Antipsychotica tijdens zwangerschap en neonatale effecten en symptomen

Uitgangsvraag

Welke antipsychotica hebben de voorkeur voor gebruik in de zwangerschap met betrekking tot het risico op neonatale effecten en symptomen?

Aanbeveling

Bespreek met de patiënte dat er geen eenduidig advies te geven is voor een specifiek middel op basis van het risico op neonatale symptomen. Een heldere indicatie is noodzakelijk voor het voorschrijven van een antipsychoticum.

Observeer de pasgeborene na maternaal gebruik van een antipsychoticum voor de duur van minimaal 24 uur op de kraamafdeling op symptomen van ontwenning. Bij gebruik van een hoge dosis, meerdere psychotrope medicaties, andere co-medicatie met mogelijke invloed op de neonatale transitie of centraal zenuwstelsel, dan wel prematuriteit kan geïndividualiseerd beleid ten aanzien van de duur van de observatie dan wel monitorbewaking van toepassing zijn.

Wees extra alert tijdens neonatale observatie, met name op vitale parameters en sedatie, bij maternaal gebruik van antipsychotica waar nog nauwelijks ervaring mee is (bijvoorbeeld clozapine). De duur van de observatie periode zal afhangen van de amenorroeduur en de klinische conditie van de neonaat, waarbij de minimale duur afhankelijk zal zijn van de halfwaardetijd van het betreffende antipsychoticum.

Overwegingen

De kwaliteit van het bewijs

De kwaliteit van het voorhanden zijnde bewijs is zeer laag. Er zijn geen RCT’s beschikbaar. Het bewijs is gebaseerd op cohortstudies, waarbij meestal teratologie of voorschrijf databases gekoppeld zijn aan geboorte data. Een studie (Sutter-Dallay, 2015) maakt hierin een uitzondering door een database te gebruiken van het Franse netwerk van moeder-baby units in Frankrijk. Drie studies maken gebruik van prospectieve data (Diav-Citrin, 2005, Lin, 2010 en Habermann, 2013), vier studies hebben prospectief verzamelde cohort data in retrospect geanalyseerd (Bellet, 2015; Sutter-Dallay, 2015; Sadowski, 2013 en Petersen, 2016) en twee studies hebben gebruik gemaakt van retrospectief verzamelde data (Boden, 2012 en Vigod, 2015). Het aantal blootgestelde zwangeren, waarbij uiteindelijk naar de neonatale effecten is gekeken varieert van 86 (Bellet, 2015) tot 1209 (Vigot, 2015). Slechts één studie heeft geïsoleerd naar het effect van 1 antipsychoticum gekeken (i.e. aripiprazol; Bellet, 2015) en een andere studie heeft zich gericht op de klassieke antipsychotica haloperidol en penfluridol (Diav-Citrin, 2005). De studie van Boden (2012) heeft zich gericht op mogelijke diabetogene effecten en heeft daarmee twee antipsychotica gekozen met potentieel de grootste kans op metabool syndroom, i.e. olanzapine en clozapine, afgezet tegen overige antipsychotica. Twee studies hebben groepen psychofarmaca bestudeerd en daarin de antipsychotica meegenomen (Vigod, 2015 en Petersen, 2016). Ten slotte zijn er twee studies die naar de effecten van atypische antipsychotica hebben gekeken (Haberman, 2013 en Sadowski, 2013) en twee die de potentiële effecten van typische en atypische antipsychotica tegen elkaar af hebben gezet (Sutter-Dallay, 2015 en Lin, 2010). De informatie over potentiële confounders, de ernst van maternale ziekte, polyfarmacie en kenmerken van de controlegroepen wisselt en niet alle studies hebben hiervoor gecorrigeerd in de analyses (Bellet, 2015; Diav Citrin, 2005; Sadowski, 2013). Door de studie-opzet, i.e. cohort studie, ontbreekt in de meeste gevallen de maternale psychiatrische diagnose met daarmee ook de indicatie voor het antipsychotica gebruik. Ten slotte valt ook commentaar te leveren op de beschikbare controle groepen. Slechts drie studies hebben de data kunnen afzetten tegen een controle groep met moeders met een psychiatrische diagnose, maar zonder antipsychotica (Lin, 2010; Vigod, 2015 en Sutter-Dallay, 2015). In de meeste gevallen betekent “unexposed” niet dat er geen enkel medicijn is voorgeschreven, maar dat er of andere psychofarmaca zijn voorgeschreven in de zwangerschap of middelen waarvan is aangetoond dat er geen potentieel teratogene effecten zijn.

Op basis van de gerapporteerde studies kan geen eenduidige conclusie getrokken worden ten aanzien van een eventuele verhoogde kans op neonatale effecten en symptomen. Wel wordt een verhoogde kans op opname op de Neonatal Intensive Care of op de kinderafdeling in de eerste levensmaand beschreven, maar tegelijkertijd staat in de studies de indicatie niet beschreven, waarbij het ook kan gaan om observatie opnames. Anderzijds is er ook geen aangetoond ernstig verhoogd risico op een specifiek patroon van neonatale complicaties. Er wordt in een aantal studies een licht verhoogd risico gerapporteerd, dat in andere studies niet gevonden wordt. Drie studies geven wel een verhoogd risico aan voor neonatale complicaties danwel neonatale abstinentie en met name bij polyfarmacie (Habermann, 2013; Sadowski, 2013 en Diav-Citrin, 2005). Daarentegen konden twee andere studies niet duidelijk bevestigen (Petersen, 2016 en Vigod, 2015).

Overige geraadpleegde bronnen

Ook buitenlandse richtlijnen en beschouwende artikelen refereren aan het gebrek aan voldoende conclusieve studies. De NICE-richtlijn van 2014 adviseert ‘When choosing an antipsychotic, take into account that there are limited data on the safety of these drugs in pregnancy and the postnatal period.’ (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2014).

De richtlijn van de American Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists dateert van 2008 en maakte geen gebruik van een systematische literatuurstudie. In algemene zin beschrijft deze richtlijn ten aanzien van klassieke antipsychotica ‘‘In summary, typical antipsychotics have been widely used for more than 40 years, and the available data suggest the risks of use of these agents are minimal with respect to teratogenic or toxic effects on the fetus.” Daarnaast beschrijft de richtlijn, gebaseerd op case reports, ook mogelijke neonatale effecten van typische antipsychotica zoals maligne neuroleptisch syndroom, dyskinesie, extrapiramidale bijwerkingen in de vorm van verhoogde spiertonus, versterkte reflexen, geelzien en darmobstructie (American Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2008). De richtlijn adviseert “Doses of typical antipsychotics during the peripartum should be kept to a minimum to limit the necessity of utilizing medications to manage extrapyramidal side effects”.

Ten aanzien van atypische antipsychotica concludeert de richtlijn ”There is likewise little evidence to suggest that the currently available atypical antipsychotics are associated with elevated risks for neonatal toxicity or somatic teratogenesis. No long-term neurobehavioral studies of exposed children have yet been conducted. Therefore, the routine use of atypical antipsychotics during pregnancy and lactation cannot be recommended” (American Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2008).

The richtlijn van de British Association of Pharmacologists (BAP) dateert van 2017 en verwijst ook naar literatuur, die niet bleek te voldoen aan de kwaliteitscriteria die gehanteerd werden voor deze richtlijn (McAllister-Williams, 2017). De BAP richtlijn benoemt voorzichtigheid ten aanzien van extrapyramidale en ontwenningssymptomen. Het refereert daarbij grotendeels naar de door ons beschreven studies (Habermann, 2013; Sadowski, 2013; Petersen, 2016 en Vigod, 2015). Zij adviseren wel monitoring van de neonaat maar zonder het verder te specificeren of te onderscheiden in typische of atypische antipsychotica.

Het teratologie informatie centrum (TIS) van Lareb benoemt voor de typische antipsychotica: ‘Het gebruik van klassieke antipsychotica tot aan de bevalling kan bij het kind onthoudings- of toxische verschijnselen veroorzaken, zoals prikkelbaarheid, bewegingsstoornissen, verhoogde spierspanning, trillen, onregelmatige ademhaling, slecht drinken en hard huilen.’ Haloperidol wordt geduid als waarschijnlijk veilig in het eerste en tweede trimester met een mogelijk risico in het derde trimester, duidend op de mogelijke neonatale effecten. Voor broomperidol, chloorprotixeen, flufenazine, flupentixol, fluspirileen, penfluridol, perfenazine, periciazine, pimozide, pipamperon, sulpiride, tiapride en zuclopentixol wordt vermeld dat het risico onbekend is. Voor de atypische antipsychotica benoemt het TIS dat ‘Toepassing van antipsychotica in het derde trimester van de zwangerschap kan leiden tot extrapiramidale stoornissen (bewegingsstoornissen) bij het pasgeboren kind. Langdurig gebruik tot aan de bevalling kan onthoudingsverschijnselen bij het pasgeboren kind veroorzaken, waaronder prikkelbaarheid, hypertonie (verhoogde spierspanning), tremoren, onregelmatige ademhaling, slecht drinken en hard huilen.’ Aripiprazol, olanzapine en quetiapine duiden zij als waarschijnlijk veilig in het eerste en tweede trimester met in het geval van deze drie middelen een mogelijk risico in het derde trimester, duidend op de mogelijke neonatale effecten. Voor asenapine, clozapine, lurasidon, paliperidon, risperidon en sertindol wordt vermeld dat het risico onbekend is.

Samengevat wijzen de overige richtlijnen en bronnen naar de kans op neonatale verschijnselen, waaronder extrapiramidale verschijnselen als bijwerking van de blootstelling aan medicatie en onthoudingsverschijnselen. Overigens staan nergens relaties beschreven met doseringen of eventueel spiegels vanuit navelstrengbloed. Genoemde verschijnselen zijn maligne neuroleptisch syndroom, dyskinesie, extrapiramidale bijwerkingen, geelzien en darmobstructie, prikkelbaarheid, hypertonie (verhoogde spierspanning), tremoren, onregelmatige ademhaling, slecht drinken en hard huilen. De frequentie van voorkomen is niet bekend. Daarnaast spreekt de ACOG-richtlijn vanuit foetaal en neonataal perspectief een voorkeur uit voor klassieke antipsychotica ten opzichte van atypische antipsychotica.

Farmacologische overwegingen

Bij de keuze van een antipsychoticum worden verschillende factoren meegenomen, zoals de effectiviteit, methode van toediening, incidentie dan wel ervaring van bijwerkingen, de effectiviteit bij terugvalpreventie en veiligheid tijdens de zwangerschap individueel worden afgewogen. Ten aanzien van de neonatale effecten is het van belang te overwegen in welke mate medicatie daadwerkelijk bij de foetus terecht komt. Gegevens over transplacentaire passage en eventueel medicatie spiegels bij de pasgeborene kunnen bij deze beslissing meewegen. Over spiegels bij de pasgeborene zijn geen gegevens bekend.

De gegevens ten aanzien van transplacentaire passage zijn zeer beperkt. Een systematische review, die de transplacentaire passage beschrijft in totaal 72 cases aan de hand van een vergelijking van navelstrengbloed met maternaal bloed, vermeldt de volgende gemiddelde passages (van laag naar hoog): active moiety of aripiprazole (mean 0.22), quetiapine 0,24 (range 0.13 tot 0.32), flupentixol LAI (mean 0.22, range 0.14 tot 0.35), paliperidone LAI 0,35 (range 0.50 tot 0.58), haloperidol van 0,66 (SD 0,40), olanzapine (mean 0.71, standard deviation, SD, 0.42). De zeer beperkte beschikbare gegevens leiden tot inconclusiviteit ten aanzien van de placentaire passage, hoewel de passage van aripiprazol en quetiapine binnen de bestudeerde groep van antipsychotica relatief laag lijkt.

Informatie kan ook verkregen worden vanuit dierexperimentele gegevens. Ook dierexperimentele studies zijn zeer beperkt en hebben zich voornamelijk gericht op teratogeniciteit en niet op neonatale effecten na de partus (Gentile, 2010). In studies met specifiek aripripazol en risperidon werd een verminderde foetale groei gerapporteerd in ratten die hieraan werden blootgesteld. Specifiek bij risperidon blootstelling ging dit gepaard met verstoorde placenta-opbouw en histopathologische laesies (Singh, 2016). Samengevat is de informatie vanuit dierexperimentele studies beperkt waarbij er enige aanwijzingen zijn dat er een impact is op de foetale groei en mogelijk op de placenta-ontwikkeling.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten

Er is vrijwel geen literatuur ten aanzien van de waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, die een rol spelen bij de besluitvorming rondom het gebruik van antipsychotica ten tijde van de zwangerschap. Vanzelfsprekend speelt het bijwerkingenprofiel een rol bij de voorkeuren van patienten, evenals buiten de zwangerschap. Onderzoek bij zwangeren die anxiolytica en antidepressiva gebruiken en zwanger worden, laat zien dat de mogelijke invloed op het (ongeboren) kind een belangrijke overweging is om medicatie te staken (Kothari, 2019). Het afwegen van de risico’s en de meest veilige beslissing nemen wordt ook genoemd als een belangrijk thema (Nygaard, 2015). Echter, of dit ook geldt voor patiënten die antipsychotica gebruiken is naar onze kennis niet onderzocht.

Een nationale studie in de VS laat zien dat 50% van de vrouwen die atypische antipsychotica gebruikt in de drie maanden voorafgaand aan de zwangerschap, deze staakt tijdens de zwangerschap. Het is niet waarschijnlijk dat al deze vrouwen de antipsychotica gebruikten in verband met een psychotische stoornis. Aangezien het een register studie betrof, is de reden van staken niet bekend (Huybrechts, 2017). Vanuit de richtlijn antipsychotica gebruik blijkt dat subjectief welbevinden een belangrijke maat is voor het continueren van het antipsychoticum (richtlijnen database schizofrenie FMS). Vanzelfsprekend speelt ook het bijwerkingen profiel hierin mee. De ‘betere naam' die de atypische antipsychotica kregen vergeleken met de typische antipsychotica is een factor geweest bij de acceptatie van gebruik (Courtet, 2001). Daarnaast speelt in vrouwen met depressie het stigma van de psychiatrische stoornis een rol bij besluitvorming rondom het gebruik van psychotrope medicatie (Hippman, 2018). Dit zal bij patiënten met een psychose gevoeligheid niet anders liggen, hoewel niet specifiek onderzocht. Onderzoek naar activiteit op sociale media in relatie met wetenschappelijke publicaties rondom antidepressivagebruik tijdens de zwangerschap liet een verdubbeling zien van deze activiteit bij studies, waarbij er een associatie was met studies die een risico beschreven en er alleen relatieve risico’s (en niet de absolute risico’s) genoemd worden in de samenvatting. Dit suggereert dat een mogelijk risico van medicatiegebruik tijdens de zwangerschap een belangrijk thema is (Vigod, 2018). Een recente studie vanuit het Radboud UMC liet zien dat veel zwangeren in hun zoektocht naar informatie over zwangerschap en medicatiegebruik veel onjuiste informatie tegenkomen, hetgeen hun beslisvorming in negatieve zin kan beïnvloeden (van Gelder, 2019).

Samenvattend lijkt de veiligheid van medicatie voor het (ongeboren) kind een belangrijke overweging voor zwangeren in de besluitvorming rondom het gebruik van psychotrope medicatie tijdens de zwangerschap. Hiernaast speelt subjectief welbevinden en stigma een rol. Ten slotte is er een toename van activiteit op sociale media na publicaties van studies ten aanzien van risico en staakt 50% van de vrouwen die antipsychotica gebruikt in de drie maanden voorafgaand aan de zwangerschap, deze bij zwangerschap.

Kosten

De kosten van de verschillende antipsychotica liggen dusdanig dicht bij elkaar dat de kosten per middel geen rol van betekenis spelen bij de medicatie keuze. Het staken van de antipsychotica tijdens de zwangerschap kan in sommige situaties leiden tot ernstige ontsporing, met mogelijk klinische opname en zorgmijding met alle kosten vandien. Daarnaast kan daaruit voortvloeiende ernstige stress en verminderde capaciteit tot adequate interactie met het kind de ontwikkeling van het kind in de cruciale periode van de eerste 1000 dagen ongunstig beïnvloeden met verhoogde kans op ontwikkelings-, gedrags-, en emotionele problemen later in het leven, hetgeen zal leiden tot middelenbeslag. Ook kan de noodzaak tot het tijdelijk of langdurig overnemen van de zorg voor het kind door derden leiden tot een aanzienlijk middelenbeslag.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De werkgroep vindt antipsychotica gebruik tijdens zwangerschap met betrekking tot het risico op neonatale effecten en symptomen een aanvaardbare interventie mits er een juiste indicatie is en er een goede afweging is gemaakt ten aanzien van eventuele alternatieve behandelstrategieën.

Door implementatie van netwerkzorg voor zwangere vrouwen met antipsychotica gebruik, zoals bijvoorbeeld een multidisciplinaire POP-poli/ teams, zullen alle betrokkenen (huisarts, verloskundig zorgverlener, GGZ zorgverlener (psychiater, psycholoog, verpleegkundig specialist, sociaal-psychiatrisch verpleegkundige (SPV), physician assistant (PA)), kraamverzorgster, maatschappelijke werker, medewerkers van jeugdgezondheidszorg (CB/CJG) en kinderarts) tijdig geïnformeerd zijn over de afwegingen voor de individuele zwangere om een antipsychoticum wel of niet te continueren en de mogelijke neonatale gevolgen, zoals ontwenning. Ook maatschappelijk bestaat er een inzicht in en groeiend draagvlak voor het belang van geïntegreerde zorg voor moeder en kind gedurende de eerste 1000 dagen van de ontwikkeling, zoals ook tot uitdrukking komt in het landelijke programma ‘kansrijke start’ van de Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport.

Gezien de wisselende halfwaardetijden tussen de verschillende antipsychotica is het van belang de zorgverleners in het kraambed, zoals de verloskundige, kraamverzorgende, CJG arts en huisarts tijdig te informeren over de te verwachten effecten. Patiënte dient hierover ook geïnformeerd te zijn. Op basis van de receptorprofielen zijn de belangrijkste symptomen die verwacht kunnen worden extrapiramidale verschijnselen, zoals tremoren en dyskinesie, sufheid, slecht drinken, huilen, hypotonie en eventueel convulsies.

Rationale/ balans tussen de argumenten voor en tegen de interventie

Op basis van de momenteel voor handen zijnde gegevens ten aanzien van het risico op neonatale effecten en symptomen geldt dat het relatieve onbekende risico op de verschillende neonatale effecten, zoals neonatale mortaliteit, neonatale opnames, laag geboorte gewicht, small/ large for gestational age (SGA/ LGA), neonatale symptomen en vroeggeboorte, afgewogen moet worden tegen de noodzaak van het gebruik tijdens de zwangerschap. Daarbij moet in acht worden genomen dat er ook gekeken moet worden naar een maximale inzet van niet-medicamenteuze interventies in acht nemen en de voorkeuren van de (toekomstige) zwangere. Te allen tijde dient gestreefd te worden naar een zo laag mogelijke dosering met een voldoende veilig maar ook doelmatig/ effectief antipsychoticum.

Als gevolg van het ontbreken van eenduidige evidentie uit de literatuur, kan de werkgroep geen harde aanbeveling doen over het gebruik van antipsychotica tijdens de zwangerschap, wat betreft de neonatale effecten en symptomen van een intra-uteriene blootgesteld kind.

Vanuit de voor deze uitgangsvraag gebruikte literatuurstudie is er niet één specifiek antipsychoticum met een sterke voorkeur. De voorkeuren vanuit het TIS, i.e. haloperidol, olanzapine, quetiapine of aripiprazol hebben waarschijnlijk te maken met de hoeveelheid onderzoek. Uit onze analyse wordt het gebruik van polyfarmacie wel afgeraden op basis van het verhoogde risico op neonatale symptomen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Antipsychotica zijn over het algemeen effectief in de behandeling en preventie van psychotische stoornissen. Stabiliteit is van belang voor zowel de zwangere als het (ongeboren) kind. Antipsychotica bereiken, middels transplacentaire passage, ook het (ongeboren) kind. Vanuit de praktijk is de ervaring dat de impact op het kind een belangrijke overweging is voor zwangeren in het starten of continueren van antipsychotica. Voor een goede afweging en shared decision-making is adequate informatie over de impact op de ontwikkeling van het kind van groot belang. Ook de effecten op de neonaat in de periode na de bevalling zijn hierbij van belang. Daarnaast zijn de effecten op de neonaat van belang voor het bepalen van de noodzaak tot klinische observatie gedurende een deel van het kraambed.

Antipsychotica worden in de wetenschappelijke literatuur meestal ingedeeld in typische en atypische antipsychotica.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of antipsychotics use during pregnancy on the risk of neonatal mortality < 90 days postpartum in children of women with psychiatric disorders, compared to women not taking antipsychotics during pregnancy.

Bronnen: (Vigod, 2015) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of antipsychotics use during pregnancy on the risk of neonatal intensive care unit admissions in children of women with psychiatric disorders, compared to women not taking antipsychotics during pregnancy.

Bronnen: (Sadowski, 2013) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of antipsychotics use during pregnancy on the risk of neonatal hospitalization in the 1st month of life in children of women with psychiatric disorders, compared to women with psychiatric disorders not taking antipsychotics during pregnancy.

Bronnen: (Sutter-Dallay, 2015) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of antipsychotics use during pregnancy on the risk of low birth weight (< 2500 g) in children of women with psychiatric disorders, compared to women with psychiatric disorders or to healthy women not taking antipsychotics during pregnancy.

Bronnen: (Lin, 2010; Sutter-Dallay, 2015; Petersen, 2016) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of antipsychotics use during pregnancy on the risk of being small for gestational age in children of women with psychiatric disorders, compared to women with psychiatric disorders or to healthy women not taking antipsychotics during pregnancy.

Bronnen: (Bellet, 2015; Boden, 2012; Lin, 2010; Vigod, 2015; Sadowski 2013) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of antipsychotics use during pregnancy on the risk of being large for gestational age in children of women with psychiatric disorders, compared to women with psychiatric disorders or to healthy women not taking antipsychotics during pregnancy.

Bronnen: (Boden, 2012; Lin, 2010; Vigod, 2015; Sadowski 2013) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of antipsychotics use during pregnancy on the risk of neonatal symptoms in children of women with psychiatric disorders, compared to women with psychiatric disorders or to healthy women not taking antipsychotics during pregnancy.

Bronnen: (Bellet, 2015; Diav-Citrin, 2005; Vigod, 2015; Sadowski 2013; Habermann, 2013; Petersen, 2016) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of antipsychotics use during pregnancy on the risk of preterm birth (< 37 weeks) in children of women with psychiatric disorders, compared to women with psychiatric disorders or to healthy women not taking antipsychotics during pregnancy.

Bronnen: (Bellet, 2015; Boden, 2012; Vigod, 2015; Sadowski, 2013; Habermann, 2013, Reis, 2008) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

All studies had a prospective cohort design or nested case-control. The number of women treated with antipsychotics during pregnancy varied from 86 to 1209 across the studies. In four studies, the definition of exposure was the use of any antipsychotics during pregnancy (Vigod, 2015; Petersen, 2016; Sutter-Dallay, 2015; Reis, 2008). There was one study focused on the exposure to aripiprazole (Bellet, 2015) and one study describing only the effects of atypical antipsychotics (Sadowski, 2013). Another study compared clozapine and olanzapine together (clustered because of the potential high risk for metabolic syndrome with diabetes) with other antipsychotics in the exposed group (Boden, 2012). Diav-Citrin (2005) compared the effect of haloperidol and penfluridol with no antipsychotic use during pregnancy. Lin (2010), Habermann (2013) and Petersen (2016) reported comparison between typical and atypical antipsychotics with no antipsychotics. The timing and duration of exposure was not well-characterized in most of the included studies. Medication use during any time of pregnancy was included. The duration of follow-up for the ascertainment of the outcomes varied across the studies from 42 to 730 days after delivery. The outcome ‘preterm birth’ was defined as birth at gestational age < 37 weeks (reported in 9 studies). In some of the included studies, ‘preterm birth’ was also defined as birth at gestational age < 36 weeks (1 study), < 32 weeks and < 28 weeks (1 study), and as a part of a composite outcome ‘prematurity/low birth weight’ (1 study). The outcome ‘small for gestational age’ was reported in 5 studies and was defined as birth weight < 10th percentile for gestational age according to the Audipog reference curve (1 study), ≤ 2.3rd percentile of the total population by infant sex (1 study), < 10th percentile for gestational age (2 studies) and birth weight < 3rd centile and < 10th centile (1 study). The outcome ‘large for gestational age’ was described in 4 studies and was defined as birth weight at ≥ 97.7th percentile of the total population by infant sex (1 study), or birth weight > 10th percentile for gestational age (1 study), or birth weight > 90 centile and > 97th centile (2 studies). The outcome ‘low birth weight’ was defined as birth weight < 2500 g (2 studies). Furthermore, some studies also reported median and mean birth weight in the exposed and unexposed groups. Neonatal effects and symptoms were reported in 6 studies; in one of the studies neonatal symptoms were reported as part of a composite outcome ‘adverse birth outcomes’, which consisted of a low Apgar score (< 7), tremor, agitation, any breathing problems and/or problems with the infants’ muscle tone. Neonatal mortality < 90 days postpartum was reported in 1 study (Vigod, 2015).

Results

The results of the studies are presented by outcome measure.

Neonatal mortality < 90 days postpartum (critical outcome)

Vigod (2015) found no statistically significant differences in neonatal mortality < 90 days postpartum, when comparing women who had ≥ 2 consecutive prescriptions for any type of antipsychotics during pregnancy (with at least 1 prescription in the 1st or 2nd trimester, n=1209) with women who filled no prescriptions for antipsychotics during pregnancy, n=40314 (crude RR 1.64 (95% CI 0.84 to 3.20)). After matching 1021 antipsychotic users with 1021 non-users with psychiatric disorders using propensity scores, there was also no increase in neonatal mortality < 90 days postpartum (crude RR 1.50 (95% CI 0.53 to 4.21); Vigod, 2015).

Neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admissions (critical outcome)

Sadowski (2013) reported a statistically significant increase in the prevalence of NICU admissions in live-born infants of women treated with atypical antipsychotics for a minimum of 4 weeks during pregnancy compared with no use of antipsychotics (25.3% and 9.5%, respectively; p=0.002). There was no statistically significant difference when monotherapy with an atypical antipsychotic was compared with a combination of an atypical antipsychotic and other psychotropic drugs (16% and 28.8%, p=0.21), yet there was a trend toward a higher rate of NICU admissions in the polytherapy group (Sadowski, 2013). Whether or not neonatal intensive care unit admission was for observation or because of symptoms, was not specified.

Neonatal hospitalization in the 1st month of life (important outcome)

Sutter-Dallay (2015) found an OR of 1.74 (95% CI 1.19 to 2.54) for neonatal hospitalizations in the 1st month of life, when comparing users of any type of antipsychotics during pregnancy with non-users with psychiatric disorders. The reason of hospitalization was not specified. When the analysis was restricted to term neonates (≥ 36 weeks), the association was still statistically significant (OR 2.11 (95% CI 1.36 to 3.27); Sutter-Dallay, 2015). For neonates with a birth weight of ≥ 2500 g there was still an increased risk (OR 1.91 (95% CI 1.17 to 3.10)), and for underweight neonates < 2500 g, it was nominally (p=0.05) statistically significant (OR 2.98 (95% CI 1.01 to 8.84)) (Sutter-Dallay, 2015).

Low birth weight (< 2500 g) (important outcome)

Lin (2010) found no difference in the prevalence of low birth weight between neonates of women taking typical antipsychotics and women with psychiatric disorders not treated with antipsychotics during pregnancy (OR 0.95 (95% CI 0.50 to 1.75). For atypical antipsychotics, there was also no increase in risk (OR 1.71 (95% CI 0.67 to 4.34); Lin, 2010).

Sutter-Dallay (2015) also found no increase in risk of low birth weight for users of any antipsychotics, as compared to non-users with psychiatric disorders (OR 0.89 (95% CI 0.62 to 1.55)).

Petersen (2016) used a composite outcome, consisting of prematurity and a low birth weight (< 2500 g). In contrast to the findings of Lin (2010) and Sutter-Dallay (2015), the Petersen (2016) study found an increased risk for this composite outcome in the children of women taking antipsychotics (Table 1).

Children of women prescribed antipsychotics in pregnancy were more than twice as likely to experience premature birth/low birth weight than children of healthy unexposed women or women who discontinued antipsychotics (Table 1; Petersen, 2016).

Table 1 Absolute risks and relative risk ratios for the composite outcome premature/low birth weight according to antipsychotic exposure (Petersen, 2016)

|

premature/ low birth weight |

Absolute risk (%) |

Risk difference (95% CI) |

Relative risk ratio, crude (95% CI) |

Relative risk ratio, adj. (95% CI) |

|||

|

|

exp. |

discont. |

unexp. |

Versus discontinued |

Versus unexposed |

Versus discontinued |

Versus unexposed |

|

Total N |

290 |

492 |

210966 |

|

|

|

|

|

Any AP |

10 |

4.3 |

3.9 |

5.7 (1.8, 9.6) |

6.1 (2.6, 9.5) |

2.34 (1.33, 4.10) |

2.04 (1.13, 3.67)) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.53 (1.76, 3.65) |

1.43 (0.99, 2.05) |

|

Total N |

102 |

292 |

210966 |

|

|

|

|

|

Typical AP

|

11.8 |

4.8 |

3.9 |

7 (0.3, 13.7) |

7.8 (1.6, 14.1) |

NA |

NA |

|

Total N |

203 |

230 |

210966 |

|

|

|

|

|

Atypical AP |

8.4 |

3.9 |

3.9 |

4.5 (-0.1, 9) |

4.4 (0.6, 8.2) |

NA |

NA |

AP, antipsychotic(s). adj., adjusted.

A significant difference between the exposed and discontinued groups remained after adjustment for age, obesity, alcohol problems, smoking, illicit drug use, and antidepressant and anticonvulsant mood stabilizers (risk ratio adj. 2.04 (95% CI 1.13 to 3,67)) and there was a borderline difference between exposed and healthy unexposed (risk ratio adj. 1.43 (95% CI 0.99 to 2.05); (Table 1; Petersen, 2016).

Small for gestational age (important outcome)

In the study by Bellet (2015) there was a higher proportion of children with birth weight < 10th percentile for gestational age (according to the Audipog reference curve) in the aripiprazole-exposed group (n=12 out of 63 exposed), compared to the unexposed group (n= 11 of 150 unexposed; crude OR 2.97 (95% CI 1.23 to 7.16); Bellet, 2015).

Boden (2012) found no increase in the rates of being small for gestational age (≤ 2.3rd percentile) according to birth weight, birth length and head circumference in women taking clozapine, olanzapine or other antipsychotics (Boden, 2012).

Lin (2010) showed no increased risk of being small for gestational age (birth weight < 10th percentile for gestational age) after intrauterine exposure to typical or atypical antipsychotics.

Comparing with an unmatched cohort of unexposed women, Vigod (2015) found an increase in the relative risk for being small for gestational age (< 10th centile) in neonates of women filling prescriptions for antipsychotics during pregnancy (crude RR 1.33 (95% CI 1.15 to 1.54)). However, compared to a matched cohort including unexposed women with psychiatric disorders, the risk of being small for gestational age was not longer statistically significant (RR adj. 1.20 (95% CI 0.97 to 1.50), after adjustment for a prescribed SSRI, non-SSRI, mood stabilizers, or benzodiazepines during the index pregnancy).

In the study by Sadowski (2013) there was no difference in the prevalence of neonates small for gestational age (< 10th centile) between the exposed and unexposed groups (11.6% and 8.8%, p=0.49).

Large for gestational age (important outcome)

In the study by Boden (2012) the neonates exposed in utero to olanzapine and/or clozapine had an increased risk of being large for gestational age (birth weight > 10th percentile for gestational age) according to the head circumference (OR 3.02 (95% CI 1.60 to 5.71); Boden (2012). Lin (2010) found no statistically significant differences between exposed to typical or atypical antipsychotics in terms of being large for gestational age (birth weight > 10th percentile for gestational age). In the matched cohort in the study of Vigod (2015) there were also no indications of an increased risk for being large for gestational weight (> 97 and > 90 centile). Sadowski (2013) on the other hand, reported an increased prevalence of large of gestational age neonates in the exposed group (only atypical antipsychotics; 11.6% versus 3.5%, p=0.02).

Neonatal symptoms (important outcome)

Vigod (2015) provided information on a wide variety of neonatal symptoms. Compared with the unmatched cohort in an unadjusted analysis, neonates of women taking antipsychotics in pregnancy had a 87% increase in risk of the respiratory distress syndrome (RR 1.87 (95% CI 1.31 to 2.66)), a 330% increase in risk of seizures (RR 4.30 (95% CI 2.22 to 8.33)), a 126% increase in risk of sepsis (RR 2.26 (95% CI 1.53 to 3.32)), a 184% increase in risk of intraventricular hemorrhage (RR 2.84 (95% CI 1.53 to 5.27)), and a 606% increase in risk of the neonatal adaptation syndrome (RR 7.06 (95% CI 5.91 to 8.45)). In the matched cohort, the number of events was often too low to estimate relative risk, but for the respiratory distress syndrome, seizures, sepsis and the neonatal adaptation syndrome no statistically significant differences were found (Vigod, 2015).

The risk of postnatal disorders (a composite outcome of respiratory, digestive, cardiac, nervous system disorders and multiple system disorders) in the study by Habermann (2013) was increased in live-born infants exposed to antipsychotics at least during the last gestation week. Neonates exposed to both atypical and typical antipsychotics had a higher risk than the unexposed (OR 6.24 (95% CI 3.51 to 11.10) and OR 5.03 (95% CI, 2.21 to 11.44); Habermann, 2013).

Sadowski (2013) found an increase in prevalence of poor adaptation signs in exposed infants (16.5% versus 5.2%, p=0.007).

Petersen (2016) used a composite of adverse birth outcomes (Apgar score < 7, tremor, agitation, any breathing problems, problems with the infants’ muscle tone) and found no differences between the exposed and unexposed (RR adj. 1.03 (95% CI 0.50 to 2.12) versus women who discontinued antipsychotics and RR adj. 1.46 (95% CI 0.87 to 2.46) versus healthy unexposed women; Petersen, 2016).

Preterm birth (< 37 weeks) (important outcome)

Including only singleton pregnancies in the analysis (n=563), Reis (2008) found an increased risk for preterm birth (< 37 weeks gestation) in women taking any antipsychotics in the first trimester of pregnancy, compared to women not taking antipsychotics (adjusted OR 1.73 (95% CI 1.31 to 2.29); Reis, 2008).

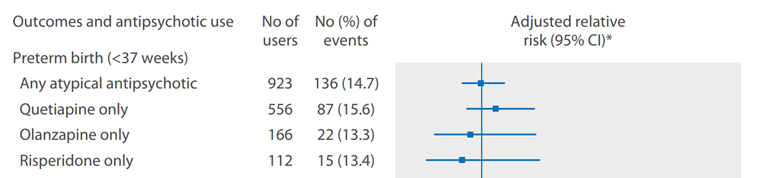

Vigod (2015) showed that women exposed to any type of antipsychotics (n=1209) had an increased risk of preterm delivery (crude RR 1.51 (95% CI 1.29 to 1.78)), compared to unmatched healthy controls (n=40 314). However, compared to matched unexposed controls (n=1021) with psychiatric disorders, the risk of preterm delivery in the antipsychotic-exposed group (n=1021) was not increased (crude RR 1.01 (95% CI 0.81 to 1.27), adjusted RR 0.99 (95% CI 0.78 to 1.26). Furthermore, when the analysis was restricted to 923 (out of 1021) cases exposed only to atypical antipsychotics, compared to matched unexposed controls with psychiatric disorders, there was also no increased risk of preterm delivery (Figure 1; Vigod, 2015).

Figure 1 Adjusted relative risks for preterm birth (< 37 weeks) by individual atypical antipsychotic in the matched cohort (restricted to users of atypical antipsychotics, n=923; Vigod, 2015). The risk of preterm delivery was not significantly different between antipsychotic users and matched non-users (Vigod, 2015)

*Adjusted for a prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), non-SSRI, mood stabiliser, and/or benzodiazepine medication during the index pregnancy (Vigod, 2015)

In a group of women with schizophrenia treated with typical antipsychotics during pregnancy, Lin (2010) found an increased risk of preterm birth (OR adj. 2.46 (95% CI 1.50 to 4.11)), compared to women with schizophrenia not taking antipsychotics during pregnancy (Lin, 2010). The risk was not increased in women with schizophrenia treated with atypical antipsychotics during pregnancy compared to untreated women with schizophrenia (OR adj. 1.61 (95% CI 0.63 to 4.12), Lin, 2010).

Habermann (2013) reported crude OR’s for preterm deliveries in women taking atypical, typical and no antipsychotics. There was no difference between the risk of preterm delivery between women taking atypical antipsychotics and no antipsychotics (crude OR 1.06 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.56). However, women taking typical antipsychotics during pregnancy seemed to have a higher risk of preterm delivery compared with women not taking antipsychotics (crude OR 1.96 (95% CI 1.29 to 2.98); Habermann, 2013). Compared to users of typical antipsychotics, users of atypical antipsychotics had a lower (unadjusted) risk of preterm delivery (crude OR 0.54 (95% CI 0.33 to 0.87); Habermann, 2013).

Bellet (2015) found an increased rate of preterm delivery in women taking aripiprazole (atypical antipsychotic) compared to unexposed women, crude OR 2.57 (95% CI 1.06 to 6.27).

Compared to a healthy control group, women exposed to atypical antipsychotics in the study by Sadowski (2013) did not have statistically significantly higher rates of preterm deliveries (12 (10.6%)/ 5 (4.3%), p=0.071; crude OR 2.54 (95% CI 0.87 to 7.42); Sadowski, 2013).

In summary, the six studies investigating preterm delivery showed varying results. Four studies using a healthy control group reported an increased risk of preterm delivery in antipsychotic-exposed women (Reis, 2008; Vigod, 2015; Habermann, 2013; Bellet, 2015). One of the four studies reported an increased risk only for typical antipsychotics (Habermann, 2013), another two for any antipsychotics (as a group) (Vigod, 2015; Reis, 2008), and one study reported an increased risk for aripiprazole (Bellet, 2015). The risk of preterm delivery in users of typical antipsychotics was increased in comparison to untreated women with psychiatric disorders in one study (Lin, 2010). Four studies found no increase in risk of preterm delivery with atypical antipsychotics: two of these studies (Habermann, 2013; Sadowski, 2013) in comparison to healthy controls, and two studies (Lin, 2010; Vigod, 2015) compared to matched controls with psychiatric disorders.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures ‘neonatal mortality < 90 days postpartum’ and ‘neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admissions’ was based on observational studies and was downgraded by a very low level of evidence, due to imprecision (results from a single study) and indirectness.

The level of evidence regarding all other outcomes was based on observational studies and was downgraded to very low, because of risk of bias (methodological study limitations), inconsistency (conflicting results) and indirectness (limited applicability, considering the differences in comparison groups, outcome definitions and exposures).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the (un)favorable effects of antipsychotic use in pregnant women on the risk of neonatal symptoms and adverse neonatal outcomes, compared to no antipsychotic use or exposure to a different antipsychotic?

P: patients pregnant women with psychiatric disorders;

I: intervention treatment with antipsychotics;

C: control no antipsychotic treatment or treatment with a different antipsychotic (comparison between antipsychotics);

O: outcome neonatal mortality < 90 days postpartum, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admissions, neonatal hospitalization in the 1st month of life, low birth weight (< 2500 g), small for gestational age, large for gestational age, neonatal symptoms, preterm birth (< 37 weeks)

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered neonatal mortality < 90 days postpartum and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admissions as crucial outcome measures for decision making; and neonatal hospitalization in the 1st month of life, low birth weight (< 2500 g), small for gestational age, large for gestational age, neonatal symptoms (including neonatal abstinence syndrome) and preterm birth (< 37 weeks) as important outcome measures for decision making.

The minimal (clinically) important difference was defined according to the default recommendations of the international GRADE working group, as follows: for dichotomous outcomes as a relative risk reduction or an increase of 25% or more, and for continuous outcomes as a difference of half (0.5) a standard deviation.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from the 1st of January 1966 until the 21 of March 2019. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 111 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and comparative observational studies, assessing the risk of neonatal symptoms in infants of women with psychiatric disorders treated with antipsychotics during pregnancy, and comparing with women not treated with antipsychotics during pregnancy, or taking a different antipsychotic. Initially, 18 studies were selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 8 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and 10 studies were included.

Results

Ten comparative observational studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Prospectively collected data were retrieved via teratology information services, from population-based databases of electronic medical and birth records, as well as prescription and insurance databases. The unexposed group consisted of women without a history of psychiatric disorders in 6 studies (Bellet, 2015; Boden, 2012; Diav-Citrin, 2005; Habermann, 2013; Sadowski, 2013; Reis, 2008). In 2 studies, next to ‘healthy’ women, the comparison group also included a subgroup of women with psychiatric disorders who were not taking AP or had discontinued AP during pregnancy (Lin, 2010; Petersen, 2016), and another 2 studies included only women with psychiatric disorders (Suttar-Dallay, 2015; Vigod, 2015).

Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence table. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias table.

Referenties

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) (2008). Use of psychiatric medications during pregnancy and lactation Clinical Practice Guidelines. Retrieved from https://www.guidelinecentral.com/summaries/use-of-psychiatric-medications-during-pregnancy-and-lactation/#section-society.

- Bellet, F., Beyens, M. N., Bernard, N., Beghin, D., Elefant, E., & Vial, T. (2015). Exposure to aripiprazole during embryogenesis: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety, 24(4), 368-380.

- Bodén R, Lundgren M, Brandt L, Reutfors J, Kieler H. Antipsychotics during pregnancy: relation to fetal and maternal metabolic effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(7):715-721.

- Cohen, L. S., Góez-Mogollón, L., Sosinsky, A. Z., Savella, G. M., Viguera, A. C., Chitayat, D.,... & Freeman, M. P. (2018). Risk of major malformations in infants following first-trimester exposure to quetiapine. American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(12), 1225-1231.

- Courtet, P. (2001). Viewpoint of schizophrenic patients: a European survey. L'Encephale, 27(1), 28-38.

- Diav-Citrin, O., Shechtman, S., Ornoy, S., Arnon, J., Schaefer, C., Garbis, H.,... & Ornoy, A. (2005). Safety of haloperidol and penfluridol in pregnancy: a multicenter, prospective, controlled study. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 66(3), 317-322.

- Gentile, S. (2010). Antipsychotic therapy during early and late pregnancy. A systematic review. Schizophrenia bulletin, 36(3), 518-544.

- Habermann, F., Fritzsche, J., Fuhlbrück, F., Wacker, E., Allignol, A., Weber-Schoendorfer, C.,... & Schaefer, C. (2013). Atypical antipsychotic drugs and pregnancy outcome: a prospective, cohort study. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology, 33(4), 453-462.

- Hippman, C., & Balneaves, L. G. (2018). Women's decision making about antidepressant use during pregnancy: A narrative review. Depression and anxiety, 35(12), 1158-1167.

- Kothari, A., de Laat, J., Dulhunty, J. M., & Bruxner, G. (2019). Perceptions of pregnant women regarding antidepressant and anxiolytic medication use during pregnancy. Australasian Psychiatry, 27(2), 117-120.

- Lin, H. C., Chen, I. J., Chen, Y. H., Lee, H. C., & Wu, F. J. (2010). Maternal schizophrenia and pregnancy outcome: does the use of antipsychotics make a difference?. Schizophrenia research, 116(1), 55-60.

- McAllister-Williams, R. H., Baldwin, D. S., Cantwell, R., Easter, A., Gilvarry, E., Glover, V.,... & Khalifeh, H. (2017). British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus guidance on the use of psychotropic medication preconception, in pregnancy and postpartum 2017. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 31(5), 519-552.

- Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport (2018). Richtlijn ‘Bijwerkingen antipsychotica bij schizofrenie’. Retrieved from https://kansrijkestart.nl/

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2014) Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance (NICE Clinical Guideline CG192). Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg192.

- Nygaard, L., Rossen, C. B., & Buus, N. (2015). Balancing risk: a grounded theory study of pregnant women's decisions to (dis) continue antidepressant therapy. Issues in mental health nursing, 36(7), 485-492.

- Park, Y., Huybrechts, K. F., Cohen, J. M., Bateman, B. T., Desai, R. J., Patorno, E.,... & Hernandez-Diaz, S. (2017). Antipsychotic medication use among publicly insured pregnant women in the United States. Psychiatric services, 68(11), 1112-1119.

- Petersen, I., Sammon, C. J., McCrea, R. L., Osborn, D. P., Evans, S. J., Cowen, P. J., & Nazareth, I. (2016). Risks associated with antipsychotic treatment in pregnancy: comparative cohort studies based on electronic health records. Schizophrenia research, 176(2-3), 349-356.

- Reis M, Källén B. Maternal use of antipsychotics in early pregnancy and delivery outcome. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008 Jun;28(3):279-88.

- Sadowski A, Todorow M, Yazdani Brojeni P, Koren G, Nulman I. Pregnancy outcomes following maternal exposure to second-generation antipsychotics given with other psychotropic drugs: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013 Jul 13;3(7).

- Schoretsanitis, G., Westin, A. A., Deligiannidis, K. M., Spigset, O., & Paulzen, M. (2019). Excretion of antipsychotics into the amniotic fluid, umbilical cord blood, and breast milk: A systematic critical review and combined analysis. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring.

- Singh, K. P., & Tripathi, N. (2014). Prenatal exposure of a novel antipsychotic aripiprazole: impact on maternal, fetal and postnatal body weight modulation in rats. Current drug safety, 9(1), 43-48.

- Singh, K. P., Singh, M. K., & Gautam, S. (2016). Effect of in utero exposure to the atypical anti-psychotic risperidone on histopathological features of the rat placenta. International journal of experimental pathology, 97(2), 125-132.

- Singh, K. P., Singh, M. K., & Singh, M. (2016). Effects of prenatal exposure to antipsychotic risperidone on developmental neurotoxicity, apoptotic neurodegeneration and neurobehavioral sequelae in rat offspring. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience, 52, 13-23.

- Sutter-Dallay, A. L., Bales, M., Pambrun, E., Glangeaud-Freudenthal, N. M., Wisner, K. L., & Verdoux, H. (2015). Impact of prenatal exposure to psychotropic drugs on neonatal outcome in infants of mothers with serious psychiatric illnesses. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 76(7), 967-973.

- van Gelder, M. M., Rog, A., Bredie, S. J., Kievit, W., Nordeng, H., & van de Belt, T. H. (2019). Social media monitoring on the perceived safety of medication use during pregnancy: A case study from the Netherlands. British journal of clinical pharmacology, 85(11), 2580-2590.

- Vigod, S. N., Bagheri, E., Zarrinkalam, F., Brown, H. K., Mamdani, M., & Ray, J. G. (2018). Online social network response to studies on antidepressant use in pregnancy. Journal of psychosomatic research, 106, 70-72.

- Vigod, S. N., Gomes, T., Wilton, A. S., Taylor, V. H., & Ray, J. G. (2015). Antipsychotic drug use in pregnancy: high dimensional, propensity matched, population based cohort study. bmj, 350, h2298.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, case series))

Research question: What is the effect of antipsychotic use in pregnant women on neonatal symptoms, compared to women not using antipsychotics during pregnancy?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up

|

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Bellet, 2015 |

Type of study: retrospective analysis of prospective cohort data

Setting and country: pharmacovigilance and teratogenic risk reporting databases, France

Funding and conflicts of interest: non-commercial, none reported

|

Inclusion criteria: pregnant women who had contacted pharmacovigilance centres about the safety of their medication in pregnancy between July 2004 and December 2011

Exclusion criteria: duplicate database entries, not pregnant at the time of the first contact (preventive and retrospective cases), known developmental anomaly in fetus before the first contact (retrospective cases), ongoing pregnancy at 31 December 2011, follow-up data not available; patients were excluded from the exposed group if they were taking known teratogen(s) (e.g. carbamazepine, carbimazole, cyclophosphamide, lithium, methotrexate, misoprostol, mycophenolate, phenobarbital, retinoids, thalidomide, valproic acid, vitamin K antagonists) N total at baseline: (exposed/unexposed) N=86/N=172 *exposed only in the 1st trimester: n=56 *exposed in trimester 2 and 3: n=22 *exposed only in trimester 2: n=8

Mean age ± SD: (exposed/unexposed) N=77 /N=172 31.8 ± 5.8 yrs /31.4 ± 5.4 yrs

Smoking: (exposed/unexposed n=30/n=93) <5 cigarettes/day (%) 10/ 5.4 ≥5 cigarettes/day (%) 36.7/ 5.4

Alcohol: (exposed/unexposed n=29/n=90) <2 drinks/day (%) 17.2/ 8.9 ≥2 drinks/day (%) 3.4/ 0

Co-medications: 72.1% of exposed patients had co-medications (benzodiazepines, antidepressants, other antipsychotics and anticonvulsants)

Indications: schizophrenia (n=22; 30.6%), psychotic disorders not otherwise specified (n=14; 19.4%), bipolar disorders (n= 12; 16.7%), depression (n = 11; 15.3%) |

(exposed) use of aripiprazole (5 to 30 mg/day) throughout pregnancy or stopped <28 days before delivery

|

(unexposed) no use of aripiprazole, exposed to agents known to be non-teratogenic

2 random unexposed patients were matched for age (± 2 years) and gestational age at the first call (± 2weeks) with each exposed patient

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: ascertainment of outcomes within 2 months of the expected date of delivery

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (exposed/unexposed) N: 15/11

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? Yes (exposed: 8 miscarriages (9.3%), 8 voluntary abortions (9.3%) and 1 therapeutic abortion) (unexposed: 10 miscarriages (5.8%) and 3 voluntary abortions (1.7%))

|

Outcome measures: preterm birth (<37 weeks), foetal growth retardation (birth weight <10th percentile for gestational age according to the Audipog reference curve), neonatal symptoms

Effect estimates: preterm birth (exposed n=67 /unexposed n=155) OR 2.57 (95% CI 1.06–6.27) fetal growth retardation (FGR) (exposed n=63 /unexposed n=150) OR 2.97 (95% CI 1.23–7.16) mean birth weight ± SD (exposed n=54/ unexposed n=139) 3268 ± 484 g/ 3339 ± 462 g neonatal symptoms (n=2) -withdrawal syndrome n=1 (mother co-treated with methadone) -amniotic fluid aspiration pneumonia n=1

|

authors’ conclusions: -the rates of preterm birth and FGR among singletons were statistically increased by more than a factor of 2 in the exposed group (19%) compared to the unexposed group (7.3%), but many factors, such as the duration of exposure to aripiprazole, co-medication and smoking were not taken into account -the two reported cases of neonatal symptoms could be explained by maternal factors and delivery complications

-analyses were not adjusted for potential confounders

|

|

Boden, 2012 |

Type of study: population-based cohort

Setting and country: Swedish Prescribed Drug Register, Medical Birth Register, National Patient Register, Sweden

Funding and conflicts of interest: non-commercial; none reported |

Inclusion criteria: all women giving birth in Sweden from July 1, 2005 to December 31, 2009

Exclusion criteria: prescriptions for prochlorperazine, levomepromazine, melperone, lithium

N total at baseline: (exposed olan. + cloz./ exposed other AP/ unexposed) N=169/ N=338/ N=357,696

Mean age ± SD: only categories

Smoking (exposed/unexposed): (38 (22.5)/107 (31.7))/ 24,007 (6.7)

Alcohol: not reported

Co-medications: not reported; 87.9% used only 1 AP throughout pregnancy

Indications, n (%): (exposed olan.+ cloz./ exposed other AP/ unexposed) -schizophrenia 42 (24.9)/64 (18.9)/ 117 (0.03) -other nonaffective psychosis 34 (20.1)/ 55 (16.3)/ 459 (0.1) -bipolar disorder 20 (11.8)/37 (10.9)/749 (0.2) |

(exposed) AP at any time during pregnancy 1. olanzapine (n=159) and/or clozapine (n=11) 2. all other AP, excluding olanzapine and clozapine (n, %): -quetiapine 90 (17.8) -risperidone 72 (14.2) -flupentixol 58 (11.4) -haloperidol 52 (10.3) -aripiprazole 38 (7.5) -perphenazine 35 (6.9) -zuclopenthixol 30 (5.9) -ziprasidone 18 (3.6) -chlorprothixene 9 (1.8) -fluphenazine 2 (0.4) -pimozide 1 (0.2)

|

(unexposed) no AP during pregnancy |

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: N/A

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A

|

Outcome measures: small for gestational age ≤2.3rd percentile; large for gestational age at ≥97.7th percentile of the total population by infant sex; preterm birth (<37 weeks)

Effect estimates: 1. olanzapine/clozapine preterm birth, 8% in this group small for gestational age -birth weight ORadj. 1.82 (95% CI 0.91-3.61) -birth length ORadj. 1.17 (95% CI 0.54-2.55) -head circumference ORadj. 0.62 (95% CI 0.19-2.01) large for gestational age -birth weight ORadj. 0.55 (95% CI 0.14-2.11) -birth length ORadj. 1.94 (95% CI 0.87-4.34) -head circumferenced ORadj. 3.02 (95% CI 1.60-5.71)

2. other AP preterm birth, 9.5% in this group small for gestational age -birth weight ORadj. 1.24 (95% CI 0.72-2.15) -birth length ORadj. 1.35 (95% CI 0.79-2.28) -head circumference ORadj. 1.64 (95% CI 0.97-2.77) large for gestational age -birth weight ORadj. 1.37 (95% CI 0.69-2.75) -birth length ORadj. 0.96 (95% CI 0.40-2.29) -head circumference ORadj. 0.67 (95% CI 0.25-1.76) |

authors’ conclusions: -unadjusted increased risk of being SGA, but after adjusting for maternal factors, not stat. sig. -increased risk for LGA for head circumference (macrocephaly) after exposure to olanzapine and/or clozapine

-adjusted for maternal country of origin, smoking, height, cohabitation, maternal age at partus, birth order of infant; BMI (only for preterm birth) |

|

Diav-Citrin, 2005 |

Type of study: multicentre prospective controlled cohort

Setting and country: multicentre (Israel, Netherlands, Germany, Italy); European network of teratology information services, used data from Teratology Information Services in each country

Funding and conflicts of interest: non-commercial; none reported

|

Inclusion criteria: pregnant women who (or whose physician or midwife) contacted the teratology information service about the safety of gestational exposure to medication in 1989-2001

Exclusion criteria: none reported

N total at baseline: (exposed/unexposed) 215/631

Median age, yrs: (exposed/unexposed) (exposed/unexposed) 32/30 (stat. sig. different between exposed and unexposed)

BMI: not reported

Smoking: (exposed/unexposed) ≤5 cigarettes/day (n=157) 6 (3.8%)/20 (3.6%) >5 cigarettes/day (n=562) 34 (21.7%)/ 33 (5.9%), p<0.001

Alcohol: not reported

Co-medications (%): any other concomitant psychotropic medication (75.1), concomitant anti-cholinergic drugs (31.6)

Indications (%): psychosis (33.5), schizophrenia (10.7), depression (9.3), bipolar disorder (4.2), schizoaffective disorder (1.4), anxiety (1.4), panic attacks (0.9), hyperemesis gravidarum (0.5), borderline personality disorder (0.5), suicide attempt (0.5), substance abuse (0.5), Tourette syndrome (0.5); not specified (36.1) |

(exposed) haloperidol, penfluridol during pregnancy

(oral haloperidol, median dose 5 mg (2.25-10 mg) daily, parenteral haloperidol, median dose 100 mg/4 weeks (50-100 mg); oral penfluridol, median dose 20 mg/week (20-40 mg))

in the 1st trimester: haloperidol n=136; penfluridol n=25

|

(unexposed) not exposed to haloperidol or penfluridol, but took drugs which are known to be nonteratogenic

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: between the neonatal period and 6 years of age; in most cases within the 1st 2 years of life

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N/A

follow-up rate ranged from 63% to 100% depending on the study center

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

Outcome measures: premature births, gestational age at delivery, birth weight, neonatal effects

Effect estimates: (exposed versus unexposed) 13.9%/ 6.9%, p=0.006 -median gestational age at delivery (IQR) 40 (38-40)/ 40 (39-41) -median birth weight (overall, IQR) 3155 (2800-3500) g/ 3370 (3030-3700) g, p<0.001 -median birth weight (full term infants, IQR) 3250 (3000-3590) g/3415 (3140-3750) g, p=0.004 -prevalence of neonatal effects: 5% (9/179)

neonatal effects reported were: hyperexcitability, transient muscular hypotonia, respiratory problems, hypertonia/irritability/arrhythmia, jitteriness, restlessness, feeding problems, no cry at birth/lethargy

|

authors’ conclusions: -there was a reduced birth weight and a 2x increased rate of preterm birth in the exposed group -the lower weight is partly explained by earlier gestational age and higher rate of preterm births -in most cases of neonatal effects concomitant use of other drugs late in pregnancy was reported (including benzo’s)

no adjustment for confounders |

|

Lin, 2010 |

Type of study: population-based prospective cohort

Setting and country: Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (1996-2003) and birth certificate registry (2001-2003); School of Health Care Administration, Taipei Medical University, Taiwan

Funding and conflicts of interest: non-commercial; none |

Inclusion criteria: women who had singleton live births from 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2003, with at least 3 consecutive records of diagnostic codes for schizophrenia within 3 years preceding pregnancy, AP prescription > 30 days during pregnancy

Exclusion criteria: (exposed) taking both typical and atypical AP during pregnancy, injectable AP, antiepileptics, lithium, atypical or atypical AP for less than 30 days during pregnancy (unexposed): records of mental illness or chronic diseases systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, sarcoidosis, ankylosing spondylitis

N total at baseline (maternal): (exposed/unexposed diseased/ unexposed) N=242/N=454/N=3480

Mean maternal age: N/A

Paternal age (%), p=0.004: (exposed/unexposed) <30: 32.8/ 28 30–34: 37.8/ 36.6 ≥34: 29.4/ 35.3

Indications: schizophrenia (any ICD-9-CM 295 code other than 295.7-schizoaffective disorder)

Smoking: N/A Alcohol: N/A Substance abuse: N/A Co-medications: N/A |

(exposed) 1. typical AP (n=194) 2. atypical AP (n=48)

|

(unexposed) 1. diseased + no AP during pregnancy (n=454) 2. healthy + no AP (n=3480)

randomly matched by age categories (<20, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, ≥35 yrs), year of delivery, hypertension, diabetes in a 1:5 ratio

compared exposed with diseased unexposed and healthy unexposed with diseased unexposed (as ref.) |

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: N/A

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

Outcome measures: low birth weight (<2500 g), preterm gestation (<37 weeks), SGA (birth weight <10th percentile for gestational age), LGA (birth weight >10th percentile for gestational age)

Effect estimates: 1. typical AP versus diseased unexposed, adjusted OR’s low birth weight (<2500 g) OR 0.95 (95% CI 0.50–1.75) preterm birth (<37 weeks) small for gestational age OR 1.39 (95% CI 0.93–2.08) large for gestational age OR 0.72 (95% CI 0.39–1.34)

2. atypical AP versus diseased unexposed, adjusted OR’s low birth weight (<2500 g) OR 1.71 (95% CI 0.67–4.34) preterm birth (<37 weeks) OR 1.61 (95% CI 0.63–4.12) small for gestational age OR 1.15 (95% CI 0.55–2.41) large for gestational age OR 0.55 (95% CI 0.16–1.85) |

authors’ conclusions: -typical AP during pregnancy were associated with an increased risk of preterm birth (after adjusting for confounders) -women receiving atypical AP did not have an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes -no increased risk of LGA among women with schizophrenia taking atypical AP

adjusted for infant gender, parity, maternal age, highest maternal and paternal educational levels, hypertension, gestational diabetes, parental age difference, mother marital status, family monthly income

parental ages were defined as each parent's age at the time of birth |

|

Sutter-Dallay, 2015 |

Type of study: retrospective analysis of (mostly) prospective data

Setting and country: database of the French Network of Mother-Baby Units, France

Funding and conflicts of interest: non-commercial; none reported |

Inclusion criteria: women ≥18 yrs with psychiatric disorders consecutively admitted jointly with their children (<1 yrs) to mother-baby units in 2001-2010, hospitalized for ≥5 days, gave informed consent

Exclusion criteria: N/A

N total at baseline: (exposed/unexposed) all AP N=267/ N=640 (N separately FGA and SGA unclear)

The following characteristics were presented only for exposed to all psychotropic medications (not separately for AP) n=431/n=640

Mean age ± SD: (exposed/unexposed) 32.5 ± 5.9 yrs/ 30.8 ± 6.1 yrs

Smoking (n, %): (exposed/unexposed) 216 (50.1) /160 (25.0), p<0.0001

Indications (n, %): -mood disorders 159 (36.9)/ 262 (40.9) -psychotic disorders 132 (30.6)/ 111 (17.3) -other mental disorders 140 (32.5)/ 267 (41.7)

Co-medications: N/A Alcohol: N/A |

(exposed) AP any time during pregnancy

(FGA (phenothiazines, butyrophenones, diazepines, oxazepanes, thioxanthenes) and SGA (amisulpride, risperidone, olanzapine, aripiprazole, clozapine))

|

(unexposed) had psychiatric disorders, no AP use during pregnancy |

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: N/A

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

Outcome measures: low birth weight (LBW, <2500 g), preterm birth (<36 weeks), neonatal hospitalization in the 1st month of life

information about the outcomes was collected through the Marcé Clinical checklist

exposure collected from mother’s recall and from medical records

Effect estimates, adjusted OR: Low birth weight: OR 0.89 (95% CI 0.62-1.55), p=0.92 preterm birth (<36 weeks): p=0.99

neonatal hospitalization*: OR 1.74 (95% CI 1.19-2.54), p=0.004

*restricting to term neonates (≥36 weeks) OR 2.11 (95% CI 1.36-3.27), p=0.001 *restricting to birth weight ≥2500 g OR 1.91 (95% CI 1.17-3.10), p=0.01 *restricting to birth weight <2500 g OR 2.98 (95% CI 1.01-8.84) p=0.05 |

authors’ conclusions: -there was a high frequency of postnatal hospitalizations in the AP group -did not confirm a high risk of low birth weight for FGA and SGA or preterm birth for SGA reported in other studies

adjusted for maternal age, education level, parity, presence of a partner, maternal diagnosis, type of unit, smoking |

|

Vigod, 2015 |

Type of study: population based cohort study (retrospective analysis of prescription and medical records databases)

Setting and country: multiple linked population health databases housed at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) in Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Funding and conflicts of interest: grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), and by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; author’s funding had no impact on the results and interpretation of the study

|

Inclusion criteria: women who delivered a singleton infant in Ontario between 2003 and 2012, who were eligible for provincially funded drug coverage, and who had filled a provincially funded drug prescription within 180 days before pregnancy and one during pregnancy or within 180 days of delivery

Exclusion criteria: absence of provincially funded drug coverage

N total at baseline: (exposed/unexposed) n=1,209/n=40,314 (unmatched cohort) n=1,021/n=1,021 (matched cohort)

Mean age ± SD: (exposed/unexposed) 28.8±6.1/ 26.7±6.3 yrs (unmatched cohort) 28.8±6.2/ 28.8±6.2 yrs (matched cohort)

BMI: not reported

Alcohol and smoking (substance disorder), N(%) (exposed/unexposed) 569 (47.1)/ 5523 (13.7) (unmatched) 458 (44.9)/ 415 (40.7) (matched)

Co-medications, N(%): (exposed/unexposed)

1.unmatched cohort -SSRI 364 (30.1)/ 1981 (4.9) -Non-SSRI 322 (26.6)/ 989 (2.5) -Mood stabilisers 167 (13.8)/ 331 (0.8) -Benzodiazepines 306 (25.3)/ 630 (1.6)

2. matched cohort: -SSRI 303 (29.7)/ 204 (20) -Non-SSRI 264 (25.9)/ 149 (14.6) -Mood stabilisers 105 (10.3)/ 62 (6.1) -Benzodiazepines 222 (21.7)/ 135 (13.2)

Indications, n(%): (exposed/unexposed)

1. unmatched cohort: -Psychotic disorder 429 (35.5)/ 675 (1.69) -Bipolar disorder or major depression 937 (77.5)/ 8708 (21.6) -Personality disorder 393 (32.5)/ 1816 (4.5)

2. matched cohort: -Psychotic disorder 319 (31.2)/ 160 (15.7) -Bipolar disorder or major depression 758 (74.2)/ 673 (65.9) -Personality disorder 295 (28.9)/ 231 (22.6) |

(exposed) ≥2 consecutive prescriptions for AP between the conception date (estimated using the gestational age at birth) and the delivery date; at least one of the prescriptions was filled in the 1st or 2nd trimester

|

(unexposed) psychiatric disorders in most of the women in the matched cohort and in some of the women of the unmatched cohort, no AP during pregnancy

unexposed matched 1:1 to AP patients using propensity scores (based on the HDPS score within 0.2 SD) and on maternal age at delivery within 3 years

|

Duration of end-point follow-up: 180 days after delivery for exposure, 42 days for the outcome data

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

Outcome measures: preterm birth (<37 weeks, <32 weeks, <28 weeks), SGA (birth weight <3rd centile and <10th centile), LGA (birth weight >90 centile and >97th centile), respiratory distress syndrome, seizure, sepsis, intraventricular hemorrhage, persistent fetal circulation, neonatal adaptation syndrome, congenital or neonatal infection, neonatal mortality <90 days

Effect estimates: 1. unmatched cohort preterm birth (<37 weeks) preterm birth (<32 weeks) RR 1.61 (95% CI 1.19 - 2.16) preterm birth (<28 weeks) RR 1.20 (95% CI 0.80 - 1.82) small for gestational age (<3rd centile) RR 1.20 (95% CI 0.95 - 1.53) small for gestational age (<10th centile) RR 1.33 (95% CI 1.15 - 1.54) large for gestational age (>97th centile) RR 1.44 (95% CI 1.06 -1.96) large for gestational age (>90 centile) RR 1.18 (95% CI 0.97 - 1.45) respiratory distress syndrome RR 1.87 (95% CI 1.31 - 2.66) seizure RR 4.30 (95% CI 2.22 - 8.33) sepsis RR 2.26 (95% CI 1.53 - 3.32) intraventricular hemorrhage RR 2.84 (95% CI 1.53 to 5.27) persistent fetal circulation N/A (n≤5) neonatal adaptation syndrome RR 7.06 (95% CI 5.91 - 8.45) congenital or neonatal infection RR 1.61 (95% CI 0.75 - 3.45) neonatal mortality <90 days RR 1.64 (95% CI 0.84 - 3.20)

2. matched cohort, adjusted RR preterm birth (<37 weeks) RR 0.99 (95% CI 0.78 - 1.26) preterm birth (<32 weeks) RR 0.85 (95% CI 0.53 - 1.36) preterm birth (<28 weeks) RR 0.48 (95% CI 0.25 - 0.93) small for gestational age (<3rd centile) RR 1.21 (95% CI 0.81 - 1.82) small for gestational age (<10th centile) RR 1.20 (95% CI 0.97 - 1.50) large for gestational age (>97 centile) RR 1.26 (95% CI 0.69 - 2.29) large for gestational age (>90 centile) RR 1.07 (95% CI 0.76 - 1.51) respiratory distress syndrome RR 0.82 (95% CI 0.46 - 1.43) seizure (UNADJUSTED) RR 1.29 (95% CI 0.48 - 3.45) sepsis RR 1.80 (95% CI 0.84 - 3.85) intraventricular hemorrhage N/A persistent fetal circulation N/A neonatal adaptation syndrome RR 1.15 (95% CI 0.88 - 1.50) congenital or neonatal infection N/A neonatal mortality <90 days N/A |

author’s conclusions: -in itself AP use in pregnancy poses a minimal risk for adverse outcomes for the pregnant woman and her fetus, but the rates of adverse perinatal outcomes observed in the matched cohort of antipsychotic users were higher than in the unmatched controls or in the general population - the sevenfold increased risk for neonatal adaptation syndrome in the unmatched cohort was reduced to a small, non-significant relative risk in the matched cohort; this suggests that neonatal adaptation syndrome following antenatal AP exposure could be attributable to other factors, such as increased rates of concomitant medication use, substance use, or alcohol

adjusted for the use of SSRI, non-SSRI, mood stabilisers (lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine), or benzodiazepines in the same pregnancy (matched cohort)

for the unmatched cohort unadjusted estimates are shown |

|

Habermann, 2013 |

Type of study: prospective cohort

Setting and country: Institute for Clinical Teratology and Drug Risk Assessment in Pregnancy, using data from Teratology Information Service (TIS), Germany

Funding and conflicts of interest: non-commercial; none reported

|

Inclusion criteria: all pregnant women consulted at Teratology information service from January 1997 to March 2009

Exclusion criteria: presence of prenatal pathologic findings; outcome of the pregnancy was known at the time of inclusion

N total at baseline: (exposed/unexposed) N=845 (study cohort n=561 + cohort 1 n=284))/ N=1122 (cohort 2)

Median age: (exposed/unexposed) 32/32 yrs

Median BMI: (exposed/unexposed) 24.2/23.7 kg/m2

Smoking (study cohort/cohort 1/cohort2(unexp.)) (n=529/n=264/n=1111) ≤5 cigarettes/day 27 (5.1%)/ 15 (5.7%)/ 42 (3.8%) >5 cigarettes/day (n=562) 176 (33.3%)/ 98 (37.1%)/ 58 (5.2%)

Alcohol (study cohort/cohort 1/cohort2(unexp.)) (n=526/n=263/n=1112) ≤1 drink/day 23 (4.4%)/ 11 (4.2%)/ 24 (2.2%) >1 drink/day 14 (2.7%)/ 13 (4.9%)/ 3 (0.3%)

Co-medications (only psychotropic): (exposed) total other psychoactive drugs, including antidepressants, anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, anxiolytics/sedatives, opioids (58%)

Indications: psychotic disorders, schizophrenia, depression, bipolar affective disorders, anxiety disorders |

(exposed) study cohort: exposed to SGA (concomitant FGA allowed): olanzapine (n = 187), quetiapine (n = 185), clozapine (n = 73), risperidone (n = 64), aripiprazole (n = 60), ziprasidone (n = 37), amisulpride (n = 16), zotepine (n = 2) cohort 1: exposed only to FGA (the most frequent were: haloperidol (n = 64), promethazine (n = 86), flupentixol (n = 44))

|

(unexposed) cohort 2: no antipsychotic use; excluded all women exposed to known teratogenic, fetotoxic or insufficiently studied drugs, allowed drugs known to be nonteratogenic; used a random sample from this cohort in 2:1 ratio |

Duration of end-point follow-up: 8 weeks after the estimated date of birth (via hospital discharge summaries)

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (exposed/unexposed) 18.3%/17.4% lost to follow-up

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

Outcome measures: rate of preterm births (<37 weeks), postnatal disorders (composite outcome of respiratory, digestive, cardiac, nervous system disorders and multiple system disorders)

Effect estimates: postnatal disorders (considering live-borns exposed at least during the last gestational week): adjusted ORs -study cohort versus cohort 2: OR 6.24 (95% CI 3.51-11.10); -cohort 1 versus. cohort 2: OR 5.03 (95% CI, 2.21-11.44)

preterm birth, n (%) (study cohort/cohort 1/cohort 2) 41 (9.2)/ 36 (15.7)/ 88 (8.7)

|

authors conclusions: -the rates of postnatal symptoms were 15.6% of infants exposed to SGA and 21.6% exposed to FGA, significantly higher than the rate of 4.2% in comparison group -high rates of neonatal symptoms could be explained by concomitant of other psychotropic drugs and underlying disease of the mother -increased rate of preterm births could be explained by concomitant use of ADD, which have earlier been associated with preterm birth -quetiapine, risperidone, and olanzapine are a treatment of choice in pregnant women requiring AP therapy

adjusted analyses for alcohol >1 drink per day, smoking (>5 cigarettes/d), and gestational week at delivery |

|

Sadowski, 2013 |

Type of study: retrospective analysis of a prospective cohort (prescription database data)

Setting and country: Motherisk Program at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada

Funding and conflicts of interest: non-commercial; none reported

|

Inclusion criteria: all women who contacted the Motherisk services between 2005 and 2009 regarding the use of AP and other drugs in the current pregnancy

Exclusion criteria: exposure to teratogenic medications unrelated to the psychiatric disorder treatment; substance abuse (eg, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, heroin, etc); fertility-assisted pregnancies, twin or triplet pregnancies, pregnancies with known outcomes at the initial time of contact (eg, contacted Motherisk following the birth, reported abnormal pregnancy screening tests and/or ultrasounds); presence of psychiatric disorders in women of the comparison cohort

N total at baseline: (exposed/unexposed) N=133/ N=133

Mean age at conception ± SD (months): (exposed/unexposed) 378.3±61.8/ 383.6±53.9

BMI: not reported

Pre-pregnancy weight (kg): (exposed/unexposed) 74.3±20.9/ 64.6±13.0, p<0.001

Smoking N (%) (exposed/unexposed) 24 (18)/ 0 (0), p<0.001

Alcohol, N (%) (exposed /unexposed) 8 (6)/12 (9.1)

Co-medications (only psychotropic), N(%): (exposed)c 72.2% total; 54.1% combination with antidepressants; SSRI n=46 (34.6), benzodiazepine n=21 (15.8), anticonvulsants n=19 (14.3), SNRI n=16 (12.0), atypical antidepressant n=12 (9), non-benzo hypnotic n=8 (6), typical antipsychotic n=5 (3.8), serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor n=4 (3), tetracyclic antidepressant n=4 (3), tricyclic antidepressant n=3 (2.3), norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor n=2 (1.5), synthetic cannabinoid n=2 (1.5), psychostimulant n=1 (0.8), GABA analogue n=1 (0.8), other dopamine antagonist n=1 (0.8)

Indications (%): bipolar disorder (36.8), depression (27.1), anxiety and depression (9.8) sleep disorders (9.8), schizophrenia (3), schizoaffective disorders (1.5) |

(exposed) women who initially called the service to inquire about the safety of an SGA and who confirmed the use of this medication for a minimum of 4 weeks of pregnancy

(quetiapine (69.9%), olanzapine (16.5%), risperidone (10.5%), aripiprazole (1.5%), paliperidone (0.8%), quetiapine plus olanzapine (0.8%))

|

(unexposed) women who contacted Motherisk between 2005 and 2009 and reported exposure to non-teratogenic agents

matched for age at conception (±3 years) and pregnancy duration at the initial time of contact (±2 weeks) |

Duration of end-point follow-up: between 2009 and 2012

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? of 370 women who contacted Motherisk in the study period, 107 women could not be reached at their last reported contact details, 20 refused participation, 110 did not meet the inclusion criteria

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? yes |