Chirurgische decompressie van de zenuwwortel

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van chirurgische decompressie van de zenuwwortel bij patiënten met CRS?

Aanbeveling

Start eerst met actieve conservatieve behandeling (denk bijvoorbeeld aan medicatie, fysiotherapie). Zet chirurgische behandeling niet als eerste keus in.

Behandel het cervicaal radiculair syndroom chirurgisch met congruente MRI-afwijking en wanneer conservatieve behandeling onvoldoende effect heeft, de patiënt dit weloverwogen wenst in samenspraak met de behandelend arts, afwegende de premorbide status en de mogelijke complicaties.

Overweeg sterk in een aantal situaties om vroegtijdig chirurgisch in te grijpen:

- Bij onhoudbare en niet te beïnvloeden pijn, en/of

- Bij progressieve motorische uitval.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Het doel van deze uitgangsvraag was om te achterhalen wat de waarde van chirurgische decompressie van de zenuwwortel was, in vergelijking met een conservatieve behandeling bij patiënten met CRS. In totaal zijn er drie publicaties van twee uitgevoerde RCTs gevonden die deze interventie vergeleken met conservatieve behandeling. De bewijskracht voor de kritieke uitkomstmaten (pijn, kwaliteit van leven en functioneren) was laag tot zeer laag. Dit betekent dat andere studies kunnen leiden tot nieuwe inzichten. De betrouwbaarheidsintervallen rondom de gevonden effecten waren breed (leidend tot onnauwkeurigheid) en geen van de studies maakte gebruik van blindering van de patiënten, artsen of onderzoekers (methodologische beperking). Daarom kunnen er op basis van de literatuur geen harde conclusies geformuleerd worden. De opzet van een gerandomiseerde studie zal ook in de toekomst lastig kunnen blijken. Patiënten met ernstige pijnklachten zullen niet willen randomiseren en a priori opteren voor chirurgie, wat de haalbaarheid beperkt.

Mogelijke voordelen chirurgie

De gevonden studies zijn dus niet optimaal opgezet en hier ligt een duidelijk kennishiaat. Daarbij dient ook opgemerkt te worden dat geïncludeerde patiënten vaak niet representatief zijn voor de klinische praktijk die zowel fysiek (bijvoorbeeld patiënten met obesitas) als mentaal (bijvoorbeeld patiënten met depressie) zwaarder belast is. Ook is het de vraag of de uitkomstmaten gebruikt in de studies het effect van operatie goed weergeven (Jack, 2022).

Om het effect van operatie te beoordelen wordt daarom ook de klinische ervaring van de werkgroep en prospectieve cohortstudies (Sampath, 1999; Butterman, 2018; Hermansen, 2011) meegenomen. In lijn met de gerandomiseerde studies is het te verwachten effect van een operatie dat op de korte termijn (eerste maanden) zowel de arm- als nekklachten afnemen. Of er effecten zijn -gunstig of ongunstig- op de lange termijn is onzeker. De patiënttevredenheid na operatie is hoog (66-95%) (Wichmann 2021, Butterman 2018) en is duidelijk hoger als de klachten relatief kort (<3 maanden) bestaan. Het lijkt daarbij niet uit te maken of er sprake is van een hernia van de discus of een degeneratieve foraminale stenose (Butterman, 2018).

De discrepantie tussen de uitstekende resultaten van cohortstudies en de onzekere resultaten uit de gerandomiseerde studies wordt waarschijnlijk mede verklaard door het gunstige spontane beloop, analoog aan het lumbosacrale radiculaire syndroom. De rationale rondom de keuze wel of niet opereren komt dan neer op optimale timing, wat beschouwd dient te worden als expert opinion (zie submodule ‘Timing’).

Mogelijke nadelen chirurgie

Een direct nadeel van een operatie blijkt niet uit de gevonden studies ten opzichte van een conservatief beleid. Operatie gaat gepaard met een risico van ongeveer 19% op complicaties (Fountas, 2007). De meest voorkomende complicaties zijn: slikklachten (10-31%), heesheid door letsel ipsilaterale nervus recurrens (3-29%), wondinfectie (<1-5%), hematoom (<1-2%) en duralek tijdens operatie (0.5-4%) (Fountas, 2007; Wichmann, 2021). Het risico op complicaties is hetzelfde ongeacht de techniek of benadering (anterior/posterior) (Fang, 2020).

Een te verwachten complicatie is een parese van de armspieren gerelateerd aan de aangedane zenuwwortel. Toch wordt dit maar in 1 studie bij 1% gemeld als naar alle complicaties wordt gekeken (Wichmann, 2021). Vermeldenswaardig is nog een tijdelijke uitval van C5 spieren, welke enkele dagen na de operatie vaker wordt gezien na chirurgie, waarbij een incidentie van 1.5-6% na een anterieure benadering wordt genoemd (Takase, 2020). De etiologie hiervan is onduidelijk, mogelijk speelt mee dat de C5 wortel het kortst is en daardoor gevoelig voor schade door rek. Redelijk herstel treedt op bij de meerderheid. (Houten, 2020)

Op de langere termijn is pseudoartrose een risico met een incidentie van 2.6% als alle soorten ingrepen worden meegenomen. Dit risico heeft een incidentie van 3.7% bij 1-niveau ACD (Schryver, 2015). Definities verschillen echter, waardoor het klinisch belang onduidelijk blijft. Hetzelfde geldt voor adjacent level disease, dat bij 2-4% per jaar wordt gezien, maar veel minder vaak leidt tot een nieuwe operatie. Aangezien de incidentie hoger is na een 2-niveau fusie in vergelijking met een 1-niveau fusie, is het aan te bevelen de operatie te beperken tot het symptomatische niveau (Epstein, 2022)

Roken geeft niet alleen een hogere kans op complicaties, maar ook op post-operatieve nekpijn (Zheng, 2022). Als de ingreep electief is, is het aan te bevelen de patiënt eerst te laten stoppen met roken alvorens te opereren. De termijn tussen datum stop roken en datum van opereren is onderwerp van discussie; een minimum van 2 weken lijkt al effect te hebben op peri-operatieve complicaties.

Een verhoogde BMI>30 kg/m2 geeft een verhoogde kans op complicaties, vooral wondinfectie en veneuze trombose. (Jackson, 2016; Sebastian, 2016) Als de ingreep electief is, is het te overwegen patiënt eerst te laten afvallen. Er zijn aanwijzingen dat het risico op complicaties dan weer daalt (Passias, 2018).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

De beslissing tot het al dan niet ondergaan van een operatie dient in samenspraak met de patiënt te worden genomen (shared decision making), waarbij de patiënt een goed inzicht dient te hebben in het beloop van de symptomen en de risico’s van de ingreep. Behalve de wens van de patiënt dient ook de premorbide toestand en co-morbiditeiten van patiënt te worden meegenomen in het advies van de arts. Ook de ernst van de pijn en het belang van een snelle terugkeer op de arbeidsmarkt, spelen in dit besluitvormingsproces een rol. Bij geringe pijnklachten heeft het voortzetten van de conservatieve behandeling de voorkeur.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

In Nederland worden jaarlijks gemiddeld 2000 patiënten met CRS geopereerd, wat resulteert in directe kosten van ongeveer €30 miljoen per jaar (van Geest, 2014). Hoewel de directe kosten voor conservatieve zorg lager zijn, kan deze groep mogelijk hogere indirecte kosten hebben als gevolg van een langere periode van verminderde arbeidsproductiviteit (van Geest, 2014). De MOVE-it trial start in 2024 om een economische evaluatie in Nederland te geven van chirurgie vergeleken met multimodale fysiotherapie. Er is elders gesuggereerd dat een ACDF-operatie kosteneffectief is zolang een cervicaal epiduraal blok niet bij 50% of meer een operatie voorkomt (Rhin, 2019).

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Gezien er geen studies zijn gedaan naar de aanvaardbaarheid en haalbaarheid van chirurgie vergeleken met conservatieve behandelingen voor patiënten met een CRS, is vervolgonderzoek hiernaar aangewezen.

De werkgroep is van mening dat er onenigheid in de klinische praktijk zou kunnen bestaan over de timing om tot een chirurgische behandeling over te gaan in geval van falen van de conservatieve behandeling. Hiervoor wordt verwezen naar submodule ‘Timing’. Overigens zal er door het verwijspatroon in de Nederlandse setting zelden een onnodig vroege verwijzing naar een neurochirurg of orthopeed worden gedaan.

Voorts is de werkgroep van mening dat er geen belemmerende factoren zijn op het gebied van implementatie van de chirurgische interventie. De chirurgische behandeling van patiënten met CRS is verzekerde zorg. Voorts is de chirurgische behandeling voldoende ingebed in de moderne neurochirurgische en orthopedische praktijk.

Bij patiënten met risicofactoren adviseert de werkgroep om voorzorgsmaatregelen te nemen voor zover mogelijk. Adviseer rokers om dit minimaal twee weken voor de operatie te staken en adviseer patiënten met overgewicht om gewichtsreductie na te streven. Overigens is het resultaat van de operatie niet direct afhankelijk van het gewicht, maar wel het optreden van mogelijke complicaties. Patiënten met onderliggende psychopathologie, zoals een depressie, kennen een minder effect van chirurgische behandeling en dienen hierover te worden geconsulteerd.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Op basis van de beschikbare literatuur kan de werkgroep geen sterke aanbevelingen formuleren ten aanzien van de effectiviteit van de chirurgische behandeling van een CRS vergeleken met conservatieve behandelmodaliteiten. Een chirurgische behandeling in het algemeen lijkt te resulteren in een sneller herstel van de pijnklachten in vergelijking met conservatieve behandeling. Dit effect wordt echter op de langere termijn niet bevestigd. Het is de mening van de werkgroep een chirurgische behandeling te overwegen bij patiënten met een CRS waarbij een conservatieve behandeling niet leidt tot herstel van de klachten. Ten aanzien van de timing wordt verwezen naar submodule ‘Timing’.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Een operatie is de standaardbehandeling bij patiënten met CRS wanneer pijn en/of uitval van gevoel en/of kracht in de arm aanhouden met congruente MRI-afwijking. Vaak kent een CRS echter een voorspoedig spontaan herstel (Lyer, 2016). Over het algemeen vindt men dat alleen tot operatieve therapie moet worden overgegaan als conservatief beleid gefaald heeft. Een operatie kan gepaard gaan met complicaties en hoge kosten. Op dit moment is het onduidelijk of CRS beter te behandelen is door middel van chirurgische decompressie van de zenuwwortel of door middel van niet opereren in het algemeen. Wat levert een operatie precies op voor een patiënt en hoe staat dit in verhouding tot complicaties en kosten? Deze module gaat in op de effectiviteit van chirurgische behandeling. Omtrent de timing van chirurgische interventie verwijst de werkroep naar de submodule ‘Timing’.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1.1. Pain (short-, mid- and long term) (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of surgery with or without physiotherapy on pain (any term) compared with physiotherapy alone in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Sources: Enquist 2013; Enquist, 2017; Persson, 1997 |

1.2 Quality of life (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of surgery with physiotherapy on quality of life compared with physiotherapy alone in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Sources: Enquist 2017 |

1.3 Functioning (short-, mid- and long term) (critical)

|

Low GRADE |

Surgery with physiotherapy may increase functioning (any term) when compared with physiotherapy alone in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Sources: Enquist, 2013; Enquist, 2017 |

1.4 Patient satisfaction (short-, mid- and long term) (important)

|

Low GRADE |

Surgery with physiotherapy may increase patient satisfaction (any term) when compared with physiotherapy alone in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Sources: Enquist, 2013; Enquist, 2017 |

1.5 Complications (important)

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of surgery with physiotherapy on complications compared with physiotherapy alone in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Sources: Enquist, 2013; Enquist, 2017 |

1.6 Re-operation; 1.7 Return to work, tingling, and adjacent segment disease

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of surgery on return to work, tingling, re-operation or adjacent segment disease, compared with conservative management in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Sources: - |

2.1 Pain (short-, mid- and long term) (critical)

|

Low GRADE |

Surgery may decrease pain on the short term, but may result in little to no difference in pain after one year, when compared with a cervical collar in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Sources: Persson, 1997 |

Quality of life, functioning, patient satisfaction, complications, return to work, tingling, re-operation, and adjacent segment disease

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of surgery on return to work, tingling, re-operation or adjacent segment disease, compared with a cervical collar in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

Sources: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

In the RCT by Enquist (2013), anterior cervical decompression and fusion (ACDF) was combined with a physiotherapy programme after surgery and compared with the same physiotherapy programme alone. Participants were included when they reported pain in one or both arms, had a symptom duration of 8 weeks to 5 years, had one or two symptomatic disc levels and where of working age (18-65 years). Participants with obvious or slight signs of myelopathy were excluded, as were participants with a history of neck distortion, participants in need for other types of surgery, patients with malignancies/inflammatory joint disease/psychiatric disorders, and patients with a concurrent work-disabling disease. Participants were randomized in a surgical group receiving surgery and after 3 months physiotherapy (n=31) or a non-surgical group receiving physiotherapy only (n=32). Outcomes were measured 6-, 12- and 24-months post-intervention.

In the study by Enquist (2017), the 5- and 8-years results from the RCT of Enquist (2013) were presented.

In the RCT by Persson (1997), ACDF was compared with a cervical collar and with a physiotherapy program. Potential participants reported cervico-brachial pain for more than three months and were referred to an out-patient clinic in Lund for consideration of surgical treatment. Inclusion criteria were clinical and radiological signs indicating nerve root compression without spinal cord compression. Patients with whiplash, other traumatic injuries, and serious associated somatic/psychiatric diseases were excluded from participating. Participants were randomized in a surgical group receiving surgery (n=27), a group receiving physiotherapy (n= 27) and a group wearing a cervical collar (n=27). Outcomes were measured 4- and 16-months post-intervention.

Table 1. Description of included studies

|

Study |

Intervention |

Comparator |

Follow-up |

Outcomes |

||

|

Characteristics |

Intervention type |

Characteristics |

Type of control group |

|||

|

Enquist, 2013; Enquist, 2017

|

Mean age (SD): 49 (8) Female (%): 17 (55) Duration of pain, months (SD):

Affected level: C5-6 (n=12(39%)), C6-7 (n=13(42%))

|

Surgery with physiotherapy (31)

Anterior cervical decompression and fusion (one level n=27, 2 level with anterior plate n=4). Three months post-surgery the same physiotherapy program was initiated as provided in the control group. |

Mean age (SD): 44 (9) Female (%): 13 (41) Duration of pain, months (SD):

Affected level: C5-6 (n=14(44%), C6-7 (n=11(34%)) |

Physiotherapy (n= 32)

Individualized physiotherapy program consisting of neck-specific exercises and procedures for pain relief, general exercises, and pain coping, increasing self-efficacy and stress management strategies. |

6 months, 12 months, 24 months |

Functioning (NDI), arm pain (VAS -100), reoperations, complications |

|

Persson (1997)

|

Mean age (SD): 40 (8.5) Female (%): 11 (41) Duration of pain, months (SD): 34 (34.8) Affected level: C5-6 (n=13(48%)), C6-7(n=10(37%))

|

Surgery (n= 27)

Anterior cervical discectomy, using a bone graft from purified cow bone for fusion (one level,n= 26). Laminectomy by a posterior approach technique (n=1) |

Mean age (SD): 48 (8.1) Female (%):16 (59) Duration of pain, months (SD): 40 (32.5) Affected level: C5-6 (n=12(44%)), C6-7 (n=10(10%)) |

Physiotherapy (n= 27)

15 sessions of 40-45 minutes physiotherapy, for 3 months. |

4 months, 16 months |

Pain (VAS 0-100) |

|

Mean age (SD): 49 (8.5) Female (%): 10 (37) Duration of pain, months (SD): 28 (24.3) Affected level: C5-6 (n=15(56%)), C6-7 (n=10(37%)) |

Cervical collar (n= 27)

Either a rigid or soft collar. After randomization. |

|||||

MSQ, Medication Quantitative Scale; NDI, Neck Disability Index; NRS, Numeric Rating Scale; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale

Results

1. Surgery with physiotherapy vs. physiotherapy alone; and surgery vs. physiotherapy

1.1 Arm-pain (critical)

Three studies reported on pain (Enquist, 2013; Enquist, 2017; Persson, 1997). Results are presented in three post-intervention terms: 1.1.1 Short term: until 6 months), 1.1.2. Midterm: >6 months to 12 months, 1.1.3. long term: >12 months to 8 years. In the study by Persson (1997), type of pain (neck- and/or arm-pain) was not otherwise specified. A brief overview of the main characteristics is provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Overview on post-intervention terms

|

Study |

Follow-up |

Term |

Scale |

|

Enquist, 2013 |

6 months, 12 months, 24 months |

Short term, midterm, long term |

Arm pain (VAS-scale, 0-100) |

|

Enquist, 2017 |

5-8 years |

Long term |

Arm pain (VAS-scale, 0-100) |

|

Persson, 1997 |

4 months, 16 months |

Short term, midterm |

Pain (VAS-scale, 0-100) |

NRS: Numeric rating scale; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale

1.1.1 Short term (post treatment: up to 6 months)

Two studies reported on pain up to six months (Enquist, 2013; Persson, 1997).

• Arm pain (surgery with physiotherapy versus physiotherapy alone)

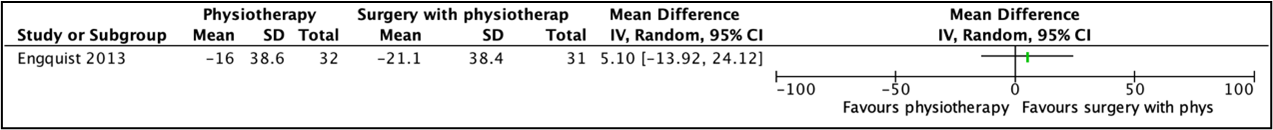

Enquist (2013) reported results for arm pain reduction using a VAS-scale ranging from 0-100mm. Six months after initiation of the intervention, mean reduction (within group mean change from baseline) was 21.1 (SD 38.4) in the group receiving surgery with physiotherapy and 16.0 (SD 38.6) in the group receiving only physiotherapy. This resulted in a mean difference of 5.1 (95%CI -13.9 to 24.1). Results are depicted in Figure 1.

• Pain (surgery versus physiotherapy)

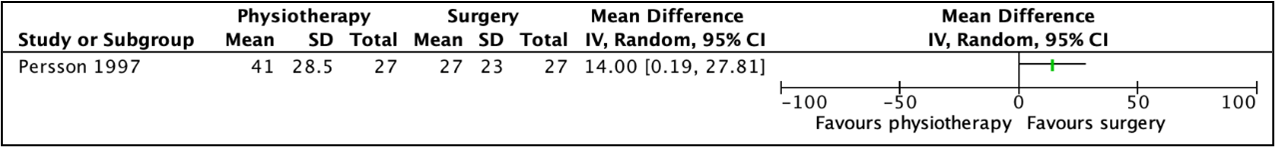

Persson (1997) reported results for mean current pain intensity using a VAS-scale ranging from 0-100mm. Four months after intervention, mean score was 27.0 (SD 23.0) in the group receiving surgery and 41.0 (SD 28.5) in the group receiving physiotherapy. This resulted in a mean difference of 14.00 (95%CI -0.19 to -27.81). Results are depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Mean reduction for armpain, surgery with physiotherapy versus physiotherapy alone (short term follow-up)

Figure 2. Mean differences for (arm-) pain, surgery versus physiotherapy (short term follow-up)

1.1.2 Midterm (post-treatment >6 months to 12 months)

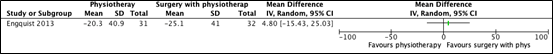

Two studies reported on pain after 6 months to 12 months (Enquist, 2013; Persson, 1997).

• Arm pain (Surgery with physiotherapy versus physiotherapy alone)

In the study by Enquist (2013), twelve months after initiation of the intervention, mean reduction was 25.1 (SD 40.9) in the group receiving surgery with physiotherapy and 20.3 (SD 41.0) in the group receiving only physiotherapy. This resulted in a mean difference of 4.80 (95%CI -15.43 to 25.03). Results are depicted in Figure 3.

• Pain (surgery versus physiotherapy)

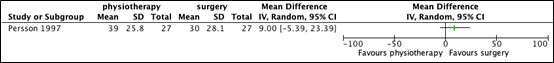

In the study by Persson (1997), sixteen months after initiation of the intervention, mean score was 30 (SD 28.1) in the group receiving surgery and 39 (SD 25.8) in the group receiving physiotherapy. This resulted in a mean difference of 9.00 (95%CI -5.39 to 23.39). Results are depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 3. Mean difference for arm-pain reduction, surgery with physiotherapy versus physiotherapy alone (mid-term follow-up)

Figure 3. Mean difference for arm-pain reduction, surgery with physiotherapy versus physiotherapy alone (mid-term follow-up)

Figure 4. Mean difference for pain, surgery versus physiotherapy (midterm follow-up)

1.1.3 Long term (>12 months to 8 years)

Two studies reported on arm-pain after 6 months to 12 months (Enquist, 2013; Enquist, 2017). Results are depicted in Figure 5.

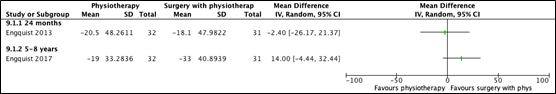

- Arm pain (surgery with physiotherapy versus physiotherapy alone)At 24 months after intervention (Enquist, 2013), mean reduction of arm-pain was 18.1 (SD 48.0) in the group receiving surgery with physiotherapy and 20.5 (SD 48.3) in the group receiving physiotherapy only. This resulted in a mean difference of -2.40 (95%CI -26.17 to 21.37).

At 5-8 years after intervention (Enquist, 2017), mean reduction of arm pain was 33.0 (SD 40.9) in the group receiving surgery with physiotherapy and 19.0 (SD 33.3) in the group receiving physiotherapy only. This resulted in a mean difference of 14.00 (95%CI -4.44 to 32.44). Results are depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Mean difference for arm-pain, surgery with physiotherapy versus physiotherapy alone (long term follow-up)

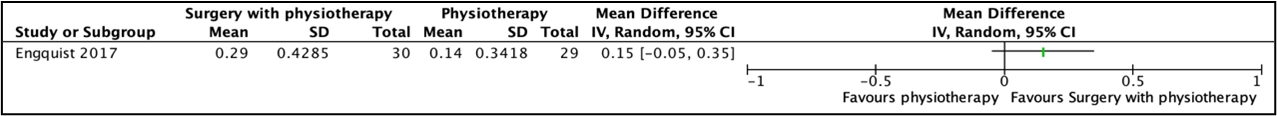

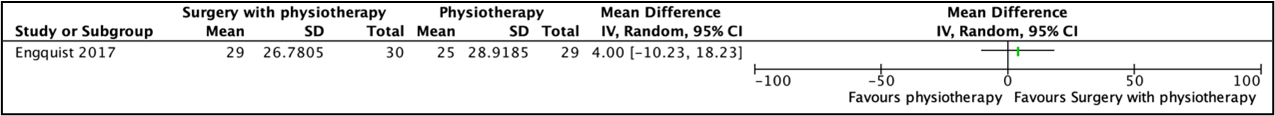

1.2 Quality of life (critical)

One study reported on quality of life (Enquist, 2017). Quality of life was measured using both the EQ-5D (0-1) and the EQ-VAS (0-100), with higher scores indicating better quality of life.

Five to eight years after intervention, mean score increased on the EQ-5D was 0.29 (SD 0.43) in the group receiving surgery with physiotherapy and 0.14 (SD 0.34) in the group receiving physiotherapy alone. This resulted in a mean difference of -0.15 (95%CI -0.05 to 0.35). Results are depicted in Figure 6.

Five to eight years after intervention, mean score on the EQ-VAS was 29 (SD 26.8) in the group receiving surgery with physiotherapy and 30 (SD 28.9) in the group receiving physiotherapy alone. This resulted in a mean difference of 4.00 (95%CI -10.23 to 18.23). Results are depicted in Figure 7.

Figure 6. Mean difference for quality of life (EQ-5D), surgery with physiotherapy versus physiotherapy alone

Figure 7. Mean difference for quality of life (EQ-VAS), surgery with physiotherapy versus physiotherapy alone

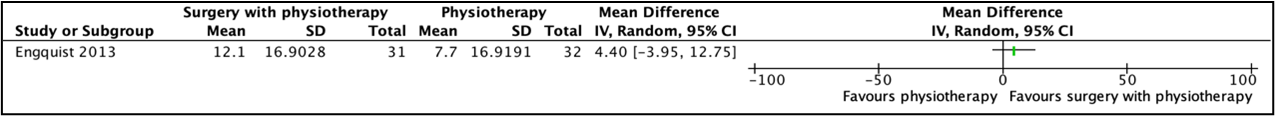

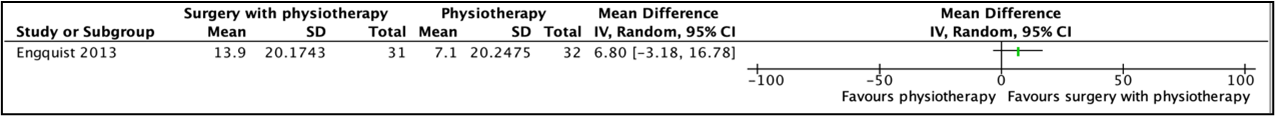

1.3 Functioning (critical)

Two studies reported on functioning (Enquist, 2013; Enquist, 2017). Functioning was measured using the Neck Disability Index (0-50), with higher scores indicating worse disability. A percentage of the reduction on the NDI was provided (0-100).

• 1.3.1 Short term (post treatment: up to 6 months)

One study reported on functioning up to six months (Enquist, 2013). Six months after initiation of the intervention, mean reduction was 12.1% (SD 16.9) in the group receiving surgery with physiotherapy and 7.7% (SD 16.9) in the group receiving only physiotherapy. This resulted in a mean difference of 4.40 (95%CI -3.95 to 12.75). Results are depicted in Figure 8.

• 1.3.2 Midterm (post-treatment >6 months up to 12 months)

One study reported on functioning after 6 months to 12 months (Enquist, 2013).

Twelve months after initiation of the intervention, mean reduction was 13.9% (SD 20.2) in the group receiving surgery with physiotherapy and 7.1% (SD 20.2) in the group receiving only physiotherapy. This resulted in a mean difference of 6.80 (95%CI -3.18 to 16.78). Results are depicted in Figure 9.

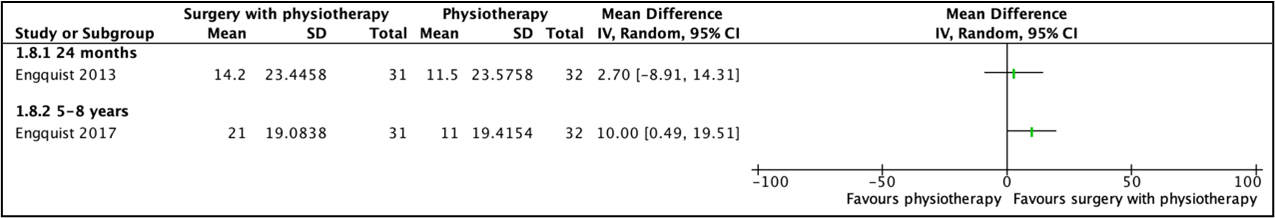

• 1.3.3 Long term (>12 months to 8 years)

In the study by Enquist (2013), 24 months after intervention, mean score was 14.2 (SD 23.4) in the group receiving surgery with physiotherapy and 11.5 (SD 23.6) in the group with physiotherapy alone. This resulted in a mean difference of 2.7 (95%CI -8.91 to 14.31).

In the study by Enquist (2017), 5-8 years after intervention, mean reduction was 21.0% (SD 19.1) in the group receiving surgery with physiotherapy and 11.0% (SD 19.4) in the group with physiotherapy alone. This resulted in a mean difference of 10.00 (95%CI 0.49 to 19.5). This difference was clinically relevant. Results are depicted in Figure 10.

Figure 8. Mean difference for functioning (NDI), surgery with physiotherapy versus physiotherapy alone (short term follow-up)

Figure 9. Mean difference for functioning (NDI), surgery with physiotherapy versus physiotherapy alone (midterm follow-up)

Figure 10. Mean difference for functioning (NDI), surgery with physiotherapy versus physiotherapy alone (long term follow-up)

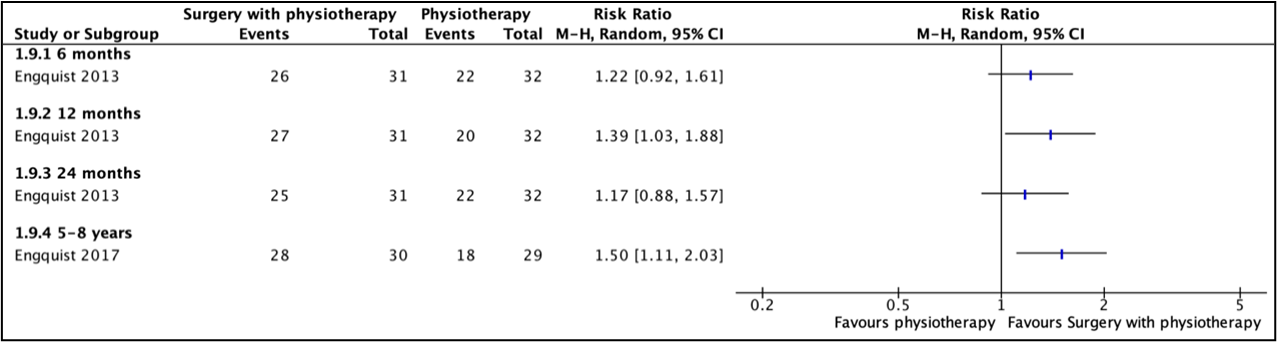

1.4 Patient satisfaction (important)

In the study by Enquist (2013) and Enquist (2017), patient satisfaction was measured using the Patient’s Global Assessment. Patients were asked whether after treatment, their neck/arm problems were much better, better, unchanged, worse or much worse. This score was dichotomised into better (defined by “better” or “much better”) and worse. Results are depicted in Table 3 and Figure 11.

Figure 11. Risk ratios for a better score on the Patient’s Global Assessment, surgery with physiotherapy versus physiotherapy alone

1.5 Complications (important)

One study reported on complications (Engquist, 2013). No surgery related complications (e.g. onset of neurological deficit, thromboembolism, unexpected bleeding, infection) were reported. These results could not be evaluated using the GRADE-methodology.

1.6 Re-operations (important)

Enquist 2013 reported no re-operations. After 5-8 years (Enquist, 2017), no participants from the surgery group needed another operation. In the non-surgery group, 8 participants underwent surgery.

1.7 Return to work, tingling, re-operation and adjacent segment level disease (important)

None of the RCTs assessed the effect of surgery on these outcomes in patients with cervical radiculopathy.

1. Level of evidence of the literature

1.1 Arm-pain (critical)

• Short term (post treatment: up to 6 months)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain (short term) started as high because it was based on RCTs and was downgraded by three levels to very low because lack of blinding in all studies (-1, risk of bias), and crossing of both thresholds of clinical decision-making (Enquist, 2013) (-2, imprecision).

• Midterm (post-treatment >6 months to 12 months)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain (midterm) started as high because it was based on RCTs and was downgraded by three levels to very low because lack of blinding in all studies (-1, risk of bias), and crossing of both thresholds of clinical decision-making (Enquist, 2013) (-2, imprecision).

• Long term (>12 months to 8 years)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain (long term) started as high because it was based on RCTs and was downgraded by three levels to very low because lack of blinding in all studies (-1, risk of bias), and crossing of both thresholds of clinical decision-making (Enquist, 2013) (-2, imprecision).

1.2 Quality of life (critical)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life started as high because it was based on RCTs and was downgraded by three levels to very low because lack of blinding in all studies (-1, risk of bias), and crossing of both thresholds of clinical decision-making (-2, imprecision).

1.3 Functioning (critical)

• 1.3.1 Short term (post treatment: up to 6 months)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure functioning (short term) started as high because it was based on RCTs and was downgraded by two levels to low because lack of blinding (Enquist, 2013) (-1, risk of bias), and crossing of one threshold of clinical decision-making (-1, imprecision).

• 1.3.2 Midterm (post-treatment >6 months to 12 months)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure functioning (midterm) started as high because it was based on RCTs and was downgraded by two levels to low because lack of blinding (Enquist, 2013) (-1, risk of bias), and crossing of one threshold of clinical decision-making (-1, imprecision).

• 1.3.3 Long term (>12 months to 8 years)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure functioning (long term) started as high because it was based on RCTs and was downgraded by two levels to low because lack of blinding in all studies (-1, risk of bias), and crossing of one threshold of clinical decision-making (Enquist, 2013) (-1, imprecision).

1.4 Patient satisfaction (important)

• 1.4.1 Short term (post treatment: up to 6 months)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure patient satisfaction (short term) started as high because it was based on RCTs and was downgraded by two levels to low because lack of blinding in all studies (-1, risk of bias), and crossing of one threshold of clinical decision-making (Enquist, 2013) (-1, imprecision).

• 1.4.2 Midterm (post-treatment >6 months to 12 months)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure patient satisfaction (midterm) started as high because it was based on RCTs and was downgraded by two levels to low because lack of blinding in all studies (-1, risk of bias), and crossing of one threshold of clinical decision-making (Enquist, 2013) (-1, imprecision).

• 1.4.3 Long term (>12 months to 8 years)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure patient satisfaction (long term) started as high because it was based on RCTs and was downgraded by three levels to very low because lack of blinding in all studies (-1, risk of bias), and crossing of both thresholds of clinical decision-making (Enquist, 2013) (-2, imprecision).

1.5 Complications (important)

The level of evidence of the outcome measure complications could not be GRADED due to a lack of data.

1.6 Re-operations (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure complications started as high because it was based on RCTs and was downgraded by three levels to very low because lack of blinding in all studies (-1, risk of bias), and very few events (Enquist, 2013) (-2, imprecision).

1.7 Return to work, tingling, re-operation and adjacent segment level disease (important)

The level of evidence regarding these outcomes was not graded because of lack of data.

2. Surgery vs. cervical collar

2.1 Arm-pain (critical)

One study reported on current pain (Persson, 1997) using a VAS-scale ranging from 0-100mm. Type of pain (neck- and/or arm-pain) was not otherwise specified by the authors.

• 2.1.1 Short term (post treatment: up to 6 months)

Four months after intervention, mean score was 27.0 (SD 23.0) in the group receiving surgery and 48.0 (SD 23.2) in the group wearing a cervical collar. This resulted in a mean difference of -21.00 (95%CI -33.34 to -8.68). This difference was clinically relevant. Results are depicted in Figure 12.

• 2.1.2. Long term (>12 months to 8 years)

Sixteen months after intervention, mean score was 30.0 (SD 28.1) in the group receiving surgery and 35.0 (SD 23.6) in the group wearing a cervical collar. This resulted in a mean difference of -5.00 (95%CI -18.8 to 8.84). This difference was not clinically relevant. Results are depicted in Figure 13.

Figure 12. Mean difference for pain, surgery versus cervical color (short term follow-up)

Figure 13. Mean difference for pain, surgery versus cervical collar (midterm follow-up)

Quality of life, functioning, patient satisfaction, complications, return to work, tingling, re-operation, and adjacent segment disease

The level of evidence regarding these outcomes was not graded because of lack of data.

2. Level of evidence of the literature

2.1 Pain (critical)

• Short term (post treatment: up to 6 months)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain (short term) started as high because it was based on RCTs and was downgraded by two levels to low because lack of blinding in all studies (-1, risk of bias), and crossing of both thresholds of clinical decision-making (Persson, 1997) (-1, imprecision).

• Midterm (post-treatment >6 months to 12 months)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain (midterm) started as high because it was based on RCTs and was downgraded by two levels to low because lack of blinding in all studies (-1, risk of bias), and crossing of both thresholds of clinical decision-making (Persson, 1997) (-1, imprecision).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the efficacy of surgical anterior decompression compared to conservative management in patients with cervical radiculopathy?

P: Patients with cervical radiculopathy

I: Surgical decompression of the nerve root (anterior microforaminotomy, ACD, ACDF, ACDP)

C: Conservative treatment (e.g. physiotherapy, cervical collar, PRF, corticosteroids);

O: Patient satisfaction, arm-pain, quality of life, return to work, tingling, functioning, complications, re-operation, adjacent segment level disease

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered arm-pain, quality of life and functioning as critical outcome measures for decision making; and patient satisfaction, return to work, tingling, complications, re-operation, and adjacent segment level disease as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

- Pain: VAS

- Functioning: Neck Disability Index (NDI)

- Quality of life: SF-36 or 1-10 scale

A priori, the working group did not define other outcome measures but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined a 10% difference for both continuous outcome measures and dichotomous outcome measures informing on relative risk (RR ≤ 0.91 and ≥ 1.10) as minimal clinically (patient) important differences. This decision was based on the minimal important change scores described in the article by Ostelo (2008), in accordance with the Dutch Lumbosacral Radicular syndrome guideline (NVN, 2020).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from inception until 25 April 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 582 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic review (searched in at least two databases, and detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment and results of individual studies available), randomized controlled trial comparing surgical decompression of the nerve root with conservative management;

- Patients aged ≥ 18 years;

- Full-text English language publication;

- Studies including ≥ 20 patients (ten in each study arm); and

- Studies according to PICO.

Initially, 29 studies were selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 26 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and three studies were included.

Results

Three studies were included in the analysis of the literature. A comprehensive overview of study characteristics is depicted in Table 1. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence table. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias table.

Referenties

- Buttermann GR. Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion Outcomes over 10 Years: A Prospective Study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2018 Feb 1;43(3):207-214. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002273. PMID: 28604488.

- Epstein NE, Agulnick MA. Short Review/Perspective on Adjacent Segment Disease (ASD) Following Cervical Fusion Versus Arthroplasty. Surg Neurol Int. 2022 Jul 22;13:313. doi: 10.25259/SNI_541_2022. PMID: 35928322; PMCID: PMC9345126.

- Enquist M, Löfgren H, Öberg B, Holtz A, Peolsson A, Söderlund A, Vavruch L, Lind B. Surgery versus nonsurgical treatment of cervical radiculopathy: a prospective, randomized study comparing surgery plus physiotherapy with physiotherapy alone with a 2-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013 Sep 15;38(20):1715-22. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31829ff095. PMID: 23778373.

- Enquist M, Löfgren H, Öberg B, Holtz A, Peolsson A, Söderlund A, Vavruch L, Lind B. A 5- to 8-year randomized study on the treatment of cervical radiculopathy: anterior cervical decompression and fusion plus physiotherapy versus physiotherapy alone. J Neurosurg Spine. 2017 Jan;26(1):19-27. doi: 10.3171/2016.6.SPINE151427. Epub 2016 Aug 26. PMID: 27564856.

- van Geest S, Kuijper B, Oterdoom M, van den Hout W, Brand R, Stijnen T, Assendelft P, Koes B, Jacobs W, Peul W, Vleggeert-Lankamp C. CASINO: surgical or nonsurgical treatment for cervical radiculopathy, a randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014 Apr 14;15:129. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-129. PMID: 24731301; PMCID: PMC4012146.

- Fang W, Huang L, Feng F, Yang B, He L, Du G, Xie P, Chen Z. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion versus posterior cervical foraminotomy for the treatment of single-level unilateral cervical radiculopathy: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2020 Jun 1;15(1):202. doi: 10.1186/s13018-020-01723-5. PMID: 32487109; PMCID: PMC7268305.

- Fountas KN, Kapsalaki EZ, Nikolakakos LG, Smisson HF, Johnston KW, Grigorian AA, Lee GP, Robinson JS Jr. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion associated complications. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007 Oct 1;32(21):2310-7. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318154c57e. PMID: 17906571.

- Hermansen A, Hedlund R, Vavruch L, Peolsson A. A comparison between the carbon fiber cage and the cloward procedure in cervical spine surgery: a ten- to thirteen-year follow-up of a prospective randomized study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011 May 20;36(12):919-25. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e8e4a3. PMID: 21217436.

- Iyer S, Kim HJ. Cervical radiculopathy. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2016 Sep;9(3):272-80. doi: 10.1007/s12178-016-9349-4. PMID: 27250042; PMCID: PMC4958381.

- Jackson KL 2nd, Devine JG. The Effects of Obesity on Spine Surgery: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Global Spine J. 2016 Jun;6(4):394-400. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1570750. Epub 2016 Jan 15. PMID: 27190743; PMCID: PMC4868585.

- Jack AS, Hayman E, Pierre C, Ramey WL, Witiw CD, Oskouian RJ, Daniels AH, Pugley A, Hamilton K, Ames CP, Chapman JR, Ghogawala Z, Hart RA. Cervical Spine Research Society-Cervical Stiffness Disability Index (CSRS-CSDI): Validation of a Novel Scoring System Quantifying the Effect of Postarthrodesis Cervical Stiffness on Patient Quality of Life. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2022 Sep 15;47(18):1263-1269. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000004402. Epub 2022 Jul 1. PMID: 35797641.

- Persson LC, Moritz U, Brandt L, Carlsson CA. Cervical radiculopathy: pain, muscle weakness and sensory loss in patients with cervical radiculopathy treated with surgery, physiotherapy or cervical collar. A prospective, controlled study. Eur Spine J. 1997;6(4):256-66. doi: 10.1007/BF01322448. PMID: 9294750; PMCID: PMC3454639.

- Passias PG, Horn SR, Vasquez-Montes D, Shepard N, Segreto FA, Bortz CA, Poorman GW, Jalai CM, Wang C, Stekas N, Frangella NJ, Deflorimonte C, Diebo BG, Raad M, Vira S, Horowitz JA, Sciubba DM, Hassanzadeh H, Lafage R, Afthinos J, Lafage V. Prior bariatric surgery lowers complication rates following spine surgery in obese patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2018 Dec;160(12):2459-2465. doi: 10.1007/s00701-018-3722-6. Epub 2018 Nov 8. Erratum in: Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2019 Dec;161(12):2443-2446. PMID: 30406870.

- Rihn JA, Bhat S, Grauer J, Harrop J, Ghogawala Z, Vaccaro AR, Hilibrand AS. Economic and Outcomes Analysis of Recalcitrant Cervical Radiculopathy: Is Nonsurgical Management or Surgery More Cost-Effective? J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019 Jul 15;27(14):533-540. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00379. PMID: 3040797

- Sampath P, Bendebba M, Davis JD, Ducker T. Outcome in patients with cervical radiculopathy. Prospective, multicenter study with independent clinical review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999 Mar 15;24(6):591-7. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199903150-00021. PMID: 10101827.

- Sebastian AS, Currier BL, Clarke MJ, Larson D, Huddleston PM 3rd, Nassr A. Thromboembolic Disease after Cervical Spine Surgery: A Review of 5,405 Surgical Procedures and Matched Cohort Analysis. Global Spine J. 2016 Aug;6(5):465-71. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1569056. Epub 2015 Nov 26. PMID: 27433431; PMCID: PMC4947407.

- Shriver MF, Lewis DJ, Kshettry VR, Rosenbaum BP, Benzel EC, Mroz TE. Pseudoarthrosis rates in anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: a meta-analysis. Spine J. 2015 Sep 1;15(9):2016-27. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2015.05.010. Epub 2015 May 15. PMID: 25982430.

- Takase H, Tayama K, Nakamura Y, Regenhardt RW, Mathew J, Murata H, Yamamoto T. Anterior Cervical Decompression and C5 Palsy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Three Reconstructive Surgeries. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2020 Nov 15;45(22):1587-1597. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000003637. PMID: 32756281.

- Wichmann TO, Rasmussen MM, Einarsson HB. Predictors of patient satisfaction following anterior cervical discectomy and fusion for cervical radiculopathy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2021 Apr 16;205:106648. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2021.106648. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33901749.

- Zheng LM, Zhang ZW, Wang W, Li Y, Wen F. Relationship between smoking and postoperative complications of cervical spine surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2022 Jun 2;12(1):9172. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-13198-x. PMID: 35654928; PMCID: PMC9163175.

Evidence tabellen

Risk of bias table for intervention studies

|

Study reference

|

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

|

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

|

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented? Were patients blinded? Were healthcare providers blinded? Were data collectors blinded? Were outcome assessors blinded? Were data analysts blinded? |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

|

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

|

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

|

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH |

|

Enquist, 2013 |

Reason: Central randomization |

Reason: Sealed envelopes were used |

Reason: Study did not state blinding of patients, outcome assessors, healthcare providers, data analysts or collectors. |

Reason: Drop-outs after randomization (4 in surgery and 1 in physiotherapy). |

Reason: No trial protocol available. EQ-5D was not stated in methods, however measured in publication of Enquist (2017). |

Reason: no other problems noted |

HIGH (all measures) |

|

Enquist, 2017 |

Reason: Central randomization |

Reason: Sealed envelopes were used |

Reason: Study did not state blinding of patients, outcome assessors, healthcare providers, data analysts or collectors. |

Reason: Drop-outs after randomization (4 in surgery and 1 in physiotherapy). |

Reason: No trial protocol available. EQ-5D was not stated in methods of Enquist (2013), however measured in publication of Enquist (2017). |

Reason: no other problems noted |

HIGH (all measures) |

|

Persson, 1997 |

Reason: Randomization, not further stated |

Reason: Sealed envelopes were used |

Reason: Study did not state blinding of patients, outcome assessors, healthcare providers, data analysts or collectors. |

Reason: Drop-out was infrequent, at follow-up, one participant from the cervical collar group and one from the surgery group dropped out. |

Reason: No trial protocol available, aforementioned measurements were reported. |

Reason: no other problems noted |

HIGH (all measures) |

Table of excluded studies

|

Taso 2020 |

protocol (wrong publication type) |

|

Bhagawati 2015 |

no comparison between conservative and surgical (wrong study design) |

|

Bono 2011 |

guideline, 2011 mostly consensus based (wrong publication type) |

|

Carragee 2008 |

systematic search but less recent than used reviews |

|

Ellenberg 1994 |

non-systematic review (wrong study design) |

|

Joaquim 2016 |

narrative review of case series and observational research (wrong study design) |

|

van Geest 2014 |

study protocol (wrong publication type) |

|

Fouyas 2002 |

2001 version of Nicolaidis cochrane (outdated) |

|

Fouyas 2007 |

2006 version of Nicolaidis cochrane (outdated) |

|

Wang 2005 |

Atrikel niet leverbaar, search tot 2004 dus niet recenter dan andere reviews |

|

Gebremariam 2012 |

Only 1 matching RCT included (outdated) |

|

Matz 2009 |

no comparison between conservative and surgical (wrong study design) |

|

Bhagawati 2015 |

Refers to Matz2009 and Nikolaidis2010 for radiculopathy (outdated) |

|

Eichen 2014 |

no comparison between conservative and surgical (wrong study design) |

|

Enquist 2015 |

Prospective factors for effect in Enquist (2013) (wrong outcome) |

|

Fehlings 2009 |

Overview article (wrong study design) |

|

McCornick 2017 |

Two types of epidural steroid injections are compared (wrong intervention) |

|

Carragee 2008 |

Overview article (wrong study design) |

|

Zang 2015 |

Delphi article for Chinese clinical consensus (wrong publication type) |

|

Persson 1997b |

SIP and MACL compared with nonrandomized reference group (wrong outcome) |

|

Persson 1998 |

Shoulder mobility, neck mobility, muscle tenderness and correlation (wrong outcome) |

|

Persson 2001 |

Disability rating index only before treatment, coping correlations with pain and HADS and MACL for total group (wrong outcome) |

|

Luyao 2022 |

most recent systematic review, data-extraction, analysis and reporting unsufficient |

|

Manchikanti 2014 |

interlaminar versus transforaminal epidural injections (wrong intervention) |

|

Lenzi 2017 |

No measures of dispersion reported, no blinding (very low study quality) |

|

Peolsson 2013 |

No comparative measures were reported (wrong outcome) |

|

de Rooij 2020 |

percutaneous nucleoplasty versus anterior discectomy, no conservative treatment (wrong control) |

|

Nicolaidis 2010 |

Systematic review not containing Halim (2017) and Enquist (2013, 2017) |

|

Broekema 2020 |

Systematic review not containing Halim (2017) and Enquist (2017) |

|

Halim 2017 |

percutaneous nucleoplast as controlgroup (wrong control) |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 01-07-2024

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodules is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de ‘samenstelling van de werkgroep’) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met een CRS.

WERKGROEP

- Mevr. dr. Carmen Vleggeert-Lankamp (voorzitter), neurochirurg, NVvN

- Dhr. dr. Ruben Dammers, neurochirurg, NVvN

- Mevr. drs. Martine van Bilsen, neurochirurg, NVvN

- Dhr. drs. Maarten Liedorp, neuroloog, NVN

- Mevr. drs. Germine Mochel, neuroloog, NVN

- Mevr. dr. Akkie Rood, orthopedisch chirurg, NOV

- Dhr. dr. Erik Thoomes, fysiotherapeut en manueel therapeut, KNGF/NVMT

- Dhr. prof. dr. Jan Van Zundert, hoogleraar Pijngeneeskunde, NVA

- Dhr. Leen Voogt, ervaringsdeskundige, Nederlandse Vereniging van Rugpatiënten ‘de Wervelkolom’

KLANKBORDGROEP

- Mevr. Elien Nijland, ergotherapeut/handtherapeut, EN

- Mevr. Meimei Yau, oefentherapeut, VvOCM

Met ondersteuning van:

- Mevr. dr. Charlotte Michels, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Mevr. drs. Beatrix Vogelaar, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Naam lid werkgroep |

Hoofdfunctie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Carmen Vleggeert-Lankamp (voorzitter) |

Neurochirurg, Leiden Universitair Medisch Centrum, Leiden

|

* Medisch Manager Neurochirurgie Spaarne Gasthuis, Hoofdorp/ Haarlem, gedetacheerd vanuit LUMC (betaald) * Boardmember Eurospine, chair research committee |

*Niet anders dan onderzoeksleider in projecten naar etiologie van en uitkomsten in het CRS. |

Geen actie |

|

Akkie Rood |

Orthopedisch chirurg, Sint Maartenskliniek, Nijmegen |

Lid NOV, DSS, NvA |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Erik Thoomes |

Fysio-Manueel therapeut / praktijkeigenaar, Fysio-Experts, Hazerswoude |

*Promovendus / wetenschappelijk onderzoeker Universiteit van Birmingham, UK,School of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation Sciences, |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Germine Mochel |

Neuroloog, DC klinieken (loondienst) |

Lid werkgroep pijn NVN Lid NHV en VNHC |

*Dienstverband bij DC klinieken, alwaar behandeling/diagnostiek patiënten CRS

|

Geen actie |

|

Jan Van Zundert |

*Anesthesioloog-pijnspecialist. |

Geen |

Geen financiering omtrent projecten die betrekking hebben op cervicaal radiculair lijden (17 jaar geleden op CRS onderwerk gepromoveerd, nadien geen PhD CRS-projecten begeleidt).

|

Geen actie |

|

Leen Voogt |

*Ervaringsdeskundige CRS. *Voorzitter Nederlandse Vereniging van Rugpatiënten 'de Wervelkolom' (NVVR) |

Vrijwilligerswerk voor de patiëntenvereniging (onbetaald). |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Maarten Liedorp |

Neuroloog in loondienst (0.6 fte), ZBC Kliniek Lange Voorhout, Rijswijk |

*lid oudergeleding MR IKC de Piramide (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Martine van Bilsen |

Neurochirurg, Radboudumc, Nijmegen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Ruben Dammers |

Neurochirurg, ErasmusMC, Rotterdam |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Naam lid klankbordgroep |

Hoofdfunctie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Meimei Yau |

Praktijkhouder Yau Oefentherapeut, Oefentherapeut Mensendieck, Den Haag. |

Geen |

Kennis opdoen, informatie/expertise uitwisselen met andere disciplines, oefentherapeut vertegenwoordigen. KP register |

Geen actie |

|

Vera Keil |

Radioloog, AmsterdamUMC, Amsterdam. Afgevaardigde NVvR Neurosectie |

Geen |

Als radioloog heb ik natuurlijk een interesse aan een sterke rol van de beeldvorming. |

Geen actie |

|

Elien Nijland |

Ergotherapeut/hand-ergotherapeut (totaal 27 uur) bij Treant zorggroep (Bethesda Hoogeveen) en Refaja ziekenhuis (Stadskanaal) |

Voorzitter Adviesraad Hand-ergotherapie (onbetaald) |

|

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door een afgevaardigde van de Nederlandse Vereniging van Rugpatiënten ‘de Wervelkolom’ te betrekken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen (zie kop ‘Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten’). De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Nederlandse Vereniging van Rugpatiënten ‘de Wervelkolom’ en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Chirurgische decompressie van de zenuwwortel (chirurgisch versus conservatief) |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet en het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met CRS. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door Ergotherapie Nederland, het Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap, Nederlandse Vereniging van Ziekenhuizen, Nederlandse Vereniging van Revalidatieartsen, Vereniging van Oefentherapeuten Cesar en Mensendieck, Zorginstituut Nederland, Zelfstandige Klinieken Nederland, via enquête. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

NHG, 2018. NHG-Standaard Pijn (M106). Published: juni 2018. Laatste aanpassing: Laatste aanpassing: september 2023. Link: https://richtlijnen.nhg.org/standaarden/pijnhttps://richtlijnen.nhg.org/standaarden/pijn

NVN, 2020. Richtlijn Lumbosacraal Radiculair Syndroom (LRS). Beoordeeld: 21-09-2020. Link: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/lumbosacraal_radiculair_syndroom_lrs/startpagina_-_lrs.html

Radhakrishnan K, Litchy WJ, O'Fallon WM, Kurland LT. Epidemiology of cervical radiculopathy. A population-based study from Rochester, Minnesota, 1976 through 1990. Brain. 1994 Apr;117 ( Pt 2):325-35. doi: 10.1093/brain/117.2.325. PMID: 8186959.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.