Diagnose BPPD posterieure kanaal

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de beste manier om BPPD van het posterieure kanaal (p-BPPD) te diagnosticeren?

Aanbeveling

De diagnose BPPD van het posterieur kanaal wordt gesteld wanneer draaiduizeligheid met nystagmus wordt opgewekt door de Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre.

Overwegingen

- Voordeel: duidelijkheid omtrent de diagnose

- Nadelen: het mogelijk provoceren van draaiduizeligheid

- Kosten: minimaal

- Afweging van voordeel tegen nadeel: het voordeel weegt zwaarder.

- Waarde oordelen: Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre is de gouden standaard testmethode voor het stellen van de diagnose BPPD

- Rol van de voorkeur van de patiënt: minimaal.

- Exclusie: patiënten met fysieke beperkingen van de nek, zoals ernstige reumatoïde arthritis en cervicale radiculopathie.

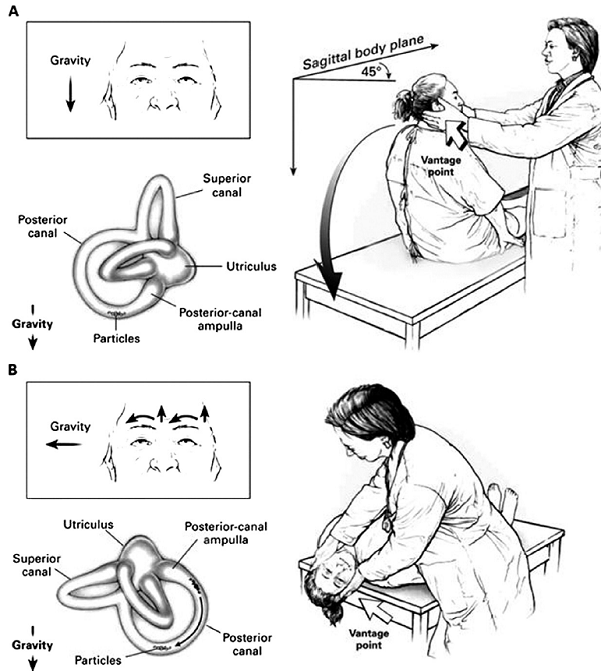

Figure 2.1

Diagrammatic representation of performance of the Dix-Hallpike maneuver for the diagnosis of posterior canal BPPV (adapted from Furman et al., 1999). (A) The examiner stands at the patient’s right side and rotates the patient’s head 45 degrees to the right to align the right posterior semicircular canal with the sagittal plane of the body. (B) The examiner moves the patient, whose eyes are open, from the seated to the supine right-ear-down position and then extends the patient’s neck slightly so that the chin is pointed slightly upward. The latency, duration, and direction of nystagmus, if present, and the latency and duration of vertigo, if present, should be noted. The arrows in the inset depict the direction of nystagmus in patients with typical benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. A presumed location in the labyrinth of the free-floating debris thought to cause the disorder is also shown.

Onderbouwing

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Niveau 2 |

De Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre is de gouden standaard om posterieur kanaal BPPD te diagnosticeren. |

|

Niveau 4 |

Het is niet aangetoond, maar het lijkt waarschijnlijk dat video-oculografie behulpzaam is bij het interpreteren van de nystagmus en biedt het voordeel dat documentatie van de nystagmus mogelijk is. De experts zijn van mening dat voor het beoordelen van de nystagmus een Frenzel bril niet strikt noodzakelijk is.

Niveau D: bronnen (niet-vergelijkend onderzoek Jackson et al 2007, en case studie Bertholon 2002)) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Posterior semicircular canal BPPV is diagnosed when 1) patients report a history of vertigo provoked by changes in head position relative to the gravity vector and 2) when, on physical examination, characteristic nystagmus is provoked by the Dix-Hallpike maneuver (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1. Diagnostic criteria for posterior canal BPPV

|

History |

Patient reports repeated episodes of vertigo with changes in head position. |

|

Physical examination

|

Each of the following criteria are fulfilled: ● Vertigo associated with nystagmus is provoked by the Dix-Hallpike test. ● There is a latency period between the completion of the Dix-Hallpike test and the onset of vertigo and nystagmus. ● The provoked vertigo and nystagmus increase and then resolve within a time period of 60 seconds from onset of nystagmus. |

History

Vertigo has been defined as an “illusory sensation of motion of either the self or the surroundings.” (Blakley, et al., 2001) The symptoms of vertigo resulting from posterior canal BPPV are typically described by the patient as a rotational or spinning sensation when the patient changes head position relative to gravity.

The episodes are often provoked by everyday activities and commonly occur when rolling over in bed or when the patient is tilting the head to look upward (eg, to place an object on a shelf higher than the head) or bending forward (eg, to tie shoes) (von Brevern, et al., 2007) (Furman, et al., 1999) (Dix, et al., 1952) (Whitney, et al., 2005).

Patients with BPPV most commonly report discrete, episodic periods of vertigo lasting 1 minute or less and often report modifications or limitations of their general movements to avoid provoking the vertiginous episodes (Ruckenstein, et al., 2007). Other investigators report that true “room spinning” vertigo is not always present as a reported symptom in posterior canal BPPV, with patients alternatively complaining of lightheadedness, dizziness, nausea, or the feeling of being “off balance” (Katsarkas, et al., 1999) (von Brevern, et al., 2007) (Herdman, et al., 1997) (Herdman, et al., 1997) (Macias, et al., 2000)(Cohen, et al., 2004) (Haynes, et al., 2002) (Blatt, et al., 2000) (Norre, et al., 1995). Approximately 50 percent of patients also report subjective imbalance between the classic episodes of BPPV (von Brevern, et al., 2007). In contrast, a history of vertigo without associated lightheadedness may increase the a priori likelihood of a diagnosis of posterior canal BPPV (Oghalai, et al., 2000). In up to one third of cases with atypical histories of positional vertigo, Dix-Hallpike testing will still reveal positional nystagmus, strongly suggesting the diagnosis of posterior canal BPPV (Norre, et al., 1995).

Other authors have loosened the historical criteria required for BPPV diagnosis with coinage of the term “subjective BPPV” without a positive Dix-Hallpike test (Haynes, et al., 2002) (Numez, et al., 2000). However, in clinical practice, there is a practical need to balance inclusiveness of diagnosis with accuracy of diagnosis.

Physical examination

In addition to the historical criteria for the diagnosis of posterior canal BPPV, clinicians should confirm the diagnosis of posterior canal BPPV by performing the Dix-Hallpike maneuver (Table 2.1, Fig 2.1). The nystagmus produced by the Dix-Hallpike maneuvers in posterior canal BPPV typically displays two important diagnostic characteristics. First, there is a latency period between the completion of the maneuver, and the onset of subjective rotational vertigo and the objective nystagmus.

The latency period for the onset of the nystagmus with this maneuver is largely unspecified in the literature, but the panel felt that a typical latency period would range from 5 to 20 seconds, although it may be as long as 1 minute in rare cases (Baloh, et al., 1987). Second, the provoked subjective vertigo and the nystagmus increase, and then resolve within a time period of 60 seconds from the onset of nystagmus.

The fast component of the nystagmus provoked by the Dix-Hallpike maneuver demonstrates a characteristic mixed torsional and vertical movement (often described as upbeating-torsional), with the upper pole of the eye beating toward the dependent ear and the vertical component beating toward the forehead (Fig 2.1) (Furman, et al., 1999) (Honrubia, et al., 1999). Temporally, the rate of nystagmus typically begins gently, increases in intensity, and then declines in intensity as it resolves. This has been termed crescendo-decrescendo nystagmus. The nystagmus is again commonly observed after the patient returns to the upright head position and upon arising, but the direction of the nystagmus may be reversed.

Another classical feature of the nystagmus associated with posterior canal BPPV is that the nystagmus typically fatigues (a reduction in severity of nystagmus) when the maneuver is repeated (Dix, et al., 1952) (Honrubia, et al., 1999). However, repeated performance of the Dix-Hallpike maneuver to demonstrate fatigability is not recommended, because it unnecessarily subjects patients to repeated symptoms of vertigo that may be discomforting, and repeat performance may interfere with the immediate bedside treatment of BPPV (Furman, et al., 1999). Therefore, the panel did not include fatigability of the nystagmus as a diagnostic criterion.

Performing the Dix-Hallpike Diagnostic Maneuver

The Dix-Hallpike maneuver is performed by the clinician moving the patient through a set of specified head-positioning maneuvers to elicit the expected characteristic nystagmus of posterior canal BPPV (Fig 2.1) (Furman, et al., 1999) (Dix, et al., 1952). Before beginning the maneuver, the clinician should counsel the patient regarding the upcoming movements and warn that they may provoke a sudden onset of intense subjective vertigo, possibly with nausea, which will subside within 60 seconds. Because the patient is going to be placed in the supine position relatively quickly with the head position slightly below the body, the patient should be oriented so that, in the supine position, the head can “hang” with support off the posterior edge of the examination. The examiner should ensure that he can support the patient’s head and guide the patient through the maneuver safely and securely, without the examiner losing support or balance himself.

1. The maneuver begins with the patient in the upright seated position with the examiner standing at the patient’s side (Furman, et al., 1999). If present, the patient’s eyeglasses should be removed. We initially describe the maneuver to test the right ear as the source of the posterior canal BPPV.

2. The examiner rotates the patient’s head 45 degrees to the right and, with manual support, maintains the 45-degree head turn to the right during the next part of the maneuver.

3. Next, the examiner fairly quickly moves the patient (who is instructed to keep the eyes open) from the seated to the supine right-ear down position and then extends the patient’s neck slightly (approximately 20 degrees below the horizontal plane) so that the patient’s chin is pointed slightly upward, with the head hanging off the edge of the examining table and supported by the examiner. The examiner observes the patient’s eyes for the latency, duration, and direction of the nystagmus (Norre, et al., 1988) (White, et al., 2005). Again, the provoked nystagmus in posterior canal BPPV is classically described as a more or less mixed torsional movement with the upper pole of both eyes beating toward the affected ear (in this example the right ear) in combination with a vertical (upbeat) component. The patient should also be queried as to the presence of subjective vertigo.

4. After resolution of the subjective vertigo and the nystagmus, if present, the patient may be slowly returned to the upright position. During the return to the upright position, a reversal of the nystagmus may be observed and should be allowed to resolve (a torsional nystagmus to the healthy ear, in combination with a vertical (downbeat) component).

5. The Dix-Hallpike maneuver (steps 1-4) should then be repeated for the left side, with the left ear arriving at the dependent position (Numez, et al., 2000). Again, the examiner should inquire about subjective vertigo and identify objective nystagmus, when present. The examination of the left side completes the test. The provoked nystagmus in left ear posterior canal BPPV is more or less mixed torsional movement with the upper pole of both eyes beating toward the affected ear (in this example the left ear) in combination with a vertical (upbeat) component. The Dix-Hallpike maneuver is considered the gold standard test for the diagnosis of posterior canal BPPV (Fife, et al., 2008). It is the most common diagnostic criterion required for entry into clinical trials and for inclusion of such trials in meta-analyses`(Hilton, et al., 2004) (Cohen, et al., 2005). The lack of an alternative external gold standard to the Dix Hallpike maneuver limits the availability of rigorous sensitivity and specificity data. Although it is considered the gold standard test for posterior canal BPPV diagnosis, its accuracy may differ between specialty and nonspecialty clinicians. Lopez-Escamez et al (Lopez-Escamez, et al., 2000) have reported a sensitivity of 82 percent and specificity of 71 percent for the Dix-Hallpike maneuvers in posterior canal BPPV, primarily among specialty clinicians. In the primary care setting, Hanley and O’Dowd (Hanley, et al., 2002) have reported a positive predictive value for a positive Dix-Hallpike test of 83 percent and a negative predictive value of 52 percent for the diagnosis of BPPV. Therefore, a negative Dix-Hallpike maneuver does not necessarily rule out a diagnosis of posterior canal BPPV. Because of the lower negative predictive values of the Dix-Hallpike maneuver, it has been suggested that this maneuver may need to be repeated at a separate visit to confirm the diagnosis and avoid a false-negative result (Numez, et al., 2000) (Viire, et al., 2005) (Norre, et al., 1994).

Factors that may affect the diagnostic accuracy of the Dix-Hallpike maneuver include the speed of movements during the test, time of day, and the angle of the plane of the occiput during the maneuver (Numez, et al., 2000). The Dix-Hallpike test must be done bilaterally to determine which ear is involved or if both ears are involved (Numez, et al., 2000). In a small percent of cases, the Dix-Hallpike maneuver may be bilaterally positive (ie, the correspondingly appropriate nystagmus is elicited for each ear in the dependent position). For example, bilateral posterior canal BPPV is more likely to be encountered after head trauma (Katsarkas, et al., 1999).

Although the Dix-Hallpike maneuver is the test of choice to confirm the diagnosis of posterior canal BPPV, it should be avoided in certain circumstances. Although there are no documented reports of vertebrobasilar insufficiency provoked by performing the Dix-Hallpike maneuver, clinicians

should be careful to consider the risk of stroke or vascular injury in patients with significant vascular disease (Whitney, et al., 2006). Care should also be exercised in patients with cervical stenosis, severe kyphoscoliosis, limited cervical range of motion, Down syndrome, severe rheumatoid arthritis, cervical radiculopathies, Paget’s disease, ankylosing spondylitis, low back dysfunction, spinal cord injuries, and morbid obesity (Whitney, et al., 2005) (Whitney, et al., 2006). Patients who are obese may be difficult for a single examiner to fully support throughout the maneuver, so additional assistance may be required. For patients with physical limitations, special tilting examination tables may allow the safe performance of the Dix-Hallpike maneuver.

To our knowledge, no comparative studies have been performed so far to investigate whether the diagnostic accuracy of the Hallpike maneuver with observation of the nystagmus by the naked eye improves by the use of Frenzel’s glasses or infra-red Video-Oculography.

Referenties

- Baloh, R.W., Jacobson, K., Honrubia, V. (1993). Horizontal semicircular canal variant of benign positional vertigo. Neurology, 43, 2542-9.

- Baloh, R.W., Honrubia, V., Jacobson, K. (1987). Benign positional vertigo: clinical and oculographic features in 240 cases. Neurology, 37, 371-8.

- Blakley, B.W., Goebel, J. (2001). The meaning of the word “vertigo". Otolaryngoly Head Neck Surg, 125, 147-50.

- Blatt, P.J., Georgakakis, G.A., Herdman, S.J., et al. (2000). The effect of the canalith repositioning maneuver on resolving postural instability in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Am J Otol, 21, 356-63.

- von Brevern, M., Radtke, A., Lezius, F., et al. (2007). Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a population based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 78, 710-5.

- Cakir, B.O, Cakir, B.O., Ercan, I., Cakir, Z.A., et al. (0000). What is the true incidence of horizontal semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. X, 0, X-.

- Califano, L., Melillo, M.G., Mazzone, S. (2010). Vassallo "Secondary signs of lateralization" in apogeotropic lateral canalolithiasis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital, 30 (2), 78-86.

- Caruso, G., Nuti, D. (2005). Epidemiological data from 2270 PPV patients. Audiol Med, 3, 7-11.

- Casani, A.P., Vannucci, G., Fattori, B., et al. (2002). The treatment of horizontal canal positional vertigo: our experience in 66 cases. Laryngoscope, 112, 172-8.

- Cohen, H.S., Kimball, KT. (2005). Effectiveness of treatments for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo of the posterior canal. Otol Neurotol, 26, 1034-40.

- Cohen, H.S. (2004). Side-lying as an alternative to the Dix-Hallpike test of the posterior canal. Otol Neurotol, 25, 130-4.

- Dix, M.R., Hallpike, CS. (1952). The pathology, symptomatology and diagnosis of certain common disorders of the vestibular system. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, 61, 987-1016.

- Fife, T.D., Iverson, D.J., Lempert, T., et al. (2008). Practice parameter: therapies for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (an evidence-based review): Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology, 70, 2067-74.

- Furman, J.M., Cass, S.P. (1999). Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. N Engl J Med, 341, 1590-6.

- Han, B.I., Oh, H.J., Kim, J.S. (2006). Nystagmus while recumbent in horizontal canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Neurology, 66, 706-10.

- Hanley, K., O’ Dowd, T. (2002). Symptoms of vertigo in general practice: a prospective study of diagnosis. Br J Gen Pract, 52, 809-12.

- Haynes, D.S., Resser, J.R., Labadie, R.F., et al. (2002). Treatment of benign positional vertigo using the semont maneuver: efficacy in patients presenting without nystagmus. Laryngoscope, 112, 796-801.

- Herdman, S.J. (1997). Advances in the treatment of vestibular disorders. Phys Ther, 77, 602-18.

- Hilton, M., Pinder, D. (2004). The Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 0, CD003162-.

- Honrubia, V., Baloh, R.W., Harris, M.R., et al. (1999). Paroxysmal positional vertigo syndrome. Am J Otol, 20, 465-70.

- Hornibrook, J. (2004). Horizontal canal benign positional vertigo. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, 113, 721-5.

- Imai, T., Ito, M., Takeda, N., et al. (2005). Natural course of the remission of vertigo in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Neurology, 64, 920-1.

- Katsarkas, A. (1999). Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV): idiopathic versus post-traumatic. Acta Otolaryngol, 119, 745-9.

- Lopez-Escamez, J.A., Lopez-Nevot, A., Gamiz, M.J., et al. (2000). Diagnosis of common causes of vertigo using a structured clinical history. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp, 51, 25-30.

- Macias, J.D., Lambert, K.M., Massingale, S., et al. (2000). Variables affecting treatment in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Laryngoscope, 110, 1921-4.

- Moon, S.Y., Kim, J.S., Kim, B.K., et al. (2006). Clinical characteristics of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in Korea: a multicenter study. J Korean Med Sci, 21, 539-43.

- Norre, M.E. (1995). Reliability of examination data in the diagnosis of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Am J Otol, 16, 806-10.

- Norre, M.E. (1994). Diagnostic problems in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Laryngoscope, 104, 1385-8.

- Norre, M.E., Beckers, A. (1988). Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in the elderly. Treatment by habituation exercises.. J Am Geriatr Soc, 36, 425-9.

- Nunez, R.A., Cass, S.P., Furman, J.M. (2000). Short- and long-term outcomes of canalith repositioning for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 122, 647-52.

- Nuti, D., Agus, G., Barbieri, MT., et al. (1998). The management of horizontalcanal paroxysmal positional vertigo. Acta Otolaryngol, 118, 455-60.

- Oghalai, J.S., Manolidis, S., Barth, J.L., et al. (2000). Unrecognized benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in elderly patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 122, 630-4.

- Ruckenstein, M.J., Shepard, N.T. (2007). The canalith repositioning procedure with and without mastoid oscillation for the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec, 69, 295-8.

- Steenerson, R.L., Cronin, G.W., Marbach, P.M. (2005). Effectiveness of treatment techniques in 923 cases of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Laryngoscope, 115, 226-31.

- Tirelli, G., Russolo, M. (2004). 360-Degree canalith repositioning procedure for the horizontal canal. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 131, 740-6.

- Viirre, E., Purcell, I., Baloh, R.W. (2005). The Dix-Hallpike test and the canalith repositioning maneuver. Laryngoscope, 115, 184-7.

- White, J., Savvides, P., Cherian, N., et al. (2005). Canalith repositioning for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otol Neurotol, 26, 704-10.

- Whitney, S.L., Morris, L.O. (2006). Multisensory impairment in older adults: evaluation and intervention. In: Geriatric Otolaryngology. Calhoun KH, Eibling DE, ed. New York: Taylor and Francis, 0, 115-.

- Whitney, S.L., Marchetti, G.F., Morris, L.O. (2005). Usefulness of the dizziness handicap inventory in the screening for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otol Neurotol, 26, 1027-33.

- White, J.A., Coale, K.D., Catalano, P.J., et al. (2005). Diagnosis and management of lateral semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 133, 278-84.

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 16-08-2013

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-02-2020

De tekst van deze module is opgesteld tijdens de richtlijnontwikkeling in 2010 door de oorspronkelijke richtlijnwerkgroep (zie Samenstelling werkgroep). De module is opnieuw beoordeeld en nog actueel bevonden door de werkgroep samengesteld voor de richtlijnherziening in 2019 (zie samenstelling huidige werkgroep). Uiterlijk in 2024 bepaalt het bestuur van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Keel-Neus-Oorheelkunde en Heelkunde van het Hoofd-Halsgebied of de richtlijnmodule nog actueel is.

Algemene gegevens

Met ondersteuning van de Orde van Medisch Specialisten. De richtlijnontwikkeling werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De richtlijn betreft een adaptatie van:

Clinical practice guideline: Benigne Paroxysmale Positionele Duizeligheid.

De Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery foundation ‘Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’ (Bhattacharayya, et al., 2008) vormde het uitgangspunt van de onderhavige richtlijn. Daarnaast werd de Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of neurology, gericht op de behandeling van BPPD, gebruikt ter aanvulling (Fife, et al., 2008), alsmede de discussies en richtlijnen van de Standaardisatie commissie van de Barany Society (Reykjavik, et al., 2010, www.baranysociety.nl).

Doel en doelgroep

De primaire doelstellingen van deze richtlijn zijn:

- De kwaliteit van de zorg te verbeteren door middel van een accurate en snelle diagnose van BPPD.

- Voorkomen van onnodig gebruik van medicijnen.

- Doelgericht gebruik van aanvullend onderzoek.

- Stimuleren van het gebruik van repositiemanoeuvres als therapie voor BPPD.

Secundaire doelstellingen zijn: beperking van de kosten van diagnose en behandeling van BPPD, vermindering van het aantal artsenbezoeken, en verbetering van de kwaliteit van leven. Het grote aantal patiënten met BPPD en de verscheidenheid aan diagnostische en therapeutische interventies voor BPPD maakt dit een geschikt onderwerp voor een evidence-based richtlijn.

De Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery foundation ‘Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’ (Bhattacharayya, et al., 2008) vormde het uitgangspunt van de onderhavige richtlijn. Daarnaast werd de Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of neurology, gericht op de behandeling van BPPD, gebruikt ter aanvulling (Fife, et al., 2008), alsmede de discussies en richtlijnen van de Standaardisatie commissie van de Barany Society (Reykjavik, et al., 2010, www.baranysociety.nl)). Onze doelstelling was om deze multidisciplinaire richtlijn te adapteren aan de Nederlandse situatie met behulp van Nederlandse input, waarbij de aanbevelingen rekening houden met wetenschappelijk bewijs en zich richten op harm-benefit balans, en expert consensus om de gaten in wetenschappelijk bewijs op te vullen. Deze specifieke aanbevelingen kunnen dan gebruikt worden om indicatoren te ontwikkelen en te gebruiken voor kwaliteitsverbetering.

Deze richtlijn is opgesteld voor KNO-artsen en neurologen die in hun klinische praktijk in aanraking komen met BPPD. De richtlijn is toepasbaar in iedere setting waar BPPD gediagnosticeerd en behandeld wordt.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de module is in 2018 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met BPPD.

De werkgroepleden zijn door hun beroepsverenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname. De werkgroep is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze module.

Samenstelling huidige werkgroep:

- Dr. Tj.D. (Tjasse) Bruintjes, KNO-arts, Gelre Ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn, NVKNO (voorzitter)

- Dr. R.B. (Roeland) van Leeuwen, neuroloog, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn, NVN

- Dr. R. (Raymond) van de Berg, KNO-arts/vestibuloloog, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht, NVKNO

- Dr. M. (Marloes) Thoomes-de Graaf, fysiotherapeut/manueel therapeut/klinisch epidemioloog, Fysio-Experts, Hazerswoude, KNGF en NVMT

- R.A.K. (Sandra) Rutgers, arts, MPH en voorzitter Commissie Ménière Stichting Hoormij, Houten, Stichting Hoormij

Met ondersteuning van:

- D. (Dieuwke) Leereveld, MSc., senior adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. M. (Monique) Wessels, informatiespecialist Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Samenstelling oorspronkelijke werkgroep (2010):

- dr. Tj.D. Bruintjes (voorzitter), KNO-arts, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn

- prof. dr. H. Kingma, klinisch fysicus/vestibuloloog, Maastricht Universitair Medisch Centrum en Technische Universiteit Eindhoven

- dr. D.J.M. Mateijsen, KNO-arts, Catharina ziekenhuis, Eindhoven

- dr. R.B. van Leeuwen, neuroloog, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn

- dr. ir. T van Barneveld klinisch epidemioloog, Orde van Medisch specialisten (adviseur)

- dr. M.L. Molag, Orde van Medisch specialisten (adviseur)

Belangenverklaringen

De werkgroepleden hebben onafhankelijk gehandeld en waren vrij van financiële of zakelijke belangen betreffende het onderwerp van de richtlijn.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

De Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery foundation ‘Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’ (Bhattacharayya, et al., 2008) vormde het uitgangspunt van de onderhavige richtlijn. Daarnaast werd de Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of neurology gebruikt (Fife, et al., 2008). Dit betekent dat de Nederlandse richtlijncommissie de studies, de beoordeling & gradering ervan en de begeleidende tekst heeft overgenomen. Studies, relevant voor dit onderwerp, die nadien werden gepubliceerd konden in de richtlijncommissie worden ingebracht. De literatuur werd bovendien geupdate door te zoeken in Medline naar nieuw verschenen systematische reviews en RCTs met als onderwerp BPPD in de periode van 2008 t/m 2010.

De richtlijncommissie is voor elke aanbeveling in de Amerikaanse richtlijn nagegaan welke overwegingen naast het wetenschappelijk bewijs zijn gebruikt en of de door de commissie aangedragen studies de aanbeveling zouden kunnen veranderen. Wanneer er consensus was over deze overwegingen en door de commissie aangedragen studies geen ander inzicht opleverden, zijn de aanbevelingen overgenomen. Indien de commissie andere overwegingen (ook) van belang achtte of meende dat de door haar aangedragen studies een (iets) ander licht wierpen op de in de Amerikaanse richtlijn vermelde aanbeveling, zijn de aanbevelingen gemodificeerd.

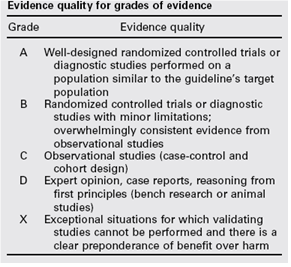

De gradering van de studies in de Amerikaanse richtlijn wijkt af van wat hier te lande gangbaar is. Vanuit het oogpunt van uniformiteit achtte de Nederlandse commissie het wenselijk de classificatie van bewijs c.q. gradering te converteren naar de Nederlandse classificatie. De Amerikaanse classificatie is hieronder afgebeeld in tabel. De corresponderende “Nederlandse” classificatie is in tabel 1.2 opgenomen.

Tabel 1.1: gradering van de studies in de Amerikaanse richtlijn

Tabel 1.2 Relatie tussen Evidence quality for grades of evidence en niveau van conclusie op basis van kwaliteit van bewijs conform Classificatieschema van CBO.

|

Evidence Quality - symbool |

Evidence Quality – omschrijving |

Niveau van conclusie – symbool |

Niveau van conclusie omschrijving |

|

A

|

Well-designed randomized controlled trials or diagnostic studies performed on a population similar to the guideline’s target population |

1 |

Meerdere gerandomiseerde dubbelblinde vergelijkende klinisch onderzoeken van goede kwaliteit van voldoende omvang, of

Meerdere onderzoeken ten opzichte van een referentietest (een ‘gouden standaard’) met tevoren gedefinieerde afkapwaarden en onafhankelijke beoordeling van de resultaten van test en gouden standaard, betreffende een voldoende grote serie van opeenvolgende patiënten die allen de index- en referentietest hebben gehad |

|

B |

Randomized controlled trials or diagnostic studies with minor limitations; overwhelmingly consistent evidence from observational studies |

2 |

Meerdere vergelijkende onderzoeken, maar niet met alle kenmerken als genoemd onder 1 (hieronder valt ook patiënt-controle onderzoek, cohort-onderzoek), of

Meerdere onderzoeken ten opzichte van een referentietest, maar niet met alle kenmerken die onder 1 zijn genoemd. |

|

C |

Observational studies (case-control and cohort design) |

||

|

D |

Expert opinion, case reports, reasoning from first principles (bench research or animal studies) |

3 en 4 |

Niet vergelijkend onderzoek of mening van deskundigen |

In de Amerikaanse richtlijn worden ook de aanbevelingen gegradeerd in termen van ‘strong recommendation’, ‘recommendation’, ‘option’. Hier te lande is graderen van aanbevelingen niet gebruikelijk. Om deze reden zijn in de Nederlandse richtlijn de aanbevelingen niet gegradeerd.

De literatuurzoekstrategie die de Amerikaanse richtlijncommissie heeft gevolgd, staat in bijlage 1 beschreven. Voor het opstellen van de aanbevelingen heeft de Amerikaanse richtlijncommissie gebruik gemaakt van de GuideLine Implementability Appraisal (GLIA) tool. Dit instrument dient om de helderheid van de aanbevelingen te verbeteren en potentiële belemmeringen voor de implementatie te voorspellen. In bijlage 3 wordt een aantal criteria beschreven. Ook de Nederlandse richtlijncommissie heeft deze criteria gehanteerd.

Zoekverantwoording

|

1d Welke diagnostische hulpmiddelen zoals de frenzel bril of de blote oog video kunnen gebruikt worden om BPPD te diagnosticeren? |

Medline (OVID)

2000-aug. 2010-12-20

Engels, Duits, Frans, Nederlands

|

1 "Benign Paroxysmal Position Vertigo".mp. (2) 2 BPPV.mp. (517) 3 ("positional vertigo" or "benign positional vertigo" or "paroxysmal positional vertigo" or "benign paroxysmal positional vertigo").ti,ab. (1042) 4 or/1-3 (1110) 5 limit 4 to yr="2006 -Current" (362) 6 "anterior canal BPPV".mp. (7) 7 "anterior canal".ti,ab. (123) 8 3 and 7 (33) 9 5 and 7 (17) 10 diagnosis.fs. (1658831) 11 diagnos*.ti,ab. (1297107) 12 recogni*.ti,ab. (416096) 13 10 or 11 or 12 (2720808) 14 5 and 13 (234) 15 Vertigo/ (7311) 16 Postural Balance/ (10457) 17 exp Sensation Disorders/ (128222) 18 16 and 17 (1053) 19 15 or 18 (8222) 20 4 or 19 (8405) 21 ((anterior or posterior or lateral) adj5 canal*).ti,ab. (3404) 22 (ASC or PSC or LSC).ti,ab. (6184) 23 exp Semicircular Canals/ (2876) 24 21 or 22 or 23 (11728) 25 20 and 24 (648) 26 limit 25 to (yr="2000 -Current" and (dutch or english or french or german)) (390) 27 13 and 26 (218) 28 frenzel.ti,ab. (50) 35 video*.ti,ab. (55813) 36 28 or 35 (55855) 41 (electronystagmograph* or ENG or videonystagmograph*).ti,ab. or eye movement measurements/ or electronystagmography/ or electrooculography/ or exp Video Recording/ (37172) 43 28 or 41 (37203) 46 (video-oculograph* or VOG).ti,ab. (190) 47 35 or 43 or 46 (78246) 48 20 and 47 (919) 49 limit 48 to (yr="2000 -Current" and (dutch or english or french or german)) (298) 50 13 and 49 (210) 51 limit 50 to "diagnosis (optimized)" (29) 52 limit 50 to (clinical trial, all or clinical trial or comparative study or controlled clinical trial or evaluation studies or government publications or guideline or meta analysis or multicenter study or practice guideline or randomized controlled trial or research support, nih, extramural or research support, nih, intramural or research support, non us gov't or research support, us gov't, non phs or research support, us gov't, phs or "review" or technical report or validation studies) (76) 53 filter systematic reviews (0) 83 limit 49 to "diagnosis (optimized)" (32) 84 52 or 83 (92)

|