Noodzaak herevaluatie behandeling BPPD

Uitgangsvraag

Is het noodzakelijk om de respons op BPPD behandeling te evalueren?

Aanbeveling

Binnen een maand na de behandeling dient het effect van de behandeling geëvalueerd te worden.

Overwegingen

- Voordeel: identificatie van patiënten met aanhoudende klachten die in eerste instantie met observatie behandeld werden en die zouden kunnen profiteren van de repositiemanoeuvre of een hernieuwde manoeuvre moeten ondergaan. Identificatie van patiënten waarbij de diagnose herzien moet worden.

- Nadeel: geen

- Kosten: kosten van herbeoordeling

- Afweging: het voordeel weegt op tegen het nadeel.

- Waarde oordeel: bevestiging van de diagnose en het ondervangen van patiënten die zouden kunnen profiteren van een andere behandeling.

- Rol van de voorkeur van de patiënt: minimaal.

Onderbouwing

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Niveau 3 |

Het niet reageren op behandeling kan betekenen dat de oorspronkelijke diagnose niet goed was en dat er sprake is van centrale pathologie. Blijvende klachten betekenen een blijvend risico op vallen en verzuim.

|

Samenvatting literatuur

Patients with BPPV, regardless of initial treatment option rendered, will have variable responses to therapy (Cohen, et al., 2005). The response to therapy may depend on several factors including the accuracy of the diagnosis of BPPV, the duration of symptoms prior to the diagnosis of BPPV, compliance with prescribed therapy, and other factors (Hilton, et al., 2004) (Rupa, et al., 2004). Patients with BPPV should be reassessed within a set time interval after the diagnosis of BPPV for several reasons.

Failure to respond to initial therapy may indicate an initially erroneous diagnosis of BPPV, and one of the major goals of reassessment is to ensure the accuracy of diagnosis of BPPV. As noted, other more serious CNS disorders may mimic BPPV, and these conditions would not be expected to respond to traditional therapies prescribed for BPPV. In cohort studies, the rate of false-positive diagnosis for BPPV subsequently found to be CNS lesions after failed treatment (therefore, a highly selected population) with PRM ranges from 1.1 to 3 percent (Rupa, et al., 2004) (Dal, et al., 2000). Thus, persistence of symptoms after initial management requires clinicians to reassess and reevaluate patients for other etiologies of vertigo. Conversely, resolution of BPPV symptoms after initial therapy such as a PRM would corroborate an accurate diagnosis of BPPV.

Patients who are initially treated with vestibular rehabilitation may fail to resolve symptoms owing to multiple factors including poor compliance. In addition, patients who do not respond to initial therapy are likely to remain at risk for falls, decreased quality of life, and other consequences of unresolved BPPV. For these reasons, patients whose symptoms of BPPV fail to resolve should also be identified and classified as initial treatment failures. To define a treatment failure in BPPV, the clinician needs to determine both a failed outcome criterion and an appropriate time interval for assessment of treatment failure. Successful treatment outcomes for interventions for BPPV are traditionally measured in clinical trials by subjective symptom resolution and/or by conversion to a negative Dix-Hallpike test. Almost all treatment trials for BPPV report an outcome measure in the form of the patient’s reported symptoms, typically reported among three categorical outcomes: complete resolution of symptoms, improvement, or no improvement/worsening (Hilton, 2004). When included in meta-analyses, treatment responses are typically incorporated as “all or none” for the complete resolution of vertigo (Hilton, et al., 2004) (Woodworth, et al., 2004) (Teixeira, et al., 2006).

Because effective treatment options are available for BPPV that typically render patients symptom free (if treatment is successful), it is logical to use complete symptom resolution as the outcome of choice at the time of reassessment by the clinician. A symptom-based reassessment also allows clinicians to use clinical judgment as to the most appropriate modality for follow-up for individual patients, including telephone communication, electronic communication, or office based reexamination. This symptom-based assessment of treatment resolution should be detailed enough to distinguish patients with truly decreased symptoms related to treatment or patients with minimized symptoms attributable to positional avoidance (who, in fact, may not be treatment successes) from those with true symptom resolution (Woodworth, et al., 2004).

Although conversion to a negative Dix-Hallpike test may have the advantage of being a more objective reassessment than patients’ reported symptoms, it also carries the disadvantage of requiring a repeat clinical visit on the part of the patient with associated direct and indirect costs. The Dix- Hallpike test status is commonly reported in therapeutic trials of BPPV. Persistent symptoms of BPPV and other underlying conditions, however, have been reported in the face of negative Dix-Hallpike testing after therapy, potentially making this a less sensitive reassessment tool (Lynn, et al., 1995) (Magliulo, et al., 2005).

Conversely, patients may report an absence of symptoms after therapeutic intervention yet still have a positive Dix-Hallpike test (Cohen, et al., 2005) (Froehling, et al., 2000) (Sherman, et al., 2001). “Subclinical BPPV” has been offered as an explanation for this (Cohen, et al., 2005). Because of the potential discordance between negative Dix-Hallpike conversion and patients’ reported symptoms after treatment for BPPV, Dix- Hallpike conversion is not recommended as the primary reassessment criterion in routine clinical practice but may still be used as a secondary outcome measure. There is no widely accepted time interval at which to assess patients for treatment failure. Therapeutic trials in BPPV variably report follow-up assessments for treatment outcomes at 40 hours, 2 weeks, 1 month, and up to 6 months, although the most commonly chosen interval for follow-up assessment of treatment response is within or at 1 month (Hilton, et al., 2004) (Woodworth, et al., 2004) (Teixeira, et al., 2006). Because the natural history of BPPV exhibits a relatively consistent spontaneous rate of resolution with observation alone, a longer time interval between diagnosis and reassessment would allow patients with true BPPV to resolve symptoms spontaneously, likely irrespective of treatment (Sekine, et al., 2006).

Conversely, the choice of an excessively long time interval between diagnosis and reassessment would also allow cases of an erroneous BPPV diagnosis to potentially progress, leading to potential patient harm. In addition, because recurrence of BPPV may occur as early as 3 months after initial treatment, further delaying the time interval for reassessment may erroneously incorporate a recurrent BPPV syndrome (ie, the initial BPPV responded to treatment with a suitable symptom-free interval thereafter, followed by recurrent BPPV) rather than a persistent BPPV syndrome (Nunez, et al., 2000) (Helminski, et al., 2005).

Given that commonly reported rates of spontaneous complete symptom resolution at the 1-month interval for BPPV range from 20 to 80 percent at 1 month, reassessment at 1 month will also better allow for patients to be reconsidered for further interventional treatment to treat unresolved BPPV (Froehling, et al., 2000) (Lynn, et al., 1995) (Yimtae, et al., 2003) (Munoz, et al., 2007) (Sekine, et al., 2006) (von Brevern, et al., 2006). Thus, choosing a reassessment time interval of 1 month after diagnosis allows a relative balance between overly early reassessment (which would force the unnecessary reassessment of patients who would likely resolve with additional time) and unduly delayed reassessment (which would potentially allow harm from an unknown missed diagnosis or relegate patients to an excess time interval of symptomatic suffering from BPPV). One potential problem with a strict time interval for reassessment is that patients may not have been exposed to their initial treatment (vestibular rehabilitation or PRM as opposed to observation, which may begin immediately after diagnosis) within 1 month of diagnosis depending on referral patterns, patient preferences, or waiting lists for specialty evaluation and treatment. This situation is especially true when the diagnosing clinician may not be the same as the treating clinician. Even if a delay occurs between BPPV diagnosis and completion of the initial treatment, clinicians should still reassess patients at 1 month but may choose to reassign a second time interval for reassessment after completion of the initial treatment option.

Referenties

- Angeli, S.I., Hawley, R., Gomez, O. (2003). Systematic approach to benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in the elderly. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 128, 719-25.

- Asprella Libonati, G. (2005). Diagnostic and treatment strategy of lateral semicircular canal canalolithiasis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital, 25, 277-83.

- Bergenius, J., Perols, O. (1999). Vestibular neuritis: a follow-up study. Acta Otolaryngol, 119, 895-9.

- Bertholon, P., Bronstein, A.M., Davies, R.A., et al. (2002). Positional down beating nystagmus in 50 patients: cerebellar disorders and possible anterior semicircular canalithiasis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 72, 366-72.

- Beynon, G.J., Baguley, D.M., da Cruz, M.J. (2000). Recurrence of symptoms following treatment of posterior semicircular canal benign positional paroxysmal vertigo with a particle repositioning manoeuvre. J Otolaryngol, 29, 2-6.

- Black, F.O., Nashner, L.M. (1984). Postural disturbance in patients with benign paroxysmal positional nystagmus. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, 93, 595-9.

- Blatt, P.J., Georgakakis, G.A., Herdman, S.J., et al. (2000). The effect of the canalith repositioning maneuver on resolving postural instability in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Am J Otol, 21, 356-63.

- von Brevern, M., Seelig, T., Radtke, A., et al. (2006). Short-term efficacy of Epley’s manoeuvre: a double-blind randomised trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 77, 980-2.

- Brocchetti, F., Garaventa, G., Ameli, F., et al. (2003). Effect of repetition of Semont’s manoeuvre on benign paroxysmal positional vertigo of posterior semicircular canal. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital, 23, 428-35.

- Buttner, U., Helmchen, C., Brandt, T. (1999). Diagnostic criteria for central versus peripheral positioning nystagmus and vertigo: a review. Acta Otolaryngol, 119, 1-5.

- Casani, A.P., Vannucci, G., Fattori, B., et al. (2002). The treatment of horizontal canal positional vertigo: our experience in 66 cases. Laryngoscope, 112, 172-8.

- Chang, W.C., Hsu, L.C., Yang, Y.R., et al. (2006). Balance ability in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 135, 534-40.

- Chiou, W.Y., Lee, H.L., Tsai, S.C., et al. (2005). A single therapy for all subtypes of horizontal canal positional vertigo. Laryngoscope, 115, 1432-5.

- Cohen, H.S., Kimball, K.T. (2005). Effectiveness of treatments for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo of the posterior canal. Otol Neurotol, 26, 1034-40.

- Dal, T., Ozluoglu, L.N., Ergin, N.T. (2000). The canalith repositioning maneuver in patients with benign positional vertigo. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol, 257, 133-6.

- Dornhoffer, J.L., Colvin, G.B. (2000). Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and canalith repositioning: clinical correlations. Am J Otol, 21, 230-3.

- Dunniway, H.M., Welling, D.B. (1998). Intracranial tumors mimicking benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 118, 429-36.

- Fife, T.D. (1998). Recognition and management of horizontal canal benign positional vertigo. Am J Otol, 19, 345-51.

- Froehling, D.A., Bowen, J.M., Mohr, D.N., et al. (2000). The canalith repositioning procedure for the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc, 75, 695-700.

- Furman, J.M., Cass, S.P. (1999). Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. N Engl J Med, 341, 1590-6.

- Furman, J.M., Cass, S.P. (1995). A practical work-up for vertigo. Contemp Intern Med, 7, 24-7.

- Giacomini, P.G., Alessandrini, M., Magrini, A. (2002). Long-term postural abnormalities in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec, 64, 237-41.

- Gordon, C.R., Levite, R., Joffe, V., et al. (2004). Is posttraumatic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo different from the idiopathic form?. Arch Neurol, 61, 1590-3.

- Helminski, J.O., Janssen, I., Kotaspouikis, D., et al. (2005). Strategies to prevent recurrence of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 131, 344-8.

- Herdman, S.J., Tusa, R.J. (1996). Complications of the canalith repositioning procedure. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 122, 281-6.

- Hilton, M., Pinder, D. (2004). The Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 0, CD003162-.

- Hughes, C.A., Proctor, L. (1997). Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Laryngoscope, 107, 607-13.

- Jackson, L.E., Morgan, B., Fletcher, J.C., Jr., et al. (2007). Anterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: an underappreciated entity. Otol Neurotol, 28, 218-22.

- Kayan, A., Hood, J.D. (1984). Neuro-otological manifestations of migraine. Brain, 107, 1123-42.

- Lynn, S, Lynn, S., Pool, A., Rose, D., et al. (0000). Randomized trial of the canalith repositioning procedure. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 113, 712-720.

- Magliulo, G., Bertin, S., Ruggieri, M., et al. (2005). Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and post-treatment quality of life. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol, 262, 627-30.

- Monobe, H., Sugasawa, K., Murofushi, T. (2001). The outcome of the canalith repositioning procedure for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: are there any characteristic features of treatment failure cases?. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl, 545, 38-40.

- Munoz, J.E., Miklea, J.T., Howard, M., et al. (2007). Canalith repositioning maneuver for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: randomized controlled trial in family practice. Can Fam Physician, 53, 1049-53.

- Nunez, R.A., Cass, S.P., Furman, J.M. (2000). Short- and long-term outcomes of canalith repositioning for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 122, 647-52.

- Nuti, D., Agus, G., Barbieri, M.T., et al. (1998). The management of horizontalcanal paroxysmal positional vertigo. Acta Otolaryngol, 118, 455-60.

- Pollak, L., Davies, R.A., Luxon, L.L. (2002). Effectiveness of the particle repositioning maneuver in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo with and without additional vestibular pathology. Otol Neurotol, 23, 79-83.

- Roberts, R.A., Gans, R.E., Kastner, A.H., et al. (2005). Prevalence of vestibulopathy in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo patients with and without prior otologic history. Int J Audiol, 44, 191-6.

- Rupa, V. (2004). Persistent vertigo following particle repositioning maneuvers: an analysis of causes. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 130, 436-9.

- Sekine, K., Imai, T., Sato, G., et al. (2006). Natural history of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and efficacy of Epley and Lempert maneuvers. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 135, 529-33.

- Sherman, D., Massoud, E.A. (2001). Treatment outcomes of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Journal of Otolaryngology, 30, 295-9.

- Smouha, E.E., Roussos, C. (1995). Atypical forms of paroxysmal positional nystagmus. Ear Nose Throat J, 74, 649-56.

- Teixeira, L.J., Machado, J.N. (2006). Maneuvers for the treatment of benign positional paroxysmal vertigo: a systematic review. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol (Engl Ed), 72, 130-9.

- Tirelli, G., Russolo, M. (2004). 360-Degree canalith repositioning procedure for the horizontal canal. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 131, 740-6.

- Uneri, A. (2004). Migraine and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: an outcome study of 476 patients. Ear Nose Throat J, 83, 814-5.

- White, J.A., Coale, K.D., Catalano, P.J., et al. (2005). Diagnosis and management of lateral semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 133, 278-84.

- Woodworth, B.A., Gillespie, M.B., Lambert, P.R. (2004). The canalith repositioning procedure for benign positional vertigo: a meta-analysis. Laryngoscope, 114, 1143-6.

- Yimtae, K., Srirompotong, S., Sae-Seaw, P. (2003). A randomized trial of the canalith repositioning procedure. Laryngoscope, 113, 828-32.

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 20-08-2013

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-02-2020

De tekst van deze module is opgesteld tijdens de richtlijnontwikkeling in 2010 door de oorspronkelijke richtlijnwerkgroep (zie Samenstelling werkgroep). De module is opnieuw beoordeeld en nog actueel bevonden door de werkgroep samengesteld voor de richtlijnherziening in 2019 (zie samenstelling huidige werkgroep). Uiterlijk in 2024 bepaalt het bestuur van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Keel-Neus-Oorheelkunde en Heelkunde van het Hoofd-Halsgebied of de richtlijnmodule nog actueel is.

Algemene gegevens

Met ondersteuning van de Orde van Medisch Specialisten. De richtlijnontwikkeling werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De richtlijn betreft een adaptatie van:

Clinical practice guideline: Benigne Paroxysmale Positionele Duizeligheid.

De Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery foundation ‘Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’ (Bhattacharayya, et al., 2008) vormde het uitgangspunt van de onderhavige richtlijn. Daarnaast werd de Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of neurology, gericht op de behandeling van BPPD, gebruikt ter aanvulling (Fife, et al., 2008), alsmede de discussies en richtlijnen van de Standaardisatie commissie van de Barany Society (Reykjavik, et al., 2010, www.baranysociety.nl).

Doel en doelgroep

De primaire doelstellingen van deze richtlijn zijn:

- De kwaliteit van de zorg te verbeteren door middel van een accurate en snelle diagnose van BPPD.

- Voorkomen van onnodig gebruik van medicijnen.

- Doelgericht gebruik van aanvullend onderzoek.

- Stimuleren van het gebruik van repositiemanoeuvres als therapie voor BPPD.

Secundaire doelstellingen zijn: beperking van de kosten van diagnose en behandeling van BPPD, vermindering van het aantal artsenbezoeken, en verbetering van de kwaliteit van leven. Het grote aantal patiënten met BPPD en de verscheidenheid aan diagnostische en therapeutische interventies voor BPPD maakt dit een geschikt onderwerp voor een evidence-based richtlijn.

De Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery foundation ‘Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’ (Bhattacharayya, et al., 2008) vormde het uitgangspunt van de onderhavige richtlijn. Daarnaast werd de Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of neurology, gericht op de behandeling van BPPD, gebruikt ter aanvulling (Fife, et al., 2008), alsmede de discussies en richtlijnen van de Standaardisatie commissie van de Barany Society (Reykjavik, et al., 2010, www.baranysociety.nl)). Onze doelstelling was om deze multidisciplinaire richtlijn te adapteren aan de Nederlandse situatie met behulp van Nederlandse input, waarbij de aanbevelingen rekening houden met wetenschappelijk bewijs en zich richten op harm-benefit balans, en expert consensus om de gaten in wetenschappelijk bewijs op te vullen. Deze specifieke aanbevelingen kunnen dan gebruikt worden om indicatoren te ontwikkelen en te gebruiken voor kwaliteitsverbetering.

Deze richtlijn is opgesteld voor KNO-artsen en neurologen die in hun klinische praktijk in aanraking komen met BPPD. De richtlijn is toepasbaar in iedere setting waar BPPD gediagnosticeerd en behandeld wordt.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de module is in 2018 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met BPPD.

De werkgroepleden zijn door hun beroepsverenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname. De werkgroep is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze module.

Samenstelling huidige werkgroep:

- Dr. Tj.D. (Tjasse) Bruintjes, KNO-arts, Gelre Ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn, NVKNO (voorzitter)

- Dr. R.B. (Roeland) van Leeuwen, neuroloog, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn, NVN

- Dr. R. (Raymond) van de Berg, KNO-arts/vestibuloloog, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht, NVKNO

- Dr. M. (Marloes) Thoomes-de Graaf, fysiotherapeut/manueel therapeut/klinisch epidemioloog, Fysio-Experts, Hazerswoude, KNGF en NVMT

- R.A.K. (Sandra) Rutgers, arts, MPH en voorzitter Commissie Ménière Stichting Hoormij, Houten, Stichting Hoormij

Met ondersteuning van:

- D. (Dieuwke) Leereveld, MSc., senior adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. M. (Monique) Wessels, informatiespecialist Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Samenstelling oorspronkelijke werkgroep (2010):

- dr. Tj.D. Bruintjes (voorzitter), KNO-arts, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn

- prof. dr. H. Kingma, klinisch fysicus/vestibuloloog, Maastricht Universitair Medisch Centrum en Technische Universiteit Eindhoven

- dr. D.J.M. Mateijsen, KNO-arts, Catharina ziekenhuis, Eindhoven

- dr. R.B. van Leeuwen, neuroloog, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn

- dr. ir. T van Barneveld klinisch epidemioloog, Orde van Medisch specialisten (adviseur)

- dr. M.L. Molag, Orde van Medisch specialisten (adviseur)

Belangenverklaringen

De werkgroepleden hebben onafhankelijk gehandeld en waren vrij van financiële of zakelijke belangen betreffende het onderwerp van de richtlijn.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

De Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery foundation ‘Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’ (Bhattacharayya, et al., 2008) vormde het uitgangspunt van de onderhavige richtlijn. Daarnaast werd de Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of neurology gebruikt (Fife, et al., 2008). Dit betekent dat de Nederlandse richtlijncommissie de studies, de beoordeling & gradering ervan en de begeleidende tekst heeft overgenomen. Studies, relevant voor dit onderwerp, die nadien werden gepubliceerd konden in de richtlijncommissie worden ingebracht. De literatuur werd bovendien geupdate door te zoeken in Medline naar nieuw verschenen systematische reviews en RCTs met als onderwerp BPPD in de periode van 2008 t/m 2010.

De richtlijncommissie is voor elke aanbeveling in de Amerikaanse richtlijn nagegaan welke overwegingen naast het wetenschappelijk bewijs zijn gebruikt en of de door de commissie aangedragen studies de aanbeveling zouden kunnen veranderen. Wanneer er consensus was over deze overwegingen en door de commissie aangedragen studies geen ander inzicht opleverden, zijn de aanbevelingen overgenomen. Indien de commissie andere overwegingen (ook) van belang achtte of meende dat de door haar aangedragen studies een (iets) ander licht wierpen op de in de Amerikaanse richtlijn vermelde aanbeveling, zijn de aanbevelingen gemodificeerd.

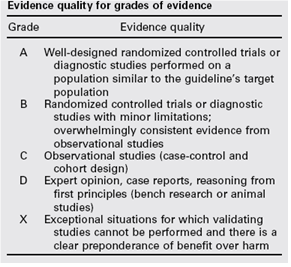

De gradering van de studies in de Amerikaanse richtlijn wijkt af van wat hier te lande gangbaar is. Vanuit het oogpunt van uniformiteit achtte de Nederlandse commissie het wenselijk de classificatie van bewijs c.q. gradering te converteren naar de Nederlandse classificatie. De Amerikaanse classificatie is hieronder afgebeeld in tabel. De corresponderende “Nederlandse” classificatie is in tabel 1.2 opgenomen.

Tabel 1.1: gradering van de studies in de Amerikaanse richtlijn

Tabel 1.2 Relatie tussen Evidence quality for grades of evidence en niveau van conclusie op basis van kwaliteit van bewijs conform Classificatieschema van CBO.

|

Evidence Quality - symbool |

Evidence Quality – omschrijving |

Niveau van conclusie – symbool |

Niveau van conclusie omschrijving |

|

A

|

Well-designed randomized controlled trials or diagnostic studies performed on a population similar to the guideline’s target population |

1 |

Meerdere gerandomiseerde dubbelblinde vergelijkende klinisch onderzoeken van goede kwaliteit van voldoende omvang, of

Meerdere onderzoeken ten opzichte van een referentietest (een ‘gouden standaard’) met tevoren gedefinieerde afkapwaarden en onafhankelijke beoordeling van de resultaten van test en gouden standaard, betreffende een voldoende grote serie van opeenvolgende patiënten die allen de index- en referentietest hebben gehad |

|

B |

Randomized controlled trials or diagnostic studies with minor limitations; overwhelmingly consistent evidence from observational studies |

2 |

Meerdere vergelijkende onderzoeken, maar niet met alle kenmerken als genoemd onder 1 (hieronder valt ook patiënt-controle onderzoek, cohort-onderzoek), of

Meerdere onderzoeken ten opzichte van een referentietest, maar niet met alle kenmerken die onder 1 zijn genoemd. |

|

C |

Observational studies (case-control and cohort design) |

||

|

D |

Expert opinion, case reports, reasoning from first principles (bench research or animal studies) |

3 en 4 |

Niet vergelijkend onderzoek of mening van deskundigen |

In de Amerikaanse richtlijn worden ook de aanbevelingen gegradeerd in termen van ‘strong recommendation’, ‘recommendation’, ‘option’. Hier te lande is graderen van aanbevelingen niet gebruikelijk. Om deze reden zijn in de Nederlandse richtlijn de aanbevelingen niet gegradeerd.

De literatuurzoekstrategie die de Amerikaanse richtlijncommissie heeft gevolgd, staat in bijlage 1 beschreven. Voor het opstellen van de aanbevelingen heeft de Amerikaanse richtlijncommissie gebruik gemaakt van de GuideLine Implementability Appraisal (GLIA) tool. Dit instrument dient om de helderheid van de aanbevelingen te verbeteren en potentiële belemmeringen voor de implementatie te voorspellen. In bijlage 3 wordt een aantal criteria beschreven. Ook de Nederlandse richtlijncommissie heeft deze criteria gehanteerd.