Tromboseprofylaxe op de Intensive Care bij COVID-19

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van tromboseprofylaxe bij COVID-19 patiënten op de intensive care?

Aanbeveling

Geef een standaard profylactische dosis antistolling aan patiënten met COVID-19 op de intensive care.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de verschillen in klinische uitkomsten tussen 1) behandeling met therapeutische dosis antistolling versus standaard of intermediaire dosis tromboseprofylaxe, en 2) behandeling met intermediaire dosis tromboseprofylaxe versus standaard dosis tromboseprofylaxe, bij patiënten met COVID-19 op de intensive care (IC). Tot op heden zijn 3 RCTs gevonden die de vergelijking in de eerste PICO – therapeutische dosis versus profylactische of intermediaire dosis - hebben onderzocht. Er is één studie gevonden, waarvan de resultaten op twee meetmomenten in twee artikelen beschreven werden, die de vergelijking in de tweede PICO – intermediaire dosis versus profylactische dosis - heeft onderzocht. Tabel 1 geeft een overzicht van voorbeelddoseringen voor drie soorten low-molecular-weight heparines (LMWHs).

Tabel 1. Voorbeelddoseringen voor de meest gebruikte LMWHs in Nederland

|

|

Doseringen |

||

|

Nadroparine |

Dalteparine |

Enoxaparine |

|

|

Standaard profylactische dosering |

2850 IU eenmaal daags |

2500 IU eenmaal daags |

20 mg eenmaal daags

|

|

Intermediair profylactische dosering |

5700 IU eenmaal daags (of 2 dd 2850 IU) |

5000 IU eenmaal daags |

40 mg eenmaal daags

|

|

Therapeutische dosering |

11.400 IU per dag voor gewicht tussen 50 en 70 kg; 15.200 IU per dag voor gewicht boven de 70 kg; en 17.100 IU per dag voor gewicht boven de 90 kg |

200 IU per kg per dag met een maximum van 18.000 IU per dag |

1,5 mg per kg per dag of 1,0 mg tweemaal daags |

LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; IU, International Unit.

Cruciale uitkomstmaten

Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten mortaliteit, veneuze trombo-embolie, en het aantal dagen vrij van mechanische ventilatie is het op basis van de gevonden resultaten onzeker of het gebruik van een therapeutische dosis antistolling zou kunnen resulteren in een verschil in deze uitkomstmaten, vergeleken met een profylactische dosis antistolling. Hetzelfde geldt voor de vergelijking tussen een intermediaire dosis en profylactische dosis antistolling. De bewijskrachten voor beide vergelijkingen waren voor deze drie uitkomstmaten zeer laag.

Voor trombo-embolische complicaties samengenomen (arteriële en veneuze trombo-embolie) werd gevonden dat behandeling met een therapeutische dosis antistolling mogelijk kan resulteren in een reductie in trombo-embolische complicaties vergeleken met een profylactische dosis antistolling. De bewijskracht hiervoor was laag. Het is onduidelijk of een intermediaire dosis antistolling zou kunnen leiden tot een verschil in trombo-embolische complicaties vergeleken met een profylactische dosis antistolling. De bewijskracht was zeer laag.

Behandeling met therapeutische dosis antistolling zou kunnen resulteren in geen tot een klein verschil in ernstige bloedingen vergeleken met een profylactische of intermediaire dosis antistolling. De bewijskracht hiervoor was laag. Het is onduidelijk of behandeling met een intermediaire dosis antistolling zou ook kunnen resulteren in een verschil in ernstige bloedingen vergeleken met een profylactische dosis antistolling. De bewijskracht hiervoor was zeer laag.

Belangrijke uitkomstmaten

Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaat duur van ziekenhuisopname is het onduidelijk of behandeling met een therapeutische dosis antistolling zou kunnen resulteren in een verschil in de duur van ziekenhuisopname vergeleken met een profylactische dosis antistolling. De bewijskracht hiervoor was zeer laag. Er is geen bewijs gevonden voor het effect van een intermediaire dosis antistolling vergeleken met en profylactische dosis antistolling op de duur van ziekenhuisopname. Voor de duur van IC opname is het ook onduidelijk of behandeling met een therapeutische dosis antistolling zou kunnen resulteren in een verschil in de duur van IC opname vergeleken met een profylactische dosis antistolling. Hetzelfde geldt voor de vergelijking tussen een intermediaire dosis antistolling vergeleken met en profylactische dosis antistolling. De bewijskracht voor beide vergelijkingen was zeer laag.

Er is geen bewijs gevonden voor het effect van een therapeutische dosis antistolling vergeleken met een profylactische dosis antistolling op orgaan support anders dan mechanische ventilatie. Het is onduidelijk of behandeling met een intermediaire dosis antistolling vergeleken met een profylactische dosis antistolling zou kunnen resulteren in een verschil in orgaan support anders dan mechanische ventilatie, meer specifiek nier vervangende therapie. De bewijskracht hiervoor was zeer laag.

Er is geen bewijs gevonden voor het effect op het aantal dagen vrij van orgaan ondersteuning anders dan mechanische ventilatie voor de vergelijking tussen 1) een therapeutische dosis antistolling vergeleken met een profylactische dosis antistolling, en 2) een intermediaire dosis antistolling vergeleken met een profylactische dosis antistolling. Voor de uitkomstmaten heparine geïnduceerde trombocytopenie en cumulatieve transfusie zijn geen resultaten beschreven in de geselecteerde studies.

Interpretatie

De interpretatie van de studies is om meerdere redenen complex. De INSPIRATION studie komt qua populatie niet overeen met de Nederlandse populatie op de Intensive Care Unit (ICU), gezien het relatief lage percentage invasieve beademing (dat samengenomen met non-invasieve beademing rond de 50% lag) en de lage APACHE II score van de geïncludeerde patiënten (mediaan 8, IQR 5-11). In de multiplatform studie van Goligher (2021) is dit percentage ook laag, maar daar kregen patiënten high flow nasal oxygen of non invasive ventilation en slechts 1,5% van de patiënten zuurstof via masker of low flow nasal oxygen. Ook was de APACHE II score beduidend hoger (mediaan 14, IQR 8-21), hetgeen meer in lijn is met de Nederlandse situatie op de ICU. De studie van Lemos (2020) uit Brazilië met tweemaal 10 patiënten is heel klein en daarom niet representatief. Met betrekking tot bepaalde subgroepen, zoals leeftijd of D-dimeer niveau bij presentatie, kon geen onderscheid worden gevonden in de analyse van de studies. Daarom konden geen aanbevelingen worden gedaan voor deze subgroepen. Alle cruciale uitkomsten waren secundaire uitkomsten in de studies. De studies hadden samengestelde primaire eindpunten die onderling onvergelijkbaar bleken. Zo werden bijvoorbeeld non-invasieve en invasieve beademing samen genomen, of sterfte en trombotische complicaties. Door deze verschillende samengestelde uitkomstmaten kon deze data niet gepoold worden. Een ander belangrijk punt van overweging is het feit dat de behandeling van patiënten met COVID-19 in 2021 in Nederland veranderd is ten opzichte van 2020, het jaar waarin de studies zijn verricht. Zo is er nu standaardbehandeling met IL-6 remmers en monoklonale antistoffen. In verschillende van de gevonden studies kreeg een substantieel deel van de patiënten bijvoorbeeld geen behandeling met steroïden en werd slechts een kleine minderheid behandeld met IL-6 remmers. Alle studies hadden een zogenaamd ‘open label design’, waardoor bias kan zijn opgetreden bij zachtere uitkomstmaten als veneuze trombo-embolie en bloeding. De artsen wisten welke behandeling een patiënt kreeg, hetgeen de klinische verdenking en diagnostische strategie heeft kunnen beïnvloeden. Eindpunten werden slechts deels centraal of lokaal geadjudiceerd, waardoor de validiteit van de diagnose longembolie (overgrote meerderheid van de trombotische events) niet in alle studies is na te gaan. De inclusiecriteria tussen de studies waren ook erg wisselend, met soms -maar niet altijd - selectie van patiënten met hoge tot zeer hoge D-dimeerwaarden. Patiënten met een van tevoren ingeschat hoog bloedingsrisico werden uitgesloten. De incidentie van bloedingscomplicaties zou daarom bij toepassing van therapeutische antistolling in de dagelijkse praktijk hoger kunnen uitvallen. Naast beademing was er voor andere orgaanondersteuning (zoals nierfunctievervangende therapie en extracorporele membraanoxygenatie (ECMO)) alleen literatuur beschikbaar met een zeer lage bewijskracht. Wat betreft veiligheid was er alleen rapportage van bloedingen en niet van cumulatieve transfusie, en kan er niet uitgesloten worden dat er een onderrapportage is geweest van milde bloedingscomplicaties. Ook is er geen data gerapporteerd over het voorkomen van van heparine geïnduceerde trombocytopenie (HIT). Dit alles maakt dat er nog kennislacunes zijn. Het zal moeten blijken of resultaten van nieuwe studies de conclusies van de samenvatting van de literatuur zullen veranderen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Het doel van toedienen van antistolling is het voorkómen van veneuze en, in mindere mate, arteriële trombose. Er is geen verschil in toediening of impact van de profylactische of intermediaire versus de therapeutische dosis LMWH; beide worden op dezelfde manier subcutaan geïnjecteerd. Er zijn geen subgroepen met andere uitkomsten gevonden.

Patiënten die een behandeling met medicijnen voor antistolling krijgen vinden complete en eenduidige informatievoorziening belangrijk, o.a. over de indicatie en de veiligheid en risico’s van de behandeling (onderwerpen die van belang zijn in de communicatie met patiënten zijn terug te vinden in de Landelijke Transmurale Afspraak antistollingszorg (https://lta-antistollingszorg.nl/communicatie-met-patienten).

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er is geen doorslaggevend verschil in de kosten voor de profylactisch of therapeutisch gedoseerde LMWH of ongefractioneerde heparine.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Door de opzet en uitkomsten van de onderzochte studies is geen definitief bewijs gevonden voor de cruciale uitkomsten. Het was volgens de werkgroep onzeker of het gebruik van therapeutische of intermediaire dosis antistolling tot een klinisch relevant verschil in cruciale uitkomsten zou leiden.

Rationale van de aanbeveling

De individuele studies rapporteerden vaak gecombineerde uitkomstmaten, waarbij (niet-invasieve) beademing, IC opnameduur, trombotische complicaties, ECMO, nierfunctievervangende therapie en sterfte in verschillende combinaties waren samengenomen. Bij de analyses van de individuele eindpunten bleek het voordeel van therapeutische antistolling onzeker te zijn of onder de van tevoren vastgestelde grens van klinische relevantie te liggen ten opzichte van een profylactische of intermediaire dosis antistolling. Ook bleek het voordeel van een intermediaire dosis antistolling onzeker te zijn of onder de van tevoren vastgestelde grens van klinische relevantie te liggen ten opzichte van een profylactische dosis antistolling. Eerder waren voor de Nederlandse situatie geen grenzen van klinische relevantie vastgesteld voor het instellen van tromboseprofylaxe. De werkgroep heeft zich bij het vaststellen van die grenzen geconformeerd aan de grenzen voor sterfte en IC opname, zoals vastgesteld door de werkgroep voor medicamenteuze behandeling van COVID-19. De grens voor een klinisch relevant verschil in trombotische complicaties werd indirect afgeleid uit de ACCP richtlijn tromboseprofylaxe uit 2012. Uit de onderzochte studies bleek ook dat therapeutische antistolling niet klinisch relevant meer schade berokkende dan een profylactische of intermediaire dosis: het optreden van bloedingen is mogelijk niet klinisch relevant verschillend tussen de groepen. De werkgroep kwam tot de conclusie dat er op grond van de onderzochte studies onvoldoende grond is om een therapeutische of een intermediair profylactische dosis antistolling te adviseren boven een standaard profylactische dosering antistolling voor patiënten met COVID-19 op de intensive care.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Ondanks tromboseprofylaxe en een verbeterde behandeling van COVID-19 komen trombotische complicaties nog frequent voor, met een geschatte incidentie van 23-28% in ICU patiënten en 7-9% in afdelingspatiënten (Jiménez, 2021; Tan, 2021; Nopp, 2021). Het is niet bekend wat de beste dosis van tromboseprofylaxe is (laag, intermediair of therapeutisch). Mede hierdoor verschillen ziekenhuisprotocollen.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Mortality

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with therapeutic dose of anticoagulation on mortality when compared to standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

Sources: Goligher, 2021; Lemos, 2020. |

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with intermediate dose of prophylactic anticoagulation on mortality when compared to standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

Source: Sadeghipour, 2021. |

2. Length of hospital or ICU stay

Length of hospital stay

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with therapeutic dose of anticoagulation on length of hospital stay when compared to standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

Sources: Lemos, 2020. |

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

- GRADE |

No studies were found that could answer the question what the effect is of intermediate dose of prophylactic anticoagulation when compared to standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation on length of hospital stay in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

|

Length of ICU stay

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with therapeutic dose of anticoagulation on length of ICU stay when compared to standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

Sources: Lemos, 2020. |

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with intermediate dose of prophylactic anticoagulation on length of ICU stay when compared to standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

Source: Sadeghipour, 2021. |

3. Organ support

Ventilator-free days

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with therapeutic dose of anticoagulation on ventilator-free days when compared to standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

Sources: Lemos, 2020. |

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with intermediate dose of prophylactic anticoagulation on ventilator-free days when compared to standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

Source: Sadeghipour, 2021. |

Other organ support free days

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

- GRADE |

No studies were found that could answer the question what the effect is of therapeutic dose of anticoagulation when compared to standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation on other organ support free days in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

|

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

- GRADE |

No studies were found that could answer the question what the effect is of intermediate dose of prophylactic anticoagulation when compared to standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation on other organ support free days in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

|

Organ support other than mechanical ventilation

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

- GRADE |

No studies were found that could answer the question what the effect is of therapeutic dose of anticoagulation when compared to standard prophylactic anticoagulation on organ support other than mechanical ventilation in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

|

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with intermediate dose of prophylactic anticoagulation on organ support other than mechanical ventilation when compared to standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

Source: Sadeghipour, 2021. |

4. Venous thromboembolism

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with therapeutic dose of anticoagulation on venous thromboembolism when compared to standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

Source: Goligher, 2021. |

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with intermediate dose of prophylactic anticoagulation on venous thromboembolism when compared to standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

Source: Sadeghipour, 2021. |

Thromboembolic complications (VTE/ATE)

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with therapeutic dose of anticoagulation may result in a decrease in thromboembolic complications (VTE/ATE) when compared to standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

Sources: Goligher, 2021. |

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with intermediate dose of prophylactic anticoagulation on thromboembolic complications (VTE/ATE) when compared to standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

Source: Sadeghipour, 2021. |

5. Major bleeding

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with therapeutic dose of anticoagulation may result in little to no difference in major bleedings when compared to standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

Sources: Goligher, 2021; Lemos, 2020; Spyropoulos, 2021. |

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with intermediate dose of prophylactic anticoagulation on major bleedings when compared to standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

Source: Sadeghipour, 2021. |

6. Heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT)

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

- GRADE |

No studies were found that could answer the question what the effect is of therapeutic dose of anticoagulation when compared to standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation on HIT in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

|

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

- GRADE |

No studies were found that could answer the question what the effect is of intermediate dose of prophylactic anticoagulation when compared to standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation on HIT in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

|

7.Cumulative transfusion

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

- GRADE |

No studies were found that could answer the question what the effect is of therapeutic dose of anticoagulation when compared to standard prophylactic (or intermediate) dose of anticoagulation on cumulative transfusion in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

|

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

|

- GRADE |

No studies were found that could answer the question what the effect is of intermediate dose of prophylactic anticoagulation when compared to standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation on cumulative transfusion in adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU.

|

Samenvatting literatuur

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Spyropoulos (2021) describes a multicenter open label randomized clinical trial evaluating the effects of therapeutic-dose low-molecular-weight heparin vs institutional standard or intermediate prophylactic dose heparins for thromboprophylaxis in high-risk hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Patients were enrolled from March 8, 2020, through May 14, 2021, at 12 centers in the US. A total of 11649 patients were assessed for eligibility. Eligible patients consisted of hospitalized nonpregnant adults 18 years or older with COVID-19 diagnosed by nasal swab or serologic testing. Moreover, there was a requirement for supplemental oxygen per investigator judgment and a plasma D-dimer level greater than 4 times the upper limit of normal based on local laboratory criteria or a sepsis-induced coagulopathy score of 4 or greater. 257 patients were randomized into the therapeutic heparin dose group (n= 130) or standard/intermediate prophylactic heparin dose group (n = 127). 45 out of 129 patients in the therapeutic dose group were admitted to the ICU, versus 38 out of 124 in the standard prophylactic dose group. Treatment began after randomization and was stopped at hospital discharge or upon occurrence of a primary efficacy outcome, key secondary outcome, or principal safety outcome requiring study drug discontinuation. All patients without a primary or key secondary outcome event underwent lower extremity Doppler compression ultrasonography at hospital day 10 + 4 or at discharge if sooner. The length of follow-up was 30 +2 days after randomization. For the primary efficacy outcome (venous thromboembolism, arterial thromboembolism or death) and major bleeding, patients were stratified based on intensive care unit (ICU) or non-ICU status. For all other outcomes, no stratification was performed. Patients in the therapeutic dose group had a mean age of 65.8 years (SD 13.9) versus 67.7 years (SD 14.1) in the standard prophylactic dose group and the small majority was male (52.7% in the intervention versus 54.8% in the control group). The study groups were comparable with respect to baseline characteristics.

Goligher (2021) describes an open-label, adaptive, multiplatform RCT (mpRCT). In this mpRCT, three platforms (REMAPCAP, ATTACC and ACTIV-4a) were integrated to evaluate therapeutic dose anticoagulation versus usual-care pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Patients were recruited from different countries, e.g. the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, Brazil. Patients were included in the mpRCT if they had a laboratory confirmed COVID-19 infection, they had severe COVID-19 (which was defined as COVID-19 that led to receipt of ICU-level respiratory or cardiovascular organ support in an ICU). A total of 1207 patients underwent randomization at 393 sites in 10 countries, until the pre-specified criterion for futility had been met. Patients were randomized to receive therapeutic dose anticoagulation with heparin (n=591) or usual-case thromboprophylaxis (n=616). After exclusion, 534 patients in the therapeutic dose group and 564 patients in the usual-care group were included in the primary analysis. The mean age of patients in the therapeutic dose group was 60.4 years (SD 13.1) versus 61.7 years (SD 12.5) in the usual-care group. The majority in both groups was male: 387 patients (72.2%) in the therapeutic dose group, versus 385 patients (67.9%) in the usual-care group. The study groups were comparable with respect to baseline characteristics.

Lemos (2020) describes a randomized, controlled, open-label, single-center, phase II study conducted in Brazil, evaluating therapeutic dose enoxaparin versus standard anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis in COVID-19 patients requiring mechanical ventilation. Adult patients (>18 years of age) were included in this study if they suffered from respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation and laboratory confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. Twenty patients were randomized to receive therapeutic enoxaparin (n=10) or prophylactic anticoagulation (UFH and LMWH, n=10). All patients who were randomized were included in the primary analysis. The mean age of patients in the therapeutic dose group was 55 years (SD 10) versus 58 years (SD 16) in the prophylactic dose group. The majority was male: nine out of ten patients in the therapeutic dose group, versus seven out of ten patients in the prophylactic dose group. The study groups were comparable with respect to baseline characteristics.

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Sadeghipour (2021) describes a multicenter open-label randomized clinical trial (INSPIRATION trial) comparing intermediate versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation in adult patients with COVID-19 admitted to the ICU. Patients were recruited between July 29, 2020, and November 19, 2020, conducted in Iran at 10 academic centers in Tehran and Tabriz. Patients were eligible if they were admitted to the ICU with polymerase chain reaction testing–confirmed COVID-19 within 7 days of the index hospitalization. Patients were excluded when their life expectancy was less than 24 hours. Also, patients with an established indication for therapeutic-dose anticoagulation, weight less than 40 kg, pregnancy, history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, platelet count less than 50 ×103 /μL, or overt bleeding were excluded. A total of 600 patients were randomized into the intermediate prophylactic dose group (n=299) or the standard dose prophylactic anticoagulation group (n=299). The primary anticoagulant agent in both groups was enoxaparin. In case a patient had severe kidney insufficiency, an unfractionated heparin was used. Treatments were continued until 30 days of follow-up, irrespective of hospital discharge status. Ultimately, 562 patients were included in the prespecified primary analysis. The median age of patients in the intermediate prophylactic dose group (n=276) was 62 years (IQR 51 to 70.7), versus 61 years (IQR 47 to 71) in the standard prophylactic dose group (n=286). The majority in both groups was male: 162 patients (58.7%) in the intermediate prophylactic dose group, versus 163 patients (57.0%) in the standard prophylactic dose group. Except for history of cigarette smoking, which was more frequent in the intermediate prophylactic dose group, the study groups were comparable with respect to baseline characteristics.

Bikdeli (2021) reports the final 90-day follow-up results of the INSPIRATION trial by Sadeghipour (2021). Therefore, the study design and included patients were the same as described above. The number of patients included in the primary analysis were not altered (n=276 in the intermediate prophylactic dose group versus n=286 in the standard prophylactic dose group). These articles are therefore taken together for the literature analysis.

Table 2. Overview of included RCTs that compared therapeutic dose anticoagulation with standard (or intermediate) dose anticoagulation and intermediate dose anticoagulation with standard dose anticoagulation in COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU

|

Author, year and trial name |

Intervention (I) and control (C) |

Sample size for analysis |

Doses |

Duration |

|

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation |

||||

|

Spyropoulos, 2021

HEP-COVID Randomized Clinical Trial |

I: therapeutic-dose low-molecular-weight heparin (enoxaparin)

C: institutional standard prophylactic or intermediate-dose heparins for thromboprophylaxis

|

I: N= 45 ICU admitted patients C: N= 38 ICU admitted patients Total = 83

|

I: 1 mg/kg subcutaneously twice daily if CrCl was 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 or greater or 0.5 mg/kg twice daily if CrCl was 15-29 mL/min/ 1.73 m2

C: could include unfractionated heparin (UFH), up to 22 500 IU subcutaneously (divided twice or thrice daily); enoxaparin, 30 mg or 40 mg subcutaneously once or twice daily (weight based enoxaparin 0.5 mg/kg subcutaneously twice daily was permitted but strongly discouraged); or dalteparin, 2500 IU or 5000 IU subcutaneously daily |

Study drug was administered for the duration of hospitalization, including patient transfers to ICU settings. |

|

Goligher, 2021

The REMAP-CAP, ACTIV-4a, and ATTACC Investigators |

I: therapeutic-dose anticoagulation with heparin

C: pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis in accordance with local usual care |

I: N= 534 C: N= 564 Total = 1098

|

I: Therapeutic-dose anticoagulation was administered according to local site protocols for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism

C: Usual-care thromboprophylaxis was administered at a dose and duration determined by the treating clinician according to local practice, which included either standard low-dose thromboprophylaxis or enhanced intermediate-dose thromboprophylaxis.

The anticoagulation and thromboprophylaxis regimens that were specified by each platform are detailed in the Supplementary Appendix (page 49-51 and Table S1 at page 65). |

I: Up to 14 days or until recovery (defined as either hospital discharge or discontinuation of supplemental oxygen for at least 24 hours).

C: Up to 14 days or hospital discharge, whichever comes first. After this period, decisions regarding thromboprophylaxis are at discretion of treating clinician

The trial was stopped when the prespecified criterion for futility was met for therapeutic-dose anticoagulation. |

|

Lemos, 2020

HESACOVID trial |

I: therapeutic enoxaparin

C: standard anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis |

I: N= 10 C: N= 10 Total = 20 |

I: subcutaneous (SC) enoxaparin with the dose according to age and adjusted daily by the creatinine clearance (CrCl) estimated by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation. See article for exact doses per age group.

C: subcutaneous unfractionated heparin (UFH) at a dose of 5000 IU TID (if weight < 120 kg) and 7500 IU TID (if weight > 120 kg) or enoxaparin at a dose of 40 mg OD (if weight < 120 kg) and 40 mg BID (if weight > 120 Kg) according to the doctor's judgment. |

I: The median of the therapeutic enoxaparin treatment duration was 14 days, ranging from 9 to 14 days

C: ? |

|

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation |

||||

|

INSPIRATION trial

Sadeghipour, 2021 (initial study)

Bikdeli, 2021 (extension of initial study/follow-up measurements at day 90) |

I: intermediate-dose enoxaparin

C: standard prophylactic anticoagulation enoxaparin |

I: N= 276 C: N= 286 Total = 562

|

I: 1 mg/kg daily, with modification according to body weight and creatinine clearance.

C: 40 mg daily, with modification according to body weight and creatinine clearance. |

Irrespectively of hospital discharge status, the assigned treatments were planned to be continued until the 30-day follow-up (Sadeghipour, 2021) or 90-day follow-up (Bikdeli, 2021).

|

Table 3. Overview of composite outcomes and results per study

|

Study |

Primary composite outcome |

Results |

|

INSPIRATION trial

|

Composite of adjudicated acute venous thromboembolism, arterial thrombosis, treatment with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or all-cause mortality. |

|

|

Goligher, 2021 Multiplatform trial |

Median number of days free of cardiovascular or respiratory organ support. This was evaluated on an ordinal scale that combined in-hospital death and the number of organ support free days up to day 21 among patients who survived to hospital discharge. If a patient died, they were assigned a value of -1.

|

In the therapeutic dose group, the median number of organ support-free days was 1 day (IQR -1 to 16), versus 4 days (IQR -1 to 16) in the standard prophylactic dose group. |

|

Spyropoulos, 2021 HEP-COVID trial |

Composite outcome: VTE, ATE, or death Measured in the ICU-stratum |

Therapeutic dose group: 23 out of 45 (51.1%) patients Standard prophylactic dose group: 21 out of 38 (55.3%) patients |

Results

1. Mortality

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Goligher (2021) reported death in hospital. A total of 199 out of 534 (37.3%) patients died in the therapeutic dose group, versus 200 out of 564 (35.5%) in the standard prophylactic dose group. The risk difference (RD) was 1.8% in favor of the standard prophylactic dose group (95%CI -3.9% to 7.5%). The corresponding NNT was 56. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Lemos (2020) reported in-hospital mortality. A total of 2 out of 10 (20.0%) patients died in the therapeutic dose group, versus 5 out of 10 (50.0%) in the standard prophylactic dose group. The RD was 30.0% in favor of the therapeutic dose group (95%CI -69.7% to 9.7%). The corresponding NNT was 3. This was considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality was downgraded from high to very low because in Goligher (2021) some patients are missing from the analyses and it is not clear why, and many patients were excluded after randomization in both groups (risk of bias, -1), and the confidence interval around the RD crossing the upper and lower thresholds for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2). Lemos (2020) was given few weight in the determination of the level of evidence, because of the very small study population.

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Sadeghipour (2021) reported all-cause mortality at day 30. In the intermediate prophylactic dose group, 119 out of 276 (43.1%) patients died, versus 117 out of 286 (40.9%) patients in the standard prophylactic dose group. The RD was 2.2% in favor of the standard prophylactic dose group (95%CI -6.0% to 10.4%). The corresponding NNT was 45. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

At day 90, Bikdeli (2021) reported that 127 out of 276 (46.0%) patients died, versus 123 out of 286 (43.0%) patients in the standard prophylactic dose group.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality was downgraded from high to very low because of the study population differing from what was defined in the PICO (indirectness, -1), the confidence interval around the RD crossing the upper and lower thresholds for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence is based on the results reported in Sadeghipour (2021).

2. Length of hospital or ICU stay

Length of hospital stay

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Lemos (2020) reported the median length of hospital stay. The median length of hospital stay was 31 days (IQR 22 to 35) in the therapeutic dose group, versus 30 days (IQR 23 to 38) in the standard prophylactic dose group. The difference in median days was 1 day. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Goligher (2021) did not report length of hospital stay.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure length of hospital stay was downgraded from high to very low because of the small sample size and wide interquartile range (imprecision, -3).

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Sadeghipour (2021) and Bikdeli (2021) did not report length of hospital stay.

Length of ICU stay

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Lemos (2020) also reported the median number of ICU-free days. This was 12 days (IQR 2 to 12) in the therapeutic dose group, versus 0 days (IQR 0 to 10) in the standard prophylactic dose group.

Goligher (2021) did not report length of ICU stay.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure length of ICU stay was downgraded from high to very low because of the outcome measure not being the same as defined in the PICO (indirectness, -1), and the small sample size and wide interquartile range (imprecision, -2).

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Sadeghipour (2021) reported the median length of ICU stay. The median length of ICU stay for the intermediate prophylactic dose group was 5 days (IQR 2 to 10), versus 6 days (IQR 3 to 11) in the standard prophylactic dose group. The difference in median days was 1 day. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Sadeghipour (2021) also reported the number of patients discharged from the ICU. The number of patients discharged from the ICU in the intermediate prophylactic dose group was 169 out of 276 (61.2%), versus 174 out of 286 (60.8%) in the standard prophylactic dose group.

Bikdeli (2021) did not report length of ICU stay at day 90.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure length of ICU stay was downgraded from high to very low because of the study population differing from what was defined in the PICO (indirectness, -1), and the wide interquartile range in both groups (imprecision, -2).

3. Organ support free days

Ventilator-free days

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Lemos (2020) reported the median number of ventilator-free days. In the therapeutic dose group, the median number of ventilator-free days was 15 days (IQR 6 to 16), versus 0 days (IQR 0 to 11) in the standard prophylactic dose group.

Goligher (2021) did not report ventilator-free days.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ventilator-free days was downgraded from high to very low because of the small sample size and the wide interquartile range in both groups (imprecision, -3).

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Sadeghipour (2021) reported the median number of ventilator-free days. In the intermediate prophylactic dose group, the median number of ventilator-free days was 30 days (IQR 3 to 30), versus 30 days (IQR 1 to 30) in the standard prophylactic dose group. The difference in median days was zero days. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Bikdeli (2021) did not report ventilator-free days at day 90.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ventilator-free days was downgraded from high to very low because of the study population differing from what was defined in the PICO (indirectness, -1), and the wide interquartile range in both groups (imprecision, -2).

Other organ support free days

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Goligher (2021) and Lemos (2020) did not report on other organ support free days.

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Sadeghipour (2021) and Bikdeli (2021) did not report on other organ support free days.

Organ support other than mechanical ventilation

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Goligher (2021) and Lemos (2020) did not report on other organ support than mechanical ventilation.

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Sadeghipour (2021) and Bikdeli (2021) reported extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) as part of the primary composite outcome (see Table 2), but not on its own. In addition, Sadeghipour (2021) reported new in-hospital kidney replacement therapy. In the intermediate prophylactic dose group, 10 out of 276 (3.6%) patients needed kidney replacement therapy, versus 7 out of 286 (2.4%) patients in the standard prophylactic dose group. The difference was 1.2% in favor of the standard prophylactic dose group (95%CI -1.7% to 4.0%). This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference. Bikdeli (2021) reported the same numbers at day 90.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure organ support other than mechanical ventilation was downgraded from high to very low because of the study population differing from what was defined in the PICO (indirectness, -1), and the low number of events (imprecision, -2).

4. Venous thromboembolism

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Goligher (2021) and Lemos (2020) did not report the number of patients with VTE.

However, Goligher (2021) did report the number of events for deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism separately. In the therapeutic dose group 6 events for deep venous thrombosis were reported, versus 6 events in the standard prophylactic dose group. For pulmonary embolism, 13 events were reported in the therapeutic dose group, versus 42 events in the standard prophylactic dose group.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure venous thromboembolism was downgraded from high to very low because in Goligher (2021) some patients are missing from the analyses and it is not clear why, and many patients were excluded after randomization in both groups (risk of bias, -1), indirectness in the outcome measure (indirectness, -1), the low number of events (imprecision, -1).

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Sadeghipour (2021) reported adjudicated venous thromboembolism at day 30. In the intermediate prophylactic dose group 9 out of 276 patients (3.3%) developed adjudicated venous thromboembolism, versus 10 out of 286 (3.5%) in the standard prophylactic dose group. The RD was 0.24% in favor of the intermediate prophylactic dose group (95%CI -3.2% to 2.8%). The NNT was 417. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Bikdeli (2021) reported the same outcome in the same patients at day 90. No differences occurred in the incidence between day 30 and 90.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure venous thromboembolism was downgraded from high to very low because of the open-label study design (risk of bias, -1), the study population differing from what was defined in the PICO (indirectness, -1), and the confidence interval around the RD crossing the lower threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1).

Thromboembolic complications (VTE/ATE)

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Goligher (2021) reported the number of patients with any thrombotic event (defined as pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, ischemic cerebrovascular event, systemic arterial thromboembolism): 38 out of 530 patients (7.2%) experienced a thrombotic event in the therapeutic dose group, versus 62 out of 559 patients (11.1%) in the standard prophylactic dose group. The RD was 3.9% in favor of the therapeutic dose group (95%CI -7.3% to 0.5%). The corresponding NNT was 26. This was considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Lemos (2020) reported the number of patients with thrombotic events: 2 out of 10 (2.0%) patients experienced a thrombotic event in the therapeutic dose group, versus 2 out of 10 (2.0%) patients in the standard prophylactic dose group. The RD was 0.0% (95%CI -35.1% to 35.1%). This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure thromboembolic complications was downgraded from high to low because in Goligher (2021) some patients are missing from the analyses and it is not clear why, and many patients were excluded after randomization in both groups (risk of bias, -1), and the confidence interval around the RD crossing the lower threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). Lemos (2020) was given no weight in the determination of the level of evidence, because of the very small study population.

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Sadeghipour (2021) and Bikdeli (2021) did not report the number of patients with thromboembolic events (VTE/ATE).

However, Sadeghipour (2021) reported the number of patients with acute peripheral arterial thrombosis, ischemic stroke, and type I acute myocardial infarction, all three objectively clinically diagnosed. None of the 276 patients in the intermediate prophylactic dose group and none of the 286 patients in the standard prophylactic dose group were diagnosed with acute peripheral arterial thrombosis and/or type I acute myocardial infarction. In the intermediate prophylactic dose group, 1 out of 276 (0.4%) patients developed ischemic stroke, versus 1 out of 286 (0.3%) patients in the standard prophylactic dose group.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure thromboembolic complications was downgraded from high to very low because of the open-label study design (risk of bias, -1), indirectness in the outcome measure and study population (indirectness, -1), and the low number of events (imprecision, -1).

5. Major bleeding

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

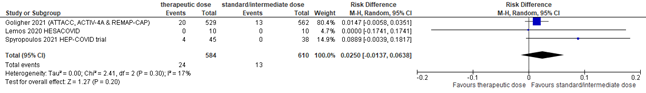

Figure 1: Major bleeding in COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

A total of 24 out of 584 (4.1%) patients developed a major bleeding in the therapeutic dose group, versus 13 out of 610 (2.1%) in the standard/intermediate prophylactic dose group. The pooled risk difference (RD) was 2.5% in favor of the standard/intermediate prophylactic dose group (95%CI -1.4% to 6.4%; figure 1). The corresponding NNH was 40. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure major bleeding was downgraded from high to low because in Goligher (2021) some patients are missing from the analyses and it is not clear why, and many patients were excluded after randomization in both groups (risk of bias, -1), and the confidence interval around the RD crossing the upper threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1).

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Sadeghipour (2021) reported major bleeding. In the intermediate prophylactic dose group 7 out of 276 (2.5%) patients developed a major bleeding, versus 4 out of 286 (1.4%) patients in the standard prophylactic dose group. The RD was 1.14% in favor of the standard prophylactic dose group (95%CI -1.16% to 3.44%). The corresponding NNH was 88. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference. Bikdeli (2021) reports the same numbers at day 90.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure major bleeding was downgraded from high to very low because of the open-label study designs (risk of bias, -1), the study population differing from what was defined in the PICO (indirectness, -1), and the confidence interval around the RD crossing the upper threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1).

6. Heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT)

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Goligher (2021) and Lemos (2020) did not report HIT.

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Sadeghipour (2021) and Bikdeli (2021) did not report HIT.

7. Cumulative transfusion

Therapeutic dose versus standard (or intermediate) dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Goligher (2021) and Lemos (2020) did not report cumulative transfusion.

Intermediate dose versus standard dose of prophylactic anticoagulation

Sadeghipour (2021) and Bikdeli (2021) did not report cumulative transfusion.

However, Sadeghipour (2021) reported a sub-category of major bleeding: ‘BARC Type 3a- hemoglobin drop of 3 to 5 g/dL or any transfusion’. In the intermediate prophylactic dose group, 3 out of 276 (1.1%) patients reported this outcome, versus 4 out of 286 (1.4%) patients in the standard prophylactic dose group. Bikdeli (2021) reported the same numbers at day 90.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the efficacy and safety of anticoagulation therapy in COVID-19 patients at the ICU?

PICO 1

P: all adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU who are not already on chronic therapeutic anticoagulants

I: therapeutic dose (low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, vitamin K-antagonists, aspirin)

C: standard or intermediate prophylactic dose (low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, vitamin K-antagonists, aspirin) or no use of standard or intermediate prophylactic dose (low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, vitamin K-antagonists, aspirin)

O: mortality, major bleeding, venous thromboembolism, thromboembolic complications, length of hospital or ICU stay, organ support (ventilator-free days, other organ support free days, and organ support other than mechanical ventilation), heparin induced thrombocytopenia, and cumulative transfusion

PICO 2

P: all adult COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU who are not already on chronic therapeutic anticoagulants

I: intermediate prophylactic dose (low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, vitamin K-antagonists, aspirin)

C: standard prophylactic dose (low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, vitamin K-antagonists, aspirin) or no use of standard or intermediate prophylactic dose (low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, vitamin K-antagonists, aspirin)

O: mortality, major bleeding, venous thromboembolism, thromboembolic complications, length of hospital or ICU stay, organ support (ventilator-free days, other organ support free days, and organ support other than mechanical ventilation), heparin induced thrombocytopenia, and cumulative transfusion

We searched for standard dose of prophylaxis and intermediate dose of prophylaxis; the latter is typically a doubling of the standard dose of prophylaxis. We also searched for a therapeutic dose of prophylaxis (intensive dose of prophylaxis; referred to as therapeutic dose). For aspirin only one dose (80-100 mg per day) was searched.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered mortality, ventilator-free days, venous thromboembolism, thromboembolic complications (venous and arterial thrombotic complications combined) and major bleeding as critical outcome measures for decision making; and length of hospital or ICU stay, other organ support free days, organ support other than mechanical ventilation, heparin induced thrombocytopenia, and cumulative transfusion as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined a risk difference of 3% as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for mortality, venous thromboembolism, thromboembolic complications (venous and arterial thrombotic complications combined) and major bleeding; 3 days for length of hospital(/ICU) stay, ventilator-free days, and other organ support free days; a risk difference of 5% for organ support other than mechanical ventilation (yes/no), an absolute risk difference of 0.5 % for heparin induced thrombocytopenia; and an absolute risk difference of 10% for cumulative transfusion.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until October 18th 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 686 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- randomized controlled trial (RCT)

- peer reviewed and published in indexed journal or pre-published

- comparing treatment with

- a therapeutic dose of anticoagulant (low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, vitamin K-antagonists, aspirin) with a prophylactic dose or no dose of anticoagulant (low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, vitamin K-antagonists, aspirin)

- an intermediate prophylactic dose of anticoagulant (low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, vitamin K-antagonists, aspirin) with a standard prophylactic dose or no dose of anticoagulant (low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, direct oral anticoagulants, vitamin K-antagonists, aspirin)

- in critically ill patients with COVID-19 admitted to the ICU.

Fourteen studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, nine studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and five studies were included.

Results

Five studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Three studies investigated a therapeutic dose anticoagulant versus standard (or intermediate) prophylactic dose anticoagulant in COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU (PICO 1). One study (for which different follow-up times – day 30 and day 90 – are described in two articles) investigated an intermediate prophylactic dose anticoagulant versus standard prophylactic dose anticoagulant in COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU (PICO 2). No subgroups were made based on the type of anticoagulant used, as all studies used a heparin. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Bikdeli B, Talasaz AH, Rashidi F, Bakhshandeh H, Rafiee F, Rezaeifar P, Baghizadeh E, Matin S, Jamalkhani S, Tahamtan O, Sharif-Kashani B, Beigmohammadi MT, Farrokhpour M, Sezavar SH, Payandemehr P, Dabbagh A, Moghadam KG, Khalili H, Yadollahzadeh M, Riahi T, Abedini A, Lookzadeh S, Rahmani H, Zoghi E, Mohammadi K, Sadeghipour P, Abri H, Tabrizi S, Mousavian SM, Shahmirzaei S, Amin A, Mohebbi B, Parhizgar SE, Aliannejad R, Eslami V, Kashefizadeh A, Dobesh PP, Kakavand H, Hosseini SH, Shafaghi S, Ghazi SF, Najafi A, Jimenez D, Gupta A, Madhavan MV, Sethi SS, Parikh SA, Monreal M, Hadavand N, Hajighasemi A, Maleki M, Sadeghian S, Piazza G, Kirtane AJ, Van Tassell BW, Stone GW, Lip GYH, Krumholz HM, Goldhaber SZ, Sadeghipour P. Intermediate-Dose versus Standard-Dose Prophylactic Anticoagulation in Patients with COVID-19 Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit: 90-Day Results from the INSPIRATION Randomized Trial. Thromb Haemost. 2021 Apr 17. doi: 10.1055/a-1485-2372. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33865239.

- REMAP-CAP Investigators; ACTIV-4a Investigators; ATTACC Investigators, Goligher EC, Bradbury CA, McVerry BJ, Lawler PR, Berger JS, Gong MN, Carrier M, Reynolds HR, Kumar A, Turgeon AF, Kornblith LZ, Kahn SR, Marshall JC, Kim KS, Houston BL, Derde LPG, Cushman M, Tritschler T, Angus DC, Godoy LC, McQuilten Z, Kirwan BA, Farkouh ME, Brooks MM, Lewis RJ, Berry LR, Lorenzi E, Gordon AC, Ahuja T, Al-Beidh F, Annane D, Arabi YM, Aryal D, Baumann Kreuziger L, Beane A, Bhimani Z, Bihari S, Billett HH, Bond L, Bonten M, Brunkhorst F, Buxton M, Buzgau A, Castellucci LA, Chekuri S, Chen JT, Cheng AC, Chkhikvadze T, Coiffard B, Contreras A, Costantini TW, de Brouwer S, Detry MA, Duggal A, Džavík V, Effron MB, Eng HF, Escobedo J, Estcourt LJ, Everett BM, Fergusson DA, Fitzgerald M, Fowler RA, Froess JD, Fu Z, Galanaud JP, Galen BT, Gandotra S, Girard TD, Goodman AL, Goossens H, Green C, Greenstein YY, Gross PL, Haniffa R, Hegde SM, Hendrickson CM, Higgins AM, Hindenburg AA, Hope AA, Horowitz JM, Horvat CM, Huang DT, Hudock K, Hunt BJ, Husain M, Hyzy RC, Jacobson JR, Jayakumar D, Keller NM, Khan A, Kim Y, Kindzelski A, King AJ, Knudson MM, Kornblith AE, Kutcher ME, Laffan MA, Lamontagne F, Le Gal G, Leeper CM, Leifer ES, Lim G, Gallego Lima F, Linstrum K, Litton E, Lopez-Sendon J, Lother SA, Marten N, Saud Marinez A, Martinez M, Mateos Garcia E, Mavromichalis S, McAuley DF, McDonald EG, McGlothlin A, McGuinness SP, Middeldorp S, Montgomery SK, Mouncey PR, Murthy S, Nair GB, Nair R, Nichol AD, Nicolau JC, Nunez-Garcia B, Park JJ, Park PK, Parke RL, Parker JC, Parnia S, Paul JD, Pompilio M, Quigley JG, Rosenson RS, Rost NS, Rowan K, Santos FO, Santos M, Santos MO, Satterwhite L, Saunders CT, Schreiber J, Schutgens REG, Seymour CW, Siegal DM, Silva DG Jr, Singhal AB, Slutsky AS, Solvason D, Stanworth SJ, Turner AM, van Bentum-Puijk W, van de Veerdonk FL, van Diepen S, Vazquez-Grande G, Wahid L, Wareham V, Widmer RJ, Wilson JG, Yuriditsky E, Zhong Y, Berry SM, McArthur CJ, Neal MD, Hochman JS, Webb SA, Zarychanski R. Therapeutic Anticoagulation with Heparin in Critically Ill Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021 Aug 26;385(9):777-789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2103417. Epub 2021 Aug 4. PMID: 34351722; PMCID: PMC8362592

- Jiménez D, García-Sanchez A, Rali P, Muriel A, Bikdeli B, Ruiz-Artacho P, Le Mao R, Rodríguez C, Hunt BJ, Monreal M. Incidence of VTE and Bleeding Among Hospitalized Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Chest. 2021 Mar;159(3):1182-1196. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.11.005. Epub 2020 Nov 17. PMID: 33217420; PMCID: PMC7670889.

- Lemos ACB, do Espírito Santo DA, Salvetti MC, Gilio RN, Agra LB, Pazin-Filho A, Miranda CH. Therapeutic versus prophylactic anticoagulation for severe COVID-19: A randomized phase II clinical trial (HESACOVID). Thromb Res. 2020 Dec;196:359-366. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.09.026. Epub 2020 Sep 21. PMID: 32977137; PMCID: PMC7503069.

- Nopp S, Moik F, Jilma B, Pabinger I, Ay C. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020 Sep 25;4(7):1178–91. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12439. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33043231; PMCID: PMC7537137.

- INSPIRATION Investigators, Sadeghipour P, Talasaz AH, Rashidi F, Sharif-Kashani B, Beigmohammadi MT, Farrokhpour M, Sezavar SH, Payandemehr P, Dabbagh A, Moghadam KG, Jamalkhani S, Khalili H, Yadollahzadeh M, Riahi T, Rezaeifar P, Tahamtan O, Matin S, Abedini A, Lookzadeh S, Rahmani H, Zoghi E, Mohammadi K, Sadeghipour P, Abri H, Tabrizi S, Mousavian SM, Shahmirzaei S, Bakhshandeh H, Amin A, Rafiee F, Baghizadeh E, Mohebbi B, Parhizgar SE, Aliannejad R, Eslami V, Kashefizadeh A, Kakavand H, Hosseini SH, Shafaghi S, Ghazi SF, Najafi A, Jimenez D, Gupta A, Madhavan MV, Sethi SS, Parikh SA, Monreal M, Hadavand N, Hajighasemi A, Maleki M, Sadeghian S, Piazza G, Kirtane AJ, Van Tassell BW, Dobesh PP, Stone GW, Lip GYH, Krumholz HM, Goldhaber SZ, Bikdeli B. Effect of Intermediate-Dose vs Standard-Dose Prophylactic Anticoagulation on Thrombotic Events, Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Treatment, or Mortality Among Patients With COVID-19 Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit: The INSPIRATION Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021 Apr 27;325(16):1620-1630. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.4152. PMID: 33734299; PMCID: PMC7974835.

- Spyropoulos AC, Goldin M, Giannis D, Diab W, Wang J, Khanijo S, Mignatti A, Gianos E, Cohen M, Sharifova G, Lund JM, Tafur A, Lewis PA, Cohoon KP, Rahman H, Sison CP, Lesser ML, Ochani K, Agrawal N, Hsia J, Anderson VE, Bonaca M, Halperin JL, Weitz JI; HEP-COVID Investigators. Efficacy and Safety of Therapeutic-Dose Heparin vs Standard Prophylactic or Intermediate-Dose Heparins for Thromboprophylaxis in High-risk Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19: The HEP-COVID Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2021 Dec 1;181(12):1612-1620. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.6203. PMID: 34617959; PMCID: PMC8498934.

- Tan BK, Mainbourg S, Friggeri A, Bertoletti L, Douplat M, Dargaud Y, Grange C, Lobbes H, Provencher S, Lega JC. Arterial and venous thromboembolism in COVID-19: a study-level meta-analysis. Thorax. 2021 Oct;76(10):970-979. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215383. Epub 2021 Feb 23. PMID: 33622981; PMCID: PMC7907632.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size

|

Comments |

|

Spyropoulos, 2021

HEP-COVID Randomized Clinical Trial

AND

corresponding Trial protocol design paper (Goldin, 2021) |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial

Setting and country: Multicenter study in the US (12 centers)

Funding and conflicts of interest: Support from Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, the Broxmeyer Fellowship in Clinical Thrombosis, and grant R24AG064191 from the National Institute on Aging. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Patients were stratified into two subgroups: non-intensive care unit patients and intensive care unit patients. ICU status was defined by mechanical ventilation, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation or high-flow nasal cannula, vasopressors, or vital sign monitoring more often than every 4 hours. ICU: 83 patients (32.8%) Non-ICU: 170 patients (67.2%)

N total at baseline: N = 257 participants randomized (130 to the intervention group and 127 to the control group) at baseline.

Important prognostic factors2:

Age, mean (SD): I: 65.8 (13.9) C: 67.7 (14.1)

Sex, No./total No. (%) male I: 68/129 (52.7%) C: 68/124 (54.8%)

BMI, mean (SD) I: 31.2 (9.3) C: 29.8 (13.6)

Race and ethnicity, No. (%) (I/C) Asian 11 (8.5) / 14 (11.3) Black 33 (25.6) / 37 (29.8) White 56 (43.4) / 46 (37.1) Multiracial/unknown 29 (22.5) / 27 (21.8)

ICU, No./total No. (%) I: 45/129 (34.9) C: 38/124 (30.6)

Comorbidities, No./total No. (%) (I/C) Hypertension 81/129 (62.8) / 70/123 (56.9) Heart failure 0 / 2/124 (1.6) Diabetes mellitus 51/128 (39.8) / 43/124 (34.7) Dyslipidemia 48/129 (37.2) / 39/124 (31.5) Coronary artery disease 7/129 (5.4) / 11/124 (8.9) Valvular heart disease 1/129 (0.8) / 3/124 (2.4) History of ischemic stroke 5/129 (3.9) / 3/124 (2.4) History of carotid occlusive disease 0 / 0 Peripheral artery disease 4/129 (3.1) / 1/124 (0.8) Chronic kidney disease 5/129 (3.9) / 4/124 (3.2) Chronic lung disease 9/129 (7.0) / 8/124 (6.5) Chronic liver disease/cirrhosis 2/129 (1.6) / 1/124 (0.8) Pulmonary hypertension 1/127 (0.8) / 2/124 (1.6)

VTE risk factors, , No./total No. (%) (I/C) Personal history of VTE 6/129 (4.7) / 2/124 (1.6) History of cancer 16/129 (12.4) / 10/124 (8.1) Active cancer 1/129 (0.8) / 4/124 (3.2) Autoimmune disease 1/128 (0.8) / 2/124 (1.6) Hormonal therapy/oral contraceptives 1/129 (0.8) / 1/124 (0.8) Known thrombophilia 0 / 0 Recent stroke with paresis 1/129 (0.8) / 1/124 (0.8)

Clinical scores, mean (SD) (I/C) IMPROVEDD VTE risk score 4.33 (1.48) / 4.22 (1.36) Sepsis-induced coagulopathy score 2.35 (0.73) / 2.31 (0.85)

Laboratory parameters, mean (SD) (I/C) White blood cell count, /μL 9600 (5800) / 9800 (8200) Platelets, ×103/μL 287.7 (119.8) / 269.7 (108.2) Serum creatinine, mg/dL 0.94 (0.45) / 1.00 (0.50) Prothrombin time, s 13.5 (1.6) /13.6 (2.6) D-dimer, ng/mL 3837 (6166) / 3183 (5409)

Medications prior to randomization, No./total No. (%)(I/C) Low-molecular-weight heparin 106/128 (82.8) / 97/124 (78.2) Unfractionated heparin 18/127 (14.2) / 23/121 (19.0) Remdesivir 93/129 (72.1) / 85/124 (68.6) Glucocorticoids 111/127 (87.4) / 93/123 (75.6) Antiplatelets 40/129 (31.0) / 24/124 (19.4)

Oxygen therapy, No./total No. (%) (I/C) Nasal cannula 80/129 (62.0) / 83/124 (66.9) Nonrebreather mask 12/129 (9.3) / 11/124 (8.9) Ventilation mask 4/129 (3.1) / 2/124 (1.6) High-flow or noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation 20/129 (15.5) / 19/124 (15.3) Invasive mechanical ventilation 8/129 (6.2) / 5/124 (4.0)

Length of hospital stay, mean (SD), d I: 12.2 (9.3)

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Patients in the therapeutic dose group received enoxaparin at a dose of 1 mg/kg subcutaneously twice daily if CrCl was 30 L/min/1.73m2 or greater or 0.5 mg/kg twice daily if CrCl was 15-29 mL/min/1.73m2. Study drug was administered for the duration of hospitalization, including patient transfers to ICU settings.

Study protocol (Goldin, 2021): Individual dose modification is not permitted unless the CrCl falls below 15 mL/min in the treatment arm (arm 0). In that case, conversion to dose-adjusted intravenous (IV) UFH is acceptable. The investigator is encouraged to convert back to treatment-dose enoxaparin as per protocol once the CrCl returns to values higher than or equal to 15 mL/min.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Patients in the standard-dose group received prophylactic or intermediate-dose heparin regimens per local institutional standard and could include UFH, up to 22500 IU subcutaneously (divided twice or thrice daily); enoxaparin, 30 mg or 40 mg subcutaneously once or twice daily (weight based enoxaparin 0.5mg/kg subcutaneously twice daily was permitted but strongly discouraged); or dalteparin, 2500 IU or 5000 IU subcutaneously daily. If CrCl fell below15 mL/min/ 1.73 m2, enoxaparin was converted to treatment-dose intravenous UFH until kidney function improved to CrCl greater than 15 mL/min/1.73 m2, when blinded-dose subcutaneous enoxaparin was resumed. Study drug was administered for the duration of hospitalization, including patient transfers to ICU settings. In the standarddose group, 76 patients (61.3%) received prophylactic doses of heparin (enoxaparin, ≤40mg daily), while 48 patients (38.7%) received intermediate doses of heparin (enoxaparin, 30 mg twice daily, 3 patients [2.4%]; enoxaparin, 40mg twice daily, 43 patients [34.7%]; enoxaparin, 0.5mg/kg twice daily, 2 patients [1.6%]).

Goldin, 2021: Dose modification is allowed in the prophylactic/intermediate group (arm 1) if the CrCl falls below15 mL/min so that UFH up to 22,500 U daily (i.e., UFH 5,000 U SQ BID or TID or 7,500 IU SQ BID or TID) can be used. The investigator is encouraged to convert back to prophylactic-/intermediate dose LMWH/UFH as per protocol once the CrCl returns to values higher than or equal to 15 mL/min. |

Length of follow-up: Until 30 + 2 days after randomization.

Loss-to-follow-up: 4 patients did not receive study drug (2 withdrew consent and 2 reached end points prior to the first dose). That resulted in 253 patients in the modified intention-to-treat population for analysis: Intervention: 129 Control: 124

The primary analysis was based on the modified intention to-treat population, followed by the per-protocol population.

|

Clinical Outcomes During the 30-Day, stratified for ICU and non-ICU:

Mortality Not reported

Length of hospital stay Not reported

ICU-admission Not reported

Organ support free days Not reported

Venous thromboembolism Not reported

Major bleeding I: 4/45 (8.9) C: 0 RR (95% CI): 7.62 (0.42-137.03)

Non-ICU patients: I: 2/84 (2.4) C: 2/86 (2.3) RR (95% CI): 1.02 (0.15-7.10)

|

Author’s conclusions: Therapeutic dose LMWH reduced the composite of thromboembolism and death compared with standard heparin thromboprophylaxis without increased major bleeding among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 with very elevated D-dimer levels. The treatment effect was not seen in ICU patients. |

|

Sadeghipour, 2021

INSPIRATION trial – initial study |

Type of study: Open-label RCT [multicenter]

Setting: 10 academic centers in Tehran and Tabriz; recruitment: July 29, 2020, and Nov 19, 2020. Final follow-up date for 30-day primary outcome: Dec 19, 2020

Country: Iran

Source of funding: “The study was funded by the Rajaie Cardio-vascular Medical and Research Center. Some study authors, including the lead author, are affiliated with the Rajaie Cardio-vascular Medical and Research Center. Enoxaparin was provided through Alborz Darou, Pooyesh Darou, and Caspian Pharmaceuticals companies, and atorvastatin and matching placebo was provided by Sobhan Darou. None of these companies were study sponsors.”

|

COVID-19 patients admitted to ICU, within 7 days of hospitalization

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: N = 600 randomized, after eligibility check and consent; n=566 Intervention: 280 (276 included in primary analysis) Control: 286 (286 included in primary analysis)

Important characteristics: Age, median (IQR: I: 62 (51-70.7) y C: 61 (47-71) y Sex, n/N (%) male: I: 162/276 (58.7%) C: 163/286 (57.0%)

Duration of symptoms prior to hospitalization, d, median (IQR) I: 7 (4-8) C: 7 (5-10)

Duration of hospitalization before randomization, d, median (IQR) I: 4 (2-6) C: 4 (3-6)

Baseline indicators of illness severity, No. (%) Patients with systolic blood pressure <100mmHg at the time of randomization I: 25/276 (9.0%) C: 33/286 (11.5%)

Vasopressor agent support within 72 h of enrolment I: 63/276 (22.8%) C: 64/286 (22.3%)

Fraction of inspired oxygen >50% at the time of randomization I: 112/276 (40.5%) C: 122/286 (42.6%)

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score at the time of randomization I: median 8 (IQR 5-11) C: median 8 (IQR 5-11)

Acute respiratory support, No. (%) Nasal cannula I: 10/276 (3.6%) C: 14/286 (4.9%)

Face mask I: 33/276 (12.0%) C: 27/286 (9.4%)

Reservoir mask I: 76/276 (27.5%) C: 96/286 (33.6%)

High-flow nasal cannula I: 9/276 (3.3%) C: 6/286 (2.1%)

Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation I: 93/276 (33.7%) C: 85/286 (29.7%)

Invasive positive pressure ventilation (endotracheal intubation) I: 55/276 (19.9%) C: 58 (20.3%)

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, expect for history of cigarette smoking, which was more frequent in the intermediate dose group. |

Intermediate-dose Prophylactic Anticoagulation

Enoxaparin, 1mg/kg daily)

|

Standard-dose Prophylactic Anticoagulation

Enoxaparin, 40mg daily |

Length of follow up: 30 days

Not included in follow-up: I: 4/280 (1.4%) Reasons: ‘did not receive at least 1 dose of the assigned treatment’ C: 0/286 (0%)

|

Clinical outcomes at 30 days follow-up

Mortality All-cause mortality, 30 days I: 119/276 (43.1%) C: 117/286 (40.9%) Diff 2.2 (−5.9 to 10.3) OR 1.09 (0.78 to 1.53) P=0.50

Length of ICU stay ICU length of stay, median (IQR) I: 5 (2-10) C: 6 (3-11)

Patients discharged from the ICU, n/total (%) I: 169 / 276 (61.2%) C: 174 / 286 (60.8%)

Organ support free days Ventilator-free days, median (IQR) I: 30 (3 to 30) C: 30 (1 to 30)

New in-hospital kidney replacement therapy, n (%) I: 10 out of 276 (3.6%) patients C: 7 out of 286 (2.4%) patients

Venous thromboembolism Adjudicated venous thromboembolism, n/total (%) I: 9 / 276 (3.3%) C: 10 / 286 (3.5%)

Objectively clinically diagnosed acute peripheral arterial thrombosis I: 0 / 276 C: 0 / 286

Objectively clinically diagnosed stroke, n/total (%) I: 1/276 (0.4%) C: 1/286 (0.3%)

Objectively clinically diagnosed type I acute myocardial infarction, n/total I: 0/276 C: 0/286

Major bleeding*, n/total (%) I: 7/276 (2.5%) C: 4/286 (1.4%) |

Definitions: Definitions of outcome Events are described in the study protocol

Remarks: * Major bleeding consisted of Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 3 and 5, which defines type 3a as overt bleeding plus hemoglobin drop of 3 to 5 g/dL or any transfusion with overt bleeding; type 3b as overt bleeding plus hemoglobin drop 5 g/dL, cardiac tamponade, or bleeding requiring surgical intervention for control; type 3c as intracranial hemorrhage; and type 5 as fatal bleeding

Authors conclusion: Among patients admitted to the ICU with COVID-19, intermediate-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, compared with standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, did not result in a significant difference in the primary outcome of a composite of adjudicated venous or arterial thrombosis, treatment with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or mortality within 30 days. These results do not support the routine empirical use of intermediate-dose prophylactic anticoagulation in unselected patients admitted to the ICU with COVID-19.

|

|

Bikdeli, 2021

INSPIRATION trial – extension 90 days follow-up of Sadeghipour (2021)(follow-up 30 days) |

See Sadeghipour (2021) |

See Sadeghipour (2021) |

See Sadeghipour (2021) |

See Sadeghipour (2021) |

Length of follow up: 90 days

90-day outcome data were available for all 562 participants.

Not included in follow-up See Sadeghipour (2021)

|

Clinical outcomes at 90 days follow-up

Mortality All-cause mortality, no./total no. of patients (%) I: 127 276 (46.0%) C: 123/286 (43.0%) HR (95%CI): 1.24 (0.97–1.60)

Length of ICU stay Not reported

Organ support free days Not reported

Venous thromboembolism Adjudicated venous thromboembolism, no./total no. of patients (%) I: 9/276 (3.3%) C: 10/286 (3.5%) HR (95%CI): 0.93 (0.48–1.76)

Objectively clinically diagnosed acute peripheral arterial thrombosis, no./total no. of patients (%) I: 0/276 C: 0/286

Objectively clinically diagnosed stroke, no./total no. of patients (%) I: 1/276 (0.4) C: 1/286 (0.3) HR (95%CI): 1.03 (0.06–16.56)

Objectively clinically diagnosed type I acute myocardial infarction, no./total no. of patients (%) I: 0/276 C: 0/286

Major bleeding n/total (%) I: 7/276 (2.5%) C: 4/286 (1.4%) |

Author’s conclusions: By the end of 90-day clinical follow-up, intermediate dose prophylactic anticoagulation compared with standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation did not result in a reduction in the 90-day composite of venous or arterial thrombosis, treatment with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or all-cause mortality. Collectively, these findings do not support the routine use of intermediate-dose prophylactic anticoagulation in ICU patients with COVID-19. |

|

Goligher, 2021

The REMAP-CAP, ACTIV-4a, and ATTACC Investigators |

Type of study: open-label, international, adaptive, multiplatform RCT (mpRCR)

Setting and country: The lead investigators of three international adaptive platform trials harmonized their protocols to study the effect of therapeutic anticoagulation in patients hospitalized for Covid-19 into one integrated mpRCT. The participating platforms included the REMAP-CAP; ACTIV-4a andATTACC. Patients were included in the UK, USA, Canada, Brazil, Ireland, Netherlands, Australia, Nepal, Saudi Arabia, and Mexico.

Funding and conflicts of interest: The trial was supported by multiple international funding organizations who had no role in the design, analysis or reporting of the trial result.

REMAP-CAP was supported by the European Union through FP7-HEALTH-2013-INNOVATION: the PREPARE consortium (grant 602525) and the Horizon 2020 research and innovation program: the RECOVER consortium (grant 101003589) and by grants from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1101719 and APP1116530), the Health Research Council of New Zealand (16/631), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research Innovative Clinical Trials Program Grant 158584 and COVID-19 Rapid Research Operating Grant 447335), the U.K. National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre, the Health Research Board of Ireland (CTN 2014-012), the UPMC Learning While Doing Program, the Translational Breast Cancer Research Consortium, the French Ministry of Health (PHRC-20-0147), the Minderoo Foundation, Amgen, Eisai, the Global Coalition for Adaptive Research, and the Wellcome Trust Innovations Project (215522).

The ATTACC platform was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, LifeArc, Thistledown Foundation, Research Manitoba, CancerCare Manitoba Foundation, Victoria General Hospital Foundation, Ontario Ministry of Health, and the Peter Munk Cardiac Centre.

The ACTIV-4a platform was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the NIH and administered through OTA-20-011 and was supported in part by NIH agreement 1OT2HL156812-01.

|

Inclusion criteria: Patients hospitalized for severe COVID-19* with confirmed infection.

Exclusion criteria: Patients were ineligible if they had been admitted to the ICU with Covid-19 for 48 hours or longer (in REMAP-CAP) or to a hospital for 72 hours or longer (in ACTIV-4a and ATTACC) before randomization.

REMAP-CAP: