Omvang van cardiale schade bij in het ziekenhuis opgenomen COVID-19 patiënten

Uitgangsvraag

How often and in what extent do admitted COVID-19 patients have signs of cardiac injury as defined according to the Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction? And if so, what is the outcome of the non-ischemic injury and ischemic (type 1 and 2) infarction patients?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg cardiale markers (troponine) te bepalen bij opname van een COVID-19 patiënt en indien afwijkend deze te vervolgen conform de ‘Aanbeveling voor vroege detectie cardiale schade bij COVID-19 infectie’ van de NVVC.

Verricht afhankelijk van het biochemische verloop aanvullende cardiale diagnostiek (anamnese, ECG en beeldvorming) tijdens opname of daarna.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

De kwaliteit van het bewijs van de geïncludeerde studies is overwegend laag tot zeer laag. De GRADE systematiek is gevolgd om de kwaliteit van het bewijs te beoordelen. Deze is hier dan ook gevolgd. In een nieuwe situatie (zoals COVID) is het logisch dat de meeste studies nog niet kunnen voldoen aan de strenge eisen die aan studies van hoge kwaliteit worden gesteld. De GRADE methodiek zet de kwaliteit van het bewijs echter af tegen de best mogelijke kwaliteit en niet tegen de best mogelijke kwaliteit in de huidige situatie. De GRADE systematiek geeft het vertrouwen weer in de schatting van het effect van een interventie. Wanneer de modules en de search worden geüpdate zijn er hopelijk studies van betere kwaliteit beschikbaar en kan het niveau van de kwaliteit van het bewijs hierop worden aangepast.

De aanwezigheid van myocardiale schade varieerde in de verschillende studies tussen 9,6% en 46,3%. Van alle geïncludeerde patiënten in de pooled risk ratio van cardiale schade in relatie tot mortaliteit had 40% myocardiale schade. In de pooled risk ratio in relatie tot IC opname had 25% myocardiale schade. Grofweg kan gesteld worden dat minimaal een kwart van de patiënten met COVID-19 die opgenomen moeten worden in het ziekenhuis myocardiale schade heeft. Patiënten met myocardiale schade hebben een hogere mortaliteit en moeten vaker op de IC worden opgenomen. Dit is een klinisch relevant effect voor een grote patiëntenpopulatie.

Slechts 2 van de geïncludeerde studies beschreven opname duur als uitkomstmaat, een studie vond een significant verschil tussen patiënten met en zonder myocardiale schade, de andere studie vond geen significant verschil. Op basis van deze resultaten kan hierover dan ook geen conclusie getrokken worden.

De bewijskracht uit de literatuur search is laag tot zeer laag. Dit komt o.a. door het retrospectieve design van de geïncludeerde studies en de mate van heterogeniteit. Echter laten wel alle geïncludeerde studies, evenals de pooled risk ratios, het positieve effect van myocardiale schade op mortaliteit en IC opname zien. Daarnaast is het belangrijk te realiseren dat het literatuuronderzoek is uitgevoerd met de op 6 juli 2020 beschikbare gegevens. Na deze datum zijn er onderzoeken gepubliceerd die helaas niet meer konden worden meegenomen in de analyse. Studies van latere datum met gegevens uit Azië en Europa ondersteunen ook de bevinding van het positieve effect van myocardiale schade op mortaliteit en IC opname, zoals onder andere blijkt uit studies van Cao (2020) en Stefanini (2020).

De conclusies van het literatuur onderzoek en ook recentere literatuur maken het daarom aannemelijk dat myocardiale schade een ongunstig effect heeft op het beloop van COVID-19 patiënten. Echter om dit met meer zekerheid te kunnen stellen is een grote prospectieve studie nodig.

Het meten van myocardiale schade door middel van laboratoriumdiagnostiek (cardiaal troponine) heeft geen nadelige effecten voor de patiënten aangezien dit meegenomen kan worden in het routinematige laboratoriumonderzoek dat gedurende een ziekenhuis opname plaats vindt.

De meeste data uit de literatuur search komt uit ziekenhuizen buiten Europa, meestal uit China, en vanuit regio’s die zwaar getroffen zijn door de pandemie. Dit zou effect gehad kunnen hebben op de mate van myocardiale schade. Het is dan ook de vraag of de resultaten uit de literatuur search ook volledig van toepassing zijn op de Nederlandse populatie. In de meeste geïncludeerde studies zijn de troponine waardes alleen bij opname bepaald. Hierdoor zijn mogelijk ook patiënten met een chronisch verhoogd troponine meegenomen. Onder andere bij patiënten met chronisch hartfalen, diabetes mellitus, pulmonale hypertensie en chronische nierziekten kan het troponine chronisch verhoogd zijn. Deze chronische comorbiditeiten zijn echter ook bekende risicofactoren voor een gecompliceerd beloop van COVID-19. Het is dan ook de vraag of in deze groep de hogere mortaliteit en IC opnames volledig kan worden toegeschreven aan nieuwe myocardiale schade door COVID-19 of dat de verhoogde troponine waardes het resultaat zijn deze chronische comorbiditeiten. Om onderscheid te kunnen maken tussen deze 2 patiëntgroepen is het van belang het troponine gedurende de opname te vervolgen om een rise and fall te kunnen detecteren.

Evenwel is het belangrijk om onderscheid te maken tussen ischemische (type 1 en type 2 myocardinfarct) en non-ischemische myocard schade (acute en chronische myocard schade tgv myocarditis, hartfalen en/of nierinsufficientie). Vanuit dat oogpunt is bij aanwezigheid van verhoogde troponine waardes het afnemen van een specifieke cardiale anamnese, het verrichten van ECG’s en cardiale beeldvorming belangrijk om tot een specifiekere diagnose te komen.

CAPACITY

CAPACITY is een internationale registratie van patiënten met COVID-19 op basis van het ISARIC WHO CRF, aangevuld met informatie over specifieke cardiovasculaire parameters (https://capacity-covid.eu/). CAPACITY is in het voorjaar van 2020 gestart en bevat gegevens van 13034 patiënten uit 13 landen, afkomstig van 79 registrerende centra. CAPACITY bevat omvangrijke informatie over patiënten met COVID, omdat ongeveer 40% van de in Nederland opgenomen COVID19 patiënten in de registratie is opgenomen (n = 5524).

De peer-reviewed publicatie van CAPACITY over het onderwerp van deze module is momenteel in voorbereiding. De resultaten van CAPACITY kunnen daarom kunnen nog niet worden meegenomen bij het literatuuronderzoek, maar bij de overwegingen worden wel de voorlopige resultaten van CAPACITY meegenomen. De peer-reviewed publicatie over het onderwerp van deze module wordt binnenkort verwacht en bij een update van de module zal de publicatie in het literatuuronderzoek worden meegenomen.

In het prospectief opgezette CAPACITY II multicenter cohort onderzoek zal nader onderzoek verricht worden naar het optreden van cardiovasculaire complicaties bij COVID-19 en wat de korte en lange termijn gevolgen zijn. Vierhonderd COVID-19 patiënten met minimaal 4x UNL gestegen positieve troponine en/of nieuwe pathologische ECG afwijkingen en/of verdenking op cardiale aandoening binnen 24 uur na opname worden geïncludeerd en volgens de ‘Aanbeveling voor vroege detectie cardiale schade bij COVI-19 infectie’ van de NVVC vervolgd. Naast deze 400 patiënten met aanwijsbare cardiale betrokkenheid, worden ook 100 COVID-19 patiënten gevolgd die geen cardiale betrokkenheid hebben. Dit cohort dient als een controle groep. De follow-up beloopt maximaal 10 jaar.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Patiënten met COVID-19 worden geadviseerd om, tijdens of na ziekenhuisopname, aanvullende cardiale diagnostiek zoals ECG en troponine bepaling te laten verrichten indien daar aanleiding toe is. Patiënten die opgenomen zijn geweest met COVID-19 dienen alert te zijn op klachten zoals symptomen van hartfalen die kunnen wijzen op cardiale restschade en die te bespreken met hun huisarts of medisch specialist.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De kosten van een troponine bepaling zijn zeer laag, € <10 (NZa, 2020). Daar tegenover staat dat het waardevolle informatie over de prognose van een patiënt kan geven, waardoor hoog risicopatiënten eerder opgespoord kunnen worden. De troponine waardes zouden gebruikt kunnen worden in risico stratificatie modellen voor triage van hoog risicopatiënten die bijvoorbeeld baat zouden kunnen hebben van vroege medicatie toediening. Dit zou op de langere termijn juist kosten kunnen besparen als dit tot kortere ziekenhuisopname zou leiden. Om hierin meer inzicht te verkrijgen is echter wel aanvullend onderzoek nodig.

Er is nog veel onduidelijkheid t.a.v. het onderliggende mechanisme van de myocardiale schade. Dit zou kunnen berusten op non-ischemische oorzaken zoals virale myocarditis dan wel ischemische schade o.b.v. zowel een type I als II myocardinfarct. Om bij deze patiënten de juiste therapie in te kunnen zetten is aanvullende diagnostiek in de vorm van specifieke cardiale anamnese, ECG’s en cardiale beeldvorming (echocardiografie, cardiale MRI en zo nodig coronair angiografie) nodig. Het standaard bepalen van troponine bij COVID-19 patiënten zal dan ook leiden tot een toename van aanvullende diagnostiek gedurende de opname. Dit geeft hogere kosten, echter als hierdoor eerder gestart kan worden met een geschikte interventie zoals een revascularisatie of het opstarten van hartfalen medicatie brengt dit uiteindelijk ook weer gezondheidswinst met zich mee.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Er is geen kwantitatief of kwalitatief onderzoek gedaan naar de aanvaardbaarheid en haalbaarheid van de interventie. Echter het bepalen van cardiaal troponine kan routinematig worden meegenomen in de laboratoriumdiagnostiek gedurende de opname en brengt zeer lage kosten met zich mee. Dit zou daarom ook geen belemmering moeten vormen. Een nadeel zou echter kunnen zijn dat aan een verhoogd troponine ook consequenties gebonden moeten worden en aanvullend een cardiale anamnese, ECG en cardiale beeldvorming nodig is om het onderliggend mechanisme (myocarditis dan wel myocardiale ischemie) in specifieke patiënten te achterhalen om tijdig met een geschikte interventie te starten. Dit brengt hogere zorgkosten met zich mee en zou gevolgen kunnen hebben voor de wachtlijsten voor de betreffende beeldvorming in een ziekenhuis.

Om meer inzicht te verkrijgen in de onderliggende mechanismes van myocardiale schade is aanvullend prospectief onderzoek nodig waarbij standaard cardiale anamnese, ECG’s en aanvullende cardiale beeldvorming wordt verricht bij COVID-19 patiënten met verhoogde troponine waarde. Dit kan helpen in de besluitvorming om aanvullende diagnostiek in te zetten bij patiënten met COVID-19 en myocardiale schade.

Vanuit patiënt oogpunt zijn er voor het bepalen van troponine geen bezwaren te verwachten. Indien aanvullende beeldvorming noodzakelijk is zijn hier natuurlijk wel de risico’s van het betreffende onderzoek aan verbonden en moet hiervoor informed consent aan de patiënt gevraagd worden. Er is geen bezwaar in het kader van gezondsheidsgelijkheid, de betreffende onderzoeken/interventies zijn voor iedereen beschikbaar.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Ondanks de lage bewijskracht van de literatuur search, laten alle geïncludeerde studies een slechtere uitkomst zien bij patiënten met COVID-19 en myocardiale schade. Mede gezien de lage kosten van een troponine bepaling en het feit dat dit gemakkelijk meegenomen kan worden in het routinematig laboratoriumonderzoek tijdens een ziekenhuisopname, adviseren wij om te overwegen bij iedere patiënt die wordt opgenomen met COVID-19 standaard troponine bepalingen te verrichten. Het is belangrijk om het troponine gedurende de opname op te volgen om een rise-and-fall te kunnen detecteren om onderscheid te kunnen maken met patiënten met een chronisch verhoogd troponine. Op deze manier kunnen hoog risicopatiënten tijdig worden opgespoord en kan triage plaats vinden van patiënten die mogelijk baat hebben bij vroegtijdig starten van therapie.

Het bepalen van troponine heeft tot gevolg dat bij een verhoogde waarde ook meer aanvullende cardiale diagnostiek noodzakelijk is. Dit brengt hogere zorgkosten en belasting voor de wachtlijsten met zich mee. Echter het vroegtijdig opsporen van hoog risicopatiënten en het onderliggende mechanisme van myocardiale schade maakte het mogelijk om eerder met een geschikte therapie te starten wat uiteindelijk ook weer gezondheidswinst op zou kunnen leveren.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

The paradigm that the presence of cardiovascular disease is a risk factor for severe COVID-19 and that COVID-19 can cause myocardial injury has recently been described. Questions remain whether and to what extent COVID-19 causes myocardial damage and whether myocardial injury is an important contributor of outcome with implications for management, like medication, imaging, long-term follow-up and perhaps situations were triaging patients is needed.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Mortality (crucial)

|

Low GRADE |

Cardiac injury, defined as cTn elevation greater than 99th percentile, in COVID-19 patients could be associated with a higher risk of mortality. Sources: Santoso, Lorente-Ros, Barman, Wei |

IC admission (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

We are unsure if cardiac injury, defined as cTn elevation greater then 99th percentile, in COVID-19 patients is associated with IC admission.

Sources: Santoso, Lorente-Ros, Barman, Wei |

Hospital duration (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

We are unsure if cardiac injury, defined as cTn elevation greater then 99th percentile, in COVID-19 patients is associated with the number of days of admission in the hospital.

Sources: Barman, Lorente-Ros |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

The aim of the review of Santoso (2020) was to explore the association between cardiac injury and mortality, the need for intensive care unit (ICU) care, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia

PubMed, SCOPUS, EuropePMC, ProQuest, and Cochrane Central Databases were searched. Search results were limited to 2020. All research articles in adult patients diagnosed with COVID-19 with information on cTnl, cardiac injury, and clinical grouping or outcome of the clinically validated definition of mortality, the need for ICU care, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), or severe COVID-19 were included. Articles other than original research (e.g., case report or series, review articles, letters to editor, editorials or commentaries), duplicate publication, and non-English articles were excluded. The search was finalized on March 29th 2020. A total of 13 studies were included. Four studies were not peer-reviewed. All studies were retrospective observational studies. Most of the included studies defined cardiac injury as cTnl above 99th percentile in which the troponine cut-off was different in the included studies. Some of the studies included in this review did not specify a definition for cardiac injury. Seven of the included studies reported on mortality and were included in a meta-analysis (Risk ratio M-H). Three studies were included in a meta-analysis considering the relation between cardiac injury and IC-admission (risk ration M-H).

Barman (2020) aimed to delineate the prognostic importance of presence of concomitant cardiac injury on admission in patients with COVID-19 in Turkey. In this multi-center retrospective observational study, data of consecutive patients who were treated for COVID19 between 20 March and 20 April 2020 were collected. Clinical characteristics, laboratory findings and outcomes data were obtained from electronic medical records. Acute cardiac injury was defined as high sensitivity cardiac troponin I serum levels above the 99th percentile upper reference limit, regardless of new abnormalities in ECG. In-hospital clinical outcome was compared between patients with and without cardiac injury. total of 607 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 were included in the study. Kuno (2020) aimed to investigate whether cardiovascular disease or cardiac injury increased the risk of mechanical ventilation or mortality using the electronic medical records of Mount Sinai Health System in New York City. Kuno retrospectively analyzed a cohort of 8438 COVID-19 patients seen between March 1 and April 22, 2020. Mount Sinai health system combines 7 hospitals with more than 3800 beds and more that 410 ambulatory practices across metropolitan New York. Among 8438 patients, 54.7% of patients (N = 4616) were admitted to these hospitals. Analysis was performed on April 30th, 2020, which included patients who remained in the hospitals. Cardiac injury was defined as troponin I elevation which was defined as 99th percentile upper reference limit.

Lorente-Ros (2020) studied the effect of myocardial injury assessment on risk stratification of COVID-19 patients. In this observational study, a matched cohort of 112 patients was developed. After matching, an adequate comparability was shown by a decrease of the standardized differences to less than 20% for all covariates. Mortality was compared between patients with and without cardiac injury. Cardiac injury was defined as cTnI levels greater than the 99th percentile of a healthy population.

Wei (2020) sought to characterize the prevalence and clinical implications of acute myocardial injury in a large cohort of patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19. Data of 103 consecutive patients with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection admitted to the Public Health Clinical Centre of Chengdu and West China Hospital, Sichuan University, was collected between 16 January and 10 March 2020. Acute myocardial injury was defined by an cTnT value greater than the institutional upper limit of normal (14pg/mL). Outcomes of interest included death, admission to an intensive care unit (ICU), need for mechanical ventilation, treatment with vasoactive agents and classification of disease severity.

Table 1. describes the characteristics of the included studies.

Table 1 Study characteristics of included studies. It should be noted that the cardiac troponins (cTn) assays used in these studies differ in analytical characteristics, including their assessment of the upper reference limits, thereby limiting the direct comparability between studies.

|

Study |

Study type |

N |

Country |

Cardiac injury definition |

Method |

Outcome |

|

Santoso, 2020 |

Systematic review |

2389 (13 studies) Mortality: N= 1550 (7 studies) IC admission N=524 (3 studies) |

Not reported except ‘Most of the studies are from China’ |

highly sensitive cardiac troponin I (cTnl) above 99th percentile upper reference limit

Moment of measurement: not reported |

Odds ration meta-analysis (Mantel-Haenszel) |

Mortality, IC admission |

|

Barman,2020 |

multi-center retrospective study |

607 |

Turkey |

high sensitivity cardiac troponin I serum levels above the 99th percentile upper reference limit, regardless of new abnormalities in ECG Moment of measurement: at hospital admission |

Chi-square test was used to assess differences in categorical variables between groups. Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare unpaired samples as needed. Cox regression model |

Mortality, IC admission, hospital duration |

|

Kuno, 2020 |

Retrospective study |

8438 5320 in which troponin was measured |

US |

Cardiac injury was defined as troponin I elevation which was defined as 99th percentile upper reference limitMoment of measurement: not reported |

RR, stratification for age groups |

Mortality |

|

Lorente-Ros, 2020 |

Matched retrospective cohort. After matching, an adequate comparability was shown by a decrease of the standardized differences to less than 20% for all covariates |

707 |

Spain |

cTnI levels greater than the 99th percentile upper reference limit

Moment of measurement: at hospital admission |

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models |

Mortality, IC admission, hospital duration |

|

Wei, 2020 |

Prospective assessment of medical records |

101 |

China |

Acute myocardial injury was defined by an cTnT value greater than the institutional upper limit of normal (14pg/mL)

Moment of measurement: at hospital admission |

Student t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test to compare death for elevated cTn levels, Chi-square |

Mortality, IC admission |

Results

The included studies solely reported mortality (Santoso, Barman, Kuno, Lorente-Ros, Wei), IC-admission (Santoso, Barman, Lorente-Ros, Wei) and hospital duration (Barman, Lorente-Ros). Ventilation was also an outcome in some studies (Kuno, Lorente-Ros, Wei) but was not defined as days on ventilation but if ventilation was necessary. Therefore, this literature overview only reports on mortality, IC-admission and hospital duration.

1. Mortality

The systematic review of Santoso (2020) described 7 studies (of which 4 not peer reviewed) in which the outcome mortality was studied. The meta-analysis of Santoso calculated a pooled risk ratio of 7.95 (95% CI 5.12-12.34). The heterogeneity (I2) was 65%, meaning this may represent substantial heterogeneity. Barman (2020), Kuno (2020), Lorente-Ros (2020) and Wei (2020) also studied the outcome mortality in relation to cardiac injury. Barman (2020) and Lorente-Ros (2020) performed a univariate and multivariate regression analysis. In the study of Barman (2020) the univariate analysis (30 days) resulted in odds ratio (OR) of 7.97 (95% CI 5.03-12.64; P<0.001). The multivariable regression model (30 day) resulted in OR 10.58 (95% CI 2.42-46.27; P<0.001). In the multivariate model age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, CAD, smoking, COPD, creatinine, glucose, CRP and D-dimer ≥500 were taken into account in addition to cardiac injury. In the study of Lorente-Ros (2020) in the matched cohort all-cause mortality within 30 days was higher in those with cTnI elevation (41.1% vs. 23.2%; p = 0.005). The univariable regression model (30 days) resulted in Hazard Ratio (HR) of 4.355 (95% CI 3.112–6.093; P<0.001). The Multivariable regression model (30 days) resulted in HR 1.716 (95% CI 1.182–2.492; P=0.005). In the multivariable model sex, age, hypertension, RAAS inhibitors use, hematocrit, creatinine, D-Dimer, C-reactive protein and CCI were taken into account in addition to cardiac injury.

The study of Kuno (2020) resulted in an RR of 5.07 (95% CI 4.45-5.76) for mortality and the study of Wei (2020) calculated the difference between patients with and without cardiac injury that died. Patients with acute myocardial injury were older, with a higher prevalence of pre-existing cardiovascular disease and more likely to require ICU admission (62.5% vs 24.7%, p=0.003), mechanical ventilation (43.5% vs 4.7%, p<0.001) and treatment with vasoactive agents (31.2% vs 0%, p<0.001). Log cTnT was associated with disease severity (OR 6.63, 95% CI 2.24 to 19.65), and all of the three deaths occurred in patients with acute myocardial injury.

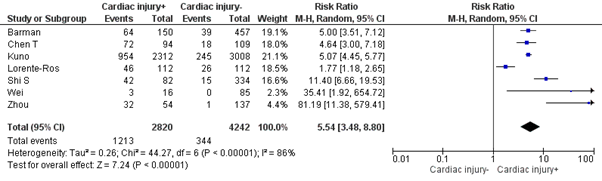

A pooled risk ratio was calculated in which only the peer reviewed studies from the systematic review of Santoso (2020) and the results of Barman (2020), Kuno (2020), Lorente-Ros (2020) and Wei (2020) were included (figure 1.1). The pooled risk ratio of COVID-19 patients with cardiac injury in relation to mortality was 5.54 (95% CI 3.48 – 8.80). This means that COVID-19 patients with cardiac injury had a 5 times higher chance on mortality in comparison to a COVID-19 patient without cardiac injury. The I2 was 86%, indicating that these studies might represented substantial heterogeneity.

Figure 1 Pooled risk ratio of cardiac injury in relation to mortality

2. IC admission (important outcome)

In the systematic review of Santoso (2020) three studies assessed the outcome IC admission and were included in a meta-analysis. Of the individual studies Barman (2020), Lorente-Ros (2020) and Wei (2020) assessed IC admission.

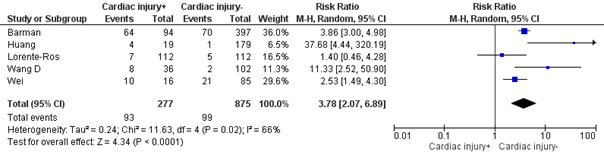

For IC admission the systematic review of Santoso shows a Pooled Risk Ratio (RR) of 7.94 (95% CI 1.51-41.78), meaning that cardiac injury was associated with a higher need for IC admission in COVID-19 patients. The studies of Barman, Lorente-Ros and Wei compared the number of IC admission for COVID-19 patients with and without cardiac injury. The studies of Barman (72% vs 19%; P<0.001) and Wei (62.5% vs 24.7%; P=0.003) showed a significant difference between both groups. Lorente-Ros concluded that there was no significant difference between both groups (6.3% and 4.3%; P=0.527). However, the number of patients requiring IC admission in this study were very small (7 and 5) what might have influenced the effect.

A pooled RR was calculated including only the peer reviewed studies from the systematic review of Santoso (2020) and the individual studies that assessed IC admission (figure 1.2). The pooled RR of COVID-19 patients with cardiac injury in relation to IC admission was 3.78 (95% CI 2.07-6.89). This means that COVID-19 patients with cardiac injury had a 3.8 times higher change of IC admission. The I2 was 66%, indicating that these studies might represented substantial heterogeneity.

Figure 2 Pooled risk ratio of cardiac injury in relation to IC admission

3. Hospital duration (important outcome)

Barman (2020) reported a significant difference between patient with cardiac injury and without cardiac injury for hospital duration (Cardiac injury: 12 (5–14) days, no cardiac injury–: 9 (4–12) days; P<0.001). Lorente-Ros (2020) reported no significant difference between patient with cardiac injury and without cardiac injury for hospital duration (Cardiac injury: 11 (6 to 17) days, no cardiac injury: 9 (5 to 13) days; P=0.934).

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence was assessed according to the GRADE methodology (GRADE: Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation, http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/).

Mortality (crucial outcome)

Starting with a high level of evidence for prognostic studies, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality was downgraded by 2 levels because of risk of bias (retrospective design, correction for confounders often not applied) to ‘low’.

IC admission (important outcome)

Starting with high level of evidence for observational studies in a prognostic studies, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure IC admission was downgraded by 2 levels because of risk of bias (retrospective design, correction for confounders often not applied), by 1 level for indirectness (none of the studies are performed in the Netherlands and each country can have different criteria for IC admission and IC admission may depend on IC capacity) by 1 level because of imprecision (wide confidence interval in study Santoso, few events in study of Lorente-Ros) to ‘very low’.

Hospital duration (important outcome)

Starting with high level of evidence for prognostic studies, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure hospital duration was downgraded with 1 level for inconsistency (both studies assessing hospital duration come to a different conclusion), 1 level for indirectness (the studies are performed in other European countries and each country may have their own criteria for hospital discharge), and 1 level for imprecision (only two studies included, low number of patients and follow up duration and number of patients lost to follow up unclear) to ‘very low’.

Zoeken en selecteren

A review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the occurrence, extent and outcome of cardiac injury and myocardial infarction in admitted patients with COVID-19?

P: Admitted COVID-19 patients

I: Presence of evidence of elevated cardiac troponin values (cTn) – either cTnT or cTnI – with at least 1 valueabove the 99th percentile upper reference limit (URL).

C: Admitted COVID-19 patients without cardiac injury

O: Mortality, revascularization, IC-admission, days on ventilation, hospital duration, intervention (PCI, CABG, ICD implantation, Left and/or Right Ventricle Assist Device support), VA-ECLS, VV-ECLS.

Relevant outcome measures

Mortality and revascularization were considered as crucial outcome measures and IC-admission, days on ventilation, hospital duration, intervention (PCI, CABG, ICD implantation, Left and/or Right Ventricle Assist Device support), VA-ECLS, VV-ECLS important outcomes.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until July 6th 2020. The systematic literature search resulted in 484 hits. See search strategy for detail.

120 Studies were initially included based on title and abstract screening. After a second assessment in which the titles and abstracts of the 120 studies were assessed for inclusion based on the PICO, 26 studies were selected. Studies that described the underlying mechanism, described the wrong outcome, did not define the intervention in the right way, did not contain original data or were literature reviews but not systematic reviews were excluded. After reading the full text six papers were included (1 systematic review, 5 single studies). Since the search of the systematic review was performed on March 29, all studies published before that date were excluded (1 study). In total 5 papers (1 systematic review, 4 single studies) were included.

Results

Five studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias table.

Referenties

- Barman, H. A., Atici, A., Sahin, I., Alici, G., Tekin, E. A., Baycan, Ö. F., ... & Celik, F. B. (2020). Prognostic significance of cardiac injury in COVID-19 patients with and without coronary artery disease. Coronary artery disease.

- Cao J, Zheng Y, Luo Z, et al. Myocardial injury and COVID-19: Serum hs-cTnI level in risk

stratification and the prediction of 30-day fatality in COVID-19 patients with no prior

cardiovascular disease. Theranostics 2020; 10: 9663-9673. - Kuno, T., Takahashi, M., Obata, R., & Maeda, T. (2020). Cardiovascular comorbidities, cardiac injury and prognosis of COVID-19 in New York City. American Heart Journal.

- Lorente-Ros, A., Ruiz, J. M. M., Rincón, L. M., Pérez, R. O., Rivas, S., Martínez-Moya, R., ... & Zamorano, J. L. (2020). Myocardial injury determination improves risk stratification and predicts mortality in COVID-19 patients. Cardiology Journal.

- Santoso, A., Pranata, R., Wibowo, A., Al-Farabi, M. J., Huang, I., & Antariksa, B. (2020). Cardiac injury is associated with mortality and critically ill pneumonia in COVID-19: a meta-analysis. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine.

- Stefanini GG, Chiarito M, Ferrante G, et al. Early detection of elevated cardiac biomarkers to

optimise risk stratification in patients with COVID-19. Heart 2020; 106: 1512-1518. - Wei, J. F., Huang, F. Y., Xiong, T. Y., Liu, Q., Chen, H., Wang, H., ... & Peng, Y. (2020). Acute myocardial injury is common in patients with covid-19 and impairs their prognosis. Heart.

- NVVC. Aanbeveling voor vroege detectie cardiale schade bij COVID-19 infectie. https://netwerk.nvvc.nl/manual/covid-19 , https://www.nvvc.nl/PDF/Bestuur/Vroege%20detetectie%20cardiale%20schade%20bij%20COVID19%20infecties.pdf of kwaliteit@nvvc.nl.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table systematic reviews

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Prognostic factor (cardiac injury definition) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Santoso, 2020 |

SR and meta-analysis of cohort studies

Literature search up to 29 March 2020

A: Chen T, 2020 (mortality) B: Li K, 2020 (mortality) [not peer reviewed] C: Luo XM, 2020 (mortality) [not peer reviewed] D: Shi S, 2020 (mortality) E: Wu C, 2020 (mortality, IC admission) [not peer reviewed] F: Zhang F, 2020 (mortality) [not peer reviewed] G: Zhou 2020 (mortality) H:Wang D, 2020 (IC admission) I: Huang, 2020 (IC admission) J: Hu L, 2020 K: Hu B, 2020 L: Zhao W, 2020 M: Zhang Guqin, 2020

Study design: all studies are observational retrospective studies

Setting and Country: Not available per study, most of the studies are from China

Source of funding: Not reported

|

Inclusion criteria SR: all research articles in adult patients diagnosed with COVID-19 with information on cTnl, cardiac injury, and clinical grouping or outcome of the clinically validated definition of mortality, the need for ICU care, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), or severe COVID-19

Exclusion criteria SR: articles other than original research (e.g., case report or series, review articles, letters to editor, editorials or commentaries), duplicate publication, and non-English articles.

13 studies included (7 report on mortality and 3 on IC admission)

Important patient characteristics at baseline: N, mean age deceased vs mean age survivors A: N=799, analysis based on N=274, 68y(†) vs 51y B: N=32, 69y(†) vs 51y C: N=403, 71y(†) vs 59y D: N=416, N/A E: N=188, N/A F: N=48, 78.65y(†) vs 66.16y G: N=191, 69y(†) vs 52y H: N=138, 66y (†) vs 51y I: N=41, 49y(†) vs 49y J: N=323, 65y(†) vs 56y K: N=36, 66.5y(†) vs 56y L: N=78, 69y(†) vs 45y M: N=221, 62(†) vs 51y

Sex (% male, deceased vs survivors): A: 73%(†) vs 55% B: 73%(†) vs 22% C: 57%(†) vs 44.9% D: N/A E: N/A F: 70.6%(†) vs 67.7% G: 70%(†) vs 59% H: 61.1%(†) vs 52% I: 85%(†) vs 68% J: 52.9%(†) vs 49.7% K: 68.8%(†) vs 65% L: 55%(†) vs 40.4% M: 63.6%(†) vs 44%

Groups comparable at baseline

|

A: cTnl above 99th percentile B: Unspecified C: Unspecified D:cTnl above 99th percentile E: Unspecified F: cTnl above 99th percentile G:cTnl above 99th percentile H: cTnl above 99th percentile I: cTnl above 99th percentile J: Unspecified K: Unspecified L: Unspecified M: cTnl above 99th percentile

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: Max 46 days (patients admitted from 13 January 020 to 28 February 2020) B: Max 34 days (Patients admitted from January 31 to March 5, 2020) C: Max 26 days (patients admitted from Jan 30 to Feb 25, 2020) D: Max 26 days (patients admitted from January 20, 2020, to February 10th, final date of follow up February 15, 2020) E: Max 48 days (patients admitted from December 25, 2019 to January 27, 2020 follow-up complete on February 11) F: Max 52 days (patients admitted from 25th December, 2019 to 15th February, 2020 ) G: Max 33 days (patients admitted between Dec 29 and Jan 31, 2020) H: Max 33 days (patients admitted from January 1 to January 28, 2020, follow up until February 3rd) I: N/A (patients admitted from Dec 16, 2019, to Jan 2, 2020) J: average observation period 28 days (20-47 days) (patients enrolled from January 8 to February 20, 2020, follow up until 10 March 2020) K: N/A (patients admitted from January 8 to February 9, 2020) L: Max 39 days (patients admitted from 21st January to 8th February 2020, follow up until February 29) M: Max 44 days (patients admitted from January 2 2020 to February 10 2020, follow up until February 15 2020)

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? A: 525 B: 5 C: 0 D: N/A E: 0 F: 2 G: 0 H: 0 I: 0 J: 0 K: 14 L: 41 M: 168 |

Outcome measure Mortality Effect measure: RR [95% CI] A: 4.64 [3.00, 7.18] B: 6.69 [2.61, 17.17] [not peer reviewed] C: 10.94 [6.83, 17.52] [not peer reviewed] D: 11.40 [ 6.66, 19.53] E: 5.25 [2.90, 9.50] [not peer reviewed] F: 6.08 [1.93, 19.13] [not peer reviewed] G: 81.19 [11.38, 579.41]

Pooled risk ratio 7.95 [5.12 – 12.34] Heterogeneity (I2): 65%

Outcome measure IC admission

Effect measure: RR [95% CI] E: 2.39 [1.50, 3.80] [not peer reviewed] H: 11.33 [2.52, 50.90] I: 37.68 [4.44, 320.19]

Pooled risk ratio 7.94 [1.51 – 41.78] Heterogeneity (I2): 79%

|

Facultative:

Most of the included studies are from China, are pre-prints and have a small number of included participants. Patients are included in the early days of the COVID pandemic (most of them enrolled in January and February 2020). Patients that deceased are older and more frequently male then the survivors. The effect is measured in RR, so a correction for this confounding factors was not performed.

A sensitivity analysis by leave-one-out was performed to single out heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis showed that heterogeneity for mortality outcomes could be reduced by removal of G: Zhou 2014 et al. study (RR 7.22 [4.97, 10.47], p < 0.001: I2: 54%, p = 0.05).

The removal of E: Wu et al. reduced heterogeneity for the need for ICU care (RR 16.85 [4.93, 57.62], p < 0.001; I2: 0%, p = 0.36)

|

Evidence table individual studies

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Prognostic factor(s) |

Follow-up

|

Outcome |

Comments |

|

Barman, 2020 |

Type of study: multi-center retrospective study

Setting: COVID-19 patients who were hospitalized in three government hospitals Country: Turkey

Source of funding: N/A |

Inclusion criteria: consecutive COVID-19 patients who were hospitalized in three government hospitals in Istanbul, Turkey between 20 March 2020 and 20 April 2020

Exclusion criteria: Patients < 18 y, with concurrent ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, with history of advanced kidney failure [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <30 ml/min] or hemodialysis and patients with missing laboratory parameters on admission including cTnI, and creatine kinase myocardial band (CK-MB)

N= 607 Cardiac injury N= 150 No Cardiac injury N = 457

Mean age ± SD: Cardiac injury: 66.0y ± 14.5 No Cardiac injury: 55.3y ± 15.2

Sex(%male): Cardiac injury: 54% No Cardiac injury: 52% |

high sensitivity cardiac troponin I serum levels above the 99th percentile upper reference limit, regardless of new abnormalities in ECG

Moment of measurement: at hospital admission |

patients were hospitalized between 20 March 2020 and 20 April 2020, follow up until 20 April 2020

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%): N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? No |

Mortality Cardiac injury = 64 (42%) No Cardiac injury– = 39 (8%) P<0.001

Univariable regression model (30 days) OR 7.97 [5.03–12.64] P <0.001

Multivariable regression model (30 days) OR 10.58 [2.42–46.27] P<0.001 Cardiac injury was found to be a predictor of mortality.

Sugbroup analysis When patients with previous CAD were excluded from analyses, presence of cardiac injury was still an independent predictor of mortaliy (OR 2.52, 95% CI 1.17–5.45; P = 0.018)

IC admission Cardiac injury N= 108 (72%) No Cardiac injury N= 87 (19%) P<0.001 Patients with cardiac injury were more frequently admitted to the IC then patients without cardiac injury.

Hospital duration (days) Cardiac injury: 12 (5–14) days No Cardiac injury: 9 (4–12) days P<0.001 Patients with cardiac injury spent more days in the hospital then patients without cardiac injury. |

Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test, Cox regression model |

|

Kuno, 2020 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort

Setting:7 hospitals with more than 3800 beds and more that 410 ambulatory practices across metropolitan New York

Country: US

Source of funding: No extramural funding |

Inclusion criteria: N/A

Exclusion criteria: N/A

N= 8438, 5320 used for analysis (troponin measured)

Median age ± SD: 59 [43, 71]

Sex: 53.9% male

|

Cardiac injury was defined as troponin I elevation which was defined as 99th percentile upper reference limit

Moment of measurement: not reported |

Endpoint of follow-up: Patients admitted from March 1 to April 22, 2020, follow up until April 30th

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%): N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? No |

Mortality Cardiac injury: 41.3% (954/2312) No Cardiac injury : 8.1% (245/3008)

RR 5.07 (4.45-5.76)

Patients with cardiac injury have an increased risk of mortality |

RR |

|

Lorente-Ros, 2020 |

Type of study: Matched retrospective cohort

Setting: a large tertiary hospital

Country: Spain

Source of funding: N/A |

Inclusion criteria: patients aged 18 years and older admitted to a large tertiary hospital with COVID-19 infection were retrospectively included with prospective follow-up.

Exclusion criteria: primary cardiac presentation, i.e. type 1 myocardial infarction

N=707 Cardiac injury n = 112 No Cardiac injury- n=112

Mean age ± SD: 66.76 ± 15.7 years

Sex: 63% male |

cTnI levels greater than the 99th percentile of a healthy population

Moment of measurement: at hospital admission |

Endpoint of follow-up: Patients admitted from March 18 to March 23, 2020 All patients were followed for 1 month

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? For the total group the outcome data of 66 (out of 707) remained hospitalized after 1 month. For the matched cohort the information is not available.

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

Mortality Cardiac injury N= 46 (41.1%) No Cardiac injury N= 26 (23.2%) P=0.005 All-cause mortality within 30 days was higher in those with cTnI elevation

Univariable regression model (30 days) Hazard Ratio 4.355 (3.112–6.093) P< 0.001

Multivariable regression model (30 days) Hazard Ratio 1.716 (1.182–2.492)

IC admission Cardiac injury N=7 (6.3%) No Cardiac injury N= 5 (4.5%) P= 0.527 There is no difference in patient with and without cardiac injury regarding IC-admission

Hospital duration (median days) Cardiac injury: 11 (6 to 17) days No Cardiac injury: 9 (5 to 13) days P= 0.934 There is no difference in patients with and without cardiac injury regarding hospital duration. |

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models, comparing means |

|

Wei, 2020 |

Type of study: Propspective assessment of medical records

Setting: laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV- 2 infection admitted to the Public Health Clinical Centre of Chengdu and West China Hospital, Sichuan University

Country: China

Source of funding: none declared |

Inclusion criteria: N/A

Exclusion criteria: N/A

N=101 cTnT≤14pg/mL n=85 cTnT>14pg/mL n=16

Mean age ± SD: Total 49 (34–62)y cTnT≤14pg/mL: 47 (33–55)y cTnT>14pg/mL : 67 (61.0–80.5)y

Sex: % M Total: 53.5% male cTnT≤14pg/mL: 55.3% male cTnT>14pg/mL : 43.8% male |

Acute myocardial injury was defined by an cTnT value greater than the institutional upper limit of normal (14pg/mL)

Moment of measurement: at hospital admission |

Endpoint of follow-up: Patients admitted between between 16 January and 10 March 2020

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

Mortality cTnT≤14pg/mL 0 death (0%) cTnT>14pg/mL 3 death (18.8%) P<0.001

IC admission cTnT≤14pg/mL 21 IC admissions (24.7%) cTnT>14pg/mL 10 IC admissions (62.5%) P=0.003 |

Multivariate analysis |

Table of quality assessment – prognostic factor (PF) studies

Based on: QUIPSA (Haydn, 2006; Haydn 2013)

|

Study reference

(first author, year of publication) |

Study participation1

Study sample represents the population of interest on key characteristics?

(high/moderate/low risk of selection bias) |

Study Attrition2

Loss to follow-up not associated with key characteristics (i.e., the study data adequately represent the sample)? (high/moderate/low risk of attrition bias) |

Prognostic factor measurement3

Was the PF of interest defined and adequately measured?

(high/moderate/low risk of measurement bias related to PF) |

Outcome measurement3

Was the outcome of interest defined and adequately measured? (high/moderate/low risk of measurement bias related to outcome) |

Study confounding4

Important potential confounders are appropriately accounted for?

(high/moderate/low risk of bias due to confounding) |

Statistical Analysis and Reporting5

Statistical analysis appropriate for the design of the study?

(high/moderate/low risk of bias due to statistical analysis) |

|

Santoso, 2020 |

Low risk |

Moderate (information on number of patients still in the hospital when follow up ended unavailable) |

Low, definition matches PICO |

Low Ic admission: moderate |

High (correction for confounders not applied) |

Low |

|

Barman, 2020 |

Low (in- and exclusion criteria defined) |

Moderate (information on number of patients still in the hospital when follow up ended unavailable) |

Low, definition matches PICO |

Low Ic admission : moderate |

Low, correction for confounders was performed |

Low |

|

Kuno, 2020 |

Low |

Moderate (information on number of patients still in the hospital when follow up ended unavailable) |

Low, definition matches PICO |

Low |

High (correction for confounders not applied) |

Low |

|

Lorente-Ros 2020 |

Moderate (matched cohort was develop but selection not transparent) |

Moderate (unclear if patients that have not died or been discharged from the hospital are included in the matched cohort) |

Low, definition matches PICO |

Low Ic admission : moderate |

Low, correction for confounders was performed |

low |

|

Wei, 2020 |

Low |

Moderate (information on number of patients still in the hospital when follow up ended unavailable) |

Low, definition matches PICO |

Low |

High (correction for confounders not applied) |

Moderate (for the outcome mortality the number of patients is so low that a comparison between both groups may not be appropriate) |

A https://methods.cochrane.org/sites/methods.cochrane.org.prognosis/files/public/uploads/QUIPS%20tool.pdf

1 Adequate description of: source population or population of interest, sampling and recruitment, period and place of recruitment, in- and exclusion criteria, study participation, baseline characteristics.

2 Adequate response rate, information on drop-outs and loss to follow-up, no differences between participants who completed the study and those lost to follow-up.

3 Method of measurement is valid, reliable, setting of measurement is the same for all participants.

4 Important confounders are listed (including treatments), method of measurement is valid, reliable, setting of measurement is the same for all participants, important confounders are accounted for in the design (matching, stratification, initial assembly of comparable groups), or analysis (appropriate adjustment)

5 Enough data are presented to assess adequacy of the analysis, strategy of model building is appropriate and based on conceptual framework, no selective reporting.

Table of quality assessment – prognostic factor (PF) studies (studies included in review Santoso)

Based on: QUIPSA (Haydn, 2006; Haydn 2013)Research question:

|

Study reference

(first author, year of publication) |

Study participation1

Study sample represents the population of interest on key characteristics?

(high/moderate/low risk of selection bias) |

Study Attrition2

Loss to follow-up not associated with key characteristics (i.e., the study data adequately represent the sample)?

(high/moderate/low risk of attrition bias) |

Prognostic factor measurement3

Was the PF of interest defined and adequately measured?

(high/moderate/low risk of measurement bias related to PF) |

Outcome measurement3

Was the outcome of interest defined and adequately measured?

(high/moderate/low risk of measurement bias related to outcome) |

Study confounding4

Important potential confounders are appropriately accounted for?

(high/moderate/low risk of bias due to confounding) |

Statistical Analysis and Reporting5

Statistical analysis appropriate for the design of the study?

(high/moderate/low risk of bias due to statistical analysis) |

Peer reviewed |

|

A: Chen T, 2020 |

Low (all patients diagnosed with Covid-19) |

Low (for the analysis only the data of patients that died or were discharged from the hospital were included) |

Moderate risk (cTnl>15.6 pg/mL) |

low |

x |

low |

Yes |

|

B: Li K, 2020 (mortality) |

Low (all patients diagnosed with Covid-19) |

Moderate (5 patients were still hospitalized at the moment of analysis) |

Low risk (cTnl 34.2pg/mL) |

low |

x |

low |

No |

|

C: Luo XM, 2020 (mortality) |

Low (all patients diagnosed with Covid-19) |

Low (for the analysis data of patients that died or were discharged from the hospital were included) |

Low risk (-cTnl>40 pg/mL) |

low |

x |

low |

No Santoso also included incorrect results from this study. Should be:

Mortality cardiac injury+ 47/96 (49.0%) recovered: CI+ 18/208 |

|

D: Shi S, 2020 (mortality) |

Low (all patients diagnosed with Covid-19) |

Moderate (319 patients remained in the hospital at the time of analysis) |

Low risk (Cardiac injury was defined as blood levels of cardiac biomarkers (cTNI) above the 99thpercentile upper reference limit, regardless of new abnormalities in electrocardiography and echocardiography) |

low |

x |

low |

Yes |

|

E: Wu C, 2020 (mortality, IC admission) |

Low (all patients diagnosed with Covid-19) |

Low (all patients died or were discharged at the moment of analysis) |

High risk (cTnl≥ 6.126 pg/mL) |

low |

x |

low |

No

|

|

F: Zhang F, 2020 (mortality) |

low (patients were diagnosed or suspected of Covid-19) |

Low (all patients died or were discharged at the moment of analysis) |

Low risk (cTnI) were above the 99th percentile upper reference limit (0.026ug/L) |

low |

x |

low |

No |

|

G: Zhou 2020(mortality) |

Low (all patients diagnosed with Covid-19) |

Low (all patients died or were discharged at the moment of analysis) |

Low (Acute cardiac injury was diagnosed if serum levels of cardiac biomarkers (eg, highsensitivity cardiac troponin I) were above the 99th percentile upper reference limit, (≥28 pg/mL) or if new abnormalities were shown in electrocardiography and echocardiography) |

Low |

X |

low |

Yes |

|

H:Wang D, 2020 (IC admission) |

Low (all patients diagnosed with Covid-19) |

Moderate (some patients remained hospitalized at the moment of analysis, number is unknown) |

Low (cTn were above the 99th percentile upper reference limit ≥26.2 pg/mL or new abnormalities were shown in electrocardiography and echocardiography) |

low |

X |

low |

Yes |

|

I: Huang, 2020 (IC admission) |

Low (all patients diagnosed with Covid-19) |

Moderate (7 patients still hospitalized at the time of analysis) |

Low (cardiac injury was diagnosed if serum levels of cardiac biomarkers (eg, troponin I) were above the 99th percentile upper reference limit >28 pg/mL, or new abnormalities were shown in electrocardiography and echocardiography) |

Low |

x |

low |

yes |

1 Adequate description of: source population or population of interest, sampling and recruitment, period and place of recruitment, in- and exclusion criteria, study participation, baseline characteristics.

2 Adequate response rate, information on drop-outs and loss to follow-up, no differences between participants who completed the study and those lost to follow-up.

3 Method of measurement is valid, reliable, setting of measurement is the same for all participants.

4 Important confounders are listed (including treatments), method of measurement is valid, reliable, setting of measurement is the same for all participants, important confounders are accounted for in the design (matching, stratification, initial assembly of comparable groups), or analysis (appropriate adjustment)

5 Enough data are presented to assess adequacy of the analysis, strategy of model building is appropriate and based on conceptual framework, no selective reporting.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Toraih, 2020 |

|

|

Parohan, 2020 |

|

|

Aikawa, 2020 |

Systematic review but described in a letter to the editor. Important information is missing (for example excluded papers and reason for exclusion) |

|

Li, X, 2020 |

|

|

Li, B, 2020 |

Wrong outcome: severe vs mild COVID-19 |

|

Li, J, 2020 |

Studies the association of severity of COVID with cardiac injury |

|

Huang, 2020 |

Wrong comparison: not focused on cardiac injury, comparing clinical characteristics of severe and non-severe patients |

|

Aboughdir, 2020 |

No systematic review |

|

Alexander, 2020 |

No original data |

|

Ammirati, 2020 |

No original data |

|

Ashraf, 2020 |

Wrong P, wrong I, no original data |

|

Benett, 2020 |

No original data, commentary |

|

Bangalore, 2020 |

wrong I, Wrong C |

|

Bansal, 2020 |

No comparison, wrong O, merely a description |

|

Bonow, 2020 |

No original data |

|

Cappannoli, 2020 |

Is not a comparison between covid patients with and without cardiac injury |

|

Chapman, 2020 |

Opinion, describes potential mechanisms |

|

Cheng, 2020 |

Focuses on potential mechanisms, no comparison |

|

Dong, 2020 |

Case study of 4 patients |

|

Fried, 2020 |

Case study of 4 cases |

|

Giustino, 2020 |

Wrong comparison, wrong I |

|

Guo, 2020 |

This paper was excluded because it was published during the search period of the included systematic review Santoso |

|

Jaffe, 2020 |

Describes possible mechanisms, no comparison |

|

Kang, 2020 |

No comparison, no I, focuses on mechanisms |

|

Kollias, Kyriakoulis, 2020 |

Wrong I, not systematic review |

|

Kollias, Anastasios, 2020 |

No original data, letter to the editor |

|

Lala, 2020 |

Wrong I: Troponin not defined as elevated or not but the absolute value is used in the analysis |

|

Larson, 2020 |

Not right comparison, wrong O |

|

Lazaridis, 2020 |

wrong comparison, |

|

Li, 2020 |

Wrong O |

|

Lim, 2020 |

No systematic literature overview. The 2 studies described here are also included in our set |

|

Madjid, 2020 |

Wrong comparison, Wrong I |

|

Si, 2020 |

Wrong I: Troponin not defined as elevated or not but the absolute value is used in the analysis |

|

Su, 2020 |

No comparison between patients with and without cardiac injury |

|

Tahir, 2020 |

No comparison, merely a description of cardiac manifestations |

|

Tersalvi, 2020 |

Focuses on the potential mechanism behind cardiac injury in COVID-19 patients |

|

Zeng, 2020 |

No original data |

|

Zhou, 2020 |

Wrong O: severe COVID-19 |

|

Zhu, 2020 |

No original data, focuses on underlying mechanism, no comparison |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld :

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.