Differentiaal diagnose van BPPD

Uitgangsvraag

Van welke andere vormen van positioneringsduizeligheid moet BPPD worden onderscheiden?

Aanbeveling

BPPD moet met name gedifferentieerd worden van andere aandoeningen die zich presenteren met houdingsafhankelijke draaiduizeligheid, zoals bijvoorbeeld orthostatische hypotensie en vestibulaire uitval.

Onderbouwing

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Niveau 3 |

De differentiaaldiagnose van BPPD omvat alle aandoeningen die zich presenteren met houdingsafhankelijke duizeligheid. Hierbij moet vooral gedacht worden aan orthostatische hypotensie, centrale pathologie, angststoornissen (phobic postural vertigo) en vestibulaire migraine. Daarnaast dienen perifeer vestibulaire stoornissen, zoals bij voorbeeld M. Meniere, recurrent vestibulopathy, neuritis vestibularis en labyrinthitis, te worden overwogen. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Despite being the most common cause of peripheral vertigo, (Froehling, et al., 2000) BPPV is still often underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed (von Brevern, et al., 2004). Causes of vertigo that may be confused with BPPV can be divided into otological, neurological, and other entities. In subspecialty settings, BPPV caused 10.1% of vertigo, while neurological causes were rare (Bruintjes, et al., 2007).

The most common diagnoses that require distinction from BPPV are listed in Table 3.1. These conditions require distinction from BPPV because their natural history, treatment, and potential for serious medical sequelae differ significantly.

Otologic disorders

Other otological disorders causing vertigo may be differentiated from BPPV by their clinical characteristics including their temporal pattern and the presence or absence of hearing loss. Whereas BPPV is characterized by acute, discrete episodes of brief positional vertigo without associated hearing loss, other otological causes of vertigo manifest different temporal patterns and may additionally demonstrate associated hearing loss (Kentala, et al., 2003). In distinction to BPPV, Ménière’s disease is characterized by discrete episodic attacks, with each attack exhibiting a characteristic triad of sustained vertigo, fluctuating hearing loss, and tinnitus (Baloh, et al., 1987), (Wladislavosky-Waserman, et al., 1984). Recurrent vestibulopathy is characterized by similar episodic attacks of vertigo, but lacks any auditory symptoms (van Leeuwen et al., 2010).As opposed to BPPV, the duration of vertigo in an episode of Ménière’s disease or recurrent vestibulopathy typically lasts longer (usually on the order of hours) and is typically more disabling owing to both severity and duration. In addition, an associated contemporaneous decline in sensorineural hearing is required for the diagnosis of a Ménière’s attack, whereas acute hearing loss should not occur with an episode of BPPV (Thorp, et al., 2003). Protracted nausea and vomiting are also more common during an attack of Ménière’s disease or recurrent vestibulopathy.

Acute peripheral vestibular dysfunction syndromes, such as vestibular neuritis or labyrinthitis, present with sudden, unanticipated, severe vertigo with a subjective sensation of rotational (room spinning) motion. If the auditory portion of the inner ear is affected, hearing loss and tinnitus may also result (Baloh, et al., 2003). These syndromes are commonly preceded by a viral prodrome. The time course of the vertigo is often the best differentiator between BPPV and vestibular neuritis or labyrinthitis. In vestibular neuritis or labyrinthitis, the vertigo is of gradual onset, developing over several hours, followed by a sustained level of vertigo lasting days to weeks (Kentala, et al., 2003) (Kentala, et al., 1996) (Kentala, et al., 1999). The vertigo is present at rest (not requiring positional change for its onset), but it may be subjectively exacerbated by positional changes. These acute peripheral vestibular syndromes may also be accompanied by severe levels of nausea, vomiting, sweating, and pallor, which are also typically sustained along with the vertigo.

Tabel 3.1

Differentiaaldiagnose BPPD

|

Otologische stoornissen |

Neurologische stoornissen |

Andere oorzaken |

|

Ziekte van Menière |

Vestibulaire migraine |

Angst of paniekstoornissen |

|

Recurrent vestibulopathy Neuritis vestbularis |

Vertebrobasilaire TIA’s |

Orthostatische hypotensie |

|

Labyrinthitis |

Demyeliniserende ziektes (MS) |

Bijwerkingen van medicijnen |

|

Superior canal dehiscence syndrome |

Centraal zenuwstelsel lesies |

|

|

Posttraumatische vertigo |

|

|

Superior canal dehiscence syndrome (SCD) is clinically characterized by attacks of vertigo and oscillopsia (the sensation that viewed objects are moving or wavering back and forth) often brought on by loud sounds, Valsalva maneuvers, or pressure changes of the external auditory canals (Minor, et al., 2001). Similar to perilymphatic fistula, it differs from BPPV in that vertigo is induced by pressure changes and not position changes. SCD may also present with an associated conductive hearing loss and is diagnosed through CT of the temporal bones (Rosowski, et al., 2004).

Posttraumatic vertigo can present with a variety of clinical manifestations including vertigo, disequilibrium, tinnitus, and headache (Marzo, et al., 2004). Although BPPV is most often idiopathic, in specific cases, traumatic brain injury is associated with BPPV (Davies, et al., 1995). BPPV has been described as occurring in conjunction with or as a sequelae to other vestibular disorders as well, such as Ménière’s disease and vestibular neuritis (Karlberg, et al., 2000). Therefore, clinicians must consider the possibility of more than one vestibular disorder being present in any patient who does not clearly have the specific symptoms of a single vestibular entity.

Neurological disorders

One of the key issues facing clinicians attempting to diagnose the etiology for vertigo is the differentiation between peripheral causes of vertigo (those causes arising from the ear or vestibular apparatus) and CNS causes of vertigo. Although at times this distinction may be difficult, several clinical features may suggest a central cause of vertigo rather than BPPV (Labuguen, et al., 2006) (Baloh, et al., 1998). Nystagmus findings that more strongly suggest a neurological cause for vertigo, rather than a peripheral cause such as BPPV, include down-beating nystagmus on the Dix-Hallpike maneuver, direction-changing nystagmus occurring without changes in head position (ie, periodic alternating nystagmus), or baseline nystagmus manifesting without provocative maneuvers. Among the central causes of vertigo that should be distinguished from BPPV are migraine-associated vertigo, vertebrobasilar TIA, and intracranial tumors.

Vestibular migraine has been described as a common cause of vertigo in the adult population (Reploeg, et al., 2002) and may account for as many as 14 percent of cases of vertigo (Kentala, et al., 2003). Diagnostic criteria include 1) episodic vestibular symptoms; 2) migraine according to International Headache Society criteria; 3) at least two of the following migraine symptoms during at least two vertiginous episodes: migrainous headache, photophobia, phonophobia, or visual or other aura; and 4) other causes ruled out by appropriate investigations (Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society, 2004). Migraine-associated vertigo is heterogeneous in that both central disorders and peripheral disorders have been described, although more often it is believed to be central in nature (Neuhauser, et al., 2001), (von Brevern, et al., 2005). It is distinguishable from BPPV by virtue of the necessary migraine/headache components, which are not associated with classic BPPV.

Several reports have suggested that isolated attacks of vertigo can be the initial and only symptom of vertebrobasilar insufficiency (Fife, et al., 1994), (Grad, et al., 1989) (Gomez, et al., 1996). Isolated transient vertigo may precede a stroke in the vertebrobasilar artery by weeks or months. The attacks of vertigo in vertebrobasilar insufficiency usually last less then 30 minutes and have no associated hearing loss. The type of nystagmus (typically gaze-evoked in central lesions), the severity of postural instability, and the presence of additional neurological signs are the main distinguishing features between vertebrobasilar insufficiency and BPPV (Gomez, et al., 1996) (Hotson, et al., 1998). In addition, the nystagmus arising in vertebrobasilar insufficiency does not fatigue and is not easily suppressed by gaze fixation, helping to separate this diagnosis from BPPV.

Intracranial tumors and other brain stem lesions may rarely present with a history and symptomatology similar to those of BPPV (Dunniway, et al., 1998). In these cases, associated symptoms such as tinnitus, aural fullness, new-onset hearing loss, and/or other neurological symptoms should help differentiate these diagnoses from BPPV. Atypical nystagmus during Dix- Hallpike testing (eg, sustained down-beating nystagmus) argues against BPPV and suggests a more serious cause. Finally, failure to respond to conservative management such as the PRM or vestibular rehabilitation should raise concern that the underlying diagnosis may not be BPPV (Dunniway, et al., 1998).

Other disorders

Several other non-otological and non-neurological disorders may present similarly to BPPV. Patients with panic disorder, anxiety disorder, or agoraphobia may complain of symptoms of lightheadedness and dizziness. Although these symptoms are usually attributed to hyperventilation, other studies have shown high prevalences of vestibular dysfunction in these patients (Jacob, et al., 1996) (Furman, et al., 2006). These conditions may also mimic BPPV. Several medications, such as Mysoline, carbamazepine, phenytoin, antihypertensive medications, and cardiovascular medications, may produce side effects of dizziness and/or vertigo and should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Postural hypotension also may produce episodic dizziness or vertigo. The dizziness or vertigo in postural hypotension, however, is provoked by moving from the supine to the upright position in distinction to the provocative positional changes of BPPV.

Although the differential diagnosis of BPPV is vast, most of these other disorders can be further distinguished from BPPV on the basis of responses to the Dix-Hallpike maneuver and the supine roll test. Clinicians should still remain alert for concurrent diagnoses accompanying BPPV, especially in patients with a mixed clinical presentation.

Referenties

- Baloh, R.W. (2003). Clinical practice. Vestibular neuritis.. N Engl J Med, 348, 1027-32.

- Baloh, R.W. (1998). Differentiating between peripheral and central causes of vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 119, 55-9.

- Baloh, R.W., Honrubia, V., Jacobson, K. (1987). Benign positional vertigo: clinical and oculographic features in 240 cases. Neurology, 37, 371-8.

- von Brevern, M., Zeise, D., Neuhauser, H., et al. (2005). Acute migrainous vertigo: clinical and oculographic findings. Brain, 128, 365-74.

- von Brevern, M., Lezius, F., Tiel-Wilck, K., et al. (2004). Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: current status of medical management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 130, 381-2.

- Bruintjes, T.D., van Leeuwen, R.B. (2007). Ervaringen met multidisciplibaire benadering van duizeligheidsklachten: het Apeldoorns duizeligheidscentrum. Ned Tijdschr KNO-Heelkunde, 13 (4), 185-187.

- Davies, R.A., Luxon, L.M. (1995). Dizziness following head injury: a neurootological study. J Neurol, 242, 222-30.

- Fife, T.D., Baloh, R.W., Duckwiler, GR. (1994). Isolated dizziness in vertebrobasilar insufficiency: clinical features, angiography, and follow-up. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis, 4, 4-12.

- Dunniway, H.M., Welling, D.B. (1998). Intracranial tumors mimicking benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 118, 429-36.

- Froehling, D.A., Bowen, J.M., Mohr, D.N., et al. (2000). The canalith repositioning procedure for the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc, 75, 695-700.

- Furman, J.M., Redfern, M.S., Jacob, R.G. (2006). Vestibulo-ocular function in anxiety disorders. J Vestib Res, 16, 209-15.

- Gomez, C.R., Cruz-Flores, S., Malkoff, M.D., et al. (1996). Isolated vertigo as a manifestation of vertebrobasilar ischemia. Neurology, 47, 94-7.

- Grad, A., Baloh, R.W. (1989). Vertigo of vascular origin. Clinical and electronystagmographic features in 84 cases. Arch Neurol, 46, 281-4.

- Hanley, K., O’ Dowd, T. (2002). Symptoms of vertigo in general practice: a prospective study of diagnosis. Br J Gen Pract, 52, 809-12.

- Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache, S. (2004). The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia, 24, 9-160.

- Hotson, J.R., Baloh, R.W. (1998). Acute vestibular syndrome. N Engl J Med, 339, 680-5.

- Jacob, R.G., Furman, J.M., Durrant, J.D., et al. (1996). Panic, agoraphobia, and vestibular dysfunction. Am J Psychiatry, 153, 503-12.

- Karlberg, M., Hall, K., Quickert, N., et al. (2000). What inner ear diseases cause benign paroxysmal positional vertigo?. Acta Otolaryngol, 120, 380-5.

- Kentala, E., Rauch, S.D. (2003). A practical assessment algorithm for diagnosis of dizziness. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 128, 54-9.

- Kentala, E., Laurikkala, J., Pyykko, I., et al. (1999). Discovering diagnostic rules from a neurotologic database with genetic algorithms. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, 108, 948-54.

- Kentala, E. (1996). Characteristics of six otologic diseases involving vertigo. Am J Otol, 17, 883-92.

- Van Leeuwen, R.B., Bruintjes, T.D. (2010). Recurrent vestibulopathy: natural course and prognostic factors. J Laryngol Otol, 124, 19-22.

- Labuguen, R.H. (2006). Initial evaluation of vertigo. Am Fam Physician, 73, 244-51.

- Maarsingh, O.R., Dros, J., Schellevis, F.G., van Weert, H.C., Bindels, PJ., van der Horst, HE. (2010). Dizziness reported by elderly patients in family practice: prevalence, incidence and clinical characteristics. BMc, 11, 1-9.

- Marzo, S.J., Leonetti, J.P., Raffin, M.J., et al. (2004). Diagnosis and management of post-traumatic vertigo. Laryngoscope, 114, 1720-3.

- Minor, L.B., Cremer, P.D., Carey, J.P., et al. (2001). Symptoms and signs in superior canal dehiscence syndrome. Ann New York Acad Sci, 942, 259-73.

- Neuhauser, H., Leopold, M., von Brevern, M., et al. (2001). The interrelations of migraine, vertigo, and migrainous vertigo. Neurology, 56, 436-41.

- Reploeg, M.D., , Goebel, J.A. (2002). Migraine-associated dizziness: patient characteristics and management options. Otol Neurotol, 23, 364-71.

- Rosowski, J.J., Songer, J.E., Nakajima, H.H., et al. (2004). Clinical, experimental, and theoretical investigations of the effect of superior semicircular canal dehiscence on hearing mechanisms. Otol Neurotol, 25, 323-32.

- Thorp, M.A., Shehab, Z.P., Bance, M.L., et al. (2003). The AAO-HNS Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium guidelines for the diagnosis and evaluation of therapy in Ménière’s disease: have they been applied in the published literature of the last decade?. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci, 28, 173-6.

- Wladislavosky-Waserman, P., Facer, G.W., Mokri, B., et al. (1984). Ménière’s disease: a 30-year epidemiologic and clinical study in Rochester, MN, 1951-1980. Laryngoscope, 94, 1098-102.

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 16-08-2013

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-02-2020

De tekst van deze module is opgesteld tijdens de richtlijnontwikkeling in 2010 door de oorspronkelijke richtlijnwerkgroep (zie Samenstelling werkgroep). De module is opnieuw beoordeeld en nog actueel bevonden door de werkgroep samengesteld voor de richtlijnherziening in 2019 (zie samenstelling huidige werkgroep). Uiterlijk in 2024 bepaalt het bestuur van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Keel-Neus-Oorheelkunde en Heelkunde van het Hoofd-Halsgebied of de richtlijnmodule nog actueel is.

Algemene gegevens

Met ondersteuning van de Orde van Medisch Specialisten. De richtlijnontwikkeling werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De richtlijn betreft een adaptatie van:

Clinical practice guideline: Benigne Paroxysmale Positionele Duizeligheid.

De Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery foundation ‘Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’ (Bhattacharayya, et al., 2008) vormde het uitgangspunt van de onderhavige richtlijn. Daarnaast werd de Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of neurology, gericht op de behandeling van BPPD, gebruikt ter aanvulling (Fife, et al., 2008), alsmede de discussies en richtlijnen van de Standaardisatie commissie van de Barany Society (Reykjavik, et al., 2010, www.baranysociety.nl).

Doel en doelgroep

De primaire doelstellingen van deze richtlijn zijn:

- De kwaliteit van de zorg te verbeteren door middel van een accurate en snelle diagnose van BPPD.

- Voorkomen van onnodig gebruik van medicijnen.

- Doelgericht gebruik van aanvullend onderzoek.

- Stimuleren van het gebruik van repositiemanoeuvres als therapie voor BPPD.

Secundaire doelstellingen zijn: beperking van de kosten van diagnose en behandeling van BPPD, vermindering van het aantal artsenbezoeken, en verbetering van de kwaliteit van leven. Het grote aantal patiënten met BPPD en de verscheidenheid aan diagnostische en therapeutische interventies voor BPPD maakt dit een geschikt onderwerp voor een evidence-based richtlijn.

De Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery foundation ‘Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’ (Bhattacharayya, et al., 2008) vormde het uitgangspunt van de onderhavige richtlijn. Daarnaast werd de Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of neurology, gericht op de behandeling van BPPD, gebruikt ter aanvulling (Fife, et al., 2008), alsmede de discussies en richtlijnen van de Standaardisatie commissie van de Barany Society (Reykjavik, et al., 2010, www.baranysociety.nl)). Onze doelstelling was om deze multidisciplinaire richtlijn te adapteren aan de Nederlandse situatie met behulp van Nederlandse input, waarbij de aanbevelingen rekening houden met wetenschappelijk bewijs en zich richten op harm-benefit balans, en expert consensus om de gaten in wetenschappelijk bewijs op te vullen. Deze specifieke aanbevelingen kunnen dan gebruikt worden om indicatoren te ontwikkelen en te gebruiken voor kwaliteitsverbetering.

Deze richtlijn is opgesteld voor KNO-artsen en neurologen die in hun klinische praktijk in aanraking komen met BPPD. De richtlijn is toepasbaar in iedere setting waar BPPD gediagnosticeerd en behandeld wordt.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de module is in 2018 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met BPPD.

De werkgroepleden zijn door hun beroepsverenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname. De werkgroep is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze module.

Samenstelling huidige werkgroep:

- Dr. Tj.D. (Tjasse) Bruintjes, KNO-arts, Gelre Ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn, NVKNO (voorzitter)

- Dr. R.B. (Roeland) van Leeuwen, neuroloog, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn, NVN

- Dr. R. (Raymond) van de Berg, KNO-arts/vestibuloloog, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht, NVKNO

- Dr. M. (Marloes) Thoomes-de Graaf, fysiotherapeut/manueel therapeut/klinisch epidemioloog, Fysio-Experts, Hazerswoude, KNGF en NVMT

- R.A.K. (Sandra) Rutgers, arts, MPH en voorzitter Commissie Ménière Stichting Hoormij, Houten, Stichting Hoormij

Met ondersteuning van:

- D. (Dieuwke) Leereveld, MSc., senior adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. M. (Monique) Wessels, informatiespecialist Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Samenstelling oorspronkelijke werkgroep (2010):

- dr. Tj.D. Bruintjes (voorzitter), KNO-arts, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn

- prof. dr. H. Kingma, klinisch fysicus/vestibuloloog, Maastricht Universitair Medisch Centrum en Technische Universiteit Eindhoven

- dr. D.J.M. Mateijsen, KNO-arts, Catharina ziekenhuis, Eindhoven

- dr. R.B. van Leeuwen, neuroloog, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn

- dr. ir. T van Barneveld klinisch epidemioloog, Orde van Medisch specialisten (adviseur)

- dr. M.L. Molag, Orde van Medisch specialisten (adviseur)

Belangenverklaringen

De werkgroepleden hebben onafhankelijk gehandeld en waren vrij van financiële of zakelijke belangen betreffende het onderwerp van de richtlijn.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

De Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery foundation ‘Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’ (Bhattacharayya, et al., 2008) vormde het uitgangspunt van de onderhavige richtlijn. Daarnaast werd de Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of neurology gebruikt (Fife, et al., 2008). Dit betekent dat de Nederlandse richtlijncommissie de studies, de beoordeling & gradering ervan en de begeleidende tekst heeft overgenomen. Studies, relevant voor dit onderwerp, die nadien werden gepubliceerd konden in de richtlijncommissie worden ingebracht. De literatuur werd bovendien geupdate door te zoeken in Medline naar nieuw verschenen systematische reviews en RCTs met als onderwerp BPPD in de periode van 2008 t/m 2010.

De richtlijncommissie is voor elke aanbeveling in de Amerikaanse richtlijn nagegaan welke overwegingen naast het wetenschappelijk bewijs zijn gebruikt en of de door de commissie aangedragen studies de aanbeveling zouden kunnen veranderen. Wanneer er consensus was over deze overwegingen en door de commissie aangedragen studies geen ander inzicht opleverden, zijn de aanbevelingen overgenomen. Indien de commissie andere overwegingen (ook) van belang achtte of meende dat de door haar aangedragen studies een (iets) ander licht wierpen op de in de Amerikaanse richtlijn vermelde aanbeveling, zijn de aanbevelingen gemodificeerd.

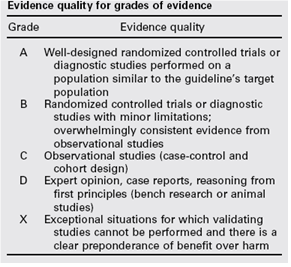

De gradering van de studies in de Amerikaanse richtlijn wijkt af van wat hier te lande gangbaar is. Vanuit het oogpunt van uniformiteit achtte de Nederlandse commissie het wenselijk de classificatie van bewijs c.q. gradering te converteren naar de Nederlandse classificatie. De Amerikaanse classificatie is hieronder afgebeeld in tabel. De corresponderende “Nederlandse” classificatie is in tabel 1.2 opgenomen.

Tabel 1.1: gradering van de studies in de Amerikaanse richtlijn

Tabel 1.2 Relatie tussen Evidence quality for grades of evidence en niveau van conclusie op basis van kwaliteit van bewijs conform Classificatieschema van CBO.

|

Evidence Quality - symbool |

Evidence Quality – omschrijving |

Niveau van conclusie – symbool |

Niveau van conclusie omschrijving |

|

A

|

Well-designed randomized controlled trials or diagnostic studies performed on a population similar to the guideline’s target population |

1 |

Meerdere gerandomiseerde dubbelblinde vergelijkende klinisch onderzoeken van goede kwaliteit van voldoende omvang, of

Meerdere onderzoeken ten opzichte van een referentietest (een ‘gouden standaard’) met tevoren gedefinieerde afkapwaarden en onafhankelijke beoordeling van de resultaten van test en gouden standaard, betreffende een voldoende grote serie van opeenvolgende patiënten die allen de index- en referentietest hebben gehad |

|

B |

Randomized controlled trials or diagnostic studies with minor limitations; overwhelmingly consistent evidence from observational studies |

2 |

Meerdere vergelijkende onderzoeken, maar niet met alle kenmerken als genoemd onder 1 (hieronder valt ook patiënt-controle onderzoek, cohort-onderzoek), of

Meerdere onderzoeken ten opzichte van een referentietest, maar niet met alle kenmerken die onder 1 zijn genoemd. |

|

C |

Observational studies (case-control and cohort design) |

||

|

D |

Expert opinion, case reports, reasoning from first principles (bench research or animal studies) |

3 en 4 |

Niet vergelijkend onderzoek of mening van deskundigen |

In de Amerikaanse richtlijn worden ook de aanbevelingen gegradeerd in termen van ‘strong recommendation’, ‘recommendation’, ‘option’. Hier te lande is graderen van aanbevelingen niet gebruikelijk. Om deze reden zijn in de Nederlandse richtlijn de aanbevelingen niet gegradeerd.

De literatuurzoekstrategie die de Amerikaanse richtlijncommissie heeft gevolgd, staat in bijlage 1 beschreven. Voor het opstellen van de aanbevelingen heeft de Amerikaanse richtlijncommissie gebruik gemaakt van de GuideLine Implementability Appraisal (GLIA) tool. Dit instrument dient om de helderheid van de aanbevelingen te verbeteren en potentiële belemmeringen voor de implementatie te voorspellen. In bijlage 3 wordt een aantal criteria beschreven. Ook de Nederlandse richtlijncommissie heeft deze criteria gehanteerd.