Antipsychotica tijdens zwangerschap en aangeboren afwijkingen

Uitgangsvraag

Welke antipsychotica hebben de voorkeur voor gebruik in de zwangerschap met betrekking tot het risico op aangeboren afwijkingen?

Aanbeveling

Start bij voorkeur met haloperidol bij vrouwen in de fertiele levensfase bij een indicatie voor klassieke antipsychotica vanuit het perspectief van risico op congenitale afwijkingen.. Indien er indicatie bestaat voor een atypisch antipsychoticum, dan hebben quetiapine of olanzapine de voorkeur.

Overwegingen

De kwaliteit van het bewijs

De kwaliteit van het voorhanden zijnde bewijs is zeer laag. Het bewijs is voornamelijk gebaseerd op cohortstudies, waarbij drie van de acht studies retrospectief zijn. Er zijn geen RCT’s beschikbaar. Het aantal blootgestelde kinderen is, met name in de studies over de individuele middelen, zeer beperkt. Ook is de informatie over confounders, ernst van maternale ziekte, polyfarmacie en kenmerken van de controlegroepen zeer beperkt. Het is onduidelijk in hoeverre beëindigde zwangerschappen in de verschillende studies geïncludeerd zijn en wat de reden van het beëindigen was. Er is onvoldoende informatie over het beloop in de zwangerschap en het beloop van medicatiegebruik tijdens de zwangerschap.

Tabel 1 laat zien dat het totaal aantal beschreven blootgestelde zwangerschappen in de door ons geselecteerde studies 13375 is. Hoewel een verhoogd risico op basis van de huidige gegevens niet uit te sluiten is, lijkt de kans op een zeer ernstig verhoogd risico op structurele congenitale afwijkingen gering waarbij we een relatief grote groep zwangerschappen mee kunnen nemen.

Op basis van de gerapporteerde studies kan geen eenduidige conclusie getrokken worden ten aanzien van een eventuele verhoogde kans op congenitale afwijkingen. Anderzijds is er ook geen consistent verhoogd risico op een specifiek patroon van congenitale afwijkingen.

Overige geraadpleegde bronnen

Ook buitenlandse richtlijnen en beschouwende artikelen refereren aan het gebrek aan voldoende conclusieve studies. De NICE-richtlijn van 2014 (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2014) adviseert ‘When choosing an antipsychotic, take into account that there are limited data on the safety of these drugs in pregnancy and the postnatal period.’

De richtlijn van de American Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists dateert van 2008 en maakte geen gebruik van een systematische literatuurstudie. Deze richtlijn adviseert ten aanzien van typische antipsychotica; ‘Typical antipsychotics have a larger reproductive safety profile; no significant teratogenic effect has been documented with chlorpromazine (Thorazine), haloperidol (Haldol), or perphenazine (Trilafon). Doses of typical antipsychotics should be minimized during the peri-partum period to limit the necessity of using additional medications to manage extrapyramidal side effects.’ (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2008). Ten aanzien van atypische antipsychotica: ‘Therefore, the routine use of these drugs during pregnancy and lactation is not recommended.’ (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2008).

The richtlijn van de British Association of Pharmacologists (BAP) dateert van 2017 en verwijst naar literatuur, die niet bleek te voldoen aan de kwaliteitscriteria die gehanteerd werden voor deze richtlijn (McAllister-Williams, 2017). De BAP-richtlijn benoemt een verhoogd risico op major congenitale afwijkingen bij antipsychoticagebruik tijdens de zwangerschap, voor zowel typische als atypische antipsychotica. Zij baseren zich bij deze uitspraak onder andere op systematic reviews die wij in onze search uiteindelijk hebben geëxcludeerd; Coughlin (2015) (exclusie in verband met een gepoolde studies met uiteindelijk een te heterogene populatie), Gentile (2010) (exclusie omdat de studie niet overeen kwam met de PRISMA checklist, geen meta-analyse) en Terrana (2015) (exclusie aangezien het een meta-analyse betrof zonder full text). Van de 3 originele studies die zij aanhalen, hebben wij Petersen (2016) en Vigod (2015) ook geïncludeerd, maar Cohen (2016) hebben wij vervangen door een nieuwe publicatie uit 2018 van dezelfde groep, waarbij voor het grootste deel dezelfde populatie werd gebruikt. De voorzichtigheid die wij betrachten bij uitspraken over congenitale afwijkingen is dus op meer studieresultaten gebaseerd.

Het teratologie informatiecentrum (TIS) van Lareb (LAREB, 2020) benoemt voor de typische antipsychotica: ‘Bij de toepassing van klassieke antipsychotica tijdens de zwangerschap gaat de voorkeur uit naar haloperidol. Het is onbekend of de overige klassieke antipsychotica gebruikt kunnen worden tijdens de zwangerschap.’ Voor de atypische antipsychotica benoemt het TIS dat ‘quetiapine, olanzapine en aripiprazol gebruikt kunnen worden tijdens de zwangerschap. Het is onbekend of de overige middelen veilig gebruikt kunnen worden tijdens de zwangerschap’. Voor asenapine, clozapine, lurasidon, paliperidon, risperidon en sertindol wordt vermeld dat het risico onbekend is.

Samengevat is de overige literatuur, zoals hier beschreven niet eenduidig ten aanzien van het risico op aangeboren afwijkingen. We durven te stellen dat wij voldoende compleet zijn geweest ten aanzien van de geraadpleegde literatuur en studies gezien ook de 13375 geïncludeerde zwangerschappen (tabel 1), die er tot op heden beschikbaar zijn gesteld. Hoewel deze kennis nog steeds lacunes en beperkingen laat zien, kunnen we op dit moment stellen dat er bij gebruik van de verschillende antipsychotica geen ernstige aangeboren afwijkingen zijn aangetoond. Bij counseling adviseren we waar mogelijk te werken met absolute risico’s om dit risico uit te leggen.

De NVOG Leidraad indicatiestelling prenatale diagnostiek beschrijft de indicaties voor geavanceerd ultrageluidsonderzoek bij gebruik van (teratogene) medicatie of genotsmiddelen.

Farmacologische overwegingen

Bij de keuze van een antipsychoticum worden verschillende factoren meegenomen, zoals de effectiviteit, methode van toediening, incidentie dan wel ervaring van bijwerkingen, de effectiviteit bij terugvalpreventie en veiligheid tijdens de zwangerschap individueel worden afgewogen. Ten aanzien van de aangeboren afwijkingen is het van belang te overwegen in welke mate medicatie daadwerkelijk bij de foetus terecht komt. Gegevens over transplacentaire passage en dierexperimentele gegevens kunnen bij deze beslissing meewegen.

De gegevens ten aanzien van transplacentaire passage zijn zeer beperkt. Een systematische review (Schoretsanitis, 2019), die de transplacentaire passage beschrijft in totaal 72 cases aan de hand van een vergelijking van navelstrengbloed met maternaal bloed, vermeldt de volgende gemiddelde passages (van laag naar hoog): active moiety of aripiprazole (mean 0.22), quetiapine 0,24 (range 0.13 to 0.32), flupentixol LAI (mean 0.22, range 0.14 to 0.35), paliperidone LAI 0,35 (range 0.50 to 0.58), haloperidol van 0,66 (SD 0,40), olanzapine (mean 0.71, standard deviation, SD, 0.42). De zeer beperkte beschikbare gegevens leiden tot inconclusiviteit ten aanzien van de placentaire passage, hoewel de passage van aripiprazol en quetiapine binnen de bestudeerde groep van antipsychotica relatief laag lijkt.

Ook dierexperimentele studies zijn zeer beperkt. Een systematische review uit 2010 geeft een overzicht van aanvullende gegevens ten aanzien van teratogeniciteit (Gentile, 2010). In deze review zijn ook case-studies geïncludeerd en wordt de achtergrond ten aanzien van dierexperimentele studies weergegeven. De in dit artikel gerefereerde studies laten voor haloperidol slechts zeldzaam teratogeniciteit zien. Daarentegen laten studies voor aripiprazol een verhoogde kans op structurele afwijkingen zien, maar wel met doses 3 tot 10 keer hoger dan de therapeutische dosering. Ten aanzien van clozapine (2 tot 4 keer de therapeutische dosis), olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidon en sertindol laten dierexperimentele studies geen verhoogd risico op structurele afwijkingen zien. In studies met specifiek aripiprazol en risperidon werd een verminderde foetale groei gerapporteerd in ratten die hieraan werden blootgesteld, maar zonder aangeboren afwijkingen (Singh, 2016). Samengevat is de informatie vanuit dierexperimentele studies beperkt waarbij er geen duidelijke aanwijzingen zijn voor aangeboren afwijkingen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten

Er is vrijwel geen literatuur ten aanzien van de waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, die een rol spelen bij de besluitvorming rondom het gebruik van antipsychotica ten tijde van de zwangerschap. Vanzelfsprekend speelt het bijwerkingenprofiel een rol bij de voorkeuren van patiënten, evenals buiten de zwangerschap. Onderzoek bij zwangeren die anxiolytica en antidepressiva gebruiken en zwanger worden, laat zien dat de mogelijke invloed op het (ongeboren) kind een belangrijke overweging is om medicatie te staken (Kothari, 2019). Het afwegen van de risico’s en de meest veilige beslissing nemen wordt ook genoemd als een belangrijk thema (Nygaard, 2015). Echter, of dit ook geldt voor patiënten die antipsychotica gebruiken is naar onze kennis niet onderzocht.

Een nationale studie in de VS laat zien dat 50% van de vrouwen die atypische antipsychotica gebruikt in de drie maanden voorafgaand aan de zwangerschap, deze staakt tijdens de zwangerschap. Het is niet waarschijnlijk dat al deze vrouwen de antipsychotica gebruikten in verband met een psychotische stoornis. Aangezien het een register studie betrof, is de reden van staken niet bekend (Huybrechts, 2017). Vanuit de richtlijn antipsychotica gebruik blijkt dat subjectief welbevinden een belangrijke maat is voor het continueren van het antipsychoticum (Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie, 2012). Vanzelfsprekend speelt ook het bijwerkingen profiel hierin mee. De ‘betere naam' die de atypische antipsychotica kregen vergeleken met de typische antipsychotica is een factor geweest bij de acceptatie van gebruik (Courtet, 2001). Daarnaast speelt in vrouwen met depressie het stigma van de psychiatrische stoornis een rol bij besluitvorming rondom het gebruik van psychotrope medicatie (Hippman, 2018). Dit zal bij patiënten met een psychose gevoeligheid niet anders liggen, hoewel niet specifiek onderzocht. Onderzoek naar activiteit op sociale media in relatie met wetenschappelijke publicaties rondom antidepressivagebruik tijdens de zwangerschap liet een verdubbeling zien van deze activiteit bij studies, waarbij er een associatie was met studies die een risico beschreven en er alleen relatieve risico’s (en niet de absolute risico’s) genoemd worden in de samenvatting. Dit suggereert dat een mogelijk risico van medicatiegebruik tijdens de zwangerschap een belangrijk thema is (Vigod, 2018). Een recente studie vanuit het Radboud UMC liet zien dat veel zwangeren in hun zoektocht naar informatie over zwangerschap en medicatiegebruik veel onjuiste informatie tegenkomen, hetgeen hun beslisvorming in negatieve zin kan beïnvloeden (van Gelder, 2019).

Samenvattend lijkt de veiligheid van medicatie voor het (ongeboren) kind een belangrijk gegeven voor zwangeren in de besluitvorming rondom het gebruik van psychotrope medicatie tijdens de zwangerschap. Hiernaast speelt subjectief welbevinden en stigma een rol. Ten slotte is er een toename van activiteit op sociale media na publicaties van studies ten aanzien van risico en stopt een deel van de vrouwen met antipsychotica wanneer er een zwangerschap tot stand gekomen is.

Waardevolle informatie over het gebruik van geneesmiddelen rondom de zwangerschap wordt verzameld door middel van patiëntenvragenlijsten via https://www.pregnant.nl/ en https://www.moedersvanmorgen.nl/.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De kosten van de verschillende antipsychotica liggen dusdanig dicht bij elkaar dat de kosten per middel geen rol van betekenis spelen bij de medicatie keuze. Het staken van de antipsychotica tijdens de zwangerschap kan in sommige situaties leiden tot ernstige ontsporing, met mogelijk klinische opname en zorgmijding met alle kosten van dien. Daarnaast kan daaruit voortvloeiende ernstige stress en verminderde capaciteit tot adequate interactie met het kind de ontwikkeling van het kind in de cruciale periode van de eerste 1000 dagen ongunstig beïnvloeden met verhoogde kans op ontwikkelings-, gedrags-, en emotionele problemen later in het leven, hetgeen zal leiden tot middelenbeslag. Ook kan de noodzaak tot het tijdelijk of langdurig overnemen van de zorg voor het kind door derden leiden tot een aanzienlijk middelenbeslag.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie.

De werkgroep vindt antipsychotica gebruik tijdens zwangerschap met betrekking tot het risico op aangeboren afwijkingen een aanvaardbare interventie mits er een juiste indicatie is en er een goede afweging is gemaakt ten aanzien van eventuele alternatieve behandelstrategieën.

Door implementatie van netwerkzorg voor zwangere vrouwen met antipsychotica gebruik, zoals bijvoorbeeld een multidisciplinaire POP-poli/ team, zullen alle betrokkenen (huisarts, verloskundig zorgverlener, GGZ zorgverlener (psychiater, psycholoog, verpleegkundig specialist, sociaal-psychiatrisch verpleegkundige (SPV), physician assistant (PA)), kraamverzorgster, maatschappelijke werker, medewerkers van jeugdgezondheidszorg (CB/CJG) en kinderarts) tijdig geïnformeerd zijn over de afwegingen voor de individuele zwangere om een antipsychoticum wel of niet te continueren. In het geval van mogelijke aangeboren afwijkingen is een pre-conceptioneel advies bij uitstek van belang gezien de foetale ontwikkeling in het eerste trimester.

Maatschappelijk bestaat er een inzicht in en groeiend draagvlak voor het belang van geïntegreerde zorg voor moeder en kind gedurende de eerste 1000 dagen van de ontwikkeling, zoals ook tot uitdrukking komt in het landelijke programma ‘kansrijke start’ van de Ministerie van Volksgezondheid.

Rationale/ balans tussen de argumenten voor en tegen de interventie

Op basis van de momenteel voor handen zijnde gegevens ten aanzien van het risico op congenitale afwijkingen geldt dat het relatief onbekende risico op congenitale afwijkingen afgewogen moet worden tegen de noodzaak van het gebruik tijdens de zwangerschap. Zoals hierboven is genoteerd zijn er tot op heden geen aanwijzingen voor ernstige aangeboren afwijkingen bij gebruik van antipsychotica. Daarbij moet in acht worden genomen dat er ook gekeken moet worden naar een maximale inzet van niet-medicamenteuze interventies en de voorkeuren van de (toekomstige) zwangere. Ten alle tijden dient gestreefd te worden naar een zo laag mogelijke dosering met een voldoende veilig maar ook doelmatig/ effectief antipsychoticum.

Vanuit de voor deze uitgangsvraag gebruikte literatuurstudie is er een lichte voorkeur voor de groep van typische antipsychotica, met name haloperidol. Binnen de groep atypische antipsychotica hebben olanzapine en quetiapine ten aanzien van mogelijke congenitale afwijkingen in lichte mate de voorkeur.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Antipsychotica zijn over het algemeen effectief in de behandeling en preventie van psychotische stoornissen. Stabiliteit is van belang voor zowel de zwangere als het (ongeboren) kind. Antipsychotica bereiken, middels transplacentaire passage, ook het (ongeboren) kind. Vanuit de praktijk is de ervaring dat de impact op het kind een belangrijke overweging is voor zwangeren in het starten of continueren van antipsychotica. Voor een goede afweging en shared decision-making is adequate informatie over de impact op de ontwikkeling van het kind van groot belang. Antipsychotica worden in de wetenschappelijke literatuur meestal ingedeeld in typische en atypische antipsychotica.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of antipsychotics on the risk of major congenital malformations in children of women taking antipsychotics during pregnancy, compared to children of women not taking antipsychotics.

Bronnen: (Vigod, 2015; Petersen, 2016; Reis, 2008; Habermann, 2013; Huybrechts, 2016; McKenna, 2005; Sadowski, 2013; Diav-Citrin 2005; Bellet 2015; Cohen 2018) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of antipsychotics on the risk of congenital cardiac malformations in children of women taking antipsychotics during pregnancy, compared to women not taking antipsychotics.

Bronnen: (Reis, 2008; Habermann, 2013; Huybrechts, 2016) |

|

- GRADE |

No conclusions could be drawn about the effect of antipsychotic use during pregnancy on the risk of congenital malformations of the central nervous system, compared with non-exposure to antipsychotics, because of the absence of relevant comparative studies. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

The study population varied from 86 to 9991 women exposed to antipsychotics during pregnancy. The number of exposed pregnancies is shown per study in Table 1. In total, there were 13375 exposed pregnancies and 13400 exposed infants.

Table 1 Number of exposed pregnancies and infants per study

|

Study reference |

Number of exposed pregnancies |

Number of exposed infants |

|

Bellet, 2015 |

86 (85 singleton and 1 twin pregnancy) |

87 |

|

Cohen, 2018 |

152 (149 singleton and 3 twin pregnancies) |

155 |

|

Huybrechts, 2016 |

singleton or twin pregnancies: NA 9258 exposed to atypical AP 733 exposed to typical AP |

assuming singleton pregnancies: 9258 (atypical AP) 733 (typical AP) |

|

Vigod, 2015 |

1021 singleton pregnancies |

1021 |

|

Diav-Citrin, 2005 |

176 (173 singleton and 3 twin pregnancies) |

179 |

|

Habermann, 2013 |

4471 exposed to atypical AP (441 singleton and 6 twin pregnancies) 2331 exposed to typical AP (228 singleton and 5 twin pregnancies) |

453 (atypical AP) 238 (typical AP) |

|

McKenna, 2005 |

singleton or twin pregnancies: NA 151 pregnancies (exposed to atypical AP) |

assuming singleton pregnancies: 151 (of which 110 live births; atypical AP) |

|

Sadowski, 2013 |

133 singleton pregnancies (atypical AP) |

133 (atypical AP) |

|

Petersen, 2016 |

singleton or twin pregnancies: NA 416 pregnancies |

assuming singleton pregnancies: 416 |

|

Reis, 2008 |

570 (564 singleton and 6 twin pregnancies) |

576 |

|

Total |

13375 |

13400 |

1 Only pregnancies resulting in livebirths. AP, antipsychotics

In all studies, except Cohen (2018), the comparison groups consisted of women without a known history of psychiatric disorders or not filling prescriptions for antipsychotics during pregnancy (Bellet, 2015; Huybrechts, 2016; Vigod, 2015; Diav-Citrin, 2005; Habermann, 2013; McKenna, 2005; Reis, 2008; Petersen, 2013; Sadowski, 2013). However, 2 studies also included a second comparison group of women that received prescriptions for antipsychotics before pregnancy or had been diagnosed with psychiatric disorders (Petersen, 2016; Vigod, 2015). The proportions of patients with various psychiatric disorders differed between the exposed and unexposed groups. Cohen (2018) compared women taking atypical antipsychotics (second generation antipsychotics, SGA) with women with psychiatric disorders who discontinued atypical antipsychotics before pregnancy (and used other psychotropic drugs, including SSRI’s, anticonvulsants and anxiolytics). Petersen (2016) included a control group of women with psychiatric disorders who discontinued antipsychotics before the start of pregnancy. Vigod (2015) described a mixed comparison group of patients with and without psychiatric disorders, and a second control group, which consisted of women with psychiatric disorders not using antipsychotics matched with antipsychotic users on age and propensity scores (Vigod, 2015). One study performed a subgroup analysis to compare the risk of major congenital malformations in children of women taking typical (first generation antipsychotics, FGA) and atypical antipsychotics (Habermann, 2013).

In 9 studies, major congenital malformations were investigated after exposure to antipsychotics during the 1st and/or 2nd trimester of pregnancy (Bellet, 2015; Cohen, 2018; Huybrechts, 2016; Vigod, 2015; Diav-Citrin, 2005; Habermann, 2013; McKenna, 2005; Reis, 2008; Petersen, 2013). In 7 studies this information was available at baseline (Bellet, 2015, Cohen, 2018; Huybrechts, 2016; Vigod, 2015; McKenna, 2005; Petersen, 2016; Reis, 2008), and in 2 studies it was taken into account in sensitivity analyses (Diav-Citrin, 2005; Habermann, 2013).

The duration of follow-up across the studies varied between 1 month and the first 1 to 2 (maximum 6) years after birth.

The outcome ‘major congenital malformations’ included any congenital abnormalities in any organ system (the central nervous system, ear and eye, abnormalities of the cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, genital, urinary, and musculoskeletal systems and limb defects). Three studies specifically investigated the risk of cardiac malformations (Huybrechts, 2016; Reis, 2008; Habermann, 2013). No specific pattern of major congenital malformations was found after intrauterine exposure to antipsychotics in any of the studies.

Results

The results are presented by outcome measure for different comparisons: all antipsychotics (typical and atypical) as a group versus no antipsychotics, typical antipsychotics (as a group) versus no antipsychotics, atypical antipsychotics (as a group) versus no antipsychotics and individual antipsychotics versus no antipsychotics.

Major congenital malformations (critical outcome)

All antipsychotics as a group versus no antipsychotics

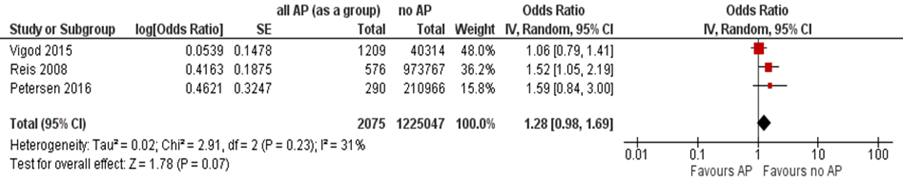

Three studies described the risk of major congenital malformations after intrauterine exposure to antipsychotics (as a group), compared with no use of antipsychotics (Vigod, 2015; Petersen, 2016; Reis, 2008; Table 2). The results across the included studies are summarized in Figure 1 (a,b).

Vigod (2015) investigated the risk of major congenital malformations using two control groups of unexposed women. The first control group consisted of 40314 women without antipsychotic exposure during pregnancy, but some of them had a history of psychiatric disorders (psychotic disorder 1.7%, bipolar disorder or major depression 21.6%, personality disorder 4.5%) (Vigod, 2015). This group was compared with 1209 women taking antipsychotics during pregnancy (psychotic disorder 35.5%, bipolar disorder or major depression 77.5%, personality disorder 32.5%). The second control group consisted of women with psychiatric disorders and was matched with the cases in 1:1 ratio using propensity scores and the maternal age at delivery (n=1021). In the matched exposed group, 834 of 1021 patients (approximately 82%) were prescribed atypical antipsychotics as monotherapy: 556 quetiapine, 166 olanzapine, and 112 risperidone (Vigod, 2015). The type of antipsychotics used by the other 187 patients is not clearly reported in the paper (Vigod, 2015).

The crude relative risk (RR) for major congenital malformations in the unmatched group was 1.05 (95% CI 0.79 to 1.41). In the matched cohort, the relative risk (RR) of major congenital malformations was 1.19 (95% CI 0.75 to 1.91), after the adjustment for the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI’s), non-SSRI’s, mood stabilizers and benzodiazepines (Vigod, 2015).

Table 2 Studies reporting on the risk of major congenital malformations (all antipsychotics as a group versus no antipsychotic exposure)

|

Reference |

Source population |

Exposed |

Unexposed |

|

Registry-based cohort study (prescription database and electronic medical records) |

at least 1 prescription for antipsychotics in the 1st or 2nd trimester of pregnancy and ≥2 consecutive prescriptions during pregnancy |

no prescriptions for antipsychotics during pregnancy |

|

|

Petersen 2016 |

Registry-based cohort study (prescription database and electronic medical records) |

prescriptions for antipsychotics during the 1st trimester of pregnancy

|

1. no prescriptions for antipsychotics 2 years before pregnancy and during pregnancy (until the delivery date) 2. prescriptions for antipsychotics 2 years before pregnancy but not during pregnancy (discontinued 4 weeks before pregnancy) |

|

Reis 2008 |

Registry-based cohort study (national birth register, national malformations register, prescription database and electronic medical records) |

prescriptions for antipsychotics during the 1st trimester of pregnancy

|

all other women in the birth registry database |

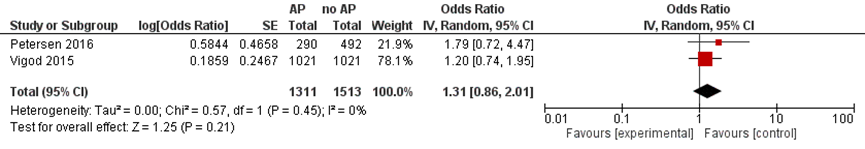

In the study by Petersen (2016), the adjusted RR for major congenital malformations was 1.59 (95% CI 0.84 to 3.00) in children of women receiving prescriptions for antipsychotics in the 1st trimester of pregnancy (n=290), compared with women with no prescriptions 2 years before pregnancy and through the delivery date (n=210966). When compared to women that discontinued antipsychotics 4 weeks before the start of pregnancy (n=492), the adjusted RR for major congenital malformations was 1.79 (95% CI 0.72 to 4.47) (Petersen, 2016).

Figure 1a Major congenital malformations after exposure to any antipsychotics (as a group) during pregnancy, when compared to a general control group (adjusted OR)

Note: Women taking anticonvulsants in the study by Reis (2008) were not excluded. AP, antipsychotics

In a Swedish population-based registry study of women taking antipsychotics in the 1st trimester of pregnancy compared to the rest of the women in the database, OR for any congenital malformations (including minor malformations) was 1.31 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.86) (Reis, 2008).

Figure 1b Major congenital malformations after exposure to any antipsychotics (as a group) during pregnancy, when compared to women with psychiatric disease

Note: The comparison group consised of women with psychiatric disorders in the study by Vigod (2015), and in the study of Petersen (2016) it consisted of women who filled prescriptions for antipsychotics before pregnancy but discontinued antipsychotic use during pregnancy. AP, antipsychotics

The OR for major congenital malformations (defined in the study as “relatively severe malformations” after excluding minor malformations) was nominally statistically significant (OR 1.52 (95% CI 1.05 to 2.19)), after adjusting for year of birth, maternal age, parity, smoking, and previous miscarriages (Reis, 2008). After excluding women who concomitantly took anticonvulsants (due to known teratogenic potential of these drugs), the OR was not statistically significant: 1.45 (95% CI 0.99 to 1.41), p=0.055 (Reis, 2008).

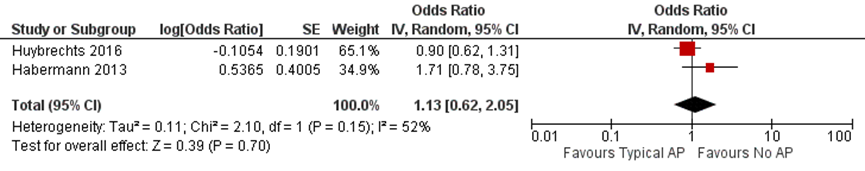

Typical antipsychotics (as a group) versus no antipsychotics

Two studies compared the risk of congenital malformations after intrauterine exposure to typical antipsychotics (Habermann, 2013; Huybrechts, 2016; Table 3).

The absolute risk of major congenital malformations was 38.2 (95% CI 26.6 to 54.7) per 1000 births exposed to typical antipsychotics, compared with 32.7 (95% CI 32.4 to 33.0) per 1000 births not exposed to antipsychotics (Huybrechts, 2016). After adjustment for confounders, the relative risk of major congenital malformations for typical antipsychotics, compared with no use of antipsychotics, was 0.90 (95% CI 0.62 to 1.31) (Huybrechts, 2016; Figure 4).

In the study by Habermann (2013) the adjusted OR for major congenital malformations after exposure to typical antipsychotics during pregnancy was 1.71 (95% CI 0.78 to 3.76) (Habermann, 2013).

Table 3 Studies reporting on the risk of major congenital malformations (typical antipsychotics as a group versus no antipsychotic exposure)

|

Reference |

Source population |

Exposed |

Unexposed |

|

Habermann 2013 |

Cohort study within a TIS database

|

Pregnant women who consulted TIS and used typical antipsychotics |

Pregnant women who consulted TIS and did not use antipsychotics (other drugs known to be nonteratogenic were allowed in this group) |

|

Huybrechts 2015

|

Registry-based cohort study (Medicaid insurance database) |

filling at least 1 prescription for antipsychotics during the first 90 days of pregnancy |

not filling a prescription for antipsychotics during 3 months before the start of pregnancy or during the 1st trimester |

The pooled results of studies investigating the risk of major congenital malformations after exposure to typical antipsychotics are shown in Figure 2. The results demonstrate no statistically significant increase in the risk of major congenital malformations after exposure to typical antipsychotics in the 1st trimester of pregnancy (OR 1.13 (95% CI 0.62 to 2.05)).

Figure 2 Odds ratio for major congenital malformations, according to maternal exposure to typical antipsychotics

AP, antipsychotics.

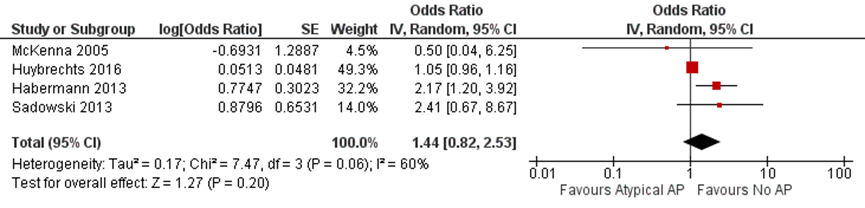

Atypical antipsychotics (as a group) versus no antipsychotics

Four studies assessed the risk of major congenital malformations after exposure to atypical antipsychotics (as a group) versus non-exposure (Habermann, 2013; Huybrechts, 2016; McKenna, 2005; Sadowski, 2013; Table 4). Three studies found no increase in risk and 1 study (Habermann, 2013) found an increased risk for major congenital malformations.

Table 4 Studies reporting on the risk of major congenital malformations (atypical antipsychotics as a group versus no antipsychotic exposure)

|

reference |

source population |

exposed |

unexposed |

|

Habermann 2013 |

Cohort study within a TIS database

|

Pregnant women who consulted TIS and used atypical antipsychotics |

Pregnant women who consulted TIS and did not use antipsychotics (other drugs known to be nonteratogenic were allowed in this group) |

|

Huybrechts 2015

|

Registry-based cohort study (Medicaid insurance database) |

Pregnant women filling at least 1 prescription for atypical antipsychotics during the first 90 days of pregnancy |

Pregnant women not filling a prescription for antipsychotics during 3 months before the start of pregnancy or during the 1st trimester |

|

McKenna 2005 |

Cohort study within a TIS database (multicenter, Motherisk and other TIS)

|

Pregnant women who consulted TIS and took atypical antipsychotics during the 1st trimester of pregnancy |

Pregnant women who consulted TIS and did not use antipsychotics (other drugs known to be nonteratogenic, including psychotropic drugs, were allowed in this group) |

|

Sadowski 2013 |

Cohort study within a TIS database (Motherisk)

|

Pregnant women who consulted TIS about the safety of atypical antipsychotics and confirmed the use of these medications for a minimum of 4 weeks of pregnancy |

Pregnant women who consulted TIS and did not use antipsychotics (other drugs known to be nonteratogenic were allowed in this group) |

The absolute risk of major congenital malformations was 44.5 (95% CI 40.5 to 48.9) per 1000 births exposed to atypical antipsychotics, compared with 32.7 (95% CI 32.4 to 33.0) per 1000 births not exposed to AP (Huybrechts, 2016). After adjustment for confounders, the relative risk of major congenital malformations for atypical antipsychotics (as a group) was 1.05 (95% CI 0.96 to 1.16), compared with no use of antipsychotics (Huybrechts 2016; Figure 4).

McKenna (2005) compared the use of atypical antipsychotics in the 1st trimester with no use of antipsychotics during pregnancy in 151 exposed and 151 unexposed women matched on maternal and gestational age. The rate of major congenital malformations was 0.9% (n=1) and 1.5% (n=2), respectively (OR 0.5 (95% CI 0.04 to 5.54); McKenna, 2005).

Sadowski (2013) reported no statistically significant increase in the rate of major congenital malformations after exposure to atypical antipsychotics for a minimum of 4 weeks of pregnancy (6.2% in exposed versus 2.6% in unexposed, OR 2.41 (95% CI 0.67 to 9.52)).

Habermann (2013) reported an increased risk of major congenital malformations after the 1st trimester exposure to atypical antipsychotics (adjusted OR 2.17 (95% CI 1.20 to 3.91), adjustment for alcohol consumption > 1 drinks a day).

The pooled results of studies investigating the risk of major congenital malformations after exposure to atypical antipsychotics are shown in Figure 3. The results demonstrate no statistically significant increase in the risk of major congenital malformations after exposure to atypical antipsychotics during pregnancy (OR 1.44 (95% CI 0.82 to 2.53)).

Figure 3 Odds ratio for major congenital malformations, according to maternal exposure to atypical AP, compared to no exposure (in women without a history of psychiatric illness)

AP, antipsychotics.

Habermann (2013) also assessed the risk of major congenital malformations between women exposed only to typical antipsychotics and women exposed to atypical antipsychotics (with a small percentage of concomitant typical antipsychotics), and found no statistically significant differences (adjusted OR 1.27 (95% CI 0.57 to 2.82); Habermann, 2013).

Individual antipsychotics versus no antipsychotics

• Typical antipsychotics

Only one study reported on the risk of major congenital malformations after exposure to haloperidol and penfluridol during pregnancy (Diav-Citrin, 2005). The prevalence of congenital malformations was not statistically significantly different between exposed and unexposed (3.4% versus 3.8%, crude OR 0.89 (95% CI 0.35 to 2.22) (Diav-Citrin, 2005). In the analysis restricted to the 1st trimester exposure, the prevalence of congenital malformations in live births was also not statistically significantly different, 3.1% (4/128) in the exposed group and 3.8% (22/581) in the unexposed group (crude OR 0.82 (95% CI 0.28 to 2.44); Diav-Citrin, 2005).

• Atypical antipsychotics

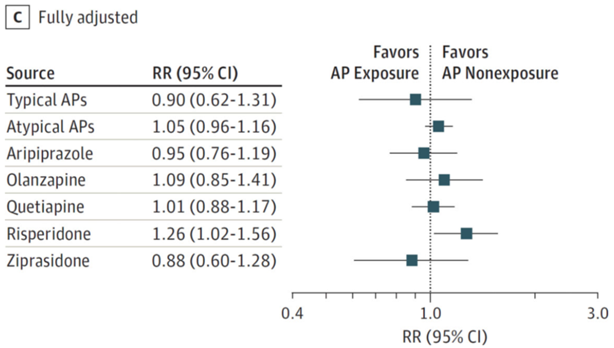

There were 3 studies investigating aripiprazole (Bellet, 2015; Huybrechts, 2016; Habermann, 2013) and 3 studies assessing quetiapine exposure (Cohen, 2018; Huybrechts, 2016; Habermann, 2013). Olanzapine, ziprasidone and risperidone as individual drugs were described in 1 study (Huybrechts, 2016). The results for individual drugs from Huybrechts (2016) are presented in Figure 4.

In the study by Bellet (2015) the number of major congenital malformations was equal in the aripiprazole exposed (n=2 of 71) and unexposed groups (n=2 of 161; crude OR 2.30 (95% CI 0.32 to 16.7)). In the study by Habermann (2013) the rate of major congenital malformations after the 1st trimester exposure to aripiprazole was 6.81% (3/44). Huybrechts (2016) found no increase in the relative risk of major congenital malformations in pregnancies exposed to aripiprazole versus unexposed pregnancies (RR 0.95 (95% CI 0.76 to 1.19)).

Figure 4 Relative risk (RR) for major congenital malformations in infants according to maternal exposure to antipsychotics (APs)

C, adjusted for all measured covariates on the study (Huybrechts, 2016)

Cohen (2018) found no increase in the risk of major congenital malformations in women who took quetiapine in the 1st trimester of pregnancy (crude OR 0.90 (95% CI 0.15 to 5.46)), compared to women with psychiatric disorders not using atypical antipsychotics. Habermann (2013) found major congenital malformations in 3.59% (5/139) of women exposed to quetiapine in the 1st trimester of pregnancy (the percentage was not statistically significantly different from other atypical antipsychotics). In Huybrechts (2016) the adjusted relative risk of major congenital malformations after exposure to quetiapine was 1.01 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.17) (Figure 4).

The adjusted relative risks for major congenital malformations in pregnancies exposed to olanzapine (RR 1.09 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.41) and ziprasidone (RR 0.88 (95% CI 0.60 to 1.28)) were not statistically significant when compared with no exposure to AP during pregnancy (Huybrechts, 2016; Figure 4).

There was a mild increase in risk for risperidone, which was nominally statistically significant (RR 1.26 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.56); Huybrechts, 2016; Figure 4).

Congenital cardiac malformations (important outcome)

There were three studies assessing the risk of congenital cardiac malformations after exposure to antipsychotics during pregnancy (Reis, 2008; Huybrechts, 2016; Habermann, 2013). Two studies reported no increase in the risk of congenital cardiac malformations after exposure to typical antipsychotics (Huybrechts, 2016; Habermann, 2013). One study (Habermann, 2013) found an increased risk of cardiac malformations after exposure to atypical antipsychotics (SGA), while another study (Huybrechts, 2016) did not.

All antipsychotics as a group versus no antipsychotics

Reis (2008) found no increase in the risk of congenital cardiac malformations in women receiving antipsychotics in the 1st trimester of pregnancy, compared with unexposed women (RR 1.43 (95% CI 0.69 to 2.63)).

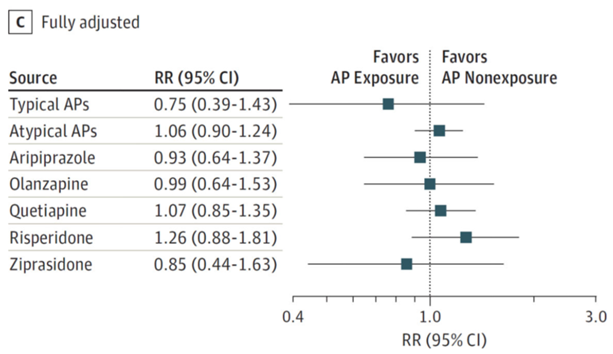

Typical antipsychotics (as a group) versus no antipsychotics

The absolute risk of congenital cardiac malformations was 13.6 (95% CI 7.4 to 24.9) per 1000 births exposed to typical antipsychotics, compared with 11.6 (95% CI 11.4 to 11.7) per 1000 births in infants not exposed to antipsychotics (Huybrechts, 2016). The adjusted RR for congenital cardiac malformations for typical antipsychotics in the study by Huybrechts (2016) was 0.75 (95% CI 0.39 to 1.43) (Huybrechts, 2016; Figure 5).

Figure 5 Relative risk for congenital cardiac malformations in infants according to maternal exposure to antipsychotics

C, adjusted for all measured covariates on the study (Huybrechts, 2016)

Habermann (2013) also found no increase in the risk of congenital cardiac malformations after exposure to typical antipsychotics, compared to non-exposure (OR 2.13 (95% CI 0.65 to 7.01)), and when comparing users of typical and atypical antipsychotics with each other (OR 1.50 (95% CI 0.48 to 4.71)).

Atypical antipsychotics (as a group) versus no antipsychotics

The absolute risk of congenital cardiac malformations was 16.2 (95% CI 13.8 to 19.0) per 1000 births exposed to atypical antipsychotics, compared with 11.6 (95% CI 11.4 to 11.7) per 1000 births in infants not exposed to antipsychotics (Huybrechts 2016). The adjusted RR for congenital cardiac malformations for atypical antipsychotics (as a group) in the study by Huybrechts (2016) was 1.06 (95% CI 0.90 to 1.24) (Figure 5). However, Habermann (2013) found an increased risk for congenital cardiac malformations after exposure to atypical antipsychotics compared to non-exposure (crude OR 3.21 (95% CI 1.34 to 7.67)).

Individual AP versus no AP

The adjusted relative risks for congenital cardiac malformations in pregnancies exposed to aripiprazole (RR 0.93 (95% CI 0.64 to 1.37), olanzapine (RR 0.99 (95% CI 0.64 to 1.53)), quetiapine (RR 1.07 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.35)), risperidone (RR 1.26 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.81)) and ziprasidone (RR 0.85 (95% CI 0.44 to 1.63) were not statistically significant, when compared to non-exposed pregnancies (Huybrechts 2016, Figure 5).

Congenital malformations of the central nervous system (important outcome)

There was no literature specifically examining the risk of congenital brain malformations after exposure to antipsychotics during gestation.

Level of evidence of the literature

Due to data extraction from prescription databases and TIS registers there is a possibility of misclassification of the exposure. The effect of underlying psychiatric disorders on the outcomes could not be taken into account in the studies that used a control group of women without psychiatric disorders. There was no evidence regarding the outcome ‘congenital brain malformations’.

The quality of evidence for the outcome measures ‘major congenital malformations’ and ‘congenital cardiac malformations’ was downgraded by three levels, because of serious study limitations (risk of bias due to patient selection and confounding), inconsistency (conflicting results) and indirectness (healthy control group taking nonteratogenic medications recruited through teratology information services, combining different drugs in one group). We have very little confidence in the effect estimates: the true effect of antipsychotic use during pregnancy on the risk of major congenital malformations and congenital cardiac malformations is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effect of antipsychotic use during pregnancy on the risk of congenital malformations in children of women with psychiatric disorders, compared to pregnant women not taking antipsychotics?

P: patients: pregnant women with psychiatric disorders;

I: intervention: antipsychotic use during (the 1st trimester of) pregnancy;

C: control: no antipsychotic use or use of a different antipsychotic drug (comparison between different antipsychotics);

O: outcome: congenital malformations.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered the risk of major congenital malformations after in utero exposure to antipsychotics as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and the risk of congenital malformations in specific organ systems (cardiovascular and central nervous system) as important outcome measures for decision making.

The guideline working group did not define the minimal (clinically) important difference for the outcome ‘congenital malformations’.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from the 1st of January 1960 until the 25th of March 2019. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 275 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews (with meta-analyses) and comparative observational (case-control and cohort) studies, investigating the risk of major congenital malformations in children of women with psychiatric disorders taking antipsychotics during pregnancy, compared with healthy women, and women with psychiatric disorders not taking antipsychotics or taking a different antipsychotic. Thirty-four studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 24 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and 10 studies were included.

Results

Ten observational comparative studies were included in the analysis of literature. All studies had a prospective cohort design. In 5 studies participants were recruited via teratology information services (Bellet, 2015; Diav-Citrin, 2005; Habermann, 2013; McKenna, 2005; Sadowski, 2013), the other 5 studies used information from population-based birth registers and databases of electronic medical records, prescriptions data and insurance records (Cohen, 2018; Huybrechts, 2016; Vigod, 2015; Petersen, 2016; Reis, 2008). Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) (2008). Use of psychiatric medications during pregnancy and lactation Clinical Practice Guidelines. Retrieved from https://www.guidelinecentral.com/summaries/use-of-psychiatric-medications-during-pregnancy-and-lactation/#section-society.

- Bellet, F., Beyens, M. N., Bernard, N., Beghin, D., Elefant, E., & Vial, T. (2015). Exposure to aripiprazole during embryogenesis: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety, 24(4), 368-380.

- Cohen, L. S., Góez-Mogollón, L., Sosinsky, A. Z., Savella, G. M., Viguera, A. C., Chitayat, D.,... & Freeman, M. P. (2018). Risk of major malformations in infants following first-trimester exposure to quetiapine. American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(12), 1225-1231.

- Courtet, P. (2001). Viewpoint of schizophrenic patients: a European survey. L'Encephale, 27(1), 28-38.

- Diav-Citrin, O., Shechtman, S., Ornoy, S., Arnon, J., Schaefer, C., Garbis, H.,... & Ornoy, A. (2005). Safety of haloperidol and penfluridol in pregnancy: a multicenter, prospective, controlled study. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 66(3), 317-322.

- Gentile, S. (2010). Antipsychotic therapy during early and late pregnancy. A systematic review. Schizophrenia bulletin, 36(3), 518-544.

- Habermann, F., Fritzsche, J., Fuhlbrück, F., Wacker, E., Allignol, A., Weber-Schoendorfer, C.,... & Schaefer, C. (2013). Atypical antipsychotic drugs and pregnancy outcome: a prospective, cohort study. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology, 33(4), 453-462.

- Hippman, C., & Balneaves, L. G. (2018). Women's decision making about antidepressant use during pregnancy: A narrative review. Depression and anxiety, 35(12), 1158-1167.

- Huybrechts, K. F., Hernández-Díaz, S., Patorno, E., Desai, R. J., Mogun, H., Dejene, S. Z.,... & Bateman, B. T. (2016). Antipsychotic use in pregnancy and the risk for congenital malformations. JAMA psychiatry, 73(9), 938-946.

- Kothari, A., de Laat, J., Dulhunty, J. M., & Bruxner, G. (2019). Perceptions of pregnant women regarding antidepressant and anxiolytic medication use during pregnancy. Australasian Psychiatry, 27(2), 117-120.

- LAREB. (2020) Klassieke antipsychotica tijdens de zwangerschap. Retrieved from https://www.lareb.nl/tis-knowledge-screen?id=33&page=1&searchArray=antipsychotica&pregnancy=true&breastfeeding=true&name=Klassieke%20antipsychotica%20tijdens%20de%20zwangerschap.

- Leidraad indicatiestelling prenatale diagnostiek https://www.nvog.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/definitief-NVOG-Leidraad-indicatiestelling-PND-versie-feb.-2019.pdf

- McAllister-Williams, R. H., Baldwin, D. S., Cantwell, R., Easter, A., Gilvarry, E., Glover, V.,... & Khalifeh, H. (2017). British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus guidance on the use of psychotropic medication preconception, in pregnancy and postpartum 2017. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 31(5), 519-552.

- McKenna, K., Koren, G., Tetelbaum, M., Wilton, L., Shakir, S., Diav-Citrin, O.,... & Einarson, A. (2005). Pregnancy outcome of women using atypical antipsychotic drugs: a prospective comparative study. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 66(4), 444-9.

- Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport (2018). Richtlijn ‘Bijwerkingen antipsychotica bij schizofrenie’. Retrieved from https://kansrijkestart.nl/.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2014) Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance (NICE Clinical guideline CG192). Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg192.

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie. (2012) Richtlijn Schizofrenie. Retrieved from https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/schizofrenie/schizofrenie_-_startpagina.html#tab-content-general.

- Nygaard, L., Rossen, C. B., & Buus, N. (2015). Balancing risk: a grounded theory study of pregnant women's decisions to (dis) continue antidepressant therapy. Issues in mental health nursing, 36(7), 485-492.

- Park, Y., Huybrechts, K. F., Cohen, J. M., Bateman, B. T., Desai, R. J., Patorno, E.,... & Hernandez-Diaz, S. (2017). Antipsychotic medication use among publicly insured pregnant women in the United States. Psychiatric services, 68(11), 1112-1119.

- Petersen, I., Sammon, C. J., McCrea, R. L., Osborn, D. P., Evans, S. J., Cowen, P. J., & Nazareth, I. (2016). Risks associated with antipsychotic treatment in pregnancy: comparative cohort studies based on electronic health records. Schizophrenia research, 176(2-3), 349-356.

- Reis, M., & Källén, B. (2008). Maternal use of antipsychotics in early pregnancy and delivery outcome. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology, 28(3), 279-288.

- Sadowski A, Todorow M, Yazdani Brojeni P, Koren G, Nulman I. Pregnancy outcomes following maternal exposure to second-generation antipsychotics given with other psychotropic drugs: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013 Jul 13;3(7).

- Schoretsanitis, G., Westin, A. A., Deligiannidis, K. M., Spigset, O., & Paulzen, M. (2019). Excretion of antipsychotics into the amniotic fluid, umbilical cord blood, and breast milk: A systematic critical review and combined analysis. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring.

- Singh, K. P., Singh, M. K., & Singh, M. (2016). Effects of prenatal exposure to antipsychotic risperidone on developmental neurotoxicity, apoptotic neurodegeneration and neurobehavioral sequelae in rat offspring. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience, 52, 13-23.

- van Gelder, M. M., Rog, A., Bredie, S. J., Kievit, W., Nordeng, H., & van de Belt, T. H. (2019). Social media monitoring on the perceived safety of medication use during pregnancy: A case study from the Netherlands. British journal of clinical pharmacology, 85(11), 2580-2590.

- Vigod, S. N., Bagheri, E., Zarrinkalam, F., Brown, H. K., Mamdani, M., & Ray, J. G. (2018). Online social network response to studies on antidepressant use in pregnancy. Journal of psychosomatic research, 106, 70-72.

- Vigod, S. N., Gomes, T., Wilton, A. S., Taylor, V. H., & Ray, J. G. (2015). Antipsychotic drug use in pregnancy: high dimensional, propensity matched, population based cohort study. bmj, 350, h2298.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence tables for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, case series))

Research question: What is the effect of antipsychotic use during pregnancy on the risk of congenital malformations in children of women with psychiatric disorders, compared to children of women not taking antipsychotics during pregnancy?

Haberman (2013): maternal age, alcohol consumption, smoking habits, BMI), previous spontaneous abortions, and previous malformed children were included in a start model for adjustment through logistic regression to define the relevant confounders for major malformations, but only alcohol > 1 drink/day had a significant influence and was considered in the final analysis.

ADD, antidepressant drugs. BMI, body mass index. FGA-first generation antipsychotics. SGA-second generation antipsychotics. SSRI-selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. SNRI-serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (observational: non-randomized clinical trials, cohort and case-control studies)

Research question: What is the effect of antipsychotic use during pregnancy on the risk of congenital malformations in children of women with psychiatric disorders, compared to children of women not taking antipsychotics during pregnancy?

|

Study reference

(first author, year of publication) |

Bias due to a non-representative or ill-defined sample of patients?1

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to insufficiently long, or incomplete follow-up, or differences in follow-up between treatment groups?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to ill-defined or inadequately measured outcome ?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate adjustment for all important prognostic factors?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Bellet, 2015 |

likely |

unlikely |

likely |

likely |

|

Cohen, 2018 |

likely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

likely |

|

Diav-Citrin, 2005 |

likely |

likely |

unlikely |

likely |

|

Habermann, 2013 |

likely |

likely |

unlikely |

likely |

|

Huybrechts, 2016 |

likely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

|

Reis, 2008 |

likely |

likely |

unlikely |

likely |

|

McKenna, 2005 |

likely |

likely |

unlikely |

likely |

|

Petersen, 2016 |

likely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

|

Sadowski, 2013 |

likely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

likely |

|

Vigod, 2015 |

likely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

- Failure to develop and apply appropriate eligibility criteria: a) case-control study: under- or over-matching in case-control studies; b) cohort study: selection of exposed and unexposed from different populations.

- Bias is likely if: the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large; or differs between treatment groups; or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups; or length of follow-up differs between treatment groups or is too short. The risk of bias is unclear if: the number of patients lost to follow-up; or the reasons why, are not reported.

- Flawed measurement, or differences in measurement of outcome in treatment and control group; bias may also result from a lack of blinding of those assessing outcomes (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Failure to adequately measure all known prognostic factors and/or failure to adequately adjust for these factors in multivariate statistical analysis.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Altshuler, 1996 |

narrative review |

|

Cohen, 2016 |

big overlap with the study population used in Cohen, 2018 |

|

Coppola, 2007 |

descriptive non-comparative study |

|

Coughlin, 2015 |

systematic review and meta-analysis, used results from a book, pooled studies extremely heterogenous |

|

Cuomo, 2018 |

narrative review |

|

Ennis, 2015 |

systematic review without a meta-analysis |

|

Gentile, 2004 |

comprehensive literature review, does not comply with the PRISMA checklist for systematic reviews |

|

Gentile, 2010 |

does not comply with the PRISMA checklist; no meta-analysis |

|

Gentile, 2014 |

narrative review |

|

Gentile, 2010 |

narrative review |

|

Hatters, 2016 |

retrospective non-comparative study |

|

Kallen 2013 |

narrative review and analysis of database, big overlap with the study population used in Reis 2008 |

|

Khalifeh, 2015 |

editorial |

|

Kuller, 1996 |

narrative review |

|

McCauley-Elsom, 2010 |

case report |

|

Mehta, 2017 |

narrative review |

|

Newham, 2008 |

Outcome does not fit the PICO |

|

Nulman, 2014 |

narrative review, no full text |

|

Oyebode, 2012 |

narrative review |

|

Patton, 2002 |

narrative review |

|

Petersen, 2016 |

used the same population as Petersen, Sammon et al. 2016 |

|

Terrana, 2015 |

meta-analysis used a conference abstract, no full text of meta-analyzed studies |

|

Tosato, 2017 |

narrative review |

|

Wichman, 2009 |

retrospective review |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 14-10-2021

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 23-07-2021

Bij het opstellen van de modules heeft de werkgroep een inschatting gemaakt over de maximale termijn waarop herbeoordeling moet plaatsvinden. De geldigheid van de richtlijnmodules komt eerder te vervallen indien nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding zijn een herzieningstraject te starten.

|

Module1 |

Regiehouder (s)i |

Jaar van autorisatie |

Eerstvolgende beoordeling actualiteit richtlijn2 |

Frequentie van beoordeling op actualiteit3 |

Wie houdt er toezicht op actualiteit4 |

Relevante factoren voor wijzigingen in aanbeveling5 |

|

Antipsychotica en aangeboren afwijkingen |

NVOG |

2021 |

2026 |

Eens in vijf jaar |

NVOG |

Nieuw onderzoek, beschikbaarheid nieuwe middelen |

1 Naam van de module

i Regiehouder van de module (deze kan verschillen per module en kan ook verdeeld zijn over meerdere regiehouders)

2 Maximaal na vijf jaar

3 (Half)Jaarlijks, eens in twee jaar, eens in vijf jaar

4 Regievoerende vereniging, gedeelde regievoerende verenigingen, of (multidisciplinaire) werkgroep die in stand blijft

5 Lopend onderzoek, wijzigingen in vergoeding/organisatie, beschikbaarheid nieuwe middelen

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling van deze richtlijn werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodules.

De richtlijn is ontwikkeld in samenwerking met:

- Patiëntenfederatie Nederland

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijn is in 2018 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor zwangere patiënten die ‘niet-SSRI’ antidepressiva en/of antipsychotica gebruiken. De werkgroepleden zijn door hun beroepsverenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname. De werkgroep is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze richtlijn.

Werkgroep

- Dr. A. Coumans, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht, NVOG

- Dr. H.H. Bijma, gynaecoloog, Erasmus Medisch Centrum, Rotterdam, NVOG

- Drs. R.C. Dullemond, gynaecoloog, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, Den Bosch, NVOG

- Drs. S. Meijer, gynaecoloog, Gelre Ziekenhuis, Apeldoorn, NVOG

- Dr. M.G. van Pampus, gynaecoloog, OLVG, Amsterdam, NVOG

- Drs. M.E.N. van den Heuvel, neonatoloog, OLVG Amsterdam, NVK

- Drs. E.G.J. Rijntjes-Jacobs, neonatoloog, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum, Leiden, NVK

- Dr. K.M. Burgerhout, psychiater, Amphia Ziekenhuis, Breda, NVvP

- Dr. E.M. Knijff, psychiater, Erasmus Medisch Centrum, Rotterdam, NVvP

Meelezers

- Dr. A.J. Risselada, klinisch farmacoloog, Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis Assen

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. E. van Dorp-Baranova, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. M. Moret-Hartman, senior-adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- N. Verheijen, senior-adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- M. Wessels, literatuurspecialist, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Dr. A. Coumans |

gynaecoloog-perinatoloog Maastricht UMC+ |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Dr. H. H. Bijma |

Gynaecoloog, Erasmus MC, afdeling verloskunde en gynaecologie, subafdeling verloskunde en prenatale geneeskunde |

lid werkgroep wetenschap LKPZ, onbetaald |

geen |

geen |

|

Drs. S. Meijer |

gynaecoloog Gelre Ziekenhuis, Apeldoorn |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Drs. R. C. Dullemond |

gynaecoloog- perinatoloog, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis |

LKPZ bestuur - voorzitter, onbetaald mind 2 care - raad van toezicht, onbetaald dagelijks bestuur @verlosdenbosch (integrale geboortezorg organisatie) als gynaecoloog uit het JBZ, onbetaald danwel deels in werktijd |

geen |

geen |

|

Drs. E. G. J. Rijntjes-Jacobs |

kinderarts-neonatoloog, afdeling neonatologie, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum |

LKPZ bestuur – secretaris, onbetaald |

geen |

geen |

|

Dr. M. G. van Pampus |

Gynaecoloog, OLVG Amsterdam |

onbetaalde nevenfuncties |

geen |

geen |

|

Dr. E. M. Knijff |

Psychiater, Erasmus MC polikliniek psychiatrie & zwangerschap medisch coördinator polikliniek Erasmus MC |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Drs. M. E. N. van den Heuvel |

kinderarts-neonatoloog, OLVG Amsterdam |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Dr. K. Burgerhout |

Psychiater, Reinier van Arkel, POP-poli |

geen |

geen |

geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er is een aantal acties uitgevoerd om het patiëntperspectief mee te nemen bij het ontwikkelen van deze richtlijn. Allereerst is contact gezocht met het MIND Platform voor afvaardiging van een patiëntvertegenwoordiger in de werkgroep. Zij hebben ons in contact gebracht met de Stichting Me Mam. Het bleek niet mogelijk een patiëntvertegenwoordiger voor de werkgroep te vinden. Daarna is een focusgroepbijeenkomst voor patiënten georganiseerd, maar deze is geannuleerd vanwege onvoldoende aanmeldingen. Tot slot is een schriftelijke enquête voor patiënten in samenwerking met de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland opgesteld en uitgezet. Dit heeft helaas nauwelijks reactie opgeleverd, de enquête is door twee patiënten ingevuld. Voor de ontwikkeling van het product voor patiënten (informatie op de website www.Thuisarts.nl) is een ervaringsdeskundige van de patiëntenvereniging ‘Plusminus-leven met bipolariteit’ afgevaardigd. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en het MIND Platform.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

In de verschillende fasen van de richtlijnontwikkeling is rekening gehouden met de implementatie van de richtlijnmodules en de praktische uitvoerbaarheid van de aanbevelingen. Daarbij is uitdrukkelijk gelet op factoren die de invoering van de richtlijn in de praktijk kunnen bevorderen of belemmeren. Het implementatieplan is te vinden in de bijlagen.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijn is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor vrouwen die antipsychotica of niet-SSRI antidepressiva tijdens zwangerschap en lactatie gebruiken. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door IGJ, NHG, V&VN, Zorginstituut Nederland, Lareb, KNOV, NVvP, NVOG en NVK via een Invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen in de bijlagen. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijn is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module 'Organisatie van zorg'.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijn werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijn aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijn werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/richtlijnontwikkeling.html.

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, Glasziou P, Jaeschke R, Vist GE, Williams JW Jr, Kunz R, Craig J, Montori VM, Bossuyt P, Guyatt GH; GRADE Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ. 2008 May 17;336(7653):1106-10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39500.677199.AE. Erratum in: BMJ. 2008 May 24;336(7654). doi: 10.1136/bmj.a139.

Schünemann, A Holger J (corrected to Schünemann, Holger J). PubMed PMID: 18483053; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2386626. BMJ. 2008 May 24;336(7654). doi: 10.1136/bmj.a139. Schünemann, A Holger J [corrected to Schünemann, Holger J]

Wessels M, Hielkema L, van der Weijden T. How to identify existing literature on patients' knowledge, views, and values: the development of a validated search filter. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016 Oct;104(4):320-324. PubMed PMID: 27822157; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5079497.

Zoekverantwoording

|

Database |

Search terms |

Total |

|

Medline (OVID)

Engels 1960-mrt 2019 |

1 exp antipsychotic agents/ or exp Butyrophenones/ or (antipsychotic* or anti-psychotic* or neuroleptic* or "major tranquilli*" or Bromperidol* or chlorpromazine* or chlorprothixene* or fluphenazine* or flupenthixol* or haloperidol* or penfluridol* or pimozide* or pipamperon* or aripiprazole* or clozapine* or olanzapine* or paliperidon* or quetiapine* or risperidone* or sulpiride*).ti,ab,kf. (aripiprazole/ or chlorpromazine/ or chlorprothixene/ or clozapine/ or flupenthixol/ or fluphenazine/ or haloperidol/ or olanzapine/ or paliperidone palmitate/ or penfluridol/ or pimozide/ or quetiapine fumarate/ or risperidone/ or sulpiride/ zijn onderliggende termen en worden automatische meegenomen met explode (exp)) (149579) 2 exp Pregnancy/ or exp Pregnancy Complications/ or Maternal Exposure/ or pregnan*.ti,ab,kf. or ("exposure* in utero" or ((intrauterine or intra-uterine or fetal or foetal or maternal) adj2 exposure*)).ti,ab,kf. or Prenatal Exposure Delayed Effects/ (991382) 3 1 and 2 (3685) 7 exp Congenital Abnormalities/ or Abnormalities, Drug-Induced/ or exp "Embryonic and Fetal Development"/ or Teratogens/ or ((birth or congenital) adj3 (defect* or anomal*)).ti,ab,kf. or (abnormalit* or malformation*).ti,ab,kf. or "long QT".ti,ab,kf. or cardiac.ti,ab,kf. or (teratogenic or teratoid*).ti,ab,kf. (1679251) 8 3 and 7 (660) 15 limit 8 to (english language and yr="1960 -Current") (549) 16 (meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (meta adj analy$).tw. or ((systematic* or literature) adj2 review$1).tw. or (systematic adj overview$1).tw. or exp "Review Literature as Topic"/ or cochrane.ab. or cochrane.jw. or embase.ab. or medline.ab. or (psychlit or psyclit).ab. or (cinahl or cinhal).ab. or cancerlit.ab. or ((selection criteria or data extraction).ab. and "review"/)) not (Comment/ or Editorial/ or Letter/ or (animals/ not humans/)) (386878) 17 15 and 16 (33) 18 (exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or random*.ti,ab. or (clinic* adj trial*).tw. or ((singl* or doubl* or treb* or tripl*) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo*.tw.) not (animals/ not humans/) (1841244) 19 15 and 18 (45) 20 Epidemiologic studies/ or case control studies/ or exp cohort studies/ or Controlled Before-After Studies/ or Case control.tw,kw. or (cohort adj (study or studies)).tw,kw. or Cohort analy$.tw,kw. or (Follow up adj (study or studies)).tw,kw. or (observational adj (study or studies)).tw,kw. or Longitudinal.tw,kw. or Retrospective.tw,kw. or Prospective.tw,kw. or Cross sectional.tw,kw. or Cross-sectional studies/ or historically controlled study/ or interrupted time series analysis/ (Onder exp cohort studies vallen ook longitudinale, prospectieve en retrospectieve studies) (2866115) 21 15 and 20 (122) 22 19 or 21 (148) 23 22 not 17 (134) – 133 uniek |

275 |

|

Embase (Elsevier) |