Niet-farmacologische interventies

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is het effect van een afleidingsinterventie in het traject op de operatiekamer op preoperatieve angst en postoperatief comfort bij kinderen die algehele anesthesie ondergaan?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg om preoperatief niet-farmacologische strategieën toe te passen om preoperatieve angst te verminderen.

Zet hiervoor de al in het ziekenhuis of op de afdeling beschikbare comfort verhogende (of angst reducerende) strategieën op individuele basis in.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

De cruciale uitkomstmaat angst in de context van anesthesie bij kinderen werd gerapporteerd door vier systematic reviews en twee RCTs die vier verschillende afleidingsinterventie typen onderzochten.

Acht studies uit de systematic review van Simonetti (2022) rapporteerden het effect van virtual reality op angst in de context van anesthesie bij kinderen (Eijlers, 2019; Jung, 2020; Park, 2019; Ryu, 2017; Ryu, 2018; Ryu, 2019). Er werd daarbij een klinisch relevant voordeel gezien voor het gebruik van virtual reality als afleidingsinterventie. De overall bewijskracht van deze studies is laag. Dit heeft te maken met het risico op bias, doordat het niet mogelijk was om te blinderen (doordat de interventie bestond uit een virtual reality instrument) en omdat onduidelijk was of baseline karakteristieken vergelijkbaar waren. De meeste studies die geïncludeerd werden in deze review werden uitgevoerd in hetzelfde land (Korea). Daarnaast kruist het betrouwbaarheidsinterval de grens van klinische besluitvorming (imprecisie).

Veertien studies uit de systematic review van Suleiman-Martos (2022) rapporteerden het effect van game based interventies (Buffel, 2019; Chaurasia, 2019; Clausen, 2021; Dwairej, 2020; Forouzandeh, 2020; Gao, 2014; Huntington, 2018; Lee, 2012; Marechal, 2017; Patel, 2006; Rodriguez, 2019; Scarano, 2021; Al-Nerabieah, 2020; Stewart, 2019). Er werd daarbij een klinisch relevant voordeel gezien voor het gebruik van game based interventies als afleidingsinterventie. De overall bewijskracht van deze studies is erg laag. Dit heeft te maken met het risico op bias doordat het niet mogelijk was om te blinderen, het verschil in effect grootte tussen de studies (inconsistentie), en de kleine studiepopulatie.

Zes studies uit de systematic review van Rantala (2020) rapporteerden het effect van web based interventies (Fortier, 2015; Kerimoglu, 2013; Marechal, 2017; Mifflin, 2012; Seiden, 2014; Stewart, 2018). Er werd daarbij een klinisch relevant voordeel gezien voor het gebruik van web based interventies als afleidingsinterventie. De overall bewijskracht van deze studies is erg laag. Dit heeft te maken met het risico op bias door onduidelijke of onvolledige rapportage van toewijzing, verschil in grootte van het effect tussen de studies (inconsistentie), en de kleine studiepopulatie.

Acht studies in de systematic review van Chow (2016) rapporteerden het effect van audiovisuele interventies (Kain, 2001; Kain, 2004; Kain, 2007; Lee, 2012; Lee; 2013; Patel, 2006, Karabulut & Duygu, 2009; O’Connor-Von, 2008). Er werd daarbij een klinisch relevant voordeel gezien voor het gebruik van audiovisuele interventies als afleidingsinterventie. De overall bewijskracht is laag. Dit heeft te maken met het risico op bias door onduidelijke of onvolledige rapportage van randomisatie en toewijzing of door het gebrek aan blindering, het verschil in effect grootte tussen de studies (inconsistentie), en de kleine studiepopulatie.

De overall bewijskracht was laag tot zeer laag om het effect van afleidingsinterventies op verlatingsangst van ouders, acceptatie van masker en gedragsverandering te kunnen beoordelen.

In de Nederlandse kindergeneeskundige praktijk wordt tijdens medische verrichtingen gebruik gemaakt van procedurele comfortzorg, een holistische benadering waarbij o.a. niet farmacologische technieken gericht op optimaal gedrag en beleving tijdens de medische verrichting worden ingezet. De hiervoor gebruikte combinatie van maatregelen wordt individueel bepaald en omvat (voorafgaand aan en tijdens de procedure) informatie geven op een kindvriendelijke manier, gebruik makend van positief taalgebruik en vertrouwen winnen van ht kind. Tijdensde procedure wordt gebruik gemaakt van rustgevende omgevingsfactoren, optimale houding, op het ontwikkelingsniveau van het kind afgestemde afleiding, en bijvoorbeeld VR brillen als dit beschikbaar is (Leroy, 2016). Hoewel dit een andere setting kent, is het aannemelijk dat deze aanpak ook preoperatief gebruikt kan worden.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Een belangijk aspect van niet-farmacologische interventies is het bieden van voorlichting op een kindvriendelijke manier, het winnen van vertrouwen van het kind en het gebruik van positief taalgebruik. Het is belangrijk om het kind goed voor te bereiden door op een duidelijk en begrijpelijke manier uit te leggen wat er gaat gebeuren. Ouders spelen hierin ook een balangrijke rol, omdat zij hun kind het beste knennen en kunnen inschatten welke niet-farmacologisch interventie het meest geschikt is. Voor meer informatie over comfort en afleiding voor kinderen kan een infosheet geraadpleegd worden (Infosheet-Middelen-Technieken-en-Interventies_links_v05.pdf (kindenzorg.nl))

Niet-farmacologische interventies zijn allen niet wetenschappelijk bewezen effectief, maar in de Nederlandse kindergeneeskundige praktijk is gebleken dat een individueel op comfort gericht plan wel stress verlagend werkt. Het is aannemelijk dat het aanbieden van een individueel plan daarom sowieso door de patiënt en zijn ouders wordt gewaardeerd (Leroy, 2016; Bray, 2023).

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Voor het opstellen van een individueel plan kan gebruik worden gemaakt van de in het ziekenhuis aanwezige fysieke middelen (afleidingsmateriaal, spelletjes, zoekboeken, evt. VR). Daar zijn geen noemenswaardige extra kosten mee gemoeid. Door tijdig en proactief een dergelijk plan te maken kan echter ook tijdsbesparing worden gerealiseerd op de korte termijn door betere medewerking van de patient bij een procedure en op de langere termijn doordat de patient minder stress en/of angst ontwikkelt voor procedures in de toekomst.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Het opstellen van een individueel procedureel comfortplan is mogelijk voor patiënten van elk ontwikkelingsniveau. Door bewustwording van het belang van dit plan op, maar ook buiten de operatiekamer door alle zorgverleners kan het een gezamenlijke verantwoordelijkheid zijn waarbij iedere zorgverlener die het kind ontmoet het kan opstellen. De patiënten en zijn ouders worden zelf “eigenaar” van het plan en kunnen het waar nodig bijstellen afhankelijk van ontwikkelingsfase en ervaringen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Ernstige preoperatieve angst bij kinderen en ouders kan leiden tot verminderde compliance bij de inductie en toegenomen postoperatief pijnstillergebruik, verstoord gedrag postoperatief en andere complicaties. Voor het verminderen van angst kan gebruik gemaakt worden van niet-farmacologische technieken waarbij het kind afgeleid wordt of leert om te gaan met de emoties. Deze module geeft antwoord op de vraag in hoeverre niet-farmacologische technieken nog een additief effect hebben op de preoperatieve angst en postoperatieve gedragsveranderingen.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Low GRADE |

Virtual reality may result in a large reduction of paediatric anxiety during the perioperative period.

Sources: (Simonetti, 2022) |

|

Very low GRADE |

Game based intervention may result in a slight reduction of paediatric anxiety during the induction of anaesthesia.

Sources: (Suleiman-Martos, 2022) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of web based mobile health interventions on anxiety in paediatric patients and their parents in the context of day surgeries.

Sources: (Rantala, 2020) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of audio visual interventions preoperative anxiety in children receiving elective surgery under general anesthesia.

Sources: (Chow, 2016) |

|

- GRADE |

In the context of surgery in children, no evidence was found regarding the effect of distraction techniques on mask acceptance. |

|

- GRADE |

In the context of surgery in children, no evidence was found regarding the effect of distraction techniques on separation anxiety.

|

|

- GRADE |

In the context of surgery in children, no evidence was found regarding the effect of distraction techniques on behavioral change. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Summary of literature

Description of studies

Virtual reality - Simonetti (2022) systematically reviewed clinical evidence to evaluate the effectiveness of virtual reality (VR) in the management of paediatric anxiety during the perioperative period, including whether VR improves anxiety-related postoperative outcomes such as pain, emergence delirium and postoperative maladaptive behaviours. The literature search was performed from January 2021 to June 2021, with no restriction on the date of publication. This systematic review included RCTs that investigated VR in management of anxiety during perioperative period, as a primary or secondary outcome in paediatric inpatients who took part in perioperative VR for elective surgery under general anaesthesia. Studies including patients who received anxiolytic premedication or with certain cognitive impairments were excluded. This systematic review included 7 monocentric RCT’s. The meta-analysis for studies in which the effect size for anxiety could be determined included 6 RCTs, which can be found in table 1. Differences in behavioural disturbances was assessed in 4 studies, however, with different instruments. For more details about the included studies, please see Simonetti (2022).

Table 1 Study characteristics of RCTs included in Simonetti (2022)

|

Author, year |

Patients (Age in years) |

Intervention

|

Control |

Instruments and outcome assessment |

Overall risk of bias |

|

Eijlers, 2019 |

N=191 Age: 4-12 |

Video of the operating room N=94

|

Usual care N=97 |

Anxiety: mYPAS at

Behavior child: CBCL at T1. |

Low

|

|

Ryu, 2017 |

N=70 Age: 4–10 |

VR video of the operating room 360° and the perioperative process N=34 |

Standard information regarding the process of anaesthesia and surgery N=35 |

Anxiety: mYPAS 30 min before anaesthesia induction (holding area).

Stressful behavior: PBRS: during GA induction |

High |

|

Jung, 2021 |

N=71 Age: 5-12 |

VR headset displayed interactive game N=33

|

Standard medical care without any audiovisual devices N=37 |

Anxiety: mYPAS at - T0 (baseline) - T1 (entering the operating room) - T2 (during induction of GA) |

High |

|

Park, 2019 |

N=80 Age: 4-10 |

Parental co-experience of preoperative VR tour through a mirroring display N = 40 |

VR-guided tour of the operating theatre via a smartphone and a head mounted display N=40 |

Anxiety: mYPAS at baseline – before induction of GA. |

Low |

|

Ryu, 2018 |

N=70 Age: 4-10 |

VR gaming N=35 |

Conventional mode of education about the preoperative process N=35 |

Anxiety: m-YPAS at baseline and before induction of GA.

Stressful behaviour child: PBRS: during induction of GA |

E*: Unclear |

|

Ryu, 2019 |

N=80 Age: 4-10 |

VR 360° immersive tour of the operating room N=41 |

Institution’s standard preoperative educational Procedure N=42 |

Anxiety: m-YPAS at baseline and before GA induction.

Postoperative behavior disturbance: PHBQ-AS by calling child’s parent on 1 and 14 days after surgery. |

F*: Some concerns |

VR: Virtual reality; mYPAS: modified Preoperative Anxiety Scale; GA: General anaesthesia

*Text and figure 2 are not in concordance and seem to be switched for Ryu 2018 and Ryu 2019.

Game-based interventions - Suleiman-Martos (2022) systematically reviewed clinical evidence to determine the effect of game-based interventions (via gamification or VR) during the induction of anaesthesia to reduce pain and anxiety in paediatric patients (<13 years). The literature search covered the period up to July 2021. This systematic review included 26 RCTs, of which 14 studies were included in the meta-analysis assessing anxiety with mYPAS of mYPAS-SF. The study characteristics of these studies can be found in table 2. For more details about the included studies, please see Suleiman-Martos (2022).

Table 2 Study characteristics of RCTs included in Suleiman-Martos (2022)

|

Author, year |

Patients (age in years) and surgery type |

Intervention

|

Control |

Anxiety assessment |

Overall risk of bias |

|

Buffel, 2019 |

N=20 Age: 6-10 Ambulatory surgery |

A serious game-CliniPup®(2 days play before surgery) N=12 |

No intervention N=8 |

mYPAS at induction |

High |

|

Chaurasia, 2019

|

N=80 Age: 4-8 Elective surgery |

Incentive-based game. Time before anaesthesia 1 day N=40 |

No intervention N=40

|

mYPAS at baseline and induction |

High |

|

Clausen, 2021

|

N=60 Age: 3-6 Elective minor |

Game on a tablet computer. Time before anaesthesia 20 min N=30 |

No intervention N=30

|

mYPAS at baseline and induction |

Some concerns |

|

Dwairej, 2020

|

N=128 Age: 5-11 Elective maxillofacial, dental or ENT |

Videogame Time before anaesthesia 20 min N=64 |

No intervention N=64 |

mYPAS at baseline and induction |

Some concerns |

|

Forouzandeh, 2020

|

N=172 Age: 3-12 Elective surgery |

IG1: N=64 interactive games IG2: N=55 painting Time before anaesthesia 20-30 min |

No intervention N=53 |

mYPAS at baseline and induction |

Some concerns |

|

Gao, 2014 |

N=59 Age: 3-6 F: Elective surgery |

Cartoons game. Time before anaesthesia 15–20 min N=29 |

No intervention N=30 |

mYPAS at baseline and induction |

High |

|

Huntington, 2018 |

N=176 Age: 5-7 Dental surgery |

IG1 video game N=60 IG2 placebo-video N=57 |

No intervention N=59 |

mYPAS at baseline and induction |

Low |

|

Lee, 2012

|

N=130 Age: 3-7 Elective surgery |

IG1 game N=44 IG2 cartoon N=42 |

No intervention N=44 |

mYPAS at baseline and induction |

Some concerns |

|

Marechal, 2017 |

N=115 Age: 4-11 Ambulatory surgery |

Tablet-game Time before anaesthesia 20 min N=60 |

Midazolam N=55 |

mYPAS at baseline and induction |

Some concerns |

|

Patel, 2006

|

N=112 Age: 4-12 Outpatient surgery |

IG1 parent presence + hand-held video game N=38 IG2: parent presence N=36 |

Midazolam N=38 |

mYPAS at baseline and induction |

Some concerns |

|

Rodriguez, 2019 |

N=52 Age: 4-10 Outpatient surgery |

Tablet game N=27 |

Bedside entertainment and relaxation theatre N=25 |

mYPAS at baseline and induction |

Low |

|

Scarano, 2021 |

N=50 Age: 4-12 Elective surgery |

Playing room Time before anaesthesia 30 min N=25 |

No intervention N=25 |

mYPAS at baseline and induction |

High |

|

Al-Nerabieah, 2020 |

N=64 Age: 6-10 Dental surgery |

A cartoon shows through VR eyeglasses in the waiting room. Time before anaesthesia 20 min. N=32 |

No intervention N=32 |

mYPAS-SF at baseline and induction

|

Some concerns |

|

Stewart, 2019 |

N=102 Age: 4-12 Ambulatory surgery |

Tablet-game. Time before anaesthesia 20 min N=51 |

Midazolam N=51 |

mYPAS-SF at baseline and induction |

High |

ENT, Ears, Nose and Throat surgery; mYPAS, Modified Yale; Preoperative Anxiety Scale; mYPAS-SF, Modified Yale Preoperative Anxiety Scale-Short Form; VR, Virtual reality.

Web-based health Interventions - Rantala (2020) systematically reviewed clinical evidence to evaluate the effectiveness of web-based mobile health interventions on paediatric patients and their parents in the context of day surgeries. The literature search covered the period up to December 2018. This systematic review included 8 RCTs with paediatric patients (age <18 years) in outpatient surgery, comparing web-based mobile health interventions delivered via the Internet or mobile platforms (all measured in the pre-operative period waiting for treatment) with standard care. The meta-analysis assessing anxiety included 6 studies, which can be found in table 3. For more details about the included studies, please see Rantala (2020).

Table 3 Study characteristics of RCTs included in Rantala (2020)

|

Author, year |

Patients (age in years) and surgery type |

Intervention

|

Control |

Anxiety assessment |

Overall risk of bias |

|

Fortier, 2015 |

N=82 Age: 2-7 Most frequent surgery types: Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy |

Active distractor WebTIPS tailored program comprising education, skills training, and interactive games to prepare children. Included parental site N=38. |

Control N=44 |

mYPAS |

Low |

|

Kerimoglu, 2013 |

N=9 Age: 4-9 Ambulatory surgery using GA.

|

Passive distractor. Video glasses connected to a portable media player for viewing television programmers N=32.

Midazolam and Video glasses connected to a portable media player for viewing television programmers N=32. |

Midazolam N=32 |

mYPAS |

Some concerns |

|

Marechal, 2017

|

N=115 Age: 4-10 Gut, urologic, ENT, eyes, and orthopedic. |

Active distractor N = 60. Tablet computer game. |

Midazolam N=55 |

mYPAS |

Low |

|

Mifflin, 2012 |

N=89 Age: 2-10 Ear, nose throat, urology, general surgery, dentistry, and other. |

Passive distractor N=42. Streamed video clips from YouTube™. |

Traditional distraction methods during induction N=47. |

mYPAS |

High |

|

Seiden, 2014 |

N=108 Age: 1-11 ENT, urology, general surgery, gastrointestinal, dental, or orthopedics. |

Active distractor N=57. Video games. |

Midazolam N=51 |

mYPAS |

Some concerns |

|

Stewart, 2018 |

N=102 Age: 4-12 General surgery, urology, otolaryngology, and other. |

Active distractor N=51. Tablet-based interactive Distraction, with gaming app. |

Midazolam N=51 |

mYPAS-SF |

Some concerns |

GA: General anaesthesia; mYPAS = modified Preoperative Anxiety Scale; STAI-C = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children; mYPAS-SF = modified Preoperative Anxiety Scale – Short Form

Audiovisual interventions - Chow (2016) systematically reviewed clinical evidence to synthesize and summarize evidence of the effects of AV interventions on reducing preoperative anxiety and its associated postoperative outcomes such as pain, postoperative maladaptive behaviours, recovery (e.g., decrease in discharge time) in children receiving elective surgery under general anesthesia. They also examined the acceptability and cost effectiveness of AV interventions. The literature search covered the period up to March 3, 2014. This systematic review included 18 studies, of which 10 studies were included in the meta-analysis of preoperative anxiety. These studies can be found in table 4. Eight of the studies used mYPAS, or STAI-C as measurement instrument and are used for this literature analysis. For more details about the included studies, please see Chow (2016).

Table 4 Study characteristics of RCTs included in Chow (2016)

|

Author, year

Study design |

Patients (age in years) and surgery type |

Intervention

|

Control |

Anxiety assessment |

Overall risk of bias |

|

Kain, 2001

RCT |

N=70 Age: 2-7 Elective outpatient Surgery |

Low-level light intensity + music + quietness in the room N=33 |

No intervention N=37 |

mYPAS at Entrance to the OR During induction |

High |

|

Kain, 2004

RCT |

N=123 Age: 3-7 Elective outpatient surgery |

Ia: Interactive music therapy before surgery N=51 Ib: Midazolam (n=34). |

SOC N=38 |

mYPAS during induction |

High |

|

Kain, 2007

RCT |

N=408 Age: 2-10 Elective outpatient Surgery |

Ia: ADVANCE. Program before surgery N=96 Ib: Parental Presence during Induction of Anesthesia N=94 Ic: Midazolam N=98 |

SOC N=99

|

mYPAS Holding area during induction |

High |

|

Karabulut & Duygu, 2009 Nonrandomized controlled study |

N=90 Age: 9-12 Inguinal hernia operation

|

Ia: Pre-op preparation Video N=30 Ib: Training with booklet N=30

|

No intervention N=30 |

STAI-C 48 hr before surgery 24 hr before surgery |

High |

|

Lee, 2012

RCT |

N=130 Age: 3-7 GA for elective surgery |

Ia: Animated cartoon using personal computers N=42 Ib: Toy N=44 |

SOC N=44 |

mYPAS Before surgery Holding area In the OR |

High |

|

Lee, 2013

RCT |

N=120 Age: 1-10 Elective surgery under GA |

Ia: Smartphone app N=40 Ib: Midazolam+smartphone app N=40 |

Midazolam N=40

|

mYPAS Holding area |

High |

|

O’Connor-Von, 2008

RCT |

N=69 Age: 10-16 Elective tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy |

Ia: Pre-op preparation Internet program N=28 |

C: Standard preparation N=14 Ca: Nontreatment group N=24 |

STAI-C Holding area |

High |

|

Patel, 2006

RCT |

N=112 Age: 4-12 Elective surgery under GA |

Ia: Parental presence + handheld video game N=38 Ib: Parental presence + Midazolam N=38 |

Parental presence N=36

|

mYPAS During induction |

Low |

|

Pinto & Hollandsworth, 1989

RCT

|

N=60 Age: 2-12 First-time elective surgery

|

Ia: Peer-narrated Pre-op preparation video with parents N=10 Ib: Peer-narrated Pre-op preparation video without parents N=10 Ic: Adult-narrated Pre-op preparation video with parents N=10 Id: Adult-narrated Pre-op preparation video without parents N=10 |

Ca: No videotape with parents N=10 Cb: No videotape without parents N=10 |

ORSA Night before surgery |

High |

|

Wakimizu, 2009

RCT

|

N=158 Age: 3-6 Elective herniorrhaphy for inguinal hernia and hydrocele testis |

Patient-educational modeling video and a booklet with regulations and guidelines N=77 |

SOC (Pre-op preparation video) N=81 |

FACES Before surgery |

Low |

GA: General anaesthesia; Ia = intervention; Ib = comparator I; Ic = comparator II; Id = comparator III; C = standard of care or no intervention; Ca = Control I; Cb = Control II; ORSA = Observer Rating Scale of Anxiety; FACES = FACES Rating Scale; STAI-C = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children; mYPAS = modified Preoperative Anxiety Scale.

Results

Anxiety score – Critical outcome

Measured with mYPAS:

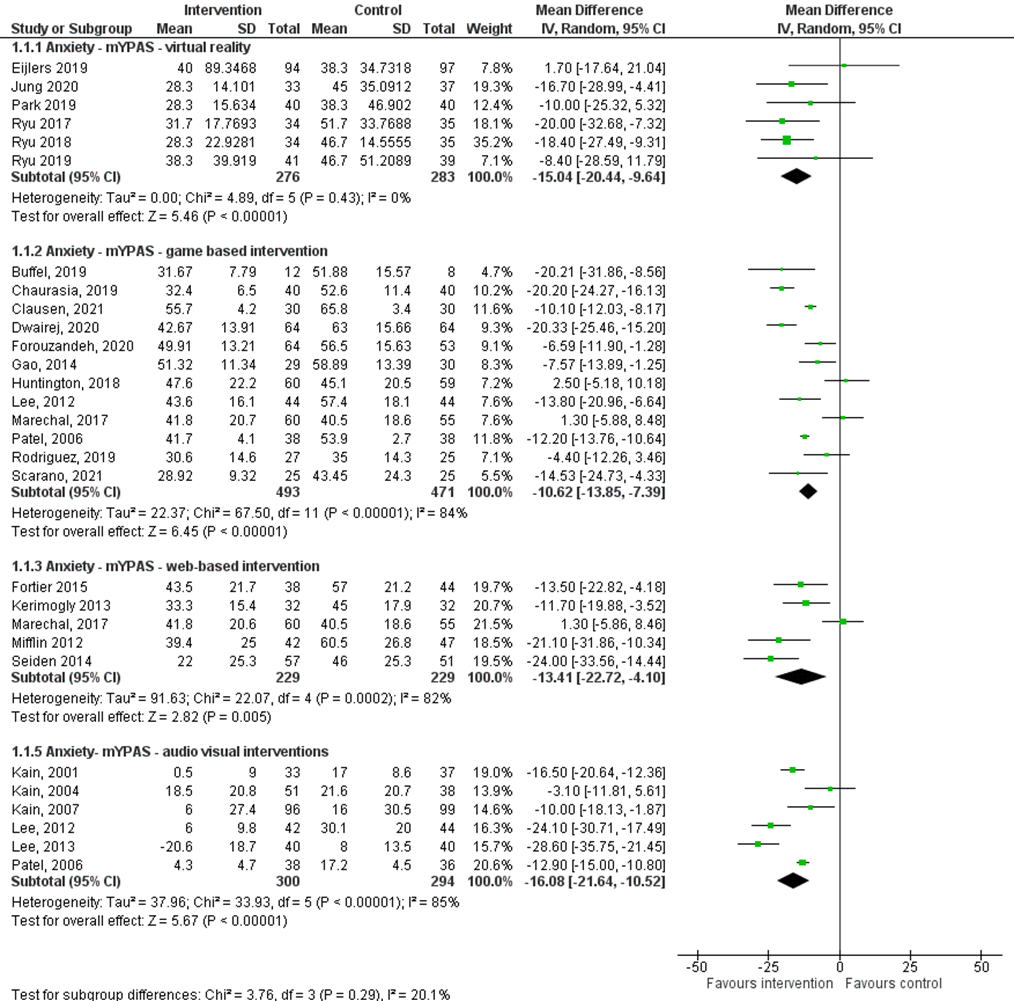

Six studies in the systematic review of Simonetti (2022) (Eijlers, 2019; Jung, 2020; Park, 2019; Ryu, 2017; Ryu, 2018; Ryu, 2019) reported the effect of VR on anxiety measured with mYPAS. The pooled mean difference is -15.04 (95%CI -20.44; -9.64) favoring intervention with VR (figure 1). This difference exceed the minimal clinically (patient) important difference of > 10 points.

Twelve studies in the systematic review of Suleiman-Martos (2022) (Buffel, 2019; Chaurasia, 2019; Clausen, 2021; Dwairej, 2020; Forouzandeh, 2020; Gao, 2014; Huntington, 2018; Lee, 2012; Marechal, 2017; Patel, 2006; Rodriguez, 2019; Scarano, 2021) reported the effect of game based interventions on anxiety measured with mYPAS. The pooled mean difference is -10.62 (95%CI -13.85; -7.39) favoring game based interventions (figure 1). This difference exceed the minimal clinically (patient) important difference of > 10 points.

Five studies in the systematic review of Rantala 2020 (Fortier, 2015; Kerimoglu, 2013; Marechal, 2017; Mifflin, 2012; Seiden, 2014) reported the effect of web based interventions on anxiety measured with mYPAS. The pooled mean difference is -13.41 (95%CI -22.72; -4.10) favoring web based intervention (figure 1). This difference exceed the minimal clinically (patient) important difference of > 10 points.

Six studies in the systematic review of Chow 2016 (Kain, 2001; Kain, 2004; Kain, 2007; Lee, 2012; Lee, 2013; Patel, 2006) reported the effect of audio visual interventions on anxiety measured with mYPAS. The pooled mean difference is -16.08 (95%CI -21.64; -10.52) favoring audio visual intervention (figure 1). This difference exceed the minimal clinically (patient) important difference of > 10 points.

Figure 1 Meta-analysis of the effect of distracting techniques on anxiety measured with mYPAS

Measured with mYPAS-SF:

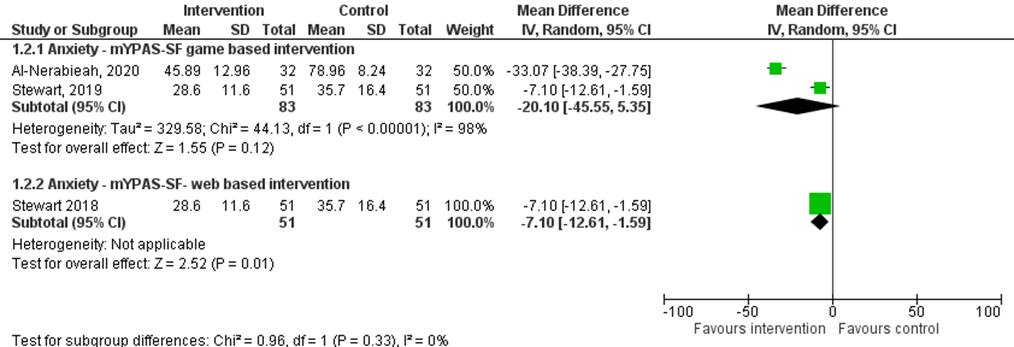

Two studies in the systematic review of Suleiman-Martos 2022 (Al-Nerabieah, 2020; Stewart, 2019) reported the effect of game based interventions on anxiety measured with mYPAS-SF. The pooled mean difference is -20.10 (95%CI -45.55; 5.35) favoring game based intervention (figure 2). This difference exceed the minimal clinically (patient) important difference of > 10 points.

One study in the systematic review of Rantala 2020 (Stewart 2018) reported the effect of web based intervention on anxiety measured with mYPAS-SF. The mean difference between the intervention and control group was -7.10 (95%CI -12.61; -1.59) favoring web based intervention (figure 2). This difference does not exceed the minimal clinically (patient) important difference of > 10 points.

Figure 2 Meta-analysis of the effect of distracting techniques on anxiety measured with mYPAS-SF

Measured with STAI-C:

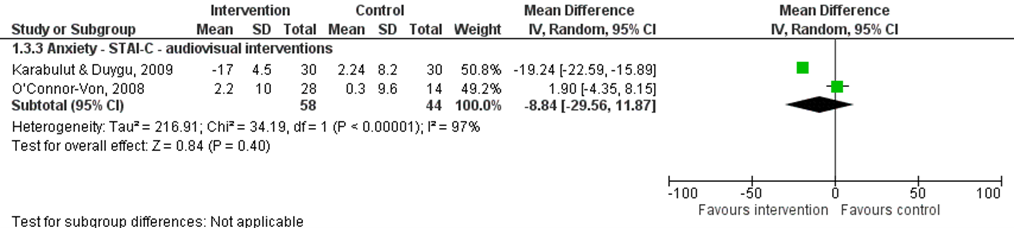

Two studies in the systematic review of Chow (2016) (Karabulut & Duygu, 2009; O’Connor-Von, 2008) reported the effect of audio visual interventions on anxiety measured with STAI-C. The pooled mean difference is –8.84 (95%CI -29.56; 11.87) favoring audio visual interventions (figure 3). This difference does not exceed the minimal clinically (patient) important difference of > 10 points.

Figure 3 Meta-analysis of the effect of distracting techniques on anxiety measured with STAI-C

Mask acceptance – Critical outcome:

The included systematic reviews did not report mask acceptance.

Separation anxiety – Important outcome:

The included systematic reviews did not report separation anxiety.

The included systematic reviews did not report mask acceptance.

Behavioral change – Important outcome:

Four studies in the systematic review of Simonetti (2022) (Eijlers, 2019; Ryu, 2017; Ryu, 2018; Ryu, 2019) assessed behavioral disturbances during the surgical procedure with different instruments. Therefore, it was not possible to pool the results of these studies. In general, postoperative behavioral disturbances did not differ between the two groups, except in Ryu (2017) which found lower PBRS scores for children in the intervention group (median 0; IQR 0-1) than in the usual care group (median 1; IQR 0–4) p = 0.010.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for all outcomes under this comparison was based on randomized studies and therefore starts at high.

Anxiety score

Virtual reality

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure anxiety score was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias); confidence interval crosses the threshold for a clinically relevant difference (imprecision).

Game based intervention

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure anxiety score was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias); strength of effect differs between studies (inconsistency).

Web based intervention

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure anxiety score was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias); strength of effect differs between studies (inconsistency); number of included patients (imprecision).

Audio visual intervention

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure anxiety score was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias); strength of effect differs between studies (inconsistency); number of included patients (imprecision).

Mask acceptance:

Virtual reality

The level of evidence was not assessed for the outcome mask acceptance, because of the lack of studies reporting this outcome.

Separation anxiety:

The level of evidence was not assessed for the outcome separation anxiety, because of the lack of studies reporting this outcome.

Behavioral change:

The level of evidence was not assessed for the outcome behavioral change, because it was not possible to pool the results of the studies reporting this outcome since they used different measurement instruments.

Zoeken en selecteren

Search and select

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effect of the use of distraction methods compared to no use of distraction methods in the context of surgery in children on separation anxiety, mask acceptance, anxiety score and behavioral change?

PICO1

| Patients: | children of all ages; |

| Intervention: | Virtual reality; |

| Control: | no use of distraction methods; |

| Outcome: | Anxiety score (e.g. measured using the mYPAS), mask acceptance, separation anxiety and behavioral changes. |

PICO2

| Patients: | children of all ages; |

| Intervention: | game based interventions; |

| Control: | no use of distraction methods; |

| Outcome: | anxiety score (e.g. measured using the mYPAS), mask acceptance, separation anxiety and behavioral changes. |

PICO3

| Patients: | children of all ages; |

| Intervention: | web-based interventions; |

| Control: | no use of distraction methods; |

| Outcome: |

anxiety score (e.g. measured using the mYPAS), mask acceptance, separation anxiety and behavioral changes. |

PICO4

| Patients: | children of all ages; |

| Intervention: | audio visual interventions; |

| Control: | no use of distraction methods; |

| Outcome: | anxiety score (e.g. measured using the mYPAS), mask acceptance, separation anxiety and behavioral changes. |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered anxiety score and mask acceptance as a critical outcome measure for decision making and separation anxiety (from parents) and behavioral change as an important outcome measure for decision making.

The working group defined a minimal clinically important difference as a difference of 10 points on the measurement instrument for the outcome anxiety. The working group defined 25% absolute difference, RR 0.8 < or > 1.25 as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for the outcomes mask acceptance, separation anxiety (from parents) and behavioral changes.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline/OVID and Embase were searched with relevant search terms from 2013 until April 03, 2023, for systematic reviews and RCTs about preoperative non-pharmacological interventions in children undergoing surgery. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 830 hits.

The systematic review was selected based on the following criteria:

• Minimum of two databases searched;

• Detailed search strategy with search date;

• In- and exclusion criteria;

• Evidence table for included studies;

• Risk of bias assessment per study;

• Intervention and Comparison according to the PICO;

• Study population according to the PICO.

55 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 51 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and four studies were included.

Results

Four systematic reviews were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Al-Nerabieah Z, Alhalabi M-N, Owayda A, Alsabek L, Bshara N, Kouchaji C. Effectiveness of using virtual reality eyeglasses in the waiting room on preoperative anxiety: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Perioper Care Oper Room Manage. 2020;21:100129. doi:10.1016/j.pcorm.2020.100129.

- Arabulut N, Duygu A. The effect of different training programs applied prior to surgical operation on anxiety levels. New Symposium Journal. 2009;47:64-69.

- Bray L, Carter B, Kiernan J, Horowicz E, Dixon K, Ridley J, Robinson C, Simmons A, Craske J, Sinha S, Morton L, Nafria B, Forsner M, Rullander AC, Nilsson S, Darcy L, Karlsson K, Hubbuck C, Brenner M, Spencer-Little S, Evans K, Rowland A, Hilliard C, Preston J, Leroy PL, Roland D, Booth L, Davies J, Saron H, Mansson ME, Cox A, Ford K, Campbell S, Blamires J, Dickinson A, Neufeld M, Peck B, de Avila M, Feeg V, Mediani HS, Atout M, Majamanda MD, North N, Chambers C, Robichaud F. Developing rights-based standards for children having tests, treatments, examinations and interventions: using a collaborative, multi-phased, multi-method and multi-stakeholder approach to build consensus. Eur J Pediatr. 2023 Oct;182(10):4707-4721. doi: 10.1007/s00431-023-05131-9. Epub 2023 Aug 11. PMID: 37566281; PMCID: PMC10587267.

- Buffel C, van Aalst J, Bangels AM, Toelen J, Allegaert K, Verschueren S, Vander Stichele G. A Web-Based Serious Game for Health to Reduce Perioperative Anxiety and Pain in Children (CliniPup): Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Serious Games. 2019 Jun 1;7(2):e12431. doi: 10.2196/12431. PMID: 31199324; PMCID: PMC6592396.

- Chaurasia B, Jain D, Mehta S, Gandhi K, Mathew PJ. Incentive-Based Game for Allaying Preoperative Anxiety in Children: A Prospective, Randomized Trial. Anesth Analg. 2019 Dec;129(6):1629-1634. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000003717. PMID: 31743184.

- Chow CH, Van Lieshout RJ, Schmidt LA, Dobson KG, Buckley N. Systematic Review: Audiovisual Interventions for Reducing Preoperative Anxiety in Children Undergoing Elective Surgery. J Pediatr Psychol. 2016 Mar;41(2):182-203. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv094. Epub 2015 Oct 17. PMID: 26476281; PMCID: PMC4884908.

- Clausen NG, Madsen D, Rosenkilde C, Hasfeldt-Hansen D, Larsen LG, Hansen TG. The Use of Tablet Computers to Reduce Preoperative Anxiety in Children Before Anesthesia: A Randomized Controlled Study. J Perianesth Nurs. 2021 Jun;36(3):275-278. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2020.09.012. Epub 2021 Feb 23. PMID: 33637409.

- Dwairej DA, Obeidat HM, Aloweidi AS. Video game distraction and anesthesia mask practice reduces children's preoperative anxiety: A randomized clinical trial. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2020 Jan;25(1):e12272. doi: 10.1111/jspn.12272. Epub 2019 Oct 1. PMID: 31576651.

- Eijlers R, Dierckx B, Staals LM, Berghmans JM, van der Schroeff MP, Strabbing EM, Wijnen RMH, Hillegers MHJ, Legerstee JS, Utens EMWJ. Virtual reality exposure before elective day care surgery to reduce anxiety and pain in children: A randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2019 Oct;36(10):728-737. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000001059. PMID: 31356373; PMCID: PMC6738544.

- Forouzandeh N, Drees F, Forouzandeh M, Darakhshandeh S. The effect of interactive games compared to painting on preoperative anxiety in Iranian children: A randomized clinical trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2020 Aug;40:101211. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101211. Epub 2020 Jun 19. PMID: 32891287.

- Fortier MA, Bunzli E, Walthall J, Olshansky E, Saadat H, Santistevan R, Mayes L, Kain ZN. Web-based tailored intervention for preparation of parents and children for outpatient surgery (WebTIPS): formative evaluation and randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2015 Apr;120(4):915-22. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000632. PMID: 25790213; PMCID: PMC4367120.

- Gao XL, Liu Y, Tian S, Zhang DQ, Wu QP. Effect of interesting games on relief of preoperative anxiety in preschool children. Int J Nurs Sci. 2014;1(1):89-92. doi:10.1016/j.ijnss.2014.02.002.

- Huntington C, Liossi C, Donaldson AN, Newton JT, Reynolds PA, Alharatani R, Hosey MT. On-line preparatory information for children and their families undergoing dental extractions under general anesthesia: A phase III randomized controlled trial. Paediatr Anaesth. 2018 Feb;28(2):157-166. doi: 10.1111/pan.13307. Epub 2017 Dec 27. PMID: 29280239; PMCID: PMC5814894.

- Jung MJ, Libaw JS, Ma K, Whitlock EL, Feiner JR, Sinskey JL. Pediatric Distraction on Induction of Anesthesia With Virtual Reality and Perioperative Anxiolysis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesth Analg. 2021 Mar 1;132(3):798-806. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005004. PMID: 32618627; PMCID: PMC9387568.

- Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Krivutza DM, Weinberg ME, Gaal D, Wang SM, Mayes LC. Interactive music therapy as a treatment for preoperative anxiety in children: a randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2004 May;98(5):1260-6, table of contents. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000111205.82346.c1. PMID: 15105197.

- Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Mayes LC, Weinberg ME, Wang SM, MacLaren JE, Blount RL. Family-centered preparation for surgery improves perioperative outcomes in children: a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2007 Jan;106(1):65-74. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200701000-00013. PMID: 17197846.

- Kain ZN, Wang SM, Mayes LC, Krivutza DM, Teague BA. Sensory stimuli and anxiety in children undergoing surgery: a randomized, controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2001 Apr;92(4):897-903. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200104000-00018. PMID: 11273921.

- Kerimoglu B, Neuman A, Paul J, Stefanov DG, Twersky R. Anesthesia induction using video glasses as a distraction tool for the management of preoperative anxiety in children. Anesth Analg. 2013 Dec;117(6):1373-9. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182a8c18f. PMID: 24257388.

- Lee J, Lee J, Lim H, Son JS, Lee JR, Kim DC, Ko S. Cartoon distraction alleviates anxiety in children during induction of anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2012 Nov;115(5):1168-73. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31824fb469. Epub 2012 Sep 25. PMID: 23011563.

- Lee JH, Jung HK, Lee GG, Kim HY, Park SG, Woo SC. Effect of behavioral intervention using smartphone application for preoperative anxiety in pediatric patients. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2013 Dec;65(6):508-18. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2013.65.6.508. Epub 2013 Dec 26. PMID: 24427456; PMCID: PMC3888843.

- Leroy PLJM (2021). Van trauma naar vertrouwen - Praktische Pediatrie. In: Prakt. Pediatr. Beschikbaar via: https://www.praktischepediatrie.nl/tijdschrift-elearning/editie/artikel/t/van-trauma-naar-vertrouwen. Geraadpleegd op 28-02-2024.

- Leroy PL, Costa LR, Emmanouil D, van Beukering A, Franck LS. Beyond the drugs: nonpharmacologic strategies to optimize procedural care in children. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2016 Mar;29 Suppl 1:S1-13. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000312. PMID: 26926330.

- Marechal C, Berthiller J, Tosetti S, Cogniat B, Desombres H, Bouvet L, Kassai B, Chassard D, de Queiroz Siqueira M. Children and parental anxiolysis in paediatric ambulatory surgery: a randomized controlled study comparing 0.3?mg kg-1 midazolam to tablet computer based interactive distraction. Br J Anaesth. 2017 Feb;118(2):247-253. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew436. PMID: 28100529.

- Mifflin KA, Hackmann T, Chorney JM. Streamed video clips to reduce anxiety in children during inhaled induction of anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2012 Nov;115(5):1162-7. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31824d5224. Epub 2012 Oct 9. PMID: 23051880.

- O'Conner-Von S. Preparation of adolescents for outpatient surgery: using an Internet program. AORN J. 2008 Feb;87(2):374-98. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2007.07.024. PMID: 18262002.

- Park JW, Nahm FS, Kim JH, Jeon YT, Ryu JH, Han SH. The Effect of Mirroring Display of Virtual Reality Tour of the Operating Theatre on Preoperative Anxiety: A Randomized Controlled Trial. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2019 Nov;23(6):2655-2660. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2019.2892485. Epub 2019 Jan 11. PMID: 30640637.

- Patel A, Schieble T, Davidson M, Tran MC, Schoenberg C, Delphin E, Bennett H. Distraction with a hand-held video game reduces pediatric preoperative anxiety. Paediatr Anaesth. 2006 Oct;16(10):1019-27. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2006.01914.x. PMID: 16972829.

- Pinto RP, Hollandsworth JG Jr. Using videotape modeling to prepare children psychologically for surgery: influence of parents and costs versus benefits of providing preparation services. Health Psychol. 1989;8(1):79-95. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.8.1.79. PMID: 2495936.

- Rantala A, Pikkarainen M, Miettunen J, He HG, Pölkki T. The effectiveness of web-based mobile health interventions in paediatric outpatient surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Adv Nurs. 2020 Aug;76(8):1949-1960. doi: 10.1111/jan.14381. Epub 2020 Apr 22. PMID: 32281673.

- Rodriguez ST, Jang O, Hernandez JM, George AJ, Caruso TJ, Simons LE. Varying screen size for passive video distraction during induction of anesthesia in low-risk children: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Paediatr Anaesth. 2019 Jun;29(6):648-655. doi: 10.1111/pan.13636. Epub 2019 Apr 14. PMID: 30916447.

- Ryu JH, Oh AY, Yoo HJ, Kim JH, Park JW, Han SH. The effect of an immersive virtual reality tour of the operating theater on emergence delirium in children undergoing general anesthesia: A randomized controlled trial. Paediatr Anaesth. 2019 Jan;29(1):98-105. doi: 10.1111/pan.13535. Epub 2018 Nov 25. PMID: 30365231.

- Ryu JH, Park JW, Nahm FS, Jeon YT, Oh AY, Lee HJ, Kim JH, Han SH. The Effect of Gamification through a Virtual Reality on Preoperative Anxiety in Pediatric Patients Undergoing General Anesthesia: A Prospective, Randomized, and Controlled Trial. J Clin Med. 2018 Sep 17;7(9):284. doi: 10.3390/jcm7090284. PMID: 30227602; PMCID: PMC6162739.

- Ryu JH, Park SJ, Park JW, Kim JW, Yoo HJ, Kim TW, Hong JS, Han SH. Randomized clinical trial of immersive virtual reality tour of the operating theatre in children before anaesthesia. Br J Surg. 2017 Nov;104(12):1628-1633. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10684. Epub 2017 Oct 4. PMID: 28975600.

- Scarano F, Dalla Corte A, Michielon R, Gava A, Midrio P. Application of a non-pharmacological technique in addition to the pharmacological protocol for the management of children's preoperative anxiety: A 10 years' experience. Pediatr Med Chir. 2021 Mar 19;43(1). doi: 10.4081/pmc.2021.235. PMID: 33739059.

- Seiden SC, McMullan S, Sequera-Ramos L, De Oliveira GS Jr, Roth A, Rosenblatt A, Jesdale BM, Suresh S. Tablet-based Interactive Distraction (TBID) vs oral midazolam to minimize perioperative anxiety in pediatric patients: a noninferiority randomized trial. Paediatr Anaesth. 2014 Dec;24(12):1217-23. doi: 10.1111/pan.12475. Epub 2014 Jul 17. PMID: 25040433.

- Simonetti V, Tomietto M, Comparcini D, Vankova N, Marcelli S, Cicolini G. Effectiveness of virtual reality in the management of paediatric anxiety during the peri operative period: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022 Jan;125:104115. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104115. Epub 2021 Oct 23. PMID: 34781118.

- Stewart B, Cazzell MA, Pearcy T. Single-Blinded Randomized Controlled Study on Use of Interactive Distraction Versus Oral Midazolam to Reduce Pediatric Preoperative Anxiety, Emergence Delirium, and Postanesthesia Length of Stay. J Perianesth Nurs. 2019 Jun;34(3):567-575. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2018.08.004. Epub 2018 Nov 7. PMID: 30413359.

- Suleiman-Martos N, García-Lara RA, Membrive-Jiménez MJ, Pradas-Hernández L, Romero-Béjar JL, Dominguez-Vías G, Gómez-Urquiza JL. Effect of a game-based intervention on preoperative pain and anxiety in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Nurs. 2022 Dec;31(23-24):3350-3367. doi: 10.1111/jocn.16227. Epub 2022 Jan 24. PMID: 35075716; PMCID: PMC9787560.

- Wakimizu R, Kamagata S, Kuwabara T, Kamibeppu K. A randomized controlled trial of an at-home preparation programme for Japanese preschool children: effects on children's and caregivers' anxiety associated with surgery. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009 Apr;15(2):393-401. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01082.x. PMID: 19335503.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Simonetti, 2022

Individual study characteristics deduced from Simonetti, 2022.

Study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of 6 RCTs to answer our clinical question.

Literature search performed from January 2021 to June 2021

A: Eijlers, 2019 B: Ryu, 2017 C: Jung, 2021 D: Park, 2019 E: Ryu, 2018 F: Ryu, 2019

Study design: Single blind RCT: A Parallel group RCT: C RCT: B, D, E, F

Setting and Country: A. Elective inpatient surgery. Sophia Children’s Hospital, Holland, March 2017 – Oct 2018 B. Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Korea, Jan – April 2017. C. San Fransisco Benioff Children’s Hospital, University of California, USA, August 2018 – March 2019 D. Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Korea, Jan – Feb 2018 E. Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Korea, Feb – April 2018 F. Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Korea, June – Oct 2017

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Systematic review:

|

Inclusion criteria SR: RCTs; Virtual reality in management of anxiety during perioperative period, as a primary or secondary outcome; paediatric inpatients age < 19 yrs, including the following age groups: 4–5 yrs, 6–12, and 13–19 who took part in perioperative virtual reality for elective surgery under general anaesthesia.

Exclusion criteria SR: Including patients who received anxiolytic premedication or with certain cognitive impairments.

7 studies included, effect size for anxiety could be determined in 6 studies.

N, age In years A: N=191, 4-12 B: N=70, 4–10 C. N=71, 5-12 D: N=80, 4-10 E. N=70, 4-10 F. N=80, 4-10

Groups were comparable at baseline. |

Virtual reality in the management of anxiety during the perioperative period, either as a primary or a secondary outcome

A: Virtual reality exposure (video of the operating room in two versions: 4–7 yrs and 8–12 yrs).) in preparing children for elective inpatient surgery. HTC Vive visor, monitor PC N=94. B: Samsung Gear headset and smartphone Galaxy S6®; Samsung). VR video of the operating room (360°) and the perioperative process. (N = 34). C. Immersive audiovisual distraction with a virtual reality headset during general anaesthesia induction. Samsung Gear VR headset displayed interactive game (software ChariotVR) designed for paediatric preoperative use (N=33). D: Parental co-experience of preoperative VR tour through a mirroring display. Samsung Gear Visor and smartphone (Galaxy S6®; Samsung), Samsung mirroring device Smart Mirroring 2.0 SE. Mirroring devices mirror the same content of the video onto a monitor display to provide the same tour to their parents (N = 40). E: Gamification of the preoperative process using virtual reality gaming. Oculus Rift Headset, hand and finger motion controller - Leap motion controller (N = 35). F: Samsung Gear e smartphone (Galaxy S6®; Samsung). Virtual reality 360° immersive tour of the operating room (N=41).

|

A: Usual care (N=97). B: Standard information regarding the process of anaesthesia and surgery (N=35). C. Standard medical care without any audiovisual devices (N=37). D: Virtual reality-guided tour of the operating theatre via a smartphone (Galaxy S6®, Samsung, Suwon, Korea) and a head mounted display (VR Gear®; Samsung) (N=40). E: Conventional mode of education about the preoperative process. (N=35). F: Institution’s standard preoperative educational Procedure (N=42). |

Instruments and time points of outcome assessment:

A: Anxiety: mYPAS at -T1 (baseline) -T2 (holding area) -T3 (during induction of GA) Behavior child: CBCL at T1. B: Anxiety: mYPAS 30 min before anaesthesia induction (holding area). Stressful behavior: PBRS: during general anaesthesia induction. C. Anxiety: m-YPAS at T0 (baseline) - T1 (entering the operating room) - T2 during induction of general anaesthesia. D: Anxiety: m-YPAS at baseline – before induction of general anaesthesia. E: Anxiety: m-YPAS at baseline and before induction of general anaesthesia. Stressful behaviour child: PBRS: during induction of general anaesthesia F: Anxiety: m-YPAS at baseline and before GA induction. Postoperative behavior disturbance: PHBQ-AS by calling child’s parent on 1 and 14 days after surgery. |

Anxiety (N=6) Anxiety levels in children undergoing surgery assessed using the Modified Yale Preoperative Anxiety Scale (mYPAS).

Standardized effect measure [95% CI]: A: 0.000 [−0.284; 0.284 Weight: 25.43] B: −0.493 [−0.972; −0.014 Weight: 14.31] C: −0.591 [−1.070; −0.111 Weight: 14.30] D: −0.353 [−0.795; 0.089 Weight: 15.92] E: −0.717 [−1.204; −0.230 Weight: 14.00] F: −0.181 [−0.620; 0.258 Weight: 16.03]

Pooled effect (random effects model: −0.341 [95% CI −0.620 to−0.107] favoring the intervention group. Heterogeneity (I2): 38.64%, [95%CI: 0.00–75.62).

Behavioral disturbances (N=4): Behavioral disturbances during the surgical procedure assessed with different instruments.

In general, postoperative behavioral disturbances did not differ between the two groups, except in B. which found lower PBRS scores for children in the intervention group (median 1; IQR 0-4) than in the usual care group (median 0; IQR 0–1) p = 0.010. |

Risk of bias: Tool used by authors: Simonetti, 2022

A: Low B: High (high risk for similar baseline outcome measurement and uncertain similar baseline characteristics). C: High (regarding: knowledge of the allocation interventions and the random sequence generation was unclearly reported) D: Low E*: Unclear (Unclear similar baseline characteristics) F*: Some concerns (Unclear similar baseline characteristics) *Text and figure 2 are not in concordance and seem to be switched for Ryu 2018 and Ryu 2019.

Author’s conclusion In conclusion, our systematic review and meta-analysis showed that children undergoing elective surgery benefit from virtual reality as a distraction method that reduces anxiety. A consensus for secondary outcomes of pain, behavioral disturbances, emergence delirium and compliance could not be obtained. Research that uses the same methods, instruments and devices is needed to compare the efficacy of virtual reality and to better understand its applications in clinical practice.

Level of evidence GRADE: Anxiety: LOW** *Downgraded 1 point because of limitations in study design: Blinding of the participants was not applicable since the intervention involved the use of a virtual reality device; Unclear whether baseline characteristics were similar; Most of the articles included in this review were conducted in the same Country (Korea).

** Downgraded 1 point because of imprecision: confidence interval crosses the threshold for a clinically relevant difference.

|

|

Suleiman-Martos, 2022

Individual study characteristics deduced from Suleiman-Martos, 2022

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of 14 RCTs to answer our clinical question.

Literature search up to July 2021.

A: Buffel, 2019 B: Chaurasia, 2019 C: Clausen, 2021 D: Dwairej, 2020 E: Forouzandeh, 2020 F: Gao, 2014 G: Huntington, 2018 H: Lee, 2012 I: Marechal, 2017 J: Patel, 2006 K: Rodriguez, 2019 L: Scarano, 2021 M: Al-Nerabieah, 2020 N: Stewart, 2019

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: (ophthalmology, urology, orthopaedic, general), India C: Elective minor (abdominal and urologic surgery), Denmark D: Elective maxillofacial, dental or ENT, Jordan E: Elective surgery, Iran F: Elective surgery, China G: Dental surgery, England H: Elective surgery (ENT, ophthalmology, orthopaedic), South Korea I: Ambulatory surgery (urology, ENT, orthopaedic, ophthalmology), France K: Outpatient surgery (ENT, plastics, urology, ophthalmology, orthopaedics, rheumatology, general), USA L: Elective surgery, Italy M: Dental surgery, Syria N: Ambulatory surgery (urology, ENT, ophthalmology, general), USA

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Systematic review:

|

Inclusion criteria SR: Randomised controlled trials with children (up to 12 years of age); intervention: Interactive game, gamification or virtual game before surgery; Control group: traditional intervention, usual medication, no distraction aids or other intervention; outcomes anxiety and pain.

26 studies included, 14 studies were included in the meta-analysis assessing anxiety with mYPAS or mYPAS-SF.

N, mean age A: N=20 patients, 6-10 yrs B: N=80, 4-8 yrs C: N=60, 3-6 yrs D: N=128, 5-11 yrs E: N=172, 3-12 yrs F: N=59, 3-6 yrs G: N=176, 5-7 yrs H: N=130, 3-7 yrs I: N=115, 4-11 yrs J: N=112, 4-12 yrs K: N=52, 4-10 yrs L: N=50, 4-12 yrs M: N=64, 6-10 yrs N: N=102, 4-12 yrs

Groups were comparable at baseline. |

Intervention: Interactive game, gamification or virtual game before surgery

Intervention: A: A serious game-CliniPup ®(2 days play prior to surgery) (N=12) B: Incentive-based game. Time before anaesthesia 1 day (N=40) C: Game on a tablet computer. Time before anaesthesia 20 min (N=30) D: Videogame Time before anaesthesia 20 min (N=64) E: IG1: interactive games (N=64) IG2: painting (N=55) Time before anaesthesia 20–30 min F: cartoons game Time before anaesthesia 15–20 min (N=29) G: IG1 video game (N=60) IG2 placebo-video (N=57) H: IG1 game (N=44) IG2 cartoon (N=42) I: tablet-game Time before anaesthesia 20 min (N=60) J: IG1 parent presence + hand-held video game (N=38) IG2: parent presence (N=36) K: Tablet game (1.17–7.64 Min play) (N=27) L: Playing room Time before anaesthesia 30 min (N=25) M: A cartoon shows through VR eyeglasses in the waiting room (5 min play). Time before anaesthesia 20 min (N=32) N: Tablet-game Time before anaesthesia 20 min (N=51)

|

Control: A: No intervention (N=8) B: No intervention (N=40) C: No intervention (N=30) D: No intervention (N=64) E: No intervention (N=53) F: No intervention (N=30) G: No intervention (N=59) H: No intervention (N=44) I: Midazolam (N=55) J: Midazolam (N=38) K: Bedside entertainment and relaxation theatre (N=25) L: No intervention (N=25) M: No intervention (N=32) N: Midazolam (N=51)

|

Instruments and time points of outcome assessment:

A: mYPAS at induction B: mYPAS at baseline and induction C: mYPAS at baseline and induction D: mYPAS at baseline and induction E: mYPAS at baseline and induction F: mYPAS at baseline and induction G: mYPAS at baseline and induction H: mYPAS at baseline and induction I: mYPAS at baseline and induction K: mYPAS at baseline and induction L: mYPAS at baseline and induction M: mYPAS-SF at baseline and induction N: mYPAS-SF at baseline and induction

|

Anxiety Measured using mYPAS Effect measure: mean difference [95% CI]:

A: -20.21 [-31.86, -8.56] B: -20.20 [-24.27, -16.13] C: -10.10 [-12.03, -8.17] D: -20.33 [-25.46, -15.20] E: -6.59 [-11.90, -1.28] F: -7.57 [-13.89, -1.25] G: 2.50 [-5.18, 10.18] H: -13.80 [-20.96, -6.64] I: 1.30 [ -5.88, 8.48] K: -4.40 [-12.26, 3.46] L: -14.53 [-24.73, -4.33]

Pooled effect (random effects model): -10.62 [95% CI -13.85 to -7.39] favoring the intervention group. Heterogeneity (I2): 84%

Measured using mYPAS-SF Effect measure: mean difference [95% CI]: M: -33.07 [-38.39 to -27.75] N: -7.10 [-12.61, -1.59] Pooled effect (random effects model): -20.10 [95% CI -45.55 to 5.35] favoring the intervention group Heterogeneity (I2): 98%

Of the 12 studies not included in the meta-analyses, 10 reported a significant reduction in preoperative anxiety after a game-based intervention as a distraction method (Buyuk et al., 2021; Dehghan et al., 2019; Hashimoto et al., 2020; Hosseinpour & Memarzadeh, 2010; Jung et al., 2021; Matthyssens et al., 2020; Park et al., 2019; Ryu et al., 2019; Seiden et al., 2014; Ünver et al., 2020).

Two studies (Eijlers, Dierckx, et al., 2019; Uyar et al., 2020) found no beneficial effect on anxiety from this intervention.

|

Risk of bias: Tool used by authors: Suleiman-Martos, 2022

A: High (high risk with regard to blinding of participants and personnel/performance bias; unclear other bias) B: High (high risk with regard to blinding of participants and personnel/performance bias, unclear selective reporting/reporting bias) C: Some concerns (unclear other bias) D: Some concerns (high risk with regard to blinding of participants and personnel/performance bias) E: Some concerns (unclear allocation concealment/selection bias, unclear blinding of participants and personnel/performance bias) F: High (unclear allocation concealment/selection bias, high risk with regard to blinding of participants and personnel/performance bias) G: Low H: Some concerns (high risk with regard to blinding of participants and personnel/performance bias) I: Some concerns (high risk with regard to blinding of participants and personnel/performance bias) J: Some concerns (unclear allocation concealment/selection bias, unclear blinding of participants and personnel/performance bias) K: Low L: High (high risk with regard to allocation concealment/selection bias, unclear blinding of participants and personnel/performance bias) M: Some concerns (high risk with regard to blinding of participants and personnel/performance bias) N: High (unclear incomplete outcome data, high risk of selective reporting/reporting bias)

Author’s conclusion Game-based interventions have a positive impact, reducing preoperative anxiety in children before and during the induction of anaesthesia, although our analysis detected no significant impact on pain levels. This innovative and pleasurable type of intervention can be helpful in the care of paediatric surgical patients, alleviating pain and anxiety during preoperative care. This task is often challenging for nursing professionals, and game-based strategies could help them provide positive attention in paediatric care, benefiting children's emotional health and post-surgery recovery. However, such distraction-based interventions need further development to optimise surgical pathways in preoperative and postoperative settings for the paediatric patient.

Level of evidence GRADE: Anxiety: VERY LOW** *Downgraded 1 point because of limitations in study design (most of the studies with regard to blinding of the participants).

** Downgraded 1 point because of inconsistency (strength of effect differs between studies).

*** Downgraded 1 point because of imprecision (N total <2000). |

|

Rantala, 2020

[individual study characteristics deduced from Rantala, 2020]

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of 6 RCTs to answer our clinical question.

Literature search up to December 2018

A: Fortier, 2015 B: Kerimoglu, 2013 C: Marechal, 2017 D: Mifflin, 2012 E: Seiden, 2014 F: Stewart, 2018

Study design: RCT (parallel and multi-arm)

Setting and Country: A: Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy most frequent surgery types. Two medical centers in California USA. Aug 2011 - Aug 2012 B: Ambulatory surgery using general anaesthesia. IRBs at SUNY Downstate Medical Center and its affiliate Long Island College Hospital. New York USA. July 2009 - Aug 2011 C: Gut and urologic, ENT, eyes, and orthopedic. Children's Hospital of the University of Lyon, France. May 2013 - Mar 2014 D: Ear, nose throat, urology, general surgery, dentistry, and other. Canada E: ENT, urology, general surgery, gastrointestinal, dental, or orthopedics. The Children's Hospital of Chicago, USA. Feb 2013 -June 2013 F: General surgery, urology, otolaryngology, and other. Texas, USA. Feb 2016 - Sept 2016

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Systematic review:

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

8 studies included, of which 6 included in the meta-analysis assessing anxiety.

N, mean age A: N=82, 2-7 yrs B: N=96, 4-9 yrs C: N=115, 4-10 yrs D: N=89, 2-10 yrs E: N=108, 1-11 yrs F: N=102, 4-12 yrs

Groups were comparable at baseline. |

Intervention:

A: Active distractor (N=38) WebTIPS tailored program comprising education, skills training, and interactive games to prepare children. Included parental site. B: Passive distractor. Video glasses connected to a portable media player for viewing television programmers (N = 32). Midazolam and Video glasses connected to a portable media player for viewing television programmers (N = 32). C: Active distractor (N = 60) Tablet computer game (TAB) appropriate for according to age and to their preferences. D: Passive distractor (N = 42) Streamed video clips from YouTube™. E: Active distractor (N = 57) Age-appropriate video games. F: Active distractor (N = 51) Tablet-based interactive Distraction, iPad mini with an age-appropriate gaming app for 1 min. |

Control: A: Control (N=44) B: Midazolam (N=32) C: Midazolam (N=55) D: Traditional distraction methods during induction (N=47) E: Midazolam (N=51) F: Midazolam (N=51)

|

Instruments: A: mYPAS B: mYPAS C: mYPAS D: mYPAS E: mYPAS F: mYPAS-SF

|

Anxiety: Anxiety at induction, as measured by mYPAS.

Effect measure: Mean difference [95% CI]: A: 0.63 [0.18 – 1.07] B: 0.70 [0.20 – 1.21] C: -0.07 [-0.43 – 0.30] D: 0.81 [0.38 – 1.25] E: 0.95 (0.55 – 1.35) F: 0.50 (0.11–0.89)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.58 [95% CI 0.26 to 0.89] favoring the intervention. Heterogeneity (I2): 70.0%

Anxiety at induction, as measured by mYPAS after sensitivity analyses (excluding a study with a differing effect (influence analysis): Effect measure: Mean difference [95% CI]: A: 0.63 (0.18 – 1.07) B: 0.70 [0.20 – 1.21] C: -0.07 [-0.43 – 0.30] D: 0.81 [0.38 – 1.25] E: 0.95 (0.55 – 1.35) F: 0.50 (0.11 – 0.89)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.72 [95% CI 0.53 to 0.91] favoring the intervention. Heterogeneity (I2): 0.0%

|

Risk of bias: Tool used by authors, Rantala 2020: A: Low (knowledge of allocated intervention was not adequately prevented and unclear protection against contamination) B: Some concerns (unclear: incomplete outcome data/attrition bias; knowledge of allocated intervention was not adequately prevented and unclear protection against contamination) C: Low (knowledge of allocated intervention was not adequately prevented and unclear protection against contamination) D: High (unclear: incomplete outcome data/attrition bias; knowledge of allocated intervention was not adequately prevented and unclear protection against contamination; unclear selective reporting/reporting bias; and unclear other bias) E: Some concerns (unclear: incomplete outcome data/attrition bias; knowledge of allocated intervention was not adequately prevented and unclear protection against contamination) F: Some concerns (unclear: incomplete outcome data/attrition bias; knowledge of allocated intervention was not adequately prevented and unclear protection against contamination)

Author’s conclusion: The results of the current systematic review, which included a meta-analysis of six studies, indicate that web-based mobile interventions are an effective nonpharmacological distraction tool for reducing children's pre-operative anxiety in the context of day surgery. These tools can also increase parental satisfaction regarding separation from their children in the pre-operative setting and anaesthesia procedure. We recommend that these kinds of interventions should be used as safe and easy non-pharmacological distraction tools that can help children deal with reducing their anxiety. However, there is little evidence of the effectiveness of reducing children's postoperative pain and parental anxiety using similar interventions. There is still a need for further interventions that cover the whole paediatric patient surgical pathway, including pre-, intra-, and postoperative settings. There is also a need for more tailored, educational web-based mobile health interventions in the hospital environment.

Level of evidence GRADE: Anxiety: VERY LOW*** *Downgraded 1 point because of limitations in study design (risk of bias).

** Downgraded 1 point because of inconsistency (strength of effect differs between studies).

*** Downgraded 1 point because of imprecision (N total <2000).

|

|

Chow, 2016

Individual study characteristics deduced from Chow, 2016

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of 10 RCTs to answer our clinical question.

Literature search up to March 3, 2014.

A: Kain, 2001 B: Kain, 2004 C: Kain, 2007 D: Karabulut & Duygu, 2009 E: Lee, 2012 F: Lee, 2013 G: O’Connor-Von, 2008 H: Patel, 2006 I: Pinto & Hollandsworth, 1989 J: Wakimizu, 2009

Study design:

Setting and Country: A: Elective outpatient Surgery, USA B: Elective outpatient surgery, USA C: Elective outpatient Surgery, USA D: Inguinal hernia operation, Turkey E: General anesthesia for elective surgery, South Korea F: Elective surgery under general anesthesia, South Korea G: Elective tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy, USA H: Elective surgery under general anesthesia, USA I: First-time elective surgery, USA J: Elective herniorrhaphy for inguinal hernia and hydrocele testis, Japan

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Systematic review:

Scholarship (The Dalley Fellowships) awarded to first author C.C.

|

Inclusion criteria SR: Including children < age 18 years receiving elective surgery under general anesthesia in community, research, and University affiliated hospitals, where AV interventions were used as experimental treatments, with a minimum of two comparison arms per study and children’s anxiety reported as the primary outcome.

18 studies included, of which 10 studies included in the meta-analysis.

N, mean age, ethnicity A: N=70, 2-7 yrs, N/S B: N=123, 3-7 yrs, N/S C: N=408, 2-10 yrs, 80 non-white D: N=90, 9-12 years, N/S E: N=130, 3-7 yrs, N/S F: N=120, 1-10 yrs, N/S G: N=69 , 10-16 yrs, 89% white H: N=112, 4-12 yrs, N/S I: N=60, 2-12 yrs J: N=158, 3-6 yrs, N/S

N/S: not specified

Groups were comparable at baseline.

|

Intervention: AV interventions were defined as involving any audio, visual, or AV components that aimed to reduce preoperative anxiety in children (e.g., videos, video games, Internet programs, music).

A: Low sensory stimuli Before anesthetic Induction. Low-level light intensity (200 LX) + music + quietness in the room (only one attending anesthesiologist to interact with the child during the induction of anesthesia) (N=33) B: Ia: Interactive music therapy. Music 30 min before surgery (n=51). Ib: Midazolam (n=34). C: Ia: ADVANCE. Program Up to 7 days before surgery (n=96) Ib: Parental Presence during Induction of Anesthesia (n=94) Ic: Midazolam (n=98) D: Ia: A 12-min pre-op preparation Video Compact Disc (VCD) Same day as surgery (n=30) Ib: Training with booklet (n=30) E: Ia: Animated cartoon using personal computers N/S (n=42) Ib: Toy (n=44) F: Ia: Smartphone app (n=40) Ib: Midazolam + smartphone app (n=40) Smartphone game app>5 min to surgery G: Ia: Pre-op preparation Internet program <72 hr to surgery (n=28) H: Ia: Parental presence + handheld video game. Videogame>20 min to Surgery (n=38) Ib: Parental presence + Midazolam (n=38) I: A 22-min videotape depicts an 8-year-old boy who was being hospitalized for surgery narrated by child (or adult) 1 hr before admission. Ia: Peer-narrated Pre-op preparation video with parents (n=10) Ib: Peer-narrated Pre-op preparation video without parents (n=10) Ic: Adult-narrated Pre-op preparation video with parents (n=10) Id: Adult-narrated Pre-op preparation video without parents (n=10) J: Patient-educational modeling video 7 days before surgery, which introduced the experience of a 5-year-old boy who is hospitalized for hernia and a booklet with regulations and guidelines to use as frequently as they want at home (n=77). |

Comparison: Comparator groups could be a control group that received standard of care (SC), no-intervention, parental presence, or low doses of sedative premedication (e.g., midazolam).

The definition of SC varied between studies but was generally defined as the routine preparation (i.e., brief explanations of the medical procedures) provided by the nurses and/or physicians during the preoperative period.

A: No intervention (N=37) B: Standard of care (n=38) C: Standard of care (n=99) D: No intervention (n=30) E: Standard of care (n=44) F: Midazolam (n=40) G: C: Standard hospital preparation program (n=14) Ca: Nontreatment group (n=24) H: Parental presence (n=36) I: Ca: No videotape with parents (n=10) Cb: No videotape without parents (n=10) J: Standard of care (Pre-op preparation video) (n=81) |

End-point of follow-up: Children’s anxiety was measured from baseline to the last available follow-up using validated anxiety scales.

Instruments and time points of outcome assessment: A: mYPAS at Entrance to the OR During induction B: mYPAS during induction C: mYPAS Holding area during induction D: STAI-C 48 hr before surgery 24 hr before surgery E: mYPAS Before surgery Holding area In the operating room (OR) F: mYPAS Holding area 5 min after intervention In the OR G: STAI-C Holding area H: mYPAS During induction I: ORSA Night before surgery J: FACES Before surgery

|

Preoperative anxiety All AV Interventions Versus Comparator Groups measured using different instruments.

Effect measure: Mean difference [95% CI]: A: -16.50 [-20.64, -12.36] B: -3.10 [-11.81, 5.61] C: -10.00 [-18.13, -1.87] D. -19.24 [-22.59, -15.89] E: -24.10 [-30.71, -17.49] F: -28.60 [-35.75, -21.45] G: 1.90 [-4.35, 8.15] H: -12.90 [-15.00, -10.80] I: -1.90 [-4.45, 0.65] J: -0.91 [-1.62, -0.20]

Pooled effect (random effects model): -11.44 [95% CI -17.29 to -5.59] favoring audiovisual interventions. Heterogeneity (I2): 97%.

|

Risk of bias: Tool used by authors:

A: High (no blinding of participants and personnel with high risk of performance bias and no blinding of outcome assessment with high risk of detection bias, and unclear allocation concealment) B: High (no blinding of participants and personnel with high risk of performance bias and no blinding of outcome assessment with high risk of detection bias, and unclear allocation concealment) C: High (no blinding of participants and personnel with high risk of performance bias and no blinding of outcome assessment with high risk of detection bias, and unclear allocation concealment) D: High (no blinding of participants and personnel with high risk of performance bias and no blinding of outcome assessment with high risk of detection bias, no allocation concealment, no random sequence generation, unclear other bias) E: High (unclear blinding of participants and personnel with risk of performance bias and unclear blinding of outcome assessment with risk of detection bias, unclear allocation concealment, unclear random sequence generation, unclear other bias) F: High (no blinding of participants and personnel with high risk of performance bias and no blinding of outcome assessment with high risk of detection bias, unclear allocation concealment, unclear random sequence generation, unclear other bias) G: High (no blinding of participants and personnel with high risk of performance bias and no blinding of outcome assessment with high risk of detection bias, unclear allocation concealment) H: Low (unclear blinding of participants and personnel/performance bias) I: High (no blinding of participants and personnel with high risk of performance bias and no blinding of outcome assessment with high risk of detection bias, unclear allocation concealment) J: Low (unclear allocation concealment/selection bias)

Author’s conclusion In conclusion, there is evidence to support the use of AV interventions in reducing anxiety for children who are undergoing elective surgeries. Our results, both quantitatively and qualitatively, show that AV interventions are more effective than SC in reducing anxiety, postoperative pain, behaviors and recovery, improving compliance during anesthetic induction and are well-tolerated. As such, AV interventions might be an attractive solution to optimizing perioperative care in children. Future studies should examine the impact of preoperative anxiety in all children and adolescents undergoing surgery.

Level of evidence GRADE: Anxiety: VERY LOW*** *Downgraded 1 point because of limitations in study design (risk of bias).

** Downgraded 1 point because of inconsistency (strength of effect differs between studies).

*** Downgraded 1 point because of imprecision (N total <2000).

Heterogeneity: clinical and statistical heterogeneity; explained versus unexplained subgroupanalysis) Cost effectiveness of AV intervention: “Only one study reported the approximate cost reduction associated with the use of AV interventions. In Pinto and Hollandsworth's study (1989) , a video intervention was estimated to reduce health care costs by $183 per child.

The authors state in the discussion: “Our review suggests that AV interventions are a promising and potentially cost-effective tool in helping to ameliorate children’s preoperative anxiety, as well as improving a number of other adverse perioperative outcomes.” |

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Simonetti, 2022 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

NA |

Yes (Although the RoB assessment of Ryu, 2018 and Ryu 2019 is unclear, text and figure 2 seem to be different/switched) |

Yes |

Yes |

No, not provided for each of the included studies |

|

Suleiman-Martos, 2022 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

NA |

Yes, using the ‘Risk of Bias Assessment’ (RoB 2.0; Sterne et al., 2019) |

Unclear. Heterogeneity (I2): 84%

in duration of the intervention (5-15 min) and in the time points before anaesthetic induction (20 min-24 h). - Heterogeneous control groups with respect to parental presence, type of intervention and medication supplied.

|

Yes |

No, not provided for each of the included studies |

|

Rantala, 2020 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes. |

Yes |

NA |

Yes |

Unclear: heterogeneity was statistically significant (I2 = 70.0%, p = .005). |

No |

No, not provided for each of the included studies |

|

Chow, 2016 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

NA |

Yes |

Unclear. There was high heterogeneity in this estimate (I2=97%).

The most common instruments used to assess children’s preoperative anxiety were the observer-rated YPAS and its modified one added item version (mYPAS), used in nine studies.

There was substantial clinical and methodological heterogeneity (i.e., SC practices, interventions, timing and duration, outcome measures using various scales, different comparison groups, etc.) across studies. |

No |

No, not provided for each of the included studies |

1. Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined

2. Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched

3. Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons

4. Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported

5. Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs)

6. Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table etc.)

7. Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (e.g. Chi-square, I2)?

8. An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (e.g., funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (e.g., Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.