Nekkraag

Uitgangsvraag

Welke rol heeft een nekkraag in de behandeling van CRS?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg het dragen van een half harde halskraag in de eerste zes weken na het ontstaan bij patiënten met een cervicaal radiculair syndroom om nekpijn te verminderen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

In deze module worden verschillende fysiotherapeutische interventies geëvalueerd als behandeling van patiënten met cervicaal radiculair syndroom (CRS). In totaal zijn er twintig RCTs gevonden die de half harde halskraag, cervicale tractie, oefentherapie, neurodynamische mobilisatie of manuele therapie onderzochten. De bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten ‘disability’, ‘functioneren’, en ‘kwaliteit van leven’ was voor alle interventies zeer laag, behalve voor de interventie oefentherapie. Voor oefentherapie resulteerde de bewijskracht in laag m.b.t. de cruciale uitkomstmaten.

De zeer lage bewijskracht betekent dat andere studies kunnen leiden tot nieuwe inzichten. De studiepopulaties en interventies waren niet altijd goed met elkaar te vergelijken en daarnaast bevatten de studies enkele methodologische beperkingen. Daarom kunnen er op basis van de literatuur geen harde conclusies geformuleerd worden.

Bij patiënten met een CRS is er sprake van bewegend disfunctioneren mede op basis van de aanwezige radiculaire (en soms neuropathische) pijn en andere sensorische en motorische disfuncties vanwege de radiculopathie. Na het verdwijnen van de oorzaak van een CRS, verdwijnen niet altijd alle disfuncties zonder een specifiek daarop gerichte interventie (Hides, 1996). Fysiotherapie kan een aanvulling zijn op het natuurlijk herstelproces bij patiënten met een CRS en, ook ná een eventuele chirurgische interventie, essentieel zijn in het herstellen van ontstane disfuncties zoals spierkrachtverlies. Een fysiotherapeutisch behandelprogramma is altijd multimodaal (Thoomes, 2022).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Het is de mening van de werkgroep dat de beslissing om fysiotherapeutische begeleiding te zoeken vooral aan de patiënt over moet worden gelaten. Als de patiënt besluit zich te laten begeleiden door een fysiotherapeut, is het wel wenselijk dat de behandelend fysiotherapeut ruime ervaring heeft met het behandelen en begeleiden van patiënten met een CRS, om onnodige exacerbaties of bijwerkingen te voorkomen.

De belangrijkste doelen van de fysiotherapeutische interventies zijn afhankelijk van het stadium waar de aandoening zich in bevindt. In de initiële, reactieve fase waarin de reactiviteit van de zenuwwortel nog voorop staat, zal de focus vooral liggen op uitleg en advies hoe de verergering van klachten het best te voorkomen is. Daarbij zijn correct gebruik van effectieve pijnmedicatie (in overleg met de (huis)arts) en wellicht het overwegen van het gebruik van een half harde halskraag in de eerste drie tot maximaal 6 weken (met een bijpassend afbouw beleid) van belang. Self-empowerment van de patiënt is nu ook al van belang. In de subacute fase zal de focus van de interventies verschuiven naar een meer actieve aanpak, rekening houdend met de belastbaarheid van de individuele patiënt. Hierin kunnen de interventies die de werkgroep voorstelt allemaal een rol spelen. In de eindfase van herstel verschuift de focus van de fysiotherapeutische interventies nog meer naar zelfredzaamheid van de patiënt en het geven van de tools waarmee hij/zij zijn eigen belastbaarheid en individuele disfuncties zelf actief verder gestructureerd kan verbeteren.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er is weinig bekend over de kosteneffectiviteit van fysiotherapie bij patiënten met CRS (Alvin, 2014). In 2019 vergeleek één studie chirurgie (ACDF) met conservatief beleid van cervicale epidurale injecties in combinatie met fysiotherapie (Rihn, 2019). Deze analyses suggereerde dat ACDF kosten-effectiever is ($6.768) in vergelijking met cervicale epidurale injecties in combinatie met fysiotherapie (Rihn, 2019). Daarnaast is onderzocht dat het merendeel van de kosten gerelateerd aan CRS, veroorzaakt wordt door het diagnostisch traject (Barton, 2019).

Davidson (2020) rapporteerde de kosten van niet-operatieve therapie voorafgaand aan ACDF-chirurgie in Amerika. De totale directe kosten van alle niet-operatieve therapieën voorafgaand aan ACDF-chirurgie waren $17.255.828 met $1.278 aan fysiotherapie per patiënt als hoogste gemiddelde gefactureerde dollars.

Op basis van kostenanalyses (Barton, 2019; Rihn, 2019; Davidson, 2020) is het dus aannemelijk dat vanuit het oogpunt van kosteneffectiviteit, fysiotherapie aanbevolen kan worden. Daarbij moet opgemerkt worden dat voor sommige subgroepen een andere overweging kan gelden en de beste managementstrategie bij elke patiënt individueel beoordeeld moet worden. Zo kunnen de volgende variabelen geassocieerd zijn met een beter resultaat van de operatie: korte duur van pijn, vrouwelijk geslacht, lage gezondheidskwaliteit, hoge niveaus van angst vanwege nek-/armpijn, lage zelfredzaamheid en een hoge mate van angst vóór de behandeling (Engquist, 2015). In de module ‘Timing chirurgische behandeling’ spreekt de werkgroep zich hier ook nog verder over uit.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Op het gebied van aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie voorziet de werkgroep geen grote uitdagingen. Patiënten met een CRS ervaren klachten van het bewegend functioneren. Fysiotherapeuten zijn de experts in het bewegend (dis)functioneren. Zeker gezien de direct toegankelijke positie in de eerstelijnszorg, zijn zij daarmee bij uitstek geschikt om een belangrijke rol in te spelen in een conservatieve behandelstrategie.

De beschreven interventies in deze module vallen in principe allemaal binnen het beroepscompetentieprofiel van de fysiotherapie (KNGF, 2021). Echter worden niet alle interventies in het basis curriculum van de algemeen fysiotherapeut gedoceerd. Onder andere de manipulaties en de neurodynamische mobilisaties maken deel uit van de specialisatie opleiding tot manueel therapeut. Zo worden manueel therapeuten opgeleid tot het behandelen van complexe problemen van het bewegen (dis)functioneren (KNGF, 2021; NVMT, 2023). De werkgroep adviseert daarom om bij het inzetten van een conservatief beleid, patiënten ter overweging mee te geven een manueel therapeut te consulteren.

Hoewel fysiotherapeuten direct toegankelijk zijn, wordt de bekostiging voor een groot deel vanuit de Aanvullende Verzekering (AV) vergoed. Slechts een beperkt deel van de zogenaamde “chronische aandoeningen” (de zgn. lijst Borst of Bijlage 1. van het Besluit zorgverzekering) wordt vanuit de Basisverzekering vergoed. Niet iedereen in Nederland heeft een AV zodat, dus vanuit financieel oogpunt bekeken hebben niet alle patiënten vergelijkbare toegang heeft tot fysiotherapie. Dit kan een mogelijke barrière zijn voor patiënten.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomsten ‘pijn’, ‘beperkingen’, ‘kwaliteit van leven’, ‘terugkeer in het arbeidsproces’ en ’gebruik van opiaten’ op basis van beschikbare literatuur is zeer laag (Aksoy, 2018; Kuijper, 2009). Ofwel, het is onduidelijk is of een half-harde halskraag een gunstig effect heeft bij patiënten met CRS. De werkgroep acht op basis van expert opinion in combinatie met het bewijs uit één studie (Kuijper, 2009) van goede methodologische kwaliteit dat het dragen van een half harde halskraag in de acute fase en de eerste 3-6 weken bij ernstige pijnklachten een te overwegen interventie is.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Er is grote variatie in de afwachtende, niet-chirurgische aanpak bij patiënten met een cervicaal radiculair syndroom, momenteel is onduidelijk welke rol fysiotherapie heeft in de behandeling van patiënten met een CRS. Het natuurlijk beloop van een CRS is meestal gunstig (Wong, 2014). Door fysiotherapie wordt gepoogd het natuurlijke beloop van een CRS te bespoedigen. Doel van de fysiotherapeutische behandeling is het verminderen van klachten en (daarmee) het terugkeren in de activiteiten van het dagelijks leven. In deze module worden verschillende, in recente wetenschappelijke literatuur voorgestelde, fysiotherapeutische interventies geëvalueerd.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1a. Cervical collar: Pain (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is uncertain about a difference in effect of soft or semi-rigid collars on pain, compared to a wait-and-see approach, exercise, or in addition to exercise, in patients with cervical radiculopathy. No type of collar (soft or semi-rigid) seems to be preferential over the other with regard to pain.

Source: Aksoy (2018), Kuijper (2009) |

1b. Cervical collar: Disability (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is uncertain about a difference in effect of soft or semi-rigid collars on disability, compared to a wait-and-see approach, exercise, or in addition to exercise, in patients with cervical radiculopathy. A soft collar is suggested to be less debilitating than a semi-rigid collar.

Source: Aksoy (2018), Kuijper (2009) |

1c. Cervical collar: Function (critical)

|

- GRADE |

The outcomes function was not reported and could not be graded. |

1d. Cervical collar: Quality of life (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of a soft or semi-rigid cervical collar in addition to exercise therapy on quality of life, in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Source: Aksoy (2018) |

1e. Cervical collar: Return to work (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about a difference in effect of a semi-rigid cervical collar compared to exercise therapy or a wait-and-see approach on sick leave, in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Source: Kuijper (2009) |

1f. Cervical collar: Drug consumption (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about a difference in effect of a semi-rigid cervical collar compared to exercise therapy or a wait-and-see approach on opiate use, in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Source: Kuijper (2009) |

1g. Cervical collar: Psychosocial outcomes (important), 1h. Cervical collar: Adverse effects (important)

|

- GRADE |

The psychosocial outcomes and adverse effects were not reported and could not be graded.

Source: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

1. Cervical collar

Description of studies for treatment with a cervical collar

Two RCTs reported on outcomes after the treatment with a cervical collar. Detailed information on both studies can be found in the Evidence Table.

Aksoy (2018) investigated the effect of soft and semi-rigid cervical collars in patients with acute cervical radiculopathy. Adult patients diagnosed with cervical radiculopathy and neck pain ≥4 on a visual analog scale (VAS) were randomized into three groups: a group with a soft cervical collar plus home exercises (Group 1, n = 30), a semi-rigid cervical collar plus home exercises (Group 2, n = 26), or a home exercise-only group (Group 3, n = 29). The collars were worn 8 hours per day, every day in the first 2 weeks, after which collar time was reduced every other day by one hour; until collar wearing was discontinued after 4 weeks. The exercises consisted of cervical isometric strength, cervical mobilisation, and shoulder pro- and retraction exercises, 2 times 10 repetitions, twice a day, every day, for 6 weeks. After 6 weeks, pain intensity (through VAS), disability (through the Neck Disability Index, NDI), and quality of life (through the Short-Form 36, SF-36) were measured.

To evaluate the effectiveness of treatment with a semi-hard collar or physiotherapy, Kuijper (2009) randomized patients with recent onset (<1 month) cervical radiculopathy into either a treatment group with a semi-hard collar and advice to rest for 3 to 6 weeks (n = 69), or a treatment group with biweekly physiotherapy sessions and home exercises for 6 weeks (n = 70), or a wait-and-see group who could continue daily activities without specific treatment (n = 66). After six weeks, the outcomes assessed were neck and arm pain (VAS), disability (NDI), return to work, and drug consumption.

Results

Outcomes are assessed below for the following comparisons:

|

Passive comparison (C1):

|

Active comparison (C2):

|

1a. Neck pain

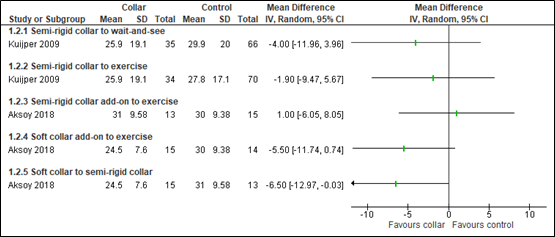

Neck pain was measured by both authors with a VAS (higher scores representing more pain), at six weeks after randomization to treatment. Outcomes reported on a 100 mm scale have been converted to scores on a 10 cm scale. The different comparisons performed in the studies are shown in Figure 1a. For the studies that used more than one study arm for comparison (i.e. >2 study arms), the population in the study arm was divided by the number of comparisons in which it was used (e.g. the semi-rigid collar arm of Kuijper, 2009 is used in comparison 1.1.1. and 1.1.2., therefore the number of participants in that study arm is divided over both comparisons to prevent accounting for the same population more than once.

Due to the heterogeneity in control groups, no pooled estimate for the found results in pain was calculated.

Figure 1a. Studies comparing treatment with collar to wait-and-see (C1) or exercise/other type of collars (C2), for the outcome neck-pain (using the Visual Analog Scale, VAS).

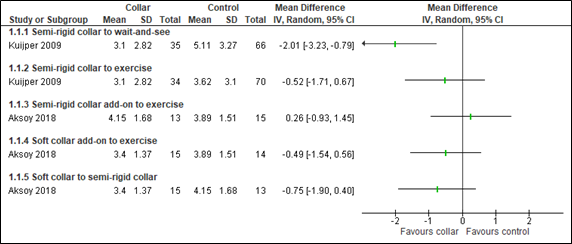

1b. Disability

Disability was measured by both authors using the Neck Disability Index (NDI). Disability increases with increasing score (maximum score of 100). Results are depicted in Figure 1b. For those study arms used more than once for comparison, the population is divided by the number of comparisons in which it was used. Due to the heterogeneity in comparisons and control groups, no pooled estimate was calculated.

Figure 1b. Studies comparing treatment with collar to wait-and-see (C1) or exercise/other type of collars (C2), for the outcome disability (using the Neck Disability Index, NDI).

1c. Function

The outcome function was not reported in the studies.

1d. Quality of life

Aksoy (2018) reported on quality of life outcomes using the SF-36, which can generate two summary scores: the Physical Component Score (PCS) and Mental Component Score (MCS), on a 100-point scale.

Regarding PCS, a mean difference for the group with a semi-rigid collar as add-on to exercise – at six weeks of follow-up – was observed of -1.60 [95%CI -4.62 to 1.42] compared to the exercise-only group. For the soft collar group compared to exercise-only group, this difference was -3.80 [95%CI -6.54 to -1.06].

Regarding the MCS, a mean difference for a semi-rigid collar as add-on to exercise versus exercise only, of -2.50 [95%CI -5.40 to 0.40] at six weeks was observed. The soft collar as add-on to exercise showed only a difference of -0.60 [95%CI -3.03 to 1.83].

The mean differences between collar type (soft versus semi-rigid) were 1.90 [95%CI -0.55 to 4.35] for PCS and -2.20 [95%CI -5.14 to 0.74] for MCS. All differences in quality of life (PCS and MCS) were not clinically relevant.

1e. Return to work

Kuijper (2009) reported on partial or complete sick leave after six weeks. A no-significant difference in partial or complete sick leave of 20 (out of 68, 29%), 30 (out of 67, 45%), and 24 (out of 63, 38%) patients was observed in the collar, physiotherapy, and control group, respectively.

1f. Drug consumption

Kuijper (2009) reported on the use of opiates after six weeks. In the collar group, 13 patients (out of 68, 19%) used opiates at that time point. In the physiotherapy group, 13 patients (out of 66, 20%), and 16 patients in the control group (out of 63, 25%) used opiates, respectively. The opiate use between these groups did not differ with statistical significance.

1g. Psychosocial outcomes, 1h. Adverse effects

The outcomes psychosocial outcomes, function, and adverse effects were not reported in the studies.

Level of evidence of the literature

1a. Cervical collar: Pain (critical)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of selective outcome reporting and possible selection bias (-1, risk of bias); conflicting results and methodological heterogeneity between studies (-1, inconsistency); and the low number of included patients with the confidence intervals crossing the border of clinical relevance (-1, imprecision).

1b. Cervical collar: Disability (critical)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure disability was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of selective outcome reporting and possible selection bias (-1, risk of bias); conflicting results and methodological heterogeneity between studies (-1, inconsistency); and the low number of included patients with the confidence intervals crossing the border of clinical relevance (-1, imprecision).

1c. Cervical collar: Function (critical)

The outcome function was not reported and could not be graded.

1d. Cervical collar: Quality of life (critical)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of inadequate allocation concealment, per protocol analysis, possible selective outcome reporting and possible selection bias (-2, risk of bias); and the inclusion of a single study with a low number of patients (-1, imprecision).

1e. Cervical collar: Return to work (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure return to work was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of deviation from protocol in outcome reporting and possible selection bias (-1, risk of bias); and the inclusion of a single study with a low number of patients (-2, imprecision).

1f. Cervical collar: Drug consumption (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure drug consumption was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of deviation from protocol in outcome reporting and possible selection bias (-1, risk of bias); and the inclusion of a single study with a low number of patients (-2, imprecision).

1g. Cervical collar: Psychosocial outcomes (important), 1h. Cervical collar: Adverse effects (important)

The psychosocial outcomes and adverse effects were not reported and could not be graded.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effect of physiotherapy compared to watchful waiting and/or other forms of physiotherapy in patients with cervical radiculopathy?

| P: | Patients with cervical radiculopathy |

| I: | Physiotherapy |

| C: |

C1. Usual care/ watchful waiting/ placebo or sham (passive control) C2. Other forms of physiotherapy (active control) |

| O: | Pain, disability, function, quality of life, return to work, psychosocial outcomes, drug consumption, adverse effects |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered pain, disability, function, and quality of life as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and return to work, drug consumption, psychosocial outcomes, and adverse effects as an important outcome measure for decision making.

The working group did not define the outcome measures listed above a priori, but used the definitions used in the described study.

The working group defined a 10% difference for continuous outcome measures (weighted mean difference), 10% for dichotomous outcome measures informing on relative risk (0.91 ≤ RR ≥ 1.1), and standardized mean difference (SMD=0,2 (small); SMD=0,5 (medium); SMD=0,8 (large). This decision was based on the minimal important change scores described in the article by Ostelo (2008), in accordance with the Dutch Lumbosacral Radicular syndrome guideline (2020).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from January 1st, 2000 until April 25th, 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the Methods tab. The systematic literature search resulted in 339 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic review and/or meta-analysis, with detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment, and results of individual studies available; or randomized controlled trial (RCT);

- Patients aged ≥ 18 years;

- studies including ≥ 30 (15 in each study arm) patients;

- studies according to the PICO. Any type of physiotherapy performed in the Netherlands as an intervention, and described placebo/ sham, usual care, no treatment, or other forms of physiotherapy performed in the Netherlands as a comparison; and

- full-text English or Dutch language publication.

A total of 57 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text 37 studies were excluded (see the Table with reasons for exclusion under the Methods tab), and 20 studies were included.

Results

Twenty RCTs were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables. The results are analysed for five different intervention types, in line with the formulated sub questions:

- cervical collar

- cervical traction

- exercise

- neurodynamic mobilisation

- manual therapy

Table 1 gives a summary of the different measures or instruments used for the assessment of analysed outcomes.

Table 1. Summary of instruments used for analysed outcome measures.

|

Outcome |

Instrument |

Abbreviation |

Explanation |

Scale |

|

Pain |

Visual Analog Scale |

VAS |

Line on which patients can indicate their pain from 0 (no pain) to 100 (worst pain imaginable) |

0 to 100mm or 10cm |

|

Numerical (Pain) Rating Scale |

NR(P)S |

An 11-point numerical scale on which patients can indicate their pain from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable) |

0 to 10 |

|

|

Disability |

Neck Disability Index |

NDI |

Ten 5-point questions, after which total score is multiplied by 2 (seldom exceptions). Disability increases with increasing score. |

0 to 100 (or seldom: 0 to 50) |

|

Patient-Specific Functional Scale |

PSFS |

Self-administered questionnaire in which patients are asked to identify three to five activities that are difficult to perform and rate them from 0 (unable to perform activity) to 10 (able to perform activity). Summed score or the average score of three is used. |

0 to 10, 0 to 30 or 0 to 50 |

|

|

Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder and Hand |

QuickDASH |

Self-administered questionnaire with 11 items (3 for symptoms, 8 for function), which can be scored from 1 (no difficulty) to 5 (extreme difficulty/unable to do). Score is calculated as {(sum of scored items/number of items)-1} x25 |

0 to 100 |

|

|

Function |

Range of Motion |

ROM |

Measuring the mobility angles of the cervical spine with a goniometer. |

-180° to 180° |

|

Quality of Life |

Short Form 36 |

SF-36 |

A multidimensional instrument consisting of 36 questions; higher scores indicating a better health status. It can generate 2 summary scores: Physical (PCS) and Mental Component Score (MCS). |

0 to 100 |

|

EuroQoL-5D |

EQ-5D |

This questionnaire generates an index score based on 5 questions on quality of life, and has a VAS for current health state. Higher scores represent better (perceived) health. |

Index: 0 to 1 VAS: 0 to 100 |

|

|

Psycho-social outcomes |

Fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire |

FABQ |

A questionnaire with 16 items scored on a 7-point scale, assessing the patients’ fear-avoidance beliefs about how physical activity and work affect their pain. The points from all questions are summed to a total score, with higher scores indicating more fear-avoidance behaviours. |

0 to 96 |

Referenties

- Aksoy MK, Altan L, Güner, A. The effectiveness of soft and semi-rigid cervical collars on acute cervical radiculopathy. Eur Res J. 2017 Sep; DOI: 10.18621/eurj.332251

- Alvin MD, Qureshi S, Klineberg E, Riew KD, Fischer DJ, Norvell DC, Mroz TE. Cervical degenerative disease: systematic review of economic analyses. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014 Oct 15;39(22 Suppl 1):S53-64. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000547. PMID: 25299260.

- Ayub A, Osama M, Ahmad S. Effects of active versus passive upper extremity neural mobilisation combined with mechanical traction and joint mobilisation in females with cervical radiculopathy: A randomized controlled trial. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2019;32(5):725-730. doi: 10.3233/BMR-170887. PMID: 30664500.

- Barton C, Kalakoti P, Bedard NA, Hendrickson NR, Saifi C, Pugely AJ. What Are the Costs of Cervical Radiculopathy Prior to Surgical Treatment? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2019 Jul 1;44(13):937-942. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002983. PMID: 31205171.

- Basson A, Olivier B, Ellis R, Coppieters M, Stewart A, Mudzi W. The Effectiveness of Neural Mobilization for Neuromusculoskeletal Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017 Sep;47(9):593-615. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2017.7117. Epub 2017 Jul 13. PMID: 28704626.

- Basson CA, Stewart A, Mudzi W, Musenge E. Effect of Neural Mobilisation on Nerve-Related Neck and Arm Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Physiother Can. 2020 Nov 1;72(4):408-419. doi: 10.3138/ptc-2018-0056. PMID: 35110815; PMCID: PMC8781504.

- Mechanical and Manual Traction combined with mobilisation and exercise therapy in Patients with Cervical Radiculopathy. Pak J Med Sci. 2016 Jan-Feb;32(1):31-4. doi: 10.12669/pjms.321.8923. PMID: 27022340; PMCID: PMC4795884.

- Davison MA, Lilly DT, Eldridge CM, Singh R, Bagley C, Adogwa O. Regional differences in prolonged non-operative therapy utilization prior to primary ACDF surgery. J Clin Neurosci. 2020 Oct;80:143-151. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.07.056. Epub 2020 Aug 19. PMID: 33099337.

- Dedering Å, Peolsson A, Cleland JA, Halvorsen M, Svensson MA, Kierkegaard M. The Effects of Neck-Specific Training Versus Prescribed Physical Activity on Pain and Disability in Patients With Cervical Radiculopathy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018 Dec;99(12):2447-2456. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.06.008. Epub 2018 Jul 4. PMID: 30473018.

- Diab AA, Moustafa IM. The efficacy of forward head correction on nerve root function and pain in cervical spondylotic radiculopathy: a randomized trial. Clin Rehabil. 2012 Apr;26(4):351-61. doi: 10.1177/0269215511419536. Epub 2011 Sep 21. PMID: 21937526.

- Engquist M, Löfgren H, Öberg B, Holtz A, Peolsson A, Söderlund A, Vavruch L, Lind B. Factors Affecting the Outcome of Surgical Versus Nonsurgical Treatment of Cervical Radiculopathy: A Randomized, Controlled Study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015 Oct 15;40(20):1553-63. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001064. PMID: 26192721.

- FTK, 2024. Farmacotherapeutisch Kompas > Indicaties > Pijn. Toegang op 21-02-2024. Link: https://www.farmacotherapeutischkompas.nl/bladeren/indicatieteksten/pijn#pijn_advieshttps://www.farmacotherapeutischkompas.nl/bladeren/indicatieteksten/pijn#pijn_advies

- Fritz JM, Thackeray A, Brennan GP, Childs JD. Exercise only, exercise with mechanical traction, or exercise with over-door traction for patients with cervical radiculopathy, with or without consideration of status on a previously described subgrouping rule: a randomized clinical trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014 Feb;44(2):45-57. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2014.5065. Epub 2014 Jan 9. PMID: 24405257.

- Hassan F, Osama M, Ghafoor A, Yaqoob MF. Effects of oscillatory mobilisation as compared to sustained stretch mobilisation in the management of cervical radiculopathy: A randomized controlled trial. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2020;33(1):153-158. doi: 10.3233/BMR-170914. PMID: 31127753.

- Hides JA, Richardson CA, Jull GA. Multifidus muscle recovery is not automatic after resolution of acute, first-episode low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996 Dec 1;21(23):2763-9. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199612010-00011. PMID: 8979323.

- Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005 Apr 20;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. PMID: 15840177; PMCID: PMC1097734.

- Ibrahim AO, Fayaz NA, Abdelazeem AH, Hassan KA. The effectiveness of tensioning neural mobilisation of brachial plexus in patients with chronic cervical radiculopathy: a randomized clinical trial. Physiother Quart. 2021; 29(1): 12-16. doi: 10.5114/pq.2020.96419.

- Kayiran T, Turhan B. The effectiveness of neural mobilisation in addition to conservative physiotherapy on cervical posture, pain and functionality in patients with cervical disc herniation. Advances in Rehabilitation. 2021 Jul; 35(3): 8-16. doi: 10.5114/areh.2021.107788.

- <em>KNGF, 2024. KNGF Beroepsprofiel Fysiotherapeut: Over het vakgebied en rollen en competenties van de fysiotherapeut. Gepubliceerd: Maart 2021. Link:

https://www.kngf.nl/binaries/content/assets/kngf/onbeveiligd/vak-en-kwaliteit/beroepsprofiel/kngf_beroepsprofiel-fysiotherapeut_2024 - Kim DG, Chung SH, Jung HB. The effects of neural mobilisation on cervical radiculopathy patients' pain, disability, ROM, and deep flexor endurance. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2017 Sep 22;30(5):951-959. doi: 10.3233/BMR-140191. PMID: 28453446.

- Kuijper B, Tans JT, Beelen A, Nollet F, de Visser M. Cervical collar or physiotherapy versus wait and see policy for recent onset cervical radiculopathy: randomised trial. BMJ. 2009 Oct 7;339:b3883. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3883. PMID: 19812130; PMCID: PMC2758937.

- Moustafa IM, Diab AA. Multimodal treatment program comparing 2 different traction approaches for patients with discogenic cervical radiculopathy: a randomized controlled trial. J Chiropr Med. 2014 Sep;13(3):157-67. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2014.07.003. PMID: 25225464; PMCID: PMC4161715.

- NVMT, 2023. Beroepsprofiel Manueel Therapeut. Nieuwsbericht: 13 juni 2023. Link: https://nvmt.kngf.nl/article/kennisbank-nvmt/kwaliteit/beroepsprofiel-manueel-therapeut

- Ojoawo AO, Olabode AD. Comparative effectiveness of transverse oscillatory pressure and cervical traction in the management of cervical radiculopathy: A randomized controlled study. Hong Kong Physiother J. 2018 Dec;38(2):149-160. doi: 10.1142/S1013702518500130. Epub 2018 Aug 14. PMID: 30930587; PMCID: PMC6405355.

- Ostelo RW, Deyo RA, Stratford P, et al. Interpreting change scores for pain and functional status in low back pain: towards international consensus regarding minimal important change. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;1;33(1):90-4.

- Rihn JA, Bhat S, Grauer J, Harrop J, Ghogawala Z, Vaccaro AR, Hilibrand AS. Economic and Outcomes Analysis of Recalcitrant Cervical Radiculopathy: Is Nonsurgical Management or Surgery More Cost-Effective? J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019 Jul 15;27(14):533-540. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00379. PMID: 30407977.Rodríguez-Sanz D, Calvo-Lobo C, Unda-Solano F, Sanz-Corbalán I, Romero-Morales C, López-López D. Cervical Lateral Glide Neural Mobilisation Is Effective in Treating Cervicobrachial Pain: A Randomized Waiting List Controlled Clinical Trial. Pain Med. 2017 Dec 1;18(12):2492-2503. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnx011. PMID: 28340157.

- Savva C, Korakakis V, Efstathiou M, Karagiannis C. Cervical traction combined with neural mobilisation for patients with cervical radiculopathy: A randomized controlled trial. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2021 Apr;26:279-289. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2020.08.019. Epub 2020 Sep 2. PMID: 33992259.

- Savva C, Giakas G, Efstathiou M, Karagiannis C, Mamais I. Effectiveness of neural mobilisation with intermittent cervical traction in the management of cervical radiculopathy: a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Osteopathic Medicine. 2016 Sep;21:19-28. doi: 10.1016/j.ijosm.2016.04.002

- Shafique S, Ahmad S, Shakil-Ur-Rehman S. Effect of Mulligan spinal mobilisation with arm movement along with neurodynamics and manual traction in cervical radiculopathy patients: A randomized controlled trial. J Pak Med Assoc. 2019 Nov;69(11):1601-1604. doi: 10.5455/JPMA.297956.. PMID: 31740863.

- Thoomes E, Thoomes-de Graaf M, Cleland JA, Gallina A, Falla D. Timing of Evidence-Based Nonsurgical Interventions as Part of Multimodal Treatment Guidelines for the Management of Cervical Radiculopathy: A Delphi Study. Phys Ther. 2022 May 5;102(5):pzab312. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzab312. PMID: 35079842.

- Walter SD, Yao X. Effect sizes can be calculated for studies reporting ranges for outcome variables in systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007 Aug;60(8):849-52. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.11.003. Epub 2007 Mar 23. PMID: 17606182.

- Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014 Dec 19;14:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135. PMID: 25524443; PMCID: PMC4383202.

- Young IA, Michener LA, Cleland JA, Aguilera AJ, Snyder AR. Manual therapy, exercise, and traction for patients with cervical radiculopathy: a randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2009 Jul;89(7):632-42. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080283. Epub 2009 May 21. Erratum in: Phys Ther. 2009 Nov;89(11):1254-5. Erratum in: Phys Ther. 2010 May;90(5):825. PMID: 19465371.

- Young IA, Pozzi F, Dunning J, Linkonis R, Michener LA. Immediate and Short-term Effects of Thoracic Spine Manipulation in Patients With Cervical Radiculopathy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2019 May;49(5):299-309. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2019.8150. Epub 2019 Apr 25. PMID: 31021691.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison/ control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comment |

|

Aksoy, 2018 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Single centre, Turkey

Funding and conflicts of interest: none |

Inclusion criteria: Patients with cervical radiculopathy confirmed through MRI, aged 18-65, neck pain on VAS ≥4

Exclusion criteria: (1) previous surgical operation on the c-spine, (2) other systemic, neurological or psychiatric problems; (3) rheumatic and infectious disease; (4) current malignancy; (5) motor deficit in upper extremity; (6) previous treatment with cervical collar; (7) complaints >12 weeks

N total at baseline: 101 Intervention: 67 (34 group 1 and 33 group 2) Control: 33

Important prognostic factors: age: I: 41 (G1), 40 (G2) C: 46

Sex: I: 23% M (G1), 46% M (G2) C: 38% M

VAS score neck pain: I: 8.26 (G1), 8.30 (G2) C: 7.72

NDI score: I: 66 (G1), 64 (G2) C: 55

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Intervention treatment: Group 1 (G1): soft cervical collars (soft sponge) plus control treatment

Group 2 (G2): semi-rigid cervical collars (plastazote foam material) plus control treatment

|

Control treatment: Home exercises comprising cervical isometric, cervical mobilisation, and shoulder protraction and retraction exercises for 6 weeks, twice a day, with 2x 10 repetitions at each session.

Advice to avoid holding the neck in prolonged flexion or extension during daily activities and to use a suitable pillow during sleep.

The use of NSAID was allowed when necessary. |

Length of follow-up: 6 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 4 (G1) and 7 (G2) (10.9%) Reasons: failed to complete, due to discomfort of collar (n = 7), no excuse given (n = 4)

Control: 5 (5%) Reasons (describe): discontinuation with unknown reason

Incomplete outcome data: 14 (13.9%) Same as above

|

Outcome measures and effect size (95%CI):

Pain on VAS (mean difference, 95%CI) Soft collar as add-on to exercise -0.49 [-1.23 to 0.25]

Semi-rigid collar as add-on to exercise 0.26 [-0.59 to 1.11]

NDI (mean difference, 95%CI) Soft collar as add-on to exercise -5.5 [-9.9 to -1.1]

Semi-rigid collar as add-on to exercise 1.0 [-4.0 to 6.0]

Quality of Life (SF-36) (mean difference, 95%CI) Soft collar as add-on to exercise PCS: -3.80 [-6.54 to -1.06] MCS: -0.60 [-3.03 to 1.83]

Semi-rigid collar as add-on to exercise PCS: -1.60 [-4.62 to 1.42] MCS: -2.50 [-5.40 to 0.40] |

|

|

Kuijper, 2009 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: 3 hospitals, the Netherlands

Funding and conflicts of interest: non-commercial organisation for salary of research nurse, no conflicts of interest |

Inclusion criteria: Patients referred by GPs with <1 month symptoms and signs of cervical radiculopathy, aged 18-75 years, with arm pain VAS ≥40mm and radiation of pain distal to elbow. In addition, either provocation of arm pain by neck movements, or sensory changes in ≥1 dermatome, or diminished deep tendon reflexes in the arm, or muscle weakness had to be present.

Exclusion criteria: (1) clinical signs of spinal cord compression, (2) previous treatment with physiotherapy or cervical collar

N total at baseline:205 Intervention: 139 (69 group 1 and 70 group 2) Control: 66

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 47.0 ± 9.1 (G1), 46.7 ± 10.9 (G2) C: 47.7 ± 10.6

Sex: I: 55% M (G1), 49% M (G2) C: 48% M

VAS score neck pain I: 57.4 ± 27.5 (G1), 61.7 ± 27.6 (G2) C: 55.6 ± 31.0

NDI I: 41.0 ± 17.6 (G1), 45.1 ± 17.4 (G2) C: 39.8 ± 18.4

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Intervention treatment: Group 1 (G1): semi-hard collar (one of six sizes with best fit)

Group 2 (G2): Guided physiotherapy sessions consisting of hands off graded activity exercises to strengthen the superficial and deep neck muscles, twice a week for 6 weeks. In addition, physiotherapists educated the patients on home exercises, and practice those every day.

Written and oral reassurance about the usually benign course of the symptoms was given to patients in both G1 and G2. |

Control procedure: Continuation of daily activities without specific treatment other than written and oral reassurance about the usually benign course of the symptoms.

The use of painkillers was allowed when necessary. |

Length of follow-up: 6 months

Loss-to-follow-up: 5 for primary outcome (6 weeks), 13 for entire follow-up (6 months)

Intervention: 6 (G1, 8.7%) and 2 (G2, 2.9%)) Reasons: not provided

Control: 5 (7.6%) Reasons: not provided

Incomplete outcome data: 13 (6.3%) Same as above

|

Outcome measures and effect size (95%CI):

Pain on VAS after 6 weeks (mean difference, 95%CI) Collar compared to no intervention -20.1 [-30.4 to -9.8]

Collar compared to exercise -5.20 [-15.0 to 4.6]

Exercise compared to no intervention -1.49 [-2.56 to -0.42]

NDI after 6 weeks (mean difference, 95%CI) Collar compared to no intervention -4.0 [-10.6 to 2.6]

Collar compared to exercise -1.9 [-7.9 to 4.1]

Exercise compared to no intervention -2.10 [-8.46 to 4.26]

Use of opiates after 6 weeks (relative risk, 95%CI) Collar compared to no intervention 0.75 [0.39 to 1.44]

Collar compared to exercise 0.97 [0.49 to 1.94]

Exercise compared to no intervention 0.78 [0.41 to 1.48]

Working status after 6 weeks (relative risk, 95%CI) Collar compared to no intervention 0.77 [0.48 to 1.25]

Collar compared to exercise 0.66 [0.42 to 1.03]

Exercise compared to no intervention 1.18 [0.78 to 1.77] |

Patients who eventually underwent surgery: 5 in collar group, 3 in physiotherapy group, and 4 in control group. |

|

2. Studies reporting on traction |

|||||||

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Bukhari, 2016 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: single hospital, Pakistan

Funding and conflicts of interest: no funding received, conflict of interest not disclosed. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients with evident radicular symptoms, cervical spine involvement, aged 20-70 years.

Exclusion criteria: History of trauma, neck pain without radiculopathy

N total at baseline: 42 Intervention: 15 (mechanical traction) Control: 21 (manual traction)

Important prognostic factors: age: mean 45.8 years, not reported for both subgroups

Sex: 66% M (not reported for both subgroups)

NRS score: I: 6.26 (± 1.20) C: 6.80 (± 1.20)

NDI score: I: 24.43 (± 8.64) C: 21.92 (± 8.89)

Groups comparable at baseline? Unclear |

Intervention treatment: Mechanical traction, applied on patient in supine position, with 10 second pull and 5 second rest for 10 minutes, with a traction force of 10-15% of body weight.

In addition, segmental mobilisation of C3 to C7 by central posterior-anterior glide, 10 repetitions for 5 seconds was applied, and patients were advised to do a home exercise program with active range of motion, stretching, end isometric strengthening exercises 3 days a week for 6 weeks. |

Control treatment: Manual traction, applied on patient in supine position at 25 degree neck flexion, with 10 second pull and 5 second rest for 10 times.

In addition, segmental mobilisation of C3 to C7 by central posterior-anterior glide, 10 repetitions for 5 seconds was applied, and patients were advised to do a home exercise program with active range of motion, stretching, end isometric strengthening exercises 3 days a week for 6 weeks. |

Length of follow-up: 6 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: 6 patients (unclear which group, no reasons provided)

Incomplete outcome data: 6 (14.3%) Same as above

|

Outcome measures and effect size (95%CI):

Pain on NRS (mean difference, 95%CI) -2.42 [-3.31 to -1.53]

NDI (mean difference, 95%CI) -9.98 [-17.28 to -2.68] |

Methodological weak study with single intervention session. |

|

Ojoawo, 2019 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Academic hospital, Nigeria

Funding and conflicts of interest: none |

Inclusion criteria: Neck pain that radiated distal from the elbow.

Exclusion criteria: Main complaint of headache or facial pain, and having received manual therapy of the cervical region in the past 3 months.

N total at baseline: 75 Intervention: 50 (25 group 1 and 25 group 2) Control: 25

Important prognostic factors: Age (mean ± SD): I: 51.4 ± 6.5 (G1), 55.7 ± 5.4 (G2) C: 59.5 ± 2.6

Sex: I: 56% M (G1), 60% M (G2) C: 44% M

VAS score (mean ± SD): I: 6.87 ± 1.0 (G1, 7.63 ± 2.30 (G2) C: 7.00 ± 0.8

NDI score (mean ± SD):: I: 42.1 ± 16.9 (G1), 58.7 ± 8.9 (G2) C: 55.3 ± 11.3

Groups comparable at baseline? NDI score varies relatively much at baseline, yet in general, yes. |

Intervention treatment: Group 1 (G1): cervical traction “over the door” with a water bat loaded to 10% of patient’s body weight, for 15 minutes. This was administered twice a week for 6 weeks.

Group 2 (G2): transverse oscillatory pressure (TOP) administered by the therapist manually, to the patient lying on his/her belly, on the side of the location of the pain. Administered 3 times for 20 seconds, with 2 min rest in between. TOP was given twice a week for 6 weeks.

In addition, G1 and G2 patients performed active exercises: cervical spine retraction, rotation, extension, and side-bending stretching. Ice packs were applied to the cervical region for 7 minutes, and massage. Both 2 times per week for 6 weeks. |

Control treatment: Patients performed active exercises: cervical spine retraction, rotation, extension, and side-bending stretching. In addition, ice packs were applied to the cervical region for 7 minutes, and massage. Both 2 times per week for 6 weeks. |

Length of follow-up: 6 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: 3 Intervention: 1 (G1) and 0 (G2) (4%) Reasons: discontinued intervention

Control: 2 (8%) Reasons: discontinued intervention

Incomplete outcome data: 14 (13.9%) Same as above

|

Outcome measures and effect size (95%CI):

Pain on VAS (mean difference, 95%CI) Cervical traction compared to control -1.25 [-1.55 to -0.95]

TOP compared to control -1.09 [-1.47 to -0.71]

Cervical traction compared to TOP -0.16 [-0.54 to 0.22]

NDI (mean difference, 95%CI) Cervical traction compared to control -1.50 [-8.76 to 5.76]

TOP compared to control -5.17 [-9.47 to -0.87]

Cervical traction compared to TOP 3.67 [-4.29 to 11.63]

|

Risk of selection bias.

Unclear whether ITT (with unclear imputation methods) or PP was used for analysis. |

|

Fritz, 2014 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Several physical therapy offices, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Non-commercial grant. Conflict of interests not disclosed. |

Inclusion criteria: (1) Chief complaint of neck pain, with symptoms extending distal to acromioclavicular joingt or causal to the superior border of the scapula, (2) age 18-70 years, (3) NDI score ≥10.

Exclusion criteria: (1) history of surgery to the neck or thoracic spine, (2) motor vehicle accident in past 2 weeks, (3) red flags indicative of possible nonmusculoskeletal condition, (4) diagnosis of cervical spinal stenosis on MRI or CT, (5) evidence of cervical myelopathy or CNS involvement

N total at baseline: 86 Intervention: 58 (31 group 1 and 27 group 2) Control: 28

Important prognostic factors: age: I: 48.1 ± 10.0 (G1), 47.6 ± 10.9 (G2) C: 44.9 ± 11.3

Sex: I: 58% M (G1), 44% M (G2) C: 36% M

NRS score: I: 3.8 ± 2.1 (G1), 4.5 ± 2.1 (G2) C: 4.4 ± 2.0

NDI score: I: 31 ± 15 (G1), 33 ± 14 (G2) C: 35 ± 14

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Intervention treatment: Group 1 (G1): Mechanical cervical traction, with angle of pull of 15 degrees. Intermittent traction was performed with 60 seconds pull force and 20 seconds relaxation, for 15 minutes.

Group 2 (G2): Cervical traction using an over-the-door traction device for 15 minutes, used at home daily on days of no physiotherapy sessions.

In addition, patients received 10 individual physiotherapy sessions for 4 weeks (3x/week in first 2 weeks, 2x/week in final 2 weeks), plus an active exercise program, with cervical strengthening and scapula strengthening exercises, to be performed daily on the days between therapy sessions. |

Control treatment: 10 individual physiotherapy sessions for 4 weeks (3x/week in first 2 weeks, 2x/week in final 2 weeks), plus an active exercise program, with cervical strengthening and scapula strengthening exercises, to be performed daily on the days between therapy sessions. |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: 32 Intervention: 10 (G1) and 10 (G2) (34.5%) Reasons: various (unclear flow-diagram)

Control: 12 (44.4%) Reasons: Various (unclear flow diagram)

Incomplete outcome data: 32 (37.2%) Same as above

|

Outcome measures and effect size (95%CI):

Pain on NRS (mean difference, 95%CI) Cervical traction as add-on to exercise -0.92 [-1.80 to -0.04]

NDI (mean difference, 95%CI) Cervical traction as add-on to exercise -1.67 [-4.86 to 1.52]

Adverse events no differences among treatment groups in number, type, duration or severity of adverse reactions |

|

|

Moustafa, 2014 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Single centre, Egypt

Funding and conflicts of interest: none |

Inclusion criteria: (1) Unilateral C5-6 or C6-7 disc herniation confirmed by CT or MRI, (2) dermatomal numbness C6 or C7, (3) current pain or discomfort for > 3 months, (4) radiation of pain in arm with diminished deep tendon reflexes, (5) increase in symptoms with cervical flexion or protrusion and decrease with retraction or side bending and rotation,(6) presence of 4 positive examination findings in provocation tests; all in patients recruited from outpatient physiotherapy department.

Exclusion criteria: (1) presence of medical “red flags” (tumor, fracture, RA, osteoporosis, prolonged steroid use), (2) history of c- or t-spine surgery, (3) signs of upper motor neuron disease, (4) vestibulobasilar insufficiency, (5) amyothropic lateral sclerosis, (6) bilateral symptoms, (7) pregnancy, (8) complete loss of sensation along involved nerve root, (9) severe myelopathy from history taking of motor loss > 3 on MRC scale

N total at baseline: 216 Intervention: 144 (72 group 1 and 72 group 2) Control: 72

Important prognostic factors: age: I: 40.2 ± 4.9 (G1), 41.5 ± 6.1 (G2) C: 41.7 ± 5.5

Sex: I: 43% M (G1), 61% M (G2) C: 56% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Intervention treatment: Group 1 (G1): intermittent ventroflexion traction with increasing traction force, and an on/off cycle of 50/10 for 20 minutes, 3 times per week for 4 weeks.

Group 2 (G2): FCR H-reflex-based traction, same as group 1 yet with different head posture. For 20 minutes, 3 times per week for 4 weeks.

Both group 1 and 2 received in addition the multimodal treatment as described under the control treatment. |

Control treatment: Multimodal program with

Duration of 4 weeks, 3 times per week. |

Length of follow-up: 4 weeks, 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 7 (G1) and 13 (G2) (13.9%) Reasons: loss to follow-up for non-medical causes

Control: 7 (9.7%) Reasons: loss to follow-up for non-medical causes

Incomplete outcome data: 27 (12.5%) Same as above

|

Outcome measures and effect size (95%CI):

Pain on NRS (mean difference, 95%CI) Traction as add-on to manual therapy -0.95 [-1.37 to -0.53]

NDI (mean difference, 95%CI) Traction as add-on to manual therapy -19.00 [-21.05 to -16.95]

|

|

|

Young, 2009 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Multi-centre, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: A grant from commercial company Saunders. Conflicts of interest not disclosed. |

Inclusion criteria: Consecutive patients with unilateral upper-extremity pain, paraesthesia or numbness, aged 18-70 years, with at least 3 out of 4 provocation tests positive.

Exclusion criteria: (1) History of c-spine or t-spine surgery, (2) bilateral upper-extremity symptoms, (3) signs of upper motor neuron disease, (4) medical “red flags”(tumor, fracture, RA, osteoporosis, prolonged steroid use), (5) cervical spine injections (steroidal) in past 2 weeks, (6) current use of steroidal medication for radiculopathy symptoms

N total at baseline: 81 Intervention: 45 Control: 36

Important prognostic factors: Age (mean ± SD): I: 47.8 ± 9.9 C: 46.2 ± 9.4

Sex: I: 31% M C: 33% M

Duration of symptoms (> 3 months): I: 40% C: 58%

NRS score (mean ± SD): I: 6.3 ± 1.9 C: 6.5 ± 1.7

NDI score (mean ± SD): I: 19.8 ± 8.7 C: 17.1 ± 7.4

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Intervention treatment: Sessions including:

In addition, patients received a home exercise program. |

Control treatment: Sessions including:

In addition, patients received a home exercise program. |

Length of follow-up: 4 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 6 (13.3%) Reasons: -

Control: 6 (16.7%) Reasons: -

Incomplete outcome data: 12 (14.8%) Same as above

|

Outcome measures and effect size (95%CI):

Pain on NRS (mean difference, 95%CI) Traction (as add-on to manual therapy and exercise) to control 0.20 [-1.23 to 1.63]

NDI (mean difference, 95%CI) Traction (as add-on to manual therapy and exercise) to control 3.00 [-8.68 to 14.68]

Psychosocial outcomes on FABQ (mean difference, 95%CI) Traction (as add-on to manual therapy and exercise) to control Physical activity subscale: -1.8 [-6.6 to 3.0] Work subscale: 2.9 [95% -8.1 to 13.9] |

|

|

3. Studies reporting on exercise* |

|||||||

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Dedering, 2018 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Academic hospital, Sweden

Funding and conflicts of interest: Non-commercial support and grant, no conflict of interests |

Inclusion criteria: Patients with cervical radiculopathy were recruited from October 2010 to November 2012, with (1) verified cervical disc disease by MRI showing cervical nerve root compression, (2) neck and/or arm pain verified by neck extension test or neurodynamic provocation test.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with (1) a previous cervical fracture, subluxation or surgery; (2) diagnosed psychiatric disorders; (3) spinal infection and malignancy; (4) other diseases or disorders contraindicating participation

N total at baseline: 144 Intervention: 72 Control: 72

Important prognostic factors: age± SD: I: 46.8 ± 9.6 C: 49.7 ± 9.5

Sex: I: 47% M C: 35% M

Neck pain frequency (daily): I: 72% C: 72%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Intervention treatment: Neck-specific training 3 sessions per week, for 3 months. This starts with gentle isometric neck movement, gradually progressing to low-load endurance training, individually tailored based on the patient’s response. A continuous cognitive behavioural approach was adopted during the sessions.

Additionally, patients received information folders with the elements of the intervention: pain physiology, consequences of stress and exercise, relaxation techniques, coping strategies, and ergonomic advice, plus a manual on the standardized neck-specific training program including instructions for progression. |

Control treatment: Prescribed physical activity of 30 minutes, 3 times per week, for 3 month. This starts with one individual counselling session with a cognitive behavioural approach, after which patients receive written recommendations on aerobic and/or muscular physical activity (not neck-specific).

Additionally, patients received information folders with the elements of the intervention: pain physiology, consequences of stress and exercise, relaxation techniques, coping strategies, and ergonomic advice |

Length of follow-up: 24 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 0

Control: 4 (5.6%) Reasons: time restriction

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: 31 (43%) Reasons: discontinued intervention

Control: 36 (50%) Reasons : discontinued intervention

|

Outcome measures and effect size (95%CI):

Pain on VAS (mean difference, 95%CI) Neck-specific training to prescribed activity -0.30 [-1.42 to 0.82]

NDI (mean difference, 95%CI) Neck-specific training to prescribed activity -1.00 [-9.99 to 7.99]

Quality of Life (EQ-5D) (mean difference, 95%CI) Neck-specific training to prescribed activity Index: -0.03 [-0.15 to 0.09] VAS health state: -4 [-13 to 5]

Psychosocial outcomes (FABQ) (mean difference, 95%CI) Neck-specific training to prescribed activity 6 [0 to 12]

|

|

|

Diab, 2012 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Academic centre, Egypt

Funding and conflicts of interest: None |

Inclusion criteria: Patients with (1) a craniovertebral angle <50°, (2) unilateral radiculopathy due to spondylotic changes of C5-C6 or C6-C7, (3) side-to-side amplitude differences of ≥50% in dermatomal sensory-evoked potentials, (4) duration of symptoms >3 months. Inclusion was from September 2009 to July 2010.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Spinal canal stenosis, (2) rheumatoid arthritis, (3) vestibulobasilar insufficiency

N total at baseline: 96 Intervention: 48 Control: 48

Important prognostic factors: Age ± SD: I: 46.3 ± 2.05 C: 45.9 ± 2.1

Sex: I: 56% M C: 48% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Intervention treatment: Posture corrective exercise programme of 10 weeks: 3 sets of 12 repetitions of 2 strengthening exercises, and 3 stretching exercises held for 30 seconds each, four times a week.

Plus 10 weeks, 3 times a week infrared radiation on the neck for 10 minutes, followed by continuous ultrasound application on upper trapezius for 10 minutes (1.5 W/cm2). |

Control treatment: 10 weeks, 3 times a week infrared radiation on the neck for 10 minutes, followed by continuous ultrasound application on upper trapezius for 10 minutes (1.5 W/cm2) |

Length of follow-up: 6 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (95%CI):

Pain on VAS (mean difference, 95%CI) Exercise to control -0.70 [-1.24 to -0.16] |

Selection bias through “conveniently selecting patients from our institution’s outpatient clinic”

Further risk of bias because no loss-of-follow up was reported: there might have been selective drop-out, or a per-protocol analysis performed. |

|

4. Studies reporting on neurodynamic mobilisation |

|||||||

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Ayub, 2019 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Single centre, Pakistan

Funding and conflicts of interest: No conflict of interest, information on funding not disclosed. |

Inclusion criteria: Female patients aged 30-50 years with chronic cervical radiculopathy and neck pain for ≥6 months, and positive provocation tests.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Recent neck trauma, (2) positive vertebrobasilar insufficiency signs, (3) receiving any form of physiotherapy or medical treatment for the last 6 weeks

N total at baseline: 44 Intervention: 22 Control: 22

Important prognostic factors: Age (median ± IQ): I: 41 ± 12 C: 40 ± 11

Sex: not reported

Neck pain (median ± IQ): I: 6 ± 2 C: 6 ± 2

NDI (median ± IQ): I: 10 ± 5 C: 10 ± 10

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Intervention treatment: Moist heat packs for 10 minutes followed by mechanical traction of the cervical spine for 15 minutes. Also 3 sets of slow gentle segmental mobilisation (unilateral posterior anterior glide) with at least 15 to 20 repetitions on the first session, thereafter modified based on patient response.

Then active upper extremity neurodynamic mobilisation, for 6 to 8 repetitions. 3 sessions per week, for 4 weeks. |

Control treatment: Moist heat packs for 10 minutes followed by mechanical traction of the cervical spine for 15 minutes. Also 3 sets of slow gentle segmental mobilisation (unilateral posterior anterior glide) with at least 15 to 20 repetitions on the first session, thereafter modified based on patient response.

Then passive upper extremity neurodynamic mobilisation. 3 sessions per week, for 4 weeks. |

Length of follow-up: 4 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 0

Control: 0

Incomplete outcome data: 0

|

Outcome measures and effect size (95%CI):

Pain on NRS (mean difference, 95%CI) 0.0 [-1.86to 1.86]

NDI (mean difference, 95%CI) No reporting of scale used

Cervical ROM (mean difference, 95%CI) Reported in medians

|

Selection bias (convenience sampling) |

|

Basson, 2020 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Multicentre, South-Africa

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funding received by orthopaedic research investment fund of South African society of physiotherapy and the faculty research committee of the University of Witwatersrand |

Inclusion criteria: (1) Aged > 18 years, (2) nerve related neck and arm pain by physical examination, (3) recent onset of pain (≤12 weeks), and (4) positive upper limb neurodynamic test

Exclusion criteria: (1) Surgery or recent fractures of the cervical spine, (2) serious neurological signs, (3) RA, neurological disease, stroke, cerebral palsy, carcinoma, or any other red flags

N total at baseline: 86 Intervention: 60 Control: 26

Important prognostic factors: Age (mean ± SD): I: 46.5 ± 14.1 C: 48.6 ± 13.6

Sex: not reported

Duration of pain (mean days ± SD): I: 30.2 ± 27.4 C: 23.5 ± 22.9

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Intervention treatment: neurodynamic mobilisation along the tract of the nerve, directly and indirectly, concentrating on areas where the nerve is mechano-sensitive to palpation. From hand or elbow up along the arm, first rib, scalene and into the neck, first in a non-tensioned position, progressing into a more tensioned position as pain and irritability improved.

In addition, patient received usual care similar to patients in the usual care group.

The number of treatments was determined by the treating physiotherapist. |

Control treatment: Usual care with (unilateral) posterior-anterior mobilisation of the cervical and thoracic spine, exercises, and advice to stay active.

The number of treatments was determined by the treating physiotherapist. |

Length of follow-up: 6 weeks, 6 months, 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 7 (11.7%) Reasons: could not be reached (of whom 2 had relocated)

Control: 1 (3.8%) Reasons: could not be reached

Incomplete outcome data: 0 Multiple imputation applied.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (95%CI):

Pain on NRS (mean difference, 95%CI) -0.60 [-1.77 to -0.51]

Function on PSFS (mean difference, 95%CI) (scale 0 to 30, high score is better) 0.05 [0-0.41 to 0.51]

Quality of Life (EQ-5D) (mean difference, 95%CI) 1.1 [4.3 to 6.3]

|

|

|

Ibrahim, 2021 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Single centre, Egypt

Funding and conflicts of interest: No conflicts of interest, funding information not explicitly reported. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients (1) 20-40 years of age, (2) history of pain >3 months, (3) radiating pain in one upper limb, (4) met at least 3 of Wainner criteria

Exclusion criteria: (1) history of high level spinal cord injury, (2) malignancy, (3) any medical red flag (tumor, fracture, RA, osteoporosis, prolonged steroid use), (4) circulatory disturbances of upper extremity, (5) traumatic injuries of upper limb and cervical spine, (6) dizziness

N total at baseline: 40 Intervention: 20 Control: 20

Important prognostic factors: Pain (median ± range): I: 3.75 ± 7 C: 3.75 ± 7

Further no baseline characteristics reported

Groups comparable at baseline? No information |

Intervention treatment: Tensioning neurodynamic mobilisation of brachial plexus, with the arm in neurodynamic testing position, 10 cycles of elbow extension and flexion (each 3 seconds) were administered

Plus tradition physiotherapy (consisting of infrared radiation and manual traction), for 3 sessions per week, over the course of 3 weeks. |

Control treatment: Traditional physiotherapy:

For 3 sessions per week, over the course of 3 weeks. |

Length of follow-up: 3 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 0 Control: 0

Incomplete outcome data: 0 |

Outcome measures and effect size (95%CI):

Pain on VAS (mean difference, 95%CI) 0.0 [-1.17 to 1.17]

|

Selection bias |

|

Kayiran, 2021 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Single centre, Turkey

Funding and conflicts of interest: None |

Inclusion criteria: Patients for whom surgery was not recommended by the neurosurgeon, with (1) cervical disc herniation at C5/C6/C7/C8 confirmed by MRI, (2) aged 20-50 years, (3) cervicobrachial radicular pain for ≥6 weeks (4) pain severity ≥5 on VAS, (5) sensitivity and numbness in radial, median and/or ulnar nerve dynamic tests, (6) not receiving any other treatment or pharmacological agents.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Spinal stenosis, (2) RA, (3) previous c-spine surgery, (4) severe neurological loss, (5) upper extremity vascular problems, (6) severe osteoporosis, (7) diabetes mellitus, (8) pregnant women.

N total at baseline: 71 Intervention: 36 Control: 35

Important prognostic factors: Age (mean ± SD): I: 47.2 ± 12.5 C: 43.3 ± 12.0

Sex: not reported

Neck pain (mean ± SD): I: 4.83 ± 1.12 C: 4.83 ± 1.23

NDI (mean ± SD) I: 18.93 ± 6.43 C: 18.93 ± 5.10

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Intervention treatment: neurodynamic mobilisation on radial, median and ulnar nerves, 10 times 10 seconds for each nerve. For 10 sessions over 3 weeks.

Plus conservative physiotherapy (hotpacks, TENS, ultrasound and exercises) for 3 weeks, 5 sessions per week.

|

Control treatment: Conservative physiotherapy:

For 3 weeks, 5 sessions per week |

Length of follow-up: 3 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 6 (16.7%) Reasons: no belief in treatment (n = 3), no adaptation to treatment time (n = 2), relocation (n = 1)

Control: 5 (14.3%) Reasons: no belief in treatment (n = 2), no adaptation to treatment time (n = 2), quit treatment because of poor health (n = 1)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: 11 (15.5%) Reasons: as mentioned above.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (95%CI):

Pain on VAS (mean difference, 95%CI) -1.04 [-1.57 to -0.51]

NDI (mean difference, 95%CI) No reporting of scale used

Cervical ROM (mean difference, 95%CI) Flexion: 3.9 [1.1 to 6.7] Extension: 6.2 [3.0 to 9.5] Side bending right: 4.4 [1.5 to 7.3] Side bending left: 5.6 [2.6 to 8.6] Rotation right: -0.7 [-5.3 to 3.8] Rotation left: -0.3 [-5.4 to 4.8] |

|

|

Kim, 2017 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Single centre, Korea

Funding and conflicts of interest: No conflict of interest. Funding information not disclosed. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients with (1) a diagnosis of cervical radiculopathy ≥3 months, (2) aged 26 to 60 years, (3) unilateral pain, (4) ≥3 out of 4 positive provocation tests

Exclusion criteria: None reported

N total at baseline: 30 Intervention: 15 Control: 15

Important prognostic factors: Age (mean ± SD): I: 29.3 ± 3.3 C: 29.3 ± 3.1

Sex: I: 40% M C: 33% M

NRS (mean ± SD): I: 7.0 ± 0.85 C: 7.1 ± 0.80

NDI (mean ± SD): I: 21.7 ± 4.1 C: 22.1 ± 3.0

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Intervention treatment: Similar treatment as control treatment group, yet during the manual cervical traction, another physiotherapist applied neurodynamic mobilisation using a slider technique for the median nerve in a smooth and rhythmic manner (with elbow extension/flexion and wrist flexion/extension), for 6 times 1 minute with 30 seconds rest inbetween. For 8 weeks, 3 times per week. |

Control treatment: Conservative physiotherapy (total 35 minutes):

Plus manual cervical traction for 6 repetitions of 1 minute pull with 30 seconds rest (total 10 minutes) For 8 weeks, 3 times per week. |

Length of follow-up: 4 and 8 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 0 Control: 0

Incomplete outcome data: 0

|

Outcome measures and effect size (95%CI):

Pain on NRS (mean difference, 95%CI) -1.0 [-1.69 to -0.31]

NDI (mean difference, 95%CI) -6.92 [-11.41 to -2.43]

Cervical ROM (mean difference, 95%CI) Flexion: 3.3 [0.3 to 6.4] Extension: 5.1 [2.2 to 8.0] Side bending right: 2.6 [0.7 to 4.5] Side bending left: 2.4 [0.9 to 3.9] Rotation right: 2.4 [0.3 to 4.5] Rotation left: 3.6 [1.8 to 5.4]

|

|

|

Rodriguez-sans, 2017 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Single centre, Venezuela

Funding and conflicts of interest: none |

Inclusion criteria: Consecutive patients seeking treatment for cervicobrachial pain, who (1) had clinical signs of cervicobrachial pain (arm pain, paresthesia, numbness in upper limb), confirmed through MRI, (2) aged 18 to 45, (3) unilateral symptoms for at least 3 months, (4) 3 positive provocation tests

Exclusion criteria: (1) Use of any type of treatment to relieve pain (therapy, procedures or drugs), (2) using anticonvulsant, antidepressant, or psychotropic medication, (3) vertebral instability, osteoporosis or spine infection, (4) neurologic diseases, (5) cervical stenosis myelopathy, (6) kinesiophobia, (7) pregnancy, (8) endocrine disorders and menopause, (9) history of spine surgery, (10) severe mental illness, (11) intoxication, (12) intellectual disability, (13) severe sleep deprivation, (14) Alzheimer’s disease

N total at baseline: 58 Intervention: 29 Control: 29

Important prognostic factors: Age(mean ± SD): I: 33.3 ± 5.0 C: 32.5 ± 4.6

Sex: I: 56% M C: 44% M

NRS (mean ± SD): I: 6.08 ± 0.99 C:6.44 ± 0.93

Groups comparable at baseline? As far as information is provided, yes |

Intervention treatment: Cervical lateral glide (CLG) neural mobilisation administered by a physiotherapist, to the contralateral side of pain in a slow oscillating manner. CLG was applied continuously for two minutes in 5 consecutive applications, with one minute rest in between. For 5 days per week, for 6 weeks. |

Control treatment: Waiting list for 6 weeks (did not receive an type of pain-modulating treatment) |

Length of follow-up: 6 weeks (30 treatment days)

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 4 (13.8%) Reasons: did not complete treatment as allocated

Control: 2 (6.9%) Reasons: did not complete treatment as allocated

Incomplete outcome data: 6 (10.3%) Reasons: see above

|

Outcome measures and effect size (95%CI):

Pain on NRS (mean difference, 95%CI) -2.96 [-3.54 to -2.38]

Function (Quick DASH) -21.5 [-27.4 to -15.73]

Function (ipsilateral cervical rotation) (mean difference, 95%CI) 8.0 [4.9 to 11.1]

|

|

|

Savva, 2016 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Single centre, Cyprus

Funding and conflicts of interest: None. |

Inclusion criteria: Consecutive patients with unilateral cervical radiculopathy diagnosed by MRI or CT referred to the physiotherapy department, with (1) unilateral sharp pain, muscle weakness and numbness in upper arm, (2) ≥3 out of 4 positive provocation tests.

Exclusion criteria: (1) current cervical myelopathy or signs of upper motor neuron disease, (2) bilateral complaints, (3) other musculoskeletal conditions in the affected limb, (4) use of analgesia or anti-inflammatory medication in the prior 2 weeks.

N total at baseline: 42 Intervention: 21 Control: 21

Important prognostic factors: Age (mean ± SD): I: 45.2 ± 13.5 C: 49.2 ± 8.5

Sex: I: 38% M C: 62% M

NRS (mean ± SD): I: 5.62 ± 2.52 C: 5.19 ± 2.11

NDI (mean ± SD): I:33.3 ± 17.6 C: 30.2 ± 16.4

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Intervention treatment: Intermittent (pain-free) cervical traction with 1 minute pull and 1 minute rest for 6 sets. During the cervical traction, slider neurodynamic mobilisation using a median nerve bias were performed in slow and oscillatory fashion, with the patients’ elbow, wrist and finger repositioning. 3 treatment sessions per week, for 4 weeks.

In addition, patients received advice to avoid prescription or over-the-counter analgesia or anti-inflammatory medication.

|

Control treatment: Did not receive any type of treatment, with advice to avoid prescription or over-the-counter analgesia or anti-inflammatory medication, for the duration of 4 weeks. |

Length of follow-up: 4 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 0 Control: 0

Incomplete outcome data: 0

|

Outcome measures and effect size (95%CI):

Pain on NRS (mean difference, 95%CI) -3.36 [-4.56 to -1.96]

NDI (mean difference, 95%CI) -15.33 [-23.26 to -7.40]

Function on PSFS (mean difference, 95%CI) (scale 0 to 10) 1.62 [0.91 to 2.32]

Cervical ROM (mean difference, 95%CI) Flexion: 5.7 [0.5 to 11.0] Extension: 8.8[-0.5 to 18.1] Side bending ipsilateral: 6.4 [1.6 to 11.1] Side bending contralateral: 6.0 [1.5 to10.4] Rotation ipsilateral: 7.9 [1.5 to 14.3] Rotation contralateral: 10.6 [3.6 to 17.6]

|

|

|

Savva, 2021 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Single centre, Cyprus

Funding and conflicts of interest: None. |

Inclusion criteria: Consecutive patients with unilateral cervical radiculopathy referred to the physiotherapy department, (1) aged 20 to 75 years, with (2) unilateral upper limb pain, sensory and/or motor symptoms, (3) ≥3 out of 4 positive provocation tests.

Exclusion criteria: (1) bilateral complaints, (2) other musculoskeletal conditions in the affected limb, (3) evidence of central nervous system involvement, (4) history of medical red flags (tumor, metabolic disease, RA, osteoporosis), (5) use of analgesia or anti-inflammatory medication in the prior 2 weeks.

N total at baseline: 66 Intervention: 22 (G1), 22 (G2) Control: 22

Important prognostic factors: Age (mean ± SD): I: 47.7 ± 10.8 (G1), 48.1 ± 11.9 (G2) C: 48.5 ± 12.3

Sex: I: 50% M (G1), 59% M (G2) C: 36% M

Duration of symptoms >3 months: I: 54% (G1), 41% (G2) C: 55%

NRS (mean ± SD): I: 6.1 ± 2.2 (G1), 6.1 ± 2.6 (G2) C: 5.4 ± 1.8

NDI (mean ± SD): I: 33.3 ± 17.6 (G1), 34.5 ± 14.2 (G2) C: 29.0 ± 15.9

Groups comparable at baseline? Gender seems to differ sligthly at baseline between intervention and control groups. |

Intervention treatment: Group 1 (G1): Cervical traction with neurodynamic mobilisation Intermittent (pain-free) cervical traction with 1 minute pull and 30 seconds rest for 10 sets. During the cervical traction, slider neurodynamic mobilisation of the median nerve was performed in slow and oscillatory fashion, with repeated passive flexion and extension of the patients’ elbow, wrist and fingers. 3 treatment sessions per week, for 4 weeks.

Group 2 (G2): cervical traction with sham neurodynamic mobilisation Intermittent (pain-free) cervical traction with 1 minute pull and 30 seconds rest for 10 sets. During the cervical traction, sham neurodynamic mobilisation with sustained position of elbow and wrist, and repeated passive flexion and extension of the patients’ fingers within the ROM. 3 treatment sessions per week, for 4 weeks.

|

Control treatment: Waiting list without any type of treatment for 4 weeks. |

Length of follow-up: 4 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 0 Control: 0

Incomplete outcome data: 0

|

Outcome measures and effect size (95%CI):

Pain on NRS (mean difference, 95%CI) NM + cervical traction to waiting list -3.30 [-4.51 to -2.09]

NM as add on to cervical traction to sham NM -2.4 [-3.75 to -1.05]

NDI (mean difference, 95%CI) -32.60 [-47.56 to -17.64]

Function on PSFS (mean difference, 95%) 1.39 [0.72 to 2.05]

Cervical ROM Flexion: 5.9 [0.8 to 11.0] Extension: 5.8[-3.1 to 14.7] Side bending ipsilateral: 6.2 [1.4 to 11.1] Side bending contralateral: 6.3 [2.2 to10.4] Rotation ipsilateral: 8.7 [1.7 to 15.7] Rotation contralateral: 13.5 [6.7 to 20.3]

|

|

|

5. Studies reporting on manual therapy** |

|||||||

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Hassan, 2020 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: single centre, Pakistan

Funding and conflicts of interest: No conflicts of interest, funding information not disclosed. |

Inclusion criteria: (1) Patients aged 30-70 with positive findings of cervical radiculopathy on X-ray, (2) decreased range of motion, (3) positive neurodynamic provocation tests, (4) neck pain <8 on NRS, and (5) numbness or paresthesia or pain in arm or hand

Exclusion criteria: (1) Cervical myelopathy, (2) vertebrobasilar insufficiency, (3) recent history of trauma, (4) thoracic outlet syndrome, (5) carpal tunnel syndrome, (6) use of pain medications for cervical radiculopahty

N total at baseline: 46 Intervention: 23 Control: 23

Important prognostic factors: age± SD: Overall: 43.1 ± 8.2 years

Sex: I: 65% M C: 70% M

NRS score (median ± IQ ): I: 8.0 ± 0.75 C: 8.0 ± 1.75

NDI score (median ± IQ): I: 39.5 ± 4 C: 41.0 ± 10

Groups comparable at baseline? Insufficient information, yet seems so. |

Intervention treatment: Oscillatory mobilisation (Maitland), 3 sets of 15 repetitions of unilateral postero-anterior glide on the involved segment. For 7 treatment sessions over 2 weeks.

Plus a home exercise plan (stretching and strengthening exercises), heat therapy and TENS for 10 minutes |

Control treatment: Sustained stretch mobilisation (Kaltenborn): 3 sets of cervical traction and cervical segment flexion, coupled with side bending and rotation. For 7 treatment sessions over 2 weeks.

Plus a home exercise plan (stretching and strengthening exercises), heat therapy and TENS for 10 minutes |

Length of follow-up: 2 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: 6 Intervention: 3 (13%) Reasons: loss to follow up (n=3)

Control: 3 (13%) Reasons: Loss to follow-up (n = 2), discontinued intervention (n = 1)

Incomplete outcome data: 6 (13%) See above.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (95%CI):

Pain on NRS (mean difference, 95%CI) -1.0 [-2.0 to 0.0]

NDI (mean difference, 95%CI) Not reported which scale used

Cervical range of motion (ROM, medians) Flexion: 47 to 24 Extension: 59 to 45 Side bending right: 45 to 45 Side bending left: 45 to 45 Right rotation: 80 to 50 Left rotation: 80 to 53.5

|

Selection bias

Per protocol analysis |

|

Shafique, 2019 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Single centre, Pakistan

Funding and conflicts of interest: none |

Inclusion criteria: (1) Cervical radiculopathy patients aged 20 to 60 years, (2) ≥3 out of 4 positive provocation tests; (3) pain and paraesthesia in the unilateral upper extremity and limited cervical ROM

Exclusion criteria: (1) bilateral upper extremity symptoms, (2) previous C-spine or T-spine injury, (3) recent gracture or surgery in and around the shoulder, (4) any systemic disease, (5) unsTable spine

N total at baseline: 38 Intervention: 19 Control: 19

Important prognostic factors: age± SD: I: 42.3 ± 10.4 C: 41.0 ± 9.3

Sex: I: 33% M C: 44% M