Vestibulaire revalidatie als behandeling BPPD

Uitgangsvraag

Is vestibulaire revalidatie geschikt als therapie om patiënten met BPPD te behandelen?

Aanbeveling

Vestibulaire revalidatie is niet primair geïndiceerd bij BPPD.

Overwegingen

- Voordeel: potentieel sneller verlost van symptomen dan met observatie alleen.

- Nadeel: geen ernstige bijwerkingen gezien in de gepubliceerde trials, provocatie van BPPD symptomen door revalidatie oefeningen, mogelijk een tragere oplossing dan repositie manoeuvres.

- Kosten: noodzaak tot herhaalde bezoeken

- Afwegingen: de voordelen wegen niet op tegen de nadelen, wel kan bij ouderen vestibulaire revalidatie worden overwogen, als aanvullende therapie na een repositiemanoeuvre.

- Waarde oordeel: vestibulaire revalidatie is mogelijk beter geschikt als aanvullende therapie dan als primaire behandeling (een subgroep van patiënten met balansstoornissen, centraal zenuwstelsel stoornissen of risico om te vallen, kunnen meer profiteren van vestibulaire revalidatie dan patiënten met uitsluitend BPPD).

- Rol van de voorkeur van de patiënt: aanzienlijk gezien de gezamenlijke beslissing

- Exclusiecriteria: patiënten met fysieke beperkingen

Onderbouwing

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Niveau 2/3 |

Vestibulaire revalidatie in de vorm van adaptatieoefeningen is bij posterieure kanaal BPPD effectief in vergelijking met placebo. Op korte termijn lijkt vestibulaire revalidatie minder effectief dan een repositiemanoeuvre, maar op lange termijn is vestibulaire revalidatie mogelijk net zo effectief als een repositiemanoeuvre. Er zijn aanwijzingen dat, vooral bij ouderen, vestibulaire revalidatie als aanvullende therapie naast een repositiemanoeuvre beter zou beschermen tegen het terugkeren van de klachten dan een repositiemanoeuvre alleen. Er zijn onvoldoende gegevens om de effectiviteit van vestibulaire therapie bij horizontale kanaal BPPD te beoordelen. |

Samenvatting literatuur

The clinician may offer vestibular rehabilitation, either self-administered or with a clinician, for the initial treatment of BPPV. Option based on controlled observational studies and a balance of benefit and harm. Overview of Vestibular Therapy Vestibular rehabilitation is a form of physical therapy designed to promote habituation, adaptation, and compensation for deficits related to a wide variety of balance disorders. It may also be referred to as vestibular habituation, vestibular exercises, or vestibular therapy. There is no single specific protocol for vestibular rehabilitation, but rather a program of therapy is developed on the basis of the underlying diagnosis. Programs can include canalith repositioning exercises, adaptation exercises for gaze stabilization, habituation exercises, substitution training for visual or somatosensory input, postural control exercises, fall prevention training, relaxation training, conditioning exercises, functional skills retraining, and patient and family education (Herdman, et al., 2000) (Telian, et al., 1996) (Whitney, et al., 2000).

With respect to BPPV, vestibular rehabilitation programs most commonly focus on habituation exercises either in formal outpatient therapy programs or with home exercise programs. Vestibular rehabilitation programs may also include PRMs, but repositioning maneuvers will be covered separately in the guideline. Herein, we refer to vestibular rehabilitation as a series of exercises or training maneuvers performed by the patient for the treatment of BPPV with or without direct clinician supervision.

Vestibular rehabilitation habituation exercises were first described by Cawthorne and Cooksey in the 1940s (Cawthorne, et al., 1944). These exercises consist of a series of eye, head, and body movements in a hierarchy of increasing difficulty, which provokes vestibular symptoms. The exercises begin with simple head movements, performed in the sitting or supine position, and progress to complex activities, including walking on slopes and steps with eyes open and closed, and sports activities requiring eye-hand coordination. These exercises theoretically fatigue the vestibular response and force the CNS to compensate by habituation to the stimulus (Norre, et al., 1987a/b). In 1980, Brandt and Daroff (Brandt, et al., 1980) (Brandt, et al., 1994) described home repositioning exercises that involve a sequence of rapid lateral head/trunk tilts repeated serially to promote loosening and ultimately dispersion of debris toward the utricular cavity. In these exercises, the patient starts in a sitting position and moves quickly to the right-side lying position, with the head rotated 45 degrees and facing upward. This position is maintained for 30 seconds after the vertigo stops. The patient then moves rapidly to a left-side lying position, with the head rotated 45 degrees and facing upward. In early work with patients with BPPV, patients repeated these maneuvers moving from the sitting to side-lying position three times a day for 2 weeks while hospitalized and had excellent resolution of BPPV symptoms (Troost, et al., 1992).

Vestibular Rehabilitation as a Treatment of BPPV

Relatively few RCTs and case series have been published regarding the effectiveness of vestibular rehabilitation as the initial therapy for BPPV. In a prospective analysis of 25 consecutive patients with BPPV, Banfield et al (Banfield, et al., 2000) reported that patients demonstrate an excellent short-term response rate of 96 percent subjectively to vestibular rehabilitation treatment with an average of three clinic visits per patient, but the authors noted a significant recurrence rate of BPPV with long-term follow-up (mean follow-up 3.8 years). The authors cited one advantage of vestibular rehabilitation: the capability of patients to be self-reliant in their ability to return to habituation exercises should symptoms recur. In a controlled trial of 60 patients with BPPV comparing a PRM, vestibular rehabilitation exercises and no treatment, vestibular rehabilitation provided better resolution of vertigo compared with no treatment (Steenerson, et al., 1996). The PRM arm demonstrated resolution of symptoms with fewer treatments than those required for vestibular rehabilitation, although the relative improvements at 3-month follow-up were comparable.

Several studies have compared vestibular rehabilitation exercises to particle rehabilitation maneuvers in the treatment of posterior canal BPPV. In an RCT of 124 patients randomized to CRP, modified liberatory maneuver, sham maneuver, Brandt-Daroff exercises, and vestibular habituation exercises by Cohen, repositioning maneuvers were more effective than Brandt-Daroff exercises or habituation exercises (Cohen et.al., 2005). Both types of vestibular rehabilitation treatments, however, were individually more effective than a sham intervention (Cohen, et al., 2005)(Hillier, 2007). Soto Varela et al (Soto Varela, et al., 2001) comparatively analyzed a total of 106 BPPV patients randomly assigned to receive Brandt-Daroff habituation exercises, the Semont maneuver, or the Epley maneuver. At the 1-week follow-up, similar cure rates were obtained with the Semont and Epley maneuvers (74% and 71%, respectively), both cure rates being significantly higher than that obtained with Brandt- Daroff exercises (24%). At 3-month follow-up, the cure rate for the Brandt-Daroff exercises increased significantly to 62 percent, although the rate was still lower than that of PRMs. Other studies have demonstrated similar results for vestibular rehabilitation in BPPV (Furman, 1999) (Toledo, 2000). In a double blind RCT control study Chang WC et al. demonstrated that additional exercise training, which emphasizes vestibular stimulation, can improve balance ability and functional gait performance among patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo of the posterior semicircular canal who had already undergone the canalith repositioning manoeuvre (Chang, et al., 2008).

Vestibular rehabilitation is thought to improve long-term outcomes for BPPV. Although data are mixed, a few studies have indicated that use of vestibular rehabilitation may decrease recurrence rates for BPPV (Angeli, et al., 2003) (Helminski, et al., 2005). This protective effect against recurrence of vestibular rehabilitation may be more pronounced in the elderly (Angeli, et al., 2003). Several prospective studies have demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of vestibular rehabilitation for unilateral peripheral vestibular disorders; the results are summarized in a recent Cochrane collaboration report (Hillier, et al., 2007). Among 21 included randomized trials, there were no reports of adverse effects due to vestibular rehabilitation therapy. Current published evidence is inadequate to indicate superiority for one form of vestibular rehabilitation vs another. There is also not enough evidence to favor formal outpatient vestibular therapy performed with a clinician over independent home therapy (Kammerlind, et al., 2005).

In summary, with respect to posterior canal BPPV, vestibular rehabilitation demonstrates superior treatment outcomes compared with placebo. In short-term evaluation, vestibular rehabilitation is less effective at producing complete symptom resolution than PRMs. With longer-term follow-up, however, its effectiveness approaches that of PRMs. Insufficient data exist concerning the response of lateral canal BPPV to vestibular therapy; this area needs further research.

Cost considerations may become important if repeated visits for clinician-supervised therapy are required as opposed to initial patient instruction followed by home-based therapy. Patients with certain comorbidities may not be appropriate candidates for vestibular rehabilitation or may need specialized, individually tailored vestibular rehabilitation protocols. Examples of such comorbidities include cervical stenosis, Down syndrome, severe rheumatoid arthritis, cervical radiculopathies, Paget’s disease, morbid obesity, ankylosing spondylitis, low back dysfunction, and spinal cord injuries. On the other hand, patients with preexisting otological or neurological disorders may derive more benefit from vestibular rehabilitation as a treatment for BPPV.

Referenties

- Angeli, S.I., Hawley, R., Gomez, O. (2003). Systematic approach to benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in the elderly. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 128, 719-25.

- Banfield, G.K., Wood, C., Knight, J. (2000). Does vestibular habituation still have a place in the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo?. J Laryngol Otol, 114, 501-5.

- Brandt, T., Steddin, S., Daroff, R.B. (1994). Therapy for benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo, revisited. Neurology, 44, 796-800.

- Brandt, T., Daroff, R.B. (1980). Physical therapy for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Arch Otolaryngol, 106, 484-5.

- Cawthorne, T. (1944). The physiologic basis for head exercises. J Chart Soc Physiother, 0, 106-7.

- Chang, W.C., Yang, Y.R., Hsu, L.C., Chern, C.M., Wang, R.Y. (2008). Balance improvement in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Clinical rehabilitation Apr, 22 (4), 338-47.

- Cohen, H.S., Kimball, KT. (2005). Effectiveness of treatments for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo of the posterior canal. Otol Neurotol, 26, 1034-40.

- Furman, J.M., Cass, S.P. (1999). Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. N Engl J Med, 341, 1590-6.

- Helminski, J.O., Janssen, I., Kotaspouikis, D., et al. (2005). Strategies to prevent recurrence of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 131, 344-8.

- Herdman, S.J., Blatt, P.J., Schubert, M.C. (2000). Vestibular rehabilitation of patients with vestibular hypofunction or with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Curr Opin Neurol, 13, 39-43.

- Hillier, S.L., Hollohan, V. (2007). Vestibular rehabilitation for unilateral peripheral vestibular dysfunction. Cochrane Database Syst, 0, CD005397-.

- Kammerlind, A.S., Ledin, T.E., Odkvist, L.M., et al. (2005). Effects of home training and additional physical therapy on recovery after acute unilateral vestibular loss—a randomized study. Clin Rehabil, 19, 54-62.

- Norré, M.E., Forrez, G., Beckers, A. (1987). Vestibular habituation training and posturography in benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec., 49 (1), 22-5.

- Norré, M.E., Beckers, A. (1987). Exercise treatment for paroxysmal positional vertigo: comparison of two types of exercises. Arch Otorhinolaryngol, 244 (5), 291-4.

- Steenerson, R.L., Cronin, G.W. (1996). Comparison of the canalith repositioning procedure and vestibular habituation training in forty patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 114, 61-4.

- Soto Varela, A., Bartual Magro, J., Santos Perez, S., et al. (2001). Benign paroxysmal vertigo: a comparative prospective study of the efficacy of Brandt and Daroff exercises, Semont and Epley maneuver. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord), 122, 179-83.

- Telian, S.A., Shepard, N.T. (1996). Update on vestibular rehabilitation therapy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am, 29, 359-71.

- Toledo, H., Cortes, M.L., Pane, C., et al. (2000). Semont maneuver and vestibular rehabilitation exercises in the treatment of benign paroxysmal postural vertigo. A comparative study. Neurologia, 15, 152-7.

- Troost, B.T., Patton, J.M. (1992). Exercise therapy for positional vertigo. Neurology, 42, 1441-4.

- Whitney, S.L., Rossi, M.M. (2000). Efficacy of vestibular rehabilitation. Otolaryngol Clin North Am, 33, 659-72.

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 20-08-2013

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-02-2020

De tekst van deze module is opgesteld tijdens de richtlijnontwikkeling in 2010 door de oorspronkelijke richtlijnwerkgroep (zie Samenstelling werkgroep). De module is opnieuw beoordeeld en nog actueel bevonden door de werkgroep samengesteld voor de richtlijnherziening in 2019 (zie samenstelling huidige werkgroep). Uiterlijk in 2024 bepaalt het bestuur van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Keel-Neus-Oorheelkunde en Heelkunde van het Hoofd-Halsgebied of de richtlijnmodule nog actueel is.

Algemene gegevens

Met ondersteuning van de Orde van Medisch Specialisten. De richtlijnontwikkeling werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De richtlijn betreft een adaptatie van:

Clinical practice guideline: Benigne Paroxysmale Positionele Duizeligheid.

De Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery foundation ‘Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’ (Bhattacharayya, et al., 2008) vormde het uitgangspunt van de onderhavige richtlijn. Daarnaast werd de Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of neurology, gericht op de behandeling van BPPD, gebruikt ter aanvulling (Fife, et al., 2008), alsmede de discussies en richtlijnen van de Standaardisatie commissie van de Barany Society (Reykjavik, et al., 2010, www.baranysociety.nl).

Doel en doelgroep

De primaire doelstellingen van deze richtlijn zijn:

- De kwaliteit van de zorg te verbeteren door middel van een accurate en snelle diagnose van BPPD.

- Voorkomen van onnodig gebruik van medicijnen.

- Doelgericht gebruik van aanvullend onderzoek.

- Stimuleren van het gebruik van repositiemanoeuvres als therapie voor BPPD.

Secundaire doelstellingen zijn: beperking van de kosten van diagnose en behandeling van BPPD, vermindering van het aantal artsenbezoeken, en verbetering van de kwaliteit van leven. Het grote aantal patiënten met BPPD en de verscheidenheid aan diagnostische en therapeutische interventies voor BPPD maakt dit een geschikt onderwerp voor een evidence-based richtlijn.

De Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery foundation ‘Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’ (Bhattacharayya, et al., 2008) vormde het uitgangspunt van de onderhavige richtlijn. Daarnaast werd de Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of neurology, gericht op de behandeling van BPPD, gebruikt ter aanvulling (Fife, et al., 2008), alsmede de discussies en richtlijnen van de Standaardisatie commissie van de Barany Society (Reykjavik, et al., 2010, www.baranysociety.nl)). Onze doelstelling was om deze multidisciplinaire richtlijn te adapteren aan de Nederlandse situatie met behulp van Nederlandse input, waarbij de aanbevelingen rekening houden met wetenschappelijk bewijs en zich richten op harm-benefit balans, en expert consensus om de gaten in wetenschappelijk bewijs op te vullen. Deze specifieke aanbevelingen kunnen dan gebruikt worden om indicatoren te ontwikkelen en te gebruiken voor kwaliteitsverbetering.

Deze richtlijn is opgesteld voor KNO-artsen en neurologen die in hun klinische praktijk in aanraking komen met BPPD. De richtlijn is toepasbaar in iedere setting waar BPPD gediagnosticeerd en behandeld wordt.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de module is in 2018 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met BPPD.

De werkgroepleden zijn door hun beroepsverenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname. De werkgroep is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze module.

Samenstelling huidige werkgroep:

- Dr. Tj.D. (Tjasse) Bruintjes, KNO-arts, Gelre Ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn, NVKNO (voorzitter)

- Dr. R.B. (Roeland) van Leeuwen, neuroloog, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn, NVN

- Dr. R. (Raymond) van de Berg, KNO-arts/vestibuloloog, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht, NVKNO

- Dr. M. (Marloes) Thoomes-de Graaf, fysiotherapeut/manueel therapeut/klinisch epidemioloog, Fysio-Experts, Hazerswoude, KNGF en NVMT

- R.A.K. (Sandra) Rutgers, arts, MPH en voorzitter Commissie Ménière Stichting Hoormij, Houten, Stichting Hoormij

Met ondersteuning van:

- D. (Dieuwke) Leereveld, MSc., senior adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. M. (Monique) Wessels, informatiespecialist Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Samenstelling oorspronkelijke werkgroep (2010):

- dr. Tj.D. Bruintjes (voorzitter), KNO-arts, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn

- prof. dr. H. Kingma, klinisch fysicus/vestibuloloog, Maastricht Universitair Medisch Centrum en Technische Universiteit Eindhoven

- dr. D.J.M. Mateijsen, KNO-arts, Catharina ziekenhuis, Eindhoven

- dr. R.B. van Leeuwen, neuroloog, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn

- dr. ir. T van Barneveld klinisch epidemioloog, Orde van Medisch specialisten (adviseur)

- dr. M.L. Molag, Orde van Medisch specialisten (adviseur)

Belangenverklaringen

De werkgroepleden hebben onafhankelijk gehandeld en waren vrij van financiële of zakelijke belangen betreffende het onderwerp van de richtlijn.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

De Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery foundation ‘Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’ (Bhattacharayya, et al., 2008) vormde het uitgangspunt van de onderhavige richtlijn. Daarnaast werd de Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of neurology gebruikt (Fife, et al., 2008). Dit betekent dat de Nederlandse richtlijncommissie de studies, de beoordeling & gradering ervan en de begeleidende tekst heeft overgenomen. Studies, relevant voor dit onderwerp, die nadien werden gepubliceerd konden in de richtlijncommissie worden ingebracht. De literatuur werd bovendien geupdate door te zoeken in Medline naar nieuw verschenen systematische reviews en RCTs met als onderwerp BPPD in de periode van 2008 t/m 2010.

De richtlijncommissie is voor elke aanbeveling in de Amerikaanse richtlijn nagegaan welke overwegingen naast het wetenschappelijk bewijs zijn gebruikt en of de door de commissie aangedragen studies de aanbeveling zouden kunnen veranderen. Wanneer er consensus was over deze overwegingen en door de commissie aangedragen studies geen ander inzicht opleverden, zijn de aanbevelingen overgenomen. Indien de commissie andere overwegingen (ook) van belang achtte of meende dat de door haar aangedragen studies een (iets) ander licht wierpen op de in de Amerikaanse richtlijn vermelde aanbeveling, zijn de aanbevelingen gemodificeerd.

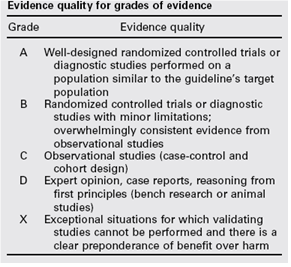

De gradering van de studies in de Amerikaanse richtlijn wijkt af van wat hier te lande gangbaar is. Vanuit het oogpunt van uniformiteit achtte de Nederlandse commissie het wenselijk de classificatie van bewijs c.q. gradering te converteren naar de Nederlandse classificatie. De Amerikaanse classificatie is hieronder afgebeeld in tabel. De corresponderende “Nederlandse” classificatie is in tabel 1.2 opgenomen.

Tabel 1.1: gradering van de studies in de Amerikaanse richtlijn

Tabel 1.2 Relatie tussen Evidence quality for grades of evidence en niveau van conclusie op basis van kwaliteit van bewijs conform Classificatieschema van CBO.

|

Evidence Quality - symbool |

Evidence Quality – omschrijving |

Niveau van conclusie – symbool |

Niveau van conclusie omschrijving |

|

A

|

Well-designed randomized controlled trials or diagnostic studies performed on a population similar to the guideline’s target population |

1 |

Meerdere gerandomiseerde dubbelblinde vergelijkende klinisch onderzoeken van goede kwaliteit van voldoende omvang, of

Meerdere onderzoeken ten opzichte van een referentietest (een ‘gouden standaard’) met tevoren gedefinieerde afkapwaarden en onafhankelijke beoordeling van de resultaten van test en gouden standaard, betreffende een voldoende grote serie van opeenvolgende patiënten die allen de index- en referentietest hebben gehad |

|

B |

Randomized controlled trials or diagnostic studies with minor limitations; overwhelmingly consistent evidence from observational studies |

2 |

Meerdere vergelijkende onderzoeken, maar niet met alle kenmerken als genoemd onder 1 (hieronder valt ook patiënt-controle onderzoek, cohort-onderzoek), of

Meerdere onderzoeken ten opzichte van een referentietest, maar niet met alle kenmerken die onder 1 zijn genoemd. |

|

C |

Observational studies (case-control and cohort design) |

||

|

D |

Expert opinion, case reports, reasoning from first principles (bench research or animal studies) |

3 en 4 |

Niet vergelijkend onderzoek of mening van deskundigen |

In de Amerikaanse richtlijn worden ook de aanbevelingen gegradeerd in termen van ‘strong recommendation’, ‘recommendation’, ‘option’. Hier te lande is graderen van aanbevelingen niet gebruikelijk. Om deze reden zijn in de Nederlandse richtlijn de aanbevelingen niet gegradeerd.

De literatuurzoekstrategie die de Amerikaanse richtlijncommissie heeft gevolgd, staat in bijlage 1 beschreven. Voor het opstellen van de aanbevelingen heeft de Amerikaanse richtlijncommissie gebruik gemaakt van de GuideLine Implementability Appraisal (GLIA) tool. Dit instrument dient om de helderheid van de aanbevelingen te verbeteren en potentiële belemmeringen voor de implementatie te voorspellen. In bijlage 3 wordt een aantal criteria beschreven. Ook de Nederlandse richtlijncommissie heeft deze criteria gehanteerd.