Indicatie aanvullend onderzoek bij BPPD

Uitgangsvraag

Wat zijn de indicaties voor beeldvormend, audiologisch en vestibulair onderzoek bij verdenking op BPPD?

Aanbeveling

Beeldvormende technieken zijn niet geïndiceerd bij de diagnose BPPD. Beeldvormende technieken dienen wel te worden toegepast bij patiënten bij wie twijfel bestaat omtrent de diagnose BPP, bijvoorbeeld als additionele neurologische uitvalssymptomen aanwezig zijn, of bij therapieresistente BPPD.

Vestibulaire functietesten hebben geen toegevoegde waarde bij patiënten met BPPD.

Vestibulaire functietesten zijn alleen geïndiceerd bij patiënten met: 1) atypische nystagmus, 2) verdenking op additionele vestibulaire pathologie 3) een falende (of herhaaldelijk falende) reactie op canalith repositiemanoeuvres (CRM), of 4) frequent recidiverende BPPD.

Overwegingen

- Voordeel: snelle behandeling mogelijk maken door het voorkomen van overbodige testen en voorkomen van mogelijke vals-positieve diagnoses; voorkomen van stralingsbelasting (MRI) en bijwerkingen door testen.

- Nadeel: potentieel missen van comorbide aandoeningen, ongemak door misselijkheid en braken ten gevolge van vestibulaire testen.

- Kosten: kostenbesparing door het voorkomen van overbodige testen.

- Afweging van voordeel tegen nadeel: het voordeel weegt zwaarder.

- Waarde oordeel: het is belangrijk om overbodige testen en vertraging in het stellen van de diagnose te voorkomen.

Onderbouwing

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Niveau 3 |

Beeldvormend en vestibulair onderzoek heeft geen toegevoegde waarde bij het stellen van de diagnose BPPD. |

Samenvatting literatuur

The diagnosis of BPPV is based on the clinical history and physical examination. Routine radiographic imaging or vestibular testing is unnecessary in patients who already meet clinical criteria for the diagnosis of BPPV (Table 2.1). Further radiographic or vestibular testing may have a role in the diagnosis if the clinical presentation is felt to be atypical, if Dix-Hallpike testing elicits equivocal or unusual nystagmus findings, or if additional symptoms aside from those attributable to BPPV are present, suggesting an accompanying modifying CNS or otological disorder.

Radiographic Imaging

Radiographic imaging, most commonly CNS imaging using magnetic resonance or CT techniques, is commonly obtained in the evaluation of a primary symptom complaint of vertigo. However, imaging is not useful in the routine diagnosis of BPPV because there are no radiological findings characteristic of or diagnostic for BPPV (Turski, et al., 1996) (Turski, et al., 1996). The lack of characteristic findings is likely due to fact that the pathology presumed to occur in BPPV within the semicircular canals occurs at a microscopic level that is beyond the resolution of current neuroimaging techniques (Parnes, et al., 1992). On a broader scale, previous retrospective reviews of elderly patients with dizziness failed to detect any significant differences in cranial MRI findings when comparing dizzy versus non-dizzy patients (Colledge, et al., 1996) (Day, et al., 1990).

Radiographic imaging of the CNS should be reserved for patients who present with a clinical history compatible with BPPV but who also demonstrate additional neurological symptoms atypical for BPPV. Radiographic imaging may also be considered for patients with suspected BPPV but inconclusive positional testing, or in patients with other neurological signs on physical examination that are not typically associated with BPPV. Such symptoms include abnormal cranial nerve findings, visual disturbances, and severe headache, among others. It should be noted that intracranial lesions causing vertigo are rare. (Hanley, et al., 2001) Potential lesions causing vertigo identifiable on CNS imaging include cerebrovascular disease, demyelinating disease, or an intracranial mass; they are most often located in the brain stem cerebellum, thalamus, or cortex (Hanley, et al., 2001). In small case series, positional vertigo and nystagmus have been associated with neurovascular compression of cranial nerve VIII, vestibular schwannoma, Arnold Chiari malformation, and a variety of cerebellar disorders (Brandt, et al., 1994) (Jacobsen, et al., 1995) (Kumar, et al., 2002).

In distinction to standard BPPV, such conditions are quite rare and typically present with additional neurological symptoms in conjunction with the vertigo. Routine neuroimaging has not been recommended to discern these conditions from the more common causes of vertigo (Gizzi, et al., 1996). The costs of routine imaging in cases of BPPV are not justified given that diagnostic neuroimaging does not improve the diagnostic accuracy in the vast majority of BPPV cases. Therefore, neuroimaging should not be routinely used to confirm the diagnosis of BPPV.

Vestibular Function Testing

When patients meet clinical criteria for the diagnosis of BPPV (Table 2.1), no additional diagnostic benefit is obtained from vestibular function testing. Vestibular function testing is indicated when the diagnosis of a vertiginous or dizziness syndrome is unclear or possibly when the patient remains symptomatic following treatment. It may also be beneficial when multiple concurrent peripheral vestibular disorders are suspected (Baloh, et al., 1987) (Kentala, et al., 1996)(Lopez-Escamez, et al., 2003).

Vestibular function testing involves a battery of specialized tests that primarily record nystagmus in response to labyrinthine stimulation and/or voluntary eye movements. Most vestibular function testing relies on the neurological relationship between the regulation of eye movement and the balance organs: the vestibular-ocular reflex. These tests are useful in the evaluation of vestibular disorders that may not be evident from the history and clinical examination, and may provide information for quantification, prognostication, and treatment planning (Gordon, et al., 1996). The components of the vestibular function test battery identify abnormalities in ocular motility as well as deficits in labyrinthine response to position change, caloric stimulation, rotational movement, and static positions (sitting and supine). Caloric testing is an established, widely accepted technique that is particularly useful in determining unilateral vestibular hypofunction. Rotational chair testing is considered the most sensitive and reliable technique for quantifying the magnitude of bilateral peripheral vestibular hypofunction (Fife, et al., 2008) and to assess central compensation after peripheral vestibular loss. Some or all of these test elements may be included in a vestibular test battery.

In cases of BPPV in which the nystagmus findings are suggestive but not clear, it may be beneficial to use video-oculographic recordings of nystagmus associated with posterior canal BPPV. Especially video-recorded eye movements can be analysed in detail using image-processing techniques. for further study or second opinion without the need to repeat the Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre. A second diagnostic procedure often will result in more difficult to asses eye movements because of the typical fatigue of a BPPV. In a small percentage of cases, patients with a history of positional vertigo but unclear nystagmus findings may undergo vestibular function testing. Among complex patients referred for subspecialty evaluation of BPPV, such atypical or unclear nystagmus findings may approach 13 percent in patients with diagnoses suspicious for BPPV (Bath, et al., 2000).

BPPV is relatively frequently associated with additional vestibular pathology. Symptoms associated with chronic vestibular function may persist following appropriate treatment for BPPV, even if the treatment is effective in resolving the specific complaint of positional vertigo. For example, in highly selected subsets of patients referred for subspecialty evaluation of BPPV, additional otopathology and/or vestibulopathy has been identified in 31 to 53 percent of BPPV patients (Baloh, et al., 1987) (Roberts, et al., 2005) (Korres, et al., 2004). This percentage, however, is higher than what might be expected in the nonspecialty population. Vestibular disorders that have been associated with BPPV include Ménière’s disease, viral vestibular neuritis, or labyrinthitis (Hughes, et al., 1997)(Karlberg, et al., 2000). Vestibular function testing may be obtained when these additional diagnoses are suspected on the basis of signs or symptoms in addition to those of BPPV.

In patients with vestibular pathology in addition to BPPV, PRMs appear to be equally effective in resolving the positional nystagmus associated with BPPV, but complete symptom resolution is significantly less likely in those patients with additional vestibular pathology. In one study, 86 percent of patients with BPPV but without associated vestibular pathology reported complete resolution of symptoms after PRMs versus only 37 percent reporting complete resolution when additional vestibular pathology was present (Pollak, et al., 2004).

Thus, patients with suspected associated vestibular pathology in addition to BPPV may be a subset who would benefit from the additional information obtained from vestibular function testing. Similarly, up to 25 percent of patients with separate recurrences of BPPV are more likely to have associated vestibular pathology (Del Rio, et al., 2004); therefore, patients with recurrent BPPV may be candidates for vestibular function testing. In summary, patients with a clinical diagnosis of BPPV according to guideline criteria should not routinely undergo vestibular function testing, because the information provided from such testing adds little to the diagnostic accuracy in these cases, vestibular testing adds significant cost to the diagnosis and management of BPPV, and the information obtained does not alter the subsequent management of BPPV in the vast majority of the cases. Therefore, vestibular function testing should not be routinely obtained when the diagnosis of BPPV has already been confirmed by clinical diagnostic criteria. Vestibular function testing, however,may be warranted in patients with 1) atypical nystagmus, 2) suspected additional vestibular pathology, 3) a failed (or repeatedly failed) response to CRP, or 4) frequent recurrences of BPPV (Rupa, et al., 2004) (Gordon, et al., 2005).

Referenties

- American Medical Association’s Relative Value Scale Upgrade Committee (RUC) (2008). 2008 database, version 1. Based on 2005-06 Medicare Part B data; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Chicago: American Medical Association, 0, X-.

- Baloh, R.W., Honrubia, V., Jacobson, K. (1987). Benign positional vertigo: clinical and oculographic features in 240 cases. Neurology, 37, 371-8.

- Bath, A.P., Walsh, R.M., Ranalli, P., et al. (2000). Experience from a multidisciplinary “dizzy” clinic. Am J Otol, 21, 92-7.

- Brandt, T., Dieterich, M. (1994). VIIIth nerve vascular compression syndrome: vestibular paroxysmia. Baillieres Clin Neurol, 3, 565-75.

- Colledge, N.R., Barr-Hamilton, R.M., Lewis, SJ., et al. (1996). Evaluation of investigations to diagnose the cause of dizziness in elderly people: a community based controlled study. BMJ, 313, 788-92.

- Day, J.J., Freer, C.E., Dixon, A.K., et al. (1990). Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and brain-stem in elderly patients with dizziness. Age Ageing, 19, 144-50.

- Fife, T.D., Tusa, R.J., Furman, J.M., et al. (2000). Assessment: vestibular testing techniques in adults and children: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology, 55, 1431-41.

- Jacobson, G., Butcher, J.A., Newman, C.W., et al. (1995). When paroxysmal positional vertigo isn’t benign. J Am Acad Audiol, 6, 346-9.

- Gizzi, M., Riley, E., Molinari, S. (1996). The diagnostic value of imaging the patient with dizziness. A Bayesian approach. Arch Neurol, 53, 1299-304.

- Gordon, C.R., Shupak, A., Spitzer, O., et al. (1996). Nonspecific vertigo with normal otoneurological examination. The role of vestibular laboratory tests. J Laryngol Otol, 110, 1133-7.

- Gordon, C.R., Gadoth, N. (2005). Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: who can diagnose it, how should it be treated and where. Harefuah, 144, 567-71.

- Hanley, K., O’Dowd, T., Considine, N. (2001). A systematic review of vertigo in primary care. Br J Gen Pract, 51, 666-71.

- Havlik, R.J. (1986). Aging in the eighties, impaired senses for sound and light in persons aged 65 years and over, preliminary data from the supplement on aging to the national health interview survey, United States, January-June 1984. Advanced Data. . Vital Health Stat, 125, 2-.

- Hughes, C.A., Proctor, L. (1997). Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Laryngoscope, 107, 607-13.

- Karlberg, M., Hall, K., Quickert, N., et al. (2000). What inner ear diseases cause benign paroxysmal positional vertigo?. Acta Otolaryngol,, 120, 380-5.

- Kentala, E., Rauch, SD. (2003). A practical assessment algorithm for diagnosis of dizziness. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 128, 54-9.

- Kentala, E., Viikki, K., Pyykko, I., et al. (2000). Production of diagnostic rules from a neurotologic database with decision trees. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, 109, 170-6.

- Kentala, E., Pyykko, I. (2000). Vertigo in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Acta Otolaryngol, 543, 20-2.

- Kentala, E., Laurikkala, J., Pyykko, I., et al. (1999). Discovering diagnostic rules from a neurotologic database with genetic algorithms. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, 108, 948-54.

- Kentala, E. (1996). Characteristics of six otologic diseases involving vertigo. Am J Otol, 17, 883-92.

- Korres, S.G., Balatsouras, D.G. (2004). Diagnostic, pathophysiologic, and therapeutic aspects of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 131, 438-44.

- Kumar, A., Patni, A.H., Charbel, F. (2002). The Chiari I malformation and the neurotologist. Otol Neurotol, 23, 727-35.

- Parnes, L.S., Agrawal, S.K., Atlas, J. (2003). Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ, 169, 681-93.

- Pollak, L., Davies, R.A., Luxon, L.L. (2002). Effectiveness of the particle repositioning maneuver in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo with and without additional vestibular pathology. Otol Neurotol, 23, 79-83.

- Del Rio, M., Arriaga, M.A. (2004). Benign positional vertigo: prognostic factors. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 130, 426-9.

- Roberts, R.A., Gans, R.E., Kastner, A.H., et al. (2005). Prevalence of vestibulopathy in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo patients with and without prior otologic history. Int J Audiol, 44, 191-6.

- Rupa, V. (2004). Persistent vertigo following particle repositioning maneuvers: an analysis of causes. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 130, 436-9.

- Stewart, M.G., Chen, A.Y., Wyatt, J.R., et al. (1999). Cost-effectiveness of the diagnostic evaluation of vertigo. Laryngoscope, 109, 600-5.

- Turski, P., Seidenwurm, D., Davis, P., et al. (1996). American College of Radiology: ACR appropriateness criteria: vertigo and hearing loss. Reston (VA): American College of Radiology, 0, 8-.

- Turski, P., Seidenwurm, D., Davis, P., et al. (2006). American College of Radiology: Expert Panel on Neuroimaging: vertigo and hearing loss. Reston (VA): American College of Radiology, 0, 8-.

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 16-08-2013

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-02-2020

De tekst van deze module is opgesteld tijdens de richtlijnontwikkeling in 2010 door de oorspronkelijke richtlijnwerkgroep (zie Samenstelling werkgroep). De module is opnieuw beoordeeld en nog actueel bevonden door de werkgroep samengesteld voor de richtlijnherziening in 2019 (zie samenstelling huidige werkgroep). Uiterlijk in 2024 bepaalt het bestuur van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Keel-Neus-Oorheelkunde en Heelkunde van het Hoofd-Halsgebied of de richtlijnmodule nog actueel is.

Algemene gegevens

Met ondersteuning van de Orde van Medisch Specialisten. De richtlijnontwikkeling werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De richtlijn betreft een adaptatie van:

Clinical practice guideline: Benigne Paroxysmale Positionele Duizeligheid.

De Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery foundation ‘Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’ (Bhattacharayya, et al., 2008) vormde het uitgangspunt van de onderhavige richtlijn. Daarnaast werd de Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of neurology, gericht op de behandeling van BPPD, gebruikt ter aanvulling (Fife, et al., 2008), alsmede de discussies en richtlijnen van de Standaardisatie commissie van de Barany Society (Reykjavik, et al., 2010, www.baranysociety.nl).

Doel en doelgroep

De primaire doelstellingen van deze richtlijn zijn:

- De kwaliteit van de zorg te verbeteren door middel van een accurate en snelle diagnose van BPPD.

- Voorkomen van onnodig gebruik van medicijnen.

- Doelgericht gebruik van aanvullend onderzoek.

- Stimuleren van het gebruik van repositiemanoeuvres als therapie voor BPPD.

Secundaire doelstellingen zijn: beperking van de kosten van diagnose en behandeling van BPPD, vermindering van het aantal artsenbezoeken, en verbetering van de kwaliteit van leven. Het grote aantal patiënten met BPPD en de verscheidenheid aan diagnostische en therapeutische interventies voor BPPD maakt dit een geschikt onderwerp voor een evidence-based richtlijn.

De Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery foundation ‘Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’ (Bhattacharayya, et al., 2008) vormde het uitgangspunt van de onderhavige richtlijn. Daarnaast werd de Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of neurology, gericht op de behandeling van BPPD, gebruikt ter aanvulling (Fife, et al., 2008), alsmede de discussies en richtlijnen van de Standaardisatie commissie van de Barany Society (Reykjavik, et al., 2010, www.baranysociety.nl)). Onze doelstelling was om deze multidisciplinaire richtlijn te adapteren aan de Nederlandse situatie met behulp van Nederlandse input, waarbij de aanbevelingen rekening houden met wetenschappelijk bewijs en zich richten op harm-benefit balans, en expert consensus om de gaten in wetenschappelijk bewijs op te vullen. Deze specifieke aanbevelingen kunnen dan gebruikt worden om indicatoren te ontwikkelen en te gebruiken voor kwaliteitsverbetering.

Deze richtlijn is opgesteld voor KNO-artsen en neurologen die in hun klinische praktijk in aanraking komen met BPPD. De richtlijn is toepasbaar in iedere setting waar BPPD gediagnosticeerd en behandeld wordt.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de module is in 2018 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met BPPD.

De werkgroepleden zijn door hun beroepsverenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname. De werkgroep is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze module.

Samenstelling huidige werkgroep:

- Dr. Tj.D. (Tjasse) Bruintjes, KNO-arts, Gelre Ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn, NVKNO (voorzitter)

- Dr. R.B. (Roeland) van Leeuwen, neuroloog, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn, NVN

- Dr. R. (Raymond) van de Berg, KNO-arts/vestibuloloog, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht, NVKNO

- Dr. M. (Marloes) Thoomes-de Graaf, fysiotherapeut/manueel therapeut/klinisch epidemioloog, Fysio-Experts, Hazerswoude, KNGF en NVMT

- R.A.K. (Sandra) Rutgers, arts, MPH en voorzitter Commissie Ménière Stichting Hoormij, Houten, Stichting Hoormij

Met ondersteuning van:

- D. (Dieuwke) Leereveld, MSc., senior adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. M. (Monique) Wessels, informatiespecialist Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Samenstelling oorspronkelijke werkgroep (2010):

- dr. Tj.D. Bruintjes (voorzitter), KNO-arts, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn

- prof. dr. H. Kingma, klinisch fysicus/vestibuloloog, Maastricht Universitair Medisch Centrum en Technische Universiteit Eindhoven

- dr. D.J.M. Mateijsen, KNO-arts, Catharina ziekenhuis, Eindhoven

- dr. R.B. van Leeuwen, neuroloog, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn

- dr. ir. T van Barneveld klinisch epidemioloog, Orde van Medisch specialisten (adviseur)

- dr. M.L. Molag, Orde van Medisch specialisten (adviseur)

Belangenverklaringen

De werkgroepleden hebben onafhankelijk gehandeld en waren vrij van financiële of zakelijke belangen betreffende het onderwerp van de richtlijn.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

De Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery foundation ‘Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’ (Bhattacharayya, et al., 2008) vormde het uitgangspunt van de onderhavige richtlijn. Daarnaast werd de Amerikaanse richtlijn van de Academy of neurology gebruikt (Fife, et al., 2008). Dit betekent dat de Nederlandse richtlijncommissie de studies, de beoordeling & gradering ervan en de begeleidende tekst heeft overgenomen. Studies, relevant voor dit onderwerp, die nadien werden gepubliceerd konden in de richtlijncommissie worden ingebracht. De literatuur werd bovendien geupdate door te zoeken in Medline naar nieuw verschenen systematische reviews en RCTs met als onderwerp BPPD in de periode van 2008 t/m 2010.

De richtlijncommissie is voor elke aanbeveling in de Amerikaanse richtlijn nagegaan welke overwegingen naast het wetenschappelijk bewijs zijn gebruikt en of de door de commissie aangedragen studies de aanbeveling zouden kunnen veranderen. Wanneer er consensus was over deze overwegingen en door de commissie aangedragen studies geen ander inzicht opleverden, zijn de aanbevelingen overgenomen. Indien de commissie andere overwegingen (ook) van belang achtte of meende dat de door haar aangedragen studies een (iets) ander licht wierpen op de in de Amerikaanse richtlijn vermelde aanbeveling, zijn de aanbevelingen gemodificeerd.

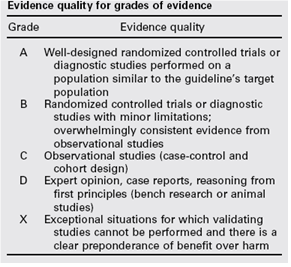

De gradering van de studies in de Amerikaanse richtlijn wijkt af van wat hier te lande gangbaar is. Vanuit het oogpunt van uniformiteit achtte de Nederlandse commissie het wenselijk de classificatie van bewijs c.q. gradering te converteren naar de Nederlandse classificatie. De Amerikaanse classificatie is hieronder afgebeeld in tabel. De corresponderende “Nederlandse” classificatie is in tabel 1.2 opgenomen.

Tabel 1.1: gradering van de studies in de Amerikaanse richtlijn

Tabel 1.2 Relatie tussen Evidence quality for grades of evidence en niveau van conclusie op basis van kwaliteit van bewijs conform Classificatieschema van CBO.

|

Evidence Quality - symbool |

Evidence Quality – omschrijving |

Niveau van conclusie – symbool |

Niveau van conclusie omschrijving |

|

A

|

Well-designed randomized controlled trials or diagnostic studies performed on a population similar to the guideline’s target population |

1 |

Meerdere gerandomiseerde dubbelblinde vergelijkende klinisch onderzoeken van goede kwaliteit van voldoende omvang, of

Meerdere onderzoeken ten opzichte van een referentietest (een ‘gouden standaard’) met tevoren gedefinieerde afkapwaarden en onafhankelijke beoordeling van de resultaten van test en gouden standaard, betreffende een voldoende grote serie van opeenvolgende patiënten die allen de index- en referentietest hebben gehad |

|

B |

Randomized controlled trials or diagnostic studies with minor limitations; overwhelmingly consistent evidence from observational studies |

2 |

Meerdere vergelijkende onderzoeken, maar niet met alle kenmerken als genoemd onder 1 (hieronder valt ook patiënt-controle onderzoek, cohort-onderzoek), of

Meerdere onderzoeken ten opzichte van een referentietest, maar niet met alle kenmerken die onder 1 zijn genoemd. |

|

C |

Observational studies (case-control and cohort design) |

||

|

D |

Expert opinion, case reports, reasoning from first principles (bench research or animal studies) |

3 en 4 |

Niet vergelijkend onderzoek of mening van deskundigen |

In de Amerikaanse richtlijn worden ook de aanbevelingen gegradeerd in termen van ‘strong recommendation’, ‘recommendation’, ‘option’. Hier te lande is graderen van aanbevelingen niet gebruikelijk. Om deze reden zijn in de Nederlandse richtlijn de aanbevelingen niet gegradeerd.

De literatuurzoekstrategie die de Amerikaanse richtlijncommissie heeft gevolgd, staat in bijlage 1 beschreven. Voor het opstellen van de aanbevelingen heeft de Amerikaanse richtlijncommissie gebruik gemaakt van de GuideLine Implementability Appraisal (GLIA) tool. Dit instrument dient om de helderheid van de aanbevelingen te verbeteren en potentiële belemmeringen voor de implementatie te voorspellen. In bijlage 3 wordt een aantal criteria beschreven. Ook de Nederlandse richtlijncommissie heeft deze criteria gehanteerd.