Antidepressiva (niet SSRI’s) en zwangerschaps- en baringscomplicaties

Uitgangsvraag

Welke niet-SSRI antidepressiva hebben de voorkeur voor gebruik in de zwangerschap met betrekking tot het risico op zwangerschaps- en baringscomplicaties?

Aanbeveling

Bespreek met de zwangere dat bij gebruik van een niet-SSRI antidepressivum, met uitzondering van MAO-remmers, er geen reden is om te switchen naar een ander middel op basis van de huidige gegevens met betrekking tot het risico op zwangerschaps- en baringscomplicaties, zoals pre-eclampsie, spontane abortus, IUVD, fluxus postpartum, premature partus. MAO-remmers worden in principe afgeraden vanwege hun bijwerkingenprofiel, interactie met andere medicatie, specifiek dieet en specifieke maatregelen bij anesthesie. Er is geen voorkeursmiddel voor de overige niet-SSRI antidepressiva voorhanden op basis van de literatuur.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

De kwaliteit van het bewijs is zeer laag voor meeste uitkomstmaten. De schatting van het effect is zeer onzeker. Voor de uitkomstmaten pre-eclampsie en spontane abortus is de kwaliteit van het bewijs laag. Er is een lage zekerheid dat het ware effect van het gebruik van niet-SSRI antidepressiva op het ontstaan van pre-eclampsie en spontane abortus dichtbij het door de onderzoeken geschatte effect ligt.

Er is geen bewijs dat niet-SSRI antidepressiva een verhoogd risico op intra-uteriene vruchtdood, fluxus postpartum, of premature partus geven, hoewel de kwaliteit van de onderzochte studies te wensen overliet.

Een aantal middelen van de niet-SSRI antidepressiva vereisen meer hoog specialistische zorg dan anderen, waarbij gebruik tijdens de zwangerschap geen voorkeur heeft. Dit geldt bijvoorbeeld voor het gebruik van MAO-remmers tijdens de zwangerschap. Dit wordt afgeraden vanwege eerder beschreven bijwerkingen profiel, interactie met andere medicatie, specifiek dieet en specifieke maatregelen bij anesthesie. Indien toch een MAO-remmer wordt gebruikt, is het zinvol de zwangere te begeleiden een centrum met specialistische expertise.

Overige geraadpleegde bronnen

De NICE guideline geeft geen concrete adviezen over het gebruik van antidepressiva tijdens zwangerschap en lactatie. Wel is het advies om de laagst effectieve dosis te gebruiken, en er rekening mee te houden dat de dosering aangepast moet worden tijdens de zwangerschap. Houd er rekening mee bij vrouwen die TCA’s, SNRI gebruiken en die borstvoeding geven dat er beperkte data zijn over de veiligheid van deze medicatie.

Farmacologische overwegingen

Indien vrouwen een niet-SSRI antidepressivum gebruiken en zwanger willen worden is het advies om per patiënt een zorgvuldig overzicht te maken van de diagnose, ziekteperiode(s), gebruikte psychofarmaca, ervaren effect, dosering, eventueel ervaren bijwerkingen en de huidige klachten en medicatie.

Derhalve adviseren wij vrouwen die een antidepressivum gebruiken, voordat zij zwanger worden, een POP-poli/ team te bezoeken. Hier kunnen specialisten op het gebied van psychiatrie, obstetrie en pediatrie na inventarisatie van bovenstaande, meedenken over de voor- en nadelen van medicatiegebruik tijdens de zwangerschap en in de postpartum periode.

Indien er wordt besloten medicatie te gebruiken is het altijd goed om een middel van voorkeur tijdens de zwangerschap en zo mogelijk lactatie te gebruiken. Dit zijn medicijnen waarmee al langere tijd ervaring is tijdens de zwangerschap en kraamperiode en derhalve als veilig voor moeder en kind worden beschouwd. Er kan niet altijd voor een van de voorkeursmedicijnen gekozen worden, bijvoorbeeld als patiënte in het verleden, ondanks adequate behandeling, geen effect van de medicatie heeft gehad, dan wel forse bijwerkingen heeft ervaren. Tevens wordt ook altijd geadviseerd de laagst mogelijke, effectieve dosis gedurende zwangerschap en eventueel tijdens de lactatieperiode te gebruiken.

Zwangerschap is vaak een periode van toegenomen stress vanwege de nieuwe levensfase, lichamelijke veranderingen en zorgen om de toekomst. Dit maakt de kans op een terugval groter dan buiten de zwangerschap. Daarom adviseert de werkgroep medicatie te continueren na een goede afweging van de risico’s.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten

De manier en inhoud van de voorlichting aan patiënte heeft grote invloed op de keuze al dan niet door te gaan met medicatie. In de praktijk blijkt vaak dat behandelaars met minder ervaring met psychofarmaca en zwangerschap eerder geneigd zijn te stoppen met psychofarmaca. Vanuit de POP-poli/ team is na goede counseling de ervaring dat patiënten juist wél hiermee doorgaan. In de afweging om te stoppen of door te gaan met de psychofarmaca is de balans tussen de toxicologische risico’s voor het kind, de kans op een terugval danwel exacerbatie van de ziekte en de gevolgen hiervan voor het kind belangrijke afwegingen.

Kosten

Psychofarmaca gebruiken en poliklinische begeleiding door een psychiatrisch team en gynaecoloog zijn in verhouding goedkoper dan een spoedopname bij ernstige terugval van de psychiatrische ziekte. Een ander belangrijk aspect is de emotionele schade voor de moeder en de eventuele gevolgen voor het ongeboren kind, als de moeder een forse ziekteperiode doormaakt in haar zwangerschap.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De expertise van de betrokken behandelaren in dit land is meegenomen in deze overweging. Aangezien er weinig evidence-based literatuur beschikbaar is voor dit onderwerp hebben betrokken experts uit geheel Nederland samen besproken wat de aanbeveling is. Behalve de werkgroep hebben ook andere experts uit het land de mogelijkheid gekregen hun visie op deze aanbeveling te geven. De werkgroep verwacht hierna geen bezwaren tegen implementatie van deze richtlijn.

Rationale/ balans tussen de argumenten voor en tegen de interventie

Gebruik, indien nodig, medicatie na een goede afweging van de risico’s. Hierbij dient gekozen te worden voor medicatie die beschouwd wordt als meest veilig in zwangerschap en bij lactatie. Streef hierbij naar monotherapie en laagste effectieve dosering. Gebruik de laagst effectieve dosis, houd er rekening mee dat de dosering soms aangepast moet worden tijdens de zwangerschap.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Tijdens de zwangerschap is bij 7 tot 20% van de vrouwen sprake van klinisch relevante angst- en/of stemmingsklachten (Biaggi, 2016). Antidepressiva passeren de placenta en hebben derhalve mogelijk gevolgen voor de foetus en neonaat (Ewing, 2015). Het is onduidelijk wat de neonatale effecten en symptomen zijn van niet-SSRI-antidepressiva op de neonaat.

Niet-SSRI antidepressiva bestaan uit diverse groepen zoals de tricyclische antidepressiva (amitriptyline, clomipramine, imipramine, nortriptyline), serotonineheropnameremmers (SNRI’s: venlafaxine, duloxetine),de MAO-remmers (moclebemide, fenelzine, tranylcypromine) en overige antidepressiva (bupropion, mirtazapine, trazodon, vortioxine). Vrouwen met een kinderwens of prille zwangerschap staken nu soms de niet-SSRI antidepressiva uit angst voor de mogelijke foetale effecten. De vraag is of dit veilig kan en of dit geen toename van psychische klachten geeft. Het is tot op heden niet duidelijk of het staken of juist het continueren van de medicatie tot een betere uitkomst leidt voor moeder en kind. Het staken van de medicatie kan mogelijk de ziekte juist verergeren wat in een zwangerschap, die op zich al een emotionele belasting kan zijn, niet gewenst is. Het is een balans tussen de ziekte van de moeder, de voor- en nadelen van antidepressiva gebruik en de veiligheid van het eventuele staken tijdens deze kwetsbare periode.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Pre-eclampsia

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the risk of pre-eclampsia in pregnant women with psychiatric disorders using TCA’s compared to untreated pregnant women with depression.

Bronnen: (Avalos, 2015; Palmsten, 2012; Palmsten, 2013b) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the risk of pre-eclampsia in pregnant women with psychiatric disorders using SNRI’s, compared to untreated pregnant women with depression.

Bronnen: (Avalos, 2015; Palmsten, 2012; Palmsten, 2013b) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the risk of pre-eclampsia in pregnant women treated with NDRI’s, compared to untreated pregnant women with depression.

Bronnen: (Avalos, 2015) |

Miscarriage (spontaneous abortion)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the risk of spontaneous abortion in pregnant women treated with TCA’s, compared to women not using antidepressants.

Bronnen: (Nakhai-Pour, 2010; Chun-Fai-Chan, 2005) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the risk of spontaneous abortion in pregnant women treated with SNRI’s (venlafaxine), compared to women not using antidepressants during pregnancy.

Bronnen: (Nakhai-Pour, 2010; Richardson, 2019; Einarson, 2001) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the risk of spontaneous abortion in pregnant women treated with bupropion, compared to pregnant women not using antidepressants.

Bronnen: (Nakhai-Pour, 2010; Chun-Fai-Chan, 2005) |

Stillbirth

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the risk of stillbirth in women using TCA’s during pregnancy, compared to pregnant women unexposed to antidepressants or using SSRI’s.

Bronnen: (Richardson, 2019) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of SNRI’s (venlafaxine) on the risk of stillbirth in women using this antidepressant during pregnancy, compared to pregnant women unexposed to antidepressants or using SSRI’s.

Bronnen: (Richardson, 2019) |

Postpartum hemorrhage

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of TCA’s on the risk of postpartum hemorrhage in women using these antidepressants during pregnancy, compared to pregnant women unexposed to antidepressants.

Bronnen: (Lupatelli, 2014) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of SNRI’s on the risk of postpartum hemorrhage in women using these antidepressants during pregnancy, compared to untreated pregnant women with depression.

Bronnen: (Palmsten, 2013a) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of bupropion on the risk of postpartum hemorrhage in women using this antidepressant during pregnancy, compared to pregnant women with untreated depression.

Bronnen: (Palmsten, 2013a) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of mirtazapine on the risk of postpartum hemorrhage in women using this antidepressant during pregnancy, compared to pregnant women with untreated depression.

Bronnen: (Palmsten, 2013a) |

|

- GRADE |

No conclusions could be drawn about the risk of premature delivery, gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia, placental abnormalities, delivery by caesarean section, ectopic pregnancy, pregnancy-induced hypertension, forceps delivery and vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery after use of non-SSRI antidepressants during pregnancy, compared with no use of antidepressants or use of SSRI’s, in women with psychiatric disorders, because of the absence of relevant comparative studies. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Pre-eclampsia was described in 3 studies (Avalos, 2015; Palmsten, 2012; Palmsten, 2013b). All studies were population-based register-based cohort studies. Avalos (2015) used clinical and pharmacy databases of Kaiser Permanente Northern California, a health coverage organization. Palmsten (2012) used health care utilization databases form British Colombia, linked to PharmaNET database. Pharmanet supplies distribution software for pharmaceuticals. Palmsten (2013b) used Medicaid data linked to pharmacy dispensing data. Medicaid is a government insurance program for persons whose income is insufficient to pay for health care. As such, women enrolled by Palmsten (2013b) might be of other SES than women in the other 2 studies.

The control group in all 3 studies consisted of pregnant women with untreated depression. Defined exposure periods were different in these 3 studies, as were the type of investigated antidepressants and definition of depression diagnosis. An overview of these differences is presented in table 1. In all 3 studies, preeclampsia was diagnosed by ICD-9 codes.

Table 1 Differences regarding definitions of exposure and depression and differences regarding AD class for studies investigating pre-eclampsia

|

Author, year |

Definition of exposure |

AD class |

Depression diagnosis |

|

Avalos, 2015 |

At least 1 dispensing record 1-20w pregnancy |

TCA only SNRI only NDRI only |

Depression at 1st visit / Depression diagnosis / Taking antidepressants |

|

Palmsten, 2012 |

AD exposure: >=1 dispensing during 10-20w pregnancy No AD exposure: >1jr-20w

Continued AD: dispensing 10-24w Discontinued AD: no AD wk 10-24 |

TCA only SNRI only |

1 inpatient or outpatient ICD9 depression diagnosis 1y before pregnancy-20w |

|

Palmsten, 2013b |

Exposed dispensing 13w-32w Unexposed: LMP-32w

Continued AD: during 13w-32w Discontinuers: no AD 13w-32w |

TCA only SNRI only Bupropion only Other only |

1 inpatient or outpatient ICD-9 depression LMP-225days |

AD: antidepressant(s), TCA: tricyclic antidepressants; NDRI: norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor; SNRI: serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; LMP: last menstrual period

Four studies reported on spontaneous abortion, of which 3 were population based, register-based cohort studies (Chun-Fai-Chan, 2005; Einarson, 2001; Richardson, 2019) and one was a nested case-control study (Nakhai-Pour, 2010). Chun-Fai-Chan (2005) and Einarson (2001) both used data from the Canadian Motherrisk Program. In which period data were collected is for both studies unknown. Case groups were not comparable: Einarson (2001) used data of women calling the Motherrisk Program for information regarding safety of venlafaxine. The other 3 studies (Chun-Fai-Chan, 2005; Nakhai-Pour, 2010; Richardson, 2019) identified cases from multiple linked databases. In the study by Nakhai-Pour (2010) one of the databases was of a health care coverage plan. Richardson used a teratology-registration database. Also, studies were not comparable regarding type of antidepressant, exposure period and defined control group. Differences between these 4 studies in definition of exposition, AD class, control group and definition of spontaneous abortion are summarized in table 2. Finally, in the case group of Chun-Fai-Chan’s study (2005), 3 twin pairs were included.

Table 2 Differences regarding definition of exposure, AD class, control group and definition of spontaneous abortion for studies investigating spontaneous abortion

|

Author, year |

Definition of exposure |

Antidepressant |

Controls |

Spontaneous abortion |

|

Chun-Fai-Chan, 2005 |

Measured by questionnaire

drug consumed at least in 1st trimester |

Bupropion |

Women using NTD |

No definition |

|

Einarson, 2001 |

Measured by questionnaire,

Exposure between 4th-14th week GA |

Venlafaxine |

Women using NTD

|

By letter from primary care physician |

|

Nakhai-Pour, 2010 |

Info from database

>=1 dose of AD from 1st day GA - date of spontaneous abortion |

TCA SNRI Venlafaxine

|

Women not using AD, a minority had a psychiatric disorder |

Clinically detected spontaneous abortions 1st day - 20th week |

|

Richardson, 2019 |

Info from database

Use at any stage of pregnancy |

Venlafaxine |

1. women, nondepressed, antidepressant unexposed, non-teratogenic drugs use 2. matched SSRI-exposed women |

Reported spontaneous abortion < 24 weeks GA |

AD: antidepressants; SSRI: selective serotonine reuptake inhibitors; TCA: tricyclic antidepressants; SNRI: serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; NTD: non-teratogenic drugs; GA: gestational age

Only the study by Richardson (2019) presented data on stillbirth/intrauterine fetal death, defined as pregnancies ending in elective termination or spontaneous abortion at or over 24 weeks of gestational age.

Two studies (Lupatelli, 2014; Palmsten, 2013a) reported on postpartum hemorrhage, both were cohort studies. In the study by Lupatelli (2014), women were recruited by postal invitation in connection with routine ultrasound at 17 to 18 weeks of gestational age. Cases, using either TCA’s or other antidepressants, were compared to nonexposed controls without presence of depression between gestational weeks 17 to 30. Information on exposure was collected by self-administered questionnaires, during pregnancy and retrospective, 6 months after delivery. Numbers in this study were small. The study by Palmsten (2013a) included women with an ICD9 code for mood or anxiety disorder, 1 to 5 months prior to pregnancy, who were enrolled in Medicaid. Identification via Medicaid databases might introduce SES as a possible confounder. Based on pharmacy dispensing data exposure to different types of antidepressants during pregnancy was classified as current, recent or past. Postpartum haemorrhage was defined as ICD-9 666.x during admission to hospital for delivery, or within three days after delivery for outpatient deliveries.

There were no comparative studies, investigating the association between the use of non-SSRI antidepressants during pregnancy and the critical outcome measures ‘gestational diabetes’, ‘preterm delivery (< 37 weeks)’, ‘placental abnormalities (placenta previa, abruptio placentae)’, ‘delivery by caesarean section’. Also, for the following important outcome measures: ‘ectopic pregnancy’, ‘pregnancy-induced hypertension’, ‘forceps delivery’ and ‘vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery’, no comparative studies were found.

Results

Risk of (pre-)eclampsia (critical outcome)

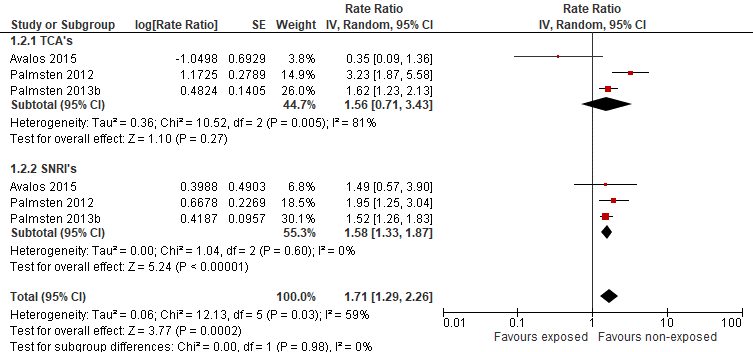

Avalos (2015) found no increased risk of pre-eclampsia after exposure to TCAs, when compared to untreated women with depression. The number of events was small. Adjusted relative risks were calculated, correcting for BMI, age, ethnicity, marital status, parity, alcohol use, smoking, diabetes, other indications for antidepressant medications and other mental health diagnoses. In contrary, Palmsten (2012) and Palmsten (2013b) found an elevated risk of pre-eclampsia in pregnant women using TCAs, after correction for risk factors for pre-eclampsia and factors related to depression severity. A forrest plot with adjusted RR’s was calculated (figure 1).

Avalos (2015) did not find a significant difference between pregnant women using SNRI’s, compared to pregnant women not using antidepressants. In contrary, Palmsten (2012) found an elevated risk of pre-eclampsia in women using SNRI’s during pregnancy, compared to depressed women not using antidepressants, as did Palmsten (2013b). A forrest plot with adjusted RR’s was calculated (figure 1).

Regarding use of NDRIs during pregnancy, Avalos (2015) did not find differences for pre-eclampsia compared to depressed pregnant women, not using antidepressants. The adjusted RR was 1.23 (95%CI 0.57 to 2.67).

Figure 1 Risk of pre-eclampsia after exposure to antidepressants (non-SSRI’s) (adjusted RR)

Finally, Palmsten (2013b) reported risk estimates for single antidepressants, compared to depressed pregnant women, not using antidepressants. Adjusted RR’s are presented in table 3.

Table 3 Risk estimates for pre-eclampsia, when using antidepressant monotherapy during pregnancy, compared to no use of antidepressants during pregnancy (Palmsten, 2013)

|

Antidepressant as monotherapy |

Palmsten 2013b |

|

Bupropion |

n=153 (6%) Adjusted RR:1.06 (95%CI: 0.91–1.25) |

|

Venlafaxine |

n=100 (9%) Adjusted RR: 1.57 (95%CI: 1.29–1.91) |

|

Amitriptyline |

n=31 (11%) Adjusted RR: 1.72 (95%CI: 1.24–2.40) |

|

Trazodone |

n=14 (4%) Adjusted RR: 0.63 (95%CI: 0.38–1.05) |

|

Mirtazapine |

n=14 (6%) Adjusted RR: 0.81 (95%CI: 0.50–1.34) |

Risk of spontaneous abortion (critical outcome)

In this literature analysis the term ‘spontaneous abortion’ was used for reporting the risk of miscarriage, because this term was used in the included studies.

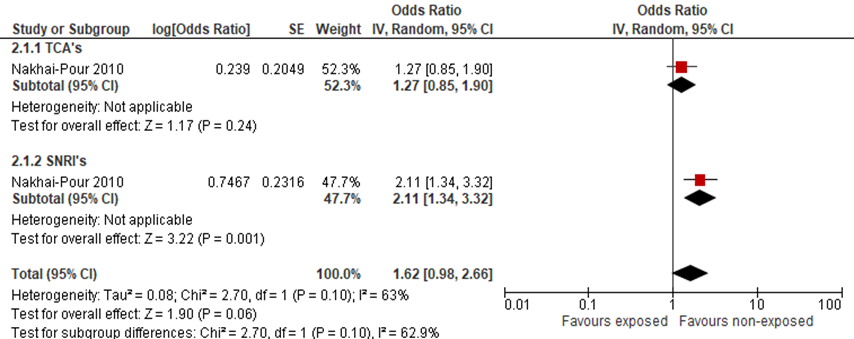

TCAs

Nakhai-Pour (2010) did not find an elevated odds radio of spontaneous abortion when comparing pregnant women, using TCA’s during pregnancy with women not using antidepressants (figure 2).

SNRI (venlafaxine)

Three authors (Einarson, 2001; Nakhai-Pour, 2010; Richardson, 2019) reported on the odds of spontaneous abortion when using venlafaxine during pregnancy, compared to women using only nonteratogenic drugs. For women using SNRI’s during pregnancy, Nakhai-Pour (2010) found an elevated adjusted odds ratio for spontaneous abortion, adjusted OR was 2.11 (95%CI: 1.34 to 3.30). The studies by Einarson and Richardson did not report adjusted odds ratio’s and are therefore not included in this figure.

Only the study by Richardson (2019) compared women using venlafaxine during pregnancy with pregnant women using SSRIs, regarding the risk of spontaneous abortion. However, numbers were small and only unadjusted ORs were presented.

Additionally, Nakhai-Pour (2010) described a significant dose-dependent difference for spontaneous abortion when using venlafaxine. The odds ratio for spontaneous abortion was elevated when the daily dose of venlafaxine exceeded 150mg/day (p<0.05), compared to pregnant women not using antidepressants. Numbers were small.

NDRI (bupropion)

Chun-Fai-Chan (2005) described an elevated rate of spontaneous abortion in women using bupropion during the first trimester of pregnancy, compared to pregnant women using nonteratogenic drugs.

Figure 2 Risk of spontaneous abortion after exposure to antidepressants (non-SSRI’s) (adjusted OR)

Risk of stillbirth (critical outcome)

Only Richardson reported on stillbirth. When comparing women using venlafaxine at any stage during pregnancy, to SNRI-unexposed women, no difference was found OR 1.36 (95%CI: 0.25 to 5.11). Also, when women using venlafaxine were compared to pregnant women specifically using a SSRI, no difference in the rate of stillbirth was found, unadjusted OR 1.32 (95%CI: 0.219 to 5.85).

Risk of postpartum hemorrhage (important outcome)

Lupatelli (2014) described an elevated risk of postpartum hemorrhage by any type of delivery, when comparing women using TCA/other antidepressants, with non-depressive women, not using antidepressants. The adjusted OR was 3.75 (95%CI: 1.09 to 12.94). Nothing could be said about the relation between use of antidepressants and postpartum hemorrhage after cesarean section or vaginal delivery, because numbers were too small.

Palmsten (2013a) found an elevated risk of postpartum hemorrhage, when women used an SNRI (venlafaxine) at the delivery date, compared to depressive pregnant women not using antidepressants, adjusted relative risks were 1.39 (95%CI: 1.07 to 1.81), and 2.24 (95%CI: 1.69 to 2.97), respectively.

When using bupropion 1 to 5 months before delivery, the adjusted elevated risk on postpartum hemorrhage was 1.32 (95%CI: 1.02 to 1.69), compared to depressive pregnant women not using antidepressants (Palmsten, 2013a). This elevated effect was not described when using bupropion close to (aRR 1.17 (95%CI: 0.77 to 1.79) or at the delivery date 1.32 (95%CI: 0.98 to 1.79) (Palmsten, 2013a). For the above described case and control group, mirtazapine had no effect when used at delivery date on postpartum hemorrhage, aRR 0.87 (95%CI: 0.29 to 2.66).

Risk of gestational diabetes (critical outcome)

No studies assessed the association of non-SSRI antidepressant use with the risk of gestational diabetes in women with psychiatric disorders, compared to women not taking non-SSRI antidepressants.

Risk of placental abnormalities (placenta previa, abruptio placentae) (critical outcome)

No studies assessed the association of non-SSRI antidepressant use with the risk of placental abnormalities in women with psychiatric disorders, compared to women not taking non-SSRI antidepressants.

Risk of preterm delivery (< 37 weeks) (critical outcome)

No studies assessed the association of non-SSRI antidepressant use with the risk of gestational diabetes in women with psychiatric disorders, compared to women not taking non-SSRI antidepressants.

Risk of delivery by caesarean section (critical outcome)

No studies assessed the association of non-SSRI antidepressant use with the risk of delivery by caesarean section in women with psychiatric disorders, compared to women not taking non-SSRI antidepressants.

Risk of ectopic pregnancy (important outcome)

No studies assessed the association of non-SSRI antidepressant use with the risk of ectopic pregnancy in women with psychiatric disorders, compared to women not taking non-SSRI antidepressants.

Risk of pregnancy-induced hypertension (important outcome)

No studies assessed the association of non-SSRI antidepressant use with the risk of pregnancy-induced hypertension in women with psychiatric disorders, compared to women not taking non-SSRI antidepressants.

Risk of forceps delivery (important outcome)

No studies assessed the association of non-SSRI antidepressant use with the risk of forceps delivery in women with psychiatric disorders, compared to women not taking non-SSRI antidepressants.

Risk of vacuum-assisted delivery (important outcome)

No studies assessed the association of non-SSRI antidepressant use with the risk of vacuum-assisted delivery in women with psychiatric disorders, compared to women not taking non-SSRI antidepressants.

Level of evidence of the literature

In many of the used studies, the exposure to antidepressants during pregnancy was extracted from registration data in databases, which yields a risk of misclassification. In other studies, the population consisted of women who contacted a counselling services or teratology information services which may be a risk for selection bias. Control groups in some studies consisted of women exposed to other nonteratogenic drugs, or women who had not been diagnosed with depression, which deviated from the population we are interested in (indirectness).

The quality of evidence for TCA’s regarding the critical outcome measure ‘risk of pre-eclampsia’ was downgraded because of study limitations (risk of bias due to misclassification) and clinical heterogeneity (inconsistency of results), resulting in a very low level of evidence.

The quality of evidence for SNRI’s (venlafaxine) regarding the critical outcome measure ‘risk of pre-eclampsia’ was downgraded because of study limitations (risk of bias due to misclassification) and clinical heterogeneity (inconsistency of results), resulting in a very low level of evidence.

The quality of evidence for NDRI’s regarding the critical outcome measure ‘risk of pre-eclampsia’ was downgraded because of study limitations (risk of bias due to misclassification) and serious imprecision (only one study with a few events), resulting in a very low level of evidence.

The quality of evidence for TCA’s regarding the critical outcome measure ‘risk of spontaneous abortion’ was downgraded because of study limitations (risk of bias due to misclassification), indirectness (only a minority of controls had a depression) and imprecision (only one study with a few events), resulting in a very low level of evidence.

The quality of evidence for SNRI’s regarding the critical outcome measure ‘risk of spontaneous abortion’ was downgraded because of study limitations (risk of bias due to misclassification) and indirectness (only a minority of controls had a depression)., resulting in a very low level of evidence.

The quality of evidence for bupropion regarding the critical outcome measure ‘risk of spontaneous abortion’ was downgraded because of study limitations (risk of bias due to misclassification), indirectness (only a minority of controls had a depression) and imprecision (only one study with a few events), resulting in a very low level of evidence.

The quality of evidence for venlafaxine regarding the critical outcome measure ‘risk of stillbirth’ was downgraded because of study limitations (risk of bias due to misclassification), indirectness (controls did not have depression) and serious imprecision (one study), resulting in a very low level of evidence.

The quality of evidence for TCA’s, SNRI’s regarding the critical outcome measure ‘risk of stillbirth’ could not be assessed due to the absence of relevant literature.

The quality of evidence for TCA’s regarding the critical outcome measure ‘postpartum hemorrhage’ was downgraded because of study limitations (risk of bias due to misclassification), indirectness (comparison with women without depression) and serious imprecision (one study), resulting in a very low level of evidence.

The quality of evidence for SNRI’s regarding the critical outcome measure ‘postpartum hemorrhage’ was downgraded because of study limitations (risk of bias due to misclassification), indirectness (comparison with women without depression) and serious imprecision (one study), resulting in a very low level of evidence.

The quality of evidence for bupropion regarding the critical outcome measure ‘postpartum hemorrhage’ was downgraded because of study limitations (risk of bias due to misclassification), indirectness (comparison with women without depression) and serious imprecision (one study), resulting in a very low level of evidence.

The quality of evidence for mirtazapine regarding the critical outcome measure ‘postpartum hemorrhage’ was downgraded because of study limitations (risk of bias due to misclassification), indirectness (comparison with women without depression) and serious imprecision (one study), resulting in a very low level of evidence.

Due to the absence of relevant literature, the level of evidence for the outcome measures ‘preterm delivery’, ‘gestational diabetes’, ‘pre-eclampsia’, ‘placental abnormalities’, ‘delivery by caesarean section’, ‘ectopic pregnancy’, ‘pregnancy-induced hypertension’, ‘forceps delivery’ and ‘vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery’, could not be assessed.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following questions:

1. What is the risk of pregnancy and labor complications in women taking non-SSRI-antidepressants during pregnancy, compared to healthy pregnant women?

P: patients: pregnant women;

I: intervention: use of non-SSRI antidepressants during pregnancy;

C: control: no use of non-SSRI antidepressants;

O: outcome: risk of gestational diabetes, pregnancy-induced hypertension, pre-eclampsia, spontaneous abortion, placental abnormalities (placenta previa, abruptio placentae), ectopic pregnancy, stillbirth, risk of preterm delivery (< 37 weeks), risk of delivery by caesarean section, risk of forceps delivery, risk of vacuum-assisted delivery, risk of postpartum hemorrhage (total blood loss (TBL)>500 ml).

2. What is the risk of pregnancy and labor complications in women with psychiatric disorders taking non-SSRI-antidepressants during pregnancy, compared to women with psychiatric disorders not taking antidepressants or taking a different (non-SSRI) antidepressant?

P: patients: pregnant women with psychiatric disorders;

I: intervention: use of non-SSRI antidepressants during pregnancy;

C: control: no use of non-SSRI antidepressants or use of a different (non-SSRI) antidepressant (comparison between different antidepressants);

O: outcome: risk of gestational diabetes, pregnancy-induced hypertension, pre-eclampsia, spontaneous abortion, placental abnormalities (placenta previa, abruptio placentae), ectopic pregnancy, stillbirth, risk of preterm delivery (< 37 weeks), risk of delivery by caesarean section, risk of forceps delivery, risk of vacuum-assisted delivery, risk of postpartum hemorrhage (total blood loss (TBL) >500 ml).

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered the risk of gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia, spontaneous abortion, placental abnormalities (placenta previa, abruptio placentae), stillbirth, preterm delivery (< 37 weeks) and delivery by caesarean section as critical outcome measures, and the risk of ectopic pregnancy, pregnancy-induced hypertension, postpartum hemorrhage (TBL>500 ml), forceps delivery and vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery as important outcome measures for decision making.

The minimal (clinically) important difference was defined according to the default recommendations of the international GRADE working group, as follows: for dichotomous outcomes as a relative risk reduction or an increase of 25% or more, and for continuous outcomes as a difference of half (0.5) a standard deviation.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from the 1st of January 1960 until the 29th of July 2019. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 832 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews (with meta-analyses), randomized controlled trials and comparative observational (case-control and cohort) studies, investigating the risk of pregnancy and labor complications in women with psychiatric disorders taking non-SSRI antidepressants during pregnancy, compared with healthy pregnant women, and pregnant women with psychiatric disorders not taking antidepressants or taking a different class antidepressant, or a different non-SSRI antidepressant. Twenty-eight studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 19 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and 9 studies were included.

Results

Nine studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Avalos, L.A., Chen, H. &Li, D.K. (2015). Antidepressant medication use, depression, and the risk of preeclampsia. Cns Spectrums, 20(1), 39-47.

- Biaggi, A., Conroy, S., Pawlby, S., & Pariante, C. M. (2016). Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: a systematic review. Journal of affective disorders, 191, 62-77.

- Chun-Fai-Chan, B., Koren, G., Fayez, I., Kalra, S., Voyer-Lavigne, S., Boshier, A., Shakir, S. & Einarson, A. (2005). Pregnancy outcome of women exposed to bupropion during pregnancy: a prospective comparative study. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 192(3), 932-6.

- Einarson, A.,,Fatoye, B., Sarkar, M., Lavigne, S., Brochu, J., Chambers, C., Mastroiacovo, P., Addis, A., Matsui, D., Schuler, L., Einarson, T. R. & Koren, G. (2001). Pregnancy outcome following gestational exposure to venlafaxine: a multicenter prospective controlled study. American Journal of Psychiatry 158(10), 1728-30.

- Ewing, G., Tatarchuk, Y., Appleby, D., Schwartz, N., & Kim, D. (2015). Placental transfer of antidepressant medications: implications for postnatal adaptation syndrome. Clinical pharmacokinetics, 54(4), 359-370.

- Lupattelli, A., Spigset, O., Koren, G. & Nordeng, H. (2014). Risk of vaginal bleeding and postpartum hemorrhage after use of antidepressants in pregnancy: a study from the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical psychopharmacology 34(1), 143-8.

- Nakhai-Pour, H. R., Broy, P. & Berard, A. (2010). Use of antidepressants during pregnancy and the risk of spontaneous abortion. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal 182(10), 1031-7.

- Palmsten, K., Hernandez-Diaz, S., Huybrechts, K.F., Williams, P.L., Michels, K.B., Achtyes, E.D., Mogun, H., & Setoguchi, S. (2013a). Use of antidepressants near delivery and risk of postpartum hemorrhage: cohort study of low income women in the United States. BMJ 347(f4877).

- Palmsten, K.,Huybrechts, K.F., Michels, K.B., Williams, P.L., Mogun, H., Setoguchi, S. & and Hernández-Díaz, S. (2013b). Antidepressant use and risk for preeclampsia. Epidemiology 24(5), 682-691.

- Palmsten, K., Setoguchi, S., Margulis, A.V., Patrick, A R. & Hernandez-Diaz, S. (2012). Elevated risk of preeclampsia in pregnant women with depression: depression or antidepressants? American Journal of Epidemiology 175(10), 988-97

- Richardson, J.L.. and Martin, F., Dunstan, H., Greenall, A., Stephens, S., Yates, L.M. &Thomas, S.H.L. (2019). Pregnancy outcomes following maternal venlafaxine use: A prospective observational comparative cohort study. Reproductive Toxicology 84, 108-113.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, case series))

Research question: What is the risk of pregnancy and labor complications in women with psychiatric disorders taking non-SSRI antidepressants during pregnancy, compared with healthy women and women with psychiatric disorders not taking antidepressants or taking a different class antidepressant or a differtent non-SSRI antidepressant?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison/control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Avalos 2015

USA |

Type of study: retrospective, population-based cohort study

Setting and country: linked automated clinical and pharmacy databases including electronic medical records, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: All authors work at Kaiser Permanente Northern California, division of research. Funded by a grant by Kaiser Permanente Community Benefits and UCSF-Kaiser/DOR Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health Program |

Inclusion criteria: Pregnant women, >=18y, entering prenatal care, gave birth Jan 1, 2010 – Dec 31, 2012, Kaiser Permanente Northern California members, screened for depression at first prenatal visit, or had a depression diagnosis or were taking antidepressants during pregnancy. Only 1st pregnancy included

Exclusion criteria: women with multi-fetal gestations, history of hypertension,

Mean age ± SD: no mean, 6 classes

Potential confounders or effect modifiers: maternal characteristics, alcohol use, smoking, comorbidities, gestational diabetes, other indications for antidepressant, other mental health disorders |

Describe intervention: Antidepressant use during pregnancy was defined as having at least one pharmacy dispensing record for the time period between the first day of the woman's last menstrual period (LMP) and 20 completed weeks of gestation

Use of antidepressants N = 1732 use of TCA only n=116 Use of SNRI only n=72 Use of NDRI only N=118

|

Controls: Women with untreated depression N=21589

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: N/A

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%): N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available): Pre-eclampsia; ICD-9 codes occurring after 20 weeks gestation: 642.4, 642.5, 642.6, or 642.7.

use of TCA only Preeclampsia N=2 in exposed; N=719 in unexposed aRR 0.35 (95%CI 0.09-1.47)

Use of SNRI only Pre-eclampsia N=5 in exposed; N=719 in unexposed aRR 1.49 (95%CI 0.57-3.90)

Use of NDRI only Preeclampsia N=8 in exposed, N=719 in unexposed aRR 1.23 (95%CI 0.57-2.67)

|

Author’s conclusion: —Study findings suggest that the antidepressant use during pregnancy may increase the risk of preeclampsia, especially the use during the second trimester. |

|

Chun-Fai-Chan 2005

UK |

Type of study: cohort study

Setting and country: 1. The Motherisk Program (Toronto, Canada), 2. The Pregnancy Riskline (Farminmington, Conn), or 3. registration from The Drug Safety Research Unit (Southampton, UK),

Funding and conflicts of interest: N/A

|

Inclusion criteria: Women in 1st trimester of pregnancy, taking bupropion, who contacted 1,2 or 3. Period of data collection: unknown

Exclusion criteria: unknown

Mean age ± SD: unknown

Potential confounders or effect modifiers: matching: age of participant, alcohol consumption, smoking. gestational age at time of call to Motherisk program, only at 1 of 3 sites of datacollection |

Describe intervention: Questionnaire Request for monitoring by woman’s own physician and complete followup for pregnancy outcome

Exposure: drug consumed at least in first trimester

N bupropion at least during 1st trimester N=136

|

Controls: A nonteratogenic group, representing women who had contacted the Motherisk program, but were not exposed to any teratogens during pregnancy, N non teratogen (NTD)=133

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: 4 months and 1 year after delivery.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%): N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available): No definition of spontaneous abortion

Spontaneous abortion Bupropion: 20 (14.7%) NTD: 6 (4.5%) p.009 |

Author’s conclusion: The higher rates of spontaneous abortions are similar to other studies examining the safety of antidepressants during pregnancy.

Bupropion use included when used for stop smoking 2 of 20 women had 3 or more spontaneous abortions before this pregnancy |

|

Einarson 2001

USA |

Type of study: register based prospective cohort study

Setting and country: The Motherisk Program and other participating pregnancy counseling centers; Brazil, Canada, Italy, UK, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: N/A |

Inclusion criteria: pregnant women, in 1st trimester, who had called The Motherrisk Service about safety of venlafaxine. Period of data collection: unknown

Exclusion criteria: unclear

Mean age ± SD: unknown

Potential confounders or effect modifiers: Age, smoking status, alcohol, |

Describe intervention: Structured questionnaire

Exposure: drug was consumed between the fourth and 14th week of gestation

N venlafaxine=150

|

Controls 2. Women receiving non-teratogenic drugs, N=150

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: between 6 and 12 months after delivery

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%): N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available): Outcomes were confirmed by sending a letter to the child’s primary care physician to corroborate the mother’s information

spontaneous abortion venlafaxine N=18(12.0%) Nonteratogenic drugs N=11(7.3%) NS |

|

|

Lupatelli 2014

Norway |

Type of study: population-based prospective cohort study

Setting and country: Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa) and the Medical Birth Registry of Norway (MBRN), Norway

Funding and conflicts of interest: supported by the Norwegian Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Education and Research and the Norwegian Research Council The authors declare no conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: pregnant women who had both a record in MBRN and had answered MoBa, recruited through postal invitation in connection with routine ultrasound at 17 to 18 weeks of gestation, delivery 1999-2006

Exclusion criteria: multiple pregnancies, users of unspecified medication for depression, users of SSRIs/SNRIs together with TCAs/OADs

Potential confounders or effect modifiers: Maternal age, parity, marital status, educational level, prepregnancy BMI, smoking during pregnancy, history of abortions, congenital heart defects, placenta previa, abruption placentae, history of obstetric bleeding, comedications, degree of underlying maternal depression during pregnancy |

Describe intervention:

Questionnaire: exposure by gestation age, medication: TCAs (ATC code N06AA), and OADs (ATC codes N06AX03, N06AX06, N06AX11, N06AX12, N06AX18)

information retrieved from self-administered questionnaires in pregnancy week30 to childbirth

N TCA = 12 |

nonexposed group: no reported use of antidepressants during pregnancy and no presence of depressive symptoms at gestational weeks 30-childbirthN nonexposed = 55862

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: 6 months after delivery

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%): N/A Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available): Postpartum haemorrhage: blood > 500 mL, collected from MBRN records, medically confirmed information.

Postpartum haemorrhage TCA Any type of delivery N=4 in exposed; N=8009 in unexposed aOR: 3.75 (1.09-12.94)

Caesarean section N=2in exposed, N=2515 in unexposed aOR: -

Vaginal delivery N=2(in exposed; N=5494 in unexposed aOR: -

|

Author’s conclusion: Among this Norwegian cohort of pregnant women, use of antidepressants in pregnancy was not associated with any obstetrical bleeding outcome.

- Women could participate in the MoBa for more than 1 pregnancy, with each of them being counted as individual mother child pair - reporting bias? - MoBa has low response rate (43%) with possible self selection - information antidepressants and bleeding are self-reported, - lost to followup unclear

|

|

Nakhai-Pour 2010

Canada |

Type of study: nested case control study

Setting and country: data from Quebec Pregnancy Registry (comprised of linkage RAMQ, the Med-Echo database and the Institut de la statistique du Québec database, Canada

Funding and conflicts of interest: Anick Bérard was consultant for a plaintiff in the litIgation involving Paxil. |

Inclusion criteria: women entered in Registry Jan. 1, 1998,-Dec. 31, 2003, age 15-45y, covered under RAMQ drug plan ≥ 12 months before first day of gestation. Only clinically detected spontaneous abortions 1st day - 20th wk

Exclusion criteria: women who had a planned abortion. If > 1 pregnancy during study period, only 1st pregnancy included.

N cases=5124 N control=51240

Mean age ± SD: Cases 28.7 ±(6.6) Controls 27.4 ±(5.7) Less depression / anxiety / bipolar disorder in control group

Potential confounders or effect modifiers: confounders: SES, comorbidities, history of abortion, visits to psychiatrists, number of prescribers, number of visits to physicians, exposure to medications in year before and during pregnancy, number of prenatal visits, |

Describe intervention Single antidepressant exposure: filling of a prescription for at least one dose of only one antidepressant from the first day of gestation to the date of spontaneous abortion

Other antidepressant: serotonin modulators, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tetracyclic piperazino-azepines, and dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

N TCA = 36 N SNRI = 33 N other = 18 |

Controls 1:10 matched by date of spontaneous abortion and gestational age at time of spontaneous abortion

N = 4840 |

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: N/A

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%): N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available): Spontaneous abortion: diagnosis or procedure for spontaneous abortion 1st day GA and 20th week GA Spontaneous abortion TCA only N=36 in exposed; N=4840 in unexposed aOR: 1.27 (0.85–1.91)

SNRI only N=33 in exposed; N=4840 in unexposed aOR: 2.11 (1.34–3.30)

Other only N=18 in exposed, N=4840 in unexposed aOR: 1.53 (0.86–2.72)

Venlafaxine alone N=33 in exposed; N=4840 in unexposed aOR: 2.11 (1.34–3.30)

Risk of spontaneous abortion and dose of venlafaxine (n cases/n total) Venlafaxine 33/161 1–150 mg/d: 29(18.9%)/153 > 150 mg/d: 4(50%)/8 p <0.05 |

Author’s conclusion: The use of venlafaxine during pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of spontaneous abortion

|

|

Palmsten 2012

USA |

Type of study: population based cohort study

Setting and country: population-based health-care utilization databases from British Columbia (1997–2006), linked to PharmaNet database (non-hospital pharmacy dispensings), USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: funded by NICHD, National Institutes of Health and the AHRQ. The pharmacoepidemiology Program receives funding from various pharmaceutical companies. |

Inclusion criteria: pregnancies ending in livebirth, Oct 1997-Jan 2006, continuous health-care enrollment from > year prior to last menstrual period - 2 months after delivery, at least 1 inpatient or outpatient Depression code 1 year prior to last menstrual period - 20 completed gestational weeks (depression code: ICD-9 codes 296.x, 300.x, 309.x, 311.x; ICD-10 codes F30.x–F39.x and F40.x–F48.x; or as a British Columbia-specific outpatient code, ‘‘anxiety/de pression.

Exclusion criteria:N/A

Median age (IQR): SNRI: 30 (7) TCA: 33 (8) Controls: 30 (8)

Potential confounders or effect modifiers: established risk factors for preeclampsia and factors related to depression severity

|

Describe intervention:

Depression: Antidepressant exposure: ≥ 1 pharmacy dispensing during estimated gestational weeks 10–20

Monotherapy: only 1 antidepressant class during pregnancy N SNRI=408 N TCA=146

continuers: dispensing between weeks 10 and 24. N SNRI 361 N TCA 100 |

no antidepressant use: no dispensings between the year prior to the last menstrual period and gestational week 20 N =65391

discontinuers: no antidepressant dispensing between gestational weeks 10 and 24 N SNRI 518 N TCA 412

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: N/A

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%): N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available): Pre-eclampsia: hypertension and proteinuria occurring after the 20th week of gestation. ICD-9 codes: 642.4x, 642.5x, 642.6x, or 642.7x; or ICD-10 codes: O11.x, O14.x, or O15.x between week 20 and 1 month after delivery

Pre-eclampsia Untreated depression versus SNRI aRR: 1.95 (95%CI: 1.25, 3.03)

Untreated depression versus TCA aRR: 3.23 (95% CI: 1.87, 5.59)

Discontinuing versus continuing SNRI aRR: 3.43 (95% CI: 1.77, 6.65)

Discontinuing versus continuing TCA aRR: 3.26 (95% CI: 1.04, 10.24) |

Author’s conclusion: Study results suggest that women who use antidepressants during pregnancy, especially SNRIs and TCAs, have an elevated risk of preeclampsia. These associations may reflect drug effects or more severe depression. The risk for preeclampsia appeared to be higher in antidepressant continuers than in discontinuers

|

|

Palmsten 2013a

USA |

Type of study: registration based cohort study

Setting and country: 2000-2007 nationwide Medicaid data, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: N/A |

Inclusion criteria: pregnant women aged 12-55 with a diagnosis of mood or anxiety disorder, Medicaid enrollment and meet eligibility criteria (no private insurance, no restricted benefits, appropriate type of enrollment from 5 months before delivery until after delivery), ICD-9 code 296.x, 300.x, 309.x, or 311.x between 1-5 months before delivery

Exclusion criteria: women who were exposed to both drugs types during 5 months before delivery

n=106000

Median age (IQR) Current: 26 (22-31) Recent: 25 (21-29) Past: 24 (21-28) no exposure: 23 (20-27)

Potential confounders or effect modifiers: risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage; proxies of mood/anxiety disorder severity; other indications for antidepressants; use of other psychotropic drugs; other drugs associated with risk of bleeding; proxies of comorbidity; potential mediators of postpartum hemorrhage |

Describe intervention: Women categorized into mutually exclusive exposure groups according to pharmacy dispensing data: Current: at delivery Recent: at least 1 day in 1-30 days before delivery Past: (1-5months before delivery

SNRI - current N=1495 - recent (N=829 - past N=2132

|

controls: women ICD-9 code for depressive of anxiety disorder 1-5 months for delivery, unexposed to medication N=69044

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: N/A

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%): N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available): Postpartum haemorrhage: ICD-9 666.x during admission to hospital for delivery, or within three days after delivery for outpatient deliveries

postpartum haemorrhage

SNRI - SNRI Current exposed N=56;unexposed: N=1495 aRR 1.39 (1.07 to 1.81) - SNRI Recent exposed N=26; unexposed N=829 aRR (95% CI) 1.17 (0.80 to 1.70) - SNRI Past exposed N=73; unexposed N=2132 aRR (95% CI) 1.26 (1.00 to 1.59)

Venlafaxine - Current exposed N= 46; unexposed N=763 aRR (95% CI) 2.24 (1.69 to 2.97) - Recent exposed N= -; unexposed N=237 - Past exposed N=12; unexposed N=458 aRR 0.98 (95% CI) (0.56 to 1.70)

Bupropion - Current exposed N=42; unexposed N=1162 aRR (95% CI) 1.32 (0.98 to 1.79) - Recent exposed N= 21; unexposed N=660 aRR (95% CI) 1.17 (0.77 to 1.79) - Past exposed N= 1712; unexposed N= 61 aRR (95% CI) 1.32 (1.02 to 1.69) |

Author’s conclusion: Exposure to SNRI’s, and tricyclics, close to the time of delivery was associated with an increased risk for postpartum haemorrhage

- in case groep more use of benzodiazepines and anticonvulsives

|

|

Palmsten 2013b

USA |

Type of study: population based cohort study

Setting and country: Medicaid enrollment information linked to inpatient and outpatient procedures and diagnoses, and to outpatient pharmacy-dispensing data, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: The Pharmacoepidemiology Program at the Harvard School of Public Health receives funding from Pfizer and Asisa. Sonia Hernández-Díaz has consulted for GSK and Novartis |

Inclusion criteria: pregnant women with depression diagnosis, 2000-2007

Exclusion criteria: women who did not meet Medicaid enrollment and eligibility criteria from one month before LMP month until the month after the delivery month. women who received antidepressants only during 1st trim but not during the exposure window

Median age (IQR): Unexposed 23 (8) SNRI 26 (9) TCA 26 (10) Bupropion 25 (8) Other 26 (10)

Potential confounders or effect modifiers: adjusted for delivery year, preeclampsia risk factors, depression severity proxies, other antidepressant indications, other medications, and healthcare utilization

|

Describe intervention:

Depression: inpatient or outpatient ICD-9 code 296.x, 300.x, 309.x, 311.x between LMP and 225 gestational days

exposure window: 90-225 gestational days, i.e. 2nd trim through end of 1st half of 3rd trim

exposed: antidepressant dispensed during the exposure window

unexposed: no antidepressant dispensed between the LMP and the end of exposure window

monotherapy: only 1 antidepressant class during exposure window

SNRI N=1,216 TCA N=441 Bupropion N=2,622 Other N=647 Venalfaxine N=1,113 Amitriptyline N= 271 Trazodone N=339 Mirtazapine N=253

|

Controls: depressed women not using antidepressants N=59.219

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: 1 month after delivery

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%): N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available): Pre-eclampsia: inpatient or outpatient ICD-9 code 642.4x–642.7x after 140 gestational days and within 30 days after the delivery date

Pre-eclampsia (exposed versus non-exposed) SNRI N=107 aRR: 1.52 (1.26–1.83)

TCA N=47 aRR: 1.62 (1.23–2.12)

Bupropion n=153 aRR:1.06 (0.91–1.25)

Other N=29 aRR: 0.71 (0.50–1.00) (mirtazapine, nefazodone, trazodone)

Venlafaxine N=100 aRR: 1.57 (1.29–1.91)

Amitriptyline N=31 aRR: 172 (1.24–2.40)

Trazodone N=14aRR: 0.63 (0.38–1.05)

Mirtazapine N=14 aRR: 0.81 (0.50–1.34) |

Author’s conclusion: In this population, SNRIs and tricyclics were associated with a higher risk of preeclampsia than SSRIs

|

|

Richardson 2019

UK |

Type of study: population based prospective observational comparative cohort

Setting and country: teratogen surveillance data collected by the UK Teratology Information Service (UKTIS), UK

Funding and conflicts of interest: funded by Public Health England, Newcastle University’s NCL. No conflict of interest |

Inclusion criteria: non-duplicate pregnancy outcomes, pregnancies in which mothers had used venlafaxine at any stage of pregnancy, collected by UKTIS following reports of maternal exposures Sept 1995- Aug 2018

Exclusion criteria: pregnancies where maternal age was unavailable, multiple pregnancies, maternal poisonings, overdoses or exposure to known or suspected human teratogens was reported

Median age (IQR): VF: 31 (28-35) Unexposed: 31 (28-35)

Potential confounders or effect modifiers: - matching ratio 5:1 to pregnancies unexposed to any antidepressant medications - disease-matched comparator group, consisting of matched SSRI antidepressant exposed pregnancies (matching ratio 3:1) |

Describe interventionNTD: Use of venlafaxine at any stage of pregnancy

N Venlafaxine=281

|

pregnant women; SNRI unexposed, non-depressed, use of non-teratogenic drugs, matched by calendar year and maternal age at UKTIS referral

N unexposed=1405

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: N/A

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%): N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available): Crude spontaneous abortion rates were calculated for pregnancies reported to UKTIS prior to 24 weeks which did not result in elective termination

intrauterine fetal death/still birth: pregnancies endiing in elective termination of spontaneous abortion ≥ 24wk GA

Spontaneous abortion: Venlafaxine: 46 (21%) Unexposed: 140 (14.5%) OR (95%CI): 1.57 (1.06 - 2.30)

Intrauterine fetal death/stillbirth Venlafaxine: 3 (1.4%) Unexposed: 12 (1.03%) OR (95%CI): 1.36 (0.245 to 5.11) |

Author’s conclusion: Comparisons between the venlafaxine-exposed and the antidepressant unexposed group identified a statistically significant increased crude rate of spontaneous abortion, but this was not observed in comparison with a disease-matched control group of SSRI exposed pregnancies.

|

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (observational: non-randomized clinical trials, cohort and case-control studies)

Research question: What is the risk of pregnancy and labor complications in women with psychiatric disorders taking non-SSRI-antidepressants during pregnancy, compared with healthy women and women with psychiatric disorders not taking antidepressants or taking a different class antidepressant or a differtent non-SSRI antidepressant?

|

Study reference

(first author, year of publication) |

Bias due to a non-representative or ill-defined sample of patients?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to insufficiently long, or incomplete follow-up, or differences in follow-up between treatment groups?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to ill-defined or inadequately measured outcome ?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate adjustment for all important prognostic factors?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Avalos 2015 |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

Chun-Fai-Chan 2005 |

Unclear |

Likely |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

Einarson 2001 |

Likely |

Likely |

Likely |

Unclear |

|

Lupattelli 2014 |

Unclear |

Likely |

Likely |

Unclear |

|

Nakhai-Pour 2010 |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Palmsten 2012 |

Unlikely |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Palmsten 2013a |

Likely |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

unlikely |

|

Palmsten 2013b |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Richardson 2019 |

Likely |

Likely |

Unlikely |

Likely |

- Failure to develop and apply appropriate eligibility criteria: a) case-control study: under- or over-matching in case-control studies; b) cohort study: selection of exposed and unexposed from different populations.

- Bias is likely if: the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large; or differs between treatment groups; or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups; or length of follow-up differs between treatment groups or is too short. The risk of bias is unclear if: the number of patients lost to follow-up; or the reasons why, are not reported.

- Flawed measurement, or differences in measurement of outcome in treatment and control group; bias may also result from a lack of blinding of those assessing outcomes (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Failure to adequately measure all known prognostic factors and/or failure to adequately adjust for these factors in multivariate statistical analysis.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Broy, 2010 |

narrative review |

|

Bruning,2015 |

No subgroups of antidepressants defined |

|

Heller, 2017 |

No subgroups of antidepressants defined |

|

Huang, 2014 |

Wrong outcome measure |

|

Huybrechts, 2014 |

Wrong outcome measure |

|

Jiang, 2016 |

No subgroups of antidepressants defined |

|

Kjaersgaard, 2013 |

No subgroups of antidepressants defined |

|

Lennestal, 2007 |

Wrong outcome measure |

|

Misri, 1991 |

No control group |

|

Mitchell, 2018 |

Wrong outcome measure |

|

Newport, 2016 |

No control group |

|

Pearson, 2007 |

No subgroups of antidepressants defined |

|

Perrotta, 2019 |

numbers too small |

|

Ramos, 2010 |

Wrong outcome measure |

|

Reis, 2010 |

No subgroups of antidepressants defined |

|

Ross, 2013 |

SSRI |

|

Simon, 2002 |

Wrong outcome measure |

|

Toh, 2009 |

Wrong outcome measure |

|

Youash, 2019 |

narrative review |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 23-07-2021

Bij het opstellen van de modules heeft de werkgroep een inschatting gemaakt over de maximale termijn waarop herbeoordeling moet plaatsvinden. De geldigheid van de richtlijnmodules komt eerder te vervallen indien nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding zijn een herzieningstraject te starten.

|

Module1 |

Regiehouder (s)i |

Jaar van autorisatie |

Eerstvolgende beoordeling actualiteit richtlijn2 |

Frequentie van beoordeling op actualiteit3 |

Wie houdt er toezicht op actualiteit4 |

Relevante factoren voor wijzigingen in aanbeveling5 |

|

Niet-SSRI antidepressiva en zwangerschaps- en baringscomplicaties |

NVOG |

2021 |

2026 |

Eens in vijf jaar |

NVOG |

Nieuw onderzoek |

1 Naam van de module

i Regiehouder van de module (deze kan verschillen per module en kan ook verdeeld zijn over meerdere regiehouders)

2 Maximaal na vijf jaar

3 (Half)Jaarlijks, eens in twee jaar, eens in vijf jaar

4 Regievoerende vereniging, gedeelde regievoerende verenigingen, of (multidisciplinaire) werkgroep die in stand blijft

5Lopend onderzoek, wijzigingen in vergoeding/organisatie, beschikbaarheid nieuwe middelen

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling van deze richtlijn werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodules.

De richtlijn is ontwikkeld in samenwerking met:

- Patiëntenfederatie Nederland

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijn is in 2018 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor zwangere patiënten die ‘niet-SSRI’ antidepressiva en/of antipsychotica gebruiken. De werkgroepleden zijn door hun beroepsverenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname. De werkgroep is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze richtlijn.

Werkgroep

- Dr. A. Coumans, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht, NVOG

- Dr. H.H. Bijma, gynaecoloog, Erasmus Medisch Centrum, Rotterdam, NVOG

- Drs. R.C. Dullemond, gynaecoloog, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, Den Bosch, NVOG

- Drs. S. Meijer, gynaecoloog, Gelre Ziekenhuis, Apeldoorn, NVOG

- Dr. M.G. van Pampus, gynaecoloog, OLVG, Amsterdam, NVOG

- Drs. M.E.N. van den Heuvel, neonatoloog, OLVG Amsterdam, NVK

- Drs. E.G.J. Rijntjes-Jacobs, neonatoloog, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum, Leiden, NVK

- Dr. K.M. Burgerhout, psychiater, Amphia Ziekenhuis, Breda, NVvP

- Dr. E.M. Knijff, psychiater, Erasmus Medisch Centrum, Rotterdam, NVvP

Meelezers

- Dr. A.J. Risselada, klinisch farmacoloog, Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis Assen

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. E. van Dorp-Baranova, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. M. Moret-Hartman, senior-adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- N. Verheijen, senior-adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- M. Wessels, literatuurspecialist, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Dr. A. Coumans |

gynaecoloog-perinatoloog Maastricht UMC+ |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Dr. H. H. Bijma |

Gynaecoloog, Erasmus MC, afdeling verloskunde en gynaecologie, subafdeling verloskunde en prenatale geneeskunde |

lid werkgroep wetenschap LKPZ, onbetaald |

geen |

geen |

|

Drs. S. Meijer |

gynaecoloog Gelre Ziekenhuis, Apeldoorn |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Drs. R. C. Dullemond |

gynaecoloog- perinatoloog, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis |

LKPZ bestuur - voorzitter, onbetaald mind 2 care - raad van toezicht, onbetaald dagelijks bestuur @verlosdenbosch (integrale geboortezorg organisatie) als gynaecoloog uit het JBZ, onbetaald danwel deels in werktijd |

geen |

geen |

|

Drs. E. G. J. Rijntjes-Jacobs |

kinderarts-neonatoloog, afdeling neonatologie, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum |

LKPZ bestuur – secretaris, onbetaald |

geen |

geen |

|

Dr. M. G. van Pampus |

Gynaecoloog, OLVG Amsterdam |

onbetaalde nevenfuncties |

geen |

geen |

|

Dr. E. M. Knijff |

Psychiater, Erasmus MC polikliniek psychiatrie & zwangerschap medisch coördinator polikliniek Erasmus MC |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Drs. M. E. N. van den Heuvel |

kinderarts-neonatoloog, OLVG Amsterdam |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Dr. K. Burgerhout |

Psychiater, Reinier van Arkel, POP-poli |

geen |

geen |

geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er is een aantal acties uitgevoerd om het patiëntperspectief mee te nemen bij het ontwikkelen van deze richtlijn. Allereerst is contact gezocht met het MIND Platform voor afvaardiging van een patiëntvertegenwoordiger in de werkgroep. Zij hebben ons in contact gebracht met de Stichting Me Mam. Het bleek niet mogelijk een patiëntvertegenwoordiger voor de werkgroep te vinden. Daarna is een focusgroepbijeenkomst voor patiënten georganiseerd, maar deze is geannuleerd vanwege onvoldoende aanmeldingen. Tot slot is een schriftelijke enquête voor patiënten in samenwerking met de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland opgesteld en uitgezet. Dit heeft helaas nauwelijks reactie opgeleverd, de enquête is door twee patiënten ingevuld. Voor de ontwikkeling van het product voor patiënten (informatie op de website www.Thuisarts.nl) is een ervaringsdeskundige van de patiëntenvereniging ‘Plusminus-leven met bipolariteit’ afgevaardigd. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en het MIND Platform.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

In de verschillende fasen van de richtlijnontwikkeling is rekening gehouden met de implementatie van de richtlijnmodules en de praktische uitvoerbaarheid van de aanbevelingen. Daarbij is uitdrukkelijk gelet op factoren die de invoering van de richtlijn in de praktijk kunnen bevorderen of belemmeren. Het implementatieplan is te vinden in de bijlagen.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijn is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor vrouwen die antipsychotica of niet-SSRI antidepressiva tijdens zwangerschap en lactatie gebruiken. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door IGJ, NHG, V&VN, Zorginstituut Nederland, Lareb, KNOV, NVvP, NVOG en NVK via een Invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen in de bijlagen. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |