Medicamenteuze behandeling bij allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen

Uitgangsvraag

Met welk(e) middel(en) kunnen patiënten met allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen het beste worden behandeld?

Aanbeveling

Schrijf bij patiënten met allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen en neusverstoppingsklachten een nasaal corticosteroïd voor (eventueel in combinatie met een nasaal antihistaminicum).

Geef de patiënt voorlichting over het juiste gebruik en de veiligheid van nasale corticosteroïden.

Controleer bij voorkeur 2 weken (eventueel telefonisch) na de start van de behandeling of de klachten van patiënten met allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen voldoende onder controle zijn. Pas zo nodig de behandeling aan.

Overwegingen

Allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen kan worden behandeld met een combinatie van een nasaal corticosteroïd en een nasaal antihistaminicum (meest effectief), een nasaal corticosteroïd (minder effectief), een nasaal of oraal antihistaminicum (nog minder effectief) en tenslotte montelukast en chromoglycaat (zie zelfzorgmiddelen) (minst effectief).

Geef een patiënt met een allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen een nasaal corticosteroïd tenzij de klachten mild en intermitterend zijn. Geef altijd een nasaal corticosteroïd als neusverstopping één van de presenterende klachten is.

Step-up naar een combinatie van een nasaal corticosteroïd en een lokaal antihistaminicum als de klachten na twee weken gebruik van een nasaal corticosteroïd onvoldoende gecontroleerd zijn.

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

De combinatie van azelastine/fluticasone resulteert waarschijnlijk in minder klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen dan fluticasone alleen bij volwassenen en adolescenten maar heeft waarschijnlijk geen aanvullend effect op de kwaliteit van leven.

Er is waarschijnlijk geen verschil in het optreden van bijwerkingen tussen de combinatie en alleen fluticasone.

Behandeling met nasale corticosteroïden resulteert waarschijnlijk in minder klachten en verbeterde kwaliteit van leven ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen dan behandeling met orale antihistaminica bij volwassenen en kinderen zonder aantoonbaar verschil in bijwerkingen (lage Grade). Er is waarschijnlijk geen klinisch relevant verschil tussen behandeling met orale en nasale antihistaminica met betrekking tot klachten, kwaliteit van leven en bijwerkingen.

Alhoewel voor alle medicatie is aangetoond dat er een afname van symptomen is ten opzichte van placebo, zijn lang niet alle bovengenoemde (gecombineerde) opties onderling goed vergeleken. Ook lijken niet alle gevonden (significante) verschillen klinisch relevant te zijn. Met name bij kinderen is de bewijskracht over het algemeen laag.

Er zijn geen aanwijzingen dat nasale corticosteroïden een systemische corticosteroïdbelasting geven ook niet bij (jonge) patiënten die inhalatiecorticosteroïden gebruiken.

Placebo gecontroleerde studies naar antihistaminica, nasale corticosteroïden, combinaties van nasale corticosteroïden/antihistaminica en montelukast laten over het algemeen geen relevante bijwerkingen van deze producten zien. Als patiënten klagen over epistaxis/bloed in nasale mucus bij gebruik van een neusspray moet de spraytechniek gecontroleerd worden aangezien dit over het algemeen wijst op een onjuiste spray techniek waarbij direct tegen het neustussenschot aangespoten wordt. Aangeraden wordt de neusspray altijd kruislings te gebruiken: spuit met de rechterhand in het linker neusgat en met de linkerhand in het rechter neusgat, zodat er altijd naar de buitenkant van de neus wordt gericht (Sastre, 2012).

Sommige patiënten klagen over de onaangename smaak van Azelastine. Moderne antihistaminica geven, in tegenstelling tot de eerste generatie, niet significant vaker sufheid/slaperigheid dan placebo.

De impact van de klachten op het functioneren van de patiënt wordt door behandelaars vaak onderschat (Keith, 2012). Veel patiënten worden onvoldoende behandeld en vaak zijn hun klachten niet onder controle (Gani, 2018).

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De prijs van alle genoemde medicatie is relatief laag (maximaal 20 euro per maand) waarbij veel patiënten medicatie slechts enkele maanden per jaar gebruiken. Deze kosten wegen niet op tegen mogelijke indirecte kosten, zoals niet kunnen werken of naar school kunnen gaan. Het doel van de behandeling zou dan ook moeten zijn om patiënten klachtenvrij te krijgen ook in situaties met matige allergeenexpositie.

Haalbaarheid en implementatie

Het gebruik van nasale corticosteroïden is al standaard zorg. De werkgroep voorziet daarom geen problemen op het gebied van de haalbaarheid en implementatie.

Rationale/ balans tussen de argumenten voor en tegen de interventie

|

Alleen nasale corticosteroïden hebben een klinisch relevant effect op neusverstoppingsklachten. Nasale corticosteroïden hebben niet meer bijwerkingen dan antihistaminica en geven, ook bij kinderen en langdurig gebruik, geen/minimale systemische belasting. |

|

Regelmatige controle van een behandelaar ten aanzien van de klachten lijkt geïndiceerd, omdat:

|

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Tot enkele jaren geleden was de behandeling met nasale corticosteroïden in de meeste richtlijnen de eerste keus bij de behandeling van matig-ernstige allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen. Eerdere studies naar het toevoegen van orale antihistaminica hebben geen additief verschil aangetoond. Recent is de combinatie van fluticasone met azelastine op de markt gekomen. Azelastine is een nasaal antihistaminicum met andere “anti-inflammatoire” of corticosteroïd potentiërende effecten. De rol van Azelastine ten opzichte van orale antihistaminica en nasale corticosteroïden en de combinatie van deze middelen ten opzichte van nasale corticosteroïden is onduidelijk. Daarnaast zijn er vragen over de plaats van leukotrieën receptor antagonisten in de behandeling van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Azelastine fluticasone versus nasale corticosteroïden

Klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen

|

Redelijk GRADE |

De combinatie van azelastine/fluticasone resulteert waarschijnlijk in minder klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen dan fluticasone bij volwassenen en adolescenten.

Bronnen: Berger, 2014; Carr, 2012; Hampel 2010; Price 2013 |

Kwaliteit van leven

|

Redelijk GRADE |

Er is waarschijnlijk geen verschil in kwaliteit van leven tussen behandeling met azelastine/fluticasone ten opzichte van fluticasone alleen, bij patiënten met allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen.

Bronnen: Carr, 2012; Hampel 2010 |

Bijwerkingen (treatment related adverse events)

|

Redelijk GRADE |

Er is waarschijnlijk geen verschil in het optreden van bijwerkingen tussen azelastine/fluticasone versus fluticasone bij volwassen patiënten en adolescenten met allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen.

Bronnen: Berger, 2014; Carr, 2012; Hampel 2010 |

Bijwerkingen - kinderen

|

Laag GRADE |

Er is mogelijk geen verschil in het optreden van bijwerkingen tussen azelastine/fluticasone en fluticasone bij kinderen met allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen.

Bron: Berger, 2018 |

Orale antihistaminica versus nasale corticosteroïden

Klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen bij volwassenen

|

Hoog GRADE |

Behandeling met nasale corticosteroïden resulteert in minder klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen dan behandeling met orale antihistaminica bij volwassenen.

Bronnen: Condemi, 2000; Bernstein, 1994; Ford, 2015; Frølund, 1991; Gawchik, 1997; Gehanno, 1997; ; Kim, 2015; Ratner, 1998; Rinne, 2002Schoenwetter, 1995; Vervloet, 1997 |

Klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen bij kinderen

|

Laag GRADE |

Behandeling met nasale corticosteroïden resulteert mogelijk in minder klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen bij kinderen ten opzichte van behandeling met orale antihistaminica.

Bronnen: Fokkens, 2004; Malizia, 2018; Wartna, 2017 |

Kwaliteit van leven bij volwassenen

|

Hoog GRADE |

Behandeling met nasale corticosteroïden resulteert in een verbetering in kwaliteit van leven ten opzichte van behandeling met orale antihistaminica bij volwassenen met allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen, maar dit verschil is niet klinisch relevant.

Bronnen: Bhatia, 2005; Condemi, 2000; Ford, 2015; Kim, 2015; Ratner, 1998 |

Kwaliteit van leven bij kinderen

|

Laag GRADE |

Er is mogelijk een verbetering in kwaliteit van leven bij kinderen na behandeling met nasale corticosteroïden ten opzichte van behandeling met orale antihistaminica, maar dit verschil is niet klinisch relevant.

Bron: Malizia, 2018 |

Bijwerkingen

|

Redelijk GRADE |

Er is waarschijnlijk geen verschil in het optreden van bijwerkingen tussen behandeling met nasale corticosteroïden en orale antihistaminica bij volwassenen en kinderen met allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen.

Bronnen: Andrews, 2009; Bernstein, 2004; Condemi, 2000; D’Ambrosio, 1998; Gawchik, 1997; Kim, 2015 |

Orale versus nasale antihistaminica

Klachten ten gevolge van allergie

|

Redelijk GRADE |

Behandeling van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen met nasale antihistaminica resulteert waarschijnlijk in een verbetering van klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen ten opzichte van orale antihistaminica, maar dit verschil is niet klinisch relevant.

Bronnen:(Berger, 2003; Berger, 2006; Charpin, 1995; Conde Hernández, 1995; Corren, 2005 |

Kwaliteit van leven

|

Redelijk GRADE |

Er is waarschijnlijk een verbetering in kwaliteit van leven bij behandeling van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen met nasale antihistaminica ten opzichte van orale antihistaminica, maar dit verschil is niet klinisch relevant.

Bronnen: Berger, 2006; Corren, 2005 |

Bijwerkingen

|

Laag GRADE |

Er is mogelijk geen verschil in het optreden van bijwerkingen tussen behandeling van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen met orale antihistaminica en nasale antihistaminica.

Bronnen: Charpin, 1995; Conde Hernández, 1995 |

Montelukast versus placebo

Klachten ten gevolge van allergie

|

Laag GRADE |

Montelukast resulteert mogelijk in een klinisch relevante vermindering van klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen dan placebo bij volwassenen en kinderen.

Bronnen: Chen, 2006; Ciebiada, 2006; Ciebiada, 2011; Hsieh, 2004; Kurowski, 2004; Philip, 2005; Okubo, 2008; Wei, 2016 |

Kwaliteit van leven

|

Laag GRADE |

Montelukast resulteert mogelijk in een niet-klinisch relevante verbetering van de kwaliteit van leven ten opzichte van placebo bij volwassenen en kinderen met allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen.

Montelukast resulteert mogelijk in verbetering in kwaliteit van leven ten opzichte van placebo bij kinderen met allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen.

Bronnen: Chen, 2006; Lombardo, 2006; Philip, 2005; Wei, 2016 |

Bijwerkingen

|

Laag GRADE |

Er is mogelijk geen verschil in het optreden van bijwerkingen tussen montelukast en placebo bij volwassenen en kinderen met allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen.

Bronnen: Bisgaard, 2009; Hsieh, 2004; Philip, 2005; Okubo, 2008 |

Montelukast versus antihistaminica

Klachten ten gevolge van allergie

|

Redelijk GRADE |

Er is waarschijnlijk geen verschil in effect op klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen tussen antihistaminica en montelukast bij volwassenen.

Bronnen: Andhale, 2016; Ciebiada, 2006; Kaur, 2017; Kurowski, 2004; Lombardo, 2006; Rajeshkar, 2018, Wei, 2016 |

Klachten ten gevolge van allergie bij kinderen

|

Laag GRADE |

Het antihistaminicum cetirizine resulteert mogelijk in een verbetering van klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen ten opzichte van montelukast bij kinderen.

Bronnen: Chen, 2006; Hsieh, 2004 |

Kwaliteit van leven

|

Laag GRADE |

Antihistaminica resulteren mogelijk in een niet-klinisch relevante verbetering in kwaliteit van leven ten opzichte van montelukast bij volwassenen met een allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen.

Er is mogelijk geen verschil in kwaliteit van leven bij behandeling van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen bij kinderen tussen cetirizine en montelukast.

Bronnen: Chen, 2006; Lombardo, 2006; Wei, 2016; |

Bijwerkingen

|

Redelijk GRADE |

Er is waarschijnlijk geen verschil in het optreden van bijwerkingen tussen behandeling met montelukast of antihistaminica bij patiënten met allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen.

Bronnen: Lombardo, 2006; Wei, 2016 |

Bijwerkingen bij kinderen

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Het is onduidelijk of er verschil is in bijwerkingen tussen montelukast en het antihistaminicum cetirizine bij behandeling van kinderen met allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen.

Bron: Hsieh, 2004 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Beschrijving studies

Azelastine/fluticasone versus nasale corticosteroïden (PICO 1)

Berger (2014) en Price (2013) beschrijven een open-label RCT uitgevoerd in India in 2009; 388 patiënten kregen azelastine/fluticason en 199 kregen fluticason gedurende een jaar. In de azelastine/fluticasongroep was na een jaar nog 77% van de patiënten over en in de fluticasongroep nog 74% van de patiënten. Price (2013) rapporteerde de reflective nasal total symptom score (rTNSS) van deze patiënten. Berger (2014) rapporteerde adverse events. Kwaliteit van leven en ziekteverzuim werden niet gerapporteerd.

Carr (2012) poolde 3 RCT’s: MP 4002 (NCT00651118), MP4004 (NCT00740792) (Meltzer 2012) en MP4006 (NCT00883168) in een meta-analyse. Dit betroffen multicenter, gerandomiseerde, dubbelblinde, placebo-gecontroleerde studies. In verschillende seizoenen werden de patiënten gedurende 14 dagen behandeld. In totaal 848 patiënten kregen azelastine/fluticason toegediend en 846 patiënten kregen een corticosteroïden (fluticason propionate) toegediend. Gerapporteerde uitkomsten waren verandering ten opzichte van baseline van de som van in de ochtend en avond gescoorde rTNSS de maximum rTNSS of instantaneous nasale symptoom score was 24 (ie 4 symptomen x score van 3 x 2 voor ochtend en avond), kwaliteit van leven gemeten met de RQLQ (Rhinitis Quality of Life Questionnaire) en bijwerkingen. Ziekteverzuim werd niet gerapporteerd.

Hampel (2010) rapporteert een multicenter, gerandomiseerde, dubbelblinde, placebo-gecontroleerde RCT. De patiënten werden gedurende 14 dagen behandeld. In totaal 153 patiënten kregen azelastine/fluticason en 151 kregen fluticason. Gerapporteerde uitkomsten waren verandering ten opzichte van baseline van de som van in de ochtend en avond gescoorde rTNSS de maximum rTNSS of instantaneous nasale symptoom score was 24 (ie 4 symptomen x score van 3 x 2 voor ochtend en avond), kwaliteit van leven gemeten met de RQLQ en bijwerkingen. Ziekteverzuim werd niet gerapporteerd.

Kinderen

Berger (2018) beschrijft een open-label RCT uitgevoerd bij kinderen van 4 tot 11 jaar in de USA op 42 sites; 304 kinderen kregen azelastine/fluticason en 101 kinderen kregen fluticason gedurende een jaar. In de azelastine/fluticasongroep was na drie maanden nog 94% van de patiënten over en in de fluticasongroep nog 91% van de patiënten. Van deze studie werd als uitkomst alleen het aantal adverse events gerapporteerd.

Orale antihistaminica versus nasale corticosteroïden (PICO 2)

Een systematische review van 16 studies is opgenomen in de literatuuranalyse (Weiner, 1998). Zes van de studies beschreven in deze review voldeden aan de zoekcriteria en zijn geëvalueerd, de overige zijn buiten beschouwing gelaten. Daarnaast zijn 19 RCT’s opgenomen in de analyse. Als orale antihistaminicum behandeling werden astemizole, loratadine, desloratadine, cetirizine en levocetirizine bestudeerd, als corticosteroïden fluticasone propionate, triamcinolone acetonide, becalmethasone dipropionate, budenoside en ciclesonide. Het merendeel van de studies hanteerde een behandelingsduur van 2 tot 4 weken.

Drie studies bestudeerden specifiek een populatie jonger dan 18 jaar. Wartna (2017) onderzocht behandeling met levocetirizine en fluticasone propionate op indicatie bij SAR patiënten van 6 tot 18 jaar (n=150) gedurende 3 maanden. Malizia (2018) onderzocht cetirizine (10 mg) en beclomethasone dipropionate (tweemaal daags 100 μg per neusgat) in patiënten van 6 tot 14 jaar oud (n=68) gedurende 3 weken. Fokkens (2004) bestudeerde kinderen van 2 tot 4 jaar (n=26), en beschreef neussymptoomscores uitgesplitst in dag en nacht.

Orale versus nasale antihistaminica (PICO 3)

Geïncludeerde studies vergeleken orale antihistaminicum behandeling met azelastine nasale spray behandeling bij patiënten met seizoensgebonden allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen.

Ellis (2013) is een dubbel-blinde RCT en includeerde volwassenen gediagnosticeerd met seizoensgebonden allergische rhinitis (SAR). Patiënten (n=70) werden in een cross-over structuur gedurende 8 uur blootgesteld aan allergenen in een gecontroleerde omgeving en behandeld met orale loratadine, orale cetirizine, nasale azelastine of placebo. Gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten waren onset of action en nasale symptoomscore (totaal en individuele scores).

Berger (2006) is een dubbel-blinde multicenter RCT (ACT II) en includeerde patiënten van tenminste 12 jaar oud gediagnosticeerd met SAR. (n=360) Patiënten werden gedurende 2 weken behandeld met cetirizine (10 mg) of azelastine nasale spray (tweemaal daags 2 sprays per neusgat). Gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten waren een totale nasale symptoomscore, individuele symptoomscores en RQLQ.

Corren (2005) is een dubbelblinde multicenter RCT (ACT I) en includeerde patiënten van tenminste 12 jaar oud gediagnosticeerd met SAR. Patiënten (n=307) werden gedurende 2 weken behandeld met cetirizine (10 mg) of azelastine nasale spray (tweemaal daags 2 sprays per neusgat). Gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten waren een totale nasale symptoomscore en time of onset daarvan, individuele symptoomscores en RQLQ.

Berger (2003) is een dubbelblinde multicenter RCT en includeerde patiënten van tenminste 12 jaar oud gediagnosticeerd met SAR. Patiënten (n=440) werden gedurende 2 weken behandeld met desloratadine (5 mg), azelastine nasale spray (tweemaal daags 2 sprays per neusgat), een combinatie van beide behandelingen of placebo. Gerapporteerde uitkomstmaat was de verandering in totale nasale symptoomscore.

Charpin (2003) is een dubbelblinde multicenter RCT en includeerde patiënten van tenminste 12 jaar oud gediagnosticeerd met SAR. Patiënten (n=129) werden gedurende 2 weken behandeld met cetirizine (10 mg) of azelastine nasale spray (tweemaal daags 1 spray per neusgat). Gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten waren de door de onderzoeker vastgestelde symptoomscore (TSSI), verandering daarin, door de patiënt gerapporteerde VAS-score en tolerantie voor de medicatie.

Conde Hernández (1995) is een open-label RCT en includeerde patiënten gediagnosticeerd met SAR. Patiënten (n=63) werden gedurende 2 weken behandeld met ebastine (10 mg) of azelastine nasale spray (tweemaal daags 2 sprays per neusgat). Gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten waren de verandering in totale symptoomscore, afzonderlijke symptoomscores en actieve rhinomanometrie.

Gambardella (1993) is een dubbelblinde RCT en includeerde volwassen patiënten gediagnosticeerd met SAR. Patiënten (n=30) werden gedurende 6 weken behandeld met loratadine (10 mg) of azelastine nasale spray (tweemaal daags 1 spray per neusgat). Gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten waren de totale symptoomscore en de veranderingen daarin.

Kinderen

Er zijn geen studies gevonden binnen de gestelde criteria waarin het effect van de medicatie op kinderen afzonderlijk is beschreven.

Leukotrieën receptor antagonisten versus placebo of antihistaminica (PICO 4 en 5)

In de literatuuranalyse is de meta analyse van Wei (2106) opgenomen en ge-update met recente RCT’s (Rajashekar, 2018; Kaur, 2017). Daarnaast zijn er 10 RCT’s geïncludeerd gepubliceerd tussen 2000 en 2016 die niet in de meta-analyse van Wei (2016) zijn opgenomen. Hiervan zijn acht studies uitgevoerd bij volwassenen (Andhale, 2016; Ciebiada, 2011; Okubo, 2008; Ciebiada, 2006; Lombardo, 2006; Philip, 2004; Kurowski, 2004) en studies includeerden kinderen (Bisgaard, 2009; Hsieh, 2004; Chen, 2006)

De meta-analyse van Wei (2016) includeerde uitsluitend RCT’s (n=16). Alleen RCT’s die uitkomstmaten rapporteerden op basis van de meest gebruikte schalen voor symptoomscores werden hierbij meegenomen. De studiepopulatie betrof patiënten met seizoensgebonden en niet-seizoensgebonden allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen. Studies waarbij de populatie astma patiënten betrof, werden geëxcludeerd. Ook werden studies met een hoog risico op bias (geen blindering van patiënten en behandelaars) niet meegenomen in de meta-analyse. Geïncludeerde studies vergeleken behandeling met montelukast met een controle groep (placebo en/of antihistamine). Voor het beantwoorden van deze uitgangsvraag werden alleen de resultaten van de studies geëxtraheerd die montelukast vergeleken met een antihistaminicum en niet met combinatietherapie (n=8).

Rajeshekar (2018) is een dubbelblinde RCT en includeerde patiënten gediagnosticeerd met mild tot matige Persistent Allergische Rhinitis (PAR). Patiënten (n=70) werden gedurende drie weken behandeld met montelukast of ebastine. Gerapporteerde uitkomstmaat was de five nasal symptom scoring (T5NSS).

Kaur (2017) is een RCT en includeerde patiënten (15 tot 55 jaar) met AR (n=125). Patiënten werden gedurende zes weken behandeld met montelukast (10mg), levocetirizine (5mg), fexofenadine (180mg), desloratadine (5 mg) of chlorpheniramine (4 mg). Gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten waren een symptoomscore voor niezen en een symptoomscore voor nasal discharge/rhinorrhoe.

Andhale (2016) is een trial waarin patiënten met PAR (n=50) gedurende twee weken werden behandeld met montelukast (10 mg) of levocetirizine (5 mg). Gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten zijn gemeten op een VAS-schaal voor neus- en oogsymptomen gedurende de dag en de nacht.

Ciebiada (2011) is een RCT met een cross-over design en includeerde patiënten met PAR. Patiënten (n=20) werden gedurende 6 weken behandeld met montelukast (10 mg), levocetirizine (5 mg) of placebo met tussendoor ‘washout” periode van 2 weken. Gerapporteerde uitkomsten waren congestion symptoms geschat op basis van nasal symptoms score gerapporteerd in een patiënten dagboek.

Okubo (2008) is een dubbelblinde RCT bij patiënten met SAR met symptomen (n=945). Patiënten werden gedurende 2 weken behandeld met placebo, montelukast (5 mg of 10 mg). Gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten waren composite nasal symptom scores (CNSS), gedefinieerd als gemiddelde score van nasal symptom scores gedurende de dag en nacht, en bijwerkingen.

Ciebiada (2006) is een dubbelblinde RCT met cross-over design. Patiënten met PAR werden geïncludeerd en gedurende zes weken behandeld met montelukast, levocetirizine en placebo (n=20) met daartussen een ‘washout’ periode van twee weken. Gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten zijn total daytime nasal symptoms score en daytime eye symptom score.

Lombardo (2006) is een RCT en includeerde patiënten met SAR. Patiënten werden behandeld gedurende 4 weken met montelukast (10 mg), levocetirizine (5 mg) of placebo (n=254). Gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten zijn daytime nasal symptoms (DNSS), nighttime nasal symptoms (NSS), en daytime eye symptoms (DES) en RQLQ.

Philip (2005) is een multicenter RCT en includeerde patiënten met SAR (ten minste milde symptomen) en actieve astma (n=831). Patiënten werden gedurende 6 weken behandeld met montelukast of placebo. Gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten waren een Daily Rhinitis Symptoms score, gedefinieerd als het gemiddelde van DNSS en NSS), RQLQ en bijwerkingen.

Kurowski (2004) is een dubbelblinde RCT en includeerde patiënten met SAR. Patiënten (n=41) werden gedurende 12 weken (6 weken pre-seizoen) behandeld met montelukast (10 mg), cetirizine (10 mg) of placebo. Gerapporteerde uitkomstmaat was een all-symptoms score (Rhinoconjunctivitis symptom score) gemeten op een 6-punts schaal.

Kinderen

Bisgaard (2009) is een studie waarin studieresultaten naar veiligheid van montelukast uit eerder gepubliceerde en niet gepubliceerde placebo gecontroleerde dubbelblinde en open-label pediatrische studies worden gerapporteerd. Alleen de resultaten van de dubbelblinde RCT (alleen gepubliceerd in Bisgaard, 2009) die kinderen (2 tot 14 jaar) met SAR (n=413) includeerde werden meegenomen in deze literatuursamenvatting. In deze studie werden alleen het aantal bijwerkingen gerapporteerd

Chen 2006 is een dubbelblinde RCT en includeerde kinderen (2 tot 6 jaar) met PAR (n=60). Patiënten werden gedurende 12 weken behandeld met cetirizine (5 mg), montelukast (4 mg) of placebo. Gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten waren een total symptoms score (TSS) en PRQLQ.

Hsieh (2004) is een dubbelblinde RCT die kinderen (6 tot 12 jaar) met PAR includeerde (n=65). Patiënten werden gedurende 12 weken behandeld met cetirizine (10 mg), montelukast (5 mg) of placebo. Gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten waren total symptoms score (TSS), PRQLQ en bijwerkingen.

Resultaten

Azelastine fluticasone versus nasale corticosteroïden (PICO 1)

Klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen (symptomen (rTNSS))

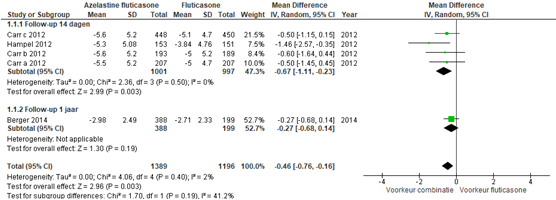

rTNSS werd gerapporteerd door Carr (2012), Price (2013), Hampel (2010) en Berger (2014). De resultaten van de rTNSS werden gecombineerd in een forest plot, zie figuur 1. Voor de studies met een follow-up van 14 dagen was het gepoolde effect -0,67 (95% BI -1,11 tot 0,23), dit effect is klinisch relevant aangezien het groter is dan de grens van 0,5 SD.

Bij de studie met een follow-up van 1 jaar werd een effect gezien van -0,27 (95% BI -0,76 tot -0,16) (Berger, 2014).

Figuur 1 Reflective total nasal symptom score voor de combinatie azelastine/fluticasone versus fluticasone

Z: p-waarde van het gepoolde effect; df: degrees of freedom (vrijheidsgraden); I2: statistische heterogeniteit; CI: betrouwbaarheidsinterval.

NB Hampel (2012) rapporteert geen SD van de eindscore, daarom is de baseline SD ingevuld

Kwaliteit van leven (RQLQ)

De RQLQ werd gerapporteerd door Carr (2012) en Hampel (2010). Carr (2012) vond een verschil op RQLQ van 1,6 (SD 1,3) voor azelastine/fluticasone en van 1,5 voor fluticasone; een verschil van -0,10 (95% BI -0,22 tot 0,00). Hampel vond een verschil op de RQLQ van 1,60 voor azelastine/fluticasone en 1,43 voor fluticasone; een verschil van -0,17 (95% BI -0,46 tot 0,12). Beide verschillen waren niet statistisch significant en niet klinisch relevant.

Kwaliteit van leven werd niet gerapporteerd voor kinderen.

Bijwerkingen

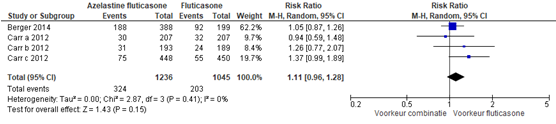

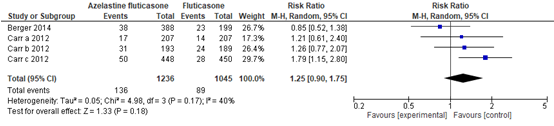

Een overzicht van bijwerkingen wordt gegeven in twee forest plots. Figuur 2 geeft een overzicht van alle bijwerkingen die gemeld werden tijdens de trial. Daarbij werd een risk ratio gevonden van 1,11 (95% BI 0,96 tot 1,28). Dit effect was niet statistisch significant en ook niet klinisch relevant. Figuur 3 geeft een overzicht van treatment related adverse events. Daarbij werd een risk ratio gevonden van 1,25 (95% BI 0,90 tot 1,75). Dit effect was ook niet statistisch significant noch klinisch relevant.

Berger (2014) geeft aan dat dysgeusia (bittere smaak) het meest frequent werd gerapporteerd (2,5%) net als hoofdpijn (4,3%). Hampel (2010) gaf geen totaal overzicht van hoeveel procent van de deelnemers last had van bijwerkingen maar rapporteerde hoe frequent een aantal bijwerkingen voorkwam.

Figuur 2 Treatment emergent adverse events van azelastine/fluticasone versus fluticasone

Z: p-waarde van het gepoolde effect; df: degrees of freedom (vrijheidsgraden); I2: statistische heterogeniteit; CI: betrouwbaarheidsinterval

Figuur 3 Treatment related adverse events van azelastine/fluticasone versus fluticasone

Z: p-waarde van het gepoolde effect; df: degrees of freedom (vrijheidsgraden); I2: statistische heterogeniteit; CI: betrouwbaarheidsinterval

Kinderen

Er werd een vergelijkbaar percentage bijwerkingen (treatment emergent adverse events) gezien bij gebruik van azelastine/fluticasone 41% versus fluticasone (37%). Voor treatment related adverse events was dit azelastine/fluticasone 16% versus fluticasone (12%).

Bewijskracht van de literatuur

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen (symptomen (rTNSS)) is gebaseerd op gerandomiseerd onderzoek en start derhalve hoog en werd met één niveau verlaagd naar redelijk vanwege imprecisie (overlap met de grens voor klinische relevante).

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen bij kinderen is gebaseerd op gerandomiseerd onderzoek en start derhalve hoog. Er is 2 niveaus verlaagd gezien het zeer geringe aantal patiënten (imprecisie) en met 1 niveau wegens beperkingen in de onderzoeksopzet (risk of bias), waarmee de bewijskracht uitkomt op zeer laag.

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat kwaliteit van leven is gebaseerd op gerandomiseerd onderzoek en start derhalve hoog en werd met één niveau verlaagd vanwege imprecisie (slechts 2 studies rapporteren kwaliteit van leven).

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat treatment related adverse events is gebaseerd op gerandomiseerd onderzoek en start derhalve hoog en is met één niveau verlaagd naar redelijk vanwege het overschrijden van de grens van klinische relevantie (imprecisie).

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat treatment related adverse events bij kinderen is gebaseerd op gerandomiseerd onderzoek en start derhalve hoog en is met twee niveaus verlaagd naar laag gezien beperkingen in de onderzoeksopzet omdat het een open label studie betreft (risk of bias) en vanwege het geringe aantal patiënten (imprecisie).

Orale antihistaminica versus nasale corticosteroïden (PICO 2)

Klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen (symptoomscores)

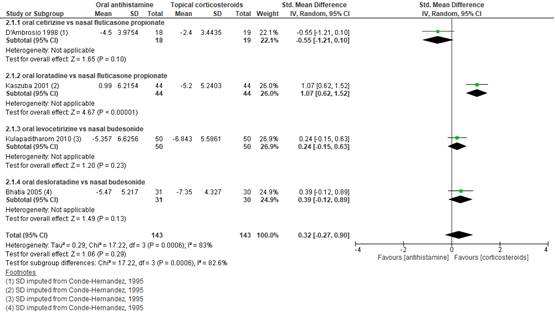

In vier studies in volwassenen (d’Ambrosio, 1998; Kaszuba, 2001; Kulapaditharom, 2010; Bhatia, 2005) bij in totaal 286 patiënten werden de verbetering in totale symptoomscore vergeleken tussen orale antihistaminica en nasale corticosteroïden. De gecombineerde SMD was 0,32, met een 95% BI van -0,27 tot 0,90, zoals weergegeven in figuur 4. Frølund (1991) vond geen significant verschil in totale symptoomscore tussen loratadine en beclomethasone dipropionate behandeling gedurende 3 weken, maar verstrekte te weinig informatie om dit in de analyse mee te nemen. Charpin (1994) vond daarentegen een significant sterkere afname in symptoomscore bij behandeling met fluticasone propionate vergeleken met cetirizine, maar vermeldde ook niet voldoende gegevens om de data te kunnen analyseren.

Figuur 4 Verschil in Totale Symptom score (TSS) van orale antihistamine versus nasale corticosteroïd behandeling

Z: p-waarde van gepoolde effect; df: degrees of freedom (vrijheidsgraden); I2: statistische heterogeniteit; CI: betrouwbaarheidsinterval

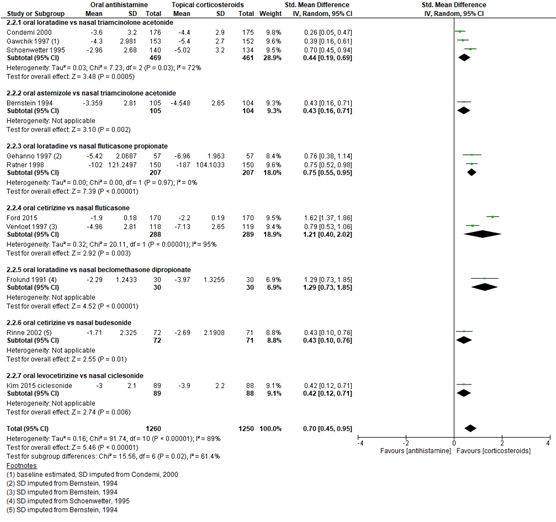

Naast de totale symptoomscore werd ook de totale score van nasale symptomen beschreven. Uit de gepoolde data van 11 RCT s met in totaal 2510 patiënten werd consequent een sterkere symptoomscore verbetering gevonden bij corticosteroïden vergeleken met orale antihistaminicum, met een gestandaardiseerd gemiddeld verschil van 0,70 en een 95% BI van 0,45 tot 0,95 (figuur 5). Dit verschil is klinisch relevant. Van een aantal studies moesten de waarden omgerekend worden of moest de SD geïmputeerd worden op basis van vergelijkbare studies, omdat deze gegevens ontbraken.

Figuur 5 Verschil in Totale Nasale Symptoom Score (TNSS) van orale antihistamine versus nasale corticosteroïden behandeling

Z: p-waarde van gepoolde effect; df: degrees of freedom (vrijheidsgraden); I2: statistische heterogeniteit; CI: betrouwbaarheidsinterval

Kinderen

Drie studies die bij kinderen behandeling met nasale corticosteroïden vergeleken met orale antihistaminica vonden een lagere symptoomscore bij gebruik van corticosteroïden. Bij kinderen van 6 tot 14 jaar oud (Malizia, 2018) werd een significant grotere afname in totale symptoomscore gevonden bij gebruik van nasale beclomethason (least square mean change -5,63) vergeleken met orale cetirizine (-3,54; P=0,008). Dagelijkse behandeling met fluticason resulteerde bij kinderen van 6 tot 18 jaar oud (Wartna, 2016) in een lagere dagelijkse symptoomscore (totaalscore: 3,90 ± 3,06; neussymptomen: 3,20± 1,79) dan levocetirizine gebruik op indicatie (totaalscore: 4,63 ± 2,82; neussymptomen: 4,14 ± 1,76), maar deze verschillen waren niet significant. Bij jonge kinderen (van 2 tot 4 jaar oud), werd een lagere gecombineerde symptoomscore gevonden na 4-6 weken gebruik van fluticason ten opzichte van ketotifen. Nachtsymptomen waren 4,2 ± 0,7 (standard error) bij gebruik van fluticason, versus 6,5 ± 0,7 (p=0,036) bij gebruik van ketotifen. Dagsymptomen waren bij fluticason 3,6 ± 0,6 versus 5,5 ± 0,6 (p=0,049) bij ketotifen (Fokkens, 2004). Door de verschillende manieren waarop de waarden zijn uitgedrukt en/of het ontbreken van baselinewaarden kunnen de gegevens van de drie studies niet gepoold worden weergegeven.

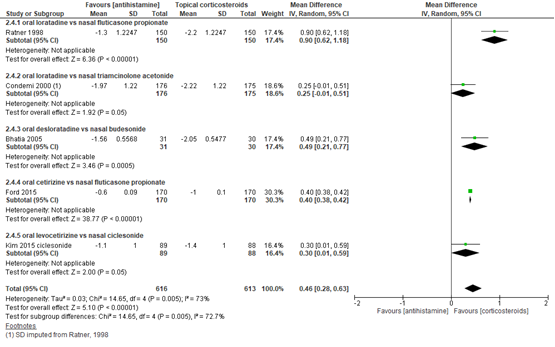

Kwaliteit van leven / Rhinoconjunctivitis quality of life questionnaire (RQLQ)

Vijf studies met in totaal 1229 patiënten rapporteerden de verbetering in RQLQ bij behandeling met verschillende medicatie. Nasale corticosteroïden gaven een sterkere verbetering dan orale antihistaminica, met een gemiddeld verschil van 0,46 (op een 7 puntsschaal) en een 95% BI van 0,28 tot 0,63. Dit verschil is niet klinisch relevant (figuur 6).

Kinderen

Malizia (2018) vond een vergelijkbaar effect bij kinderen, met een sterkere verbetering in kwaliteit van leven gemeten met de PRQLQ bij beclomethason vergeleken met cetirizine (-1,15 versus -0,69; P=0,031).

Figuur 6 Rhinitis Quality of Life Questionnaire (RQLQ) bij orale antihistamine versus nasale corticosteroïden behandeling

Z: p-waarde van gepoolde effect; df: degrees of freedom (vrijheidsgraden); I2: statistische heterogeniteit; CI: betrouwbaarheidsinterval

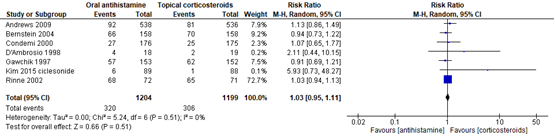

Bijwerkingen

In 7 studies werd de incidentie van bijwerkingen kwantitatief beschreven. Bij in totaal 2403 patiënten was de het relatieve risico 1,03, met een 95% betrouwbaarheidsinterval van 0,95 tot 1,11 (figuur 7). Waarschijnlijk hebben de studies geen eenduidige criteria gehanteerd, aangezien de waarden binnen dezelfde type medicatie varieerden van 7% (Kim, 2015) tot 94% (Rinne, 2002).

Figuur 7 Bijwerkingen bij orale antihistamine versus nasale corticosteroïden behandeling

Z: p-waarde van gepoolde effect; df: degrees of freedom (vrijheidsgraden); I2: statistische heterogeniteit; CI: betrouwbaarheidsinterval

Kinderen

Fokkens (2004) rapporteerde dat er geen ernstige bijwerkingen werden waargenomen (fluticason versus ketotifen).

Bewijskracht van de literatuur

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaten is gebaseerd op gerandomiseerd onderzoek en start derhalve hoog.

De bewijskracht van de uitkomstmaat klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen werd met twee niveaus verlaagd voor totale symptomen vanwege variatie in de resultaten (inconsistentie) en overschrijden van de grenzen van klinische relevantie (imprecisie) naar laag.

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat nasale symptomen is hoog en werd niet verlaagd.

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen bij kinderen is met drie niveaus verlaagd naar laag gezien de indirectheid van de bepalingen en het beperkt aantal patiënten (imprecisie).

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat kwaliteit van leven is niet verlaagd en blijft hoog. De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat kwaliteit van leven bij kinderen is verlaagd met 2 niveaus naar laag gezien het zeer beperkt aantal patiënten (imprecisie).

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat bijwerkingen is met één niveau verlaagd gezien de variatie in de definitie van bijwerkingen in de verschillende studies (inconsistentie) naar redelijk.

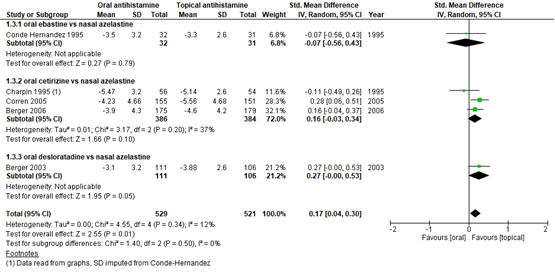

Orale versus nasale antihistaminica (PICO 3)

Klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen (symptoomscores)

De gecombineerde score van neus- oog- en keelsymptomen werd gerapporteerd door Gambardella (1993), Charpin (1995) en Conde Hernández (1995). Omdat het niet duidelijk was of dezelfde scores gehanteerd werden, zijn de resultaten weergegeven als gestandaardiseerd gemiddelde verschil (SMD). Het SMD bij in totaal 203 patiënten was -0,10 in het voordeel van orale medicatie, met een 95% BI van -0,37 tot 0,18. Dit is een klein, niet klinisch relevant verschil. De gecombineerde symptoomscore voor nasale symptomen na een behandeling van 2 weken werd in 5 studies beschreven. In een gecombineerde analyse (figuur 8) van Conde Hernández (1995), Charpin (1995), Berger (2003), Corren (2005) en Berger (2006) was het SMD 0,17 in het voordeel van nasale spray, met een 95% BI van 0,04 tot 0,30. Dit verschil is klein en niet klinisch relevant, zoals aangegeven in figuur 8. Ellis (2013) vond 6 uur na behandeling (orale loratadine of orale cetirizine versus nasale azelastine) een SMD van 0,19 met een 95% BI van -0,74 tot 1,12. Daarnaast beschreven Conde Hernández (1995) en Charpin (1995) een gecombineerde oogsymptoomscore, dat met een SMD van -0,32 en 95% BI van -0,62 tot -0,02 in het voordeel is van orale toediening, maar dit verschil is niet klinisch relevant.

Figuur 8 Gemiddeld verschil in TNSS bij orale versus nasale antihistamine behandeling

Z: p-waarde van gepoolde effect; df: degrees of freedom (vrijheidsgraden); I2: statistische heterogeniteit; CI: betrouwbaarheidsinterval

Kwaliteit van leven/ Rhinoconjunctivitis quality of life questionnaire (RQLQ)

Twee studies rapporteerden de RQLQ (een gemiddelde score van 28 vragen op een zeven-puntsschaal). Corren (2005) en Berger (2006) vonden beide een sterkere verbetering in nasale dan in orale toediening, met een gemiddeld verschil van 0,36 en een 95% BI van 0,17 tot 0,54. Dit verschil is klinisch niet relevant.

Bijwerkingen

Het totale aantal bijwerkingen werd beschreven door Charpin (1995) en Conde Hernández (1995). Bij 22,7% van de 198 patiënten werden bijwerkingen gerapporteerd, met een relatief risico van 1,26 (95% BI 0,65 tot 2,43) in het voordeel van nasale toediening. Dit verschil is niet klinisch relevant. Diverse bijwerkingen werden gerapporteerd bij het gebruik van de medicatie. Bittere smaak en slaperigheid werden vaak gerapporteerd bij het gebruik van azelastine. Slaperigheid werd ook gerapporteerd bij cetririzine en ebastine. Verder kwamen diverse klachten zoals misselijkheid en hoofdpijn voor bij meerdere middelen.

Bewijskracht van de literatuur

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaten klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen en kwaliteit van leven is gebaseerd op gerandomiseerd onderzoek en start derhalve hoog en is met één niveau verlaagd gezien het gering aantal patiënten (imprecisie) naar redelijk.

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat bijwerkingen is gebaseerd op gerandomiseerd onderzoek en start derhalve hoog en is met twee niveaus verlaagd gezien het beperkte aantal patiënten en de overlap van het betrouwbaarheidsinterval met 1 (imprecisie) naar laag.

Montelukast versus placebo (PICO 4)

Klachten ten gevolge van allergie

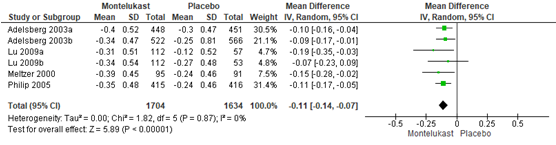

Symptomen werden gerapporteerd door 6 studies (Wei, 2016; Philip, 2005; Ciebiada, 2011; Okubo, 2008; Ciebiada, 2006; Kurowski, 2004), indien beschikbaar is de totaal score/ composite score gerapporteerd. Wei (2016) rapporteerde een composite symptoms score (CSS) op een 4-punts schaal (0-3). In de studies die werden geïncludeerd was de CSS gedefinieerd als de gemiddelde waarde van DNSS en NSS. Het gepoolde effect was -0,11 (95%BI -0.14 tot -0,07) in het voordeel van montelukast en wordt weergegeven in een forest plot (figuur 9).

Figuur 9 CSS montelukast vergeleken met placebo. Bron: Wei, 2016 aangevuld met studie Philip, 2005

Z: p-waarde van gepoolde effect; df: degrees of freedom (vrijheidsgraden); I2: statistische heterogeniteit; CI: betrouwbaarheidsinterval

Ciebiada (2011) rapporteerde neusverstopping (congestion symptoms). In de groep behandeld met montelukast werd op dag 42 een afname van 1,5 gerapporteerd en in de placebogroep een afname van 1,0 ten opzichte van baseline metingen (gemiddelde verschil -0,5; 95%BI -0,64 tot -0,37).

In de studie van Okubo (2008) was de gemiddelde afname in CNSS (gemiddelde DNSS en NSS) in de placebogroep -0,37 (SD en 95%BI niet gerapporteerd). Voor zowel de 5 mg als de 10 mg groep werd een significant grotere afname ten opzichte van de placebo groep van -0,47 gerapporteerd (SD en 95%BI niet gerapporteerd, p= 0,001). Ciebiada (2006) rapporteerde de DNSS en DES. Na 6 weken was er in de groep behandeld met montelukast een grotere afname in DNSS ten opzichte van baseline naar 3,44 (SD 2,5) ten opzichte van 4,99 (SD 3,4) in de placebogroep (p<0,001). Na 6 weken was er in de groep montelukast een grotere afname in DES ten opzichte van baseline naar 1,13 (SD 1,7) ten opzichte van 1,71 (SD 2,8) in de placebogroep (p<0.001).

Kurowski (2004) rapporteerde na 6 weken geen significante verschillen in de totale symptoms score tussen de groep behandeld met montelukast en de groep behandeld met placebo (zie resultaten uit figuur 10): symptoomscore van 1,0 in de placebogroep; symptoomscore van 1,2 in de groep montelukast.

Kinderen

Chen (2006) rapporteerde TSS gedefinieerd als de gemiddelde daily nasal en non-nasal symptoms over 7 dagen. In de groep behandeld met montelukast was de afname in TSS significant hoger met -0,43 (SD 0,23) ten opzichte van een afname in de placebogroep van -0,11 (SD 0,12) (p<0,001). Hsieh (2004) rapporteerde TSS gedefinieerd als somscore van nasal en non-nasal symptoms. In de groep behandeld met montelukast werd een klinisch relevante afname in symptomen gerapporteerd van 2,7 (baseline 8,9; 12 wk: 6,2) en in de groep behandeld met placebo een afname van 0,2 (baseline 8,5; 12 wk: 8,3, p<0,01).

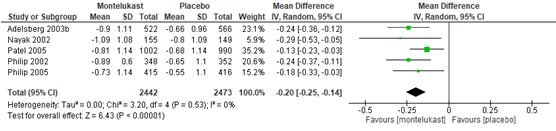

Kwaliteit van leven (Rhinoconjunctivitis quality of life questionnaire (RQLQ))

Drie studies rapporteerden de RQLQ (Wei, 2016; Lombardo, 2006; Philip, 2005). Het gepoolde effect van de studies van Wei (2016) en Philip (2005) was -0,20 (95%BI -0,25 tot -0,14) in het voordeel van montelukast. Lombardo (2006) rapporteerde significant groter effect in de RQLQ score (7 puntschaal 0=best, 6=worst) in de groep montelukast van 0,6 ten opzichte van 0,4 in de placebo groep (p<0,01).

Figuur 10 RQLQ montelukast vergeleken met placebo. Bron: Wei, 2016 aangevuld met studie Philip, 2005

Z: p-waarde van gepoolde effect; df: degrees of freedom (vrijheidsgraden); I2: statistische heterogeniteit; CI: betrouwbaarheidsinterval

Kinderen

Chen (2006) rapporteerde een afname in de PRQLQ in de groep behandeld met montelukast van -19,15 (SD 20,71) ten opzichte van een afname van -3,85 (SD 5,56) in de placebogroep (gemiddeld verschil: -15,3 95%BI -24,7 tot -5,7, p=0,028).

Bijwerkingen

Bijwerkingen werden in twee studies gerapporteerd (Okubo, 2008; Philip, 2005). Okubo (2008) rapporteerde geen verschillen in bijwerkingen; 4,1% in de placebogroep en respectievelijk 4,7% en 4,2% in de groep behandeld met montelukast 5mg en 10 mg. Hoofdpijn en sufheid kwamen in ongeveer 1% voor in alle groepen. Philip (2005) rapporteerde bijwerkingen bij respectievelijk 49 (11,8%) en 54 (13,0%) patiënten in de groep behandeld met montelukast en de placebogroep.

Kinderen

Bijwerkingen bij kinderen werden in twee studies gerapporteerd (Bisgaard, 2009, Hsieh, 2004). De studie in Bisgaard (2009) rapporteerde geen verschillen in tussen de groep behandeld met montelukast bijwerkingen (n=73, 26,1%) en de placebogroep (n=35, 26,3%). Hsieh (2004) rapporteerde geen significante verschillen in bijwerkingen tussen de studiearmen (hoofdpijn, sufheid en vermoeidheid). In de arm montelukast bijwerkingen bij één patiënt in de groep (hoofdpijn) en twee patiënten in de placebogroep (hoofdpijn en vermoeidheid).

Bewijskracht van de literatuur

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaten klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen en kwaliteit van leven is gebaseerd op gerandomiseerd onderzoek en start derhalve hoog en werd met twee niveaus verlaagd vanwege beperkingen in de studieopzet (risk of bias) en overschrijden van de grenzen van klinische relevantie (imprecisie) naar laag.

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat bijwerkingen gebaseerd op gerandomiseerd onderzoek en start derhalve hoog en is met twee niveaus verlaagd gezien het beperkt aantal patiënten (imprecisie) en beperkingen in de onderzoeksopzet (risk of bias) naar laag voor zowel volwassenen als voor kinderen.

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaten klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen en kwaliteit van leven bij kinderen is gebaseerd op gerandomiseerd onderzoek en start derhalve hoog en werd met twee niveaus verlaagd vanwege het zeer beperkte aantal patiënten (imprecisie) naar laag.

Montelukast versus antihistaminica (PICO 5)

Klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen

Klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen (symptomen) werden gerapporteerd door 7 studies (Andhale, 2016; Ciebiada, 2006; Kaur, 2017; Kurowski, 2004; Lombardo, 2006; Rajeshkar, 2018; Wei, 2016), indien beschikbaar is de totaal score/ composite score gerapporteerd.

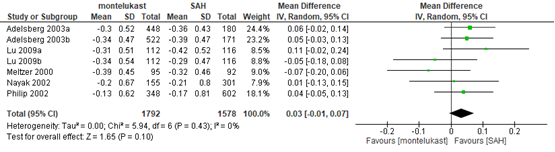

Wei (2016) rapporteerde een composite symptoms score (CSS). Het gepoolde effect was

-0,03 (95% BI -0,01 tot 0,07) (figuur 11).

Figuur 11 CSS montelukast vergeleken met antihistaminica. Bron: Wei, 2016

Z: p-waarde van gepoolde effect; df: degrees of freedom (vrijheidsgraden); I2: statistische heterogeniteit; CI: betrouwbaarheidsinterval

Rajashekar (2018) rapporteerde een scoringssysteem gebaseerd op het totaal van vijf neussymptomen (T5NSS).

In de groep behandeld met montelukast werd een significante afname in de T5NSS gerapporteerd (baseline 161,72, SD 8,87; 4 weken 145,66, SD 7,7), ook in de groep behandeld met ebastine (baseline 157,89, SD 9,47; 4 weken 142,53, SD 9,5) werd een significante afname gerapporteerd. Na 4 weken was er echter geen significant verschil tussen de behandelgroepen (3,13 95%BI -0,91 tot 7,17).

Kaur (2017) rapporteerde symptoomscores voor niezen en neusuitvloed/rhinorrhoe na 2, 4 en 6 weken behandeling. Na 2 weken werd voor niezen een verschil gerapporteerd in het voordeel van levocetrizine ten opzichte van montelukast en andere SAHs. Na 4 en 6 weken werden er geen significante verschillen gerapporteerd tussen de behandelarmen op niezen en nasal discharge/rhinorrhoe.

Andhale (2016) rapporteerde in zowel de groep behandeld met montelukast als de groep behandeld met levocetirizine voor alle symptomen (zowel overdag en ’s nachts) significante afname na twee weken. De gemiddelde afname op de VAS-schaal (0-10) in de symptomen overdag was 3,2 voor de groep behandeld met montelukast en 2,8 voor de groep behandeld met levocetirizine. De gemiddelde afname op de VAS-schaal in de symptomen ’s nachts was 2,1 in de groep behandeld met montelukast en 2,3 in de groep behandeld met levocetirizine. Er werden geen verschillen in effectiviteit tussen de groepen gerapporteerd.

Ciebiada (2011) rapporteerde congestion symptoms. In de groep behandeld met montelukast werd op dag 42 een afname van 1,5 gerapporteerd en in de groep behandeld met levocetirizine een afname van 1,65 ten opzichte van baseline metingen (gemiddelde verschil 0,15 95%BI 0,02 tot 0,28).

Lombardo (2006) rapporteerde na 4 weken geen verschil in DNSS (0,09 95%BI -0,13 tot 0,31) tussen de groep behandeld met levocetirizine (gemiddeld effect 0,43, SD 0,74) en in de groep montelukast (gemiddeld effect 0,34, SD 0,82). Ook voor NSS (0,1 95%BI -0,10 tot 0,31) en DES (-0,06 95%BI -0,06 tot 0,38) werden geen verschil in effect tussen de groepen gerapporteerd.

Kurowski (2004) vond na 6 weken geen significante verschillen in de totale symptoms score tussen de groep behandeld met montelukast en de groep behandeld met cetirizine (resultaten herleidbaar uit figuur 12), symptoomscore groep montelukast 1,2; symptoomscore cetirizine 1,0)

Kinderen

Chen (2006) rapporteerde in de groep behandeld met montelukast een significant grotere afname in TSS met-0,60 (SD 0,25) in de groep behandeld met cetirizine ten opzichte van een afname in de groep behandeld met montelukast van -0,43 (SD 0,23) (p < 0,05).

Hsieh (2004) rapporteerde na 12 weken een significant grotere afname in TSS in de groep behandeld met cetirizine (afname van 8,8 op baseline naar 3,3 op 12 weken) vergeleken met de groep behandeld met montelukast (afname van 8,9 naar 6,2 op 12 weken) (P<0,001).

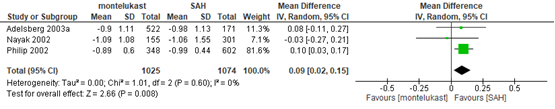

Kwaliteit van leven

Wei (2016) rapporteerde de RQLQ; het gepoolde effect was 0,09 (95%BI 0,02 tot 0,15) (figuur 12). Lombardo (2006) rapporteerde een verandering in de RQLQ score (schaal van 0-6) in de groep behandeld met montelukast van 0,64 ten opzichte van 0,78 in de groep behandeld met levocetirizine.

Figuur 12 RQLQ montelukast vergeleken met antihistamine. Bron: Wei, 2016

Z: p-waarde van gepoolde effect; df: degrees of freedom (vrijheidsgraden); I2: statistische heterogeniteit; CI: betrouwbaarheidsinterval

Kinderen

De PRQLQ werd in twee studies gerapporteerd (Hsieh, 2004; Chen, 2006). Chen (2006) rapporteerde een verschil in PRQLQ in de groep behandeld met cetirizine van -31,15 (SD 23,36) en opzichte van -19,15 (SD 20,71) in de groep behandeld met montelukast (gemiddeld verschil: 12,0 95%BI -1,7 tot 25,7). De studie van Hsieh (2004) rapporteerde geen resultaten.

Bijwerkingen

Twee studies in Wei, 2016 (Meltzer 2000; Nayak, 2002) en Lombardo (2006) rapporteerden bijwerkingen van montelukast vergeleken met loratadine. Nayak (2002) rapporteerde in de groep behandeld met montelukast bij 5% bijwerkingen (vermoeidheid, hoofdpijn en anders) en in de groep behandeld met loratadine bij 6% bijwerkingen (vermoeidheid, hoofdpijn en anders). Meltzer (2000) rapporteerde hoofdpijn in de groep behandeld met montelukast bij 5,3% en in de groep behandeld met loratadine bij 8,7%. Lombardo (2006) rapporteerde in beide groepen geen bijwerkingen.

Kinderen

Hsieh (2004) rapporteerde geen significante verschillen in bijwerkingen tussen de studiearmen. In de groep behandeld met cetirizine werden bijwerkingen gerapporteerd bij één patiënt (sufheid) en bij één patiënt in de groep behandeld met montelukast (hoofdpijn).

Bewijskracht van de literatuur

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen is gebaseerd op gerandomiseerd onderzoek en start hoog en werd verlaagd met een niveau gezien de beperkingen in onderzoeksopzet (risk of bias) naar redelijk.

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat kwaliteit van leven is gebaseerd op gerandomiseerd onderzoek en start hoog en is met twee niveaus verlaagd naar laag gezien het overschrijden van de grenzen van klinische relevantie.

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat bijwerkingen is gebaseerd op gerandomiseerd onderzoek en start hoog en is met één niveau verlaagd naar redelijk gezien het beperkt aantal patiënten (imprecisie).

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaten klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen en kwaliteit van leven bij kinderen is gebaseerd op gerandomiseerd onderzoek en start hoog en is met 2 niveaus verlaagd naar laag gezien het geringe aantal patiënten (imprecisie).

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat bijwerkingen bij kinderen is gebaseerd op gerandomiseerd onderzoek en start hoog en is met drie niveaus verlaagd naar zeer laag gezien het zeer beperkt aantal patiënten (slechts 1 studie en 2 patiënten met bijwerkingen, imprecisie).

Zoeken en selecteren

Om de uitgangsvraag te kunnen beantwoorden is er een systematische literatuuranalyse verricht naar de volgende zoekvraag (vragen):

Azelastine fluticasone versus nasale corticosteroïden

Wat is de effectiviteit van azelastine/fluticason (Dymista) bij patiënten met een allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen in vergelijking met nasale corticosteroïden (eventueel in combinatie met orale antihistaminica)?

P: kinderen, volwassenen en zwangere vrouwen met allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen;

I: nasale azelastine/fluticason (Dymista);

C: nasale corticosteroïden (evt. In combinatie met orale antihistaminica);

O: klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen, kwaliteit van leven, bijwerkingen.

Orale antihistaminica versus nasale corticosteroïden

Wat is de effectiviteit van orale antihistaminica bij patiënten met een allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen in vergelijking met nasale corticosteroïden?

P: kinderen, volwassenen en zwangere vrouwen met allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen;

I: orale antihistaminica (H1 antagonisten);

C: nasale corticosteroïden;

O: klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen, kwaliteit van leven, bijwerkingen.

Orale antihistaminica versus nasale antihistaminica

Wat is de effectiviteit van orale antihistaminica bij patiënten met een allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen in vergelijking met nasale antihistaminica?

P: kinderen, volwassenen en zwangere vrouwen met allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen;

I: orale antihistaminica (H1 antagonisten);

C: nasale antihistaminica;

O: klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen, kwaliteit van leven, bijwerkingen.

Leukotrieën receptor antagonisten versus placebo

Wat is de effectiviteit van leukotrieën receptor antagonisten bij patiënten met een allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen in vergelijking met placebo?

P: kinderen, volwassenen en zwangere vrouwen met allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen;

I: leukotrieën receptor antagonisten;

C: placebo;

O: klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen, kwaliteit van leven, bijwerkingen.

Leukotrieën receptor antagonisten versus antihistaminica

Wat is de effectiviteit van leukotrieën receptor antagonisten bij patiënten met een allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen in vergelijking met orale en nasale antihistaminica?

P: kinderen, volwassenen en zwangere vrouwen met allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen;

I: leukotrieën receptor antagonisten;

C: antihistaminica;

O: klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen, kwaliteit van leven, bijwerkingen.

Relevante uitkomstmaten

De werkgroep achtte klachten ten gevolge van allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen (meestal beschreven door middel van de total symptom score) en kwaliteit van leven voor de besluitvorming cruciale uitkomstmaten; en adverse events en ziekteverzuim voor de besluitvorming belangrijke uitkomstmaten.

De werkgroep definieerde niet á priori de genoemde uitkomstmaten, maar hanteerde de in de studies gebruikte definities.

De werkgroep definieerde voor geen van de uitkomstmaten klinische (patiënt) relevante verschillen, maar sloot aan bij de door GRADE aangegeven default grenzen van 0,5 SD voor continue uitkomstmaten, RR < 0,75 of > 1,25) (GRADE recommendation) of Standardized mean difference (SMD=0,2 (klein); SMD=0,5 (matig); SMD=0,8 (groot).

Zoeken en selecteren (Methode)

Azelastine fluticasone versus nasale corticosteroïden (PICO 1)

In de databases Medline (via OVID), Embase (via Embase.com) is op 4 november 2018 met relevante zoektermen gezocht naar relevante literatuur. De zoekverantwoording is weergegeven onder het tabblad Verantwoording. De literatuurzoekactie leverde 301 treffers op. Studies werden geselecteerd op grond van de volgende selectiecriteria: betrof het de juiste medicatie, originele publicaties en de geselecteerde uitkomstmaten. Provocatiestudies of studies met een medicijn die niet beschikbaar is in Nederland werden geëxcludeerd. Op basis van titel en abstract werden in eerste instantie acht studies voorgeselecteerd. Na raadpleging van de volledige tekst, werden vervolgens drie studies geëxcludeerd (zie exclusietabel onder het tabblad Verantwoording), en vijf publicaties die vier studies beschrijven definitief geselecteerd.

Orale antihistaminica versus nasale antihistaminica of nasale corticosteroïden (PICO 2 en 3)

Er is een overkoepelende search verricht voor PICO 2 en 3. In de databases Medline (via OVID), Embase (via Embase.com) is op 7 november 2018 met relevante zoektermen gezocht naar relevante literatuur. De zoekverantwoording is weergegeven onder het tabblad Verantwoording. De literatuurzoekactie leverde 468 treffers op waarvan 376 RCT’s en 92 SR. Studies werden geselecteerd op grond van de volgende selectiecriteria: betrof de juiste medicatie, originele publicaties en de geselecteerde uitkomstmaten. Provocatiestudies of studies met een medicijn die niet beschikbaar is in Nederland werden geëxcludeerd. Op basis van titel en abstract werden in eerste instantie 83 studies voorgeselecteerd. Na raadpleging van de volledige tekst, werden vervolgens 56 studies geëxcludeerd (zie exclusietabel onder het tabblad Verantwoording), en 27 studies definitief geselecteerd.

Leukotrieën receptor antagonisten versus placebo of antihistaminica (PICO 4 en 5)

Er is een overkoepelende search verricht voor PICO 4 en 5. In de databases Medline (via OVID), Embase (via Embase.com) is op 4 november 2018 met relevante zoektermen gezocht naar relevante literatuur. De zoekverantwoording is weergegeven onder het tabblad Verantwoording. De literatuurzoekactie leverde 319 treffers op waarvan 256 RCT’s en 63 SR. Studies werden geselecteerd op grond van de volgende selectiecriteria: betrof het de juiste medicatie, originele publicaties en de geselecteerde uitkomstmaten. Provocatiestudies of studies met een medicijn die niet beschikbaar is in Nederland werden geëxcludeerd. Op basis van titel en abstract werden in eerste instantie 97 studies voorgeselecteerd. Na raadpleging van de volledige tekst, werden vervolgens 84 studies geëxcludeerd (zie exclusietabel onder het tabblad Verantwoording), en 13 studies definitief geselecteerd.

Resultaten

Azelastine fluticasone versus nasale corticosteroïden (PICO 1)

Vijf publicaties die vier RCT’s beschrijven zijn opgenomen in de literatuuranalyse.

Orale antihistaminica versus nasale corticosteroïden (PICO 2)

Een systematische review met 16 geïncludeerde studies is opgenomen in de literatuuranalyse (Weiner, 1998). Zes van de studies beschreven in deze review voldeden aan de zoekcriteria en zijn geïncludeerd in de literatuursamenvatting, de overige studies zijn buiten beschouwing gelaten. Daarnaast zijn 18 RCT’s opgenomen in de analyse. Als orale antihistaminicum behandeling werden astemizole, loratadine, desloratadine, cetirizine en levocetirizine bestudeerd, als corticosteroïden fluticasone propionate, triamcinolone acetonide, becalmethasone dipropionate, budenoside en ciclesonide. Het merendeel van de studies hanteerde een behandelingsduur van 2 tot 4 weken.

Orale versus nasale antihistaminica (PICO 3)

Zeven studies zijn opgenomen in de literatuuranalyse. De geïncludeerde studies vergeleken orale antihistaminicum behandeling met azelastine nasale spray behandeling bij patiënten met seizoensgebonden allergie van de bovenste luchtwegen.

Leukotrieën receptor antagonisten versus placebo of antihistaminica (PICO 4 en 5)

Dertien studies zijn opgenomen in de literatuuranalyse. De meerderheid van de studies had meerdere behandelarmen met zowel leukotrieën receptor antagonisten, placebo en antihistaminica.

De onderstaande beschrijving van de studies van PICO 2 en 3 zijn daarom gecombineerd, maar de resultaten zijn apart weergegeven.

De belangrijkste studiekarakteristieken en resultaten zijn opgenomen in de evidencetabellen. De beoordeling van de individuele studieopzet (risk of bias) is opgenomen in de risk-of-biastabellen.

Referenties

- Andhale S, Goel HC, Nayak S. Comparison of Effect of Levocetirizine or Montelukast Alone and in Combination on Symptoms of Allergic Rhinitis. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2016 Apr-Jun;58(2):103-5. PubMed PMID: 30182671.

- Andrews CP, Martin BG, Jacobs RL, Mohar DE, Diaz JD, Amar NJ, Kaiser HB, Vandewalker ML, Bernstein J, Toler WT, Prillaman BA, Dalal AA, Lee LA, Philpot EE. Fluticasone furoate nasal spray is more effective than fexofenadine for nighttime symptoms of seasonal allergy. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2009 Mar-Apr;30(2):128-38. doi: 10.2500/aap.2009.30.3204. PubMed PMID: 19463203.

- Berger W, Sher E, Gawchik S, Fineman S. Safety of a novel intranasal formulation of azelastine hydrochloride and fluticasone propionate in children: A randomized clinical trial. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2018; 39(2):110-116. PubMed PMID: 29490769.

- Berger WE, Shah S, Lieberman P, Hadley J, Price D, Munzel U, Bhatia S. Long-term, randomized safety study of MP29-02 (a novel intranasal formulation of azelastine hydrochloride and fluticasone propionate in an advanced delivery system) in subjects with chronic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014; 2(2):179-85. PubMed PMID: 24607046.

- Berger W, Hampel F Jr, Bernstein J, Shah S, Sacks H, Meltzer EO. Impact of azelastine nasal spray on symptoms and quality of life compared with cetirizine oral tablets in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006 Sep;97(3):375-81. PubMed PMID: 17042145.

- Berger WE, White MV; Rhinitis Study Group. Efficacy of azelastine nasal spray in patients with an unsatisfactory response to loratadine. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003 Aug;91(2):205-11. PubMed PMID: 12952117.

- Bernstein DI, Levy AL, Hampel FC, Baidoo CA, Cook CK, Philpot EE, Rickard KA. Treatment with intranasal fluticasone propionate significantly improves ocular symptoms in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004 Jun;34(6):952-7. PubMed PMID: 15196285.

- Bhatia S, Baroody FM, deTineo M, Naclerio RM. Increased nasal airflow with budesonide compared with desloratadine during the allergy season. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005 Mar;131(3):223-8. PubMed PMID: 15781762.

- Bisgaard H, Skoner D, Boza ML, Tozzi CA, Newcomb K, Reiss TF, Knorr B, Noonan G. Safety and tolerability of montelukast in placebo-controlled pediatric studies and their open-label extensions. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009 Jun;44(6):568-79. doi:10.1002/ppul.21018. Review. PubMed PMID: 19449366.

- Carr W, Bernstein J, Lieberman P, Meltzer E, Bachert C, Price D, Munzel U, Bousquet J. A novel intranasal therapy of azelastine with fluticasone for the treatment of allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012; 129(5):1282-1289.e10. PubMed PMID: 22418065.

- Charpin D, Godard P, Garay RP, Baehre M, Herman D, Michel FB. A multicentre clinical study of the efficacy and tolerability of azelastine nasal spray in the treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis: a comparison with oral cetirizine. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1995;252(8):455-8. PubMed PMID: 8719584.

- Charpin D, Vervloet D. Treating seasonal rhinitis: antihistamines or intranasal corticosteroids? European Respiratory Review, 1994, 256-256.

- Chen ST, Lu KH, Sun HL, Chang WT, Lue KH, Chou MC. Randomized placebo-controlled trial comparing montelukast and cetirizine for treating perennial allergic rhinitis in children aged 2-6 yr. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2006 Feb;17(1):49-54. PubMed PMID: 16426255.

- Ciebiada M, Górska-Ciebiada M, DuBuske LM, Górski P. Montelukast with desloratadine or levocetirizine for the treatment of persistent allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006 Nov;97(5):664-71. PubMed PMID:17165277.

- Ciebiada M, Gorska-Ciebiada M, Barylski M, Kmiecik T, Gorski P. Use of montelukast alone or in combination with desloratadine or levocetirizine in patients with persistent allergic rhinitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2011 Jan-Feb;25(1):e1-6. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2011.25.3540. PubMed PMID: 21711959.

- Conde Hernández DJ, Palma Aqilar JL, Delgado Romero J. Comparison of azelastine nasal spray and oral ebastine in treating seasonal allergic rhinitis. Curr Med Res Opin. 1995;13(6):299-304. PubMed PMID: 8829888.

- Condemi J, Schulz R, Lim J. Triamcinolone acetonide aqueous nasal spray versus loratadine in seasonal allergic rhinitis: efficacy and quality of life. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000 May;84(5):533-8. PubMed PMID: 10831008.

- Corren J, Storms W, Bernstein J, Berger W, Nayak A, Sacks H; Azelastine Cetirizine Trial No. 1 (ACT 1) Study Group. Effectiveness of azelastine nasal spray compared with oral cetirizine in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Clin Ther. 2005 May;27(5):543-53. PubMed PMID: 15978303.

- D'Ambrosio FP, Gangemi S, Merendino RA, Arena A, Ricciardi L, Bagnato GF. Comparative study between fluticasone propionate and cetirizine in the treatment of allergic rhinitis. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 1998 Nov-Dec;26(6):277-82.Erratum in: Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 1999 May-Jun;27(3):173. PubMed PMID:9934406.

- Ellis AK, Zhu Y, Steacy LM, Walker T, Day JH. A four-way, double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled study to determine the efficacy and speed of azelastine nasal spray, versus loratadine, and cetirizine in adult subjects with allergen-induced seasonal allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2013 May 1;9(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-9-16. eCollection 2013. PubMed PMID:23635091; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3655060.

- Fokkens WJ, Scadding GK. Perennial rhinitis in the under 4s: a difficult problem to treat safely and effectively? A comparison of intranasal fluticasone propionate and ketotifen in the treatment of 2-4-year-old children with perennial rhinitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2004 Jun;15(3):261-6. PubMed PMID: 15209960.

- Ford LB, Matz J, Hankinson T, Prillaman B, Georges G. A comparison of fluticasone propionate nasal spray and cetirizine in ragweed fall seasonal allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2015 Jul-Aug;36(4):313-9. doi:10.2500/aap.2015.36.3860. PubMed PMID: 26108088.

- Frølund L. Efficacy of an oral antihistamine, loratadine, as compared with a nasal steroid spray, beclomethasone dipropionate, in seasonal allergic rhinitis. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1991 Dec;16(6):527-31. PubMed PMID: 1685945.

- Gambardella R. A comparison of the efficacy of azelastine nasal spray and loratidine tablets in the treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis. J Int Med Res.1993 Sep-Oct;21(5):268-75. PubMed PMID: 7906659.

- Gani F, Lombardi C, Barrocu L, Landi M, Ridolo E, Bugiani M, Rolla G, Senna G,Passalacqua G. The control of allergic rhinitis in real life: a multicentre cross-sectional Italian study. Clin Mol Allergy. 2018 Feb 2;16:4. doi:10.1186/s12948-018-0082-y. eCollection 2018. PubMed PMID: 29434524; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5797368.

- Gawchik SM, Lim J. Comparison of intranasal triamcinolone acetonide with oral loratadine in the treatment of seasonal ragweed-induced allergic rhinitis. Am J Manag Care. 1997 Jul;3(7):1052-8. PubMed PMID: 10173369.

- Hampel FC, Ratner PH, Van Bavel J, Amar NJ, Daftary P, Wheeler W, Sacks H. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of azelastine and fluticasone in a single nasal spray delivery device. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010 Aug;105(2):168-73. PubMed PMID: 20674829.

- Hsieh JC, Lue KH, Lai DS, Sun HL, Lin YH. A comparison of cetirizine and montelukast for treating childhood perennial allergic rhinitis. Pediatric Asthma, Allergy & Immunology, 2004; 17(1), 59-69.

- Jordana G, Dolovich J, Briscoe MP, Day JH, Drouin MA, Gold M, Robson R, Stepner N, Yang W. Intranasal fluticasone propionate versus loratadine in the treatment of adolescent patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996 Feb;97(2):588-95. PubMed PMID: 8621843.

- Kaszuba SM, Baroody FM, deTineo M, Haney L, Blair C, Naclerio RM. Superiority of an intranasal corticosteroïd compared with an oral antihistamine in the as-needed treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis. Arch Intern Med. 2001 Nov 26;161(21):2581-7. PubMed PMID: 11718589.

- Kaur, Gurpreet, Rachna Dhingra, and Manjinder Singh. "RESEARCH ARTICLE Assessment of Clinical Effectiveness of Various Drugs in the Patients of Allergic Rhinitis visiting Tertiary Care Hospital of Punjab, India."

- Keith PK, Desrosiers M, Laister T, Schellenberg RR, Waserman S. The burden of allergic rhinitis (AR) in Canada: perspectives of physicians and patients.Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2012 Jun 1;8(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-8-7. PubMed PMID: 22656186; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3490734.

- Kim CH, Kim JK, Kim HJ, Cho JH, Kim JS, Kim YD, Lee HM, Kim SW, Cho KS, Lee SH, Rhee CS, Dhong HJ, Rha KS, Yoon JH. Comparison of intranasal ciclesonide,oral levocetirizine, and combination treatment for allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2015 Mar;7(2):158-66. doi: 10.4168/aair.2015.7.2.158. Epub 2014 Dec 18. PubMed PMID: 25729623; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4341337.

- Kulapaditharom B, Pornprasertsuk K, Boonkitticharoen V. Clinical assessment of levocetirizine and budesonide in treatment of persistent allergic rhinitis regarding to symptom severity. J Med Assoc Thai. 2010 Feb;93(2):215-23. PubMed PMID: 20302004.

- Kurowski M, Kuna P, Górski P. Montelukast plus cetirizine in the prophylactic treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis: influence on clinical symptoms and nasal allergic inflammation. Allergy. 2004 Mar;59(3):280-8. PubMed PMID: 14982509.

- Lombardo G, Quattrocchi P, Lombardo GR, Galati P, Giannetto L, Barresi L. Concomitant levocetirizine and montelukast in the treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis: Influence on clinical symptoms. Italian Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2006;16:63-68

- Malizia V, Fasola S, Ferrante G, Cilluffo G, Gagliardo R, Landi M, Montalbano L, Marchese D, La Grutta S. Comparative Effect of Beclomethasone Dipropionate and Cetirizine on Acoustic Rhinometry Parameters in Children With Perennial Allergic Rhinitis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2018 Dec;28(6):392-400. doi: 10.18176/jiaci.0263. Epub 2018 Apr 24. PubMed PMID:29688172.

- Meltzer EO, Philip G, Weinstein SF, LaForce CF, Malice MP, Dass SB, Santanello NC, Reiss TF. Montelukast effectively treats the nighttime impact of seasonal allergic rhinitis. Am J Rhinol. 2005 Nov-Dec;19(6):591-8. PubMed PMID: 16402647.

- Okubo K, Baba K. Therapeutic effect of montelukast, a cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 antagonist, on Japanese patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Allergol Int. 2008 Sep;57(3):247-55. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.O-07-515. Epub 2008 Jul 1. PubMed PMID: 18566548.

- Patel P, Philip G, Yang W, Call R, Horak F, LaForce C, Gilles L, Garrett GC, Dass SB, Knorr BA, Reiss TF. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of montelukast for treating perennial allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005 Dec;95(6):551-7. PubMed PMID: 16400895.

- Philip G, Nayak AS, Berger WE, Leynadier F, Vrijens F, Dass SB, Reiss TF. The effect of montelukast on rhinitis symptoms in patients with asthma and seasonal allergic rhinitis. Allergologie 2005; 28(9):343-354

- Price D, Shah S, Bhatia S, Bachert C, Berger W, Bousquet J, Carr W, Hellings P, Munzel U, Scadding G, Lieberman P. A new therapy (MP29-02) is effective for the long-term treatment of chronic rhinitis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2013;23(7):495-503. PubMed PMID: 24654314.

- Rajashekar, Y. R., and S. N. Shobha. "Randomized prospective double-blind comparative clinical study of ebastine and its combined preparation of montelukast in persistent allergic rhinitis." National Journal of Physiology, Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2018: 8.3: 319-324.

- Ratner PH, van Bavel JH, Martin BG, Hampel FC Jr, Howland WC 3rd, Rogenes PR, Westlund RE, Bowers BW, Cook CK. A comparison of the efficacy of fluticasone propionate aqueous nasal spray and loratadine, alone and in combination, for the treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis. J Fam Pract. 1998 Aug;47(2):118-25.PubMed PMID: 9722799.

- Rinne J, Simola M, Malmberg H, Haahtela T. Early treatment of perennial rhinitis with budesonide or cetirizine and its effect on long-term outcome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002 Mar;109(3):426-32. PubMed PMID: 11897986.

- Sastre J, Mosges R. Local and systemic safety of intranasal corticosteroids. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2012;22(1):1-12. Review. PubMed PMID: 22448448.

- Spangler DL, Abelson MB, Ober A, Gotnes PJ. Randomized, double-masked comparison of olopatadine ophthalmic solution, mometasone furoate monohydrate nasal spray, and fexofenadine hydrochloride tablets using the conjunctival and nasal allergen challenge models. Clin Ther. 2003 Aug;25(8):2245-67. PubMed PMID: 14512132.

- Wartna JB, Bohnen AM, Elshout G, Pijnenburg MW, Pols DH, Gerth van Wijk RR, Bindels PJ. Symptomatic treatment of pollen-related allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in children: randomized controlled trial. Allergy. 2017 Apr;72(4):636-644. doi:10.1111/all.13056. Epub 2016 Oct 28. PubMed PMID: 27696447.

- Wei C. The efficacy and safety of H1-antihistamine versus Montelukast for allergic rhinitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Pharmacother.2016 Oct;83:989-997. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.08.003. Epub 2016 Aug 11. Review.PubMed PMID: 27522261.

- Weiner JM, Abramson MJ, Puy RM. Intranasal corticosteroids versus oral H1 receptor antagonists in allergic rhinitis: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 1998 Dec 12;317(7173):1624-9. PubMed PMID: 9848901; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC28740.

Evidence tabellen

PICO 1 Azelastine fluticasone versus nasale corticosteroïden

Evidence table for intervention studies

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Carrr, 2012

|

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs (MP4002 (NCT00651118), MP4004 (NCT00740792), and MP4006 (NCT00883168))

Literature search up to (month/year)

A: Hampel, 2010 B: Meltzer, 2012 C: Meltzer, 2013

Study design: RCTs parallel

Setting and Country: Multicentre, outpatient study in USA, Germany, Belgium and UK

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: funded by Meda Pharmaceuticals, Inc |

Inclusion criteria SR: Subjects (>12 years old) with a minimum 2-year history of SAR, significant current clinical rhinitis symptomatology, and a positive skin prick test response to relevant pollen were randomized. All subjects had moderate-to-severe SARdefined by a reflective total nasal symptom score (rTNSS) of at least 8 of 12, with a congestion score of 2 or 3 during screening. Inclusion criteria for the duration of symptoms for the 3 studies were slightly different.

Exclusion criteria SR: erosion, ulceration, or septal perforation or another disease (eg, sinusitis, rhinitis medicamentosa, polyposis, respiratory tract infection (within 14 days of screening), asthma (except intermittent asthma)), significant pulmonary disease, or symptomatic cardiac conditions or were taking concomitant medication that could interfere with the interpretation of study results

Important patient characteristics at baseline: N total at baseline: Intervention: 207+193+448=848 Control: 208+194+445=847

Sex: I: 36% M C: 36% M

Age ± SD: I: 36.7 (14.3) C: 35.9 (14.1)

Groups comparable at baseline? yes |

Describe intervention:

MP29-02 nasal spray (novel formulation of 137 mg of azelastine/50 mg of FP

|

Describe control:

corticosteroid (FP) Placebo spray comprised exactly the same vehicle/ formulation as the active treatments without any active agent

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: 14 days B: 14 days C: 14 days

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Loss-to follow-up: (intervention/control) A: Intervention Control B: Intervention Control C: Intervention Control

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Total symptom score (reduction from baseline): Baseline Change A I: 18.3 (3.0) -5.5 (5.2) n=207 C: 18.2 (3.2) -5.0 (4.7) n=207

B I: 18.2 (3.3) -5.6 (5.2) N=193 C: 18.2 (3.1) -5.0 (5.2) N=189

C I: 19.4 (2.4) -5.6 (5.2) N=448 C: 19.5 (2.4) -5.1 (4.7) N=450

Pooled I: -5.7 (SD 5.3) C: -4.4 (SD 4.8)

Quality of life: A: I: C:

B: I: C:

C: I: C:

Baseline I: -1.6 (SD 1.3) C: -1.4 (SD 1.3)

A I: 4 (2 %) C: 1 (0.5 %) B I: 3 (1.5 %) C: 1 (0.5 %) C I: 3(0.7 %) C: 4 (0.9 %)

Sick leave: Not reported

|

MP29-02 nasal spray (novel formulation of 137 mg of azelastine/50 mg of FP

MP 4002 MP 4004 beschreven in Meltzer, 2012 MP 4006

Facultative:

Brief description of author’s conclusion

Personal remarks on study quality, conclusions, and other issues (potentially) relevant to the research question

Level of evidence: GRADE (per comparison and outcome measure) including reasons for down/upgrading

Sensitivity analyses (excluding small studies; excluding studies with short follow-up; excluding low quality studies; relevant subgroup-analyses); mention only analyses which are of potential importance to the research question

Heterogeneity: clinical and statistical heterogeneity; explained versus unexplained (subgroup analysis) |

|

Berger, 2014 EudraCT no. 2011-001368-23

Price, 2013 |

Type of study: open-label RCT

Setting and country: India