Zelfmanagement bij pijn bij kanker

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de rol van zelfmanagement bij pijn bij kanker?

Aanbeveling

Maak samen met de patiënt de afweging in hoeverre zelfmanagement aansluit bij de behoeften van de patiënt.

Nodig de patiënt uit zelf zoveel mogelijk de regie van de pijn op zich te nemen. Doe dat op basis van de wensen en mogelijkheden van de patiënt.

Bied geen structurele zelfmanagement programma’s standaard aan alle patiënten met pijn waarbij kanker de oorzaak is.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is een systematisch literatuuronderzoek verricht om een zelfmanagementprogramma gericht op pijn te vergelijken met zorg zonder zelfmanagement bij volwassenen met gemetastaseerde of curatieve kanker. De cruciale uitkomstmaat was pijn. Vanaf 0 tot 2 weken na de interventie en 4 tot 6 weken na de interventie vinden we mogelijk niet tot nauwelijks verlaging van de pijn. De bewijskracht is laag. Voor 8 tot 12 weken na de interventie is het resultaat te onzeker om hier conclusies aan te verbinden. De bewijskracht is zeer laag. De overall bewijskracht is daarmee ook zeer laag.

De belangrijke uitkomstmaten waren kwaliteit van leven en self-efficacy. Voor 0 tot 2 weken en 4 tot 6 weken na de interventie werden geen klinisch relevante verschillen gevonden voor zelfmanagement. De bewijskracht is laag. Voor 8 tot 12 weken na de interventie zijn de resultaten te onzeker om hier conclusies aan te verbinden over kwaliteit van leven, vanwege een zeer lage bewijskracht.

Voor self-efficacy werd op alle tijdspunten geen klinisch relevant verschil gevonden. Er is daarom mogelijk niet tot nauwelijks effect op self-efficacy. De bewijskracht is laag.

De bewijskracht werd over het algemeen afgewaardeerd omdat de studies niet volledig geblindeerd waren, en soms vanwege kleine studiepopulaties of brede betrouwbaarheidsintervallen. De resultaten kunnen daarom geen overtuigend bewijs leveren voor de besluitvorming.

Omdat er wel een trend naar effect zichtbaar is ondanks de genoemde methodologische beperkingen, pijn bij kanker steeds meer chronisch van aard is en bij 20% van de patiëntenpopulatie ook niet-oncologische chronische pijn voorkomt, kan er aanvullend gekeken worden naar grotere gecontroleerde studies die verricht zijn bij patiënten met chronische niet-oncologische pijn (Miller, 2020; Getracht, 2021).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Het is aannemelijk dat niet alle patiënten behoefte hebben aan zelfmanagement. Sommige patiënten hebben (veel) meer behoefte aan regie en controle dan andere. Dit zou een aanvullende verklaring kunnen zijn dat er geen grote verschillen gevonden zijn bij de besproken studies. Het is belangrijk om na te gaan of zelfmanagement aansluit bij de behoeften van de patiënt.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Bij de structurele invoering van een zelfmanagementprogramma kunnen de zorgkosten toenemen, omdat een dergelijk programma ontwikkeld dient te worden en er meer ondersteuning aan de patiënt gegeven moet worden bij het doorlopen ervan. Naar verwachting nemen de kosten na verloop van tijd af, omdat de patiënt zelf bij zelfmanagement geen kosten genereert. Over de kosteneffectiviteit is echter, zeker in het kader van pijn bij kanker, nog niets bekend.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Er is tot op heden geen onderzoek verricht naar de haalbaarheid van structurele implementatie in de praktijk. Zowel inhoudelijke vormgeving als praktische uitvoering van een zelfmanagementprogramma gericht op pijn dienen in Nederland nog volledig ontwikkeld te worden. Hierbij kunnen buitenlandse programma´s, zoals gebruikt in de diverse studies, als model voor inhoudelijke ontwikkeling dienen. Ook kunnen Nederlandse patiëntverenigingen gericht op chronische pijn hebben hierin ondersteunen. Simultaan dient er nagedacht te worden over praktische aspecten van implementatie in de Nederlandse praktijk. Betrokkenheid van en samenwerking tussen verschillende disciplines, training van personeel en positionering in de zorgketen zijn hierbij belangrijke thema´s. Ook moet er een adequate mogelijkheid tot regieondersteuning aangeboden worden aan de patiënt, wat in de huidige praktijk nog onvoldoende gedaan wordt (leidraad 'Organisatie en werkwijze zorg voor patiënten met chronische pijn’ – module Organisatie van de chronische pijnzorg).

Tijdsinvestering en kosten die met bovenstaande ontwikkeling gemoeid zijn, vormen voor nu de belangrijkste beperkende factoren voor structurele implementatie.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Structurele implementatie van een zelfmanagementprogramma in de behandeling van de patiënt met pijn bij kanker wordt momenteel nog niet geadviseerd, omdat de effectiviteit vanuit het wetenschappelijk bewijs te onzeker is om hier conclusies aan te verbinden.

De impact op de kosten en tijdsinvestering in de praktijk is op korte termijn zodanig groot dat structurele implementatie nu niet gewenst is.

Vanuit een persoonsgerichte en multidimensionale benadering van (chronische) pijn bij kanker wordt afweging en toepassing van zelfmanagement op individueel niveau aanbevolen, waarbij de behoefte van de patiënt leidend is.

De werkgroep adviseert na multidimensionale diagnostiek van de pijn, zelfmanagent met de patiënt te bespreken en gezamenlijk te besluiten over de invulling hiervan, waarbij de nadruk bij oncologische pijn ligt op de mogelijkheden en behoeften van de patiënt. Daarbij dient de behandelaar rekening te houden met de gezondheidsvaardigheden van de patiënt.

Onderwerpen die hierbij aan bod kunnen komen zijn (gebaseerd op Zorgstandaard Chronische Pijn, 2017):

- Pijneducatie, gericht op het verwerven van inzicht en kennis over ontstaan, gevolgen en in standhoudende factoren van pijn vanuit het biopsychosociaal model. Hierbij kunnen bestaande podcasts en online informatie ondersteuning bieden;

- Eigen regie: het actief deelnemen aan de behandeling en zelf medeverantwoordelijkheid nemen voor de behandeling;

- Het leren omgaan met pijn en de gevolgen van pijn;

- Niet-farmacologische behandelmogelijkheden van pijn gericht op alle soorten pijn die een patiënt kan hebben.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

De definitie van de Zorgmodule Zelfmanagement 1.0 (CBO, 2014), die patiënten met één of meerdere chronische ziekten betreft, luidt: ‘Zelfmanagement is het zodanig omgaan met de chronische aandoening (symptomen, behandeling, lichamelijke, psychische en sociale consequenties en bijbehorende aanpassingen in leefstijl) dat de aandoening optimaal wordt ingepast in het leven. Zelfmanagement betekent dat chronisch zieken zelf kunnen kiezen in hoeverre men de regie over het leven in eigen hand wil houden en mede richting wil geven aan hoe beschikbare zorg wordt ingezet, om een optimale kwaliteit van leven te bereiken of te behouden.’

Zelfmanagement is momenteel in Nederland nog geen vast onderdeel van de behandeling van patiënten met pijn bij kanker. De vorige richtlijnmodule liet destijds geen bewijs zien voor een rechtstreeks positief effect van zelfmanagement op pijn bij kanker.

In de hedendaagse praktijk lijkt een groot deel van de patiënten met chronische pijn zich prettig te voelen bij en behoefte te hebben aan het voeren van regie over de behandeling van hun eigen pijn. Dit geldt ook voor de populatie van patiënten met kanker, welke een toenemend chronisch karakter kent. Naast pijn veroorzaakt door kanker, maakt pijn veroorzaakt door ingezette behandeling hier steeds vaker deel van uit. Te denken valt daarbij aan persisterende postoperatieve pijn, pijn na of tijdens radio-, chemo- of endocriene of immunotherapie maar ook chronische pijn door andere oorzaken (incidentie 20% bij volwassenen) maakt hier deel van uit. Zelfmanagement is bij al deze soorten pijn een relevant thema.

In deze module wordt de effectiviteit en precieze invulling van zelfmanagement beter onderbouwd vanuit de literatuur en vertaald naar een aanbeveling voor de praktijk.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Pain intensity

|

Low GRADE |

Self-management program focused on pain may result in little to no difference in pain intensity at 0 to 2 weeks post-treatment when compared to no self-management program in adults with metastasized or curative cancer experiencing cancer-related pain.

Sources: Jahn, 2014; Kelleher, 2021; Koller, 2018; Kravitz, 2012; Kwekkeboom, 2012; Raphaelis, 2021; Rustøen, 2014. |

|

Self-management program focused on pain may result in little to no difference in pain intensity at 4 to 6 weeks post-treatment when compared to no self-management program in adults with metastasized or curative cancer experiencing cancer-related pain.

Sources: Bennett, 2021; Eaton, 2021; Jahn, 2014; Knoerl, 2018 Koller, 2013; Koller, 2018; Kravitz, 2012; Musavi, 2021; Raphaelis, 2021; Rustøen, 2014; Valenta, 2022. |

|

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of a self-management program focused on pain on pain intensity at 8 to 12 weeks post-treatment when compared to no self-management program in adults with metastasized or curative cancer experiencing cancer-related pain.

Sources: Bennett, 2021; Eaton, 2021; Kelleher, 2021; Knoerl, 2018; Koller, 2013; Kravitz, 2012; Musavi, 2021; Raphaelis, 2021. |

Quality of life

|

Low GRADE

|

Self-management program focused on pain may result in little to no difference in quality of life at 0 to 2 weeks post-treatment when compared to no self-management program in adults with metastasized or curative cancer experiencing cancer-related pain.

Sources: Jahn, 2014; Kelleher, 2021; Koller, 2018; Raphaelis, 2021. |

|

Self-management program focused on pain may result in little to no difference in quality of life at 4 to 6 weeks post-treatment when compared to no self-management program in adults with metastasized or curative cancer experiencing cancer-related pain.

Sources: Bennett, 2021; Knoerl, 2018; Koller, 2018; Kravitz, 2012; Musavi, 2021; Raphaelis, 2021. |

|

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of a self-management program focused on pain on quality of life at 8 to 12 weeks post-treatment when compared to no self-management program in adults with metastasized or curative cancer experiencing cancer-related pain.

Sources: Bennett, 2021; Knoerl, 2018; Musavi, 2021; Raphaelis, 2021. |

Self-efficacy

|

Low GRADE |

Self-management program focused on pain may result in little to no difference in self-efficacy at 0 to 2 weeks post-treatment when compared to no self-management program in adults with metastasized or curative cancer experiencing cancer-related pain.

Sources: Kelleher, 2021; Koller, 2018; Kravitz, 2012; Raphaelis, 2021. |

|

Self-management program focused on pain may result in little to no difference in self-efficacy at 4 to 6 weeks post-treatment when compared to no self-management program in adults with metastasized or curative cancer experiencing cancer-related pain.

Sources: Koller, 2013; Koller, 2018; Kravitz, 2012; Raphaelis, 2021. |

|

|

Self-management program focused on pain may result in little to no difference in self-efficacy at 8 to 12 weeks post-treatment when compared to no self-management program in adults with metastasized or curative cancer experiencing cancer-related pain.

Sources: Kelleher, 2021; Koller, 2018; Kravitz, 2012; Raphaelis, 2021. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

The fourteen RCTs included various self-management interventions targeting cancer-related pain. An overview of the included studies is depicted in Table 1. The interventions are categorized in two categories:

- Skills/coping training, and/or education

- Patient-controlled at-home relaxation/distraction

The results are described per category for all outcome measures.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

BPI: brief pain inventory; CB: cognitive behavioral; CIPN: chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy; CPSE: Chronic Pain Self-Efficacy scale; EORTC QLQ-C30: European Organization for Research and Treatment for Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire; FACT-G: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General NRS: numeric rating scale; VAS: visual analog scale.

Results

1. Pain intensity

1.1 Assessed 0 to 2 weeks post-treatment

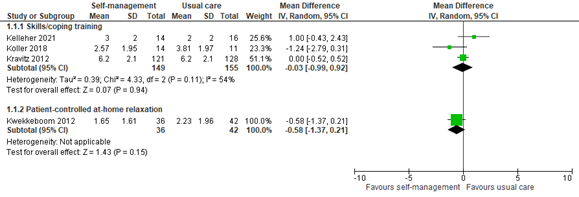

Three studies reported pain scores within 2 weeks of an intervention including skills or coping training. The pooled mean difference (MD) of -0.03 (95% confidence interval -0.99 to 0.92) showed no clinically relevant difference between the groups (Figure 1). One study reported pain scores within 2 weeks of patient-controlled at-home relaxation. The difference between groups was also not clinically relevant (MD -0.58, 95% CI -1.37 to 0.21; Figure 1).

Figure 1: Pain scores at 0 to 2 weeks post-treatment; self-management vs. usual care.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval.

In addition, three studies provided limited data that was not quantified and could therefore not be included in figure 1. All three studies fall into the category of skills or coping training.

Jahn (2014) only reported that no group differences were found in pain intensity at the 7th day post-discharge.

Raphaelis (2021) showed average pain scores graphically. At 2 weeks post-treatment, mean average pain scores were slightly lower in the intervention group than the control group, although not clinically relevant.

Rustøen (2014) showed NRS pain scores graphically. At week 1 and 2 after the psychoeducational intervention, no clinically relevant difference is observed between intervention and control group.

These results are in line with the pooled analysis.

1.2 Assessed 4 to 6 weeks post-treatment

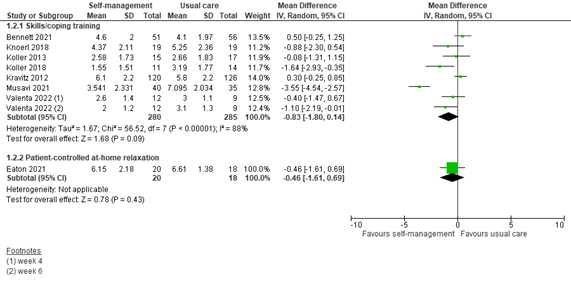

Seven studies reported pain scores at 4 to 6 weeks after an intervention including skills or coping training. The pooled MD was -0.83 (95% CI -1.80 to 0.14) in favor of a self-management intervention (Figure 2). This difference is not clinically relevant.

One study reported pain scores at 4 to 6 weeks after a patient-controlled at-home relaxation intervention. The MD was -0.46 (95% CI -1.61 to 0.69) in favor of the intervention (Figure 2). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Figure 2: Pain scores at 4 to 6 weeks post-treatment; self-management vs. usual care.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval.

In addition to the pooled analysis, four studies reported pain scores that could not be pooled. All four studies fall into the category of skills or coping training.

Jahn (2014) showed NRS pain scores graphically. On the 28th day post-discharge, a potentially clinically relevant difference in average pain scores is observed in favor of the intervention group. The mean difference between groups is approximately 1.

Raphaelis (2021) showed average pain scores graphically. At 4 weeks post-treatment, mean average pain scores were lower in the intervention group than the control group. The difference between groups was approximately 1 and therefore might be just clinically relevant.

Rustøen (2014) showed NRS pain scores graphically. Week 4 to 6 show similar average pain scores for both groups. There is no clinically relevant difference.

Syrjala (2008) showed BPI pain scores graphically. At 1 month, a potentially clinically relevant difference in usual pain rating is observed in favor of the intervention group. The mean difference between groups is approximately 1.

1.3 Assessed 8 to 12 weeks post-treatment

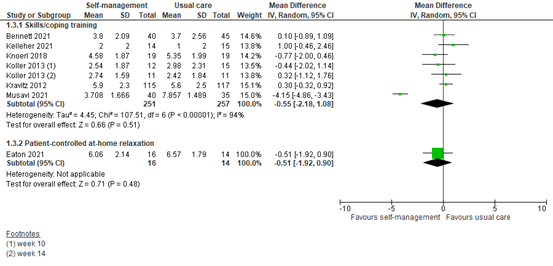

Six studies reported pain scores at 8 to 12 weeks after an intervention including skills or coping training. The pooled MD was -0.55 (95% CI -2.18 to 1.08) in favor of a self-management intervention (Figure 3). This difference is not clinically relevant.

One study showed pain scores at 8 to 12 weeks after a patient-controlled at-home relaxation intervention. The MD was -0.51 (95% CI -1.92 to 0.90) in favor of the intervention (Figure 3). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Figure 3: Pain scores at 8 to 12 weeks post-treatment; self-management vs. usual care.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval.

In addition, two studies could not be pooled since data was not quantified.

Raphaelis (2021) showed average pain scores graphically. At 8 weeks after skills training, mean average pain scores were lower in the intervention group than the control group, although not clinically relevant.

Syrjala (2008) showed BPI pain scores graphically. At 3 months after education and training, mean usual pain ratings were lower in the intervention group than the control group, but not clinically relevant.

2. Quality of life

2.1 Assessed 0 to 2 weeks post-treatment

Four studies reported quality of life (QoL) assessed within two weeks of self-management intervention. All interventions included coping or skills training or patient education. Data could not be pooled, as only two studies reported means and standard deviations.

Jahn (2014) reported health relatedQoLassessed by EORTC QLQ C30 (scale 0-100) 7 days after discharge. Only an adjusted MD was reported of 1.20 (95% CI -7.54 to 9.95). This difference was not clinically relevant in favor of the intervention group.

Kelleher (2021) reported health-related QoL assessed post-treatment by the 27-item Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G; scale 0-108). The scores were 80 (SD 16) in the intervention group and 80 (SD 13) in the control group (SMD 0; 95% CI -0.71 to 0.71). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Koller (2018) reported QoL assessed by the Medical Outcome Study Short-Form (scale 0-100) at 1 week. Physical and mental quality of life were presented separately. Physical quality of life was 28.14 (SD 6.01) in the intervention group and 25.72 (SD 3.91) in the control group (SMD 0.45; 95% CI -0.36 to 1.27). Mental quality of life was 50.25 (SD 18.04) in the intervention group and 44.44 (SD 14.7) in the control group (SMD 0.34; 95% CI -0.47 to 1.15). Both physical and mental QoL were not clinically relevant in favor of the intervention group.

Raphaelis (2021) showed EORTC-C30 QoL scores graphically. At 1-week post-intervention, the QoL scores were similar for the intervention and control group.

2.2 Assessed 4 to 6 weeks post-treatment

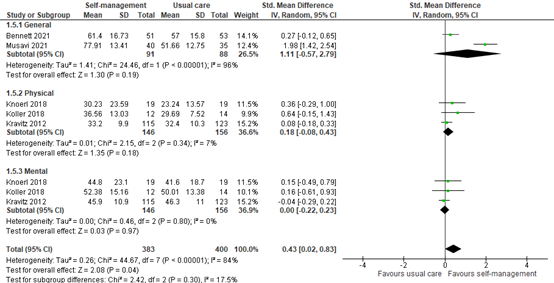

Five studies reported QoL assessed within 4 to 6 weeks of self-management intervention. All interventions included coping or skills training or patient education. Two studies reported general QoL, and three studies reported mental and physical QoL separately (Figure 4).

General QoL scored a SMD of 1.11 (95% CI -0.57 to 2.79) in favor of the intervention group. Physical QoL scored a SMD of 0.18 (95% CI -0.08 to 0.43) in favor of the intervention group. Mental QoL scored a SMD of 0.00 (95% CI -0.22 to 0.23), and therefore no difference between the groups was observed.

Total pooled QoL (general, physical and mental) was 0.43 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.83) in favor of the intervention group, although the difference was not clinically different between groups.

Figure 4: Quality of life scores at 4 to 6 weeks post-treatment; self-management vs. usual care.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval.

In addition, Raphaelis (2021) showed EORTC-C30 QoL scores graphically. At 4 weeks post-intervention, the QoL scores were the same for the intervention and control group. This is somewhat in line with the pooled analysis.

2.3 Assessed 8 to 12 weeks post-treatment

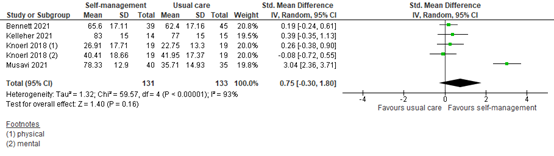

Four studies reported QoL assessed within 8 to 12 weeks of self-management intervention. All interventions included coping or skills training or patient education. Three studies reported general QoL, and one study reported mental and physical QoL separately (Figure 5). The pooled SMD was 0.75 (95% CI -0.30 to 1.80). This difference is clinically relevant in favor of the intervention group.

Figure 5: Quality of life scores at 8 to 12 weeks post-treatment; self-management vs. usual care.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval.

In addition, Raphaelis (2021) showed EORTC-C30 QoL scores graphically. At 8 weeks post-intervention, the QoL scores were similar for the intervention and control group. This is somewhat in line with the pooled analysis.

3. Self-efficacy

3.1 Assessed 0 to 2 weeks post-treatment

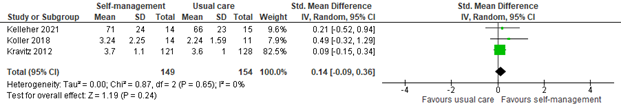

Three studies reported self-efficacy within two weeks of self-management intervention. All interventions included coping or skills training or patient education. The pooled SMD was 0.14 (95% CI -0.09 to 0.36; Figure 6). This difference is not clinically relevant in favor of the intervention group.

Figure 6: Self-efficacy scores at 0 to 2 weeks post-treatment; self-management vs. usual care.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval.

In addition, Raphaelis (2021) reported pain-related self-efficacy assessed by the German Pain Self-efficacy Questionnaire (FESS). Results were reported as Cohen’s d. Cohen’s d was 0.17, indicating a small effect of self-management on pain-related self-efficacy. This is in line with the pooled results.

3.2 Assessed 4 to 6 weeks post-treatment

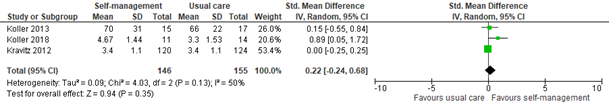

Three studies reported self-efficacy within 4 to 6 weeks of self-management intervention. All interventions included coping or skills training or patient education. The pooled SMD was 0.22 (95% CI -0.24 to 0.68; Figure 7). This difference is not clinically relevant in favor of the intervention group.

Figure 7: Self-efficacy scores at 4 to 6 weeks post-treatment; self-management vs. usual care.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval.

In addition, Raphaelis (2021) reported pain-related self-efficacy assessed by the German Pain Self-efficacy Questionnaire (FESS). Results were reported as Cohen’s d. At 4 weeks post-treatment, Cohen’s d was 0.53, indicating a medium-sized effect of self-management on pain-related self-efficacy. This is in line with the pooled results.

3.3 Assessed 8 to 12 weeks post-treatment

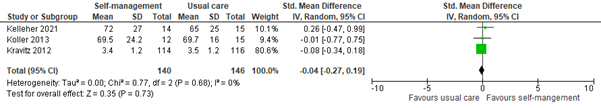

Three studies reported self-efficacy within 8 to 12 weeks of self-management intervention. All interventions included coping or skills training or patient education. The pooled SMD was -0.04 (95% CI -0.27 to 0.19; Figure 8). This difference is not clinically relevant in favor of the control group.

Figure 8: Self-efficacy scores at 8 to 12 weeks post-treatment; self-management vs. usual care.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval.

In addition, Raphaelis (2021) reported pain-related self-efficacy assessed by the German Pain Self-efficacy Questionnaire (FESS). Results were presented graphically. At 8 weeks post-treatment, self-efficacy scores were slightly higher in the intervention group, although not clinically relevant. This is not in line with the pooled results.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain intensity at 0 to 2 weeks was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1); pooled confidence intervals crossing one threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain intensity at 4 to 6 weeks was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1); pooled confidence intervals crossing one threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain intensity at 8 to 12 weeks was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1); pooled confidence intervals crossing the thresholds for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life at 0 to 2 weeks was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1); number of included patients (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life at 4 to 6 weeks was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1); and the pooled confidence intervals crossing the threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life at 8 to 12 weeks was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1); the pooled confidence intervals crossing two thresholds for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure self-efficacy at 0 to 2 weeks was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1); and the number of included patients (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure self-efficacy at 4 to 6 weeks was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1); and the pooled confidence interval crossing the threshold for clinical relevance and the number of included patients (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure self-efficacy at 8 to 12 weeks was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1); and the number of included patients (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the (un)favorable effects of self-management in patients with cancer and pain?

| P: | Adults with metastasized cancer or curative cancer experiencing cancer-related pain (terminal phase excluded) |

| I: | Self-management program focused on pain |

| C: | No (structured) self-management program focused on pain |

| O: | Pain intensity, quality of life, self-efficacy |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered pain intensity as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and quality of life and self-efficacy as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined the following as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference:

Pain intensity: MD <-1 or > 1

Quality of life: SMD < -0.5 or > 0.5

Self-efficacy: SMD < -0.5 or > 0.5

If applicable, means and standard deviations were estimated from the medians and interquartile ranges using the method by Hozo (2005).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until April 24, 2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 553 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- (Systematic reviews of) randomized controlled trials

- Published ≥ 2008

- N ≥ 10 per arm

- Conform PICO

A total of 69 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 55 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and fourteen studies were included.

Results

Fourteen studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Bennett MI, Allsop MJ, Allen P, Allmark C, Bewick BM, Black K, Blenkinsopp A, Brown J, Closs SJ, Edwards Z, Flemming K, Fletcher M, Foy R, Godfrey M, Hackett J, Hall G, Hartley S, Howdon D, Hughes N, Hulme C, Jones R, Meads D, Mulvey MR, O'Dwyer J, Pavitt SH, Rainey P, Robinson D, Taylor S, Wray A, Wright-Hughes A, Ziegler L. Pain self-management interventions for community-based patients with advanced cancer: a research programme including the IMPACCT RCT. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2021 Dec. PMID: 34870925.

- Eaton LH, Beck SL, Jensen MP. An Audio-Recorded Hypnosis Intervention for Chronic Pain Management in Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2021 Oct-Dec;69(4):422-440. doi: 10.1080/00207144.2021.1951119. Epub 2021 Jul 26. PMID: 34309480; PMCID: PMC8458244.

- Geraghty AWA, Maund E, Newell D, Santer M, Everitt H, Price C, Pincus T, Moore M, Little P, West R, Stuart B. Self-management for chronic widespread pain including fibromyalgia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021 Jul 16;16(7):e0254642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254642. PMID: 34270606; PMCID: PMC8284796.

- Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005 Apr 20;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. PMID: 15840177; PMCID: PMC1097734.

- Jahn P, Kuss O, Schmidt H, Bauer A, Kitzmantel M, Jordan K, Krasemann S, Landenberger M. Improvement of pain-related self-management for cancer patients through a modular transitional nursing intervention: a cluster-randomized multicenter trial. Pain. 2014 Apr;155(4):746-754. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.01.006. Epub 2014 Jan 13. PMID: 24434732.

- Musavi M, Jahani S, Asadizaker M, Maraghi E, Razmjoo S. The Effect of Pain Self-Management Education on Pain Severity and Quality of Life in Metastatic Cancer Patients. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2021 May 31;8(4):419-426. doi: 10.4103/apjon.apjon-2097. PMID: 34159235; PMCID: PMC8186386.

- Kelleher SA, Fisher HM, Winger JG, Somers TJ, Uronis HE, Wright AN, Keefe FJ. Feasibility, engagement, and acceptability of a behavioral pain management intervention for colorectal cancer survivors with pain and psychological distress: data from a pilot randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. 2021 Sep;29(9):5361-5369. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06126-8. Epub 2021 Mar 8. PMID: 33686520.

- Knoerl R, Smith EML, Barton DL, Williams DA, Holden JE, Krauss JC, LaVasseur B. Self-Guided Online Cognitive Behavioral Strategies for Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy: A Multicenter, Pilot, Randomized, Wait-List Controlled Trial. J Pain. 2018 Apr;19(4):382-394. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2017.11.009. Epub 2017 Dec 8. PMID: 29229430.

- Koller A, Gaertner J, De Geest S, Hasemann M, Becker G. Testing the Implementation of a Pain Self-management Support Intervention for Oncology Patients in Clinical Practice: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study (ANtiPain). Cancer Nurs. 2018 Sep/Oct;41(5):367-378. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000502. PMID: 28537957.

- Koller A, Miaskowski C, De Geest S, Opitz O, Spichiger E. Results of a randomized controlled pilot study of a self-management intervention for cancer pain. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013 Jun;17(3):284-91. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2012.08.002. Epub 2012 Sep 4. PMID: 22959603.

- Kravitz RL, Tancredi DJ, Grennan T, Kalauokalani D, Street RL Jr, Slee CK, Wun T, Oliver JW, Lorig K, Franks P. Cancer Health Empowerment for Living without Pain (Ca-HELP): effects of a tailored education and coaching intervention on pain and impairment. Pain. 2011 Jul;152(7):1572-1582. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.02.047. Epub 2011 Mar 24. PMID: 21439726.

- Kwekkeboom KL, Abbott-Anderson K, Cherwin C, Roiland R, Serlin RC, Ward SE. Pilot randomized controlled trial of a patient-controlled cognitive-behavioral intervention for the pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbance symptom cluster in cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012 Dec;44(6):810-22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.12.281. Epub 2012 Jul 7. PMID: 22771125; PMCID: PMC3484234.

- Miller J, MacDermid JC, Walton DM, Richardson J. Chronic Pain Self-Management Support With Pain Science Education and Exercise (COMMENCE) for People With Chronic Pain and Multiple Comorbidities: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020 May;101(5):750-761. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2019.12.016. Epub 2020 Jan 29. PMID: 32004517.

- Raphaelis S, Frommlet F, Mayer H, Koller A. Implementation of a nurse-led self-management support intervention for patients with cancer-related pain: a cluster randomized phase-IV study with a stepped wedge design (EvANtiPain). BMC Cancer. 2020 Jun 16;20(1):559. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-06729-0. PMID: 32546177; PMCID: PMC7296932.

- Rustøen T, Valeberg BT, Kolstad E, Wist E, Paul S, Miaskowski C. A randomized clinical trial of the efficacy of a self-care intervention to improve cancer pain management. Cancer Nurs. 2014 Jan-Feb;37(1):34-43. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182948418. PMID: 23666269.

- Syrjala KL, Walsh CA, Yi JC, Leisenring WM, Rajotte EJ, Voutsinas J, Ganz PA, Jacobs LA, Palmer SC, Partridge A, Baker KS. Cancer survivorship care for young adults: a risk-stratified, multicenter randomized controlled trial to improve symptoms. J Cancer Surviv. 2022 Oct;16(5):1149-1164. doi: 10.1007/s11764-021-01105-8. Epub 2021 Sep 29. PMID: 34590205; PMCID: PMC9438455.

- Valenta S, Miaskowski C, Spirig R, Zaugg K, Denhaerynck K, Rettke H, Spichiger E. Randomized clinical trial to evaluate a cancer pain self-management intervention for outpatients. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2022 Jan 21;9(1):39-47. doi: 10.1016/j.apjon.2021.12.003. PMID: 35528799; PMCID: PMC9072187.

- Zorgstandaard Chronische Pijn, Leiden, Vereniging Samenwerkingsverband Pijnpatiënten naar één stem, 28 maart 2017.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table of the included randomized controlled trials

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Bennett, 2021 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: oncology outpatient clinics, multi-center study

Country: UK

Source of funding: government |

Inclusion criteria: 1. Aged 16 years or over 2. Diagnosis of advanced incurable disease (locally advanced or metastatic) in one of the following disease areas: breast, colon or rectal, non-small cell lung cancer, prostate, upper GI 3. Experiencing cancer related pain (tumour or treatment related) (as assessed by the Clinician) with an average pain score of = 4 on the “average pain” item of the Brief Pain Inventory 4. Has the potential to benefit from palliative care support as assessed by the Clinician 5. An expected prognosis of 12 weeks or more 6. The patient is living at home 7. The patient lives in the local catchment area for a participating hospice 8. The patient is able and willing to provide written informed consent

Exclusion criteria: 1. Previously referred to palliative care team 2. The patient has insufficient literacy, or proficiency in English to contribute to the data collection required for the research 3. Patients will be excluded if they lack capacity to provide informed consent to this trial 4. Patients with dominant chronic pain that is not cancer related (tumour or treatment)

N total at baseline: Intervention: 80 Control: 81

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I:62.5 ± 11.73 C: 65.7 ± 11.29

Sex: I: 52.2% M C: 60% M

Groups comparable at baseline? yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Usual care plus Supported Self-Management (SSM) intervention delivered within the oncology clinic and palliative care services by locally assigned community palliative care nurses (health professional), consisting of self-management/educational support and pain monitoring |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Usual care: An initial palliative care visit took place |

Length of follow-up: 12 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 6 weeks (n=29, 36.3%)/12 weeks (n=39, 48.8%) Reason • Died, n=7/17 • Too unwell, n=3/2 • Withdrawal, n=2/3 • Unable to contact, n=10/8 • Contacted not returned, n=5/8 • Administrative error, n=2/1

Control: 6 weeks (n=25, 30.9%)/12 weeks (n=35, 43.2%) Reason • Died, n=6/12 • Too unwell, n=5/9 • Withdrawal, n=2/3 • Unable to contact, n=9/7 • Contacted not returned, n=3/3 • Administrative error, n=0/1 Incomplete outcome data: The primary outcome (pain severity) was available for all time points for 78 (48.4%) participants, for at least one follow-up time point for 37 (23.0%) participants and for baseline only for 45 (28.0%) participants, and was not available at any time point for one (0.6%) participant

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

BPI Pain severity score Average pain Baseline I: 5.6 (1.36); N=79 C: 5.4 (1.47); N=81

6 weeks I: 4.6 (2.00); N=51 C: 4.1 (1.97); N=56

12 weeks I: 3.8 (2.09); N=40 C: 3.7 (2.56); N=45

EORTC QLQ-C30 Summary Score (scores 0-100; higher score = high QoL and functioning)

Baseline I: 57.4 (17.20); N=77

6 weeks I: 61.4 (16.73); N=51 C: 57.0 (15.80); N=53

12 weeks I: 65.6 (17.11); N=39 C: 62.4 (17.16); N=45 |

Author’s conclusion: The authors’ programme of research has revealed new insights into how patients with advanced cancer manage their pain and the challenges faced by health professionals in identifying those who need more help. Our clinical trial failed to show an added benefit of our interventions to enhance existing community palliative care support, although both the decision model and the economic evaluation of the trial indicated that supported self-management could result in lower health-care costs.

|

|

Jahn, 2014 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: inpatients, multi-center study

Country: Germany

Source of funding: non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria: 1) patients on hospital wards that frequently admitted oncological patients (≥10% admitted per year) 2) consent for participation 3) 18-80 years 4) NRS ≥3 for average pain intensity 5) persisting pain for >3 days

Exclusion criteria: 1) limited performance status (ECOG<4) 2) documented ongoing drug or alcohol abuse 3) surgery within the last 3 days 4) showing signs of disorientation 5) unable to read, write and understand German

N total at baseline: Intervention: 128 Control: 135

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I:58 ± 12 C: 56 ± 13

Sex: I: 59% M C: 60% M

Groups comparable at baseline? No, differences in ECOG status, malignancy types, metastases, amount of pain medication, sufficiency of pain management, adherence to pain medication, anxiety and depression |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

SCION-PAIN Counseling on pain management (pharmacological, non-pharmacological and pain-related discharge management) on day

Plus

30 mins by study nurse) and day 2 (30 minutes by trained nurse)

Plus

Follow-up counseling on every 3rd day (20 mins by trained nurse)

Plus

Day before discharge: pain related discharge management (10 mins by study nurse)

Plus

2-3 days after discharge: pain related discharge management (20 mins by study nurse)

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Standard pharmacological pain treatment |

Length of follow-up: 4 weeks after discharge from hospital Primary outcome: pain intensity after 1 week

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 26 (20%) Reasons: 16 withdrew, 10 died

Control: 30 (22%) Reasons: 19 withdrew, 11 died

Incomplete outcome data: As above

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Pain intensity: (BPI 0-10) Average and worst pain difference between groups (DNR; NS).

Average and worst pain significantly lower in SCION-PAIN group after 4 weeks of follow-up (secondary outcome).

HRQoL measured by EORTC QLQ C30 Adjusted mean difference 1.20 (-7.54 to 9.95)

|

Author’s conclusion: This trial reveals the positive impact of a nursing intervention to improve patients’ self-management of cancer pain. |

|

Koller, 2013 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: outpatients

Country: Germany

Source of funding: non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria: 1) cancer pain ≥3 on a 0-10 NRS 2) ≥18 years 3) ability to read, write and understand German 4) estimated life expectancy >6 months 5) access to a telephone 6) living within a 1 hour car ride from the clinic

Exclusion criteria: 1) patients with a family caregiver who was involved substantially in their pain self-management 2) hospitalization for ≥2 weeks during the 10 week intervention period

N total at baseline: Intervention: 19 Control: 20

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 61 ± 11 C: 59 ± 11

Sex: I: 47% M C: 55% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

PRO-SELF education program

6 visits (max 1 hour) and 4 phone calls (5-10 minutes) over 10 weeks by intervention nurse

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Standard treatment

With same number of visits as intervention group, but general health was discussed |

Length of follow-up: 22 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 11 (58%) Reasons not described

Control: 10 (50%) Reasons not described

Incomplete outcome data: Intention to –treat analysis,

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Pain intensity: (NRS 0-10) Average pain: mean Baseline I: 3.80 (2.01); N=19 C: 4.18 (1.79); N=20

6 weeks I: 2.58 (1.73); N=15 C: 2.66 (1.89); N=17

10 weeks I: 2.54 (1.87); N=12 C: 2.98 (2.31) ;N=15

14 weeks I: 2.74 (1.59); N=11 C: 2.42 (1.84); N=11

22 weeks I: 2.60 (2.21) C: 2.81 (2.07)

Self-efficacy: (SEQ 0-100), median Baseline I: 57.7 (46.7/66.3); N=19 C: 59.3 (52.0/64.7); N=20

6 weeks I: 69.3 (56.0/86.7); N=15

10 weeks I: 68.3 (58.5/82.7); N=12 C: 70.0 (61.3/77.3); N=15

14 weeks I: 67.3 (59.3/75.3); N=11 C: 68.7 (53.3/75.5); N=11

22 weeks I: 70.0 (59.2/85); N=8 C: 64.3 (54.2/78.7); N=10 |

Author’s conclusion:

Pain self-management related knowledge improved significantly and effect sizes for pain reduction were determined by this pilot study. Findings from this pilot RCT provide the basis for planning a larger RCT |

|

Koller, 2018 |

Type of study: pilot RCT

Setting: Inpatient

Country: Germany

Source of funding: Non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria: patients had pain scores of 3 or higher out of 10, they needed to self-manage their pain after discharge, had a life expectancy greater than 3 months as assessed by the treating physicians, and could understand, read, and write German.

Exclusion criteria Patients were excluded if the treating physician perceived severe cognitive deficits that would prevent patients from participating actively in selfmanagement support.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 19 Control: 20

Important prognostic factors2: For example age (SD): I: 55.3 (10.2) C: 58.1 (11.2)

Sex: I: 40.0% M C: 63.2% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

• The intervention consisted of an in-hospital visit before discharge and telephone calls after discharge. • In-person visits after discharge were scheduled only if patients had routine follow-up visits due to their cancer treatment. • Laminated cards were used to visualize the intervention's content for the patients. • Patients received a corresponding booklet that summarized the information from the intervention session and a pillbox to organize their oral medication. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

• Received routine cancer care that did not include any cancer pain self-management support. • After the 6-week study period, patients in the CG were offered pain self-management support. |

Length of follow-up: 6 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention in-hospital (n=1)/1 week (n=5)/6 weeks (n=3) Reasons:

Control in-hospital (n=1)/1 week (n=4)/6 weeks (n=1) Reasons:

Incomplete outcome data: See above

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Average pain T0 I: 4.0 (1.56) C: 4.9 (1.41)

Average pain change T1 I: -1.43 (SD 1.95); N=14 C: -1.09 (SD 1.97); N=11

Average pain change T2 I: -2.45 (SD 1.51); N=11 C: -1.71 (SD 1.77); N=14

Self-efficacy T0 I: 3.1 (1.48) C: 3.1 (1.01)

Change in self-efficacy T1 I: 0.14 (2.25); N=14 C: -0.86 (1.59); N=11

Change in self-efficacy T2 I: 1.57 (1.44); N=11 C: 0.20 (1.53); N=14

QoL physical health T0 I: 27.1 (8.61) C: 26.3 (6.05)

Change in physical QoL T1 I: 1.04 (6.01); N=13 C: -0.58 (3.91); N=11

Change in physical QoL T2 I: 9.46 (13.03); N=12 C: 3.39 (7.52); N=14

QoL mental health T0 I: 42.9 (12.02) C: 45.9 (7.91)

Change in mental QoL T1 I: 7.35 (18.04); N=13 C: -1.46 (14.70); N=11

Change in mental QoL T2 I: 9.48 (15.16); N=12 C: 4.11 (13.38); N=14 |

Author’s conclusion: The core effects of the interventions seem to involve function-related outcomes as well as self-efficacy. Because these effects are most meaningful for patients with cancer-related pain, the contribution of ANtiPain to physician-based pharmaceutical cancer pain management may be exceptionally valuable. Therefore, ANtiPain may be a promising intervention to improve cancer pain management when integrated into clinical practice. |

|

Kravitz, 2011/ 2012 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: outpatients

Country: United States

Source of funding: non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria: 1) cognitively intact, English speaking adults with cancer 2) 18-80 years 3) lung, breast, prostate, head or neck, esophageal, colorectal, bladder or gynecologic cancer 4) worst pain score ≥4 (0-10 scale) for the past two weeks or pain that interfered “moderately” with functioning

Exclusion criteria: 1) surgical procedure scheduled within 6 weeks 2) enrolment in hospice 3) followed by pain management specialist beyond a single consultation 4) inability to receive and/or complete mailed enrolment materials

N total at baseline: Intervention: 157 Control: 150

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 60 ± 9 C: 57 ± 10

Sex: I: 22% M C: 20% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Tailored education and coaching:

Self-administered questionnaire, followed by conversation with trained health educator And follow-up phone calls at 2, 6 and 12 weeks

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Enhanced usual care |

Length of follow-up: 12 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 15 (12%) Reasons: 2 deceased, 5 too sick, 8 reason unknown

Control: 18 (13%) Reasons: 1 deceased, 3 too sick, 14 reason unknown

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: 126 / 157 analyzed (80%) Reasons: 27 did not receive intervention, 4 lost to follow-up

Control: 132/150 analyzed (88%) Reasons: 15 did not receive intervention, 3 lost to follow-up

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Pain intensity: (0-10 scale) 2 week I: 6.2 (2.1); N=121 C: 6.2 (2.1); N=128

6 week I: 6.1 (2.2); N=120 C: 5.8 (2.2); N=126

12 week I: 5.9 (2.3); N=115 C: 5.6 (2.5); N=117

Self-efficacy: (CPSE) Pain control self-efficacy, scale 1–5 week 2 I: 3.7 (1.1); N=121 C:3.6 (1.0); N=128

week 6 I: 3.4 (1.1); N=120 C: 3.4 (1.1); N=124

week 12 I: 3.4 (1.2); N=114 C:3.5 (1.2); N=116

SF-12; scale 0-100 Week 6: Mental health score I: 45.9 (10.9); N=115 C:46.3 (11.0); N=123

Physical health score I: 33.2 (9.9); N=115 C: 32.4 (10.3); N=123 |

Author’s conclusion: Tailored intervention and coaching, compared with enhanced usual care, resulted in improved pain communication self-efficacy and temporarily improvement in pain –related impairment, but no improvement in pain severity. |

|

Musavi, 2021 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: Oncology Specialty Clinic

Country: Iran

Source of funding: academic |

Inclusion criteria: 18–80 years old, having a pain score of 3–10 on the VAS scale, being able to perform pain self-management, having the ability to communicate, having written and reading literacy, and also having no history of using complementary medicine approaches in the past or at present

Exclusion criteria: inability to participate in the study due to the disease’s deterioration or death and not completing the questionnaires

N total at baseline: Intervention: 40 Control: 35

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 47.80±12.23 C: 46.28±8.31

Sex: I: 45 % M C: 37.1 % M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

• The needs assessment form was delivered to the intervention group patients to complete. • Then, pain self-management education was performed in the three steps of providing information, skills development and guidance in the intervention group. • First step was accomplished by providing information in the hospital and at the time of hospitalization. • Second step, the patients were practically trained to use the VAS scale and implement complementary medicine approaches, face-to-face and in the presence of the accompanying person. They were also taught how to perform pharmaceutical pain relief. • Third step, guidance, included weekly and monthly follow-up evaluation of pain severity and the quality of life. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Routine training.

An educational pamphlet was provided to the control group at the end of the research. |

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: N=7 (8.5%) in total, not reported per arm. Reasons include increased pain and the deterioration of the patient’s condition, which made them reluctant to continue.

Incomplete outcome data: See above |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Pain severity: Baseline I: 63.75±18.44 C: 67.14±20.00

1 month I: 35.41±23.31 C: 70.95±20.34

3 month I: 37.08±16.66 C: 78.57±14.89

General QoL Baseline I: 48.12±15.38 C: 39.76±12.47

1 month I: 77.91±13.41 C: 51.66±12.75

3 months I: 78.33±12.90 C: 35.71±14.93 |

Author’s conclusion: This study revealed a positive impact of pain self-management on reducing pain severity and improving the indicators of the quality of life in patients with metastatic cancer. It is then recommended that nurses, nursing students, and other healthcare team members apply these findings to effectively instruct metastatic cancer patients and their families in pain control. Empowering patients in pain self-management can reduce the costs imposed on families and the health system. |

|

Raphaelis, 2020 |

Type of study: multi-center RCT

Setting: Oncology Specialty Clinic

Country: Austria

Source of funding: non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria: over 18 years old, had cancer-related pain ≥3 within the last 2 weeks on an 11-point NRS, or a regular cancer pain medication and a necessity to practice pain-self-management after discharge

Exclusion criteria: cognitive, linguistic, emotional, or physical problems that would hamper study participation

N total at baseline: Intervention: 61 Control: 92

Important prognostic factors2: For example age (IQR) : I: 58.6 (52-68) C: 58.9 (49-73)

Sex: I: 49 % M C: 43 % M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

A face-to-face in-hospital session by a trained nurse to prepare discharge according to key strategies, information on pain self-management, and skills building. After discharge, cancer pain self-management was coached via phone calls. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Standard care: routine pain assessment, documentation and pain medication but not structured pain self-management support. |

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention During allocation (n=16)/ T1 (N=11)/ T2 (N=4)/ T3 (N=7)

Control During allocation (n=0)/ T1 (N=20)/ T2 (N=7)/ T3 (N=7)

Incomplete outcome data: See above |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Pain severity: Average pain Presented graphically. Both groups show a reduction in pain scores from baseline, to 2 weeks, 4 weeks and 8 weeks.

Self-efficacy No data available, but the group-by-time effect was significant for self-efficacy (p = .033)

QoL (generic question of the EORTC-C30) Presented graphically. Both groups show a very slight increase in QoL score, although the increase is steeper from baseline to 2 weeks for the intervention group

|

Author’s conclusion: The implementation of ANtiPain improved meaningful patient outcomes on wards that applied the intervention routinely. Our analyses showed that the implementation benefited from being embedded in larger scale projects to improve cancer pain management and that the selection of wards with a high percentage of oncology patients may be crucial.

Note: |

|

Rustoen, 2014 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: outpatients

Country: Norway

Source of funding: non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria: Adult (≥18 years old) outpatients with cancer who were able to read, write, and understand Norwegian were recruited for this study. Patients had a Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) score of 50 or greater (range, 60Y90), an average pain intensity score of 2.5 or greater on a 0- to 10-point NRS, and radiographic evidence of bone metastasis.

Exclusion criteria: None

N total at baseline: Intervention: 87 Control: 92

Important prognostic factors2: For example age (SD): I: 64.3 (11.4) C: 66.8 (12.7)

Sex: I: 47.1% M C: 55.4 % M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Specially trained oncology intervention nurse visited the patients in their home at Weeks 1, 3 and 6 and conducted telephone interviews at Weeks 2, 4 and 5. • At the Week 1 visit, the PRO-SELF nurse conducted an academic detailing session. • At Weeks 2, 4 and 5, the PRO-SELF nurse contacted patients by phone and reviewed their pain intensity scores and analgesic intake. • At Weeks 3 and 6, the PRO-SELF nurse made home visits where the educational material was reinforced, and additional coaching about pain management took place. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

• A booklet about cancer pain management • Home visits and nurse telephone interviews same with IG Pain management diary recorded their pain intensity scores and analgesic intake |

Length of follow-up: 6 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: Baseline: 6 (6.5%) did not fill in the pain diary Post-test: 12 (13%) did not fill in the pain diary

Control: Baseline: 10 (11.5%) did not fill in the pain diary Post-test: 20 (23%) did not fill in the pain diary

Incomplete outcome data: See above |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Pain intensity: Presented graphically. A slight decrease in average pain was shown, with a similar effect in both groups.

|

Author’s conclusion: Possible reasons for the lack of efficacy include an inadequate dose of the psychoeducational intervention, inadequate changes in analgesic prescriptions, and/or the impact of attention provided to the control group. Additional research is needed to evaluate the efficacy of psycho-educational interventions to relieve pain in patients with advanced cancer. |

|

Syrjala, 2008 |

Type of study: multisite RCT

Setting: outpatients

Country: United States

Source of funding: non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria: 1) cancer diagnosis with disease-related persistent pain 2) ambulatory functional status 3) cancer treatment expected to be stable over the next 6 months 4) age over 18 5) English reading and writing proficiency adequate to participate in intervention and assessment

Exclusion criteria: 1) active alcohol or other substance abuse 2) major psychiatric diagnosis

N total at baseline: Intervention: 48 Control: 45

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 58 ± 13 C: 54 ± 12

Sex: I:42 % M C:29 % M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Pain education plus training (30-45) including a 15 minute video and patient could take notes

Plus

Phone call after 72 hrs (10 min) |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Nutrition education plus training (30-45) including a 15 minute video and patient could take notes

Plus

Phone call after 72 hrs (10 min)

|

Length of follow-up: 6 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 20 (43%) Reasons: 7 too ill, 14 died, 1 voluntarily dropped

Control: 20 (47%) Reasons: 6 too ill, 13 died, 2 voluntarily dropped, 1 cognitive impairments

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: 3 (7%)

Control: 10 (22%)

(Reasons not described) |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Pain intensity: (BPI 0-10) Average pain: -0.81 ± 0.36 points lower in video + booklet group compared to control (p=0.03) (change from baseline) Graph shows clinically relevant difference between groups at 1 month, but not at the other time stamps

Worst pain: 0.27 ± 0.38 points lower in video + booklet group compared to control (NS)

|

Author’s conclusion: Using video and print materials with brief individualized training, effectively improved pain management over time for cancer patients of varying diagnostic and demographic groups |

|

Knoerl, 2018 |

Type of study: pilot RCT

Setting: outpatients

Country: USA

Source of funding: none reported |

Inclusion criteria: 1) were older than 25 years of age, 2) self-reported ≥4 of 10 worst CIPN pain that persisted 3 months or longer after the cessation of neurotoxic chemotherapy, 3) had at least National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events grade 1 sensory CIPN 4) had a stable analgesic medication regimen (≤10% change in dosage in the 2 weeks before study enrollment) 5) were able to access/use a computer.

Exclusion criteria: 1) a prognosis of <3 months 2) peripheral neuropathy from other causes 3) planned to receive neurotoxic chemotherapy while enrolled in the study 4) participated in cognitive-behavioral pain management in the past.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 30 Control: 30

Important prognostic factors2: For example age (SD): I: 58.93 (9.33) C: 63.37 (8.36)

Sex: I: 23% M C: 27% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Usual care from primary provider

Plus

8-week Proactive Self-Management Program for Effects of Cancer Treatment (PROSPECT): Participants completes a link ‘Steps For Me’. Website recommends modules based on patient’s responses. Patient may use modules as much as they desired; no additional encouragement to access modules were made

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Usual care from primary provider; received access to intervention after completion of study-related surveys |

Length of follow-up: 8 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: Baseline: N=1 (3%) Reasons: dropped out

Later lost to follow-up: N=6 (21%) Reasons: unable to contact (n=3); personal decision (n=3)

Control: Baseline: N=2 (7%) Reasons: dropped out

Later lost to follow-up: N=4 (14%) Reasons: unable to contact (n=3); personal decision (n=1)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention 19/23 completed the primary aim 19/23 completed the secondary aim

Control 19/24 completed the primary aim 23/24 completed the secondary aim

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Pain Intensity: Average pain, mean (SD)

Baseline I: 4.37 (1.89) C: 3.91 (2.52)

Week 4 I: 4.37 (2.11) C: 5.25 (2.36)

Week 8 I: 4.58 (1.87) C: 5.35 (1.99)

QoL scale 0-100, mean (SD) EORTC QLQ CIPN

CIPN sensory Week 4 I: 44.80 (23.10) C: 41.67 (18.70)

CIPN sensory Week 8 I: 40.41 (18.66) C: 41.95 (17.37)

CIPN Motor Week 4 I: 30.23 (23.59)

CIPN Motor Week 8 I: 26.91 (17.71) C: 22.75 (13.3) |

Author’s conclusion: This pilot study provides preliminary evidence supporting the efficacy of a self-guided cognitive-behavioral pain management intervention for improving worst pain intensity in individuals with chronic painful CIPN |

|

Valenta, 2022 |

Type of study: multicenter RCT

Setting: outpatients

Country: Switzerland

Source of funding: non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria: 1) experienced any type of cancer pain with an average pain of >3 on a 0–10 numeric rating scale (NRS) during the last two weeks 2) had an estimated life expectancy of >6 months; 3) were aged ≥18 years; 4) were able to understand, read, and write German 5) had access to a telephone

Exclusion criteria: 1) had cognitive dysfunction or hearing impairment 2) were hospitalized for >2 weeks during the study 3) experienced only neuropathic pain

N total at baseline: Intervention: 18 Control: 16

Important prognostic factors2: For example age (SD): I: 66.6 (14.5) C: 64.1 (11.0)

Sex: I: 65% M C: 56% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

PRO-SELF© Plus Pain Control Programs based on three key strategies: nurse coaching, self-care skills building to manage pain and associated

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

usual care (i.e., their physicians assessed pain and prescribed analgesic medications) |

Length of follow-up: 6 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up:

Intervention: Baseline: N=1 (5.6%) Reasons: too ill

During study period: N=5 (29.4%) Reasons: family caregiver too sick (n=1); too ill (n=1); hospitalized (n=1); died (n=2)

Control Baseline: N=7 (43.8%) Reason: too ill (n=3); hospitalized > 2wk (n=1); died (n=2); no pain anymore (n=1)

During study period: N=0 Reasons: -

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Pain intensity: Average pain

Week 0 I: 4.3 (1.8); N=17 C: 3.7 (1.3); N=9

Week 4 I: 2.6 (1.4); N=12 C: 3.0 (1.1); N=9 Week 6 I: 2.0 (1.2); N=12 C: 3.1 (1.3); N=9

SEQ score Week 0 I: 69.2 (18.5); N=17 C: 69.9 (10.1); N=9

Week 4 I: NA C: NA

Week 6 I: 79.9 (17.8); N=12 C: 67.3 (12.8); N=9 |

Author’s conclusion: This study was the first to test the efficacy of a psychoeducational cancer pain self-management intervention in a German-speaking context, with most patients receiving palliative care. Clinicians can recommend the use of pain management diaries. Tailoring interventions to an individual's situation and dynamic pain trajectory may improve patients' pain self-management.

|

|

Kelleher, 2021 |

Type of study: pilot RCT

Country: USA

Source of funding: non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria: 1) ≥21 years old, 2) completed active cancer treatment 3) reported pain and psychological distress at ≥3 on a 0-10 scale since completing cancer treatment 4) English-speaking

Exclusion criteria: 1) cognitive impairment or severe psychiatric condition based on chart review 2) receipt of pain coping skills training <6 months, 3) initial diagnosis of metastatic cancer

N total at baseline: Intervention: 14 Control: 17

Important prognostic factors2: For example Age (SD) 59.5 (10.5), not reported per group

Sex: 61% (not reported per group)

Groups comparable at baseline? NR

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Telephone-based coping skills training (CST): five 45-60 minute sessions of a cognitive-behavioral theory-based protocol to manage pain and distress

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Standard care: informational pamphlets related to survivorship health and cancer center services |

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: During study period: N=1 (5.9%) Reasons: lost to follow-up

3 months N=1 (6.3%) Reasons: lost to follow-up

Control: N=0 (0%)

Incomplete outcome data: NR

|

Outcome measures and effect size

pain severity (4-item Pain Severity subscale of the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) scale 0-10) baseline I: 2 [SD=2]; C: 2 [SD=2];

post-treatment I: 3 [SD=2]; C: 2[SD=2]

3-month follow-up I: 2 [SD=2]) C: 1 [SD=2]

self-efficacy for pain control (Self- Efficacy for Pain Management subscale of the Chronic Pain Self-Efficacy Scale; 10-100) post-treatment I: 71 [SD=24] C: 66 [SD=23]

3-month follow-up I: 72 [SD=27] C: 65 [SD=25]

HRQoL (27-item Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G); scale 0-108) baseline I: 80 [SD=14]; C: 76 [SD=12]

posttreatment I: 80 [SD=16]; C: 80 [SD=13]

3-month follow-up I: 83 [SD=15]) C: 77 [SD=15]

|

Author’s conclusion: Findings suggest that a telephone-based CST intervention has strong feasibility, evidenced by accrual, low attrition, and adherence to intervention sessions and assessments. Likewise, participant engagement and acceptability with CST were high. |

|

Kwekkeboom, 2012 |

Type of study: pilot RCT

Country: USA

Source of funding: non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria: Participants were receiving treatment for advanced (metastatic or recurrent) colorectal, lung, prostate, or gynecologic cancers and had experienced pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbance in the past week. To qualify, severity of at least two of the three symptoms had to be rated as 3 or more on a 0-10 NRS.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with postoperative or neuropathic pain were excluded, as were persons who had been hospitalized for mental health reasons within the last three months.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 43 Control: 43

Important prognostic factors2: For example Age (SD): I: 60.44 (10.76) C: 60.14 (11.54)

Sex: I: 33% M C: 49% M

Groups comparable at baseline? groups did not differ on study variables at Time 1, with the exception of depressed mood. Participants in the waitlist group reported more depressed mood (mean [SD] = 10.07 [8.24]) than those in the intervention group. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

patient-controlled cognitive-behavioral (CB) intervention The 12 CB strategies were presented in 4 categories: symptom-focused imagery, nature-focused imagery, relaxation exercises, and nature sounds

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Waitlist, usual care |

Length of follow-up: 8 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 5 (11.6%) Reasons: discontinued intervention (n=5)

Control: N = 1 (2%) Reasons: discontinued intervention

Incomplete outcome data: A per-protocol analysis was conducted

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Pain intensity: (NRS 0-10) Baseline I: 1.97 (1.64); N=43 C: 2.49 (1.88); N=43

End of week 2 I: 1.65 (1.61); N=36 C: 2.23 (1.96); N=42

|

Author’s conclusion:

Findings suggest that the CB intervention may be an efficacious approach to treating the pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbance symptom cluster. |

|

Eaton, 2021 |

Type of study: pilot RCT

Country: USA

Source of funding: non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria: 1) having moderate or higher pain intensity on average during the last week (3 or greater on a 0-to-10 pain intensity numeric scale) 2) having completed active cancer treatment other than hormonal or maintenance therapy 3 months or longer ago 3) being 18 years or older 4) having functional fluency in English 5) being able and willing to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria: NR

N total at baseline: Intervention: 21 Control: 19

Important prognostic factors2: For example Age (SD): I: 49.1 (13.06) C: 56.42 (12.39)

Sex: I: 24% M C: 21% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

4 weeks of listening to a hypnosis recording daily (relaxation induction followed by suggestions for relaxation and comfort, as well as posthypnotic suggestions for permanence of the benefits experienced with the recording and for self-hypnosis practice)

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Wait-list control |

Length of follow-up: 8 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: Did not receive intervention N = 1 (%)

Did not complete week 4 N=1 (5%)

Did not complete week 8 N=5 (24%)

Control: Did not receive intervention N = 5 (26%)

Did not complete week 4 N=1 (5%)

Did not complete week 8 N=5 (26%)

Incomplete outcome data: As above mentioned

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Pain intensity: (NRS 0-10) Baseline I: 6.62 (1.47); N=21 C: 6.89 (1.49); N=19

week 4 I: 6.15 (2.18); N=20 C: 6.61 (1.38); N=18

Week 8 I: 6.06 (2.14); N=16 C: 6.57 (1.79); N=14 |

Author’s conclusion:

The intervention was feasible and acceptable among the majority of the 40 participants, but the single recording and variability in dose (e.g., number of times the recording was listened to) may have limited the intervention’s effect in reducing pain. However, for a substantial portion of the participants, the reduction in pain was found to be clinically significant. |

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Bennett, 2021 |

Probably yes;

Reason: A computer-generated minimisation programme incorporating a random element was used to randomise participants to either the UC plus SSM arm or the UC arm. |

Unclear;

Reason: Not reported |

Probably no;

Reason: Participants, clinicians, research nurses in the recruiting clinics and palliative care nurses were, of necessity, aware of treatment allocation, but the collection of patient outcomes via the IMPACCT trial researcher was blinded. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. Adequate imputation methods (multiple imputation) were used. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns (all outcomes)

Reason: lack of blinding

|

|

Jahn, 2014 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: 1) Pair-matched randomization of patients on a ward 2) concurrently on all wards prior to study 3) by a reproducible SAS PROC PLAN 4) by an external department |

Probably yes;

Reason: the allocation procedure on the cluster and individual levels was concealed by an external department. |

Definitely no

Reason: the patients were not informed of their group assignment; however, the intervention nurses and assessment nurses were not blinded, which might have resulted in patients becoming aware of their group assignment due to nurses' unsealing of information |

Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was similar in both groups. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns (all outcomes)

Reason: lack of blinding

|

|

Koller, 2013 |

Probably yes:

Reason: Computerized permuted blocks procedure, 1:1.

|

Probably yes;

Reason: Sequentially numbered opaque envelopes |

Probably no;

Reason: Clinicians and outcome assessors were blinded. Participants were not. |

Probably no

Reason: Loss to follow-up was frequent (almost half in both groups). |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns (all outcomes)

Reason: lack of blinding, loss to follow-up

|

|

Koller, 2018 |

Probably yes;

Reason: computerised procedure to generate the randomisation list |

Probably yes;

Reason: Sequentially numbered opaque envelopes |

Probably no;

Reason: no blinding for participants and research nurses |

Probably yes;

Reason: the missing outcome data were balanced in numbers across the groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups |

Probably yes;

Reason: all relevant outcomes seem reported, however it is not sure the trial was registered before the study was conducted |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns (all outcomes)

Reason: lack of blinding

|

|

Kravitz, 2012 |

Probably yes;

Reason: Computer-generated blocked randomization |

Unclear;

Reason: not reported |

Probably no;

Reason: Patients (but not physicians or study personnel) were aware of their assigned intervention; |

Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was similar in both groups. |

Probably no;

Reason: study protocol is not available. Results for two follow-up periods for SF-12 outcomes are missing |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns (all outcomes)

Reason: lack of blinding

|

|

Musavi, 2021 |

Probably yes;

Reason: A statistician prepared the randomization list. |

Probably yes;

Reason: sealed envelopes were used |

Definitely no;

Reason: the study is not blinded |

Probably no

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent and assumably similar in both groups. No ITT analysis was done, hence dropouts were not analyzed. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: all relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns (all outcomes)

Reason: No blinding, loss to follow-up

|

|

Raphaelis, 2020 |

Probably no;

Reason: randomization was performed on ward level with a stepped wedge approach. |

Unclear;

Reason: not reported |

Probably no

Reason: Study nurses who collected all data for T1-T3 via post or online questionnaires were blinded to group allocation. Blinding of subjects is not reported, but they are assumed to be unmasked |

Probably yes;

Reason: loss to follow-up was similar in both groups |

Definitely yes;

Reason: all relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns (all outcomes)

Reason: lack of blinding

|

|

Syrjala, 2008 |

Probably yes;

Reason: Randomly assigned in blocks based on stratification |

Unclear;

Reason: not reported |

Probably no

Reason: physicians and nurses were not informed of patient randomizations, but patients potentially could reveal their randomization by bringing study materials to medical appointments |

Probably no;

Reason: missing data. Bias due to possible violation of intention to treat analysis |

Definitely yes;

Reason: all relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns (all outcomes)

Reason: lack of blinding, loss to follow-up

|

|

Rustoen, 2014 |

Probably no;

Reason: randomization was performed by lot. No further details. |

Unclear;

Reason: not reported |

Probably no;

Reason: Study protocol mentions blinding of subjects, however this seems impossible concerning the intervention. Study was assumed to be unmasked. |

Probably yes;

Reason: loss to follow-up is infrequent and similar in both groups. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: all relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns (all outcomes)

Reason: no blinding

|

|

Knoerl, 2018 |

Probably no;

Reason: study was randomized, but no method of randomization is described. |

Unclear;

Reason: not reported |

Probably no;

Reason: subjects were not blinded. Study protocol mentions blinding of the investigator. |

Probably yes;