Pulsed Radiofrequency (PRF)

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van Pulsed Radiofrequency (PRF)-behandelingen bij patiënten met CRS?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg Pulsed Radiofrequency (PRF)-behandeling toe te passen bij patiënten met chronisch CRS (>3 maanden), met als doel om pijnverlichting te bewerkstelligen, indien:

- eerdere conservatieve therapie onvoldoende effectief is,

- chirurgie besproken is, en

- de patiënt persisterende arm-pijn ervaart.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

In de literatuur is gekeken naar de effectiviteit van PRF-behandeling bij mensen met een cervicaal radiculair syndroom. Er werden vijf RCT’s gevonden die PRF-behandeling vergeleken met een controle behandeling, waaronder epidurale corticosteroïde-injecties (ECSI), percutane nucleoplastie en schijnbehandeling. De studiepopulaties in deze studies zijn echter klein, met enkele methodologische beperkingen (risico op bias, imprecisie). De bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten pijn, patiënttevredenheid en complicaties en de overall bewijskracht komt daarmee op zeer laag. Dit betekent dat nieuwe studies kunnen leiden tot nieuwe inzichten. Derhalve kunnen er op basis van de literatuur geen sterke conclusies worden getrokken over de effectiviteit van PRF-behandeling bij mensen met cervicaal radiculair syndroom ten opzichte van controle behandelingen.

Met het vaststellen van een zeer lage bewijskracht, is echter niet gezegd dat er geen bewijs is (Huygen, 2019). Hierbij neemt de werkgroep twee facetten in overweging:

- Ondanks de lage patiëntaantallen, toont Van Zundert (2007) een effect van PRF-behandeling op pijn, patiënttevredenheid, medicatie-gebruik en zelfs voorkómen van nekchirurgie.

- Behandelvoorkeur bij de patiënt lijkt een grote rol te spelen op de haalbaarheid van het uitvoeren van een RCT bij PRF-behandelingen. Zo gaf bijvoorbeeld 50% in Van Zundert (2007) geen informed consent voor deelname aan de sham-controle groep. Verschillende artikelen en case series concluderen dat PRF-behandeling aanbevolen kan worden (Kwak, 2018; Huygen, 2019; Peene, 2023).

Daarbij is het belangrijk dat het bewijs voor effect van PRF-behandeling zich beperkt tot een chronisch (>3 maanden) CRS. Er lijkt geen verschil in effect te zijn tussen PRF-behandeling en epidurale corticosteroïde-injecties (Wang, 2016; Lee, 2016). Een argument voor PRF-behandeling is dat er geen ernstige complicaties zijn gemeld tijdens de procedure zoals bij het gebruik van epidurale corticosteroïde-injecties (Peene, 2023). Vervolgonderzoek op dit gebied is wenselijk. Een argument tegen PRF-behandeling is dat het werkingsmechanisme minder duidelijk is dan van epidurale corticosteroïde-injecties.

De werkgroep doet geen uitspraak of het geven van een gecombineerde behandeling van PRF én epidurale corticosteroïde-injecties zinvol is.

De werkgroep is van mening dat bij een chronisch CRS, in samenspraak met de patiënt en afhankelijk van het beloop na eerdere epidurale corticosteroïde-injecties, er gekozen kan worden voor een herhaalde epidurale corticosteroïde-injectie dan wel PRF-behandeling. Indien de eerste PRF-behandeling effectief is gebleken, kan de PRF-behandeling tot één á twee keer bij dezelfde pijn episode herhaald worden (expert opinion).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

De meeste patiënten die voor PRF-behandeling in aanmerking komen hebben al een conservatieve behandeling ondergaan, met onvoldoende resultaat of (ernstige) complicaties. De werkgroep geeft de voorkeur aan een beslissing in samenspraak met de patiënt, waarbij de voor- en nadelen worden afgewogen.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er is weinig bekend over de kosteneffectiviteit van PRF-behandelingen bij patiënten met CRS. De werkgroep verwacht dat de PRF-behandelingen als interventie bescheiden kosten met zich meebrengt.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Op het gebied van aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie voorziet de werkgroep geen grote uitdagingen. De behandeling wordt op diverse plekken in Nederland uitgevoerd. De werkgroep voorziet geen grote haalbaarheid en implementatie barrières.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Hoewel de bewijskracht zeer laag is, acht de werkgroep op basis van praktijkervaring, expert opinion en overige literatuur dat een PRF-behandeling te overwegen is bij patiënten met chronische CRS.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Een Pulsed Radiofrequency (PRF)-behandeling bestaat uit een radiofrequente stroom die via een speciale naald met kleine stootjes wordt gegeven. Daardoor wordt de geleidingscapaciteit van de zenuwwortel beïnvloed, waardoor in veel gevallen de pijn vermindert. Een PRF-behandeling is gericht op de uitstralende pijn (radiculaire of zenuwwortelpijn) en niet zozeer op rug- of nekklachten zelf. Deze behandelingen worden op steeds grotere schaal toegepast. Meestal niet in de acute fase, maar veelal bij patiënten met chronische (>3 maanden) CRS.

Momenteel is het onduidelijk wanneer PRF-behandelingen precies overwogen dienen te worden. De achterliggende gedachte is dat een PRF-behandeling veiliger is dan een injectie met epidurale corticosteroïde (ECSI), vooral die via de transforaminale route. Deze module evalueert de inzet van PRF-behandelingen bij patiënten met CRS.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Pain (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PRF treatment on pain when compared with control treatment in patients with chronic cervical radicular syndrome.

Source: Van Zundert, 2007; Lee, 2016; Halim, 2017; Wang, 2016; Chalermkitpanit, 2023. |

2. Patient satisfaction (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PRF treatment on patient satisfaction when compared with control treatment in patients with chronic cervical radicular syndrome.

Source: Van Zundert, 2007; Halim, 2017; Wang, 2016. |

3. Complications (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PRF treatment on complications when compared with control treatment in patients with chronic cervical radicular syndrome.

Source: Van Zundert, 2007; Lee, 2016; Halim, 2017; Wang, 2016; Chalermkitpanit, 2023. |

4. Medication use (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PRF treatment on medication use when compared with control treatment in patients with chronic cervical radicular syndrome.

Source: Van Zundert, 2007; Chalermkitpanit, 2023. |

5. Functioning (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PRF treatment on functioning when compared with control treatment in patients with chronic cervical radicular syndrome.

Source: Van Zundert, 2007; Lee, 2016; Halim, 2017; Chalermkitpanit, 2023. |

6. Quality of life (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

PRF treatment likely results in little to no difference in quality of life when compared with control treatment in patients with chronic cervical radicular syndrome.

Source: Van Zundert, 2007. |

7. Cervical surgery

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PRF treatment on cervical surgery when compared with control treatment in patients with chronic cervical radicular syndrome.

Source: Van Zundert, 2007. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Van Zundert (2007) performed a double-blind RCT to evaluate the efficacy of PRF treatment in patients with chronic cervical radicular pain. A total of 23 patients with cervical radicular pain for at least 6 months were included. Note: Of the 114 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 63 (55%) gave no informed consent. Patients were randomly assigned to either the PRF treatment group (n=11, mean age ± SD: 42 ± 12 years, %male: 46%, mean pain duration ± SD: 54 ± 40 months) or the sham treatment group (n=12, mean age ± SD: 53 ± 12 years, %male: 42%, mean pain duration ± SD: 60 ± 65 months). Patients in the PRF treatment group received PRF stimulation at 0.5V during 120s adjacent to the cervical dorsal root ganglion. Sham treatment consisted of the same preparation procedure as the intervention group, however, instead of passing current through the electrode the generator was merely manipulated without starting the procedure. The following outcome measures were reported: pain, patient satisfaction, complications, medication use, functioning, quality of life, and cervical surgery.

Lee (2016) performed a RCT to compare the effectiveness of PRF with a second transforaminal epidural steroid injection (TFESI) after failure of a first TFESI for the treatment of radicular pain due to disc herniation. In total, 38 patients with cervical or lumbar radicular pain were included. Patients were randomly assigned to either the PRF group (n=19, mean age ± SD: 54 ± 12 years, mean pain duration: 5.1 weeks, cervical pain n=10, lumbar pain n=9) or the TFESI group (n=19, mean age ± SD: 51 ± 13 years, mean pain duration: 4.8 weeks, cervical pain n=8, lumbar pain n=11). PRF treatment was administered at 5 Hz and a 5 ms pulsed width for 240 seconds at 45V. Patients in the TFESI group received 2 mL of 0.125% bupivacaine mixed with 5 mg dexamethasone. The following outcome measures were reported: pain, complications, and functioning. Subgroup analyses were performed for patients undergoing cervical and lumbar procedures.

Halim (2017) conducted an RCT to evaluate the efficacy of PRF compared to percutaneous nucleoplasty (PCN) in patients with contained cervical disc herniation. A total of 34 patients with single level contained cervical disc herniation were included. Patients were randomized to either PCN treatment (n=17, mean age: 50 years, %male: 41%, mean duration of symptoms: 12 months) or PRF treatment (n=17, mean age: 52 years, %male: 53%, mean duration of symptoms: 12 months). Patients in the PRF treatment group received PRF stimulation of the dorsal root ganglion at 45V, 2 Hz (20ms) for six minutes. PCN treatment consisted of decompression of the herniated disc, using a 52°C thermal reaction. The following outcome measures were reported: pain, patient satisfaction, complications, and functioning.

Wang (2016) performed an RCT to compare the efficacy of cervical nerve root block (CNRB) with betamethasone, PRF, and CNRB + PRF in patients with chronic cervical radicular pain. In total, 62 patients with moderate to severe chronic cervical radicular pain were included. Patients were randomized into three groups and received treatment with CNRB (n=21, mean age ± SD: 59 ± 14 years, %male: 43%, mean pain duration ± SD: 9.5 ± 5.2 months), PRF (n=20, mean age ± SD: 58 ± 16 years, %male: 55%, mean pain duration ± SD: 10.1 ± 5.1 months), or a combination of CNRB and PRF (n=21, mean age ± SD: 58 ± 15 years, %male: 38%, mean pain duration ± SD: 8.6 ± 3.9 months). Data on the CNRB + PRF group is not considered in this module because it is beyond the scope of this module. PRF treatment consisted of a PRF stimulus that was applied for 4 minutes followed by radiculography. CNRB treatment consisted of a mixture of corticosteroids containing betamethasone dipropionate and betamethasone disodium phosphate, NaCl, and lidocaine after radiculography. The following outcome measures were reported: pain, patient satisfaction, and complications.

Chalermkitpanit (2023) conducted an RCT to evaluate the efficacy of PRF for patients with cervical radicular pain for at least 3 months. A total of 41 patients with moderate to severe cervical radicular pain were included. Patients were randomly assigned to either PRF treatment and steroid (n=20, mean age ± SD: 49 ± 16 years, %male: 40%, mean pain duration ± SD: 6.5 ± 6.4 months) or transforaminal steroid treatment (n=21, mean age ± SD: 56 ± 15 years, %male: 38%, mean pain duration ± SD: 7 ± 7.4 months). After a sensory stimulation, PRF treatment was performed between 0.3-0.5 volts at 42°C for 4 minutes. Thereafter, patients got injected a mixture of lidocaine and dexamethasone. Patients in the steroid group received sensory stimulation with a short bevel stimulating 22G-needle followed by the same injectate. The following outcome measures were reported: pain, complications, medication use, and functioning.

Results

1. Pain

Five studies reported on pain (Van Zundert, 2007; Lee, 2016; Halim, 2017; Wang, 2016; Chalermkitpanit, 2023). Results are presented in Table 1. Data could not be pooled because of the diversity in presentation of the data (dichotomous/continuous), missing absolute values (Wang, 2016), or dispersion measures (SE/SD) (Halim, 2017).

Van Zundert (2007) reported on pain, defined as a 20-points reduction in pain intensity measured by VAS score three months after treatment. Authors reported that pain improvement was achieved in 82% (9/11) of patients in the PRF treatment group (VAS score pre-treatment mean ± SD: 55.7 ± 17.3) and in 25% (3/12) in the sham treatment group (VAS score pre-treatment mean ± SD: 76.2 ± 14.2). The risk ratio was 3.27 (95%CI 1.18 to 9.07) in favour of PRF treatment, which was considered clinically relevant.

Lee (2016) reported on pain intensity measured by VAS (0-10 mm) three months after treatment. Subgroup analyses were performed based on the presentation of radicular pain (cervical or lumbar). For patients with cervical radicular pain, they reported a mean ± SD VAS score of 2.0 ± 0.8 for the PRF treatment group (n=10) and 2.4 ± 2.3 for the TFESI treatment group (n=8). Mean difference was 0.40 (95%CI -2.07 to 1.27) in favour of PRF treatment. This difference was not considered clinically relevant.

Halim (2017) reported on pain measured by VAS (0-100 mm) three months after treatment. They reported a mean VAS score of 35.5 for the PRF treatment group (n=17) and 27.6 for the PCN treatment group (n=17). Effect measures were not reported and could not be calculated due to missing dispersion measures.

Wang (2016) reported on pain defined as pain intensity measured by a 11-point NRS six months after treatment. They reported that the mean NRS in each group was reduced at all time intervals (1 week, 1 month, 3 months and 6 months) compared to baseline. Effect measures were not reported and could not be calculated due to missing dispersion measures.

Chalermkitpanit (2023) reported on pain measured by NRS (0-10) three months post procedure. They reported a mean ± SD NRS score of 2.8 ± 2.7 for the PRF + steroid treatment group (n=20) and 5.5 ± 2.6 for the steroid treatment group (n=21). Mean difference was 2.70 (95%CI -4.32 to -1.08) in favour of PRF treatment. This difference was clinically relevant.

Table 1. Outcome Pain: comparison VAS/NRS scores

|

Study |

Comparison

|

PRF (mean ± SD) |

Control (mean ± SD) |

||

|

Baseline |

follow-up 3 months |

Baseline |

follow-up 3 months |

||

|

Van Zundert, 2007 (n=11/12 VAS 0-100mm) |

PRF vs sham |

55.7 ± 17.3 |

43* ± nr |

76.2 ± 14.2 |

62* ± nr |

|

Lee, 2016 (n=10/8, VAS 0-10mm) |

PRF vs 2nd TFESI 2-6wks after failure TFESI |

5.3 ± 1.2 |

2.0 ± 0.8 |

4.9 ± 0.8 |

2.4 ± 2.3 |

|

Wang, 2016 (n=20/21, NRS 0-10) |

PRF vs TFESI |

6.2 ± 1.0 |

4.0* ± nr |

6.0 ± 0.08 |

4.0* ± nr |

|

Halim, 2017 (n=17/17, VAS 0-100mm) |

PRF vs PCN |

69.5 ± nr |

35.5 ± nr |

71.0 ± nr |

27.6 ± nr |

|

Chalermkitpanit, 2023 (n=20/21, NRS 0-10) |

PRF+steroid vs TFESI |

7.5* ± nr |

2.8 ± 2.7 |

7.9* ± nr |

5.5 ± 2.6 |

|

*estimated from figure; nr: not reported |

|||||

2. Patient satisfaction

Three studies reported on patient satisfaction (Van Zundert, 2007; Halim, 2017; Wang, 2016). Data could not be pooled because of missing dispersion measures (SE/SD) (Halim, 2017).

Van Zundert (2007) reported on patient satisfaction defined as the global perceived effect (GPE), measured using a 7-point Likert scale. Authors reported the number of patients with >50% improvement in GPE (6 or 7 on Likert scale) three months after treatment. In the PRF treatment group, this was achieved in 82% (9/11) of patients, whereas in the sham treatment group it was achieved in 33% (4/12) of patients. The risk ratio was 2.45 (95%CI 1.05 to 5.73) in favour of PRF treatment, which was considered clinically relevant.

Halim (2017) reported on patient satisfaction using a VAS for satisfaction three months after treatment. They reported a mean VAS satisfaction score of 63.5 for the PRF treatment group (n=17) and 58.4 for the PCN treatment group (n=17). Effect measures were not reported and could not be calculated due to missing dispersion measures.

Wang (2016) reported on patient satisfaction defined as positive GPE (+2 or +3 points) six months after treatment, measured using a 7-point scale. Authors reported positive GPE in 11% (2/19) of patients in the PRF treatment group and in 5% (1/19) of patients in the CNRB treatment group. The risk ratio was 2.00 (95%CI 0.20 to 20.24) in favour of PRF treatment, which was considered clinically relevant.

3. Complications

Five studies reported on complications (Van Zundert, 2007; Lee, 2016; Halim, 2017; Wang, 2016, Chalermkitpanit, 2023). Van Zundert (2007), Lee (2016), Halim (2017) and Wang (2016) reported on the proportion of patients with complications. Chalermkitpanit (2023) reported on procedure-related complications.

Data of Chalermkitpanit (2023) could not be pooled because no absolute values were described. Authors reported that there was no difference the number of procedure-related complications between both groups.

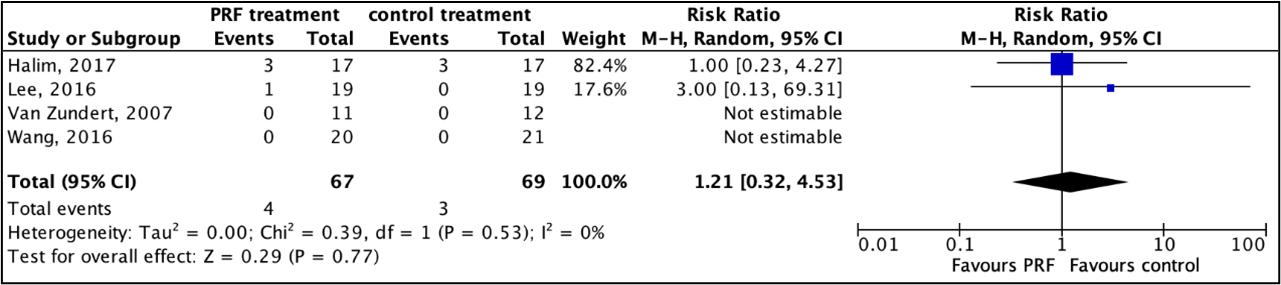

The pooled data show a risk ratio of 1.21 (95%CI 0.32 to 4.53) in favour of control treatment (Figure 1), which was considered clinically relevant.

Figure 1: The effect of PRF treatment on complications.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

4. Medication use

Two studies reported on medication use (Van Zundert, 2007; Chalermkitpanit, 2023).

Van Zundert (2007) reported on medication use, defined as a reduction in the intake of pain medication from baseline to three months (Van Zundert, 2007). A reduction in the intake of pain medication was reported in 55% (6/11) of patients in the PRF treatment group and in 33% (4/12) of patients in the sham treatment group. The risk ratio was 1.64 (95%CI 0.62 to 4.30) in favour of PRF treatment, which was considered clinically relevant.

Chalermkitpanit (2023) reported on the amount of rescue pain medication. They reported that there was no difference in the amount of rescue pain medication between both groups. Effect measures were not reported and could not be calculated due to missing dispersion measures.

5. Functioning

Four studies reported on functioning (Van Zundert, 2007; Lee, 2016; Halim, 2017; Chalermkitpanit, 2023). Results are presented in Table 2. Data could not be pooled because of the diversity in presentation of the data (mean difference/mean value), and because of missing dispersion measures (SE/SD) (Halim, 2017).

Van Zundert (2007) reported on functioning, defined as physical functioning after 3 months of treatment, measured using the Short Form 36 (SF-36). They reported a mean difference ± SD in physical functioning score between baseline and three months of 9.0 ± 16.6 in the PRF treatment group (n=11) and 6.9 ± 15.0 in the sham treatment group (n=12).

Lee (2016) reported on functioning, defined as functional disabilities associated with cervical radicular pain after three months of treatment, assessed using the Neck Disability Index (NDI) (0-50). They reported a mean ± SD NDI score of 14.0 ± 7.0 in the PRF treatment group (n=10) and 17.0 ± 14.3 in the TFESI treatment group (n=8). Mean difference was 3.0 (95%CI -13.82 to 7.82) in favour of PRF treatment. This difference was not considered clinically relevant.

Halim (2017) reported on neck and limb functioning three months after treatment, measured using the NDI (0-50). They reported a mean NDI score of 10.8 for the PRF treatment group (n=17) and 11.1 for the PCN treatment group (n=17). Effect measures were not reported and could not be calculated due to missing dispersion measures.

Chalermkitpanit (2023) reported on functioning measured using the NDI. After three months, they reported a mean difference of 23.0 (95%CI 9.6 to 36.4) between the PRF treatment group (n=20) and the steroid treatment group (n=21). After six months, they reported a mean difference of 23.8 (95%CI 4.2 to 43.3) between the PRF treatment group and the steroid treatment group.

Table 2. Outcome Functioning: comparison NDI scores

|

Study |

Comparison

|

PRF (mean ± SD) |

Control (mean ± SD) |

||

|

Baseline |

follow-up 3 months |

Baseline |

follow-up 3 months |

||

|

Lee, 2016 (n=10/8, VAS 0-10mm) |

PRF vs 2nd TFESI 2-6wks after failure TFESI |

38.7 ± 8.3 |

14.0 ± 7.0 |

39.1 ± 11.6 |

17.0 ± 14.3 |

|

Halim, 2017 (n=17/17, VAS 0-100mm) |

PRF vs PCN |

19.4 ± 10.8 |

10.8 ± nr |

21.1 ± nr |

11.1 ± nr |

|

Chalermkitpanit, 2023 (n=20/21, NRS 0-10) |

PRF+steroid vs TFESI |

49* ± 20* |

20* ± nr |

48* ± nr |

40* ± nr |

|

*estimated from figure; nr: not reported |

|||||

6. Quality of life

One study reported on quality of life, by using SF-36 and Euroqol (Van Zundert, 2007). Table 3 shows mean differences in SF-36 and Euroqol scores between baseline and three months for both treatment groups. Quality of life indicated a trend towards a better result after three months in the PRF group compared to the sham treatment group.

Table 3. Results of the SF-36 and Euroqol (Van Zundert, 2007)*

|

Item |

PRF group (n=11) |

Sham group (n=12) |

|

|

Euroqol |

12.6 ± 19.7 |

4.7 ± 30.8 |

|

|

SF-36 |

|||

|

|

Physical functioning |

9.0 ± 16.6 |

6.9 ± 15.0 |

|

|

Social functioning |

12.5 ± 28.0 |

-1.0 ± 28.4 |

|

|

Physical role restriction |

23.5 ± 48.6 |

24.3 ± 26.9 |

|

|

Emotional role restriction |

24.2 ± 36.8 |

0.0 ± 53.7 |

|

|

Mental health |

6.9 ± 12.9 |

0.3 ± 22.2 |

|

|

Vitality ** |

17.3 ± 17.1 |

2.1 ± 16.0 |

|

|

Pain |

9.8 ± 20.5 |

9.3 ± 25.8 |

|

|

General health |

4.1 ± 10.0 |

2.3 ± 19.0 |

|

*Data are presented as mean difference ± SD between baseline and three months. ** Statistically significant, p=0.04 |

|||

7. Cervical surgery

One study reported on cervical surgery, defined as the number of patients requiring neck surgery (Van Zundert, 2007). Authors reported that 9.1% (1/11) of patients in the PRF treatment group required neck surgery and 25% (3/12) of patients in the sham treatment group. The risk ratio was 0.36 (95%CI 0.04 to 3.00) in favour of PRF treatment, which was considered clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature

1. Pain

The level of evidence regarding pain was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias: -1), differences in PRF and control treatment between the studies (indirectness: -1), and because the confidence interval is crossing the border of clinical relevance (imprecision: -1).

2. Patient satisfaction

The level of evidence regarding patient satisfaction was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias: -1), differences in PRF and control treatment between the studies (indirectness: -1), and because the confidence interval is crossing the border of clinical relevance (imprecision: -1).

3. Complications

The level of evidence regarding complications was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias: -1), differences in PRF and control treatment between the studies (indirectness: -1), and because the confidence interval is crossing the border of clinical relevance and the low number of events (imprecision: -1).

4. Medication use

The level of evidence regarding medication use was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias: -1), differences in PRF and control treatment between the studies (indirectness: -1), and because the confidence interval is crossing the borders of clinical relevance (imprecision: -1).

5. Functioning

The level of evidence regarding functioning was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias: -1), differences in PRF and control treatment between the studies (indirectness: -1), and because the confidence interval is crossing the border of clinical relevance (imprecision: -1).

6. Quality of life

The level of evidence regarding quality of life was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias: -1), and because of the very low number of patients and inclusion from only one study (imprecision: -2).

7. Cervical surgery

The level of evidence regarding cervical surgery was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias: -1), the very low number of patients and events from one study, and because the confidence interval is crossing both borders of clinical relevance (imprecision: -2).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic search of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the effectiveness of Pulsed Radiofrequency (PRF) compared to other interventions in patients with chronic CRS?

P = Patients with chronic CRS (not myelopathy)

I = Pulsed radiofrequency (PRF)

C = Any comparator, usual care, PRF with corticosteroid injections, corticosteroid injections, sham intervention

O = Pain, patient satisfaction, complications, medication use, functioning, quality of

life, cervical surgery

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered pain, patient satisfaction and complications as critical outcome measures for decision making and medication use, functioning, quality of life and cervical surgery as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined a 10% difference for continuous outcome measures (weighted mean difference), 10% for dichotomous outcome measures informing on relative risk (0.91 ≤ RR ≥ 1.1), and standardized mean difference (≤-0.5 SMD ≥0.5) as minimal clinically (patient) important differences. This decision was based on the minimal important change scores described in the article by Ostelo (2008), in accordance with the Dutch Lumbosacral Radicular syndrome guideline (NVN, 2020).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 10 February 2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 124 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic reviews (searched in at least two databases, and detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment and results of individual studies available) or randomized controlled trials;

- Adults (>18 years);

- Publication date >1998;

- Studies including >20 (ten in each study arm) patients;

- Full-text English or Dutch language publication; and

- Studies according to the PICO.

Twenty-seven studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 22 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and five studies were included.

Results

Five studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Chalermkitpanit P, Pannangpetch P, Kositworakitkun Y, Singhatanadgige W, Yingsakmongkol W, Pasuhirunnikorn P, Tanasansomboon T. Ultrasound-guided pulsed radiofrequency of cervical nerve root for cervical radicular pain: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Spine J. 2023 May;23(5):651-655. Doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2023.01.004. Epub 2023 Jan 12. PMID: 36641034.

- Halim W, van der Weegen W, Lim T, Wullems JA, Vissers KC. Percutaneous Cervical Nucleoplasty vs. Pulsed Radio Frequency of the Dorsal Root Ganglion in Patients with Contained Cervical Disk Herniation; A Prospective, Randomized Controlled Trial. Pain Pract. 2017 Jul;17(6):729-737. Doi: 10.1111/papr.12517. Epub 2016 Oct 14. PMID: 27611826.

- Huygen F, Kallewaard JW, van Tulder M, Van Boxem K, Vissers K, van Kleef M, Van Zundert J. "Evidence-Based Interventional Pain Medicine According to Clinical Diagnoses": Update 2018. Pain Pract. 2019 Jul;19(6):664-675. Doi: 10.1111/papr.12786. Epub 2019 May 2. PMID: 30957944; PMCID: PMC6850128.

- Kwak SY, Chang MC. Effect of intradiscal pulsed radiofrequency on refractory chronic discogenic neck pain: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Apr;97(16):e0509. Doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010509. PMID: 29668635; PMCID: PMC5916694.

- Lee DG, Ahn SH, Lee J. Comparative Effectivenesses of Pulsed Radiofrequency and Transforaminal Steroid Injection for Radicular Pain due to Disc Herniation: a Prospective Randomized Trial. J Korean Med Sci. 2016 Aug;31(8):1324-30. Doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.8.1324. Epub 2016 Jun 24. PMID: 27478346; PMCID: PMC4951565

- Peene L, Cohen SP, Brouwer B, James R, Wolff A, Van Boxem K, Van Zundert J. 2. Cervical radicular pain. Pain Pract. 2023 Jun 4. Doi: 10.1111/papr.13252. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37272250.

- Van Zundert J, Patijn J, Kessels A, Lamé I, van Suijlekom H, van Kleef M. Pulsed radiofrequency adjacent to the cervical dorsal root ganglion in chronic cervical radicular pain: a double blind sham controlled randomized clinical trial. Pain. 2007 Jan;127(1-2):173-82. Doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.002. Epub 2006 Oct 18. PMID: 17055165.

- Wang F, Zhou Q, Xiao L, Yang J, Xong D, Li D, Liu L, Ancha S, Cheng J. A Randomized Comparative Study of Pulsed Radiofrequency Treatment With or Without Selective Nerve Root Block for Chronic Cervical Radicular Pain. Pain Pract. 2017 Jun;17(5):589-595. Doi: 10.1111/papr.12493. Epub 2016 Oct 14. PMID: 27739217.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Van Zundert, 2007 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Patients that were referred to the pain centers of the University Hospital Maastricht, Maastricht, The Netherlands; Ziekenhuis Oost-Limburg, Genk, Belgium, and Catharina Hospital, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, were screened for inclusion.

Funding and conflicts of interest: None declared. |

Inclusion criteria: - Neck pain radiating over the posterior shoulder area to the arm for >6 months. - Conventional therapy, including medication, physical therapy, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, was not effective. - Symptoms should suggest involvement of the cervical spinal nerve and be perceived along the affected nerve root. - Positive Spurling test. - Average pain intensity (VAS) > 35.

Exclusion criteria: - Age <20 years or >75 years. - History of cancer. - Fractures of the cervical vertebrae. - Myelopathy. - Previous cervical fusion or laminectomy. - Systemic diseases or connective tissue diseases. - Diabetes mellitus. - Coagulation disorders and use of anticoagulants. - Multiple sclerosis. - Pregnancy. - Shoulder pathology. - Presence of a cardiac pacemaker or spinal cord stimulator. - Previous RF or PRF treatment of the cervical DRG.

N total at baseline: I: 11 C: 12

Important prognostic factors: Age ± SD: I: 42 ± 12.2 C: 52.9 ± 11.9

Sex (%male): I: 46% C: 42%

Groups comparable at baseline? No, patients in the control group were older and started with a higher VAS score. |

Describe intervention: PRF treatment - Stimulation was started at 50 Hz to obtain a sensory stimulation threshold. - The PRF current was applied during 120 s from the lesion generator.

|

Describe control: Sham treatment during which the identification of the target point, electrode placement, and the sensory stimulation was performed in the same way as for the patients in the intervention group. |

Length of follow-up: 6 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: none before 3 months Reasons: -

Control: 1 before 3 months Reasons: surgical treatment

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported, except loss-to-follow-up as above.

|

Outcome measures and effect size: Pain Defined as a 20-points reduction in pain intensity measured by VAS after 3 months I: 82% (9/11) C: 25% (3/12)

Patient satisfaction Defined as at least 50% pain improvement of the GPE 4 weeks I: 64% (7/11) C: 42% (5/12) 3 months I: 82% (9/11) C: 33% (4/12) 6 months I: 64% (7/11) C: 17% (2/12)

Complications Defined as the number of participants that reported side effects or complications over the study period I: 0 C: 0

Medication use Defined as the change in intake of pain medication from baseline to 3 months Higher I: 9.1% (1/11) C: 41.7% (5/12) Equal I: 36.4% (4/11) C: 25.0% (3/12) Lower I: 54.5% (6/11) C: 33.3% (4/12)

Functioning SF-36, defined as the mean difference (SD) at 3 months Physical functioning I: 9.0 (16.6) C: 6.9 (15.0) Social functioning I: 12.5 (28.0) C: -1.0 (28.4)

Quality of life Euroqol, defined as the mean difference (SD) at 3 months I: 12.6 (19.7) C: 4.7 (30.8)

SF-36, defined as the mean difference (SD) at 3 months Physical role restriction I: 23.5 (48.6) C: 24.3 (26.9) Emotional role restriction I: 24.2 (36.8) C: 0.0 (53.7) Mental health I: 6.9 (12.9) C: 0.3 (22.2) Vitality I: 17.3 (17.1) C: 2.1 (16.0) Pain I: 9.8 (20.5) C: 9.3 (25.8) General health I: 4.1 (10.0) C: 2.3 (19.0)

Cervical surgery Defined as the number of participants that were referred for neck surgery I: 9% (1/11) C: 25% (3/12) |

Authors conclusion: PRF treatment of the cervical dorsal root ganglion might provide pain relief for a limited number of patients with chronic cervical radicular pain.

Limitations: - Difference in baseline demographic characteristics. - Low inclusion rate, resulting in not enough power for different parameters.

|

|

Lee, 2016 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Department of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, Dongsan Medical Center, Keimyung University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea, Department of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, Yeungnam University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea.

Funding and conflicts of interest: The study was supported by the 2015 Yeungnam University Research Grant. The authors had no potential conflicts of interest to disclose. |

Inclusion criteria: - Age between 20 and 70 years. - Presentation with symptomatic cervical or lumbar radicular pain. - Imaging findings of a cervical or lumbar intervertebral disc pathology compatible with pain symptoms. - Severe cervical or lumbar radicular pain than cervical or lumbar axial pain. - Presentation with a VAS of >4 and an ODI or Neck Disability Index of >30% after first TFESI.

Exclusion criteria: - Severe allergy to injectants. - History of spine surgery. - Spinal instability. - Spinal stenosis or degenerative spondylolisthesis. - Infection on the spine. - Tumor or tumor metastasis in the involved spinal area. - Pregnancy.

N total at baseline: I: 19 C: 19

Important prognostic factors: Age ± SD: I: 54.3 ± 12.1 C: 50.8 ± 12.7

Sex (%male): I: 16% C: 58%

Groups comparable at baseline? No, percentage male differed between the two groups. |

Describe intervention: PRF therapy: - The catheter needle was inserted, and a sensory stimulation test was carried out using an RF generator. - Treatment was administered at 5 Hz and a 5 ms pulsed width for 240 seconds at 45V. |

Describe control: Transforaminal epidural steroid injection: - Patients received 2 mL of 0.125% bupivacaine mixed with 5 mg dexamethasone. |

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Total: 6 Reasons: drop-out (n=5), flare up pain (n=1).

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported, except loss-to-follow-up as above. |

Outcome measures and effect size: Pain Defined as pain intensities, assessed by VAS, mean (SD) Pre-treatment I: 5.3 (1.2) C: 4.9 (0.8) 2 weeks I: 4.2 (1.3) C: 3.6 (1.2) 4 weeks I: 3.3 (1.1) C: 2.8 (1.3) 8 weeks I: 2.4 (0.9) C: 2.5 (2.1) 3 months I: 2.0 (0.8) C: 2.4 (2.3)

Complications I: 5.3% (1/19) C: 0% (0/19)

Functioning Defined as functional disabilities associated with cervical radicular pain, assessed by NDI, mean (SD) Pre-treatment I: 38.7 (8.3) C: 39.1 (11.6) 2 weeks I: 28.3 (14.7) C: 28.6 (9.7) 4 weeks I: 22.2 (11.6) C: 19.4 (11.2) 8 weeks I: 17.6 (6.8) C: 18.8 (15.7) 3 months I: 14.0 (7.0) C: 17.0 (14.3)

|

Authors conclusion: PRF treatment can be considered as a useful option for the control of radicular pain that helps reduce or avoid the possible adverse effects of TFESI.

Limitations: - Small sample size

Other remarks: Subgroup analyses for cervical radicular patients are available.

|

|

Halim, 2017 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Anna Hospital, Geldrop, The Netherlands, Radboud UMC Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Funding and conflicts of interest: No funding reported. The institution one author works for receives study grants from Cotera Inc and Zimmer Biomet Inc, and he is a consultant for Zimmer Biomet, but this is unrelated to the current study. |

Inclusion criteria: - Patients with a contained, single-level cervical disk herniation diagnosed on recent MRI (<4 weeks) who failed conservative treatment. - Presentation with a 100 mm VAS of >50 mm with or without neck pain corresponding to the herniated level. - Disk height over 50% of adjacent level.

Exclusion criteria: - Patients who did not respond to a diagnostic nerve block placed with local anesthetic at the level identified with history taking and MRI. - Extruded disk fragmentation. - Cervical spondylolisthesis. - Spinal canal stenosis. - Previous surgery at the index cervical disk herniation level.

N total at baseline: I: 17 C: 17

Important prognostic factors: Age ± SD: I: 49.5 C: 52.4

Sex (%male): I: 53% C: 41%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention: PRF treatment: - A 45 V, 2 Hz (20 ms) PRF stimulus was applied for 6 minutes. |

Describe control: Percutaneous nucleoplasty treatment |

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 7 Reasons: no reason provided

Control: 3 Reasons: no reason provided

Incomplete outcome data: No other than loss-to-follow-up reported above. |

Outcome measures and effect size: Pain Baseline I: 69.5 C: 71.0 1 month I: 41.0 C: 29.3 2 months I: 38.0 C: 31.5 3 months I: 35.5 C: 27.6

Patient satisfaction 1 month I: 52.8 C: 68.9 2 months I: 60.9 C: 67.8 3 months I: 63.5 C: 58.4

Complications I: 18% (3/17) C: 18% (3/17)

Functioning Baseline I: 19.4 C: 21.1 1 month I: 14.9 C: 15.9 2 months I: 12.2 C: 12.3 3 months I: 10.8 C: 11.1 |

Authors conclusion: Both PRF and PCN treatment show significant pain improvement in patients with contained cervical disk herniation, but none of the treatments is superior to the other. Both treatment options are shown to be effective and safe for use in clinical practice.

Limitations: - Comparison of two active treatments. - Limited follow-up of 3 months. - Small sample size.

|

|

Wang, 2016 |

Type of study: Randomized comparative study

Setting and country: Pain Management Department of Shenzhen Nanshan Hospital in China.

Funding and conflicts of interest: No conflicts of interest to declare. Nothing is mentioned about funding. |

Inclusion criteria: - Age >20 years - Males and females - Moderate to severe chronic cervical radicular pain (NRS > 5) - Resistance to conservative management - No indication for open surgical intervention - MRI evidence of nerve root compression - Absence of progressive motor deficit

Exclusion criteria: - Uncorrected coagulopathy - Infection - Cervical myelopathy - Malignancy - Bilateral or more than one level radicular pain - Previous cervical fusion or laminectomy - Significant psychopathology

N total at baseline: I: 20 C: 21

Important prognostic factors: Age ± SD: I: 58.4 ± 16.2 C: 59.0 ± 13.8

Sex (%male): I: 55% C: 43%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention: PRF treatment: - At 42 degrees Celsius, the PRF stimulus was applied for 4 minutes, and then radiculography was carried out. |

Describe control: The control (CNRB) group received a mixture of 1 mL corticosteroids containing 5 mg betamethasone dipropionate and 2 mg betamethasone disodium phosphate, 1 mL 0.9% NaCl, and 1 mL of 2% lidocaine after radiculography. |

Length of follow-up: 6 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 1 Reasons: NR

Control: 2 Reasons: NR

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported, except loss-to-follow-up as above.

|

Outcome measures and effect size: Patient satisfaction Defined as rates of positive GPE (+2 or +3) 1 week I: 20% (4/20) C: 23.8% (5/21) 1 month I: 40% (8/20) C: 14.3% (3/21) 3 months I: 5.3% (1/19) C: 14.3% (3/21) 6 months I: 10.5% (2/19) C: 5.3% (1/19)

Complications Defined as the number of patients with complications I: 0 C: 0 |

Authors conclusion: Combining PRF and CNRB achieved superior outcomes to those accomplished by either CNRB or PRF alone.

Limitations: - Small sample size - Short follow-up to determine long-term effects

|

|

Chalermkitpanit, 2023 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital (KCMH), Bangkok, Thailand

Funding and conflicts of interest: The study was funded by a grant from Ratchadapisek-sompotch Fund, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand. The authors had no potential conflicts of interest to disclose. |

Inclusion criteria: - Age between 30-80 years. - Diagnosis of cervical spondylosis with radicular pain by an orthopaedic surgeon and a pain specialist. - Clinical examination compatible with MRI. - Moderate to severe cervical radicular pain rated by a NRS at least 4 out of 10. - Chronic pain >3 months despite conservative treatment.

Exclusion criteria: - Cervical radiculopathy with progressive weakness. - Radicular pain secondary to spinal tumor. - Patients with cardiac device implantation. - Ongoing local infection at the injection area or systemic infection. - Patients with bleeding disorders. - History of allergy to study medications.

N total at baseline: I: 20 C: 21

Important prognostic factors: Age ± SD: I: 48.9 ± 15.8 C: 56.3 ± 14.6

Sex (%male): I: 40% C: 38%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention: PRF treatment: - Treatment was done for 4 minutes following a positive sensory stimulation between 0.3 and 0.5 volts. After the PRF treatment, 1.5 mL of 2% lidocaine with 10 mg of dexamethasone was injected. |

Describe control: Steroid treatment: - A short bevel stimulating 22G-needle was placed and the sensory stimulation was confirmed. Then the same injectate was administered. |

Length of follow-up: 9 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 1 Reasons: not reported.

Control: - Reasons: -

Incomplete outcome data: No other than loss-to-follow-up reported above. |

Outcome measures and effect size: Pain NRS, mean (SD) I: 2.8 (2.7) C: 5.5 (2.6)

Functioning NDI, mean differences between PRF and steroid group 3 months: 23.0 (95%CI 9.6 to -36.4) 6 months: 23.8 (95%CI 4.2 to 43.3) |

Authors conclusion: PRF treatment exhibited a neuromodulation effect and is shown to be effective for patients with cervical radicular pain.

Limitations: - Small sample size. |

Risk of Bias

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? |

Was the allocation adequately concealed? |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented? Were patients/healthcare providers/data collectors/outcome assessors/data analysts blinded? |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent? |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting? |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias? |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure |

|

Van Zundert, 2007 |

Definitely yes

Reason: A computer-generated randomization list was used. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Independent observer provided the treating physician with a sealed envelope numbered in advance, which was opened in the operating room. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Patients, independent observer, data manager and neurologist were blinded. The healthcare provider was not blinded. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Only one (8%) participant was lost to follow-up before three months from the control group for a valid reason (surgery). |

Probably yes

Reason: No registration in register of clinical trials mentioned, but no reason to doubt that the report is free of selective outcome reporting. |

Definitely no

Reason: - Differences in baseline demographic characteristics. - Underpowering for different parameters, due to the low number of included participants. |

Some concerns (underpowering due to small sample size) |

|

Lee, 2016 |

Unknown

|

Unknown |

Unknown |

Probably no

Reason: five patients (12%) were lost to follow-up (no reason reported) and one patient dropped out due to a pain flare-up. |

Probably yes

Reason: No registration in register of clinical trials known. Study protocol has been written but is not available. |

Probably yes

Reason: - Small sample size. |

Some concerns (information is missing) |

|

Halim, 2017 |

Unknown |

Unknown |

Unknown |

Definitely no

Reason: three patients (15%) were lost to follow-up from PCN group (no reason reported), and seven (29%) patients were lost to follow-up from PRF group (no reason reported). |

Probably no

Reason: No registration in register of clinical trials mentioned. Some outcomes mentioned in the methods section are not reported in the results section. |

Probably yes

Reason: - Small sample size. |

High |

|

Wang, 2016 |

Definitely no

Reason: Patients were randomized according to the last number of their medical record number, which was generated by two research fellows. |

Definitely no

Reason: The same research fellows assigned participants to interventions. |

Definitely no

Reason: Data collectors (two nurses) were the only ones blinded. |

Probably yes

Reason: two patients (10%) were lost to follow-up from CNRB group (no reason), and one patient (5%) was lost to follow-up from PRF group (no reason). |

Probably yes

Reason: No registration in register of clinical trials known. Study protocol has been written but is not available. |

Probably yes

Reason: - Small sample size.

|

High |

|

Chalermkitpanit, 2023 |

Unknown |

Unknown |

Probably yes

Reason: Double-blinded RCT; patients and pain assessors were blinded. |

Probably yes

Reason: Only one (5%) participant was lost to follow-up at 1 month, but no reason was reported. |

Probably yes

Reason: No registration in register of clinical trials mentioned, but no reason to doubt that the report is free of selective outcome reporting. |

Probably yes

Reason: - Small sample size. |

Some concerns (information is missing) |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Van Zundert J, Huntoon M, Patijn J, Lataster A, Mekhail N, van Kleef M; Pain Practice. 4. Cervical radicular pain. Pain Pract. 2010 Jan-Feb;10(1):1-17. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2009.00319.x. Epub 2009 Oct 5. PMID: 19807874. |

Wrong publication type (review) |

|

Facchini G, Spinnato P, Guglielmi G, Albisinni U, Bazzocchi A. A comprehensive review of pulsed radiofrequency in the treatment of pain associated with different spinal conditions. Br J Radiol. 2017 May;90(1073):20150406. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20150406. Epub 2017 Feb 10. PMID: 28186832; PMCID: PMC5605093. |

No risk of bias assessment performed, and less recent compared to Vuka (2020) |

|

Kwak SG, Lee DG, Chang MC. Effectiveness of pulsed radiofrequency treatment on cervical radicular pain: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Aug;97(31):e11761. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011761. PMID: 30075599; PMCID: PMC6081162. |

All relevant studies are included in Vuka (2020) as well, which is a more recent SR |

|

Yang S, Chang MC. Efficacy of pulsed radiofrequency in controlling pain caused by spinal disorders: a narrative review. Ann Palliat Med. 2020 Sep;9(5):3528-3536. doi: 10.21037/apm-20-298. Epub 2020 Sep 7. PMID: 32921088. |

Wrong publication type (narrative review) |

|

Geurts JW, van Wijk RM, Stolker RJ, Groen GJ. Efficacy of radiofrequency procedures for the treatment of spinal pain: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2001 Sep-Oct;26(5):394-400. doi: 10.1053/rapm.2001.23673. PMID: 11561257. |

Wrong intervention (radiofrequency) |

|

Vanneste T, Van Lantschoot A, Van Boxem K, Van Zundert J. Pulsed radiofrequency in chronic pain. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2017 Oct;30(5):577-582. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000502. PMID: 28700369. |

Wrong publication type (review) |

|

Chua NH, Vissers KC, Sluijter ME. Pulsed radiofrequency treatment in interventional pain management: mechanisms and potential indications-a review. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2011 Apr;153(4):763-71. doi: 10.1007/s00701-010-0881-5. Epub 2010 Nov 30. PMID: 21116663; PMCID: PMC3059755. |

Includes only one relevant study that is also included in Vuka (2020), which is a more recent SR |

|

Niemistö L, Kalso E, Malmivaara A, Seitsalo S, Hurri H; Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Radiofrequency denervation for neck and back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the cochrane collaboration back review group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003 Aug 15;28(16):1877-88. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000084682.02898.72. PMID: 12923479. |

Wrong population (patients with cervical zygapophysial joint pain, cervicobrachial pain, lumbar zygapophysial joint pain and/or discogenic low back pain) |

|

Niemisto L, Kalso E, Malmivaara A, Seitsalo S, Hurri H. Radiofrequency denervation for neck and back pain. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(1):CD004058. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004058. PMID: 12535508. |

Duplicate |

|

Vallejo R, Benyamin RM, Aliaga L. Radiofrequency vs. pulse radiofrequency: The end of the controversy, Techniques in Regional Anesthesia and Pain Management. 2010; 14(3): 128-132. ISSN 1084-208doi.org/10.1053/j.trap.2010.06.003. |

Wrong publication type (review) |

|

Cohen SP, Hooten WM. Advances in the diagnosis and management of neck pain. BMJ. 2017 Aug 14;358:j3221. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3221. PMID: 28807894. |

Wrong publication type (review) |

|

Lee SH, Choi HH, Roh EY, Chang MC. Effectiveness of Ultrasound-Guided Pulsed Radiofrequency Treatment in Patients with Refractory Chronic Cervical Radicular Pain. Pain Physician. 2020 Jun;23(3):E265-E272. PMID: 32517402. |

Wrong study design (prospective outcome study) |

|

Tella P, Stojanovic M. Novel therapies for chronic cervical radicular pain: does pulsed radiofrequency have a role? Expert Rev Neurother. 2007 May;7(5):471-2. doi: 10.1586/14737175.7.5.471. PMID: 17492898. |

Wrong publication type (expert review) |

|

Xiao L, Li J, Li D, Yan D, Yang J, Wang D, Cheng J. A posterior approach to cervical nerve root block and pulsed radiofrequency treatment for cervical radicular pain: a retrospective study. J Clin Anesth. 2015 Sep;27(6):486-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2015.04.007. Epub 2015 Jun 4. PMID: 26051825. |

Wrong study design (retrospective) |

|

Snidvongs S, Mehta V. Pulsed radio frequency: a non-neurodestructive therapy in pain management. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2010 Jun;4(2):107-10. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e328339628a. PMID: 20440207. |

Wrong publication type (review) |

|

Hata J, Perret-Karimi D, Desilva C, Leung D. Pulsed Radiofrequency Current in the Treatment of Pain. Critical Reviews in Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2011 Jan;23(1):213-240. doi: 10.1615/CritRevPhysRehabilMed.v23.i1-4.150. |

Wrong publication type (review) |

|

van Boxem K, van Eerd M, Brinkhuizen T, Patijn J, van Kleef M, van Zundert J. Radiofrequency and pulsed radiofrequency treatment of chronic pain syndromes: the available evidence. Pain Pract. 2008 Sep-Oct;8(5):385-93. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2008.00227.x. Epub 2008 Aug 19. Erratum in: Pain Pract. 2010 Mar-Apr;10(2):164. Brinkhuize, Tjinta [corrected to Brinkhuizen, Tjinta]. PMID: 18721175. |

Wrong publication type (review) |

|

Malik K, Benzon HT. Radiofrequency applications to dorsal root ganglia: a literature review. Anesthesiology. 2008 Sep;109(3):527-42. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318182c86e. PMID: 18719452. |

Wrong publication type (review) |

|

Van Zundert J, Harney D, Joosten EA, Durieux ME, Patijn J, Prins MH, Van Kleef M. The role of the dorsal root ganglion in cervical radicular pain: diagnosis, pathophysiology, and rationale for treatment. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2006 Mar-Apr;31(2):152-67. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2005.11.014. PMID: 16543102. |

Wrong publication type (review) |

|

Choi GS, Ahn SH, Cho YW, Lee DK. Short-term effects of pulsed radiofrequency on chronic refractory cervical radicular pain. Ann Rehabil Med. 2011 Dec;35(6):826-32. doi: 10.5535/arm.2011.35.6.826. Epub 2011 Dec 30. PMID: 22506211; PMCID: PMC3309390. |

Wrong study design (prospective follow-up study) |

|

Vuka I, Marciuš T, Došenović S, Ferhatović Hamzić L, Vučić K, Sapunar D, Puljak L. Efficacy and Safety of Pulsed Radiofrequency as a Method of Dorsal Root Ganglia Stimulation in Patients with Neuropathic Pain: A Systematic Review. Pain Med. 2020 Dec 25;21(12):3320-3343. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnaa141. PMID: 32488240. |

Includes only two relevant studies that were found in the systematic search as well and are described separately. |

|

Lee SH, Choi HH, Chang MC. Comparison between ultrasound-guided monopolar and bipolar pulsed radiofrequency treatment for refractory chronic cervical radicular pain: A randomized trial. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2022;35(3):583-588. doi: 10.3233/BMR-201842. PMID: 34542059. |

Wrong comparison (monopolar PRF versus bipolar PRF) |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 01-07-2024

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodules is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de ‘samenstelling van de werkgroep’) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met een CRS.

WERKGROEP

- Mevr. dr. Carmen Vleggeert-Lankamp (voorzitter), neurochirurg, NVvN

- Dhr. dr. Ruben Dammers, neurochirurg, NVvN

- Mevr. drs. Martine van Bilsen, neurochirurg, NVvN

- Dhr. drs. Maarten Liedorp, neuroloog, NVN

- Mevr. drs. Germine Mochel, neuroloog, NVN

- Mevr. dr. Akkie Rood, orthopedisch chirurg, NOV

- Dhr. dr. Erik Thoomes, fysiotherapeut en manueel therapeut, KNGF/NVMT

- Dhr. prof. dr. Jan Van Zundert, hoogleraar Pijngeneeskunde, NVA

- Dhr. Leen Voogt, ervaringsdeskundige, Nederlandse Vereniging van Rugpatiënten ‘de Wervelkolom’

KLANKBORDGROEP

- Mevr. Elien Nijland, ergotherapeut/handtherapeut, EN

- Mevr. Meimei Yau, oefentherapeut, VvOCM

Met ondersteuning van:

- Mevr. dr. Charlotte Michels, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Mevr. drs. Beatrix Vogelaar, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Naam lid werkgroep |

Hoofdfunctie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Carmen Vleggeert-Lankamp (voorzitter) |

Neurochirurg, Leiden Universitair Medisch Centrum, Leiden

|

* Medisch Manager Neurochirurgie Spaarne Gasthuis, Hoofdorp/ Haarlem, gedetacheerd vanuit LUMC (betaald) * Boardmember Eurospine, chair research committee |

*Niet anders dan onderzoeksleider in projecten naar etiologie van en uitkomsten in het CRS. |

Geen actie |

|

Akkie Rood |

Orthopedisch chirurg, Sint Maartenskliniek, Nijmegen |

Lid NOV, DSS, NvA |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Erik Thoomes |

Fysio-Manueel therapeut / praktijkeigenaar, Fysio-Experts, Hazerswoude |

*Promovendus / wetenschappelijk onderzoeker Universiteit van Birmingham, UK,School of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation Sciences, |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Germine Mochel |

Neuroloog, DC klinieken (loondienst) |

Lid werkgroep pijn NVN Lid NHV en VNHC |

*Dienstverband bij DC klinieken, alwaar behandeling/diagnostiek patiënten CRS

|

Geen actie |

|

Jan Van Zundert |

*Anesthesioloog-pijnspecialist. |

Geen |

Geen financiering omtrent projecten die betrekking hebben op cervicaal radiculair lijden (17 jaar geleden op CRS onderwerk gepromoveerd, nadien geen PhD CRS-projecten begeleidt).

|

Geen actie |

|

Leen Voogt |

*Ervaringsdeskundige CRS. *Voorzitter Nederlandse Vereniging van Rugpatiënten 'de Wervelkolom' (NVVR) |

Vrijwilligerswerk voor de patiëntenvereniging (onbetaald). |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Maarten Liedorp |

Neuroloog in loondienst (0.6 fte), ZBC Kliniek Lange Voorhout, Rijswijk |

*lid oudergeleding MR IKC de Piramide (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Martine van Bilsen |

Neurochirurg, Radboudumc, Nijmegen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Ruben Dammers |

Neurochirurg, ErasmusMC, Rotterdam |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Naam lid klankbordgroep |

Hoofdfunctie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Meimei Yau |

Praktijkhouder Yau Oefentherapeut, Oefentherapeut Mensendieck, Den Haag. |

Geen |

Kennis opdoen, informatie/expertise uitwisselen met andere disciplines, oefentherapeut vertegenwoordigen. KP register |

Geen actie |

|

Vera Keil |

Radioloog, AmsterdamUMC, Amsterdam. Afgevaardigde NVvR Neurosectie |

Geen |

Als radioloog heb ik natuurlijk een interesse aan een sterke rol van de beeldvorming. |

Geen actie |

|

Elien Nijland |

Ergotherapeut/hand-ergotherapeut (totaal 27 uur) bij Treant zorggroep (Bethesda Hoogeveen) en Refaja ziekenhuis (Stadskanaal) |

Voorzitter Adviesraad Hand-ergotherapie (onbetaald) |

|

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door een afgevaardigde van de Nederlandse Vereniging van Rugpatiënten ‘de Wervelkolom’ te betrekken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen (zie kop ‘Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten’). De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Nederlandse Vereniging van Rugpatiënten ‘de Wervelkolom’ en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Pulsed Radiofrequency |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet en het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met CRS. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door Ergotherapie Nederland, het Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap, Nederlandse Vereniging van Ziekenhuizen, Nederlandse Vereniging van Revalidatieartsen, Vereniging van Oefentherapeuten Cesar en Mensendieck, Zorginstituut Nederland, Zelfstandige Klinieken Nederland, via enquête. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

NHG, 2018. NHG-Standaard Pijn (M106). Published: juni 2018. Laatste aanpassing: Laatste aanpassing: september 2023. Link: https://richtlijnen.nhg.org/standaarden/pijnhttps://richtlijnen.nhg.org/standaarden/pijn

NVN, 2020. Richtlijn Lumbosacraal Radiculair Syndroom (LRS). Beoordeeld: 21-09-2020. Link: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/lumbosacraal_radiculair_syndroom_lrs/startpagina_-_lrs.html

Radhakrishnan K, Litchy WJ, O'Fallon WM, Kurland LT. Epidemiology of cervical radiculopathy. A population-based study from Rochester, Minnesota, 1976 through 1990. Brain. 1994 Apr;117 ( Pt 2):325-35. doi: 10.1093/brain/117.2.325. PMID: 8186959.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.