Medicatie als behandeling BPPD

Uitgangsvraag

Zijn medicijnen geschikt als therapie om patiënten met BPPD te behandelen?

Aanbeveling

Er is geen indicatie om patiënten met BPPD medicatie voor te schrijven.

Overwegingen

- Voordeel: patiënt krijgt geen onterechte medicatie

- Nadeel: geen

- Kosten: voordelig om geen medicatie voor te schrijven

- Afweging: voordelen wegen op tegen de nadelen. Kortdurend gebruik van vestibulosuppressieve medicatie en/of anti-emetica kan soms wel zinvol zijn om een Dix-Hallpikemanoeuvre of repositiemanoeuvre te kunnen uitvoeren teneinde misselijkheid en/of braken te voorkomen.

- Waarde oordeel: Schade door ineffectieve behandeling wordt voorkomen.

- Rol van de voorkeur van de patiënt: is minimaal.

- Exclusiecriteria: Patiënten die profylaxe voor Dix-Hallpikemanoeuvre en/of repositie manoeuvre nodig hebben.

Onderbouwing

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Niveau 3 |

Medicatie is niet effectief als behandeling van BPPD.

|

Samenvatting literatuur

The symptoms of vertigo due to many different underlying etiologies are commonly treated with medications. Clinicians may prescribe pharmacological management to either 1) reduce the spinning sensations of vertigo specifically and/or 2) to reduce the accompanying motion sickness symptoms. These motion sickness symptoms include a constellation of autonomic or vegetative symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, which can accompany the vertigo. Such pharmacological therapies for vertigo may be broadly termed vestibular suppressant medications (Hain, et al., 2003) (Hain, et al., 2005). Several categories of vestibular suppressant medications are in common use. Of these, the most commonly used are benzodiazepines and antihistamines. Benzodiazepines, such as diazepam and clonazepam, have anxiolytic, sedative, muscle relaxant, and anticonvulsant properties derived from potentiating the inhibitory effect of the gamma-amino butyric acid system. In prolonged dizziness, these medications can reduce the subjective sensation of spinning, but they also interfere with central compensation in peripheral vestibular conditions. Antihistamines, on the other hand, appear to have a suppressive effect on the central emetic center to relieve the nausea and vomiting associated with motion sickness. Common examples of antihistamines used to treat symptoms of vertigo and/or associated motion sickness include meclizine and diphenhydramine. Other medications that are often used for motion sickness include promethazine, which is a phenothiazine with antihistamine properties, and ondansetron, which is a serotonin-5-hydroxytryptamine- 3 antagonist. Finally, anticholinergic medications such as scopolamine block acetylcholine, which is a widespread CNS transmitter, and help with motion sickness by reducing neural mismatching (Hain et al.,., 2003) (Hain, et al., 2005).

There is no evidence in the literature to suggest that any of these vestibular suppressant medications are effective as a definitive, primary treatment for BPPD, or as a substitute for repositioning maneuvers (Frohman, et al., 2003) (Hain, et al., 2003) (Carlow, et al., 1986) (Cesarani, et al., 2004) (Fujino, et al., 1994). Exercise was found to be a better treatment choice than medication (betahistin) and may be preferable for patients with persistent or chronic vertigo (Kulcu, et al., 2008).Some studies show a resolution of BPPD over time with medications, but these studies follow patients for the period of time in which spontaneous resolution would occur (Woodworth, et al., 2004) (Salvinelli, et al., 2004) (Itaya, et al., 1997) (McClure, et al., 1980). In one double- blind controlled trial by McClure and Willet (McClure, et al., 1980) comparing diazepam, lorazepam, and placebo, all groups showed a gradual decline in symptoms with no additional relief in the drug treatment arms. In a small study, Itaya et al (Itaya, et al., 1997) compared PRMs to a medication-alone treatment arm and found that PRMs had substantially higher treatment responses (78.6%-93.3% improvement) compared with medication alone (30.8% improvement) at 2 weeks follow-up. These data reinforced previous data from Fujino et al (Fujino, et al., 1994) that also indicated superiority of vestibular training for BPPD over medication use alone. A lack of benefit from vestibular suppressants and their inferiority to PRMs indicate that clinicians should not substitute pharmacological treatment of symptoms associated with BPPD in lieu of other more effective treatment modalities.

Conversely, vestibular suppressant medications have the potential for significant harm. All of these medications may produce drowsiness, cognitive deficits, and interference with driving vehicles or operating machinery (Ancelin, et al., 2006) (Hebert, et al., 2007) (Barbone, et al., 1998) (Engeland, et al., 2007) (Jauregui, et al., 2006). Medications used for vestibular suppression, especially psychotropic medications such as benzodiazepines, are a significant independent risk factor for falls (Hartikainen, et al., 2007). The risk of falls increases in patients taking multiple medications and with the use of medications such as antidepressants (Lawson, et al., 2005) (Hien, et al., 2005). The potential for polypharmacy when adding vestibular suppressants further exposes the elderly to additional risk (Landi, et al., 2007). Educational programs to modify practitioner’s use of such medications can result in a reduction of falls (Pit, et al., 2007).

There are other potential harmful side effects of vestibular suppressants. Benzodiazepines and antihistamines interfere with central compensation for a vestibular injury (Hanley, et al., 1998) [Baloh, 1998] (Baloh, et al., 1998). The use of vestibular suppressants may obscure the findings on the Dix-Hallpike maneuvers. In addition, there is evidence of additional potential harm from the antihistamine class of medications on cognitive functioning (Ancelin, et al., 2006), and on gastrointestinal motility, urinary retention, vision, and dry mouth in the elderly (Rudolph, et al., 2008).

Another type of medication, betahistine dihydrochloride is an extensively applied and studied drug in the treatment of vertigo as well, especially in case of Meniere Disease. Betahistine appears to be a weak H1 agonist (release of Ca2++), a weak H2 agonist (synthesis cyclic AMP) and a strong H3 antagonist (release of histamine)(Timmerman, et al., 1989). The action upon the H3 auto-receptor might explain why a relatively low concentration of betahistine could effectively modify neurotransmission in the brain (Tighilet, et al., 1995). Betahistine also results in a dose-dependent inhibition of polysynaptic neurons in the lateral vestibular nuclei (KawabataA). Recently it was shown that betahistine fastens the central compensation process after labyrinthectomy in cats (Tighilet, et al., 1995) and after neurectomy in men (Redon et al., 2010), In animals intra-labyrinthine blood flow and oxygenation of sensory tissue is increased by intake of betahistine (Meyer et al., 1994, Laurikainen et al., 1993). In one study, the treatment of patients with BPPV was found not to be effective in BPPD (Kulcu, et al., 2008).

In summary, vestibular medications are not recommended for treatment of BPPD, other than for the short-term management of vegetative symptoms such as nausea or vomiting in a severely symptomatic patient. Examples of potential short-term uses include patients who are severely symptomatic yet refuse therapy or patients who become severely symptomatic after a PRM. Antiemetics may also be considered for prophylaxis for patients who have previously manifested severe nausea and/or vomiting with the Dix-Hallpike maneuvers and in whom a PRM is planned. If prescribed for these very specific indications, clinicians should also provide counseling that the rates of cognitive dysfunction, falls, drug interactions, and machinery and driving accidents increase with use of vestibular suppressants.

Referenties

- Ancelin, M.L., Artero, S., Portet, F., et al. (2006). Non-degenerative mild cognitive impairment in elderly people and use of anticholinergic drugs: longitudinal cohort study. BMJ, 332, 455-9.

- Baloh, R.W. (1998). Vertigo. Lancet, 352, 1841-6.

- Baloh, R.W. (1998). Dizziness: neurological emergencies. Neurol Clin, 16, 305-21.

- Barbone, F., McMahon, A.D., Davey, P.G., et al. (1998). Association of roadtraffic accidents with benzodiazepine use. Lancet, 352, 1331-6.

- Carlow, T.J. (1986). Medical treatment of nystagmus and ocular motor disorders. Int Ophthalmol Clin, 26, 251-64.

- Cesarani, A., Alpini, D., Monti, B., et al. (2004). The treatment of acute vertigo. Neurol Sci, 25, S26-S30.

- Engeland, A., Skurtveit, S., Morland, J. (2007). Risk of road traffic accidents associated with the prescription of drugs: a registry-based cohort study. Ann Epidemiol, 17, 597-602.

- Frohman, E.M., Kramer, P.D., Dewey, R.B., et al. (2003). Benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo in multiple sclerosis: diagnosis, pathophysiology and therapeutic techniques. Mult Scler, 9, 250-5.

- Fujino, A., Tokumasu, K., Yosio, S., et al. (1994). Vestibular training for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Its efficacy in comparison with antivertigo drugs. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 120, 497-504.

- Hain, T.C., Yacovino, D. (2005). Pharmacologic treatment of persons with dizziness. Neurol Clin, 23, 831-53.

- Hain, T.C., Uddin, M. (2003). Pharmacological treatment of vertigo. CNS Drugs, 17, 85-100.

- Hanley, K., O’Dowd, T., Considine, N. (2001). A systematic review of vertigo in primary care. Br J Gen Pract, 51, 666-71.

- Hartikainen, S., Lonnroos, E., Louhivuori, K. (2007). Medication as a risk factor for falls: critical systematic review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 62, 1172-81.

- Hebert, C., Delaney, J.A., Hemmelgarn, B., et al. (2007). Benzodiazepines and elderly drivers: a comparison of pharmacoepidemiological study designs. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf, 16, 845-9.

- Hien le, T.T., Cumming, R.G., Cameron, I.D., et al. (2005). Atypical antipsychotic medications and risk of falls in residents of aged care facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc, 53, 1290-5.

- Itaya, T., Yamamoto, E., Kitano, H., et al. (1997). Comparison of effectiveness of maneuvers and medication in the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec, 59, 155-8.

- Jauregui, I., Mullol, J., Bartra, J., et al. (2006). H1 antihistamines: psychomotor performance and driving. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol, 16, 37-44.

- Kulcu, D.G., Yanik, B., Boynukalin, S., Kurtais, Y. (2008). Efficacy of a home-based exercise program on benign paroxysmal positional vertigo compared with betahistine. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Jun, 37 (3), 373-9.

- Landi, F., Russo, A., Liperoti, R., et al. (2007). Anticholinergic drugs and physical function among frail elderly population. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 81, 235-41.

- Laurikainen, E.A., Miller, J.M., Quirk, W.S., Kallinen, J., Ren, T., Nuttall, A.L., Grenman, R., Virolainen, E. (1993). Betahistine induced vascular effects in the rat cochlea. Am J Otol. Jan, 14 (1), 24-30.

- Lawson, J., Johnson, I., Bamiou, D.E., et al. (2005). Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: clinical characteristics of dizzy patients referred to a Falls and Syncope Unit. QJM, 98, 357-64.

- McClure, J.A., Willett, J.M. (1980). Lorazepam and diazepam in the treatment of benign paroxysmal vertigo. J Otolaryngol, 9, 472-7.

- Meyer, P., Schmidt, R., Grutzmacher, W., Gehrig, W. (1994). Inner ear blood flow with betahistine an animal experiment study. Laryngorhinootologie, 73 (3), 153-6.

- Pit, S.W., Byles, J.E., Henry, D.A., et al. (2007). A Quality Use of Medicines program for general practitioners and older people: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Med J Aust, 187, 23-30.

- Redon, C., Lopez, C., Bernard-Demanze, L., Dumitrescu, M., Magnan, J., Lacour, M., Borel, L. (2010). Betahistine Treatment Improves the Recovery of Static Symptoms in Patients With Unilateral Vestibular Loss. J Clin Pharmacol, 0, X-.

- Rudolph, J.L., Salow, M.J., Angelini, M.C., et al. (2008). The anticholinergic risk scale and anticholinergic adverse effects in older persons. Arch Intern Med, 168, 508-13.

- Salvinelli, F., Trivelli, M., Casale, M., et al. (2004). Treatment of benign positional vertigo in the elderly: a randomized trial. Laryngoscope, 114, 827-31.

- Tighilet, B., Leonard, J., Lacour, M. (1995). Betahistine dihydrochlo¬ride treatment facilita¬tes vestibular compensation in the cat. J Vestib Res, 5 (1), 53-66.

- Timmerman, H. (1989). The Histamine H3-receptor, its function and ligands. In van der Goot, H., Pallos, L., Timmerman, H., eds. Trends in medicinal chemistry '88. Amsterda, 0, 351-63.

- Woodworth, B.A., Gillespie, M.B., Lambert, P.R. (2004). The canalith repositioning procedure for benign positional vertigo: a meta-analysis. Laryngoscope, 114, 1143-6.

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 20-08-2013

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-02-2020

De tekst van deze module is opgesteld tijdens de richtlijnontwikkeling in 2010 door de oorspronkelijke richtlijnwerkgroep (zie Samenstelling werkgroep). De module is opnieuw beoordeeld en nog actueel bevonden door de werkgroep samengesteld voor de richtlijnherziening in 2019 (zie samenstelling huidige werkgroep). Uiterlijk in 2024 bepaalt het bestuur van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Keel-Neus-Oorheelkunde en Heelkunde van het Hoofd-Halsgebied of de richtlijnmodule nog actueel is.

Algemene gegevens

Met ondersteuning van de Orde van Medisch Specialisten. De richtlijnontwikkeling werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De richtlijn betreft een adaptatie van:

Clinical practice guideline: Benigne Paroxysmale Positionele Duizeligheid.

De Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery foundation ‘Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’ (Bhattacharayya, et al., 2008) vormde het uitgangspunt van de onderhavige richtlijn. Daarnaast werd de Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of neurology, gericht op de behandeling van BPPD, gebruikt ter aanvulling (Fife, et al., 2008), alsmede de discussies en richtlijnen van de Standaardisatie commissie van de Barany Society (Reykjavik, et al., 2010, www.baranysociety.nl).

Doel en doelgroep

De primaire doelstellingen van deze richtlijn zijn:

- De kwaliteit van de zorg te verbeteren door middel van een accurate en snelle diagnose van BPPD.

- Voorkomen van onnodig gebruik van medicijnen.

- Doelgericht gebruik van aanvullend onderzoek.

- Stimuleren van het gebruik van repositiemanoeuvres als therapie voor BPPD.

Secundaire doelstellingen zijn: beperking van de kosten van diagnose en behandeling van BPPD, vermindering van het aantal artsenbezoeken, en verbetering van de kwaliteit van leven. Het grote aantal patiënten met BPPD en de verscheidenheid aan diagnostische en therapeutische interventies voor BPPD maakt dit een geschikt onderwerp voor een evidence-based richtlijn.

De Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery foundation ‘Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’ (Bhattacharayya, et al., 2008) vormde het uitgangspunt van de onderhavige richtlijn. Daarnaast werd de Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of neurology, gericht op de behandeling van BPPD, gebruikt ter aanvulling (Fife, et al., 2008), alsmede de discussies en richtlijnen van de Standaardisatie commissie van de Barany Society (Reykjavik, et al., 2010, www.baranysociety.nl)). Onze doelstelling was om deze multidisciplinaire richtlijn te adapteren aan de Nederlandse situatie met behulp van Nederlandse input, waarbij de aanbevelingen rekening houden met wetenschappelijk bewijs en zich richten op harm-benefit balans, en expert consensus om de gaten in wetenschappelijk bewijs op te vullen. Deze specifieke aanbevelingen kunnen dan gebruikt worden om indicatoren te ontwikkelen en te gebruiken voor kwaliteitsverbetering.

Deze richtlijn is opgesteld voor KNO-artsen en neurologen die in hun klinische praktijk in aanraking komen met BPPD. De richtlijn is toepasbaar in iedere setting waar BPPD gediagnosticeerd en behandeld wordt.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de module is in 2018 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met BPPD.

De werkgroepleden zijn door hun beroepsverenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname. De werkgroep is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze module.

Samenstelling huidige werkgroep:

- Dr. Tj.D. (Tjasse) Bruintjes, KNO-arts, Gelre Ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn, NVKNO (voorzitter)

- Dr. R.B. (Roeland) van Leeuwen, neuroloog, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn, NVN

- Dr. R. (Raymond) van de Berg, KNO-arts/vestibuloloog, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht, NVKNO

- Dr. M. (Marloes) Thoomes-de Graaf, fysiotherapeut/manueel therapeut/klinisch epidemioloog, Fysio-Experts, Hazerswoude, KNGF en NVMT

- R.A.K. (Sandra) Rutgers, arts, MPH en voorzitter Commissie Ménière Stichting Hoormij, Houten, Stichting Hoormij

Met ondersteuning van:

- D. (Dieuwke) Leereveld, MSc., senior adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. M. (Monique) Wessels, informatiespecialist Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Samenstelling oorspronkelijke werkgroep (2010):

- dr. Tj.D. Bruintjes (voorzitter), KNO-arts, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn

- prof. dr. H. Kingma, klinisch fysicus/vestibuloloog, Maastricht Universitair Medisch Centrum en Technische Universiteit Eindhoven

- dr. D.J.M. Mateijsen, KNO-arts, Catharina ziekenhuis, Eindhoven

- dr. R.B. van Leeuwen, neuroloog, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn

- dr. ir. T van Barneveld klinisch epidemioloog, Orde van Medisch specialisten (adviseur)

- dr. M.L. Molag, Orde van Medisch specialisten (adviseur)

Belangenverklaringen

De werkgroepleden hebben onafhankelijk gehandeld en waren vrij van financiële of zakelijke belangen betreffende het onderwerp van de richtlijn.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

De Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery foundation ‘Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’ (Bhattacharayya, et al., 2008) vormde het uitgangspunt van de onderhavige richtlijn. Daarnaast werd de Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of neurology gebruikt (Fife, et al., 2008). Dit betekent dat de Nederlandse richtlijncommissie de studies, de beoordeling & gradering ervan en de begeleidende tekst heeft overgenomen. Studies, relevant voor dit onderwerp, die nadien werden gepubliceerd konden in de richtlijncommissie worden ingebracht. De literatuur werd bovendien geupdate door te zoeken in Medline naar nieuw verschenen systematische reviews en RCTs met als onderwerp BPPD in de periode van 2008 t/m 2010.

De richtlijncommissie is voor elke aanbeveling in de Amerikaanse richtlijn nagegaan welke overwegingen naast het wetenschappelijk bewijs zijn gebruikt en of de door de commissie aangedragen studies de aanbeveling zouden kunnen veranderen. Wanneer er consensus was over deze overwegingen en door de commissie aangedragen studies geen ander inzicht opleverden, zijn de aanbevelingen overgenomen. Indien de commissie andere overwegingen (ook) van belang achtte of meende dat de door haar aangedragen studies een (iets) ander licht wierpen op de in de Amerikaanse richtlijn vermelde aanbeveling, zijn de aanbevelingen gemodificeerd.

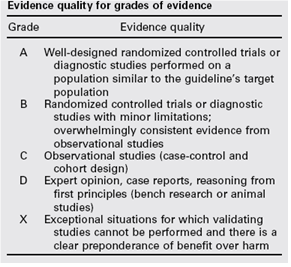

De gradering van de studies in de Amerikaanse richtlijn wijkt af van wat hier te lande gangbaar is. Vanuit het oogpunt van uniformiteit achtte de Nederlandse commissie het wenselijk de classificatie van bewijs c.q. gradering te converteren naar de Nederlandse classificatie. De Amerikaanse classificatie is hieronder afgebeeld in tabel. De corresponderende “Nederlandse” classificatie is in tabel 1.2 opgenomen.

Tabel 1.1: gradering van de studies in de Amerikaanse richtlijn

Tabel 1.2 Relatie tussen Evidence quality for grades of evidence en niveau van conclusie op basis van kwaliteit van bewijs conform Classificatieschema van CBO.

|

Evidence Quality - symbool |

Evidence Quality – omschrijving |

Niveau van conclusie – symbool |

Niveau van conclusie omschrijving |

|

A

|

Well-designed randomized controlled trials or diagnostic studies performed on a population similar to the guideline’s target population |

1 |

Meerdere gerandomiseerde dubbelblinde vergelijkende klinisch onderzoeken van goede kwaliteit van voldoende omvang, of

Meerdere onderzoeken ten opzichte van een referentietest (een ‘gouden standaard’) met tevoren gedefinieerde afkapwaarden en onafhankelijke beoordeling van de resultaten van test en gouden standaard, betreffende een voldoende grote serie van opeenvolgende patiënten die allen de index- en referentietest hebben gehad |

|

B |

Randomized controlled trials or diagnostic studies with minor limitations; overwhelmingly consistent evidence from observational studies |

2 |

Meerdere vergelijkende onderzoeken, maar niet met alle kenmerken als genoemd onder 1 (hieronder valt ook patiënt-controle onderzoek, cohort-onderzoek), of

Meerdere onderzoeken ten opzichte van een referentietest, maar niet met alle kenmerken die onder 1 zijn genoemd. |

|

C |

Observational studies (case-control and cohort design) |

||

|

D |

Expert opinion, case reports, reasoning from first principles (bench research or animal studies) |

3 en 4 |

Niet vergelijkend onderzoek of mening van deskundigen |

In de Amerikaanse richtlijn worden ook de aanbevelingen gegradeerd in termen van ‘strong recommendation’, ‘recommendation’, ‘option’. Hier te lande is graderen van aanbevelingen niet gebruikelijk. Om deze reden zijn in de Nederlandse richtlijn de aanbevelingen niet gegradeerd.

De literatuurzoekstrategie die de Amerikaanse richtlijncommissie heeft gevolgd, staat in bijlage 1 beschreven. Voor het opstellen van de aanbevelingen heeft de Amerikaanse richtlijncommissie gebruik gemaakt van de GuideLine Implementability Appraisal (GLIA) tool. Dit instrument dient om de helderheid van de aanbevelingen te verbeteren en potentiële belemmeringen voor de implementatie te voorspellen. In bijlage 3 wordt een aantal criteria beschreven. Ook de Nederlandse richtlijncommissie heeft deze criteria gehanteerd.