MRI, echografie en röntgen in de diagnostiek

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van beeldvormende technieken als MRI, echografie en röntgen in het diagnostisch proces?

Aanbeveling

Verricht beeldvormend onderzoek, zoals conventionele röntgenfoto en/of MRI, alvorens een artroscopie te verrichten.

Verricht MRI bij patiënten jonger dan 50 jaar met knieklachten als aanvulling op anamnese en het lichamelijk onderzoek, tenzij er een hoge a priori kans is op intra-articulair letsel, dan is een artroscopie zonder MRI geïndiceerd (mits een conventionele kniefoto is gemaakt). Een hoge a priori kans is gedefinieerd als: anamnestisch een traumatisch moment, hydrops en een knie op slot.

Verricht bij patiënten ouder dan 50 jaar met knieklachten niet routinematig MRI, maar volsta in eerste instantie met een conventionele staande kniefoto met bij voorkeur een fixed flexion.

Wees terughoudend bij het toepassen van echografie in de indicatiestelling voor artroscopie vanwege onvoldoende zichtbaarheid van ossale en intra-articulaire structuren.

Overwegingen

Knee complaints are amongst injuries of the musculoskeletal system the second most frequent reason to visit the General Practitioner. Since the seventies, arthroscopy of the knee is used as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool in the management of acute, subacute and chronic knee injuries. Arthroscopy is an invasive procedure with associated risks and discomfort for the patient. For this reason, arthroscopy should ideally be reserved for therapeutic ends and the number of non-therapeutic arthroscopies should be restricted.

The last 25 years MRI of the knee has gained a role as an alternative to a diagnostic arthroscopy. Injuries of menisci and ligaments can be diagnosed with high sensitivity and specificity. In the last couple of years, the use of ultrasound in the diagnostic work-up of knee complaints is gaining popularity. Studies show diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound for meniscal injuries may be comparable to MRI. Considerations in the choice of additional diagnostic imaging are, amongst others, diagnostic accuracy, safety, availability and costs.

Diagnostic accuracy

It is difficult to formulate minimal requirements for an adequate MR examination of the knee. Both on low- and high-field strength systems (ranging from 0.2 to 3.0 T) examinations of satisfactory diagnostic quality can be performed if the scan protocol is adequate, if necessary targeting the specific diagnostic problem. A general scanning protocol, suitable for the assessment of menisci, ligaments and cartilage, should consist of scans in different planes: sagittal, coronal and where relevant, axial. In the choice of sequences at least a combination of short TE (T1 or PD-weighted images) and T2-weighted images with or without fat suppression should be used. The exact scanning protocol will furthermore be dependent upon institutional preferences and the available MR system.

Because there is a learning curve for the reading of MR images, experience and training of the reader will increase the accuracy of MRI (White, 1997). Experience of the reader has more influence on accuracy of MRI than field strength of the system (Krampla, 2009). Therefore, reading of the MRI by a (musculoskeletal) radiologist with adequate training and experience in reading MRI of the knee is essential to achieve highest accuracy.

A limited number of studies, compared to those for MRI, indicate that ultrasound of the knee can be accurate in the assessment of menisci and cruciate ligaments. Transducers used in aforementioned studies ranged from 5 to 14 MHz. No information is available about the influence of the frequency of transducers on accuracy, but higher frequencies yield higher resolution images, probably increasing accuracy. Cartilage can only be evaluated to a minor extent. Bone and bone marrow cannot be assessed with ultrasound. This seriously limits the diagnostic yield of ultrasonography when compared to MRI.

The learning curve for performing musculoskeletal ultrasound will be considerable, because not only interpreting the obtained images but also eye-hand coordination benefits greatly from training and experience. Therefore, ultrasonography will only be a reliable diagnostic tool in the hands of an experienced musculoskeletal ultrasonographer.

Safety

MRI of the knee is safe, if safety measures are adhered to. MRI is non-invasive and lacks ionizing radiation. Because of this lack of radiation, pregnancy (at every stage) is not a contra-indication for MRI. Contra-indications are (non-MRI compatible) pacemaker, metallic foreign bodies in the eye (absolute), claustrophobia (relative).

An examination of a pregnant woman in which the radiation of an x-ray does not come near the uterus, such as an image of the lungs or the knee, can take place without any danger to the pregnancy. In other words, in pregnant women a routine x-ray of the knee can be made safely and without risks at every stage of the pregnancy.

There are no known safety concerns with ultrasound.

Availability

In recent years, the availability of MR systems in the Netherlands has further increased. Every hospital has at least one MR system. There are several diagnostic centers that have access to MRI. A trend towards dedicated MR systems, especially for extremities, that can be installed against lower costs, has further increased the availability of MR systems. Because of the increased capacity, the waiting lists for MRI have substantially been reduced. Waiting periods will most of the time not exceed a couple of days to weeks.

The availability of ultrasound machines, especially with the recent development of handheld devices, is more widespread than MRI scanners. Waiting periods will most of the time not exceed a couple of days. Limitation will be the availability of adequately trained and experienced ultrasonographers.

When waiting periods for arthroscopy are long and waiting times for additional diagnostic imaging are short, diagnostic imaging can be used to decrease the number of arthroscopies and thus shorten waiting times for arthroscopy, which may lead to cost reduction.

Costs

Whether additional diagnostic imaging can be used in a cost-effective manner to reduce the number of (non-therapeutic) arthroscopies depends upon several factors. Foremost the prevalence of intra-articular pathology in the patient population in which to use additional diagnostic imaging is important. This determines the number of arthroscopies that can be prevented; if prevalence is high, the number of arthroscopies that can be prevented is low and from a cost-effective point of view a therapeutic arthroscopy is preferable. For instance, in male patients with a history of trauma and unequivocal physical examination (locked knee or extension deficit), the a priori probability of intra-articular pathology is so high that additional imaging will have no added value. If prevalence is low, diagnostic imaging won’t be cost effective neither. For instance, in case of clinically evident patellofemoral knee pain syndrome in young women without a history of trauma; the a priori probability of intra-articular knee pathology will be so low that imaging will have no added value. Even if the likelihood ratio of imaging is high, the post-test probability will remain low. Moreover, arthroscopy is not an option in these patients. The only reason to request MRI (not ultrasound, because cartilage and bone are insufficiently visualized) would be to exclude relevant pathology.

Each individual patient should be assessed whether additional diagnostic imaging is appropriate, considering factors that influence the prevalence of arthroscopically treatable pathology (age, sex, history of trauma and to a lesser extent physical examination).

When considering costs, the issue of who should order the additional diagnostic imaging must also be addressed. Usually a General Practitioner (GP) will refer a patient to the (orthopaedic) surgeon or sport physician, who will decide on diagnostic imaging, usually MRI, or perform a therapeutic arthroscopy. But when the GP, instead of referring the patient to secondary care, can access MRI directly, are the number of unnecessary referrals to secondary care reduced? A study in the United Kingdom (DAMASK study) showed that an MRI referral by the GP prior to a provisional orthopaedic appointment yielded significant benefits in patients’ knee-related quality of life when compared with direct referral to an orthopaedic surgeon. The number of referrals to secondary care, however, did not decrease and the number of arthroscopies was higher in the group that was randomized for prior MRI than in the group that was randomized for direct referral. This was the reason for the Dutch College of General Practitioners (NHG) to conclude in their clinical guideline ‘Traumatic knee complaints’ that ‘MRI referral by the GP offers no benefit for general practice and therefore isn’t recommended’ (Belo, 2010). However, the fact that referrals to secondary care did not decrease, was probably due to the study design. To prevent differences in waiting time, a provisional appointment with the (orthopaedic) surgeon was made for all patients in both groups. Subsequently, this appointment often was not cancelled in patients without pathology on MRI. Results of the DAMASK study are probably not totally applicable to the situation in the Netherlands.

The clinical guideline by the Dutch College of General Practitioners was one of the reasons for the Dutch multi-centre TACKLE Trial (Swart, 2014). From the discussion: ‘In the Netherlands, the additional diagnostic value and cost-effectiveness of direct access to knee MRI for patients presenting with traumatic knee complaints in general practice is unknown. Although GPs increasingly refer patients to MRI, the Dutch clinical guideline ‘Traumatic knee complaints’ for GPs does not recommend referral to MRI, mainly because the cost-effectiveness is still unknown.’ The objectives of this study were:

- To assess the cost-effectiveness of MRI referral by the general practitioner compared to usual care in patients with persistent traumatic knee complaints.

- To assess if MRI referral by the general practitioner is noninferior compared to usual care in patients with persistent traumatic knee complaints regarding self-reported knee related daily function.

To this end patients aged 18–45 years with traumatic knee symptoms seeking medical attention in a primary care setting were randomly assigned to usual care or MR Imaging. First results were recently published (Van Oudenaarde, 2018). The conclusion: MR imaging referral by the general practitioner was not cost-effective in patients with traumatic knee symptoms; in fact, MR imaging led to more healthcare costs, without an improvement in health outcomes. The recommendation from the authors: ‘For the moment, usual care as described in the Dutch general practice guidelines without referral for MR imaging and with referral to an orthopaedic surgeon in patients with persistent knee symptoms should be the guideline of choice’.

The role of conventional X-ray

The Ottowa knee rule is a validated and much used clinical decision rule that can be used in an acute setting, for instance in the emergency department, to decide whether an X-ray is needed. The X-ray will be used to exclude osseous pathology. This role will be reserved to X-ray as long as MRI has restricted availability in the acute phase and from a cost-effective point of view rightly so.

In a subacute setting, without equivocal history of trauma and when an MRI is warranted anyway, the situation is different. In young patients, an additional conventional X-ray next to MRI has no added value and is not required.

In older patients and in patients with suspected osteoarthritis of the knee, a weight bearing X-ray is preferable above an MRI. MRI has a higher sensitivity for osteoarthritis, but it is disputable whether abnormalities that are only visible on MRI and not on X-ray are clinically relevant. Furthermore, MRI probably doesn’t make sense in patients with known evident osteoarthritis and knee complaints. Osteoarthritis and meniscal pathology are often concomitant and when MRI is performed in patients with osteoarthritis in 80% of cases one or both of the menisci will show a degenerative tear. In these cases, it is questionable whether the osteoarthritis or the meniscal tear is cause the knee complaints and meniscectomy probably is not advisable. In these patients, meniscectomy should only be considered when there are mechanical symptoms (locked knee). Thus, there is no use for routine MRI in patients with (mild) osteoarthritis (Bhattacharyya, 2003; Suter, 2009). The age limit above which to consider weight bearing X-ray above routine MRI is arbitrary. Because there is a good chance of osteoarthritis above the age of 50 years, a cut-off point of 50 years seems reasonable.

MRI versus Ultrasound

In the considerations stated above, we already discussed the advantages and disadvantages of MRI and ultrasound in the work-up of knee injuries. The question is which is in our view the additional diagnostic imaging of choice? Advocates of ultrasound point to the fact that availability of ultrasound machines is higher than MRI systems. This may be true, but the limiting factor will probably be the availability of adequately trained and experienced ultrasonographers. Disadvantage compared with MRI is that the ultrasonographer has to perform the examination in person to make an adequate report, whereas MRI can be reported by a radiologist independent from moment and location of examination. This facilitates planning.

An MRI scan consists of multiple images of predefined thickness and interval in at least two orthogonal planes. This means every (orthopaedic) surgeon or radiologist can identify and locate pathology in the knee based on information visible in these images. Because ultrasound is a dynamic examination and the number of obtained images, orientation and quality of images is totally operator-dependent, only the reporter/ultrasonographer can extract all the information from an examination. Others will have to rely on the report. This will diminish the added value of ultrasound in pre-operative planning or in giving patient insight in the pathology.

Previous to arthroscopy osseous pathology (fracture, neoplasm) should be excluded by imaging. When arthroscopy is warranted, MRI can be used to exclude osseous pathology and X-ray is not required. Ultrasound cannot fulfil that role because visualization of osseous structures is insufficient. Additional imaging (X-ray) is required. This makes that ultrasound cannot be a stand-alone diagnostic tool before arthroscopy. Another disadvantage of ultrasound is the inability to visualize bone marrow changes at all or cartilage in a sufficient manner. Bone bruise or focal chondral lesions can mimic meniscal pathology and bone bruise pattern can point to specific trauma mechanisms and associated pathology. Compared with MRI, ultrasound, therefore, lacks in completeness.

In our opinion, MRI is the diagnostic imaging of choice in patients younger than 50 years and without unequivocal history (history of trauma, effusion and extension deficit) (Vincken, 2007). Ultrasound is not equivalent.

Cartilage Imaging

In recent years, there have been developments in MR imaging of cartilage. Techniques like T2-mapping and dGEMRIC provide information about the physiological content of cartilage and as such, can be used in detection of early damage and degradation of cartilage. These techniques will especially play a role in early detection and monitoring of osteoarthritis and less in the detection of focal chondral lesions. Because they are not yet widely used beyond clinical research, they will not be further discussed in this guideline.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

In the Netherlands, approximately 300,000 knee injuries occur yearly, from which most of them due to sports injuries. Because most of these injuries heal spontaneously, only a minority of patients are referred to secondary healthcare, i.e. to (orthopaedic) surgeons or sport physicians. The cause of knee complaints cannot always be determined with physical examination; often the use of additional diagnostic imaging, like Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or ultrasound, is necessary.

Arthroscopy is an invasive procedure. Most arthroscopies are performed in outpatient care. Arthroscopy examines the stability of the knee under anaesthesia, direct visualization of all intra-articular structures with high diagnostic accuracy and makes it possible to perform a therapeutic procedure in the same session. Limitations of arthroscopy are the invasiveness of the procedure, the need for hospitalization, the risk of complications and the absenteeism afterwards. Arthroscopies do not always result in a therapeutic procedure. The percentage of non-therapeutic arthroscopies of the knee vary between 27 and 61%.

MRI has a high accuracy in detecting intra-articular knee pathology. MRI can also provide additional information that cannot be obtained by arthroscopic diagnostic evaluation, for instance bone marrow edema. Ultrasound has lately been advocated as an alternative for MRI. Possible advantages of ultrasound are: availability, fastness and lower costs, although less is known about the diagnostic accuracy. All non-invasive examinations may prevent unnecessary arthroscopies and thereby, reduce costs and prevent morbidity related to arthroscopy. By means of a review of the literature, the role of MRI and ultrasound in the assessment of knee injuries will be evaluated.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

MRI & meniscal injury

|

Moderate GRADE |

Using MRI for diagnosing meniscal injury has a high sensitivity and moderate specificity.

References (Phelan, 2016; Smith, 2016) |

MRI & chondral lesions

|

Low GRADE |

Using MRI has a moderate sensitivity and a high specificity to diagnose chondral lesions

References (Zhang, 2013; Quatman, 2011) |

Ultrasonography

|

High GRADE |

Using ultrasonography has a moderate sensitivity and a high specificity to diagnose meniscal injury.

References (Dai, 2015; Xia, 2016) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description studies

The systematic review of Phelan (2016) investigated the diagnostic accuracy of MRI and US in the diagnosis of ACL, medial meniscus and lateral meniscus tears in people with suspected ACL and/or meniscal tears. Nineteen studies were included in a meta-analysis of the accuracy of MRI for the diagnosis of medial meniscal tears (N=1180) and 19 studies for lateral meniscal tears (N=1213). The evaluated MRI field strength ranged from 0.1 T to 3 T. There were only three studies included evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of US for meniscal tears (N=144). This number was insufficient to perform a meta-analyse for determining the accuracy of US for meniscal tears. The variability of the included studies was high. Phelan (2016) reported pooled diagnostic accuracy values only.

In the systematic review of Smith (2016), a meta-analysis was performed about the diagnostic accuracy of 3-T MRI for meniscal and ACL injuries, using arthroscopy as reference standard. Ten studies (between 2005 and 2012) were included in the meta-analysis with a total of 799 patients. All ten studies reported data for the diagnosis of lateral meniscus and medial meniscus tears.

Dai (2015) performed a systematic review about the diagnostic accuracy of US in the diagnosis of meniscal injury. A total of seven prospective studies (between 2006 and 2014) with 551 patients were included in a meta-analysis. All studies were prospectively designed and used arthroscopy as the sole reference standard. The QUADAS scores for the included studies was high (ranging from 10 to 13). No significant publication bias was found.

Xia (2016) performed a systematic review about the diagnostic accuracy of US in the diagnosis of meniscal injury. A total of 21 studies (between 1989 and 2014) with 3124 patients were included in a meta-analysis. 19 studies used arthroscopy as the sole reference standard, and two studies used MRI or CT as reference standard. Following the QUADAS scores, none of the included studies had an overall low risk of bias.

Zhang (2013) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis about the diagnostic accuracy of MRI in the grading of knee cartilage lesions. A total of 8 studies (between 1999 and 2009) with 454 patients were included in a meta-analysis. There was substantial heterogeneity across studies (I2=93%). Meta-regression showed that sample size, positive proportion, field strength, and QUADAS item 2 significantly affected the diagnostic accuracy of the index test.

Quatman (2011) performed a systematic review about the diagnostic accuracy of MRI for identifying articular cartilage abnormalities in the knee joint. A total of 27 studies were included, of which 14 studies (between 1994 and 2010) were Level I studies. Because of inconsistencies between imaging techniques and methodological shortcomings of many studies, a meta-analysis was not performed.

Results

1. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Medial meniscal injury

In the systematic review of Phelan (2016), the pooled sensitivity and specificity of MRI for detection of medical meniscal tears were 0.89 (95%CI 0.83 to 0.94) and 0.88 (95%CI 0.82 to 0.93) respectively. This means that 11% of the patients with meniscal tears could be missed, and 12% of the patients could have meniscal tears while the MRI diagnosis was normal. The pooled positive likelihood ratio was 7.98 (95%CI 4.7 to 13.4) and the pooled negative likelihood ratio was 0.1 (95% CI 0.7 to 0.2).

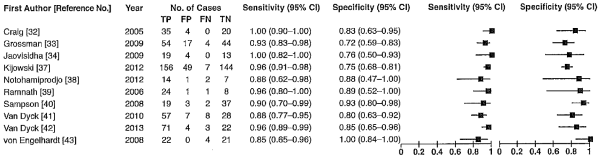

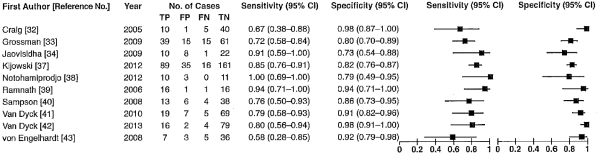

In the systematic review of Smith (2016), the pooled sensitivity and specificity of 3-T-MRI to diagnose medical meniscal injury were 0.94 (95%CI 0.91 to 0.96) and 0.79 (95%CI 0.75 to 0.83) respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Forest plot for detection of medial meniscal injury using 3-T MRI (Smith, 2016)

Lateral meniscal injury

In the systematic review of Phelan (2016), the pooled sensitivity and specificity of MRI for detection of lateral meniscal tears were 0.78 (95%CI 0.66 to 0.87) and 0.95 (95%CI 0.91 to 0.97) respectively. The pooled positive likelihood ratio was 14.5 (95% CI 8.7 to 24.3) and the pooled negative likelihood ratio was 0.2 (95%CI 0.2 to 0.4).

In the systematic review of Smith (2016), the pooled sensitivity and specificity of 3-T-MRI to diagnose lateral meniscal injury were 0.81 (95%CI 0.75 to 0.85) and 0.87 (95%CI 0.84 to 0.89) respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Forest plot for detection of lateral meniscal injury using 3-T MRI (Smith, 2016)

Knee cartilage lesions

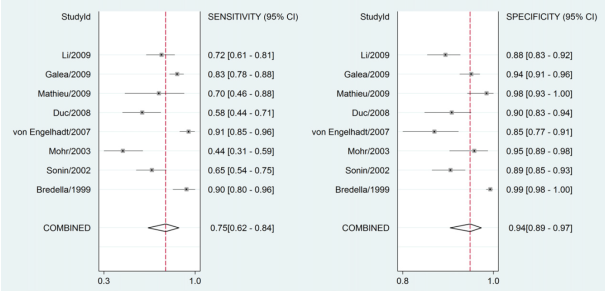

In the systematic review of Zhang (2013), the pooled sensitivity and specificity of MRI for detection of knee cartilage lesions were 0.75 (95%CI 0.62 to 0.84) and 0.94 (95%CI 0.89 to 0.97) respectively (Figure 3). The pooled positive likelihood ratio was 12.5 (95%CI 6.5 to 24.2) and the pooled negative likelihood ratio was 0.27 (95%CI 0.17 to 0.42).

Figure 3 Forest plot for detection of knee cartilage lesions using MRI (Zhang, 2013)

In the systematic review of Quatman (2011), no meta-analysis was performed. The sensitivity of MRI for detection of articular cartilage abnormalities among included studies ranged from 0.29 to 0.96 and the specificity ranged from 0.50 to 1.00.

2. Ultrasonography

Meniscal injury

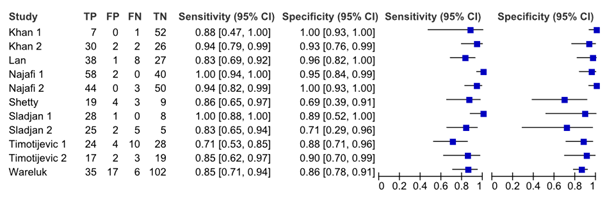

The meta-analysis of Dai (2015) showed a moderate pooled sensitivity of 0.88 (95%CI 0.84 to 0.91) and a high specificity of 0.90 (95%CI 0.86 to 0.93) of US in diagnosing meniscal injury (Figure 4). This means that 12% of the patients with meniscal injury could be missed, and 10% of the patients could have meniscal injury while the ultrasonography diagnosis is normal. The pooled positive likelihood was 7.07 (95%CI 4.34 to 11.52) and the negative likelihood was 0.17 (95%CI 0.10 to 0.26). There was moderate to high heterogeneity of these values (72.5% for sensitivity and 60.9% for specificity). Therefore, a sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding each study. This analysis decreased the heterogeneity, but the results were similar with the overall results.

Figure 4 Forest plot for diagnosis of meniscal injury using ultrasonography (Dai, 2015)

The systematic review of Phelan (2016) included only three studies evaluating diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound in the diagnosis of meniscal injury (Alizadeh, 2013; Khan, 2006; Timotijevic, 2014) and only one study in the diagnosis of ACL injury (Khan, 2006). The results of these study were not shown, and no meta-analysis was performed. However, all three studies were included in the meta-analysis of Dai (2015).

In the systematic review of Xia (2016) the pooled sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing meniscal injury using US were 0.78 (95% CI 0.75 to 0.80) and 0.84 (95% CI 0.82 to 0.86) respectively. However, in this pooled analysis the data of nine studies published before 2006 were also included. The diagnostic performance of US was specified for each included study for different meniscal injuries (lateral, medial, total) in the published article.

Level of evidence

MRI & meniscal injury: The level of evidence for diagnosing meniscal injury was downgraded with 1 level because of limitations in the study design (risk of bias, due to patient selection (nonrandomized) and interpretation of MRI).

MRI & chondral lesions: The level of evidence for diagnosing chondral lesions was downgraded with 2 levels because of limitations in the study design (risk of bias, due to patient selection (nonrandomized) and interpretation of MRI) and inconsistency of results (wide variance of point estimates across studies).

Ultrasonography: The level of evidence for diagnosing meniscal injury was not downgraded.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

Is MRI, ultrasonography or X-ray recommended in assessing meniscal injury or chondral lesions prior to performing arthroscopy?

P: patients with a suspected meniscal injury (history of trauma or hydrops);

I: MRI, ultrasonography, X-ray;

C: arthroscopy;

O: patient relevant outcomes: number of non-therapeutic arthroscopies, cost effectiveness, test characteristics (sensitivity and specificity).

Relevant outcome measures

The working group considered test characteristics as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and cost effectiveness an important outcome measure for decision making.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms. For the update the database Medline was searched from the previous search till February 2017. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The updated systematic literature search resulted in 1031 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- systematic review (searched in at least two databases with an objective and transparent search strategy, data extraction and methodological rating) of randomized trials comparing imaging techniques with arthroscopy in the diagnostic process of meniscal injury.

35 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract. After reading the full text, 29 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and six studies were included.

Six studies were included in the literature analysis. The diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) versus arthroscopy was studied in two recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses for diagnosis of meniscal injury (Phelan, 2016; Smith, 2016), and in two systematic reviews and one meta-analysis for knee cartilage lesions (Quatman, 2011; Zhang, 2013). Three recent systematic reviews studied the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography (US) versus arthroscopy in the diagnosis of meniscal injury (Phelan, 2016; Xia, 2016; Dai, 2015). No systematic reviews were found investigating the diagnostic accuracy of X-ray. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

New versus old (2010)

The meta-analyses included in the previous guideline (Crawford, 2007; Oei, 2003) were compared with the results included in the updated literature analysis. In contrast to the previous reviews, the newly included meta-analyses (Phelan, 2016; Smith, 2012) only included prospective studies with very low risk of verification bias. Therefore, the old literature was replaced by the results of these new meta-analyses.

Referenties

- Alizadeh A, Babaei Jandaghi A, Keshavarz Zirak A, Karimi A, Mardani-Kivi M, Rajabzadeh A. Knee sonography as a diagnostic test for medial meniscal tears in young patients. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2013 Dec;23(8):927-31.

- Dai H, Huang ZG, Chen ZJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography in assessing meniscal injury: meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Orthop Sci. 2015;20(4):675-81.

- Khan Z, Faruqui Z, Ogyunbiyi O, Rosset G, Iqbal J. Ultrasound assessment of internal derangement of the knee. Acta Orthop Belg. 2006 Jan;72(1):72-6.

- Phelan N, Rowland P, Galvin R, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of MRI for suspected ACL and meniscal tears of the knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(5):1525-39.

- Quatman CE, Hettrich CM, Schmitt LC, et al. The clinical utility and diagnostic performance of magnetic resonance imaging for identification of early and advanced knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(7):1557-68.

- Smith C, McGarvey C, Harb Z, et al. Diagnostic Efficacy of 3-T MRI for Knee Injuries Using Arthroscopy as a Reference Standard: A Meta-Analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;207(2):369-77.

- Timotijevic S, Vukasinovic Z, Bascarevic Z. Correlation of clinical examination, ultrasound sonography, and magnetic resonance imaging findings with arthroscopic findings in relation to acute and chronic lateral meniscus injuries. J Orthop Sci. 2014 Jan;19(1):71-6.

- Van Oudenaarde K, Swart NM, Bloem JL, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Algra PR, Bindels PJE, Koes BW, Nelissen RGHH, Verhaar JAN, Luijsterburg PAJ, Reijnierse M, van den Hout WB. General Practitioners Referring Adults to MR Imaging for Knee Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial to Assess Cost-effectiveness. Radiology. 2018 Jul;288(1):170-176. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018171383. Epub 2018 Apr 17. PubMed PMID: 29664339.

- Vincken PW, ter Braak AP, van Erkel AR, Coerkamp EG, de Rooy TP, de Lange S, Mallens WM, Coene LN, Bloem RM, van Luijt PA, van den Hout WB, van Houwelingen HC, Bloem JL. MR imaging: effectiveness and costs at triage of patients with nonacute knee symptoms. Radiology. 2007 Jan;242(1):85-93. Epub 2006 Nov 7. PubMed PMID: 17090714.

- Xia XP, Chen HL, Zhou B. Ultrasonography for meniscal injuries in knee joint: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2016;56(10):1179-87.

- Zhang M, Min Z, Rana N, et al. Accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging in grading knee chondral defects. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(2):349-56.

Evidence tabellen

Research question: Is MRI, ultrasonography or X-ray recommended in assessing meniscal injury or chondral lesions prior to performing arthroscopy?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics

|

Index test (test of interest) |

Reference test |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Phelan, 2016 |

SR and meta-analysis

Literature search up to March 2014

A: Sladjan, 2014 B: Arif, 2013 C: Alizadeh, 2013 D: Behairy, 2009 E: Von Engelhardt, 2008 F: Khan, 2006 G: Jah, 2005 H: Munshi, 2000 I: Riel, 1999 J: Munk, 1998 K: Rappeport, 1997 L: Franklin, 1997 M: Bui-Mansfield, 1997 N: Miller, 1996 O: Kinnunen, 1994 P: Spiers, 1993 Q: Grevitt, 1992 R: Raunest, 1991 S: Niitse, 1991 T: Glashow, 1989 U: Polly, 1988

Study design: prospective cohort or cross-sectional studies

Setting: hospital

Country: A: Serbia B: Pakistan C: Iran D: Egypt E, I: Germany F: Saudi Arabia G: Iran H: Canada J, K: Denmark L: America M, N, T, U: USA O: Finland P, Q: England R: Germany S: Japan

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: (not reported |

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

14 studies for ACL tears, 19 for medial meniscal tears, 19 for lateral meniscal tears included

N, mean age, % male A: 107 patients, 29.2 yr, 87% B: 50 patients, 30 yr, 96% C: 74 patients, 33.5 yr, 73% D: 70 patients, age NR, 59% E: 43 patients, 52 yr, 51% F: 60 patients, 35 yr, 100% G: 70 patients, 27.9 yr, 81% H: 23 patients, 26 yr, 78% I: 244 patients, 36 yr, 57% J: 61 patients, 31.4 yr, 67% K: 47 patients, 34 yr, 72% L: 35 patients, 39.5 yr, 69% M: 50 patients, 31 yr, 90% N: 57 patients, 37.5 yr, sex NR O: 33 patients, 36 yr, 48% P: 58 patients, 28.9 yr, 64% Q: 55 patients, 36 yr, 69% R: 50 patients, 40.9 yr, 72% S: 52 patients, 25 yr, 56% T: 50 patients, 36 yr, 56% U: 50 patients, 32.9 yr, 90% |

MRI Field Strength O: 0.1 T I, L, Q: 0.2 T K: 0.22 T T: 0.35 T N: 0.35-1.5 T A, B, C, D, F, G, H, M, P, R, S, U: 1.5 T E: 3 T

|

Arthroscopy

|

Follow-up not reported

|

ACL tear (95% CI) Pooled sensitivity: 0.87 (0.77 to 0.94) Pooled specificity: 0.93 (0.91 to 0.96) LR+: 14.4 (9.2 to 22.5) LR-: 0.1 (0.1 to 0.3)

Medial meniscal tear (95% CI) Pooled sensitivity: 0.89 (0.83 to 0.94) Pooled specificity: 0.88 (0.82 to 0.93) LR+: 7.98 (4.7 to 13.4) LR-: 0.1 (0.07 to 0.2)

Lateral meniscal tear (95% CI) Pooled sensitivity: 0.78 (0.66 to 0.87) Pooled specificity: 0.95 (0.91 to 0.97) LR+: 14.5 (8.7 to 24.3) LR-: 0.2 (0.2 to 0.4) |

Risk of bias in most included studies is high or unclear in relation the reference standard.

Insufficient number of studies that evaluated US to perform a meta-analysis.

Heterogeneity not reported.

|

|

Smith, 2016 |

SR and meta-analysis

Literature search date not reported

A: Craig, 2005 B: Grossman, 2009 C: Jaovisidha, 2009 D: Kijowski, 2012 E: Notohamiprodjo, 2012 F: Ramnath, 2006 G: Sampson, 2008 H: Van Dyck, 2010 I: Van Dyck, 2013 J: Von Engelhardt, 2008

Study design: cohort, case-control (prospective / retrospective)

Setting and Country:

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: (commercial / non-commercial funding/ industrial co-authorship / potential conflicts of interest )

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

10 studies included

N, mean age A: 58 patients, 41.9 yr, 67% male B: 100 patients,37.1 yr, 42% male C: 32 patients, 36.4 yr, 81% male D: 250 patients, 37.3 yr, 58% male E: 22 patients, 52.0 yr, 54% male F: 34 patients,48.9 yr, 59% male G: 61 patients, 29.6 yr, 85% male H: 100 patients, 49.0 yr, 58% male I: 100 patients, 49.0 yr, 71% male J: 42 patients, 52.0 yr, 52% male

|

MRI Field Strength 3-T

|

Arthroscopy

|

Time between MRI and arthroscopy A: 56.0 days B: 62.9 days C: 93.0 days D: 35.3 days E: <90 days F: 38.0 days G: 45.0 days H: 36.0 days I: 46.0 days J: 4.40 days

|

ACL tear (95% CI) Pooled sensitivity: 0.92 (0.83 to 0.96) Pooled specificity: 0.99 (0.96 to 1.00) LR+: 44.53 (13.06 to 151.77) LR-: 0.07 (0.01 to 0.51)

Medial meniscal tear (95% CI) Pooled sensitivity: 0.94 (0.91 to 0.96) Pooled specificity: 0.79 (0.75 to 0.83) LR+: 4.37 (3.42 to 5.57) LR-: 0.09 (0.07 to 0.14)

Lateral meniscal tear (95% CI) Pooled sensitivity: 0.81 (0.75 to 0.85) Pooled specificity: 0.79 (0.75 to 0.83) LR+: 4.37 (3.42 to 5.57) LR-: 0.09 (0.07 to 0.14) |

All the included studies were of high quality

Brief description of author’s conclusion: the meta-analysis showed excellent diagnostic ability of 3-T MRI for detecting medical meniscal, lateral meniscal and ACL injuries

|

|

Xia, 2016 |

SR

Literature search up to January 2015

A: Cook, 2014 B: Alizadeh, 2012 C: Wareluk, 2012 D: Shanbhogue, 2009 E: Shetty, 2008 F: Timotijevic, 2008 G: Helwig, 2007 H: Sandhu, 2007 I: Helwig, 2006 J: Najafi, 2006 K: Khan, 2006 Studies <2006 not included

Study design: All prospective cohort studies (not reported for D and H)

Country: A: USA B: Iran C: Poland D: India E: UK F: Serbia G: Germany H: India I: Germany J: Iran K: UK

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Non-commercial, no conflicts of interest

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

20 studies included (11 studies from 2006)

N, mean age, sex A: 71 patients, 15-73 yr, 56% male B: 74 patients, ≤30 yr, 73% male C: 80 patients, 36.2 yr, 48% male D: 35 patients, 26.2 yr, 69% male E: 35 patients, 47 yr, 57% male F: 198 patients, age NR, sex NR G: 41 patients, 48 yr, 54% male H: 51 patients age NR, sex NR I: 34 patients, 49 yr, 50% male J: 100 patients, ≥20 yr, 95% male K: 81 patients, 35 yr, 100% male

|

Ultrasonography A: portable machine (10-14 MHz) B: B-mode US (14 MHz) C: Voluson 730 (6-12 MHz) D: ATL-HDI-5000 machine (5-12 MHz) E: ES AOTE Technos MPS (5-13 MHz) F: 5-7.5 MHz G: 11.7 MHz H: I: 11.7 MHz

|

Arthroscopy A, B, C, E, F, G, H, I, J, K

MRI D

|

Follow-up not reported

|

Meniscal injury (95% CI) Pooled sensitivity: 0.78 (0.75 to 0.80) Pooled specificity: 0.84 (0.82 to 0.86)

|

No included study overall low risk of bias (QUADAS-2)

Brief description of author’s conclusion: diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography for meniscal injuries was good. MRI no better accuracy than ultrasonography. Ultrasonography recommended for evaluation meniscal injuries.

|

|

Dai, 2015 |

SR and meta-analysis

Literature search up to November 2014

A: Timotijevic, 2014 B: Alizadeh, 2013 C: Wareluk, 2012 D: Shetty, 2008 E: Khan, 2006 F: Lan, 2006 G: Nafaji, 2006

Study design: Prospective cohort studies

Country: A: Serbia B: Iran C: Poland D: UK E: Saudi Arabia F: China G: Iran

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

7 studies included

N, mean age A: 107 patients, 29.2 yr B: 74 patients, 43.5 yr C: 80 patients, 36.2 yr D: 35 patients, 47 yr E: 81 patients, 35 yr F: 74 patients, 38.5 yr G: 100 patients, age NR

|

Ultrasonography Technique A: Siemens, 5-7.5 MHz linear probes B: SONIX OP, 14 MHz linear probes C: Voluson 730, 6-12 MHz linear probe D: ESAOTE Technos MPS, 5-13 MHz probe E: Acuson 128, 7.5 MHz linear probe F: Aloka SSD 7.5-10 MHz linear probe G: Concept/MC system, 6.5 MHz micro convex probe

|

Arthroscopy

|

Endpoint of follow-up: not reported

|

Meniscal injury Pooled sensitivity: 0.88 (0.84 to 0.91), I2=72.5% Pooled specificity: 0.90 (0.86 to 0.93), I2=60.9% LR+: 7.07 (4.342 to 11.52), I2=46.6% LR-: 0.17 (0.10 to 0.26), I2=51.6%

|

The diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography for diagnosing meniscal injury was acceptable, with high specificity but moderate sensitivity

|

|

Zhang, 2013 |

SR and meta-analysis

Literature search up to February 2012

A: Bredella, 1999 B: Sonin, 2002 C: Mohr, 2003 D: Von Engelhardt, 2007 E: Duc, 2008 F: Mathieu, 2009 G: Galea, 2009 H: Li, 2009

Study design: all prospective, except B, C (retrospective)

Country: A, B, C: USA D: Germany E: Switzerland F: France G: UK H: China

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported

|

Inclusion criteria SR: diagnostic accuracy of MRI in knee cartilage lesions, knee degeneration or traumatic damage patients, arthroscopic outcome as reference, 6 articular surfaces evaluated separately, grading classification on MRI.

Exclusion criteria SR: studies with inadequate mapping of chondral defects and MR arthrography or contrast-enhancement MRI.

8 studies included

N, mean age A: 130 patients, 41 yrs B: 54 patients, 33.7 yr C: 26 patients, 37 yr D: 40 patients, 49.5 yr E: 29 patients, 41.0 yr F: 21 patients, 35.7 yr G: 100 patients H: 54 patients, 36.0 yr

|

MRI Field strength A, B, C, D, E, F, H: 1.5 T G: 3.0 T

|

Arthroscopy

|

Follow-up not reported

|

Knee cartilage lesions Sensitivity/ specificity (95% CI) A: 0.90 (0.80-0.96) / 0.99 (0.98-1.00) B: 0.65 (0.54-0.75) / 0.89 (0.85-0.93) C: 0.44 (0.31-0.59) / 0.95 (0.89-0.98) D: 0.91 (0.85-0.96) / 0.85 (0.77-0.91) E: 0.58 (0.44-0.71) / 0.90 (0.83-0.94) F: 0.70 (0.46-0.88) / 0.98 (0.93-1.00) G: 0.83 (0.78-0.88) / 0.94 (0.91-0.96) H: 0.72 (0.61-0.81) / 0.88 (0.83-0.92)

Pooled sensitivity: 0.75 (95%CI 0.62 to 0.84) Pooled specificity: 0.94 (95% CI 0.89 to 0.97) (%)) |

Brief description of author’s conclusion: MRI was effective in discriminating normal morphologic cartilage from disease but was less sensitive in detecting knee chondral lesions.

I2=93% Meta-regression showed that sample size, positive proportion, field strength and QUADAS item 2 were affecting diagnostic accuracy.

|

|

Quatman, 2011 |

SR (no meta-analysis)

Literature search up to November 2010

A: Bredella, 1999 B: Disler, 1995 C: Disler, 1996 D: Duc, 2007 E: Galea, 2009 F: Irie, 2000 G: Kijowski, 2009a H: Kijowski, 2010 I: Kijowski, 2009b J: Kramer, 1994 K: Li, 2009 L: Potter, 1998 M: Vallotton, 1995 N: Von Engelhardt, 2010

Study design: All prospective studies, except C (retrospective)

Setting and Country: not reported

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported

|

Inclusion criteria SR: - Human knee - both MRI and arthroscopy were performed in the study - diagnostic performance of MRI compared to arthroscopy is reported or can be calculated - minimum of 10 subjects with articular cartilage involvement - full manuscript provided in English or translated - MRI sequences and magnet strength reported - Minimum of 1.5 Tesla magnet used for MRI

Exclusion criteria: - Summary or clinical commentary articles - Case studies - Intervention studies (microfracture, autologous chondrocyte implantation, ACL reconstruction, osteoarticular transfer system procedure) - Cadaveric specimens - Pathology other than articular cartilage defects

27 studies included, from which 14 Level 1 studies (described in this evidence table)

Important patient characteristics: N A: 130 patients B: 43 patients C: 47 patients D: 30 patients E: 100 patients F: 29 patients G: 100 patients H: 257 patients I: 95 patients J: 58 patients K: 54 patients L: 90 patients M: not reported N: 40 patients

Age and sex not reported |

MRI Field strength A, B, C, D, E, F, H, I, J, K, L, M: 1.5 T G, N: 3.0 T

|

Arthroscopy

|

Endpoint of follow-up: Not reported

|

Articular cartilage abnormalities Sensitivity/ specificity (95% CI not reported) A: 0.94 / 0.99 B: 0.29-0.38 / 0.97; 0.75-0.85 / 0.97 C: 0.29-0.38 / 0.97; 0.75-0.85 / 0.97 D: 0.52-0.74 / 0.78-0.95 E: 0.83 / 0.94 F: not reported G: 0.68 / 0.93; 0.73 / 0.88 H: 0.66 / 0.92; 0.69 / 0.93 I: 0.78 / 0.88; 0.77 / 0.92 J: 0.62 / 0.50; 0.85 / 1.00; 0.87 / 1.00 K: 0.82 / 0.90-0.92; 0.76-0.80 / 0.94 L: 0.87 / 0.94 M: 0.85 / 0.97 N: 0.91 / 0.85

|

Retrospective studies also included. Low methodological quality of included studies. A large range of diagnostic accuracy was found.

Level I studies: consecutive patients (as stated by the original authors), prospective data collection, and utilized established diagnostic criteria with gold standard comparison (arthroscopy

|

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of diagnostic studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea, 2007; BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher, 2009; PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

Research question: Is MRI, ultrasonography or X-ray recommended in assessing meniscal injury or chondral lesions prior to performing arthroscopy?

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?5

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?8

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Phelan, 2016 |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Smith, 20016 |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Xia, 2016 |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Dai, 2015 |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Zhang, 2013 |

Yes |

No (only Pubmed) |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Smith, 2012 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Quatman, 2011 |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate (in relation to the research question to be answered in the clinical guideline) and predefined.

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched.

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons.

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to the research question (PICO) should be reported.

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (preferably QUADAS-2; COSMIN checklist for measuring instruments) and taken into account in the evidence synthesis.

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, diagnostic tests (strategy) to allow pooling? For pooled data: at least 5 studies available for pooling; assessment of statistical heterogeneity and, more importantly (see Note), assessment of the reasons for heterogeneity (if present)? Note: sensitivity and specificity depend on the situation in which the test is being used and the thresholds that have been set, and sensitivity and specificity are correlated; therefore, the use of heterogeneity statistics (p-values; I2) is problematic, and rather than testing whether heterogeneity is present, heterogeneity should be assessed by eye-balling (degree of overlap of confidence intervals in Forest plot), and the reasons for heterogeneity should be examined.

- There is no clear evidence for publication bias in diagnostic studies, and an ongoing discussion on which statistical method should be used. Tests to identify publication bias are likely to give false-positive results, among available tests, Deeks’ test is most valid. Irrespective of the use of statistical methods, you may score “Yes” if the authors discuss the potential risk of publication bias.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 04-03-2019

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 04-03-2019

Voor het beoordelen van de actualiteit van deze richtlijn is de werkgroep wel in stand gehouden. Uiterlijk in 2024 bepaalt het bestuur van de NOV of de modules van deze richtlijn nog actueel zijn. Op modulair niveau is een onderhoudsplan beschreven. Bij het opstellen van de richtlijn heeft de werkgroep per module een inschatting gemaakt over de maximale termijn waarop herbeoordeling moet plaatsvinden en eventuele aandachtspunten geformuleerd die van belang zijn bij een toekomstige herziening (update). De geldigheid van de richtlijn komt eerder te vervallen indien nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding zijn een herzieningstraject te starten.

De NOV en de NVvR zijn regiehouders van deze module en eerstverantwoordelijke op het gebied van de actualiteitsbeoordeling van de richtlijn. De andere aan deze richtlijn deelnemende wetenschappelijke verenigingen of gebruikers van de richtlijn delen de verantwoordelijkheid en informeren de regiehouder over relevante ontwikkelingen binnen hun vakgebied.

|

Module1 |

Regiehouder(s)2 |

Jaar van autorisatie |

Eerstvolgende beoordeling actualiteit richtlijn3 |

Frequentie van beoordeling op actualiteit4 |

Wie houdt er toezicht op actualiteit5 |

Relevante factoren voor wijzigingen in aanbeveling6 |

|

Submodule: Plaats van MRI, echografie en röntgenfoto in diagnostiek knieletsels |

NOV, NVvR |

2019 |

2024 |

Eens in 5 jaar |

NVvR |

- |

1 Naam van de module

2 Regiehouder van de module (deze kan verschillen per module en kan ook verdeeld zijn over meerdere regiehouders)

3 Maximaal na vijf jaar

4 (half)Jaarlijks, eens in twee jaar, eens in vijf jaar

5 Regievoerende vereniging, gedeelde regievoerende verenigingen, of (multidisciplinaire) werkgroep die in stand blijft

6 Lopend onderzoek, wijzigingen in vergoeding/organisatie, beschikbaarheid nieuwe middelen

Algemene gegevens

De richtlijnontwikkeling werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.kennisinstituut.nl) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

Doel en doelgroep

Doel

Deze richtlijn beoogt uniform beleid ten aanzien van de zorg bij patiënten met knieletsels die mogelijk behandeld kunnen worden met een artroscopische ingreep.

Doelgroep

Deze richtlijn is geschreven voor alle leden van de beroepsgroepen van orthopaedisch chirurgen, sportartsen, fysiotherapeuten, radiologen en traumachirurgen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met (acute) knieletsels. Daarnaast is deze richtlijn bedoeld om zorgverleners die anderzijds betrokken zijn bij deze patiënten, te informeren, waaronder kinderartsen, revalidatieartsen, huisartsen, physician assistants en verpleegkundig specialisten.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijn is in 2016 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met (acute) knieletsels te maken hebben. De werkgroepleden zijn door hun beroepsverenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname. De werkgroep is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze richtlijn.

- Dr. E.R.A. (Ewoud) van Arkel, orthopedisch chirurg, werkzaam in het Haaglanden Medisch Centrum te Den Haag, NOV, voorzitter

- Drs. A. (Bert) van Essen, sportarts, werkzaam bij het Maxima Medisch Centrum te Veldhoven, VSG

- Dr. S. (Sander) Koëter, orthopedisch chirurg, werkzaam in het Canisius Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis te Nijmegen, NOV

- Drs. N. (Nicky) van Melick, sportfysiotherapeut en bewegingswetenschapper, werkzaam bij het Knie Expertise Centrum te Eindhoven, KNGF

- Dr. P.C. (Paul) Rijk, orthopedisch chirurg, werkzaam in het Medisch Centrum Leeuwarden te Leeuwarden, NOV

- Drs. M.J.M. (Michiel) Segers, traumachirurg, werkzaam in het Sint Antonius Ziekenhuis te Utrecht, NVvH

- Dr. T.G. (Tony) van Tienen, orthopedisch chirurg, werkzaam in de kliniek Via Sana te Mill, NOV

- Dr. P.W.J. (Patrice) Vincken, radioloog, werkzaam bij Alrijne Zorggroep te Leiderdorp, NVvR

Meelezers:

- Patiëntenfederatie Nederland te Utrecht

Met ondersteuning van:

- Dr. B.H. (Bernardine) Stegeman, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. J. (Janneke) Hoogervorst-Schilp, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De KNMG-Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of ze in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatie management, kennisvalorisatie) hebben gehad. Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Arkel, van (voorzitter) |

Orthopaedisch chirurg |

Opleider orthopedie Haaglanden Medisch Centrum |

- |

Geen actie |

|

Essen, van |

Sportarts |

Medisch directeur SMC |

- |

Geen actie |

|

Tienen, van |

Orthopaedisch chirurg |

|

- |

Geen actie (meniscusimplantaten en knieprotheses vallen buiten de afbakening van de richtlijn) |

|

Melick |

Sportfysiotherapeut |

|

- |

Geen actie (valt buiten de afbakening van de richtlijn) |

|

Rijk |

Orthopaedisch chirurg |

- |

- |

Geen actie |

|

Vincken |

Radioloog |

- |

- |

Geen actie |

|

Segers |

Traumachirurg |

Consultant voor DePuy Synthes Trauma |

- |

Geen actie (producten geproduceerd door DePuy Synthes Trauma vallen buiten de afbakening van de richtlijn) |

|

Koëter |

Orthopaedisch chirurg |

Hoofd research support office CWZ |

- |

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door een meelezer vanuit de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland. Tijdens de oriënterende zoekactie werd gezocht op literatuur naar patiëntenperspectief (zie Strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur). De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

In de verschillende fasen van de richtlijnontwikkeling is rekening gehouden met de implementatie van de richtlijn (module) en de praktische uitvoerbaarheid van de aanbevelingen. Daarbij is uitdrukkelijk gelet op factoren die de invoering van de richtlijn in de praktijk kunnen bevorderen of belemmeren. Het implementatieplan is te vinden bij de aanverwante producten.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijn is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010), dat een internationaal breed geaccepteerd instrument is. Voor een stap-voor-stap beschrijving hoe een evidence-based richtlijn tot stand komt wordt verwezen naar het stappenplan Ontwikkeling van Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Knelpuntenanalyse

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerden de voorzitter van de werkgroep en de adviseur de knelpunten. De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbevelingen uit de eerdere richtlijn (NOV, 2010) op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door een Invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten. De werkgroep stelde vervolgens een long list met knelpunten op en prioriteerde de knelpunten op basis van: (1) klinische relevantie; (2) de beschikbaarheid van (nieuwe) evidence van hoge kwaliteit; (3) en de te verwachten impact op de kwaliteit van zorg, patiëntveiligheid en (macro)kosten.

Uitgangsvragen en uitkomstmaten

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de voorzitter en de adviseur concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld. Deze zijn met de werkgroep besproken waarna de werkgroep de definitieve uitgangsvragen heeft vastgesteld. Vervolgens inventariseerde de werkgroep per uitgangsvraag welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als kritiek, belangrijk (maar niet kritiek) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de kritieke uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur

Er werd eerst oriënterend gezocht naar bestaande buitenlandse richtlijnen (via Medline (OVID), GIN en NICE), systematische reviews (via Medline, en literatuur over patiëntenvoorkeuren en patiëntrelevante uitkomstmaten (patiëntenperspectief; Medline (OVID)). Vervolgens werd voor de afzonderlijke uitgangsvragen aan de hand van specifieke zoektermen gezocht naar gepubliceerde wetenschappelijke studies in (verschillende) elektronische databases. Tevens werd aanvullend gezocht naar studies aan de hand van de literatuurlijsten van de geselecteerde artikelen. In eerste instantie werd gezocht naar studies met de hoogste mate van bewijs. De werkgroepleden selecteerden de via de zoekactie gevonden artikelen op basis van vooraf opgestelde selectiecriteria. De geselecteerde artikelen werden gebruikt om de uitgangsvraag te beantwoorden. De databases waarin is gezocht, de zoekstrategie en de gehanteerde selectiecriteria zijn te vinden in de module met desbetreffende uitgangsvraag. De zoekstrategie voor de oriënterende zoekactie en patiëntenperspectief zijn opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Kwaliteitsbeoordeling individuele studies

Individuele studies werden systematisch beoordeeld, op basis van op voorhand opgestelde methodologische kwaliteitscriteria, om zo het risico op vertekende studieresultaten (risk of bias) te kunnen inschatten. Deze beoordelingen kunt u vinden in de Risk of Bias (RoB) tabellen. De gebruikte RoB instrumenten zijn gevalideerde instrumenten die worden aanbevolen door de Cochrane Collaboration: AMSTAR – voor systematische reviews; Cochrane – voor gerandomiseerd gecontroleerd onderzoek; Newcastle-Ottawa – voor observationeel onderzoek; QUADAS II – voor diagnostisch onderzoek.

Samenvatten van de literatuur

De relevante onderzoeksgegevens van alle geselecteerde artikelen werden overzichtelijk weergegeven in evidence-tabellen. De belangrijkste bevindingen uit de literatuur werden beschreven in de samenvatting van de literatuur. Bij een voldoende aantal studies en overeenkomstigheid (homogeniteit) tussen de studies werden de gegevens ook kwantitatief samengevat (meta-analyse) met behulp van Review Manager 5.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

A) Voor interventievragen (vragen over therapie of screening)

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie (Schünemann, 2013).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

B) Voor vragen over diagnostische tests, schade of bijwerkingen, etiologie en prognose

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd eveneens bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode: GRADE-diagnostiek voor diagnostische vragen (Schünemann, 2008), en een generieke GRADE-methode voor vragen over schade of bijwerkingen, etiologie en prognose. In de gehanteerde generieke GRADE-methode werden de basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek toegepast: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van bewijskracht op basis van de vijf GRADE-criteria (startpunt hoog; downgraden voor risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias).

Formuleren van de conclusies

Voor elke relevante uitkomstmaat werd het wetenschappelijk bewijs samengevat in een of meerdere literatuurconclusies waarbij het niveau van bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methodiek. De werkgroepleden maakten de balans op van elke interventie (overall conclusie). Bij het opmaken van de balans werden de gunstige en ongunstige effecten voor de patiënt afgewogen. De overall bewijskracht wordt bepaald door de laagste bewijskracht gevonden bij een van de kritieke uitkomstmaten. Bij complexe besluitvorming waarin naast de conclusies uit de systematische literatuuranalyse vele aanvullende argumenten (overwegingen) een rol spelen, werd afgezien van een overall conclusie. In dat geval werden de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de interventies samen met alle aanvullende argumenten gewogen onder het kopje Overwegingen.

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals de expertise van de werkgroepleden, de waarden en voorkeuren van de patiënt (patient values and preferences), kosten, beschikbaarheid van voorzieningen en organisatorische zaken. Deze aspecten worden, voor zover geen onderdeel van de literatuursamenvatting, vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje Overwegingen.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk. De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen.

Randvoorwaarden (Organisatie van zorg)

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijn is expliciet rekening gehouden met de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, menskracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van een specifieke uitgangsvraag maken onderdeel uit van de overwegingen bij de bewuste uitgangsvraag. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg rond artroscopie knie.

Kennislacunes

Tijdens de ontwikkeling van deze richtlijn is systematisch gezocht naar onderzoek waarvan de resultaten bijdragen aan een antwoord op de uitgangsvragen. Bij elke uitgangsvraag is door de werkgroep nagegaan of er (aanvullend) wetenschappelijk onderzoek gewenst is om de uitgangsvraag te kunnen beantwoorden. Een overzicht van de onderwerpen waarvoor (aanvullend) wetenschappelijk van belang wordt geacht, is als aanbeveling in de Kennislacunes beschreven (onder aanverwante producten).

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijn werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijn aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijn werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0. Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site.html. 2012.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ. 2008;336(7653):1106-10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39500.677199.AE. Erratum in: BMJ. 2008;336(7654). doi: 10.1136/bmj.a139. PubMed PMID: 18483053.

Ontwikkeling van Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen: stappenplan. Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten.

Zoekverantwoording

|

Database |

Zoektermen |

Totaal |

|

Medline (OVID) |

9 Knee/ or exp Knee Joint/ or Menisci, Tibial/ or menisc*.ti,ab,kf. or knee*.ti,ab,kf. or exp Knee Injuries/ or Tibial Meniscus Injuries/ or ((*Anterior Cruciate Ligament/ or (anterior cruciate ligament or ACL).ti.) and (rupture* or injur*).ab,ti.) (142941) 10 exp Diagnostic Imaging/ or (Magnetic Resonance Imaging or MRI or imaging or ultrasound or ultrasonograph* or x-ray).ti,ab,kf. or exp "Knee Injuries"/di, dg (2852795) 11 9 and 10 (39706) 12 8 and 11 (7) 13 exp "Sensitivity and Specificity"/ or (Sensitiv* or Specific*).ti,ab. or (predict* or ROC-curve or receiver-operator*).ti,ab. or (likelihood or LR*).ti,ab. or exp Diagnostic Errors/ or (inter-observer or intra-observer or interobserver or intraobserver or validity or kappa or reliability).ti,ab. or reproducibility.ti,ab. or (test adj2 (re-test or retest)).ti,ab. or "Reproducibility of Results"/ or accuracy.ti,ab. or Diagnosis, Differential/ or Validation Studies.pt. or exp "Arthroscopy"/ or arthroscop*.ti,ab. (5435802) 14 11 and 13 (15035) 15 limit 14 to (english language and yr="2009 -Current") (6526) 16 limit 14 to ed=20090813-20091231 (215) 17 15 or 16 (6545) 18 limit 17 to english language (6530) 19 (meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (meta adj analy$).tw. or ((systematic* or literature) adj2 review$1).tw. or (systematic adj overview$1).tw. or exp "Review Literature as Topic"/ or cochrane.ab. or cochrane.jw. or embase.ab. or medline.ab. or (psychlit or psyclit).ab. or (cinahl or cinhal).ab. or cancerlit.ab. or ((selection criteria or data extraction).ab. and "review"/)) not (Comment/ or Editorial/ or Letter/ or (animals/ not humans/)) (308902) 20 18 and 19 (226) – na voorselectie adviseur (JH) >44 21 (exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or random*.ti,ab. or (clinic* adj trial*).tw. or ((singl* or doubl* or treb* or tripl*) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo*.tw.) not (animals/ not humans/) (1666435) 22 18 and 21 (907) 23 22 not 20 (863) 24 remove duplicates from 20 (220) 25 remove duplicates from 23 (811) – na voorselectie adviseur (JH) >90 |

1031 – na voorselectie adviseur (JH): 134 |

Tabel Exclusie na het lezen van het volledige artikel

|

Author and year |

Reasons for exclusion |

|

Potential systematic reviews |

|

|

Campbell, 2014 |

MRI accuracy for the size of ACL |

|

De Windt, 2013 |

MRI as a prediction tool for a clinical outcome after articular cartilage recovery |

|

Decary, 2017 |

Diagnostic validity of physical examination tests |

|

Duncan, 2015 |

Radiograph to detect knee arthritis |

|

Harris, 2012 |

O: only patellofemoral chondral lesions (part of knee) |

|

Hunter, 2011a |

MRI as biomarker for osteoarthritis |

|

Hunter, 2011b |

Responsiveness and reliability of MRI-based measures of osteoarthritis |

|

Puig, 2015 |

Low vs high-field MRI for detection meniscal or cruciate ligament tears |

|

Smith, 2012 |

O: patellofemoral and tibiofemoral joint (part of the knee) |

|

Potential RCTs |

|

|

Aroen, 2016 |

MRI T2 and dGEMRIC to detect early degenerative change |

|

Behairy, 2009 |

Included in the systematic review from Phelan, 2016 |

|

Blyth, 2015 |

Clinical examination tests vs MRI/arthroscopy |

|

Doria, 2010 |

Parallel imaging |

|

Eckstein, 2014 |

Imaging of bones and cartilage in clinical trials of osteoarthritis |

|

Gohil, 2014 |

Incidence MRI cyclops lesions |

|

Guermazi, 2011 |

MRI for synovitis assessment and imaging osteoarthritis |

|

Javaid, 2010 |

MRI association with incident knee symptoms: no accuracy data |

|

Joseph, 2016 |

Prediction of developing knee pain with MRI |

|

Jung, 2013 |

3D fast spin-echo, isotropic 3D balances fast field-echo, conventional 2D fast snip-echo MR imaging in evaluation of knee cartilage, ligaments, menisci, and osseous structures of the knee joint in symptomatic patients |

|

Pan, 2011 |

Frequency of degenerative knee morphologic abnormalities, using 3-T-MRI (no diagnostic value) |

|

Reed, 2013 |

Small sample size (N=16) |

|

Saarakkala, 2012 |

Diagnostic performance ultrasonography for detecting degenerative change |

|

Siddiqui, 2013 |

Clinical examination vs MRI |

|

Snoeker, 2015 |

Development clinical prediction rule |

|

Subhas, 2014 |

How frequently MRI changes diagnosis |

|

Van Dyck, 2012 |

Partial ACL tears |

|

Van Dyck, 2013 |

Included in the systematic review from Smith, 2016 |

|

Vincken, 2009 |

No diagnostic accuracy data |

|

Wittstein, 2009 |

Predict response to physical therapy |