Laparoscopische lavage bij diverticulitis

Uitgangsvraag

Is laparoscopische lavage en drainage zonder resectie een veilig alternatief voor Hinchey 3 patiënten?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg bij een patiënt met purulente peritonitis door diverticulitis laparoscopische lavage te verrichten als alternatief voor een sigmoïdresectie maar weeg hierbij de klinische conditie, patiëntkarakteristieken, expertise van de operateur en patiëntvoorkeuren over gewenste uitkomsten mee; meer reïnterventies en morbiditeit op korte termijn; minder re-operaties, minder stoma’s en lagere kosten op lange termijn.

Overweeg om bij het verrichten van laparoscopische lavage het infiltraat niet te verwijderen of in grote mate te manipuleren om te voorkomen dat een gedekte perforatie alsnog een vrije perforatie wordt.

Overwegingen

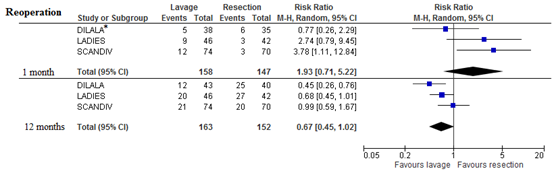

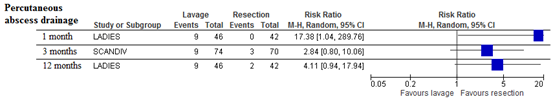

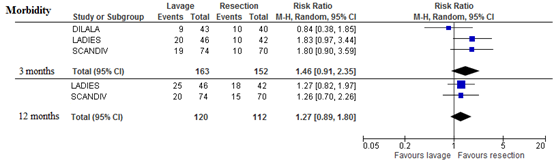

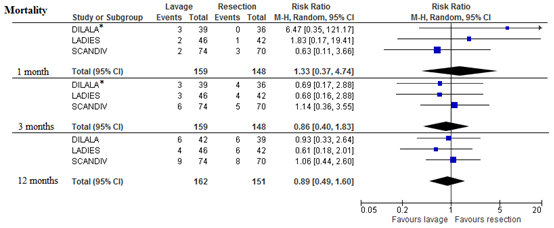

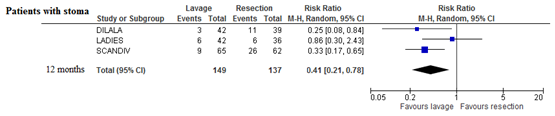

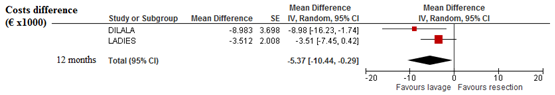

Following several observational studies with promising results of laparoscopic lavage in Hinchey stage 3 diverticulitis patients (success rate of 96%, mortality of 2% and morbidity of 10% (Toorenvliet, 2010), three randomized clinical could not confirm these success rates. Laparoscopic lavage patients needed more short-term (1 month) reoperations (pooled 17% versus 9%; RR 1.93, 95% CI 0.71 to 5.22) and percutaneous reinterventions than patients that underwent immediate sigmoid resection. Also serious morbidity rates were slightly higher in the laparoscopic lavage group after 3 months (pooled 30% versus 20%; RR 1.46, 95% CI 0.91 to 2.35), just as the slightly higher risk of mortality after 1 month (pooled 5% versus 3%; RR 1.33, 95% CI 0.37 to 4.74). In the long-term however, reoperation and mortality occurred slightly less often in the laparoscopic lavage group (pooled 33% versus 51%; RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.02 and pooled 12% versus 13%; RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.60 respectively). Although, the higher number of reoperations in the resection group is mostly caused by a higher number of stoma reversal surgeries. Although this type of surgery cannot be considered as a complication of the initial procedure, stoma reversal is an inevitable consequence of Hartmann’s procedures. An outcome significantly in favour of laparoscopic lavage in long-term was the number of patients with a stoma at 12 months (RR 0.41; 95% CI 0.21 to 0.78). Furthermore, the medical costs were lower in the laparoscopic lavage group with a mean costs savings of €5,370 (95% CI €10,440 - €290). Although the level of evidence is high since it is based on randomized clinical trials, some limitations should also be addressed. The DILALA trial only reported per-protocol analyses of short-term outcomes. This may have caused a bias with reference to the intention-to-treat analyses in the other trials. Particularly the pooled 1 month reoperation risk may have been influenced by this limitation. Furthermore, the SCANDIV trial included patients with an intraoperative diagnosis of Hinchey 1 and 2 diverticulitis (4 patients in the lavage group and 6 patients in the resection group). Since laparoscopic lavage may only be a promising treatment option in Hinchey stage 3 patients, this incorrect composition of the groups may have masked the true treatment effect in Hinchey 3 patients. Consensus about the importance of the different outcomes in determining future treatment strategies is lacking, which is reflected by the differences in definition of primary endpoints in the trials. Reinterventions and morbidity are important outcomes for patients, but a slightly higher rate may be accepted if mortality in the long-term is not increased as a result, especially in the type of patients with perforated diverticulitis (high age and present comorbidity). Percutaneous drainage may even be considered a part of the treatment strategy when performing laparoscopic lavage rather than a complication. Patients may also consider the significantly higher stoma rates at long-term – that are therefore likely to be permanent – in the resection group an important factor impairing their quality of life. On the other hand, the LADIES trial reported significantly more patients with a recurrent episode of acute diverticulitis within 12 months in the laparoscopic lavage group; 20% (9/46) versus 2% (1/42) in the resection group. Based on these three randomized clinical trial, laparoscopic lavage seemed to result in more reverse effects in the short-term and in less reverse effects in the mid-term and long-term including lower costs. However, most found associations were not significant which may be partially caused by the early termination of the LADIES trial. The forthcoming data of the fourth randomized clinical trial (LapLAND trial) may increase the total sample size enabling more firm conclusions. Future results of laparoscopic may be improved by better patient selection. In the LADIES trial, one third of the patients in the resection group showed perforation at pathological examination. Since patients with overt perforation are likely to fail laparoscopic lavage management, similar rates of perforation in the laparoscopic lavage may have worsened the outcomes in this group. Better preoperative diagnostics may identify true Hinchey stage 3 patients more reliably. Based on the results of the three randomized clinical trials, laparoscopic seems to be a safe alternative for sigmoid resection in Hinchey 3 patients. The decision can be customised for each individual patient based on patient characteristics or patient preferences that determine the importance of better short-term results (less reinterventions and lower morbidity rates in the resection group), or better long-term results (less reoperations, less patients with (permanent) stomas and lower costs in de laparoscopic lavage group). Lastly, in these three randomized adhesions to the sigmoid were not to be dissected in the laparoscopic lavage group in order to prevent a covered perforation to become an overt perforation. When performing laparoscopic lavage in daily practice, following this same procedure seems advisable.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Target group of patients: Hinchey 3 diverticulitis

Usually, perforated diverticulitis patients with purulent peritonitis undergo resection of the affected colon segment. However, this is a relatively extensive procedure in patients that can be critically ill and are mostly elderly patients with comorbidities. Laparoscopic lavage without resection may be a less burdensome procedure which has been subject of several randomised controlled trials in recent years.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Redelijk GRADE |

Hoewel niet significant verschillend, lijken laparoscopische lavage patiënten op korte termijn (1 maand) meer re-operaties nodig te hebben. Op lange termijn echter (12 maanden) lijken deze patiënten juist, voornamelijk door een lager aantal opheffen stoma operaties, minder re-operaties te ondergaan dan sigmoïd resectie patiënten.

Bronnen (Angenete, 2016; Schultz, 2015; Schultz, 2017; Thornell, 2016; Vennix, 2015) |

|

Redelijk GRADE |

Op korte termijn (1 maand) hebben laparoscopische lavage patiënten vaker een percutane reïnterventie nodig dan patiënten die een sigmoïd resectie hebben ondergaan.

Bronnen (Schultz, 2015; Vennix, 2015) |

|

Redelijk GRADE |

Hoewel niet significant verschillend, lijken laparoscopische lavage patiënten op korte termijn (binnen 3 maanden) iets meer complicaties te ontwikkelen.

Bronnen (Angenete, 2016; Schultz, 2015; Thornell, 2016; Vennix, 2015) |

|

Redelijk GRADE |

De mortaliteit is niet verschillend tussen laparoscopische lavage en sigmoïd resectie patiënten op korte en lange termijn (1, 3 en 12 maanden).

Bronnen (Angenete, 2016; Schultz, 2015; Thornell, 2016; Vennix, 2015) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Three randomized clinical trials were included; the DILALA trial (Angenete, 2016), the LADIES trial (Vennix, 2015) and the SCANDIV trial (Schultz, 2015). The DILALA trial and the SCANDIV trial reported long-term results in a separate paper (Thornell, 2016; Schultz, 2017). The LADIES trial (Vennix, 2017) and the DILALA trial (Gehrman, 2016) reported costs in separate papers. The DILALA and LADIES trials only included patients with intraoperatively confirmed, as far as possible, Hinchey stage 3 diverticulitis (purulent peritonitis without faecal peritonitis or overt perforation). The SCANDIV trial included all patients with free air on computed tomography that needed urgent surgery due to clinical peritonitis. Therefore, this study includes patients with intraoperative signs of Hinchey stage 1, 2 3 and 4 diverticulitis. Patients with Hinchey stage 1, 2 and 3 were distinguished from Hinchey stage 4 patients and were analyzed as a single group. The laparoscopic lavage procedure was comparable in all three studies; lavage of all quadrants with saline after which a passive drain was placed under antibiotic treatment according to local routines. Regarding the control group, the DILALA trial only performed Hartmann’s procedures (HP), the LADIES and SCANDIV trials performed a Hartmann’s procedure or resection with primary anastomosis. The outcomes reoperation, morbidity and mortality were reported by all three studies, percutaneous abscess drainage was only reported by the LADIES and SCANDIV trial, patients with stoma and costs were only reported by the DILALA and LADIES trial. Most analyses were done according to the intention-to-treat principle. Only the DILALA trial reported results of reoperation and mortality up to 3 months from a per-protocol analysis. The SCANDIV trial reported all results according to a modified intention-to-treat principle in which patients without an intraoperative perforation were excluded. This modified intention-to-treat group is similar to the intention-to-treat groups from other studies since this filtered out the patients without intraoperatively confirmed perforated diverticulitis. The DILALA and LADIES trial filtered out these patients similarly by just randomizing the patients intraoperatively. The DILALA trial did not compare the included patients with patients that were eligible but not included. The SCANDIV trial found only a slightly higher proportion of patients with an ASA score of 3 or higher (14% versus 5%) in the not included patients. The LADIES trial found no differences in baseline characteristics between the included and eligible but not included patients. The LADIES trial was terminated early, after inclusion of 88 out of the planned 264 patients, for safety reasons due to high short-term morbidity and re-intervention rates.

Resultaten

Reoperation

All three RCT’s reported rates of reoperation after laparoscopic lavage or sigmoid resection. The risk of needing reoperation within 1 month was 93% higher but not significantly higher in the laparoscopic lavage group. However, within a follow-up duration of 12 months a trend towards less reoperations in the laparoscopic lavage group, compared to the resection group, was seen (RR 0.67; 95% CI 0.45 to 1.02). This effect is mostly caused by the higher number of stoma reversal operations in the resection group. (Figure 1)

Figure 1 Forest plot for the risk of needing reoperation within 1 or 12 months.

* Results from per-protocol analysis, all other results are from intention-to-treat analyses

Percutaneous reintervention

The need for percutaneous abscess drainage was only reported in two studies at three different follow-up durations. Therefore the number of patients per time point was low. Laparoscopic lavage patients underwent significantly more percutaneous abscess drainages within 1 month. This increased risk decreased and was no longer statistically significant at 3 months or 12 months but remained in favour of the sigmoid resection group.

Figure 2 Forest plot for the risk of needing percutaneous abscess drainage within 1 month, 3 months or 12 months.

Morbidity

All three studies reported morbidity rates at 3 months of follow-up. These rates were defined as morbidity grade 3b or higher according to the Clavien-Dindo classification. Laparoscopic lavage patients had a 46% but non-significantly higher risk for serious morbidity. At 12 months, only the LADIES trial and SCANDIV trial reported morbidity rates yielding a comparable increased risk (RR 1.27; 95% CI 0.89 to 1.80)

Figure 3 Forest plot for the risk of serious morbidity (Clavien-Dindo grade 3b or higher) within 3 and 12 months

Mortality

All three studies reported mortality rates, although the DILALA trial only reported per-protocol results at 1 month and 3 months follow-up. At 1 month of follow-up the risk of mortality was slightly but non-significantly higher in the laparoscopic lavage group. At 3 months and 12 months however, the risk of mortality was respectively 14% and 11% lower in the laparoscopic lavage group. Although, these differences were not statistically significant.

Figure 4 Forest plot for the risk of mortality within 1 month, 3 months and 12 months.

* Results from per-protocol analysis, all other results are from intention-to-treat analyses

Patients with stoma

Part of the patients in the resection group underwent a Hartmann’s procedure, therefore more patients in this group had a stoma during the study. Since not all stoma’s were reversed, significantly less patients had a stoma at 12 months of follow-up in the laparoscopic lavage group (RR 0.41; 95% CI 0.21 to 0.78).

Figure 5 Forest plot for the risk of having a stoma at 12 months follow-up duration.

Costs

Both the DILALA and the LADIES trial reported the medical costs savings at a follow-up duration of 12 months. Both showed costs savings in favour of laparoscopic lavage, resulting in a significant pooled costs savings of €5,370 (95% CI €10,440 - €290).

Figure 6

Bewijskracht van de literatuur

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat re-operaties begon op ‘hoog’ aangezien het bewijs afkomstig is uit gerandomiseerde klinische onderzoeken. Vervolgens is de bewijskracht met 1 niveaus verlaagd gezien het geringe aantal patiënten (imprecisie).

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat percutane reïnterventies begon op ‘hoog’ aangezien het bewijs afkomstig is uit gerandomiseerde klinische onderzoeken. Vervolgens is de bewijskracht met 1 niveau verlaagd gezien het geringe aantal patiënten (imprecisie).

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat complicaties begon op ‘hoog’ aangezien het bewijs afkomstig is uit gerandomiseerde klinische onderzoeken. Vervolgens is de bewijskracht met 1 niveau verlaagd gezien het geringe aantal patiënten (imprecisie).

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat mortaliteit begon op ‘hoog’ aangezien het bewijs afkomstig is uit gerandomiseerde klinische onderzoeken. Vervolgens is de bewijskracht met 1 niveau verlaagd gezien het geringe aantal patiënten (imprecisie).

Zoeken en selecteren

Om de uitgangsvraag te kunnen beantwoorden is er een systematische literatuuranalyse verricht naar de volgende zoekvraag:

Wat zijn de (on)gewenste effecten van laparoscopische lavage en drainage (zonder resectie) ten opzichte van een Hartmann procedure of resectie met primaire anastomose?

Patiënt: Hinchey stadium 3 diverticulitis (purulente peritonitis);

Interventie: laparoscopische lavage en drainage zonder resectie;

Controle: Hartmann procedure of resectie met primaire anastomose;

Outcome: re-operaties, percutane reïnterventies, complicaties, mortaliteit, aantal patiënten met stoma, kosten.

Relevante uitkomstmaten

De werkgroep achtte re-operaties, percutane reïnterventies, complicaties en mortaliteit voor de besluitvorming kritieke uitkomstmaten en het aantal patiënten met stoma en kosten voor de besluitvorming belangrijke uitkomstmaten.

De werkgroep definieerde niet a priori de genoemde uitkomstmaten, maar hanteerde de in de studies gebruikte definities.

Zoeken en selecteren (Methode)

In de databases Medline (OVID), EMBASE en de Cochrane Library (Wiley) is met relevante zoektermen gezocht naar gerandomiseerde klinische onderzoeken. De zoekverantwoording is weergegeven onder het tabblad Verantwoording. De literatuurzoekactie leverde 434 treffers op. Studies werden geselecteerd op grond van de volgende selectiecriteria:

- Volledige tekst artikelen beschikbaar (geen taalrestricties).

- Gerandomiseerde klinische onderzoeken die laparoscopische lavage vergeleken met een resectie (Hartmann procedure dan wel resectie met primaire anastomose) bij volwassen patiënten met geperforeerde diverticulitis (Hinchey 3).

- Minimaal één van de uitkomsten beschreven.

Op basis van titel en abstract werden in eerste instantie 15 studies voorgeselecteerd. Na raadpleging van de volledige tekst, werden vervolgens 8 studies geëxcludeerd (zie exclusietabel onder het tabblad Verantwoording), en 7 studies definitief geselecteerd.

Zeven onderzoeken, waarin resultaten van 3 gerandomiseerde onderzoeken werden gerapporteerd, zijn opgenomen in de literatuuranalyse. De belangrijkste studiekarakteristieken en resultaten zijn opgenomen in de evidence-tabellen. De beoordeling van de individuele studieopzet (risk of bias) is opgenomen in de risk of bias tabellen.

Referenties

- Angenete E, Thornell A, Burcharth J, et al. Laparoscopic lavage is feasible and safe for the treatment of perforated diverticulitis with purulent peritonitis: The first results from the randomized controlled trial DILALA. Annals of surgery.2016;263:117-22.

- Gehrman J, Angenete E, Bjorholt I, et al. Health economic analysis of laparoscopic lavage versus Hartmann's procedure for diverticulitis in the randomized DILALA trial. The British journal of surgery. 2016;103:1539-47.

- Schultz JK, Yaqub S, Wallon C, et al. Laparoscopic Lavage versus Primary Resection for Acute Perforated Diverticulitis: The SCANDIV Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama. 2015;314:1364-75.

- Schultz JK, Wallon C, Blecic L, et al. One-year results of the SCANDIV randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic lavage versus primary resection for acute perforated diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2017;104(10):1382-1392.

- Thornell A, Angenete E, Bisgaard T, et al. Laparoscopic lavage for perforated diverticulitis with purulent peritonitis. Annals of internal medicine. 2016;164:137-45.

- Toorenvliet BR, Swank H, Schoones JW, et al. Laparoscopic peritoneal lavage for perforated colonic diverticulitis: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(9):862-7.

- Vennix S, Musters GD, Mulder IM, et al. Laparoscopic peritoneal lavage or sigmoidectomy for perforated diverticulitis with purulent peritonitis: A multicentre, parallel-group, randomised, open-label trial. The Lancet. 2015;386:1269-77.

- Vennix S, van Dieren S, Opmeer BC, et al. Cost analysis of laparoscopic lavage compared with sigmoid resection for perforated diverticulitis in the Ladies trial. The British journal of surgery. 2017;104:62-8.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Angenete, 2016 DILALA trial |

Type of study: randomized clinical trial

Setting: 9 hospitals

Country: Sweden and Denmark

Source of funding: Alderbertska research foundation, Alice Swenzons foundation, Anna-Lisa and Bror Bjornssons foundation, the Swedish Society of Medicine, the FrF foundation, the Goteborg Medical Society, the Sahlgrenska University Hospital Health Technology Assessment Center, Johan & Jacob Soderberg’s foundation, Magnus Bergvall’s foundation, Ruth and Richard Julin’s foundation, Signe and Olof Wallenius’ foundation, The Swedish Research Council, The Health & Medical Care Committee of the Regional Executive Board, and Region Vastra Gotaland. |

Inclusion criteria: intraoperatively confirmed Hinchey grade 3 (purulent peritonitis and an inflamed part of the colon)

Exclusion criteria: Hinchey grade 4 (fecal contamination) or other pathology at surgery, cancer or other diagnoses than diverticulitis during follow-up

N total at baseline: Intervention: 39 Control: 36

Important prognostic factors2: No significant differences in baseline characteristics

|

Laparoscopic lavage of all 4 quadrants was performed with saline, 3 L or more, of body temperature, until clear fluid was returned. A passive drain was placed in the pelvis in all patients and left in place for at least 24 hours. Both groups were treated postoperatively according to local routines regarding antibiotic treatment, thrombosis prophylaxis and return to oral feeding.

|

Open Hartmann Procedure (HP) was performed through a midline incision. All specimens underwent pathology examination. A passive drain was placed in the pelvis in all patients and left in place for at least 24 hours. Both groups were treated postoperatively according to local routines regarding antibiotic treatment, thrombosis prophylaxis and return to oral feeding. |

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: none

Control: none

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: 1 (2.6%) Reasons not reported

Control: 1 (2.8%) Reasons not reported

|

Reoperation within 30 days (PP): 13.2% (5/38) in LL versus 17.1% (6/35) in HP; p=0.634 Mortality within 30 days (PP): 7.7% (3/39) in LL versus 0.0% (0/36 in HP; p=0.094 Complications within 3 months (PP)*: CD1/2 44.7% (17/38) in LL versus 37.1% (13/35) in HP; p=0.510 CD3a 7.9% (3/38) in LL versus 0.0% (0/35) in HP; p=0.090 CD3b 10.5% (4/38) in LL versus 8.0% (2/35) in HP; p=0.455 CD4a 7.9% (3/38) in LL versus 8.6% (3/35) in HP; p=0.916 CD4b 2.6% (1/38) in LL versus 2.9% (1/35) in HP; p=0.953 CD5 0.0% (0/38) in LL versus 0.0% (0/35) in HP Mortality within 90 days (PP): 7.7% (3/39) in LL versus 11.4% (4/36) in HP; p=0.583 |

Only results reported from per-protocol (PP) analyses.

No comparison between included and eligible but not included patients reported.

*Patients could have more than one complication. |

|

Gehrman, 2016 DILALA trial |

Type of study: randomized clinical trial

Setting: 9 hospitals

Country: Sweden and Denmark

Source of funding: Alderbertska research foundation, Alice Swenzons foundation, Anna-Lisa and Bror Bjornssons foundation, the Swedish Society of Medicine, the FrF foundation, the Goteborg Medical Society, the Sahlgrenska University Hospital Health Technology Assessment Center, Johan & Jacob Soderberg’s foundation, Magnus Bergvall’s foundation, Ruth and Richard Julin’s foundation, Signe and Olof Wallenius’ foundation, The Swedish Research Council, The Health & Medical Care Committee of the Regional Executive Board, and Region Vastra Gotaland. |

Inclusion criteria: intraoperatively confirmed Hinchey grade 3 (purulent peritonitis and an inflamed part of the colon)

Exclusion criteria: Hinchey grade 4 (fecal contamination) or other pathology at surgery, cancer or other diagnoses than diverticulitis during follow-up

N total at baseline: Intervention: 43 Control: 40

Important prognostic factors2: No significant differences in baseline characteristics

|

Laparoscopic lavage of all 4 quadrants was performed with saline, 3 L or more, of body temperature, until clear fluid was returned. A passive drain was placed in the pelvis in all patients and left in place for at least 24 hours. Both groups were treated postoperatively according to local routines regarding antibiotic treatment, thrombosis prophylaxis and return to oral feeding.

|

Open Hartmann procedure was performed through a midline incision. All specimens underwent pathology examination. A passive drain was placed in the pelvis in all patients and left in place for at least 24 hours. Both groups were treated postoperatively according to local routines regarding antibiotic treatment, thrombosis prophylaxis and return to oral feeding. |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 6/43 (14.0%) died and 3/43 (7.0%) lost to follow-up Reasons not reported

Control: 6/40 (15.0%) died and 4/40 (10.0%) lost to follow-up Reasons not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: unknown

Control: unknown

|

Costs within 12 months: €18,025 ± 14,646 in LL versus €27,009 ± 18,445 in HP; p=0.016 Costs difference LL-HP: -€8983 (95% CI -16,232, -1735) |

Costs based on intention-to-treat analyses. |

|

Schultz, 2015 SCANDIV trial |

Type of study: randomized clinical trial

Setting: 21 hospitals

Country: Sweden and Norway

Source of funding: South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority and Akershus University Hospital

|

Inclusion criteria: Patients older than 18 years, ability to tolerate general anaesthesia, abdominal CT showing free air and findings compatible with perforated diverticulitis requiring urgent surgery due to clinical peritonitis

Exclusion criteria: bowel obstruction, pregnancy

N total at baseline: Intervention: 74 Control: 70

Important prognostic factors2: Baseline characteristics similar between groups (no statistical tests provided) |

Intravenous antibiotics according to local practices, after a diagnosis of peritonitis was established. Pneumoperitoneum was preferably obtained by an open transumbilical technique with a 12-mm trocar, using at least 2 additional 5-mm trocars for abdominal access. All quadrants were rinsed before placing a nonsuction drain on each side of the pelvis. Adhesions to the sigmoid were not to be dissected. Time to drain removal was determined by the surgeon. According to the protocol, the abdominal cavity in all patients was rinsed with at least 4L of saline or until drainage was clear.

|

Intravenous antibiotics according to local practices, after a diagnosis of peritonitis was established. The choices of laparoscopic vs open resection, and also of Hartmann procedure vs primary resection and anastomosis(PRA) were determined by surgeon preference and local practices. The diseased colon segment was resected to the level of the rectum(determined as that part of the colon not having taenia coli), with or without mobilization of the splenic flexure. The Hartmann procedure was performed by closing the rectum with a stapling device and marking the blind rectal pouch with a nonabsorbable suture. A colostomy was created through the stoma site, which was marked preoperatively. For PRA, the choice of whether to protect the anastomosis with a diverting stoma or not was determined by the surgeon’s discretion. In all cases, at least 1 drain was placed in the pelvis (either suction or nonsuction per the surgeon’s discretion).The time to drain removal was determined by the surgeon. According to the protocol, the abdominal cavity in all patients was rinsed with at least 4L of saline or until drainage was clear. |

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: none

Control: 1 (1.0%) Reasons not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: none

Control: none

|

Reoperation index admission 16.2% (12/74) in LL versus 4.3% (3/70) in resection group; p=0.03 Reoperation within 90 days 20.3% (15/74) in LL versus 5.7% (4/70) in resection group; p=0.01 Percutaneous abscess drainage within 90 days 12.2% (9/74) in LL versus 4.3% (3/70) in resection group Complications within 3 months: CD3b 14.9% (11/74) in LL versus 5.7% (4/70) in resection group CD4a 1.4% (1/74) in LL versus 1.4% (1/70) in resection group CD4b 1.4% (1/74) in LL versus 0.0% (0/70) in resection group CD5 8.1% (6/74) in LL versus 7.1% (5/70) in resection group Mortality at index admission 2.7% (2/74) in LL versus 4.3% (3/70) in resection group; p=0.68 Mortality within 90 days 8.1% (6/74) in LL versus 7.1% (5/70) in resection group; p=0.99 |

Results from Hinchey 4 patients were excluded. Hinchey 3 patients were not analyzed separately but as a group combined with Hinchey 1 and 2 patients. Laparoscopic lavage group consisted of 3 Hinchey I patients, 1 Hinchey II patients and 70 Hinchey III patients. Resection group consisted of 2 Hinchey I patients, 4 Hinchey II patients and 64 Hinchey III patients.

Results reported from modified intention-to-treat analyses in which patients without intraoperative perforated diverticulitis were excluded.

Reoperation results did not include stoma reversal surgery.

Eligible but not included patients had slightly higher number of patients with ASA >3 (14% vs 5%) than included patients. |

|

Schultz, 2017 SCANDIV trial |

Type of study: randomized clinical trial

Setting: 21 hospitals

Country: Sweden and Norway

Source of funding: South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority and Akershus University Hospital

|

Inclusion criteria: Patients older than 18 years, ability to tolerate general anaesthesia, abdominal CT showing free air and findings compatible with perforated diverticulitis requiring urgent surgery due to clinical peritonitis

Exclusion criteria: bowel obstruction, pregnancy

N total at baseline: Intervention: 74 Control: 70

Important prognostic factors2: Baseline characteristics similar between groups (no statistical tests provided) |

Intravenous antibiotics according to local practices, after a diagnosis of peritonitis was established. Pneumoperitoneum was preferably obtained by an open transumbilical technique with a 12-mm trocar, using at least 2 additional 5-mm trocars for abdominal access. All quadrants were rinsed before placing a nonsuction drain on each side of the pelvis. Adhesions to the sigmoid were not to be dissected. Time to drain removal was determined by the surgeon. According to the protocol, the abdominal cavity in all patients was rinsed with at least 4L of saline or until drainage was clear.

|

Intravenous antibiotics according to local practices, after a diagnosis of peritonitis was established. The choices of laparoscopic vs open resection, and also of Hartmann procedure vs primary resection and anastomosis(PRA) were determined by surgeon preference and local practices. The diseased colon segment was resected to the level of the rectum(determined as that part of the colon not having taenia coli), with or without mobilization of the splenic flexure. The Hartmann procedure was performed by closing the rectum with a stapling device and marking the blind rectal pouch with a nonabsorbable suture. A colostomy was created through the stoma site, which was marked preoperatively. For PRA, the choice of whether to protect the anastomosis with a diverting stoma or not was determined by the surgeon’s discretion. In all cases, at least 1 drain was placed in the pelvis (either suction or nonsuction per the surgeon’s discretion).The time to drain removal was determined by the surgeon. According to the protocol, the abdominal cavity in all patients was rinsed with at least 4L of saline or until drainage was clear. |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: none

Control: 1 (1.0%) Reasons not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: none

Control: none

Quality of life and functional outcome analyses were performed in 62 laparoscopic lavage patients and 52 resection patients due to lost to follow-up. However these analyses were performed in all Hinchey stages including Hinchey 4 |

Reoperation within 12 months 28.4% (21/74) in LL versus 28.6% (20/70) in resection group; p=1.000 Complications within 12 months: CD3b 16.2% (12/74) in LL versus 8.6% (6/70) in resection group CD4a 1.4% (1/74) in LL versus 2.9% (2/70) in resection group CD4b 1.4% (1/74) in LL versus 1.4% (1/70) in resection group CD5 8.1% (6/74) in LL versus 8.6% (6/70) in resection group Mortality within 12 months 12.2% (9/74) in LL versus 11.4% (8/70) in resection group Patients with stoma at 12 months 13.8% (9/65) in LL versus 41.9% (26/62) in resection group; p<0.001 |

Results from Hinchey 4 patients were excluded. Hinchey 3 patients were not analyzed separately but as a group combined with Hinchey 1 and 2 patients. Laparoscopic lavage group consisted of 3 Hinchey I patients, 1 Hinchey II patients and 70 Hinchey III patients. Resection group consisted of 2 Hinchey I patients, 4 Hinchey II patients and 64 Hinchey III patients.

Results reported from modified intention-to-treat analyses in which patients without intraoperative perforated diverticulitis were excluded.

Reoperation results included stoma reversal surgery. |

|

Thornell 2016 DILALA trial |

Type of study: randomized clinical trial

Setting: 9 hospitals

Country: Sweden and Denmark

Source of funding: Alderbertska research foundation, Alice Swenzons foundation, Anna-Lisa and Bror Bjornssons foundation, the Swedish Society of Medicine, the FrF foundation, the Goteborg Medical Society, the Sahlgrenska University Hospital Health Technology Assessment Center, Johan & Jacob Soderberg’s foundation, Magnus Bergvall’s foundation, Ruth and Richard Julin’s foundation, Signe and Olof Wallenius’ foundation, The Swedish Research Council, The Health & Medical Care Committee of the Regional Executive Board, and Region Vastra Gotaland. |

Inclusion criteria: intraoperatively confirmed Hinchey grade 3 (purulent peritonitis and an inflamed part of the colon)

Exclusion criteria: Hinchey grade 4 (fecal contamination) or other pathology at surgery, cancer or other diagnoses than diverticulitis during follow-up

N total at baseline: Intervention: 43 Control: 40

Important prognostic factors2: No significant differences in baseline characteristics

|

Laparoscopic lavage of all 4 quadrants was performed with saline, 3 L or more, of body temperature, until clear fluid was returned. A passive drain was placed in the pelvis in all patients and left in place for at least 24 hours. Both groups were treated postoperatively according to local routines regarding antibiotic treatment, thrombosis prophylaxis and return to oral feeding.

|

Open Hartmann procedure was performed through a midline incision. All specimens underwent pathology examination. A passive drain was placed in the pelvis in all patients and left in place for at least 24 hours. Both groups were treated postoperatively according to local routines regarding antibiotic treatment, thrombosis prophylaxis and return to oral feeding. |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 6/43 (14.0%) died and 3/43 (7.0%) lost to follow-up (excluded from follow-up due to other diagnosis)

Control: 6/40 (15.0%) died and 4/40 (10.0%) lost to follow-up (withdrew consent (n=1) other diagnosis (n=2) sigmoid resection with primary anastomosis (n=1)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: none

Control: none

|

Reoperation within 12 months 27.9% (12/43) in LL versus 62.5% (25/40) in HP (including stoma reversal; n=21) Complications within 3 months*: CD1/2 59.5% (25/42) in LL versus 41.0% (16/39) in HP CD3a 9.5% (4/42) in LL versus 2.6% (1/39) in HP CD3b 14.3% (6/42) in LL versus 17.9% (7/39) in HP CD4a 7.1% (3/42) in LL versus 10.3% (4/39) in HP CD4b 2.4% (1/42) in LL versus 2.6% (1/39) in HP ‘Serious adverse event’ within 90 days** 20.9% (9/43) in LL versus 25.0% (10/40) in HP Mortality within 12 months 14.3% (6/42) in LL versus 15.4% (6/39) in HP Patients with stoma at 12 months 7.1% (3/42) in LL versus 28.2% (11/39) in HP |

Results reported from intention-to-treat analyses.

No comparison between included and eligible but not included patients reported.

Reoperation results included stoma reversal surgery.

*Patients could have more than one complication. ** No definition of ‘serious’ adverse events was reported in study protocol or results paper |

|

Vennix, 2015 LADIES trial |

Type of study: randomized clinical trial

Setting: 30 hospitals

Country: the Netherlands, Belgium, Italy

Source of funding: Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development |

Inclusion criteria: Intraoperatively confirmed Hinchey 3 patients

Exclusion criteria: dementia, previous sigmoidectomy, pelvic irradiation, chronic treatment with high-dose steroids (>20 mg daily), being aged younger than 18 years or older than 85 years, and having preoperative shock needing inotropic support.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 46 Control: 42

Important prognostic factors2: ASA 3/4 18% (8/46) in LL versus 36% (15/42) in resection group. No other significant differences in baseline characteristics between groups. |

To determine the presence of a sigmoid perforation, adherent tissues were carefully removed, but when firmly adherent, they were left in place. Laparoscopic lavage was done by irrigation with up to 6 L of warm saline throughout the abdominal cavity. A Douglas drain was inserted in the right lateral port site. Sigmoidectomy with primary anastomosis was done according to the guidelines of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons and the creation of a defunctioning ileostomy was at the discretion of the surgeon. |

To determine the presence of a sigmoid perforation, adherent tissues were carefully removed, but when firmly adherent, they were left in place. Sigmoidectomy with primary anastomosis was done according to the guidelines of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons and the creation of a defunctioning ileostomy was at the discretion of the surgeon. |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 2.2% (1/46) (moved house) Control: 0.0% (0/42)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: none

Control: none

|

Major morbidity or mortality within 30 days 39.1% (18/46) in LL versus 19.1% (8/42) in resection group; p=0.043 Major morbidity or mortality within 12 months 65.2% (30/46) in LL versus 59.5% (25/42) in resection group; p=0.580 Reoperation within 30 days or in-hospital 19.6% (9/46) in LL versus 7.1% (3/42) in resection group; p=0.123 Reoperation within 12 months 43.5% (20/46) in LL versus 64.3% (27/42) in resection group Percutaneous abscess drainage within 30 days or in-hospital 19.6% (9/46) in LL versus 0.0% (0/42) in resection group; p=0.003 Percutaneous abscess drainage within 12 months 19.6% (9/46) in LL versus 4.8% (2/42) in resection group; p=0.051 Major morbidity within 30 days or in-hospital 39.1% (18/46) in LL versus 19.0% (8/42) in resection group; p=0.043 Morbidity CD >3a within 90 days 43.5% (20/46) in LL versus 23.8% (10/42) in resection group; p=0.055 Morbidity CD >3a within 12 months 54.3% (25/46) in LL versus 42.9% (18/42) in resection group; p=0.283 Mortality within 30 days or in-hospital 4.3% (2/46) in LL versus 2.4% (1/42) in resection group; p=0.624 Mortality within 90 days 6.5% (3/46) in LL versus 9.5% (4/42) in resection group Mortality within 12 months 8.7% (4/46) in LL versus 14.3% (6/42) in resection group Patients with stoma at 12 months 14.3% (6/42) in LL versus 16.7% (6/36) in resection group; p=0.419 |

Results reported from intention-to-treat analyses.

Reoperation results included stoma reversal surgery.

Baseline characteristics of eligible but not included patients did not differ from included patients. |

|

Vennix, 2017 LADIES trial |

Type of study: randomized clinical trial

Setting: 30 hospitals

Country: the Netherlands, Belgium, Italy

Source of funding: Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development |

Inclusion criteria: Intraoperatively confirmed Hinchey 3 patients

Exclusion criteria: dementia, previous sigmoidectomy, pelvic irradiation, chronic treatment with high-dose steroids (>20 mg daily), being aged younger than 18 years or older than 85 years, and having preoperative shock needing inotropic support.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 46 Control: 42

Important prognostic factors2: ASA 3/4 18% (8/46) in LL versus 36% (15/42) in resection group. No other significant differences in baseline characteristics between groups. |

To determine the presence of a sigmoid perforation, adherent tissues were carefully removed, but when firmly adherent, they were left in place. Laparoscopic lavage was done by irrigation with up to 6 L of warm saline throughout the abdominal cavity. A Douglas drain was inserted in the right lateral port site. Sigmoidectomy with primary anastomosis was done according to the guidelines of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons and the creation of a defunctioning ileostomy was at the discretion of the surgeon. |

To determine the presence of a sigmoid perforation, adherent tissues were carefully removed, but when firmly adherent, they were left in place. Sigmoidectomy with primary anastomosis was done according to the guidelines of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons and the creation of a defunctioning ileostomy was at the discretion of the surgeon. |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 0.0% (0/46) Control: 0.0% (0/42)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: none

Control: none

|

Medical costs within 12 months: Mean €25,393 in LL versus €28,905 in resection group Medical costs difference LL-resection: -€3512 (95% CI -16,020, -8149) |

Costs based on intention-to-treat analyses. |

Risk of bias tabel

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Angenete, 2016 |

Randomization by a professional statistician not involved in the trial. The allocation sequence was concealed from the staff at the participating centres by using sequentially numbered thick opaque sealed envelopes. The envelope was opened perioperatively. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Likely due to potential influence on threshold to perform reinterventions |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Likely due to only reported results from per-protocol analyses |

|

Gehrman, 2016 |

Randomization by a professional statistician not involved in the trial. The allocation sequence was concealed from the staff at the participating centres by using sequentially numbered thick opaque sealed envelopes. The envelope was opened perioperatively. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Schultz, 2015 |

Centre-stratified block randomization with a web- based randomization system |

Unclear due to limited specification of ‘web-based’ randomization system |

Unlikely |

Likely due to potential influence on threshold to perform reinterventions |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Schultz, 2017 |

Centre-stratified block randomization with a web- based randomization system |

Unclear due to limited specification of ‘web-based’ randomization system |

Unlikely |

Likely due to potential influence on threshold to perform reinterventions |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Thornell, 2016 |

Randomization by a professional statistician not involved in the trial. The allocation sequence was concealed from the staff at the participating centres by using sequentially numbered thick opaque sealed envelopes. The envelope was opened perioperatively. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Likely due to potential influence on threshold to perform reinterventions |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Vennix, 2015 |

Secure online computer randomisation, either directly in the operating room or by the trial coordinator on the phone. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Likely due to potential influence on threshold to perform reinterventions |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Vennix, 2017 |

Secure online computer randomisation, either directly in the operating room or by the trial coordinator on the phone. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 31-05-2018

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 09-05-2018

Voor het beoordelen van de actualiteit van deze richtlijn is de werkgroep niet in stand gehouden. Uiterlijk in 2023 bepaalt het bestuur van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde of de modules van deze richtlijn nog actueel zijn. Op modulair niveau is een onderhoudsplan beschreven. Bij het opstellen van de richtlijn heeft de werkgroep per module een inschatting gemaakt over de maximale termijn waarop herbeoordeling moet plaatsvinden en eventuele aandachtspunten geformuleerd die van belang zijn bij een toekomstige herziening (update). De geldigheid van de richtlijn komt eerder te vervallen indien nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding zijn een herzieningstraject te starten.

De Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde is regiehouder van deze richtlijn en eerstverantwoordelijke op het gebied van de actualiteitsbeoordeling van de richtlijn. De andere aan deze richtlijn deelnemende wetenschappelijke verenigingen of gebruikers van de richtlijn delen de verantwoordelijkheid en informeren de regiehouder over relevante ontwikkelingen binnen hun vakgebied.

Algemene gegevens

De richtlijnontwikkeling werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (http://www.kennisinstituut.nl) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). Patiëntenparticipatie bij deze richtlijn werd mede gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Patiënten Consumenten (SKPC) binnen het programma KIDZ. De SKMS heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijn.

Doel en doelgroep

Doel

Deze richtlijn is bedoeld om een evidence-based beleid voor de zorg voor patiënten met diverticulitis in de tweede lijn op te stellen.

Doelgroep

Deze richtlijn is geschreven voor alle leden van de beroepsgroepen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met diverticulitis, te weten chirurgen, maag- lever- darmartsen, internisten, radiologen en huisartsen. Een secundaire doelgroep zijn zorgverleners uit de eerste lijn die betrokken zijn bij de zorg rondom patiënten met diverticulitis, waaronder huisarts, verpleegkundigen (waaronder continentieverpleegkundige en verpleegkundig specialisten) en physician assistants.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijn is in 2016 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met diverticulitis te maken hebben. Het Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap (NHG) en de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Spoedeisende Hulp Artsen (NVSHA) zijn uitgenodigd om te participeren in de werkgroep maar heeft geen gebruik gemaakt van de uitnodiging.

De werkgroepleden zijn door hun beroepsverenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname.

De werkgroep is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze richtlijn. Stefan van Dijk heeft onder begeleiding van Marja Boermeester de systematische analyses van de literatuur uitgewerkt.

Werkgroep

- Prof. dr. M.A. Boermeester, chirurg, Amsterdam UMC locatie AMC, Amsterdam, NVvH (voorzitter)

- Dr. M.G.J. de Boer, internist, infectioloog, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum, Leiden, NIV

- S. van Dijk, MSc, arts-onderzoeker chirurgie, Amsterdam UMC locatie AMC, Amsterdam, NVvH

- Dr. W.A. Draaisma, chirurg, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, Den Bosch, NVvH

- Dr. R.J.F. Felt-Bersma, MDL-arts, VU Medisch Centrum, Amsterdam, NVMDL

- Dr. B.R. Klarenbeek, chirurg, Radboud UMC, Nijmegen, NVvH

- Dr. J.A. Otte, internist, ZorgSaam Zeeuws-Vlaanderen, Terneuzen, NIV

- Dr. J.B.C.M. Puylaert, radioloog, Medisch Centrum Haaglanden, Den Haag, NVvR

Met ondersteuning van:

- Dr. W.A. van Enst, senior-adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De KNMG-Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of ze in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatie management, kennisvalorisatie) hebben gehad. Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Boermeester |

Gastrointestinaal chirurg, hoogleraar chirurgie van abdominale infecties, chirurgisch hoofd van darmfalenteam AMC |

Geen |

"Niet gerelateerd aan deze richtlijn. Niet-gerelateerde institutional grants van J&J/Ethicon, Acelity/KCI, Ipsen, Baxter, Bard, Mylan" |

Geen |

|

De Boer |

Internist, LUMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Draaisma |

Chirurg, AMC |

lid werkgroep richtlijn Pleuravocht |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Felt-Bersma |

MDL arts, VUMC |

Consultant in de Proctoskliniek Bilthoven |

TEVA sponsort een studie tvgl 3 laxeermiddelen wat we op 1 dec 2016 gaan doen, de gelden komen ten bate van het onderzoek en de ANIOS aanstelling voor 2 mnd |

Geen |

|

Klarenbeek |

Gastrontestinaal en oncologisch chirurg, Radboud UMC |

Geen betaalde nevenfuncties |

ZonMw doelmatigheidssubsidie voor FORCE-trail (BFT na LAR voor rectumcarcinoom). MITEC-subsidies (intern Radboudumc) voor MRI en fluorescentie onderzoek bij oesofaguscarcinoom" |

Geen |

|

Otte |

Internist, ZorgSaam Zeeuws-Vlaanderen |

onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Puylaert |

Radioloog, Medisch Centrum Haaglanden |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Van Dijk |

Arts-onderzoeker chirurgie, AMC |

Betaald promotieonderzoek bij professor M.A. Boermeester over diverticulitis appendicitis en secundaire peritonitis. |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Van Enst |

Senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten, |

Lid van de GRADE working group/ Dutch GRADE Network |

Geen |

Geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door een focusgroep te houden. Deze werd georganiseerd door de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland. Een verslag hiervan (zie aanverwante producten) is besproken in de werkgroep en de belangrijkste knelpunten zijn verwerkt in de richtlijn. De conceptrichtlijn wordt tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

In de verschillende fasen van de richtlijnontwikkeling is rekening gehouden met de implementatie van de richtlijn (module) en de praktische uitvoerbaarheid van de aanbevelingen. Daarbij is uitdrukkelijk gelet op factoren die de invoering van de richtlijn in de praktijk kunnen bevorderen of belemmeren. Het implementatieplan is te vinden bij de aanverwante producten.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijn is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010), dat een internationaal breed geaccepteerd instrument is. Voor een stap-voor-stap beschrijving hoe een evidence-based richtlijn tot stand komt wordt verwezen naar het stappenplan Ontwikkeling van Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Knelpuntenanalyse

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerden de voorzitter van de werkgroep en de adviseur de knelpunten. Stakeholders zijn uitgenodigd voor een knelpuntenbijeenkomst (Invitational conference). Vanwege het lage aantal aanmeldingen (twee, NHG en ZN) is de bijeenkomst geannuleerd. Gevraagd is schriftelijk op het raamwerk te reageren. Daarop kwamen geen reacties.

De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbevelingen uit de eerdere richtlijn (NVvH, 2014) op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen vanuit een patiëntenfocusgroep. De werkgroep stelde vervolgens een long list met knelpunten op en prioriteerde de knelpunten op basis van: (1) klinische relevantie, (2) de beschikbaarheid van (nieuwe) evidence van hoge kwaliteit, (3) en de te verwachten impact op de kwaliteit van zorg, patiëntveiligheid en (macro)kosten.

Uitgangsvragen en uitkomstmaten

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de voorzitter, arts-onderzoeker en de adviseur concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld. Deze zijn met de werkgroep besproken waarna de werkgroep de definitieve uitgangsvragen heeft vastgesteld. Vervolgens inventariseerde de werkgroep per uitgangsvraag welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als kritiek, belangrijk (maar niet kritiek) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de kritieke uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur

Voor de afzonderlijke uitgangsvragen aan de hand van specifieke zoektermen gezocht naar gepubliceerde wetenschappelijke studies in (verschillende) elektronische databases. Tevens werd aanvullend gezocht naar studies aan de hand van de literatuurlijsten van de geselecteerde artikelen. In eerste instantie werd gezocht naar studies met de hoogste mate van bewijs. De adviseur of werkgroepleden selecteerden de via de zoekactie gevonden artikelen op basis van vooraf opgestelde selectiecriteria. De geselecteerde artikelen werden gebruikt om de uitgangsvraag te beantwoorden. De databases waarin is gezocht, de zoekstrategie en de gehanteerde selectiecriteria zijn te vinden in de module met desbetreffende uitgangsvraag. De zoekstrategie voor de oriënterende zoekactie en patiëntenperspectief zijn opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Kwaliteitsbeoordeling individuele studies

Individuele studies werden systematisch beoordeeld, op basis van op voorhand opgestelde methodologische kwaliteitscriteria, om zo het risico op vertekende studieresultaten (risk of bias) te kunnen inschatten. Deze beoordelingen kunt u vinden in de Risk of Bias (RoB) tabellen. De gebruikte RoB instrumenten zijn gevalideerde instrumenten die worden aanbevolen door de Cochrane Collaboration: AMSTAR – voor systematische reviews; Cochrane – voor gerandomiseerd gecontroleerd onderzoek; ACROBAT-NRS – voor observationeel onderzoek; QUADAS II – voor diagnostisch onderzoek.

Samenvatten van de literatuur

De relevante onderzoeksgegevens van alle geselecteerde artikelen werden overzichtelijk weergegeven in evidence-tabellen. De belangrijkste bevindingen uit de literatuur werden beschreven in de samenvatting van de literatuur. Bij een voldoende aantal studies en overeenkomstigheid (homogeniteit) tussen de studies werden de gegevens ook kwantitatief samengevat (meta-analyse) met behulp van Review Manager 5.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

A) Voor interventievragen (vragen over therapie of screening)

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie (Schünemann, 2013).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

B) Voor vragen over diagnostische tests, schade of bijwerkingen, etiologie en prognose

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd eveneens bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode: GRADE-diagnostiek voor diagnostische vragen (Schünemann, 2008), en een generieke GRADE-methode voor vragen over schade of bijwerkingen, etiologie en prognose. In de gehanteerde generieke GRADE-methode werden de basisprincipes van de GRADE methodiek toegepast: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van bewijskracht op basis van de vijf GRADE criteria (startpunt hoog; downgraden voor risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias).

Formuleren van de conclusies

Voor elke relevante uitkomstmaat werd het wetenschappelijk bewijs samengevat in een of meerdere literatuurconclusies waarbij het niveau van bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE methodiek. De werkgroepleden maakten de balans op van elke interventie (overall conclusie). Bij het opmaken van de balans werden de gunstige en ongunstige effecten voor de patiënt afgewogen. De overall bewijskracht wordt bepaald door de laagste bewijskracht gevonden bij een van de kritieke uitkomstmaten. Bij complexe besluitvorming waarin naast de conclusies uit de systematische literatuuranalyse vele aanvullende argumenten (overwegingen) een rol spelen, werd afgezien van een overall conclusie. In dat geval werden de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de interventies samen met alle aanvullende argumenten gewogen onder het kopje Overwegingen.

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals de expertise van de werkgroepleden, de waarden en voorkeuren van de patiënt (patient values and preferences), kosten, beschikbaarheid van voorzieningen en organisatorische zaken. Deze aspecten worden, voor zover geen onderdeel van de literatuursamenvatting, vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje Overwegingen.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk. De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen.

Randvoorwaarden (Organisatie van zorg)

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijn is expliciet rekening gehouden met de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, menskracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van een specifieke uitgangsvraag maken onderdeel uit van de overwegingen bij de bewuste uitgangsvraag.

Indicatorontwikkeling

Gelijktijdig met het ontwikkelen van de conceptrichtlijn heeft de werkgroep overwogen om interne kwaliteitsindicatoren te ontwikkelen om het toepassen van de richtlijn in de praktijk te volgen en te versterken. De werkgroep heeft besloten geen indicatoren te ontwikkelen bij de huidige richtlijn, omdat er of geen substantiële barrières konden worden geïdentificeerd die implementatie van de aanbeveling zouden kunnen bemoeilijken. Meer informatie over de methode van indicatorontwikkeling is op te vragen bij het Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten (secretariaat@kennisinstituut.nl).

Kennislacunes

Tijdens de ontwikkeling van deze richtlijn is systematisch gezocht naar onderzoek waarvan de resultaten bijdragen aan een antwoord op de uitgangsvragen. Bij elke uitgangsvraag is door de werkgroep nagegaan of er (aanvullend) wetenschappelijk onderzoek gewenst is om de uitgangsvraag te kunnen beantwoorden. Een overzicht van de onderwerpen waarvoor (aanvullend) wetenschappelijk van belang wordt geacht, is als aanbeveling in de Kennislacunes beschreven (onder aanverwante producten).

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijn wordt aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren worden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren zal de conceptrichtlijn aangepast worden en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijn wordt aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

- Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348.

- Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0. Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/richtlijnontwikkeling.html. 2012.

- Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html. 2013.

- Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ. 2008;336(7653):1106-10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39500.677199.AE. Erratum in: BMJ. 2008;336(7654). doi: 10.1136/bmj.a139. PubMed PMID: 18483053.

- Ontwikkeling van Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen: stappenplan. Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Zoekverantwoording

|

Databases:

Geraadpleegd tot: 05-04-2017 |

Zoekstrategie: (Diverticulitis[Mesh] OR “diverticulitis, colonic”[Mesh] OR diverticulitis[tiab] OR diverticular[tiab]) AND (lavage[tiab]) |

Resultaten: Pubmed 178 hits Embase 256 hits Cochrane 0 hits

Duplicaten: 105 hits

Inclusie: 6 artikelen |

Tabel Exclusie na het lezen van het volledige artikel

|

Auteur en jaartal |

Redenen van exclusie |

|

Angenete, 2017 |

Systematische review |

|

Biffl, 2017 |

Review |

|

Ceresoli, 2016 |

Systematische review |

|

Cirocchi, 2017 |

Systematische review |

|

Marshall, 2017 |

Systematische review |

|

Penna, 2017 |

Systematische review |

|

Ponzano, 2015 |

Letter to the editor |

|

Shaikh, 2017 |

Systematische review |