ACTH bij ASS bij volwassenen

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de effectiviteit van farmacotherapie (zoals ACTH) voor volwassenen met een ASS?

Aanbeveling

Adrenocorticotroop hormoon (ACTH)

De werkgroep ziet geen plaats voor ACTH in de medische behandeling van ASS-kernsymptomen bij volwassenen.

Overwegingen

- De twee gevonden RCT'S zijn uitgevoerd bij kinderen met ASS, maar tonen ernstige methodologische beperkingen.

- HPA-as-secretiepatronen zijn seksespecifiek: vooral bij meisjes zijn deze hoger dan bij jongens.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Neuropeptiden beïnvloeden het centrale zenuwstelsel, waar ze kunnen optreden als neurotransmitter, neurohormoon, dan wel neuromodulator. De neuromodulator moduleert de activititeit van de klassieke neurotransmittersystemen (Gispen, 1980; Versteeg, 1980). Diermodellen hebben de functie van het adrenocorticotroop hormoon (ACTH) in verband gebracht met een aantal functies, waarvan de rol in sociaal gedrag, vooral voor autismespectrumstoornissen relevant is. Zo rapporteerden Niesink en van Ree (1983) dat een synthetische analoog (ORG 2766) van ACTH een omgevingsgeïnduceerde ontregeling van sociaal gedrag normaliseerde bij ratten. ORG 2766 werkt exclusief ter hoogte van het centrale zenuwstelsel en heeft geen perifeer effect op de bijnier.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Samenvattend kan worden gezegd dat de twee geïncludeerde placebogecontroleerde onderzoeken enig bewijs bevatten voor de werkzaamheid van adrenocorticotroop hormoon op de ernst van de symptomen bij kinderen met ASS. Maar de resultaten zijn inconsistent wat betreft het behandelingseffect voor appelerend probleemgedrag. En vanwege het geringe effect dat in Buitelaar e.a. (1992) melden en de kleine steekproefomvang is de kwaliteit van de bewijzen geregardeerd tot laag of zeer laag. Het bewijs van Buitelaar e.a. (1996) werd ook gedegradeerd, vanwege problemen met de randomisatiemethode. Wellicht is er ook een overlap van deelnemers in de twee onderzoeken die tot dubbeltelling heeft geleid als beide onderzoeken door dezelfde eerste auteur en in dezelfde setting werden uitgevoerd. Tot slot zijn de gegevens van beide onderzoeken indirect omdat ze afkomstig zijn van kinderen met ASS.

Samenvatting literatuur

Selectie van onderzoeken

Er waren geen RCT'S, semi-experimentele, observationele of casuïstische onderzoeken die relevant klinisch bewijs opleverden voor de effectiviteit van adrenocorticotroop hormoon voor gedragsmanagement bij volwassenen met ASS. Vanwege het ontbreken van primaire gegevens en op basis van het expertoordeel van de richtlijnwerkgroep werd besloten om te extrapoleren vanuit onderzoeken over kinderen met ASS. Er werden twee RCT'S (N = 68) gevonden die relevante klinische gegevens bevatten en aan de extrapolatiecriteria voldeden; deze werden geïncludeerd. Beide onderzoeken verschenen tussen 1992 en 1996 in peer-reviewed tijdschriften. Daarnaast werd een onderzoek geëxcludeerd omdat de steekproef minder dan tien deelnemers per arm bevatte, aangezien het een cross-overonderzoek betrof (Buitelaar e.a., 1990). Een overzicht van de geëxcludeerde onderzoeken is te vinden in bijlage 11.

Beide geïncludeerde RCT'S bij kinderen met ASS (zie tabel 5.28) betroffen een vergelijking van adrenocorticotroop hormoon (ORG 2766) met placebo (Buitelaar e.a., 1992; 1996).

Wetenschappelijk bewijs

ACTH: ORG 2766 versus placebo voor gedragsmanagement

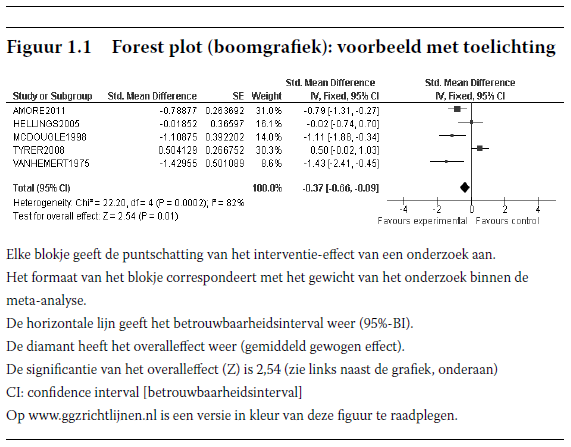

Er waren geen RCT'S, semi-experimentele of observationele onderzoeken die ORG 2766 met placebo vergeleken bij volwassenen met ASS. Op basis van de regels voor de extrapolatie werden gegevens geïncludeerd van een populatie kinderen met ASS. Van de twee geïncludeerde RCT'S naar adreno-corticotroop hormoon voor gedragsmanagement bij kinderen met ASS betroffen beide een vergelijking van ORG 2766 met placebo (zie tabel 5.30). Inconsistente resultaten werden gevonden voor het effect van ORG 2766 op appelerend probleemgedrag. Buitelaar e.a. (1992) vonden bijvoorbeeld bescheiden behandelingseffecten op de subschaal sociaal isolement van de General Assessment Parents Scale (GAP), die voor dit onderzoek werd ontworpen (test voor het totale effect: Z = 2,01; p = 0,04), met betere scores bij deelnemers in de ORG 2766-fase ten opzichte van de placebofase. Buitelaar e.a. (1996) analyseerden dichotome gegevens voor de Aberrant Behaviour Checklist, waarbij zij responders aanmerkten als deelnemers die thuis, op school of in beide omgevingen een betrouwbare verbetering vertoonden op de subschaal sociale terugtrekking van de ABC, maar namen geen significant verschil waar in respons op de behandeling tussen de deelnemers die ORG 2766 en deelnemers die placebo kregen (test voor het totale effect: Z = 0,86; p = 0,39).

Er werd wel consistenter bewijs gevonden voor het effect van ORG 2766 op de ernst/verbetering van de symptomen gemeten met de Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) Scale. Bovendien bracht meta-analyse van gegevens van Buitelaar e.a. (1992; 1996) een statistisch significant behandelingseffect aan het licht van ORG 2766 op ernst/verbetering van de symptomen (test voor het totale effect: Z = 3,69; p = 0,0002), met hogere scores bij deelnemers die ORG 2766 kregen dan bij deelnemers die placebo kregen.

Kosteneffectiviteit

Voor deze richtlijn werd de economische literatuur systematisch doorzocht op onderzoeken naar de kosteneffectiviteit van oxytocine, melatonine, secretine, en adrenocorticotropische hormonen (ACTH) zonder dat deze werden gevonden.

Zoeken en selecteren

Klinisch reviewprotocol

Tabel 5.1 geeft een samenvatting van het reviewprotocol, met uitsluitend de klinische uitgangsvragen (review questions), de informatie over doorzochte databases, en de selectiecriteria die voor dit deel van de richtlijn zijn gebruikt. (Verdere informatie over de zoekstrategie staat in bijlage 6.) Over de biomedische behandelingen heeft de richtlijnwerkgroep besloten dat er geëxtrapoleerd kon worden vanuit literatuur over kinderen met een Ass en, voor zover het gedragsmanagement door middel van farmacotherapie betrof, vanuit literatuur over populaties met een verstandelijke beperking. Een uitzondering hierop werd gemaakt voor de werking van antidepressiva, waarbij duidelijke aanwijzingen bestaan dat er beter niet geëxtrapoleerd kan worden op basis van onderzoeksresultaten bij kinderen met ASS.

Tabel 5.1 Reviewprotocol biomedische interventies

|

Component |

Description |

|

Review question |

(CQ-C4) For adults with autism, what is the effectiveness of biomedical interventions (e.g. dietary interventions, pharmacotherapy, and physical-environmental adaptations)? |

|

Sub-question |

|

|

Objectives |

To evaluate the clinical effectiveness of biomedical interventions for autism. |

|

Population |

|

|

Interventions |

|

|

Comparison |

Placebo-controlled, other active interventions. |

|

Critical outcomes |

Outcomes involving core features of autism (social interaction, communication, repetitive interests/activities); overall autistic behaviour; symptom severity/improvement; management of challenging behaviour; outcomes involving treatment of coexisting conditions; side effects. |

|

Electronic databases |

AMED, Australian Education Index, BIOSIS previews, British Education Index, CDSR, CENTRAL, CINAHL, DARE, Embase, ERIC, IBSS, Medline, PsycINFO, Sociological Abstracts, Social Services Abstracts. |

|

Date searched |

Generic, RCT, QE, OS. Inception of DB up to 09/09/2011. Generic, SR. 1995 up to 09/09/2011. |

|

Study design |

RCTs. The GDG agreed by consensus that where there were no RCTs found in the evidence search, or the results from the RCTs were inconclusive, that the following studies would be included in the review of evidence:

|

|

Review strategy |

|

Samenvatting kinisch reviewprotocol voor de beoordeling van biomedische interventies BIOSIS: BioSciences Information Service of Biological Abstracts; CDSR: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; CENTRAL: Cochrane Central Register of ControlLed Trials; DB: data¬base; CINAHL: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; DARE: Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (Cochrane Library); DSM: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual; ERIC: Education Resources Information Center; GDG: Guideline Development Group; IBSS: International Bibliography of the Social Sciences; ICD: International Classifica- tion of Diseases; RCT: randomised controlled trial; QE: quasi-experiemental; OS: observational study; SR: systematic review

Referenties

- Adams, J.B., Baral, M., Geis, E., Mitchell, J., Ingram, J., Hensley, A., e.a. (2009a). Safety and efficacy of oral DMSA therapy for children with autism spec¬trum disorders, part A: Medical results. BMC Clinical Pharmacology, 9, 16. Raadpleegbaar via: http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1472-6904- 9-16.pdf.

- Adams, J.B., Baral, M., Geis, E., Mitchell, J., Ingram, J., Hensley, A., e.a. (2009b). Safety and efficacy of oral DMSA therapy for children with autism spectrum disorders, part B: Behavioral results. BMC Clinical Pharmacology, 9, 17. Raadpleegbaar via: http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1472-6904- 9-17.pdf.

- Allen, A. (2007, May 28). Thiomersal on trial: The theory that vaccines cause autism goes to court. Retrieved from: http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/medical_examiner/2007/05/thimerosal_on_trial.html.

- Aman, M.G., Burrow, W.H., & Wolford, P.L. (1995a). The Aberrant Behavior Checklist-Community: Factor validity and effect of subject variables for adults in group homes. American Journal of Mental Retardation, 100, 283-292.

- Aman, M.G., Lam, K.S., & Collier-Crespin, A. (2003). Prevalence and patterns of use of psychoactive medicines among individuals with autism in the Autism Society of Ohio. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33, 527-534.

- Aman, M.G., Singh, N.N., Stewart, A.W., & Field, C.J. (1985). The Aberrant Behavior Checklist. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 89, 492-502.

- Aman, M.G., Van Bourgondien, M.E., Wolford, P.L., Wolford, P.L., & Sarphare, G. (1995b). Psychotropic and anticonvulsant drugs in subjects with autism: Prevalence and patterns of use. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 34, 1672-1681.

- Aman, M.G., Lam, K.S., & Van Bourgondien, M.E. (2005). Medication patterns in patients with autism: Temporal, regional, and demographic influences. Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 15, 116-26.

- Andari E, Duhamel JR, Zalla T, Herbrecht E, Leboyer M, Sirigu A. (2010). Promoting social behavior with oxytocin in high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 107, 4389-94.

- Antochi, R., Stavrakaki, C., & Emery, P.C. (2003). Psychopharmacological treatments in persons with dual diagnosis of psychiatric disorders and developmental disabilities. Postgraduate Medicine Journal, 9, 139-146.

- Arendt, J. (1997). Safety of melatonin in long-term use (?). Journal of Biological Rhythms, 12, 673-681.

- Arendt, J. (2003). Importance and relevance of melatonin to human biological rhythms. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 15, 427-431.

- Bailey, A., Le Couteur, A., Gottesman, I., Bolton, P., Simonoff, E., Yuzda, E., & Rutter M. (1995). Autism as a strongly genetic disorder: Evidence from a British twin study. Psychological Medicine, 25, 63-77.

- Balkom, A.L.J.M van, Vliet, I.M. van, Emmelkamp, P.M.G., Bockting, C.L.H., Spijker, J., Hermens, M.L.M., & Meeuwissen, J.A.C.; namens de Werkgroep Multidisciplinaire richtlijnontwikkeling Angststoornissen/Depressie. (2012). Multidisciplinaire richtlijn Angststoornissen (Tweede revisie). Richtlijn voor de diagnostiek, behandeling en begeleiding van volwassen patiënten met een angststoornis. Utrecht: Trimbos-instituut.

- Baron-Cohen, S. (1991). The development of a theory of mind in autism: deviance and delay? Psychiatrie Clinics of North America, 14, 33-51.

- Baron-Cohen, S., Ring, H.A., Bullmore, E.T., Wheelwright, S., Ashwin, C., & Williams, S.C. (2000). The amydala theory of autism. Neuroscience Biobehavioral Reviews, 24, 355-361.

- Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Hill, J., Raste, Y., & Plumb, I. (2001). The 'Reading the Mind in the Eyes' test, revised version: A study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger's syndrome or high-functioning autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42, 241-251.

- Barthelemy, C., Adrien, J.L., Tanguay, P., Garreau, B., Fermanian, J., Roux, S., e.a. (1990). The Behavioral Summarized Evaluation: Validity and reliability of a scale for the assessment of autistic behaviours. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 20, 189-203.

- Bellini, S. (2004). Social skill deficits and anxiety in high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 19, 78-86.

- Belsito, K.M., Law, P.A., Kirk, K.S., Landa, R.J., & Zimmerman, A.W. (2001). Lamotrigine therapy for autistic disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31, 175-181.

- Bent, S., Bertoglio, K., Ashwood, P, Nemeth, E., & Hendren, R.L. (2012). Brief report: Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) in children with autism spectrum disorder: A clinical trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disor-ders, 42, 1127-1132.

- Bethea, T.C., & Sikich, L. (2007). Early pharmacological treatment of autism: A rationale for developmental treatment. Biological Psychiatry, 61, 521-37.

- Birks, J. (2006). Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006(1), Article CD005593. Retrieved September 15, 2011. The Cochrane Library Database.

- Birks, J., & Harvey, R.J. (2006). Donepezil for dementia due to Alzheimer's disease. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews 2006(1), Article CD001190. Retrieved September 15, 2011. The Cochrane Library Database.

- Birks, J., Grimley Evans, J., Iakovidou, V., Tsolaki, M., & Holt, F.E. (2009). Rivastigmine for Alzheimer's disease. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews 2009(2), Article CD001191. Retrieved September 15, 2011. The Cochrane Library Database.

- Borre, R. Vanden, Vermote, R., Buttiëns, M., Thiry, P., Dierick, G., Geutjens, J., e.a. (1993). Risperidone as add-on therapy in behavioural disturbances in mental retardation: a double-blind placebo-controlled cross-over study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 87, 167-171.

- Broadstock, M., Doughty, C., & Eggleston, M. (2007). Systematic review of the effectiveness of pharmacological treatments for adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 11, 335-348.

- Brodkin, E.S., McDougle, C.J., Naylor, S.T., Cohen, D.J., & Price, L.H. (1997). Clomipramine in adults with pervasive developmental disorders: A prospective open-label investigation. Journal of Child & Adolescent Psycho- pharmacology, 7, 109-21.

- Brudnak, M.A., Rimland, B., Kerry, R.E., Dailey, M., Taylor, R., Stayton, B., e.a. (2002). Enzyme-based therapy for autism spectrum disorders: Is it worth another look? Medical Hypotheses, 58, 422-428.

- Bruni O, Ottaviano S, Guidetti V, Romoli M, Innocenzi M, Cortesi F, Giannotti F. (1996). The Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC). Construction and validation of an instrument to evaluate sleep disturbances in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Sleep Research, 5, 251-261.

- Buitelaar, J.K., Engeland, H. van, Kogel, K. de, Vries, H. de, Hooff, J. van, Ree J. van (1992). The adrenocorticotrophic hormone (4-9). analog ORG 2766 benefits autistic children: Report on a second controlled clinical trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 31, 1149-1156.

- Buitelaar, J.K., Dekker, M.E.M., van Ree, J.M., & Engeland, H. van. (1996). A controlled trial with ORG 2766, an ACTH-(4-9). analog, in 50 relatively able children with autism. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 6, 13-19.

- Buitelaar, J.K., Gaag, R.J. van der, & Hoeven, J. van der. (1998). Buspirone in the management of anxiety and irritability in children with pervasive developmental disorders: results of an open-label study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59, 56-59.

- Cahn W, Ramlal D, Bruggeman R, de Haan L, Scheepers FE, van Soest MM, e.a. (2008). Preventie en behandeling van somatische complicaties bij antipsychoticagebruik. Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie, 50, 9.

- Cai, G., Edelmann, L., Goldsmith, J.E., Cohen, N., Nakamine, A., Reichert, JG, e.a. (2008). Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification for genetic screening in autism spectrum disorders: efficient identification of known microduplications and identification of a novel microduplication in ASMT. BMC Medical Genomics, 1, 50. Raadpleegbaar via: http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1755-8794-1-50.pdf.

- Cajochen, C., Krauchi, K., & Wirz-Justice, A. (2003). Role of melatonin in the regulation of human circadian rhythms and sleep. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 15, 432-437.

- Canitano, R. (2007). Epilepsy in autism spectrum disorders. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 16, 61-66.

- Canitano, R., & Scandurra V. (2011). Psychopharmacology in autism: An update. Progress in Neuropsychopharmacoloy & Biological Psychiatry, 35, 18-28.

- Casanova, M.F., Buxhoeveden, D., & Gomez, J. (2003). Disruption in the inhibitory architecture of the cell minicolumn: implications for ASD. Neuroscientist, 9, 496-507.

- Charlton, C.G., Miller, R.L., Crawley, J.N., Handelmann, G.E., O'Donohue, T.L. (1983). Secretin modulation of behavioural and physiological functions in the rat. Peptides, 4, 739-742.

- Chez, M.G., Buchanan, C.P., Bagan, B.T., Hammer, M.S., McCarthy, K.S., Ovruts-kaya, I., e.a. (2000). Secretin and autism: A two-part clinical investigation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 87-94.

- Chez, M.G., Buchanan, C.P., Aimonovitch, M.C., Handelmann, G.E., & O'Donohue TL. (2002). Micronutrients versus standard medication management in autism: A naturalistic case-control study. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 17, 833-837.

- Chez, M.G., Buchanan, T.M., Becker, M., Kessler, J., Aimonovitch, M.C., & Mrazek, S.R. (2003). Donepezil hydrochloride: A double-blind study in autistic children. Journal of Pediatric Neurology, 1, 83-88.

- Chez, M.G., Burton, Q., Dowling, T., Chang, M., Khanna, P., & Kramer, C. (2007). Memantine as adjunctive therapy in children diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorders: an observation of initial clinical response and maintenance tolerability. Journal of Child Neurology, 22, 574-579.

- Chungpaibulpatana, J., Sumpatanarax, T., Thadakul, N., Chantharatreerat, C., Konkaew, M., & Aroonlimsawas, M. (2008). Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in Thai autistic children. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand, 91, 1232-1238.

- Coben, R., & Padolsky, I. (2007). Assessment-guided neurofeedback for autistic spectrum disorder. Journal of Neurotherapy, 11, 5-23.

- Connor, J.R., Boyer, P.J., Menzies, B.S., Dellinger, B., Allen, R.P., Ondo, W.G., & Earley, C.J. (2003). Neuropathological examination suggests impaired brain iron acquisition in restless legs syndrome. Neurology, 61, 304-309.

- Constantino, J.N., Hudziak, J.J., & Todd, R.D. (2003). Deficits in reciprocal social behaviour in male twins: Evidence for a genetically independent domain of psychopharmacology. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 458-467.

- Cook, E.H. Jr., Rowlett, R., Jselskis, C., & Leventhal BL. (1992). Fluoxetine treat- ment of children and adults with autistic disorder and mental retardation. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 31, 739-745.

- Cook, E.H., & Leventhal, B.L. (1996). The serotonin system in autism. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 8, 348-354.

- Croonenberghs, J., Wauters, A., Deboutte, D., Verkerk, R., Scharpe, S., & Maes, M. (2007). Central serotonergic hypofunction in autism: Results of the 5-hydroxy-tryptophan challenge test. Neuro Endocrinology Letters, 28, 449-55.

- D'Eufemia, P., Celli, M., Finocchiaro, R., Pacifico, L., Viozzi, L., Zaccagnini, M., e.a. (1996). Abnormal intestinal permeability in children with autism. Acta Paediatrica, 85, 1076-1079.

- Damasio, A.R., & Maurer, R.G. (1978). A neurological model for childhood autism. Archives of Neurology, 35, 777-786.

- Daniels, J.L., Forssen, U., Hultman, C.M., Cnattingius, S., Savitz, D.A., Feychting, M., & Sparen, P. (2008). Parental psychiatric disorders associated with autism spectrum disorders in the offspring. Pediatrics, 121, e1357-e1362.

- DeLong, G.R., Ritch, C.R., & Burch, S. (2002). Fluoxetine response in children with autistic spectrum disorders: Correlation with familial major affective disorder and intellectual achievement. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 44, 652-9.

- Dhumad, S., & Markar, D. (2007). Audit on the use of antipsychotic medication in a community sample of people with learning disability. The British Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 53, 47-51.

- Di Simplicio, M., Massey-Chase, R., Cowen, P.J., & Harmer, C.J. (2009). Oxytocin enhances processing of positive versus negative emotional information in healthy male volunteers. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 23, 241-248.

- Domes, G., Heinrichs, M., Glascherb, J., Büchel, C., Braus, D.F., & Herpertz, S.C. (2007). Oxytocin attenuates amygdala responses to emotional faces regardless of valence. Biological Psychiatry, 62, 1187-1190.

- Donaldson, Z.R., & Young, L.J. (2008). Oxytocin, vasopressin, and the neurogenetics of sociality. Science, 322, 900-904.

- Dosman, C., Drmic, I., Brian, J., Senthilselvan, A., Harford, M., Smith, R., & Roberts, S.W. (2006). Ferritin as an indicator of suspected iron deficiency in children with autism spectrum disorder: Prevalence of low serum ferritin concentration. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 48, 1008-1009.

- Dosman, C.F., Brian, J.A., Drmic, I.E., Senthilselvan, A., Harford, M.M., Smith, R.W., e.a. (2007). Children with autism: effect of iron supplementation on sleep and ferritin. Pediatrie Neurology, 36, 152-158.

- Drago, F., Pedersen, C.A., Caldwell, J.D., & Prange, A.J. Jr. (1986). Oxytocin potently enhances novelty-induced grooming behaviour in the rat. Brain Research, 368, 287-295.

- Dunn-Geier, J., Ho, H.H., Auersperg, E., Doyle, D., Eaves, L., Matsuba, C., e.a. (2000). Effect of secretin on children with autism: a randomized controlled trial. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 42, 796-802.

- Earley, C.J. (2003). Restless legs syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine, 348, 2103-2109.

- Earley, C.J., Connor, J.R., Beard, J.L., Malecki, E.A., Epstein, D.K., & Allen, R.P (2000). Abnormalities in CSF concentrations of ferritin and transferring in restless legs syndrome. Neurology, 54, 1698-1700.

- Edwards, D.J., Chugani, D.C., Chugani, H.T., Chehab, J., Malian, M., & Aranda, J.V. (2006). Pharmacokinetics of buspirone in autistic children. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 46, 508-514.

- Elia, M., Ferri, R., Musumeci, S.A., Del Gracco, S., Bottitta, M., Scuderi, C., e.a. (2000). Sleep in subjects with autistic disorder: A neurophysiological and psychological study. Brain Development, 22, 88-92.

- Erickson, C.A., Posey, D.J., Stigler, K.A., Mullett, J., Katschke, A.R., & McDougle, C.J. (2007). A retrospective study of memantine in children and adoles¬cents with pervasive developmental disorders. Psychopharmacology, 191, 141-147.

- Esbensen, A.J., Greenberg, J.S., Seltzer, M.M., & Aman, M.G. (2009). A longitudinal investigation of psychotropic and non-psychotropic medication use among adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 1339-1349.

- Evangeliou, A., Vlachonikolis, I., Mihailidou, H., Spilioti, M., Skarpalezou, A., Makaronas, N., e.a. (2003). Application of a ketogenic diet in children with autistic behavior: Pilot study. Journal of Child Neurology, 18, 113-118.

- Fatemi, S.H., Halt, A.R., Stary, J.M., Kanodia, R., Schulz, S.C., & Realmuto, G.R. (2002). Glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 and 67 kDa proteins are reduced in the autistic parietal and cerebellar cortices. Biological Psychiatry, 52, 805-810.

- Findling, R.L. (2005). Pharmacological treatment of behavioural symptoms in autism and pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66, 26-31.

- Findling, R.L., Steiner, H., & Weller, E.B. (2005). Use of antipsychotics in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66, 29-40.

- Fish, B. (1985). Children's psychiatric rating scale. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 21, 753-770.

- Fischer-Shofty, M., Shamay-Tsoory, S.G., Harari, H., & Levkovitz, Y. (2010). The effect of intranasal administration of oxytocin on fear recognition. Neuro-psychologia, 48, 179-184.

- Fombonne, E. (2008). Thimerosal disappears but autism remains. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65, 15-16.

- Francis, P.T., Palmer, A.M., Snape, M., & Wilcock, G.K. (1999). The cholinergic hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: A review of progress. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 66, 137-147.

- Freeman, J.M., Kossoff, E.H., & Hartman, A.L. (2007). The ketogenic diet: one decade later. Pediatrics, 119, 535-543.

- Freeman, B.J. , Ritvo, E.R., Yokota, A., & Ritvo, A. (1986). A scale for rating symptoms of patients with the syndrome of autism in real life settings. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 25, 130-136.

- Fremeau, R.T. Jr., Jensen, R.T., Charlton, C.G., Miller, R.L., O'Donohue, T.L., & Moody, T.W. (1983). Secretin: specific binding to rat brain membranes. Journal of Neuroscience, 3, 1620-1625.

- Gagiano, C., Read, S., Thorpe, L., Eerdekens, M., & Hove, I. van. (2005). Short- and long-term efficacy and safety of risperidone in adults with disruptive behaviour disorders. Psychopharmacology, 179, 629-636.

- Geier, D.A., & Geier, M.R. (2006). A clinical trial of combined anti-androgen and anti-heavy metal therapy in autistic disorders. Neuroendocrinology Letters, 27, 833-838.

- Geier, M., & Geier, D. (2005). The potential importance of steroids in the treatment of autistic spectrum disorders and other disorders involving mercury toxicity. Medical Hypotheses, 64, 946-54.

- Ghaziuddin, M., Ghaziuddin, N., & Greden, J. (2002). Depression in persons with autism: Implications for research and clinical care. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32, 299-306.

- Ghaziuddin, M., & Greden, J. (1998). Depression in children with autism/perva- sive developmental disorders: a case-control family history study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 28, 111-115.

- Gillberg, C., & Billstedt, E. (2000). Autism and Asperger syndrome: Co-existence with other clinical disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 102, 321-330.

- Gillott, A., Furniss, F., & Walter, A. (2001). Anxiety in high-functioning children with autism. Autism, 5, 277-286.

- Gimpl, G. (2008). Oxytocin receptor ligands: a survey of the patent literature. Expert Opinion, 18, 1239-1251.

- Gispen, W.H. (1980). On the neurochemical mechanism of action of ACTH. Progress in Brain Research, 53, 193-206.

- Goodman, W. K., Price, L. H., Rasmussen, S. A., Mazure, C., Fleischmann, R.L., Hill, C.L., e.a. (1989a). The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. development, use, and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46, 1006-1011.

- Goodman, W.K., Price, L.H., Rasmussen, S.A., Mazure, C., Delgado, P., Heninger, G.R., & Charney, D.S. (1989b). The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. II. validity. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46, 1012-1016.

- Gordon N. (2000). The therapeutics of melatonin: a paediatric perspective. Brain & Development, 22, 213-7.

- Goyette, C.H., Conners, C.K., & Ulrich, R.F. (1978). Normative data on revised Conners Parent and Teacher Rating Scales. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 6, 221-236.

- Granpeesheha, D., Tarboxa, J., Dixon, D.R., Wilke, A.E., Allen, M.S., & Bradstreet, J.J. (2010). Randomized trial of hyperbaric oxygen therapy for children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4, 268-275.

- Green, J., Gilchrist, A., Burton, D., & Cox, A. (2000). Social and psychiatric func- tioning in adolescents with Asperger syndrome compared with conduct disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 279-293.

- Green, V.A., Pituch, K.A., Itchon, J., Choi, A., O'Reilly, M., & Sigafoos, J. (2006). Internet survey of treatments used by parents of children with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 27, 70-84.

- Greenhill, L.L., Swanson, J.M., Vitiello, B., Davies, M., Clevenger, W., Wu, M., e.a. (2001). Impairment and deportment responses to different methylphenidate doses in children with ADHD: The MTA titration trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 180-187.

- Gregory, S.G., Connelly, J.J., Towers, A., Johnson, J., Biscocho, D., Markunas, C.A., e.a. (2009). Genomic and epigenetic evidence for oxytocin receptor deficiency in autism. BMC Medicine, 7, 62.

- Gualtieri, C.T. (2002). Psychopharmacology of brain injured and mentally retarded patients. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

- Gualtieri, T., Chandler, M., Coons, T.B., & Brown, L.T. (1989). Amantadine: A new clinical profile for traumatic brain injury. Clinical Neuropharmacology, 12, 258-270.

- Guastella, A.J., Mitchell, P.B., & Dadds, M.R. (2008). Oxytocin increases gaze to the eye region of human faces. Biological Psychiatry, 63, 3-5.

- Guastella, A.J., Einfeld, S.L., Gray, K.M., Rinehart, N.J., Tonge, B.J., Lambert, T.J., & Hickie, I.B. (2010). Intranasal oxytocin improves emotion recognition for youth with autism spectrum disorders. Biological Psychiatry, 67, 692-4.

- Guénolé, F., Godbout, R., Nicolas, A., Franco, P., Claustrat, B., & Baleyte, J.M. (2011). Melatonin for disordered sleep in individuals with autism spectrum disorders: Systematic review and discussion. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 15, 379-87.

- Guy, W. (1976a). Clinical Global Impressions. In W. Guy, ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, revised (DHEW Publ No ADM 76-338) (pp. 218-222). Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health.

- Guy, W. (1976b). Dosage Record and Treatment Emergent Symptoms scale (DOTES). In W. Guy, ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, revised (DHEW Publ No ADM 76-338) (pp. 223-244). Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health.

- Haas, R.H., Rice, M.A., Trauner, D.A., & Merritt, T.A. (1986). Therapeutic effects of a ketogenic diet in Rett syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 1, 225-246.

- Haessler, F., Glaser, T., Beneke, M., Pap, A.F., Bodenschatz, R., Reis, O.; Zuclopenthixol Disruptive Behaviour Study Group. (2007). Zuclopenthixol in adults with intellectual disabilities and aggressive behaviours: Discontinuation study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 190, 447-448.

- Hallett, V., Ronald, A., & Happe, F. (2009). Investigating the association between autistic-like and internalizing traits in a community-based twin sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 48, 618-627.

- Hampson, D., Gholizadeh, S., & Pacey, L. (2012). Pathways to drug development for autism spectrum disorders. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 91, 189-200.

- Handen, B.L., Feldman, H., Gosling, A., Breaux, A.M., & McAuliffe, S. (1991). Adverse side effects of Ritalin among mentally retarded children with ADHD. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30, 241-245.

- Handen, B.L., & Hardan, A.Y. (2006). Open-label, prospective trial of olanzapine in adolescents with subaverage intelligence and disruptive behavioral disor¬ders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45, 928-935.

- Haracopos, D., & Kelstrup, A. (1975). Psykotiskadfard [Psychotisch gedrag]. Kobenhavn: Samaterialer.

- Hardan, A.Y., Jou, R.J., & Handen, B.L. (2004). A retrospective assessment of topiramate in children and adolescents with pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 14, 426-432.

- Heinrichs, M., Baumgartner, T., Kirschbaum, C., & Ehlert, U. (2003). Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychological stress. Biological Psychiatry, 54, 1389-1398.

- Hellings, J.A., Weckbaugh, M., Nickel, E.J., Cain, S.E., Zarcone, J.R., Reese, R.M., e.a. (2005). A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of valproate for aggression in youth with pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 15, 682-692.

- Hellings, J.A., Zarcone, J.R., Reese, R.M., Valdovinos, M.G., Marquis, J.G., Fleming, K.K., & Schroeder, S.R. (2006). A crossover study of risperidone in children, adolescents and adults with mental retardation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 401-411.

- Hemert, J.C.J. van. (1975). Pipamperone (Dipiperon, R3345). in troublesome mental retardates: A double-blind placebo controlled cross-over study with long-term follow-up. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 52, 237-245.

- Hen, M.H. de, & H.M. Geurts. (2008). Is neurofeedback effectief bij kinderen met ADHD? Tijdschrift voor Neuropsychologie, 2, 14-27.

- Hofvander, B., Delorme, R., Chaste, P., Nydén, A., Wentz, E., Stahlberg, O., e.a. (2009). Psychiatrie and psychosocial problems in adults with normal-intelligence autism spectrum disorders. BMC Psychiatry, 10, 9:35.

- Hollander, E., Cartwright, C., Wong, C.M., DeCaria, C. M., DelGuidice-Asch, G., Buchsbaum, M.S., e.a. (1998). A dimensional approach to the autism spectrum. CNS Spectrums, 3, 22-39.

- Hollander, E., Tracy, K., Swann, A.C., Coccaro, E.F., McElroy, S.L., Wozniak, P, e.a. (2003). Divalproex in the treatment of impulsive aggression: Efficacy in cluster B personality disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology, 28, 1186-1197.

- Hollander, E., Bartz, J., Chaplin, W., Phillips, A., Sumner, J., Soorya, L., e.a. (2007). Oxytocin increases retention of social cognition in autism. Biological Psychiatry, 61, 498-503.

- Hollander, E., Chaplin, W., Soorya, L., Wasserman, S., Novotny, S., Russoff, J., e.a. (2010). Divalproex sodium vs placebo for the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology, 35, 990-998.

- Hollander, E., Soorya, L., Chaplin, W., Anagnostou, E., Taylor, B.P., Ferretti, C.J., e.a. (2011). A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine for repetitive behaviors and global severity in adult autism spectrum disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169, 292-299.

- Honigfeld, G., Gillis, R.D., & Klett, C.J. (1966). NOSIE-30: a treatment-sensitive ward behavior scale. Psychological Reports, 19, 180-182.

- Horning, M.S., Blakemore, L.J., & Trombly, P.Q. (2000). Endogenous mechanisms of neuroprotection: Role of zinc, copper, and carnosine. Brain Research, 852, 56-61.

- Horvath, K., & Perman, J.A. (2002). Autism and gastrointestinal symptoms. Current Gastroenterology Reports, 4, 251-258.

- Horvath, K., Stefanatos, G., Sokolski, K.N., Wachtel, R., Nabors, L., & Tildon, J.T. (1998). Improved social and language skills after secretin administration in patients with autistic spectrum disorders. Journal of the Association for Academie Minority Physicians, 9, 9-15.

- Howlin, P. (2000). Outcome in adult life for more able individuals with autism or Asperger Syndrome. Autism, 4, 63-83.

- Huitema, R., & Eling, P. (2008). Neurofeedback: Wat is het waard? Tijdschrift voor Neuropsychologie, 2, 3-13.

- Hyman, S.E., & Nestler, E.J. (1996). Initiation and adaptation: A paradigm for understanding psychotropic drug action. American Journal of Psychiatry, 153, 151-162.

- Insel, T.R., & Winslow, J.T. (1991). Central administration of oxytocin modulates the infant rat's response to social isolation. European Journal of Pharmacology, 203, 149-152.

- Israngkun, P.P., Newman, H.A.I., Patel, S.T., Duruibe, V.A., & Abou-Issa, H. (1986). Potential biochemical markers for infantile autism. Neurochemical Pathology, 5, 51-70.

- Izmeth, M.G.A., Khan, S.Y., Kumarajeewa, D.I., Shivanathan, S., Veall, R.M., & Wiley, Y.V. (1988). Zuclopenthixol decanoate in the management of behavioural disorders in mentally handicapped patients. Pharmatherapeutica, 5, 217-227.

- Jahromi, L.B., Kasari, C.L., McCracken, J.T., Lee, L.S., Aman, M.G., McDougle, C.J., e.a. (2009). Positive effects of methylphenidate on social communication and self-regulation in children with pervasive developmental disorders and hyperactivity. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 395-404.

- Jamain, S., Betancur, C., Quach, H., Philippe, A., Fellous, M., Giros, B., e.a. (2002). Linkage and association of the glutamate receptor 6 gene with autism. Molecular Psychiatry, 7, 302-310.

- Jan, J.E., Freeman, R.D., & Fast, D.K. (1999). Melatonin treatment of sleep/wake cycle disorders in children and adolescents. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 41, 491-500.

- Jan, J.E., & O'Donnel, M.E. (1996). Use of melatonin in the treatment of pediatric sleep disorders. Journal of Pineal Research, 21, 193-199.

- Jarusiewicz, B. (2002). Efficacy of Neurofeedback for Children in the Autistic Spectrum: A Pilot Study. Journal of Neurotherapy, 6, 39-49.

- Jepson, B., Granpeesheh, D., Tarbox, J., Olive, M.L., Stott, C., Braud, S., e.a. (2011). Controlled evaluation of the effects of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on the behavior of 16 children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 575-588.

- Jonsson, L., Ljunggren, E., Bremer, A., Pedersen, C., Landen, M., Thuresson, K. e.a. (2010). Mutation screening of melatonin-related genes in patients with autism spectrum disorders. BMC Medical Genomics, 3, 10. Raadpleegbaar via: http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1755-8794-3-10.pdf.

- Kanner, L. (1943). Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child, 2, 217-250.

- Karsten, D., Kivimaki, T., Linna, S.L., Pollari, L., & Turunen, S. (1981). Neuroleptic treatment of oligophrenic patients: A double-blind clinical multicentre trial of cis(Z)-clopenthixol and haloperidol. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 294, 39-45.

- Kemp, J.A., & McKernan, R.M. (2002). NMDA receptor pathways as drug targets. Nature Neuroscience, 5, 1039-1042.

- Kemper, T., & Bauman, M. (1993). The contribution of neuropathologic studies to the understanding of autism. Neurologic Clinics, 11, 175-187.

- Kendall, T. (2011). The rise and fall of the atypical antipsychotics. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 199, 266-268.

- Kim, J.A., Szatmari, P., Bryson, S.E., Streiner, D.L., & Wilson, F.J. (2000). The prevalence of anxiety and mood problems among children with autism and Asperger syndrome. Autism, 4, 117-132.

- King, B.H., Wright, D.M., Handen, B.L., Sikich, L., Zimmerman, A.W., McMahon, W., e.a. (2001). Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of amantadine hydrochloride in the treatment of children with autistic disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 658-665.

- Kiralp, M.Z., Yildiz, S., Vural, D., Keskin, I., Ay, H., & Dursun, H. (2004). Effectiveness of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the treatment of complex regional pain syndrome. Journal of International Medical Research, 32, 258-262.

- Kirsch I., Deacon B.J., Huedo-Medina T.B., Scoboria A., Moore T.J., Johnson B.T. (2008). Initial severity and antidepressant benefits: a meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration. PLoS Med, 5: 260-8.

- Kirsch, P, Esslinger, C., Chen, Q., Mier, D., Lis, S., Siddhanti, S., e.a. (2005). Oxytocin modulates neural circuitry for social cognition and fear in humans. Journal of Neuroscience, 25, 11489-11493.

- Klin, A., Pauls, D., Schultz, R., & Volkmar, F. (2005). Three diagnostic approaches to Asperger syndrome: implications for research. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35, 221-34.

- Knivsberg, A-M., Reichelt, K-L., H0ien, T., & N0dland, M. (2003). Effect of dietary intervention on autistic behavior. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 18, 247-256.

- Kolevzon, A., Mathewson, K.A., & Hollander, E. (2006). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in autism: A review of efficacy and tolerability. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67, 407-414.

- Kooij, J.J.S. (2009). ADHD bij volwassenen: Diagnostiek en behandeling. Pearson Assessment and Information.

- Korkmaz, B. (2000). Infantile autism: adult outcome. Seminars in Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 5, 164-170.

- Kornhuber, J., Weller, M., Schoppmeyer, K., & Riederer, P. (1994). Amantadine and memantine are NMDA receptor antagonists with neuroprotective properties. Journal of Neural Transmission, 43, 91-104.

- Kosfeld, M., Heinrichs, M., Zak, P.J., Fischbacher, U., & Fehr, E. (2005). Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature, 435, 673-676.

- Krug, D., Arick, J., & Almond, P. (1993). Autism screening instrument for educa- tionalplanning (2nd ed.). Austin, TX: PRO-ED, Inc.

- Lainhart, J.E., & Folstein, S.E. (1994). Affective disorders in people with autism: A review of published cases. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24, 587-601.

- Langworthy-Lam, K.S., Aman, M.G., & Van Bourgondien, M.E. (2002). Prevalence and patterns of use of psychoactive medicines in individuals with autism in the Autism Society of North Carolina. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 12, 311-322.

- Larsen, F.W., & Mouridsen, S.E. (1997). The outcome in children with childhood autism and asperger syndrome originally diagnosed as psychotic: A 30-year follow-up study of subjects hospitalized as children. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 6, 181-190.

- Latif, A., Heinz, P., & Cook, R. (2002). Iron deficiency in autism and Asperger syndrome. Autism, 6, 103-114.

- Leach, R.M., Rees, PJ., & Wilmshurst, P. (1998). ABC of oxygen: hyperbaric oxygen therapy. British Medical Journal, 317, 1140-1143.

- Leu, R.M., Beyderman, L., Botzolakis, E.J., Surdyka, K., Wang, L., & Malow, B.A. (2010). Relation of melatonin to sleep architecture in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 427-433.

- Levy, S.E., Souders, M.C., Wray, J., Jawad, A.F., Gallagher, P.R., Coplan, J., e.a. (2003). Children with autistic spectrum disorders I: comparison of placebo and single dose of human synthetic secretin. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 88, 731-736.

- Levy, S.E., Mandell, D.S., & Schultz, R.T. (2009). Autism. Lancet, 374, 1627-1638.

- Lipton, S.A. (2006). Paradigm shift in neuroprotection by NMDA receptor blockade: Memantine and beyond. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 5, 160-170.

- Lonsdale, D., Shamberger, R.J., & Audhya, T. (2002). Treatment of autism spectrum children with thiamine tetrahydrofurfuryl disulfide: A pilot study. Neuroendocrinology Letters, 23, 303-308.

- Loo, S.K., & Barkley, R.A. (2005). Clinical utility of eeg in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Applied Neuropsychology, 12, 64-76.

- Lubar, J.F., & Shouse, M.N. (1976). EEG and behavioral changes in a hyperkinetic child concurrent with training of the sensorimotor rhythm (SMR): A preliminary report. Biofeedback and Self Regulation, 1, 293-306.

- Lubetsky, M.J., & Handen, B.L. (2008). Medication treatment in autism spectrum disorder. Speakers Journal, 8, 97-107.

- Luteijn, E.F., Serra, M., Jackson, S., Steenhuis, M.P., Althaus, M., Volkmar, F., & Minderaa, R. (2000). How unspecified are disorders of children with a pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified? A study of social problems in children with PDD-NOS and ADHD. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 9, 168-179.

- MacDonald, E., Dadds, M.R., Brennan, J.L., Williams, K., Levy, F., Cauchi, A.J. (2011). A review of safety, side-effects and subjective reactions to intranasal oxytocin in human research. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 36, 1114-1126.

- Maelicke, A., Samochocki, M., Jostock, R., Fehrenbacher, A., Ludwig, J., Albuquerque, E.X.,e.a. (2001). Allosteric sensitization of nicotinic receptors by galantamine, a new treatment strategy for Alzheimier's disease. Biological Psychiatry, 49, 279-288.

- Magnuson, K.M., & Constantino, J.N. (2011). Characterization of depression in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 32, 332-340.

- Malone, R.P., Gratz, S.S., Delaney, M.A., Hyman, S.B. (2005). Advances in drug treatments for children and adolescents with autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. CNS Drugs, 19, 923-934.

- Marshall, T. (2004). Audit of the use of psychotropic medication for challenging behaviour in a community learning disability service. The Psychiatrist, 28, 447-450.

- Marshall, C., & Scherer, S. (2012). Detection and characterization of copy number variation in autism spectrum disorder. Methods in Molecular Biology, 838, 115-135.

- Martin, A., Koenig, K., Anderson, G.M., & Scahill, L. (2003). Low-dose fluvox- amine treatment of children and adolescents with pervasive developmental disorders: A prospective, open-label study. Journal of Autism and Develop- mental Disorders, 33, 77-85.

- Martin, A., Scahill, L., Klin, A., & Volkmar, F.R. (1999). Higher-functioning perva¬sive developmental disorders: rates and patterns of psychotropic drug use. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 923-931.

- Martineau, J., Barthelemy, C., Cheliakine, C., & Lelord, G. (1988). Brief report: An open middle-term study of combined vitamin B6-magnesium in a subgroup of autistic children selected on their sensitivity to this treatment. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 18, 435-447.

- Masters, K.J. (1997). Alternative medications for ADHD [letter]. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 301.

- Matson, J.L., & Hess, J.A. (2011). Psychotropic drug efficacy and side effects for persons with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5, 230-236.

- Matson, J.L., & Neal, D. (2009). Psychotropic medication use for challenging behaviours in persons with intellectual disabilities: an overview. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30, 572-586.

- Matson, J.L., & Shoemaker, M. (2009). Intellectual disability and its relationship to autism spectrum disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30, 1107-1114.

- Matson, J.L., Sipes, M., Fodstad, J.C., & Fitzgerald, M.E. (2011). Issues in the management of challenging behaviour of adults with autism spectrum disorder. CNS Drugs, 25, 597-606.

- McDougle, C.J., Naylor, S.T., Cohen, D.J., Volkmar, F.R., Heninger, G.R., & Price, L.H. (1996). A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of fluvoxamine in adults with autistic disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 53, 1001-1008.

- McDougle, C.J., Brodkin, E.S., Naylor, S.T., Carlson, D.C., Cohen, D.J., & Price, L.H. (1998a). Sertraline in adults with pervasive developmental disorders: A prospective open-label investigation. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 18, 62-66.

- McDougle, C.J., Holmes, J.P., Carlson, D.C., Pelton, G.H., Cohen, D.J., & Price, L.H. (1998b). A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone in adults with autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55, 633-641.

- McDougle, C.J., Stigler, K.A., & Posey, D.J. (2003). Treatment of aggression in children and adolescents with autism and conduct disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 64, 16-25.

- McDougle, C.J., Erickson, C.A., Stigler, K.A., & Posey, D.J. (2005). Neurochemistry in the pathophysiology of autism. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66, 9-18.

- McKenzie, M.E., & Roswell-Harris, D. (1966). A controlled trial of prothipendyl (tolnate). in mentally subnormal patients. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 112, 95-100.

- Meisenberg, G., & Simmons, W.H. (1983). Centrally mediated effects of neurohypophyseal hormones. Neuroscience Biobehavioral Reviews, 7, 263-280.

- Mehl-Madrona, L., Leung, B., Kennedy, C., Paul, S., & Kaplan, B.J. (2010). Micronutrients versus standard medication management in autism: A naturalistic case-control study. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 20, 95-103.

- Melke, J., Goubran Botros, H., Chaste, P., Betancur, C., Nygren, G., Anckarsater, H., e.a. (2008). Abnormal melatonin synthesis in autism spectrum disorders. Molecular Psychiatry, 13, 90-98.

- Miano, S., & Ferri, R. (2010). Epidemiology and management of insomnia in children with autistic spectrum disorders. Pediatric Drugs, 12, 75-84.

- Millward, C., Ferriter, M., Calver, S.J., & Connell-Jones, G. (2008). Gluten- and casein-free diets for autistic spectrum disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008(2), Article CD003498. Retrieved September 15 2011. The Cochrane Library Database.

- Miyamoto, A., Oki, J., Takahashi, S., & Okuno, A. (1999). Serum melatonin kinetics and long-term melatonin treatment for sleep disorders in Rett syndrome. Brain Development, 21, 59-62.

- Modahl, C., Green, L., Fein, D., Morris, M., Waterhouse, L., Feinstein, C.,e.a. (1998). Plasma oxytocin levels in autistic children. Biological Psychiatry, 43, 270-277.

- Moore, M.L., Eichner, S.F., & Jones, J.R. (2004). Treating functional impairment of autism with selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors. Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 38, 1515-1519.

- Mousain-Bosc, M., Roche, M., Polge, A., Pradal-Prat, D., Rapin, J., & Bali, J.P. (2006). Improvement of neurobehavioral disorders in children supplemented with magnesium-vitamin B6. II. pervasive developmental disorder-autism. Magnesium Research, 19, 53-62.

- Munasinghe, S.A., Oliff, C., Finn, J., & Wray, J.A. (2010). Digestive enzyme supplementation for autism spectrum disorders: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 1131-1138.

- Mundy, P. (2003). Annotation, the neural basis of social impairments in autism: The role of the dorsal medial-frontal cortex and anterior cingulate system. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44, 793-809.

- Mundy, P., Delgado, C., Block, J., Venezia, M., Hogan, A., & Seibert, J. (2003). A manual for the Abridged Early Social Communication Scales (ESCS). Coral Gables, FL: University of Miami.

- Munshi, K.R., Oken, T., Guild D.J., Trivedi, H.K., Wang, B.C., Ducharme, P., e.a. (2010). The use of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). for the treatment of pediatric aggression and mood disorders. Pharmaceuticals, 3, 2986-3004.

- Murphy, G.H., Beadle-Brown, J., Wing, L., Gould, J., Shah, A., & Holmes, N. (2005). Chronicity of challenging behaviours in people with severe intellec- tual disabilities and/or autism: a total population sample. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35, 405-418.

- Murray, M.J. (2011). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the context of autism spectrum disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 5, 382-388.

- Myers, SM. (2007). The status of pharmacotherapy for autism spectrum disorders. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 8, 1579-603.

- Nelson, E., & Alberts, J.R. (1997). Oxytocin-induced paw sucking in infant rats. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 807, 543-545.

- Neubauer, R.A., Gottlieb, S.F., & Miale, A. (1992). Identification of hypometabolic areas in the brain using brain imaging and hyperbaric oxygen. Clinical Nuclear Medicine, 17, 477-481.

- NICE. (2009a). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [CG72]. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

- NICE. (2009b). Depression: The treatment and management of depression in adults (Update). [CG90]. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

- NICE. (2009c). Schizophrenia (Update). [CG82]. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

- NICE. (2011). Generalised anxiety disorder andpanic disorder (with or without agoraphobia) in adults. [CG113]. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

- NICE. (2008). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Diagnosis and Management of ADHD in children, youngpeople and Adults. NICE clinical guideline 72, 2008. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

- Nicolson, R., Craven-Thuss, B., & Smith, J. (2006). A prospective, open-label trial of galantamine in autistic disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 16, 621-629.

- Niesink, R.J.M., & Ree, J.M. van. (1983). Normalizing effects of an ACTH 4 9 analog (ORG 2766). on 'disturbed' social behaviour of rats: Implication of endogeneous opioid systems. Science, 221, 960-962.

- Nir, I., Meir, D., Zilber, N., Knobler, H., Hadjez, J., & Lerner, Y. (1995). Brief report: circadian melatonin, thyroid-stimulating hormone, prolactin and cortisol levels in serum of young adults with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 25, 641-654.

- Nolen, W.A., Kupka, R.W., Schulte, P.F.J., Knoppert-van der Klein, E.A.M., Honig, A., Reichart, C.G., e.a.; Richtlijncommissie bipolaire stoornissen van de Commissie Kwaliteitszorg van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie. (2008). Richtlijn bipolaire stoornissen (2e herz. versie). Utrecht: De Tijdstroom.

- Ottaviano, S., Giannotti, F., Cortesi, F., Bruni, O., & Ottaviano, C. (1996). Sleep characteristics in healthy children from birth to 6 years of age in the urban area of Rome. Sleep, 19, 1-3.

- Owley, T., Salt, J., Guter, S., Grieve, A., Walton, L., Avuvao, N. e.a. (2006). A prospective, open-label trial of memantine in the treatment of cognitive, behavioral, and memory dysfunction in pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 16, 517-524.

- Ozonoff, S., Pennington, B.F., & Rogers, S.J. (1991). Executive function deficits in high-functioning autistic individuals: relationship to theory of mind. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 32, 1081-1105.

- Paavonen, E.J., Nieminen-von Wendt, T., Vanhala, R, Aronen, E.T., & Wendt, L. (2003). Effectiveness of melatonin in the treatment of sleep disturbances in children with Asperger disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 13, 83-95.

- Palm, L., Blennow, G., & Wetterberg, L. (1997). Long-term melatonin treatment in blind children and young adults with circadian sleep-wake disturbances. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 39, 319-325.

- Parikh, M.S., Kolevzon, A., & Hollander, E. (2008). Psychopharmacology of aggression in children and adolescents with autism: a critical review of efficacy and tolerability. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 18, 157-178.

- Parker, S.K., Schwartz, B., Todd, J., & Pickering, L.K. (2004). Thimerosal-containing vaccines and autistic spectrum disorder: a critical review of published data. Pediatrics, 114, 793-804.

- Patisaul, H.B., Scordalakes, E.M., Young, L.J., Rissman, E.F. (2003). Oxytocin, but not oxytocin receptor, is regulated by oestrogen receptor beta in the female mouse hypothalamus. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 15, 787-93.

- Patzold, L.M., Richdale, A.L., & Tonge, B.J. (1998). An investigation into sleep characteristics of children with autism and Asperger's disorder. Journal of Paediatric Child Health, 34, 528-533.

- Pinto, D., Pagnamenta, A., Klei, L., Anney, R., Merico, D., Regan, R., e.a. (2010). Functional impact of global rare copy number variation in autism spectrum disorders. Nature, 466, 368-372.

- Polimeni, M.A., Richdale, A.L., & Francis, A.J. (2005). A survey of sleep problems in autism, Asperger's disorder and typically developing children. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49, 260-268.

- Posey, D.J., & McDougle, C.J. (2001). Pharmacotherapeutic management of autism. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 2, 587-600.

- Posey, D.J., Puntney, J.I., Sasher, T.M., Kem, D.L., & McDougle, C.J. (2004). Guanfacine treatment of hyperactivity and inattention in pervasive developmental disorders: a retrospective analysis of 80 cases. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 14, 233-242.

- Posey, D.J., Wiegand, R.E., Wilkerson, J., Maynard, M., Stigler, K.A., & McDougle, C.J. (2006). Open-label atomoxetine for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms associated with high-functioning pervasive develop- mental disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 16, 599-610.

- Posey, D.J., Aman, M.G., McCracken, J.T., Scahill, L., Tierney, E., Arnold, L.E.,e.a. (2007). Positive effects of methylphenidate on inattention and hyperactivity in pervasive developmental disorders: An analysis of secondary measures. Biological Psychiatry, 61, 538-544.

- Posey, D.J., Stigler, K.A., Erickson, C.A, & McDougle, C.J. (2008). Antipsychotics in the treatment of autism. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 118, 6-14.

- Realmuto, G.M., August, G.J., & Garfinkel, B.D. (1989). Clinical effect of buspirone in autistic children. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 9, 122-125.

- Read, S.G., & Rendall, M. (2007). An open-label study of risperidone in the improvement of quality of life and treatment of symptoms of violent and self-injurious behaviour in adults with intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 20, 256-264.

- Reichelt, K.L., Hole, K., Hamberfer, A, Saelid, G., Edminson, P.D., Braestrup, C.B., e.a. (1981). Biologically active peptide containing fractions in schizophrenia and childhood autism. Advances in Biochemical Psychopharmacology, 28, 627-643.

- Reisberg, B., Doody, R., Stoffler, A., Schmitt, F., Ferris, S., Möbius, H.J.; Memantine Study Group. (2003). Memantine in moderate-to-severe Alzheimer's disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 348, 1333-1341.

- Remington, G., Sloman, L., Konstantareas, M., Parker, K., & Gow, R. (2001). Clomipramine versus haloperidol in the treatment of autistic disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 21, 440-444.

- Rescorla, L. (1989). The Language Development Survey: A screening tool for delayed language in toddlers. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 54, 587-599.

- Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology (RUPP) Autism Network (2005). Randomized, controlled, crossover trial of methylphenidate in pervasive developmental disorders with hyperactivity. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 1266-1274.

- Richdale, A.L., Francis, A., Gavidia-Payne, S.G., & Cotton, S. (1999). Stress, behaviour and sleep problems in children with an intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 25, 147-161.

- Richdale, A.L., & Schreck, K.A. (2009). Sleep problems in autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, nature, and possible biopsychosocial aetiologies. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 13, 403-411.

- Ritvo, E.R., Ritvo, R., Yuwiller, A., Brothers, A., Freeman, B.J. & Plotkin, S. (1993). Elevated daytime melatonin concentrations in autism: a pilot study. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2, 75-78.

- Rossignol, D.A., & Frye, R.E. (2011). Melatonin in autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 53, 783-792.

- Rossignol, D.A., & Rossignol, L.W. (2006). Hyperbaric oxygen therapy may improve symptoms in autistic children. Medical Hypotheses, 67, 216-228.

- Rossignol, D.A., Rossignol, L.W., James, S.J., Melnyk, S. & Mumper, E. (2007). The effects of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on oxidative stress, inflammation, and symptoms in children with autism: an open-label pilot study. BMC Pediatrics, 7, 36.

- Rossignol, D.A., Rossignol, L.W., Smith, S., Schneider, C., Logerquist, S., Usman, A. e.a. (2009). Hyperbaric treatment for children with autism: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. BMC Pediatrics, 9, 21.

- Ruedrich, S., Swales, T.P., Fossaceca, C., Toliver, J., & Rutkowski, A. (1999). Effect of divalproex sodium on aggression and self-injurious behaviour in adults with intellectual disability: A retrospective review. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 43, 105-111.

- Rumsey, J.M., Rapoport, J.L., & Sceery, W.R. (1985). Autistic children as adults: psychiatric, social, and behavioural outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 24, 465-473.

- Rutter, M.L. (2011). Progress in understanding autism: 2007-2010. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 395-404.

- Sack, R.L., Hughes, R.J., Edgar, D.M., & Lewy, A.J. (1997). Sleep promoting effects of melatonin: at what doses, in whom, under what conditions and by what mechanisms. Sleep, 20, 192-197.

- Saebra, M.L.V., Bignotto, M., Pinto, L., Tufik, S. (2000). Randomized double-blind clinical trial, controlled with placebo, of the toxicology of chronic melatonin treatment. Journal of Pineal Research, 29, 193-200.

- Saxena, PR. (1995). Serotonin receptors: subtypes, functional responses and therapeutic relevance. Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 66, 339-368.

- Scahill, L., McDougle, C.J., Williams, S.K., Dimitropoulos, A., Aman, M.G., McCracken, J.T., e.a. (2006). Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale modified for pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45, 1114-1123.

- Schneider, L.S., Dagerman, K.S., Higgins, J.P, & McShane, R. (2011). Lack of evidence for the efficacy of memantine in mild Alzheimer disease. Archives of Neurology, 68, 991-998.

- Schopler, E., Reichler, R.J., DeVellis, R.F., & Daly, K. (1980). Toward objective classification of childhood autism: Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 10, 91-103.

- Schothorst, P.F., Engeland, H. van, Gaag, R.J. van der, Minderaa, R.B., Stockmann, A.P.A.M. , Westermann, G.M.A., & Floor-Siebelink, H.A. (2009). Richtlijn diagnostiek en behandeling autismespectrumstoornissen bij kinderen en jeugdigen. Utrecht: De Tijdstroom.

- Shuang, M., Liu, J., Jia, M.X., Yang, J.Z., Wu, S.P, Gong, X.H., e.a. (2004). Family-based association study between autism and glutamate receptor 6 gene in Chinese Han trios. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 131B, 48-50.

- Siegel, B.V. Jr., Nuechterlein, K.H., Abel, L., Wu, J.C., & Buchsbaum, M.S.(1995). Glucose metabolic correlates of continuous test performance in adults with a history of infantile autism, schizophrenics, and controls. Schizophrenia Research, 17, 85-94.

- Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Charman, T., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., & Baird, G. (2008). Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 921-929.

- Singh, I., & Owino, J. E. (1992). A double-blind comparison of zuclopenithixol tablets with placebo in the treatment of mentally handicapped in-patients with associated behavioural disorders. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 36, 541-549.

- So, E.L. (2010). Interictal epileptiform discharges in persons without a history of seizures: what do they mean? Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology, 27, 229-38.

- Somponpun, S., & Sladek, C.D. (2002). Role of estrogen receptor-beta in regulation of vasopressin and oxytocin release in vitro. Endocrinology, 143, 2899-904.

- Sorgi, P., Ratey, J., Knoedler, D.W., Markert, R.J., Reichman, M. (1991). Rating aggression in the clinical setting, a retrospective adaptation of the overt aggression scale: preliminary results. Journal of Neuropsychiatry, 3, 52-56.

- Spreat, S., & Conroy, J. (1998). Use of psychotropic medications for persons with mental retardation who live in Oklahoma nursing homes. Psychiatric Services, 49, 510-512.

- Stahl, S.M. (2000). The new cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease, part 2: Illustrating their mechanisms of action. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61, 813-814.

- Steele, J., Matos, L.A., Lopez, E.A., Perez-Pinzon, M.A., Prado, R., Busto, R., e.a. (2004). A phase 1 safety study of hyperbaric oxygen therapy for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, 5, 250-254.

- Sterling, L., Dawson, G., Estes, A., & Greenson, J. (2008). Characteristics associated with presence of depressive symptoms in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1011-1018.

- Sterman, M.B., & Friar, L. (1972). Suppression of seizures in an epileptic following sensorimotor EEG feedback training. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 33, 89-95.

- Stewart, M.E., Barnard, L., Pearson, J., Hasan, R., & O'Brien, G. (2006). Presentation of depression in autism and Asperger syndrome: A review. Autism, 10, 103-116.

- Stigler, K.A., & McDougle, C.J. (2008). Pharmacotherapy of irritability in pervasive developmental disorders. Child and adolescent psychiatric clinics of North America, 17, 739-52, vii-viii.

- Stoller, K.P. (2005). Quantification of neurocognitive changes before, during, and after hyperbaric oxygen therapy in a case of fetal alcohol syndrome. Pediat- rics, 116, 586-91.

- Stuss, D., & Knight, R. (2002). Principles of frontal lobe function. Oxford University Press.

- Suarez, G.A., Opfer-Gehrking, T.L., Offord, K.P., Atkinson, E.J., O'Brien, P.C., & Low, P.A. (1999). The Autonomic Symptom Profile: A new instrument to assess autonomic symptoms. Neurology, 52, 523-528.

- Sullivan, P.F., Neale, M.C., & Kendler, K.S. (2000). Genetic epidemiology of major depression: Review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 1552-1562.

- Tani, P., Lindberg, N., Nieminen-von Wendt, T., Wendt, L. von, Alanko, L, Appelberg, B. e.a. (2003). Insomnia is a frequent finding in adults with Asperger syndrome. BMC Psychiatry, 3, 12.

- Tantam, D. (2000). Psychological disorder in adolescents and adults with Asperger syndrome. Autism, 4, 47-62.

- Theoharides, T.C., Kempuraj, D., & Redwood, L. (2009). Autism: an emerging 'neuroimmune disorder' in search of therapy. Expert Opin Pharmacother, 10, 2127-2143.

- Thirumalai, S.S., Shubin, R.A., & Robinson, R. (2002). Rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder in children with autism. Journal of Child Neurology, 17, 173-178.

- Toma, C., Rossi, M., Sousa, I., Blasi, F., Bacchelli, E., Alen, R. e.a. (2007). Is ASMT a susceptibility gene for autism spectrum disorders? A replication study in European populations. Molecular Psychiatry, 12, 977-979.

- Tordjman, S., Anderson, G.M., Pichard, N., Charbuy, H., & Touitou, Y. (2005). Nocturnal excretion of 6-sulphatoxymelatonin in children and adolescents with autistic disorder. Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 57, 134-138.

- Tsakanikos, E., Sturmey, P, Costello, H., Holt, G., & Bouras, N. (2007). Referral trends in mental health services for adults with intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 11, 9-17.

- Tulassay, Z., Bodnar, A., Farkas, I., Papp, J. & Gupta, R. (1992). Somatostatin versus secretin in the treatment of actively bleeding gastric erosions. Digestion, 51, 211-216.

- Tyrer, P., Oliver-Africano, PC., Ahmed, Z., Bouras, N., Cooray, S., Deb, S. e.a. (2008). Risperidone, haloperidol, and placebo in the treatment of aggressive challenging behaviour in patients with intellectual disability: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 371, 57-63.

- Versteeg, D.H.G. (1980). Interaction of peptides related to ACTH, MSH and p-LPH with neurotransmitters in the brain. Pharmacology and Therapeu- tics, 11, 535-557.

- Vickerstaff, S., Heriot, S., Wong, M., Lopes, A., & Dossetor, D. (2007). Intellectual ability, self-perceived social competence, and depressive symptomatology in children with high-functioning autistic spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 1647-1664.

- Volkow, N.D., Wang, G.J., Fowler, J.S., Gatley, S.J., Logan, J., Ding, Y.S., e.a. (1998). Dopamine transporter occupancies in the human brain induced by therapeutic doses of oral methylphenidate. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155, 1325-1331.

- Walters, A.S. (1995). Toward a better definition of the restless legs syndrome. Movement Disorders, 10, 634-642.

- Watanabe, Y., Tsumura, H., & Sasaki, H. (1991). Effect of continuous intravenous infusion of secretin preparation (secrepan). in patients with hemorrhage from chronic peptic ulcer and acute gastric mucosal lesion (AGML). Gastroenterology Japan, 26, 86-89.

- Wheeler, B., Taylor, B., Simonsen, K., & Reith, D.M. (2005). Melatonin treatment in Smith-Magenis syndrome. Sleep, 28, 1609-1610.

- White, J.F. (2003). Intestinal psychopathology in autism. Experimental Biology and Medicine, 228, 639-649.

- Wied, D. de, Diamant, M., & Fodor, M. (1993). Central nervous system effects of the neurohypophyseal hormones and related peptides. Frontiers in Neuro-endocrinology, 14, 251-302.

- Wilder, R.M. (1921). The effects of ketonemia on the course of epilepsy. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 2, 307-308.

- Williams, K., Wheeler, D.M., Silove, N., & Hazell, P. (2010). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2010(8), Article CD004677. Retrieved September 15, 2011. The Cochrane Library Database.

- Wink, L.K., Plawecki, M.H., Erickson, C.A., Stigler, K.A., & McDougle, C.J. (2010). Emerging drugs for the treatment of symptoms associated with autism spectrum disorders. Expert opinion on emerging drugs, 15, 481-494.

- Yoo, J.H., Valdovinos, M.G., & Williams, D.C. (2007). Relevance of donepezil in enhancing learning and memory in special populations: a review of the literature. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 1883-1901.

- Yudofsky, S. C., Silver, J. M., Jackson,W., Endicott, J., & Williams, D. (1986). The overt aggression scale for the objective rating of verbal and physical aggression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 143, 35-39.

- Zhdanova, I.V., Wurtman, R.J., & Wagstaff, J. (1999). Effects of a low dose of melatonin on sleep in children with Angelman syndrome. Journal of Pediatrie Endocrinology and Metabolism, 12, 57-67.

- Zimmerman, I.L., Steiner, V.G., & Pond, R.E. (1992). PLS-3: Preschool Language Scale-3. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

Evidence tabellen

Tabel 5.28 ORG 2766 voor gedragsmanagement bij kinderen met een ASS

|

Study |

Buitelaar e.a., 1992 |

Buitelaar e.a., 1996 |

|

No. trials (Total participants) |

2 (68) |

|

|

N/% female |

4/19 |

15/32 |

|

Mean age |

10 |

10-11 |

|

IQ |

Range and mean not reported |

Range not reported (means 77 |

|

|

(19% in IQ range 22-40; 19% in IQ range 40-55; 15% in IQ range |

& 80) |

|

|

55-70; and 48% in IQ range 70-85) |

|

|

Axis I/II disorders |

100% autism (autistic disorder) |

100% autism (autistic disorder) |

|

Dose |

40mg/day |

40mg/day |

|

Comparator |

Placebo |

Placebo |

|

Length of treatment |

8 weeks per intervention |

6 weeks |

|

Length of follow-up |

36 weeks |

6 weeks |

Overzicht onderzoekskenmerken van geïncludeerde placebogecontroleerde onderzoeken naar ORG 2766 voor gedragsmanagement bij kinderen met een ASS.

Tabel 5.30 ORG 2766 versus placebo bij kinderen met een ASS

|

Outcome |

Challenging behaviour (social withdrawal) |

Challenging behaviour (social isolation) |

Symptom severity/ improvement |

|

Study |

Buitelaar e.a., 1996 |

Buitelaar e.a., 1992 |

Buitelaar e.a., 1992; 1996 |

|

Effect size |

RR = 1,55 (0,57, 4,22) |

SMD = -0,92 (-1,82, -0,02) |

SMD = -0,97 (-1,48, -0,45) |

|

Quality of evidence Very low1,2,3,4 (GRADE) |

Very low2,3,4 |

Low1,3 |

|

|

Number of studies/ (K = 1; N = 47) participants |

(K = 1; N = 21) |

(K = 2; N = 68) |

|

|

Forest plot |

Biomedical |

Biomedical |

Biomedical |

Overzicht bewijsprofiel ORG 2766 versus placebo bij kinderen met een ASS.

1 Downgraded for risk of bias as randomisation methods were unclear in Buitelaar e.a., 1996 (authors state ‘randomised in principle’) and there was a trend for group differences in age and CARS score at baseline

2 Downgraded for inconsistency as Buitelaar e.a. 1992 found statistically significant treat- ment effects for challenging behaviour as measured by social isolation on the GAP, whereas Buitelaar e.a. 1996 found no significant differences for social withdrawal as measured by ABC

3 Downgraded for indirectness as extrapolating from children with autism

4 Downgraded for imprecision as the sample size is small

ABC: Autism Behavior Checklist; CARS: Childhood Autism Rating Scale; GAP: General Assessment Parents Scale; GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; SMD: standardised mean difference.

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 01-02-2013

Uiterlijk in 2019 bepaalt de Landelijk Samenwerkingsverband Kwaliteit Standaarden (LSPS) in samenspraak met de betrokken partijen of deze richtlijn nog actueel is. Zo nodig wordt een nieuwe werkgroep geïnstalleerd om de richtlijn te herzien. De geldigheid van de richtlijn komt eerder te vervallen wanneer nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding geven een vervroegd herzieningstraject te starten.

Algemene gegevens

Deze richtlijn is een initiatief van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie en het Nederlands Instituut van Psychologen (NIP). De ontwikkeling werd gefinancierd vanuit het gealloceerde budget van de NVvP van de stichting Kwaliteitsgelden medisch specialisten (SKMS) en is methodologisch en organisatorisch ondersteund door het Trimbos-instituut.

Doel en doelgroep

Doel

Deze richtlijn is ontwikkeld als hulpmiddel. De richtlijn geeft aanbevelingen en handelingsinstructies voor de herkenning, diagnostiek en behandeling (behandeling in engere zin, dus uitsluitend behandeling, niet begeleiding) van volwassenen met autismespectrumstoornissen. De richtlijn geeft aanbevelingen ter ondersteuning van de praktijkvoering van alle professionals die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor volwassenen met een autismespectrumstoornis (ASS). Op basis van de resultaten van wetenschappelijk onderzoek en overige overwegingen geeft de richtlijn een overzicht van goed (‘optimaal') handelen als waarborg voor kwalitatief hoogwaardige zorg. De richtlijn kan tevens richting geven aan de onderzoeksagenda voor wetenschappelijk onderzoek naar autismespectrumstoornissen.

Deze richtlijn heeft tot doel een leidraad te geven voor diagnostiek en behandeling van volwassenen met een ASS. Er is een multidisciplinaire ontwikkelprocedure gehanteerd om te zorgen voor een positief effect op de multidisciplinaire samenwerking in de dagelijkse praktijk. Daarnaast moet de richtlijn gezien worden als een moederrichtlijn: een vertaling kan plaatsvinden naar monodisciplinaire richtlijnen van afzonderlijke beroepsgroepen, waarin die beroepsgroepen aanknopingspunten kunnen vinden voor lokale zorgprogramma's en protocollen. Het opstellen van lokale zorgprogramma's en protocollen op basis van deze richtlijn moedigt de werkgroep aan, omdat dat bevorderlijk is voor de implementatie van de in de richtlijn beschreven optimale zorg.

Het kan zijn dat de aanbevelingen uit deze richtlijn in de concrete situatie niet aansluiten bij de wensen of behoeften van de persoon met een ASS. In dat geval moet het in principe mogelijk zijn beredeneerd af te wijken van de richtlijn, tenzij de wensen of behoeften van de persoon met een ass naar de mening van de behandelaar hem of haar kunnen schaden, dan wel geen nut hebben.

Doelgroep

De primaire doelgroep van deze richtlijn bestaat uit volwassenen en adolescenten vanaf 18 jaar waarbij sprake is van (een vermoeden van) een ASS. In de afbakening van de werkgroep valt ook de groep ouderen binnen de groep volwassenen. De groep ouderen wordt gedefinieerd als de groep mensen die 55 jaar of ouder zijn. Hierbij is gekeken naar de volgende autismespectrumstoornissen: autistische stoornis, stoornis van Asperger, en pervasieve ontwikkelingsstoornis niet anderszins omschreven.

Samenstelling werkgroep

De ‘richtlijnwerkgroep Autismespectrumstoornissen bij volwassenen’, onder voorzitterschap van dr. Cees C. Kan en vice-voorzitterschap van prof.dr. Hilde M. Geurts, bestond uit psychiaters, psychologen, verpleegkundigen’ belangenbehartigers’ en ervaringsdeskundigen die door de beroepsverenigingen werden uitgenodigd en zich op persoonlijke titel aan het project verbonden. De richtlijnwerkgroep bestond uit een kerngroep, een klankbordgroep en een adviseur. De richtlijnwerkgroep werd methodologisch en organisatorisch ondersteund door het technische team van het Trimbos-instituut.

Leden kerngroep

|

|

Naam |

Organisatie |

Functie |

|

1. |

Cornelis C. Kan, voorzitter |

Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen en CASS 18+ |

Psychiater |

|

2. |

Hilde M. Geurts, vice voorzitter |

Universiteit van Amsterdam en Dr. Leo Kannerhuis |

Psycholoog |

|

3. |

Bram B. Sizoo |

Dimence, Overijssel |

Psychiater |

|

4. |

Wim J.C. Verbeeck |

Vincent van Gogh Instituut, Centrum voor Autisme en ADHD, Venray |

Psychiater |

|

5. |

Caroline H. Schuurman |

Centrum autisme Rivierduinen, Leiden. |

Psycholoog |

|

6. |

Etienne J.M. Forceville |

Centrum Autisme, G GZ-Noord-Holland- Noord |

Psycholoog |

|

7. |

Dietske Vrijmoed |

GGz Delfland |

Verpleegkundige |

|

8. |

Evelien Veldboom |

GGNet |

Verpleegkundige |

|

9. |

Fred Stekelenburg |

Nederlandse Vereniging voor Autisme (NVA) |

Directeur NVA |

|

10. |

Jannie van Manen |

Nederlandse Vereniging voor Autisme (NVA) |