Ritmecontrole

Uitgangsvraag

Hoe kunnen we ritme bij patiënten met atriumfibrilleren reguleren?

Deze uitgangsvraag bevat de volgende deelvragen:

- Wat zijn de indicaties voor ritmecontrole?

- Hoe kan sinusritme worden hersteld? Welke therapieën zijn er om sinusritme te bereiken en te behouden?

- Wanneer dient elektrische cardioversie en wanneer dient farmacologische cardioversie te worden overwogen?

Aanbeveling

Reguleer het ritme voor de verbetering van klachten en kwaliteit van leven bij patiënten met atriumfibrilleren.

Kies voor ritmecontrole bij patiënten met aanhoudende AF-gerelateerde klachten (inclusief hartfalen) in aanvulling op preventie van CVA, rate-controlebehandeling en behandeling van cardiovasculaire risicofactoren.

Indien cardioversie gewenst is:

- Geef iv vernakalant of iv flecainide bij recent ontstaan AF (< 48u):

-

- Vernakalant kan niet gegeven worden bij recent ACS of matig-ernstig hartfalen.

- Flecainide niet bij ischemisch of structureel hartlijden.

- Geef iv amiodaron voor cardioversie bij recent atriumfibrilleren (< 48h) en hartfalen of structureel hartlijden, hoewel conversie lang kan duren.

- Gebruik bij mensen met symptomatisch persistent atriumfibrilleren farmacologische cardioversie (huidige episode < 48h) of elektrische cardioversie voor ritmecontrole.

- Gebruik farmacologische cardioversie alleen bij hemodynamisch stabiele patiënten.

- Overweeg voorbehandeling met amiodaron, flecainide, propafenon of ibutilide om de kans op succesvolle cardioversie groter te maken.

- Overweeg AF-patiënten met weinig frequente aanvallen en een structureel normaal hart, orale flecainide of propafenon voor te schrijven voor eenmalig gebruik bij een atriumfibrilleren-episode, indien aangetoond is dat dit veilig kan en effectief is.

Overwegingen

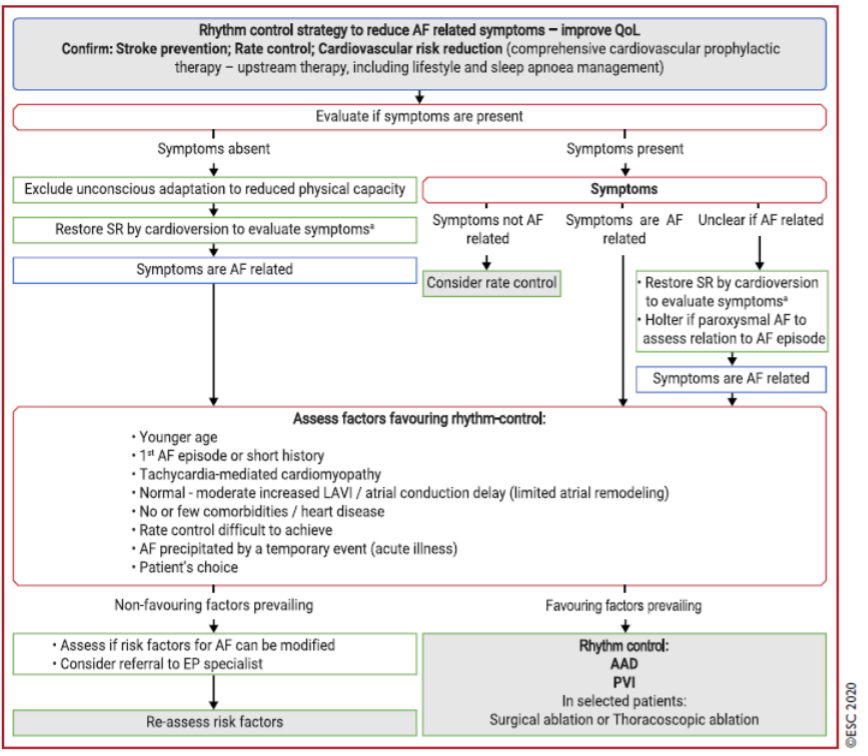

The ‘rhythm control strategy’ refers to attempts to restore and maintain sinus rhythm, and may engage a combination of treatment approaches, including cardioversion (Ecker, 2018; Gilbert, 2015), antiarrhythmic medication (Singh, 2005; Shiga, 2017; Capucci, 2016), and catheter ablation (Shi, 2015; Siontis, 2016; Kim, 2016), along with an adequate rate control, anticoagulation therapy (see module 6.6) and comprehensive cardiovascular prophylactic therapy (upstream therapy, including lifestyle and sleep apnoea management) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Rhythm control strategy

AAD = antiarrhythmic drug; AF = atrial fibrillation; CMP = cardiomyopathy; CV = cardioversion; LAVI = left atrial volume index; PAF = paroxysmal atrial fibrillation; PVI = pulmonary vein isolation; QoL = quality of life; SR = sinus rhythm. aConsider cardioversion to confirm that the absence of symptoms is not due to unconscious adaptation to reduced physical and/or mental capacity.

Adapted from Hindricks (2020)

Indications for rhythm control

Based on the currently available evidence from RCTs, the primary indication for rhythm control is to reduce AF-related symptoms and improve QoL (Figure 1). In case of uncertainty, an attempt to restore sinus rhythm in order to evaluate the response to therapy may be a rational first step. Factors that may favour an attempt at rhythm control should be considered (Bayes de Luna, 2012; Jadidi, 2018) (Figure 1).

As AF progression is associated with a decrease in QoL (Dudink, 2018) and, with time, becomes irreversible or less amenable to treatment (De Vos, 2010), rhythm control may be a relevant choice, although currently there is no substantial evidence that this may result in a different outcome. Reportedly, rates of AF progression were significantly lower with rhythm control than rate control (Zhang, 2013). Older age, persistent AF, and previous stroke/TIA independently predicted AF progression (Zhang, 2013), which may be considered when deciding the treatment strategy. For many patients, an early intervention to prevent AF progression may be worth considering (Bunch, 2013), including optimal risk-factor management (rienstra, 2018). Ongoing trials in patients with newly diagnosed symptomatic AF will assess whether early rhythm control interventions such as AF catheter ablation offer an opportunity to halt the progressive patho-anatomical changes associated with AF (Andrade, 2018). However, there is evidence that, at least in some patients, a successful rhythm control strategy with AF catheter ablation may not affect atrial substrate development (The, 2012). Important evidence regarding the effect of early rhythm control therapy on clinical outcomes are expected in 2020 from the ongoing EAST (Early treatment of Atrial fibrillation for Stoke prevention Trial) trial (Aliot, 2015).

General recommendations regarding active informed patient involvement in shared decision making (module 4) also apply for rhythm control strategies. The same principles should be applied in female and male AF patients when considering rhythm control therapy (Michelena, 2010).

Cardioversion

Immediate cardioversion/elective cardioversion

Acute rhythm control can be performed as an emergency cardioversion in a haemodynamically unstable AF patient or in a non-emergency situation. Synchronized direct current electrical cardioversion is the preferred choice in haemodynamically compromised AF patients as it is more effective than pharmacological cardioversion and results in immediate restoration of sinus rhythm (Kirchhof, 2005; Kirchhof, 2002). In stable patients, either pharmacological cardioversion or electrical cardioversion can be attempted; pharmacological cardioversion is less effective but does not require sedation. Of note, pre-treatment with AADs can improve the efficacy of elective electrical cardioversion (Um, 2019). A RCT showed maximum fixed-energy electrical cardioversion was more effective than an energy-escalation strategy (Schmidt, 2020).

In a RCT, a wait-and-watch approach with rate control medication only and cardioversion when needed within 48 h of symptom onset was as safe as and non-inferior to immediate cardioversion of paroxysmal AF, which often resolves spontaneously within 24 h (Pluymaekers, 2019).

Elective cardioversion refers to the situation when cardioversion can be planned beyond the nearest hours. Observational data (Pokorney, 2017) showed that cardioversion did not result in improved AF-related QoL or halted AF progression, but many of these patients did not receive adjunctive rhythm control therapies (Pokorney, 2017). Other studies reported significant QoL improvement in patients who maintain sinus rhythm after electrical cardioversion and the only variable independently associated with a moderate to large effect size was sinus rhythm at 3 months (Sandhu, 2017).

Factors associated with an increased risk for AF recurrence after elective cardioversion include older age, female sex, previous cardioversion, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), renal impairment, structural heart disease, larger LA volume index, and HF (Ecker, 2018; Baranchuk, 2018; Toufan, 2017). Treatment of potentially modifiable conditions should be considered before cardioversion to facilitate maintenance of sinus rhythm (Figure 1) (Rienstra, 2018). In case of AF recurrence after cardioversion in patients with persistent AF, an early re-cardioversion may prolong subsequent duration of sinus rhythm (Voskoboinik, 2019).

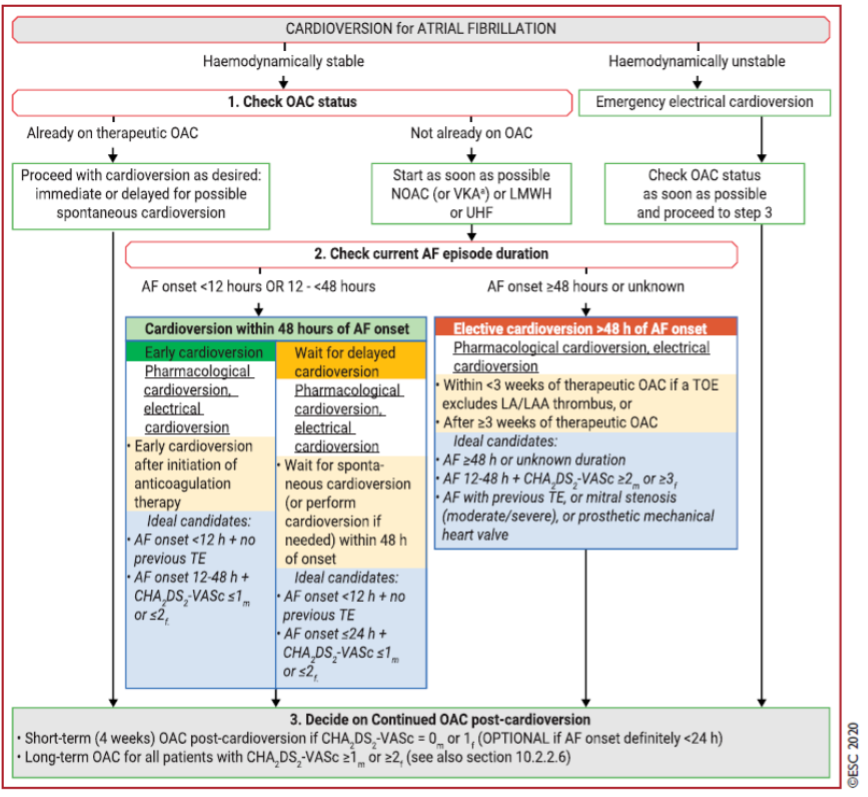

Non-emergency cardioversion is contraindicated in the presence of known LA thrombus. Peri-procedural thrombo-embolic risk should be evaluated and peri-procedural and long-term OAC use considered irrespective of cardioversion mode (i.e., pharmacological cardioversion or electrical cardioversion) (module 6.6). A flowchart for decision making on cardioversion is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Flowchart for decision making on cardioversion of AF depending on clinical presentation, AF onset, oral anticoagulation intake, and risk factors for stroke

AF = atrial fibrillation; CHA2DS2-VASc = Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age ≥ 75 years, Diabetes mellitus, Stroke, Vascular disease, Age 65 to 74 years, Sex category (female); cardioversion = cardioversion; ECV = electrical cardioversion; h = hour; LA = left atrium; LAA = left atrial appendage; LMWH = low-molecular-weight heparin; NOAC = non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant (referred to as DOAC in this guideline); OAC = oral anticoagulant; TE = thromboembolism; TOE = transoesophageal echocardiography; UFH = unfractionated heparin; VKA = vitamin K antagonist.

Adapted from Hindricks (2020)

Electrical cardioversion

Electrical cardioversion can be performed safely in sedated patients treated with i.v. midazolam and/or propofol or etomidate (Furniss, 2015). BP monitoring and oximetry during the procedure should be used routinely. Skin burns may occasionally be observed. Intravenous atropine or isoproterenol, or temporary transcutaneous pacing, should be available in case of post-cardioversion bradycardia. Biphasic defibrillators are standard because of their superior efficacy compared with monophasic defibrillators (Mittal, 2000; Inacio, 2016). Anterior-posterior electrode positions restore sinus rhythm more effectively (Kirchhof, 2005; Kirchhof, 2002), while other reports suggest that specific electrical pad positioning is not critically important for successful cardioversion (Kirkland, 2014).

Pharmacological cardioversion (including ‘pill in the pocket’)

Pharmacological cardioversion to sinus rhythm is an elective procedure indicated in haemodynamically stable patients. Its true efficacy is biased by the spontaneous restoration of sinus rhythm within 48 h of hospitalization in 76-83% of patients with recent onset AF (10 to 18% within first 3 h, 55 to 66% within 24 h, and 69% within 48 h) (Boriani, 2004; Danias, 1998; Dan, 2018). Therefore, a ‘wait-and-watch’ strategy (usually for < 24 h) may be considered in patients with recent-onset AF as a non-inferior alternative to early cardioversion (Pluymaekers, 2019).

The choice of a specific drug is based on the type and severity of associated heart disease (See Farmacotherapeutisch kompas) and pharmacological cardioversion is more effective in recent onset AF. Flecainide (and other class Ic agents), indicated in patients without significant LV hypertrophy (LVH), LV systolic dysfunction, or ischaemic heart disease, results in prompt (3 to 5 h) and safe (Markey, 2018) restoration of sinus rhythm in > 50% of patients (Chevalier, 2003; Capucci, 1992; Donovan, 1992; Reisinger, 2004; Khan, 2003), while i.v. amiodarone, mainly indicated in HF patients, has a limited and delayed effect but can slow heart rate within 12 h (Chevalier, 2003; Galve, 1996; Vardas, 2000; Letelier, 2003). Intravenous vernakalant is the most rapidly cardioverting drug, including patients with mild HF and ischaemic heart disease, and is more effective than amiodarone (Bash, 2012; Camm, 2011; Akel, 2018; Beatch, 2016; Roy; 2008; Kowey, 2009) or flecainide (Pohjantahti-Maaroos, 2019). Dofetilide is not used in Europe and is rarely used outside Europe. Ibutilide is effective to convert atrial flutter (AFL) to sinus rhythm (Vos, 1998).

In selected outpatients with rare paroxysmal AF episodes, a self-administered oral dose of flecainide or propafenone is slightly less effective than in-hospital pharmacological cardioversion but may be preferred (permitting an earlier conversion), provided that the drug safety and efficacy has previously been established in the hospital setting (Alboni, 2004). An atrioventricular node-blocking drug should be instituted in patients treated with class Ic AADs (especially flecainide) to avoid transformation to AFL with 1:1 conduction (Brembilla-Perrot, 2001).

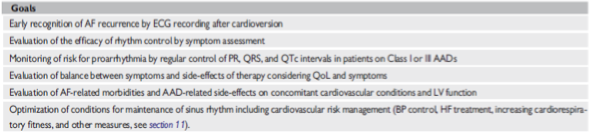

Follow-up after cardioversion

The goals of follow-up after cardioversion are shown in Table 1. When assessing the efficacy of a rhythm control strategy, it is important to balance symptoms and AAD side-effects. Patients should be reviewed after cardioversion to detect whether an alternative rhythm control strategy including AF catheter ablation, or a rate control approach is needed instead of current treatment.

Table 1 Goals of follow-up after cardioversion of AF

AAD = antiarrhythmic drug; AF = atrial fibrillation; BP = blood pressure; ECG = electrocardiogram; HF = heart failure; LV = left ventricular; PR = PR interval; QoL = quality of life; QRS = QRS interval; QTc = corrected QT interval. Adapted from Hindricks (2020)

Onderbouwing

Zoeken en selecteren

To answer the clinical question, the ESC-guideline for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation from 2020 (Hindricks, 2020) was used.

Referenties

- Akel T, Lafferty J. Efficacy and safety of intravenous vernakalant for the rapid conversion of recent-onset atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2018;23:e12508.

- Alboni P, Botto GL, Baldi N, Luzi M, Russo V, Gianfranchi L, Marchi P, Calzolari M, Solano A, Baroffio R, Gaggioli G. Outpatient treatment of recent-onset atrial fibrillation with the ‘pill-in-the-pocket’ approach. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2384-2391.

- Aliot E, Brandes A, Eckardt L, Elvan A, Gulizia M, Heidbuchel H, Kautzner J, Mont L, Morgan J, Ng A, Szumowski L, Themistoclakis S, Van Gelder IC, Willems S, Kirchhof P. The EAST study: redefining the role of rhythmcontrol therapy in atrial fibrillation: EAST, the Early treatment of Atrial fibrillation for Stroke prevention Trial. Eur Heart J 2015;36:255-256.

- Andrade JG, Champagne J, Deyell MW, Essebag V, Lauck S, Morillo C, Sapp J, Skanes A, Theoret-Patrick P, Wells GA, Verma A; EARLY-AF Study Investigators. A randomized clinical trial of early invasive intervention for atrial fibrillation (EARLY-AF) - methods and rationale. Am Heart J 2018;206:94-104.

- Baranchuk A, Yeung C. Advanced interatrial block predicts atrial fibrillation recurrence across different populations: learning Bayes syndrome. Int J Cardiol 2018;272:221-222.

- Bash LD, Buono JL, Davies GM, Martin A, Fahrbach K, Phatak H, Avetisyan R, Mwamburi M. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of cardioversion by vernakalant and comparators in patients with atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2012;26:167-179.

- Bayes de Luna A, Platonov P, Cosio FG, Cygankiewicz I, Pastore C, Baranowski R, Bayes-Genis A, Guindo J, Vinolas X, Garcia-Niebla J, Barbosa R, Stern S, Spodick D. Interatrial blocks. A separate entity from left atrial enlargement: a consensus report. J Electrocardiol 2012;45:445-451.

- Beatch GN, Mangal B. Safety and efficacy of vernakalant for the conversion of atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm; a phase 3b randomized controlled trial. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2016;16:113.

- Boriani G, Diemberger I, Biffi M, Martignani C, Branzi A. Pharmacological cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: current management and treatment options. Drugs 2004;64:2741-2762.

- Brembilla-Perrot B, Houriez P, Beurrier D, Claudon O, Terrier de la Chaise A, Louis P. Predictors of atrial flutter with 1:1 conduction in patients treated with class I antiarrhythmic drugs for atrial tachyarrhythmias. Int J Cardiol 2001;80:7-15.

- Bunch TJ, May HT, Bair TL, Johnson DL, Weiss JP, Crandall BG, Osborn JS, Anderson JL, Muhlestein JB, Lappe DL, Day JD. Increasing time between first diagnosis of atrial fibrillation and catheter ablation adversely affects long-term outcomes. Heart Rhythm 2013;10:1257-1262.

- Camm AJ, Capucci A, Hohnloser SH, Torp-Pedersen C, Van Gelder IC, Mangal B, Beatch G; AVRO Investigators. A randomized active-controlled study comparing the efficacy and safety of vernakalant to amiodarone in recent-onset atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:313-321.

- Capucci A, Piangerelli L, Ricciotti J, Gabrielli D, Guerra F. Flecainide-metoprolol combination reduces atrial fibrillation clinical recurrences and improves tolerability at 1-year follow-up in persistent symptomatic atrial fibrillation. Europace 2016;18:1698-1704.

- Capucci A, Lenzi T, Boriani G, Trisolino G, Binetti N, Cavazza M, Fontana G, Magnani B. Effectiveness of loading oral flecainide for converting recent-onset atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm in patients without organic heart disease or with only systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol 1992;70:69-72.

- Chevalier P, Durand-Dubief A, Burri H, Cucherat M, Kirkorian G, Touboul P. Amiodarone versus placebo and class Ic drugs for cardioversion of recentonset atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:255-262.

- Dan GA, Martinez-Rubio A, Agewall S, Boriani G, Borggrefe M, Gaita F, van Gelder I, Gorenek B, Kaski JC, Kjeldsen K, Lip GYH, Merkely B, Okumura K, Piccini JP, Potpara T, Poulsen BK, Saba M, Savelieva I, Tamargo JL, Wolpert C, ESC Scientific Document Group. Antiarrhythmic drugs-clinical use and clinical decision making: a consensus document from the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Working Group on Cardiovascular Pharmacology, endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Asia-Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS) and International Society of Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy (ISCP). Europace 2018;20:731-732.

- Danias PG, Caulfield TA, Weigner MJ, Silverman DI, Manning WJ. Likelihood of spontaneous conversion of atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;31:588-592.

- De Vos CB, Pisters R, Nieuwlaat R, Prins MH, Tieleman RG, Coelen RJ, van den Heijkant AC, Allessie MA, Crijns HJ. Progression from paroxysmal to persistent atrial fibrillation clinical correlates and prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:725-731

- Dudink E, Erkuner O, Berg J, Nieuwlaat R, de Vos CB, Weijs B, Capucci A, Camm AJ, Breithardt G, Le Heuzey JY, Luermans J, Crijns H. The influence of progression of atrial fibrillation on quality of life: a report from the Euro Heart Survey. Europace 2018;20:929-934.

- Ecker V, Knoery C, Rushworth G, Rudd I, Ortner A, Begley D, Leslie SJ. A review of factors associated with maintenance of sinus rhythm after elective electrical cardioversion for atrial fibrillation. Clin Cardiol 2018;41:862-870.

- Furniss SS, Sneyd JR. Safe sedation in modern cardiological practice. Heart 2015;101:1526-1530.

- Galve E, Rius T, Ballester R, Artaza MA, Arnau JM, Garcia-Dorado D, Soler-Soler J. Intravenous amiodarone in treatment of recent-onset atrial fibrillation: results of a randomized, controlled study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;27:1079-1082.

- Gilbert KA, Hogarth AJ, MacDonald W, Lewis NT, Tan LB, Tayebjee MH. Restoration of sinus rhythm results in early and late improvements in the functional reserve of the heart following direct current cardioversion of persistent AF: FRESH-AF. Int J Cardiol 2015;199:121-125.

- Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) (published online ahead of print, 2020 Aug 29). Eur Heart J. 2020;ehaa612. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612.

- Inacio JF, da Rosa Mdos S, Shah J, Rosario J, Vissoci JR, Manica AL, Rodrigues CG. Monophasic and biphasic shock for transthoracic conversion of atrial fibrillation: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Resuscitation 2016;100:66-75.

- Jadidi A, Muller-Edenborn B, Chen J, Keyl C, Weber R, Allgeier J, Moreno-Weidmann Z, Trenk D, Neumann FJ, Lehrmann H, Arentz T. The duration of the amplified sinus-p-wave identifies presence of left atrial low voltage substrate and predicts outcome after pulmonary vein isolation in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2018;4:531-543.

- Khan IA. Oral loading single dose flecainide for pharmacological cardioversion of recent-onset atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol 2003;87:121-128.

- Kim YG, Shim J, Choi JI, Kim YH. Radiofrequency catheter ablation improves the quality of life measured with a short form-36 questionnaire in atrial fibrillation patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0163755.

- Kirchhof P, Monnig G, Wasmer K, Heinecke A, Breithardt G, Eckardt L, Bocker D. A trial of self-adhesive patch electrodes and hand-held paddle electrodes for external cardioversion of atrial fibrillation (MOBIPAPA). Eur Heart J 2005;26:1292-1297.

- Kirchhof P, Eckardt L, Loh P, Weber K, Fischer RJ, Seidl KH, Bocker D, Breithardt G, Haverkamp W, Borggrefe M. Anterior-posterior versus anteriorlateral electrode positions for external cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: a randomised trial. Lancet 2002;360:1275-1279.

- Kirkland S, Stiell I, AlShawabkeh T, Campbell S, Dickinson G, Rowe BH. The efficacy of pad placement for electrical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation/flutter: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:717-726.

- Kowey PR, Dorian P, Mitchell LB, Pratt CM, Roy D, Schwartz PJ, Sadowski J, Sobczyk D, Bochenek A, Toft E; Atrial Arrhythmia Conversion Trial Investigators. Vernakalant hydrochloride for the rapid conversion of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2009;2:652-659.

- Letelier LM, Udol K, Ena J, Weaver B, Guyatt GH. Effectiveness of amiodarone for conversion of atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:777-785.

- Markey GC, Salter N, Ryan J. Intravenous flecainide for emergency department management of acute atrial fibrillation. J Emerg Med 2018;54:320-327.

- Michelena HI, Powell BD, Brady PA, Friedman PA, Ezekowitz MD. Gender in atrial fibrillation: ten years later. Gend Med 2010;7:206-217.

- Mittal S, Ayati S, Stein KM, Schwartzman D, Cavlovich D, Tchou PJ, Markowitz SM, Slotwiner DJ, Scheiner MA, Lerman BB. Transthoracic cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: comparison of rectilinear biphasic versus damped sine wave monophasic shocks. Circulation 2000;101:1282-1287.

- Pluymaekers N, Dudink E, Luermans J, Meeder JG, Lenderink T, Widdershoven J, Bucx JJJ, Rienstra M, Kamp O, Van Opstal JM, Alings M, Oomen A, Kirchhof CJ, Van Dijk VF, Ramanna H, Liem A, Dekker LR, Essers BAB, Tijssen JGP, Van Gelder IC, Crijns H; RACE ACWAS Investigators. Early or delayed cardioversion in recent-onset atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1499-1508.

- Pohjantahti-Maaroos H, Hyppola H, Lekkala M, Sinisalo E, Heikkola A, Hartikainen J. Intravenous vernakalant in comparison with intravenous flecainide in the cardioversion of recent-onset atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2019;8:114-120.

- Pokorney SD, Kim S, Thomas L, Fonarow GC, Kowey PR, Gersh BJ, Mahaffey KW, Peterson ED, Piccini JP; Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Cardioversion and subsequent quality of life and natural history of atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J 2017;185:59-66.

- Reisinger J, Gatterer E, Lang W, Vanicek T, Eisserer G, Bachleitner T, Niemeth C, Aicher F, Grander W, Heinze G, Kuhn P, Siostrzonek P. Flecainide versus ibutilide for immediate cardioversion of atrial fibrillation of recent onset. Eur Heart J 2004;25:1318-1324.

- Rienstra M, Hobbelt AH, Alings M, Tijssen JGP, Smit MD, Brugemann J, Geelhoed B, Tieleman RG, Hillege HL, Tukkie R, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Crijns H, Van Gelder IC; RACE Investigators. Targeted therapy of underlying conditions improves sinus rhythm maintenance in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation: results of the RACE 3 trial. Eur Heart J 2018;39:2987-2996.

- Roy D, Pratt CM, Torp-Pedersen C, Wyse DG, Toft E, Juul-Moller S, Nielsen T, Rasmussen SL, Stiell IG, Coutu B, Ip JH, Pritchett EL, Camm AJ; Atrial Arrhythmia Conversion Trial Investigators. Vernakalant hydrochloride for rapid conversion of atrial fibrillation: a phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Circulation 2008;117:1518-1525.

- Sandhu RK, Smigorowsky M, Lockwood E, Savu A, Kaul P, McAlister FA. Impact of electrical cardioversion on quality of life for the treatment of atrial fibrillation. Can J Cardiol 2017;33:450-455.

- Schmidt AS, Lauridsen KG, Torp P, Bach LF, Rickers H, Lofgren B. Maximumfixed energy shocks for cardioverting atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2020;41:626-631.

- Shi LZ, Heng R, Liu SM, Leng FY. Effect of catheter ablation versus antiarrhythmic drugs on atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Exp Ther Med 2015;10:816-822.

- Shiga T, Yoshioka K, Watanabe E, Omori H, Yagi M, Okumura Y, Matsumoto N, Kusano K, Oshiro C, Ikeda T, Takahashi N, Komatsu T, Suzuki A, Suzuki T, Sato Y, Yamashita T; AF-QOL study investigators. Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation recurrences and quality of life in symptomatic patients: a crossover study of flecainide and pilsicainide. J Arrhythm 2017;33:310-317.

- Singh BN, Singh SN, Reda DJ, Tang XC, Lopez B, Harris CL, Fletcher RD, Sharma SC, Atwood JE, Jacobson AK, Lewis HD, Jr., Raisch DW, Ezekowitz MD; Sotalol Amiodarone Atrial Fibrillation Efficacy Trial Investigators. Amiodarone versus sotalol for atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1861-1872.

- Siontis KC, Ioannidis JPA, Katritsis GD, Noseworthy PA, Packer DL, Hummel JD, Jais P, Krittayaphong R, Mont L, Morillo CA, Nielsen JC, Oral H, Pappone C, Santinelli V, Weerasooriya R, Wilber DJ, Gersh BJ, Josephson ME, Katritsis DG. Radiofrequency ablation versus antiarrhythmic drug therapy for atrial fibrillation: meta-analysis of quality of life, morbidity, and mortality. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2016;2:170-180.

- Teh AW, Kistler PM, Lee G, Medi C, Heck PM, Spence SJ, Morton JB, Sanders P, Kalman JM. Long-term effects of catheter ablation for lone atrial fibrillation: progressive atrial electroanatomic substrate remodeling despite successful ablation. Heart Rhythm 2012;9:473-480.

- Toufan M, Kazemi B, Molazadeh N. The significance of the left atrial volume index in prediction of atrial fibrillation recurrence after electrical cardioversion. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res 2017;9:54-59.

- Um KJ, McIntyre WF, Healey JS, Mendoza PA, Koziarz A, Amit G, Chu VA, Whitlock RP, Belley-Cote EP. Pre- and post-treatment with amiodarone for elective electrical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace 2019;21:856-863.

- Vardas PE, Kochiadakis GE, Igoumenidis NE, Tsatsakis AM, Simantirakis EN, Chlouverakis GI. Amiodarone as a first-choice drug for restoring sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomized, controlled study. Chest 2000;117:1538-1545.

- Vos MA, Golitsyn SR, Stangl K, Ruda MY, Van Wijk LV, Harry JD, Perry KT, Touboul P, Steinbeck G, Wellens HJ. Superiority of ibutilide (a new class III agent) over DL-sotalol in converting atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation. The Ibutilide/Sotalol Comparator Study Group. Heart 1998;79:568-575.

- Voskoboinik A, Kalman E, Plunkett G, Knott J, Moskovitch J, Sanders P, Kistler PM, Kalman JM. A comparison of early versus delayed elective electrical cardioversion for recurrent episodes of persistent atrial fibrillation: a multi-center study. Int J Cardiol 2019;284:33-37.

- Zhang YY, Qiu C, Davis PJ, Jhaveri M, Prystowsky EN, Kowey P, Weintraub WS. Predictors of progression of recently diagnosed atrial fibrillation in REgistry on Cardiac Rhythm DisORDers Assessing the Control of Atrial Fibrillation (RecordAF) United States cohort. Am J Cardiol 2013;112:79-84.

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 17-10-2022

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-09-2022

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2018 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met atriumfibrilleren.

Werkgroep

- Prof. dr. N.M.S. (Natasja) de Groot, cardioloog, werkzaam in het Erasmus Medisch Centrum te Rotterdam, NVVC (voorzitter)

- P.H. (Pepijn) van der Voort, cardioloog, werkzaam in het Catharina Ziekenhuis te Eindhoven, NVVC

- Dr. M.E.W. (Martin) Hemels, cardioloog, werkzaam in het Rijnstate Ziekenhuis te Arnhem en RaboudUMC te Nijmegen, NVVC

- Dr. T.J. (Thomas) van Brakel, thoraxchirurg, werkzaam in het Catharina Ziekenhuis te Eindhoven, NVTNET

- Dr. M. (Michiel) Coppens, internist-vasculair geneeskundige, werkzaam in de Amsterdam Universitair Medische Centra te Amsterdam, NIV

- Dr. S. (Sander) van Doorn, huisarts, werkzaam in het Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht te Utrecht, NHG

- Prof. dr. M.K. (Kamran) Ikram, neuroloog, werkzaam in het Erasmus Medisch Centrum te Rotterdam, NVN

- H. (Hans) van Laarhoven, zelfstandig adviseur, werkzaam bij Laerhof Advies, Harteraad

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. B.H. (Bernardine) Stegeman, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

De Groot (voorzitter) |

Cardioloog-elektrofysioloog, Erasmus Medisch Centrum, Rotterdam |

Mede-oprichter Stichting Atrial Fibrillation Innovation Platform |

Unrestricted grant voor AF bij Hartfalen, Pathofysiologische onderzoek (valt buiten de afbakening) |

Geen (valt buiten de afbakening) |

|

Brakel |

Cardio-thoracaal chirurg |

Verzorgen van trainingen voor chirurgische behandeling van AF (Trainingscontract met Medtronic; inkomsten voor de afdeling) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Coppens |

Internist-vasculaire geneeskunde |

* Wetenschappelijke adviesraad Trombosestichting Nederland (onbetaald). |

Betaald adviseurschap of betaalde lezingen/nascholingen voor Bayer, Daiichi Investigator initiated studies met externe financiële ondersteuning en door industrie geïnitieerde studies Bayer, UniQure, Roche CSL Behring and Daiichi Sankyo |

Geen (valt buiten de afbakening, niet over AF-patiënten; onderzoek ging bijvoorbeeld over DOAC bij short bowel patiënten) |

|

Van der Voort |

Cardioloog-electrofysioloog Catharinaziekenhuis Eindhoven |

Bestuurslid van NHRA, onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Laarhoven |

Zelfstandig adviseur voor de zorg |

Bestuurslid LAREB, vergoeding conform normering NTVZ Voorzitter Raad van Toezicht stichting Leefh, vergoeding conform NVTZ |

* Lid Patientenadviesraad Pfizer, vacatievergoeding * Adviesraad ‘NOAC’ (eenmalig 2019, vacatievergoeding) |

Geen |

|

Van Doorn |

* Assistant professor, Julius Centrum, UMC Utrecht |

Geen |

* Betrokken als co-PI van het ALL-IN onderzoek, naar de substitutie van AF zorg van de 2e lijn naar de huisarts, inclusief behandeling met anticoagulantia: doe 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa055 (afgerond) * co-PI betrokken bij het FRAIL-AF onderzoek, een gerandomiseerd onderzoek naar de veiligheid en effectiviteit van DOAC’s bij kwetsbare ouderen: trialregister.nl NTR6721, doi 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032488 (lopend) * Betrokken bij onderzoek met routine zorg data (CPRD) naar de veiligheid en effectiviteit van DOAC’s, en een systematische review naar DOAC doseringen. |

Geen |

|

Hemels |

* Cardioloog-elektrofysioloog Rijnstate ziekenhuis * Programmaleider NVVC Connect atriumfibrilleren |

* Associate editor van Netherlands Heart Journal, géén vergoeding * Onderwijsactiviteiten voor medisch specialisten, huisartsen, (ziekenhuis)apothekers en arts-assistenten/physician assisants, betreft urenvergoeding

|

* Principal investigator (samen met prof. M.V. Huisman) van het Dutch AF onderzoeks en registratieproject namens de NVVC en in opdracht van VWS/ZonMw. Er gaat een vergoeding naar de vakgroep cardiologie in het Rijnstate i.v.m. mijn werkzaamheden voor dit project, ook gefinancierd door FNT * Local principal investigator van diverse patiëntgebonden studies (hartritmestoornissen gerelateerd) in het Rijnstate ziekenhuis, géén persoonlijke vergoeding hiervoor |

Geen |

|

Ikram |

Hoogleraar Klinische Neuro-epidemiologie en neuroloog, Afdelingen Neurologie & Epidemiologie, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Stegeman |

Senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Meelezer |

||||

|

Jakulj |

* Internist-nefroloog Amsterdam UMC en Dianet * Lid richtlijnencommissie Nederlandse Federatie voor Nefrologie |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door een afgevaardigde patiëntenvereniging in de werkgroep. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan Harteraad en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module 1 Definitie en diagnose van atriumfibrilleren |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 2 Atriumfibrilleren, subtype, burden en progressie |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 3 Screenen voor atriumfibrilleren |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 4 Integrale behandeling voor patiënten met atriumfibrilleren |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 5.1 Antitrombotisch beleid ter preventie van herseninfarct |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 5.2 Afsluiting of verwijdering van het linker hartoor |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 6.1 Frequentiecontrole |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 6.2 Ritmecontrole |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 6.2.1 Ritmecontrole met antiaritmische medicatie |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 6.3 Katheterablatie |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 6.4 Chirurgie voor atriumfibrilleren en concomitante chirurgie voor atriumfibrilleren |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 6.5 Hybride katheter-/ chirurgische ablatie procedures |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 6.6 Peri-procedureel management ter preventie van herseninfarct |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 7 Cardiovasculaire risicofactoren en bijkomende ziekten |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.1 Atriumfibrilleren bij hemodynamische instabiliteit |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.2 Acute coronaire syndromen, chronisch coronairlijden, en percutane en chirurgische revascularisaties bij patiënten met atriumfibrilleren |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.3 Acuut herseninfarct of hersnebloeding bij patiënten met atriumfibrilleren |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.4 Bloeding ten tijde van antistolling |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.5 Atriumfibrilleren en valvulaire hartziekte |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.6 Atriumfibrilleren en chronische nierschade |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.7 De oudere en kwetsbare patiënt met atriumfibrilleren |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.8 Atriumfibrilleren en aangeboren hartafwijkingen |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.9 Atriumfibrilleren bij erfelijke hartspierziekten |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.10 Atriumfibrilleren tijdens de zwangerschap |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.11 Atriumfibrilleren in professionele sporters |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.12 Postoperatief atriumfibrilleren |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 9 Sekse-gerelateerde verschillen in atriumfibrilleren |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 10 Epidemiologie, implicaties en behandeling van subklinisch AF/AHRE |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

Implementatie

De werkgroep is vooral inhoudelijk bezig geweest met het aanpassen van de ESC-richtlijn ‘Diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation’ naar de Nederlandse praktijk. De werkgroep heeft een aantal suggesties gegeven voor het onder de aandacht brengen bij medische professionals van de nieuwe richtlijn. De verdere implementatie van de aanbevelingen uit de richtlijn valt buiten de expertise van de werkgroep.

Voorstel voor te ondernemen acties per partij

Hieronder wordt per partij toegelicht welke acties zij kunnen ondernemen om aandacht te geven aan de richtlijn.

Alle direct betrokken wetenschappelijk verenigingen/beroepsorganisaties

- Bekend maken van de richtlijn onder de leden.

- Publiciteit voor de richtlijn maken door over de richtlijn te publiceren in tijdschriften en te vertellen op congressen.

De lokale vakgroepen/individuele medisch professionals

- Het bespreken van de aanbevelingen in de vakgroepsvergadering en lokale werkgroepen.

- Het bespreken van de richtlijnen in de onderwijsuren van de medisch specialist in opleiding

- Het volgen van bijscholing die bij deze richtlijn ontwikkeld gaat worden.

- Afstemmen en afspraken maken met andere betrokken disciplines om de toepassing van de aanbevelingen in de praktijk te borgen.

Het Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten

Toevoegen van de richtlijn aan de Richtlijnendatabase.

Werkwijze

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met atriumfibrilleren. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door het Zorginstituut Nederland, Zelfstandige Klinieken Nederland, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie, Vereniging Innovatieve Geneesmiddelen, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Cardiologie, Federatie voor Nederlandse Trombosediensten, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Hart- en Vaatverpleegkundigen, Nederland Huisartsen Genootschap en Inspectie Gezondheidszorg en Jeugd via Invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbevelingen)

De Engelse tekst uit de ESC-richtlijn Diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation uit 2020 (Hindricks, 2020) is overgenomen, tenzij er argumenten voor de Nederlandse praktijk van belang zijn. De tekst is vervolgens aangepast en in het Nederlands opgesteld.

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. GRADE staat voor Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Vertalen van aanbevelingen

De European Society of Cardiology gebruikt een standaardformulering voor de aanbevelingen op basis van de klasse en niveau van het bewijs. Deze standaardformulering met vertaling naar het Nederlands staat in de onderstaande tabel weergegeven.

|

Class of recommendations |

Suggested wording to use |

Nl’se vertaling, gehanteerd door onder andere de CVRM-richtlijn |

|

I |

Is recommended/is indicated |

Sterke aanbeveling met een actieve, directieve formulering, zoals behandel, streef naar, et cetera |

|

II |

|

|

|

IIa |

Should be considered |

Zwakke aanbeveling met een actieve, directieve formulering, zoals overweeg |

|

IIb |

May be considerd |

Zwakke aanbeveling met als formulering: kan worden overwogen |

|

III |

Is not recommended |

Sterke aanbeveling met een actieve, directieve formulering, zoals behandel niet, et cetera |

CVRM, CardioVasculair RisicoManagement

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) (published online ahead of print, 2020 Aug 29). Eur Heart J. 2020;ehaa612. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html.

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.