Artroscopie bij patellofemoraal pijnsyndroom

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de waarde van artroscopie bij patellofemoraal pijnsyndroom?

Aanbeveling

Verricht geen artroscopie bij patiënten met patellofemoraal pijnsyndroom.

Wees zeer terughoudend met het verrichten van artroscopie bij patiënten met apexitis patella (Jumper’s knee) of patella tendinopathie (zie voor meer informatie de overwegingen).

Overwegingen

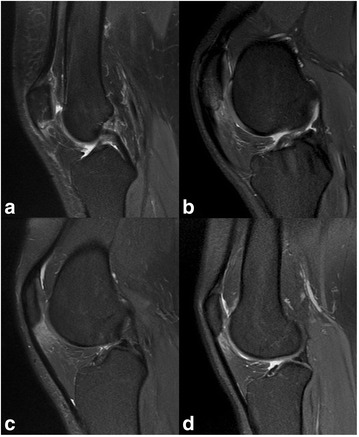

In voorgaande tekst is het wetenschappelijk bewijs voor een artroscopische behandeling voor patiënten met het patellofemoraal pijnsyndroom en voor patiënten met een apexitis patella beschreven. De gebruikte uitkomstmaten zijn VAS- en NRS-pijnscores en verschillende PROMs, uitkomstmaten die gebaseerd zijn op vragenlijsten ingevuld door patiënten. Andere waarden zoals patiëntveiligheid, beschikbaarheid en kosteneffectiviteit zijn niet onderzocht. Ten aanzien van de patiëntveiligheid geldt in algemene zin dat een operatieve behandeling meer veiligheidsrisico’s heeft en de kans op majeure complicaties (zoals heroperaties of opname in het ziekenhuis) ook groter is, dan bij een conservatieve behandeling. De werkgroep heeft geen informatie over de kosten van de verschillende behandelingen, maar het is aannemelijk dat een operatieve behandeling meer directe zorg kosten genereert. De toegankelijkheid van zorg is voor zowel de operatieve als conservatieve behandeling in Nederland waarschijnlijk voldoende, dat speelt geen rol in het advies van de werkgroep. Vanwege de lage bewijskracht van de beschreven literatuur en vanwege het veiligheids- en kostenaspect is de werkgroep van mening dat men geen scopie moet uitvoeren ter behandeling van patellofemorale pijnklachten en dat men terughoudend moet zijn met het adviseren en uitvoeren van een artroscopie ter behandeling van apexitis patella. De beschreven literatuur heeft lage bewijskracht in het voordeel van een artroscopische behandeling in de onderzochte populatie, de veiligheidsrisico’s zijn daarentegen lager bij conservatieve behandeling. De werkgroep is van mening dat men ondanks de positieve effecten op de beschreven uitkomstmaat pijn terughoudend moet zijn met het adviseren en uitvoeren van een artroscopie bij apexitis. De effecten op de andere uitkomstmaten zijn niet onderzocht en de ervaring van de werkgroep is dat de meeste patiënten goed uitkomen met conservatieve behandeling. Naar de mening van de werkgroep is een artroscopische behandeling alleen geïndiceerd bij een duidelijk anatomisch substraat, bijvoorbeeld bij een patiënt met een impingement van de onderpool van de patella met de patellapees, voor een voorbeeld van deze pathologie zie figuur 1.

Figuur 1A. botoedeem in de onderpool van de patella, B. verdikking van de patellapees, C. oedeem in de bursa infrapatellaris van Hoffa. In figuur 1A is er een vormafwijking van de patella die voor impingement klachten kan zorgen en waarbij er een relatieve indicatie bestaat voor een (artroscopische) resectie (overgenomen uit Ogon, 2017)

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

The term 'anterior knee pain' is a descriptive term that covers all the pain surrounding the patellofemoral joint. It is therefore not a diagnosis in the narrow sense, but a symptom. Other (descriptive) commonly used terms for these complaints are retropatellar chondropathy (RPC), chondromalacia patella, intern derangement of the patella or patella malalignment. These terms suggest that the anterior knee pain is caused by a cartilage impairment or a radiological abnormality. There is no evidence that there is a correlation between arthroscopically proven abnormalities and patellofemoral complaints. The advice of the international patellofemoral working group is not to use the terms (retropatellar chondropathy (RPC), chondromalacia patella, internal derangement of the knee or patella malalignment) for unexplained complaints at the front of the knee. They advise to use the descriptive term 'anterior knee pain' (Grelsamer, 2005). In Dutch this can be translated as patellofemoraal pijnsyndroom (PFPS).

Despite the high incidence, not much is known about the etiology of patellofemoral pain syndrome. The optimal treatment therefore remains controversial. The question is whether arthroscopy has a place in the treatment of patellofemoral pain syndrome. To answer this question, we evaluate different causes of patellofemoral pain syndrome.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome

Pain

|

Low GRADE |

There is no difference in the effect of arthroscopy compared with conservative therapy on level of pain in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome.

References (Kettunen, 2007; Kettunen, 2012) |

Self-reported knee function

|

Low GRADE |

There is no difference in the effect of arthroscopy compared with conservative therapy on level of function in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome.

References (Kettunen, 2007; Kettunen, 2012) |

Stability and range of motion

|

- GRADE |

The effect of arthroscopy compared with conservative therapy on stability and range of motion was not studied in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome. |

Patients with apexitis patella (Jumper’s knee) or patella tendinopathy

Pain

|

Low GRADE |

There was a positive effect of arthroscopy compared with conservative therapy on level of pain in patients with apexitis patella (Jumper’s knee) or patella tendinopathy.

References (Willberg, 2011) |

Self-reported knee function & stability and range of motion

|

- GRADE |

The effect of arthroscopy compared with conservative therapy or open surgery on level of knee function or stability and range of motion was not studied in patients with apexitis patella (Jumper’s knee) or patella tendinopathy. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome

Description of studies

Kettunen and colleagues performed an RCT to study the effects of arthroscopy in patients with chronic patellofemoral pain syndrome. The short-term results were published in a study by Kettunen (2007); the long-term results were published in a study by Kettunen (2012). Patients with Jumper’s knee, knee osteoarthritis, osteochondritis and competitive athletes were excluded from participation. In the intervention group, all patients underwent arthroscopy followed by an eight-week home exercise program. In the control group, all patients solely followed the eight-week home exercise program. The exercise program consisted of two visits to a physiotherapist. All patients were given instructions on lower-limb muscle strengthening and stretching exercises to be performed daily at home. The duration of each daily home exercise session was approximately 30 minutes. In total, 56 patients were included, 28 in the intervention group (mean age 28.4(SD 7.5) years) and 28 in the control group (mean age 28.4 (SD5.6) years). Data were collected at baseline and after nine and 24 months, and five years of follow-up. Kettunen (2007) compared baseline with nine and 24 months follow-up; Kettunen (2012) compared baseline with five years follow-up.

Results

1. Pain

Kettunen (2007) and Kettunen (2012) measured pain when descending stairs, pain when ascending stairs and pain when standing up from a sitting position via a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). The VAS ranged from 0 to 100, where a higher score indicated more pain. At nine months follow-up, Kettunen (2007) reported that pain did not differ between patients who received arthroscopy and an eight-week home exercise program compared to patients who only received an eight-week home exercise program. Mean difference in change scores between groups, corrected for baseline scores, were 0.9 (95%CI −10.1 to 11.9) for pain when descending stairs, 2.6 (95%CI −10.0 to 15.2) for pain when ascending stairs, and 4.1 (95%CI −7.0 to 15.2) for pain when standing up from a sitting position, respectively. At five years follow-up, Kettunen (2012) reported that pain did not differ between patients who received arthroscopy and an eight-week home exercise program compared to patients who received only an eight-week home exercise program. Mean difference in change scores between groups, corrected for baseline scores, were −4.3 (95%CI −16.2 to 7.5) for pain when descending stairs, −3.3 (95%CI −14.7 to 8.1) for pain when ascending stairs, and −6.1 (95%CI −16.9 to 4.6) for pain when standing up from a sitting position, respectively.

2. Self-reported knee function

Kettunen (2007) and Kettunen (2012) measured knee function by the Kujala score. The Kujala score ranged from 0 to 100, where a higher score indicated a better function. At nine and 24 months follow-up, Kettunen (2007) reported that function did not differ between patients who received arthroscopy and an eight-week home exercise program compared to patients who only received an eight-week home exercise program. Mean difference in change scores between groups, corrected for baseline scores, were 1.1 (95%CI −7.4 to 5.2) and 2.8 (95%CI -4.2 to 9.9), respectively. At five years follow-up, Kettunen (2012) reported that function did not differ between patients who received arthroscopy and an eight-week home exercise program compared to patients who only received an eight-week home exercise program. Mean difference in change scores between groups, corrected for baseline scores, was 1.2 (95%CI −8.4 to 6.1), respectively.

3. Stability and range of motion

No studies were included that reported on the effectiveness of arthroscopy compared with conservative therapy or surgery with respect to stability or range of motion in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome.

Level of evidence of the literature

There are four levels of evidence: high, moderate, low and very low. RCTs start at a high level of evidence.

Pain: The level of evidence for the outcome measure pain was downgraded by two levels due a relative small sample of patients (N=56) and risk of bias (Kettunen, 2007; Kettunen, 2012). Risk of bias was suspected due to insufficient blinding of the participants, care providers and outcome assessors and due to differences in loss to follow-up between the intervention and control group.

Self-reported knee function: The level of evidence for the outcome measure knee function was downgraded by two levels due a relative small sample of patients (N=56) and risk of bias (Kettunen, 2007; Kettunen, 2012). Risk of bias was suspected due to insufficient blinding of the participants, care providers and outcome assessors and due to differences in loss to follow-up between the intervention and control group.

Stability and range of motion: The level of evidence for the outcome measure stability and range of motion was not evaluated as there were no studies that assessed this outcome in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome.

Patients with apexitis patella (Jumper’s knee) or patella tendinopathy

Description of included studies

Willberg (2011) performed an RCT to study the effectiveness of arthroscopic shaving with sclerosing injections in patients with chronic painful patellar tendon pain (Jumper’s knee). The study included athletes ranging from recreational to competitive level. In the intervention group, all patients underwent ultrasound and colour Doppler-guided arthroscopic shaving. In the control group, all patients underwent ultrasound and colour Doppler-guided sclerosing polidocanol injections (10 mg/ml). In total, 45 participants were included of whom N=52 patellar tendons were studied: 26 tendons in the intervention group (mean age 26.6 (SD 7.6) years) and 26 tendons in the control group (mean age 27.0 (SD 7.6) years). Data were collected at baseline and after mean 12.9 (SD 7.8) months follow-up in the intervention group and mean 13.7 (SD 6.9) months follow-up in the control group.

Results

1. Pain

Willberg (2011) measured pain at rest and pain at sport activity via a VAS. The VAS ranged from 0 to 100, where a higher score indicated more pain. Willberg (2011) reported that pain during follow-up was lower in patients who had received arthroscopic shaving compared to patients who had received sclerosing injections. For pain at rest, mean score was 5.0 (SD 8.3) in the intervention group compared to 19.2 (SD 23.2) in the control group. For pain at activity, mean score was 12.8 (SD 19.3) in the intervention group compared to 41.1 (SD 28.5) in the control group.

2. Self-reported knee function

Willberg (2011) did not report on the effectiveness of arthroscopy compared with conservative therapy with respect to knee function in patients with apexitis patella (Jumper’s knee) or patella tendinopathy.

3. Stability and range of motion

Willberg (2011) measured the PROM ‘self-reported satisfaction with treatment result’ via a VAS. The VAS ranged from 0 to 100, where a higher score indicated higher levels of satisfaction. Willberg (2011) reported that ‘self-reported satisfaction with treatment result’ during follow-up was higher in patients who had received arthroscopic shaving compared to patients who had received sclerosing injections. The mean score was 86.8 (SD 20.8) in the intervention group, compared to 52.9 (SD 32.6) in the control group.

Level of evidence of the literature

There are four levels of evidence: high, moderate, low and very low. RCTs start at a high level of evidence.

Pain: The level of evidence for the outcome measure pain was downgraded by two levels due a relative small sample of patients (N=45) and risk of bias (Willberg, 2011). Risk of bias was suspected due to insufficient blinding of the participants, care providers and outcome assessors. In addition, it was not specified whether an intention-to-treat analysis was performed.

Self-reported knee function: The level of evidence for the outcome measure function was not evaluated as there were no studies that assessed this outcome in patients with apexitis patella (Jumper’s knee) or patella tendinopathy.

Stability and range of motion: The level of evidence for the outcome measure stability and range of motion was not evaluated as there were no studies that assessed this outcome in patients with apexitis patella (Jumper’s knee) or patella tendinopathy.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the beneficial and harmful effects of arthroscopy compared with conservative treatment or open surgery in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome, apexitis patella (Jumper’s knee) or patella tendinopathy?

PICO 1

P: patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome;

I: arthroscopy;

C: conservative treatment or open surgery;

O: pain (VAS, NRS), self-reported knee function (Kujala, KOOS, IKDC (subjective), BANFF, Norwich score), IKDC (objective), stability and range of motion.

PICO 2

P: patients with apexitis patella (Jumper’s knee) or patella tendinopathy;

I: arthroscopy;

C: conservative treatment or open surgery;

O: pain (VAS, NRS), self-reported knee function (Kujala, KOOS, IKDC (subjective), BANFF, Norwich score), IKDC (objective), stability and range of motion.

Relevant outcome measures

The working group considered pain a critical outcome measure for decision making and self-reported knee function an important outcome measure for decision making.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms. For the update, the databases were searched from the previous search date 2009 till 2017 The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The updated systematic literature search resulted in 221 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared arthroscopy with conservative treatment or open surgery in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome, apexitis patella (Jumper’s knee) or patella tendinopathy. One or more of the following outcomes had to be studied: pain, self-reported knee function and stability and range of motion. Self-reported knee function had to have been measured with either the KOOS, Kujala or IKDC questionnaire. In addition, studies with patients aged ≥16 years were eligible for inclusion.

Twenty-six studies were initially selected based on title and abstract. After reading the full text, twenty-four studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and two studies were included. Based on hand search of the reference list of one of the included studies, one additional study was included. In the previous version of this guideline, one systematic review was included (Lattermann, 2006). This systematic review contained one RCT, which was not eligible for inclusion in the current literature analysis as patients <16 years were included. Therefore, in total, three studies were included in the literature analysis. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

New versus old (2010)

The literature described in the 2010 guideline concerned background information on the etiology and incidence of anterior knee pain. Also, a review from Lattermann (2006) was described. The authors of this review included mainly observational studies and an RCT. The population in this RCT also partly concerned children and adolescents. Since this population is not considered in this guideline, this RCT is not eligible and will no longer be described.

Referenties

- Kettunen JA, Harilainen A, Sandelin J, et al. Knee arthroscopy and exercise versus exercise only for chronic patellofemoral pain syndrome: 5-year follow-up. BJSM online. 2012;46(4):243-6.

- Kettunen JA, Harilainen A, Sandelin J, et al. Knee arthroscopy and exercise versus exercise only for chronic patellofemoral pain syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 2007;5:38. PubMed PMID: 18078506; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2249589.

- Lattermann C, Drake GN, Spellman J, et al. Lateral retinacular release for anterior knee pain: a systematic review of the literature. J.Knee.Surg. 2006;19:278-284.

- Ogon P, Izadpanah K, Eberbach H, et al. Prognostic value of MRI in arthroscopic treatment of chronic patellar tendinopathy: a prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):146. doi:10.1186/s12891-017-1508-2. PubMed PMID: 28376759; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5381145.

- Willberg L, Sunding K, Forssblad M, et al. Sclerosing polidocanol injections or arthroscopic shaving to treat patellar tendinopathy/jumper's knee? A randomised controlled study. BJSM online. 2011;45(5):411-5.

Evidence tabellen

Research question: What are the beneficial and harmful effects of arthroscopy compared with conservative treatment or open surgery in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome, apexitis patella (Jumper’s knee) or patella tendinopathy?

Abbreviations: ANCOVA: Analysis of Covariance; CI: Confidence Interval; PFPS: PatelloFemoral Pain Syndrome; RCT: Randomized Controlled Trial; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale.

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures.

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors ((potential) confounders).

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls.

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders.

Research question: What are the beneficial and harmful effects of arthroscopy compared with conservative treatment or open surgery in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome, apexitis patella (Jumper’s knee) or patella tendinopathy?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Kettunen ( 2007) |

The randomisation process was carried out using a computer-generated randomization list stratified by gender. |

Unlikely, sealed and sequentially numbered envelopes containing information on the treatment group were prepared and given to the assisting nurse, who opened the envelopes in numerical order after recruitment so that concealment of allocation was successful in all cases. |

Likely, patients were not blinded to the treatment allocation. Patients either received arthroscopic surgery and exercise program, or solely an exercise program. |

Likely, care providers were not blinded to the treatment allocation. Arthroscopy was performed by two co-authors of the paper, who were presumably aware of study design. . |

Unclear, it is not reported whether the outcome assessor was blinded. The data collector was not blinded to the patient’s allocation status. |

Unclear, without reasons, the results from the secondary outcome (VAS pain scale) were not reported. |

Likely, loss to follow-up at 9 months differed between the intervention and control group. In the intervention group, 3.6% people were lost to follow-up, due to refusal to continue study after arthroscopy. Loss to follow-up in the control group was three times as high (10.7%), but seemed to be for reasons unrelated to the study (lack of interest, moved abroad). At 24 months, loss to follow-up was equal in the intervention (7.1%) and control group (7.1%), but for reasons unknown. Likely, loss to follow-up was twice as high in the control group (28%) than intervention group (14%). |

Unlikely, all data were analysed as intention-to-treat. |

|

Willberg (2011) |

Patient selected an opaque envelope containing treatment allocation for an independent assistant. It was unclear whether the envelopes were arranged in a random order. |

Unlikely, patients selected an opaque envelope containing treatment allocation. |

Likely. patients were not blinded to the treatment allocation. Patients either received arthroscopic surgery or sclerosing injections. |

Unclear, it was not reported whether care providers were blinded to the treatment allocation. Presumably, this was not the case. |

Unclear, it is not reported whether the outcome assessor was blinded. The data collector was blinded to the patient’s allocation status. |

Unclear, all predefined outcomes were reported but it is unclear to which assessment the outcomes refer as there were multiple follow-up measurements and only one ‘follow-up outcome’. |

Unlikely, loss to follow-up was minimal and equal in the intervention (2.2%) and intervention group (2.2%). |

Unclear, intention-to-treat or per-protocol analysis was not specified. |

- Randomisation: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomisation process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomisation (performed at a site remote from trial location) or sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomisation procedures or open allocation schedules.

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments. The outcome assessor records the study results. Blinding of those assessing outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignement influences the proces of outcome assessment (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available, then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, then outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups, bias is likely. If the number of patients lost to follow-up, or the reasons why, are not reported, the risk of bias is unclear.

- Participants included in the analysis are exactly those who were randomized into the trial. If the numbers randomized into each intervention group are not clearly reported, the risk of bias is unclear; an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 04-03-2019

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 04-03-2019

Voor het beoordelen van de actualiteit van deze richtlijn is de werkgroep wel in stand gehouden. Uiterlijk in 2024 bepaalt het bestuur van de NOV of de modules van deze richtlijn nog actueel zijn. Op modulair niveau is een onderhoudsplan beschreven. Bij het opstellen van de richtlijn heeft de werkgroep per module een inschatting gemaakt over de maximale termijn waarop herbeoordeling moet plaatsvinden en eventuele aandachtspunten geformuleerd die van belang zijn bij een toekomstige herziening (update). De geldigheid van de richtlijn komt eerder te vervallen indien nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding zijn een herzieningstraject te starten.

De NOV is regiehouder van deze module en eerstverantwoordelijke op het gebied van de actualiteitsbeoordeling van de richtlijn. De andere aan deze richtlijn deelnemende wetenschappelijke verenigingen of gebruikers van de richtlijn delen de verantwoordelijkheid en informeren de regiehouder over relevante ontwikkelingen binnen hun vakgebied.

|

Module1 |

Regiehouder(s)2 |

Jaar van autorisatie |

Eerstvolgende beoordeling actualiteit richtlijn3 |

Frequentie van beoordeling op actualiteit4 |

Wie houdt er toezicht op actualiteit5 |

Relevante factoren voor wijzigingen in aanbeveling6 |

|

Submodule: Artroscopie bij patellofemoraal pijnsyndroom |

NOV |

2019 |

2024 |

Eens in 5 jaar |

NOV |

- |

1 Naam van de module

2 Regiehouder van de module (deze kan verschillen per module en kan ook verdeeld zijn over meerdere regiehouders)

3 Maximaal na vijf jaar

4 (half)Jaarlijks, eens in twee jaar, eens in vijf jaar

5 Regievoerende vereniging, gedeelde regievoerende verenigingen, of (multidisciplinaire) werkgroep die in stand blijft

6 Lopend onderzoek, wijzigingen in vergoeding/organisatie, beschikbaarheid nieuwe middelen

Algemene gegevens

De richtlijnontwikkeling werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.kennisinstituut.nl) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

Doel en doelgroep

Doel

Deze richtlijn beoogt uniform beleid ten aanzien van de zorg bij patiënten met knieletsels die mogelijk behandeld kunnen worden met een artroscopische ingreep.

Doelgroep

Deze richtlijn is geschreven voor alle leden van de beroepsgroepen van orthopaedisch chirurgen, sportartsen, fysiotherapeuten, radiologen en traumachirurgen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met (acute) knieletsels. Daarnaast is deze richtlijn bedoeld om zorgverleners die anderzijds betrokken zijn bij deze patiënten, te informeren, waaronder kinderartsen, revalidatieartsen, huisartsen, physician assistants en verpleegkundig specialisten.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijn is in 2016 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met (acute) knieletsels te maken hebben. De werkgroepleden zijn door hun beroepsverenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname. De werkgroep is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze richtlijn.

- Dr. E.R.A. (Ewoud) van Arkel, orthopedisch chirurg, werkzaam in het Haaglanden Medisch Centrum te Den Haag, NOV, voorzitter

- Drs. A. (Bert) van Essen, sportarts, werkzaam bij het Maxima Medisch Centrum te Veldhoven, VSG

- Dr. S. (Sander) Koëter, orthopedisch chirurg, werkzaam in het Canisius Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis te Nijmegen, NOV

- Drs. N. (Nicky) van Melick, sportfysiotherapeut en bewegingswetenschapper, werkzaam bij het Knie Expertise Centrum te Eindhoven, KNGF

- Dr. P.C. (Paul) Rijk, orthopedisch chirurg, werkzaam in het Medisch Centrum Leeuwarden te Leeuwarden, NOV

- Drs. M.J.M. (Michiel) Segers, traumachirurg, werkzaam in het Sint Antonius Ziekenhuis te Utrecht, NVvH

- Dr. T.G. (Tony) van Tienen, orthopedisch chirurg, werkzaam in de kliniek Via Sana te Mill, NOV

- Dr. P.W.J. (Patrice) Vincken, radioloog, werkzaam bij Alrijne Zorggroep te Leiderdorp, NVvR

Meelezers:

- Patiëntenfederatie Nederland te Utrecht

Met ondersteuning van:

- Dr. B.H. (Bernardine) Stegeman, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. J. (Janneke) Hoogervorst-Schilp, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De KNMG-Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of ze in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatie management, kennisvalorisatie) hebben gehad. Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Arkel, van (voorzitter) |

Orthopaedisch chirurg |

Opleider orthopedie Haaglanden Medisch Centrum |

- |

Geen actie |

|

Essen, van |

Sportarts |

Medisch directeur SMC |

- |

Geen actie |

|

Tienen, van |

Orthopaedisch chirurg |

|

- |

Geen actie (meniscusimplantaten en knieprotheses vallen buiten de afbakening van de richtlijn) |

|

Melick |

Sportfysiotherapeut |

|

- |

Geen actie (valt buiten de afbakening van de richtlijn) |

|

Rijk |

Orthopaedisch chirurg |

- |

- |

Geen actie |

|

Vincken |

Radioloog |

- |

- |

Geen actie |

|

Segers |

Traumachirurg |

Consultant voor DePuy Synthes Trauma |

- |

Geen actie (producten geproduceerd door DePuy Synthes Trauma vallen buiten de afbakening van de richtlijn) |

|

Koëter |

Orthopaedisch chirurg |

Hoofd research support office CWZ |

- |

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door een meelezer vanuit de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland. Tijdens de oriënterende zoekactie werd gezocht op literatuur naar patiëntenperspectief (zie Strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur). De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

In de verschillende fasen van de richtlijnontwikkeling is rekening gehouden met de implementatie van de richtlijn (module) en de praktische uitvoerbaarheid van de aanbevelingen. Daarbij is uitdrukkelijk gelet op factoren die de invoering van de richtlijn in de praktijk kunnen bevorderen of belemmeren. Het implementatieplan is te vinden bij de aanverwante producten.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijn is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010), dat een internationaal breed geaccepteerd instrument is. Voor een stap-voor-stap beschrijving hoe een evidence-based richtlijn tot stand komt wordt verwezen naar het stappenplan Ontwikkeling van Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Knelpuntenanalyse

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerden de voorzitter van de werkgroep en de adviseur de knelpunten. De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbevelingen uit de eerdere richtlijn (NOV, 2010) op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door een Invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten. De werkgroep stelde vervolgens een long list met knelpunten op en prioriteerde de knelpunten op basis van: (1) klinische relevantie; (2) de beschikbaarheid van (nieuwe) evidence van hoge kwaliteit; (3) en de te verwachten impact op de kwaliteit van zorg, patiëntveiligheid en (macro)kosten.

Uitgangsvragen en uitkomstmaten

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de voorzitter en de adviseur concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld. Deze zijn met de werkgroep besproken waarna de werkgroep de definitieve uitgangsvragen heeft vastgesteld. Vervolgens inventariseerde de werkgroep per uitgangsvraag welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als kritiek, belangrijk (maar niet kritiek) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de kritieke uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur

Er werd eerst oriënterend gezocht naar bestaande buitenlandse richtlijnen (via Medline (OVID), GIN en NICE), systematische reviews (via Medline, en literatuur over patiëntenvoorkeuren en patiëntrelevante uitkomstmaten (patiëntenperspectief; Medline (OVID)). Vervolgens werd voor de afzonderlijke uitgangsvragen aan de hand van specifieke zoektermen gezocht naar gepubliceerde wetenschappelijke studies in (verschillende) elektronische databases. Tevens werd aanvullend gezocht naar studies aan de hand van de literatuurlijsten van de geselecteerde artikelen. In eerste instantie werd gezocht naar studies met de hoogste mate van bewijs. De werkgroepleden selecteerden de via de zoekactie gevonden artikelen op basis van vooraf opgestelde selectiecriteria. De geselecteerde artikelen werden gebruikt om de uitgangsvraag te beantwoorden. De databases waarin is gezocht, de zoekstrategie en de gehanteerde selectiecriteria zijn te vinden in de module met desbetreffende uitgangsvraag. De zoekstrategie voor de oriënterende zoekactie en patiëntenperspectief zijn opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Kwaliteitsbeoordeling individuele studies

Individuele studies werden systematisch beoordeeld, op basis van op voorhand opgestelde methodologische kwaliteitscriteria, om zo het risico op vertekende studieresultaten (risk of bias) te kunnen inschatten. Deze beoordelingen kunt u vinden in de Risk of Bias (RoB) tabellen. De gebruikte RoB instrumenten zijn gevalideerde instrumenten die worden aanbevolen door de Cochrane Collaboration: AMSTAR – voor systematische reviews; Cochrane – voor gerandomiseerd gecontroleerd onderzoek; Newcastle-Ottawa – voor observationeel onderzoek; QUADAS II – voor diagnostisch onderzoek.

Samenvatten van de literatuur

De relevante onderzoeksgegevens van alle geselecteerde artikelen werden overzichtelijk weergegeven in evidence-tabellen. De belangrijkste bevindingen uit de literatuur werden beschreven in de samenvatting van de literatuur. Bij een voldoende aantal studies en overeenkomstigheid (homogeniteit) tussen de studies werden de gegevens ook kwantitatief samengevat (meta-analyse) met behulp van Review Manager 5.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

A) Voor interventievragen (vragen over therapie of screening)

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie (Schünemann, 2013).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

B) Voor vragen over diagnostische tests, schade of bijwerkingen, etiologie en prognose

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd eveneens bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode: GRADE-diagnostiek voor diagnostische vragen (Schünemann, 2008), en een generieke GRADE-methode voor vragen over schade of bijwerkingen, etiologie en prognose. In de gehanteerde generieke GRADE-methode werden de basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek toegepast: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van bewijskracht op basis van de vijf GRADE-criteria (startpunt hoog; downgraden voor risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias).

Formuleren van de conclusies

Voor elke relevante uitkomstmaat werd het wetenschappelijk bewijs samengevat in een of meerdere literatuurconclusies waarbij het niveau van bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methodiek. De werkgroepleden maakten de balans op van elke interventie (overall conclusie). Bij het opmaken van de balans werden de gunstige en ongunstige effecten voor de patiënt afgewogen. De overall bewijskracht wordt bepaald door de laagste bewijskracht gevonden bij een van de kritieke uitkomstmaten. Bij complexe besluitvorming waarin naast de conclusies uit de systematische literatuuranalyse vele aanvullende argumenten (overwegingen) een rol spelen, werd afgezien van een overall conclusie. In dat geval werden de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de interventies samen met alle aanvullende argumenten gewogen onder het kopje Overwegingen.

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals de expertise van de werkgroepleden, de waarden en voorkeuren van de patiënt (patient values and preferences), kosten, beschikbaarheid van voorzieningen en organisatorische zaken. Deze aspecten worden, voor zover geen onderdeel van de literatuursamenvatting, vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje Overwegingen.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk. De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen.

Randvoorwaarden (Organisatie van zorg)

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijn is expliciet rekening gehouden met de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, menskracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van een specifieke uitgangsvraag maken onderdeel uit van de overwegingen bij de bewuste uitgangsvraag. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg rond artroscopie knie.

Kennislacunes

Tijdens de ontwikkeling van deze richtlijn is systematisch gezocht naar onderzoek waarvan de resultaten bijdragen aan een antwoord op de uitgangsvragen. Bij elke uitgangsvraag is door de werkgroep nagegaan of er (aanvullend) wetenschappelijk onderzoek gewenst is om de uitgangsvraag te kunnen beantwoorden. Een overzicht van de onderwerpen waarvoor (aanvullend) wetenschappelijk van belang wordt geacht, is als aanbeveling in de Kennislacunes beschreven (onder aanverwante producten).

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijn werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijn aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijn werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0. Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site.html. 2012.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ. 2008;336(7653):1106-10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39500.677199.AE. Erratum in: BMJ. 2008;336(7654). doi: 10.1136/bmj.a139. PubMed PMID: 18483053.

Ontwikkeling van Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen: stappenplan. Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten.

Zoekverantwoording

|

Database |

Zoektermen |

Totaal |

|

Medline (OVID)

2009-sept. 2017

SRs Vanaf 2012-sept. 2017 |

1 Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome/ or (Patella/ and Tendinopathy/) (845) 2 ("Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome*" or PTFP or (medial adj3 plica*) or "anterior knee pain" or AKP or (patellar adj3 tendin*) or (jumper* adj3 knee*)).ti,ab,kf. (3354) 3 1 or 2 (3704) 4 exp Orthopedic Procedures/ or exp Surgical Procedures, Operative/ or exp Minimally Invasive Surgical Procedures/ or exp Minor Surgical Procedures/ or Arthroscopy/ or (arthroscop* or releas* or resect*).ti,ab,kf. (3731803) 5 3 and 4 (1243) 6 "Lateral retinacular release for anterior knee pain: a systematic review of the literature.".m_titl. (1) 7 5 and 6 (1) 8 exp Orthopedic Procedures/ or exp Surgical Procedures, Operative/ or exp Minimally Invasive Surgical Procedures/ or exp Minor Surgical Procedures/ or Arthroscopy/ or (arthroscop* or releas* or resect*).ti,ab,kf. or surgery.fs. (4266223) 9 3 and 8 (1379) 10 limit 9 to (english language and yr="2009 -Current") (607) 11 limit 9 to ed=20090101-20170906 (667) 12 10 or 11 (700) 13 limit 12 to english language (629) 14 (meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (meta adj analy$).tw. or ((systematic* or literature) adj2 review$1).tw. or (systematic adj overview$1).tw. or exp "Review Literature as Topic"/ or cochrane.ab. or cochrane.jw. or embase.ab. or medline.ab. or (psychlit or psyclit).ab. or (cinahl or cinhal).ab. or cancerlit.ab. or ((selection criteria or data extraction).ab. and "review"/)) not (Comment/ or Editorial/ or Letter/ or (animals/ not humans/)) (344802) 15 13 and 14 (70) 16 limit 15 to yr="2012 -Current" (51) – 47 uniek 17 (exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or clinic$ trial$1.tw. or (clinic$ adj trial$1).tw. or ((singl$ or doubl$ or treb$ or tripl$) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo$.tw. or randomly allocated.tw. or (allocated adj2 random$).tw.) not (animals/ not humans/) (1410883) 18 13 and 17 (112) 19 18 not 16 (92) – 87 uniek

|

221 |

|

Embase (Elsevier) |

(((('patellofemoral pain syndrome'/exp OR 'patellar tendinopathy'/exp OR ('patella'/exp/mj AND 'tendinitis'/mj)) OR ('patellofemoral pain syndrome*':ti,ab OR ptfp:ti,ab OR ((medial NEAR/3 plica*):ti,ab) OR 'anterior knee pain':ti,ab OR akp:ti,ab OR ((patellar NEAR/3 tendin*):ti,ab) OR ((jumper* NEAR/3 knee*):ti,ab)))

AND ('orthopedic surgery'/exp/mj OR 'surgery'/exp/mj OR 'minimally invasive surgery'/exp/mj OR 'minor surgery'/exp OR 'arthroscopy'/exp/mj OR arthroscop*:ab,ti OR releas*:ti,ab OR resect*:ti,ab OR surgery:lnk)

NOT 'conference abstract':it AND (english)/lim AND (embase)/lim AND (1-1-2009)/sd NOT (7-9-2017)/sd)

(('meta analysis'/de OR cochrane:ab OR embase:ab OR psycinfo:ab OR cinahl:ab OR medline:ab OR ((systematic NEAR/1 (review OR overview)):ab,ti) OR ((meta NEAR/1 analy*):ab,ti) OR metaanalys*:ab,ti OR 'data extraction':ab OR cochrane:jt OR 'systematic review'/de) NOT (('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp)) AND (2012-2017)/py) (37) – 12 uniek

AND (('clinical trial'/exp OR 'randomization'/exp OR 'single blind procedure'/exp OR 'double blind procedure'/exp OR 'crossover procedure'/exp OR 'placebo'/exp OR 'prospective study'/exp OR rct:ab,ti OR random*:ab,ti OR 'single blind':ab,ti OR 'randomised controlled trial':ab,ti OR 'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR placebo*:ab,ti) NOT 'conference abstract':it)) (111) – 75 uniek |

Tabel Exclusie na het lezen van het volledige artikel

|

Atuhor and year |

Reasons for exclusion |

|

Ackermann, 2012 |

Narrative review |

|

Brockmeyer, 2015 |

Review: searched one database only; no risk of bias assessment; solely included case series on arthroscopy |

|

Cucurulo, 2009 |

Cohort study; not randomized |

|

Everhart, 2017 |

Review: no risk of bias assessment; no RCTs included |

|

Gaida, 2011 |

Review: 1 RCT relevant; already included |

|

Genin, 2017 |

Review: no risk of bias assessment; no RCTs included |

|

Hoksrud, 2011 |

Case series |

|

Kaux, 2013 |

Review: no risk of bias assessment |

|

Larsson, 2012 |

Review: no RCTs included on arthroscopy |

|

Lubowitz, 2016 |

Commentary |

|

Macmuil, 2012 |

Compares implementation methods, all patients received surgery |

|

Marcheggiani, 2013 |

Review: 1 RCT included that studied open surgery |

|

Rodriguez-Merchan, 2013 |

Review: searched one database |

|

Rooney, 2015 |

Review: no RCTs included; majority were case series |

|

Schindler, 2014 |

Narrative review |

|

Skjong, 2012 |

Narrative review; no risk of bias assessment |

|

Sunding, 2015 |

Original study included |