Omgevingsfactoren van BPPD

Uitgangsvraag

Met welke factoren moet rekening worden gehouden bij de behandeling van BPPD?

Aanbeveling

Artsen dienen factoren die een verhoogd risico op vallen geven uit te vragen; dit beinvloedt de behandelkeus van BPPD (voorkeur voor niet-conservatieve behandeling).

Overwegingen

- Voordeel: Het behandelplan voor BPPD wordt patiënt-specifiek en patiënten met een verhoogd risico op vallen en valgerelateerde morbiditeit worden geïdentificeerd.

- Nadeel: geen

- Kosten: geen

- Rol van de voorkeur van de patiënt: minimaal

Onderbouwing

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Niveau 3 |

BPPD gaat veelal gepaard met comorbiditeit zoals diabetes, osteoporose en vasculaire problematiek. BPPD geeft een verhoogde kans op vallen en dit neemt toe bij comorbiditeit.

|

Samenvatting literatuur

Although BPPV arises from dysfunction of the vestibular end organ, patients with BPPV often concurrently suffer from comorbidities, limitations, and risks that may affect the diagnosis and treatment outcome of BPPV. Assessment of the patient with BPPV for factors that modify management is essential for improved treatment outcomes and ensuring patient safety with an underlying diagnosis of BPPV. The majority of factors that may modify management of BPPV can be identified if the clinician questions patients for these factors and elicits a detailed history (Rubenstein, et al., 2001).

Given that BPPV occurs most commonly in the second half of the lifespan and its prevalence increases with age, patients suffering from BPPV often have medical comorbidities that may alter the management of BPPV (Lawson, et al., 2005). In crossectional surveys, patients with BPPV demonstrate higher rates of diabetes, history of head trauma, and anxiety (Cohen, et al., 2004). Other studies have also found higher relative rates of migraine (34% in BPPV patients vs 10% in non-dizziness control group), history of stroke (10% in BPPV patients vs 1% in controls), diabetes (14% vs 5%), and hypertension (52% vs 22%) (von Brevern, et al., 2007). Clinicians should assess patients with BPPV for these comorbidities because their presence may modify management and influence treatment outcomes in BPPV.

One of the major concerns with BPPV and vertiginous syndromes in general is the risk for falls and resultant injury (Gazzola, et al., 2006). In multiple studies concerning etiology of falls, dizziness and vertigo were deemed the primary etiology for 13 percent of falls, compared with existing balance and gait problems (17%) and person-environment interactions (31%) (Rubenstein, et al., 2006). In a study by Oghalai,15.9 percent of patients referred to a geriatric clinic for general geriatric evaluation had undiagnosed BPPV, and three-fourths of those with BPPV had fallen within the 3 months prior to referral. Thus, evaluation of patients with a diagnosis of BPPV should also include an assessment of risk for falls (Lawson, et al., 2005). In particular, elderly patients will be more statistically at risk for falls with BPPV. Clinicians may use various fall assessment tools to determine the patient’s fall risk and appropriate precautionary recommendations (Rubenstein, et al., 2001).

As noted above, comorbid conditions that occur commonly with BPPV such as a history of stroke or diabetes should also be identified during evaluation of patients with BPPV. Patients with a history of stroke or a history of diabetes, particularly with peripheral neuropathy, may already have preexisting gait, balance, or proprioceptive deficit (Casellini, et al., 2007) (Richardson, et al., 2002) (Tilling, et al., 2006). The additional symptoms of BPPV may increase their risk for fall and injury. Patients with visual disturbances often lack the ability to correct for or compensate for a balance deficit with visual cues, and may also be at increased risk for falls. Associations between osteopenia and osteoporosis and BPPV have been reported (Vibert, et al., 2003). Patients with both osteoporosis and BPPV may be at greater risk for fractures resulting from falls related to BPPV; therefore, patients with combined osteoporosis and subsequent BPPV should be identified and monitored closely for fall and fracture risk. Examined from a different vantage point, patients with a history of recurrent falls, particularly among the elderly, should be assessed for underlying BPPV as one of the potential fall-precipitating diagnoses (Jonsson, et al., 2004).

BPPV may occur in the setting of other CNS disorders. Patients should be questioned as to the presence of preexisting CNS disorders that may modify the management of BPPV. BPPV may occur relatively commonly after trauma or traumatic brain injury (Katsarkas, et al., 1999) (Motin, et al., 2005). Posttraumatic BPPV is most likely to involve the posterior semicircular canal, and studies indicate that posttraumatic BPPV is significantly more likely to require repeated physical treatments (up to 67% of cases) for resolution compared with nontraumatic forms (14% of cases) (Gordon, et al., 2004). In rare instances, posttraumatic BPPV may be bilateral (Katsarkas, et al., 1999). Because posttraumatic BPPV may be more refractory and/or bilateral, thus requiring specialized treatment, a history of head trauma preceding a clinical diagnosis of BPPV should be elicited (Motin, et al., 2005). Although dizziness in the setting of multiple sclerosis may have a wide variety of etiologies, studies of acute vertigo occurring in multiple sclerosis report that a substantial number of patients may have BPPV with a positive Dix-Hallpike maneuver and successful response to a PRM (Frohman, et al., 2003) (Frohman, et al., 2000). This study suggests that patients with BPPV and an underlying CNS disorder may be successfully diagnosed and treated with conventional methods for BPPV.

Finally, in a small percentage of cases, refractory or persistent BPPV may create difficulties from a psychological and/or social-functional perspective for affected individuals (Gamiz, et al., 2004) (Lopez-Escamez, et al., 2005). Outcomes studies have shown that patients with BPPV exhibit a significant negative quality-of-life impact from the diagnosis compared with the normative population in multiple subscales of the Short Form-36 (Lopez-Escamez, et al., 2005) (Lopez-Escamez, et al., 2003). Patients who have preexisting comorbid conditions may require additional home supervision in the setting of BPPV (Whitney, et al., 2005). This supervision may include counseling about the risk of falling at home or a home safety assessment. In rare cases, patients disabled by BPPV-related vertigo, especially if chronic or refractory, may need home assistance or temporary nursing home placement for their safety.

Referenties

- Jönsson, R., Sixt, E., Landahl, S., et al. (2004). Prevalence of dizziness and vertigo in an urban elderly population. J Vestib Res, 14, 47-52.

- von Brevern, M., Radtke, A., Lezius, F., et al. (2007). Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a population based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 78, 710-5.

- Casellini, C.M., Vinik, A.I. (2007). Clinical manifestations and current treatment options for diabetic neuropathies. Endocr Pract, 13, 550-66.

- Cohen, H.S., Kimball, K.T., Stewart, M.G. (2004). Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and comorbid conditions. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec, 66, 11-5.

- Frohman, E.M., Kramer, P.D., Dewey, R.B., et al. (2003). Benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo in multiple sclerosis: diagnosis, pathophysiology and therapeutic techniques. Mult Scler, 9, 250-5.

- Frohman, E.M., Zhang, H., Dewey, R.B., et al. (2000). Vertigo in MS: utility of positional and particle repositioning maneuvers. Neurology, 55, 1566-9.

- Gamiz, M.J., Lopez-Escamez, J.A. (2004). Health-related quality of life in patients over sixty years old with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Gerontology, 50, 82-6.

- Gazzola, J.M., Gananca, F.F., Aratani, M.C., et al. (2006). Circumstances and consequences of falls in elderly people with vestibular disorder. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol (Engl Ed), 72, 388-92.

- Gordon, C.R., Levite, R., Joffe, V., et al. (2004). Is posttraumatic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo different from the idiopathic form?. Arch Neurol, 61, 1590-3.

- Katsarkas, A. (1999). Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV): idiopathic versus post-traumatic. Acta Otolaryngol, 119, 745-9.

- Lawson, J., Johnson, I., Bamiou, D.E., et al. (2005). Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: clinical characteristics of dizzy patients referred to a Falls and Syncope Unit. QJM, 98, 357-64.

- Lopez-Escamez, J.A., Gamiz, M.J., Fernandez-Perez, A., et al. (2005). Long-term outcome and health-related quality of life in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol, 262, 507-11.

- Motin, M., Keren, O., Groswasser, Z., et al. (2005). Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo as the cause of dizziness in patients after severe traumatic brain injury: diagnosis and treatment. Brain Inj, 19, 693-7.

- Richardson, J.K. (2002). Factors associated with falls in older patients with diffuse polyneuropathy. J Am Geriatr Soc, 50, 1767-73.

- Rubenstein, L.Z. (2006). Falls in older people: epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for prevention. Age Ageing, 35, 37-41.

- Rubenstein, L.Z., Powers, C.M., MacLean, C.H. (2001). Quality indicators for the management and prevention of falls and mobility problems in vulnerable elders. Ann Intern Med, 135, 686-93.

- Tilling, L.M., Darawil, K., Britton, M. (2006). Falls as a complication of diabetes mellitus in older people. J Diabetes Complications, 20, 158-62.

- Vibert, D., Kompis, M., Hausler, R. (2003). Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in older women may be related to osteoporosis and osteopenia. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, 112, 885-9.

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 20-08-2013

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-02-2020

De tekst van deze module is opgesteld tijdens de richtlijnontwikkeling in 2010 door de oorspronkelijke richtlijnwerkgroep (zie Samenstelling werkgroep). De module is opnieuw beoordeeld en nog actueel bevonden door de werkgroep samengesteld voor de richtlijnherziening in 2019 (zie samenstelling huidige werkgroep). Uiterlijk in 2024 bepaalt het bestuur van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Keel-Neus-Oorheelkunde en Heelkunde van het Hoofd-Halsgebied of de richtlijnmodule nog actueel is.

Algemene gegevens

Met ondersteuning van de Orde van Medisch Specialisten. De richtlijnontwikkeling werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De richtlijn betreft een adaptatie van:

Clinical practice guideline: Benigne Paroxysmale Positionele Duizeligheid.

De Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery foundation ‘Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’ (Bhattacharayya, et al., 2008) vormde het uitgangspunt van de onderhavige richtlijn. Daarnaast werd de Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of neurology, gericht op de behandeling van BPPD, gebruikt ter aanvulling (Fife, et al., 2008), alsmede de discussies en richtlijnen van de Standaardisatie commissie van de Barany Society (Reykjavik, et al., 2010, www.baranysociety.nl).

Doel en doelgroep

De primaire doelstellingen van deze richtlijn zijn:

- De kwaliteit van de zorg te verbeteren door middel van een accurate en snelle diagnose van BPPD.

- Voorkomen van onnodig gebruik van medicijnen.

- Doelgericht gebruik van aanvullend onderzoek.

- Stimuleren van het gebruik van repositiemanoeuvres als therapie voor BPPD.

Secundaire doelstellingen zijn: beperking van de kosten van diagnose en behandeling van BPPD, vermindering van het aantal artsenbezoeken, en verbetering van de kwaliteit van leven. Het grote aantal patiënten met BPPD en de verscheidenheid aan diagnostische en therapeutische interventies voor BPPD maakt dit een geschikt onderwerp voor een evidence-based richtlijn.

De Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery foundation ‘Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’ (Bhattacharayya, et al., 2008) vormde het uitgangspunt van de onderhavige richtlijn. Daarnaast werd de Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of neurology, gericht op de behandeling van BPPD, gebruikt ter aanvulling (Fife, et al., 2008), alsmede de discussies en richtlijnen van de Standaardisatie commissie van de Barany Society (Reykjavik, et al., 2010, www.baranysociety.nl)). Onze doelstelling was om deze multidisciplinaire richtlijn te adapteren aan de Nederlandse situatie met behulp van Nederlandse input, waarbij de aanbevelingen rekening houden met wetenschappelijk bewijs en zich richten op harm-benefit balans, en expert consensus om de gaten in wetenschappelijk bewijs op te vullen. Deze specifieke aanbevelingen kunnen dan gebruikt worden om indicatoren te ontwikkelen en te gebruiken voor kwaliteitsverbetering.

Deze richtlijn is opgesteld voor KNO-artsen en neurologen die in hun klinische praktijk in aanraking komen met BPPD. De richtlijn is toepasbaar in iedere setting waar BPPD gediagnosticeerd en behandeld wordt.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de module is in 2018 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met BPPD.

De werkgroepleden zijn door hun beroepsverenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname. De werkgroep is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze module.

Samenstelling huidige werkgroep:

- Dr. Tj.D. (Tjasse) Bruintjes, KNO-arts, Gelre Ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn, NVKNO (voorzitter)

- Dr. R.B. (Roeland) van Leeuwen, neuroloog, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn, NVN

- Dr. R. (Raymond) van de Berg, KNO-arts/vestibuloloog, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht, NVKNO

- Dr. M. (Marloes) Thoomes-de Graaf, fysiotherapeut/manueel therapeut/klinisch epidemioloog, Fysio-Experts, Hazerswoude, KNGF en NVMT

- R.A.K. (Sandra) Rutgers, arts, MPH en voorzitter Commissie Ménière Stichting Hoormij, Houten, Stichting Hoormij

Met ondersteuning van:

- D. (Dieuwke) Leereveld, MSc., senior adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. M. (Monique) Wessels, informatiespecialist Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Samenstelling oorspronkelijke werkgroep (2010):

- dr. Tj.D. Bruintjes (voorzitter), KNO-arts, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn

- prof. dr. H. Kingma, klinisch fysicus/vestibuloloog, Maastricht Universitair Medisch Centrum en Technische Universiteit Eindhoven

- dr. D.J.M. Mateijsen, KNO-arts, Catharina ziekenhuis, Eindhoven

- dr. R.B. van Leeuwen, neuroloog, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn

- dr. ir. T van Barneveld klinisch epidemioloog, Orde van Medisch specialisten (adviseur)

- dr. M.L. Molag, Orde van Medisch specialisten (adviseur)

Belangenverklaringen

De werkgroepleden hebben onafhankelijk gehandeld en waren vrij van financiële of zakelijke belangen betreffende het onderwerp van de richtlijn.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

De Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery foundation ‘Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’ (Bhattacharayya, et al., 2008) vormde het uitgangspunt van de onderhavige richtlijn. Daarnaast werd de Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of neurology gebruikt (Fife, et al., 2008). Dit betekent dat de Nederlandse richtlijncommissie de studies, de beoordeling & gradering ervan en de begeleidende tekst heeft overgenomen. Studies, relevant voor dit onderwerp, die nadien werden gepubliceerd konden in de richtlijncommissie worden ingebracht. De literatuur werd bovendien geupdate door te zoeken in Medline naar nieuw verschenen systematische reviews en RCTs met als onderwerp BPPD in de periode van 2008 t/m 2010.

De richtlijncommissie is voor elke aanbeveling in de Amerikaanse richtlijn nagegaan welke overwegingen naast het wetenschappelijk bewijs zijn gebruikt en of de door de commissie aangedragen studies de aanbeveling zouden kunnen veranderen. Wanneer er consensus was over deze overwegingen en door de commissie aangedragen studies geen ander inzicht opleverden, zijn de aanbevelingen overgenomen. Indien de commissie andere overwegingen (ook) van belang achtte of meende dat de door haar aangedragen studies een (iets) ander licht wierpen op de in de Amerikaanse richtlijn vermelde aanbeveling, zijn de aanbevelingen gemodificeerd.

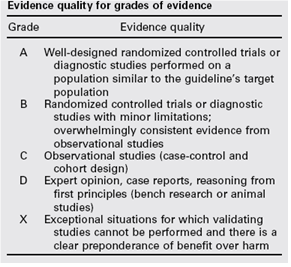

De gradering van de studies in de Amerikaanse richtlijn wijkt af van wat hier te lande gangbaar is. Vanuit het oogpunt van uniformiteit achtte de Nederlandse commissie het wenselijk de classificatie van bewijs c.q. gradering te converteren naar de Nederlandse classificatie. De Amerikaanse classificatie is hieronder afgebeeld in tabel. De corresponderende “Nederlandse” classificatie is in tabel 1.2 opgenomen.

Tabel 1.1: gradering van de studies in de Amerikaanse richtlijn

Tabel 1.2 Relatie tussen Evidence quality for grades of evidence en niveau van conclusie op basis van kwaliteit van bewijs conform Classificatieschema van CBO.

|

Evidence Quality - symbool |

Evidence Quality – omschrijving |

Niveau van conclusie – symbool |

Niveau van conclusie omschrijving |

|

A

|

Well-designed randomized controlled trials or diagnostic studies performed on a population similar to the guideline’s target population |

1 |

Meerdere gerandomiseerde dubbelblinde vergelijkende klinisch onderzoeken van goede kwaliteit van voldoende omvang, of

Meerdere onderzoeken ten opzichte van een referentietest (een ‘gouden standaard’) met tevoren gedefinieerde afkapwaarden en onafhankelijke beoordeling van de resultaten van test en gouden standaard, betreffende een voldoende grote serie van opeenvolgende patiënten die allen de index- en referentietest hebben gehad |

|

B |

Randomized controlled trials or diagnostic studies with minor limitations; overwhelmingly consistent evidence from observational studies |

2 |

Meerdere vergelijkende onderzoeken, maar niet met alle kenmerken als genoemd onder 1 (hieronder valt ook patiënt-controle onderzoek, cohort-onderzoek), of

Meerdere onderzoeken ten opzichte van een referentietest, maar niet met alle kenmerken die onder 1 zijn genoemd. |

|

C |

Observational studies (case-control and cohort design) |

||

|

D |

Expert opinion, case reports, reasoning from first principles (bench research or animal studies) |

3 en 4 |

Niet vergelijkend onderzoek of mening van deskundigen |

In de Amerikaanse richtlijn worden ook de aanbevelingen gegradeerd in termen van ‘strong recommendation’, ‘recommendation’, ‘option’. Hier te lande is graderen van aanbevelingen niet gebruikelijk. Om deze reden zijn in de Nederlandse richtlijn de aanbevelingen niet gegradeerd.

De literatuurzoekstrategie die de Amerikaanse richtlijncommissie heeft gevolgd, staat in bijlage 1 beschreven. Voor het opstellen van de aanbevelingen heeft de Amerikaanse richtlijncommissie gebruik gemaakt van de GuideLine Implementability Appraisal (GLIA) tool. Dit instrument dient om de helderheid van de aanbevelingen te verbeteren en potentiële belemmeringen voor de implementatie te voorspellen. In bijlage 3 wordt een aantal criteria beschreven. Ook de Nederlandse richtlijncommissie heeft deze criteria gehanteerd.