Postoperatief beleid

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is het advies postoperatief ten aanzien van belastbaarheid van de nek voor patiënten met CRS?

Aanbeveling

Preoperatief

Maak de patiënt voor de operatie bewust van realistische verwachtingen ten aanzien van werkhervatting en eventuele tijdelijke restricties (denk bijvoorbeeld aan autorijden, intensiteit van werk, sport).

Postoperatief

Adviseer de patiënt om activiteiten van het dagelijks leven weer op te pakken, zonder al te veel restricties, op geleide van de pijn.

Leg tijdens het herstel focus op de mogelijk ontstane beperkingen van de nek en/of arm. Overweeg actieve gerichte oefentherapie (geen massage).

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Het doel van deze module was om te achterhalen wat het optimale postoperatieve beleid is ten aanzien van belastbaarheid van de nek voor patiënten met CRS. De module is opgedeeld in twee subvragen. In deel 1 is gekeken naar de effectiviteit van het geven van advies om de fysieke belastbaarheid te beperken op korte termijn (binnen 6 weken postoperatief). Dit is op twee manieren onderzocht: beperking door het dragen van een nekkraag met restricties ten aanzien van activiteiten (1 studie; Abbott, 2013) en beperking door het niet doen van oefentherapie (2 studies: Coronado, 2020; McFarland, 2020). Er lijkt geen voordeel te zijn voor de kwaliteit van leven bij het ontvangen van advies voor restricties in activiteit in vergelijking met geen advies tot activiteit restricties in de eerste 6 weken na operatie, bij patiënten die geopereerd zijn voor CRS. De bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat kwaliteit van leven is zeer laag, omdat dit op slechts enkele kleine studies is gebaseerd met risico op bias. De cruciale uitkomstmaat ‘global perceived effect’ wordt niet gerapporteerd.

In deel 2 is gekeken naar de effectiviteit van het geven van advies om de fysieke belastbaarheid te beperken op de lange termijn (vanaf 6 weken postoperatief). Er is één studie gevonden. Intensieve revalidatie met fysieke en mentale begeleiding na een initiële postoperatieve fase van 6 weken heeft geen klinisch relevant effect op de kwaliteit van leven, pijnuitkomsten of functioneren. De gevonden bewijskracht is hiervoor zeer laag, volgend uit indirect bewijs met risico op bias. Samenvattend is de bewijskracht voor de kritieke uitkomstmaten zeer laag. Dit betekent dat andere studies kunnen leiden tot nieuwe inzichten.

Uit de literatuur blijkt dat er geen direct antwoord is te geven op de uitgangsvraag. De werkgroep adviseert (op basis van expert opinie en praktijkervaring) om werk en sport geleidelijk hervatten met uiteindelijk doel de patiënt geen beperkingen op te leggen.

Om dit advies indirect te toetsen, is de vraag onderzocht of restricties van activiteiten of extra oefeningen in de vroege fase (binnen 6 weken) effect hebben op de uitkomst na chirurgie. Abott (2013) toont dat het geven van restricties in de eerste 3 maanden na operatie (geen contactsporten, rennen, zwaar tillen, autorijden) niet leidt tot een betere uitkomst. Coronado (2000) concludeert dat rek- en spierkrachtoefeningen direct na de operatie niet leiden tot een betere (of slechtere) uitkomst. McFarland (2020) laat zien dat dagelijkse oefeningen met cervicale retractie in de eerste 6 weken niet leidt tot meer pijn of functieverlies, maar ook niet tot verbetering van de uitkomst.

In de regel herstellen patiënten na operatieve behandeling van een CRS binnen 6 weken tot 3 maanden (expert opinion; Peorsson, 1997). Daarom meent de werkgroep dat snelle hervatting van alle activiteiten op geleide van de pijn mogelijk is.

Een mogelijk gevaar schuilt echter in het te snel hervatten van activiteiten, waarbij snelle nekbewegingen nodig zouden kunnen zijn (zoals autorijden en fietsen). Indien snelle of natuurlijke hervatting van alle activiteiten niet mogelijk blijkt of leidt tot overbelastingsklachten dan kan ergotherapie geïndiceerd zijn. Een ergotherapeut beschikt over interventies om het activiteitenniveau van betrokkene gedoseerd op te kunnen bouwen en stimuleert hierbij eigen regie en zelfmanagement. Werkhervatting kan hierdoor bespoedigd worden en/of leidt minder vaak tot terugval. Dit geldt ook voor het functioneren in de thuissituatie. Het effect van een van de ergotherapeutische methodes (WAHW) wordt op dit moment wetenschappelijk onderzocht.

De literatuur toont niet dat het geven van restricties helpt. Hier ligt een kennislacune. Beter onderzoek is nodig met gebruik van performance-tests zoals de FIT-HaNSA (McGee, 2019). Ook vanuit de richtlijnen ‘Geïnstrumenteerde wervelkolomchirurgie’- (NOV, 2017) en ‘Lumbosacraal radiculair syndroom’ (NVN, 2020) is geen informatie voorhanden die te extrapoleren is naar patiënten met CRS. Ten aanzien van restrictie met autorijden is alleen een survey onder chirurgen na spinale chirurgie in de brede zin van het woord bekend, waarbij de grootste groep (58%) als advies geeft hervatten autorijden na 3 tot 6 weken (McGregor, 2006). Enige beperking ten aanzien van werk of andere activiteiten bestaat uiteindelijk niet. Aanvankelijk kunnen nekklachten een beperkende factor zijn, waardoor de werkomgeving indien mogelijk aangepast moet worden. Ook de mogelijkheid om regelmatig van houding te kunnen wisselen of van activiteit te veranderen draagt bij aan een snellere volledige werkhervatting, zo blijkt uit de praktijk.

De werkgroep acht het van belang dat pre-operatief de patiënt goed voorbereid is op het hersteltraject na de operatie. Hervatting van autorijden en werk zijn hierbij belangrijke punten. Hierbij kan bijvoorbeeld een concreet plan ten aanzien van hervatting van activiteiten bij helpen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Het doel is om de patiënt zo snel als mogelijk is, alles weer te laten doen zónder risico op complicaties. Daarbij is het ook van belang om te voorkomen dat de patiënt de nek te veel belast kort na de operatie en daarmee een geprolongeerd herstel bewerkstelligt. De patiënt is gediend bij het geven van adviezen die zo concreet als mogelijk zijn en al worden gegeven voor de operatie plaatsvindt. De patiënt zal echter moeten omgaan met het feit dat er onzekerheid is of de postoperatieve adviezen zinvol zijn en dat het ook een kwestie is van ‘gezond verstand’. Autorijden en werkhervatting zijn belangrijke aspecten om te bespreken.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Kosten-effectiviteitsstudies rondom dit onderwerp zijn de werkgroep niet bekend. Sneller minder restricties zal een snellere hervatting van dagelijkse activiteiten en werkhervatting betekenen, wat zeer waarschijnlijk zal resulteren in lagere kosten.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Er is geen onderzoek bekend dat heeft gekeken naar de aanvaardbaarheid en haalbaarheid van de postoperatieve adviezen. Gezien het ontbreken van een standaard dient de operateur de adviezen goed en op tijd af te stemmen met de patiënt. De werkgroep voorziet geen barrières op het gebied van aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid of implementatie.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Uit de literatuur is geen sterk bewijs gevonden over postoperatieve adviezen. In de regel herstellen patiënten na operatieve behandeling van een CRS snel. Daarom meent de werkgroep dat snelle hervatting van alle activiteiten mogelijk is. Het is hierbij van belang dat preoperatief een plan en/of verwachtingen met de patiënt worden afgestemd. Postoperatief is het van belang te streven naar het snel oppakken van activiteiten. Nader onderzoek op dit gebied is gewenst.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Bij patiënten met het cervicaal radiculair syndroom (CRS) die een operatie ondergaan is er veel variatie in het advies aangaande de restricties en belastbaarheid van de nek in het postoperatieve beleid. De huidige klinische praktijk is niet gestandaardiseerd ten aanzien van belastbaarheidsadviezen en fysio-/oefenherapeutische nabehandeling. Hierin heerst praktijkvariatie. Ten grondslag aan de praktijkvariatie ligt het feit dat momenteel onduidelijk is welke postoperatieve adviezen rondom fysieke belastbaarheid na de operatie zouden moeten zijn. Deze module evalueert welk postoperatief beleid ten aanzien van belastbaarheid van de nek met meest passend is voor patiënten met CRS.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Conclusions – PICO 1

What are the effects of postoperative advice of activity limitations compared to no physical restrictions in patients who have undergone surgery for CRS, in the acute postoperative phase (first 6 weeks after surgery)?

1a. Quality of life (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The possible beneficial effect of activity restrictions within the first 6 weeks after ACDF surgery on the physical component of quality of life is very uncertain, as is the effect on the mental component of quality of life, compared to no activity restrictions.

Source: Abbott (2013), Coronado (2020) |

1b. Global perceived effect (critical)

|

- GRADE |

The outcome global perceived effect was not reported and could not be graded. |

1c. Pain (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The possible beneficial effect on pain outcomes of activity restrictions within the first 6 weeks after ACDF surgery compared to no activity restrictions is very uncertain.

|

1d. Disability (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of activity restrictions within the first 6 weeks after ACDF surgery compared to no activity restrictions on disability.

Source: Abbott (2013), Coronado (2020), McFarland (2020) |

1e. Return to work (important); 1f. Adjacent level disease (important)

|

- GRADE |

The outcomes return to work and adjacent level disease were not reported and could not be graded. |

Conclusions – PICO 2

What are the effects of postoperative advice of activity limitations compared to no physical restrictions in patients who have undergone surgery for CRS, after an initial postoperative recovery period (starting 6 weeks after surgery)?

2a. Quality of life (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of activity limitations starting 6 weeks after ACDF surgery on quality of life compared to no activity restrictions, for patients with CRS.

Source: Peolsson (2019) |

2b. Global perceived effect (critical)

|

- GRADE |

The outcome global perceived effect was not reported and could not be graded. |

2c. Pain (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of activity limitations starting 6 weeks after ACDF surgery on pain outcomes compared to no activity restrictions, for patients with CRS.

Source: Peolsson (2019) |

2d. Disability (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of activity limitations starting 6 weeks after ACDF surgery compared to no activity restrictions on disability in patients with CRS.

Source: Peolsson (2019) |

2e. Return to work (important); f. Adjacent level disease (important)

|

- GRADE |

The outcomes return to work and adjacent level disease were not reported and could not be graded. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies - PICO 1 (acute postoperative phase)

Abbott (2013) investigated the physical, functional, and quality of life-related outcomes of patients undergoing anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF), with and without post-operative activity restrictions (i.e. collar usage). To this end, patients aged 18 to 65 years planned to undergo ACDF were randomized before surgery into the intervention group (n = 17) or the control group (n = 16). During the first days after surgery, both groups received respiratory and circulatory exercises, training of transfers, walking, and activities of daily living by a physiotherapist. Patients in the intervention group received a rigid cervical collar to be worn during daytime over a 6-week period and restrictions from certain activities in the first 3 months after the operation (restricted from activities such as contact sports, running, heavy lifting, driving, and outer-range cervical spine movements). The control group received no postoperative neck movement restrictions. The outcomes quality of life (SF-36), pain (Borg CR-10), and disability (NDI) were assessed after 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months.

Coronado (2020) performed an RCT to examine the acceptability and outcome effects of an early self-directed home exercise program (HEP) within the first 6 weeks after ACDF. Patients aged 21 or older undergoing ACDF were included and randomized to the early HEP (n = 15) or usual care (n = 15). Usual care was administered to both groups and comprised:

- medication,

- cervical collar as indicated (9 patients in HEP-group (60%) and 11 patients in usual care group (73%)),

- driving restrictions (varying from 2 to 6 weeks after surgery), or

- lifting restrictions (not more than 15 pounds or perform sudden or extreme neck movements).

The early HEP was a 6-week self-directed program directly after surgery with walking, sleeping instructions, and range of motion and strengthening exercises performed daily, with personalized adaption by the physiotherapist every 2 weeks. After 6 weeks, 6 months and 12 months, quality of life was measured through the SF-12, arm and neck pain through the NRS, and disability through the NDI.

McFarland (2020) compared clinical outcomes between early cervical spine stabilizer (ECS) training and usual care in patients after ACDF in an RCT. Randomization of patients aged 30 to 75 years and scheduled to undergo ADCF surgery for MRI-confirmed cervical nerve root compression causing radiculopathy took place. Patients were either randomly allocated to ECS training for 6 weeks (n = 20), or usual care for 6 weeks (n = 20). ECS comprised specific instructions with pictures and descriptions of 10 exercises (performed daily with increasing repetitions) for achieving correct positioning and movement; and a walking program. Usual care consisted of a DVD with general spine surgery precautions, and instructions in proper posture, use of cervical collar if applicable, and safety with transfers and walking. Pain (NPRS) and disability (NDI) were the outcomes assessed after 6 and 12 weeks.

Results – PICO 1

1a. Quality of life

Rest versus no rest

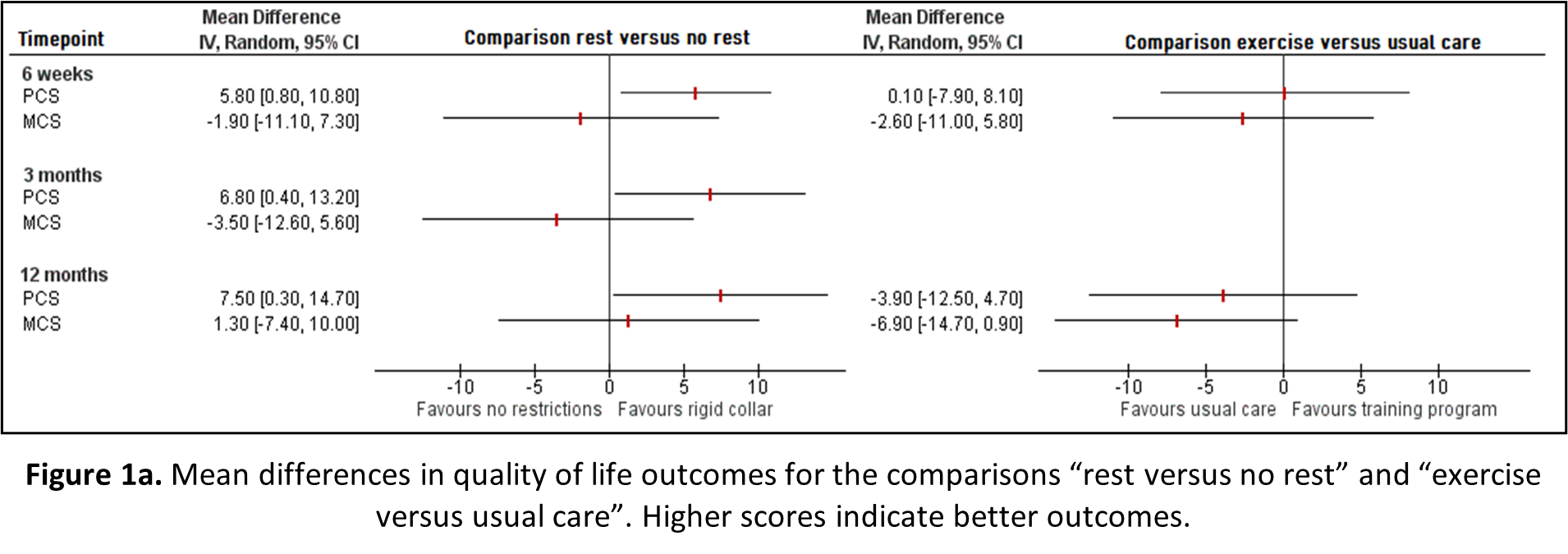

Quality of life was reported by Abbott (2013) after 6 weeks, 3 months and 12 months through the SF-36, for patients receiving movement restrictions (secured by prescribing a rigid collar) post-operative compared to patients receiving no advice with regard to activity restrictions.

Exercise versus usual care

Coronado (2020) reported quality of life after 6 weeks and 12 months for patients receiving an early home exercise program and patients receiving usual care, measured through the SF-12. The mean differences in quality of life for the physical (PCS) and mental component score (MCS) between rest and no rest, and exercise and usual care, is depicted in Figure 1a.

For the comparison “rest versus no rest”, rest (movement restrictions and collar) seems to positively affect the PCS (statistically significant), yet possibly negatively affect the MCS; however, this effect on the MCS has disappeared after 12 months. For the comparison “Exercise versus usual care”, a training program does not seem to affect PCS and negatively affect MCS. However, none of the observed differences in PCS and MCS in both comparisons exceed the borders for clinical relevance.

1b. Global perceived effect

No studies reported on the outcome measure global perceived effect.

1c. Pain

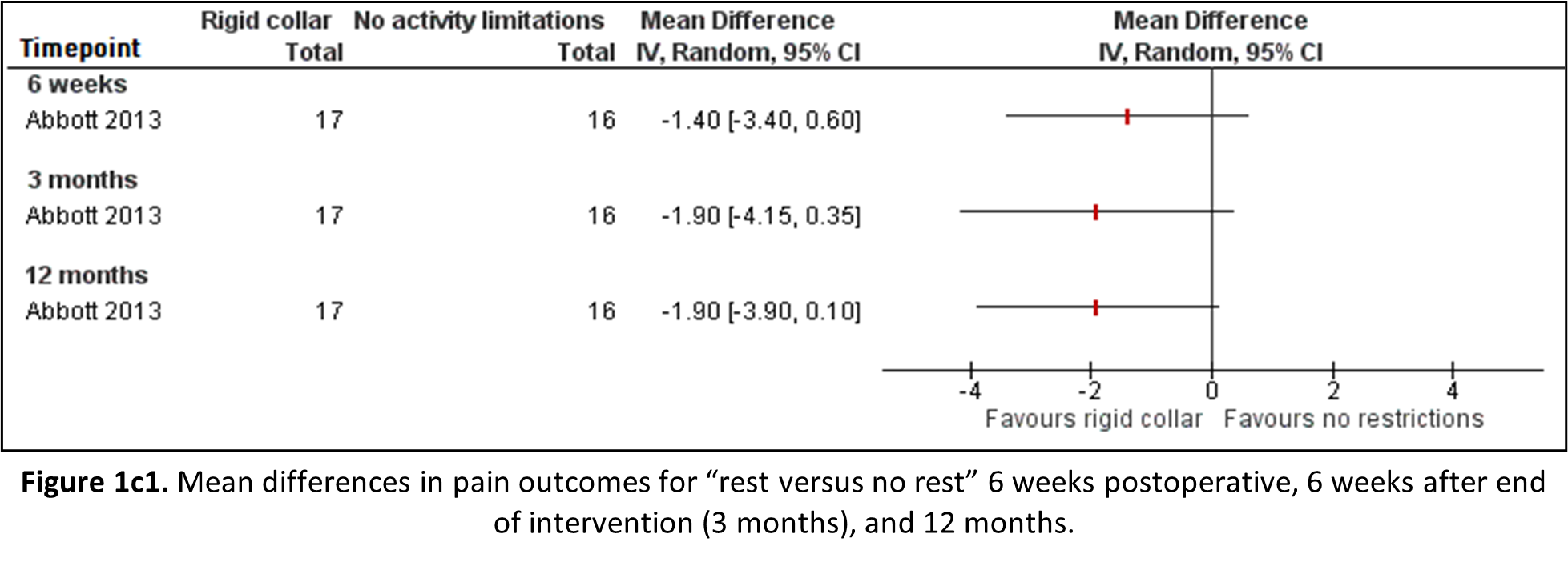

Rest versus no rest

Abbott (2013) reported average pain intensity over 24 hours in the neck and shoulder/arm region on the Borg CR-10 scale. This scale was not previously defined (under the heading “Search and select”, subheading “Relevant outcome measures”), yet ranges from 0 (least intense pain) to 10 (most intense pain), and correlates with the VAS (Harms-Ringdahl, 1986). Therefore, the outcomes are reported and depicted in Figure 1b1. Point estimates of pain scores show a clinically relevant effect in favour of movement restrictions, however the confidence interval crosses the border of clinical relevance and significance, implying different inferences.

Exercise versus usual care

Both Coronado (2020) and McFarland (2020) reported pain outcomes through the NRS, after 6 weeks and 12 months, and 6 weeks and 3 months, respectively. Both studies compare an early training programme (home exercise program or cervical spine stabilizer training) to usual care. The results are depicted in Figure 1b2. Observed differences in pain are not statistically significant, nor clinically relevant.

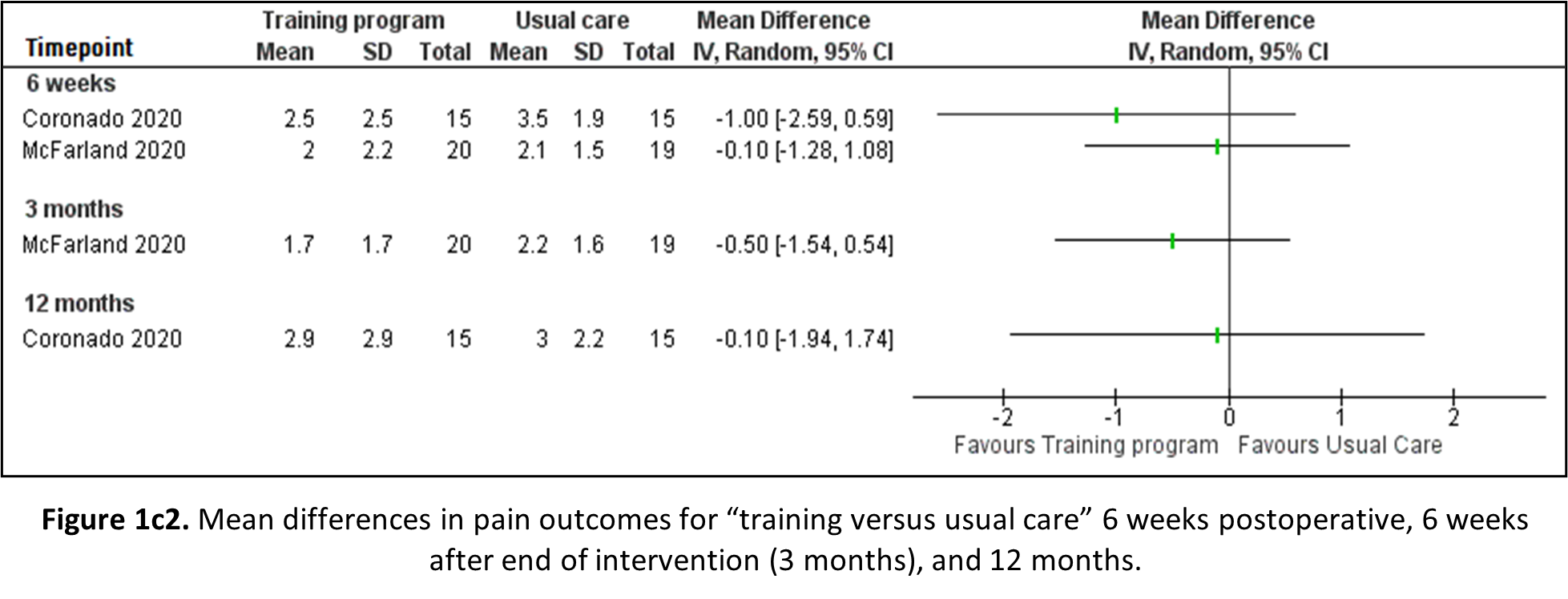

1d. Disability

Rest versus no rest

Abbott (2013) reported disability through the Neck Disability Index (NDI) on a scale of 0 to 50 for patients receiving movement restrictions post-operative compared to patients receiving no advice with regard to activity restrictions. Mean differences are shown in Figure 1d1. Despite being statistically significant at 6 weeks, none of the observed differences in disability are clinically relevant.

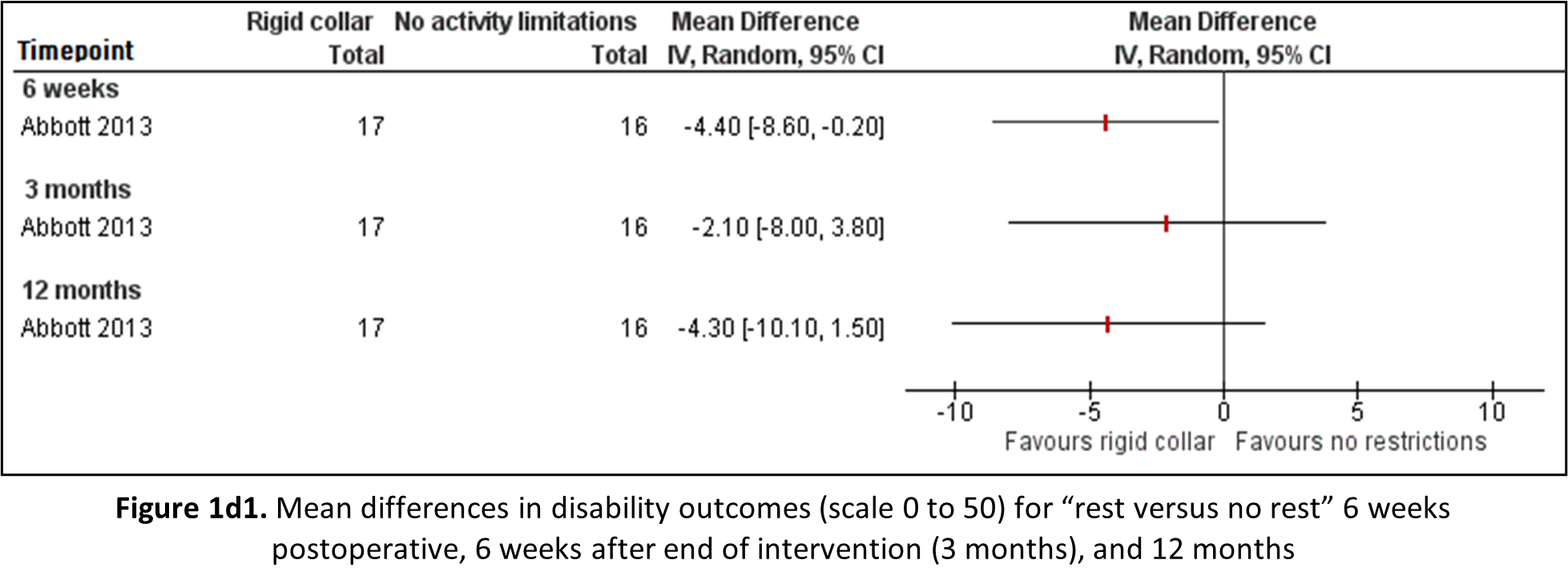

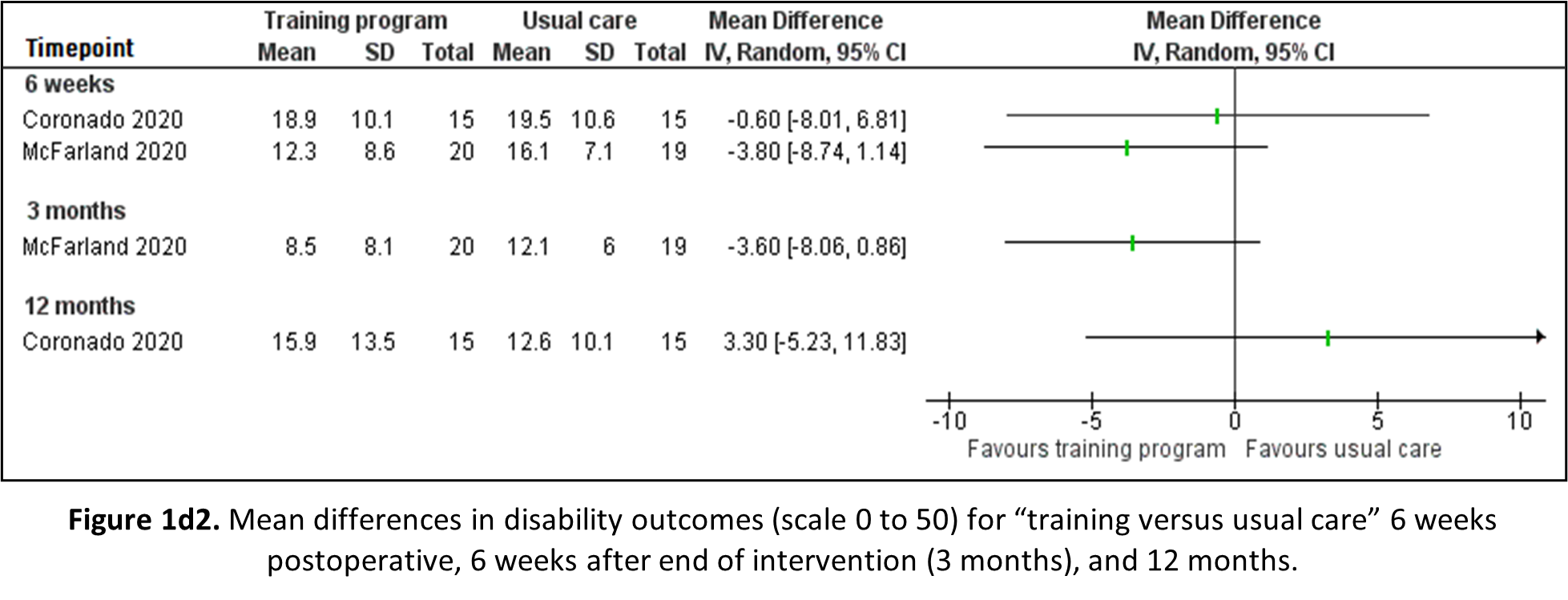

Exercise versus usual care

Both Coronado (2020) and McFarland (2020) reported disability outcomes through the NDI: the former on a scale from 0 to 50 after 6 weeks and 12 months; the latter on a scale from 0 to 100 afters 6 weeks and 3 months, respectively. The results are depicted in Figure 1d2. For reading and interpretation purposes the score of McFarland have been divided by 2. No observed differences were statistically significant or clinically relevant.

No studies reported on the outcome measure return to work.

1f. Adjacent level disease

Coronado (2020) did not specifically report adjacent level disease but noted that no participants underwent revision surgery during follow-up.

Level of evidence of the literature – PICO 1

1a. Quality of life (critical)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life was downgraded:

6. For Rest versus no rest by 4 levels because of unclear randomization, no blinding, and a large proportion loss to follow-up (-2, risk of bias); and the inclusion of a single study, with confidence intervals of the estimate crossing the border of clinical relevance (-2, imprecision).

7. For Exercise versus usual care by 4 levels because of unclear randomization in one study, insufficient blinding, and selective reporting in one study (-1, risk of bias); not comparing relative rest to no activity restrictions (-1, bias due to indirectness); and the inclusion of a single study, with confidence intervals of the estimate crossing the border of clinical relevance (-2, imprecision).

No downgrading took place for inconsistency or publication bias.

1b. Global perceived effect (critical)

The outcome global perceived effect was not reported and could not be graded.

1c. Pain (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain was downgraded by 3 levels:

- For Rest versus no rest because of unclear randomization, no blinding, and a large proportion loss to follow-up (-2, risk of bias); and the inclusion of a single study, with confidence intervals of the estimate crossing the border of clinical relevance (-1, imprecision).

- For Exercise versus usual care because of unclear randomization in one study, insufficient blinding, and selective reporting in one study (-1, risk of bias); not comparing relative rest to no activity restrictions (-1, bias due to indirectness); the confidence intervals of the clinical estimates crossing the border of clinical relevance (-1, imprecision).

No downgrading took place for inconsistency or publication bias.

1d. Disability (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure disability was downgraded by 4 levels:

- For Rest versus no rest because of unclear randomization, no blinding, and a large proportion loss to follow-up (-2, risk of bias); and the inclusion of a single study, with confidence intervals of the estimate crossing the border of clinical relevance (-2, imprecision).

- For Exercise versus usual care because of unclear randomization in one study, insufficient blinding, and selective reporting in one study (-1, risk of bias); not comparing relive rest to no activity restrictions (-1, bias due to indirectness); and the confidence intervals of the estimates crossing both borders of clinical relevance (-2, imprecision).

No downgrading took place for inconsistency or publication bias.

1e. Return to work (important); and 1f. Adjacent level disease (important)

The outcomes return to work and adjacent level disease were not reported and could not be graded.

Description of studies - PICO 2 (initial postoperative recovery period)

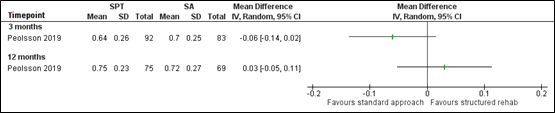

The RCT by Peolsson (2019) investigated the additional benefits of structured postoperative rehabilitation programme (SPT) over a standard approach (SA). Patients with MRI evidence of disc herniation and concomitant clinical signs of cervical radiculopathy for which they underwent surgery, were randomized to either the SPT group (n = 101) or the SA (n = 100) group. Both groups underwent equal postoperative care within the first 6 weeks after surgery. The SPT programme included physiotherapy sessions (from 6 weeks after surgery up until 24 weeks) with individually and progressively adjusted neck-specific exercises and a behavioural approach. The standard postoperative approach comprised usual care with the possibility to seek physiotherapy upon the patient’s own initiative. Outcomes were quality of life, pain, and disability, after 3 months, 6 months, 12 months and 24 months.

Results – PICO 2

2a. Quality of life

Peolsson (2019) reported the quality of life through the EQ-5D questionnaire, scoring from 0 to 1. Mean differences after 3 and 12 months are depicted in Figure 2a (per-protocol analysis). The SMD from ANOVA intention-to-treat analysis between groups was 0.02, indicating no difference in effect between SPT and SA.

Figure 2a. Mean differences in quality of life outcomes between a standardized postoperative rehabilitation program (SPT) and a standard postoperative approach (SA), per-protocol. Higher scores indicate better outcomes.

2b. Global perceived effect

No studies reported on the outcome measure global perceived effect.

2c. Pain

Pain was reported by Peolsson (2019) through the VAS from 0 to 100 mm. The mean difference (from per-protocol data) at 3 months between SPT and SA was 3.0 (95%CI -3.5 to 9.5); and at 12 months 0 (95% CI -7.7 to 7.7). This is not statistically significant nor clinically relevant. The SMD from ANOVA intention-to-treat analysis between groups was 0.07, indicating no difference in effect between SPT and SA.

2d. Disability

The outcome disability was reported after 3 and 12 months through the NDI, on a scale from 0 to 100% (Peolsson, 2019). After 3 months, disability (per-protocol data) was higher in the SPT group (mean difference 4.0; 95% CI -1.0 to 9.0), but after 12 months higher in the SA group (mean difference -2.0; 95% CI -7.8 to 3.8). These differences are not statistically significant, nor clinically relevant. The SMD from ANOVA intention-to-treat analysis between groups was 0.03, indicating no difference in effect between SPT and SA.

2e. Return to work; and 2f. Adjacent level disease

The outcome measures return to work or adjacent level disease were not reported.

Level of evidence of the literature – PICO 2

2a. Quality of life (critical)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life was downgraded by 4 levels because of insufficient blinding, frequent loss to follow-up, and dilution of potential effect due to study methods (-1, risk of bias); not comparing relative rest to no activity restrictions (-1, bias due to indirectness); and the inclusion of a single study, with confidence intervals of the estimate crossing the border of clinical relevance (-2, imprecision). No downgrading took place for inconsistency or publication bias.

2b. Global perceived effect (critical)

The outcome global perceived effect was not reported and could not be graded.

2c. Pain (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain was downgraded by 3 levels because of insufficient blinding, frequent loss to follow-up, and dilution of potential effect due to study methods (-1, risk of bias); not comparing relative rest to no activity restrictions (-1, bias due to indirectness); and the inclusion of a single study that was underpowered for this comparison (-1, imprecision). No downgrading took place for inconsistency or publication bias.

2d. Disability (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure disability was downgraded by 3 levels because of insufficient blinding, frequent loss to follow-up, and dilution of potential effect due to study methods (-1, risk of bias); not comparing relative rest to no activity restrictions (-1, bias due to indirectness); and the inclusion of a single study that was underpowered for this comparison (-1, imprecision). No downgrading took place for inconsistency or publication bias.

2e. Return to work (important); 2f. Adjacent level disease (important)

The outcomes return to work and adjacent level disease were not reported and could not be graded.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following questions:

PICO 1: What are the effects of postoperative advice of activity limitations compared to no physical restrictions in patients who have undergone surgery for CRS, in the acute postoperative phase (first 6 weeks after surgery)?

P: Patients who underwent surgery for CRS

I: Advice within first 6 weeks after surgery: activity limitations

C: Advice within first 6 weeks after surgery: no activity limitations/no physical restrictions

O: Quality of life, global perceived effect, pain, disability, return to work, adjacent level disease

PICO 2: What are the effects of postoperative advice of activity limitations compared to no physical restrictions in patients who have undergone surgery for CRS, after an initial postoperative recovery period (starting 6 weeks after surgery)?

P: Patients who underwent surgery for CRS

I: Advice starting 6 weeks after surgery: activity limitations (after initial postoperative recovery)

C: Advice starting 6 weeks after surgery: no activity limitations/no physical restrictions (after initial postoperative recovery)

O: Quality of life, global perceived effect, pain, disability, return to work, adjacent level disease

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered quality of life and global perceived effect as critical outcome measures for decision making; and pain, disability, return to work and adjacent level disease as important outcome measures for decision making. The working group defined the outcome measures as in Table 1.

The working group defined a 10% difference for continuous outcome measures (weighted mean difference), 20% for dichotomous outcome measures informing on relative risk (RR ≤ 0.91 and ≥ 1.25), and 0.5 for Cohen’s d in standardized mean difference (SMD ≤-0.5 and ≥ 0.5) as minimal clinically (patient) important differences. This decision was based on the minimal important change scores described in the article by Ostelo (2008), in accordance with the Dutch Lumbosacral Radicular syndrome guideline (NVN, 2020).

Table 1. Definitions and instruments of researched outcome measures

|

Outcome |

Instrument |

Abbreviation |

Explanation/Definition |

Scale |

|

Quality of Life |

Short Form 36 |

SF-36 |

A multidimensional instrument consisting of 36 questions; higher scores indicating a better health status. It can generate 2 summary scores: Physical (PCS) and Mental Component Score (MCS). |

0 to 100 |

|

Short Form 12 |

SF-12 |

Questionnaire with 12 questions; higher scores indicating a better health status. It can generate scores on the physical (PCS) and mental health subscale (MCS). |

0 to 100 |

|

|

EuroQoL-5D |

EQ-5D |

This questionnaire generates an index score based on 5 questions on quality of life and has a VAS for current health state. Higher scores represent better (perceived) health. |

Index: 0 to 1 VAS: 0 to 100 |

|

|

Global perceived effect |

Global perceived effect (GPE) |

GPE-DV |

Questionnaire to measure patients’ assessment of change in main complaint, on a scale from “fully recovered” (low score) to “much worse” (high score) |

1 to 7 or 1 to 9 |

|

Pain |

Visual Analog Scale |

VAS |

Line on which patients can indicate their pain from 0 (no pain) to 100 (worst pain imaginable) |

0 to 100mm or 10cm |

|

Numerical (Pain) Rating Scale |

N(P)RS |

An 11-point scale on which patients can indicate their pain from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable) |

0 to 10 |

|

|

Disability |

Neck Disability Index |

NDI |

Ten 5-point questions, after which total score is multiplied by 2 (seldom exceptions). Disability increases with increasing score. |

0 to 100 (or 0 to 50) |

|

Return to work |

- |

- |

Was not defined a priori by the working group, instead the definitions used in the studies were used. |

- |

|

Adjacent level disease |

- |

- |

Was not defined a priori by the working group, instead the definitions used in the studies were used. |

- |

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 1990 until 17 August 2022. The detailed search strategy is available upon request. The systematic literature search resulted in 382 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic review and/or meta-analysis, with detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment, and results of individual studies available; or randomized controlled trial (RCT);

- Patients aged ≥ 18 years;

- studies including ≥ 20 (10 in each study arm) patients;

- studies according to the PICOs (found under the heading “Search and select”);

- Follow-up period for PICO 1 of 6 weeks, 12 weeks or 3 months, and/or 12 months; and for PICO 2 a period of 3 months/12 weeks and/or 12 months;

- full-text English or Dutch language publication

Thirteen studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, nine studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the heading “Evidence Tables”) and four studies were included (PICO 1 n=3; PICO 2 n=1).

Results

Four studies were included in the analysis of the literature, three RCTs for PICO 1 and one RCT for PICO 2. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Abbott A, Halvorsen M, Dedering A. Is there a need for cervical collar usage post anterior cervical decompression and fusion using interbody cages? A randomized controlled pilot trial. Physiother Theory Pract. 2013 May;29(4):290-300. doi: 10.3109/09593985.2012.731627. Epub 2012 Oct 17. PMID: 23074995.

- Coronado RA, Devin CJ, Pennings JS, Vanston SW, Fenster DE, Hills JM, Aaronson OS, Schwarz JP, Stephens BF, Archer KR. Early Self-directed Home Exercise Program After Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion: A Pilot Study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2020 Feb 15;45(4):217-225. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000003239. PMID: 31490861.

- Harms-Ringdahl K, Carlsson AM, Ekholm J, Raustorp A, Svensson T, Toresson HG. Pain assessment with different intensity scales in response to loading of joint structures. Pain. 1986 Dec;27(3):401-411. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(86)90163-6. PMID: 3808744.

- McFarland C, Wang-Price S, Gordon CR, Danielson GO, Crutchfield JS, Medley A, Roddey T. A Comparison of Clinical Outcomes between Early Cervical Spine Stabilizer Training and Usual Care in Individuals following Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion. Rehabil Res Pract. 2020 Apr 24;2020:5946152. doi: 10.1155/2020/5946152. PMID: 32373366; PMCID: PMC7196146.

- Peolsson A, Löfgren H, Dedering Å, Öberg B, Zsigmond P, Hedevik H, Wibault J. Postoperative structured rehabilitation in patients undergoing surgery for cervical radiculopathy: a 2-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. J Neurosurg Spine. 2019 Mar 22;31(1):60-69. doi: 10.3171/2018.12.SPINE181258. PMID: 30901755

Evidence tabellen

Evidence tables

PICO1

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Abbot, 2013 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Single academic centre, Sweden

Funding and conflicts of interest: authors report “no declaration of interest”, funding information not disclosed in article. |

Inclusion criteria: (1) Aged 18-65 years, (2) clinical and radiological signs of cervical root compression with corresponding pain distribution for >3 months, for which conservative treatment had failed, (3) primary diagnosis of cervical spondylosis, disc herniation or degenerative disc disease, (4) planned to undergo ACDF

Exclusion criteria: (1) Inability to understand Swedish, (2) previous ACDF surgery

N total at baseline: 33 Intervention (I): 17 Control (C): 16

Important prognostic factors: age ± SD: I: 53.4 ± 13 C: 47.3 ± 11

Sex (% M): I: 53%| C: 69%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

During first days after surgery: respiratory and circulatory exercises, training of transfers, walking and activities of daily living relevant for the patient by physiotherapist. Before discharge instruction for home training program for shoulder and thoracic mobility, stabilization of cervical spine and walking. |

Length of follow-up: 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 9 (53%) Control: 9 (56%) Reasons: not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Up until 6 months: 9 (I: 5, C: 4) Up until 1 year: 13 (I: 7, C: 6) Up until 2 years: 18 (I: 9, C: 9)

|

Outcome measures and effect size (including 95%CI):

Quality of Life (SF-36) Mean difference (95% CI) 6w PCS 5.8 (0.8 to 1.07) MCS -1.9 (-11.1 to 7.4) 3m PCS 6.8 (0.4 to 13.1) MCS -3.5 (-12.6 to 5.6) 12m PCS 7.5 (0.3 to 14.6) MCS 1.3 (-7.4 to 10.1)

Pain (Borg CR-10 scale) Neck pain, mean difference (95% CI) 6w: -1.4 (-3.4 to 0.6) 3m: -1.9 (-4.1 to 0.4) 12m: -1.9 (-3.9 to 0.01)

Disability (NDI) Mean difference (95% CI) 6w: -4.4 (-8.6 to -0.2) 3m: -2.1 (-8.0 to 3.8) 12m: -4.3 (-10.1 to 1.5) |

Author’s conclusion: short-term cervical collar use post ACDF with interbody cage may help certain patients cope with initial post-operative pain and disability.

Remarks: imprecise; post-hoc analyses without sample size calculation |

|

|

Rigid cervical collar at daytime over a 6-week period. In first 3 weeks both in- and outdoors, in second 3 weeks collar could be removed when sitting indoors with the neck supported.

Restriction from certain activities in first 3 months after the operation. |

No postoperative neck movement restrictions.

|

||||||

|

Coronado, 2020 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Single academic centre, United States of America

Funding and conflicts of interest: two non-commercial grants, consultancy grants and expert testimony. |

Inclusion criteria: (1) Patients aged ≥21, (2) undergoing ACDF for cervical stenosis, spondylosis, degenerative spondylolisthesis, or disc herniation

Exclusion criteria: (1) Surgery secondary to trauma, fracture, tumor, infection or spinal deformity, (2) undergoing cervical corpectomy, (3)

N total at baseline: 30 Intervention (I): 15 Control (C): 15

Important prognostic factors: age ± SD: I: 51.8 ± 10.3 C: 49.3 ± 11.9

Sex (% M) I: 40.0% | C: 53.3%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Usual postoperative care, including medication, cervical collar as indicated, and driving (2 to 6 weeks) or lifting restrictions (not >15 pounds). |

Length of follow-up: 6 weeks, 6 months and 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: 2 Intervention: 1 (6.7%) Control: 1. (6.7%) Reasons: not reported

Incomplete outcome data: See above.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (including 95%CI):

Quality of Life (SF-12) Mean difference (95% CI) 6w P 0.1 (-7.9 to 8.1) M -2.6 (11.0 to 5.8) 12m P -3.9 (-12.5 to 4.7) M -6.9 (-14.7 to 0.9)

Pain (NRS) Neck pain, mean difference (95% CI) 6w: -1.0 (-2.6 to 0.6) 12m: -0.1 (-1.9 to 1.7)

Disability (NDI) Mean difference (95% CI) 6w: -0.6 (-8.0 to 6.8) 12m: 3.3 (-5.2 to 11.8) |

Authors’ conclusion: exercise may be an effective pain management approach in the short-term, with potential for long-term reductions in opioid utilization

Remarks: underpowered (pilot design) |

|

|

Early self-directed Home Exercise program for 6 weeks directly after surgery with walking, and sleeping instructions and range of motion and strengthening exercises, performed daily, progressing in intensity every 2 weeks. Support was through weekly phone calls by the physiotherapist giving personalized adaptation. |

|

||||||

|

McFarland, 2020 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Single centre, United States of America

Funding and conflicts of interest: authors report no conflict of interest, funding information not disclosed in article. |

Inclusion criteria: (1) Age 30-75 years, (2) scheduled to undergo ACDF surgery, (3) cervical radiculopathy verified using MRI

Exclusion criteria: (1) musculoskeletal or systemic disorders that would limit activity required for the study, (2) pain >8 (out of 10) on NPRS, (3) prior cervical spine surgery

N total at baseline: 40 Intervention (I): 20 Control (C): 20

Important prognostic factors: age ± SD: I: 54.7 ± 10.5 C: 56.0 ±9.8

Sex (%M) I: 30% | C: 50%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Early cervical spine stabilizer training for 6 (+ 6) weeks: specific instructions with pictures and descriptions of 10 exercises for achieving correct positioning and movement. Performed daily, increasing exercise by one repetition every other day until 30 repetitions (without aggravating symptoms).

Plus a walking program with written instructions and attention to proper posture, having to record walking distance |

Usual care for 6 weeks: instructions in proper posture (head neutral position and avoiding looing up), use of cervical collar if applicable, and safety with transfers and gait. A DVD with general spine surgery precautions and instructions. Nonpharmacological pain management instructions (ice pack, deep breathing, walking)

Plus general instructions to walk. |

Length of follow-up: 6 and 12 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 3 (15%) Control: 4 (20%) Reasons: Withdrew from study (n = 1), did not return for follow-up (n = 5), discontinued due to medical complications (n = 1)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: 5 (25%) Control: 7 (35%) Reasons: see loss to follow-up, plus 5 patients released by surgeon and followed-up on phone.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (including 95%CI):

Pain (NPRS) Mean difference (95% CI) 6w: -0.1 (--1.3 to 1.1) 3m: -0.5 (-1.5 to 0.5)

Disability (NDI) Mean difference (95% CI) 6w: -7.6 (-17.5 to 2.3) 3m: -7.3 (-16.2 to 1.6) |

Authors’ conclusion: Because both the UC training and ECS training resulted in the same amount of improvements at 6 and 12 weeks, UC training may be sufficient for the patient’s first three months of recovery after ACDF surgery.

Remarks: imputation under unreasonable assumption (imprecise) |

PICO2

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Peolsson, 2019 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Single academic centre, Sweden

Funding and conflicts of interest: authors report no conflict interest”, funding from mainly non-commercial parties. |

Inclusion criteria: (1) having undergone surgery based on (1a) clinical findings of nerve root compression, confirmed through MRI, (1b) radiculopathy, (1c) ≥ 2 months of persistent nerve root pain; (2) age 18-70 years

Exclusion criteria: (1) myelopathy, (2) previous fracture, subluxation or surgery of cervical column, (3) malignancy, (4) spinal infection, (5) systemic disease or trauma that contra-indicates the treatment program, (6) severe psychiatric disorder or known drug abuse, (7) inability to understand Swedish

N total at baseline: 201 Intervention (I): 101 Control (C): 100

Important prognostic factors: age ± SD: I: 50 ± 8.2 C: 50 ± 8.7

Sex (% M): I: 51%| C: 54%

Groups comparable at baseline? Intervention group had a longer median duration of neck pain before surgery |

Regular postoperative care during first 5 weeks (information and advice about posture and ergonomics, mobility exercises for the shoulders and avoidance of certain tasks that may have a negative effect on the healing process or pain) and one routine visit to physiotherapist at 6 weeks postoperative |

Length of follow-up: 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 30 (30%) Control: 38 (38%) Reasons: unknown

Incomplete outcome data: Up until 3 months: 26 (I: 9, C: 17) Up until 6months: 29 (I: 11, C: 18) Up until 1 years: 57 (I: 26, C: 31)

|

Outcome measures and effect size (including 95%CI):

Quality of Life (EQ-5D) Mean difference (95% CI) 3m: -0.06 (-0.14 to 0.02) 12m: 0.03 (-0.05 to 0.11) Cohen’s d for ANOVA between-group difference ITT over time: 0.02

Pain (VAS) Neck pain, mean difference (95% CI) 3m: 3.0 (-3.5 to 9.5) 12m: 0.0 (-7.7 to 7.7) Cohen’s d for ANOVA between-group difference ITT over time: 0.07

Disability (NDI) Mean difference (95% CI) 3m: 4.0 (-1.0 to 9.0) 12m: -2.0 (7.8 to 3.8) Cohen’s d for ANOVA between-group difference ITT over time: 0.03

|

Author’s conclusion: postoperative SPT offered no additional benefits over SA in patients who had undergone CR. All patients improved over time for all of the outcome variables, and the results show that patients with CR can tolerate postoperative loading of the neck exercises

Remarks: Mean differences calculated on per-protocol data |

|

|

Structured postoperative rehabilitation (SPT) programme: physiotherapy session with neck-specific exercises, individually and progressively adjusted by physiotherapist. Once weekly for 6 weeks, then twice weekly for 12 weeks, with additional home exercises and encouragement to increase overall physical activity level. A behavioural approach was applied. |

Standard postoperative approach (SA): comprised usual care, without referral to a physiotherapist after surgery, but patients could seek physiotherapy themselves. |

||||||

Abbreviations: 12m: 12 months, 3m: 3 months, 6w: 6 weeks, ACDF: anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, CI: confidence interval, ITT: intention to treat, M: male, MCS: mental component score, MRI: magnetic resonance imaging, NPRS: numeric pain rating scale, PCS: physical component score, RCT: randomized controlled trial, SD: standard deviation

Risk of bias table for intervention studies

|

Study reference |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? |

Was the allocation adequately concealed? |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

|

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent? |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

|

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

|

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

|

|

Abbot, 2013 |

No information;

Reason: authors reported “random concealed allocation was the method used to form the groups” |

No information;

Reason: Method for concealment not reported. |

Definitely no;

Reason: Patients, health care providers and outcome assessors were not blinded (blinding of data collectors and analysts not reported) |

Definitely no;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was frequent in both groups. Intention to treat principle used for analysis, but unclear how missing data were handled. |

Probably yes;

Reason: no protocol available. All outcome measures from methods are described in the results. |

No information;

Reason: Largely underpowered, no other limitations described. |

HIGH

|

|

Coronado, 2020 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Computer generated scheme in a 1:1 ratio in blocks stratified by age and number of fusion levels |

Probably yes;

Reason: authors report “in a concealed manner using a computer generated scheme”, by personnel not responsible for recruitment |

Definitely no

Reason: Patients and health care providers not blinded, outcome assessors blinded. The blinding of data collectors and analysts is not reported. |

Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. Unclear whether adequate imputation methods were used |

Definitely no

Reason: deviation from protocol: no movement accelerometery and no fusion rate reported; yet opioid use is additionally reported. |

No information;

Reason: Underpowered, no other limitations described. |

Some concerns

|

|

McFarland, 2020 |

Probably no

Reason: randomization procedure not adequately described. |

Definitely no;

Reason: Study coordinator (registered nurse) made group assignment (unclear methods). |

Probably no;

Reason: patients and healthcare providers were not blinded to assignment. Data collector and outcome assessor was blinded but with high risk of obtaining knowledge of assignment; blinding of data analysts not reported. |

Probably no;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was frequent in intervention and control group. Imputation method following MCAR was used (inadequate). |

Probably no;

Reason: According to protocol, no cervical flexor endurance and pain were to be collected. |

Unclear;

Reason: Insufficient information how much of usual care training was applied in intervention group. |

HIGH

|

|

Peolsson, 2019 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: computerized randomization list created by statistician. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: list was handled by an independent researcher who put the results into opaque envelopes for further distribution |

Probably no;

Reason: patients and healthcare providers were not blinded to assignment. Data collector and outcome assessor were blinded; blinding of data analysts not reported. |

Probably no;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was frequent(>25%) in intervention and control group. Unclear imputation methods or analyses used. |

Definitely no;

Reason: According to protocol, 25 outcome measures; not all reported (e.g. work ability index) |

Unclear;

Reason: possible dilution of effect by pragmatic approach to control group (also allowed physiotherapy) |

Some concerns

|

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Bono CM, Leonard DA, Cha TD, Schwab JH, Wood KB, Harris MB, Schoenfeld AJ. The effect of short (2-weeks) versus long (6-weeks) post-operative restrictions following lumbar discectomy: a prospective randomized control trial. Eur Spine J. 2017 Mar;26(3):905-912. doi: 10.1007/s00586-016-4821-9. Epub 2016 Nov 2. PMID: 27807771. |

Wrong population (lumbar discectomy) |

|

Camara R, Ajayi OO, Asgarzadie F. Are External Cervical Orthoses Necessary after Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion: A Review of the Literature. Cureus. 2016 Jul 14;8(7):e688. doi: 10.7759/cureus.688. PMID: 27555986; PMCID: PMC4980205. |

Wrong study design |

|

Cheng CH, Tsai LC, Chung HC, Hsu WL, Wang SF, Wang JL, Lai DM, Chien A. Exercise training for non-operative and post-operative patient with cervical radiculopathy: a literature review. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015 Sep;27(9):3011-8. doi: 10.1589/jpts.27.3011. Epub 2015 Sep 30. PMID: 26504347; PMCID: PMC4616148. |

Wrong population |

|

Lantz JM, Abedi A, Tran F, Cahill R, Kulig K, Michener LA, Hah RJ, Wang JC, Buser Z. The Impact of Physical Therapy Following Cervical Spine Surgery for Degenerative Spine Disorders: A Systematic Review. Clin Spine Surg. 2021 Oct 1;34(8):291-307. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000001108. PMID: 33323701. |

Includes study of Peolsson (2019) which is included. |

|

Morris S, Morris TP, McGregor AH, Doré CJ, Jamrozik K. Function after spinal treatment, exercise, and rehabilitation: cost-effectiveness analysis based on a randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011 Oct 1;36(21):1807-14. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31821cba1f. PMID: 21505377. |

Wrong intervention |

|

Ozkara GO, Ozgen M, Ozkara E, Armagan O, Arslantas A, Atasoy MA. Effectiveness of physical therapy and rehabilitation programs starting immediately after lumbar disc surgery. Turk Neurosurg. 2015;25(3):372-9. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.8440-13.0. PMID: 26037176. |

Wrong population (lumbar discectomy) |

|

Svensson J, Hermansen A, Wibault J, Löfgren H, Dedering Å, Öberg B, Zsigmond P, Peolsson A. Neck-Related Headache in Patients With Cervical Disc Disease After Surgery and Physiotherapy: A 1-Year Follow-up of a Prospective Randomized Study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2020 Jul 15;45(14):952-959. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000003430. PMID: 32609465. |

Secondary analysis of Peolsson (2019), same study population |

|

Wibault J, Öberg B, Dedering Å, Löfgren H, Zsigmond P, Persson L, Andell M, R Jonsson M, Peolsson A. Neck-Related Physical Function, Self-Efficacy, and Coping Strategies in Patients With Cervical Radiculopathy: A Randomized Clinical Trial of Postoperative Physiotherapy. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2017 Jun;40(5):330-339. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2017.02.012. Epub 2017 May 9. PMID: 28495026. |

Precursor of Peolsson (2019), same study population |

|

Wibault J, Öberg B, Dedering Å, Löfgren H, Zsigmond P, Peolsson A. Structured postoperative physiotherapy in patients with cervical radiculopathy: 6-month outcomes of a randomized clinical trial. J Neurosurg Spine. 2018 Jan;28(1):1-9. doi: 10.3171/2017.5.SPINE16736. Epub 2017 Nov 3. PMID: 29087809. |

Precursor of Peolsson (2019), same study population |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 24-07-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-07-2024

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodules is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de ‘samenstelling van de werkgroep’) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met een CRS.

WERKGROEP

- Mevr. dr. Carmen Vleggeert-Lankamp (voorzitter), neurochirurg, NVvN

- Dhr. dr. Ruben Dammers, neurochirurg, NVvN

- Mevr. drs. Martine van Bilsen, neurochirurg, NVvN

- Dhr. drs. Maarten Liedorp, neuroloog, NVN

- Mevr. drs. Germine Mochel, neuroloog, NVN

- Mevr. dr. Akkie Rood, orthopedisch chirurg, NOV

- Dhr. dr. Erik Thoomes, fysiotherapeut en manueel therapeut, KNGF/NVMT

- Dhr. prof. dr. Jan Van Zundert, hoogleraar Pijngeneeskunde, NVA

- Dhr. Leen Voogt, ervaringsdeskundige, Nederlandse Vereniging van Rugpatiënten ‘de Wervelkolom’

KLANKBORDGROEP

- Mevr. Elien Nijland, ergotherapeut/handtherapeut, EN

- Mevr. Meimei Yau, oefentherapeut, VvOCM

Met ondersteuning van:

- Mevr. dr. Charlotte Michels, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Mevr. drs. Beatrix Vogelaar, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Naam lid werkgroep |

Hoofdfunctie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Carmen Vleggeert-Lankamp (voorzitter) |

Neurochirurg, Leiden Universitair Medisch Centrum, Leiden

|

* Medisch Manager Neurochirurgie Spaarne Gasthuis, Hoofdorp/ Haarlem, gedetacheerd vanuit LUMC (betaald) * Boardmember Eurospine, chair research committee |

*Niet anders dan onderzoeksleider in projecten naar etiologie van en uitkomsten in het CRS. |

Geen actie |

|

Akkie Rood |

Orthopedisch chirurg, Sint Maartenskliniek, Nijmegen |

Lid NOV, DSS, NvA |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Erik Thoomes |

Fysio-Manueel therapeut / praktijkeigenaar, Fysio-Experts, Hazerswoude |

*Promovendus / wetenschappelijk onderzoeker Universiteit van Birmingham, UK,School of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation Sciences, |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Germine Mochel |

Neuroloog, DC klinieken (loondienst) |

Lid werkgroep pijn NVN Lid NHV en VNHC |

*Dienstverband bij DC klinieken, alwaar behandeling/diagnostiek patiënten CRS

|

Geen actie |

|

Jan Van Zundert |

*Anesthesioloog-pijnspecialist. |

Geen |

Geen financiering omtrent projecten die betrekking hebben op cervicaal radiculair lijden (17 jaar geleden op CRS onderwerk gepromoveerd, nadien geen PhD CRS-projecten begeleidt).

|

Geen actie |

|

Leen Voogt |

*Ervaringsdeskundige CRS. *Voorzitter Nederlandse Vereniging van Rugpatiënten 'de Wervelkolom' (NVVR) |

Vrijwilligerswerk voor de patiëntenvereniging (onbetaald). |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Maarten Liedorp |

Neuroloog in loondienst (0.6 fte), ZBC Kliniek Lange Voorhout, Rijswijk |

*lid oudergeleding MR IKC de Piramide (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Martine van Bilsen |

Neurochirurg, Radboudumc, Nijmegen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Ruben Dammers |

Neurochirurg, ErasmusMC, Rotterdam |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Naam lid klankbordgroep |

Hoofdfunctie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Meimei Yau |

Praktijkhouder Yau Oefentherapeut, Oefentherapeut Mensendieck, Den Haag. |

Geen |

Kennis opdoen, informatie/expertise uitwisselen met andere disciplines, oefentherapeut vertegenwoordigen. KP register |

Geen actie |

|

Vera Keil |

Radioloog, AmsterdamUMC, Amsterdam. Afgevaardigde NVvR Neurosectie |

Geen |

Als radioloog heb ik natuurlijk een interesse aan een sterke rol van de beeldvorming. |

Geen actie |

|

Elien Nijland |

Ergotherapeut/hand-ergotherapeut (totaal 27 uur) bij Treant zorggroep (Bethesda Hoogeveen) en Refaja ziekenhuis (Stadskanaal) |

Voorzitter Adviesraad Hand-ergotherapie (onbetaald) |

|

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door een afgevaardigde van de Nederlandse Vereniging van Rugpatiënten ‘de Wervelkolom’ te betrekken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen (zie kop ‘Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten’). De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Nederlandse Vereniging van Rugpatiënten ‘de Wervelkolom’ en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Postoperatief beleid - Behandeling en werkhervatting bij CRS (2 PICO’s) |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet en het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met CRS. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door Ergotherapie Nederland, het Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap, Nederlandse Vereniging van Ziekenhuizen, Nederlandse Vereniging van Revalidatieartsen, Vereniging van Oefentherapeuten Cesar en Mensendieck, Zorginstituut Nederland, Zelfstandige Klinieken Nederland, via enquête. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

NHG, 2018. NHG-Standaard Pijn (M106). Published: juni 2018. Laatste aanpassing: Laatste aanpassing: september 2023. Link: https://richtlijnen.nhg.org/standaarden/pijnhttps://richtlijnen.nhg.org/standaarden/pijn

NVN, 2020. Richtlijn Lumbosacraal Radiculair Syndroom (LRS). Beoordeeld: 21-09-2020. Link: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/lumbosacraal_radiculair_syndroom_lrs/startpagina_-_lrs.html

Radhakrishnan K, Litchy WJ, O'Fallon WM, Kurland LT. Epidemiology of cervical radiculopathy. A population-based study from Rochester, Minnesota, 1976 through 1990. Brain. 1994 Apr;117 ( Pt 2):325-35. doi: 10.1093/brain/117.2.325. PMID: 8186959.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Literature search strategy

Algemene informatie

|

Cluster/richtlijn: Cervicaal Radiculair Syndroom |

|

|

Uitgangsvraag/modules: Wat is het advies post-operatief ten aanzien van belastbaarheid van de nek? |

|

|

Database(s): Ovid/Medline, Embase.com |

Datum: 17-08-2022 |

|

Periode: 1990 - heden |

Talen: Engels, Nederlands |

|

Literatuurspecialist: Miriam van der Maten |

|

|

BMI-zoekblokken: voor verschillende opdrachten wordt (deels) gebruik gemaakt van de zoekblokken van BMI-Online https://blocks.bmi-online.nl/ Bij gebruikmaking van een volledig zoekblok zal naar de betreffende link op de website worden verwezen. |

|

|

Toelichting: Voor deze vraag is gezocht op de elementen:

|

|

|

Te gebruiken voor richtlijnen tekst: Nederlands In de databases Embase.com en Ovid/Medline is op 17 augustus 2022 met relevante zoektermen gezocht naar systematische reviews en RCT over het advies post-operatief ten aanzien van belastbaarheid van de nek. De literatuurzoekactie leverde 382 unieke treffers op.

Engels On the 17th of August 2022, relevant search terms were used to search for systematic reviews and RCT about the advice regarding postoperative activity of the neck in the databases Embase.com and Ovid/Medline. The search resulted in 382 unique hits. |

|

Zoekopbrengst

|

|

EMBASE |

OVID/MEDLINE |

Ontdubbeld |

|

SRs |

102 |

104 |

147 |

|

RCT |

109 |

206 |

235 |

|

Totaal |

211 |

310 |

382 |

Zoekstrategie

Embase.com

|

No. |

Query |

Results |

|

#12 |

#8 AND #10 NOT #11 = RCT |

109 |

|

#11 |

#8 AND #9 = SR |

102 |

|

#10 |

'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR random*:ti,ab OR (((pragmatic OR practical) NEAR/1 'clinical trial*'):ti,ab) OR ((('non inferiority' OR noninferiority OR superiority OR equivalence) NEAR/3 trial*):ti,ab) OR rct:ti,ab,kw |

1839814 |

|

#9 |

'meta analysis'/exp OR 'meta analysis (topic)'/exp OR metaanaly*:ti,ab OR 'meta analy*':ti,ab OR metanaly*:ti,ab OR 'systematic review'/de OR 'cochrane database of systematic reviews'/jt OR prisma:ti,ab OR prospero:ti,ab OR (((systemati* OR scoping OR umbrella OR 'structured literature') NEAR/3 (review* OR overview*)):ti,ab) OR ((systemic* NEAR/1 review*):ti,ab) OR (((systemati* OR literature OR database* OR 'data base*') NEAR/10 search*):ti,ab) OR (((structured OR comprehensive* OR systemic*) NEAR/3 search*):ti,ab) OR (((literature NEAR/3 review*):ti,ab) AND (search*:ti,ab OR database*:ti,ab OR 'data base*':ti,ab)) OR (('data extraction':ti,ab OR 'data source*':ti,ab) AND 'study selection':ti,ab) OR ('search strategy':ti,ab AND 'selection criteria':ti,ab) OR ('data source*':ti,ab AND 'data synthesis':ti,ab) OR medline:ab OR pubmed:ab OR embase:ab OR cochrane:ab OR (((critical OR rapid) NEAR/2 (review* OR overview* OR synthes*)):ti) OR ((((critical* OR rapid*) NEAR/3 (review* OR overview* OR synthes*)):ab) AND (search*:ab OR database*:ab OR 'data base*':ab)) OR metasynthes*:ti,ab OR 'meta synthes*':ti,ab |

733409 |

|

#8 |

#5 AND #6 AND #7 AND ([english]/lim OR [dutch]/lim) AND [1990-2022]/py NOT ('conference abstract'/it OR 'editorial'/it OR 'letter'/it OR 'note'/it) NOT (('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp) |

929 |

|

#7 |

'head movement'/exp OR 'exercise'/exp OR 'physical activity, capacity and performance'/exp OR 'physical activity'/exp OR 'physical inactivity'/exp OR ((activit* NEAR/3 (limitat* OR restrict*)):ti,ab,kw) OR 'restriction protocol*':ti,ab,kw OR physical:ti,ab,kw OR exercise*:ti,ab,kw OR move*:ti,ab,kw OR restriction*:ti,ab,kw OR limitation*:ti,ab,kw OR advice:ti,ab,kw OR recommend*:ti,ab,kw OR distress:ti,ab,kw OR 'daily life activity'/exp OR ((daily NEAR/5 activit*):ti,ab,kw) |

4487162 |

|

#6 |

'aftercare'/exp OR followup:ti,ab,kw OR 'follow up':ti,ab,kw OR 'perioperative period'/exp OR 'postoperative complication'/exp OR 'postoperative period'/exp OR postoperati*:ti,ab,kw OR 'post-operat*':ti,ab,kw OR postsurg*:ti,ab,kw OR 'post-surg*':ti,ab,kw OR 'perioperat*':ti,ab,kw |

3826926 |

|

#5 |

#3 OR #4 |

11699 |

|

#4 |

((anterior NEAR/2 cervical NEAR/2 (foraminotomy OR microforaminotomy)):ti,ab,kw) OR 'anterior cervical discectomy'/exp OR 'anterior cervical discectomy and fusion'/exp OR cadf:ti,ab,kw OR cadp:ti,ab,kw OR acdf:ti,ab,kw OR ((anterior NEAR/2 cervical NEAR/2 (dis*ectom* OR 'disc fusion' OR microdiscectom*)):ti,ab,kw) OR 'foraminotomy'/exp OR 'degenerative cervical disc':ti,ab,kw |

6547 |

|

#3 |

#1 AND #2 |

6466 |

|

#2 |

'surgery'/exp OR 'surgery'/lnk OR surgical:ti,ab,kw OR surger*:ti,ab,kw OR operation*:ti,ab,kw OR operative:ti,ab,kw |

7143152 |

|

#1 |

'cervicobrachial neuralgia'/exp/mj OR cervicobrachialgia:ti,ab,kw OR ((radiculalgia:ti,ab,kw OR radiculitis:ti,ab,kw OR radiculitides:ti,ab,kw OR radiculopath*:ti,ab,kw OR polyradiculopath*:ti,ab,kw OR neuralgia:ti,ab,kw OR 'herniated disc*':ti,ab,kw OR hernia:ti,ab,kw OR ((radicular NEAR/3 (pain* OR neuralgia* OR symptom*)):ti,ab,kw) OR (('nerve root' NEAR/3 (pain* OR inflammation* OR disorder* OR compression* OR avulsion* OR impingement)):ti,ab,kw)) AND ('cervical spine'/exp OR 'neck'/exp OR cervical:ti,ab,kw OR cervico*:ti,ab,kw OR neck:ti,ab,kw)) OR (('radicular pain'/exp/mj OR 'radiculopathy'/exp/mj) AND ('cervical spine'/exp OR 'neck'/exp OR cervical:ti,ab,kw OR cervico*:ti,ab,kw OR neck:ti,ab,kw)) |

10847 |

Ovid/Medline

|

# |

Searches |

Results |

|

15 |

13 or 14 |

310 |

|

14 |

(10 and 12) not 13 = RCT |

206 |

|

13 |

10 and 11 = SR |

104 |

|

12 |

exp randomized controlled trial/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or random*.ti,ab. or rct?.ti,ab. or ((pragmatic or practical) adj "clinical trial*").ti,ab,kf. or ((non-inferiority or noninferiority or superiority or equivalence) adj3 trial*).ti,ab,kf. |

1538278 |

|

11 |

meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (metaanaly* or meta-analy* or metanaly*).ti,ab,kf. or systematic review/ or cochrane.jw. or (prisma or prospero).ti,ab,kf. or ((systemati* or scoping or umbrella or "structured literature") adj3 (review* or overview*)).ti,ab,kf. or (systemic* adj1 review*).ti,ab,kf. or ((systemati* or literature or database* or data-base*) adj10 search*).ti,ab,kf. or ((structured or comprehensive* or systemic*) adj3 search*).ti,ab,kf. or ((literature adj3 review*) and (search* or database* or data-base*)).ti,ab,kf. or (("data extraction" or "data source*") and "study selection").ti,ab,kf. or ("search strategy" and "selection criteria").ti,ab,kf. or ("data source*" and "data synthesis").ti,ab,kf. or (medline or pubmed or embase or cochrane).ab. or ((critical or rapid) adj2 (review* or overview* or synthes*)).ti. or (((critical* or rapid*) adj3 (review* or overview* or synthes*)) and (search* or database* or data-base*)).ab. or (metasynthes* or meta-synthes*).ti,ab,kf. |

612107 |

|

10 |

limit 9 to ((english language or dutch) and yr="1990 -Current") |

1233 |

|

9 |

8 not (comment/ or editorial/ or letter/ or ((exp animals/ or exp models, animal/) not humans/)) |

1327 |

|

8 |

5 and 6 and 7 |

1341 |

|

7 |