Epidurale corticosteroïde-injecties

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de rol van epidurale corticosteroïde-injecties (ECSI) bij de behandeling van patiënten met een cervicaal radiculair syndroom?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg het toedienen van cervicale epidurale steroïde-injecties (ECSI) bij patiënten met een subacuut CRS die ernstige pijnklachten ervaren ondanks adequate pijnmedicatie/fysiotherapie, met in achtneming van het risico op complicaties.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Het doel van de uitgangsvraag was om de waarde van cervicale epidurale corticosteroïde-injecties (ECSI) met of zonder lokaal anestheticum te evalueren in de behandeling van een cervicaal radiculair syndroom (CRS). Corticosteroïden zijn niet geregistreerd voor epidurale toediening, wat betekent dat deze behandeling een off-label gebruik is. In totaal zijn vijf RCT’s gevonden die ECSI vergeleken met een andere conservatieve behandeling.

De bewijskracht voor de kritieke uitkomstmaten (pijn, patiënttevredenheid en complicaties) was zeer laag. Deze zeer lage bewijskracht wordt veroorzaakt door verschillende methodologische beperkingen, variërende behandelingen en relatief kleine studiepopulaties waarvan de duur van de klachten varieert (van subacuut tot chronisch) en/of niet altijd duidelijk is. Dit betekent dat andere studies waarschijnlijk leiden tot nieuwe inzichten. Er kunnen op basis van alleen de literatuur geen sterke aanbevelingen geformuleerd worden.

Toekomstige studies zouden zich vooral moeten richten op patiënten met een ‘subacuut’ CRS (<3 maanden) waarbij ECSI wordt vergeleken met ‘usual care’. Terwijl ECSI tot doel heeft de ontstekingsreactie rondom de zenuw te verminderen, wat vooral in de (sub)acute fase voorkomt, worden in de meeste studies ook patiënten geïncludeerd met chronische klachten (>3 maanden). Tevens verschilt de controlegroep sterk in de vijf RCT’s (fysiotherapie, lokaal anestheticum, intra-articulaire facet-injectie, intramusculaire injectie). Bij formuleren van aanbevelingen baseerde de werkgroep zich daarom ook op de onderstaande overwegingen.

Complicaties

Complicaties van ECSI komen voor in RCT’s, maar meestal zijn de studie populaties zeer klein (Hong, 2021; Schneider, 2016). Zeldzame complicaties worden daarom hoofdzakelijk beschreven in case reports (van Boxem, 2019; Peene, 2023). De minder ernstige complicaties (zoals nekpijn, gevoeligheid op de injectieplaats, complicaties door het gebruik van glucocorticoïden, subjectieve zwakte van de armen en slapeloosheid) lijken veelal van kortdurende aard. Het risico op een epiduraal hematoom na ECSI lijkt voornamelijk verhoogd bij patiënten die al behandeld worden met bloedverdunners. Voor het beleid omtrent antistolling verwijst de werkgroep naar de richtlijn Neuraxisblokkade en antistolling (NVA, 2014). Voor meer ECSI specifieke informatie verwijst de werkgroep naar de internationale richtlijn (Narouze, 2018). Het bijwerkingenprofiel voor interlaminaire en transforaminale toediening lijkt verschillend van aard (Peene, 2023), en wordt hieronder nader beschreven.

Interlaminair

Bij interlaminaire toediening worden zeldzame ernstige complicaties gerapporteerd, zoals epiduraal hematomen, infecties, accidentele subdurale injectie, en direct naaldtrauma (Peene, 2023). Subdurale injectie kan leiden tot post-punctionele hoofdpijn en in uitzonderlijke gevallen tot hypoventilatie en hypotensie (Vallejo, 2022). Post-punctionele hoofdpijn is veelal te verhelpen met conservatieve behandeling en/of een epidurale bloedpatch. Complicaties ten gevolge van direct naaldtrauma kunnen vermeden worden door een correcte techniek met beeldvorming (van Boxem, 2019).

Transforaminaal

Bij transforaminale toediening komen verschillende ernstige complicaties voor. De meest voorkomende zijn letsels aan het ruggenmerg door anterieure spinale arterie injectie en mogelijke schade aan het centrale zenuwstelsel door embolisatie van de aanvoerende arteriën (Van Boxem, 2019; Peene, 2023). Dergelijke complicaties lijken niet altijd technisch te voorkomen.

Gezien het lager risico op ernstige complicaties bij de interlaminaire benadering, adviseert de werkgroep hier de voorkeur aan te geven indien, ondanks het ontbreken van bewijs van effectiviteit, toch wordt gekozen voor het geven van een cervicale epidurale injectie.

Dexamethason

Mocht toch de voorkeur liggen bij een transforaminale ESCI, dan adviseert de werkgroep dexamethason zonder bewaarmiddelen te gebruiken, een non-particulate corticosteroïde. Dit wordt onderbouwd in een consensuspaper van US stakeholders (Benzon, 2015; Rathmell, 2015). In Nederland is dexamethason zonder bewaarmiddelen als farmaceutische specialiteit echter niet beschikbaar. Daarom is in 2019 het Benelux “Safe Use Initiative” geüpdatet op basis van de beschikbare producten in de Benelux (Van Boxem, 2019). Hierin wordt aanbevolen om dexametason zonder bewaarmiddelen te gebruiken op basis van generieke producten (ook wel “compound” genoemd).

Toediening

In geval van interlaminaire toediening wordt een ECSI bij voorkeur op niveau C7-T1 geplaatst. Meer naar craniaal neemt de diameter van de epidurale ruimte af. Het verdient aanbeveling om radiologische evaluatie vooraf middels MRI (tweede voorkeur: CT) uit te voeren om de beschikbare epidurale ruimte voorafgaand te evalueren.

Voor de interlaminaire injectie zijn geen vasculaire complicaties gemeld, daarom kan een partikel houdend steroïde (of dexamethason 10 mg) toegediend worden. Indien nodig kan 0.9% NaCl of 1-2% lidocaïne gebruikt worden als verdunning. Beperk hierbij het totale volume tot maximum 4 ml.

Indien na de eerste injectie onvoldoende verbetering optreedt, kan een tweede of derde injectie nuttig zijn na enkele weken (Joswig, 2018). Bij het bepalen van een minimaal interval tussen twee injecties, baseert de werkgroep zich op de huidige praktijk, waarin een tweede injectie kan worden toegediend wanneer nodig (i.e. na enkele weken of maanden).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

De meeste patiënten die voor ECSI in aanmerking komen hebben al een conservatieve behandeling ondergaan met onvoldoende resultaat. Aangezien de epidurale toediening van corticosteroïden een off-label toepassing is, moeten de mogelijke voor- en nadelen van ECSI goed met de patiënt worden besproken. De werkgroep geeft de voorkeur aan een beslissing in samenspraak met de patiënt.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Een Amerikaanse studie vergeleek de kosten-effectiviteit van patiënten die ECSI kregen met patiënten die conservatieve behandeling (fysiotherapie en analgetica) kregen. ECSI was kosten-effectiever dan de conservatieve behandeling (Alvin, 2019). Patiënten met ECSI hadden ongeveer 50% minder ziekteverzuim in vergelijking met de controlegroep. Ook in een andere internationale kosteneffectiviteitsstudie werd ECSI kosteneffectief bevonden (Manchikanti, 2019).

De verschillen tussen het Amerikaanse en Nederlandse zorgsysteem moeten bij de interpretatie van deze resultaten goed in overweging genomen worden. De werkgroep verwacht echter dat de richting van de resultaten ook zullen gelden voor het Nederlandse zorgsysteem.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De werkgroep concludeert op basis van verschillende studies dat beeldvorming essentieel is om ECSI goed en veilig uit te voeren (Hochberg, 2021; Park, 2016; Ulusoy, 2018; van Zundert, 2010; Peene, 2023). Bij de keuze van de beeldvormingstechniek dient rekening gehouden te worden met de stralingsbelasting, waarbij deze voor de CT scan het hoogst is. De werkgroep geeft daarom de voorkeur aan toediening van ECSI onder controle van beeldvorming met fluoroscopie/doorlichting als standaard (“Real time” bij de transforaminale benadering). In het licht van het bovenstaande vergt het uitvoeren van de ECSI een grondige kennis van de (vasculaire) anatomie en ervaring met de interpretatie van de medische beeldvorming. Een goede training en opleiding voor deze techniek is daarom essentieel.

Patiënten worden doorgaans verwezen door de neuroloog die de patiënt met een CRS heeft gezien op verzoek van de huisarts. ECSI zijn relatief laagdrempelig toegankelijk voor iedereen die zich naar een pijncentrum kan begeven. De interventie duurt gemiddeld rond 30 minuten. Daarna wordt de patiënt in observatie gehouden gedurende enkele uren. Veelal wordt een speciale dag gepland voor de ECSI toedieningen.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De bewijskracht voor ECSI is beperkt, aangezien het bewijs gebaseerd is op relatief kleine RCT’s van wisselende methodologische kwaliteit. De werkgroep raadt in het licht van het risico op complicaties voorzichtigheid aan bij het gebruik van ECSI. Alhoewel de werkgroep transforaminale ECSI niet aanbeveelt, zijn er weinig argumenten tegen het uitvoeren van transforaminale toediening mits dexamethason zonder bewaarstoffen wordt gebruikt. De werkgroep stelt op basis van het beschikbare bewijs en expert opinion een zwakke aanbeveling op, waarbij ECSI een te overwegen optie is.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Veelal heeft het voorkeur om patiënten met een cervicaal radiculair syndroom (CRS) primair te behandelen met conservatieve (niet-operatieve) therapieën. Als onderdeel van een conservatief traject kunnen zorgverleners naast bewegingsadviezen, fysiotherapie en pijnmedicatie ook een interventionele pijnbehandeling geven. Een interventionele pijnbehandeling kan bestaan uit epidurale corticosteroïde-injecties. Door pijnverlichting probeert men een operatieve interventie te voorkomen, aangezien het natuurlijk beloop van een CRS meestal gunstig is.

De achtergrond voor epidurale corticosteroïde-injecties is gebaseerd op de veronderstelling dat CRS gepaard gaat met een ontstekingsreactie, welke bijdraagt aan de radiculaire pijnklachten. De aanname is dat de injecties pijnstillend en ontstekingsremmend werken. Injecties kunnen transforaminaal of interlaminair toegediend worden.

Epidurale corticosteroïde-injecties worden in de praktijk veelvuldig toegepast. Momenteel is echter de (toegevoegde) waarde van epidurale corticosteroïde-injecties, als behandeling of als add-on therapie, voor patiënten met CRS onduidelijk. Vanwege mogelijke complicaties, dienen zowel effectiviteit als veiligheid in kaart gebracht te worden, alvorens aanbevelingen kunnen worden geformuleerd.

Deze module gaat over patiënten met cervicaal radiculair syndroom. Raadpleeg bij nekpijn zonder radiculaire pijn de betreffende richtlijn. Diagnostische facetten van epidurale corticosteroïde-injecties worden buiten beschouwing gelaten.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Pain (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of (add on) epidural corticosteroid injections with or without local anaesthetic injection on pain (any term) compared with usual care in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Sources: Anderberg, 2007; Cohen, 2014; Manchikanti, 2012; Stav, 1993 |

2. Patient satisfaction (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of (add on) epidural corticosteroid injections with or without local anaesthetic injection on patient satisfaction compared with usual care in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Sources: Cohen, 2014 |

3. Complications (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of (add on) epidural corticosteroid injections with or without local anaesthetic injection on complications compared with usual care in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Sources: Anderberg, 2007; Cohen, 2014; Manchikanti, 2012; Stav, 1993 |

4. Use of medication (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of (add on) epidural corticosteroid injections with or without local anaesthetic injection on medication use compared with usual care in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Sources: Cohen, 2014; Manchikanti, 2012; Stav, 1993 |

5. Functioning (important)

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of epidural steroid injections on functioning, compared with usual care in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Sources: - |

6. Disability

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of (add on) epidural corticosteroid injections with or without local anaesthetic injection on disability compared with usual care in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Sources: Bureau, 2014; Cohen, 2014; Manchikanti, 2012 |

7. Quality of life (important)

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of epidural steroid injections on quality of life, compared with usual care in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Sources: - |

8. Surgery sparing effect (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of (add on) epidural corticosteroid injections with or without local anaesthetic injection on cervical surgery compared with usual care in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Sources: Cohen, 2014 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Anderberg (2007) performed an RCT to determine the short-term effect of a single dose corticosteroid injection on cervical radiculopathy with radicular pain. Participants were 27 to 65 years of age, and underwent prior MRI investigation of the cervical spine, evaluated by three medical specialists, and a diagnostic selective nerve root block (SNRB). All patients responding with a significant pain reduction to SNRB’s, were randomized into treatment with transforaminal epidural injections with mepivacaïne (carbocain) and methylprednisolone acetate (n= 20), or with transforaminal epidural injections with mepivacaïne (carbocain) with saline (n= 20). Patients whose MRI documented degenerative pathology at two levels received SNRB at two levels. If the response to SNRB was positive, they received the at random selected treatment at two levels. Otherwise, the patient received the random treatment at one level. A total of 40 (100%) participants completed the three-week follow-up.

Bureau (2014) performed an RCT to test the effectiveness of intra-articular facet steroid injections (IFSI) compared with transforaminal corticosteroid injections (TFSI) in participants with cervical radiculopathy. Participants were adults with a history of at least one month radiculopathy, refractory to medical treatment, with motor weakness due to degenerative spondylosis and/or disk herniation, and a pain score of at least 6 or higher on a verbal analogue scale (VAS). A total of 56 (100%) participants completed the 4-week follow-up.

Cohen (2014) performed an RCT to determine the effectiveness of cervical interlaminar epidural steroid injections compared to conservative care (pharmacotherapy and physical therapy) or combination-treatment (epidural steroid injection with physical therapy). Participants had a minimal age of 18 years and had a history of cervical radicular pain of more than 4/10 on a numerical rating scale. Participants had complaints longer than one month, but not over 4 years.

A total of 58 (98%) participants in the conservative treatment-group, 54 (98%) participants in the interlaminar epidural steroid-group and 51 (93%) participants in the combined-group completed the one-month follow-up. For 3- and 6-month follow up data, the last observation carried forward method was used.

Manchikanti (2012) performed an RCT to determine the effectiveness of cervical interlaminar epidural injections of local anaesthetics with or without steroids for the treatment of patients with herniation and radiculitis. Participants had a minimal age of 18 years, had a history of chronic, function-limiting neck and upper extremity pain (at least for six months), and failed to respond to conservative treatment. Participants were blinded to group assignment, and a total of 56 (93%) participants in the intervention group, and 59 (98%) in the group receiving local anaesthetic completed 12-month follow-up. All participants were included in analysis.

Stav (1993) performed an RCT to determine the effectiveness of cervical epidural steroid injections for treatment of cervical pain syndrome. It was not reported whether an interlaminar or transforaminal approach was used. Participants were 20 to 75 years of age and had chronic refractory cervicobrachialgia. Participants were not blinded to group assignment, and a total of 25 (100%) participants in the intervention group, and 17 (68%) in the control group, receiving an intramuscular injection of lidocaine and steroid, completed 1 year follow-up. In the control group, 8 participants were excluded from all analyses due to a process of litigation of insurance claims.

Table 1. Description of included studies

|

Study |

Intervention |

Comparator |

Follow-up |

Outcomes |

||

|

|

Characteristics |

Intervention type/ dose |

Characteristics |

Type of control group |

|

|

|

Anderberg, 2007 |

Mean age (SD): 49.5 (8.7) Female (%): 11 (55) Duration of pain, months (SD): 34.5 (26.9) Level of injection: C5-C6 (n= 3), C6 (n= 7), C6-C7 (n=3), C7 (n=6), C7-C8 (n= 1) Diagnosis: foraminal stenosis (n= 15), hard disc (n=4), soft disc (n= 1)

|

Transforaminal steroids/local anaesthetics (n= 20)

0.5 ml Carbocain (Mepivacaine) and 1 ml Depo Medrol (40 mg methylprednisolone acetate) per injection (either on one or two levels (roots) of the cervical spine) |

Mean age (SD): 52.5 (7.0) Female (%): 9/20 (45) Duration of pain, months (SD): 27.0 (25.8) Level of injection: C4 (n= 1) C5 (n= 3), C6 (n= 8), C6-C7 (n=4), C7 (n=3), C8 (n= 1) Diagnosis: foraminal stenosis (n= 11), hard disc (n= 8), soft disc (n= 1) |

Transforaminal saline/local anaesthetic (n= 20)

0.5 ml Carbocain (Mepivacaine) and 1 ml saline per injection (either on one or two levels (roots) of the cervical spine) |

1, 2, and 3 weeks after injections. |

Pain (significant subjective reduction of radicular pain/neurological deficits (yes/no))

|

|

Bureau, 2014 |

Mean age (SD): 52 (11) Female (%): 13 (46) Duration of pain, months (SD): 17 (21) Level of injection: C4-C5 (n= 3), C5-C6 (n= 15), C6-C7 (n= 10) Imaging findings: disc herniation (n= 7), spondylosis (n= 20), spondylosis/disc herniation (n= 1) |

TFSI (n= 28)

1 ml of dexamethasone sodium phosphate, 10 mg/ml, with 0.5-1.0 mL of contrast material, the needle is positioned in the posterolateral aspect of the foramen. |

Mean age (SD): 44 (8.3) Female (%): 20 (71) Duration of pain, months (SD): 14 (20) Level of injection: C3-C4 (n= 1), C4-C5 (n= 1), C5-C6 (n= 16), C6-C7 (n=10) Imaging findings: disc herniation (n= 12), spondylosis (n= 14), spondylosis/disc herniation (n= 2) |

IFSI (n= 28)

1 ml of dexamethasone sodium phosphate, 10 mg/ml, with 0.5-1.0 mL of contrast material, the needle is positioned in the facet joint. |

4 weeks after injections. |

Pain (VAS), medication use (MSQ), disability (NDI) |

|

Cohen, 2014 |

Median age (IQR): 44.0 (41.0-54.0) Female (%): 28 (50.9) Duration of pain, years (median, IQR): 0.8 (0.3-2.0)

|

Epidural steroid injection (n= 59)

3 ml solution, 60 mg depo-methylprednisolone and saline. At least one injection with fluoroscopic guidance, ipsilateral to midline (when symptoms were unilateral) or midline (bilateral symptoms). |

Median age (IQR): 45.0 (41.0-54.0) Female (%): 33 (55.9) Duration of pain, years (median, IQR): 1.0 (0.5-2.0)

|

Conservative treatment (n= 55) Pharmacotherapy (gabapentin/nortriptyline) and physical therapy as indicated.

|

1, 3, and 6 months after injections |

Pain (NRS arm, NRS neck), successful treatment outcome (yes/no), medication use, positive global perceived effect (yes/no), disability (NDI), surgery sparing effect |

|

Median age (IQR): 49.0 (41.0-59.0) Female (%): 25 (45.5) Duration of pain, years (median, IQR): 0.7 (0.3-2.5)

|

Combined treatment (n= 55)

Conservative treatment (pharmacotherapy) with additional epidural steroid injection. |

|||||

|

Manchikanti, 2012 |

Mean age (SD): 45.6 (10.4) Female (%): 35 (58) Duration of pain, months (SD): 91.9 (94.5) Level of disc herniation: C3-C4 (n= 8), C4-C5 (n= 12), C5-C6 (n= 36), C6-C7 (n= 28), C7-T1 (n= 7) |

Betamethasone (n= 60)

Cervical interlaminar epidural injections, 4 ml with 0.5% lidocaine, mixed with 1 ml or 6 mg non-particulate betamethasone |

Mean age (SD): 46.2 (10.3) Female (%): 32 (53) Duration of pain, months (SD): 118.3 (98.6) Level of disc herniation: C3-C4 (n= 8), C4-C5 (n= 18), C5-C6 (n= 30), C6-C7 (n= 24), C7-T1 (n= 6) |

Anaesthetic (n= 60)

Cervical interlaminar injections 5 ml with lidocaine 0.5% |

3, 6, and 12 after injections |

Pain (NRS), medication use (opioid intake), functioning (employment characteristics), disability (NDI) |

|

Stav, 1993 |

Mean age (SD): 52.3 (12.2) Female (%): 14 (56) Duration of pain, months (SD): 16.2 (10.5)

|

Cervical epidural steroid/lidocaine injection (n= 25) |

Mean age (SD): 49.3 (12.4) Female (%): 9 (53) Duration of pain, months (SD): 14.2 (8.3)

|

Steroid/lidocaine injections into posterior neck muscles (n= 17) |

1 week and 1 year after injections |

Pain (VAS), functioning (recovery of capacity for work), medication use (decreased daily dose of analgesics), complications (worse pain (yes/no)) |

MSQ, Medication Quantitative Scale; NDI, Neck Disability Index; NRS, Numeric Rating Scale; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale

Results

1. Pain (critical)

Five studies reported on pain (Anderberg, 2007; Bureau, 2014; Cohen, 2014; Manchikanti, 2012; Stav, 1993). Results are presented in three post-intervention terms: a) short term: until 30 days, b) mid-term: >30 days to 3 months, and c) long term: >3 months to 1 year. A brief overview of the main characteristics is provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Overview on post-intervention terms

|

Study |

Follow-up |

Term |

Scale |

|

Anderberg, 2007 |

1, 2 and 3 weeks |

Short term |

Arm pain and/or neurological deficits (VAS-scale, yes/no) |

|

Bureau, 2014 |

4 weeks |

Short term |

Mean change from baseline score of 62.4 (VAS-scale, 0-100) |

|

Cohen, 2014 |

1, 3 and 6 months |

Short term, mid-term, long term |

Mean score on numerical rating pain scale for arm and neck-pain (NRS-scale, 0-10) |

|

Decrease of ≥2 points on arm pain (NRS-scale, yes/no) |

|||

|

Manchikanti, 2012 |

3, 6 and 12 months |

Mid-term, long term |

Pain relief (NRS-scale, 0-10) |

|

Stav, 1993 |

1 week and 12 months |

Short term, long term |

Pain decrease of ≥50% (VAS-scale, yes/no) |

NRS: Numeric rating scale; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale

1a. Short term arm pain (post-treatment: 30 days)

Four studies reported on pain up to 30 days (Anderberg, 2007; Bureau, 2014; Cohen, 2014; Stav, 1993).

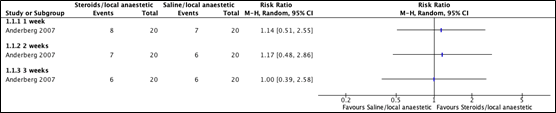

Local anaesthetic with steroids vs. local anaesthetic alone

Anderberg (2007) reported results for one, two and three weeks after injection. One week after injection, eight out of twenty (40%) participants in the intervention group and seven out of twenty (35%) participants in the control group reported a reduction. This resulted in a risk ratio of 1.14 (95%CI 0.51 to 2.55). Two weeks after injection, in seven (35%) participants in the steroid treatment group, and in six (30%) participants in the control group the effect was maintained. This resulted in a risk ratio of 1.17 (95%CI 0.48 to 2.86). These effects were not clinically relevant. Three weeks after injection, in six participants in the intervention group (30%) and six participants in the control group (30%) the effect was maintained. This resulted in a risk ratio of 1.00 (95%CI 0.39 to 2.58). Results are depicted in figure 1.

Figure 1. Mean differences for arm pain, local anaesthetic with steroids versus anaesthetic alone

(follow-up: 1-3 weeks)

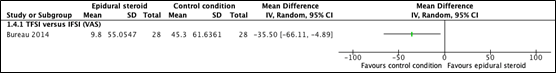

Transforaminal vs. intra-articular facet corticosteroid injections

Bureau (2014) reported results for four weeks after baseline. In the TFSI-group, mean VAS-scores reduced with 9.8% (95%CI -11.5 to 31.2). In the IFSI-group, VAS-scores reduced with 45.3% (95%CI 21.4 to 69.2). The analysis resulted in a mean difference of -35.50 (95%CI -66.1 to -4.89) favouring the IFSI-group. This difference was clinically relevant. Results are depicted in figure 2.

Figure 2. Mean differences in pain, transforaminal versus intra-articular facet corticosteroid injections.

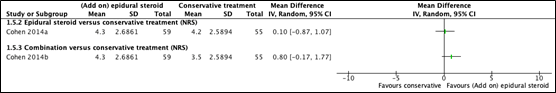

Epidural steroids with or without conservative treatment vs. conservative treatment alone

Cohen (2014) reported results for arm pain one month after injection. In the epidural steroid injection group, the mean score was 4.2 (SD 2.59). In the combined group, mean score was 3.5 (SD 2.59). In the group with conservative treatment, the mean score was 4.3 (SD 2.69). The mean difference between the epidural steroid group and the conservative treatment group was 0.1 (95%CI -0.87 to 1.07). The mean difference between the combination group and the conservative treatment group was 0.80 (95%CI -0.17 to 1.77). Results are depicted in figure 3.

Figure 3. Mean differences in arm pain, epidural steroids with hand without conservative treatment versus conservative treatment alone.

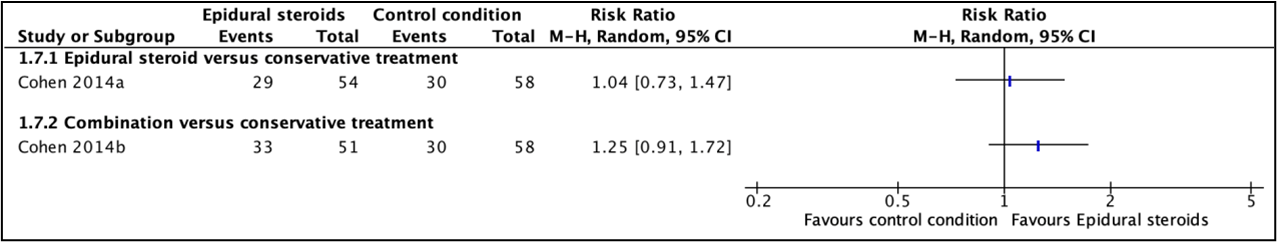

After 1 month, 29 (53.7%) of the participants in the epidural steroid group, 30 (51.7%) participants in the conservative treatment group and 33 (64.7%) participants in the combined group reported a successful treatment outcome. The risk ratio between the group receiving conservative treatment and the group receiving epidural steroids was 1.04 (95%CI 0.73 to 1.47). The risk ratio between the group receiving conservative treatment and combination treatment was 1.25 (95%CI 0.91 to 1.72) are depicted in figure 4.

Figure 4. Risk ratios for successful treatment outcome, epidural steroids with and without conservative treatment versus conservative treatment alone

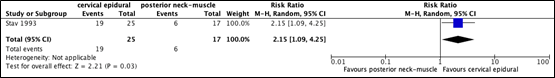

Cervical epidural steroid injection vs. steroid injections into posterior neck muscles

Stav (1993) reported results for one week after injection. Very good and good scores were considered as pain relief.

After one week, in the cervical epidural steroid group 19 out of 25 participants (76%) experienced pain relief, compared to 6 out of 17 participants (35%) in the posterior neck-muscle steroid group. This resulted in a risk ratio of 2.15 (95%CI 1.09 to 4.25), favouring the cervical epidural group. This difference was clinically relevant. Results are depicted in figure 5.

Figure 5. Risk ratios for pain relief, cervical epidural steroid injection versus steroid injection into posterior neck muscles

1b. Mid-term arm pain (post-treatment: >30 days to 3 months)

Two studies reported on pain after 30 days up to 3 months (Cohen, 2014; Manchikanti, 2012).

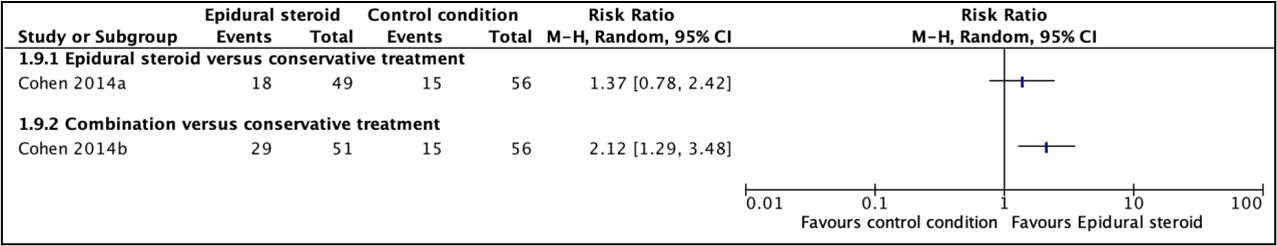

Epidural steroids with or without conservative treatment vs. conservative treatment alone

Cohen (2014) reported results for 3 months after injection. 18 (36.7%) of the participants in the epidural steroid group, 15 (26.8%) participants in the conservative treatment group and 29 (56.9%) participants in the combined group reported a successful treatment outcome. This resulted in a risk ratio of 1.37 (95%CI 0.78 to 2.42).

The risk ratio between the group receiving conservative treatment and combination treatment was 2.12 (95%CI 1.29 to 3.48), favouring the combined group. These differences were clinically relevant. Results are depicted in figure 6.

Figure 6. Mean differences for arm pain 3 months after injection, Epidural steroids with or without conservative treatment versus conservative treatment alone.

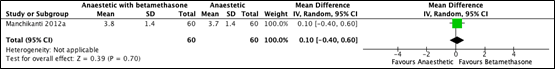

Cervical interlaminar injections with anaesthetic and betamethasone vs. anaesthetic alone

Manchikanti (2012) reported results for three months after injection. After 3 months, the mean difference between anaesthetic with betamethasone group and the anaesthetic group was 0.1 (95%CI -0.40 to 0.60). Results are depicted in figure 7.

Figure 7. Mean difference for pain 3 months after injection, Cervical interlaminar injections with anaesthetic and betamethasone versus anaesthetic alone

1c. Long term arm pain (post-treatment: >3 months to 1 year):

Three studies reported on pain over 3 months up to one year after injection (Cohen, 2014; Manchikanti, 2012; Stav, 1993).

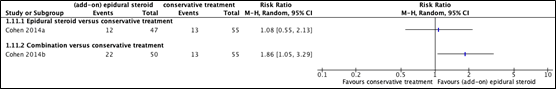

Epidural steroids with or without conservative treatment vs. conservative treatment alone

Cohen (2014) reported results for 6 months after injection. 12 (25.5%) of the participants in the epidural steroid group, 13 (23.6%) participants in the conservative treatment group and 22 (44%) participants in the combined group reported a successful treatment outcome. The risk ratio between the epidural steroid group and the conservative treatment group was 1.08 (95%CI 0.55 to 2.13).

The risk ratio between the group receiving conservative treatment and combination treatment was 1.86 (95%CI 1.05 to 3.29), favouring the combined group. This difference was clinically relevant. Results are depicted in figure 8.

Figure 8. Risk ratio for successful treatment outcome, Epidural steroids with or without conservative treatment versus conservative treatment alone

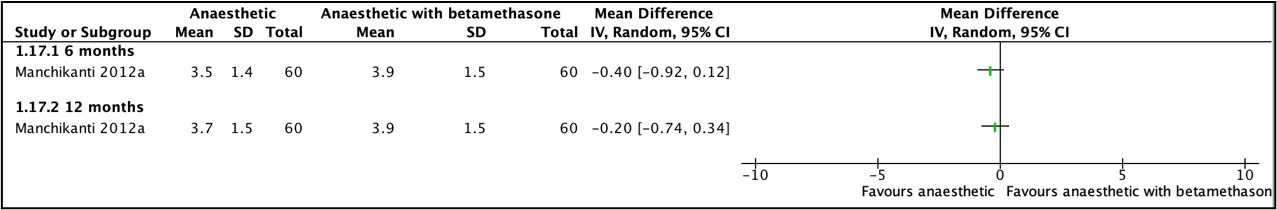

Cervical interlaminar injections with anaesthetic and betamethasone vs. anaesthetic alone

Manchikanti (2012) reported results for 6 months after injection. After 6 months, the mean difference between the anaesthetic group and the group receiving betamethasone plus anaesthetic was -0.40 (95%CI -0.92 to 0.12). After 12 months, the mean difference was -0.20 (95%CI -0.74 to 0.34). Results are depicted in figure 9.

Figure 9. Mean difference for pain, Cervical interlaminar injections with anaesthetic and betamethasone versus anaesthetic alone.

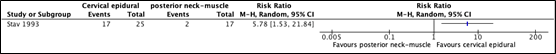

Cervical epidural steroid injection vs. steroid injections into posterior neck muscles

Stav (1993) reported results for one year after injection. Very good and good scores were considered as pain relief.

After one year, in the cervical epidural group 17 out of 25 participants (68%) experienced pain relief, compared to 2 out of 17 (12%) participants in the posterior neck-muscle group. This resulted in a risk ratio of 5.78 (95%CI 1.53 to 21.84), favouring the cervical epidural group. This difference was clinically relevant. Results are depicted in figure 10.

Figure 10. Risk ratio for pain relief, Cervical epidural steroid injection versus steroid injections into posterior neck muscles

1d. Short term neck pain (post-treatment: 30 days)

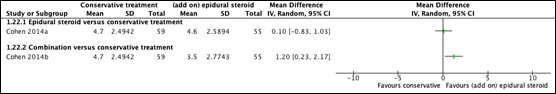

Epidural steroids with or without conservative treatment vs. conservative treatment alone

Cohen (2014) reported results for neck pain one month after injection. In the epidural steroid injection group, the mean score was 4.6 (SD 2.59). In the combined group, mean score was 3.5 (SD 2.77). In the group with conservative treatment, the mean score was 4.7 (SD 2.49). The mean difference between the epidural steroid group and the conservative treatment group was 0.10 (95%CI -0.83 to 1.03).

The mean difference between the combination group and the conservative treatment group was 1.20 (95%CI 0.23 to 2.17), favouring the combined group. This difference was clinically relevant. Results are depicted in figure 11.

Figure 11. Mean differences for neck pain 30 days after injection, Epidural steroids with or without conservative treatment versus conservative treatment alone.

2. Patient satisfaction (critical)

One study reported on patient satisfaction (Cohen, 2014).

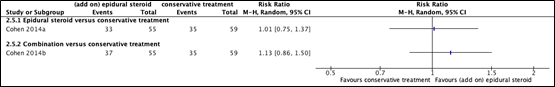

Epidural steroids with or without conservative treatment vs. conservative treatment alone

Cohen (2014) reported on patient satisfaction using the global perceived effect (GPE). The GPE was considered positive when both, arm pain was reduced since baseline for two points or more, and the participant was satisfied with the treatment. This was measured with the two statements “my pain has improved/worsened/stayed the same since my last visit” and “I am satisfied/not satisfied with the treatment I received and would/would not recommend it to others”. A positive GPE was reported in 33 (61.1%) participants in the epidural steroid group, in 37 participants (72.6%) in the combined group and in 35 (60.3%) participants in the conservative group.

The risk ratio between the epidural steroid group and the conservative group was 1.01 (95%CI 0.75 to 1.37). The risk ratio between the combined group and the conservative treatment group was 1.07 (95%CI 0.87 to 1.32). Results are depicted in figure 12.

Figure 12. Risk ratio for positive Global Perceived Effect, Epidural steroids with or without conservative treatment versus conservative treatment alone.

3. Complications (critical)

Five studies reported on complications (Anderberg, 2007; Bureau, 2014; Cohen, 2014; Manchikanti, 2012; Stav, 1993).

Local anaesthetic with steroids vs. local anaesthetic alone

Anderberg (2007) reported no serious complications. Five out of 40 patients reported minor complications. One participant experienced an allergic skin reaction, and four participants experienced increase in radicular pain for some days after injections. None of the participants reported any persisting negative effects three weeks after the intervention.

Transforaminal vs. intra-articular facet corticosteroid injections

Bureau (2014) reported that one participant in the TFSI-group had tinnitus and vertigo after the intervention. In both groups, one participant reported having headaches in the two days following the injections. For adverse events, results were presented for participants as treated. The participant reporting headache in the IFSI-group actually received TFSI. Thus, all participants reporting adverse events received TFSI.

Epidural steroids with or without conservative treatment vs. conservative treatment alone

Cohen (2014) reported that ten complications occurred in eight participants receiving epidural steroids or combined treatment. Two headaches were reported, one wet-tap (not associated with neurological sequalae), one participant experienced prolonged post procedure pain, and in two participants the neurological symptoms worsened for less than two weeks. Furthermore, one rash, two vasovagal episodes and one case of tachycardia (resolved with assurance) were reported.

Cervical interlaminar injections with anaesthetic and betamethasone vs. anaesthetic alone

Manchikanti (2012) did not report on complications per arm. One participant had a subarachnoid puncture, intravascular penetrations appeared in three participants, and one participant reported soreness for seven days.

Cervical epidural steroid injection vs. steroid injections into posterior neck muscles

In Stav (1993), two participants in the intervention-group and two participants in the control-group experienced worse pain after one week. This did not change after 1 year.

Outcomes for complications were not pooled, because complications were often not reported per group, the low number of events, and definitions of complications were not similar enough to ensure a clinical meaningful answer.

4. Use of medication (important)

Four studies reported on use of medication (Bureau, 2014; Cohen, 2014; Manchikanti, 2012; Stav, 1993).

Transforaminal vs. intra-articular facet corticosteroid injections

Bureau (2014) reported pain outcomes using the Medication Quantitative Scale-scale (MQS-scale) at four weeks after injection. At baseline, subjects were instructed continuing with their usual medication. However, mean differences were presented for different groups by baseline VAS-score. For this reason, this outcome could not be graded.

Epidural steroids with or without conservative treatment vs. conservative treatment alone

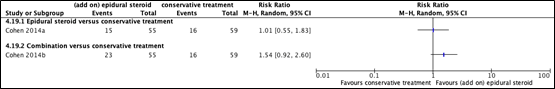

Cohen (2014) reported use of medication in whether a participant reduced their opioid use with ≥20%, or completely quit using non-opioids. The study did not provide information on whether changed intake of opioids was based on prescription or initiative of the participant. Reduced medication use was reported in 15 (34.9%) participants in the epidural steroid group, 16 (35.6%) participants in the conservative treatment group, and in 23 (54.8%) participants in the combined group. The risk ratio between the epidural steroid group and the conservative group was 1.01 (95%CI 0.55 to 1.83).

The risk ratio between the combined group and the conservative group was 1.54 (95%CI 0.86 to 1.89). Results are depicted in figure 13.

Figure 13. Risk ratio for reduced opioid intake, Epidural steroids with or without conservative treatment versus conservative treatment alone.

Cervical interlaminar injections with anaesthetic and betamethasone vs. anaesthetic alone

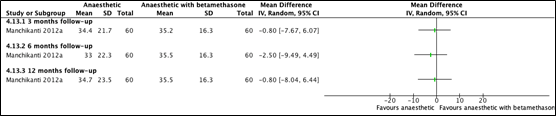

Manchikanti (2012) reported medication use in changes in intake of morphine equivalents. The study did not provide information on whether changed intake of opioids was based on prescription or initiative of the participant. Baseline morphine intake was 53.8 (SD 36.1) in the betamethasone group, and 57.0 (SD 46.1) in the anaesthetic group. At 3 months, mean difference in medication use was -0.80 (95%CI -7.67 to 6.07). At 6 months, mean difference in medication use was -2.50 (95%CI -9.49 to 4.49). At 12 months, mean difference in medication use was -0.80 (95%CI -8.04 to 6.44). Results are depicted in figure 14.

Figure 14. Mean differences for intake of morphine equivalents Cervical interlaminar injections with anaesthetic and betamethasone versus anaesthetic alone.

Cervical epidural steroid injection vs. steroid injections into posterior neck muscles

Stav (1993) reported on medication use in whether a participant reduced their daily dose of analgesics. The study did not provide information on whether changed intake of medication was based on prescription or initiative of the participant. After one-week, reduced use of analgesics was reported in 81.7% of the participants in the cervical epidural steroid group, and in 8.6% of the participants in the posterior neck-muscle group. After one year 63.9% participants in the cervical epidural steroid group reduced their use of analgesics compared to 9.4% of the participants in the posterior neck-muscle group. Upon subsequent calculation, these percentages could not be translated to risk ratios. These results were therefore not graded.

5. Functioning (important)

Cervical interlaminar injections with anaesthetic and betamethasone vs. anaesthetic alone

Manchikanti (2012) reported on functioning using employment characteristics. Results are presented in (table 3), however these results could not be evaluated using GRADE.

Table 3. Employment characteristics

|

|

Group 1 |

Group 2 |

||

|

Employment status |

Baseline |

12 months |

Baseline |

12 months |

|

Total employed/eligible for employment at baseline |

11/13 |

11/13 |

15/22 |

17/22 |

|

Unemployed due to pain/eligible for employment at baseline |

0/13 |

0/13 |

2/22 |

1/22 |

|

Disabled/total |

37/60 |

37/60 |

33/60 |

33/60 |

|

Retired/total |

7/60 |

7/60 |

4/60 |

4/60 |

Cervical epidural steroid injection vs. steroid injections into posterior neck muscles

Stav (1993) reported on functioning using recovery of capacity for work. After one week, recovered capacity for work was reported in 69.4% of the participants in the cervical epidural steroid group and in 12.8% of the participants in the posterior neck-muscle group. After one year, 61.3% participants in the cervical epidural steroid group recovered capacity for work, compared to 15.9% of the participants in the posterior neck-muscle group. Upon subsequent calculation, these percentages could not be translated to risk ratios. These results were therefore not evaluated using GRADE.

6. Disability

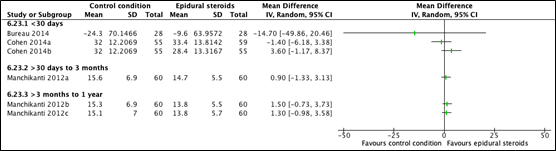

Three studies reported on disability (Bureau, 2013; Cohen, 2014; Manchikanti, 2012) using the Neck Disability Index (NDI).

6a. Short term disability (post-treatment: 30 days)

Transforaminal vs. intra-articular facet corticosteroid injections

Bureau (2014) reported results for four weeks after baseline, using the NDI range 0-50. In the TFSI-group, mean NDI-scores reduced with 9.6% (SD 64.0). In the IFSI-group, NDI-scores reduced with 24.3% (SD 70.1). This corresponds with a decrease of 4.8 points in the TFSI-group (95%CI -17.2 to 7.6) and a decrease of 12.15 points in the IFSI-group (95%CI -25.75 to 1.45). The analysis resulted in a mean difference of -14.7 (95%CI -49.9 to 18.4).

Epidural steroids with or without conservative treatment vs. conservative treatment alone

Cohen (2014) reported results for disability one month after injection, using the NDI range 0-100. In the epidural steroid injection group, the mean score was 33.4 (SD 13.8). In the group with conservative treatment, the mean score was 32.0 (SD 12.2). In the combined group, mean score was 28.4 (SD 13.3). The mean difference between the epidural steroid group and the conservative treatment group was -1.40 (95%CI -6.18 to 3.38).

The mean difference between the combination group and the conservative treatment group was 3.60 (95%CI -1.17 to 8.37).

6b. Mid-term disability (post-treatment: >30 days to 3 months)

Cervical interlaminar injections with anaesthetic and betamethasone vs. anaesthetic alone

Manchikanti (2012) reported results for 3 months after baseline using the NDI range 0-100. At baseline, mean score in the anaesthetic group was 29.6 (SD 5.3) and 29.2 (SD 6.1) in the betamethasone group. In the anaesthetic group, mean score after 3 months was 14.7 (SD 5.5) and mean score in the betamethasone group was 15.6 (SD 6.3). The analysis resulted in a mean difference of 0.90 (95%CI -1.33 to 3.13).

6c. Long term disability (post-treatment: >3 months to 1 year)

Cervical interlaminar injections with anaesthetic and betamethasone vs. anaesthetic alone

Long term results were reported by Manchikanti (2012). After 6 months, the mean score in the anaesthetic group was 13.8 (SD 5.4) and the mean score in the betamethasone group was 15.3 (SD 6.9). The mean difference between the anaesthetic group and the betamethasone group was 1.50 (95%CI 0.73 to 3.72). After 12 months, the mean score in the anaesthetic group was 13.8 (SD 5.7) and the mean score in the betamethasone group was 15.1 (SD 7.0). The mean difference between the anaesthetic group and the betamethasone group was 1.30 (95%CI -0.98 to 3.58). Results are depicted in figure 15.

Figure 15. Mean differences of Neck Disability Index-scores

7. Quality of life (important)

The outcome quality of life was not reported in the included studies.

8. Surgery sparing effect (important)

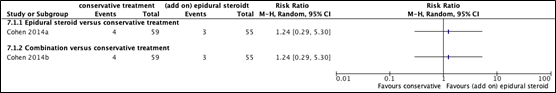

One study reported on cervical surgery sparing effect (Cohen, 2014).

Epidural steroids with or without conservative treatment vs. conservative treatment alone

Cohen (2014) reported whether a participant proceeded for surgery within one year of treatment. Surgery within one year of treatment was reported in 3 (5.5%) participants in the epidural steroid group, in 4 (6.8%) participants in the conservative treatment group and in 3 (5.5%) participants in the combined group. Both risk ratios comparing epidural steroids or combined treatment with conservative treatment, were 1.24 (95%CI 0.29 to 5.30).

Figure 17. Risk ratio’s for proceeding for surgery within one year of treatment, Epidural steroids with or without conservative treatment versus conservative treatment alone.

Level of evidence of the literature

1. Pain (critical)

1.1 Short term

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain (short term) started as high because it was based on RCTs and was downgraded by three levels to very low because lack of blinding (Cohen, 2014) (-1, risk of bias), clinical heterogeneity (-1, inconsistency), and crossing of both thresholds of clinical decision-making (Cohen, 2014; Anderberg; 2007) (-1, imprecision).

1.2 Mid term

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain (mid-term) started as high because it was based on RCTs and was downgraded by three levels to very low because lack of blinding (Cohen, 2014) (-1, risk of bias), clinical heterogeneity (-1, inconsistency) and crossing of one threshold of clinical decision-making (Cohen, 2014) (-1, imprecision).

1.3 Long term

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain (long-term) started as high because it was based on RCTs and was downgraded by three levels to very low because lack of blinding (Cohen, 2014; Stav, 1993) (-1, risk of bias) clinical heterogeneity (-1, inconsistency) and crossing of one threshold of clinical decision-making (Cohen, 2014; Stav, 1993) (-1, imprecision).

2. Patient satisfaction (critical)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure patient satisfaction started as high because it was based on RCTs and was downgraded by three levels to very low because lack of blinding in a self-reported outcome without any compensating RCTs of adequate quality (Cohen, 2014) (-2, risk of bias) and crossing of both thresholds of clinical decision-making (-1, imprecision).

3. Complications (critical)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure complications started as high because it was based on RCTs and was downgraded by three level to very low because of methodological shortcomings (Cohen, 2014 and Stav, 1993) (-1, risk of bias), strong heterogeneity in outcome-definition (-1, inconsistency) and a low number of events (-1, imprecision).

4. Use of medication (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure medication use started as high because it was based on RCTs and was downgraded by three levels to very low because lack of blinding (Cohen, 2014) (-1, risk of bias) and intervals crossing borders of clinical relevance (Cohen, 2014; Manchikanti, 2012) (-2, imprecision).

5. Functioning (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure functioning was not assessed.

6. Disability

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure disability started as high because it was based on RCTs and was downgraded by three levels to very low because lack of blinding (Cohen, 2014) (-1, risk of bias), clinical and statistical heterogeneity (-1, inconsistency) confidence intervals crossing borders of clinical relevance (Bureau, 2014; (-1, imprecision).

7. Quality of life (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life was not assessed.

8. Surgery sparing effect (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure cervical surgery started as high because it was based on an RCT and was downgraded by three levels to very low because lack of blinding (Cohen, 2014) (-1, risk of bias) and confidence interval crossing both borders of clinical relevance (-2, imprecision).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the efficacy of epidural steroid injections compared to care as usual in patients with cervical radiculopathy?

P: Patients with cervical radiculopathy (acute or sub-acute)

I: (Add on) epidural corticosteroid injections with or without local anaesthetic injection (transforaminal/midline or interlaminar)

C: Other conservative treatment possibilities

O: Pain, patient satisfaction, complications, use of medication, functioning, disability, quality of life, surgery sparing effect

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered pain, patient satisfaction, and complications as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and use of medication, functioning (return to work), quality of life and surgery sparing effect as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

- Patient satisfaction: Likert-scale or global perceived effect (GPE)

- Functioning: Return to work

- Quality of life: Validated questionnaires

A priori, the working group did not define other outcome measures but used the definitions from the studies.

The working group defined a 10% difference for both continuous outcome measures and dichotomous outcome measures informing on relative risk (RR ≤ 0.91 and ≥ 1.1), and standardized mean difference (SMD=0,2 (small); SMD=0,5 (medium); SMD=0,8 (large)) as minimal clinically (patient) important differences. This decision was based on the minimal important change scores described in the article by Ostelo (2008), in accordance with the Dutch Lumbosacral Radicular syndrome guideline (NVN, 2020).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 1990 until 25 April 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 382 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic review (searched in at least two databases, and detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment and results of individual studies available), randomized controlled trial comparing epidural steroid injections with other conservative treatment possibilities;

- Patients aged ≥ 18 years;

- Full-text English or Dutch language publication;

- Studies including ≥ 20 patients (ten in each study arm); and

- Studies according to PICO

Initially, 37 studies were selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 32 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and five studies were included.

Results

Five studies were included in the analysis of the literature. A comprehensive overview of study characteristics is depicted in Table 1. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence table. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias table.

Referenties

- Alvin MD, Mehta V, Halabi HA, Lubelski D, Benzel EC, Mroz TE. Cost-Effectiveness of Cervical Epidural Steroid Injections: A 3-Month Pilot Study. Global Spine J. 2019 Apr;9(2):143-149. Doi: 10.1177/2192568218764913. Epub 2018 Jul 31. PMID: 30984492; PMCID: PMC6448201.

- Anderberg L, Annertz M, Persson L, Brandt L, Säveland H. Transforaminal steroid injections for the treatment of cervical radiculopathy: a prospective and randomised study. Eur Spine J. 2007 Mar;16(3):321-8. Doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0142-8. Epub 2006 Jul 12. PMID: 16835737; PMCID: PMC2200696.

- Benyamin RM, Singh V, Parr AT, Conn A, Diwan S, Abdi S. Systematic review of the effectiveness of cervical epidurals in the management of chronic neck pain. Pain Physician. 2009 Jan-Feb;12(1):137-57. PMID: 19165300.

- Benzon HT, Huntoon MA, Rathmell JP. Improving the safety of epidural steroid injections. JAMA. 2015 May 5;313(17):1713-4. Doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.2912. PMID: 25822848.

- Van Boxem K, Rijsdijk M, Hans G, de Jong J, Kallewaard JW, Vissers K, van Kleef M, Rathmell JP, Van Zundert J. Safe Use of Epidural Corticosteroid Injections: Recommendations of the WIP Benelux Work Group. Pain Pract. 2019 Jan;19(1):61-92. Doi: 10.1111/papr.12709. Epub 2018 Jul 2. PMID: 29756333; PMCID: PMC7379698.

- Bureau NJ, Moser T, Dagher JH, Shedid D, Li M, Brassard P, Leduc BE. Transforaminal versus intra-articular facet corticosteroid injections for the treatment of cervical radiculopathy: a randomized, double-blind, controlled study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014 Aug;35(8):1467-74. Doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4026. Epub 2014 May 29. PMID: 24874533; PMCID: PMC7964459.

- Celenlioglu AE, Solmaz I, Eksert S, Simsek F, Ilkbahar S, Sir E. Factors Associated with Treatment Success After Interlaminar Epidural Steroid Injection for Cervical Radicular Pain. Turk Neurosurg. 2023;33(2):326-333. Doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.42539-22.2. PMID: 36799281.

- Chae JS, Kim WJ, Jue MJ. Facet Joint Versus Transforaminal Epidural Steroid Injections in Patients With Cervical Radicular Pain due to Foraminal Stenosis: A Retrospective Comparative Study. J Korean Med Sci. 2022 Jun 27;37(25):e208. Doi: 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e208. PMID: 35762147; PMCID: PMC9239844.

- Cohen SP, Hayek S, Semenov Y, Pasquina PF, White RL, Veizi E, Huang JH, Kurihara C, Zhao Z, Guthmiller KB, Griffith SR, Verdun AV, Giampetro DM, Vorobeychik Y. Epidural steroid injections, conservative treatment, or combination treatment for cervical radicular pain: a multicenter, randomized, comparative-effectiveness study. Anesthesiology. 2014 Nov;121(5):1045-55. Doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000409. PMID: 25335172.

- Cui X, Zhang D, Zhao Y, Song Y, He L, Zhang J. An open-label non-inferiority randomized trail comparing the effectiveness and safety of ultrasound-guided selective cervical nerve root block and fluoroscopy-guided cervical transforaminal epidural block for cervical radiculopathy. Ann Med. 2022 Dec;54(1):2681-2691. Doi: 10.1080/07853890.2022.2124445. PMID: 36164681; PMCID: PMC9553110.

- DIS open data, www.opendisdata.nl, Nederlandse Zorgautoriteit, geraadpleegd op 19 juli, 2023

- Hochberg U, Perez MF, Brill S, Khashan M, de Santiago J. A New Solution to an Old Problem: Ultrasound-guided Cervical Retrolaminar Injection for Acute Cervical Radicular Pain: Prospective Clinical Pilot Study and Cadaveric Study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2021 Oct 15;46(20):1370-1377. Doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000004024. PMID: 33660679.

- Hong H, Wang C, Rosner GL. Meta-analysis of rare adverse events in randomized clinical trials: Bayesian and frequentist methods. Clin Trials. 2021 Feb;18(1):3-16. Doi: 10.1177/1740774520969136. Epub 2020 Dec 1. PMID: 33258698; PMCID: PMC8041270.

- Joswig H, Neff A, Ruppert C, Hildebrandt G, Stienen MN. Repeat epidural steroid injections for radicular pain due to lumbar or cervical disc herniation: what happens after salvage treatment? Bone Joint J. 2018 Oct;100-B(10):1364-1371. Doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.100B10.BJJ-2018-0461.R1. PMID: 30295524.

- Malhotra G, Abbasi A, Rhee M. Complications of transforaminal cervical epidural steroid injections. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009 Apr 1;34(7):731-9. Doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318194e247. PMID: 19333107.

- Manchikanti L, Cash KA, Pampati V, Wargo BW, Malla Y. Management of chronic pain of cervical disc herniation and radiculitis with fluoroscopic cervical interlaminar epidural injections. Int J Med Sci. 2012;9(6):424-34. Doi: 10.7150/ijms.4444. Epub 2012 Jul 23. PMID: 22859902; PMCID: PMC3410361.

- Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Parr Iii A, Manchikanti MV, Sanapati MR, Kaye AD, Hirsch JA. Cervical Interlaminar Epidural Injections in the Treatment of Cervical Disc Herniation, Post Surgery Syndrome, or Discogenic Pain: Cost Utility Analysis from Randomized Trials. Pain Physician. 2019 Sep;22(5):421-431. PMID: 31561644.

- Narouze S, Benzon HT, Provenzano D, Buvanendran A, De Andres J, Deer T, Rauck R, Huntoon MA. Interventional Spine and Pain Procedures in Patients on Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Medications (Second Edition): Guidelines From the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, the International Neuromodulation Society, the North American Neuromodulation Society, and the World Institute of Pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018 Apr;43(3):225-262. Doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000700. PMID: 29278603.

- Park CH, Lee SH. Feasibility of Contralateral Oblique Fluoroscopy-guided Cervical Interlaminar Steroid Injections. Pain Pract. 2016 Sep;16(7):814-9. Doi: 10.1111/papr.12341. Epub 2015 Aug 27. PMID: 26310909.

- Peene L, Cohen SP, Brouwer B, James R, Wolff A, Van Boxem K, Van Zundert J. 2. Cervical radicular pain. Pain Pract. 2023 Jun 4. Doi: 10.1111/papr.13252. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37272250.

- Rathmell JP, Benzon HT, Dreyfuss P, Huntoon M, Wallace M, Baker R, Riew KD, Rosenquist RW, Aprill C, Rost NS, Buvanendran A, Kreiner DS, Bogduk N, Fourney DR, Fraifeld E, Horn S, Stone J, Vorenkamp K, Lawler G, Summers J, Kloth D, OBrien D Jr, Tutton S. Safeguards to prevent neurologic complications after epidural steroid injections: consensus opinions from a multidisciplinary working group and national organizations. Anesthesiology. 2015 May;122(5):974-84. Doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000614. PMID: 25668411.

- Sacaklidir R, Sanal-Toprak C, Yucel FN, Gunduz OH, Sencan S. The Effect of Central Sensitization on Interlaminar Epidural Steroid Injection Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Cervical Disc Herniation: An Observational Study. Pain Physician. 2022 Sep;25(6):E823-E829. PMID: 36122265.

- Schneider B, Zheng P, Mattie R, Kennedy DJ. Safety of epidural steroid injections. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016 Aug;15(8):1031-9. Doi: 10.1080/14740338.2016.1184246. Epub 2016 May 13. PMID: 27148630.

- Stav A, Ovadia L, Sternberg A, Kaadan M, Weksler N. Cervical epidural steroid injection for cervicobrachialgia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1993 Aug;37(6):562-6. Doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1993.tb03765.x. PMID: 8213020.

- Ulusoy OL, Alis D, Mutlu A, Colakoglu B, Sirvanci M. The preliminary results of a new CT-guided periradicular cervical steroid injection technique: safety and feasibility of the lateral peri-isthmic approach in 28 patients. Skeletal Radiol. 2018 Dec;47(12):1607-1613. Doi: 10.1007/s00256-018-2986-5. Epub 2018 Jun 7. PMID: 29882012.

- Vallejo MC, Zakowski MI. Post-dural puncture headache diagnosis and management. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2022 May;36(1):179-189. Doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2022.01.002. Epub 2022 Jan 25. PMID: 35659954.

- Van Boxem K, Rijsdijk M, Hans G, de Jong J, Kallewaard JW, Vissers K, van Kleef M, Rathmell JP, Van Zundert J. Safe Use of Epidural Corticosteroid Injections: Recommendations of the WIP Benelux Work Group. Pain Pract. 2019 Jan;19(1):61-92. Doi: 10.1111/papr.12709. Epub 2018 Jul 2. PMID: 29756333; PMCID: PMC7379698.

- Van Zundert J, Huntoon M, Patijn J, Lataster A, Mekhail N, van Kleef M; Pain Practice. 4. Cervical radicular pain. Pain Pract. 2010 Jan-Feb;10(1):1-17. Doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2009.00319.x. Epub 2009 Oct 5. PMID: 19807874.

Evidence tabellen

Risk of bias table for intervention studies

|

Study reference

|

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

|

Was the allocation adequately concealed? |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented? |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

|

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting? |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias? |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

|

|

Anderberg, 2007 |

Probably yes;

Reason: No information |

Probably yes;

Reason: No information |

Probably yes;

Reason: Patients were blinded. The healthcare provider (neuroradiologist) was not blinded, all other persons involved in the study were declared blinded. |

Probably yes;

Reason: No loss to follow-up appeared, all patients available for outcome assessment. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: |

Definitely yes;

Reason: |

Some concerns (all outcomes) |

|

Bureau, 2014 |

Probably yes;

Reason: Randomization was computer-generated |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Envelopes were sealed. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Patients were blinded. The healthcare provider (radiologist) was not blinded, research assistant, also outcome assessor/data collector, was blinded. Not mentioned whether data-analysts were blinded. |

Probably yes

Reason: No subjects were lost to follow-up and patients were analysed according to randomization (ITT). Two TFSI subjects received IFSI. One subject randomized to IFSI received TFSI by mistake. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No registration in on Clinical Trials.gov was found. However, all predefined outcomes were reported in the publication. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: The study was not suspected of any other biases. |

LOW (all outcomes)

|

|

Cohen, 2014 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Randomization was computer-generated |

Probably yes;

Reason: No information, but estimated low risk |

Defenitely no;

Reason: Probably due to the nature of the control group (conservative treatment), blinding participants was not pursued/possible.

Blinding of healthcare providers, data collectors, outcome assessors or data analysts was not reported. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Slightly imbalanced drop-out between epidural steroid group and conservative group, however it did probably not bias the effect estimates.

For 3 and 6 month follow-up, the last-observation carried forward method was used. |

Defenitely yes;

Reason: No registration in on Clinical Trials.gov was found. However, all predefined outcomes were reported in the publication. |

Probably yes;

Reason: The study was not suspected of any other biases. |

HIGH (pain, use of medication, patient satisfaction, cervical surgery)

|

|

Manchikanti, 2012 |

Defenitely yes;

Reason: Allocation sequence was computer-generated |

Probably yes;

Reason: No information, but estimated low risk |

Probably no;

Reason: patients were blinded, as were healthcare providers. Data collector was not blinded, but did not reveal any allocation- information.

|

Probably yes;

Reason: Drop-out rate 5/120 not perceived to bias the effect estimates. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Study registered at NCT01071369. No outcomes were predefined in the protocol. All outcomes predefined in the method-section were reported in the publication. |

Probably yes;

Reason: The study was not suspected of any other biases. |

LOW (all outcomes) |

|

Stav, 1993 |

Probably no;

Reason: No information |

Probably no;

Reason: no information |

Defenitely no

Reason: Blinding was not described in either person involved in the study. |

Defenitely no;

Drop out seems to be related to treatment, since litigation of insurance claims from 8 patients in control-group. |

Probably no;

No registration found. All predefined outcomes were described in results. |

Probably no;

Reason: All assessments were only briefly described, patients were excluded from analysis for policy-reasons and outcomes were described in a limited way. |

HIGH (all outcomes) |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reasons |

|

Pountos 2016 |

Reported on incidence of AE, not compared with comparison group (wrong comparison) |

|

Bush 1996 |

results not stratified according to type of injection (wrong control) |

|

Kumar 2008 |

all participants received injections with corticosteroids (wrong control) |

|

Lin 2006 |

all participants received epidural injections with corticosteroids (wrong control) |

|

Persson 2012 |

all participants received epidural injections with corticosteroids (wrong control) |

|

Shakir 2013 |

all participants received epidural injections with corticosteroids (wrong control) |

|

Vallee 2001 |

all participants received epidural injections with corticosteroids (wrong control) |

|

Lee 2009 |

all participants received epidural injections with corticosteroids (wrong control) |

|

Lee 2022 |

Stellate ganglion block (Jan+Germine: no usual care) versus cervical epidural steroid injection (wrong control) |

|

Jang 2020 |

Selective Nerve Root Block (Jan+Germine: no usual care) versus Fluoroscopy-Guided Interlaminar Epidural Block versus Fluoroscopy-Guided Transforaminal Epidural Bloc |

|

Abdi 2005 |

SR, maar op Stav (1993) na, geen relevante vergelijkende studies, veelal over lumbar (wrong population, no recent review) |

|

Abdi 2007 |

SR, maar op Stav (1993) na, geen relevante vergelijkende studies, veelal over lumbar (wrong population, no recent review) |

|

Benyamin 2009 |

SR, maar op Stav (1993) na, geen relevante vergelijkende studies (wrong control, no recent review) |

|

Boswell 2007 |

SR, maar op Stav (1993) na, geen relevante vergelijkende studies (wrong control, no recent review) |

|

Benditz 2017 |

All participants received epidural injections with corticosteroids (wrong control) |

|

Huston 2005 |

All participants received selective nerve root blocks (wrong control) |

|

Jang 2020 |

Letter to editor, and all participants received epidural injections with corticosteroids (wrong control) |

|

Kim 2018 |

All participants received epidural injections with corticosteroids (wrong control) |

|

Park 2019 |

Interlaminar epidural steroid injections versus selective nerve root block (Jan: selective nerve root block is geen usual care, zelfs soms gelijk aan epidurale corticosteroïden injectie, en chronische populatie (wrong control, wrong participants) |

|

Boswell 2003 |

SR, maar op Stav (1993) na, geen relevante vergelijkende studies (wrong control, no recent review) |

|

Boswell 2005 |

SR, maar op Stav (1993) na, geen relevante vergelijkende studies (wrong control, no recent review) |

|

Diwan 2012 |

SR, maar op Stav (1993), Manchikanti (2010, 2012) na geen relevante vergelijkende studies (wrong control, no recent review) |

|

Conger 2012 |

SR, but only within group differences presented (wrong control) |

|

Binder 2008 |

SR, but only Persson 1997 en Castagnera1994 concerning radiculopathy, both no match for inclusion (wrong intervention, wrong control, old review) |

|

Engel 2014 |

SR, maar op Anderberg (2007) na geen relevante vergelijkende studies (wrong control, old review) |

|

Mesregah 2020 |

SR, maar includeerde 1 trial met patienten met radiculitis (Manchicanti 2012), verder alleen cervical central spinal stenosis, or patients without radiculitis (wrong population) |

|

Manchikanti 2015 |

SR, maar op Stav (1993) na, geen relevante vergelijkende studies (wrong control, wrong population) |

|

Bureau 2020 |

Outcome: Association between injectate dispersal patterns and clinical outcome (wrong outcome) |

|

Jee 2012 |

All participants received epidural injections with corticosteroids (wrong control) |

|

Manchikanti 2010 |

Preliminary results of Manchikanti (2012), less participants and no additional information |

|

Kaye 2015 |

SR, but only with outcomes for pain relief/function (Stav (1993) and Cohen (2014)). |

|

Alvin 2019 |

Observational comparative study (wrong study design) |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 01-07-2024

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodules is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de ‘samenstelling van de werkgroep’) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met een CRS.

WERKGROEP

- Mevr. dr. Carmen Vleggeert-Lankamp (voorzitter), neurochirurg, NVvN

- Dhr. dr. Ruben Dammers, neurochirurg, NVvN

- Mevr. drs. Martine van Bilsen, neurochirurg, NVvN

- Dhr. drs. Maarten Liedorp, neuroloog, NVN

- Mevr. drs. Germine Mochel, neuroloog, NVN

- Mevr. dr. Akkie Rood, orthopedisch chirurg, NOV

- Dhr. dr. Erik Thoomes, fysiotherapeut en manueel therapeut, KNGF/NVMT

- Dhr. prof. dr. Jan Van Zundert, hoogleraar Pijngeneeskunde, NVA

- Dhr. Leen Voogt, ervaringsdeskundige, Nederlandse Vereniging van Rugpatiënten ‘de Wervelkolom’

KLANKBORDGROEP

- Mevr. Elien Nijland, ergotherapeut/handtherapeut, EN

- Mevr. Meimei Yau, oefentherapeut, VvOCM

Met ondersteuning van:

- Mevr. dr. Charlotte Michels, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Mevr. drs. Beatrix Vogelaar, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Naam lid werkgroep |

Hoofdfunctie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Carmen Vleggeert-Lankamp (voorzitter) |

Neurochirurg, Leiden Universitair Medisch Centrum, Leiden

|

* Medisch Manager Neurochirurgie Spaarne Gasthuis, Hoofdorp/ Haarlem, gedetacheerd vanuit LUMC (betaald) * Boardmember Eurospine, chair research committee |

*Niet anders dan onderzoeksleider in projecten naar etiologie van en uitkomsten in het CRS. |

Geen actie |

|

Akkie Rood |

Orthopedisch chirurg, Sint Maartenskliniek, Nijmegen |

Lid NOV, DSS, NvA |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Erik Thoomes |

Fysio-Manueel therapeut / praktijkeigenaar, Fysio-Experts, Hazerswoude |

*Promovendus / wetenschappelijk onderzoeker Universiteit van Birmingham, UK,School of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation Sciences, |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Germine Mochel |

Neuroloog, DC klinieken (loondienst) |

Lid werkgroep pijn NVN Lid NHV en VNHC |

*Dienstverband bij DC klinieken, alwaar behandeling/diagnostiek patiënten CRS

|

Geen actie |

|

Jan Van Zundert |

*Anesthesioloog-pijnspecialist. |

Geen |

Geen financiering omtrent projecten die betrekking hebben op cervicaal radiculair lijden (17 jaar geleden op CRS onderwerk gepromoveerd, nadien geen PhD CRS-projecten begeleidt).

|

Geen actie |

|

Leen Voogt |

*Ervaringsdeskundige CRS. *Voorzitter Nederlandse Vereniging van Rugpatiënten 'de Wervelkolom' (NVVR) |

Vrijwilligerswerk voor de patiëntenvereniging (onbetaald). |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Maarten Liedorp |

Neuroloog in loondienst (0.6 fte), ZBC Kliniek Lange Voorhout, Rijswijk |

*lid oudergeleding MR IKC de Piramide (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Martine van Bilsen |

Neurochirurg, Radboudumc, Nijmegen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Ruben Dammers |

Neurochirurg, ErasmusMC, Rotterdam |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Naam lid klankbordgroep |

Hoofdfunctie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Meimei Yau |

Praktijkhouder Yau Oefentherapeut, Oefentherapeut Mensendieck, Den Haag. |

Geen |

Kennis opdoen, informatie/expertise uitwisselen met andere disciplines, oefentherapeut vertegenwoordigen. KP register |

Geen actie |

|

Vera Keil |

Radioloog, AmsterdamUMC, Amsterdam. Afgevaardigde NVvR Neurosectie |

Geen |

Als radioloog heb ik natuurlijk een interesse aan een sterke rol van de beeldvorming. |

Geen actie |

|

Elien Nijland |

Ergotherapeut/hand-ergotherapeut (totaal 27 uur) bij Treant zorggroep (Bethesda Hoogeveen) en Refaja ziekenhuis (Stadskanaal) |

Voorzitter Adviesraad Hand-ergotherapie (onbetaald) |

|

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door een afgevaardigde van de Nederlandse Vereniging van Rugpatiënten ‘de Wervelkolom’ te betrekken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen (zie kop ‘Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten’). De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Nederlandse Vereniging van Rugpatiënten ‘de Wervelkolom’ en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Corticosteroïd-injecties |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet en het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met CRS. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door Ergotherapie Nederland, het Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap, Nederlandse Vereniging van Ziekenhuizen, Nederlandse Vereniging van Revalidatieartsen, Vereniging van Oefentherapeuten Cesar en Mensendieck, Zorginstituut Nederland, Zelfstandige Klinieken Nederland, via enquête. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)