mechanische ventilatie, het aantal dagen zonder respiratoire ondersteuning, de noodzaak voor high flow zuurstof of ventilatoire ondersteuning en de noodzaak voor respiratoire ondersteuning. Hierdoor zijn voor deze specifieke uitkomsten veelal weinig data beschikbaar. Met een lage tot zeer lage zekerheid werd geconcludeerd dat er bij verschillende typen corticosteroïden een klein tot geen effect zou kunnen optreden voor de verschillende uitkomsten die voor invasieve respiratoire ondersteuning werden gerapporteerd of dat het bewijs onzeker was over het effect. De studie van Horby (2021) liet wel een puntschatter zien in het voordeel van corticosteroïden.

Belangrijke uitkomstmaten waren de duur van hospitalisatie en de tijd tot klinische verbetering. Met een lage zekerheid werd geconcludeerd dat er een klein tot geen effect zou kunnen optreden op de duur van hospitalisatie. Het bewijs over het effect van corticosteroïden (in dit geval alleen methylprednisolon) op de tijd tot symptoomresolutie was erg onzeker, waarbij data over andere middelen ontbrak.

Soort corticosteroïden bij patiënten die waren opgenomen in het ziekenhuis

Omdat de geïncludeerde studies verschillende middelen onderzochten werden ze ook geclusterd geanalyseerd op basis van het middel dat verstrekt werd in de studie: dexamethason (Tomazini, 2020; Jamaati, 2021; Horby, 2021), hydrocortison (Angus, 2020; Dequin, 2020; Munch, 2021), of methylprednisolon (Jeronimo, 2020; Edalatifard, 2020; Corral-Gudino, 2021; Solanich, 2021; Tang, 2021). Zie de bijlage voor de literatuurbeoordelingen en -conclusies per middel. Een head-to-head vergelijking van de verschillende corticosteroïden is op dit moment niet beschikbaar.

Voor alle verschillende corticosteroïden was de gepoolde puntschatter van de risk ratio in het voordeel van het betreffende middel. Op basis van deze risk ratio’s is er geen voordeel uit te spreken voor een bepaald type corticosteroïden. Wel is er veruit het meeste bewijs beschikbaar voor dexamethason, omdat de grootste geïncludeerde studie (Horby, 2021) hier onderzoek naar deed. In het advies wordt er om deze reden een voorkeur voor dexamethason uitgesproken.

Duur van de behandeling met corticosteroïden

In de geïncludeerde studies worden niet alleen verschillende middelen onderzocht, ook de duur en de dosis van de behandeling is verschillend. De behandelduur varieert van enkele dagen tot 28 dagen. Het meeste bewijs komt uit de studie van Horby (2021), waar patiënten gedurende 10 dagen met 6 mg dexamethason werden behandeld of tot en met de dag dat ze uit het ziekenhuis werden ontslagen. In het advies zullen wij deze behandelduur aanhouden.

Overige overwegingen

Dosering

Klinische dose-finding studies voor corticosteroïden zijn niet gedaan. Er is op dit moment onvoldoende data over het gebruik van hogere doses corticosteroïden dan de dosis gebruikt in de RECOVERY-studie. Een recente RCT uit Iran met 86 patiënten laat zien dat 2 mg/kg/dag methylprednisolon geassocieerd is met een sneller klinisch herstel, kortere opname duur en kleinere kans op progressie naar invasieve beademing, vergeleken met 6 mg dexamethason per dag (Ranibar, 2021). Echter, deze studie is relatief klein en van matige kwaliteit en vergelijkt bovendien twee verschillende doseringen van twee verschillende middelen. Een grote RCT in Europa en India met 982 deelnemers met tenminste 10 liter zuurstofbehoefte (COVID STEROID 2 Trial group, 2021), randomiseerde naar 12 mg of 6 mg dexamethason. Er werd geen statistisch significant verschil gezien qua dagen vrij van orgaanondersteuning (22,0 dagen bij 12 mg versus 20,5 dagen bij 6 mg dexamethason) of mortaliteit na 28 dagen (27,1% bij 12 mg versus 32,3% bij 6 mg dexamethason). Wel rapporteren de auteurs dat de uitkomsten allebei neigen naar een voordeel van een hogere dosering dexamethason zonder dat er een verschil was in de hoeveelheid bijwerkingen. Een Italiaanse RCT randomiseerde 301 patiënten naar methylprednisolon boven op de standaard behandeling met dexamethason 6 mg (Salvarani, 2022). In deze studie werd geen voordeel gezien van aanvullende behandeling met methylprednisolon.

Al met al is er op dit moment geen positief bewijs voor behandeling met een hogere dosering corticosteroïden dan 6 mg dexamethason. Daarnaast is het nog onduidelijk of een hogere dosering corticosteroïden de toevoeging van een IL-6 remmer (zoals tocilizumab) onnodig maakt bij ernstig zieke patiënten, zoals dat op dit moment gebruikelijk is. Ook is het onduidelijk of een hogere dosering corticosteroïden in combinatie met een IL-6 remmer tot meer complicaties zou leiden in deze populatie. In de COVID STEROID 2 studie werd IL-6 therapie toegepast in een minderheid van de patiënten (11% van de 12 mg dexamethason groep en 10% van de 6 mg dexamethason groep). Eerdere onderzoeken bij andere virale luchtweginfecties lieten zien dat de mortaliteit toenam bij het gebruik van hogere doseringen corticosteroïden. Vandaar dat er op dit moment wordt afgeraden om hogere doseringen corticosteroïden toe te passen buiten studieverband.

Bijwerkingen

Omdat er zeer heterogene definities werden gebruikt bij het rapporteren van bijwerkingen en er een hoog risico op bias was, werden deze gegevens niet systematisch weergegeven in de module. Een Cochrane review zet de bijwerkingen van diverse studies op een rij (Wagner, 2021). Er wordt geen meta-analyse verricht, maar een analyse van de descriptieve statistiek van de studies resulteert wel in de conclusie dat er geen grote verschillen in (ernstige) bijwerkingen werden gezien in de groep met en zonder corticosteroïden. Ook als er specifiek naar in het ziekenhuis opgelopen infecties werd gekeken, werden er geen grote verschillen gezien.

Ondanks dat de verschillen in bijwerkingen en ongewenste effecten van corticosteroïden niet in deze studies naar voren komen, is het wel bekend dat corticosteroïden geassocieerd zijn met onder andere een ontregeling van diabetes mellitus, het optreden van neuropsychiatrische symptomen en predisponeren voor infecties. Bij hoge doseringen corticosteroiden werd er ook een associate met ernstige schimmelinfecties beschreven zoals aspergillose en mucormycose (Hoenigl, 2022).

Speciale patiëntengroepen

Het is logisch om het advies over corticosteroïden voor volwassenen naar zeer ernstig zieke kinderen te extrapoleren. Helaas kan dit niet goed worden onderbouwd met gerandomiseerd onderzoek. Bij kinderen is er nu nog weinig bewijs dat COVID-19 met meer complicaties gepaard gaat, de ziekte lijkt bij kinderen juist met minder complicaties gepaard te gaan. Dat zou pleiten voor terughoudendheid voor het voorschrijven van corticosteroïden bij minder zieke pediatrische patiënten (niet op IC opgenomen).

In de bovengenoemde trials werden ook oudere patiënten geïncludeerd. In een subgroep analyse van de RECOVERY trial, bij ruim 900 patiënten die ouder waren dan 70 jaar, werd een mogelijk minder sterk voordeel van dexamethason zien op de 28-dagen mortaliteit (Horby, 2021). Bij de kwetsbare oudere patiënt kan dexamethason een hoger risico geven op een delier, waardoor een afweging van de baten en te verwachte bijwerkingen extra belangrijk is.

Inhalatiecorticosteroïden

Therapie met inhalatiecorticosteroïden (ICS) is tot nu toe vooral overwogen bij ambulante patiënten. Het gebruik van ICS is relatief eenvoudig en kent, zeker als de behandeling kortdurend is, weinig bijwerkingen. Er zijn tot nu toe vier gerandomiseerde studies gepubliceerd die rapporteren over het effect van ICS bij patiënten met COVID-19.

In een open-label fase 2-gerandomiseerd onderzoek (de STOIC-trial) werd het effect van de inhalatie van budesonide (2dd 800 ug) onderzocht bij patiënten die waren gediagnosticeerd met covid-19 en nog geen opname-indicatie hadden (Ramakrishnan, 2021). Deze studie werd voortijdig gestopt na inclusie en 1:1-randomisatie van 146 patiënten. Het primaire eindpunt was de behoefte aan ‘urgente medische zorg’. Dit kwam frequenter voor in de groep met standaardzorg dan in de groep die budesonide gebruikte (11 versus 2 maal, dit was statistisch significant). Patiënten die ICS gebruikte waren gemiddeld 1 dag eerder klachtenvrij. De hoeveelheid virus die op verschillende momenten was gemeten middels nasofarynxuitstrijk verschilde niet tussen beide groepen. Een andere open-label fase 2-gerandomiseerde studie onderzocht het effect van ciclesonide inhalatie (2dd 320 ug) gedurende 14 dagen (Song, 2021). Patiënten waren ambulant en hadden een recente diagnose COVID-19 (binnen 7 dagen na start symptomen of binnen 3 dagen na diagnose). Er werden 61 patiënten geïncludeerd. In de groep met ICS werd een snellere daling van de viral load gezien en een kleinere kans op klinisch falen. Echter, het aantal patiënten in de studie was klein en deze positieve effecten werden niet in alle secundaire uitkomstmaten terug gezien.

In de grootste trial, de open-label PRINCIPLE trial (Yu, 2021), werden ambulante patiënten geïncludeerd met verhoogd risico op een ernstig beloop. Inclusiecriteria waren o.a. een leeftijd ≥ 50 jaar met minimaal 1 comorbiditeit, of een leeftijd ≥ 65 jaar, met of zonder comorbiditeit. Eindpunten waren de door de patiënt zelf gerapporteerde tijd tot herstel, en noodzaak tot ziekenhuisopname in de eerste 28 dagen. Na randomisatie en exclusie vanwege het ontbreken van een positieve test voor SARS-CoV-2, werden er 787 personen in de budesonide behandelgroep en 1069 in de controlegroep geanalyseerd. Patiënten die budesonide turbuhaler gebruikten rapporteerden gemiddeld 3 dagen eerder hersteld te zijn. In de standaardzorg groep werden iets meer patiënten binnen 28 dagen na randomisatie in het ziekenhuis opgenomen (8,8% vs. 6,8%; OR 0,75 in het voordeel van budesonide; CI 95% 0,55-1,03). Superioriteit van budesonide voor deze uitkomstmaat werd statistisch niet aangetoond.

De RCT van Clemency (2022) randomiseerde 400 ambulante patiënten naar 2 maal per dag ciclesonide 320 ug of placebo gedurende 30 dagen. Inclusie in de studie was onafhankelijk van de duur van de klachten of onderliggend lijden. Gemiddeld waren de patiënten 43 jaar, 55% was vrouw. Het primaire eindpunt van de studie was de tijd tot alle symptomen van COVID-19 verdwenen waren. In beide groepen was dit 19 dagen. Er werd ook geen verschil gezien in het percentage mensen dat op dag 30 nog symptomen had: 70,6% was klachtenvrij in de ciclesonide groep versus 63,5% in de placebo groep (OR 1,28; 95% CI 0,84-1,97). Wel werden er minder bezoeken aan de spoedeisende hulp of opnames gezien in de groep met ciclesonide: 1% versus 5,4% (OR 0,18; 95% CI 0,04-0,85). Niemand overleed tijdens de studie.

De vier gerapporteerde RCT’s beschrijven allen in meer of mindere mate een positief effect van ICS. Twee studies waren relatief klein; de PRINCIPLE studie had methodologische beperkingen, onder meer omdat de behandeling niet geblindeerd was en de tijd tot herstel door patiënten ‘self-reported’ was. De RCT van Clemency (2022) heeft door de blindering beduidend minder beperkingen. In zowel de studie van Clemency (2022) als de PRINCIPLE trial (Yu, 2021) was het aantal patiënten dat zou zijn behandeld zijn om 1 ziekenhuisopname te voorkomen echter hoog, 50 (number needed to treat). De STOIC trial bevatte te weinig inclusies om de werkzaamheid betrouwbaar vast te stellen. Data over het voorkomen van harde eindpunten als IC opname, noodzaak tot mechanische ventilatie en overlijden, ontbreken. Er zijn geen gegevens uit deze of andere studies die wijzen op een schadelijk effect van ICS, ook een Cochrane review die 3 RCT’s includeerde, vond geen verhoogd aantal ‘adverse events’ bij het gebruik van ICS (Griesel, 2022).

Op basis van bovengenoemde data heeft de NHG een behandeladvies opgesteld voor ambulante patiënten (zie NHG standaard COVID-19, corona.nhg.org. Bij opgenomen patiënten is er geen plaats voor behandeling met inhalatiecorticosteroïden.

In maart 2022 adviseerde de Amerikaanse NIH (National Institutes of Health) niet voor of tegen het gebruikt van ICS, de Amerikaanse IDSA (Infectious Diseases Society of America) adviseerde tegen het gebruik van ICS. De IDSA nam in haar advies ook de studie van Ezer (2021) mee, die geen positief effect van ciclesonide liet zien. Deze studie was echter vroegtijdig gestopt en was mogelijk ‘underpowered’.

Virusvarianten

Sinds de opkomst van de omikron variant van SARS-CoV-2 in Nederland eind 2021, is de kans op een ernstig beloop van COVID-19 op populatieniveau zeer sterk gedaald. Het is van belang om op te merken dat de besproken gerandomiseerde studies werden verricht voor de opkomst van de omikron variant. Het is onduidelijk wat de invloed is van deze variant op het effect van anti-inflammatoire therapie, al wordt aangenomen dat patiënten die door de omikron variant een ernstige COVID-19 infectie ontwikkelen nog steeds baat hebben bij anti-inflammatoire therapie. De ‘number needed to treat’ zou wel anders (vermoedelijk hoger) kunnen zijn.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Er werd een klinisch relevant voordeel gevonden bij opgenomen patiënten met een ernstige COVID-19 infectie die behandeld werden met dexamethason, vergeleken met de groep die dit niet kreeg. In patiënten met een matig ernstige COVID-19 infectie werd er ook voordeel vastgesteld, al was dit minder groot dan bij patiënten met een ernstige ziekte.

Het is voor patiënten belangrijk om te weten wat de voor en nadelen van dexamethason zijn, zoals bijvoorbeeld de ontregeling van de glucose waarden bij patiënten met pre-existente diabetes mellitus (zie ook het kopje ‘bijwerkingen’). Deze nadelen zullen in de groep patiënten met een matig ernstige COVID-19 infectie zwaarder wegen dan bij patiënten met een ernstige COVID-19, waar deze mogelijke bijwerkingen veelal opwegen tegen de sterke voordelen.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Een behandeling met dexamethason gedurende 10 dagen kost ongeveer 50 euro indien dit intraveneus gegeven wordt en 10 euro indien dit oraal gegeven wordt. Dit is relatief weinig vergeleken met de kosten die gemaakt worden bij de opname van patiënten met COVID-19.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Dexamethason lijkt effectief om een ernstig beloop van de ziekte te voorkomen en de kosten zijn beperkt. De bijwerkingen, zoals bij de overwegingen beschreven, kunnen echter de aanvaardbaarheid beperken.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Bij patiënten met COVID-19 bij wie zuurstoftoediening geïndiceerd is vanwege saturatiedaling, en met name bij patiënten waarbij de zuurstoftherapie geëscaleerd moet worden naar invasieve respiratoire ondersteuning, is behandeling met dexamethason 6 mg per dag (of een equivalente dosis hydrocortison/prednison) gedurende 10 dagen of tot ontslag uit het ziekenhuis, aangewezen. Bij patiënten zonder extra zuurstofbehoefte wordt behandeling met corticosteroïden niet aangeraden. Voor de behandeling van kinderen kunnen de doseringen beschreven in het Kinderformularium worden gebruikt.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Een dysregulatie van de immuunrespons lijkt bij COVID-19 een belangrijke rol in de pathofysiologie te spelen (Veerdonk, 2021). Er worden verschillende middelen ingezet en onderzocht met anti-inflammatoire werking. Corticosteroïden zijn goed beschikbaar en werden bij infecties met SARS-CoV-1 en MERS-CoV virussen frequent voorgeschreven in de hoop dat daarmee immuun-gemedieerde schade voorkomen kon worden. Omdat corticosteroïden ook kunnen zorgen voor een toename of langere duur van virale replicatie was er veel twijfel over gebruik ervan als behandeling (Lee, 2004; Arabi, 2018). In algemene zin wijzen de verschillende meta-analyses naar de toepassing van corticosteroïden bij ARDS in de richting van verbeterde uitkomsten met corticosteroïden (Meduri, 2016; Peter, 2008; Yang, 2017). Bij influenza geassocieerde ARDS is er echter een aanwijzing voor verhoogde mortaliteit (Tsai, 2020).

Een eerste retrospectieve analyse van opgenomen SARS-CoV-2 patiënten in Wuhan, China, toonde dat de sterfte van patiënten die een ARDS ontwikkelden lager was in de groep die behandeld werd met methylprednisolon dan in de groep zonder (Wu, 2020). De gebruikte dosis werd niet vermeld. Klinische dose-finding studies zijn niet gedaan. Inmiddels is in diverse gerandomiseerde studies (RCTs) de effectiviteit van corticosteroïden onderzocht om de plaats van corticosteroïden bij de behandeling van COVID-19 patiënten te bepalen.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Systemic corticosteroids in hospitalized COVID-19 patients

Mortality (crucial)

|

Moderate GRADE |

Treatment with corticosteroids (all combined) probably reduces mortality (overall) when compared with treatment without corticosteroids in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Source: Angus, 2020; Corral-Gudino, 2021; Dequin,2020; Edalatifard, 2020; Horby, 2021; Jamaati, 2021; Jeronimo, 2020; Much, 2021; Solanich, 2021; Tang, 2021; Tomazini, 2020 |

|

High GRADE |

Treatment with corticosteroids (all combined) reduces mortality when compared with treatment without corticosteroids in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19.

Source: Angus, 2020; Horby, 2021; Tomazini, 2020 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Treatment with dexamethasone probably results in limited difference of mortality when compared with treatment without dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with moderate COVID-19.

Source: Horby, 2021 |

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with dexamethasone may increase mortality when compared with treatment without dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with mild COVID-19.

Source: Horby, 2021 |

Extensive respiratory support (crucial)

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with corticosteroids may result in little to no difference in the need for extensive respiratory support when compared with treatment without corticosteroids in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Source: Angus, 2020; Corral-Gudino, 2021; Dequin, 2020; Edalatifard, 2021; Horby, 2021; Jamaati, 2021; Jeronimo, 2020; Solanich 2021; Tang, 2021; Tomazini, 2020 |

Duration of hospitalization

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with corticosteroids may result in little to no difference in the length of stay when compared with treatment without corticosteroids in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Source: Horby, 2021; Angus, 2020; Jamaati, 2021; Jeronimo, 2020; Tang, 2021 |

Time to clinical improvement

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effects of methylprednisolone on the time to clinical improvement when compared with treatment without methylprednisolone in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Source: Solanich, 2021; Tang, 2021 |

Corticosteroids in non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients

|

No GRADE |

No studies were found investigating the effect of corticosteroids on mortality, respiratory support, duration of hospitalization, or time to clinical improvement compared to standard care in non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Sources: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Systemic corticosteroids in hospitalized COVID-19 patients

DEXAMETHASONE

Tomazini (2020) (CoDEX trial) described a multicenter, open-label randomized clinical trial in Brazil comparing intravenous dexamethasone and standard care with standard care only in patients admitted to an ICU with suspected or confirmed COVID-19. The trial was terminated early. Patients were included when intubated and mechanically ventilated within 48 hours of meeting the criteria for moderate or severe ARDS. Patients were excluded when they e.g. used corticosteroids in the past 15 days (when non-hospitalized) or were immunosuppressed. A total of 299 patients were randomized to receive standard care and dexamethasone or to receive standard care only. The dexamethasone-group received 20 mg dexamethasone once daily intravenously for the first five days, followed by 10 mg intravenously for the following 5 days or until ICU discharge. In the standard care only-group 35.1% of the patients had deviations from the assigned control intervention and received corticosteroids as well. Follow-up in both the intervention and control group was 28 days. The following outcomes relevant to this guideline module were reported: mortality, respiratory support, and serious adverse events. Following the predefined criteria by the working group for mild, moderate, and severe disease status at randomization, the sample in Tomazini (2020) contained patients with severe disease at baseline. The primary outcome was mechanical ventilatory-free days during the first 28 days. The corticosteroid group had a mean ventilatory-free days of 6.6 (95% CI: 5.0 to 8.2), compared to 4.0 days (95% CI: 2.9 to 5.4) in the group not receiving corticosteroids (difference: 2.26 days, 95% CI: 0.2 to 4.38).

Jamaati (2021) reported the preliminary results of a randomized controlled trial in a hospital in Iran comparing intravenous dexamethasone and standard care to standard care only. The trial was terminated after no significant clinical response was observed in 50 patients. Patients were included when e.g. they had a PaO2/FiO2 ratio between 100-300mmHg. Exclusion criteria were e.g. chronic kidney or liver disease, or hyperglycemia. The 50 included patients were randomized to dexamethasone with standard care (n=25) or to standard care only (n=25). Standard care consisted of oxygen support, fluid support, and lopinavir/ritonavir (200/50 mg, two tablets twice daily) according to Iranian guidelines. Dexamethasone at a dose of 20mg per day was administered intravenously up to day 5, whereafter 10mg per day was administered intravenously up to day 10. At baseline, the standard care only-group had more patients with pulmonary disease (36%) compared to the dexamethasone-group (4%). Follow-up in both groups was 28 days. The following outcomes relevant to this guideline module were reported: mortality, need for non-invasive ventilation, and duration of hospitalization. The disease status in Jamaati (2020) was mild to moderate disease, patients were included when the PaO2/FiO2 ratio was between 100 and 300 mmHg. The primary outcomes were both the need for extensive mechanical ventilation and the death rate. In the corticosteroids group 52.0% required invasive mechanical ventilation compared to 44.0% in the control group (RR=1.18, 95% CI: 0.66 to 2.11; RD=8%. 95% CI: -19.6% to 35.6%). Sixteen deaths (16/25, 64.0%) were observed in the corticosteroids group, compared to 15 deaths (15/25, 60.0%) in the group not receiving corticosteroids (RR=1.07, 95% CI: 0.69 to 1.65; RD=4%, 95% CI: -22.9% to 30.9%).

Horby (202) (RECOVERY trial) described an open-label randomized clinical trial in the United Kingdom assessing the effect of dexamethasone and standard care compared to standard care only. Patients were included when hospitalized, and had no medical history that would put the patient substantially at risk when participating in the study. Exclusion criteria were not specified. A total of 6.425 patients were included and randomized to dexamethasone and standard care or to standard care only. Standard care was provided as the usual standard of care in the participating hospital but was not further defined in the trial report. Patients in the dexamethasone-group received 6mg oral or intravenous dexamethasone daily for up to 10 days or until discharge, whichever came first. Here, 95% of the patients received at least one dose of a glucocorticoid. The standard care group received the usual care, however 8% of these patients also received a glucocorticoid. Follow-up in both groups was 28 days. The following outcomes relevant to this guideline module were reported: mortality, respiratory support, and serious adverse events. Following the predefined criteria by the working group for mild, moderate, and severe disease status at randomization, the sample in Horby (2020) contained patients with mild to severe disease at baseline. The primary outcome was the 28-day all-cause mortality. Here, 482 deaths (482/2104, 22.9%) were observed in the dexamethasone group, compared to 1.110 deaths (1110/4321, 25.7%) in the usual care group (RR=0.89, 95% CI: 0.81 to 0.98; RD=-2.8%, 95% CI: -5% to -0.6%).

HYDROCORTISONE

Angus (2020) (REMAP-CAP) examined the effects of hydrocortisone compared to usual care as part of a multicenter open-label adaptive platform randomized controlled trial. Centers were located in Australia, Canada, France, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America. The domain examining corticosteroids was terminated early due to a loss of equipoise, while no study data were reviewed prior to the decision to stop enrollment of patients. Patients were included when admitted to the intensive care unit for respiratory or cardiovascular organ support. Patients were excluded when e.g. death was deemed imminent and inevitable, or soon discharge was expected, or when more than 36 hours elapsed since admission to the intensive care unit, or when the treating clinician believed that participating would not be in the best interest of the patient. Patients were randomly allocated to one of the three study-arms: fixed dose hydrocortisone, shock-dependent hydrocortisone, and a standard of care without hydrocortisone. Standard care was provided as per each center’s standard. Systemic corticosteroids were permitted in all groups when new indications developed for which corticosteroids would be an established treatment. In the group who were randomized to standard care without hydrocortisone, 15% (n=15) received a systemic corticosteroid (of which n=6 received hydrocortisone). Patients in the fixed dose-group received 50 mg hydrocortisone intravenously every 6 hours for 7 days (n=2 received 100 mg fixed dose). Patients in the shock-dependent-group received 50 mg hydrocortisone intravenously every 6 hours while in shock and up to 28 days. Shock was defined as the requirement for treatment for shock due to COVID-19 by intravenous vasopressor infusion. Hydrocortisone was discontinued when the shock was considered to be resolved or when vasopressors were discontinued for 24 hours. Follow-up of the primary outcome was 21 days. The following outcomes relevant to this guideline module were reported: mortality, respiratory support, duration of hospitalization and serious adverse events. Following the predefined criteria by the working group for mild, moderate, and severe disease status at randomization, the sample in Angus (2020) contained patients with severe disease at baseline (with the exception of one patient in the shock-dependent-group who did not receive any acute respiratory support or received supplemental oxygen only). The primary outcome was alive and free of respiratory or cardiovascular organ support- up to 21 days. Median organ support-free days were reported for the fixed-dose group (0 days, IQR: -1 to 15), the shock-dependent group (0 days, IQR: -1 to 13), and the no hydrocortisone group (0 days, IQR: -1 to 11).

Dequin (2020) (CAPECOVID trial) described a multicenter randomized controlled trial examining the effects of hydrocortisone compared to a placebo on intensive care units in France. The trial was terminated early pending the results of the RECOVERY trial and changes in treatment recommendations. Patients were included when admitted to a participating intensive care unit for acute respiratory distress syndrome, and when the experimental treatment was administered within 24 hours of the onset of one of the severity criteria (or within 48 hours when patients were referred from another hospital). Patients were excluded when in septic shock or when there were do-not-intubate orders. Included patients were randomized to hydrocortisone (n=76) or to placebo (n=73). The hydrocortisone dose was 200 mg/day until day 7, 100 mg/day for the next 4 days, and 50 mg/day for the last 3 days of a 14-day treatment regime. When the patient’s respiratory status had sufficiently improved by day 4 a short treatment regime of 8 days was initiated instead (200 mg/day until day 4, 100 mg/day for the next 2 days, and 50 mg/day for the last 2 days). Patients in the placebo-group received saline. Adjunctive therapy was allowed in both groups at the discretion of the treating primary physicians. In the hydrocortisone group, n=44 (57.9%) received one or more adjunctive therapies, compared to n=47 (64.4%) in the placebo-group. Adjunctive therapies provided consisted of hydroxycholoquine (whether or not in combination with azithromycin), ritonavir-lopinavir, eculizumab, remdesivir, and/or tocilizumab. The follow-up was 21 days for the post-hoc outcomes. The following outcomes relevant to this guideline module were reported: mortality, respiratory support, and serious adverse events. Following the predefined criteria by the working group for mild, moderate, and severe disease status at randomization, the sample in Dequin (2020) contained patients with moderate (n=9 had a non-rebreathing mask) to severe disease at baseline. The primary outcome was treatment failure on day 21, a composite of death or the persistent dependency on mechanical ventilation or high-flow oxygen therapy. Treatment failure was observed in 32 patients (32/76, 42.1%) receiving hydrocortisone, compared to 37 patients (37/73, 50.7%) in the placebo group (difference: -8.6%, 95% CI: -24.9% to 7.7%, p=0.29).

Munch (2021) (COVID STEROID trial) described a multicenter randomized controlled trial examining the effects of hydrocortisone compared to a placebo in Denmark. The trial was terminated early due to an unexpected inability to enroll patients. Patients were included when they had severe hypoxia (i.e. use of mechanical or non-mechanical ventilation, or continuous use of CPAP for hypoxia, or oxygen supplementation of at least 10 L/minute independent of delivery system). Patients were excluded when e.g. they used systemic corticosteroids, had invasive mechanical ventilation more than 48 hours before screening. Participating patients were randomized to hydrocortisone (n=16) or placebo (n=14), both with standard care. The hydrocortisone-group received 200 mg per day using continuous infusion over the course of 24 hours or per bolus injection of 50mg each 6 hours. Treatment continued up to 7 days or until hospital discharge. The placebo-group received 0.9% saline continuously infused over the course of 24 hours or as bolus injections every 6 hours. Additional antiviral treatment provided were remdesivir (n=4) or convalescent plasma (n=2). Antibacterial agents were provided in 12 participants (86%). In the hydrocortisone group, n=8 had major protocol deviations, compared to n=3 in the placebo group. The follow-up was 90 days. The following outcomes relevant to this guideline module were reported: mortality and serious adverse events. Following the predefined criteria by the working group for mild, moderate, and severe disease status at randomization, the sample in Munch (2020) contained patients with moderate to severe disease at baseline. The primary outcome was days alive without the use of life support up to day 28. No difference was observed between groups (adjusted mean difference: -1.1 days, 95% CI: -9.5 to 7.3).

METHYLPREDNISOLONE

Jeronimo (2020) (Metcovid trial) reported a randomized controlled trial examining the effects of sodium succinate methylprednisolone compared to a placebo in Brazil. Patients were included when they had a clinical suspicion of COVID-19 (fever and any respiratory symptom), were 18 years or older, had an SpO2 ≤ 94% with room air, and required supplemental oxygen or invasive mechanical ventilation. Patients were excluded when they had e.g. chronic use of corticosteroid or immunosuppressive agents, had decompensated cirrhosis, or had chronic renal failure. Participating patients were randomized to sodium succinate methylprednisolone (n=209) or placebo (n=207). The methylprednisolone group received 0.5 mg/kg intravenously twice daily over the course of five days. Patients in the placebo group received a saline solution intravenously twice daily for five days. All participating patients meeting criteria for acute respiratory distress syndrome received preemptive ceftriaxone (1g twice daily, 7 days) plus azithromycin (500 mg/day, 5 days) or clarithromycin (500 mg twice daily, 7 days) intravenously. The follow-up was 28 days. The following outcomes relevant to this guideline module were reported: mortality, respiratory support, duration of hospitalization, and viral clearance. Following the predefined criteria by the working group for mild, moderate, and severe disease status at randomization, the cohort contained patients with moderate to severe disease or had an unclear respiratory status (33.8% received invasive mechanical ventilation, 47.8% received non-invasive oxygen therapy, 18.4% unreported). The primary outcome was the 28-day mortality. There were 72 observed deaths (72/194, 37.1%) in the methylprednisolone group compared to 76 (76/199, 38.2%) observed deaths in the placebo group (RR=0.97, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.25; RD=-1.1%, 95% CI -10.7% to 8.5%).

Edalatifard (2020) reported a randomized controlled trial examining the effects of methylprednisolone compared to no methylprednisolone in Iran. Patients were included when 18 years or older, had confirmed COVID-19 (positive RT-PCR and abnormal CT-scan findings) with an SpO2 <90% at rest, had C-reactive protein > 10 mg/L and interleukin-6 >6 pg/ml before connecting to the ventilator and intubation, and when agreed to give informed consent. Patients were excluded when they had e.g. an SpO2 < 70%, had a positive pro-calcitonin and troponin test, had acute respiratory distress syndrome, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, gastrointestinal problems or bleeding history, heart failure, or active malignancies, or received any immunosuppressive agents. Participating patients were randomized to receive standard care with methylprednisolone pulse (n=34) or standard care without methylprednisolone or other glucocorticoids (n=34). The standard care consisted of hydroxychloroquine sulfate, lopinavir, and naproxen. Patients allocated to methylprednisolone pulse received 250 mg per day from an intravenous injection for three days. Six persons in the group receiving standard care without methylprednisolone had received corticosteroids and were excluded. The follow-up was 3 days. The following outcomes relevant to this guideline module were reported: mortality, respiratory support, and serious adverse events. Following the predefined criteria by the working group for mild, moderate, and severe disease status at randomization, the sample in Edalatifard (2020) contained patients with moderate to severe disease at baseline. The primary outcomes were the time to clinical improvement, and a composite of the time to hospital discharge or death (whichever came first). Median time to improvement was 11.84 days in the methylprednisolone group compared to 16.44 days in the standard care group (p=0.011). Median time to discharge or death was 11.62 days versus 17.61 days for the methylprednisolone group and the standard care group, respectively.

Corral-Gudino (2021) (GLUCOCOVID trial) described a multicenter open-label randomized controlled trial assessing the effect of methylprednisolone with standard care compared to standard care only in Spain. The trial was terminated before the intended sample size was achieved. Patients were included when they e.g. had symptoms for at least 7 days, had moderate to severe disease with abnormal gas exchange (PaO2/FiO2 or PaFi < 300, SaO2/FiO2 or SaFi <400, or at least two criteria of the BRESCIA-COVID Respiratory Severity Scale), and had evidence of a systemic inflammatory response (any criterium: CRP >150 mg/L, D-dimer >800 ng/ml, ferritin >100 mg/dl, IL-6 >20 pg/ml). Exclusions were made when patients were mechanically ventilated, hospitalized in the intensive care unit, were treated with corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents at the time of enrollment, had chronic kidney disease on dialysis, or were pregnant. Sixty-four participants were randomized to receive methylprednisolone with standard care (n=35) or to receive standard care only (n=29). Standard care was provided according to the local hospital protocols based on the recommendations of the Spanish Ministry of Health and the World Health Organization. The authors stated that the local standard of care protocols among the participating hospitals were similar. The trial also set up a preference arm which allocated the treatment based on preferences rather than randomization. Patients receiving methylprednisolone were administered 40 mg intravenously twice per day for the first three days, whereafter the dose reduced to 20 mg twice per day for the next three days. Additional therapies provided in both groups were azithromycin, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir/ritonavir, and low molecular weight heparin. The follow-up was 28 days. The following outcomes relevant to this guideline module were reported: mortality and respiratory support. Following the predefined criteria by the working group for mild, moderate, and severe disease status at randomization, the sample in Corral-Gudino (2021) contained patients with unclear disease severity at baseline. The respiratory status at inclusion or randomization was not reported, although patients receiving mechanical ventilation or when admitted to the intensive care unit were excluded. The primary outcome was a composite consisting of in-hospital all-cause mortality, escalation to ICU admission, and progression of respiratory insufficiency which would require non-invasive ventilatory support. Although events occurred less frequently in the methylprednisolone group, no statistical differences between groups were found (RR=0.68, 95% CI: 0.37 to 1.26).

Solanich (2021) reported a single-center open-label randomized controlled trial assessing the effects of methylprednisolone and tacrolimus with standard care compared to standard care only in Spain. The trial was terminated early. Patients were included when they had respiratory failure (PaO2/FiO2 <300, or SpO2/FiO2 < 220), and had high inflammatory parameters (CRP >100 mg/L, or D-dimer >1000 µg/L, or ferritin >1000µg/L). Patients were excluded when they had e.g. a glomerular infiltration of 30 ml/min/1.73m2 or less, had leukopenia of 4000 cells/µl or less, had other conditions that cause immunosuppression, had a concomitant potentially serious infection, had contraindications for corticosteroid or tacrolimus use. The intervention-arm (n=27) received 120 mg/day methylprednisolone pulses on three consecutive days. Longer duration or a higher dose was allowed when considered appropriate by the treating physician. Besides methylprednisolone, tacrolimus was administered twice daily at 0.05 mg/kg as a starting dose. Tacrolimus dose was thereafter adjusted to achieve 8-10 ng/ml levels in the patient’s blood. Standard care could consist of supplemental oxygen and respiratory support, fluid therapy, anti-pyretic treatment, postural interventions, low molecular weight heparin, antiviral drugs (e.g. lopinavir/ritonavir, hydroxychloroquine), and/or immunosuppressive drugs (e.g. corticosteroids, tocilizumab, anakinra) at the discretion of the treating physician. The standard care-only group (n=28) could not receive cyclosporine or tacrolimus. All patients in the standard care-only group received corticosteroids during hospitalization (median duration of corticosteroid therapy: 18.5 days, IQR: 3.00-53.2 days). The follow-up was 58 days. The following outcomes relevant to this guideline module were reported: mortality, respiratory support, duration of hospitalization, time to clinical improvement. Following the predefined criteria by the working group for mild, moderate, and severe disease status at randomization, the cohort contained patients with moderate to severe disease severity at baseline. The primary outcome was days to reach clinical stability up to 56 days. No statistical differences between groups were found (HR=0.73, 95%CI: 0.39 to 1.37), where the methylprednisolone group had a median of 10.0 days (IQR: 7.0 to 13.0) compared to 11.0 days (IQR: 8.0 to 18.0).

Tang (2021) described a multicenter single-blind randomized controlled trial assessing the effects of methylprednisolone and standard care compared to a placebo and standard care in China. The trial was terminated before the intended sample size was reached. Patients were included when they had a laboratory confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, had pneumonia as confirmed by CT, were 18 years or older, were admitted to the general ward for less than 72 hours, and when they were able to sign the informed consent. Patients were excluded when there was e.g. severe immunosuppression, when corticosteroids were needed for other disease, had refractory hypertension or hypokalemia, epilepsy, delirium, glaucoma, active gastrointestinal bleeding (within the last 3 months), or secondary bacterial or fungal infections. Patients allocated to receive methylprednisolone and standard care (n=43) or placebo and standard care (n=43). Standard care was provided according to version 6 of the Chinese Diagnosis and Treatment Plan for COVID-19. The methylprednisolone-group received 1 mg/kg methylprednisolone per day for 7 days. Patients in the placebo-group received 100 ml 0.9% saline intravenously per day for 7 days. The majority (>70%) of patients received additional therapies: such as antiviral and/or antibacterial drugs. The follow-up was 14 days. The following outcomes relevant to this guideline module were reported: mortality, respiratory support, duration of hospitalization, time to clinical improvement. Following the predefined criteria by the working group for mild, moderate, and severe disease status at randomization, the cohort contained patients with moderate to severe or unclear disease severity at baseline as 70.9% received oxygen therapy via nasal cannula and 47.7% had hypoxic respiratory failure. It was not found whether there were patients without any oxygen supplementation. The primary outcome was the occurrence of clinical deterioration within 14 days. Both groups had a clinical deterioration rate of 4.8% (OR=1.00, 95% CI: 0.13 to 7.44).

Table 1. Overview of RCTs comparing corticosteroids with standard care in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

|

Author (year, trial name) |

Disease severity* |

Sample size |

Dosage/regime |

|

Dexamethasone |

|||

|

Tomazini (2020, CoDEX trial) |

Severe |

N = 299 I: 151 C: 148

|

I: 20 mg intravenously once daily for 5 days, followed by 10 mg intravenously once daily for additional 5 days or until ICU discharge, whichever occurred first, plus standard care.

C: Standard care only |

|

Jamaati (2021) |

Mild to moderate |

N = 50 I: 25 C: 25 |

I: Intravenous dexamethasone at a dose of 20 mg/day from day 1–5 and then at 10 mg/day from day 6–10, plus standard care

C: Standard care only |

|

Horby (2021, RECOVERY trial) |

Mild to severe (sub-group analyses for mild, moderate, and severe disease) |

N = 6425 I: 2104 C: 4321 |

I: 6 mg given once daily for up to 10 days, plus standard care

C: Standard care only |

|

Hydrocortisone |

|||

|

Angus (2020, REMAP-CAP) |

Severe |

N = 614 I: 137 II: 146 Control: 101

|

I: fixed-dose hydrocortisone: Patients received a fixed dose of intravenous hydrocortisone, 50 mg or 100 mg, every 6 hours for 7 days.

II: shock-dependent hydrocortisone: intravenous hydrocortisone, 50 mg, every 6 hours while in shock for up to 28 days.

C: Standard care only |

|

Dequin (2020, CAPECOVID trial) |

Moderate to severe |

N = 149 I: 76 C: 73

|

I: Continuous intravenous infusion of hydrocortisone 200mg/day. Treatment was continued at 200mg/d until day 7 and then decreased to 100 mg/d for 4 days and 50 mg/d for 3 days, for a total of 14 days. If the patient’s respiratory and general status had sufficiently improved by day 4, a short treatment regimen was used (200mg/d for 4 days, followed by 100mg/d for 2 days and then 50 mg/d for the next 2 days, for a total of 8 days).

C: Continuous intravenous infusion of saline, plus standard care |

|

Munch (2021, COVID STEROID trial) |

Moderate to severe |

N = 30 I: 16 C: 14

|

I: Intravenous hydrocortisone (200 mg/day) for 7 days or until hospital discharge in addition to standard care; continuous infusion over 24 hrs or as bolus injections every 6 hrs (50 mg per bolus).

C: Intravenous saline solution, plus standard care |

|

Methylprednisolone |

|||

|

Jeronimo (2020, Metcovid trial) |

Moderate to severe |

N = 397 I: 195 C 202

|

I: Intravenous sodium succinate MP (0.5 mg/kg), twice daily for 5 days

C: Intravenous saline solution, plus standard care |

|

Edalatifard (2020) |

Moderate to severe |

N = 68 I: 34 C: 34

|

I: Intravenous methylprednisolone (MP) Injection (250 mg/day for 3 days), plus standard care

C: Standard care and no methylprednisolone or other glucocorticoids |

|

Corral-Gudino (2021, GLUCOCOVID trial) |

Unclear |

N = 64 I: 35 C: 29

|

I: Intravenous methylprednisolone (MP) 40 mg, twice a day, for 3 days and then 20 mg, twice a day, for 3 more days.

C: Standard care |

|

Solanich (2021) |

Moderate to severe |

N = 55 I: 27 C: 28 |

I: Methylprednisolone pulses (120 mg/day) and tacrolimus, plus standard of care

C: Standard care |

|

Tang (2021) |

Moderate to severe, partially unclear |

N = 86 I: 43 C: 43

|

I: 1 mg/kg per day of methylprednisolone administered intravenously for 7 days, plus standard care

C: intravenous saline solution, plus standard care |

*Disease severity categories:

- mild disease (no supplemental oxygen);

- moderate disease (supplemental oxygen: low flow oxygen, non-rebreathing mask);

- severe disease (supplemental oxygen: high flow oxygen [high flow nasal cannula (HFNC)/Optiflow], continuous positive airway pressure [CPAP], non-invasive ventilation [NIV], mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [ECMO or ECLS]).

N: Total sample size; I: Intervention; C: Control

Results – Systemic corticosteroids in hospitalized COVID-19 patients

Mortality (crucial)

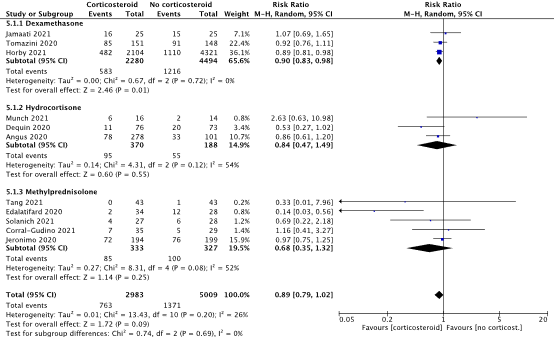

All of the included RCTs investigated the effect of corticosteroids on mortality. Figure 1 shows the overall pooled estimate and sub-group analysis by overall disease severity. Overall, there were 763 observed deaths in the corticosteroids group (763/2983, 25.6%) and 1371 observed deaths in the group not receiving corticosteroids (1371/5009, 27.4%). The pooled relative risk was 0.89 (95% CI 0.79 to 1.02), with the summary point estimate favoring the use of corticosteroids. Relative risks for mortality in all individual studies are shown in Figure 1 as well. The pooled risk difference was -4.33% (95% CI -8.58% to -0.07%), with the summary point estimate favoring the use of corticosteroids. When using a risk difference of 3% as a minimally clinically important difference, the pooled point estimate shows a clinically relevant difference.

When studies administering dexamethasone were pooled, 583 deaths were observed (583/2280, 25.6%) in the dexamethasone group compared to 1216 (1216/4494, 27.1%) in the control group. The relative risk was 0.90 (95%CI: 0.83 to 0.98) and the risk difference was -2.83% (95%CI: -5.00% to -0.66%), with the point estimates favoring the use of dexamethasone. The pooled risk difference point estimate was not larger than the -3% minimally clinically important difference, indicating that the point estimate is not clinically relevant. For hydrocortisone, 95 deaths were observed (95/370, 25.7%) compared to 55 (55/188, 29.3%) in the control group. This resulted in a relative risk of 0.84 (95%CI: 0.47 to 1.49) and a risk difference of -3.49 (95%CI: -17.40% to 10.42%). The pooled point estimates favored the use of methylprednisolone. In studies administering methylprednisolone a total of 85 deaths were observed (85/333, 25.5%) in the methylprednisolone group, compared to 100 (100/327, 30.6%) in the control group. This resulted in a pooled relative risk of 0.68 (95%CI: 0.35 to 1.32) and a risk difference of -6.86% (95%CI: -16.88% to 3.17%), where both point estimates favored the use of methylprednisolone. When using a risk difference of 3% as a minimally clinically important difference, the pooled point estimates for hydrocortisone and methylprednisolone show a clinically relevant difference albeit there are wide confidence intervals around these estimates.

Figure 1: Mortality (28-30days) in hospitalized patients.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Tomazini (2020) observed 85 death (85/151, 56.3% in the dexamethasone group, compared to 91 death (91/148, 61.5%) in the usual care group. This resulted in a risk difference of -5.2% (95% CI -1.6% to 5.9%). The point estimate favors dexamethasone.

Jamaati (2021) observed 16 deaths (16/25, 64.0%) in the dexamethasone group, while 15 deaths (15/25, 60.0%) were observed in the usual care group. The corresponding risk difference was 4% (95% CI: -22.9% to 30.9%).

Jeronimo (2020) included suspected cases and reported the 7-day mortality (16.5% vs. 23.6%) and 14-day mortality (27.3% vs. 31.7%) in the methylprednisolone vs. placebo groups. On day 28 the mortality increased to 72 observed deaths (72/194, 37.1%) in the methylprednisolone group compared to 76 (76/199, 38.2%) observed deaths in the placebo group. This resulted in a risk difference of -1.1% (95% CI -10.7% to 8.5%), with the point estimates favoring methylprednisolone.

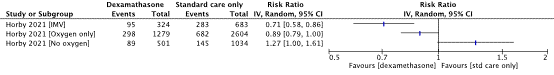

Horby (2021) observed 482 deaths (482/2104, 22.9%) in the dexamethasone group, compared to 1110 deaths (1110/4321, 25.7%) in the usual care group. The corresponding risk difference was -2.8% (95% CI: -5% to -0.6%). Horby (2021) also presented sub-group analyses based on respiratory support status at randomization (see Figure 2). In this figure the risk ratio is depicted, in line with the other studies. The original article displays the rate ratio.

Figure 2: Mortality (day 28) by respiration support status at randomization in hospitalized COVID-19 patients (Horby, 2021) in hospitalized patients.

CI: confidence interval

Angus (2020) observed 41 in-hospital deaths in the fixed-dose hydrocortisone-group (41/137, 30%; RD = -2.8% [95% CI -14.7% to 9.2%]), while in the shock-dependent hydrocortisone-group 37 (37/141, 26%; RD = -6.4% [95% CI -18.1% to 5.3%]) in-hospital deaths were observed compared to 33 deaths (33/101, 32.7%) in the no-hydrocortisone group. Together, 78 deaths occurred (78/278, 28%) in both hydrocortisone groups. In the control group 33 (33/101, 33%) in-hospital deaths occurred (RD = -4.6% [95% CI -15.2% to 6.0%]; favoring hydrocortisone).

Dequin (2020) included both suspected and confirmed cases. Over the course of 21 days, 11 deaths (11/76, 14.5%) were observed in the hydrocortisone-group, compared to 20 deaths (20/73, 27.4%) in the placebo-group. This resulted in a risk difference of -12.9% (95% CI -25.9% to 0.0%), with the point estimate favoring hydrocortisone.

Munch (2021) solely included confirmed cases and reported the all-cause mortality on both day 28 and day 90. Over the course of 28 days, 6 deaths (6/16, 37.5%) were observed in the hydrocortisone-group, compared to 2 deaths (2/14, 14.3%) in the placebo-group. The risk difference was 23.2% (95% CI -6.8% to 53.2%), favoring placebo. On day 90, the observed deaths increased to 7 (7/16, 44%) and 3 (3/14, 21%), respectively.

Jeronimo (2020) included suspected cases and reported the 7-day mortality (16.5% vs. 23.6%) and 14-day mortality (27.3% vs. 31.7%) in the methylprednisolone vs. placebo groups. On day 28 the mortality increased to 72 observed deaths (72/194, 37.1%) in the methylprednisolone group compared to 76 (76/199, 38.2%) observed deaths in the placebo group. This resulted in a risk difference of -1.1% (95% CI -10.7% to 8.5%), with the point estimates favoring methylprednisolone.

Edalatifard (2020) recruited confirmed cases only and reported the mortality for circa up to 28 days in both groups (approximated from a figure). Two deaths (2/34, 5.9%) were observed in the methylprednisolone group, compared to twelve deaths (12/28, 42.9%) in the standard care-only group. This resulted in a risk difference of -37% (95% CI -56.9% to -17%), with the point estimates favoring methylprednisolone.

Corral-Gudino (2021) recruited confirmed cases only. There were 7 deaths (7/35, 20%) observed in the methylprednisolone group on day 28, compared to 5 (5/29, 17.2%) in the standard care-only group. This resulted in a risk difference of 2.8% (95% CI -16.3% to 21.9%), with the point estimates favoring no methylprednisolone.

Solanich (2021) recruited confirmed cases only. Both COVID-related mortality and all-cause mortality were reported. For COVID-related mortality was reported for day 28 (11.1% vs. 14.3%) and for day 56 (14.8% vs. 14.3%) in the methylprednisolone group vs. standard care-only group, respectively. For the 28-day all-cause mortality, 4 deaths were observed (4/27, 14.8%) in the methylprednisolone group, compared to 6 deaths (6/28, 21.4%) in the standard care-only group. This resulted in a risk difference of -6.6% (95% CI -26.9% to 13.7%), with the point estimates favoring methylprednisolone. At day 56 there were 5 observed deaths (18.5%, methylprednisolone) compared to 6 deaths (21.4%, standard care-only) for mortality.

Tang (2021) recruited confirmed cases only and reported the in-hospital mortality up to 14 days. No deaths were observed in the methylprednisolone group, compared to one death (1/43, 2.3%) in the placebo and standard care group. This resulted in a risk difference of -2.3% (95% CI -16.9% to 3.2%), with the point estimates favoring methylprednisolone.

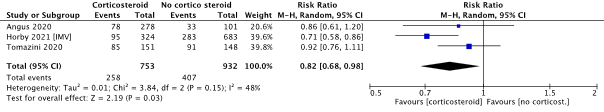

Systemic corticosteroid use in patients with severe disease

The RECOVERY trial (Horby, 2021), included a subgroup analysis reporting the mortality in patient receiving invasive mechanical ventilation at baseline (IMV, n=1007), see Figure 2. The working group considered this sub-group as having severe disease. The risk difference calculated from the reported events was -12.1% (95% CI -18.3% to -5.9%). This sub-group was furthermore used in the meta-analysis to pool the effect of corticosteroids on mortality in the severe disease group along with the data from Angus (2020) and Tomazini (2020). Figure 3 shows the pooled relative risk in the severe disease group regardless of the type of corticosteroid provided (Angus, 2020; Horby, 2021; Tomazini, 2020). The corresponding pooled risk difference was -9.18% (95% CI: -14.13% to -4.23%), favoring the use of corticosteroids. The pooled point estimate shows a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 3: Mortality in hospitalized patients with severe disease.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Systemic corticosteroid use in patients with moderate disease

The only RCT including only moderate disease or specifically reporting the moderate disease subgroup seemed to be the RECOVERY trial (Horby, 2021). Here, the mortality was reported in a sub-group of patients receiving oxygen therapy only at randomization while receiving dexamethasone (n=1279) or usual care only (n=2604) during the study period. See Figure 2 for the relative risk in this sub-group. The risk difference was -2.9% (95% CI: -5.8% to -0.0%), indicating with the point estimate that there is no clinically relevant difference.

Systemic corticosteroid use in patients with mild disease

Horby (2021) also presented the results of the sub-group not receiving any oxygen support at randomization in the RECOVERY trial. The working group considered this subgroup as having mild disease. In this sub-group (n=1535) the risk difference calculated from the reported events was 3.7% (95% CI -0.2% to 7.7%), with the point estimate favoring standard care. The point estimate shows a clinically relevant difference. The relative risks of this subgroup receiving no oxygen at randomization is reported in Figure 2. Horby (2021) was the only study that included patients with mild disease.

Level of evidence of the literature

The certainty of evidence started as high since the body of evidence consisted solely of RCTs. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality (overall) was downgraded by 1 level due to imprecision (reason: the confidence interval of the pooled risk difference crossed the predefined border of clinical relevance [RD 3% points difference]). We did not downgrade for study limitations (not downgraded for risk of bias: lack of blinding probably does not affect a hard outcome such as mortality). Publication bias was not assessed. The level of evidence for the outcome mortality in hospitalized patients is moderate.

The certainty of evidence started as high since the body of evidence consisted solely of RCTs. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality (severe disease only) was not downgraded. We did not downgrade for study limitations (not downgraded for risk of bias: lack of blinding probably does not affect a hard outcome such as mortality) and imprecision (reason: using the risks in both groups [34.3% vs 43.7%] and the observed proportion in both groups [q1=0.447, q2=0.553], the calculated needed sample size is n=897 [using: alpha=0.05, beta=0.2]). Publication bias was not assessed. The level of evidence for the outcome mortality (severe disease) in hospitalized patients is high.

The certainty of evidence started as high since the body of evidence consisted solely of RCTs. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality (moderate disease only) was downgraded 1 level due to imprecision (reason: confidence interval of the risk difference crosses the clinical border of 3%). We did not downgrade for study limitations (not downgraded for risk of bias: lack of blinding probably does not affect a hard outcome such as mortality) and publication bias was not assessed. The level of evidence for the outcome mortality (moderate disease) in hospitalized patients is moderate.

The certainty of evidence started as high since the body of evidence consisted solely of RCTs. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality (mild disease only) was downgraded by 2 levels due to imprecision (reason: using the risks in both groups [17.8% vs 14.0%] and the 1:2 allocation scheme [q1=0.33, q2=0.67], the calculated needed sample size in the intervention group is n=1137 and for the control group n= 2308 [using: alpha=0.05, beta=0.2]). We did not downgrade for study limitations (not downgraded for risk of bias: lack of blinding probably does not affect a hard outcome such as mortality). Publication bias was not assessed. The level of evidence for the outcome mortality (mild disease) in hospitalized patients is low.

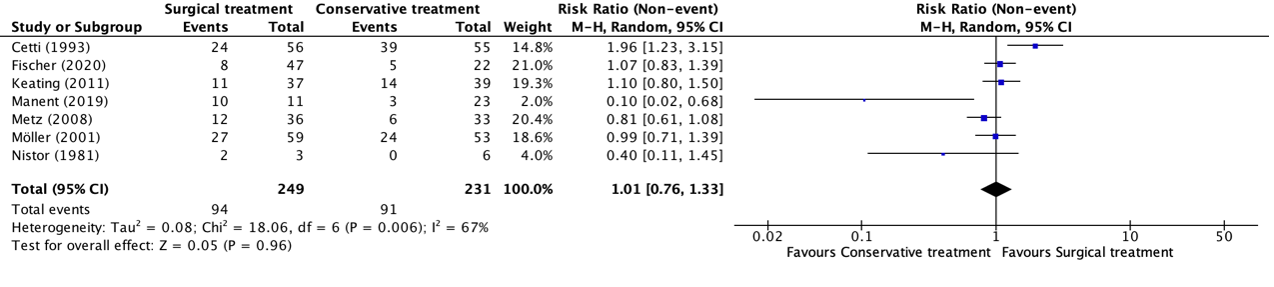

Extensive respiratory support

Five RCTs reported the need for extensive respiratory support (Corral-Gudino, 2021; Dequin, 2020; Horby, 2021; Jamaati, 2020; Jeronimo, 2020). Figure 4 shows an overview of the relative risks.

Figure 4: Need for extensive respiratory support in hospitalized patients.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; IV: Invasive (mechanical) ventilation; NIV: Non-invasive ventilation

Tomazini (2020), including confirmed or suspected cases, reported the number of days on mechanical ventilation. The dexamethasone group had a mean duration of 12.5 days (95% CI 11.2 to 13.8) compared to 13.9 days (95% CI 12.7 to 15.1). The adjusted mean difference was -1.54 days (95%CI -3.24 to 0.12, adjusted for age and baseline PaO2/FiO2 ratio).

The relative risk from the data reported in Jamaati (2021) was 1.18 (95% CI 0.66 to 2.11) and the risk difference was 8% (95% CI -19.6% to 35.6%) with the point estimate favoring standard care, which is considered a clinically relevant difference. Jamaati (2021) also reported the need for non-invasive mechanical ventilation and observed that 23 patients (23/25, 92%) in the dexamethasone-group and 24 patients (24/25, 96%) in the standard care only-group needed non-invasive ventilation (RR = 0.96, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.10). The risk difference was -4% (95% CI -17.1% to 9.1%), where the point estimate does not indicate a clinically relevant difference.

Horby (2021) included both suspected and confirmed cases resulting in a relative risk of 0.75 (95% CI 0.61 to 0.93) and a risk difference of -2% (95% CI -3.4% to -0.6), with the point estimates favoring dexamethasone while not being considered a clinically relevant difference.

Angus (2020) reported the respiratory support-free days in the sample of both suspected and confirmed cases. The mean adjusted odds ratio in the fixed dose hydrocortisone group compared to the no-hydrocortisone group was 1.45, with the point estimate favoring hydrocortisone. For the shock dependent hydrocortisone group the mean adjusted odds ratio was 1.31 compared to the no-hydrocortisone group, with the point estimate favoring hydrocortisone.

Dequin (2020) included both suspected and confirmed cases. Respiratory support status on day 21 was reported. In the hydrocortisone group 17 patients (17/76, 22.3%) had mechanical ventilation on day 21, compared to 17 patients (17/73, 23.3%) in the placebo group (RR = 0.96 [95% CI 0.53 to 1.73]; RD = 0.9% [95% CI -14.4% to 12.6%]; favoring hydrocortisone, no clinically relevant difference). High-flow oxygen therapy on day 21 was provided for 3 patients (3/76, 4%) in the hydrocortisone group, while none of the patients received this type of support in the placebo group (RD = 4% [95% CI -1.1% to 9.0%]; favoring placebo, no clinically relevant difference).

Jeronimo (2020) only recruited suspected cases and reported the need for invasive mechanical ventilation until day 7. In the methylprednisolone group, 18 patients (18/93, 19.4%) needed invasive mechanical ventilation, compared to 16 patients (16/95, 16.8%) in the placebo group. The calculated relative risk from this data was 1.15 (95% CI 0.62 to 2.11) and the risk difference was 2.6% (95% CI -7.5% to 14.7%), with the point estimates favoring the placebo group while not indicating a clinically relevant difference.

Edalatifard (2020) recruited confirmed cases only and reported the need for oxygen therapy on day 3. Oxygen therapy was needed in 28 patients (28/34, 82.4%) in the methylprednisolone group versus 26 patients (26/28, 92.8%) in the standard care-only group. The need for oxygen therapy was a composite of the need for nasal cannula, mask oxygen, reservoir mask, non-invasive ventilation, and invasive ventilation. The calculated relative risk from this data was 0.89 (95% CI 0.74 to 1.07) and the risk difference was -10.5% (95% CI -26.5% to 5.5%), with the point estimates favoring the methylprednisolone group and indicating a clinically relevant difference.

Corral-Gudino (2021) reported the progression of respiratory insufficiency which required non-invasive ventilation. Requirement of non-invasive ventilation due to progression was observed in 10 patients (10/35, 28.6%) in the methylprednisolone group compared to 7 patients (7/29, 24.1%) in the standard care-only group. The calculated relative risk from this data was 1.18 (95% CI 0.52 to 2.72) and the risk difference was 4.4% (95% CI -17.2% to 26.0%), with the point estimate favoring the standard-care only group while not indicating a clinical relevant difference.

Solanich (2021) included confirmed cases only and reported the duration of oxygen support, the need for high-flow oxygen or ventilatory support, and the duration of high-flow or ventilatory support. The methylprednisolone group had a median of 11.0 days (IQR: 8.0-19.5) of oxygen support compared to 13 days (IQR: 7.75-23.0) in the standard care-only group. High-flow or ventilatory support was provided to 14 patients in the methylprednisolone group (14/27, 51.9%) versus 18 patients (18/28, 64.3%) in the standard care-only group. The calculated relative risk from this data was 0.81 (95% CI 0.51 to 1.27) and the risk difference was -12.4% (95% CI -38.3% to 13.5%), with the point estimates favoring the methylprednisolone group. The risk difference point estimate indicates a clinically relevant difference. Median duration of high-flow or ventilatory support was 8 days (IQR: 5.0-27.2) in the methylprednisolone group versus a median of 6.5 days (IQR: 4.25-14.20) in the standard care only-group.

Tang (2021) recruited confirmed cases only and reported the need for respiratory support therapies. Patients received high-flow oxygen (4.6% vs. 2.3%), non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (0% vs. 2.3%), invasive mechanical ventilation (4.6% vs. 2.3%), and/or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (4.6% vs. 0%) in the methylprednisolone group versus the placebo group, respectively.

Level of evidence of the literature

The certainty of evidence started as high since the body of evidence consisted solely of RCTs. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure extensive respiratory support was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (1 level for risk of bias, several (potential) flaws in the included studies: lack of blinding of several roles (e.g. open label, or health care providers not blinded), ITT analyses were not followed); number of included patients (1 level for imprecision: relatively small number of patients in the study); publication bias was not assessed. The level of evidence for the outcome respiratory support in hospitalized patients is low.

Duration of hospitalization (important)

Horby (2021) found that patients receiving dexamethasone had a shorter length of stay (median of 12 days) compared to patients receiving the usual care only (median of 13 days), however this is not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Jamaati (2021) included confirmed SARS-CoV2 cases and found a median duration of hospitalization of 11 days (IQR: 6 to 16) in the dexamethasone-group (n=25) compared to 6 days (IQR: 4 to 9) in the standard care only-group (n=25). In the subgroup that survived, the median duration of hospitalization for the dexamethasone-group (n=9) was 11 days (IQR: 9 to 21) compared to 8.5 days (IQR: 5 to 13) in the standard care only-group (n=10). This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Angus (2020) reported the hazard ratio of duration of hospitalization in the sample of both suspected and confirmed cases. The median adjusted hazard ratio in the fixed dose hydrocortisone group compared to the control group was 0.97 (95% credible interval: 0.72 to 1.32), with the point estimate favoring hydrocortisone. For the shock dependent hydrocortisone group the median adjusted hazard ratio was 0.93 (95% credible interval: 0.69 to 1.26) compared to the hydrocortisone group, with the point estimate favoring no-hydrocortisone.

Jeronimo (2020) included suspected cases only. The median days of hospitalization was 10 days (IQR 7-13) in the methylprednisolone group. In the placebo group, the median duration of hospitalization was 9 days (IQR: 7-11). No significant (p=0.296) and clinically relevant differences between groups were found.

Solanich (2021) included confirmed cases only and observed a median duration of hospitalization of 13 days (IQR: 8.5-21) in the methylprednisolone group, compared to a median of 14 days (IQR: 9-22.5) in the standard care group. No significant (p=0.933, Wilcoxon test) and clinically relevant differences between groups were found.

Tang (2021) included confirmed cases only. The median duration of hospitalization was 17 days (IQR: 13-22) and 13 days (IQR: 10-20) in the methylprednisolone and placebo groups, respectively. No significant differences between groups were found (p=0.314, HR = 1.3 [95% CI 0.84-2.00]), however the difference in median duration (i.e. 4 days) is considered to be clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature

The certainty of evidence started as high since the body of evidence consisted solely of RCTs. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure duration of hospitalization was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (2 levels for risk of bias: potential risk of bias since four trials had no or unclear blinding of health care providers). Publication bias was not assessed. The level of evidence for the outcome respiratory support (need for respiratory support therapies) in hospitalized patients is low.

Time to clinical improvement (important)

Solanich (2021) included confirmed cases only and reported the number of patients reaching clinical stability. Here, clinical stability was defined as meeting all 4 criteria for 48 hours: body temperature of 37.5°C or less; PaO2/FiO2 ratio over400 and/or SpO2/FiO2 ratio over 300; and a respiratory rate of 24 rpm or less. In the methylprednisolone group 21 patients (21/27, 77.8%) achieved clinical stability at day 56 compared to 22 patients (22/28, 78.6%) in the standard care-only group (RR = 1.04, 95% CI 0.38 to 2.82; RD = 0.8%, 95% CI -21.0% to 22.6%; point estimates favour methylprednisolone). Median time to reach clinical stability in the methylprednisolone group was 10 days (IQR: 7-13) versus 11 days (IQR: 8-18.8) in the standard care-only group (HR = 0.73, 95% CI 0.39-1.37), which indicates no clinically relevant difference.

Tang (2021) included confirmed cases and reported the number of patients reaching clinical cure. Clinical cure was defined as meeting all of the following criteria: the clinical signs and symptoms of COVID-19 are improved or alleviated (i.e. body temperature for 3 consecutive days, respiratory symptoms improved significantly, CT images showed absorption and/or consolidation of bilateral ground-glass opacification), and no additional treatment was necessary. At day 14 after randomization there were 22 patients (22/43, 51.2%) in the methylprednisolone group achieving clinical cure compared to 25 patients (25/43, 58.1%) in the placebo group (RR = 1.17, 95% CI 0.73-1.86; RD = 7.0%, 95% CI -14.0% to 28.0%; point estimates favor placebo). The median time to achieve clinical cure was 14 days (IQR: 10-19) versus 12 days (IQR: 9-17) in the methylprednisolone and placebo groups, respectively (HR = 1.04, 95% CI 0.67-1.62), which indicates no clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence of the literature

The certainty of evidence started as high since the body of evidence consisted solely of RCTs. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure time to clinical improvement was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations (1 level for risk of bias: open-label study, lack of blinding of care providers) and number of included patients (2 levels for imprecision: very low number of included patients); Publication bias was not assessed. The level of evidence for the outcome time to clinical improvement in hospitalized patients is very low.

Corticosteroids in non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients

No studies were found investigating the effect of corticosteroids in non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Results

No studies were found investigating the effect of corticosteroids on mortality, respiratory support, duration of hospitalization, or time to clinical improvement in non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Level of evidence of the literature

GRADE assessment could not be performed. No studies were found investigating the effect of corticosteroids on mortality, respiratory support, duration of hospitalization, or time to clinical improvement in non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effectivity of treatment with corticosteroids compared to treatment without corticosteroids in patients with COVID-19?

PICO 1

P: hospitalized with COVID-19 (subgroups mild, moderate, severe)

I: systemic corticosteroid use + standard care

C: standard care only or placebo treatment + standard care

O: 28-30 day mortality (if not available, any other reports of mortality), extensive respiratory support, duration of hospitalization, time to clinical improvement

PICO 2

P: non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19

I: systemic corticosteroid use + standard care