Prognostische factoren voor uitkomst bij COVID-19 patiënten met cardiovasculaire risicofactoren of cardiale ziekte

Uitgangsvraag

In which proven COVID-19 patients with cardiovascular risk factors or underlying cardiovascular disease should one be alert to a poor outcome?

Aanbeveling

Beschouw patiënten met cardiovasculaire risicofactoren en/of cardiovasculaire aandoeningen in de COVID pandemie als een risicogroep; patiënten met hartfalen hebben hierbinnen mogelijk een groter risico op overlijden. Zorgverleners en patiënten volgen in de vigerende adviezen en preventiemaatregelen vanuit de overheid en zorginstituten de aanwijzingen voor de risicogroepen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

De kwaliteit van het bewijs van de geïncludeerde studies is overwegend laag tot zeer laag. De GRADE systematiek is gevolgd om de kwaliteit van het bewijs te beoordelen. Deze is hier dan ook gevolgd. In een nieuwe situatie (zoals COVID) is het logisch dat de meeste studies nog niet kunnen voldoen aan de strenge eisen die aan studies van hoge kwaliteit worden gesteld. De GRADE methodiek zet de kwaliteit van het bewijs echter af tegen de best mogelijke kwaliteit en niet tegen de best mogelijke kwaliteit in de huidige situatie. De GRADE systematiek geeft het vertrouwen weer in de schatting van het effect van een interventie. Wanneer de modules en de search worden geüpdate zijn er hopelijk studies van betere kwaliteit beschikbaar en kan het niveau van de kwaliteit van het bewijs hierop worden aangepast.

Op basis van de huidige literatuursamenvatting kunnen alleen conclusies worden getrokken waarin weinig vertrouwen wordt gegeven aan de correctheid van de schatting van het prognostisch effect van cardiovasculaire risico factoren of cardiovasculaire aandoeningen op mortaliteit. Hoewel op basis van de resultaten van de gerapporteerde modellen geconcludeerd zou kunnen worden dat BMI (gecorrigeerd voor leeftijd) statistisch gezien (klinische relevantie onbekend) een voorspeller zou kunnen zijn van mortaliteit, kan deze conclusie op dit moment niet worden ondersteund met bewijskracht vanuit de geselecteerde literatuur. De bewijskracht van de gevonden studies is zeer laag, onder andere door beperkingen in de methodologische opzet van de gevonden studies. Er is behoefte aan kwalitatief goed opgezette studies, welke gemaakte voorspellende modellen valideren in een Westerse populatie. In de literatuur werd daarom geen bewijs gevonden voor voorspellers die een rol zouden kunnen spelen bij mortaliteit in patiënten met COVID-19, wanneer wordt gecorrigeerd voor leeftijd.

Wanneer prognostische factoren kunnen worden vastgesteld, en deze gebruikt wensen te worden ten behoeve van klinische besluitvorming, maakt men gebruik van een beoordelingsmodel. Het is verstandig de voorspellende waarde van het te ontwikkelen beoordelingsmodel te optimaliseren door het te ontwikkelen model intern en extern te valideren en waar nodig te verbeteren. De effectiviteit van de toepassing van het ontwikkelde model wordt bij voorkeur getest in de praktijk door het effect op patiënt gerelateerde uitkomstmaten te meten alvorens het als standaard beoordelingsmiddel wordt ingezet.

CAPACITY

CAPACITY is een internationale registratie van patiënten met COVID-19 op basis van het ISARIC WHO CRF, aangevuld met informatie over specifieke cardiovasculaire parameters (https://capacity-covid.eu/). CAPACITY is in het voorjaar van 2020 gestart en bevat gegevens van 13034 patiënten uit 13 landen, afkomstig van 79 registrerende centra. CAPACITY bevat omvangrijke informatie over patiënten met COVID, omdat ongeveer 40% van de in Nederland opgenomen COVID19 patiënten in de registratie is opgenomen (n = 5524).

De peer-reviewed publicatie van CAPACITY over het onderwerp van deze module is momenteel in voorbereiding. De resultaten van CAPACITY kunnen daarom kunnen nog niet worden meegenomen bij het literatuuronderzoek, maar bij de overwegingen worden wel de voorlopige resultaten van CAPACITY meegenomen. De peer-reviewed publicatie over het onderwerp van deze module wordt binnenkort verwacht en bij een update van de module zal de publicatie in het literatuuronderzoek worden meegenomen.

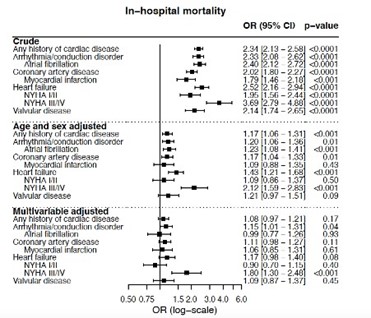

Figuur 1 Associaties tussen cardiale voorgeschiedenis en in-hospital mortaliteit uit de CAPACITY registry en data uit de LEOSS registry gezamenlijk (n=10712)

Een vergelijking van de basale kenmerken tussen patiënten met een cardiale voorgeschiedenis en patiënten zonder cardiale voorgeschiedenis laat zien dat patiënten met een cardiale voorgeschiedenis ouder zijn en meer cardiale risicofactoren en co-morbiditeit hebben.

De opnameduur op de Intensive Care en in het ziekenhuis zijn voor beide groepen vergelijkbaar. Patiënten met een cardiale voorgeschiedenis ontwikkelen vaker een acute nierinsufficiëntie tijdens de ziekenhuis opname en hebben vaker nierfunctiestoornissen in de voorgeschiedenis. In de vergelijking valt op dat een groter deel van de patiënten met een cardiale voorgeschiedenis komt te overlijden tijdens een ziekenhuisopname vanwege COVID-19 infectie.

Leeftijd, geslacht en algemene “frailty” lijken een belangrijke voorspellende waarde te hebben.

Preliminaire resultaten van Nederlandse data uit de CAPACITY registry geven aan dat bij patiënten met een cardiale co-morbiditeit, hartfalen geassocieerd lijkt te zijn met een verhoogd risico op op mortaliteit gedurende de opname. Analyse van gecombineerde data (n= 10712) uit de CAPACITY registry en data uit de LEOSS registry (Lean Europeaan Open Survey on SARS-CoV-2 infected patients; dit is een multicenter prospectieve cohort studie met als primaire doel het identificeren van onafhankelijke predictoren voor uitkomst bij patiënten gediagnostificeerd met SARS-CoV2) laat zien dat er bij patiënten met een cardiale co-morbiditeit, na adjusteren voor leeftijd, geslacht, BMI, hypertensie, CKD, COPD en diabetes, een significante associatie bestaat tussen NYHA III/IV hartfalen en in-hospital mortaliteit.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Aan patiënten met cardiovasculaire risicofactoren en/of cardiovasculaire aandoeningen kan meegegeven worden dat zij in de COVID-pandemie de aanwijzingen vanuit de overheid, zorgverleners en zorginstituten over preventieve maatregelen en testindicaties volgen die betrekking hebben op de risicogroepen.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Niet van toepassing

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De aanbeveling is aanvaardbaar en haalbaar aangezien de COVID-infectie nadrukkelijk aandacht heeft en krijgt vanuit de overheid en zorgverleners. In de landelijke adviezen wordt expliciet aandacht besteedt aan de risicogroepen.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Patiënten met cardiovasculaire risicofactoren en/of cardiovasculaire aandoeningen zijn een kwetsbare groep op het gebied van infectieziekten. Er zijn geen aanwijzingen gevonden dat dit in de COVID-epidemie anders ligt. Overtuigende bewijskracht voor het effect van cardiovasculaire risicofactoren en/of cardiovasculaire aandoeningen op mortaliteit en ernst van het ziektebeloop bij COVID-19 infectie ontbreekt in de samengevatte literatuur. Echter, de aanwijzingen uit de CAPACITY registry dat patiënten met een cardiale voorgeschiedenis ouder zijn en meer co-morbiditeit hebben, dat leeftijd en frailty belangrijke voorspellers van mortaliteit zijn en dat meer patiënten met een cardiale voorgeschiedenis overlijden aan COVID-19 dan patiënten zonder cardiale voorgeschiedenis, worden als belangrijk gezien in het identificeren van deze patiëntengroep als een risicogroep. Derhalve wordt geadviseerd om de patiënten met cardiovasculaire risicofactoren en/of cardiovasculaire aandoeningen in de COVID-epidemie te beschouwen als risicogroep en de daarvoor vigerende adviezen en preventiemaatregelen te volgen. Bij patiënten met cardiale co-morbiditeit lijkt vooral hartfalen (NYHA III/IV) geassocieerd met mortaliteit. Er zijn momenteel echter onvoldoende aanwijzingen gevonden die voor specifieke risicofactoren of aandoeningen aanzetten tot extra maatregelen bovenop de hiervoor genoemde.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

De COVID-19 pandemie roept wereldwijd diverse vragen op bij zorgverleners, onderzoekers en patiënten. Patiënten met cardiovasculaire risicofactoren en/of cardiovasculaire aandoeningen zijn een kwetsbare groep op het gebied van infectieziekten. Dit is onder meer te verklaren door de effecten van de diverse cardiovasculaire risicofactoren op de immunologische functie en de betrokkenheid van het immuunsysteem bij het ontstaan van cardiovasculaire aandoeningen. Kennis over het risico op een ernstig ziektebeloop en overlijden bij deze groep patiënten is van belang voor een passende response op het gebied van voorzorgsmaatregelen, monitoring en therapie. Het tempo waarin de pandemie zich voltrekt, de globale verschillen in opname criteria, het ontbreken van voldoende testcapaciteiten en het ontbreken van systematische datacollectie zijn van invloed op de beschikbaarheid en kwaliteit van wetenschappelijke literatuur die inzicht kan verschaffen in de prevalentie van cardiovasculaire risicofactoren en cardiovasculaire aandoeningen bij COVID-19 patiënten. Gegeven het hiervoor genoemde is het zinvol om met regelmaat een kritische selectie te maken van beschikbare literatuur over de voorspellende waarde van cardiovasculaire risicofactoren en cardiovasculaire aandoeningen op het ziektebeloop en mortaliteit van COVID-19 patiënten en door middel van passende analyse modellen de data te doorgronden.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Mortality predicted by prognostic factors measured during hospital stay

|

Very low GRADE |

We are unsure whether Body Mass Index is a predictor of mortality in COVID-19 patients admitted to hospital, adjusted for age.

Sources: Cummings, 2020; Giacomelli, 2020; Klang, 2020; Palaiodimos, 2020; Petrilli, 2020 |

|

Very low GRADE |

We are unsure whether smoking is a predictor of mortality in COVID-19 patients admitted to hospital, adjusted for age.

Sources: Klang, 2020; Palaiodimos, 2020; Petrilli, 2020 |

|

Very low GRADE |

We are unsure whether hypertension is a predictor of mortality in COVID-19 patients admitted to hospital, adjusted for age.

Sources: Cummings, 2020; Gao, 2020; Klang, 2020; Petrilli, 2020 |

|

Very low GRADE |

We are unsure whether diabetes is a predictor of mortality in COVID-19 patients admitted to hospital, adjusted for age.

Sources: Cummings, 2020; Klang, 2020; Palaiodimos, 2020; Petrilli, 2020 |

|

Very low GRADE |

We are unsure whether coronary artery disease or congestive heart failure is a predictor of mortality in COVID-19 patients admitted to hospital, adjusted for age.

Sources: Chen, 2020; Cummings, 2020; Klang, 2020; Palaiodimos, 2020; Petrilli, 2020 |

|

Very low GRADE |

We are unsure whether cerebrovascular disease is a predictor of mortality in COVID-19 patients admitted to hospital, adjusted for age.

Sources: Chen, 2020; Wang, 2020 |

|

Very low GRADE |

We are unsure whether heart failure is a predictor of mortality in COVID-19 patients admitted to hospital, adjusted for age.

Sources: Klang, 2020; Palaiodimos, 2020; Petrilli, 2020 |

|

- GRADE |

We cannot conclude which other cardiovascular risk factors, cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular history can predict mortality in COVID-19 patients due to lack of studies testing multivariable models taking age into account. |

Hospital admission predicted by prognostic factors measured during hospital stay

|

- GRADE |

We cannot conclude which cardiovascular risk factors, cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular history can predict hospital admission in COVID-19 patients due to lack of studies testing multivariable models taking age into account. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Chen (2020), Giacomelli (2020) and Wang (2020) measured candidate factors during hospital stay and measured mortality outcome as endpoint. Cummings (2020), Gao (2020), Klang (2020) and Palaiodimos (2020) measured candidate factors during hospital stay and measured in-hospital mortality as endpoint. Petrilli (2020) measured candidate factors during hospital stay and measured discharge to hospice or death among those admitted to hospital as endpoint. Multivariable models showing associations between predefined candidate prognostic factors and outcome were reported. One study (Chen, 2020) internally validated the risk factors by establishing a nomogram based on the results of the multivariate analysis. It was decided to include unvalidated studies in the literature review for this outcome as well, as risk of bias of Chen (2020) was moderate.

A brief overview of study characteristics of the included studies is reported in table 1. Extended information about risk of bias is included in the and risk of bias table. It should be noted that populations, measurement of factors and selection methods of factors were not well reported in many studies.

Table 1 Study characteristics of included studies

|

Study |

Population |

N |

Age Median (IQR) |

Inclusion period |

Follow-up |

Method |

Outcome |

|

Chen, 2020 |

Hospitalized COVID-19 patients, from 575 hospitals; China |

1590 |

Not reported |

Admission to hospital until January 31, 2020 (startpoint of admission to hospital not reported) |

Not reported |

Multivariate Cox regression; included prognostic factors were selected based on univariable analyses; nomogram developed based on backward stepdown selection |

Mortality |

|

Cummings, 2020 |

Hospitalized COVID-19 patients ≥18 y, critically ill with acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure, 2 hospitals, USA |

257 |

62 y (51-72) |

Admission to hospitals between March 2 to April 1, 2020; Candidate factors were measured during hospital stay (collected from medical records) |

April 28, 2020 |

Multivariate Cox regression; included prognostic factors were considered relevant to in-hospital mortality by the authors. |

In-hospital mortality |

|

Gao, 2020 |

Hospitalized COVID-19 patients, 1 hospital, China |

2877 |

Not reported for total group |

Admission to hospital between February 5 to March 15, 2020; Candidate factors were measured during hospital stay (collected from medical records) |

April 1, 2020 |

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards model; reason of selection of included prognostic factors in multivariable model not described. |

In-hospital mortality |

|

Giacomelli, 2020 |

Hospitalized COVID-19 patients ≥18 y, 1 hospital, Italy |

233 |

61 y (50-72) |

Admission to hospital between February 21 and March 19, 2020; Candidate factors were measured during hospital stay (collected from medical records) |

April 20, 2020 |

Multivariable Cox proportional hazard models; included prognostic factors were selected based on univariable analyses. |

Mortality |

|

Klang, 2020 |

Hospitalized COVID-19 patients ≥18 y, 5 hospitals, USA |

3406 |

Not reported for total group |

Admission to hospital between March 1 and May 17, 2020; Candidate factors were measured during hospital stay (collected from medical records) |

Not reported |

Multivariable logistic regression models; adjusted for age decile, male sex, CAD, CHF, HTN, DM, hyperlipidemia, CKD, history of cancer, smoking (past or present), BMI 30 – 40 kg/m2, BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 and race; included prognostic factors were selected based on univariable analyses; no validation reported |

In-hospital mortality |

|

Palaiodimos, 2020 |

Hospitalized COVID-19 patients, 1 hospital, USA |

200 |

64 y (50-73.5) |

Admission to hospital between March 9 to March 22, 2020; Candidate factors were measured during hospital stay (collected from medical records) |

3-weeks follow-up: April 12, 2020 |

Multivariate logistic regression model; 3 models used (model 1: BMI and age; model 2: all the variables with significant univariate associations; model 3: variables of model 2 in addition to clinically significant variables which did not show a significant univariate association); no validation reported |

In-hospital mortality |

|

Petrilli, 2020 |

Admitted and not admitted to hospital COVID-19 patients, >260 outpatients office sites and 4 acute care hospitals, USA |

5279 (2441 were admitted to the hospital) |

Tested population: 54 y (38-66) Admitted population: 63 y (51-74) |

Patients tested between March 1 and April 8, 2020; Candidate factors were measured during hospital stay (collected from medical records) |

May 5, 2020 |

Multivariable logistic regression models; predictors selected based on previous published literature and clinical experience of authors of patients with COVID-19. |

Inpatient hospital admission, discharge to hospice or death among those admitted to hospital |

|

Wang, 2020 |

Hospitalized COVID-19 patients >60 y, 1 hospital, China |

339 |

69 y (65-76) |

Admission to hospital between January 1 and February 6, 2020; Candidate factors were measured during hospital stay (collected from medical records) |

4 weeks from the last admission |

Multivariate Cox regressions; included prognostic factors were selected based on univariable analyses; no validation reported |

Mortality |

Results of graded studies

All studies reported models predicting mortality and Petrilli (2020) reported a model predicting hospital admission. Table 2 shows the reported model design.

Table 2 Reported prognostic models for mortality

|

Study |

Mortality n/N (%) |

Outcome(s) |

Included prognostic factors |

|

Chen, 2020 |

50/1590 (3.1%) |

Mortality |

Age; Coronary heart disease; Cerebrovascular disease; Dyspnea; Procalcitonin; Aspartate aminotransferase; Total bilirubin; Creatinine |

|

Cummings, 2020 |

101/257 (39.0%) |

Time to in-hospital mortality from hospital admission |

Age; Sex; Symptom duration before hospital presentation; Hypertension; Chronic cardiac disease; COPD; Diabetes; IL-6 concentrations; D-dimer concentrations |

|

Gao, 2020 |

56/2877 (1.9%) |

All-cause mortality during hospitalization |

Hypertension; Age; Sex, Diabetes; Myocardial infarction; Treatment by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG); Renal failure; Chronic heart failure; Asthma; COPD; Stroke |

|

Giacomelli, 2020 |

48/233 (20.6%) |

Mortality (censoring date April 20, 2020) |

Age; Sex; Obesity; being treated with ≥1 anti-hypertensive agent; Disease severity; Presence of anemia; Lymphocyte count; D-dimer; C-reactive protein; Creatinine; Creatinine kinase |

|

Klang, 2020 |

1136/3406 (33.4%) |

In-hospital mortality |

Age; Sex; Comorbidities (CAD, CHF, HTN, DM, hyperlipidemia, CKD, cancer); Obesity; Smoking status |

|

Paladaiomidos, 2020 |

48/200 (24%) |

In-hospital mortality |

Age; BMI; Heart failure; Coronary artery disease; Diabetes; Chronic kidney disease or end-stage renal disease; COPD; current or former smoker |

|

Petrilli, 2020 |

665/2741 (24.3%) |

1) Admission to hospital 2) Mortality (only admitted patients in analysis) |

Age; BMI; Sex; Week; Ethnicity; Smoking status; Coronary artery disease; Heart failure; Hypertension; Diabetes; Asthma or COPD; Chronic kidney disease; Cancer |

|

Wang, 2020 |

65/339 (19.2%) |

Mortality |

Age; Cardiovascular disease; Cerebrovascular disease; COPD |

Abbreviations: CAD, Coronary artery disease; CHF, Congestive heart failure; CKD, Chronic kidney disease; HTN, hypertension; DM, Diabetes mellitus; BMI, Body mass index.

Mortality predicted by prognostic factors measured during hospital stay

As reported models had different outcome measures and included factors were different, results could not be pooled. Because models were unvalidated, only results regarding factors that were included in at least two studies will be discussed. Table 3 shows relevance of reported associations for mortality.

Table 3 Relevance of prognostic factors for mortality

|

|

Statistically significant |

||||||||

|

|

Chen |

Cummings |

Gao |

Giacomelli |

Klang |

Klang |

Palaiodimos |

Petrilli |

Wang |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Age≤50 y |

Age>50 y |

|

|

|

|

Predictor |

HR (95% CI) |

HR (95% CI) |

HR (95% CI) |

HR (95% CI) |

OR (95% CI) |

OR (95% CI) |

OR (95% CI) |

HR (95% CI) |

HR 95% CI) |

|

Age |

Yes <65y: ref 65-74: 3.43 (1.24-9.5) ≥75: 7.86 (2.44-25.35) |

Yes Per 10y: 1.39 (1.29-1.57) |

Yes Per year: 1.06 (1.04-1.09)

|

Yes Per 10y: 2.08 (1.48-2.92) |

Yes Per 10y: 3.0 (1.9-4.8) |

Yes Decile: 1.7 (1.6-1.8) |

Yes Quartiles: 1.73 (1.13-2.63) |

Yes 19-44y: ref 45-54: 1.12 (0.80-1.60) 55-64: 2.04 (1.50-2.80) 65-74: 2.88 (2.46-4.80) ≥75: 3.46 (2.46-4.80)) |

Yes 1.86 (1.06-3.26) |

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

- |

No <40: ref ≥40: 0.76 (0.4-1.47)

|

- |

Yes <30: ref ≥30: 3.04 (1.42-6.49) |

Yes <30: ref 30-40: 1.1 (0.5-2.3) ≥40: 5.1 (2.3-11.1) |

Yes >30: ref 30-40: 1.1 (0.9-1.3) ≥40: 1.6 (1.2-2.3) |

Yes 25-34: ref <25: 1.37 (0.52-3.64) ≥35: 3.78 (1.45-9.83) |

Yes <25: ref 25-30: 0.91 (0.74-1.11) 30-40: 1.02 (0.82-1.27) ≥40: 1.41 (0.98-3.02) Unknown: 1.85 (1.13-3.02) |

- |

|

Smoking |

- |

- |

- |

- |

No 1.7 (0.8-3.8) |

No 1.0 (0.8-1.2) |

No 0.83 (0.37-1.87) |

Yes Never: ref Former: 1.13 (0.93-1.37) Current: 0.90 (0.61-1.31) Unknown: 1.56 (1.26-1.93) |

- |

|

Hypertension (yes/no) |

- |

No 1.58 (0.89-2.81) |

Yes 2.00 (1.13-3.54) |

- |

No 0.5 (0.2-1.1) |

No 1.1 (0.9-1.3) |

|

No 0.94 (0.76-1.16) |

- |

|

Diabetes (yes/no) |

- |

No 1.31 (0.81-2.10) |

- |

- |

No 1.3 (0.7-2.6) |

Yes 1.4 (1.2-1.7) |

No 1.16 (0.55-2.44) |

No 1.10 (0.93-1.31) |

- |

|

Coronary artery disease or congestive heart failure (yes/no) |

- |

Yes 1.76 (1.08-2.86) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Coronary artery disease (yes/no) |

Yes 4.28 (1.14-16.13) |

- |

- |

- |

No 0.6 (0.2-2.1) |

Yes 1.3 (1.1-1.6) |

No 1.53 (0.54-4.34) |

No 1.12 (0.92-1.36) |

- |

|

Cerebrovascular disease (yes/no) |

Yes 3.1 (1.07-8.94) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

No 1.38 (0.65-2.93) |

|

Heart failure (yes/no) |

- |

- |

Yes 3.3 (1.33-8.19) |

- |

Yes 4.0 (1.6-10.4) |

No 1.0 (0.8-1.3) |

No 1.43 (0.50-4.06) |

Yes 1.77 (1.43-2.20) |

- |

Hospital admission predicted by prognostic factors measured during hospital stay

Hospital admission was only reported in the study of Petrilli (2020). Because the model was unvalidated and was included in only one study, the results regarding prognostic factors for hospital admission will not be discussed.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence was assessed according to the GRADE methodology (GRADE: Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation, http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/).

Mortality predicted by prognostic factors

Body Mass Index (BMI)

Starting with a high level of evidence for prognostic studies, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality was downgraded by 1 level because of risk of bias (some patients were still under treatment at the end of the study) and by 1 level because of indirectness (studies are not validated) and 1 level for imprecision (wide confidence intervals, one included in the confidence interval) to ‘very low’.

Smoking

Starting with a high level of evidence for prognostic studies, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality was downgraded by 1 level because of risk of bias (some patients were still under treatment at the end of the study) and by 1 level because of indirectness (studies are not validated ) and 1 level for imprecision (wide confidence intervals, one included in the confidence interval) to ‘very low’.

Hypertension

Starting with a high level of evidence for prognostic studies, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality was downgraded by 1 level because of risk of bias (some patients were still under treatment at the end of the study) and by 1 level because of indirectness (studies are not validated) and 1 level for imprecision (wide confidence intervals, too many prognostic factors included in relation to number of events) to ‘very low’.

Diabetes

Starting with a high level of evidence for prognostic studies, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality was downgraded by 1 level because of risk of bias (some patients were still under treatment at the end of the study) and by 1 level because of indirectness (studies are not validated ) ) and 1 level for imprecision (wide confidence intervals and one included in the confidence interval) to ‘very low’.

Coronary artery disease or congestive heart failure

Starting with a high level of evidence for prognostic studies, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality was downgraded by 1 level because of risk of bias (some patients were still under treatment at the end of the study), by 1 level because of indirectness (studies are not validated ) and by 1 level because of inconsistency of results to ‘very low’.

Cerebrovascular disease

Starting with a high level of evidence for prognostic studies, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality was downgraded by 1 level because of risk of bias (some patients were still under treatment at the end of the study), by 1 levels because of indirectness (studies are not validated ), by 1 level because of inconsistency of results and by 1 level because of number of included patients (imprecision) to ‘very low’.

Heart failure

Starting with a high level of evidence for prognostic studies, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality was downgraded by 1 level because of risk of bias (some patients were still under treatment at the end of the study), by 1 levels because of indirectness (studies are not validated), by 1 level because of inconsistency of results and by 1 level because of number of included patients (imprecision) to ‘very low’.

Zoeken en selecteren

A review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

Which independent prognostic factors (cardiovascular risk factors or cardiovascular disease) strongly predict a poor outcome of COVID-19 infection, independent of other factors?

P: All proven COVID-19 patients

I: Presence of one of the following prognostic factors: cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking, obesity, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, diabetes (insulin resistance, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis), cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular history (arrhythmias, coronary artery disease, heart failure, valvular heart disease)

C: absence of the prognostic factors

O: mortality (crucial), IC-admission (crucial), hospital admission, length of stay, thromboembolic complications (pulmonary embolism, stroke, transient ischemic attack)

T: admission to hospital, admission to ICU, during hospital stay, at home

S: in-hospital, pre-hospital

Confounder: age

Relevant outcome measures

Mortality and IC-admission were considered as critical outcome measures for decision making and the other outcomes as important outcomes for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above, but used the definitions used in the studies.

A priori, the working group did not define minimal clinically relevant differences for the outcome measures.

Prognostic research: Study design and hierarchy

For this research question, it is aimed to investigate multiple cardiovascular factors that might predict disease severity and mortality in patients with COVID-19. To investigate whether factors are predictive, a longitudinal relation between candidate prognostic factors (measured at T0) and outcome (measured at T1) has to be investigated. Often, prognostic factors are correlated with other factors (Foroutan, 2020). To describe the effect of single prognostic factors, these should be measured in relation to its confounders. Mostly, important confounders can be predefined. Only models including all predefined confounders and measuring longitudinal associations between candidate predictors and outcome can be taken into account. When multiple factors are investigated, multivariable models predicting outcome are developed and will be used as a tool for clinical decision making.

When reviewing literature, there is a hierarchy in quality of individual studies. Preferably, models for clinical decision making show the efficacy of using multivariable models in healthcare. In this way, they are most helpful to decide which factors should be used in clinical practice. Differences in clinical decision making according to the developed model and the effect on patient related outcome should be measured after sufficient follow-up periods (Moons, 2008). If such studies are not available, studies validating the effects of developed prognostic multivariable models in other samples of the target population (external validation) are preferred as there is more confidence in the results of these studies compared to not externally validated studies. Most samples do not completely reflect the characteristics of the total population, resulting in deviated associations, possibly having consequences for conclusions. Studies validating prognostic multivariable models internally (e.g. bootstrapping or cross validation) or studies reporting unvalidated prognostic multivariable models can be used to answer the research question as well, but downgrading the level of evidence is obvious due to risk of bias and/or indirectness as it is not clear whether models perform sufficient in target populations. Due to the low confidence in the results of externally unvalidated models, specific results regarding factors of interest reported in such models will be described only if factors have been used in at least two multivariable models/studies. Univariable prognostic models (or multivariable prognostic models not taking confounders into account) cannot be graded as confidence in these models is too low.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 9-6-2020. The systematic literature search resulted in 567 hits. See search strategy for detail. No studies investigating the impact of a multivariable cardiovascular prognostic model on healthcare regarding mortality, IC-admission, hospital admission, length of stay and/or thromboembolic complications were found. Studies developing and/or validating a multivariable prognostic model were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies (cohort studies) assessing the longitudinal relation between cardiovascular risk factors (smoking, obesity, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, diabetes), cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular history (measured at hospital admission/during hospital stay), with mortality, IC-admission, hospital admission, length of stay, thromboembolic complications (measured at endpoint) in proven COVID-19 patients. Age was considered as confounder that had to be included in the multivariable models.

45 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 37 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 8 studies were included.

Some systematic reviews evaluated the association between cerebrovascular, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus or hypertension and poor outcome in patients with COVID-19, for example Huang (2020), Li (2020), Lippi (2020), Pranata (2020a), Pranata (2020b) and Zheng (2020). These systematic reviews were not included, because associations were calculated without taking any confounders into account.

Results

Eight studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias table.

Referenties

- Chen, R., Liang, W., Jiang, M., Guan, W., Zhan, C., Wang, T., ... & Hu, Y. (2020). Risk factors of fatal outcome in hospitalized subjects with coronavirus disease 2019 from a nationwide analysis in China. Chest.

- Cummings, M. J., Baldwin, M. R., Abrams, D., Jacobson, S. D., Meyer, B. J., Balough, E. M., ... & Hochman, B. R. (2020). Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet.

- Gao, C., Cai, Y., Zhang, K., Zhou, L., Zhang, Y., Zhang, X., ... & Zhao, Y. (2020). Association of hypertension and antihypertensive treatment with COVID-19 mortality: a retrospective observational study. European Heart Journal, 41(22), 2058-2066.

- Giacomelli, A., Ridolfo, A. L., Milazzo, L., Oreni, L., Bernacchia, D., Siano, M., ... & Piscaglia, M. (2020). 30-day mortality in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 during the first wave of the Italian epidemic: a prospective cohort study. Pharmacological Research, 104931.

- Klang, E., Kassim, G., Soffer, S., Freeman, R., Levin, M. A., & Reich, D. L. (2020). Morbid Obesity as an Independent Risk Factor for COVID‐19 Mortality in Hospitalized Patients Younger than 50. Obesity.

- Palaiodimos, L., Kokkinidis, D. G., Li, W., Karamanis, D., Ognibene, J., Arora, S., ... & Mantzoros, C. S. (2020). Severe obesity, increasing age and male sex are independently associated with worse in-hospital outcomes, and higher in-hospital mortality, in a cohort of patients with COVID-19 in the Bronx, New York. Metabolism, 108, 154262.

- Petrilli, C. M., Jones, S. A., Yang, J., Rajagopalan, H., O’Donnell, L., Chernyak, Y., ... & Horwitz, L. I. (2020). Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. bmj, 369.

- Wang, L., He, W., Yu, X., Hu, D., Bao, M., Liu, H., ... & Jiang, H. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 in elderly patients: Characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4-week follow-up. Journal of Infection.

Evidence tabellen

Table of quality assessment – Prognostic factor (PF) studies

Based on: QUIPSA (Haydn, 2006; Haydn 2013)

|

Study reference

(first author, year of publication) |

Study participation1

Study sample represents the population of interest on key characteristics?

(high/moderate/low risk of selection bias) |

Study Attrition2

Loss to follow-up not associated with key characteristics (i.e., the study data adequately represent the sample)?

(high/moderate/low risk of attrition bias) |

Prognostic factor measurement3

Was the PF of interest defined and adequately measured?

(high/moderate/low risk of measurement bias related to PF) |

Outcome measurement3

Was the outcome of interest defined and adequately measured?

(high/moderate/low risk of measurement bias related to outcome) |

Study confounding4

Important potential confounders are appropriately accounted for?

(high/moderate/low risk of bias due to confounding) |

Statistical Analysis and Reporting5

Statistical analysis appropriate for the design of the study?

(high/moderate/low risk of bias due to statistical analysis) |

Overall judgment

High risk of bias: at least one domain judged to be at high risk of bias.

Model development only: high risk of bias.

Risk of bias: low/moderate/high/unclear |

|

Chen, 2020 |

Unclear (inclusion criteria not clearly described) |

Moderate (21% excluded because of incomplete medical records: differences not described) |

Unclear (assessment not well described) |

High (endpoint for mortality not described: patients could be still under treatment at endpoint of the study) |

Low (accounted for age) |

Moderate (reason for selection of factors is unclear) |

Moderate |

|

Cummings, 2020 |

High (only COVID-19 patients included who were critically ill with acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure) |

Unclear (loss to follow-up not described) |

Low |

High (some patients were still under treatment at endpoint of the study) |

Low (accounted for age) |

Moderate (independent variables included in multivariable Cox model considered relevant to in-hospital mortality by the authors. |

High |

|

Gao, 2020 |

Low |

Unclear (loss to follow-up not described) |

Low |

High (patients could be still under treatment at endpoint of the study: not described) |

Low (accounted for age) |

Unclear (reason of selection of included prognostic factors in multivariable model not described) |

Moderate |

|

Giacomelli, 2020 |

Low |

Unclear (loss to follow-up not described) |

Low |

High (some patients, 10%, were still under treatment at endpoint of the study) |

Low (accounted for age) |

Low (significant factors univariate analysis included in multivariable analysis) |

Moderate |

|

Klang, 2020 |

Low |

High (patients who were still hospitalized during the study period and/or with missing BMI were excluded) |

Low |

High (22% were still hospitalized at endpoint of the study and were excluded) |

Low (accounted for age) |

Moderate (all factors included in the multivariate model) |

High |

|

Palaiodimos, 2020 |

Low |

Unclear (loss to follow-up not described) |

Low |

Low |

Low (accounted for age) |

Low (3 models developed, BMI and age, all the variables with significant univariate associations and addition of clinically significant variables) |

Low |

|

Petrilli, 2020 |

Low |

High (patients who were still hospitalized during the study period were censored) |

Low |

High (mortality after discharge was not measured unless patients was readmitted to the system) |

Low (accounted for age) |

Low (included all selected predictors based on a priori clinical significance after testing for collinearity using the variance inflation factor) |

High |

|

Wang, 2020 |

Low |

Unclear (loss to follow-up not described) |

Low |

High (54% was still hospitalized at endpoint of the study) |

Low (accounted for age) |

Low (significant factors univariate analysis included in multivariable analysis) |

High |

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Aggarwal 2020 |

Wrong comparison: mortality in patients with severe COVID-19 disease and pre-existing history of CVD. Only 3 studies |

|

Alqahtani 2020 |

Wrong comparison: prevalence of chronic diseases (COPD), no multilevel analysis |

|

Cecconi 2020 |

Wrong outcome: composite outcome (ICU transfer or death) |

|

Galloway 2020 |

Wrong outcome: composite outcome (transfer to a critical care unit bed or death) |

|

Guan 2020 |

Wrong outcome: Only composite endpoint used in multivariate analysis. Same cohort as Chen (2020). |

|

Hamer 2020 |

Wrong comparison: lifestyle risk factors |

|

Hu 2020 |

Wrong outcome: composite outcome |

|

Huang 2020 |

Wrong study design: associations between diabetes and composite outcome composite poor outcome, including mortality, severe COVID-19, ARDS, need for ICU care, and disease progression, no predictive value (no adjustments performed) |

|

Imam 2020 |

Wrong comparison: imaging findings, medication, laboratory values |

|

Jain 2020 |

Wrong study design: sample size <200 included |

|

Kumar 2020 |

Wrong outcome: composite outcome (severe clinical course) |

|

Li 2020a |

Wrong study design: associations between CVD, hypertension and myocardial injury and mortality, no predictive value (no adjustments performed) |

|

Li 2020b |

Wrong outcome: severe covid-19 |

|

Lippi 2020 |

Wrong study design: associations between hypertension and disease severity and mortality, no predictive value (no adjustments performed) |

|

Liu 2020 |

Wrong outcome: composite outcome (disease severity) |

|

Luo 2020 |

Article in Chinese |

|

Nikpouraghdam 2020 |

Wrong comparison: comorbidity as predicting factor (no separate diseases) |

|

Parohan 2020 |

Wrong study design: associations between comorbidities and mortality, no predictive value (no adjustments performed) |

|

Pranata 2020a |

Wrong study design: associations between CVD and mortality/poor composite outcome, no predictive value (no adjustments performed) |

|

Pranata 2020b |

Wrong study design: associations between hypertension and mortality, no predictive value (no adjustments performed) |

|

Roncon 2020 |

Not searched in Medline. Searched on Diabetes Mellitus |

|

Santoso 2020 |

Wrong outcome: prognostic effect troponin on outcomes |

|

Shi 2020 |

Small sample (N<200) |

|

Shi 2020a |

Wrong comparison: cardiac biomarkers (troponin, CK-MB, MYO) |

|

Shi 2020b |

Wrong comparison: cardiac injury biomarkers |

|

Tamara 2020 |

Wrong outcome: severe covid-19 |

|

Tian 2020 |

Wrong study design: no multilevel analysis |

|

Wang 2020a |

Wrong outcome: COVID-19 |

|

Wang 2020b |

Wrong comparison: predictive laboratory model compared to clinical model (age, hypertension, CHD) |

|

Zhang 2020a |

Wrong outcome: recovery of patients during follow-up |

|

Zhang 2020b |

Wrong comparison: mortality in hypertensive patients, no prognostic factor (no adjustments performed) |

|

Zhang 2020c |

Wrong outcome: COVID-19 severity |

|

Zhao 2020 |

Wrong outcome: severe covid-19 |

|

Zheng 2020 |

Wrong study design: associations between hypertension, CVD, diabetes and non-critical/critical or mortality, no predictive value (no adjustments performed) |

|

Zuin 2020 |

Commentary article |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld :

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.