Tweedelijns longrevalidatie en derdelijns behandelprogramma’s bij COPD

Uitgangsvraag

Wat zijn bij COPD-patiënten de belangrijkste indicaties waarbij 2e- en 3e-lijns longrevalidatie zinvol is?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg bij patiënten met COPD een multidisciplinair longrevalidatieprogramma binnen de 2e- of 3elijn (onder leiding en begeleiding van een longarts) in de volgende situaties:

- een verhoogde symptoomlast (CCQ > 1,8 of CAT ≥18)

- na een longaanval met ziekenhuisopname of >2 longaanvallen zonder ziekenhuisopname

- complexe problematiek

- complexe problematiek met ervaren fysieke beperkingen ondanks een lichtere symptoomlast (CCQ 1-1,8).

Voorafgaand aan de longrevalidatie dient een grondig assessment plaats te vinden. Het is belangrijk dat tijdens dit assessment het fysiek functioneren, lichaamssamenstelling, psychosociaal functioneren, functionele metingen, gezondheidsstatus en comorbiditeit in kaart worden gebracht.

Longrevalidatie dient te bestaan uit patiëntgerichte behandelingen die minimaal bestaan uit, maar niet beperkt zijn tot, fysieke training, educatie en gedragsverandering. Men dient de patiënten te stimuleren tot gedrag dat hun gezondheid bevordert en de motivatie en persoonlijke doelstellingen hierin mee te nemen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Ten aanzien van de relevante cruciale en belangrijke uitkomstmaten dyspnoe en kwaliteit van leven is de kwaliteit van het bewijs uit de literatuur als laag gewaardeerd, voornamelijk vanwege het ontbreken van (pogingen tot) blindering en heterogeniteit van de interventies. Bij de uitkomstmaten heropnames en 6MWD is de kwaliteit van het bewijs uit de literatuur als zeer laag gewaardeerd, omdat hier ook sprake was van potentiële publicatiebias en grote onzekerheid rondom het geschatte effect. De interventies varieerden van korte en weinig intensieve tot langdurige en intensieve trajecten, waarbij geen dosis-responseffecten te zien waren. In geen van de studies was een negatief effect te zien van longrevalidatie. Het is daarom op dit moment niet mogelijk om met grote zekerheid uitspraak te doen over de effecten van longrevalidatie op het risico van heropname en de inspanningstolerantie van patiënten. Longrevalidatie lijkt een positief effect te hebben op symptomen van dyspneu en de kwaliteit van leven van patiënten met COPD. Voor een betere schatting van de effecten van longrevalidatie zouden idealiter geblindeerde studies van voldoende grootte moeten worden uitgevoerd. Echter in de praktijk zijn deze studies niet goed uitvoerbaar.

Binnen de studies is geen onderscheid gemaakt tussen verschillende patiëntkenmerken ten aanzien van verschillen in de effectiviteit van longrevalidatie, met uitzondering van de subgroepanalyse op basis van ernst van de aandoening in de studie van Salman (2003). In deze subgroepanalyse werd geen verschil in effectiviteit van longrevalidatie gevonden.

Binnen de geïncludeerde studies is geen melding gedaan van (ernstige) neveneffecten van longrevalidatie. Er werd in enkele studie gevonden dat patiënten in de controlegroep niet de volledige follow-up vervolmaakten, juist vanwege hun randomisatie in deze controlegroep. Dit heeft kunnen leiden tot vertekening van de resultaten, maar het versterkt wel de observatie dat in de behandelgroepen met een lagere loss to follow-up weinig tot geen (ernstige) neveneffecten zijn voorgekomen, vergeleken met het achterwege laten van behandeling van patiënten met COPD.

Voor alle uitkomstmaten geldt dat de grootte van het effect van longrevalidatie redelijk zou kunnen worden genoemd, maar dat de verscheidenheid in soorten interventies, de diversiteit in patiëntengroepen voor wat betreft ernst van COPD, en de follow-up duur ervoor zorgt dat de zekerheid waarmee conclusies kunnen worden getrokken uit de resultaten zeer beperkt is. Dit is onder meer te zien aan de breedte van de gerapporteerde betrouwbaarheidsintervallen.

In 2015 hebben Mc Carthy e.a. een Cochrane review gedaan. Deze Cochrane kwam niet uit de literatuursearch vanwege de diversiteit van de toegepaste behandelingen.

De gehanteerde definitie in deze studie voor pulmonary rehabilitation was: een beweegprogramma van minimaal 4 weken met of zonder educatie en/of een psychologische interventie gedurende het programma.

De conclusie van de studie van McCarthy 2015 toont een verbetering van kwaliteit van leven (CRQ, SGRQ), maximale inspanningscapaciteit en verbetering bij de 6 minuut looptest. Er bestond geen duidelijk verschil in uitkomsten tussen klinische (complex) en poliklinische (minder complexe) programma’s.

De auteurs concluderen dat longrevalidatie (volgens bovenstaande definitie) kortademigheid en vermoeidheid vermindert, emotioneel verbetering geeft, de gezondheidsgerelateerde kwaliteit van leven en de inspanningscapaciteit verbetert.

Tevens is er een afname van het risico op heropname na recente opname i.v.m. COPD-longaanvallen en een sterke reductie in angst- en depressiesymptomen.

Een subgroepanalyse laat zien dat er een verschil in het effect van behandeling was tussen de hospital based en community based programma’s op de CRQ.

Er was geen verschil in uitkomst op de CRQ tussen de beweegprogramma’s (monodisciplinair) en de complexere multidisciplinaire programma’s. De betekenis van deze bevinding voor de Nederlandse situatie is nog niet duidelijk vanwege de diversiteit aan programma’s en settings die zich slecht laat vergelijken met de Nederlandse situatie. In Nederland spreken we alleen van longrevalidatie bij multidisciplinaire behandelprogramma’s.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voorafgaand aan een longrevalidatieprogramma is een grondig assessment van de patiënt noodzakelijk om aanwezige pathofysiologische grootheden te detecteren en de functionele status, emotionele en gedragsfactoren en de gezondheidsstatus te identificeren. Hierbij vormen de persoonlijke doelstellingen de drijfveer om aan een longrevalidatieprogramma deel te nemen en daarom dienen zij meegenomen te worden in het behandelplan. Deze persoonlijke doelstellingen kunnen in professionele doelstellingen worden verweven. Deze doelstellingen zijn voor iedere patiënt uniek en daarom dient het behandelprogramma geïndividualiseerd te worden. De belangrijkste doelstellingen van de patiënten zijn op groepsniveau in de domeinen mobiliteit (o.a. lopen, gebruik maken van transporthulpmiddelen), recreatie en ontspanning (o.a. hobby’s, sport), huiselijk leven (o.a. huishouden, koken, boodschappen doen, huisdieren verzorgen), interpersoonlijke relaties onderhouden en zelfzorg ADL (Mehdipour, 2021). De voorkeuren van patiënten aangaande de behandeling zijn fysieke training, longfysiotherapie, educatie en interventies betreffende de geestelijke gezondheid (Damm, 2021).

De prioriteit bij de meerderheid van de patiënten ligt op het domein van de mobiliteit. Voor veel patiënten is dat een voorwaarde om andere doelstellingen te kunnen bereiken. Door verbetering van mobiliteit wordt de autonomie vergroot en neemt hun kwaliteit van leven toe. Er is echter ook een groep patiënten die, ondanks een duidelijke indicatie, afziet van longrevalidatie. Dit geldt ook voor patiënten die in aanmerking komen voor longrevalidatie die na een ziekenhuisopname met een longaanval. Redenen waarom ze afzien van longrevalidatie zijn: transportproblemen, zich te ziek of te beperkt voelen, gebrek aan sociale steun of andere verplichtingen zoals werk, familie of vakantie (Mathar, 2016; Benzo, 2015).

Tussen patiënten die aan longrevalidatie deelnamen na een COPD-longaanval of geen COPD-longaanval hebben doorgemaakt zijn geen verschillen in waarden of voorkeuren. Om meer inzicht te krijgen in welke patiënten baat hebben bij longrevalidatie werden in een Nederlandse studie vier clusters geïdentificeerd op basis van de mate van respons op een longrevalidatieprogramnma: zeer goede, goede, matige, en slechte responders (Spruit, 2015). Het aantal zeer goede en goede responders is hoger na een longrevalidatieprogramma. Op basis van alleen fysiologische parameters kan geen onderscheid gemaakt worden tussen de vier clusters. In de groep van de zeer goede responders werd aanvankelijk zelfs de hoogste ziektelast gevonden. De doelen van de patiënten variëren naarmate men meer beperkt is in het dagelijks leven. Voor erg verzwakte patiënten die in een rolstoel zitten kan het doel zijn om met een rollator te kunnen lopen terwijl een patiënt die redelijk mobiel is als doel kan hebben om het werk te hervatten.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De gunstige effecten van longrevalidatie vertalen zich in kosteneffectiviteit. Er zijn reeds oudere studies (15-20 jaar oud) die lieten zien dat kosten bespaard werden op het gebruik van gezondheidszorg zoals minder ziekenhuisopnames, minder dagen verblijf in het ziekenhuis en mindere bezoeken aan de spoedeisende hulp (Griffiths, 2000; Hui, 2003; Cecins, 2008). Een recente studie bevestigde deze kostenbesparingen (Walsh, 2019). Deze studie liet zien dat het aantal longgerelateerde ziekenhuisopnames, het aantal dagen verblijf in het ziekenhuis en het aantal bezoeken aan de spoedeisende hulp significant afnam binnen één jaar na het longrevalidatieprogramma.

Eén studie uitgevoerd in een Nederlands Kenniscentrum voor Complex Chronische Longaandoeningen toonde aan dat na longrevalidatie het aantal longaanvallen en het aantal ziekenhuisopnames afnam (Van Ranst e.a. 2014).

De meerwaarde van klinische, complexe multidisciplinaire behandelprogramma’s zoals die in Nederland in de 3e lijns centra wordt geboden, ten opzichte van minder intensieve vormen van longrevalidatie in de 2e lijns centra, is voor mensen met COPD niet aangetoond. Hierdoor is ook de kosteneffectiviteit onduidelijk. Er is beperkt onderzoek gedaan naar deze behandelprogramma’s; en de kwaliteit van het beschikbare bewijs dat de meerwaarde aan zou moeten tonen ten opzichte van minder intensieve longrevalidatie is laag (ZiNl, 2019).

Longrevalidatie is kosteneffectief bij COPD-patiënten die een COPD-longaanval hadden doorgemaakt (Ko, 2011; Katajisto, 2017). Bij 57% van de patiënten die succesvol gerevalideerd hadden bleek dat 10-20% ziekenhuisdagen per jaar konden worden bespaard (Katajisto, 2017). Overigens betrof dit een schatting en geen berekening.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

In opdracht van Zorginstituut Nederland heeft Panaxea in 2019 een richtlijnenonderzoek uitgevoerd naar de effectiviteit van longrevalidatie bij COPD. Het doel was om inzicht te krijgen in de aanbevelingen voor verwijzing naar een multidisciplinair behandelprogramma en op het effect van longrevalidatie voor COPD-patiënten. Ook hier liepen de onderzoekers tegen dezelfde problemen op m.b.t. de lage kwaliteit van het bewijs, door de grote diversiteit in aangeboden programma’s en de onmogelijkheid tot blinderen, waardoor een deel van de studies niet geïncludeerd kon.

Men gaf aan dat patiënten met COPD met participatieproblemen door de ziekte in aanmerking komen voor longrevalidatie. Men concludeerde dat richtlijnen uniform zijn in hun uitspraak dat longrevalidatie een effectieve behandeloptie is bij COPD. Aanbevelingen om longrevalidatie voor te schrijven zijn krachtiger geformuleerd bij patiënten in een gevorderd stadium van de ziekte en een hoge ziektelast dan bij patiënten met een lage ziektelast. Bij patiënten met een hoge ziektelast gaat het om een CCQ >1,8 of een CAT >18 punten.

Patiënten die opgenomen worden voor een longaanval vallen onder de categorie van hoge ziektelast. De complexiteit van de individuele patiënt met COPD voor wat betreft de gezondheidsdeterminanten zoals aard, ernst en fase van de aandoening, comorbiditeiten en psychische belastbaarheid, bepaalt of de longrevalidatie plaatsvindt in de tweede lijn poliklinisch) of dat de patiënt verwezen wordt voor behandeling in de derde lijn (klinisch of poliklinisch), in één van de vijf Kenniscentra voor Complex Chronische Longaandoeningen (KCCL, https://kenniscentraccl.nl). Niet elk ziekenhuis biedt een 2e lijns longrevalidatie programma aan.

Longrevalidatie en behandeling in een Kenniscentrum voor complex chronische longaandoeningen wordt bekostigd vanuit de basisverzekering. Uit navraag bij ziekenhuizen blijkt dat vergoeding voor tweedelijns longrevalidatie niet altijd kostendekkend is. Dit belemmert initiatieven in de tweede lijn.

Een belemmering om te starten met een programma kan zijn dat de patiënt opziet tegen een intensieve behandeling die soms verder van huis is, en dat het vervoer niet meegenomen is in de vergoeding van de behandeling.

Er zijn een aantal voorwaarden waaraan een longrevalidatie programma dient te voldoen: de behandeling dient multidisciplinair van opzet te zijn, er dient voorafgaand een grondig assessment te hebben plaatsgevonden naar de fysieke toestand (longfunctie, conditie, lichaamssamenstelling), psychosociaal functioneren (gevoelens van angst en depressie, gedrag), mate van kortademigheid, ADL, gezondheidsstatus/kwaliteit van leven en intake van voeding; er dient minimaal maar niet beperkt te worden tot fysieke training, educatie en gedragsverandering en men dient de patiënten te stimuleren tot gezondheidsbevorderend gedrag (Spruit, 2013). Door gebruik te maken van een assessment voor de verwijzing betekent dit dat de beschikbare capaciteit beter benut kan worden en de zorg passend is. De werkgroep is van mening dat vanwege de specifieke expertise die vereist is, longrevalidatie altijd onder leiding van een longarts dient te gebeuren.

Tijdens de longrevalidatie zijn de cognitieve vermogens en de leerbaarheid belangrijk voor het beklijven van het resultaat van de longrevalidatie. Afkomstig zijn uit een lagere sociale klasse, een migratieachtergrond, een laag opleidingsniveau en geringe gezondheidsvaardigheden kunnen een belemmering vormen om de opgedane kennis en vaardigheden in de thuissituatie voort te zetten. Indien hier sprake van is, wordt er tijdens het complexe multidisciplinaire behandelprogramma specifiek aandacht aan besteed, om het geleerde beter te laten beklijven en gezondheidsvaardigheden te verbeteren.

Vanuit de sectie COPD van de NVALT is er een werkgroep samengesteld die de opdracht heeft om de indicaties voor 2e lijns longrevalidatie in kaart te brengen. Een definitief voorstel volgt in het najaar van 2023.

Er zijn belemmerende factoren op het gebied van de implementatie van longrevalidatie.

Waarschijnlijk krijgen veel minder patiënten de beschikbare zorg dan noodzakelijk is.

Iedere patiënt met COPD met bovengenoemde indicatie voor longrevalidatie heeft in principe toegang tot deze behandeling. Men is afhankelijk van de betreffende zorgverlener die het gesprek met de patiënt aangaat om door te verwijzen naar een longrevalidatieprogramma. Indien dit niet gebeurt en de patiënt niet mondig genoeg is of de kennis mist om zelf om deze hulp te vragen bestaat de mogelijkheid dat deze noodzakelijke behandeling toch niet geboden wordt. Men heeft in Nederland circa 600.000 mensen met COPD geïdentificeerd, maar de doorverwijzing naar tertiaire longrevalidatie bedraagt maar 0,1% (ZiNL 2019). Het totaal percentage van COPD-patiënten dat enige vorm van een oefenprogramma volgt is slechts 5%.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

- Slechts 5 % van alle COPD-patiënten volgt enige vorm van beweeg-/fysiotherapie of longrevalidatie.

- De beweegprogramma’s die aangeboden worden in de 1e lijn zijn m.n. gericht op verbetering van de fysieke capaciteit en activiteit van COPD-patiënten.

- Meer complexe problematiek heeft een multidisciplinaire aanpak nodig die op de verschillende domeinen verbetering kan bieden. Deze programma’s worden meestal aangeboden in de 2e en 3e lijn, waarbij in de 3e lijn ook klinische longrevalidatie mogelijk is, de complexiteit hoger is en de behandeling intensiever is dan in de 2e lijn. In de praktijk worden, om het onderscheid tussen beiden te verduidelijken, de termen “tweedelijns longrevalidatie” en “derdelijns behandeling van complex chronische longaandoeningen” gehanteerd. Er bestaan specifieke inclusiecriteria voor behandeling in de 3e lijns longrevalidatie opgesteld door de KCCL (Kenniscentra Complex Chronisch Longfalen). De inclusiecriteria voor de 2e lijns longrevalidatie zijn nog in ontwikkeling.

- Longrevalidatie is een behandeling die gebaseerd is op een gedegen assessment gevolgd door op de patiënt afgestemde behandelingen, waaronder in ieder geval fysieke training, educatie en interventies gericht op gedragsverandering en verbetering van de fysieke en psychische conditie van mensen met een chronische longziekte met als doel op lange termijn verbetering van gezondheidsbevorderend gedrag (Spruijt 2013).

- Voor deze uitgangsvraag zijn we uit gegaan van 2e en 3e lijns programma’s. In de literatuur wordt echter over het algemeen geen onderscheid gemaakt tussen de lijnen zoals wij die in Nederland kennen. In studies is het gebruikelijk om mono- en multidisciplinaire behandeling te vergelijken.

- In de richtlijn wordt de Grade systematiek gehanteerd om het level of evidence bij een studie te beoordelen. Hierdoor worden de studies die longrevalidatie betreffen altijd lager gewaardeerd omdat blindering niet mogelijk is en vanwege de heterogeniciteit van de onderzoekspopulatie.

- Er bestaat een behoefte om meer patiënten van longrevalidatie en fysiotherapie gebruik te laten maken. De behandeling moet wel passend en effectief zijn en gericht zijn op het behalen van persoonlijke behandeldoelen.De vraag is welke patiënten profiteren van longrevalidatie.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of pulmonary rehabilitation compared to usual care on hospitalisation rate in patients with COPD.

Sources: Moore, 2016 |

|

Low GRADE |

Pulmonary rehabilitation may improve dyspnoea symptoms in patients with COPD, when compared to usual care.

Sources: Salman, 2003; Burge, 2020; McCarthy, 2015 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of pulmonary rehabilitation compared to usual care on 6-minute walking distance in patients with COPD.

Sources: Salman, 2003; Burge, 2020; McCarthy, 2015 |

|

Low GRADE |

Pulmonary rehabilitation may improve health-related quality of life in patients with COPD, when compared to usual care.

Sources: Salman, 2003; Burge, 2020; McCarthy, 2015 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Four systematic reviews (SRs) were included, which in total included 5,321 patients with COPD (Salman, 2003; McCarthy, 2015; Moore, 2016; Burge, 2020). In general, the average age of included patients was between 60 and 70 years old, but the review of Moore (2016) did not report averages for the included trials. Disease severity varied from mild to severe. Salman (2003) performed meta-analyses stratified by disease severity. All four reviews investigated the effects of pulmonary rehabilitation on several outcomes. The intervention was not clearly defined and varied largely between studies and within SRs. This may lead to heterogeneity in the effects of interest. In addition, no studies blinded or attempted to blind participants to the allocated intervention. This may bias the results as well. Below, we describe the systematic reviews per study.

Salman (2003) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the effect of pulmonary rehabilitation on 6-minute walking distance (6-MWD) and shortness of breath, based on a literature search up to September 2000. The studies included in this systematic review were RCTs comparing pulmonary rehabilitation at least 3 times a week for at least 4 weeks to control (which was not further described) in patients with COPD and not asthma, with a FEV <70% predicted or FEV1 /FVC <70% predicted. Twenty studies were included, of which 16 investigated upper extremity, 18 investigated lower extremity, and 8 studies investigated respiratory muscle rehabilitation, in different combinations. The reported outcomes were 6-minute walking distance and shortness of breath. Follow-up time was between 6 weeks and 12 months.

McCarthy (2015) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the effect of a minimum of four weeks of aerobically demanding pulmonary rehabilitation on several outcomes including health-related quality of life, symptoms, and physical capabilities in patients with COPD. They performed a literature search up to March 2014, and included RCTs that studied the effects of pulmonary rehabilitation compared to usual care on CRQ, SGRQ, 6-MWD, and other physical performance indicators in patients with stable COPD. 65 studies were included with 3822 participants with mean ages between 59 and 74 years. The follow-up time was between 4 weeks and 24 months. 37 studies were used in this guideline, as these investigated hospital outpatient interventions. Two RCTs that were included in the review were not relevant to this guideline, because the patients who were included had an exacerbation prior to study inclusion.

Moore (2016) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the effect of pulmonary rehabilitation on rehospitalisation in patients with COPD. They performed a literature search up to September 2015, and included RCTs that studied the effects of pulmonary rehabilitation compared to control on rehospitalisation rates in patients with stable COPD or after an acute exacerbation of COPD. Ten studies were included, but no average age or other patient characteristics were reported. The follow-up time was between 8 weeks and 12 months. Rehospitalisation was defined as physician and ER visits with AECOPD as the primary reason for admission/visit according to the International Classification of Disease (ICD): ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes. The outcome was expressed in events per person-year, and the effect was reported as a rate-ratio.

Burge (2020) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the effect of various treatments on physical activity in patients with COPD. They performed a literature search up to June 2019, and included RCTs on any intervention where objectively-assessed physical activity or sedentary behaviour was a measured outcome in people with COPD. 76 studies were included in a qualitative analysis, of which 6 were relevant to this guideline, as these investigated pulmonary rehabilitation as intervention and had relevant outcomes to this guideline: 6-minute walking distance, and SGRQ total and dyspnoea score, and CRQ dyspnoea score.

Results

Hospitalisations

For hospitalisations, one SR reported a rate ratio (Moore, 2016) based on a pooled analysis in 498 patients over 10 studies, in whom 185.2 hospitalisations were reported in 191.5 patient-years in the control group, and 114 were reported in 185.3 patient-years in the pulmonary rehabilitation group. The pooled rate ratio was 0.64 (95% CI 0.44 to 0.93).

Dyspnoea

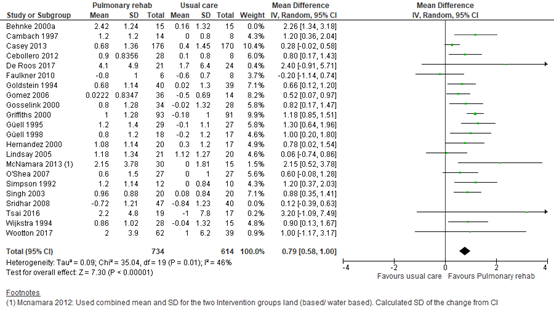

For dyspnoea, three SRs reported a (standardized) mean difference based on pooled analysis in 723 patients in 12 studies (Salman, 2003), 397 patients over 4 studies (Burge, 2020), and 1453 patients over 19 studies (McCarthy, 2015). Salman (2003) reported a standardized mean difference of 0.62 (95% CI 0.26 to 0.91) in dyspnoea score on the CRQ questionnaire in favour of pulmonary rehabilitation. No individual study data was available for Salman, 2003, so these data could not be included in the pooled estimate. We pooled the data from the studies included in Burge (2020) and McCarthy (2015), and calculated a mean difference in CRQ dyspnoea score of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.58 to 1.00) in favour of pulmonary rehabilitation. See Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Forest plot of meta-analysis of studies investigating the effect of pulmonary rehabilitation on CRQ dyspnoea score

CI, confidence interval; CRQ, chronic respiratory questionnaire; I2, heterogeneity; IV; inverse variance; SD, standard deviation

6-minute walking distance

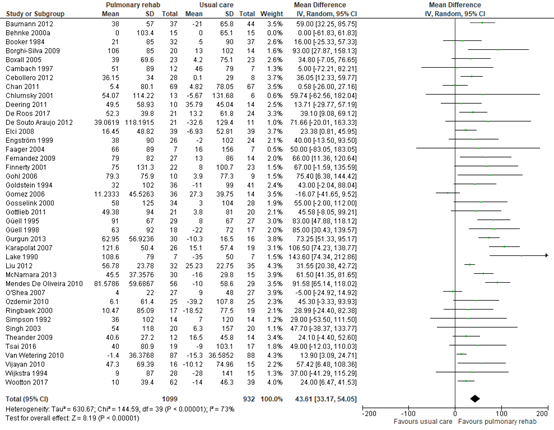

For 6-minute walking distance, three SRs reported a standardized mean difference based on pooled analysis in 979 patients in 20 studies (Salman, 2003), 231 patients over 3 studies (Burge, 2020), and 2403 patients over 37 studies (McCarthy, 2015). Salman (2003) reported a standardized mean difference of 0.71 (95% CI: 0.43 to 0.99), which was equivalent to 50.57 meters (95% CI: 30.3 to 70.8) in favour of pulmonary rehabilitation. No individual study data was available for Salman, 2003, so these data could not be included in the pooled estimate. We pooled the data from the studies included in Burge (2020) and McCarthy (2015), and calculated a mean difference in 6-minute walking distance of 43.61 meters (95% CI: 33.17 to 54.05) in favour of pulmonary rehabilitation. See Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Forest plot of meta-analysis of studies investigating the effect of pulmonary rehabilitation on 6-minute walking distance

CI, confidence interval; I2, heterogeneity; IV; inverse variance; SD, standard deviation

Quality of life

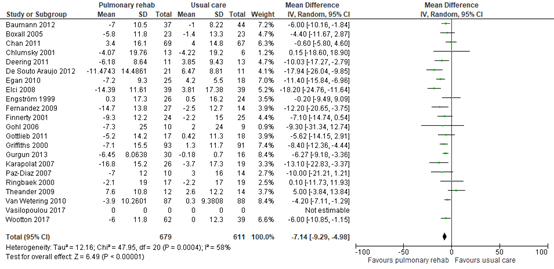

Two SRs reported a mean difference in SGRQ score based on analyses in two studies including 186 patients (Burge, 2020) and 19 studies including 1453 patients (McCarthy, 2015). We pooled the data from the studies included in Burge (2020) and McCarthy (2015), and calculated a mean difference in SGRQ of -7.14 (95% CI: -9.29 to -4.98) in favour of pulmonary rehabilitation. See Figure 3.

Figure 3 – Forest plot of meta-analysis of studies investigating the effect of pulmonary rehabilitation on SGRQ.

CI, confidence interval; I2, heterogeneity; IV; inverse variance; SD, standard deviation; SGRQ, St Georges’ Respiratory Questionnaire

Other outcomes

No studies reported on exacerbation rate and mortality.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure hospitalisations was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (one level due to risk of bias: lack of blinding), conflicting results and heterogeneity in patients and interventions (one level due to inconsistency), and imprecision (confidence interval crossed MCID).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure dyspnoea started as high (SR of RCTs), and was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (one level due to risk of bias: lack of blinding); and heterogeneity in patients and interventions (one level due to inconsistency).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure 6-minute walking distance started as high (SR of RCTs), and was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (two levels due to high risk of bias: lack of blinding, no information on randomisation and concealment of allocation, risk of publication bias); conflicting results and heterogeneity in patients and interventions (one level due to inconsistency).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life started as high (SR of RCTs), and was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (one level due to risk of bias: lack of blinding); and heterogeneity in patients and interventions (one level due to inconsistency).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

Does pulmonary rehabilitation improve outcomes in patients with COPD without an exacerbation as compared to no pulmonary rehabilitation?

P: patients COPD patients without exacerbation referred for pulmonary

rehabilitation

I: intervention presence of patient characteristics: mood problems;

fatigue; activity monitor; low CCQ; low 6-minute walking distance.

C: control absence of patient characteristics under I

O: outcome exercise capacity (6MWT), quality of life (CCQ), dyspnoea symptoms,

exacerbation rate, hospitalisation rate, mortality

Relevant outcome measures

The working group considered 6-MWD, mortality and muscle strength as crucial outcomes for decision-making. Quality of life, hospitalization rate and exacerbation rate were considered important outcomes for decision making.

The working group defined a set of minimal clinically (patient) important differences (see introduction for further details). For this intervention, the following set was chosen:

- Exacerbation reduction: ≥20%

- Mortality: ≥10% difference in relative risk

- Pneumonia: ≥20% difference in relative risk

- CAT-score: >2 units

- CCQ-score: >0.4 units

- SGRQ-score: ≥4 units

- Borg scale: ≥1 point

- 6-MWT: ³30 meters

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 8 September 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 2100 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews that included studies performed in patients with COPD, and investigating the effects of pulmonary rehabilitation on the relevant outcomes compared to the effect of no intervention or usual care. 29 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 25 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 4 studies were included.

Results

Four studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Benzo R, Wetzstein M, Neuenfeldt P, McEvoy C. Implementation of physical activity programs after COPD hospitalisations: Lessons from a randomized study. Chron Respir Dis. 2015 Feb;12(1):5-10. doi: 10.1177/1479972314562208. Epub 2014 Dec 15. PMID: 25511306.

- Cecins N, Geelhoed E, Jenkins SC. Reduction in hospitalisation following pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD. Aust Health Rev. 2008 Aug;32(3):415-22. doi: 10.1071/ah080415. PMID: 18666869.

- Damm K, Lingner H, Schmidt K, Aumann-Suslin I, Buhr-Schinner H, van der Meyden J, Schultz K. Preferences of patients with asthma or COPD for treatments in pulmonary rehabilitation. Health Econ Rev. 2021 Apr 17;11(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s13561-021-00308-0. PMID: 33866476

- Griffiths TL, Burr ML, Campbell IA, Lewis-Jenkins V, Mullins J, Shiels K, Turner-Lawlor PJ, Payne N, Newcombe RG, Ionescu AA, Thomas J, Tunbridge J. Results at 1 year of outpatient multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000 Jan 29;355(9201):362-8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)07042-7. Erratum in: Lancet 2000 Apr 8;355(9211):1280. Lonescu AA (corrected to Ionescu AA). PMID: 10665556.

- Hui KP, Hewitt AB. A simple pulmonary rehabilitation program improves health outcomes and reduces hospital utilization in patients with COPD. Chest. 2003 Jul;124(1):94-7. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.1.94. PMID: 12853508.

- Katajisto M, Laitinen T. Estimating the effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation for COPD exacerbations: reduction of hospital inpatient days during the following year. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017 Sep 22;12:2763-2769. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S144571. PMID: 28989279; PMCID: PMC5624742.

- Ko FW, Dai DL, Ngai J, Tung A, Ng S, Lai K, Fong R, Lau H, Tam W, Hui DS. Effect of early pulmonary rehabilitation on health care utilization and health status in patients hospitalized with acute exacerbations of COPD. Respirology. 2011 May;16(4):617-24. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01921.x. PMID: 21199163.

- Mathar H, Fastholm P, Hansen IR, Larsen NS. Why Do Patients with COPD Decline Rehabilitation. Scand J Caring Sci. 2016 Sep;30(3):432-41. doi: 10.1111/scs.12268. Epub 2015 Oct 1. PMID: 26426088.

- McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, Murphy K, Murphy E, Lacasse Y. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD003793. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003793.pub3.

- Mehdipour A, O'Hoski S, Beauchamp MK, Wald J, Kuspinar A. Health Qual Life Outcomes. Content validity of preference-based measures for economic evaluation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2021 Mar 20;19(1):101. doi: 10.1186/s12955-021-01744-6. PMID: 33743746

- Health Qual Life Outcomes. Content validity of preference-based measures for economic evaluation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2021 Mar 20;19(1):101. doi: 10.1186/s12955-021-01744-6. PMID: 33743746

- PMID: 33743746

- Raskin J, Spiegler P, McCusker C, ZuWallack R, Bernstein M, Busby J, DiLauro P, Griffiths K, Haggerty M, Hovey L, McEvoy D, Reardon JZ, Stavrolakes K, Stockdale-Woolley R, Thompson P, Trimmer G, Youngson L. The effect of pulmonary rehabilitation on healthcare utilization in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: The Northeast Pulmonary Rehabilitation Consortium. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2006 Jul-Aug;26(4):231-6. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200607000-00006. PMID: 16926687.

- van Ranst D, Stoop WA, Meijer JW, Otten HJ, van de Port IG. Reduction of exacerbation frequency in patients with COPD after participation in a comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation program. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014 Oct 3;9:1059-67. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S69574. PMID: 25336938; PMCID: PMC4199855.

- Rispoli M, Salvi R, Cennamo A, Di Natale D, Natale G, Meoli I, Gioia MR, Esposito M, Nespoli MR, De Finis M, Buono S, Corcione A, Lavoretano S, Bianco A, Fiorelli A, Curcio C, Perrotta F. Effectiveness of home-based preoperative pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD patients undergoing lung cancer resection. Tumori. 2020 Feb 23:300891619900808. doi: 10.1177/0300891619900808. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32090715.

- Singh SJ, ZuWallack RL, Garvey C, Spruit MA; American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Task Force on Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Learn from the past and create the future: the 2013 ATS/ERS statement on pulmonary rehabilitation. Eur Respir J. 2013 Nov;42(5):1169-74. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00207912. PMID: 24178930.

- Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, ZuWallack R, Nici L, Rochester C, Hill K, Holland AE, Lareau SC, Man WD, Pitta F, Sewell L, Raskin J, Bourbeau J, Crouch R, Franssen FM, Casaburi R, Vercoulen JH, Vogiatzis I, Gosselink R, Clini EM, Effing TW, Maltais F, van der Palen J, Troosters T, Janssen DJ, Collins E, Garcia-Aymerich J, Brooks D, Fahy BF, Puhan MA, Hoogendoorn M, Garrod R, Schols AM, Carlin B, Benzo R, Meek P, Morgan M, Rutten-van Mölken MP, Ries AL, Make B, Goldstein RS, Dowson CA, Brozek JL, Donner CF, Wouters EF; ATS/ERS Task Force on Pulmonary Rehabilitation. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013 Oct 15;188(8):e13-64. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1634ST. Erratum in: Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014 Jun 15;189(12):1570. PMID: 24127811.

- Spruit MA, Augustin IM, Vanfleteren LE, Janssen DJ, Gaffron S, Pennings HJ, Smeenk F, Pieters W, van den Bergh JJ, Michels AJ, Groenen MT, Rutten EP, Wouters EF, Franssen FM; CIRO+ Rehabilitation Network. Differential response to pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD: multidimensional profiling. Eur Respir J. 2015 Dec;46(6):1625-35. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00350-2015. Epub 2015 Oct 9. PMID: 26453626.

- Walsh JR, Pegg J, Yerkovich ST, Morris N, McKeough ZJ, Comans T, Paratz JD, Chambers DC. Longevity of pulmonary rehabilitation benefit for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-health care utilisation in the subsequent 2 years. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2019 Nov 24;6(1):e000500. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2019-000500. PMID: 31803476; PMCID: PMC6890390.

- Zhou K, Lai Y, Wang Y, Sun X, Mo C, Wang J, Wu Y, Li J, Chang S, Che G. Comprehensive Pulmonary Rehabilitation is an Effective Way for Better Postoperative Outcomes in Surgical Lung Cancer Patients with Risk Factors: A Propensity Score-Matched Retrospective Cohort Study. Cancer Manag Res. 2020 Sep 23;12:8903-8912. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S267322. PMID: 33061586; PMCID: PMC7520117.

- Verbetersignalement Zorgtraject van mensen met COPD Zinnige Zorg. https://www.zorginstituutnederland.nl/binaries/zinl/documenten/rapport/2019/12/10/zinnige-zorg-verbetersignalement-copd/Zinnige+Zorg+-+Verbetersignalement+Zorgtraject+van+mensen+met+COPD.pdf DATUM: 10 DECEMBER 2019

Evidence tabellen

Evidence tables

Tweede- en derdelijnsrevalidatie bij COPD

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Ramdas, 2003 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

A: Lake, 1990 B: Gosselink, 1996 C: Wijkstra, 1995 D: Simpson, 1992 E: Guyatt, 1992 F: Strijbos, 1996 G: McGavin, 1977 H: Cambach, 1997 I: Cockcroft, 1981 J: Bendstrup, 1997 K: Sassi-Dambron, 1995 L: Griffith, 2000 M: Wedzicha, 1998a N: Troosters, 2000 O: Bauldoff, 1996 P: Weiner, 1992 Q: Goldstein, 1994 R: Jones, 1985 S: Engstrom, 1999 T: Wedzicha, 1998b U: Guell, 2000

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: not reported

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria SR: RCTs comparing pulmonary rehabilitation at least 3 times a week for at least 4 weeks to control (which was not further described) in patients with COPD and not asthma, with a FEV <70% predicted or FEV1 /FVC <70% predicted

Exclusion criteria SR: no asthma

20 studies (one duplicate) included, 979 patients

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N, mean age (sd) A: 14; 66 (2) B: 19; - (-) C: 36; 62.1 (5) D: 28; 71 (5) E: 82; 66 (7.5) F: 30; 61 (5.3) G: 24; 59 (6.8) H: 19; 62 (7) I: 34; 61 (4.9) J: 32; 64 (2) K: 77; 67.4 (8) L: 200; 68.2 (9.1) M: 56; 68.6 (7.7) N: 62; 61 (8) O: 20; 62 (14) P: 24; 65 (2.8) Q: 77; 66 (7) R: 14; 63 (7.2) S: 50; 66.4 (5.4) T: 54; 72.5 (6) U: 47; 64 (7)

Sex: (% male)

Not reported

Groups comparable at baseline? A: probably yes B: probably yes C: probably yes D: probably yes E: probably yes F: probably yes G: probably yes H: probably yes I: probably yes J: probably yes K: probably yes L: probably yes M: probably yes N: probably yes O: probably yes P: probably yes Q: probably yes R: probably yes S: probably yes T: probably yes U: probably yes

|

Describe intervention:

A: upper-extremity rehabilitation (U)+lower-extremity rehabilitation (L) B: U+L C: U+L+respiratory muscle rehabilitation (R) D: U+L E: R F: L G: L H: U+L+R I: U+L J: U+L K: R L: U+L M: U+L N: U+L O: U P: U+L+R Q: U+L+R R: U+L S: U+L+R T: U+L U: R+L |

Describe control:

A: not described B: not described C: not described D: not described E: not described F: not described G: not described H: not described I: not described J: not described K: not described L: not described M: not described N: not described O: not described P: not described Q: not described R: not described S: not described T: not described U: not described |

End-point of follow-up:

A: 8w B: 3m C: 12w D: 8w E: 6m F: 3m G: 3m H: 3m I: 7m J: 12w K: 6w L: 6w M: 8w N: 6m O: 8w P: 6m Q: 6m R: 10w S: 12m T: 8w U: 6m

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: I:not reported; C: not reported B: I:not reported; C: not reported C: I:not reported; C: not reported D: I:not reported; C: not reported E: I:not reported; C: not reported F: I:not reported; C: not reported G: I:not reported; C: not reported H: I:not reported; C: not reported I: I:not reported; C: not reported J: I:not reported; C: not reported K: I:not reported; C: not reported L: I:not reported; C: not reported M: I:not reported; C: not reported N: I:not reported; C: not reported O: I:not reported; C: not reported P: I:not reported; C: not reported Q: I:not reported; C: not reported R: I:not reported; C: not reported S: I:not reported; C: not reported T: I:not reported; C: not reported U: I:not reported; C: not reported

|

Outcome measure-1 Walking distance

Effect measure: standardized mean difference 0.71 (95% CI 0.43 to 0.99) favoring PR, equivalent to 50.57 meters (95% CI: 30.3 to 70.8)

Outcome measure-2 Dyspnoea

Standardized mean difference: 0.62 (95% CI 0.26 to 0.91) favoring PR Heterogeneity (I2):

|

Facultative:

The results support the role of PR in COPD, with beneficial effects on walking distance and dyspnoea.

Relatively dated study that included mostly small RCTs which investigate a variety of pulmonary rehabilitation interventions. Not much information on the included studies.

For walking distance: Very low GRADE, downgraded for inconsistency (interventions and effects), and high risk of bias (lack of blinding, no information on randomisation and concealment of allocation)

For dyspnoea: Very low GRADE, downgraded for inconsistency (interventions and effects), and high risk of bias (lack of blinding, no information on randomisation and concealment of allocation)

Sensitivity analyses performed for mild/moderate COPD and severe COPD, no significant difference in effect size was reported.

Both clinical and statistical heterogeneity, but the review attempted to explain. |

|

Moore, 2016 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

A: Behnke, 2003 B: Boxall, 2005 C: Eaton, 2009 D: Guell, 2000 E: Ko, 2011 F: Liu, 2012 G: Man, 2004 H: Murphy, 2005 I: Roman, 2013 J: Seymour, 2010

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: not reported

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria SR: RCTs comparing pulmonary rehabilitation to usual care in patients with COPD (FEV1 <70% predicted)

Exclusion criteria SR:

10 studies included, 498 patient

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N, mean age A: 26; - (-) B: 46; >60 (-) C: 69; - (-) D: 60; - (-) E: 60; - (-) F: 67; - (-) G: 34; - (-) H: 31; - (-) I: 45; - (-) J: 60; - (-)

Sex: Not reported

Groups comparable at baseline? Probably yes

|

Describe intervention:

A: 10d hospital-based training + home-based walking B: 12w homebased PR, first 6w weekly pt visit. C: inpatient daily 30m+outpatient 1h biweekly D: 5 times per week 30min cycling E: 8w 3 times per week PR F: 1w training, 6m three times per week 1h aerobic exercise G: 8w 2 times per week aerobic and strength training H: 6w twice a week aerobic and strength training I: 6w three times per week 60min respiratory and muscle training + weekly physiotherapy for 1y J: 8w 2 times per week aerobic and strength training |

Describe control:

A: no instruction B: no intervention C: standard care D: not described E: usual care+instruction F: education G: usual care H: usual care I: usual care J: usual care+instruction |

End-point of follow-up:

A: 6m B: 12w C: 8w D: 6m E: 12m F: 6m G: 3m H: 6m I: 12m J: 8w

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: I:not reported; C: not reported B: I:not reported; C: not reported C: I:not reported; C: not reported D: I:not reported; C: not reported E: I:not reported; C: not reported F: I:not reported; C: not reported G: I:not reported; C: not reported H: I:not reported; C: not reported I: I:not reported; C: not reported J: I:not reported; C: not reported

|

Outcome measure-1 Hospitalisation rate defined as number of rehospitalisations per person-year

Pooled rate ratio (95% CI): 0.64 (95% CI 0.44, 0.93) favoring PR

|

Facultative:

The results indicate that PR reduces the number of hospitalisations due to COPD exacerbations.

The study had some issues due to the fact that the included trails were not blinded, of small size, or did not adequately randomise or conceal allocation.

For hospitalisation rate: Very low GRADE, downgraded for inconsistency (interventions and effects), and high risk of bias (lack of blinding, no information on randomisation and concealment of allocation)

|

|

Burge, 2020

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to June 2019

A: De Roos, 2017 B: Egan, 2010 C: Holland, 2017 D: Tsai, 2016 E: Vasilopoulou, 2017 F: Wootton, 2017 Study design: RCT

Setting and country: A: primary physiotherapy care centres (The Netherlands) B: PR (UK) C: 2 hospital-based outpatient PR programmes (Australia) E: outpatient clinic (Greece) F: 5 sites, outpatient PR, 2 metropolitan cities (Australia)

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: A: Eight activity monitors were provided without charge by PAM. PAM had no involvement in the study. B-F: No conflicts of interest |

Inclusion criteria SR: RCTs comparing any intervention in patients with COPD (FEV1 <70% predicted) to control

Exclusion criteria SR: RCTs included patients with asthma

6 studies included,

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N, mean age A: 52; I:69, C:71 (I: 10, C: 9) B: 43; - (-) C: 166; I:69, C:69 (I: 13, C: 10) D: 36; I:73, C:75 (I: 8, C: 9) E: group b+c 100; I: 67, C:64 (I: 7, C: 8) F: 143; I:69, C: 68 (I: 8, C: 9)

Sex: A: I:31; C: 38 B: I:-; C: - C: I:60; C: 60 D: I:63; C: 35 E: I:76; C: 74 F: I:59; C: 58

Groups comparable at baseline? A: probably yes B: - C: probably yes D: probably yes E: probably yes F: probably yes |

Describe intervention:

A: 2 sessions a week, 1 hour aerobic+strength B: 7w, 2 sessions a week, 1 hour exercise, 1 hour education C: 12m 2 sessions a week, >30 minutes D: 8w 3 sessions a week telerehabiliation E: 8 weeks exercise training (HIIT) then 12 months maintenance (centre-based) F: 8w 3 sessions a week |

Describe control:

A: not described B: not described C: not described D: not described E: not described F: no exercise training |

End-point of follow-up:

A: 10w B: 7w C: 8w D: 8w E: 14m F: 8w

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: I:5; C: 2 B: I:not reported; C: not reported C: I:not reported; C: not reported D: I:not reported; C: not reported E: I:not reported; C: not reported F: I:not reported; C: not reported

|

Outcome measure-1

B: SGRQ total score MD: -11.4 (95% CI: -15.84 to -6.96) F: SGRQ total score MD: -6 (95% CI: -10.86 to -1.14)

Outcome measure-2

A: SGRQ dyspnoea score MD: 2.4 (95% CI: -0.93 to 5.73) D: SGRQ dyspnoea score MD: 3.2 (95% CI: -1.08 to 7.48) F: SGRQ dyspnoea score MD: 1 (95% CI: -1.17 to 3.17)

Pooled effect (random effects model: 1.69 (95% CI: 0.02 to 3.36) favoring PR Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-3

C: CRQ dyspnoea MD: 1,56 (95% CI: -0.29 to 3.41)

Outcome measure-4

A: 6-MWD MD: 39.1 (95% CI: 9.09 to 69.11) D: 6-MWD MD: 49 (95% CI: -12.03 to 110.03) F: 6-MWD MD: 24 (95% CI: 6.48 to 41.52)

Pooled effect (random effects model ): 29.06 (95% CI: 14.38 to 43.75) favoring PR Heterogeneity (I2): 0&

|

Facultative:

This review was aimed at investigating improvement in physical activity in patients with COPD after various interventions. Outcomes relevant to this guideline were secondary outcomes.

The included studies were not able to blind participants and caretakers towards the intervention. Moreover, studies were scarce and small.

For quality of life: Very low GRADE, downgraded for inconsistency (interventions and effects), imprecision, and high risk of bias (lack of blinding, no information on randomisation and concealment of allocation)

For dyspnoea: Very low GRADE, downgraded for inconsistency (interventions and effects), imprecision, and high risk of bias (lack of blinding, no information on randomisation and concealment of allocation) For walking distance: Very low GRADE, downgraded for inconsistency (interventions and effects), imprecision, and high risk of bias (lack of blinding, no information on randomisation and concealment of allocation)

There were too few studies to further investigate heterogeneity, both statistical and clinical. |

|

McCarthy, 2015

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to March 2014

A: Barakat, 2008 B: Baumann, 2012 C: Behnke, 2000 D: Bendstrup, 1997 E: Booker, 1984 F: Borghi-Silva, 2009 G: Boxall, 2005 H: Busch, 1988 I: Cambach, 1997 J: Casaburi, 2004 K: Casey, 2013 L: Cebollero, 2012 M: Chan, 2011 N: Chlumsy, 2001 O: Clark, 1996 P: Cochrane, 2006 Q: Cockroft, 1981 R: De Souto Araujo, 2012 S: Deering, 2011 T: Elci, 2008 U: Emery, 1998 V: Engström, 1999 W: Faager, 2004 X: Faulkner, 2010 Y: Fernandez, 2009 Z: Finnerty, 2001 AA: Gohl, 2006 AB: Goldstein, 1994 AC: Gomez, 2006 AD: Gosselink, 2000 AE: Gottlieb, 2011 AF: Griffiths, 2000 AG: Gurgun, 2013 AH: Güell, 1995 AI: Güell, 1998 AJ: Hernandez, 2000 AK: Hoff, 2007 AL: Jones, 1985 AM: Karapolat, 2007 AN: Lake, 1990 AO: Lindsay, 2005 AP: Liu, 2012 AQ: McGavin, 1977 AR: McNamara, 2013 AS: Mehri, 2007 AT: Mendes De Oliveira, 2010 AU: Nalbant, 2011 AV: O'Shea, 2007 AW: Ozdemir, 2010 AX: Paz-Diaz, 2007 AY: Petty, 2006 AZ: Reardon, 1994 BA: Ringbaek, 2000 BB: Simpson, 1992 BC: Singh, 2003 BD: Sridhar, 2008 BE: Strijbos, 1996 BF: Theander, 2009 BG: Vallet, 1994 BH: Van Wetering, 2010 BI: Vijayan, 2010 BJ: Weiner, 1992 BK: Wen, 2008 BL: Wijkstra, 1994 BM: Xie, 2003

All studies were RCTs

Setting and country: A: Outpatients (OP) France B: OP Germany C: Hospital Germany D: OP Danmark E: Home based (H) UK F: OP Brazil G: H Australia H: H Canada I: Community based (CB) The Netherlands J: OP USA K: CB Ireland L: OP Spain M: OP Hong Kong N: OP O: HB Scotland P: OP UK Q: Inpatient (IP) R: Brazil S: OP Ireland T: combined OP/H Turkey U: OP V: OP/HB Sweden W: IP Sweden X: CB UK Y: HB Spain Z: OP UK AA: OP Germany AB: IP/OP Canada AC: CB Spain AD: OP Belgium AE: CB Denmark AF: OP/HB UK AG: OP Turkey AH: OP/HB Spain AI: OP Spain AJ: HB Spain AK: Norway AL: HB New Zealand AM: OP Turkey AN: OP Australia AO: CB Hong Kong AP: HB/OP/IP Hong Kong AQ: HB India AR: OP Australia AS: OP Iran AT: OP or HB Brazil AU: nursing home Turkey AV: OP/HB Australia AW: OP Turkey AX: OP Venezuela AY: HB USA AZ: OP USA BA: OP Denmark BB: OP BC: HB India BD: OP-HB UK BE: OP BF: OP Sweden BG: IP France BH: CB Netherlands BI: India BJ: OP Israel BK: OP China BL: HB BM: H China

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: No studies reported conflicts of interest

|

Inclusion criteria SR: RCTs comparing any intervention in >90% patients with COPD (FEV1 <70% predicted) to control

Exclusion criteria SR: RCTs on patients with a recent exacerbation or patients who were mechanically ventilated

65 studies included,

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N, mean age, SD A: 80; I: 63.7, C: 65.9 (not reported) B: 100; I: 65, C: 63 (not reported) C: 46; I: 64.0, C: 68.0 (I: 1.9, C: 2.2) D: 42; I: 64, C: 65 (I: 3, C:2) E: 69; I: 66 C: 65 (I 8 C 7) F: 40; I 67 C 67 (I 10 C 10) G: 60; I 77.6 C 75.8 (I 7.6 C 8.1) H: 14; I 65 C 66 (I 16 C 16) I: 99; I 62 C 62 (I 5 C 9) J: 26; I 69 C 68 (I 10 C 9) K: 350; I 68.8 C 68.4 (I 10.2 C 10.3) L: 36; I 68 C 69 (I 7.6 C 8.1) M: 206; I 73.6 C 73.6 (I 7.5 C 7.4) N: 19; I 63 C 35 (I 11 C 13) O: 48; I 58 C 55 (I 8 C 8) P: 256; 68.9 (7.3) Q: 39; I 61 C 60 (I 5 C 5) R: 32; I1 56.9 I2 62.4 C 71.1 (not reported) S: 60; I 67.7 C 68.6 (I 5.3 C 5.5) T: 78; I 59.7 C 58.1 (I 8.6 C 11.5) U: 79; I 65 C 67 (I 6 C 7) V: 55; I 66 C 67 (I 5 C 5) W: 20; I 72 C 70 (I 9 C 8) X: 20; not reported (not reported) Y: 50; I 66 C 70 (I 8 C 5) Z: 100; I 70.4 C 68.4 (I 8.0 C 10.4) AA: 34; I 62.5 C 63.2 (I 7 C 8.5) AB: 89; I 66 C 65 (I 7 C 8) AC: 97; I1 64.1 I2 64.9 C 63.4 (not reported) AD: 100; I 60 C 63 (I 9 C 7) AE: 61; I 74.1 c 73.2 (not reported) AF: 200; I 68.2 C 68.3 (I 8.2 C 8.1) AG: 46; I1 64.0 I2 66.8 C 67.8 (I1 10.8 I2 9.6 C 6.6) AH: 60; I 66 C 65 (I 7 C 6) AI: 40; I 68 C 66 (I 8 C 8) AJ: 60; I 64.3 C 63.1 (I 8.3 C 6.9) AK: 12; I 62.8 C 60.6 (I 1.4 C 3.0) AL: 30; I 63.8 C 62.7 (I6.1 C 8.4) AM: 54; I 64.8 C 67.2 (I 9.4 C 6.7) AN: 28; I 66.3 C 65.7 (I 6.8 C 3.5) AO: 50; I 69.5 C 69.8 (I 9.3 C 10.3) AP: 72; I 61.3 C 62.2 (I 8.3 C 6.3) AQ: 28; I 61.4 C 57.2 (I 5.6 C 7.9) AR: 53; I1 72 I2 73 C 70 (I1 10 I2 7 C 9) AS: 38; I 52.1 C 52.2 (I 10.7 C 11.6) AT: 117; I 71.3 C 70.8 (not reported) AU: 29; I 73.5 C 68 (not reported) AV: 54; I 66.9 C 68.4 (I 7 C 9.9) AW: 50; I 60.9 C 64.1 (I 8.8 C 8.9) AX: 24; I 67 C 62 (I 5 C 7) AY: 214; I 68 C 67 (I 9 C 10) AZ: 20; I 66.3 C 66.1 (not reported) BA: 45; I 61.8 C 64.6 (I 6.8 C 7.7) BB: 34; I 72 C 70 (I 4.8 C 5.7) BC: 40; 59.3 (6.4) BD: 122; I 69.9 C 69.7 (I 9.6 C 10.4) BE: 32; I 61 C 63 (I 6 C 5) BF: 30; I 66 C 64 (not reported) BG: 22; I 59.6 C 58.2 (I 2.75 C 1.8) BH: 199; I 65.9 C 67.2 (I 8.8 C 8.9) BI: 31; not reported (not reported) BJ: 24; I 64.4 C 62.3 (I 3 C 2.4) BK: 41; I 67.5 C 66 (I 7 C 10) BL: 45; I 64 C 62 (I 5 C 5) BM: 50; I 54 C 54 (I 6 C 6)

Sex (% men): A: I:84 (overall); C: B: I:58 (overall); C: C: I:80; C: 73 D: I:44; C: 44 E: I:not reported; C: F: I:65; C: 60 G: I:48; C: 65 H: I:71; C: 86 I: I:88; C: 75 J: I:100; C: 100 K: I:66; C: 62 L: I:100; C: 100 M: I:88; C: 87 N: I:92; C: 83 O: I:not reported; C: P: I:44.1 (overall); C: Q: I:100; C: 100 R: I:I1 62 I2 50; C: 73 S: I:44; C: 63 T: I:85; C: 85 U: I:50; C: 48 V: I:54; C: 50 W: I:30; C: 30 X: I:not reported; C: not reported Y: I:98 overall; C: Z: I:69; C: 66 AA: I:60; C: 78 AB: I:55; C: 43 AC: I:81; C: 83 AD: I:84; C: 91 AE: I:32; C: 35 AF: I:61; C: 59 AG: I:I1 86 I2 100; C: 100 AH: I:100; C: 100 AI: I:89; C: 100 AJ: I:100; C: 100 AK: I:67; C: 67 AL: I:67; C: 20 AM: I:81; C: 95 AN: I:86; C: 57 AO: I:80; C: 72 AP: I:72; C: 80 AQ: I:100; C: 100 AR: I:39; C: 47 AS: I:55; C: 39 AT: I:82; C: 66 AU: I:79; C: 87 AV: I:not reported; C: AW: I:100; C: 100 AX: I:60; C: 86 AY: I:57; C: 55 AZ: I:50; C: 50 BA: I:4; C: 29 BB: I:36; C: 71 BC: I:overall 80; C: BD: I:49; C: 49 BE: I:93; C: 80 BF: I:25; C: 71 BG: I:70; C: 80 BH: I:71; C: 71 BI: I:not reported; C: not reported BJ: I:50; C: 42 BK: I:overall 98; C: - BL: I:82; C: 93 BM: I:88; C: 84

Groups comparable? A: probably yes B: probably yes C: probably yes D: probably yes E: unclear F: probably yes G: probably no H: probably yes I: probably yes J: probably yes K: probably yes L: probably yes M: probably yes N: probably yes O: probably yes P: unclear Q: probably no R: probably no S: probably yes T: probably yes U: probably yes V: probably yes W: probably yes X: unclear Y: probably yes Z: probably yes AA: probably yes AB: probably yes AC: probably yes AD: probably yes AE: probably yes AF: probably yes AG: probably yes AH: probably no AI: probably no AJ: probably yes AK: probably no AL: probably no AM: probably yes AN: probably no AO: probably yes AP: probably yes AQ: probably no AR: probably yes AS: probably yes AT: probably no AU: probably yes AV: probably yes AW: probably yes AX: probably no AY: probably yes AZ: probably yes BA: probably no BB: probably no BC: probably yes BD: probably no BE: probably yes BF: probably no BG: probably yes BH: probably yes BI: unclear BJ: probably no BK: probably yes BL: probably yes BM: probably yes |

Intervention: A: upper (U), lower limb exercise (L), education B: Aerobic exercise, upper, lower limb exercise, education, peer support C: EXACERBATION D: U+L+Respiratory exercise (R ) E: lower limb exercise, breathing, PD, education, phychological intervention F: U+L+aerob G: U+L+edu H: L+breathing I: U+L+edu+IMT J: L+nutrition K: 8w L+U+arobic exercise, education, phone support, resp muscle training L: 12w resistance or endurance+resistance training M: 3m U+L+Respiratory muscle rehabilitation (R) N: 8w L+breathing O: 12w U+L P: 6w U+L+aerobic+cognitive behavioural self-management Q: 6w U+L R: 8w low-intensity water and floor exercises S: 7w U+L+resp+aerobic+education T: 3m U+L+aerobic+ edu U: 10w U+L+education+psychologic intervention V: 1y L+U+education+IMT W: 8w U+L+aerobic+education X: 8w U+L+aerobic+education Y: 2x instruction on U+L+aerobic+education+physio visits Z: 6w U+L+edu AA: 12m U+L+aerobic AB: 6m U+L+breathing+aerobic+education+psychologic intervention AC: 3m U+L+aerobic+ edu, 12 month maintenance (subgroup) AD: 24w U+L AE: 7w U+L+resp+aerobic+education AF: 6w U+L+education+psychologic intervention, NS, SmC AG: 8w U+L+aerobic+education (+nutritional support: I2) AH: 6m L+breathing+PD AI: 8w LLE+IMT AJ: 12w LLE AK: 8w LLE AL: 10w L+U AM: 8w U+L+aerobic+breathing exercise+education AN: 8w L/U/L+U AO: 6w U+L+aerobic+educational+physiotherapy+psychoeducation AP: 6m U+L+aerobic+peer support AQ: L duration not predetermined AR: 8w U+L+aerobic AS: 4w U+L+aerobic AT: 12w U+L+aerobic+education AU: 6m U+L+aerobic+education AV: 12w U+L AW: 4w water based U+L+aerobic AX: 8w U+L+aerobic AY: 8w U+L+aerobic+education+physiotherapy instructed by tailored or standard videotape AZ: 6w L+U+breathing+education+psychologic BA: 8w L+U+breathing+education+nutritional BB: 8w L+U BC: 4w L+IMT BD: EXACERBATION BE: 12w L+breathing+PD+education+pchychologic intervention BF: 12w U+L+aerobic+education+breathing+nutrition BG: 8w L+breathing BH: 4m U+L+aerobic+education; 20m active maintenance BI: 8w U+L+aerobic BJ: 6m L+U+IMT+breathing BK: 12w L+aerobic BL: 12w L+U+IMT+breathing+education+psychologic+nurse home visit BM: 12w L |

Control: A: not described B: referral back to pulmonologist C: D: usual care E: not described F: usual care G: usual care H: usual care I: medication management only J: usual care and placebo injections K: routine GP care L: usual care M: usual care N: usual care O: usual care P: standard care Q: usual care R: usual care S: usual care T: usual care U: asked not to alter activities during study V: usual care W: usual care X: usual care Y: usual care Z: usual care AA: no therapy AB: usual care AC: usual care AD: usual care AE: usual care AF: usual care AG: usual care AH: usual care AI: usual care AJ: usual care with biweekly clinical checkup AK: usual care AL: placebo respiratory device and usual care AM: usual care AN: usual care AO: tiotropium AP: health education and exercise advice AQ: usual care AR: usual care, asked not to alter physical activity AS: no exercise training AT: no exercise training AU: usual care AV: usual care AW: only medical therapy AX: optimal care as suggested by ATC AY: usual care AZ: usual care BA: conventional community care BB: initial testing and usual care BC: continue normal activities BD: BE: usual care BF: no care from multidisciplinary professionals BG: usual care BH: usual care BI: medication adjusted for 8w BJ: usual care BK: usual care BL: usual care BM: usual care |

End-point of follow-up:

A: 14w B: 8 sessions of 20 minutes and 18 sessions of 60 minutes C: D: 12w E: 9w F: 6w G: 12w H: 18w I: 12w J: 10w K: 12w L: 12w M: 3m N: 8w O: 12w P: 12m Q: 4m R: 8w S: 3m T: 3m U: 10w V: 12m W: 8w X: 9w Y: 1y Z: 24w AA: 12m AB: 24w AC: 12m AD: 18m AE: 6m AF: 1y AG: 8w AH: 24m AI: 8w AJ: 12w AK: 8w AL: 10w AM: 12w AN: 8w AO: 3m AP: 6m AQ: 19w AR: 8w AS: 4w AT: 12w AU: 6m AV: 6m AW: 1m AX: 8w AY: 8w AZ: 6w BA: 8w BB: 8w BC: 4w BD: BE: 18m BF: 12w BG: 2m BH: 4m BI: 8w? BJ: 6m BK: 12w BL: 12w BM: 12w

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: I:overall 9; C: B: I:13; C: 6 C: I:; C: D: I:5; C: 5 E: I:-; C: - F: I:-; C: - G: I:7; C: 7 H: I:1; C: 1 I: I:overall 76; C: J: I:1; C: 1 K: I:73 overall; C: L: I:unclear; C: M: I:48 overall; C: N: I:not reported; C: O: I:not reported; C: P: I:unclear, high proportion not completed; C: Q: I:5 overall; C: R: I:-; C: - S: I:19/44 overall; C: T: I:not reported; C: U: I:overall 6; C: V: I:overall 5; C: W: I:; C: X: I:overall 6; C: Y: I:overall 9; C: Z: I:overall 45; C: AA: I:overall 15; C: AB: I:overall 11; C: AC: I:overall 47; C: AD: I:overall 38; C: AE: I:overall 19; C: AF: I:overall 20; C: AG: I:-; C: - AH: I:overall 4; C: AI: I:overall 5; C: AJ: I:overall 23; C: AK: I:-; C: - AL: I:overall 5; C: AM: I:overall 4; C: AN: I:overall 2; C: AO: I:overall 9; C: AP: I:overall 4; C: AQ: I:overall 4; C: AR: I:overall 8; C: AS: I:-; C: - AT: I:overall 32; C: AU: I:overall 8; C: AV: I:overall 10; C: AW: I:-; C: - AX: I:-; C: - AY: I:overall 40; C: AZ: I:-; C: - BA: I:overall 9; C: BB: I:overall 6; C: BC: I:-; C: - BD: I:; C: BE: I:overall 5; C: BF: I:overall 4; C: BG: I:overall 2; C: BH: I:15; C: 9 BI: I:-; C: - BJ: I:-; C: - BK: I:overall 13; C: BL: I:overall 2; C: BM: I:not reported; C: |

Outcome measure 1: SGRQ B: SGRQ total score MD -6 (95% CI: -10.16 to -1.84) G: SGRQ total score MD -4.4 (95% CI: -11.67 to 2.87) M: SGRQ total score MD -0.6 (95% CI: -5.8 to 4.6) N: SGRQ total score MD 0.15 (95% CI: -18.6 to 18.9) R: SGRQ total score MD -17.94 (95% CI: ) S: SGRQ total score MD -10.03 (95% CI: -17.27 to 2.79) T: SGRQ total score MD -18.2 (95% CI: -24.76 to -11.64) V: SGRQ total score MD -0.2 (95% CI: -9.49 to 9.09) Y: SGRQ total score MD -12.2 (95% CI: -20.65 to -3.75) Z: SGRQ total score MD -7.1 (95% CI: -14.74 to 0.54) AA: SGRQ total score MD -9.3 (95% CI: -31.34 to 12.74) AE: SGRQ total score MD -5.62 (95% CI: -14.15 to 2.91) AF: SGRQ total score MD -8.4 (95% CI: -12.36 to -4.44) AG: SGRQ total score MD -6.27 (95% CI: -9.18 to -3.36) AM: SGRQ total score MD -13.1 (95% CI: -22.83 to -3.37) AX: SGRQ total score MD -10 (95% CI: -21.21 to 1.21) BA: SGRQ total score MD 0.1 (95% CI: -11.73 to 11.93) BF: SGRQ total score MD 5 (95% CI: -3.84 to 13.84) BH: SGRQ total score MD -4.2 (95% CI: -7.11 to -1.29)

Outcome measure 2: SGRQ dyspnoea score B: SGRQ dysnoea MD 3 (95% CI: -5.22 to 11.22) G: SGRQ dysnoea MD 2.6 (95% CI: -8.44 to 13.64) M: SGRQ dysnoea MD -5.7 (95% CI: -12.15 to 0.75) N: SGRQ dysnoea MD 0.82 (95% CI: -28.73 to 30.37) R: SGRQ dysnoea MD -11.71 (95% CI: -22.32 to -1.1) S: SGRQ dysnoea MD -0.78 (95% CI: -13.54 to 11.98) T: SGRQ dysnoea MD -5.98 (95% CI: -13.33 to 1.37) V: SGRQ dysnoea MD -3.4 (95% CI: -16.29 to 9.49) Y: SGRQ dysnoea MD -13.7 (95% CI: -25.59 to -1.81) Z: SGRQ dysnoea MD -14.8 (95% CI: -24.85 to -4.75) AA: SGRQ dysnoea MD -4 (95% CI: -35.02 to 27.02) AE: SGRQ dysnoea MD 0.49 (95% CI: -11.54 to 12.52) AF: SGRQ dysnoea MD -4.6 (95% CI: -10.55 to 1.35) AG: SGRQ dysnoea MD -10.91 (95% CI: -16.23 to -5.59) AM: SGRQ dysnoea MD -8.1 (95% CI: -20.85 to 4.65) AX: SGRQ dysnoea MD -10 (95% CI: -23.22 to 3.22) BA: SGRQ dysnoea MD -0.4 (95% CI: -15.72 to 14.92) BF: SGRQ dysnoea MD 11.1 (95% CI: -8.77 to 30.97) BH: SGRQ dysnoea MD -1.6 (95% CI: -6.73 to 3.53)

Outcome measure 3: 6-minute walking distance: B: 6-MWD MD 59 (95% CI: 32.25 to 85.75) E: 6-MWD MD 16 (95% CI: -25.33 to 57.33) F: 6-MWD MD 93 (95% CI: 27.87 to 158.13) G: 6-MWD MD 34.8 (95% CI: -7.05 to 76.65) I: 6-MWD MD 59 (95% CI: -72.21 to 82.21) L: 6-MWD MD 36.05 (95% CI: 12.33 to 59.77) M: 6-MWD MD 0.58 (95% CI: -26 to 27.16) N: 6-MWD MD 59.74 (95% CI: -62.56 to 182.04) R: 6-MWD MD 71.66 (95% CI: -20.01 to 163.33) S: 6-MWD MD 13.71 (95% CI: 29.77 to 57.19) T: 6-MWD MD 23.38 (95% CI: 0.81 to 45.95 ) V: 6-MWD MD 40 (95% CI: -13.5 to 93.5) W: 6-MWD MD 50 (95% CI: -83.05 to 183.05) Y: 6-MWD MD 66 (95% CI: 11.36 to 120.64) Z: 6-MWD MD 67 (95% CI: -1.59 to 135.59) AA: 6-MWD MD 75.4 (95% CI: 6.38 to 144.42) AB: 6-MWD MD 43 (95% CI: -2.04 to 88.04) AC: 6-MWD MD -16.07 (95% CI: -41.65 to 9.52) AD: 6-MWD MD 55 (95% CI: -2 to 112) AE: 6-MWD MD 45.58 (95% CI: -8.05 to99.21) AG: 6-MWD MD 73.25 (95% CI: 51.33 to 95.17 ) AH: 6-MWD MD 83 (95% CI: 47.88 to 118.12) AI: 6-MWD MD 85 (95% CI: 30.43 to139.57) AM: 6-MWD MD 106.5 (95% CI: 74.23 to 138.77) AN: 6-MWD MD 143.6 (95% CI: 74.34 to 212.86) AP: 6-MWD MD 31.55 (95% CI: 20.38 to 42.72) AR: 6-MWD MD 61.5 (95% CI: 41.35 to 81.65) AT: 6-MWD MD 91.58 (95% CI: 65.14 to 118.02) AV: 6-MWD MD -5 (95% CI: -24.92 to 14.92) AW: 6-MWD MD 45.3 (95% CI: -3.33 to 93.93) BA: 6-MWD MD 28.99 (95% CI: -24.4 to 82.38) BB: 6-MWD MD 29 (95% CI: -53.5 to 111.5) BC: 6-MWD MD 47.7 (95% CI: -38.37 to 113.77) BF: 6-MWD MD 24.1 (95% CI: -4.4 to 52.6) BH: 6-MWD MD 13.9 (95% CI: 3.09 to 24.71) BI: 6-MWD MD 57.42 (95% CI: 6.48. to 108.36) BL: 6-MWD MD 37 (95% CI: -41.29 to 115.29)

Outcome measure 4: CRQ dyspnoea score

I: CRQ dyspnoea MD 1.2 (95% CI: 0.36 to 2.04) K: CRQ dyspnoea MD 0.28 (95% CI: -0.02 to 0.58) L: CRQ dyspnoea MD 0.8 (95% CI: 0.17 to 1.43) X: CRQ dyspnoea MD -0.2 (95% CI: -1.14 to 0.74) AB: CRQ dyspnoea MD 0.66 (95% CI: 0.12 to 1.2) AC: CRQ dyspnoea MD 0.52 (95% CI: 0.07 to 0.97) AD: CRQ dyspnoea MD 0.82 (95% CI: 0.17 to 1.47) AF: CRQ dyspnoea MD 1.18 (95% CI: 0.85 to 1.51) AH: CRQ dyspnoea MD 1.3 (95% CI: 0.64 to 1.96) AI: CRQ dyspnoea MD 1 (95% CI: 0.2 to 1.8) AJ: CRQ dyspnoea MD 0.78 (95% CI: 0.02 to 1.54) AO: CRQ dyspnoea MD 0.06 (95% CI: -0.74 to 0.86) AR: CRQ dyspnoea MD 2.15 (95% CI: 0.52 to 3.78) AV: CRQ dyspnoea MD 0.66 (95% CI: -0.08 to 1.28) BB: CRQ dyspnoea MD 1.2 (95% CI: 0.37 to 2.03) BC: CRQ dyspnoea MD 0.88 (95% CI: 0.35 to 1.41) BL: CRQ dyspnoea MD 0.9 (95% CI: 0.13 to 1.67)

|

Extensive and well-performed SR with a many relevant studies included. However a plethora of (combinations of) interventions, patients and treatment durations was investigated, leading to a large heterogeneity in results and quality of evidence. This may hamper the sequence of evidence to decision-making.

For QoL: Low GRADE, downgraded one level due to risk of bias and one level due to heterogeneity.

For symptom score: Low GRADE, downgraded one level due to risk of bias and one level due to heterogeneity.

For 6-MWD: Very Low GRADE, downgraded two levels due to very high risk of bias, and one level due to heterogeneity. |

Risk of bias tables

Tweede- en derdelijnsrevalidatie bij COPD

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/not applicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Salman, 2003 |

Yes |

yes |

no |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

unclear |

No |

|

Moore, 2016 |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Unclear |

Yes |

no |

|

Burge, 2020 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 31-08-2023

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2020 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met COPD.

Samenstelling van de werkgroep

Werkgroep

- Dr. F. (Folkert) Brijker, longarts, werkzaam in het Spaarne Gasthuis te Haarlem, NVALT (voorzitter, vanaf oktober 2022)

- Dr. J.S. (Jaring) van der Zee, longarts, NVALT (voorzitter, tot oktober 2022)

- Dr. W.H. (Wouter) van Geffen, longarts, werkzaam in het Medisch Centrum Leeuwarden te Leeuwarden, NVALT

- Drs. R. (Renée) van Snippenburg, werkzaam bij Ksyos en waarnemend longarts, NVALT

- Dr. J.C.C.M. (Hans) in ’t Veen, longarts, werkzaam in het Franciscus Gasthuis & Vlietland te Rotterdam, NVALT

- M. (Moniek) Wouters, longarts, werkzaam in het Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei te Arnhem, NVALT

- Prof. H.A.M. (Huib) Kerstjens, hoogleraar longziekten, longarts, werkzaam in het UMCG te Groningen, NVALT (vanaf oktober 2022)

- J. (Jeanine) Antons, longarts, werkzaam in het RadboudUMC te Nijmegen, NVALT (vanaf oktober 2022)

- Drs C.L.Y. (Chantal) Knoops, AIOS longgeneeskunde, werkzaam in het Catharina Ziekenhuis te Eindhoven (vanaf oktober 2022)

- Prof. J.W.M. (Jean) Muris, huisarts, werkzaam bij de Universiteit Maastricht, lid van de NHG-Expertgroep CAHAG, NHG

- Drs. E.R. (Erik) van der Meijs, apotheker, KNMP

- W.J.M. (Walter) van Litsenburg, verpleegkundig specialist longgeneeskunde, Catharina Ziekenhuis te Eindhoven, V&VN

- Dr. M.J.H. (Maurice) Sillen, fysiotherapeut, werkzaam bij CIRO, KNGF

- R.A. (Renée) Kool, projectleider, Longfonds

- R. (Ramona) Leysner, diëtiste, Nederlandse Vereniging van Diëtisten (NVD)

- Drs. M. (Menno) Wagenaar, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, Longfonds

- J. (Johan) Smit, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, Longfonds

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. M. (Margriet) Moret, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. N. (Nicole) Verheijen, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en longarts

- Dr. T. (Tim) Christen, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Brijker (voorzitter, vanaf oktober 2022) |

Longarts Spaarne Gasthuis |

Voorzitter sectie COPD NVALT. Dit is een onbetaalde functie binnen de longartsenvereniging NVALT. Lid regionale kwaliteitscommissie COPD/astma. Deze Commissie heeft 2x per jaar vergadering a 2 uur per keer in de avonduren en hiervoor ontvang ik onkostenvergoeding. Docent CASPIR cursussen. dit betreft scholing voor spirometrie voor huisartsen en POH-ers in de regio. Dit vindt een aantal keer per jaar plaats (<5 keer) in de avonduren en hiervoor ontvang ik een onkostenvergoeding |

Geen |

Geen |

|

*Van der Zee (voorzitter, tot oktober 2022) |

Longarts OLVG Amsterdam 0,2FTE tot 1-1-2020 Longarts Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC, 0,2 FTE |

Lid MEC-U Locatie Nieuwegein, onkosten vergoeding Lid Gezondheidsraad Commissie Gespoten PUR, onkosten vergoeding Incidenteel medische expertises (o.a. DAS, ARAG, Triage, de Rechtspraak), betaald 2019 Speakers fee, Astra-Zeneca, Novartis, Chiesi 2019 1x Ad hoc Advies m.b.t. biologicals bij astma, GSK, betaald |

Geen |

Geen advieswerk tijdens het richtlijnontwikkeltraject |

|

Van Geffen |

Longarts Medisch Centrum Leeuwarden, maatschap Friese Longartsen |

Editorial board Cochrane Airways: Onbetaald Commisie Bronkhorst Nvalt: Onbetaald Richtlijn Commissie NVALT NSCLC: Onbetaald |

Deelname aan een investigator initiated onderzoek firma Novartis. financiering is overgemaakt aan UMCG (2017 beëindigd). Voor de bedrijven Chiesi, Roche, Boehringer en AstraZeneca deelname aan adviesraden betreffende oncologie. Deze gingen niet over COPD of biologicals. De hiervoor gebruikelijke CGR vergoeding werd geweigerd. Chiesi en Boehringer waren wel COPD, maar niet in de laatste 1.5 jaar. |

Geen advieswerk op gebied van COPD of biologicals tijdens het richtlijnontwikkeltraject |

|

In 't Veen |

Longarts bij In 't Veen Longarts BV. Verbonden aan de vakgroep longziekten en STZ expertisecentrum Astma, COPD & Respiratoire Allergie van het Franciscus Gasthuis en Vlietland, Rotterdam. |

Onbetaald: Opleider longziekten Franciscus Gasthuis en Vlietland Lid Concilium Opleiding NVALT Lid Vrij Ademen Akkoord namens NVALT Betrokken longarts bij Schone Lucht Akkoord Lid Move2Improve Lid werkgroep Ziektelastmeter; Generiek en COPD (afgerond) Voorzitter StichtingRoLeX (Rotterdam Leeuwarden eXpertise voor obstructieve longzieken), een stichting die nascholing voor longartsen (i.o.) verzorgd. Bestuurslid LAN Betaald: Longfunctiebeoordelaar Huisartsenlaboratorium STAR-SHL NHG richtlijn COPD namens NVALT Adviseurschap m.b.t. astma: Sanofi, GSK, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi. (laatste 2 jaar (datum invullen 30-6-19) geen persoonlijke betrokkenhied als adviseur bij COPD gerelateerde issues, mede vanwege mijn betrokkenheid bij de NHG richtlijn). Speakers Bureau: Chiesie, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Inhalatie Technologie Werkgroep Health Agency Stichting RoLeX Sanofi |

Ik beoordeel longfuncties voor een huisarts laboratorium, en heb adviseurschap verricht voor diverse farmaceutische firma's. Er is nooit advies gegeven door mij over medicamenteuze COPD-behandeling, ook niet over biologicals. het genoemde adviseurschap is inmiddels meer dan 3-4 jaar geleden beëindigd. Zie eerder. Research faculty grants, (subsidiegevers Boehringer, Chiesi, Teva, Franciscus wetenschapsbureau) m.b.t. onderzoek bij astma en COPD, via ons expertisecentrum. Van belang hierbij is dat al het onderzoek niet medicatie-gerelateerd is. Zie boven bij onbetaald: Ik ben betrokken bij de bevordering van luchtkwaliteit en als zodanig word ik af en toe geconsulteerd met betrekking tot het schone Lucht Akkoord, een nationaal (door de overheid in gang gezet) platform dat maatregelen hierover in kaart brengt. Voorts ben ik betrokken bij het Vrij Ademen Akkoord, dat oa vanuit LAN, Longfonds, NRS en NVALT aandacht vraagt voor de (toekomstige) patient met een longziekte. |

Geen advieswerk over COPD of biologicals tijdens ontwikkeltraject van de richtlijn. Geen uitwerking van uitgangsvragen over longmedicatie of biologicals. |

|

Van Snippenburg |

Waarnemend Longarts; |

Secretaris Sectie COPD NVALT, onbetaald Werkgroep longen Huisartsen Utrecht Stad, betaald

|

Geen |

Geen |

|

Antons (vanaf oktober 2022) |

Longarts Radboudumc, Nijmegen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Kerstjens (vanaf oktober 2022) |

Hoogleraar longziekten UMCG, 1,0 FTE |

"Voorzitter Noordelijke CARA Stichting. Subsidiegevend orgaan. Onbetaald - Lid RvT bureau bijwerkingen geneesmiddelen LAREB. Betaald aan UMCG - Vz Stichting BEBO. Onafhankelijke METc. Betaald aan UMCG (per 1-1-2023 vz) - Vice-vz Netherlands Respiratory Society. Stichting ter bevordering van wetenschap en wetenschapsklimaat Longziekten NL. Onbetaald. (per 1-1-2023 vz).

Op afroep (geen vaste contracten of afspraken) deelname aan adviesraden van farmaceutische industrieën, en betaling voor lezingen: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, Novartis. Alles betaald aan UMCG." |

"Geen persoonlijk financieel belang; alles wat er door mij binnenkomt wordt betaald aan UMCG. En krijg ik ook in tweede instantie nooit wat van. 2. Geen dienstverband 3. Betaald adviseurschappen zie bij overige item over nevenwerkzaamheden voor AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, Novartis. 4. Geen directe fianicee belangen of via aandelen of opties. 5. Geen patenten"

"Veel gesponsord onderzoek, o.a. ZonMW VWS Innovatiefonds verzekeraars Industrie: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, Novartis." |

restricties ten aanzien van besluitvorming met betrekking tot modules over medicatie |

|

Knoops (vanaf oktober 2022) |

AIOS longziekten, Catharina Ziekenhuis Eindhoven |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Tazmi (tot oktober 2020) |

Verpleegkundig specialist - werkzaam bij Laurens locatie Intermezzo |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Van Jaarsveld |

Adviseur Zorg bij Longfonds |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Muris |

Hoogleraar huisartsgeneeskunde, Universiteit Maastricht |

Vervangende werkzaamheden huisartspraktijk Geulle (betaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Van der Meijs |

Apotheker, sinds 1 februari niet meer praktiserend lid namens de KNMP |

SIG-long (SIG = specialist interest group) van KNMP – vacatiegeld |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Van Litsenburg (vanaf oktober 2020) |

Verpleegkundig specialist astma en COPD 36 uur per week 24-uurs thuiszorgverpleegkundige 24 uur per week |

Bestuurslid IMIS (inhalatiemedicatie instructie school) 2u per week Coördinator IMIS Zuid Nederland IMIS trainer Docent Hogeschool Arnhem en Nijmegen Kernteam Picasso voor COPD (momenteel niet actief) Werkgroeplid palliatieve richtlijn COPD |

Kernteamlid Picasso (niet actief) |

Geen |

|

Leysner |

dietist Merem medische revalidatie in Hilversum" |

Incidenteel scholing geven aan studenten hogeschool Holland; betaald |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Wouters |

Bij aanvang AIOS longziekten, Rijnstate Ziekenhuis en thans longarts Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei Ede |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Wagenaar |

Longervaringsdeskundige bij het Longfonds Geen betaalde functies |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Kool |

Projectleider Zorgveld, Longfonds |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Sillen |

Resultaatverantwoordelijk fysiotherapeut CIRO+, expertisecentrum voor chronisch orgaanfalen Horn |

Bestuurslid Vereniging voor Hart-, Vaat- en Longfysiotherapie (vacatievergoeding) Extern adviseur Fontys Hogeschool Eindhoven (betaald) Gastdocent Saxion Hogeschool, Enschede en Hogeschool van Amsterdam (betaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Smit |

Longervaringsdeskundige Longfonds (vrijwilligerswerk) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Implementatie