Dorsale behandelingen

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van de dorsale foraminotomie in vergelijking met de anterieure discectomie?

Aanbeveling

Baseer de keuze voor anterieure of dorsale benadering op basis van patiëntkarakteristieken (bijvoorbeeld patiënten die beroepsmatig hun stem gebruiken) en voorkeur van patiënt en chirurg. De werkgroep acht de benaderingen gelijkwaardig.

Overweeg bij patiënten met persisterend CRS (met congruente MRI-afwijking) na eerdere anterieure discectomie een dorsale foraminotomie te verrichten, mits doorbouw van bot na anterieure benadering is aangetoond. Eveneens kan een anterieure benadering overwogen worden indien een dorsale foraminotomie niet tot afdoende decompressie heeft geleid.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Het doel van deze uitgangsvraag was om te achterhalen wat de plaats is van dorsale foraminotomie in vergelijking met anterieure discectomie in de behandeling van patiënten met een cervicaal radiculair syndroom. Er zijn in totaal vier RCTs (Ebrahim, 2011; Ruetten, 2008; Wirth, 2000; Broekema, 2022) geïncludeerd met twee vergelijkingen. Samenvattend kunnen andere studies leiden tot nieuwe inzichten. Daarom kunnen er op basis van de literatuur alleen geen harde conclusies geformuleerd worden.

• PCF versus ACD/ACDF/ACDP

Voor de vergelijking tussen posterieure cervicale foraminotomie (PCF) en anterieure cervicale discecotomie (met fusie) (ACD/ACDF/ACDP) werd voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten pijn en disability een zeer lage bewijskracht gevonden. Posterieure cervicale foraminotomie lijkt te resulteren in een iets grotere verbetering van de Odom criteria in vergelijking met anterieure cervicale discectomie (met fusie).

• PCF versus ACF

Voor de vergelijking tussen posterieure cervicale foraminotomie en anterieure cervicale foraminotomie werd voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten pijn en disability geen bewijs gevonden.

De literatuur toont geen verschil in uitkomsten tussen de behandeling van een unilateraal radiculair syndroom met ACD(F) of PCF. Een voorkeur op basis van de literatuur is wat betreft de werkgroep dan ook niet te geven. De verrichte RCT’s over dit onderwerp zijn niet gepowered om andere verschillen (bijvoorbeeld in complicaties) tussen deze twee operatietechnieken te tonen. Gezien de verschillen in techniek, is het logisch dat een ACDF vaker tot een postoperatieve dysfagie leidt en een PCF tot meer wondinfecties leidt. Dit wordt wel gesuggereerd door de resultaten van de geïncludeerde studies (Broekema, 2022; Ruetten, 2008; Wirth, 2000).

Een ander verschil in techniek is het nastreven van fusie bij de ACD(F), wat niet gebeurt bij PCF. Indien hierbij een implantaat geplaatst wordt, maakt dit de ACDF duurder dan de PCF (wegens de kosten gerelateerd aan het implantaat).

Het theoretische voordeel van het verwijderen van de degeneratieve discus, is dat het betreffende segment fuseert en in de toekomst mogelijk minder kans geeft op compressiesyndromen. Daarentegen zorgt deze fusie mogelijk voor toegenomen belasting van de boven en ondergelegen discus. De vraag blijft of dit daadwerkelijk tot toename van klinische symptomen door degeneratie van deze boven- en ondergelegen disci leidt of dat dit zonder de fusie ook gebeurt (Hilibrand, 2004; Yang, 2022). Tevens geeft het gebruik van een implantaat kans op mogelijke hardware failure, iets wat overigens niet uit de geïncludeerde studies blijkt (Broekema, 2022; Ruetten, 2008; Wirth, 2000). De werkgroep is van mening dat deze theoretische voor- en nadelen onvoldoende zijn om voorkeur voor de ACD(F) of PCF uit te kunnen spreken. Met betrekking tot een unilateraal radiculair syndroom kunnen beide technieken gekozen worden. Bij multilevel CRS zijn er geen studies van goede kwaliteit verricht. Enkele retrospectieve studies geven aanwijzingen dat de resultaten tussen beide operaties overeenkomen (Lee, 2017; Ng, 2022). Wel wordt een langere opnameduur en een groter aantal infecties gezien bij PCF dan bij ACD(F) (Lee, 2017; Ng, 2022). Eveneens kan een anterieure benadering overwogen worden indien een dorsale foraminotomie niet tot afdoende decompressie heeft geleid.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Qua ervaren pijn, hersteltijd en/of complicaties laat de literatuur geen klinisch relevante verschillen zien tussen de anterieure en posterieure benadering. Wel kennen de beide benaderingen verschillende (kleine) operatie gerelateerde risico’s die een voorkeur voor de ene of andere techniek kunnen geven. Voor patiënten is dan ook een goede en volledige toelichting van beide operaties essentieel.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Gezien bij PCF geen gebruik wordt gemaakt van een cage en bij de ACDF wel, lijkt op korte termijn de PCF goedkoper in vergelijking met ACDF (Broekema, 2022). Echter ontbreken kosteneffectiviteitsstudies over dit onderwerp en zijn ook lange termijn resultaten onbekend. Op lange termijn kunnen mogelijk beide operatietechnieken leiden tot re-operaties die de kosteneffectiviteit doen veranderen. Zo kan de ACDF in theorie leiden tot adjacent segment disease en de PCF tot same level pathologie. Ook omvatten de RCT’s relatief kleine studiepopulaties met een unilateraal en single level disease, met een relatief korte follow-up. Dit maakt de kosteneffectiviteit van beide operaties een hypothetisch onderwerp. De werkgroep is daardoor van mening dat voorkeur voor het een of ander niet op basis van kosten kan geschieden.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

In de huidige praktijk wordt de ACDF vaker uitgevoerd dan de PCF. De werkgroep verwacht echter geen grote problemen met aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie van deze aanbeveling. Neurochirurgen die kennis hebben gemaakt met beide technieken gedurende hun opleiding, zullen hiervoor openstaan en tot middelen beschikken om beide operatietechnieken uit te voeren.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Op basis van de bestaande literatuur kan de werkgroep geen sterke aanbevelingen doen ten aanzien van de plaats van de dorsale foraminotomie in vergelijking met de anterieure discectomie bij patiënten met een cervicaal radiculair syndroom vast te stellen. Gezien de lage bewijskracht en overwegingen, acht de werkgroep beide benaderingen gelijkwaardig.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Momenteel wordt de anterieure discectomie steeds vaker toegepast in de praktijk. Reeds was aanbevolen dat anterieure benadering de voorkeur verdient (NVvN, 2010). Echter kennen zowel de dorsale als anterieure benadering voor- en nadelen. Anterieur kan leiden tot heesheid/stemproblematiek welke ongewenst is bij bepaalde beroepsgroepen. Hierdoor kan een dorsale foraminotomie de voorkeur hebben. Bij de dorsale benadering wordt vaak alleen indirecte decompressie verkregen in het geval van ossale compressie. Alleen vrije, lateraal gelegen discusfragmenten kunnen verwijderd worden.De vraag is echter of de uitgesproken voorkeur voor anterieure discectomie nog terecht is.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Conclusions PCF versus ACD/ACDF/ACDP

1.1. Pain (critical)

|

moderate GRADE |

Dorsal foraminotomy probably results in little to no difference in arm pain and neck pain when compared with anterior cervical discectomy (with fusion) in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Source: Broekema, 2022 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of dorsal foraminotomy on radicular pain when compared with anterior cervical discectomy (with fusion) in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Source: Ruetten, 2008; Wirth, 2000 |

1.2. Disability (critical)

|

Low GRADE |

Dorsal foraminotomy may result in little to no difference in disability when compared with anterior cervical discectomy (with fusion in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Source: Broekema, 2022 |

1.3. Odom criteria (important)

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that dorsal foraminotomy increases the Odom criteria when compared with anterior cervical discectomy (with fusion) in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Source: Broekema, 2022 |

1.4. Reoperations (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of dorsal foraminotomy on reoperations when compared with anterior cervical discectomy (with fusion) in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Source: Broekema, 2022; Ruetten, 2008; Wirth, 2000 |

1.5. Complications (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of dorsal foraminotomy on complications when compared with anterior cervical discectomy (with fusion) in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Source: Broekema, 2022; Ruetten, 2008; Wirth, 2000 |

1.6. Work status (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of dorsal foraminotomy on work status when compared with anterior cervical discectomy (with fusion) in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Source: Broekema, 2022; Wirth, 2000 |

1.7. Quality of life (important)

|

Moderate GRADE |

Dorsal foraminotomy probably results in little to no difference in quality of life when compared with anterior cervical discectomy (with fusion) in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Source: Broekema, 2022 |

1.8. Use of pain medication (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of dorsal foraminotomy on use of pain medication when compared with anterior cervical discectomy (with fusion) in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Source: Wirth, 2000 |

1.9. Patient satisfaction (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of dorsal foraminotomy on patient satisfaction when compared with anterior cervical discectomy (with fusion) in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Source: Broekema, 2022; Ruetten, 2008 |

1.10. Adjacent disc disease (important)

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of dorsal foraminotomy on adjacent disc disease when compared with anterior cervical discectomy (with fusion) in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Source: - |

2. Conclusions PCF versus ACF

2.2. Odom criteria (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of dorsal foraminotomy on Odom criteria when compared with anterior cervical foraminotomy in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Source: Ebrahim, 2011 |

2.3. Reoperations (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of dorsal foraminotomy on reoperations when compared with anterior cervical foraminotomy in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Source: Ebrahim, 2011 |

2.6. Patient satisfaction (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of dorsal foraminotomy on patient satisfaction when compared with anterior cervical foraminotomy in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Source: Ebrahim, 2011 |

2.1 Pain (critical); 2.7. Disability (critical); 2.8. Adjacent disc disease (important); 2.9. Quality of life (important); 2.10. Use of pain medication

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of dorsal foraminotomy on pain, disability, complications, adjacent disc disease, work status, quality of life, and use of pain medication when compared with anterior cervical foraminotomy in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Source: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Broekema (2022) performed a multicenter investigator-blinded noninferiority randomized controlled trial to assess the noninferiority of posterior versus anterior surgery in patients with cervical foraminal radiculopathy with regard to clinical outcomes after 1 year. Patients with an age between 18 and 80 years with 1-sided single-level cervical foraminal radiculopathy due to soft disc herniation or spondylotic changes requiring surgical decompression were included.

In total, 132 patients were randomized to posterior cervical foraminotomy (PCF) and 133 patients to anterior cervical discectomy with fusion (ACDF). Groups were comparable at baseline except for sex distribution (PCF-group: 55% Female vs. ACDF-group: 47% Female), radiological characteristics (PCF-group: 48% vs. ACDF-group: 57% combined discogenic and spondylotic) and comorbidities (PCF-group: 55% vs. ACDF-group: 46%). After 1 year of follow-up, 110 patients who received PCF and 118 patients who received ACDF were included in the analysis. Outcomes of interest were arm- and neck pain, disability, Odom criteria, reoperation, complications, work status, quality of life and patient satisfaction. For the Odom score, 98 patients treated with PCF and 106 patients treated with ACDF were included in the analysis.

Ebrahim (2011) performed a prospective randomized comparative study to assess clinical and radiological outcomes for the posterior (PCF) and anterior cervical foraminotomy (ACF) procedures in the treatment of patients with unilateral cervical radiculopathy. Patients with unilateral cervical radiculopathy that had not responded to conservative treatment for more than 6 weeks with imaging studies confirming pathoanatomic features (unilateral posterolateral disc herniation or osteophyte compression and foraminal stenosis) corresponding to the clinical symptoms without previous cervical spine surgery and no significant spondylotic stenosis causing spinal cord compromise were included. Exclusion criteria were cervical myelopathy, imaging studies showing central or paracentral stenosis, deformity or instability and previous cervical spine surgery. In total, 15 patients underwent PCF, and 15 patients underwent ACF. Groups were probably comparable at baseline. Outcomes of interest were neck and radicular pain, Odom criteria, complications, work status, and patient satisfaction.

Ruetten (2008) performed a prospective, randomized, controlled study to assess the results of cervical discectomy in lateral disc herniations in full-endoscopic technique via posterior foraminotomy and the conventional microsurgical ACDF. Patients with unilateral radiculopathy with arm pain, in MRI/CT lateral or foraminal localized monosegmental disc herniation of segments C2-C3-C7-Th1 were included. Besides, patients with cranio-caudal sequestering and patients with secondary foraminal stenosis were included as long as the lateral localization was maintained. Exclusion criteria were patients with clear instabilities or deformities, medial localization of disc herniation and isolated neck pain or foraminal stenosis without disc herniation. In total, 100 patients were randomized to PCF and 100 patients to ACDF. After 2 years of follow-up, 175 patients, of which 89 patients received PCF and 86 patients underwent ACDF, were included in the analysis. Groups were comparable at baseline. The outcomes of interest were arm- and neck pain and complications.

Wirth (2000) performed a randomized, prospective study to assess the efficacy of surgical procedures for the treatment of cervical radiculopathy. Patients with cervical radiculopathy caused by a unilateral herniated cervical disc with single-level disease were included. Exclusion criteria were patients with signs of myelopathy and additional degenerative changes on plain radiography. In total, 74 patients were randomized to PCF (n=23) or ACD/ACDF/ACDP (n=51). However, two patients (one in PCF-group and one in ACD-group) declined surgery. Therefore, 22 patients underwent PCF and 50 patients underwent ACD/ACDF/ACDP. Groups were comparable at baseline. Follow-up occurred at 2 months (office visit) and a delayed phone follow-up was performed at 60 months on average. Outcomes of interest were pain, reoperation, complications, work status, and use of pain medication.

Table 1. Description of included studies

|

Study |

Intervention |

Comparator |

Follow-up |

Outcomes |

||

|

|

Characteristics |

Intervention |

Characteristics |

Control |

|

|

|

Broekema, 2022 |

Arm 1 (n=119) Mean age (SD): 51.6 ± 8.5 years Sex: 55% Female |

PCF |

Arm 2 (n=124) Mean age (SD): 51.0 ± 8.3 years Sex:47% Female |

ACDF |

12 months |

Pain, disability, Odom criteria, reoperation, complications, work status, quality of life, patient satisfaction |

|

Ebrahim, 2011 |

Arm 1 (n=15) Mean age (range): 46.7 years (29 to 62 years) Sex: 60% Female |

PCF |

Arm 2 (n=15) Mean age (range): 42 years (31 to 52 years) Sex: 47% Female |

ACF |

Up to 2 years: PCF: 15.4 months (5-24 months) ACF: 12.5 months (6-24 months) |

Pain, Odom criteria, reoperation, complications, work status, patient satisfaction |

|

Ruetten, 2008 |

Arm 1 (n=89) Mean age (range): NR Sex: NR |

PCF |

Arm 2 (n=86) Mean age (range): NR Sex: NR |

ACDF |

2 years |

Pain, complications, reoperation, patient satisfaction |

|

Wirth, 2000 |

Arm 1 (n=22) Median age (range): 43.8 years (30–66) Sex: 59% Female |

PCF |

Arm 2 (n=25) Median age (range): 45.0 years (30–67) Sex:48% Female

Arm 3 (n=25 ) Mean age (range): 41.7 years (28–63) Sex:44% Female |

ACD

ACDF |

2 months and at 60 months on average: PCF: 53 months ACD: 56 months ACDF: 69 months |

Pain, reoperation, complications, work status, use of pain medication |

Abbreviations: PCF=posterior cervical foraminotomy; ACD=anterior cervical discectomy; ACDF=anterior cervical discectomy with fusion; ACF=anterior cervical foraminotomy

Results

1. PCF versus ACD/ACDF/ACDP (Broekema, 2022; Ruetten, 2008; Wirth, 2000)

1.1. Pain (critical)

1.1.1 Arm pain

Broekema (2022) reported that the 1-year postoperative VAS score for arm pain was 18.6 (SD=22.9) in the PCF-group as compared to 15.8 (SD=23.7) in the ACDF-group. This resulted in a mean difference of 2.80 (95%CI -3.06 to 8.66), which was not clinically relevant.

Ruetten (2008) reported that the 2-year postoperative VAS score for arm pain was 7 in the PCF-group and 8 in the ACDF-group. However, since no standard deviations were presented, no GRADE assessment could be performed.

1.1.2. Neck pain

Broekema (2022) reported that the 1-year postoperative VAS score for neck pain was 24.4 (SD=27.5) in the PCF-group as compared to 21.7 (SD=26.1) for the ACDF-group. This resulted in a mean difference of 2.70 (95%CI -4.05 to 9.45), which was not clinically relevant.

Ruetten (2008) reported that the 2-year postoperative VAS score for neck pain was 16 in the PCF-group and 17 in the ACDF-group. However, since no standard deviations were presented, no GRADE assessment could be performed.

1.1.3. Radicular pain

Ruetten (2008) reported the radicular pain after 2 years. No radicular pain was reported by 79 of the 89 patients (89%) in the PCF-group and by 76 of the 86 patients (88%) in the ACDF-group. This resulted in a relative risk of 1.00 (95%CI 0.90 to 1.12), which was not clinically relevant.

Wirth (2000) reported the pain improvement (defined as complete relief or partial improvement of radicular pain) peri-operative, at 2 months and at 60 months on average.

• Peri-operative

All patients had 100% pain improvement on the first post-operative day. Nine of the 22 patients (41%) in the PCF-group had a complete relief of pain as compared to 24 of the 50 patients (48%) in the ACD/ACDF/ACDP/ACDP-group. A relative risk of 0.85 (95%CI 0.48 to 1.52) was found, which was clinically relevant favoring ACD/ACDF/ACDP/ACDP.

• 2 months follow-up

At 2 months, the pain improvement declined to 98% in the ACD/ACDF/ACDP-group, while in the PCF-group, it remained 100%. Seventeen of the 22 patients (77%) in the PCF-group reported complete pain relief at 2 months, as compared to 37 of the 50 patients (74%) in the ACD/ACDF/ACDP-group. This resulted in a relative risk of 1.04 (95%CI 0.79 to 1.38), which was not clinically relevant.

• 60 months follow-up

At telephone follow-up, the pain improvement remained 100% for patients in the PCF-group, while it declined to 97% in the ACD/ACDF/ACDP-group. Complete pain relief was reported by seven of the 14 patients (50%) in the PCF-group at 53 months and 16 of the 29 patients (55%) in the ACD/ACDF/ACDP-group at 62.5 months on average. This resulted in a relative risk of 0.91 (95%CI 0.49 to 1.68), which was not clinically relevant.

1.2. Disability (critical)

Broekema (2022) reported disability with the Neck Disability Index (NDI). The NDI score was 17.6 (SD=14.6) in the PCF-group as compared to 19.2 (SD=16.5) in the ACDF-group. This resulted in a mean difference of -1.60 (95%CI -5.51 to 2.31), which was not clinically relevant.

1.3. Odom criteria (important)

Broekema (2022) reported the proportion of patients with a successful outcome at 1-year follow-up with a score of excellent or good on the modified Odom criteria 4-point rating scale. For the PCF-group, 86 of the 98 patients (88%) had a successful outcome as compared to 81 of the 106 patients (76%) in the ACF-group. This resulted in a relative risk of 1.15 (95%CI 1.01 to 1.31), which was clinically relevant favoring PCF.

1.4. Reoperations (important)

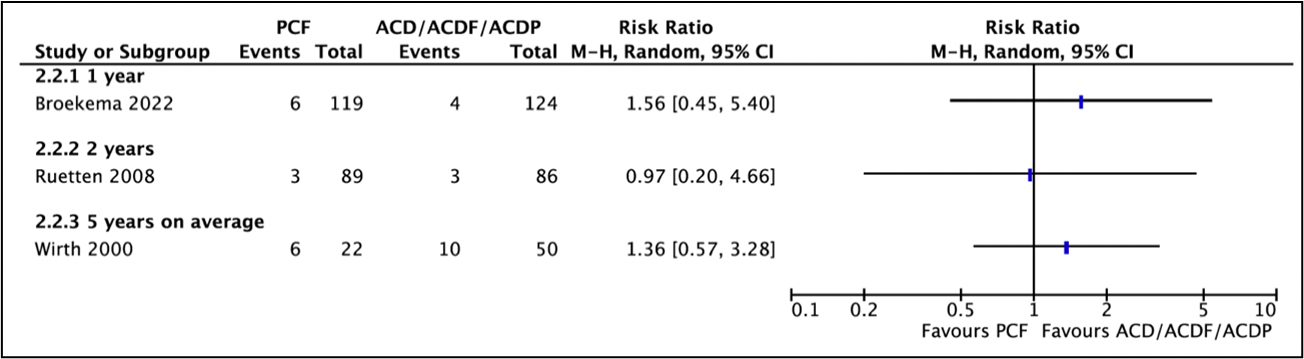

Three studies reported reoperations (Broekema, 2022; Wirth, 2000; Ruetten, 2008) (Figure 1).

Broekema (2022) reported in the PCF-group, 6 of the 119 patients (5%) had a reoperation as compared to 4 of the 124 patients (3%) in the ACDF-group. This resulted in a relative risk of 1.56 (95%CI 0.45 to 5.40), which was clinically relevant favoring ACDF.

Ruetten (2008) reported recurrences/revisions. Three of the 89 patients (3.4%) in the PCF-group and three of the 86 patients (3.5%) in the ACDF-group had recurrences/revisions. This resulted in a relative risk of 0.97 (95%CI 0.20 to 4.66), which was not clinically relevant.

Wirth (2020) reported that reoperation was required in 6 of the 22 patients (27%) in the PCF-group and in 10 of the 50 patients (20%) in the ACD/ACDF/ACDP-group. This resulted in a relative risk of 1.36 (95%CI 0.57 to 3.28), which was clinically relevant favoring ACD/ACDF/ACDP.

Figure 1. Forest plot for reoperation.

1.5. Complications (important)

Three studies reported complications (Broekema, 2022; Wirth, 2000; Ruetten, 2008)

Broekema (2022) reported overall adverse events and serious adverse events at 1 year. Besides, the serious surgery-associated adverse events dysphagia, wound infection, and hoarseness were reported.

- Adverse events

Thirty-six of the 119 patients (30%) in the PCF-group and 35 of the 124 patients (28%) in the ACDF-group reported adverse events (Broekema, 2022). This resulted in a relative risk of 1.07 (95%CI 0.72 to 1.59), which was not clinically relevant.

- Serious adverse events

Thirteen of the 119 patients (11%) in the PCF-group and 17 of the 124 patients (14%) in the ACDF-group reported serious adverse events (Broekema, 2022). This resulted in a relative risk of 0.80 (95%CI 0.40 to 1.57), which was clinically relevant favoring PCF.

- Serious surgery-associated adverse events

Dysphagia or globus sensation was experienced by 1 of the 119 patients (0.8%) in the PCF-group as compared to 6 of the 124 patients (4.8%) in the ACDF-group (Broekema, 2022). This resulted in a relative risk of 0.17 (95%CI 0.02 to 1.42), which was clinically relevant favoring PCF.

Wound infections were experienced by 5 of the 119 patients (4.2%) in the PCF-group as compared to 2 of the 124 patients (1.6%) in the ACDF-group (Broekema, 2022). This resulted in a relative risk of 2.61 (95%CI 0.52 to 13.17), which was clinically relevant favoring ACDF.

Hoarseness was experienced by one of 119 patients (0.8%) in the PCF-group as compared to two of the 124 patients (1.6%) in the ACDF-group (Broekema, 2022). This resulted in a relative risk of 0.52 (95%CI 0.05 to 5.67), which was clinically relevant favoring PCF.

Ruetten (2008) reported perioperative complications. In the PCF-group, three patients had transient, dermatoma-related hypesthesia. In the ACDF-group, three patients experienced transient difficulty swallowing, one patient had surface hematoma and one patient had scar distortion which was cosmetically disruptive.

Wirth (2000) reported the perioperative complications new weakness and new numbness. New weakness was reported by 3 of the 22 patients (14%) in the PCF-group and by 4 of the 50 patients (8%) in the ACD/ACDF/ACDP-group. This resulted in a relative risk of 1.70 (95% CI 0.42 to 6.98), which was clinically relevant favoring ACD/ACDF/ACDP. New numbness was reported by 2 of the 22 patients (9%) in the PCF-group and in 3 of the 50 patients (6%) in the ACD/ACDF/ACDP-group. This resulted in a relative risk of 1.52 (95% CI 0.27 to 8.44), which was clinically relevant favoring ACD/ACDF/ACDP. No hoarseness was reported in the PCF- and ACD/ACDF/ACDP-group.

1.6. Work status (important)

Two studies reported about work status (Broekema, 2022; Wirth, 2000).

Broekema (2022) reported the Work Ability Index (Single-item) with higher scores indicating better work ability. The mean Work Ability Index was 6.7 (SD=2.3) in the PCF-group and 6.7 (SD=2.6) in the ACDF-group. This resulted in a mean difference of 0.0 (95%CI -0.62 to 0.62), which was not clinically relevant.

Wirth (2000) reported return to work at 2 months and at telephone follow-up of on average 60 months.

- 2 months follow-up

At 2-months, 20 of the 22 patients (91%) in the PCF-group and 45 of the 50 patients (90%) in the ACD/ACDF/ACDP-group returned to work. This resulted in a relative risk of 1.01 (95%CI 0.86 to 1.19), which was not clinically relevant.

- 60 months follow-up

At telephone follow-up, return to work was reported in 11 of the 14 patients (79%) in the PCF-group at 53 months and in 25 of the 29 patients (86%) in the ACD/ACDF/ACDP-group at 62.5 months on average. This resulted in a relative risk of 0.91 (95%CI 0.67 to 1.24), which was not clinically relevant.

1.7. Quality of life (important)

Broekema (2022) reported the quality of life with the EQ-5D. The mean EQ-5D score in the PCF-group was 0.84 (SD=0.15) as compared to 0.82 (SD=0.14) in the ACDF-group. This resulted in a mean difference of 0.02 (95%CI -0.02 to 0.06), which was not clinically relevant.

1.8. Use of pain medication (important)

Wirth (2000) reported the required postoperative analgesic medication (injections and oral medication). This was 15.9 (SD=12.6) for the PCF-group and 12.8 (SD=35.7) for patients in the ACD/ACDF/ACDP-group. This resulted in a mean difference of 3.10 (95% CI -8.11 to 14.31), which was clinically relevant favoring ACDF.

1.9. Patient satisfaction (important)

Two studies reported patient satisfaction (Broekema, 2022; Ruetten, 2008). Broekema (2022) reported that 70 of the 96 patients (73%) in the PCF-group were satisfied or very satisfied after 1 year follow-up as compared to 76 of the 99 patients (77%) in the ACDF-group. This resulted in a relative risk of 0.95 (95%CI 0.81 to 1.12), which was not clinically relevant.

Ruetten (2008) reported that 86 of the 89 patients (96%) in the PCF-group were satisfied as compared to 78 of the 86 patients (91%) in the ACDF-group. This resulted in a relative risk of 1.07 (95%CI 0.99 to 1.15), which was not clinically relevant.

1.10. Adjacent disc disease (important)

Not reported.

Level of evidence of the literature

1.1.1 The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure arm pain started as high because it was based on a RCT and was downgraded by one level to moderate because of concerns about blinding (-1, risk of bias).

1.1.2 The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure neck pain started as high because it was based on a RCT and was downgraded by one levels to moderate because of concerns about blinding (-1, risk of bias).

1.1.3 The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure radicular pain started as high because it was based on a RCT and was downgraded by three levels to very low because of concerns about randomization and blinding (-1, risk of bias) and the 95% confidence interval crossed the lines of no (clinically relevant) effect (-2, imprecision).

1.2 The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure disability started as high because it was based on a RCT and was downgraded by three levels to low because of concerns about blinding (-1, risk of bias) and crossing one border of clinical relevance (-1, imprecision).

1.3 The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure Odom criteria started as high because it was based on a RCT and was downgraded by two levels to low because of concerns about blinding (-1, risk of bias) and 95% confidence interval crossed the line of no (clinically relevant) effect (-1, imprecision).

1.4 The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure reoperations started as high because it was based on a RCT and was downgraded by three levels to very low because of concerns about randomization and blinding (-1, risk of bias) and the 95% confidence interval crossed the lines of no (clinically relevant) effect (-2, imprecision).

1.5 The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure complications started as high because it was based on a RCT and was downgraded by three levels to very low because of concerns about randomization and blinding (-1, risk of bias) and the 95% confidence interval crossed the lines of no (clinically relevant) effect (-2, imprecision).

1.6 The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure work status started as high because it was based on a RCT and was downgraded by three levels to very low because of concerns about randomization and blinding (-1, risk of bias) and the 95% confidence interval crossed the lines of no (clinically relevant) effect (-2, imprecision).

1.7 The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life started as high because it was based on a RCT and was downgraded by one level to moderate because of concerns about blinding (-1, risk of bias).

1.8 The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure use of pain medication started as high because it was based on a RCT and was downgraded by three levels to very low because of concerns about randomization and blinding (-1, risk of bias) and the optimal information size was not achieved (-2, imprecision).

1.9 The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure patient satisfaction started as high because it was based on a RCT and was downgraded by three levels to very low because of concerns about randomization and blinding (-1, risk of bias) and the 95% confidence interval crossed the lines of no (clinically relevant) effect (-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure adjacent disc disease was not assessed.

2. PCF versus ACF (Ebrahim, 2011)

2.1 Pain (critical)

2.1.1 Neck pain

Ebrahim (2011) reported that neck pain was resolved for 27.3% in the PCF-group and 50% in ACF-group at the postoperative follow-up of two years. Besides, a statistically significant difference in neck pain at time of discharge of 3.1 (SD=2.5) was demonstrated. However, since no absolute numbers were presented, no GRADE assessment could be performed.

2.1.2. Radicular pain

Ebrahim (2011) reported that radicular pain was resolved for 66.7% in the PCF-group and 73.3% in the ACF-group. However, since no absolute numbers were presented, no GRADE assessment could be performed.

2.2. Odom criteria (important)

Ebrahim (2011) reported that an excellent or good score on the Odom criteria was experienced in 14 of the 15 patients (93%) receiving either PCF or ACF. This resulted in a relative risk of 1.00 (95%CI 0.83 to 1.21), which is not clinically relevant.

2.3. Reoperations (important)

Ebrahim (2011) reported that reoperations were required in one of the 15 patients (6.7%) receiving either PCF or ACF. This resulted in a relative risk of 1.00 (95%CI 0.07 to 14.55), which is not clinically relevant.

2.4. Complications (important)

Ebrahim (2011) reported operative complications. For patients who underwent PCF, one patient experienced superficial wound infection and one patient had an intraoperative cerebrospinal fluid leak. Patients in the ACF-group did not experience permanent surgery-related morbidity; no cases of Horner’s syndrome or wound-related problems were reported. No GRADE assessment could be performed.

2.5. Work status (important)

Ebrahim (2011) reported that 12 of the 15 patients (80%) in the PCF-group returned to work or their baseline level of activity within 6 weeks postoperatively, while in the ACF-group this was percentage was achieved within 3 weeks postoperatively. However, since no data was provided at the same follow-up period, no GRADE assessment could be performed.

2.6. Patient satisfaction (important)

Ebrahim (2011) measured patient satisfaction with the patient satisfaction index (PSI). Fourteen of the 15 patients receiving either PCF or ACF were satisfied or very satisfied. This resulted in a relative risk of 1.00 (95%CI 0.83 to 1.21), which is not clinically relevant.

2.7. Disability (critical); 2.8. Adjacent disc disease (important); 2.9. Quality of life (important); 2.10. Use of pain medication

Not reported.

Level of evidence of the literature

2.2. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure Odom criteria started as high because it was based on a RCT and was downgraded by three levels to very low because of concerns about randomization and blinding (-1, risk of bias) and the 95% confidence interval crossed the lines of no (clinically relevant) effect (-2, imprecision).

2.3 The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure reoperations started as high because it was based on a RCT and was downgraded by three levels to very low because of concerns about randomization and blinding (-1, risk of bias) and the 95% confidence interval crossed the lines of no (clinically relevant) effect (-2, imprecision).

2.6 The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure patient satisfaction started as high because it was based on a RCT and was downgraded by three levels to very low because of concerns about randomization and blinding (-1, risk of bias) and the 95% confidence interval crossed the lines of no (clinically relevant) effect (-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures pain, disability, complications, adjacent disc disease, work status, quality of life, and use of pain medication were not assessed.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the effectiveness of the dorsal foraminotomy compared to the anterior discectomy in patients with CRS?

P: Patients with CRS (no myelopathy)

I: Dorsal foraminotomy (excluding laminectomy) (Posterior/Scoville)

C: Anterior discectomy (wide)

O: Pain, disability, Odom criteria (4-point rating scale), reoperations, complications (including dysphagia), adjacent disc disease (ADD), work status, quality of life, use of pain medication, patient satisfaction

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered pain and disability as critical outcome measures for decision making; and Odom criteria, reoperations, complications, adjacent disc disease, work status, quality of life, pain medication use, and patient satisfaction as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

- Pain: measured with visual analogue scale (VAS), McGill pain questionnaire, or numerical rating scale (NRS)

- Disability: measured with Neck Disability Index (NDI)

- Quality of life: measured with 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) or European Quality of Life - Five Dimension (EQ-5D)

For the other outcomes, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined the following minimal clinically (patient) important differences:

- Pain:

- Visual Analogue Scale (VAS, 0-10): ³1

- Numerical Rating Scale (NRS, 0-10): ³1

- Disability:

- Neck Disability Index (NDI, 0-50): ³5

For the other outcomes, the working group defined 10% as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for continuous outcomes and a RR of <0.91 or >1.1 for dichotomous outcomes. This decision was based on the minimal important change scores described in the article by Ostelo (2008), in accordance with the Dutch Lumbosacral Radicular syndrome guideline (NVN, 2020).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 24 August 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 340 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- systematic review and/or meta-analysis, with detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment, and results of individual studies available; randomized controlled trial (RCT); or other comparative studies;

- patients aged ≥ 18 years;

- studies including ≥ 20 patients (10 in each study arm);

- studies according to the PICO. Dorsal foraminotomy (excluding laminectomy) as an intervention, and described anterior discectomy as a comparison; and

- full-text English or Dutch language publication;

The search was updated for systematic reviews and RCTs on 16 January 2023 due to a new trial. A total of 5 new hits were found.

Initially, 28 studies were selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 26 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and two studies were included (Broekema, 2020; Broekema, 2022). The systematic review of Broekema (2020) contained three RCTs matching with the PICO (Ebrahim, 2011; Ruetten, 2008; Wirth, 2000) which were included besides the RCT of Broekema (2022).

Results

Four studies were included in the analysis of the literature (Ebrahim, 2011; Ruetten, 2008; Wirth, 2000; Broekema, 2022). Important study characteristics and results are summarized in table 1 and the evidence table. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias table.

Referenties

- Broekema AEH, Groen RJM, Simões de Souza NF, Smidt N, Reneman MF, Soer R, Kuijlen JMA. Surgical Interventions for Cervical Radiculopathy without Myelopathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020 Dec 16;102(24):2182-2196. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.20.00324. PMID: 32842045.

- Broekema AEH, Simões de Souza NF, Soer R, Koopmans J, van Santbrink H, Arts MP, Burhani B, Bartels RHMA, van der Gaag NA, Verhagen MHP, Tamási K, van Dijk JMC, Reneman MF, Groen RJM, Kuijlen JMA; FACET investigators. Noninferiority of Posterior Cervical Foraminotomy vs Anterior Cervical Discectomy With Fusion for Procedural Success and Reduction in Arm Pain Among Patients With Cervical Radiculopathy at 1 Year: The FACET Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 2023 Jan 1;80(1):40-48. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.4208. PMID: 36409485; PMCID: PMC9679957.

- Ebrahim KS, El-Shehaby A, Ahmed Darwish AF, Ma'moun E. Anterior or posterior foraminotomy for unilateral cervical radiculopathy. Pan Arab Journal of Neurosurgery. 2011 Oct;15(2):34

- Hilibrand AS, Robbins M. Adjacent segment degeneration and adjacent segment disease: the consequences of spinal fusion? Spine J. 2004 Nov-Dec;4(6 Suppl):190S-194S. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2004.07.007. PMID: 15541666.

- Lee DG, Park CK, Lee DC. Clinical and radiological results of posterior cervical foraminotomy at two or three levels: a 3-year follow-up. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2017 Dec;159(12):2369-2377. doi: 10.1007/s00701-017-3360-4. Epub 2017 Oct 23. PMID: 29063273.

- Ng MK, Kobryn A, Baidya J, Nian P, Emara AK, Ahn NU, Houten JK, Saleh A, Razi AE. Multi-Level Posterior Cervical Foraminotomy Associated With Increased Post-operative Infection Rates and Overall Re-Operation Relative to Anterior Cervical Discectomy With Fusion or Cervical Disc Arthroplasty. Global Spine J. 2022 Sep 2:21925682221124530. doi: 10.1177/21925682221124530. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36052872.

- Ruetten S, Komp M, Merk H, Godolias G. Full-endoscopic cervical posterior foraminotomy for the operation of lateral disc herniations using 5.9-mm endoscopes: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 Apr 20;33(9):940-8. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816c8b67. PMID: 18427313.

- Yang MJ, Riesenburger RI, Kryzanski JT. The use of intra-operative navigation during complex lumbar spine surgery under spinal anesthesia. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2022 Apr;215:107186. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2022.107186. Epub 2022 Feb 24. PMID: 35231677.Wirth FP, Dowd GC, Sanders HF, Wirth C. Cervical discectomy. A prospective analysis of three operative techniques. Surg Neurol. 2000 Apr;53(4):340-6; discussion 346-8. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(00)00201-9. PMID: 10825519.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Broekema, 2022 |

Type of study: Multicenter investigator-blinded noninferiority randomized clinical trial

Setting and country: 9 hospitals in the Netherlands

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funded by Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMW). Conflicts of interest were reported (not serious)

|

Inclusion criteria: - Age between 18 and 80 years - Cervical foraminal stenosis due to a soft disc component causing monoradiculopathy of C4, C5, C6, or C7 and requiring decompression of neuroforamen - No response to conservative treatment for eight weeks or presence of progressive symptoms or signs of nerve root compression in the face of conservative treatment. - Soft disc/Spondylitic foraminal stenosis (determined by MRI and CT and/or right or left oblique Xray of the cervical spine) at the treatment level correlating to primary symptoms. - Psychosocially, mentally, and physically able to fully comply with this protocol, including adhering to scheduled visits, treatment plan, completing forms, and other study procedures. - Patient has sufficient mastery of the Dutch language to fill out the questionnaires. - Signed and dated informed consent document prior to any study-related procedures

Exclusion criteria: - Pure axial neck pain without radicular pain - Multisegmental CRS - Median located disc protrusion or osteophytic protrusion. - Foraminal compression of C8. - Spinal cord compression with clinical myelopathy. - Radiological myelopathy. - History of cervical spine surgery. - Malignant obesity (BMI > 30). - Osteoporosis / chronic use of corticosteroids. - ASA 4 and 5 patients (serious ill patients). - Pregnancy - Active malignancy - Abundant use of alcohol, drugs, narcotics and recreational drugs. - Contra-indications for anesthesia or surgery - Patient has used another investigational drug or device within the 30 days prior to surgery - Incapability to speak and write the Dutch language

N total at baseline: Intervention: 119 Control: 124

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I: 51.6 ± 8.5 C: 51.0 ± 8.3

Sex: I: 55% F C: 47% F

Radiological characteristics (combined discogenic and spondylotic) I: 57 (48%) C: 70 (57%)

Number of comorbidities I: 66 (55%) C: 57 (46%)

Groups comparable at baseline except for sex distribution, radiological characteristics and comorbidities. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Posterior surgery (posterior cervical foraminotomy)

Partial hemilaminectomy and foraminotomy of the involved level was performed. Soft disc herniations and osteophytes were removed when necessary. No additional plate fixation or postsurgical neck brace was applied in either technique

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): Anterior surgery (anterior cervical discectomy with fusion)

After discectomy, with reduction of the uncovertebral joint if needed, a cage or bone cement was applied in the intervertebral space

|

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 9 (8%) Reasons: no information available on Odom score and VAS-arm score

Control: 6 (5%) Reasons: no information available on Odom score and VAS-arm score

Incomplete outcome data: Missing data for baseline characteristics, but infrequent in both intervention and control group

|

Arm pain (VAS) I: 18.6 ± 22.9 C: 15.8 ± 23.7 MD=2.80, 95%CI -3.06 to 8.66

Neck pain (VAS) I: 24.4 ± 27.5 C: 21.7 ± 26.1 MD=2.70, 95% CI -4.05 to 9.45

Disability (NDI) I: 17.6 ± 14.6 C: 19.2 ± 16.5 MD=-1.60, 95%CI -5.51 to 2.31

Successful score (excellent or good) on Odom-criteria I: 88% (86 of 98) C: 76% (81 of 106) RR=1.15, 95%CI 1.01 to 1.31

Reoperation I: 6 (5%) C: 4 (3%) RR=1.56, 95%CI 0.45 to 5.40

Complications All adverse events I: 36 (30%) C: 35 (28%) RR=1.07, 95%CI 0.72 to 1.5913

All serious adverse events I: 13 (11%) C: 17 (14%) RR=0.80, 95%CI 0.40 to 1.57

Dysphagia I: 1 (0.8%) C: 6 (4.8%) RR=0.17 (95%CI 0.02 to 1.42

Wound infection I: 5 (4.2%) C: 2 (1.6%) RR=2.61 (95%CI 0.52 to 13.17)

Hoarseness I: 1 (0.8%) C: 2 (1.6%) RR=0.52 (95%CI 0.05 to 5.67)

Work status (work ability index score) I: 6.7 ± 2.3 C: 6.7 ± 2.6 MD=0.0, 95%CI -0.62 to 0.62

Quality of life (EQ-5D): I: 0.84 ± 0.15 C: 0.82 ± 0.14 MD=0.02, 95%CI -0.02 to 0.06

Satisfaction (satisfied or very satisfied): I: 70 (73%) C: 76 (77%) RR=0.96, 95%CI 0.78 to 1.18

|

Author’s conclusion: The 1-year clinical effectiveness results demonstrate noninferiority of success rate and arm pain in posterior versus anterior surgery at 1-year follow-up. Decrease in arm pain as well as all secondary outcomes had small between-group differences indicating comparable results between groups.

Limitations: - Inability to blind surgeons and patients - Selection bias |

|

Ebrahim, 2011 |

Type of study: Prospective randomized comparative study

Setting and country: Ain Shams University Hospital, Egypt

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria: - Unilateral cervical radiculopathy that had not responded to conservative treatment for more than 6 weeks - Imaging studies confirming pathoanatomic features (unilateral posterolateral disc herniation or osteophyte compression and foraminal stenosis) corresponding to the clinical symptoms. - No previous cervical spine surgery. - No significant spondylotic stenosis causing spinal cord compromise.

Exclusion criteria: - Cervical myelopathy - Imaging studies showing central or paracentral stenosis; deformity or instability - Previous cervical spine surgery

N total at baseline: Intervention: 15 Control: 15

Important prognostic factors2: Age (range): I: 46.7 years (29 to 62 years) C: 42 years (31 to 52 years)

Sex: I: 60% F C: 47% F

Groups probably comparable at baseline. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Posterior cervical foraminotomy (PCF)

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): Anterior cervical foraminotomy (ACF) |

Length of follow-up: Up to 2 years: C: 12.5 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported |

Neck pain (10-point VAS) Resolved (at end of postoperative follow-up) I: 27.3% C: 50%

Difference at time of discharge: 3.1 (SD=2.5)

Radicular pain (10-point VAS) Resolved (at end of postoperative follow-up) I: 66.7% C: 73.3%

Odom criteria (excellent or good) I: 14 (93%) C: 14 (93%)

Reoperation I: 1 (6.7%) C: 1 (6.7%)

Complications PCF: superficial wound infection (n=1) and intraoperative cerebrospinal fluid leak (n=1)

Return to work or baseline level of activity I: 12 (80%) within 6 weeks C: 12 (80%) within 3 weeks

Patient satisfaction (patient satisfaction index) Very satisfied or satisfied I: 14 (93%) C: 14 (93%)

|

Author’s conclusion: Anterior or posterior cervical foraminotomy for cervical radiculopathy is an effective and safe minimally invasive treatment for unilateral cervical radiculopathy in well selected patients. They can be performed as alternatives to traditional standard anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF), especially in younger patients avoiding potential fusion-related problems, motion limitation and long-term adjacent segment disease which could result from ACDF.

Limitations: No power calculation - No information about randomization/blinding

|

|

Ruetten, 2008 |

Type of study: Prospective, randomized, controlled study

Setting and country: Germany

Funding and conflicts of interest: No funds were received in support of this work. No benefits in any form have been or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of the manuscript

|

Inclusion criteria: - Unilateral radiculopathy with arm pain - In MRI/CT lateral or foraminal localized monosegmental disc herniation - Segments C2-C3-C7-Th1 - Patients with cranio-caudal sequestering and patients with secondary foraminal stenosis (as long as the lateral localization was maintained)

Exclusion criteria: - Clear instabilities or deformities - Medial localization of disc herniation - Isolated neck pain or foraminal stenosis without disc herniation

N total at baseline: Intervention: 100 Control: 100

Important prognostic factors2: Not reported for FPCF and ACDF separately.

Groups comparable at baseline. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Full-endoscopic posterior cervical foraminotomy (PCF) |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): Anterior cervical decompression and fusion (ACDF) |

Length of follow-up: 2 years

Loss-to-follow-up: 2 patients moved away and left no forwarding address, 13 patients did not respond to letters or telephone calls, 10 patients underwent revision surgery with conventional ACDF.

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported |

VAS arm pain (2 years) I: 7 C: 8

VAS neck pain (2 years) I: 16 C: 17

Radicular pain (no pain after 2 years) I: 79 of the 89 patients (89%) C: 76 of the 86 patients (88%)

Perioperative complications I: 3 (3%) had transient, dermatoma-related hypesthesia C: 3 (4%) had transient difficulty swallowing; 1 (1%) surface hematoma and 1 (1%) scar distortion which was cosmetically disruptive

Reoperation I: 3/89 C: 3/86

Patient satisfaction I: 86 of the 89 (96%) C: 78 of the 86 (91%)

|

Author’s conclusion: The recorded results show that the full endoscopic posterior foraminotomy is a sufficient and safe supplement and alternative to conventional procedures when the indication criteria are fulfilled. At the same time, it offers the advantages of a minimally invasive intervention.

Limitations: - No characteristics presented for PCF and ACDF separately |

|

Wirth, 2000 |

Type of study: Randomized, prospective study

Setting and country: USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria: - Patients presenting with cervical radiculopathy caused by unilateral herniated cervical disc - Single-level disease

Exclusion criteria: Signs of myelopathy and additional degenerative changes on plain radiography.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 22 Control: 25 (ACD) and 25 (ACDF)

Important prognostic factors2: Age (range): PCF: 43.8 years (30–66) ACD: 45.0 years (30–67) ACDF: 41.7 years (28–63)

Sex: PCF: 59% F ACD: 48% F ACDF: 44% F

Groups comparable at baseline

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Posterior cervical foraminotomy (PCF) |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): Anterior cervical discectomy (ACD) or anterior cervical discectomy with fusion (ACDF) |

Length of follow-up: At 2-months office visit

Telephone follow-up at 60 months on average PCF: 53 months ACD: 56 months ACDF: 69 months

Loss-to-follow-up: No loss to follow-up at 2 months

At telephone follow-up PCF: 8 (36%) ACD: 12 (48%) ACDF: 9 (36%)

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported. |

Postoperative analgesic medication required (injections plus oral) PCF: 15.9±12.6 ACD: 13.0±9.2 ACDF: 12.5±50.2

Analgesic medication requests PCF: mean 9.2 ACD: mean 6.0 ACDF: mean 6.4

Pain improvement (complete relief or partial improvement of radicular pain) Peri-operative pain improvement (%complete relief): PCF: 100% (41%) ACD: 100% (72%) ACDF: 100% (64%)

Pain improvement (%complete relief) at 2-months PCF: 100% (77%) ACD: 100% (72%) ACDF: 96% (76%)

Pain improvement (%complete relief) at phone follow-up PCF: 100% (50%) ACD: 92% (69%) ACDF: 100% (44%)

Complications: New weakness PCF: 3 (14%) ACD: 2 (8%) ACDF: 2 (8%)

New numbness PCF: 2 (9%) ACD: 2 (8%) ACDF: 1 (4%)

No hoarseness

Return to work 2-months PCF: 91% ACD: 88% ACDF: 92%

Telephone follow-up PCF: 11 (79%) ACD: 12 (92%) ACDF: 13 (81%)

Reoperation PCF: 6 (27%) ACD: 3 (12%) ACDF: 7 (28%) |

Author’s conclusion All three of the procedures were successful for treatment of cervical radiculopathy caused by a herniated cervical disc. Although the numbers in this study were small, none of the procedures could be considered superior to the others. This study suggests that the selection of surgical procedure may reasonably be based on the preference of the surgeon and tailored to the individual patient.

Limitation - No power calculation - Limited information about randomization and blinding |

Risk of bias table for interventions studies

|

Study reference

|

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

|

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

|

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented? Were patients blinded? Were healthcare providers blinded? Were data collectors blinded? Were outcome assessors blinded? Were data analysts blinded? |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

|

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

|

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

|

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

|

|

Broekema, 2022 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Web-based block randomization design was used. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Independent institute web-based block randomization design was used. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Blinding of patients and surgeons was not possible. Interviewer that assessed outcomes was blinded. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. Sensitivity analyses were performed to account for the missing data. |

Probably yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported. |

Probably no;

Reason: Selection bias in enrolment of participants |

LOW (reoperation, complications)

Some concerns (pain, disability, Odom criteria, work status, quality of life, patient satisfaction) |

|

Ebrahim, 2011 |

No information

|

No information

|

No information

|

Probably yes;

Reason: No loss to follow-up reported. |

Probably yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported. |

Probably no;

Reason: No information about funding or conflicts of interest. |

HIGH (pain, Odom criteria, patient satisfaction)

Some concerns (reoperation, complications, return to work) |

|

Ruetten, 2008 |

Probably no;

Reason: Randomization by alternation in the order of presentation by nondoctors assisting in the study.

|

Probably no;

Reason: Randomization was open. |

Probably no;

Reason: Blinding of patients and surgeons not possible. Examinators were blinded. |

Probably no;

Reason: Lost to follow-up of 12.5% and unclear if it differs between treatment groups. |

Probably no;

Reason: Not all outcomes described in the results section were mentioned in the methods. |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems reported. |

HIGH (pain, patient satisfaction)

Some concerns (reoperation, complications) |

|

Wirth, 2000 |

No information |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Randomized by sealed envelope.

|

No information |

Probably yes;

Reason: No lost to follow-up at 2-months and long-term lost to follow-up was similar in treatment groups. |

Probably yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported. |

Probably no;

Reason: No information about funding or conflicts of interest. |

HIGH (pain)

Some concerns (pain medication use, complications, return to work, reoperation) |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Alvin 2014 |

Included only 1 rct including patients with myelopathy, and less recent and complete than Broekema (2020) (wrong population, wrong study design) |

|

Caridi 2011 |

nonsystematic review (wrong study design) |

|

Guo 2022 |

systematic review with network meta-analysis, but multiple anterior interventions in network, not anterior versus posterior (wrong study design) |

|

Liu 2016 |

less recent and complete than Broekema (lacking Ebrahim, 2011) |

|

Skovrlj 2017 |

nonsystematic review (wrong study design) |

|

Sahai 2019 |

less recent and complete than Broekema (lacking Wirth 2011; Ebrahim, 2011) |

|

Platt 2021 |

Search date unknown but less complete than Broekema (lacking Wirth 2011; Ebrahim, 2011) |

|

Alomar 2021 |

less recent and complete than Broekema (lacking Wirth 2011; Ebrahim, 2011) |

|

Zhang 2020 |

less recent and complete than Broekema (lacking Wirth 2011; Ebrahim, 2011) |

|

Fehlings 2009 |

nonsystematic review (wrong study design) |

|

Gutman 2018 |

less recent and complete than Broekema (lacking Wirth 2011; Ebrahim, 2011) |

|

Ament 2018 |

nonsystematic review (wrong study design) |

|

Foster 2019 |

retrospective design (wrong study design) |

|

Tschugg 2014 |

study protocol (wrong study design) |

|

Holy 2021 |

study protocol (wrong study design) |

|

Hohl 2011 |

nonsystematic review (wrong study design) |

|

Broekema 2017 |

study protocol (wrong study design) |

|

Calvanese 2022 |

narrative review (wrong study design) |

|

Shaban 2022 |

two forms of posterior compared (wrong intervention) |

|

Zou 2022 |

Less complete than Broekema (lacking Wirth 2011; Ebrahim, 2011) |

|

Fang 2020 |

meta-analysis included observational studies, no possiblity to substract experimental data (wrong study design) |

|

Gao 2022 |

same relevant RCTs but less transparent reporting compared to Broekema2020 |

|

Holy 2022 |

correction to Holy (2021) |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 24-07-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-07-2024

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodules is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de ‘samenstelling van de werkgroep’) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met een CRS.

WERKGROEP

- Mevr. dr. Carmen Vleggeert-Lankamp (voorzitter), neurochirurg, NVvN

- Dhr. dr. Ruben Dammers, neurochirurg, NVvN

- Mevr. drs. Martine van Bilsen, neurochirurg, NVvN

- Dhr. drs. Maarten Liedorp, neuroloog, NVN

- Mevr. drs. Germine Mochel, neuroloog, NVN

- Mevr. dr. Akkie Rood, orthopedisch chirurg, NOV

- Dhr. dr. Erik Thoomes, fysiotherapeut en manueel therapeut, KNGF/NVMT

- Dhr. prof. dr. Jan Van Zundert, hoogleraar Pijngeneeskunde, NVA

- Dhr. Leen Voogt, ervaringsdeskundige, Nederlandse Vereniging van Rugpatiënten ‘de Wervelkolom’

KLANKBORDGROEP

- Mevr. Elien Nijland, ergotherapeut/handtherapeut, EN

- Mevr. Meimei Yau, oefentherapeut, VvOCM

Met ondersteuning van:

- Mevr. dr. Charlotte Michels, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Mevr. drs. Beatrix Vogelaar, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Naam lid werkgroep |

Hoofdfunctie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Carmen Vleggeert-Lankamp (voorzitter) |

Neurochirurg, Leiden Universitair Medisch Centrum, Leiden

|

* Medisch Manager Neurochirurgie Spaarne Gasthuis, Hoofdorp/ Haarlem, gedetacheerd vanuit LUMC (betaald) * Boardmember Eurospine, chair research committee |

*Niet anders dan onderzoeksleider in projecten naar etiologie van en uitkomsten in het CRS. |

Geen actie |

|

Akkie Rood |

Orthopedisch chirurg, Sint Maartenskliniek, Nijmegen |

Lid NOV, DSS, NvA |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Erik Thoomes |

Fysio-Manueel therapeut / praktijkeigenaar, Fysio-Experts, Hazerswoude |

*Promovendus / wetenschappelijk onderzoeker Universiteit van Birmingham, UK,School of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation Sciences, |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Germine Mochel |

Neuroloog, DC klinieken (loondienst) |

Lid werkgroep pijn NVN Lid NHV en VNHC |

*Dienstverband bij DC klinieken, alwaar behandeling/diagnostiek patiënten CRS

|

Geen actie |

|

Jan Van Zundert |

*Anesthesioloog-pijnspecialist. |

Geen |

Geen financiering omtrent projecten die betrekking hebben op cervicaal radiculair lijden (17 jaar geleden op CRS onderwerk gepromoveerd, nadien geen PhD CRS-projecten begeleidt).

|

Geen actie |

|

Leen Voogt |

*Ervaringsdeskundige CRS. *Voorzitter Nederlandse Vereniging van Rugpatiënten 'de Wervelkolom' (NVVR) |

Vrijwilligerswerk voor de patiëntenvereniging (onbetaald). |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Maarten Liedorp |

Neuroloog in loondienst (0.6 fte), ZBC Kliniek Lange Voorhout, Rijswijk |

*lid oudergeleding MR IKC de Piramide (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Martine van Bilsen |

Neurochirurg, Radboudumc, Nijmegen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Ruben Dammers |

Neurochirurg, ErasmusMC, Rotterdam |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Naam lid klankbordgroep |

Hoofdfunctie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Meimei Yau |

Praktijkhouder Yau Oefentherapeut, Oefentherapeut Mensendieck, Den Haag. |

Geen |

Kennis opdoen, informatie/expertise uitwisselen met andere disciplines, oefentherapeut vertegenwoordigen. KP register |

Geen actie |

|

Vera Keil |

Radioloog, AmsterdamUMC, Amsterdam. Afgevaardigde NVvR Neurosectie |

Geen |

Als radioloog heb ik natuurlijk een interesse aan een sterke rol van de beeldvorming. |

Geen actie |

|

Elien Nijland |

Ergotherapeut/hand-ergotherapeut (totaal 27 uur) bij Treant zorggroep (Bethesda Hoogeveen) en Refaja ziekenhuis (Stadskanaal) |

Voorzitter Adviesraad Hand-ergotherapie (onbetaald) |

|

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door een afgevaardigde van de Nederlandse Vereniging van Rugpatiënten ‘de Wervelkolom’ te betrekken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen (zie kop ‘Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten’). De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Nederlandse Vereniging van Rugpatiënten ‘de Wervelkolom’ en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Dorsale benadering bij CRS (anterieur versus dorsaal) |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet en het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met CRS. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door Ergotherapie Nederland, het Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap, Nederlandse Vereniging van Ziekenhuizen, Nederlandse Vereniging van Revalidatieartsen, Vereniging van Oefentherapeuten Cesar en Mensendieck, Zorginstituut Nederland, Zelfstandige Klinieken Nederland, via enquête. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

NHG, 2018. NHG-Standaard Pijn (M106). Published: juni 2018. Laatste aanpassing: Laatste aanpassing: september 2023. Link: https://richtlijnen.nhg.org/standaarden/pijnhttps://richtlijnen.nhg.org/standaarden/pijn

NVN, 2020. Richtlijn Lumbosacraal Radiculair Syndroom (LRS). Beoordeeld: 21-09-2020. Link: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/lumbosacraal_radiculair_syndroom_lrs/startpagina_-_lrs.html

Radhakrishnan K, Litchy WJ, O'Fallon WM, Kurland LT. Epidemiology of cervical radiculopathy. A population-based study from Rochester, Minnesota, 1976 through 1990. Brain. 1994 Apr;117 ( Pt 2):325-35. doi: 10.1093/brain/117.2.325. PMID: 8186959.