Herstarten antistollingstherapie na bloeding

Uitgangsvraag

Hoe moeten we omgaan met het herstarten van antistollingstherapie na een bloeding?

Aanbeveling

Maak voor elke patiënt die een intracraniële of ernstige gastro-intestinale bloeding heeft doorgemaakt een afweging tussen enerzijds het risico op een arteriële of veneuze trombose en anderzijds het risico op een nieuwe bloeding bij het hervatten van de antistollingsbehandeling. Deze beslissing wordt bij voorkeur in een multidisciplinair overleg genomen en in samenspraak met de (naaste van de) patiënt en de behandelend specialist. Houd hierbij rekening met de ernst, de locatie, de onderliggende oorzaak en de behandeling van de bloeding alsook met de hoogte van het trombotisch risico.

Overweeg de antistollingstherapie niet te snel te hervatten:

- twee weken na een ernstige gastro-intestinale bloeding;

- één tot tien weken na een intracraniële bloeding.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Op basis van de geïncludeerde studies is het effect onzeker van het herstarten van de antistollingsbehandeling bij patiënten die een gastro-intestinale of intracraniële bloeding hadden tijdens het gebruik van antistollingsmiddelen, op de cruciale uitkomsten mortaliteit en recidief bloeding. Dit geldt ook voor de patiënten die een traumatisch hoofdletsel opliepen tijdens het gebruik van antistollingsmiddelen. Voor deze groep patiënten waren er geen data beschikbaar met betrekking tot de cruciale uitkomstmaat mortaliteit.

Ook voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaat trombo-embolische events geldt dat er grote onzekerheid bestaat over het effect van het herstarten van antistollingsbehandeling bij patiënten die een gastro-intestinale bloeding, intracraniële bloeding of traumatisch hoofdletsel hadden tijdens het gebruik van antistollingsmiddelen. De overall bewijskracht voor deze module is dan ook zeer laag en er is duidelijk sprake van een kennisvraag.

Er is geen bewijs uit gerandomiseerde fase-3 klinische trials met betrekking tot de vraag of en wanneer orale antistollingsmiddelen hervat dienen te worden bij patiënten die een gastro-intestinale bloeding, intracraniële bloeding, of traumatisch hersenletsel hebben doorgemaakt en een blijvende indicatie voor deze medicatie hebben. In een fase-2 gerandomiseerde studie werden patiënten met atriumfibrilleren die een antistolling gerelateerde hersenbloeding door hadden gemaakt (N=101) gerandomiseerd voor herstart van de antistolling (apixaban) of vermijden van antistolling (plaatjesremming of geen antitrombotica) (Schreuder, 2021). In totaal werd er voor 13/50 (26%) patiënten in de groep die antistolling ontving, een niet-fatale beroerte of cardiovasculaire dood gerapporteerd, ten opzichte van 12/51 (24%) van de patiënten in de groep waarbij geen antistolling werd herstart. De conclusie is dat patiënten met een antistolling gerelateerde hersenbloeding een hoog risico hebben op een niet-fatale beroerte dan wel vasculaire dood, ongeacht het al dan niet starten van antistolling.

In een andere gerandomiseerde non-inferiority pilotstudie werden patiënten met een hersenbloeding en AF en een CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥2 geïncludeerd (N=203; Salman, 2021). 16% van de patiënten gebruikte geen antistolling ten tijde van de hersenbloeding. In deze studie werd het effect van het starten van orale antistolling vergeleken met het effect van plaatjesremmers of geen antitrombotica. In totaal kregen 8/101 (8%) patiënten in de groep waarbij de antistolling gestart werd opnieuw een intracraniële bloeding ten opzichte van 4/102 (4%) van de patiënten in de groep waarbij er geen orale antistolling werd gestart. In de groep waarbij orale antistolling werd gestart overleden 22/101 (22%) van de patiënten, ten opzichte van 11 (11%) in de controlegroep. De auteurs concluderen dat het onzeker is of het starten van orale antistolling niet-inferieur is aan het niet starten van orale antistolling na een doorgemaakte hersenbloeding.

Het kantelpunt van voor- en nadelen is op basis van de beschikbare literatuur niet aan te wijzen. De belangrijkste vraag die uit de cohortstudies naar voren komt is of herstart van antistolling inderdaad de mortaliteit verlaagt, of dat dit een artefact is dat voortkomt uit selectie (confounding by (contra-) indication) van patiënten in de observationele studies. Hierop kan nu geen antwoord worden gegeven.

Gastro-intestinale bloeding

Patiënten met een ernstige gastro-intestinale bloeding hebben een aanzienlijk risico op trombose als niet met antistolling wordt herstart, bijvoorbeeld patiënten die antistollingsmiddelen gebruiken in verband met een mitraliskunstklep. Voor deze uitkomstmaat geldt dat, als er selectiebias is, dan het aantal patiënten met een trombose zou zijn onderschat. Het risico op bloedingen lijkt vooral groot als er snel (binnen een week, voor ontslag) wordt herstart met antistolling en de oorzaak van de bloeding niet adequaat kon worden gevonden en aangepakt. Het lijkt in deze situatie dus reëel om, als er een aanhoudende indicatie is voor antistolling, wel te herstarten maar daarmee wat langer te wachten. Er is geen onderbouwing voor welke termijn moet worden gekozen, maar in de praktijk lijkt twee weken redelijk. Hierbij dient rekening gehouden te worden met de ernst, locatie en behandeling van de bloeding, alsook met de hoogte van het trombotisch risico. In het geval dat de oorzaak van de bloeding wel kon worden opgespoord en aangepakt, zoals bijvoorbeeld bij een bloedend ulcus duodeni, kan bij voldoende hemostase eerder worden herstart met antistollingsmedicatie.

Intracraniële bloeding

Voor de verdere interpretatie van de gegevens in deze module is het relevant om het verschil te benadrukken tussen enerzijds intracraniële bloedingen (traumatische subdurale/epidurale bloedingen, traumatische subarachnoïdale bloedingen en contusiehaarden) en de spontane intracerebrale bloedingen anderzijds. Dit omdat het risico op herhaling van een intracraniële bloeding kleiner is dan bij een spontane intracerebrale bloeding. In het geval van een spontane intracerebrale bloeding is het van groot belang om de onderliggende oorzaak vast te stellen.

In de richtlijn van de European Heart Rhythm Association uit 2021 wordt geen harde aanbeveling gedaan over het wel of niet herstarten van antistolling na een intracraniële bloeding, noch over de eventuele timing hiervan (Steffel, 2021). Per patiënt dient een individuele afweging gemaakt te worden, bij voorkeur in multidisciplinair verband. Factoren die meegewogen kunnen worden bij de beslissing tot herstarten zijn onder andere of er een behandelbare oorzaak van de bloeding is, de aanwezigheid van cerebrale microbloedingen, de ernst van de intracraniële bloeding, de leeftijd van de patiënt, alcoholmisbruik en de aanwezigheid van ongecontroleerde hypertensie. Indien besloten wordt tot herstart van antistolling, dan kan een periode van 4-8 weken na het optreden van de bloeding worden aangehouden (Steffel, 2021).

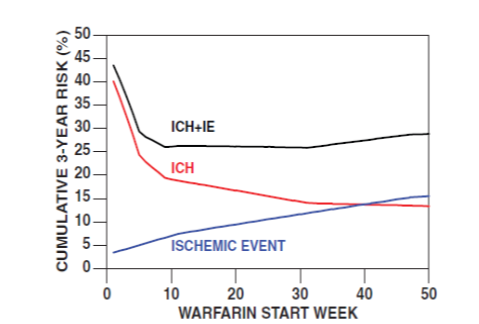

Majeed (2010) concluderen dat herstarten na 10 tot 30 weken vanaf de intracraniële bloeding optimaal lijkt op basis van het gecombineerde cumulatieve risico op bloedingen of ischemische events voor een behandelhorizon van drie jaar. Dit is veel later dan in Nederland gebruikelijk is.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Bij de beslissing tot wel of niet herstarten van de antistollingsbehandeling is het van belang om de wens van de patiënt mee te nemen. Bespreek met patiënt het gebrek aan wetenschappelijk bewijs en de potentiële voor- en nadelen van de verschillende strategieën. Het belangrijkste potentiële voordeel van het herstarten van de antistolling is het voorkomen van trombo-embolische complicaties. Het belangrijkste potentiële nadeel is het opnieuw optreden van een bloedingscomplicatie.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Kosten spelen geen rol in de afweging om antistolling al dan niet te herstarten bij patiënten die antistolling gebruikten en een bloeding kregen.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Overwegingen omtrent aanvaarbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie spelen geen rol bij de huidige aanbeveling.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Het belangrijkste voordeel van het herstarten van antistolling is een afname van het risico op een trombo-embolisch event. Het belangrijkste nadeel is een verhoging van het risico op een nieuwe bloeding. Omdat data uit gerandomiseerde studies (fase 3-trials van voldoende omvang) ontbreken, is er een zwakke aanbeveling geformuleerd.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

It is a dilemma if and when to restart anticoagulation treatment in patients with anticoagulation-associated bleeding (i.e. intracranial, gastro-intestinal, other). The risks of both recurrent bleeding and a thromboembolic event must be considered. Especially in the absence of clear (contra-) indications, the decision depends on various patient-related factors.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Part I: Gastro-intestinal bleedings

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of restarting anticoagulation therapy on mortality when compared with no restarting anticoagulation therapy in patients with an anticoagulation associated gastro-intestinal bleeding.

Sources: Witt, 2012; Sengupta, 2015; Qureshi, 2014 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of restarting anticoagulation therapy on rebleeding when compared with no restarting anticoagulation therapy in patients with an anticoagulation associated gastro-intestinal bleeding.

Sources: Witt, 2012; Sengupta, 2015; Qureshi, 2014 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of restarting anticoagulation therapy on thromboembolic events when compared with no restarting anticoagulation therapy in patients with an anticoagulation associated gastro-intestinal bleeding.

Sources: Witt, 2012; Sengupta, 2015; Qureshi, 2014 |

Part II: Intracranial bleeding

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of restarting anticoagulation therapy on mortality when compared with no restarting anticoagulation therapy in patients with an anticoagulation associated intracranial bleeding.

Source: Yung, 2012 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of restarting anticoagulation therapy on rebleeding when compared with no restarting anticoagulation therapy in patients with an anticoagulation associated intracranial bleeding.

Sources: Majeed, 2010; Yung, 2012 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of restarting anticoagulation therapy on thromboembolic events when compared with no restarting anticoagulation therapy in patients with an anticoagulation associated intracranial bleeding.

Sources: Majeed, 2010; Yung, 2012; Gathier, 2013 |

Part III: Traumatic brain injury (TBI)

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of restarting anticoagulation therapy on mortality when compared with no restarting anticoagulation therapy in patients using anticoagulation therapy with traumatic brain injury.

|

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of restarting anticoagulation therapy on rebleeding when compared with no restarting anticoagulation therapy in patients using anticoagulation therapy with traumatic brain injury.

Source: Albrecht, 2014 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of restarting anticoagulation therapy on thromboembolic events when compared with no restarting anticoagulation therapy in patients using anticoagulation therapy with traumatic brain injury.

Source: Albrecht, 2014 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Part I: Gastro-intestinal bleedings

Description of studies

Three (non-randomised) comparative studies were analyzed in which patients with anticoagulation-associated gastrointestinal bleeding were included (Witt, 2012; Sengupta, 2015; Qureshi, 2014).

Witt (2012) performed a retrospective cohort study based on information recorded in databases. Patients with a gastrointestinal bleeding during warfarin use were included. Patients are divided into two categories: (1) restart of warfarin therapy, and no restart of warfarin. The follow-up duration was 90 days. Variables about the treatment and the gastrointestinal bleeding index were collected. Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed and Cox proportional hazards modelling was performed to correct for possible confounders. A total of 442 patients were included in the study. After the index gastrointestinal bleeding, warfarin therapy was restarted for 260 patients (58.8%) (including 41 patients for whom warfarin therapy was never stopped). The average time to restart was four days (two to nine days). In the restart group, heart valve indication for warfarin, and gastrointestinal bleeding at the rectal anus (especially hemorrhoidal bleeding) was more common. Also, compared to patients who did not restart warfarin, patients who restarted were on average younger (71.8 versus 77.7 years, p<0.001) and the source of the gastrointestinal bleeding was more often unknown (16.9% vs 26.9%, p=0.01).

Sengupta (2015) performed a prospective observational cohort study on consecutive patients who were hospitalized for gastrointestinal bleeding during anticoagulant treatment. Patients were classified into two groups: patients for whom anticoagulation was restarted, and patients for whom anticoagulation was not restarted. Patients were called 90 days after discharge to collect the following outcomes: thromboembolic events, hospital readmissions related to gastrointestinal bleeding, and mortality. Univariate and adjusted Cox proportional hazards were used to map the factors associated with thrombotic events, rebleeding and mortality. A total of 197 patients were included. Anticoagulation was stopped in 76 (39%) of patients (stopping was defined as withholding anticoagulation for at least 72 hours after discharge). After excluding patients for whom anticoagulation was restarted due to a thromboembolic episode in follow-up, 15 (20%) of the 76 patients restarted anticoagulation during the 90-day follow-up period. Adjustment was performed for age, sex, Charlson comorbidity index, need for transfusion, and active malignancy.

Qureshi (2014) performed a retrospective cohort study that included patients who experienced gastrointestinal bleeding while taking anticoagulants (n=1,329). For this study, data from the database of a health insurance company (Henry Ford Health System) was used. A gastrointestinal bleeding was defined as a decrease in hemoglobin by 3.2 mmol/L, visible bleeding, or positive endoscopic evaluation. Warfarin was restarted in 653 patients (49.1%) after a median duration of 50 days. Analyses stratified for the duration of the interruption of warfarin interruption were also performed. In Caucasians, patients with simultaneously high and low digestive tract hemorrhage, diabetes, patients with renal disease, previous coronary artery disease and fall history restarted less frequently (p<0,05). On average, comorbidities were more common in the group that did not restart treatment. The main reasons for not restarting were physician preference (18%) and patients' inability to come to the anticoagulation clinic (19%).

All three included studies reported on the outcome measures of mortality, recurrent bleeding (GIB) and thrombotic events. The results of the studies could not be pooled due to differences in study design and differences in the factors adjusted for in the multivariate analyses.

Mortality

In the study of Witt (2012) 52 (11.8%) patients died during the 90-day follow-up period. Restarting warfarin was associated with a lower risk of death (Hazard Ratio (HR, 95%CI): 0.31 (0.15 to 0.62) in multivariable analysis adjusted for propensity score, CDS, age, sex, GIB location, ICU admission, hypertension, previous stroke, pre-GIB rate INR in range, use of LMWH, length of stay, acute GIB treatment (blood transfusion). This association persisted in post-hoc analyses in which all patients who died within one week of the first (index) GIB were excluded. The mortality ratio was lowest when warfarin was resumed between 15 and 90 days after the index GIB (2.3%). The authors indicated that this survival difference may be related to more frequent restart of warfarin in patients with a better life expectancy, despite the corrections they have made.

In the study by Sengupta (2015), a total of 16 (8%) patients died during the 90-day follow-up period. None of the deaths in this cohort was related to recurrent GIB or thrombotic events. In multivariate analysis, risk of death was lower for patients who restarted compared to those who did not restart anticoagulants (HR 0.632, 95% CI 0.216 to 1.89).

In the study by Qureshi (2014), a total of 463 patients died over a two-year period. Patients restarting warfarin had lower mortality risk (adjusted HR 0.66, 95%CI 0.55 to 0.80) compared to the group that discontinued warfarin. Adjustments were made for age, sex, ethnicity, Charlson co-morbidity index, number of blood product transfusions, INR during admission, CHADS2 and HAS-BLED scores.

Recurrent bleeding

Witt (2012) reported recurrence of GIB in 36 out of 442 patients (8.4%). Compared to the group that did not restart warfarin, a higher percentage of patients who did restart warfarin had a recurrence of GIB (10% in the restarted group vs. 5.5% in the non-restart group). Multivariate analysis, controlled for propensity score, CDS, age, sex, indication for warfarin use, diagnosis of heart failure, location GIB, pre-GIB target INR, pre-GIB percentage INR within the range, use of LMWH, duration of hospitalization, acute GIB treatment (blood transfusion) found an increased risk of recurrent bleeding with warfarin restart (HR 1.32, 95%CI 0.50 to 3.57). Compared to all other patients, patients who restarted between one and seven days after the GIB had a higher risk of recurrence of GIB (6.23% vs. 12.4%).

In the study of Sengupta (2015), 27 patients (14%) were readmitted with a recurrent GIB (mean time to admission 13 days) in the 90-day follow-up. In multivariate regression analysis, restarting anticoagulants at hospital discharge was related to a higher risk of readmission associated with recurrent GIB within 90 days (HR 2.17, 95%CI 0.861 to 6.67).

In Qureshi (2014) 90 patients developed a recurrence severe GIB within 90 days. Restarting warfarin was not associated with a higher risk of recurrent blood loss (adjusted HR 1.18, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.10) compared to the group that stopped warfarin. The group that restarted within seven days had a higher risk of GIB. However, the cumulative incidence of other groups was almost the same as that of the group that restarted after 30 days.

Thromboembolic event

The outcome measure thromboembolic event was reported in three studies (Witt, 2012; Sengupta, 2015; Qureshi, 2014).

Witt (2012) reported thrombosis in the first 90 days of follow-up. A total of 11 patients (2.5%) had a thrombotic event (six arterial (five strokes and one systemic embolism) and five venous (three pulmonary embolism and two DVT)). Three of the strokes were fatal. Of the 260 patients who restarted warfarin, one (0.4%) had a thrombotic event (DVT) compared to 10 of 182 patients (5.5%) who did not restart. Restarting warfarin after GIB was associated with a lower risk of thrombosis (HR: 0.05, 95% CI: 0.01 to 0.58) in a multivariate analysis using propensity scoring for CDS, age, and sex. The occurrence of thrombosis in patients who restarted warfarin did not depend on the duration of warfarin interruption.

In the study of Sengupta (2015), seven (4%) patients developed a thromboembolic event during the 90-day follow-up period. Overall, one of the 121 (0.8%) patients in the group that restarted had a thrombotic event, compared with six of 76 (8%) patients in the group that did not resume anticoagulants. In multivariate analysis, restarting anticoagulants at hospital discharge was associated with a lower risk of thromboembolic events (HR 0.121, 95%CI 0.006 to 0.812).

In the study of Qureshi (2014), 221 (16.6%) patients developed a thromboembolic episode within one year of warfarin interruption. The risk was lower for patients who restarted warfarin (HR 0.71, 95%CI 0.54 to 0.93).

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for the outcome measures mortality, recurrent bleeding and thrombotic events has been downgraded to very low. The level of evidence started at low because these are non-randomized (retrospective) studies. In addition, due to limitations in the study design (difference in patient characteristics for which insufficient correction could be made), the level of evidence was further downgraded to very low.

Part II: Intracranial bleeding

Description of studies

Three (non-randomized) comparative studies including patients with intracranial hemorrhages were analyzed (Majeed, 2010; Gathier, 2013; Yung, 2012).

The study of Majeed (2010) described a multicenter cohort (three centers). Patients with warfarin-associated intracranial hemorrhage (radiologically confirmed) who had an INR of >1.5 at the time of hemorrhage were included. The occurrence of recurrent bleeding, thromboembolic complications and mortality in patients who were still alive after one week were analyzed. The analysis focused on patients at moderate to high risk of cerebral infarction (including patients with atrial fibrillation, mechanical heart valves, left ventricular thrombus, or previous cerebral infarction). A total of 234 patients met the inclusion criteria. For the 177 patients who survived the first week, the median follow-up duration was 69 weeks. Of these patients, 59 (33%) restarted warfarin. The patients who restarted warfarin were younger and had a longer follow-up than the patients who did not.

Yung (2012) reported on a cohort study that included follow-up patients with warfarin-related intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH, intracerebral or subarachnoidal) in one of 13 stroke centers in Canada (n=284). The main indications for anticoagulants were atrial fibrillation (67.3%), valve protheses (13.0%) and VTE (10.9%). Patients who restarted warfarin (n=91 (32%)) were compared with patients who did not restart warfarin (n=193 (68%)). Patients on antiplatelet therapy restarted warfarin less frequently. Patients with a cerebral infarction (in terms of neurological deficit) or with mechanical heart valve prostheses restarted more often. It is not clear whether the indications for the groups were different. Both crude data and the results of a logistic regression analysis are presented. In the multivariate analysis, the following variables were analyzed: age, sex, warfarin restart, Canadian Neurological Scale (CNS), presence of intraventricular blood, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, prior stroke or TIA, INR >3.0, and antiplatelet use.

In the study of Gathier (2013) patients with an ICH during treatment with acenocoumarol or phenprocoumon with an INR of at least 1.1 were included (N=38). Of these, 12 (32%) patients started antiplatelet therapy (TAR) and 15 (39%) patients started oral anticoagulation within two months of the ICH. Of the 15 patients who started oral coagulation, ten (67%) patients stopped oral anticoagulation again later. Reasons for discontinuation were that the treating physician no longer considered VKA to be indicated (n=4), recurrence of ICH (n=1), subdural hematoma (n=1), cerebral infarction with secondary hemorrhage (n=1), recurrent hematuria (n=1), patient's own choice (n=1), unknown (n=1) (Gathier, 2013).

One study reported the outcome measure of mortality (Yung, 2012). Two studies reported the outcome measure recurrent bleeding (ICH) (Majeed, 2010; Yung, 2012). Thrombotic events were reported in all three included studies (Majeed, 2010; Yung, 2012; Gathier, 2013). The results could not be pooled due to differences in study design and differences in the factors adjusted for in the multivariate analyses.

Results

Mortality

In the study of Yung (2012) unadjusted mortality was higher for patients who did not restart warfarin compared to patients who did restart (50.8% versus 30.8%). After multivariable analysis adjusting for age, sex, stroke severity, initial INR, and comorbidities, restarting warfarin was not associated with a higher risk of death within 30 days (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 0.49, 95%CI 0.26 to 0.93) or one year (aOR 0.79, 95%CI 0.43 to 1.43).

Recurrent bleeding

In the study of Majeed (2010) rates for intracranial hemorrhage or ischemic events (IE) were estimated using a Cox model. The model is based on patients with a cardiac indication for anticoagulants and/or with prior ischemic stroke who survived the first week without recurrence. Restarting warfarin increased the risk of recurrent intracranial hemorrhages (HR 5.57, 95%CI 1.80 to 17.25). The risk is calculated per patient-day. The daily risk of intracranial hemorrhage was lower for those who did not restart than for those who did restart (days one to 35: 0.18% vs. 0.75%; days 36 to 63: 0.044% vs. 0.20%; day 64 to 217: 0.0% vs. 0.20%; >218 days: 0.0% vs. 0.0069%) and decreased with time. The risk of ischemic events was higher for patients who did not restart compared to patients who restarted (day one to 77: 0.068% vs. 0.0%; day 78 to 329: 0.039% vs. 0.0%; >330 days: 0.017% vs. 0.0035%). These numbers were used to compile a figure comparing the cumulative risk of intracranial haemorrhages and ischemic events (IE) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The "total" risk for a treatment horizon of 3-years of recurrent intracranial hemorrhage (ICH)" and of ischemic events (IE) according to the time point of resumption of anticoagulation

In the study of Yung (2012), ICH-expansion or recurrence was not more common in the group that restarted warfarin than in the group that did not restart (unadjusted: 14 of 91 (15.4%) vs. 29 of 193 (15.0%)).

Thromboembolic event

The results for the outcome measure thromboembolic event in the study of Majeed (2010) are summarized in Figure 1 and the accompanying text (see above, i.e. ischemic events). Restarting warfarin reduced the risk of a thromboembolic event (HR 0.11, 95%CI 0.14 to 0.87)).

In the study of Yung (2012) it is reported that no thrombosis occurred within one year in the group of patients who restarted warfarin, and a nominally statistically insignificant number in the group of patients who did not restart. No exact numbers are mentioned.

In the study of Gathier (2013) outcomes per patient year (based on a total of 38 patients) were calculated. The primary outcome measure of stroke occurred twice in the control group in 35.4 patient years, compared to seven per 63.8 patient years with TARs and three per 19.5 patient years with oral anticoagulants. The incidence ratio of TARs versus control group was 2.7 (95%CI 0.5 to 16.3), OAC versus control group 1.9 (0.4 to 9.4).

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for the outcome measures thromboembolic event, bleeding and mortality was based on observational studies and therefore starts low. Because of additional limitations in the study design (difference in patient characteristics for which insufficient adjustments could be performed) the level of evidence was downgraded by one level to very low.

The included studies did not provide sufficient information concerning subgroups based on indications (AF versus mechanical heart valve) and contraindications (hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage versus hemorrhage due to probable amyloid angiopathy).

Part III: Traumatic brain injury (TBI)

Description of studies

In Albrecht (2014), bleeding and thrombotic events after discharge from the hospital after admission for TBI ("traumatic brain injury") were investigated based on insurance data (Medicare). Patients over the age of 64, who were admitted for TBI taking warfarin (or other anticoagulants, in the period before the TBI) were included. Patients who restarted warfarin after discharge (n=5811) were compared with patients who did not restart (n=4971). Many patients had atrial fibrillation (n= 8843 (82%)). The two groups were not comparable, with patients who did not restart staying longer in hospital, more often transferred to a specialized nursing ward (n (%): C:4282 (40%), I: 1924 (33%)), more often having a CHADS2 score >2 (n (%) C:4223 (85%) vs. I:4774 (82%), and more often having a modified HEMORR2HAGES score >3 (N (%): C:2994 (60%) vs. I:3234 (56%)). The analysis compared two "early restart" groups (<3 months after discharge and resumption of anticoagulants <6 months after discharge) with two "late restart" groups (>3 and >6 months after discharge, resume). Interactions between the time of restart, risk of stroke (CHADS2 >2), bleeding risk (modified HEMORR2HAGES >3) were also investigated.

Results

Mortality

The outcome mortality is not reported in Albrecht (2014).

Recurrent bleeding

The risk of cerebral hemorrhages was higher in patients restarting warfarin, compared to patients who did not restart (risk ratio (RR) 1.51, 95%CI 1.29 to 1.78).

Thrombotic event

In the modified regression models, restarting warfarin reduced the risk of thrombotic events over a given period of time (RR 0.77, 95%CI 0.67 to 0.88). The combined hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke outcome was lower in patients restarting warfarin (RR 0.83, 95%CI 0.72 to 0.96). There was no difference between early restart and low restart of warfarin.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for the outcome measures thromboembolic events and bleeding was based on observational studies and therefore started at low. Because of additional limitations in the study design (difference in patient characteristics for which insufficient correction can be made) the level of evidence have been downgraded by one level to very low. In addition, the study included patients with atrial fibrillation in particular. It is unclear to what extent the results can be extrapolated to other patient populations.

Updated search 2023

As already described, no RCT could be included from the updated search. Seven cohort studies fulfilled selection criteria. However, the working group is of the opinion that these observational data will be insufficient to provide a clear answer, i.e. the levels of evidence will still remain very low. It was therefore decided not to update the previous literature analysis but to provide a concise overview of the additional observation cohorts (N=7). General characteristics and the main findings are reported in Table 1. All studies reported on recurrent bleedings and thrombotic events. Sengupta (2018) and Tapaskar (2022) did not report on mortality and only included events resulting in hospital readmissions.

Part I: Gastro-intestinal bleeding

Two studies included patients with anticoagulation-associated gastro-intestinal bleedings (Tapaskar, 2022; Sengupta, 2018). One study (Little, 2021) included a mixed population (i.e. gastro-intestinal, intracranial and other), but reported data on the subgroups separately.

Mortality

In the cohort of Little (2021) a lower mortality risk was found for patients restarting anticoagulation, compared to no restarting (HR (95%CI): 0.54 (0.47 to 0.56). This effect estimate is in line with the findings of the initial literature analysis. Sengupta (2018) and Tapaskar (2022) did not report on mortality.

Rebleeding

In all three cohorts increased risks were observed for rebleedings for patients restarting anticoagulation, which is in line with the initial literature analysis. HRs ranged from 1.43 to 2.21. Tapaskar (2022) investigated warfarin and DOACs separately and observed a somewhat smaller effect estimate for restarting DOACs (HR: 1.43). This is consistent with the findings of Sengupta (2018). See Table 1 for further details.

Thromboembolic event

In the study of Tapaskar (2022) restart of both warfarin as well as DOACs was associated with a lower risk for thromboembolic events (hospital admissions), compared to no restart. This agrees to the findings of Little (2021). HRs ranged from 0.52 to 0.61. These findings agree with the initial literature analysis. In the study of Sengupta (2018) however no association was found.

Part II: Intracranial bleeding

Four studies included patients with anticoagulation-associated intracranial bleedings (Biffi, 2017; Lin, 2022; Nielsen, 2017; Newman, 2020). One study (Little, 2021) included a mixed population (i.e. gastro-intestinal, intracranial and other), but reported data on the subgroups separately.

Mortality

In all four studies lower mortality risks were found for patients restarting anticoagulation. The effect estimates range from 0.27 to 0.85. See Table 1 for details.

Rebleeding

Four of the five studies observed an increased risk for rebleedings in case of restart of anticoagulation, with effect estimates ranging from 1.20 to 2.20. In contrast, in the study of Newman (2020) a lower risk was observed (HR (95%CI): 0.62 (0.41 to 0.95). See Table 1 for further details.

Thromboembolic event

The studies observed lower risks for thrombosis in patients restarting anticoagulation. The effect estimates in the five additional cohorts range from 0.44 to 0.85. See Table 1 for further details.

Conclusion

The cohort studies found in the updated literature search, consistently showed higher risk for rebleedings and lower risks for thrombosis and mortality in patients restarting anticoagulation. These findings are broadly in line with the initial analysis of the literature. The more recent studies are larger and generally use more sophisticated methods to adjust for differences in patient characteristics between patients restarting and not restarting anticoagulation after an anticoagulation-associated bleeding. However, confounding by indication can still be present. In addition, the studies vary in several general characteristics such as type of anticoagulation, timing of restart and baseline.

'Klik op onderstaande tabel voor een betere weergave'

AF: atrial fibrillation, aHR: adjusted hazard ratio, DOAC: direct oral anticoagulants, GIB: gastrointestinal bleeding, HR: hazard ratio, ICH: intracerebral haemorrhage, OAC: oral anticoagulants, TE: thrombo-embolic event

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: what are the (un)favorable effects of (early) restarting of anticoagulation after anticoagulation- associated major bleeding (intracranial/intracerebral, gastrointestinal or other) in adult patients, compared to no/delayed restarting anticoagulation?

| P (Patients): | Adults with anticoagulation-associated major bleeding (intracranial/intracerebral, gastrointestinal, or other) |

| I (Intervention): | (early) restart of anticoagulation |

| C (Comparison): | Delayed or no restart of anticoagulation |

| O (Outcomes): | Recurrent major bleeding, mortality, thrombo-embolic event (arterial and venous) |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered mortality and recurrent major bleeding as critical outcome measures for decision-making, and thrombo-embolic events as an important outcome measure for decision-making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

- Major bleeding: fatal bleeding, and/or symptomatic bleeding in a critical area or organ, such as intracranial, intraspinal, intraocular, retroperitoneal, intra-articular or pericardial, or intramuscular with compartment syndrome, and/or bleeding causing a fall in hemoglobin levels of 1.24 mmol/L (20 g/L or greater) or more, or leading to a transfusion of 2 U or more of whole blood or red cells, as defined by the International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

A priori, the working group did not define the other outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined a risk difference of 3%* as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for mortality, venous thromboembolism, thromboembolic complications and major bleeding.

*Based on the differences applied in the guidelines on thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19. This working group derived the minimal clinically (patient) important differences from the ACCP (2012).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms. The initial search was performed in 2016. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The search included studies published in English or Dutch in 2010 or later. The systematic literature search resulted in 196 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: observational studies (including cohort studies) performed in patients with coagulation-associated major bleedings in which restart of anticoagulation was compared with no restart. Only studies with sufficient data representation were selected. Based on title and abstract 11 studies were initially selected. After screening of the full-text, five studies were excluded (see Table excluded studies). Six studies were included.

An updated search was performed on March 13th 2024. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 1,215 hits.

Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews/meta-analysis of RCT’s or cohort studies (published in 2020 or later), RCT’s and cohort studies of sufficient size (N>500), in which restart of anticoagulation was compared with no or delayed restart of anticoagulation, in adults with anticoagulation-associated major bleeding (intracranial/intracerebral, gastrointestinal or other). Phase-II trials were excluded.

ASReview was used for the selection of relevant articles. ASReview uses state-of-the-art active learning techniques to select the most relevant articles from a large number of potential hits. The first step is to indicate priors. A prior is an article that is found in the current number of hits and complies (or best matches) to the current selection criteria. The standard (default) model specifications were used for the screening for these papers. 43 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening using ASReview. After screening of the full-text, 36 studies were excluded (see exclusion table). Seven studies were included.

Results

From the initial literature search six cohort studies could be included. Since then, several RCT’s were published. However, those RCT’s were phase-2 trials (like Schreuder, 2021) or did not focus on patients with anticoagulation related bleeding (like Salman, 2021). So the updated search did not find (systematic reviews of) RCT’s that could be included. Beforehand, it was decided that the initial literature analysis will not be updated with observational data. The working group is of the opinion that this observation data will be insufficient to provide a clear answer, i.e. the levels of evidence will remain very low. Seven cohort studies did fulfil the inclusion criteria. A concise overview of these data is provided following the initial literature analysis.

Referenties

- Albrecht JS, Liu X, Baumgarten M, et al. Benefits and risks of anticoagulation resumption following traumatic brain injury. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1244-51.

- Biffi A, Kuramatsu JB, Leasure A, Kamel H, Kourkoulis C, Schwab K, Ayres AM, Elm J, Gurol ME, Greenberg SM, Viswanathan A, Anderson CD, Schwab S, Rosand J, Testai FD, Woo D, Huttner HB, Sheth KN. Oral Anticoagulation and Functional Outcome after Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Ann Neurol. 2017 Nov;82(5):755-765. doi: 10.1002/ana.25079. Epub 2017 Oct 31. PMID: 29028130; PMCID: PMC5730065.

- Little DHW, Sutradhar R, Cerasuolo JO, Perez R, Douketis J, Holbrook A, Paterson JM, Gomes T, Siegal DM. Rates of rebleeding, thrombosis and mortality associated with resumption of anticoagulant therapy after anticoagulant-related bleeding. CMAJ. 2021 Mar 1;193(9):E304-E309. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.201433. PMID: 33649169; PMCID: PMC8034308.

- Gathier CS, Algra A, Rinkel GJ, et al. Long-term outcome after anticoagulation-associated intracerebral haemorrhage with or without restarting antithrombotic therapy. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;36(1):33-7.

- Lin SY, Chang YC, Lin FJ, Tang SC, Dong YH, Wang CC. Post-Intracranial Hemorrhage Antithrombotic Therapy in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022 Mar 15;11(6):e022849. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.022849. Epub 2022 Mar 4. PMID: 35243876; PMCID: PMC9075312.

- Majeed A, Kim YK, Roberts RS, et al. Optimal timing of resumption of warfarin after intracranial hemorrhage. Stroke. 2010;41(12):2860-6.BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: The optimum timing of resumption of anticoagulation after warfarin-related intracranial hemorrhage in patients with indication for continued anticoagulation is uncertain. We performed a large retrospective cohort study to obtain more precise risk estimates.

- Newman TV, Chen N, He M, Saba S, Hernandez I. Effectiveness and Safety of Restarting Oral Anticoagulation in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation after an Intracranial Hemorrhage: Analysis of Medicare Part D Claims Data from 2010-2016. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2020 Oct;20(5):471-479. doi: 10.1007/s40256-019-00388-8. PMID: 31808136; PMCID: PMC7274872.

- Nielsen PB, Larsen TB, Skjøth F, Lip GY. Outcomes Associated With Resuming Warfarin Treatment After Hemorrhagic Stroke or Traumatic Intracranial Hemorrhage in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Apr 1;177(4):563-570. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9369. PMID: 28241151; PMCID: PMC5470390.

- Qureshi W, Mittal C, Patsias I, et al. Restarting anticoagulation and outcomes after major gastrointestinal bleeding in atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(4):662-8.

- SoSTART Collaboration. Effects of oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation after spontaneous intracranial haemorrhage in the UK: a randomised, open-label, assessor-masked, pilot-phase, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Neurol. 2021 Oct;20(10):842-853. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00264-7. Epub 2021 Sep 3. PMID: 34487722.

- Schreuder FHBM, van Nieuwenhuizen KM, Hofmeijer J, Vermeer SE, Kerkhoff H, Zock E, Luijckx GJ, Messchendorp GP, van Tuijl J, Bienfait HP, Booij SJ, van den Wijngaard IR, Remmers MJM, Schreuder AHCML, Dippel DW, Staals J, Brouwers PJAM, Wermer MJH, Coutinho JM, Kwa VIH, van Gelder IC, Schutgens REG, Zweedijk B, Algra A, van Dalen JW, Jaap Kappelle L, Rinkel GJE, van der Worp HB, Klijn CJM; APACHE-AF Trial Investigators. Apixaban versus no anticoagulation after anticoagulation-associated intracerebral haemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation in the Netherlands (APACHE-AF): a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2021 Nov;20(11):907-916. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00298-2. PMID: 34687635.Sengupta N, Feuerstein JD, Patwardhan VR, et al. The risks of thromboembolism vs. Recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding after interruption of systemic anticoagulation in hospitalized in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(2):328-35.

- Sengupta N, Marshall AL, Jones BA, Ham S, Tapper EB. Rebleeding vs Thromboembolism After Hospitalization for Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Patients on Direct Oral Anticoagulants. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Dec;16(12):1893-1900.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.05.005. Epub 2018 Jun 30. PMID: 29775794.

- Tapaskar N, Ham SA, Micic D, Sengupta N. Restarting Warfarin vs Direct Oral Anticoagulants After Major Gastrointestinal Bleeding and Associated Outcomes in Atrial Fibrillation: A Cohort Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Feb;20(2):381-389.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.11.029. Epub 2020 Nov 21. PMID: 33227428.

- Witt DM, Delate T, Garcia DA, et al. Risk of thromboembolism, recurrent hemorrhage, and death after warfarin therapy interruption for gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(19):1484-91.

- Yung D, Kapral MK, Asllani E, et al. Reinitiation of anticoagulation after warfarin-associated intracranial hemorrhage and mortality risk: the Best Practice for Reinitiating Anticoagulation Therapy After Intracranial Bleeding (BRAIN) study. Can J Cardiol. 2012;28(1):33-9.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

ICH |

|||||||

|

Majeed, 2010 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort

Setting: Multicentre

Country: Sweden, Canada

Source of funding: S.S. received consulting fees from many pharma, H.M. has received lecure fees from pharma, others have no potential conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients treated with warfarin, diagnosis (radiologically confirmed) of intracranial haemorrhage (ICD-10: 1600-1629), INR>1.5

Exclusion criteria: haemorrhage caused by severe accidents with multi-trauma or haemorrhagic transformation of ischemic stroke, death <1week after bleeding

N total at baseline: 234 (first week survivors n=177)

Important prognostic factors: median ± IQR: total: 75 (65-80) I: 70 (63-77) C: 78 (70.5-72)*

Sex male, n (%): Total: 112 (63) I: 31 (69) C:56 (64)

Indication for anticoagulation Total; I; C, n(%) AF: 102 (58); 22 (49); 79 (91) VT: 30 (17); 0; 0 Mechanical aortic valve:19 (11); 15 (33); 4 (5) Mechanical mitral valve:9 (5); 7 (16); 2(2) Other 17 (10); 1(2); 2(2):

Groups comparable at baseline? Patients who did not resume warfarin were significantly older.

|

No resumption of warfarin |

Resumption of warfarin (different time periods) (n=59, 33%)

|

Length of follow-up: Median 69 weeks (IQR 19-144)

Loss-to-follow-up: 113 (48%) of the patients died during follow up, with median survival of 4.5 years.

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

|

I vs. C Cox proportional hazards model at different time intervals without (I) and with (C) resumption of warfarin:

Risk of recurrent intracranial haemorrhage per day 1-35 days: 0.18%vs. 0.75% HR: 4.13

36-63 days: 0.044% vs. 0.20% HR: 4.46

64-217 days: 0.0% vs. 0.20% HR: ∞

>218 days: 0.0% vs. 0.0069% HR: ∞

Risk of ischemic event per day 1-77 days: 0.068%vs. 0.0% HR: 0.00

78-329 days: 0.039% vs. 0.0% HR: 0.0

>330 days: 0.017% vs. 0.0035% HR: 0.21

|

The modelling of risk for recurrent intracranial haemorrhage vs. ischemic stroke in patients with or without resumption of warfarin therapy is based on the population with cardiac indication for anticoagulation and/or with previous ischemic stroke and who had survived the first week without a recurrent event (n=132).

Resumption of warfarin at any given time point will increase the subsequent risk of recurrent intracranial haemorrhage and reduce the risk of a thromboembolic event. The optimal restart time must balance these 2 competing cumulative risks over the entire warfarin “treatment horizon”.

To determine the optimal restart time, we varied warfarin resumption between 1 and 50 weeks after the index intracranial bleed and calculated the total risk (before + after selected time point of resumption) of recurrence IH and of thromboembolic event through to the end of treatment. The calculation of cumulative risks used the rated displayed left (outcome). Given that it is implausible that the actual risk of intracranial bleed or thromboembolic event is 0, we have not used the observed daily risks directly, but instead we have blended the observed rates and cox model hazard ratio.

The results (figure) demonstrate how the total risk of intracranial haemorrhage and an ischemic event for the whole treatment period varies according to when warfarin is restarted. Based on this combined risk the optimal period of resumption of warfarin seems to be between 10 and 30weeks from the index intracranial haemorrhage over a survival- and treatment-horizon of 3 years. |

|

Yung, 2012 |

Type of study:

Setting: Cohort

Country: Canada

Source of funding: none |

Inclusion criteria: Warfarin related ICH (intracerebral or subarachnoid) submitted to 13 stroke centres, >18 years, who were or were not restarted on warfarin after hospitalization.

Exclusion criteria: previous ICH of any type, other concurrent active bleeding process, pregnancy, bleeding diathesis precluding reinitiation of warfarin, recent trauma, hemorrhagic conversion from ischemic stroke, neurosurgical instrumentation, intracranial neoplasia, were palliative, or if thrombolysis was administered.

N total at baseline: 284 Intervention: 91 Control: 193

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 71.8 (12.9) C: 74.4 (11.9) P=0.11

Sex: I: 46 (50.5) C: 110 (57.0) P=0.31

Stroke type: Intracerebral hemorrhage I: 78 (85.7) C: 174 (90.2) Subarachnoid hemorrhage I: 13 (14.3) C: 19 (9.8) P=0.27

GCS score: I: 10.2 (3.9) C: 7.2 (3.6) P=0.001

Atrial fibrillation at admission: I: 46 (50.5) C: 89 (46.1) P=0.49

Prosthetic valve: I: 19 (20.9) C: 18 (9.3) P=0.007

Antiplatelet use: I: 12 (13.2) C:45 (23.3) P=0.047

The main indications for anticoagulation included atrial fibrillation or flutter (67.3%), valve prosthesis (13.0%), and venous thromboembolic disease (10.9%).

Groups comparable at baseline? No |

Warfarin was restarted (n=91) in hospital

|

Warfarin not restarted (n=193) |

Length of follow-up: 1 year

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

|

Unadjusted outcomes I vs. C, n (%) Death: In hospital: 30 (33.0) vs. 98 (50.8) p=0.005 1 month: 29 (31.9) vs. 105 (54.4) p=0.001 6 months: 38 (41.8) vs. 114 (59.1) p=0.006 1 year: 44 (48) vs. 118 (61) P=0.04

ICH expansion or recurrrence (haemorrhage recurrence of expansion confirmed on serial CT or MRI): 14 (15.4) vs. 29 (15.0) P=0.94

Death or intracranial bleeding: 1 month: 32 (35.2) vs. 106 (54.9) p=0.002 1 year: 46 (50.5) vs. 118 (61.1) p=0.09

Death, bleeding, or thrombotic complication at 1 year: 47 (51.60) vs. 119 (61.7) p=0.11

Multivariate analysis Mortality (30 days): aOR: 0.49 (0.26-0.93) p=0.03

mortality (1 year) aOR: 0.79 (0.43-1.43) p=0.43

|

Data was collected from the registry of the Canadian stroke network (includes audit information prospectively collected on all consecutive patients with acute stroke or TIA evaluated in the ER and admitted to hospital at acute institutions; combined with data from the registered persons database.

Multivariate logistic regression model was performed including potential clinical variables with p<0.25 on univariate analysis.

Variables examined in multivariable analysis for warfarin reinitiation included: age, gender, CNS score, mechanical valve prosthesis, hypertension, previous stroke or TIA, and antiplatelet use on admission.

Variables considered in multivariable analysis of all-cause mortality and bleeding included: age, gender, warfarin reinitiation, CNS score, presenece of intraventricular haemorrhage, systolic BP, diabetes, previous stroke or TIA, INR >3.0 and antiplatelet use.

In multivariable analysis, patients receiving concurrent antiplatelet therapy on admission were less likely to be restarted on warfarin (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.34; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.16-0.74; P 0.007). Warfarin was more likely to be restarted in those with less severe stroke (CNS score < 7; aOR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.20-3.57; P 0.009) or with valve prostheses in situ (aOR 3.07; 95% CI, 1.29-7.27; P 0.011). Prior stroke or TIA, gastrointestinal bleeding, cirrhosis, renal disease, hypertension, CHADS2 score, presentation INR ( 3.0), BP, stroke location, and age were not associated with warfarin reinitiation.

Our findings suggest that patients with mild-to-moderate stroke severity (ie, CNS score <7) without intraventricular involvement and admission INR

3.0 may be restarted on warfarin without an excess risk of hemorrhage expansion or death. Patients that are high thrombotic risk with indications for long-term warfarin may be considered for reinitiation in-hospital, although the exact timing of reinitiation warrants further evaluation. Conversely, patients at high risk for thrombosis with either severe stroke (CNS score >7), intraventricular hemorrhage, or supratherapeutic INR on presentation should be carefully evaluated on an individual basis as they are more prone to poor outcomes. The routine use of neuroimaging to rule out intracranial hematoma expansion prior to reinitiating therapy may be reasonable. Finally, all decisions should be made in the context of each patient’s unique clinical circumstances and comorbidities. Patients who are not at high thrombotic risk may not derive net clinical benefit from early reinitiation of warfarin if the potential for in-hospital hematoma expansion or recurrent intracranial bleeding remains high. |

|

Gathier, 2013 |

Type of study: retrospective follow-up study

Setting: Hospital

Country: Netherlands

Source of funding: H.B. van der Worp has served as a consultant to Bristol-Meyers Squibb. |

Inclusion criteria: ICH while treated with acenocoumarol or phenprocoumom at time of ICH, INR ≥1.1, discharge from hospital

Exclusion criteria:-

N total at baseline: 40 I1 (OAC): 12 I2 (APM): 13 Control (No ATM): 13

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I1 (OAC): 70 (54-86) I2 (APM): 74 (44-87) Control (No ATM): 69 (48-85)

Reason for OAC Atrial fibrillation: I1 (OAC): 4 (33) I2 (APM): 8 (62) Control (No ATM): 6 (46)

Heart valve replacement: I1 (OAC): 2 (17%) I2 (APM): 0 Control (No ATM):0

Myocardial infarction I1 (OAC): 0 I2 (APM): 2 (15) Control (No ATM): 2 (15)

DVT/PE: I1 (OAC): 4 (33) I2 (APM): 0 Control (No ATM): 2 (15)

Cerebral infarction I1 (OAC): 0 I2 (APM): 2 (15) Control (No ATM): 1 (8)

Other I1 (OAC): 2 (17) I2 (APM): 1 (8) Control (No ATM): 2 (15)

Groups comparable at baseline? no |

I1 (OAC): oral anticoagulation was restarted within 2 months after ICH I2 (APM): antiplatelet therapy was restarted within 2 months after ICH

|

No antithrombotic medication was started within 2 months after ICH |

Length of follow-up: Median: 3.5 years

Loss-to-follow-up: 2, 1 reason unknown, 1 declined responding to questionnaire

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

|

Any stroke n I1 (OAC): 3 I2 (APM): 7 Control (No ATM): 2

Incidence per patient year: I1 (OAC): 15.4 I2 (APM): 11.0 Control (No ATM): 5.6

Incidence ratio (when compared to no ATM): (95%CI) I1 (OAC): 2.7 (0.5-16.3) I2 (APM): 1.9 (0.4-9.4)

Cerebral infarction, n I1 (OAC): 2 I2 (APM): 6 Control (No ATM): 2

Incidence per patient year: I1 (OAC): 10.2 I2 (APM): 9.4 Control (No ATM): 5.6

Incidence ratio (when compared to no ATM): (95%CI): I1 (OAC): 1.8 (0.3-12.9) I2 (APM): 1.7 (0.3-8.3)

|

Data were obtained by reviewing medical records and mailed questionnaires APM: antiplatelet therapy ATM: antitrombotic medication OAC: oral anticoagulation

The total of patient-years (PY) on OAC, antiplatelet therapy, and no antithrombotic medication after the ICH was calculated until the occurrence of an event or – in case no event occurred – until the date the questionnaire was administered or the date of death, whichever came first. |

|

GIB |

|||||||

|

Witt, 2012

|

Type of study: Retrospective cohort study

Setting: hospital

Country: US

Source of funding: CSL Behring LLC provided funding for the study |

Inclusion criteria: hospitalized/emergency care encounter for GIB, outpatient purchase of warfarin and INR in 60 days before GIB, KPCO membership, no GIB during 6 months before index GIB

Exclusion criteria: -

N total at baseline: 442 Intervention: 260 Control: 182

Important prognostic factors: age ± SD: I: 71.8±12.0 C: 77.7±11.3

Sex: I: 49.6% M C: 51.1% M

Indication for anticoagulation therapy: AF: I: 46.2% C: 56.6%, p=0.03 VTE: I: 25.8% C: 22.5%, [=0.44 Prostetic heart valve: I: 15.4% C: 1.1%, p<0.001 Other: I: 12.7% C: 19.8%, p=0.04

GIB location Large intestine: I: 28.1% C: 23.6%, p=0.26 Mouth-esophagus: I: 7.7% C: 5.5%, p=0.37 Rectum-anus: I: 19.6% C: 7.1%, p<0.01 Small-intestine: I: 2.7% C: 3.9%, p=0.50 Stomach-duodenum: I: 25.0% C: 32.7%, p=0.07 Not identified: I: 16.9% C: 26.9%, p=0.01

Groups comparable at baseline? No, prostetic heart valve and GIB localized to rectum-anus were more common in I group |

Resumption of warfarin (or continuation)

|

No resumption warfarin

|

Length of follow-up: 90 days

Loss-to-follow-up: -

Incomplete outcome data: -

|

I vs. C

Thrombotic event (arterial: stroke (n=5), systemic embolus (n=1), venous: PR (n=3), DVT (2): 1 (0.04%) vs. 10 (5.5%), p<0.001

HR 0.05 95%-CI: 0.01-0.58

Recurrent GIB 26 (10.0%) vs. 10 (5.5%), p=0.09

Multivariable analysis: HR 1.32 95%-CI: 0.50-3.57]

Deceased 15 (5.8%) vs. 37 (20.3%) P<0.001

Multivariable analysis: HR 0.31 95%-CI 0.15-0.62)

Analysis excluding deceased within 1 week: association remained |

Patients who never stopped warfarin are included in the reinitiation group (n=41)

Median time to resumption of warfarin was 4 days (2-9 days)/

Multivariate analysis was corrected for: controlled for propensity score, CDS, age, sex, indication for warfarin use, prior heart failure diagnosis, location of GIB, pre-FIB target INR, pre-GIB percentage of INR in range, reception of LMWH, length of ED/inpatient stay, acute GIB treatment

Compared with all other patients the rate of recurrent GIB was sign increased when warfarin therapy was resumed between 1 and 7 days after GIB (6.23% vs. 12.4%, p=0.03).

Most common causes of death: related to malignancy (28.8%), infection (19.2%), cardiac disease (17.3%). No recurrent GIB resulted in death

|

|

Sengupta, 2015 |

Type of study: prospective observational cohort

Setting: Single setting (hospital)

Country: US

Source of funding: none |

Inclusion criteria: GIB while on systemic anticoagulation (clinically significant GIB: overt hematochezia, hematemesis, melena, guaiac-positive stools, with sign. Drop in haemoglobin).

Exclusion criteria:-

N total at baseline: 208 (excluded: 11) Intervention: 121 Control:76

Important prognostic factors2: Age, median (IQR), years: I: 75 (64,82) C:77 (66,84), p=0.32

Sex: I: 55% M C: 62% M, p=0.38

Indication for anticoagulation I vs. C, p Atrial fibrillation: I: 71 (59%) C: 44 (58%), p=1.00 History DVT: I: 23 (19%) C: 13 (17%), p=0.85 History PE: I: 17 (14%) C: 5 (7%), p=0.16 Prosthetic valve: I: 18 (15%) C: 0 (0%), p=0.000 Portal vein thrombosis: I: 2 (2%) C: 4 (5%), p=0.21 Post surgical procedure: I: 1 (1%) 2 C: (3%), p=0.56

Cause of GIB Esophagitis I: 4 (3%) C: 2 (3%), p=1.00 Gastric ulcer I: 8 (7%) C: 7 (9%), p=0.58 Gastritis I: 8 (7%) C: 3 (4%), p=0.53 Dieulafoy's I: 5 (4%) C: 2 (3%), p=0.71 AVMs I: 15 (12%) C: 3 (4%), p=0.07 Duodenal ulcer I: 5 (4%) C: 6 (8%), p=0.34 Diverticulosis I: 6 (5%) C: 10 (13%), p=0.06 Colonic ulcer I: 3 (2%) C: 2 (3%), p=1.0 Hemorrhoids I: 5 (4%) C: 1 (1%), p=0.41 Other (ischemic colitis 3, Mallory Weiss Tear 3,GAVE 1 duodenitis 3) I: 6 (5%) C: 4 (5%), p=1.00 Colitis I: 2 (2%) C:4 (5%), p=0.21 Post polypectomy I: 6 (5%) C: 2 (3%), p=0.71 Radiation proctitis I: 4 (3%) C: 2 (3%), p=1.00 Source not identified I: 45 (37%) C: 27 (36%), p=0.88

Management No blood transfusion I: 49 (40%) C: 24 (32%), p=0.23 No vitamin K I: 66 (55%) C: 46 (61%), p=0.46 No FFP I: 74 (61%) C: 48 (63%), p=0.88 ICU care I: 54 (45%) C: 37 (49%), p=0.66 Endoscopic intervention I: 26 (21%) C: 13 (17%), p=0.58

Groups comparable at baseline? Intervention group: more prostetic valves, prior stroke or TIA, or prior GIB. C group: more likely to have history of active malignancy. |

Anticoagulation Resumed (n=121)

|

Anticoagulation Stopped (n =76)

|

Length of follow-up: 90 days

Loss-to-follow-up: 12% I: 8171 (11%) person-days C: 4295 (14%) person-days of follow-up P=0.50

Incomplete outcome data: Patients who died during initial hospitalization were excluded from statistical analysis n=11 (5%)

|

I vs. C

Thromboembolic event venous thromboembolism (pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis (DVT)), arterial thromboembolism, stroke, or transient ischemic attack. 1 (0.8%) vs, 6 (8%), p=0.003

HR multivariate analysis controlling for propensity score: 0.121, 95%-CI=0.006–0.812

Recurrent GIB readmission to any hospital in the 90-day follow-up period because of another episode of GIB

HR=2.17, 95% CI=0.861–6.67, P =0.10

Importantly, there were no deaths in this group of patients readmitted with GIB.

Mortality: HR multivariate analysis: HR=0.632, 95% CI=0.216–1.89, P =0.40 |

At hospital discharge, the decision to resume or discontinue anticoagulation was made by the physicians directly responsible for patient care, depending on clinician and patient preferences. We categorized patients into whether anticoagulation was resumed or whether there was interruption of anticoagulation. Interruption of anticoagulation was defined as holding systemic anticoagulation for 72 h or more after discharge.

Analyses were adjusted for the following factors included in the propensity score: age, gender, Charlson comorbidity index, transfusion requirements, and active malignancy.

After excluding the patients who restarted systemic anticoagulation because of having a thromboembolic episode in follow-up, 15 (20%) of the original 76 patients in the anticoagulation interruption cohort had restarted anticoagulation by the 90-day follow-up call. In these patients, anticoagulation was restarted at a median of 25 days from initial discharge. None of the 15 patients who restarted anticoagulation in follow-up were readmitted to the hospital within 90 days because of recurrent GIB.

No raw data for recurrent GIB and mortality

In summary, we found that resuming anticoagulation aft er hospitalization for GIB was associated with a signifi cantly decreased adjusted risk of major thromboembolic events over 90 days, without a signifi cantly increased risk of recurrent GIB. Th ese data support the recommendation that anticoagulation should be continued aft er an episode of GIB whenever possible. |

|

Qureshi, 2014

|

Type of study: Retrospective cohort

Setting: Hospital

Country: US

Source of funding: department of internal medicine of henry ford health system |

Inclusion criteria: Patients who developed major GIB while taking warfarin and then had evidence of resolution of major GIB (defined as stability of hemoglobin levels with <1 g decrease of hemoglobin for 48 hours)

Exclusion criteria: pts who died <72h of GIB, hospice, postoperative or valvular AF, patients in whom primary indication for anticoagulation was any reason other than nonvalvular AF, warfarin was not interrupted for at least 48h

N total at baseline: 1329 Intervention: 653 Control:676

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 74.8±10.7 C:75.3±10.7, p=0.43

Sex: I: 55.7% M C: 49.7% M, p=0.03

Groups comparable at baseline? Caucasians, patients with concomitant upper and lower sources for GIB, diabetics, patients with renal disease, history of coronary artery disease, and history of falls were less likely to be restarted on warfarin (p <0.05). Overall, there were greater co-morbidity burdens in the patients who were not restarted on warfarin. Major reasons for not restarting warfarin were physician preference (18%) and patient’s inability to follow up with the anticoagulation clinic (19%). |

Restarting warfarin

|

Warfarin cessitation (or starting>6 months)

|

Length of follow-up: 2 years

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

|

I vs. C

Recurrent major GIB (<90 days) defined as any of the following: (1) >2 g of hemoglobin decrease from the last known hemoglobin level warranting hospitalization, (2) need for blood transfusion of at least 2 units, and (3) visible bleeding by health personnel or endoscopic evidence of stigmata of recent bleeding in the form of visible bleeding or clot.

Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI): 0.71 (0.54-0.93), p=0.01

Thromboembolism (1 year) defined as venous thromboembolism (pulmonary embolism and deep venous thrombosis), arterial thromboembolism, or stroke or transient ischemic attack.

Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI): 0.71 (0.54-0.93), p=0.01

Mortality Adjusted hazard ratio 0.66, 95% confidence interval 0.56 to 0.81, p <0.0001 |

GIB was defined as a decrease in hemoglobin of 2 g/dl and/or transfusion of 2 units of packed red blood cells with at least one of the following: hematemesis, melena, hematochezia, bright red blood per rectum, blood in nasogastric aspirate, or bleeding documented during an endoscopic procedure.

Restarting warfarin was defined as prescription of warfarin with objective evidence of increase in international normalized ratio to 2.0 with evidence of at least 2 days of discontinuation of warfarin as observed by chart review. Patients who interrupted warfarin after 1 month of restarting warfarin (54; 4.1%) were included in the group that restarted warfarin. Patients who started warfarin after 6 months of interruption (39, 2.9%) were included in the group that did not restart warfarin (warfarin cessation group). Patients who interrupted warfarin within the first month (12; 0.9%) were included in the warfarin cessation group.

Multivariate analysis were adjusted for age, gender, race, Charlson co-morbidity index, number of blood product transfusions, international normalized ratio on admission, and CHADS2 and HAS-BLED scores |

|

Traumatisch hersenletsel |

|||||||

|

Albrecht, 2014 |

Type of study: Retrospective analysis insurance beneficiaries

Setting: hospital

Country: USA

Source of funding: none reported |

Inclusion criteria:medicare benificiaries, >65yrs, hospitalized for traumatic brain injury (2006-2009) who received warfarin in the month prior to the injury (for: AF).

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: 10 782 I1: 1877 I2: 3934 C: 4971

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I1: 81.0 (7.4) I2: 80.1 (7.2) C: 82.4 (7.3)

Sex: n male (%) I1: 691 (37) I2: 1323 (34) C: 1836 (37)

Atrial fibrillation: I1:1532 (82) CHADs2 score >2, No. (%) I1: 1577 (84) I2: 3197 (81) C: 4223 (85) p<.001

Modified HEMORR2HAGES score >3, No. (%) I1: 1141 (61) I2: 2093 (53) C: 2994 (60) p<.001

Groups comparable at baseline? No, Beneficiaries differed by warfarin use categories (Table 1). Beneficiaries who used warfarin for 7 to 12months (mean [SD] age, 80.1 [7.2] years) were younger than those who used warfarin for 1 to 6 months (mean [SD] age, 81.0 [7.4] years) and thosewhodid not use warfarin (mean [SD] age, 82.4 [7.3] years; analysis of variance P < .001). They were less likely to have a hospital stay of 9 ormore days (15%vs 17%vs 28%; P < .001). Beneficiaries who used warfarin for 7 to 12 months were less likely to have Alzheimer disease and related dementias (27% vs 35% vs 39%; P < .001). |

Warfarin (or other anticoagulant) resumption I1: for 1-6 months I2: 7-12 months

|

No resumption

|

Length of follow-up: Mean (SD) length of follow-up after discharge from hospitalization for TBI was 594.9 (405.6) days

Loss-to-follow-up: -

Incomplete outcome data: I1: 719 (38%) I2: 1205 (31%) C: 2358 (47%)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe) Patients transferred to skilled nursing facility (SNF) have missing values for warfarin use (other payment):

|

Trombotic event, n, incidence rate (per 1000) I: n=400, 113.5 (95%CI: 102.9-125.2) C: 562, 155.9 (143.5-169.3) RR 0.77 [0.67-0.88]

Hemorrhagic event, n, incidence rate (per 1000): I: 422, 119.8 (108.9-131.8) C: 309 85.7 (76.7-95.8) RR: 1.51 (1.29-1.78)

Hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke, n, incidence rate (per 1000): I: 339, 96.2 (87.5-105.8) C: 494, 137.0 (122.6-153.2) RR: 0.83 (0.72-0.96)

The interaction between period and lagged warfarin use was not statistically significant; therefore, the regression results are interpreted as the effect of the lagged warfarin use variable on outcomes averaged over the first 12 periods following discharge from hospitalization for TBI. |

The final model for hemorrhagic outcomes included the following time-invariant and time-varying variables: age, sex, race, pre-TBI hemorrhagic event, lagged warfarin use, period (continuous), other anticoagulant use in the period, length of hospital stay (categorical), discharge to SNF, atrial fibrillation, liver disease, chronic kidney disease, ethanol abuse, malignant neoplasm, hypertension, anemia, coagulation defect, neurological disease, and thrombotic event in the period.

The final model for thrombotic outcomes included the following time-invariant and time-varying variables: age, sex, race, pre- TBI thrombotic event, lagged warfarin use, hemorrhagic event in the period, period (continuous), other anticoagulant use in the period, length of hospital stay (categorical), discharge to SNF, stroke or transient ischemic attack, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and heart failure.

Restricting our analyses to patients with atrial fibrillation did not significantly affect estimates of the effect of warfarin receipt. |

Quality assessment table: herstarten antistolling na bloeding

|

Study reference

(first author, year of publication) |

Bias due to a non-representative or ill-defined sample of patients?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to insufficiently long, or incomplete follow-up, or differences in follow-up between treatment groups?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to ill-defined or inadequately measured outcome?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate adjustment for all important prognostic factors?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

ICH |

||||

|

Majeed, 2010 |

Likely (reasons for restarting therapy are not described, but likely that the factors for restarting are also prognostic factors; therefore likely to cause bias). |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Gathier, 2013 |

Likely (reasons for restarting therapy are likely also prognostic factors; therefore likely to cause bias). |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Likely (not all relevant prognostic factors were corrected for / available) |

|

Yung, 2012 |

Likely (reasons for restarting therapy are likely also prognostic factors; therefore likely to cause bias). |

Unclear (retrospective, not fully clear how long follow-up was) |

Unlikely |

Likely (not all relevant prognostic factors were available from registration) |

|

GIB |

||||

|

Witt, 2012 |

Likely (reasons for restarting therapy are likely also prognostic factors; therefore likely to cause bias). |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Sengupta, 2015 |

Likely (reasons for restarting therapy are likely also prognostic factors; therefore likely to cause bias). |

Unlikely (relatively high loss-to-follow-up, however comparable in both groups) |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Qureshi, 2014 |

Likely (reasons for restarting therapy are likely also prognostic factors; therefore likely to cause bias). |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Likely (not all relevant prognostic factors were corrected for / available) |

|

TBI |

||||

|

Albrecht, 2014 |

Likely (reasons for restarting therapy are likely also prognostic factors; therefore likely to cause bias). |

Likely, patients transferred to skilled nursing facility (SNF) have missing values for warfarin use (other payment). Incomplete data differs for groups. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Table of excluded studies

Initial search

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Poli D, Antonucci E, Dentali F, Erba N, Testa S, Tiraferri E, et al. Recurrence of ICH after resumption of anticoagulation with VK antagonists: CHIRONE study. Neurology. 2014;82(12):1020-6 |

No comparative study; wrong outcome (only recurrence) |

|

Pasquini M, Charidimou A, van Asch CJ, Baharoglu MI, Samarasekera N, Werring DJ, et al. Variation in restarting antithrombotic drugs at hospital discharge after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2014;45(9):2643-8 |

Wrong study design (descriptive analysis) |

|

Chari A, Clemente Morgado T, Rigamonti D. Recommencement of anticoagulation in chronic subdural haematoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Neurosurg. 2014;28(1):2-7. |

Wrong study population

|

|

Hawryluk GW, Austin JW, Furlan JC, Lee JB, O'Kelly C, Fehlings MG. Management of anticoagulation following central nervous system hemorrhage in patients with high thromboembolic risk. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(7):1500-8 |

Wrong study design (also included case reports) |

Updated search

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Barra ME, Forman R, Long-Fazio B, Merkler AE, Gurol ME, Izzy S, Sharma R. Optimal Timing for Resumption of Anticoagulation After Intracranial Hemorrhage in Patients With Mechanical Heart Valves. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024 May 21;13(10):e032094. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.123.032094. Epub 2024 May 18. PMID: 38761076; PMCID: PMC11179836. |

Small cohort (N<500) |

|

Brouillard P, Diallo EH, Masson JB, Raymond JM, Riahi M, Potter B, Kouz R, Potvin J. Real-World Management Strategies of Anticoagulated Atrial Fibrillation Patients After a Clinically Significant Bleeding Episode. Can J Cardiol. 2024 Jul;40(7):1283-1290. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2023.12.032. Epub 2024 Jan 4. PMID: 38181972. |

Small cohort (N<500) |

|

Gennaro N, Ferroni E, Zorzi M, Denas G, Pengo V. ISCHEMIC STROKE AND MAJOR BLEEDING WHILE ON DIRECT ORAL ANTICOAGULANTS IN NAÏVE PATIENTS WITH ATRIAL FIBRILLATION: IMPACT OF RESUMPTION OR DISCONTINUATION OF ANTICOAGULANT TREATMENT. A population-based study. Int J Cardiol. 2024 Jan 1;394:131369. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2023.131369. Epub 2023 Sep 16. PMID: 37722453. |

Not in agreement with PICO (wrong outcome) |

|

Kuramatsu JB, Sembill JA, Gerner ST, Sprügel MI, Hagen M, Roeder SS, Endres M, Haeusler KG, Sobesky J, Schurig J, Zweynert S, Bauer M, Vajkoczy P, Ringleb PA, Purrucker J, Rizos T, Volkmann J, Müllges W, Kraft P, Schubert AL, Erbguth F, Nueckel M, Schellinger PD, Glahn J, Knappe UJ, Fink GR, Dohmen C, Stetefeld H, Fisse AL, Minnerup J, Hagemann G, Rakers F, Reichmann H, Schneider H, Wöpking S, Ludolph AC, Stösser S, Neugebauer H, Röther J, Michels P, Schwarz M, Reimann G, Bäzner H, Schwert H, Claßen J, Michalski D, Grau A, Palm F, Urbanek C, Wöhrle JC, Alshammari F, Horn M, Bahner D, Witte OW, Günther A, Hamann GF, Lücking H, Dörfler A, Achenbach S, Schwab S, Huttner HB. Management of therapeutic anticoagulation in patients with intracerebral haemorrhage and mechanical heart valves. Eur Heart J. 2018 May 14;39(19):1709-1723. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy056. PMID: 29529259; PMCID: PMC5950928. |

Not in agreement with PICO (wrong comparison); small study (N<500) |

|

Li L, Poon MTC, Samarasekera NE, Perry LA, Moullaali TJ, Rodrigues MA, Loan JJM, Stephen J, Lerpiniere C, Tuna MA, Gutnikov SA, Kuker W, Silver LE, Al-Shahi Salman R, Rothwell PM. Risks of recurrent stroke and all serious vascular events after spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage: pooled analyses of two population-based studies. Lancet Neurol. 2021 Jun;20(6):437-447. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00075-2. Erratum in: Lancet Neurol. 2021 Aug;20(8):e5. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00185-X. PMID: 34022170; PMCID: PMC8134058. |

Not in agreement with PICO |

|

Liu CH, Wu YL, Hsu CC, Lee TH. Early Antiplatelet Resumption and the Risks of Major Bleeding After Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke. 2023 Feb;54(2):537-545. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.122.040500. Epub 2023 Jan 9. PMID: 36621820. |

Not in agreement with PICO |

|

Meyre PB, Blum S, Hennings E, Aeschbacher S, Reichlin T, Rodondi N, Beer JH, Stauber A, Müller A, Sinnecker T, Moutzouri E, Paladini RE, Moschovitis G, Conte G, Auricchio A, Ramadani A, Schwenkglenks M, Bonati LH, Kühne M, Osswald S, Conen D. Bleeding and ischaemic events after first bleed in anticoagulated atrial fibrillation patients: risk and timing. Eur Heart J. 2022 Dec 14;43(47):4899-4908. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac587. PMID: 36285887. |

Not in agreement with PICO (no comparison) |

|

Murphy MP, Kuramatsu JB, Leasure A, Falcone GJ, Kamel H, Sansing LH, Kourkoulis C, Schwab K, Elm JJ, Gurol ME, Tran H, Greenberg SM, Viswanathan A, Anderson CD, Schwab S, Rosand J, Shi FD, Kittner SJ, Testai FD, Woo D, Langefeld CD, James ML, Koch S, Huttner HB, Biffi A, Sheth KN. Cardioembolic Stroke Risk and Recovery After Anticoagulation-Related Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke. 2018 Nov;49(11):2652-2658. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.021799. PMID: 30355194; PMCID: PMC6211810. |

Not in agreement with PICO (wrong outcomes) |

|

Naylor RM, Dodin RE, Henry KA, De La Peña NM, Jarvis TL, Labott JR, Van Gompel JJ. Timing of Restarting Anticoagulation and Antiplatelet Therapies After Traumatic Subdural Hematoma-A Single Institution Experience. World Neurosurg. 2021 Jun;150:e203-e208. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.02.135. Epub 2021 Mar 5. PMID: 33684586. |