Antidepressiva (niet-SSRI's) en langetermijneffecten bij het kind

Uitgangsvraag

Welke niet-SSRI antidepressiva hebben de voorkeur voor gebruik in de zwangerschap met betrekking tot het risico op late gevolgen op motoriek, cognitie, gedrag en sociaal emotionele ontwikkeling bij het kind? Welke effecten zijn er op het gebied van de groei, de spraak-/taalontwikkeling, de visus en het gehoor?

Aanbeveling

Bespreek met patiënte dat er op basis van de huidige kennis over de langetermijneffecten van het gebruik van niet-SSRI antidepressiva tijdens de zwangerschap op het kind, geen voorkeur aangegeven kan worden voor een specifiek niet-SSRI antidepressivum.

Bespreek met patiënte dat er geen verhoogd risico lijkt te zijn op cognitieve, taal- en algemene gedragsproblemen bij kinderen die antenataal zijn blootgesteld aan niet-SSRI antidepressiva, maar dat onderzoek hiernaar beperkt is.

Bespreek met patiënte dat er geen verhoogd risico lijkt te zijn op het ontstaan van ADHD en van ASD bij het kind na gebruik van niet-SSRI antidepressiva (respectievelijk TCA’s/SNRI’s/andere niet-SSRI’s) tijdens de zwangerschap. De (ernst van de) psychiatrische ziekte van de moeder en mogelijke genetische factoren spelen hier een belangrijke rol in.

Bespreek met patiënte dat op basis van de huidige kennis over de langetermijneffecten van het gebruik van niet-SSRI antidepressiva tijdens de zwangerschap op het kind, het niet noodzakelijk is de medicatie te stoppen of te wijzigen tijdens de zwangerschap.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Recente studies over de lange termijneffecten van foetale blootstelling aan antidepressiva in de vorm van een niet-SSRI laten een klein maar niet statistisch significant verhoogd risico zien op de ontwikkeling van ADHD bij het kind. Zowel bij TCA’s, SNRI’s als andere niet-SSRI’s wordt dit gevonden. Tegelijkertijd is het risico op ADHD echter vergelijkbaar verhoogd in kinderen van moeders die alleen pre-conceptioneel deze antidepressiva gebruikten en kinderen van moeders met een psychiatrische aandoening die geen antidepressiva hadden gebruikt. Daarnaast laten gematchte sibling-analyses geen verschillen zien in het risico op ADHD in aan niet-SSRI antidepressiva blootgestelde en niet-blootgestelde broertjes en zusjes.

Vergelijkbaar met ADHD laten kinderen die antenataal zijn blootgesteld aan niet-SSRI antidepressiva, en specifiek ook TCA’s, een verhoogd risico zien op autisme spectrum stoornissen (ASD). Ook hier wordt het verhoogde risico op ASD echter mede gezien bij kinderen van moeders met een depressie die niet behandeld werden tijdens de zwangerschap en zijn er geen verschillen in de gematchte sibling case-controle studies.

Ondanks de correctie voor veel bekende confounders in deze studies, is het onduidelijk of het risico op ADHD en ASD na gebruik van niet-SSRI antidepressiva daadwerkelijk verhoogd is. Het is aannemelijk dat in ieder geval een deel van de verklaring van de associatie tussen beiden gezocht moet worden in andere confounders waarvoor moeilijker gecorrigeerd kan worden, zoals de ernst van de maternale psychiatrische (co)-morbiditeit, de sociale omstandigheden waarin het kind opgroeit en een eventuele genetische component. Deze factoren zijn bekende risicofactoren voor het ontstaan van ADHD en ASD. Verder wordt in geen van de studies vermeld of deze moeders postnataal borstvoeding gaven, wat als gevolg van de langere blootstelling aan het geneesmiddel de relatie tussen antenatale blootstelling aan een niet-SSRI antidepressivum en de lange termijneffecten verder bemoeilijkt. Bovenstaande lange termijneffecten van antenataal aan antidepressiva blootgestelde neonaten in de literatuur komen voort uit grote internationale registerstudies. De voordelen van deze databases zijn de grote aantallen patiënten, de relatief lange follow-up periode in de kindertijd, de gestandaardiseerde en vaak prospectieve manier van gegevens verzamelen en de mogelijkheid om patiënten te matchen aan controle-patiënten. De nadelen zijn echter dat alleen klinisch gediagnosticeerde ziektebeelden in de database worden geïncludeerd en dat gegevens over voorgeschreven medicatie in een geneesmiddelenregister niets zeggen over het daadwerkelijk gebruik van de medicatie. Dit geeft een risico van misclassificatie, ontbrekende gegevens en zowel onder- als overschatting van de resultaten. Daarnaast is het zeer moeilijk om te corrigeren voor alle potentieel relevante confounders.

Overige studies die gekeken hebben naar de cognitieve en neuromotore ontwikkeling, taalontwikkeling en het gedrag laten vooralsnog geen duidelijke negatieve effecten zien op het kind na blootstelling aan niet-SSRI antidepressiva. Deze studies zijn echter, ondanks de veelal goed gevalideerde ontwikkelingstesten, mogelijk minder valide, gezien de relatief kleine patiënten-aantallen, de relatief korte duur van follow-up (leeftijd van 15 maanden tot bijna 7 jaar) en de uitvoer van de studies (veel vormen van bias).

Concluderend is er op dit moment onvoldoende goede informatie uit de literatuur beschikbaar over de lange termijneffecten op de cognitieve, neuromotore, taal- en gedragsmatige ontwikkeling van kinderen die intra-uterien zijn blootgesteld aan antidepressiva anders dan SSRI’s. Er worden in meerdere grote studies wisselend risico’s op ADHD en ASD beschreven bij kinderen van met niet-SSRI antidepressiva behandelde moeders. Deze risico’s zijn mogelijk kleiner dan tot nu toe is beschreven, gezien de relatie met andere confounders die in ieder geval deels verklarend zouden kunnen zijn voor de associatie van de antidepressiva met deze ziektebeelden.

Van belang is dat de groep van antidepressiva anders dan SSRI’s een hele heterogene groep medicamenten is. Vrijwel alle studies geven resultaten over combinaties van (groepen van) medicamenten, die qua farmacokinetiek en farmacodynamiek vaak niet vergelijkbaar zijn. Dit maakt dat uitspraken over individuele medicamenten niet of nauwelijks te geven zijn.

Overige geraadpleegde bronnen

Behoudens de hier beschreven literatuur, zijn er geen andere (buitenlandse) richtlijnen of beschouwende artikelen, die een uitspraak doen over de lange termijneffecten bij antenataal aan antidepressiva (niet-SSRI’s) blootgestelde neonaten. Ook het Handboek Psychiatrie en Zwangerschap geeft geen aanvullende informatie. Het is wel relevant te vermelden dat de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie in de algemene richtlijn “Depressie”, voor de eerste lijn SSRI’s of TCA’s adviseert als eerste keuze-middel, met een lichte voorkeur voor een SSRI gezien de grotere ervaring met deze medicatiegroep en de wat lagere kans op bijwerkingen (Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie, 2013). Er wordt geen specifiek medicatie-advies gegeven voor vrouwen in de fertiele fase of tijdens de zwangerschap.

Farmacologische overwegingen

Uit de literatuur is geen informatie naar voren gekomen over de relatie tussen de farmacokinetiek, trans-placentaire passage en lange termijneffecten van niet-SSRI’s op de ontwikkeling van het kind.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

Er is geen literatuur ten aanzien van waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten met betrekking tot de lange termijneffecten op de ontwikkeling van het kind, die een rol spelen rondom de besluitvorming om niet-SSRI antidepressiva te stoppen, starten of te continueren tijdens de zwangerschap. Samen met de (aanstaande) moeder die een niet-SSRI antidepressivum gebruikt en haar partner zullen, bij voorkeur pre-conceptioneel, de voor-en nadelen van het gebruik van het geneesmiddel tijdens zwangerschap en lactatie moeten worden afgewogen, tegen haar ziektebeeld en het ziekteproces, psychosociale factoren, de mogelijkheid van het stoppen dan wel omzetten naar een ander medicament en de veiligheid voor moeder en het (toekomstig) kind. Het uitgangspunt zou moeten zijn het realiseren van maximale psychische stabiliteit van moeder in combinatie met maximale veiligheid voor het kind.

Kosten

Kosteneffectiviteitsstudies zijn niet meegenomen bij de literatuursearch voor deze module. Bij het in stand houden van stabiliteit voor moeder en kind zal er echter naar verwachting, minder aanspraak gemaakt hoeven te worden op (crisis)zorg bij de GGZ en lange termijn (poli)klinische begeleiding/behandeling van het kind.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Het is van belang om multidisciplinaire zorg voor alle kwetsbare zwangeren, ook die antidepressiva gebruiken, te implementeren in de geboortezorgketen.

Hiervoor is expertise en informatie-uitwisseling noodzakelijk. Voorbeelden hiervan zijn POP-poliklinieken en/of een MDO psychiatrie.

Op deze manier zullen alle betrokkenen (GGZ zorgverlener (psychiater, psycholoog, verpleegkundig specialist, sociaal-psychiatrisch verpleegkundige (SPV), physician assistant (PA)), kraamverzorgster, maatschappelijke werker, medewerkers van jeugdgezondheidszorg (CB/CJG) en kinderarts) tijdig geïnformeerd zijn over de afwegingen voor de individuele zwangere om een antidepressivum wel of niet te continueren en de mogelijke lange termijneffecten ervan op het kind. De werkgroep verwacht binnen het kader van deze multidisciplinaire zorg geen problemen met de implementatie van deze aanbevelingen.

Idealiter zou je in verband met de mogelijke lange-termijn effecten deze kinderen gedurende de schooltijd en adolescentie willen vervolgen, maar daar zijn in de praktijk in veel gevallen niet de financiële of logistieke middelen voor.

Rationale/ balans tussen de argumenten voor en tegen de interventie

Op basis van de momenteel voorhanden zijnde gegevens over de lange termijneffecten van antenataal gebruikte niet-SSRI antidepressiva (TCA’s/SNRI’s/andere niet SSRI’s) op het kind, geldt dat de deels nog onbekende, maar vooralsnog lage risico’s op ontwikkelings-/taal- en algemene gedragsproblemen afgewogen dient te worden tegen de noodzaak van het gebruik tijdens de zwangerschap. Hetzelfde geldt voor de mogelijk verhoogde risico’s op ADHD en ASD, aangezien deze risico’s mogelijk deels te verklaren zijn door het psychiatrisch ziektebeeld van moeder, genetische en omgevingsfactoren. Het (abrupt) stoppen van antidepressiva tijdens de zwangerschap kan leiden tot een ernstige verslechtering van de psychische conditie van moeder, wat onafhankelijk van de medicatie de cognitieve, gedragsmatige en emotionele ontwikkeling van het kind negatief kan beïnvloeden. Deze negatieve gevolgen kunnen persisteren tot in de late adolescentie (Stein, 2014).

Dit laat onverlet dat een maximale inzet van niet-medicamenteuze interventies en de voorkeuren van de (toekomstige) zwangere meegenomen dienen te worden, waarbij gestreefd wordt naar een zo laag mogelijke effectieve dosis van het medicament in monotherapie, en hetzelfde medicament tijdens de peri-conceptionele periode, de zwangerschap, de kraamtijd en het eerste jaar postpartum. Aangezien er geen specifieke aanbevelingen te geven zijn ten aanzien van welk antidepressivum van de binnen de niet-SSRI groep verschillende groepen medicamenten de voorkeur heeft, zal de keuze van het medicament met name afhankelijk zijn van de eventuele risico’s op zwangerschaps-/baringscomplicaties, congenitale afwijkingen, neonatale effecten en de mogelijkheid om borstvoeding te geven.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Bij het afwegen van de voor- en nadelen van het voorschrijven van niet-SSRI antidepressiva in de zwangerschap en tijdens lactatie, is naast kennis over de risico’s op korte termijn ook kennis noodzakelijk over de langetermijneffecten op het kind van prenatale blootstelling aan niet-SSRI antidepressiva. In deze module wordt specifiek aandacht besteed aan de ontwikkeling van het kind in brede zin (motoriek, cognitie, gedrag en sociaal emotionele ontwikkeling).

Er is reeds een landelijke richtlijn voor het gebruik van SSRI’s ten tijde van zwangerschap en lactatie. Deze richtlijn is bedoeld voor het gebruik van SNRI’s, TCA’s en MAO-remmers.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

ADHD

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the risk of developing ADHD in children whose mothers used a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI), or other non-SSRI antidepressants during pregnancy, as compared to children whose mothers used no antidepressants during pregnancy.

Bronnen: (Boukhris, 2017; Laugesen, 2013; Man, 2017) |

Risk of autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about risk of developing autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in children whom mothers used a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) during pregnancy, as compared to children whose mothers neither had depression, nor prescriptions for antidepressants during pregnancy.

Bronnen: (Hagberg, 2018) |

Language development

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of the use of tricyclic antidepressants during pregnancy on children’s language development.

Bronnen: (Nulman, 2002; Simon, 2002) |

Behavior problems

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the risk of the development of behavioral problems in children whose mothers used venlafaxine during pregnancy as compared to children of nondepressed mothers.

Bronnen: (Nulman, 2012) |

IQ

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of the use of venlafaxine or tricyclic antidepressants during pregnancy on children’sIQ scores are comparable to children whose mothers were nondepressed or had an untreated depression.

Bronnen: (Nulman, 2002; Nulman, 2012) |

Mental and motor development

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of the use of tricyclic antidepressants during pregnancyon the mental and motor development of the children as comparede to children of women without psychiatric disorders or depressive symptoms and unexposed.

Bronnen: (Nulman, 2002; Simon, 2002) |

Growth, vision and hearing

|

- GRADE |

No conclusions could be drawn about the effect of non-SSRI antidepressant use during pregnancy on growth, vision and hearing of the children, compared to no use of non-SSRI antidepressants. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Three studies reported on the risk of ADHD in the offspring after the use of antidepressants during pregnancy (Boukhris, 2017; Laugesen, 2013; Man, 2017).

Boukhris (2017) reported the results of a Canadian, register-based cohort study using the Quebec Pregnancy/ Children Cohort (QPC), an ongoing population-based cohort; data collected prospectively for all pregnancies. The population included 144, 406 eligible full-term liveborn singletons, born between January 1998 and December 2009. The exposure to antidepressants was determined using the RAMQ Prescription Drug database. Exposure was defined as at least one prescription filled at any time during pregnancy or a prescription filled before pregnancy that overlapped the first day of gestation. The presence of ADHD was defined as children with a diagnosis of ADHD or at least one prescription filled for ADHD medications between birth and the end of follow-up. Antidepressant classes were: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic Ads (TCAs), monoamine-oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), and other antidepressants. The mean age at first ADHD diagnosis was 6.3 years (range 0 to 11 years).

Laugesen (2013) was a cohort study using the Danish Medical Birth Registry; 877,778 children, from cohort of all singletons born alive from 1996 to 2009. In utero exposure to antidepressants: prescription for an antidepressant 30 days prior to or during pregnancy, as identified through the Danish National Prescription Registry. Former users of antidepressants were women, who had redeemed a prescription up to 30 days prior to pregnancy. Finally, never users: women who had never redeemed a prescription. Risk of ADHD: prescription for ADHD medication or an ADHD hospital diagnosis Using the Danish Psychiatric Registry and the Danish National Registry of Patients. The median follow-up was 8 years.

Man (2017) was a population based cohort study, using the data from the Hong Kong population based electronic medical records on the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System (CDARS). A total of 190,618 children born in Hong Kong public hospitals between January 2001 and December 2009 were included. Both explosion (maternal antidepressant use) and outcome (ADHD) were extracted from the database (CDARS). ADHD was defined as ADHD diagnosis, registered as ICD-9-CM diagnosis or a prescription for an ADHD drug as recorded in CDARS. The mean follow-up time was 9.28 years (range 7.4 to 11.0 years).

Two studies reported on autism spectrum disorder in the offspring of women who took antidepressants during pregnancy (Hagberg, 2018; Liu, 2017).

Hagberg (2018) reported on a cohort study, using the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), a large, population-based electronic medical database. 40,387 mothers aged 13 to 44 years, and their live-born, singleton infants born between 1989 and 2011, were included. 12,994 women with untreated depression, 25,778 women had treated depression, and 1,615 received antidepressants for indications other than depression. These exposed mother–baby pairs were matched with 154,107 unexposed mother–baby pairs. Outcome was the risk of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in offspring: all children with at least one Read diagnostic code indicating ASD recorded at any time, including codes for autism, Asperger’s syndrome, and pervasive developmental disorder (PDD). The mean follow-up was 8.7 (interquartile range 4.9 to 11.5 years).

Liu (2017) reported on the risk of autism after exposure to antidepressants. The study was a population-based cohort study, using data from the Danish Civil Registration System, including all live births and residents in Denmark. Data from 905,383 liveborn singletons born during 1998 and 2012 were included. They analyzed the effect of antidepressant use within two years before and during pregnancy. Four groups were identified: unexposed, antidepressant discontinuation (use before but not during pregnancy), antidepressant continuation (use both before and during pregnancy), and new user (use only during pregnancy).

Nulman (1997) studied the children of 80 mothers who had received a tricyclic antidepressant drug during pregnancy, 55 children whose mothers had received fluoxetine during pregnancy, and 84 children whose mothers had not been exposed during pregnancy to any agent known to affect the fetus. Outcome measures were children's global IQ and language development were assessed between 16 and 86 months. The group of included women partially overlapped with the group of women included in a more recent study of Nulman: 18 fluoxetine and 36 TCA exposed women were also included in Nulman (2002).

Nulman (2002) used prospectively collected data in the Motherrisk Program, which provides information and consultation to women, their families, and health professionals on the risk/safety of drug, chemical, radiation, and infectious exposures during pregnancy and lactation. Three groups of mother-child pairs were identified:

- all women who had been counseled by the program regarding therapy with TCAs and continued taking throughout gestation, n=46;

- all women who had been counseled by the program regarding therapy with fluoxetine and continued taking throughout gestation, n=40;

- women who had no history of a psychiatric disorder or depressive symptoms (score less than 16 on CES-D) and were unexposed to any drug; chosen randomly from a list of women who had visited our clinic < 2 months before or after the visits by the study groups, n=36.

The authors assessed whether children had been exposed to tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) or fluoxetine throughout fetal life. Outcome measures were neurodevelopment of children: Cognitive Outcome of Children (Reynell Developmental Language Scales), mental and psychomotor development (Bayley Scales of Infant Development; children between 15 and 30 months of age), and cognitive development (global cognitive index from McCarthy; children older than 30 months). Outcome measures were assessed by a psychometrist blinded to intrauterine exposure. The follow up of children ranged from 15 to 71 months.

Nulman (2012) also used data prospectively collected data in the Motherrisk Program. Mothers with a depression were selected. Depressive episodes were defined according to DSM-IV criteria and diagnosed by the woman’s psychiatrist. Only depressed women receiving pharmacotherapy before or during pregnancy were included. As control group, women who called Motherisk to inquire about nonteratogenic exposure (for example acetaminophen) were included. In this article, they reported on the children’s’ IQ in relation to the exposure to venlafaxine, SSRI or untreated depression. IQ was measured with Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence. Furthermore, Behavioral profiles were included, using the Child Behavior Checklist and Conners’ Parent Rating Scale, completed by the mother. Multivariate analyses, however, only reported a result for ‘treatment group’. No results for venlafaxine versus untreated depression or non-depressed mothers were reported.

Simon (2002) reported the results of a cohort study, based on a sample drawn from Group Health Cooperative, a prepaid health plan serving in Washington State. all live births between January 1, 1986, and December 31, 1998. The sample was limited to:

- those enrolled at primary care facilities owned by Group Health Cooperative;

- mothers continuously enrolled in Group Health Cooperative for 360 days before delivery.

Pharmacy records were used to identify all antidepressant prescriptions filled or refilled during the 360 days before delivery (exposure to TCAs or SSRIs). Outcomes included motor delay and speech delay, measured using standardized physical examination records from pediatric health-monitoring (from birth to age 2) and the records of outpatient visits and hospital admissions. For the final diagnosis of speech or motor delay, both a physician diagnosis and confirmation by a formal developmental evaluation were necessary. Chart reviewers and investigators remained blind to exposure Status. Results had not been corrected for potential confounding variables.

Results

Risk of ADHD

Three studies reported on the risk of ADHD (Boukhris, 2017; Laugesen, 2013; Man, 2017).

Boukhris (2017) found 4,564 (3.2%) children with ADHD in a cohort of 144,406 fullterm liveborn children. 4,678 (3.2%) of the 144,406 children had been exposed to antidepressants (SSRIs, SNRIs, TCAs or other). Exposure to antidepressant during 2nd/3rd trimester of pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of ADHD (HR 1.3, 95% CI 1.0-1.6), even after adjusting for relevant potential confounders such as maternal ADHD, depression/anxiety, other maternal psychiatric disorders and relevant maternal sociodemographic characteristics. More specifically, tricyclic use was associated with an increased risk of ADHD (HR 1.8, 95% CI 1.0-3.1), while SNRI use was not.

Laugesen (2013) described 12,841 (1.5%) with ADHD in a cohort of 877,778 live born singletons. 15,008 (1.7%) of the 877,778 children had been exposed to antidepressants in utero (SSRIS, SNRIOs, TCAs or other). The adjusted HR comparing children exposed to any antidepressant in utero with children born to never users was 1.2 (95% CI 1.1 to 1.4). However, in a within-mother between pregnancy analysis (mothers who had more than one child and at least one exposed and one unexposed pregnancy), the adjusted OR was 0.7 (95% CI 0.4 to 1.4). There was a minor association between ADHD and exposure in utero to any kind of antidepressant in the first trimester (aHR 1.2 (1.0 to 1.4). Separate analyses according to type of antidepressant did not show a significant association between ADHD and antenatal exposure to SNRI’s, TCA’s or other antidepressants (other than SSRI’s).

Man (2017) found 5,659 (3%) children with ADHD in a population of 190,618 live born children. 1,252 (0.7%) of the children had a mother who used prenatal antidepressants. After adjustment for potential confounders, including maternal psychiatric disorders, the adjusted HR of maternal antidepressant use during pregnancy compared with non-use, was 1.39 (CI 1.07 to 1.82). Likewise, however, similar results were observed when comparing children of mothers who had used antidepressants before pregnancy with those who were never users (HR 1.76, CI 1.36 to 2.30). In addition, sibling matched analysis identified no significant difference in risk of ADHD in siblings exposed to antidepressants during gestation and those not exposed during gestation (HR 0.54, CI 0.17 to 1.74).

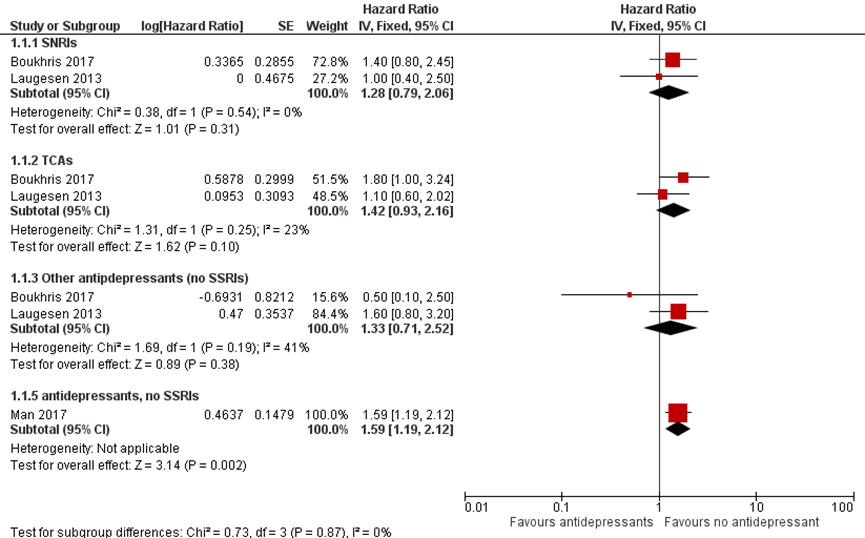

Children exposed to TCAs, SNRIs, and other non-SSRI antidepressants had a small but non-significant increased risk of ADHD compared to children who were not exposed to antidepressants. Boukhris (2017) and Laugesen (2013) reported their results for each subgroup of antidepressants (SNRIs, TCAs and other non-SSRI antidepressants. Man (2017) combined all these non-SSRI antidepressants. Therefore, the results of the study by Man (2017) are presented separately in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Forest plot Risk of ADHD related to exposure to antidepressants (non-SSRIs)

Risk of autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

In the study by Hagberg (2018) 2,154 children with ASD were identified among 194,494 mother–baby pairs (1,1%). 15,778 (8.1%) women had been treated with antidepressants during pregnancy for depression (SSRIs, SNRIs, TCAs or other antidepressants). Overall, the risk of ASD was increased in children of women who had been treated for their depression as compared to non-exposed children (RR 1.70, 95% CI 1.51 to 1.92). However, also in children of women with untreated depression the risk of ASD was increased (RR 1.49, 95%CI 1.27 to 1.75). The risk of ASD was increased in children whose mothers had used TCAs as compared to non-exposed children with a relative risk (RR) of 1.95 (95% CI 1.58 to 2.40) after correction for child sex, maternal BMI, smoking status, parity, anxiety, and other psychiatric disorders. No separate results were reported for SNRIs.

Risk of any psychiatric disorder

Liu (2017) reviewed the risk of any psychiatric disorder in children exposed to continuous antidepressant use in utero, compared with children of mothers who discontinued antidepressant use during pregnancy. For the use of non-SSRI monotherapy, Liu (2017) found no increased risk on psychiatric disorders in children (HR=1.15, 95%CI 0.96 to 1.40)

Behavioral problems

The results on behavior profiles in the study by Nulman (2012) were only plotted in figures. The authors concluded that children, whose mothers used venlafaxine, SSRIs or whose mothers were depressed had more clinically significant behavioral problems compared to children of nondepressed mothers. The proportion of children with a clinically significant score for internalizing problems (CBCL) for venlafaxine was approximately 0.015 lower as compared to SSRIs, and approximately 0.025 higher as compared to children from depressed untreated women.

Cognition and neurodevelopment

In the study by Nulman (2002), IQ was measured using the global cognitive index from McCarthy. The age of the children ranged from 15 to 71 months. The mean score in children whose mothers had taken fluoxetine during pregnancy was 108.7 (95%CI 87.8 to 129.5) and 117.8 (112.6 to 122.9) in children whose mothers had taken TCAs during pregnancy. The mean IQ score was 118.4 (113.6 to 123.3) in children of women without psychiatric disorder or depressive symptoms and unexposed. Multivariate analyses revealed that antidepressant drugs themselves did not predict cognitive achievements (β=19.88, 95%CI -8.12 to 47.88) (Nulman, 2002). In the multivariate analyses the results for fluoxetine and TCAs were combined.

In another study (Nulman, 2012), IQ was measured with the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence. Mean IQ scores (sd) were slightly higher in children whose mother was nondepressed (IQ=112, sd=11) or whose mother had untreated depression (IQ=108, sd=14) as compared to children whose mothers used venlafaxine (IQ=105, sd=14) or SSRIs (IQ=105, sd=13). The authors, however, concluded that group membership did not predict cognitive outcomes after controlling for other factors. The results of the multivariate analyses were not reported.

The neurodevelopment of the children (between 15 and 30 months of age) was also reported in the study by Nulman (2002). The mean scores for mental development of Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID) were 104.4 (95% CI 98.9 to 109.9) for children exposed to Fluoxetine, 110.9 (95% CI 104.0 to 118.0) for children exposed to TCAs, and 104.1 (95% CI 97.3 to 110.9) in children of women without psychiatric disorder or depressive symptoms and unexposed. The mean scores for motor development were 97.7 (95% CI 93.8 to 101.6) for children exposed to Fluoxetine, 100.1 (95% CI 95.3 to 105.0) for children exposed to TCAs and 98.3 (95% CI 94.0 to 103.2) in children of women without psychiatric disorder or depressive symptoms and unexposed.

Simon (2002) did not find an association between TCA exposure during pregnancy and developmental delay. A motor delay was found in 2 children exposed to TCAs n=2 (1%) and also in two unexposed children (1%) resulting in an odds ratio (OR) of 1.0 (95%CI 0.14 to 7.17).

Language development

Nulman (2002): Verbal comprehension was measured with the Reynell Developmental Language Scales (RDLS). The mean scores seemed slightly higher in children whose mothers used TCAs (1.1 (0.8 to 1.4)) as compared to children whose mothers used Fluoxetine 0.2 (-0.2 to 0.7) or compared to children from non-depressed women (0.4 (0.0 to 0.7)). However, the multivariate analyses showed that the use of antidepressant drugs did not predict verbal comprehension (Medicated versus comparison (β=0.01, 95%CI -0.90 to 0.89). Expressive language (also measured with the Reynell Developmental Language Scales) seemed comparable in children whose mothers used TCAs (0.2 (–0.1 to 0.4)) as compared to children whose mothers used Fluoxetine (-0.3 (-0.7 to 0.1)) or children from non-depressed women (-0.1 (-0.5 to 0.3)). Multivariate analysis medicated versus comparison (n=92): β=0.94(0.09 to 1.80)

In the study by Simon (2002), no increased risk of speech delay after exposure to antidepressants during pregnancy was found. A diagnosis of speech delay (diagnosed by both a physician diagnosis and confirmation by a formal developmental evaluation) was found in 2 children exposed to TCAs n=2 (1%) and also in two unexposed children (1%) resulting in an odds ratio (OR) of 1.0 (95%CI 0.14 to 7.17).

Late consequences on growth, vision and hearing

No studies were found in which the effect of antidepressant use during pregnancy on growth, vision and hearing of the children was studied.

Level of evidence of the literature

In many studies, data of exposure to antidepressants during pregnancy and outcome in children were extracted from registration data in databases, which yields a risk of misclassification. In other studies, the population consisted of women who contacted a counselling service or teratology information service which may be a risk for selection bias. Control groups in some studies consisted of women exposed to other nonteratogenic drugs, or women who had not been diagnosed with depression, which deviated from the population we are interested in (indirectness).

We started with a low level of evidence for observational studies. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘risk of ADHD’ was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias) and inconsistency, resulting is a very low level of evidence.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘risk of ASD’, language development, behavioral problems, IQ, and neurodevelopment was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias; risk of misclassification) and imprecision (one study)

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effect of non-SSRI antidepressant use in pregnant women with psychiatric disorders on the long-term motor, cognitive, behavioral and social-emotional development of their children, compared to healthy women, women with psychiatric disorders not taking non-SSRI antidepressants during pregnancy?

P (patients): pregnant women with psychiatric disorders;

I (intervention): non-SSRI antidepressant use during pregnancy: tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), monoamine-oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), other non-SSRI antidepressants;

C (control): no (non-SSRI) antidepressant use during pregnancy or discontinuation of antidepressants during pregnancy;

O (outcome): long-term motor, cognitive, behavioral and social-emotional development in children of 5 to 18 years old; neurodevelopment disorders and behavioral disorders within the first 5 years of life; late consequences on growth, speech/language, vision and hearing.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered the long-term motor, cognitive, behavioral and social-emotional development in children of 5 to 18 years old, and neurodevelopment disorders and behavioral disorders within the first 5 years of life as critical outcome measures for decision making. Effects on psychomotor and socio-emotional development in children before the age of 2 years, and late consequences on growth, speech/language, vision and hearing were considered as important outcome measures.

The minimal (clinically) important difference was defined according to the default recommendations of the international GRADE working group, as follows: for dichotomous outcomes as a relative risk reduction or an increase of 25% or more, and for continuous outcomes as a difference of half (0.5) a standard deviation.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 2000 until 21st of February 2019. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 733 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: original research comparing the outcome in women who used antidepressants and women who did not use antidepressants, reporting the outcomes for relevant (subgroups of) antidepressants, including SNRIs, TCAs and other antidepressants (no SSRIs). Sixty studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. The systematic reviews did not report their results usefully. After reading the full text, 54 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 6 original studies were included. We decided to add three relevant studies (Laugesen, 2013; Nulman, 1997; Simon, 2002) that had been included in the systematic reviews but not in our own search.

Results

Nine studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Boukhris, T., Sheehy, O., & Bérard, A. (2017). Antidepressant use in pregnancy and the risk of attention deficit with or without hyperactivity disorder in children. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology, 31(4), 363-373.

- Hagberg, K. W., Robijn, A. L., & Jick, S. (2018). Maternal depression and antidepressant use during pregnancy and the risk of autism spectrum disorder in offspring. Clinical epidemiology, 10, 1599.

- Laugesen, K., Olsen, M. S., Andersen, A. B. T., Frøslev, T., & Sørensen, H. T. (2013). In utero exposure to antidepressant drugs and risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide Danish cohort study. BMJ open, 3(9), e003507.

- Liu, X., Agerbo, E., Ingstrup, K. G., Musliner, K., Meltzer-Brody, S., Bergink, V., & Munk-Olsen, T. (2017). Antidepressant use during pregnancy and psychiatric disorders in offspring: Danish nationwide register based cohort study. bmj, 358, j3668.

- Man, K. K., Chan, E. W., Ip, P., Coghill, D., Simonoff, E., Chan, P. K.,... & Wong, I. C. (2017). Prenatal antidepressant use and risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring: population based cohort study. bmj, 357, j2350.

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie. (2013) Richtlijn Depressie. Retrieved from https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/depressie/startpagina_-_depressie.html

- Nulman, I., Rovet, J., Stewart, D. E., Wolpin, J., Gardner, H. A., Theis, J. G.,... & Koren, G. (1997). Neurodevelopment of children exposed in utero to antidepressant drugs. New England Journal of Medicine, 336(4), 258-262.

- Nulman, I., Koren, G., Rovet, J., Barrera, M., Pulver, A., Streiner, D., & Feldman, B. (2012). Neurodevelopment of children following prenatal exposure to venlafaxine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or untreated maternal depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(11), 1165-1174.

- Nulman, I., Rovet, J., Stewart, D. E., Wolpin, J., Pace-Asciak, P., Shuhaiber, S., & Koren, G. (2002). Child development following exposure to tricyclic antidepressants or fluoxetine throughout fetal life: a prospective, controlled study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(11), 1889-1895.

- Simon, G. E., Cunningham, M. L., & Davis, R. L. (2002). Outcomes of prenatal antidepressant exposure. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(12), 2055-2061.

- Stein, A., Pearson, R. M., Goodman, S. H., Rapa, E., Rahman, A., McCallum, M.,... & Pariante, C. M. (2014). Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. The Lancet, 384(9956), 1800-1819.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, case series))

Research question: Is the use of antidepressants (non-SSRIs) during pregnancy in women with psychiatric disorders related with an increased risk of late consequences on locomotion, cognition, behavior and social emotional development in the child?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Boukhris 2017

Canada |

register-based cohort study

Quebec Pregnancy/ Children Cohort (QPC), an ongoing population-based cohort; data collected prospectively for all pregnancies January 1998 - December 2009 (n = 186 165 women; 289 688 pregnancies). |

all full-term (≥37 weeks of gestation) singletons born alive January 1998 - 31 December 2009

Infants with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) diagnosis were excluded

144 406 eligible full-term liveborn singletons

Maternal age (years) – mean (SD) AD exposed: 28.5 (5.7) AD non-exposed:27.7 (5.5)

Maternal history of ADHD (N) AD exposed: 53 (1.1%) AD non-exposed: 133 (0.1%) |

exposure to antidepressant (Ads)

used the RAMQ Prescription Drug database to evaluate exposure to Ads

exposure: at least one prescription filled at any time during pregnancy or a prescription filled before pregnancy that overlapped the 1DG

AD classes: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic ADs (TCAs), monoamine-oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), and other Ads

AD exposed: n=4678

|

reference category for all analyses: infants who were not exposed in utero to any AD

AD non-exposed: n=139 728 |

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: up to a maximum of 11 years of follow-up

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

ADHD: children with a diagnosis of ADHD or at least one prescription filled for ADHD medications between birth and the end of follow-up

ADHD in 4564 children (3.2%)

antidepressant use during pregnancy was significantly associated with slightly increased risk of ADHD, HR 1.2 (95% CI 1.0, 1.4).

risk of ADHD (HR and 95%CI) related to use AD during the 2nd/3rd trimesters of pregnancy

-all ADs (2501 infants): HR 1.3 (1.0, 1.6) -only SSRIs (1561 infants): HR=1.2 (0.9, 1.6) -only SNRIs (445 infants): HR=1.4 (0.8, 2.5) -only TCA (227 infants): HR= 1.8 (1.0, 3.1) -only MAOIs (1 infant): not applicable -Other antidepressants (105 infants): HR=0.5 (0.1, 2.2)

analyses: Adjusted for: use of AD classes in the 1st trimester of pregnancy, infant characteristics (sex, year of birth), maternal variables (maternal age at 1DG, level of education (≤12 years), recipient of social assistance, living alone, area of residence on the 1DG, chronic/gestational hypertension, chronic/gestational diabetes, other psychiatric disorders, maternal history of depression/anxiety, and maternal history of ADHD) |

mean age at first ADHD diagnosis was 6.3 years (range 0–11 years!)

history of maternal depression/ anxiety was considered to be a potential confounder and was adjusted for in the analyses

up to a maximum of 11 years of follow-up |

|

Hagberg 2018

UK |

cohort study with nested sibling case–control analysis

Using the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), a large, population- based electronic medical database. |

mother–baby pairs where the mother had ≥12 months of history before the delivery date and the child had ≥3 years of follow-up

mothers, aged 13–44 years, and their live-born, singleton infants born between 1989 and 2011

|

prenatal antidepressant exposure

antidepressant class: SSRIs, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), other antidepressants

40,387 eligible exposed mother–baby pairs (12,994 women untreated depression, 25,778 had treated depression, and 1,615 received antidepressants for indications other than depression)

|

matched with 154,107 unexposed mother–baby pairs

non-exposed: neither depression nor prescriptions for antidepressants

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: child ≥3 years of follow-up

Years of follow-up: mean 8.7, IQ range 4.9–11.5

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

risk of autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

autism = all children with at least one Read diagnostic code indicating ASD recorded at any time, including codes for autism, Asperger’s syndrome, and pervasive developmental disorder (PDD)

2,154 offspring with ASD among 194,494 mother–baby pairs (1,1%)

RR of ASD (reference: non exposed) -treated depression: 1.70 (1.51–1.92) -untreated depression: 1.49 (1.27–1.75)

RR Adjusted for child sex, maternal BMI, smoking status, parity, anxiety, and other psychiatric disorders

in subgroups antidepressants, RR of ASD (reference: non exposed) SSRIs only: 1.68, 95% CI 1.46–1.92 TCAs only: 1.95, 95% CI 1.58–2.40 users of multiple classes: 1.78, 95% CI 1.29–2.45 |

Validation studies have indicated that over 90% of ASD diagnoses in the CPRD were confirmed upon record review.

sibling was eligible as a control if he/ she was the same sex as the ASD case, had no diagnosis of ASD at any time, and had at least 3 years of follow-up after birth and if the mother had at least 12 months of recorded history before the sibling’s delivery date.

Sibling case-control: no data on specific antidepressants

child ≥3 years of follow-up

Years of follow-up: mean 8.7, IQ range 4.9–11.5

|

|

Laugesen 2013

Denmark |

cohort study

Using the Danish Medical Birth Registry

|

877 778 children, from cohort of all singletons born alive from 1996 to 2009

Siblings born to the same mother were identified through the civil registration system

|

in utero exposure to antidepressants

users: prescription for an antidepressant 30 days prior to or during pregnancy, as identified through the Danish National Prescription Registry.

15 008 (1.7%) children were exposed to antidepressants SSRIs 78% SNRIs 5% TCAs 5% other 4% combined 8%

|

former users of antidepressants: women, who had redeemed a prescription up to 30 days prior to pregnancy, n=45 978

never users: women who had never redeemed a prescription. n=816 792

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: followed until the date of ADHD prescription, an ADHD diagnosis, emigration, death or the end of follow-up

median follow-up: 8 years

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

risk of ADHD

prescription for ADHD medication or an ADHD hospital diagnosis

Using the Danish Psychiatric Registry and the Danish National Registry of Patients

HRs (95% Cis) for time to ADHD, users versus non-users SSRIs HR=1.2 (1.0 to 1.5) SNRIs HR=1.0 (0.4 to 2.5) TCAs HR=1.1 (0.6 to 2.0) other HR=1.6 (0.8 to 3.0) combined HR=0.8 (0.4 to 1.7)

Adjusted for gender of the child, calendar time at birth, birth order, maternal age at birth, maternal smoking status, maternal psychiatric diagnoses, paternal psychiatric diagnoses, maternal diseases during pregnancy (infections, epilepsy) and maternal medication (anxiolytics/ hypnotics/sedatives) use during pregnancy |

population: overlapping with Liu 2017

All antidepressants, as well as drugs for ADHD, are available by prescription only in Denmark

Diagnosing ADHD also by private practice psychiatrists and general practitioners without hospital contact (not recorded in the Danish Psychiatric Registry or the Danish National Registry of Patients). To ensure completeness, we defined ADHD as either a diagnosis of ADHD or a prescription for ADHD medication.

followed until the date of ADHD prescription, an ADHD diagnosis, emigration, death or the end of follow-up

median follow-up: 8 years |

|

Liu 2017

Denmark |

Population based cohort study

data from the Danish Civil Registration System. All live births and residents in Denmark; data are collected by midwives or physicians overseeing delivery |

905 383 liveborn singletons born during 1998-2012 |

antidepressant use within two years before and during pregnancy

groups: antidepressant continuation (use both before and during pregnancy), and new user (use only during pregnancy).

data from the Danish National Prescription Registry. This register covers all prescriptions dispensed in Denmark since 1995

defined antidepressant use during pregnancy: a prescription dispensed on any date from one month before pregnancy until delivery

calculated the number of days exposed per prescription

21 063 (2.3%) children: mothers used antidepressants during pregnancy

- 1.8% (n=16 154) used SSRI monotherapy, - 0.4% (n=3295) used non-SSRI antidepressant monotherapy, - 0.2% (n=1614) used both SSRI and non-SSRI antidepressants

|

groups - unexposed, n= 854241 - antidepressant discontinuation (use before but not during pregnancy) n=30079 |

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: followed for a maximum of 16.5 years

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

diagnosis of psychiatric disorders (ICD-10 codes F00-F99) in the offspring

Information on psychiatric diagnosis came from the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register.

32 400 children were diagnosed as having psychiatric disorders.

15 year cumulative incidence of psychiatric disorders in the offspring: unexposed group: 8.0% (95% CI 7.9% to 8.2%) discontinuation group: 11.5% (10.3% to 12.9%) continuation group: 13.6% (11.3% to 16.3%) new user group: 14.5% (10.5% to 19.8%) for the

Hazard ratios of any psychiatric disorders in continuous antidepressant use, compared with mothers who discontinued antidepressant use - all antidepressants: HR=1.27 (1.17 to 1.38) subgroups: - Non-SSRI monotherapy: HR=1.15 (0.96 to 1.40) - SSRI monotherapy: HR=1.25 (1.14 to 1.37) - Use both SSRI and non-SSRI: HR=1.72 (1.40 to 2.11)

HR Adjusted for maternal age at delivery, primiparity, maternal psychiatric history at delivery, inpatient and outpatient psychiatric treatment from 2 years before pregnancy until delivery, dispensing of other psychotropic prescriptions during pregnancy, dispensing of antiepileptic prescriptions during pregnancy, number of non-psychiatric hospital visits during pregnancy, smoking during pregnancy, place of residence, marital status, highest education, income, calendar year of delivery, and paternal psychiatric history at time of delivery. |

Sensitivity analyses: impact of redefining antidepressant exposure and redefined psychiatric disorders in offspring

followed for a maximum of 16.5 years |

|

Man 2017 |

Population based cohort study

Data from the Hong Kong population based electronic medical records on the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System CDARS, a territory wide database in Hong Kong. CDARS was developed by the Hong Kong Hospital Authority, a statutory body that manages all public hospitals and their associated ambulatory clinics in Hong Kong

The database contains: patient specific data, incl. personal information, payment method, prescription information, pharmacy dispensing information, diagnosis, laboratory test results, and admission and discharge information |

190 618 children born in Hong Kong public hospitals between January 2001 and December 2009 (only live births were included, with valid mother-child linkage)

mean maternal age at delivery was 31.2 years (SD 5.1 years) |

maternal antidepressant use during pregnancy

extracted from the prescribing and dispensing records in CDARS

classified the children into four groups: -preconception users -never users -non-gestational users -used antidepressants during pregnancy

1252 had a mother who used prenatal antidepressants -425 SSRI mono -470 non-SSRI mono -129 SSRIs and non-SSRIs -101 SSRIs and antipsychotics, -91 non-SSRIs and antipsychotics, -36 SSRIs, non-SSRIs, and antipsychotics

2275 mothers received antidepressants before pregnancy; 1486 discontinued treatment before pregnancy; 789 continued treatment

|

no use antidepressants during pregnancy n=189002 -preconception users -never users

1486 discontinued treatment before pregnancy; |

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: at least six years’ follow-up; mean follow-up time 9.28 years (range 7.4-11.0 years).

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

risk of attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in offspring; ADHD in children aged 6 to 14 years

ADHD = ADHD diagnosis, registered as ICD-9-CM diagnosis code 314, or a prescription for an ADHD drug as recorded in CDARS

5659 children (3.0%) diagnosis of ADHD or received treatment for ADHD.

antidepressant use: HR=1.39 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.82)

Non-SSRIs (versus non-users): ADHD cases: 31 in non-SSRI users, 5564 in non-users Hazard ratio’s (95% CI) During pregnancy 1.59 (1.19 to 2.14) 1st trimester 1.64 (1.13 to 2.38) 2nd trimester 1.72 (1.16 to 2.53) 3rd trimester 1.65 (1.13 to 2.40)

model 3: Adjusted for maternal age at delivery, infant’s sex, birth year, birth hospital, parity, maternal underlying illness before delivery (pre-existing diabetes, epilepsy, gestational diabetes, hypertension), and socioeconomic status. + maternal psychiatric conditions. + psychiatric drug use. |

at least six years’ follow-up

mean follow-up time 9.28 years (range 7.4-11.0 years). |

|

Nulman 1997 |

retrospective, observational study

data from the Motherisk Program; provides information and consultation to women, their families, and health professionals on the risk/safety of drug, chemical, radiation, and infectious exposures during pregnancy and lactation |

the children of all women counseled by the program during the first trimester of pregnancy regarding therapy with either a tricyclic antidepressant drug or fluoxetine.

control group consisted of women who had taken innocuous drugs such as acetaminophen or oral penicillin or who had had dental x-ray films obtained during pregnancy.The control mothers were chosen from this list of women whose clinic appointments were closest (within two months) to those in the other two groups.

excluded: women in whom antidepressant-drug therapy discontinued before conception, > one antidepressant drug, or exposed to known teratogens during the pregnancy |

children of 80 mothers who had received a tricyclic antidepressant drug during pregnancy:

55 children whose mothers had received fluoxetine during pregnancy |

children whose mothers had not been exposed during pregnancy to any agent known to affect the fetus

n=84 |

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: N/A

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

children's global IQ and language development were assessed between 16 and 86 months

1.Reynell Developmental Language Scales, mean scores (95%CI), - Verbal comprehension Fluoxetine 1.2 ± 1.2 TCAs 1.3 ± 0.8 control 1.1 ± 0.9

- Expressive language Fluoxetine -0.2 ± 1.0 TCAs 0.3 ± 0.9 control 0.1 ± 1.0

2. Scores on Bayley Mental development Fluoxetine 117 ± 17 TCAs 118 ± 17 Control 115 ± 14

3. global cognitive index McCarthy, mean score ± SD Fluoxetine: 114 ± 16 TCAs: 117 ± 10 control: 114 ± 13

The mean global IQ values in the three groups of children were similar. After adjustment, the scores on the Verbal Comprehension and Expressive Language portions of the Reynell scales were similar in the three groups. |

Study population partially overlapped with more recent study of Nulman (2002); 18 fluoxetine and 36 TCA exposed women

regression analysis adjusted for children’s age, maternal IQ, socioeconomic status, depression score, and duration exposure to drug (1st trimester) entire pregnanacy) |

|

Nulman 2002 |

prospectively

Motherisk Program provides information and consultation to women, their families, and health professionals on the risk/safety of drug, chemical, radiation, and infectious exposures during pregnancy and lactation

mothers were approached during the first trimester of pregnancy |

three groups of mother-child pairs;

1. all women who had been counseled by the program regarding therapy with TCAs and continued taking throughout gestation, n=46

2. all women who had been counseled by the program regarding therapy with fluoxetine and continued taking throughout gestation, n=40

3. women who had no history of a psychiatric disorder or depressive symptoms (score less than 16 on CES-D) and were unexposed to any drug; chosen randomly from a list of women who had visited our clinic < 2 months before or after the visits by the study groups, n=36

All subjects receiving antidepressant medications diagnosed as having major depression after an independent psychiatric evaluation and found to require pharmacotherapy.

excluded: women whose antidepressant was discontinued before conception or during pregnancy; women exposed to >1 antidepressant drug or known teratogens |

exposed to tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) or fluoxetine throughout fetal life

TCAs: 18 took amitriptyline, 12 imipramine, seven clomipramine,three desipramine, three nortriptyline, two doxepin, and one maprotiline; n=32 for an affective disorder n=11 for pain control n =3 for an anxiety disorder

fluoxetine: n=36 fluoxetine (20 to 80 mg a day) for depression n=4 fluoxetine for an anxiety disorder. |

women who had no history of a psychiatric disorder or depressive symptoms and were unex posed to any drug (N=36)

Mothers in the comparison group were chosen randomly from a list of women who had visited our clinic within the 2 months before or after the visits by the study groups and who were not depressed

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: 15-71 months

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

neurodevelopment of children, assessed by a psychometrist blinded to intrauterine exposure

Cognitive Outcome of Children, 1.Reynell Developmental Language Scales, mean scores (95%CI), - Verbal comprehension Fluoxetine 0.2 (-0.2 to 0.7) TCAs 1.1 (0.8 to 1.4) Comparison 0.4 (0.0 to 0.7) Medicated versus comparison (n=93): β=0.01 (–0.90 to 0.89)*

- Expressive language Fluoxetine –0.3 (–0.7 to 0.1) TCAs 0.2 (–0.1 to 0.4) Comparison –0.1 (–0.5 to 0.3) Medicated versus comparison (n=92): β=0.94(0.09 to 1.80)

2. Scores on Bayley Scales of Infant Development (children between 15 and 30 months of age) - Mental development Fluoxetine 104.4 (98.9 to 109.9) TCAs 110.9 (104.0 to 118.0) Comparison 104.1 (97.3 to 110.9)

- Psychomotor development Fluoxetine 97.7 (93.8 to 101.6) TCAs 100.1 (95.3 to 105.0) Comparison 98.3 (94.0 to 103.2)

3. global cognitive index from McCarthy (children older than 30 months), mean score (95%CI) fluoxetine: 108.7 (87.8 to 129.5) TCAs: 117.8 (112.6 to 122.9) comparison: 118.4 (113.6 to 123.3) Medicated versus comparison (n=37): β=19.88 (–8.12 to 47.88)

*Regression analyses, adjusted for:

mother’s IQ, socioeconomic status, ethanol use and cigarette smoking, depression severity, depression duration, treatment duration, number of depressive episodes after delivery, and medications used for depression treatment were entered as independent variables |

18 fluoxetine and 36 TCA exposed women from previous study (Nulman 1997) were also included

children in the fluoxetine group were significantly younger than those in the comparison group

“Children in the TCA group scored slightly higher on the Reynell Developmental Language Scales, but all three groups scored within the normal range.”

maternal depression was a significant negative predictor for McCarthy global cognitive index. The antidepressant drugs themselves did not predict cognitive achievements

follow up 15–71 Months

|

|

Nulman 2012 |

prospectively collected data

data from Motherrisk program at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. database contains information about pregnant women who sought counseling on the pregnancy safety of medications, incl. antidepressants and nonteratogens |

selection of mothers: - women with depression were selected; Depressive episodes were defined according to DSM-IV criteria and diagnosed by the woman’s psychiatrist. Only depressed women receiving pharmacotherapy before or during pregnancy were included - control: who called Motherisk to inquire about nonteratogenic exposure (e.g., acetaminophen)

Excluded: mothers exposed to polytherapy for depression or known teratogens, substance abuse, other psychiatric conditions, premature children, children with medical conditions unrelated to in utero exposure that may affect cognitive outcomes |

neurotransmitter reuptake inhibitors used as antidepressants during pregnancy

children born to 1) depressed women who took venlafaxine during pregnancy (N=62), 2) depressed women who took SSRIs during pregnancy (N=62), 3) depressed women who were untreated during pregnancy (N=54),

limited information on how antidepressant use was measured

Of the 124 women exposed to antidepressants, 81 were exposed throughout pregnancy, 21 in the first trimester only, four in the first and second, two in the second only, 11 in the second and third, and five in the third only. |

children born to nondepressed, healthy women (N=62). |

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: range in age from 3 years to 6 years, 11 months

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? N/A |

psychometrist masked to group affiliation tested all children

IQ, Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, Full-scale IQ, mean (sd) venlafaxine: 105 (14) SSRI: 105 (13) untreated depression: 108 (14) nondepressed: 112 (11)

Behavioral profiles, using the Child Behavior Checklist and Conners’ Parent Rating Scale, both completed by the mother “Children in groups 1, 2, and 3 had more clinically significant behavioral problems as assessed with the Child Behavior Checklist internalizing, externalizing, and total problems subscales and on the Conners’ Parent Rating Scale total and DSM-IV total symptom indices” (only reported in figures)

IQ: “After we controlled for other factors, group membership did not predict cognitive outcomes”

Child Behavior: “Dose and duration of maternal antidepressant treatment during pregnancy (…) were not predictors of these outcomes” |

multivariate methods only reported a result (β) for ‘treatment group’. No results for venlafaxine versus untreated depression or non-depressed

range in age from 3 years to 6 years, 11 months |

|

Simon 2002

USA |

cohort study, sample drawn from Group Health Cooperative, a prepaid health plan serving approximately 400,000 members in Washington State. |

all live births between January 1, 1986, and December 31, 1998

identified using Hospital discharge records

sample limited to -those enrolled at primary care facilities owned by Group Health Cooperative. - mothers continuously enrolled in Group Health Cooperative for 360 days before delivery

|

Exposure to TCAs or SSRIs

Pharmacy records were used to identify all antidepressant pre scriptions filled or refilled during the 360 days before delivery

Those with any antidepressant prescriptions during the 270 days before delivery were considered exposed. patients with antidepressant prescriptions filled in the period between 270 and 360 days before delivery were classified as indeterminate and excluded

population: TCAs n=209 SSRI: n=185 |

Mothers with no antidepressant prescriptions during the period of 360 days before delivery were considered unexposed. unexposed infants, n=209

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: up to 2 years For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N/A

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? no data on completeness of follow up |

outcomes included motor delay and speech delay Data sources included - Standardized physical examination records from pediatric health-monitoring, from birth to age 2: develop mental delay. - Records of outpatient visits and hospital admissions: neurological disorders, and developmental delay.

Final diagnosis of speech or motor delay: both a physician diagnosis and confirmation by a formal developmental evaluation.

Seizure disorder TCAs n=4 (1.9%) unexposed n=0 (0%) Motor delay TCAs n=2 (1%) unexposed n=2 (1%) OR (95%CI) 1.0 (0.14 to 7.17)

Speech delay TCAs n=2 (1%) unexposed n=2 (1%) OR (95%CI) 1.0 (0.14 to 7.17) |

Chart reviewers and investigators remained blind to exposure status throughout chart reviews and primary data analyses

no correction for potential confounding

Group Health Cooperative’s computerized information systems record outpatient prescriptions, outpatient visits, and hospital discharges. Except for Medicare members, all Group Health Cooperative plans include prescription drug coverage.

up to 2 years;

no data on completeness of follow up |

HR= hazard ratio = the chance of an event occurring in the treatment arm divided by the chance of the event occurring in the control arm.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (observational: non-randomized clinical trials, cohort and case-control studies)

Research question: Is the use of antidepressants (non-SSRIs) during pregnancy in women with psychiatric disorders related with an increased risk of late consequences on locomotion, cognition, behavior and social emotional development in the child?

|

Study reference (first author, year of publication) |

Bias due to a non-representative or ill-defined sample of patients?1

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to insufficiently long, or incomplete follow-up, or differences in follow-up between treatment groups?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to ill-defined or inadequately measured outcome ?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate adjustment for all important prognostic factors?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Boukris 2017 |

likely |

likely |

likely |

unlikely |

|

Hagberg 2018 |

likely |

likely |

likely |

unlikely |

|

Laugesen 2013 |

likely |

likely |

likely |

unlikely |

|

Liu 2017 |

likely |

likely |

likely |

unlikely |

|

Man 2017 |

likely |

likely |

likely |

unlikely |

|

Nulman 1997 |

likely |

unlikely |

likely |

likely |

|

Nulman 2002 |

likely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

|

Nulman 2012 |

likely |

unlikely |

likely |

likely |

|

Simon 2002 |

likely |

likely |

likely |

likely |

- Failure to develop and apply appropriate eligibility criteria: a) case-control study: under- or over-matching in case-control studies; b) cohort study: selection of exposed and unexposed from different populations.

- Bias is likely if: the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large; or differs between treatment groups; or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups; or length of follow-up differs between treatment groups or is too short. The risk of bias is unclear if: the number of patients lost to follow-up; or the reasons why, are not reported.

- Flawed measurement, or differences in measurement of outcome in treatment and control group; bias may also result from a lack of blinding of those assessing outcomes (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Failure to adequately measure all known prognostic factors and/or failure to adequately adjust for these factors in multivariate statistical analysis.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

El Marroun 2014 |

systematic, but narrative review (no useful data from original studies) |

|

Gentile 2011 |

systematic, but narrative review (no useful data from original studies) |

|

Jiang 2018 |

limited data about outcome original studies; relevant studies were added to included studies (Laugesen 2013) |

|

Prady 2018 |

systematic review, no meta-analysis; liever origineel van relevante studies |

|

Simoncelli 2010 |

systematic, but narrative review (no useful data from original studies) relevant studies were added to included studies (Simon 2002) |

|

Suri 2010 |

systematic, but narrative review (no useful data from original studies) |

|

Tuccori 2009 |

systematic, but narrative review (no useful data from original studies) |

|

Udechuku 2010 |

systematic, but narrative review (no useful data from original studies) |

|

Uguz 2018 |

systematic, but narrative review (no useful data from original studies) |

|

Santucci 2014 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Yamamoto 2019

|

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Ackerman 2017 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Andrade 2017 |

narrative review |

|

Austing 2013 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Brandlistuen 2015 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Carvalho 2016 |

narrative review |

|

Casper 2003 |

intervention: SSRIs only |

|

Eberhard-Gran 2005 |

narrative review |

|

Eriksen 2015 |

intervention: SSRIs and anxiolytics |

|

Fenger-Gron 2011 |

narrative review |

|

Galbally 2011 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Galbally 2015 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Galbally 2017 |

other research question |

|

Galbally 2018 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Gentile 2010 |

narrative review |

|

Grove 2018 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Grzeskowiak 2016 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Gustafsson 2018 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Hanley 2013 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Hanley 2015 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Healy 2016 |

intervention: SSRIs |

|

Hurault-Delarue 2016 |

intervention: psychotropic drugs |

|

Jain 2005 |

narrative review |

|

Lorenzo 2014 |

narrative review |

|

Man 2018 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

McDonagh 2014 |

interventio: SSRIs |

|

Mezzacappa 2017 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Morales 2018 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Mortensen 2003 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Nijenhuis 2012 |

narrative review |

|

Özerdem 2014 |

narrative review |

|

Pedersen 2013 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Pedersen 2010 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Rai 2014 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Rzewuska 2009 |

no relevant outcome measures |

|

Stein 2012 |

other research question |

|

Sujan 2018 |

no relevant outcome measures |

|

Sujan 2017 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Suri 2011 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Viktorin 2017 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Way 2007 |

not relevant for PICO (outcome measure) |

|

Weikum 2012 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

|

Zhou 2018 |

Results not reported for relevant subgroups of antidepressants |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 23-07-2021

Bij het opstellen van de modules heeft de werkgroep een inschatting gemaakt over de maximale termijn waarop herbeoordeling moet plaatsvinden. De geldigheid van de richtlijnmodules komt eerder te vervallen indien nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding zijn een herzieningstraject te starten.

|

Module1 |

Regiehouder (s)i |

Jaar van autorisatie |

Eerstvolgende beoordeling actualiteit richtlijn2 |

Frequentie van beoordeling op actualiteit3 |

Wie houdt er toezicht op actualiteit4 |

Relevante factoren voor wijzigingen in aanbeveling5 |

|

Lange termijn effecten niet-SSRI antidepressiva |

NVOG |

2021 |

2026 |

Eens in vijf jaar |

NVOG |

Nieuwe literatuur |

1 Naam van de module

i Regiehouder van de module (deze kan verschillen per module en kan ook verdeeld zijn over meerdere regiehouders)

2 Maximaal na vijf jaar

3 (Half)Jaarlijks, eens in twee jaar, eens in vijf jaar

4 Regievoerende vereniging, gedeelde regievoerende verenigingen, of (multidisciplinaire) werkgroep die in stand blijft

5Lopend onderzoek, wijzigingen in vergoeding/organisatie, beschikbaarheid nieuwe middelen

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling van deze richtlijn werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodules.

De richtlijn is ontwikkeld in samenwerking met:

- Patiëntenfederatie Nederland

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijn is in 2018 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor zwangere patiënten die ‘niet-SSRI’ antidepressiva en/of antipsychotica gebruiken. De werkgroepleden zijn door hun beroepsverenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname. De werkgroep is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze richtlijn.

Werkgroep

- Dr. A. Coumans, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht, NVOG

- Dr. H.H. Bijma, gynaecoloog, Erasmus Medisch Centrum, Rotterdam, NVOG

- Drs. R.C. Dullemond, gynaecoloog, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, Den Bosch, NVOG

- Drs. S. Meijer, gynaecoloog, Gelre Ziekenhuis, Apeldoorn, NVOG

- Dr. M.G. van Pampus, gynaecoloog, OLVG, Amsterdam, NVOG

- Drs. M.E.N. van den Heuvel, neonatoloog, OLVG Amsterdam, NVK

- Drs. E.G.J. Rijntjes-Jacobs, neonatoloog, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum, Leiden, NVK

- Dr. K.M. Burgerhout, psychiater, Amphia Ziekenhuis, Breda, NVvP

- Dr. E.M. Knijff, psychiater, Erasmus Medisch Centrum, Rotterdam, NVvP

Meelezers

- Dr. A.J. Risselada, klinisch farmacoloog, Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis Assen

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. E. van Dorp-Baranova, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. M. Moret-Hartman, senior-adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- N. Verheijen, senior-adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- M. Wessels, literatuurspecialist, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Dr. A. Coumans |

gynaecoloog-perinatoloog Maastricht UMC+ |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Dr. H. H. Bijma |

Gynaecoloog, Erasmus MC, afdeling verloskunde en gynaecologie, subafdeling verloskunde en prenatale geneeskunde |

lid werkgroep wetenschap LKPZ, onbetaald |

geen |

geen |

|

Drs. S. Meijer |

gynaecoloog Gelre Ziekenhuis, Apeldoorn |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Drs. R. C. Dullemond |

gynaecoloog- perinatoloog, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis |

LKPZ bestuur - voorzitter, onbetaald mind 2 care - raad van toezicht, onbetaald dagelijks bestuur @verlosdenbosch (integrale geboortezorg organisatie) als gynaecoloog uit het JBZ, onbetaald danwel deels in werktijd |

geen |

geen |

|

Drs. E. G. J. Rijntjes-Jacobs |

kinderarts-neonatoloog, afdeling neonatologie, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum |

LKPZ bestuur – secretaris, onbetaald |

geen |

geen |

|

Dr. M. G. van Pampus |

Gynaecoloog, OLVG Amsterdam |

onbetaalde nevenfuncties |

geen |

geen |

|

Dr. E. M. Knijff |

Psychiater, Erasmus MC polikliniek psychiatrie & zwangerschap medisch coördinator polikliniek Erasmus MC |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Drs. M. E. N. van den Heuvel |

kinderarts-neonatoloog, OLVG Amsterdam |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Dr. K. Burgerhout |

Psychiater, Reinier van Arkel, POP-poli |

geen |

geen |

geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief